User login

New steroid dosing regimen for myasthenia gravis

. The trial showed that the conventional slow tapering regimen enabled discontinuation of prednisone earlier than previously reported but the new rapid-tapering regimen enabled an even faster discontinuation.

Noting that although both regimens led to a comparable myasthenia gravis status and prednisone dose at 15 months, the authors stated: “We think that the reduction of the cumulative dose over a year (equivalent to 5 mg/day) is a clinically relevant reduction, since the risk of complications is proportional to the daily or cumulative doses of prednisone.

“Our results warrant testing of a more rapid-tapering regimen in a future trial. In the meantime, our trial provides useful information on how prednisone tapering could be managed in patients with generalized myasthenia gravis treated with azathioprine,” they concluded.

The trial was published online Feb. 8 in JAMA Neurology.

Myasthenia gravis is a disorder of neuromuscular transmission, resulting from autoantibodies to components of the neuromuscular junction, most commonly the acetylcholine receptor. The incidence ranges from 0.3 to 2.8 per 100,000, and it is estimated to affect more than 700,000 people worldwide.

The authors of the current paper, led by Tarek Sharshar, MD, PhD, Groupe Hospitalier Universitaire, Paris, explained that many patients whose symptoms are not controlled by cholinesterase inhibitors are treated with corticosteroids and an immunosuppressant, usually azathioprine. No specific dosing protocol for prednisone has been validated, but it is commonly gradually increased to 0.75 mg/kg on alternate days and reduced progressively when minimal manifestation status (MMS; no symptoms or functional limitations) is reached.

They noted that this regimen leads to high and prolonged corticosteroid treatment – often for several years – with the mean daily prednisone dose exceeding 30 mg/day at 15 months and 20 mg/day at 36 months. As long-term use of corticosteroids is often associated with significant complications, reducing or even discontinuing prednisone treatment without destabilizing myasthenia gravis is therefore a therapeutic goal.

Evaluating dosage regimens

To investigate whether different dosage regimens could help wean patients with generalized myasthenia gravis from corticosteroid therapy without compromising efficacy, the researchers conducted this study in which the current recommended regimen was compared with an approach using higher initial corticosteroid doses followed by rapid tapering.

In the conventional slow-tapering group (control group), prednisone was given on alternate days, starting at a dose of 10 mg then increased by increments of 10 mg every 2 days up to 1.5 mg/kg on alternate days without exceeding 100 mg. This dose was maintained until MMS was reached and then reduced by 10 mg every 2 weeks until a dosage of 40 mg was reached, with subsequent slowing of the taper to 5 mg monthly. If MMS was not maintained, the alternate-day prednisone dose was increased by 10 mg every 2 weeks until MMS was restored, and the tapering resumed 4 weeks later.

In the new rapid-tapering group, oral prednisone was immediately started at 0.75 mg/kg per day, and this was followed by an earlier and rapid decrease once improved myasthenia gravis status was attained. Three different tapering schedules were applied dependent on the improvement status of the patient.

First, If the patient reached MMS at 1 month, the dose of prednisone was reduced by 0.1 mg/kg every 10 days up to 0.45 mg/kg per day, then 0.05 mg/kg every 10 days up to 0.25 mg/kg per day, then in decrements of 1 mg by adjusting the duration of the decrements according to the participant’s weight with the aim of achieving complete cessation of corticosteroid therapy within 18-20 weeks for this third stage of tapering.

Second, if the state of MMS was not reached at 1 month but the participant had improved, a slower tapering was conducted, with the dosage reduced in a similar way to the first instance but with each reduction introduced every 20 days. If the participant reached MMS during this tapering process, the tapering of prednisone was similar to the sequence described in the first group.

Third, if MMS was not reached and the participant had not improved, the initial dose was maintained for the first 3 months; beyond that time, a decrease in the prednisone dose was undertaken as in the second group to a minimum dose of 0.25 mg/kg per day, after which the prednisone dose was not reduced further. If the patient improved, the tapering of prednisone followed the sequence described in the second category.

Reductions in prednisone dose could be accelerated in the case of severe prednisone adverse effects, according to the prescriber’s decision.

In the event of a myasthenia gravis exacerbation, the patient was hospitalized and the dose of prednisone was routinely doubled, or for a more moderate aggravation, the dose was increased to the previous dose recommended in the tapering regimen.

Azathioprine, up to a maximum dose of 3 mg/kg per day, was prescribed for all participants. In all, 117 patients were randomly assigned, and 113 completed the study.

The primary outcome was the proportion of participants having reached MMS without prednisone at 12 months and having not relapsed or taken prednisone between months 12 and 15. This was achieved by significantly more patients in the rapid-tapering group (39% vs. 9%; risk ratio, 3.61; P < .001).

