User login

Early breast cancer: Updated MINDACT findings back omitting chemotherapy in low genomic risk

Key clinical point: Among women with breast cancer and high clinical risk, a subgroup of patients with low genomic risk identified by the 70-gene signature showed excellent distant metastasis-free survival (DMFS) even without chemotherapy. No benefits of chemotherapy were observed in women older than 50 years.

Major finding: Eight-year DMFS in patients with high clinical but low genomic risk with vs. without chemotherapy was 92.0% vs. 89.4%, with the benefit of adding chemotherapy to endocrine therapy remaining small (absolute difference, 2·6 percentage points). Chemotherapy showed no benefits in older women aged more than 50 years (absolute difference, 0.2 percentage points).

Study details: Findings are from the 8-year analysis of phase 3 MINDACT trial, including women with primary nonmetastatic invasive breast cancer with up to 3 positive lymph nodes. The 70-gene signature (MammaPrint) identified women with high clinical but low genomic risk who were randomly assigned to chemotherapy (n=749) vs. no chemotherapy (n=748).

Disclosures: This study was funded by European Commission Sixth Framework Programme (ECSFP). Some investigators including the lead author reported ties with various pharmaceutical companies and funding agencies including the ECSFP.

Source: Piccart M et al. Lancet Oncol. 2021 Mar 12. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(21)00007-3.

Key clinical point: Among women with breast cancer and high clinical risk, a subgroup of patients with low genomic risk identified by the 70-gene signature showed excellent distant metastasis-free survival (DMFS) even without chemotherapy. No benefits of chemotherapy were observed in women older than 50 years.

Major finding: Eight-year DMFS in patients with high clinical but low genomic risk with vs. without chemotherapy was 92.0% vs. 89.4%, with the benefit of adding chemotherapy to endocrine therapy remaining small (absolute difference, 2·6 percentage points). Chemotherapy showed no benefits in older women aged more than 50 years (absolute difference, 0.2 percentage points).

Study details: Findings are from the 8-year analysis of phase 3 MINDACT trial, including women with primary nonmetastatic invasive breast cancer with up to 3 positive lymph nodes. The 70-gene signature (MammaPrint) identified women with high clinical but low genomic risk who were randomly assigned to chemotherapy (n=749) vs. no chemotherapy (n=748).

Disclosures: This study was funded by European Commission Sixth Framework Programme (ECSFP). Some investigators including the lead author reported ties with various pharmaceutical companies and funding agencies including the ECSFP.

Source: Piccart M et al. Lancet Oncol. 2021 Mar 12. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(21)00007-3.

Key clinical point: Among women with breast cancer and high clinical risk, a subgroup of patients with low genomic risk identified by the 70-gene signature showed excellent distant metastasis-free survival (DMFS) even without chemotherapy. No benefits of chemotherapy were observed in women older than 50 years.

Major finding: Eight-year DMFS in patients with high clinical but low genomic risk with vs. without chemotherapy was 92.0% vs. 89.4%, with the benefit of adding chemotherapy to endocrine therapy remaining small (absolute difference, 2·6 percentage points). Chemotherapy showed no benefits in older women aged more than 50 years (absolute difference, 0.2 percentage points).

Study details: Findings are from the 8-year analysis of phase 3 MINDACT trial, including women with primary nonmetastatic invasive breast cancer with up to 3 positive lymph nodes. The 70-gene signature (MammaPrint) identified women with high clinical but low genomic risk who were randomly assigned to chemotherapy (n=749) vs. no chemotherapy (n=748).

Disclosures: This study was funded by European Commission Sixth Framework Programme (ECSFP). Some investigators including the lead author reported ties with various pharmaceutical companies and funding agencies including the ECSFP.

Source: Piccart M et al. Lancet Oncol. 2021 Mar 12. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(21)00007-3.

Early breast cancer: Updated MINDACT findings back omitting chemotherapy in low genomic risk

Key clinical point: Among women with breast cancer and high clinical risk, a subgroup of patients with low genomic risk identified by the 70-gene signature showed excellent distant metastasis-free survival (DMFS) even without chemotherapy. No benefits of chemotherapy were observed in women older than 50 years.

Major finding: Eight-year DMFS in patients with high clinical but low genomic risk with vs. without chemotherapy was 92.0% vs. 89.4%, with the benefit of adding chemotherapy to endocrine therapy remaining small (absolute difference, 2·6 percentage points). Chemotherapy showed no benefits in older women aged more than 50 years (absolute difference, 0.2 percentage points).

Study details: Findings are from the 8-year analysis of phase 3 MINDACT trial, including women with primary nonmetastatic invasive breast cancer with up to 3 positive lymph nodes. The 70-gene signature (MammaPrint) identified women with high clinical but low genomic risk who were randomly assigned to chemotherapy (n=749) vs. no chemotherapy (n=748).

Disclosures: This study was funded by European Commission Sixth Framework Programme (ECSFP). Some investigators including the lead author reported ties with various pharmaceutical companies and funding agencies including the ECSFP.

Source: Piccart M et al. Lancet Oncol. 2021 Mar 12. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(21)00007-3.

Key clinical point: Among women with breast cancer and high clinical risk, a subgroup of patients with low genomic risk identified by the 70-gene signature showed excellent distant metastasis-free survival (DMFS) even without chemotherapy. No benefits of chemotherapy were observed in women older than 50 years.

Major finding: Eight-year DMFS in patients with high clinical but low genomic risk with vs. without chemotherapy was 92.0% vs. 89.4%, with the benefit of adding chemotherapy to endocrine therapy remaining small (absolute difference, 2·6 percentage points). Chemotherapy showed no benefits in older women aged more than 50 years (absolute difference, 0.2 percentage points).

Study details: Findings are from the 8-year analysis of phase 3 MINDACT trial, including women with primary nonmetastatic invasive breast cancer with up to 3 positive lymph nodes. The 70-gene signature (MammaPrint) identified women with high clinical but low genomic risk who were randomly assigned to chemotherapy (n=749) vs. no chemotherapy (n=748).

Disclosures: This study was funded by European Commission Sixth Framework Programme (ECSFP). Some investigators including the lead author reported ties with various pharmaceutical companies and funding agencies including the ECSFP.

Source: Piccart M et al. Lancet Oncol. 2021 Mar 12. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(21)00007-3.

Key clinical point: Among women with breast cancer and high clinical risk, a subgroup of patients with low genomic risk identified by the 70-gene signature showed excellent distant metastasis-free survival (DMFS) even without chemotherapy. No benefits of chemotherapy were observed in women older than 50 years.

Major finding: Eight-year DMFS in patients with high clinical but low genomic risk with vs. without chemotherapy was 92.0% vs. 89.4%, with the benefit of adding chemotherapy to endocrine therapy remaining small (absolute difference, 2·6 percentage points). Chemotherapy showed no benefits in older women aged more than 50 years (absolute difference, 0.2 percentage points).

Study details: Findings are from the 8-year analysis of phase 3 MINDACT trial, including women with primary nonmetastatic invasive breast cancer with up to 3 positive lymph nodes. The 70-gene signature (MammaPrint) identified women with high clinical but low genomic risk who were randomly assigned to chemotherapy (n=749) vs. no chemotherapy (n=748).

Disclosures: This study was funded by European Commission Sixth Framework Programme (ECSFP). Some investigators including the lead author reported ties with various pharmaceutical companies and funding agencies including the ECSFP.

Source: Piccart M et al. Lancet Oncol. 2021 Mar 12. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(21)00007-3.

Risk-based mammography proposed for times of reduced capacity

Researchers evaluated almost 2 million mammograms that had been performed at more than 90 radiology centers and found that 12% of mammograms with “high” and “very high” cancer risk rates accounted for 55% of detected cancers.

In contrast, 44% of mammograms with very low cancer risk rates accounted for 13% of detected cancers. The study was published online March 25, 2021, in JAMA Network Open.

Cancer screening programs dramatically slowed or even came to a screeching halt during 2020, when restrictions and lockdowns were in place. The American Cancer Society even recommended that “no one should go to a health care facility for routine cancer screening,” as part of COVID-19 precautions.

However, concern was voiced that the pause in screening would allow patients with asymptomatic cancers or precursor lesions to develop into a more serious disease state.

The authors pointed out that several professional associations had posted guidance for scheduling individuals for breast imaging services during the COVID-19 pandemic, but these recommendations were based on expert opinion. The investigators’ goal was to help imaging facilities optimize the number of breast cancers that could be detected during periods of reduced capacity using clinical indication and individual characteristics.

The result was a risk-based strategy for triaging mammograms during periods of decreased capacity, which lead author Diana L. Miglioretti, PhD, explained was feasible to implement. Dr. Miglioretti is division chief of biostatistics in the department of public health sciences at University of California, Davis.

“Our risk model used information that is commonly collected by radiology facilities,” she said in an interview. “Vendors of electronic medical records could create tools that pull the information from the medical record, or could create fields in the scheduling system to efficiently collect this information when the mammogram is scheduled.”

Dr. Miglioretti emphasized that, once the information is collected in a standardized manner, “it would be straightforward to use a computer program to apply our algorithm to rank women based on their likelihood of having a breast cancer detected.”

“I think it is worth the investment to create these electronic tools now, given the potential for future shutdowns or periods of reduced capacity due to a variety of reasons, such as natural disasters and cyberattacks – or another pandemic,” she said.

Some facilities are still working through backlogs of mammograms that need to be rescheduled, which would be another way that this algorithm could be used. “They could use this approach to determine who should be scheduled first by using data available in the electronic medical record,” she added.

Five risk groups

Dr. Miglioretti and colleagues conducted a cohort study using data that was prospectively collected from mammography examinations performed from 2014 to 2019 at 92 radiology facilities in the Breast Cancer Surveillance Consortium. The cohort included 898,415 individuals who contributed to 1.8 million mammograms.

Information that included clinical indication for screening, breast symptoms, personal history of breast cancer, age, time since last mammogram/screening interval, family history of breast cancer, breast density, and history of high-risk breast lesion was collected from self-administered questionnaires at the time of mammography or extracted from electronic health records.

Following analysis, the data was categorized into five risk groups: very high (>50), high (22-50), moderate (10-22), low (5-10), and very low (<5) cancer detection rate per 1,000 mammograms. These thresholds were chosen based on the observed cancer detection rates and clinical expertise.

Of the group, about 1.7 million mammograms were from women without a personal history of breast cancer and 156,104 mammograms were from women with a breast cancer history. Most of the cohort were aged 50-69 years at the time of imaging, and 67.9% were White (11.2% Black, 11.3% Asian or Pacific Islander, 7% Hispanic, and 2.2% were another race/ethnicity or mixed race/ethnicity).

Their results showed that 12% of mammograms with very high (89.6-122.3 cancers detected per 1,000 mammograms) or high (36.1-47.5 cancers detected per 1,000 mammograms) cancer detection rates accounted for 55% of all detected cancers. These included mammograms that were done to evaluate an abnormal test or breast lump in individuals of all ages regardless of breast cancer history.

On the opposite end, 44.2% of mammograms with very low cancer detection rates accounted for 13.1% of detected cancers and that included annual screening tests in women aged 50-69 years (3.8 cancers detected per 1,000 mammograms) and all screening mammograms in individuals younger than 50 years regardless of screening interval (2.8 cancers detected per 1000 mammograms).

Treat with caution

In an accompanying editorial, Sarah M. Friedewald, MD, and Dipti Gupta, MD, both from Northwestern University, Chicago, pointed out that, while the authors examined a large dataset to identify a subgroup of patients who would most likely benefit from breast imaging in a setting where capacity is limited, “these data should be used with caution as the only barometer for whether a patient merits cancer screening during a period of rationing.”

They noted that, in the context of an acute crisis, when patient volume needs to be reduced very quickly, it is often impractical for clinicians to sift through patient records in order to capture the information necessary for triage. In addition, asking nonclinical schedulers to accurately pull data at this level, at the time when the patient calls to make an appointment, is unrealistic.

In the context of the pandemic, the editorialists wrote that, while this model uses risk for breast cancer to prioritize those to be seen in the clinic, the risk for complications from COVID-19 may also be an important factor to consider. For example, an older patient may be at a higher risk for breast cancer but may also face a higher risk for COVID-related complications. Conversely, a younger woman at a lower risk for serious COVID-related disease but who has breast cancer detected early will gain more life-years than an older patient.

There are also no algorithms to account for each patient’s perceived risk for breast cancer or COVID-19, and “the downstream effect of delaying cancer diagnosis may similarly lead to unintended consequences but may take longer to become apparent,” they wrote. “Focusing efforts on the operations of accommodating as many patients as possible, such as extending clinic hours, would be preferable.”

Finally, Dr. Friedewald and Dr. Gupta concluded that “the practicality of this process during the COVID-19 pandemic and extrapolation to other emergent settings are less obvious.”

The study was supported through a Patient-centered Outcomes Research Institute program award. Dr. Miglioretti reported receiving royalties from Elsevier outside the submitted work. Several coauthors report relationships with industry. Dr. Friedewald reported receiving grants from Hologic Research during the conduct of the study. Dr. Gupta disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Researchers evaluated almost 2 million mammograms that had been performed at more than 90 radiology centers and found that 12% of mammograms with “high” and “very high” cancer risk rates accounted for 55% of detected cancers.

In contrast, 44% of mammograms with very low cancer risk rates accounted for 13% of detected cancers. The study was published online March 25, 2021, in JAMA Network Open.

Cancer screening programs dramatically slowed or even came to a screeching halt during 2020, when restrictions and lockdowns were in place. The American Cancer Society even recommended that “no one should go to a health care facility for routine cancer screening,” as part of COVID-19 precautions.

However, concern was voiced that the pause in screening would allow patients with asymptomatic cancers or precursor lesions to develop into a more serious disease state.

The authors pointed out that several professional associations had posted guidance for scheduling individuals for breast imaging services during the COVID-19 pandemic, but these recommendations were based on expert opinion. The investigators’ goal was to help imaging facilities optimize the number of breast cancers that could be detected during periods of reduced capacity using clinical indication and individual characteristics.

The result was a risk-based strategy for triaging mammograms during periods of decreased capacity, which lead author Diana L. Miglioretti, PhD, explained was feasible to implement. Dr. Miglioretti is division chief of biostatistics in the department of public health sciences at University of California, Davis.

“Our risk model used information that is commonly collected by radiology facilities,” she said in an interview. “Vendors of electronic medical records could create tools that pull the information from the medical record, or could create fields in the scheduling system to efficiently collect this information when the mammogram is scheduled.”

Dr. Miglioretti emphasized that, once the information is collected in a standardized manner, “it would be straightforward to use a computer program to apply our algorithm to rank women based on their likelihood of having a breast cancer detected.”

“I think it is worth the investment to create these electronic tools now, given the potential for future shutdowns or periods of reduced capacity due to a variety of reasons, such as natural disasters and cyberattacks – or another pandemic,” she said.

Some facilities are still working through backlogs of mammograms that need to be rescheduled, which would be another way that this algorithm could be used. “They could use this approach to determine who should be scheduled first by using data available in the electronic medical record,” she added.

Five risk groups

Dr. Miglioretti and colleagues conducted a cohort study using data that was prospectively collected from mammography examinations performed from 2014 to 2019 at 92 radiology facilities in the Breast Cancer Surveillance Consortium. The cohort included 898,415 individuals who contributed to 1.8 million mammograms.

Information that included clinical indication for screening, breast symptoms, personal history of breast cancer, age, time since last mammogram/screening interval, family history of breast cancer, breast density, and history of high-risk breast lesion was collected from self-administered questionnaires at the time of mammography or extracted from electronic health records.

Following analysis, the data was categorized into five risk groups: very high (>50), high (22-50), moderate (10-22), low (5-10), and very low (<5) cancer detection rate per 1,000 mammograms. These thresholds were chosen based on the observed cancer detection rates and clinical expertise.

Of the group, about 1.7 million mammograms were from women without a personal history of breast cancer and 156,104 mammograms were from women with a breast cancer history. Most of the cohort were aged 50-69 years at the time of imaging, and 67.9% were White (11.2% Black, 11.3% Asian or Pacific Islander, 7% Hispanic, and 2.2% were another race/ethnicity or mixed race/ethnicity).