Rapid tapering allowed sparing of a mean of 1,898 mg of prednisone over 1 year (5.3 mg/day) per patient.

The rate of myasthenia gravis exacerbation or worsening did not differ significantly between the two groups, nor did the use of plasmapheresis or IVIG or the doses of azathioprine.

The overall number of serious adverse events did not differ significantly between the two groups (slow tapering, 22% vs. rapid-tapering, 36%; P = .15).

The researchers said it is possible that prednisone tapering would differ with another immunosuppressive agent but as azathioprine is the first-line immunosuppressant usually recommended, these results are relevant for a large proportion of patients.

They said the better outcome of the intervention group could have been related to one or more of four differences in prednisone administration: An immediate high dose versus a slow increase of the prednisone dose; daily versus alternate-day dosing; earlier tapering initiation; and faster tapering. However, the structure of the study did not allow identification of which of these factors was responsible.

“Researching the best prednisone-tapering scheme is not only a major issue for patients with myasthenia gravis but also for other autoimmune or inflammatory diseases, because validated prednisone-tapering regimens are scarce,” the authors said.

The rapid tapering of prednisone therapy appears to be feasible, beneficial, and safe in patients with generalized myasthenia gravis and “warrants testing in other autoimmune diseases,” they added.

Particularly relevant to late-onset disease

Commenting on the study, Raffi Topakian, MD, Klinikum Wels-Grieskirchen, Wels, Austria, said the results showed that in patients with moderate to severe generalized myasthenia gravis requiring high-dose prednisone, azathioprine, a widely used immunosuppressant, may have a quicker steroid-sparing effect than previously thought, and that rapid steroid tapering can be achieved safely, resulting in a reduction of the cumulative steroid dose over a year despite higher initial doses.

Dr. Topakian, who was not involved with the research, pointed out that the median age was advanced (around 56 years), and the benefit of a regimen that leads to a reduction of the cumulative steroid dose over a year may be disproportionately larger for older, sicker patients with many comorbidities who are at considerably higher risk for a prednisone-induced increase in cardiovascular complications, osteoporotic fractures, and gastrointestinal bleeding.

“The study findings are particularly relevant for the management of late-onset myasthenia gravis (when first symptoms start after age 45-50 years), which is being encountered more frequently over the past years,” he said.

“But the holy grail of myasthenia gravis treatment has not been found yet,” Dr. Topakian noted. “Disappointingly, rapid tapering of steroids (compared to slow tapering) resulted in a reduction of the cumulative steroid dose only, but was not associated with better myasthenia gravis functional status or lower doses of steroids at 15 months. To my view, this finding points to the limited immunosuppressive efficacy of azathioprine.”

He added that the study findings should not be extrapolated to patients with mild presentations or to those with muscle-specific kinase myasthenia gravis.

Dr. Sharshar disclosed no relevant financial relationships. Disclosures for the study coauthors appear in the original article.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

. The trial showed that the conventional slow tapering regimen enabled discontinuation of prednisone earlier than previously reported but the new rapid-tapering regimen enabled an even faster discontinuation.

Noting that although both regimens led to a comparable myasthenia gravis status and prednisone dose at 15 months, the authors stated: “We think that the reduction of the cumulative dose over a year (equivalent to 5 mg/day) is a clinically relevant reduction, since the risk of complications is proportional to the daily or cumulative doses of prednisone.

“Our results warrant testing of a more rapid-tapering regimen in a future trial. In the meantime, our trial provides useful information on how prednisone tapering could be managed in patients with generalized myasthenia gravis treated with azathioprine,” they concluded.

The trial was published online Feb. 8 in JAMA Neurology.

Myasthenia gravis is a disorder of neuromuscular transmission, resulting from autoantibodies to components of the neuromuscular junction, most commonly the acetylcholine receptor. The incidence ranges from 0.3 to 2.8 per 100,000, and it is estimated to affect more than 700,000 people worldwide.

The authors of the current paper, led by Tarek Sharshar, MD, PhD, Groupe Hospitalier Universitaire, Paris, explained that many patients whose symptoms are not controlled by cholinesterase inhibitors are treated with corticosteroids and an immunosuppressant, usually azathioprine. No specific dosing protocol for prednisone has been validated, but it is commonly gradually increased to 0.75 mg/kg on alternate days and reduced progressively when minimal manifestation status (MMS; no symptoms or functional limitations) is reached.

They noted that this regimen leads to high and prolonged corticosteroid treatment – often for several years – with the mean daily prednisone dose exceeding 30 mg/day at 15 months and 20 mg/day at 36 months. As long-term use of corticosteroids is often associated with significant complications, reducing or even discontinuing prednisone treatment without destabilizing myasthenia gravis is therefore a therapeutic goal.