Their results showed that 12% of mammograms with very high (89.6-122.3 cancers detected per 1,000 mammograms) or high (36.1-47.5 cancers detected per 1,000 mammograms) cancer detection rates accounted for 55% of all detected cancers. These included mammograms that were done to evaluate an abnormal test or breast lump in individuals of all ages regardless of breast cancer history.

On the opposite end, 44.2% of mammograms with very low cancer detection rates accounted for 13.1% of detected cancers and that included annual screening tests in women aged 50-69 years (3.8 cancers detected per 1,000 mammograms) and all screening mammograms in individuals younger than 50 years regardless of screening interval (2.8 cancers detected per 1000 mammograms).

Treat with caution

In an accompanying editorial, Sarah M. Friedewald, MD, and Dipti Gupta, MD, both from Northwestern University, Chicago, pointed out that, while the authors examined a large dataset to identify a subgroup of patients who would most likely benefit from breast imaging in a setting where capacity is limited, “these data should be used with caution as the only barometer for whether a patient merits cancer screening during a period of rationing.”

They noted that, in the context of an acute crisis, when patient volume needs to be reduced very quickly, it is often impractical for clinicians to sift through patient records in order to capture the information necessary for triage. In addition, asking nonclinical schedulers to accurately pull data at this level, at the time when the patient calls to make an appointment, is unrealistic.

In the context of the pandemic, the editorialists wrote that, while this model uses risk for breast cancer to prioritize those to be seen in the clinic, the risk for complications from COVID-19 may also be an important factor to consider. For example, an older patient may be at a higher risk for breast cancer but may also face a higher risk for COVID-related complications. Conversely, a younger woman at a lower risk for serious COVID-related disease but who has breast cancer detected early will gain more life-years than an older patient.

There are also no algorithms to account for each patient’s perceived risk for breast cancer or COVID-19, and “the downstream effect of delaying cancer diagnosis may similarly lead to unintended consequences but may take longer to become apparent,” they wrote. “Focusing efforts on the operations of accommodating as many patients as possible, such as extending clinic hours, would be preferable.”

Finally, Dr. Friedewald and Dr. Gupta concluded that “the practicality of this process during the COVID-19 pandemic and extrapolation to other emergent settings are less obvious.”

The study was supported through a Patient-centered Outcomes Research Institute program award. Dr. Miglioretti reported receiving royalties from Elsevier outside the submitted work. Several coauthors report relationships with industry. Dr. Friedewald reported receiving grants from Hologic Research during the conduct of the study. Dr. Gupta disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Researchers evaluated almost 2 million mammograms that had been performed at more than 90 radiology centers and found that 12% of mammograms with “high” and “very high” cancer risk rates accounted for 55% of detected cancers.

In contrast, 44% of mammograms with very low cancer risk rates accounted for 13% of detected cancers. The study was published online March 25, 2021, in JAMA Network Open.

Cancer screening programs dramatically slowed or even came to a screeching halt during 2020, when restrictions and lockdowns were in place. The American Cancer Society even recommended that “no one should go to a health care facility for routine cancer screening,” as part of COVID-19 precautions.

However, concern was voiced that the pause in screening would allow patients with asymptomatic cancers or precursor lesions to develop into a more serious disease state.

The authors pointed out that several professional associations had posted guidance for scheduling individuals for breast imaging services during the COVID-19 pandemic, but these recommendations were based on expert opinion. The investigators’ goal was to help imaging facilities optimize the number of breast cancers that could be detected during periods of reduced capacity using clinical indication and individual characteristics.

The result was a risk-based strategy for triaging mammograms during periods of decreased capacity, which lead author Diana L. Miglioretti, PhD, explained was feasible to implement. Dr. Miglioretti is division chief of biostatistics in the department of public health sciences at University of California, Davis.

“Our risk model used information that is commonly collected by radiology facilities,” she said in an interview. “Vendors of electronic medical records could create tools that pull the information from the medical record, or could create fields in the scheduling system to efficiently collect this information when the mammogram is scheduled.”

Dr. Miglioretti emphasized that, once the information is collected in a standardized manner, “it would be straightforward to use a computer program to apply our algorithm to rank women based on their likelihood of having a breast cancer detected.”

“I think it is worth the investment to create these electronic tools now, given the potential for future shutdowns or periods of reduced capacity due to a variety of reasons, such as natural disasters and cyberattacks – or another pandemic,” she said.

Some facilities are still working through backlogs of mammograms that need to be rescheduled, which would be another way that this algorithm could be used. “They could use this approach to determine who should be scheduled first by using data available in the electronic medical record,” she added.

Five risk groups

Dr. Miglioretti and colleagues conducted a cohort study using data that was prospectively collected from mammography examinations performed from 2014 to 2019 at 92 radiology facilities in the Breast Cancer Surveillance Consortium. The cohort included 898,415 individuals who contributed to 1.8 million mammograms.

Information that included clinical indication for screening, breast symptoms, personal history of breast cancer, age, time since last mammogram/screening interval, family history of breast cancer, breast density, and history of high-risk breast lesion was collected from self-administered questionnaires at the time of mammography or extracted from electronic health records.

Following analysis, the data was categorized into five risk groups: very high (>50), high (22-50), moderate (10-22), low (5-10), and very low (<5) cancer detection rate per 1,000 mammograms. These thresholds were chosen based on the observed cancer detection rates and clinical expertise.

Of the group, about 1.7 million mammograms were from women without a personal history of breast cancer and 156,104 mammograms were from women with a breast cancer history. Most of the cohort were aged 50-69 years at the time of imaging, and 67.9% were White (11.2% Black, 11.3% Asian or Pacific Islander, 7% Hispanic, and 2.2% were another race/ethnicity or mixed race/ethnicity).

Their results showed that 12% of mammograms with very high (89.6-122.3 cancers detected per 1,000 mammograms) or high (36.1-47.5 cancers detected per 1,000 mammograms) cancer detection rates accounted for 55% of all detected cancers. These included mammograms that were done to evaluate an abnormal test or breast lump in individuals of all ages regardless of breast cancer history.

On the opposite end, 44.2% of mammograms with very low cancer detection rates accounted for 13.1% of detected cancers and that included annual screening tests in women aged 50-69 years (3.8 cancers detected per 1,000 mammograms) and all screening mammograms in individuals younger than 50 years regardless of screening interval (2.8 cancers detected per 1000 mammograms).

Treat with caution

In an accompanying editorial, Sarah M. Friedewald, MD, and Dipti Gupta, MD, both from Northwestern University, Chicago, pointed out that, while the authors examined a large dataset to identify a subgroup of patients who would most likely benefit from breast imaging in a setting where capacity is limited, “these data should be used with caution as the only barometer for whether a patient merits cancer screening during a period of rationing.”

They noted that, in the context of an acute crisis, when patient volume needs to be reduced very quickly, it is often impractical for clinicians to sift through patient records in order to capture the information necessary for triage. In addition, asking nonclinical schedulers to accurately pull data at this level, at the time when the patient calls to make an appointment, is unrealistic.

In the context of the pandemic, the editorialists wrote that, while this model uses risk for breast cancer to prioritize those to be seen in the clinic, the risk for complications from COVID-19 may also be an important factor to consider. For example, an older patient may be at a higher risk for breast cancer but may also face a higher risk for COVID-related complications. Conversely, a younger woman at a lower risk for serious COVID-related disease but who has breast cancer detected early will gain more life-years than an older patient.

There are also no algorithms to account for each patient’s perceived risk for breast cancer or COVID-19, and “the downstream effect of delaying cancer diagnosis may similarly lead to unintended consequences but may take longer to become apparent,” they wrote. “Focusing efforts on the operations of accommodating as many patients as possible, such as extending clinic hours, would be preferable.”

Finally, Dr. Friedewald and Dr. Gupta concluded that “the practicality of this process during the COVID-19 pandemic and extrapolation to other emergent settings are less obvious.”

The study was supported through a Patient-centered Outcomes Research Institute program award. Dr. Miglioretti reported receiving royalties from Elsevier outside the submitted work. Several coauthors report relationships with industry. Dr. Friedewald reported receiving grants from Hologic Research during the conduct of the study. Dr. Gupta disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Encephalopathy common, often lethal in hospitalized patients with COVID-19

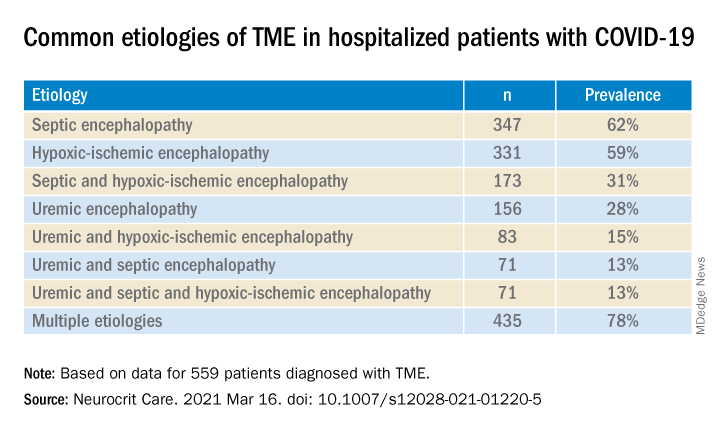

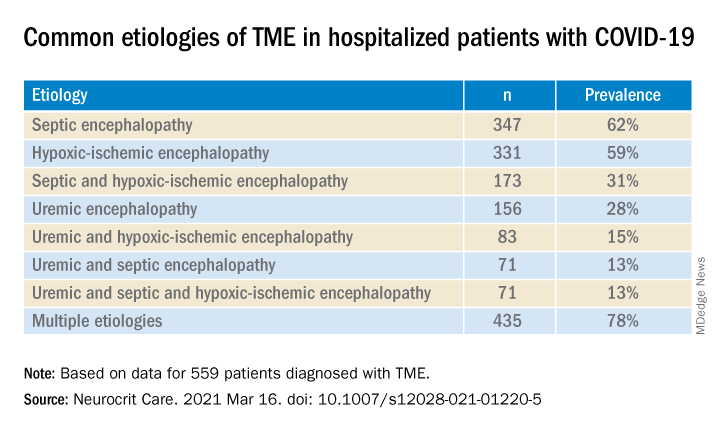

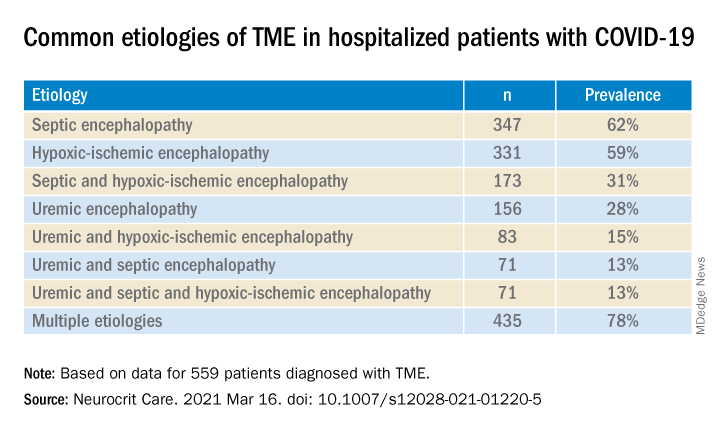

, new research shows. Results of a retrospective study show that of almost 4,500 patients with COVID-19, 12% were diagnosed with TME. Of these, 78% developed encephalopathy immediately prior to hospital admission. Septic encephalopathy, hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy (HIE), and uremia were the most common causes, although multiple causes were present in close to 80% of patients. TME was also associated with a 24% higher risk of in-hospital death.

“We found that close to one in eight patients who were hospitalized with COVID-19 had TME that was not attributed to the effects of sedatives, and that this is incredibly common among these patients who are critically ill” said lead author Jennifer A. Frontera, MD, New York University.

“The general principle of our findings is to be more aggressive in TME; and from a neurologist perspective, the way to do this is to eliminate the effects of sedation, which is a confounder,” she said.

The study was published online March 16 in Neurocritical Care.

Drilling down

“Many neurological complications of COVID-19 are sequelae of severe illness or secondary effects of multisystem organ failure, but our previous work identified TME as the most common neurological complication,” Dr. Frontera said.

Previous research investigating encephalopathy among patients with COVID-19 included patients who may have been sedated or have had a positive Confusion Assessment Method (CAM) result.

“A lot of the delirium literature is effectively heterogeneous because there are a number of patients who are on sedative medication that, if you could turn it off, these patients would return to normal. Some may have underlying neurological issues that can be addressed, but you can›t get to the bottom of this unless you turn off the sedation,” Dr. Frontera noted.

“We wanted to be specific and try to drill down to see what the underlying cause of the encephalopathy was,” she said.

The researchers retrospectively analyzed data on 4,491 patients (≥ 18 years old) with COVID-19 who were admitted to four New York City hospitals between March 1, 2020, and May 20, 2020. Of these, 559 (12%) with TME were compared with 3,932 patients without TME.

The researchers looked at index admissions and included patients who had:

- New changes in mental status or significant worsening of mental status (in patients with baseline abnormal mental status).

- Hyperglycemia or with transient focal neurologic deficits that resolved with glucose correction.

- An adequate washout of sedating medications (when relevant) prior to mental status assessment.

Potential etiologies included electrolyte abnormalities, organ failure, hypertensive encephalopathy, sepsis or active infection, fever, nutritional deficiency, and environmental injury.

Foreign environment

Most (78%) of the 559 patients diagnosed with TME had already developed encephalopathy immediately prior to hospital admission, the authors report. The most common etiologies of TME among hospitalized patients with COVID-19 are listed below.

Compared with patients without TME, those with TME – (all Ps < .001):

- Were older (76 vs. 62 years).

- Had higher rates of dementia (27% vs. 3%).

- Had higher rates of psychiatric history (20% vs. 10%).

- Were more often intubated (37% vs. 20%).

- Had a longer length of hospital stay (7.9 vs. 6.0 days).

- Were less often discharged home (25% vs. 66%).

“It’s no surprise that older patients and people with dementia or psychiatric illness are predisposed to becoming encephalopathic,” said Dr. Frontera. “Being in a foreign environment, such as a hospital, or being sleep-deprived in the ICU is likely to make them more confused during their hospital stay.”

Delirium as a symptom

In-hospital mortality or discharge to hospice was considerably higher in the TME versus non-TME patients (44% vs. 18%, respectively).

When the researchers adjusted for confounders (age, sex, race, worse Sequential Organ Failure Assessment score during hospitalization, ventilator status, study week, hospital location, and ICU care level) and excluded patients receiving only comfort care, they found that TME was associated with a 24% increased risk of in-hospital death (30% in patients with TME vs. 16% in those without TME).

The highest mortality risk was associated with hypoxemia, with 42% of patients with HIE dying during hospitalization, compared with 16% of patients without HIE (adjusted hazard ratio 1.56; 95% confidence interval, 1.21-2.00; P = .001).

“Not all patients who are intubated require sedation, but there’s generally a lot of hesitation in reducing or stopping sedation in some patients,” Dr. Frontera observed.

She acknowledged there are “many extremely sick patients whom you can’t ventilate without sedation.”

Nevertheless, “delirium in and of itself does not cause death. It’s a symptom, not a disease, and we have to figure out what causes it. Delirium might not need to be sedated, and it’s more important to see what the causal problem is.”

Independent predictor of death

Commenting on the study, Panayiotis N. Varelas, MD, PhD, vice president of the Neurocritical Care Society, said the study “approached the TME issue better than previously, namely allowing time for sedatives to wear off to have a better sample of patients with this syndrome.”

Dr. Varelas, who is chairman of the department of neurology and professor of neurology at Albany (N.Y.) Medical College, emphasized that TME “is not benign and, in patients with COVID-19, it is an independent predictor of in-hospital mortality.”

“One should take all possible measures … to avoid desaturation and hypotensive episodes and also aggressively treat SAE and uremic encephalopathy in hopes of improving the outcomes,” added Dr. Varelas, who was not involved with the study.

Also commenting on the study, Mitchell Elkind, MD, professor of neurology and epidemiology at Columbia University in New York, who was not associated with the research, said it “nicely distinguishes among the different causes of encephalopathy, including sepsis, hypoxia, and kidney failure … emphasizing just how sick these patients are.”