Evaluating dosage regimens

To investigate whether different dosage regimens could help wean patients with generalized myasthenia gravis from corticosteroid therapy without compromising efficacy, the researchers conducted this study in which the current recommended regimen was compared with an approach using higher initial corticosteroid doses followed by rapid tapering.

In the conventional slow-tapering group (control group), prednisone was given on alternate days, starting at a dose of 10 mg then increased by increments of 10 mg every 2 days up to 1.5 mg/kg on alternate days without exceeding 100 mg. This dose was maintained until MMS was reached and then reduced by 10 mg every 2 weeks until a dosage of 40 mg was reached, with subsequent slowing of the taper to 5 mg monthly. If MMS was not maintained, the alternate-day prednisone dose was increased by 10 mg every 2 weeks until MMS was restored, and the tapering resumed 4 weeks later.

In the new rapid-tapering group, oral prednisone was immediately started at 0.75 mg/kg per day, and this was followed by an earlier and rapid decrease once improved myasthenia gravis status was attained. Three different tapering schedules were applied dependent on the improvement status of the patient.

First, If the patient reached MMS at 1 month, the dose of prednisone was reduced by 0.1 mg/kg every 10 days up to 0.45 mg/kg per day, then 0.05 mg/kg every 10 days up to 0.25 mg/kg per day, then in decrements of 1 mg by adjusting the duration of the decrements according to the participant’s weight with the aim of achieving complete cessation of corticosteroid therapy within 18-20 weeks for this third stage of tapering.

Second, if the state of MMS was not reached at 1 month but the participant had improved, a slower tapering was conducted, with the dosage reduced in a similar way to the first instance but with each reduction introduced every 20 days. If the participant reached MMS during this tapering process, the tapering of prednisone was similar to the sequence described in the first group.

Third, if MMS was not reached and the participant had not improved, the initial dose was maintained for the first 3 months; beyond that time, a decrease in the prednisone dose was undertaken as in the second group to a minimum dose of 0.25 mg/kg per day, after which the prednisone dose was not reduced further. If the patient improved, the tapering of prednisone followed the sequence described in the second category.

Reductions in prednisone dose could be accelerated in the case of severe prednisone adverse effects, according to the prescriber’s decision.

In the event of a myasthenia gravis exacerbation, the patient was hospitalized and the dose of prednisone was routinely doubled, or for a more moderate aggravation, the dose was increased to the previous dose recommended in the tapering regimen.

Azathioprine, up to a maximum dose of 3 mg/kg per day, was prescribed for all participants. In all, 117 patients were randomly assigned, and 113 completed the study.

The primary outcome was the proportion of participants having reached MMS without prednisone at 12 months and having not relapsed or taken prednisone between months 12 and 15. This was achieved by significantly more patients in the rapid-tapering group (39% vs. 9%; risk ratio, 3.61; P < .001).

Rapid tapering allowed sparing of a mean of 1,898 mg of prednisone over 1 year (5.3 mg/day) per patient.

The rate of myasthenia gravis exacerbation or worsening did not differ significantly between the two groups, nor did the use of plasmapheresis or IVIG or the doses of azathioprine.

The overall number of serious adverse events did not differ significantly between the two groups (slow tapering, 22% vs. rapid-tapering, 36%; P = .15).

The researchers said it is possible that prednisone tapering would differ with another immunosuppressive agent but as azathioprine is the first-line immunosuppressant usually recommended, these results are relevant for a large proportion of patients.

They said the better outcome of the intervention group could have been related to one or more of four differences in prednisone administration: An immediate high dose versus a slow increase of the prednisone dose; daily versus alternate-day dosing; earlier tapering initiation; and faster tapering. However, the structure of the study did not allow identification of which of these factors was responsible.

“Researching the best prednisone-tapering scheme is not only a major issue for patients with myasthenia gravis but also for other autoimmune or inflammatory diseases, because validated prednisone-tapering regimens are scarce,” the authors said.

The rapid tapering of prednisone therapy appears to be feasible, beneficial, and safe in patients with generalized myasthenia gravis and “warrants testing in other autoimmune diseases,” they added.

Particularly relevant to late-onset disease

Commenting on the study, Raffi Topakian, MD, Klinikum Wels-Grieskirchen, Wels, Austria, said the results showed that in patients with moderate to severe generalized myasthenia gravis requiring high-dose prednisone, azathioprine, a widely used immunosuppressant, may have a quicker steroid-sparing effect than previously thought, and that rapid steroid tapering can be achieved safely, resulting in a reduction of the cumulative steroid dose over a year despite higher initial doses.