The study received no direct funding. Individual investigators were supported by grants from the National Institute on Aging and the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke. The investigators, Dr. Varelas, and Dr. Elkind have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

, new research shows. Results of a retrospective study show that of almost 4,500 patients with COVID-19, 12% were diagnosed with TME. Of these, 78% developed encephalopathy immediately prior to hospital admission. Septic encephalopathy, hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy (HIE), and uremia were the most common causes, although multiple causes were present in close to 80% of patients. TME was also associated with a 24% higher risk of in-hospital death.

“We found that close to one in eight patients who were hospitalized with COVID-19 had TME that was not attributed to the effects of sedatives, and that this is incredibly common among these patients who are critically ill” said lead author Jennifer A. Frontera, MD, New York University.

“The general principle of our findings is to be more aggressive in TME; and from a neurologist perspective, the way to do this is to eliminate the effects of sedation, which is a confounder,” she said.

The study was published online March 16 in Neurocritical Care.

Drilling down

“Many neurological complications of COVID-19 are sequelae of severe illness or secondary effects of multisystem organ failure, but our previous work identified TME as the most common neurological complication,” Dr. Frontera said.

Previous research investigating encephalopathy among patients with COVID-19 included patients who may have been sedated or have had a positive Confusion Assessment Method (CAM) result.

“A lot of the delirium literature is effectively heterogeneous because there are a number of patients who are on sedative medication that, if you could turn it off, these patients would return to normal. Some may have underlying neurological issues that can be addressed, but you can›t get to the bottom of this unless you turn off the sedation,” Dr. Frontera noted.

“We wanted to be specific and try to drill down to see what the underlying cause of the encephalopathy was,” she said.

The researchers retrospectively analyzed data on 4,491 patients (≥ 18 years old) with COVID-19 who were admitted to four New York City hospitals between March 1, 2020, and May 20, 2020. Of these, 559 (12%) with TME were compared with 3,932 patients without TME.

The researchers looked at index admissions and included patients who had:

- New changes in mental status or significant worsening of mental status (in patients with baseline abnormal mental status).

- Hyperglycemia or with transient focal neurologic deficits that resolved with glucose correction.

- An adequate washout of sedating medications (when relevant) prior to mental status assessment.

Potential etiologies included electrolyte abnormalities, organ failure, hypertensive encephalopathy, sepsis or active infection, fever, nutritional deficiency, and environmental injury.

Foreign environment

Most (78%) of the 559 patients diagnosed with TME had already developed encephalopathy immediately prior to hospital admission, the authors report. The most common etiologies of TME among hospitalized patients with COVID-19 are listed below.

Compared with patients without TME, those with TME – (all Ps < .001):

- Were older (76 vs. 62 years).

- Had higher rates of dementia (27% vs. 3%).

- Had higher rates of psychiatric history (20% vs. 10%).

- Were more often intubated (37% vs. 20%).

- Had a longer length of hospital stay (7.9 vs. 6.0 days).

- Were less often discharged home (25% vs. 66%).

“It’s no surprise that older patients and people with dementia or psychiatric illness are predisposed to becoming encephalopathic,” said Dr. Frontera. “Being in a foreign environment, such as a hospital, or being sleep-deprived in the ICU is likely to make them more confused during their hospital stay.”

Delirium as a symptom

In-hospital mortality or discharge to hospice was considerably higher in the TME versus non-TME patients (44% vs. 18%, respectively).

When the researchers adjusted for confounders (age, sex, race, worse Sequential Organ Failure Assessment score during hospitalization, ventilator status, study week, hospital location, and ICU care level) and excluded patients receiving only comfort care, they found that TME was associated with a 24% increased risk of in-hospital death (30% in patients with TME vs. 16% in those without TME).

The highest mortality risk was associated with hypoxemia, with 42% of patients with HIE dying during hospitalization, compared with 16% of patients without HIE (adjusted hazard ratio 1.56; 95% confidence interval, 1.21-2.00; P = .001).

“Not all patients who are intubated require sedation, but there’s generally a lot of hesitation in reducing or stopping sedation in some patients,” Dr. Frontera observed.

She acknowledged there are “many extremely sick patients whom you can’t ventilate without sedation.”

Nevertheless, “delirium in and of itself does not cause death. It’s a symptom, not a disease, and we have to figure out what causes it. Delirium might not need to be sedated, and it’s more important to see what the causal problem is.”

Independent predictor of death

Commenting on the study, Panayiotis N. Varelas, MD, PhD, vice president of the Neurocritical Care Society, said the study “approached the TME issue better than previously, namely allowing time for sedatives to wear off to have a better sample of patients with this syndrome.”

Dr. Varelas, who is chairman of the department of neurology and professor of neurology at Albany (N.Y.) Medical College, emphasized that TME “is not benign and, in patients with COVID-19, it is an independent predictor of in-hospital mortality.”

“One should take all possible measures … to avoid desaturation and hypotensive episodes and also aggressively treat SAE and uremic encephalopathy in hopes of improving the outcomes,” added Dr. Varelas, who was not involved with the study.

Also commenting on the study, Mitchell Elkind, MD, professor of neurology and epidemiology at Columbia University in New York, who was not associated with the research, said it “nicely distinguishes among the different causes of encephalopathy, including sepsis, hypoxia, and kidney failure … emphasizing just how sick these patients are.”

The study received no direct funding. Individual investigators were supported by grants from the National Institute on Aging and the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke. The investigators, Dr. Varelas, and Dr. Elkind have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

, new research shows. Results of a retrospective study show that of almost 4,500 patients with COVID-19, 12% were diagnosed with TME. Of these, 78% developed encephalopathy immediately prior to hospital admission. Septic encephalopathy, hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy (HIE), and uremia were the most common causes, although multiple causes were present in close to 80% of patients. TME was also associated with a 24% higher risk of in-hospital death.

“We found that close to one in eight patients who were hospitalized with COVID-19 had TME that was not attributed to the effects of sedatives, and that this is incredibly common among these patients who are critically ill” said lead author Jennifer A. Frontera, MD, New York University.

“The general principle of our findings is to be more aggressive in TME; and from a neurologist perspective, the way to do this is to eliminate the effects of sedation, which is a confounder,” she said.

The study was published online March 16 in Neurocritical Care.

Drilling down

“Many neurological complications of COVID-19 are sequelae of severe illness or secondary effects of multisystem organ failure, but our previous work identified TME as the most common neurological complication,” Dr. Frontera said.

Previous research investigating encephalopathy among patients with COVID-19 included patients who may have been sedated or have had a positive Confusion Assessment Method (CAM) result.

“A lot of the delirium literature is effectively heterogeneous because there are a number of patients who are on sedative medication that, if you could turn it off, these patients would return to normal. Some may have underlying neurological issues that can be addressed, but you can›t get to the bottom of this unless you turn off the sedation,” Dr. Frontera noted.

“We wanted to be specific and try to drill down to see what the underlying cause of the encephalopathy was,” she said.

The researchers retrospectively analyzed data on 4,491 patients (≥ 18 years old) with COVID-19 who were admitted to four New York City hospitals between March 1, 2020, and May 20, 2020. Of these, 559 (12%) with TME were compared with 3,932 patients without TME.

The researchers looked at index admissions and included patients who had:

- New changes in mental status or significant worsening of mental status (in patients with baseline abnormal mental status).

- Hyperglycemia or with transient focal neurologic deficits that resolved with glucose correction.

- An adequate washout of sedating medications (when relevant) prior to mental status assessment.

Potential etiologies included electrolyte abnormalities, organ failure, hypertensive encephalopathy, sepsis or active infection, fever, nutritional deficiency, and environmental injury.

Foreign environment

Most (78%) of the 559 patients diagnosed with TME had already developed encephalopathy immediately prior to hospital admission, the authors report. The most common etiologies of TME among hospitalized patients with COVID-19 are listed below.

Compared with patients without TME, those with TME – (all Ps < .001):

- Were older (76 vs. 62 years).

- Had higher rates of dementia (27% vs. 3%).

- Had higher rates of psychiatric history (20% vs. 10%).

- Were more often intubated (37% vs. 20%).

- Had a longer length of hospital stay (7.9 vs. 6.0 days).

- Were less often discharged home (25% vs. 66%).

“It’s no surprise that older patients and people with dementia or psychiatric illness are predisposed to becoming encephalopathic,” said Dr. Frontera. “Being in a foreign environment, such as a hospital, or being sleep-deprived in the ICU is likely to make them more confused during their hospital stay.”

Delirium as a symptom

In-hospital mortality or discharge to hospice was considerably higher in the TME versus non-TME patients (44% vs. 18%, respectively).

When the researchers adjusted for confounders (age, sex, race, worse Sequential Organ Failure Assessment score during hospitalization, ventilator status, study week, hospital location, and ICU care level) and excluded patients receiving only comfort care, they found that TME was associated with a 24% increased risk of in-hospital death (30% in patients with TME vs. 16% in those without TME).

The highest mortality risk was associated with hypoxemia, with 42% of patients with HIE dying during hospitalization, compared with 16% of patients without HIE (adjusted hazard ratio 1.56; 95% confidence interval, 1.21-2.00; P = .001).

“Not all patients who are intubated require sedation, but there’s generally a lot of hesitation in reducing or stopping sedation in some patients,” Dr. Frontera observed.

She acknowledged there are “many extremely sick patients whom you can’t ventilate without sedation.”

Nevertheless, “delirium in and of itself does not cause death. It’s a symptom, not a disease, and we have to figure out what causes it. Delirium might not need to be sedated, and it’s more important to see what the causal problem is.”

Independent predictor of death

Commenting on the study, Panayiotis N. Varelas, MD, PhD, vice president of the Neurocritical Care Society, said the study “approached the TME issue better than previously, namely allowing time for sedatives to wear off to have a better sample of patients with this syndrome.”

Dr. Varelas, who is chairman of the department of neurology and professor of neurology at Albany (N.Y.) Medical College, emphasized that TME “is not benign and, in patients with COVID-19, it is an independent predictor of in-hospital mortality.”

“One should take all possible measures … to avoid desaturation and hypotensive episodes and also aggressively treat SAE and uremic encephalopathy in hopes of improving the outcomes,” added Dr. Varelas, who was not involved with the study.

Also commenting on the study, Mitchell Elkind, MD, professor of neurology and epidemiology at Columbia University in New York, who was not associated with the research, said it “nicely distinguishes among the different causes of encephalopathy, including sepsis, hypoxia, and kidney failure … emphasizing just how sick these patients are.”

The study received no direct funding. Individual investigators were supported by grants from the National Institute on Aging and the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke. The investigators, Dr. Varelas, and Dr. Elkind have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM NEUROCRITICAL CARE

Huge, struggling breast cancer screening trial gets lifeline

But mammography trends can’t be ignored.

A controversial, big-budget breast cancer screening trial that has been chronically unable to attract enough female participants since its debut in 2017 got a vote of confidence from a special working group of the National Cancer Institute (NCI) on March 17.

The Tomosynthesis Mammography Imaging Screening Trial (TMIST) should continue, but with modification, the expert group concluded in its report.

The randomized trial, with an estimated cost of $100 million, compares two kinds of mammography screenings for breast cancer in healthy women. One group of patients is screened with digital breast tomosynthesis, also known as 3-D mammography; the other is screened with the older, less expensive 2-D digital technology.

Tomosynthesis is already considered superior in detecting small cancers and reducing callbacks and is increasingly being used in the real world, leading some experts in the field to say that TMIST is critically hampered by women’s and radiologists’ preference for 3-D mammography.

At a meeting of an NCI advisory board in September 2020, there was a suggestion that the federal agency may kill the trial.

But at the latest meeting, the working group proposed that the trial should live on.

One of the main problems with the trial has been recruitment; the recommended changes discussed at the meeting include reducing the number of women needed in the study (from 165,000 to 102,000), which would allow patient “accrual to be completed more quickly,” the working group noted. In addition, the target date for completing patient accrual would be moved to 2023, 3 years after the original completion date of 2020.

The group’s recommendations now go to NCI staff for scientific review. The NCI will then decide about implementing the proposed changes.

The trial, which is the NCI’s largest and most expensive screening study, has never come close to targeted monthly enrollment. It was enrolling fewer than 1,500 patients per month over a 2-year period, instead of the projected 5,500 per month, Philip Castle, PhD, MPH, director of the NCI’s Division of Cancer Prevention, said last year. He called for a review of TMIST’s “feasibility and relevance” in view of the increasing use of tomosynthesis in the United States, as well as other factors.

The new technology has been “rapidly adopted” by facilities in North America, the working group noted. As of December 2020, approximately 74% of breast cancer screening clinics in the United States had at least one tomosynthesis or 3-D system; 42% of the mammography machines were 3-D.

This trend of increasing use of 3-D machines might be too much for TMIST to surmount, said Nancy Davidson, MD, of the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, in Seattle, who chaired the working group.

“We are worried the challenges [to patient accrual] may persist due to the increasing adoption of three-dimensional breast tomosynthesis in the United States over time,” she said during the working group’s virtual presentation of the report to the NCI’s Clinical Trials and Translational Research Advisory Committee.

Committee member Smita Bhatia, MD, PhD, of the University of Alabama at Birmingham, wondered, “What are the ongoing barriers that [TMIST investigators] are going to face beside recruitment?”

Dr. Davidson answered by speaking, again, about market penetration of tomosynthesis machines and suggested that the recruitment problems and the availability of 3-D mammography are intertwined.

“Is this a technology that has or will arrive, at which point it may not be very easy to put the genie back in the bottle?” she asked.

That question has already been answered – widespread use of tomosynthesis is here to stay, argued Daniel Kopans, MD, of Harvard Medical School, Boston, who invented digital breast tomosynthesis but no longer benefits financially from his invention because the patent has expired.

“The horse is out of the barn,” Dr. Kopans said in an interview. By the time the study results are available, digital mammography will be a tool of the past, he said.

TMIST is a trial “that should never have been started in the first place, and it’s failing,” he said. “I was hoping they [the NCI] would say, ‘Let’s stop this because there’s not enough accrual.’ But it looks like they’re not.”

“TMIST is a waste of money,” said Dr. Kopans, repeating a criticism he has made in the past.

A drop in study power

The new recommendations for TMIST come about 1 year after Medscape Medical News reported that the study was lagging in enrollment of both patients and participating sites/physicians.

Last year, two TMIST study investigators said it had been difficult enlisting sites, in part because many radiologists and facilities – informed by their experience and previous research results – already believe that the 3-D technology is superior.

Currently, most 3-D systems are used in conjunction with 2-D. First, two static images of the breast are taken (2-D), and then the unit moves in an arc, taking multiple images of the breast (3-D). Thus, 3-D is widely described as allowing clinicians to flip through the images like “pages in a book” and as offering a superior read of the breast.

The NCI working group concedes that “there is evidence that screening utilizing tomosynthesis may reduce recall rates and improve cancer detection,” but it says the trial is needed to address “questions that still remain regarding the overall benefit to patients.”

Furthermore, tomosynthesis “may carry higher out-of-pocket costs for women and is more labor intensive and costly for health care systems in that it requires about twice as much reader time for interpretation,” the working group said.

The “main hypothesis of TMIST” is that “tomosynthesis will decrease the cumulative incidence of advanced breast cancers, a surrogate for mortality, compared to standard digital mammography,” posits the group.

Advanced breast cancer is defined in TMIST as invasive breast cancers that meet any of the following criteria:

- Distant metastases

- At least one lymph node macrometastasis

- Tumor size >1 cm and triple-negative or positive for human epidermal growth factor receptor

- Tumor size ≥ 20 mm unless of pure mucinous or other favorable histologies.

In the original study design, the sample size was estimated to be sufficient to provide 90% power to detect a 20% relative reduction in the proportion of advanced cancers in the intervention arm (tomosynthesis, or 3-D) compared to the control arm (digital mammography, or 2-D) 4.5 years from randomization.

Now, with fewer patients and a revised analytic approach, the study’s statistical power will be decreased to 80% from the original 90%.

Also, an advanced cancer is counted “if it occurs at any time while the participant is on study.”

Dr. Kopans says that is a problem.

“That is a huge mistake, since digital breast tomosynthesis cannot impact prevalent cancers. They are already there. This means that their ‘power calculation’ is wrong, and they won’t have the power that they are claiming,” he said.

Dr. Kopans explained that the first screen in TMIST will have “no effect on the number of advanced cancers.” That’s because the cancers will have already grown enough to become advanced, he said.