Dr. Topakian, who was not involved with the research, pointed out that the median age was advanced (around 56 years), and the benefit of a regimen that leads to a reduction of the cumulative steroid dose over a year may be disproportionately larger for older, sicker patients with many comorbidities who are at considerably higher risk for a prednisone-induced increase in cardiovascular complications, osteoporotic fractures, and gastrointestinal bleeding.

“The study findings are particularly relevant for the management of late-onset myasthenia gravis (when first symptoms start after age 45-50 years), which is being encountered more frequently over the past years,” he said.

“But the holy grail of myasthenia gravis treatment has not been found yet,” Dr. Topakian noted. “Disappointingly, rapid tapering of steroids (compared to slow tapering) resulted in a reduction of the cumulative steroid dose only, but was not associated with better myasthenia gravis functional status or lower doses of steroids at 15 months. To my view, this finding points to the limited immunosuppressive efficacy of azathioprine.”

He added that the study findings should not be extrapolated to patients with mild presentations or to those with muscle-specific kinase myasthenia gravis.

Dr. Sharshar disclosed no relevant financial relationships. Disclosures for the study coauthors appear in the original article.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

. The trial showed that the conventional slow tapering regimen enabled discontinuation of prednisone earlier than previously reported but the new rapid-tapering regimen enabled an even faster discontinuation.

Noting that although both regimens led to a comparable myasthenia gravis status and prednisone dose at 15 months, the authors stated: “We think that the reduction of the cumulative dose over a year (equivalent to 5 mg/day) is a clinically relevant reduction, since the risk of complications is proportional to the daily or cumulative doses of prednisone.

“Our results warrant testing of a more rapid-tapering regimen in a future trial. In the meantime, our trial provides useful information on how prednisone tapering could be managed in patients with generalized myasthenia gravis treated with azathioprine,” they concluded.

The trial was published online Feb. 8 in JAMA Neurology.

Myasthenia gravis is a disorder of neuromuscular transmission, resulting from autoantibodies to components of the neuromuscular junction, most commonly the acetylcholine receptor. The incidence ranges from 0.3 to 2.8 per 100,000, and it is estimated to affect more than 700,000 people worldwide.

The authors of the current paper, led by Tarek Sharshar, MD, PhD, Groupe Hospitalier Universitaire, Paris, explained that many patients whose symptoms are not controlled by cholinesterase inhibitors are treated with corticosteroids and an immunosuppressant, usually azathioprine. No specific dosing protocol for prednisone has been validated, but it is commonly gradually increased to 0.75 mg/kg on alternate days and reduced progressively when minimal manifestation status (MMS; no symptoms or functional limitations) is reached.

They noted that this regimen leads to high and prolonged corticosteroid treatment – often for several years – with the mean daily prednisone dose exceeding 30 mg/day at 15 months and 20 mg/day at 36 months. As long-term use of corticosteroids is often associated with significant complications, reducing or even discontinuing prednisone treatment without destabilizing myasthenia gravis is therefore a therapeutic goal.

Evaluating dosage regimens

To investigate whether different dosage regimens could help wean patients with generalized myasthenia gravis from corticosteroid therapy without compromising efficacy, the researchers conducted this study in which the current recommended regimen was compared with an approach using higher initial corticosteroid doses followed by rapid tapering.

In the conventional slow-tapering group (control group), prednisone was given on alternate days, starting at a dose of 10 mg then increased by increments of 10 mg every 2 days up to 1.5 mg/kg on alternate days without exceeding 100 mg. This dose was maintained until MMS was reached and then reduced by 10 mg every 2 weeks until a dosage of 40 mg was reached, with subsequent slowing of the taper to 5 mg monthly. If MMS was not maintained, the alternate-day prednisone dose was increased by 10 mg every 2 weeks until MMS was restored, and the tapering resumed 4 weeks later.

In the new rapid-tapering group, oral prednisone was immediately started at 0.75 mg/kg per day, and this was followed by an earlier and rapid decrease once improved myasthenia gravis status was attained. Three different tapering schedules were applied dependent on the improvement status of the patient.

First, If the patient reached MMS at 1 month, the dose of prednisone was reduced by 0.1 mg/kg every 10 days up to 0.45 mg/kg per day, then 0.05 mg/kg every 10 days up to 0.25 mg/kg per day, then in decrements of 1 mg by adjusting the duration of the decrements according to the participant’s weight with the aim of achieving complete cessation of corticosteroid therapy within 18-20 weeks for this third stage of tapering.

Second, if the state of MMS was not reached at 1 month but the participant had improved, a slower tapering was conducted, with the dosage reduced in a similar way to the first instance but with each reduction introduced every 20 days. If the participant reached MMS during this tapering process, the tapering of prednisone was similar to the sequence described in the first group.

Third, if MMS was not reached and the participant had not improved, the initial dose was maintained for the first 3 months; beyond that time, a decrease in the prednisone dose was undertaken as in the second group to a minimum dose of 0.25 mg/kg per day, after which the prednisone dose was not reduced further. If the patient improved, the tapering of prednisone followed the sequence described in the second category.

Reductions in prednisone dose could be accelerated in the case of severe prednisone adverse effects, according to the prescriber’s decision.

In the event of a myasthenia gravis exacerbation, the patient was hospitalized and the dose of prednisone was routinely doubled, or for a more moderate aggravation, the dose was increased to the previous dose recommended in the tapering regimen.

Azathioprine, up to a maximum dose of 3 mg/kg per day, was prescribed for all participants. In all, 117 patients were randomly assigned, and 113 completed the study.

The primary outcome was the proportion of participants having reached MMS without prednisone at 12 months and having not relapsed or taken prednisone between months 12 and 15. This was achieved by significantly more patients in the rapid-tapering group (39% vs. 9%; risk ratio, 3.61; P < .001).

Rapid tapering allowed sparing of a mean of 1,898 mg of prednisone over 1 year (5.3 mg/day) per patient.

The rate of myasthenia gravis exacerbation or worsening did not differ significantly between the two groups, nor did the use of plasmapheresis or IVIG or the doses of azathioprine.

The overall number of serious adverse events did not differ significantly between the two groups (slow tapering, 22% vs. rapid-tapering, 36%; P = .15).

The researchers said it is possible that prednisone tapering would differ with another immunosuppressive agent but as azathioprine is the first-line immunosuppressant usually recommended, these results are relevant for a large proportion of patients.

They said the better outcome of the intervention group could have been related to one or more of four differences in prednisone administration: An immediate high dose versus a slow increase of the prednisone dose; daily versus alternate-day dosing; earlier tapering initiation; and faster tapering. However, the structure of the study did not allow identification of which of these factors was responsible.

“Researching the best prednisone-tapering scheme is not only a major issue for patients with myasthenia gravis but also for other autoimmune or inflammatory diseases, because validated prednisone-tapering regimens are scarce,” the authors said.

The rapid tapering of prednisone therapy appears to be feasible, beneficial, and safe in patients with generalized myasthenia gravis and “warrants testing in other autoimmune diseases,” they added.

Particularly relevant to late-onset disease

Commenting on the study, Raffi Topakian, MD, Klinikum Wels-Grieskirchen, Wels, Austria, said the results showed that in patients with moderate to severe generalized myasthenia gravis requiring high-dose prednisone, azathioprine, a widely used immunosuppressant, may have a quicker steroid-sparing effect than previously thought, and that rapid steroid tapering can be achieved safely, resulting in a reduction of the cumulative steroid dose over a year despite higher initial doses.

Dr. Topakian, who was not involved with the research, pointed out that the median age was advanced (around 56 years), and the benefit of a regimen that leads to a reduction of the cumulative steroid dose over a year may be disproportionately larger for older, sicker patients with many comorbidities who are at considerably higher risk for a prednisone-induced increase in cardiovascular complications, osteoporotic fractures, and gastrointestinal bleeding.

“The study findings are particularly relevant for the management of late-onset myasthenia gravis (when first symptoms start after age 45-50 years), which is being encountered more frequently over the past years,” he said.

“But the holy grail of myasthenia gravis treatment has not been found yet,” Dr. Topakian noted. “Disappointingly, rapid tapering of steroids (compared to slow tapering) resulted in a reduction of the cumulative steroid dose only, but was not associated with better myasthenia gravis functional status or lower doses of steroids at 15 months. To my view, this finding points to the limited immunosuppressive efficacy of azathioprine.”

He added that the study findings should not be extrapolated to patients with mild presentations or to those with muscle-specific kinase myasthenia gravis.

Dr. Sharshar disclosed no relevant financial relationships. Disclosures for the study coauthors appear in the original article.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM JAMA NEUROLOGY