On the other hand, an initial screening might detect and thus lead to the removal of nonadvanced, smaller cancers, which, had they not been detected and removed, would have grown to become advanced cancers by the next year. Thus, the screenings done after the first year are the ones that potentially prove the effect of the intervention.

However, the working group report says that changes to the study will not affect anything other than a 10% reduction in the study’s power.

The working group is concerned about TMIST going on for years and years. For that reason, they recommended that the NCI establish “strict criteria for termination of the study” if accrual goals are not met. However, those parameters have not been developed, and it was not part of the study group’s mission to establish them.

The working group was sponsored by the NCI. Dr. Kopans reports consulting with DART Imaging in China.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

But mammography trends can’t be ignored.

But mammography trends can’t be ignored.

A controversial, big-budget breast cancer screening trial that has been chronically unable to attract enough female participants since its debut in 2017 got a vote of confidence from a special working group of the National Cancer Institute (NCI) on March 17.

The Tomosynthesis Mammography Imaging Screening Trial (TMIST) should continue, but with modification, the expert group concluded in its report.

The randomized trial, with an estimated cost of $100 million, compares two kinds of mammography screenings for breast cancer in healthy women. One group of patients is screened with digital breast tomosynthesis, also known as 3-D mammography; the other is screened with the older, less expensive 2-D digital technology.

Tomosynthesis is already considered superior in detecting small cancers and reducing callbacks and is increasingly being used in the real world, leading some experts in the field to say that TMIST is critically hampered by women’s and radiologists’ preference for 3-D mammography.

At a meeting of an NCI advisory board in September 2020, there was a suggestion that the federal agency may kill the trial.

But at the latest meeting, the working group proposed that the trial should live on.

One of the main problems with the trial has been recruitment; the recommended changes discussed at the meeting include reducing the number of women needed in the study (from 165,000 to 102,000), which would allow patient “accrual to be completed more quickly,” the working group noted. In addition, the target date for completing patient accrual would be moved to 2023, 3 years after the original completion date of 2020.

The group’s recommendations now go to NCI staff for scientific review. The NCI will then decide about implementing the proposed changes.

The trial, which is the NCI’s largest and most expensive screening study, has never come close to targeted monthly enrollment. It was enrolling fewer than 1,500 patients per month over a 2-year period, instead of the projected 5,500 per month, Philip Castle, PhD, MPH, director of the NCI’s Division of Cancer Prevention, said last year. He called for a review of TMIST’s “feasibility and relevance” in view of the increasing use of tomosynthesis in the United States, as well as other factors.

The new technology has been “rapidly adopted” by facilities in North America, the working group noted. As of December 2020, approximately 74% of breast cancer screening clinics in the United States had at least one tomosynthesis or 3-D system; 42% of the mammography machines were 3-D.

This trend of increasing use of 3-D machines might be too much for TMIST to surmount, said Nancy Davidson, MD, of the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, in Seattle, who chaired the working group.

“We are worried the challenges [to patient accrual] may persist due to the increasing adoption of three-dimensional breast tomosynthesis in the United States over time,” she said during the working group’s virtual presentation of the report to the NCI’s Clinical Trials and Translational Research Advisory Committee.

Committee member Smita Bhatia, MD, PhD, of the University of Alabama at Birmingham, wondered, “What are the ongoing barriers that [TMIST investigators] are going to face beside recruitment?”

Dr. Davidson answered by speaking, again, about market penetration of tomosynthesis machines and suggested that the recruitment problems and the availability of 3-D mammography are intertwined.

“Is this a technology that has or will arrive, at which point it may not be very easy to put the genie back in the bottle?” she asked.

That question has already been answered – widespread use of tomosynthesis is here to stay, argued Daniel Kopans, MD, of Harvard Medical School, Boston, who invented digital breast tomosynthesis but no longer benefits financially from his invention because the patent has expired.

“The horse is out of the barn,” Dr. Kopans said in an interview. By the time the study results are available, digital mammography will be a tool of the past, he said.

TMIST is a trial “that should never have been started in the first place, and it’s failing,” he said. “I was hoping they [the NCI] would say, ‘Let’s stop this because there’s not enough accrual.’ But it looks like they’re not.”

“TMIST is a waste of money,” said Dr. Kopans, repeating a criticism he has made in the past.

A drop in study power

The new recommendations for TMIST come about 1 year after Medscape Medical News reported that the study was lagging in enrollment of both patients and participating sites/physicians.

Last year, two TMIST study investigators said it had been difficult enlisting sites, in part because many radiologists and facilities – informed by their experience and previous research results – already believe that the 3-D technology is superior.

Currently, most 3-D systems are used in conjunction with 2-D. First, two static images of the breast are taken (2-D), and then the unit moves in an arc, taking multiple images of the breast (3-D). Thus, 3-D is widely described as allowing clinicians to flip through the images like “pages in a book” and as offering a superior read of the breast.

The NCI working group concedes that “there is evidence that screening utilizing tomosynthesis may reduce recall rates and improve cancer detection,” but it says the trial is needed to address “questions that still remain regarding the overall benefit to patients.”

Furthermore, tomosynthesis “may carry higher out-of-pocket costs for women and is more labor intensive and costly for health care systems in that it requires about twice as much reader time for interpretation,” the working group said.

The “main hypothesis of TMIST” is that “tomosynthesis will decrease the cumulative incidence of advanced breast cancers, a surrogate for mortality, compared to standard digital mammography,” posits the group.

Advanced breast cancer is defined in TMIST as invasive breast cancers that meet any of the following criteria:

- Distant metastases

- At least one lymph node macrometastasis

- Tumor size >1 cm and triple-negative or positive for human epidermal growth factor receptor

- Tumor size ≥ 20 mm unless of pure mucinous or other favorable histologies.

In the original study design, the sample size was estimated to be sufficient to provide 90% power to detect a 20% relative reduction in the proportion of advanced cancers in the intervention arm (tomosynthesis, or 3-D) compared to the control arm (digital mammography, or 2-D) 4.5 years from randomization.

Now, with fewer patients and a revised analytic approach, the study’s statistical power will be decreased to 80% from the original 90%.

Also, an advanced cancer is counted “if it occurs at any time while the participant is on study.”

Dr. Kopans says that is a problem.

“That is a huge mistake, since digital breast tomosynthesis cannot impact prevalent cancers. They are already there. This means that their ‘power calculation’ is wrong, and they won’t have the power that they are claiming,” he said.

Dr. Kopans explained that the first screen in TMIST will have “no effect on the number of advanced cancers.” That’s because the cancers will have already grown enough to become advanced, he said.

On the other hand, an initial screening might detect and thus lead to the removal of nonadvanced, smaller cancers, which, had they not been detected and removed, would have grown to become advanced cancers by the next year. Thus, the screenings done after the first year are the ones that potentially prove the effect of the intervention.

However, the working group report says that changes to the study will not affect anything other than a 10% reduction in the study’s power.

The working group is concerned about TMIST going on for years and years. For that reason, they recommended that the NCI establish “strict criteria for termination of the study” if accrual goals are not met. However, those parameters have not been developed, and it was not part of the study group’s mission to establish them.

The working group was sponsored by the NCI. Dr. Kopans reports consulting with DART Imaging in China.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

A controversial, big-budget breast cancer screening trial that has been chronically unable to attract enough female participants since its debut in 2017 got a vote of confidence from a special working group of the National Cancer Institute (NCI) on March 17.

The Tomosynthesis Mammography Imaging Screening Trial (TMIST) should continue, but with modification, the expert group concluded in its report.

The randomized trial, with an estimated cost of $100 million, compares two kinds of mammography screenings for breast cancer in healthy women. One group of patients is screened with digital breast tomosynthesis, also known as 3-D mammography; the other is screened with the older, less expensive 2-D digital technology.

Tomosynthesis is already considered superior in detecting small cancers and reducing callbacks and is increasingly being used in the real world, leading some experts in the field to say that TMIST is critically hampered by women’s and radiologists’ preference for 3-D mammography.

At a meeting of an NCI advisory board in September 2020, there was a suggestion that the federal agency may kill the trial.

But at the latest meeting, the working group proposed that the trial should live on.

One of the main problems with the trial has been recruitment; the recommended changes discussed at the meeting include reducing the number of women needed in the study (from 165,000 to 102,000), which would allow patient “accrual to be completed more quickly,” the working group noted. In addition, the target date for completing patient accrual would be moved to 2023, 3 years after the original completion date of 2020.