CAR T-cell products shine in real-world setting, reveal new insights

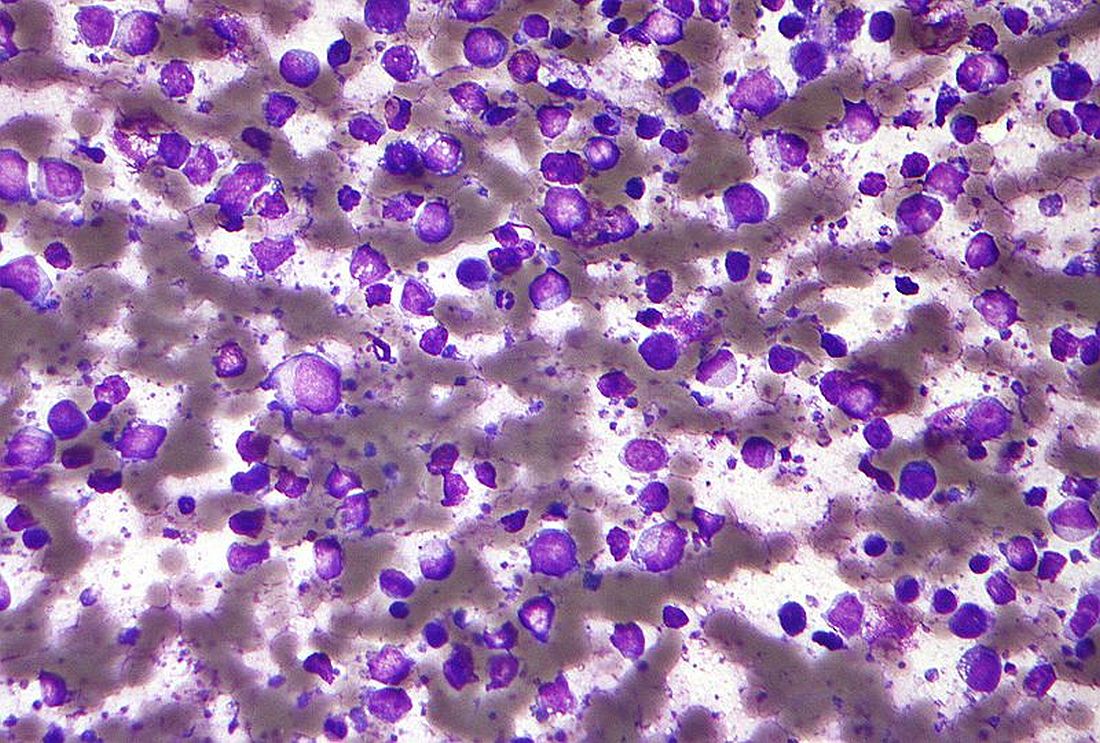

Real-world experience with chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cell therapies for large B-cell lymphomas compares favorably with experience in commercial and trial settings and provides new insights for predicting outcomes, according to Paolo Corradini, MD.

The 12-month duration of response (DOR) and progression-free survival (PFS) rates in 152 real-world patients treated with tisagenlecleucel (tisa-cel; Kymriah) for an approved indication were 48.4% and 26.4%, respectively, data reported to the Center for International Blood and Marrow Transplant Research (CIBMTR) and published in November 2020 in Blood Advances showed.

who relapsed or were refractory to at least two prior lines of therapy, Dr. Corradini said at the third European CAR T-cell Meeting, jointly sponsored by the European Society for Blood and Marrow Transplantation and the European Hematology Association.

A clinical update of the JULIET trial, as presented by Dr. Corradini and colleagues in a poster at the 2020 annual conference of the American Society of Hematology, showed a relapse-free probability of 60.4% at 24 and 30 months among 61 patients with an initial response.

The 12- and 36-month PFS rates as of February 2020, with median follow-up of 40.3 months, were 33% and 31%, respectively, and no new safety signals were identified, said Dr. Corradini, chair of hematology at the University of Milan.

Similarly, real-world data from the U.S. Lymphoma CAR T Consortium showing median PFS of 8.3 months at median follow-up of 12.9 months in 275 patients treated with axicabtagene ciloleucel (axi-cel; YESCARTA) were comparable with outcomes in the ZUMA-1 registrational trial, he noted.

An ongoing response was seen at 2 years in 39% of patients in ZUMA-1, and 3-year survival was 47%, according to an update reported at ASH 2019.

Of note, 43% of patients in the real-world study, which was published in the Journal of Clinical Oncology in September 2020, would not have met ZUMA-1 eligibility criteria because of comorbidities at the time of leukapheresis.

Predicting outcomes

The real-world data also demonstrated that performance status and lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) levels can predict outcomes: Patients with poor Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status of 2-4 versus less than 2, and elevated LDH had shorter PFS and overall survival (OS) on both univariate and multivariate analysis, Dr. Corradini noted.

A subsequent multicenter study showed similar response rates of 70% and 68% in ZUMA-1-eligible and noneligible patients, but significantly improved DOR, PFS, and OS outcomes among the ZUMA-1-eligible patients.

The authors also looked for “clinical predictive factors or some easy clinical biomarkers to predict the outcomes in our patients receiving CAR T-cells,” and found that C-reactive protein levels of more than 30 mg at infusion were associated with poorer DOR, PFS, and OS, he said.

In 60 patients in another U.S. study of both tisa-cel- and axi-cel-treated patients at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, 1-year event-free survival and OS were 40% and 69%, and Dr. Corradini’s experience with 55 patients at the University of Milan similarly showed 1-year PFS and OS of 40% and 70%, respectively.

“So all these studies support the notion that the results of CAR T-cells in real-world practice are durable for our patients, and are very similar to results obtained in the studies,” he said.

Other factors that have been shown to be associated with poor outcomes after CAR T-cell therapy include systemic bridging therapy, high metabolic tumor volume, and extranodal involvement; patients with these characteristics, along with those who have poor ECOG performance status or elevated LDH or CRP levels, do not comprise “a group to exclude from CAR T-cell therapy, but rather ... a group for whom there is an unmet need with our currently available treatments,” he said, adding: “So, it’s a group for which we have to do clinical trials and studies to improve the outcomes of our patient with large B-cell lymphomas.”

“These are all real-world data with commercially available products, he noted.

Product selection

Tisa-cel received Food and Drug Administration approval in 2017 and is used to treat relapsed or refractory acute lymphoblastic leukemia in those aged up to 25 years, and non-Hodgkin lymphoma that has relapsed or is refractory after at least two prior lines of therapy.

Axi-cel was also approved in 2017 for relapsed/refractory non-Hodgkin lymphoma, and in February 2021, after Dr. Corradini’s meeting presentation, the FDA granted a third approval to lisocabtagene maraleucel (liso-cel; Breyanzi) for this indication.

The information to date from both the trial and real-world settings are limited with respect to showing any differences in outcomes between the CAR T-cell products, but provide “an initial suggestion” that outcomes with tisa-cel and axi-cel are comparable, he said, adding that decisions should be strictly based on product registration data given the absence of reliable data for choosing one product over another.

Dr. Corradini reported honoraria and/or payment for travel and accommodations from Abbvie, Amgen, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Celgene, Daiichi Sankyo, and a number of other pharmaceutical companies.

Real-world experience with chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cell therapies for large B-cell lymphomas compares favorably with experience in commercial and trial settings and provides new insights for predicting outcomes, according to Paolo Corradini, MD.

The 12-month duration of response (DOR) and progression-free survival (PFS) rates in 152 real-world patients treated with tisagenlecleucel (tisa-cel; Kymriah) for an approved indication were 48.4% and 26.4%, respectively, data reported to the Center for International Blood and Marrow Transplant Research (CIBMTR) and published in November 2020 in Blood Advances showed.

who relapsed or were refractory to at least two prior lines of therapy, Dr. Corradini said at the third European CAR T-cell Meeting, jointly sponsored by the European Society for Blood and Marrow Transplantation and the European Hematology Association.

A clinical update of the JULIET trial, as presented by Dr. Corradini and colleagues in a poster at the 2020 annual conference of the American Society of Hematology, showed a relapse-free probability of 60.4% at 24 and 30 months among 61 patients with an initial response.

The 12- and 36-month PFS rates as of February 2020, with median follow-up of 40.3 months, were 33% and 31%, respectively, and no new safety signals were identified, said Dr. Corradini, chair of hematology at the University of Milan.

Similarly, real-world data from the U.S. Lymphoma CAR T Consortium showing median PFS of 8.3 months at median follow-up of 12.9 months in 275 patients treated with axicabtagene ciloleucel (axi-cel; YESCARTA) were comparable with outcomes in the ZUMA-1 registrational trial, he noted.

An ongoing response was seen at 2 years in 39% of patients in ZUMA-1, and 3-year survival was 47%, according to an update reported at ASH 2019.

Of note, 43% of patients in the real-world study, which was published in the Journal of Clinical Oncology in September 2020, would not have met ZUMA-1 eligibility criteria because of comorbidities at the time of leukapheresis.

Predicting outcomes

The real-world data also demonstrated that performance status and lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) levels can predict outcomes: Patients with poor Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status of 2-4 versus less than 2, and elevated LDH had shorter PFS and overall survival (OS) on both univariate and multivariate analysis, Dr. Corradini noted.

A subsequent multicenter study showed similar response rates of 70% and 68% in ZUMA-1-eligible and noneligible patients, but significantly improved DOR, PFS, and OS outcomes among the ZUMA-1-eligible patients.

The authors also looked for “clinical predictive factors or some easy clinical biomarkers to predict the outcomes in our patients receiving CAR T-cells,” and found that C-reactive protein levels of more than 30 mg at infusion were associated with poorer DOR, PFS, and OS, he said.

In 60 patients in another U.S. study of both tisa-cel- and axi-cel-treated patients at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, 1-year event-free survival and OS were 40% and 69%, and Dr. Corradini’s experience with 55 patients at the University of Milan similarly showed 1-year PFS and OS of 40% and 70%, respectively.