The group’s recommendations now go to NCI staff for scientific review. The NCI will then decide about implementing the proposed changes.

The trial, which is the NCI’s largest and most expensive screening study, has never come close to targeted monthly enrollment. It was enrolling fewer than 1,500 patients per month over a 2-year period, instead of the projected 5,500 per month, Philip Castle, PhD, MPH, director of the NCI’s Division of Cancer Prevention, said last year. He called for a review of TMIST’s “feasibility and relevance” in view of the increasing use of tomosynthesis in the United States, as well as other factors.

The new technology has been “rapidly adopted” by facilities in North America, the working group noted. As of December 2020, approximately 74% of breast cancer screening clinics in the United States had at least one tomosynthesis or 3-D system; 42% of the mammography machines were 3-D.

This trend of increasing use of 3-D machines might be too much for TMIST to surmount, said Nancy Davidson, MD, of the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, in Seattle, who chaired the working group.

“We are worried the challenges [to patient accrual] may persist due to the increasing adoption of three-dimensional breast tomosynthesis in the United States over time,” she said during the working group’s virtual presentation of the report to the NCI’s Clinical Trials and Translational Research Advisory Committee.

Committee member Smita Bhatia, MD, PhD, of the University of Alabama at Birmingham, wondered, “What are the ongoing barriers that [TMIST investigators] are going to face beside recruitment?”

Dr. Davidson answered by speaking, again, about market penetration of tomosynthesis machines and suggested that the recruitment problems and the availability of 3-D mammography are intertwined.

“Is this a technology that has or will arrive, at which point it may not be very easy to put the genie back in the bottle?” she asked.

That question has already been answered – widespread use of tomosynthesis is here to stay, argued Daniel Kopans, MD, of Harvard Medical School, Boston, who invented digital breast tomosynthesis but no longer benefits financially from his invention because the patent has expired.

“The horse is out of the barn,” Dr. Kopans said in an interview. By the time the study results are available, digital mammography will be a tool of the past, he said.

TMIST is a trial “that should never have been started in the first place, and it’s failing,” he said. “I was hoping they [the NCI] would say, ‘Let’s stop this because there’s not enough accrual.’ But it looks like they’re not.”

“TMIST is a waste of money,” said Dr. Kopans, repeating a criticism he has made in the past.

A drop in study power

The new recommendations for TMIST come about 1 year after Medscape Medical News reported that the study was lagging in enrollment of both patients and participating sites/physicians.

Last year, two TMIST study investigators said it had been difficult enlisting sites, in part because many radiologists and facilities – informed by their experience and previous research results – already believe that the 3-D technology is superior.

Currently, most 3-D systems are used in conjunction with 2-D. First, two static images of the breast are taken (2-D), and then the unit moves in an arc, taking multiple images of the breast (3-D). Thus, 3-D is widely described as allowing clinicians to flip through the images like “pages in a book” and as offering a superior read of the breast.

The NCI working group concedes that “there is evidence that screening utilizing tomosynthesis may reduce recall rates and improve cancer detection,” but it says the trial is needed to address “questions that still remain regarding the overall benefit to patients.”

Furthermore, tomosynthesis “may carry higher out-of-pocket costs for women and is more labor intensive and costly for health care systems in that it requires about twice as much reader time for interpretation,” the working group said.

The “main hypothesis of TMIST” is that “tomosynthesis will decrease the cumulative incidence of advanced breast cancers, a surrogate for mortality, compared to standard digital mammography,” posits the group.

Advanced breast cancer is defined in TMIST as invasive breast cancers that meet any of the following criteria:

- Distant metastases

- At least one lymph node macrometastasis

- Tumor size >1 cm and triple-negative or positive for human epidermal growth factor receptor

- Tumor size ≥ 20 mm unless of pure mucinous or other favorable histologies.

In the original study design, the sample size was estimated to be sufficient to provide 90% power to detect a 20% relative reduction in the proportion of advanced cancers in the intervention arm (tomosynthesis, or 3-D) compared to the control arm (digital mammography, or 2-D) 4.5 years from randomization.

Now, with fewer patients and a revised analytic approach, the study’s statistical power will be decreased to 80% from the original 90%.

Also, an advanced cancer is counted “if it occurs at any time while the participant is on study.”

Dr. Kopans says that is a problem.

“That is a huge mistake, since digital breast tomosynthesis cannot impact prevalent cancers. They are already there. This means that their ‘power calculation’ is wrong, and they won’t have the power that they are claiming,” he said.

Dr. Kopans explained that the first screen in TMIST will have “no effect on the number of advanced cancers.” That’s because the cancers will have already grown enough to become advanced, he said.

On the other hand, an initial screening might detect and thus lead to the removal of nonadvanced, smaller cancers, which, had they not been detected and removed, would have grown to become advanced cancers by the next year. Thus, the screenings done after the first year are the ones that potentially prove the effect of the intervention.

However, the working group report says that changes to the study will not affect anything other than a 10% reduction in the study’s power.

The working group is concerned about TMIST going on for years and years. For that reason, they recommended that the NCI establish “strict criteria for termination of the study” if accrual goals are not met. However, those parameters have not been developed, and it was not part of the study group’s mission to establish them.

The working group was sponsored by the NCI. Dr. Kopans reports consulting with DART Imaging in China.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Could tamoxifen dose be slashed down to 2.5 mg?

Tamoxifen has long been used in breast cancer, both in the adjuvant and preventive setting, but uptake and adherence are notoriously low, mainly because of adverse events.

Using a much lower dose to reduce the incidence of side effects would be a “way forward,” reasoned Swedish researchers. They report that a substantially lower dose of tamoxifen (2.5 mg) may be as effective as the standard dose (20 mg), but reduced by half the incidence of severe vasomotor symptoms, including hot flashes, cold sweats, and night sweats.

The research was published online March 18 in the Journal of Clinical Oncology.

The study involved 1,439 women (aged 40-74 years) who were participating in the Swedish mammography screening program and tested tamoxifen at various doses.

“We performed a dose determination study that we hope will initiate follow-up studies that in turn will influence both adjuvant treatment and prevention of breast cancer,” said lead author Per Hall, MD, PhD, head of the department of medical epidemiology and biostatistics at Karolinska Institutet in Stockholm.

The study measured the effects of the different doses (1, 2.5, 5, 10, and 20 mg) on mammographic breast density.

Dr. Hall emphasized that breast density was used as a proxy for therapy response. “We do not know how that translates to actual clinical effect,” he said in an interview. “This is step one.”

Previous studies have also used breast density changes as a proxy endpoint for tamoxifen therapy response, in both prophylactic and adjuvant settings, the authors note. There is some data to suggest that this does translate to a clinical effect. A recent study showed that tamoxifen at 5 mg/day taken for 3 years reduced the recurrence of breast intraepithelial neoplasia by 50% and contralateral breast cancer by 75%, with a symptom profile similar to placebo (J Clin Oncol. 2019;37:1629-1637).

Lower density, fewer symptoms

In the current study, Dr. Hall and colleagues found that the mammographic breast density (mean overall area) was decreased by 9.6% in the 20 mg tamoxifen group, and similar decreases were seen in the 2.5 and 10 mg dose groups, but not in the placebo and 1 mg dose groups.

These changes were driven primarily by changes observed among premenopausal women where the 20 mg mean decrease was 18.5% (P < .001 for interaction with menopausal status) with decreases of 13.4% in the 2.5 mg group, 19.6% in the 5 mg group, and 17% in the 10 mg group.

The results were quite different in postmenopausal participants, where those who received the 20 mg dose had a density mean decrease of 4%, which was not substantially different to the placebo, 1 mg, 2.5 mg, and 10 mg treatment arms.

The authors point out that the difference in density decrease between premenopausal and postmenopausal women was not dependent on differences in baseline density.

When reviewing adverse events with the various doses, the team found a large decrease in severe vasomotor symptoms with the lower doses of tamoxifen. These adverse events were reported by 34% of women taking 20 mg, 24.4% on 5 mg, 20.5% on 2.5 mg, 18.5% on 1 mg, and 13.7% of women taking placebo. There were no similar trends seen for gynecologic, sexual, or musculoskeletal symptoms.