“So all these studies support the notion that the results of CAR T-cells in real-world practice are durable for our patients, and are very similar to results obtained in the studies,” he said.

Other factors that have been shown to be associated with poor outcomes after CAR T-cell therapy include systemic bridging therapy, high metabolic tumor volume, and extranodal involvement; patients with these characteristics, along with those who have poor ECOG performance status or elevated LDH or CRP levels, do not comprise “a group to exclude from CAR T-cell therapy, but rather ... a group for whom there is an unmet need with our currently available treatments,” he said, adding: “So, it’s a group for which we have to do clinical trials and studies to improve the outcomes of our patient with large B-cell lymphomas.”

“These are all real-world data with commercially available products, he noted.

Product selection

Tisa-cel received Food and Drug Administration approval in 2017 and is used to treat relapsed or refractory acute lymphoblastic leukemia in those aged up to 25 years, and non-Hodgkin lymphoma that has relapsed or is refractory after at least two prior lines of therapy.

Axi-cel was also approved in 2017 for relapsed/refractory non-Hodgkin lymphoma, and in February 2021, after Dr. Corradini’s meeting presentation, the FDA granted a third approval to lisocabtagene maraleucel (liso-cel; Breyanzi) for this indication.

The information to date from both the trial and real-world settings are limited with respect to showing any differences in outcomes between the CAR T-cell products, but provide “an initial suggestion” that outcomes with tisa-cel and axi-cel are comparable, he said, adding that decisions should be strictly based on product registration data given the absence of reliable data for choosing one product over another.

Dr. Corradini reported honoraria and/or payment for travel and accommodations from Abbvie, Amgen, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Celgene, Daiichi Sankyo, and a number of other pharmaceutical companies.

Real-world experience with chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cell therapies for large B-cell lymphomas compares favorably with experience in commercial and trial settings and provides new insights for predicting outcomes, according to Paolo Corradini, MD.

The 12-month duration of response (DOR) and progression-free survival (PFS) rates in 152 real-world patients treated with tisagenlecleucel (tisa-cel; Kymriah) for an approved indication were 48.4% and 26.4%, respectively, data reported to the Center for International Blood and Marrow Transplant Research (CIBMTR) and published in November 2020 in Blood Advances showed.

who relapsed or were refractory to at least two prior lines of therapy, Dr. Corradini said at the third European CAR T-cell Meeting, jointly sponsored by the European Society for Blood and Marrow Transplantation and the European Hematology Association.

A clinical update of the JULIET trial, as presented by Dr. Corradini and colleagues in a poster at the 2020 annual conference of the American Society of Hematology, showed a relapse-free probability of 60.4% at 24 and 30 months among 61 patients with an initial response.

The 12- and 36-month PFS rates as of February 2020, with median follow-up of 40.3 months, were 33% and 31%, respectively, and no new safety signals were identified, said Dr. Corradini, chair of hematology at the University of Milan.

Similarly, real-world data from the U.S. Lymphoma CAR T Consortium showing median PFS of 8.3 months at median follow-up of 12.9 months in 275 patients treated with axicabtagene ciloleucel (axi-cel; YESCARTA) were comparable with outcomes in the ZUMA-1 registrational trial, he noted.

An ongoing response was seen at 2 years in 39% of patients in ZUMA-1, and 3-year survival was 47%, according to an update reported at ASH 2019.

Of note, 43% of patients in the real-world study, which was published in the Journal of Clinical Oncology in September 2020, would not have met ZUMA-1 eligibility criteria because of comorbidities at the time of leukapheresis.

Predicting outcomes

The real-world data also demonstrated that performance status and lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) levels can predict outcomes: Patients with poor Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status of 2-4 versus less than 2, and elevated LDH had shorter PFS and overall survival (OS) on both univariate and multivariate analysis, Dr. Corradini noted.

A subsequent multicenter study showed similar response rates of 70% and 68% in ZUMA-1-eligible and noneligible patients, but significantly improved DOR, PFS, and OS outcomes among the ZUMA-1-eligible patients.

The authors also looked for “clinical predictive factors or some easy clinical biomarkers to predict the outcomes in our patients receiving CAR T-cells,” and found that C-reactive protein levels of more than 30 mg at infusion were associated with poorer DOR, PFS, and OS, he said.

In 60 patients in another U.S. study of both tisa-cel- and axi-cel-treated patients at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, 1-year event-free survival and OS were 40% and 69%, and Dr. Corradini’s experience with 55 patients at the University of Milan similarly showed 1-year PFS and OS of 40% and 70%, respectively.

“So all these studies support the notion that the results of CAR T-cells in real-world practice are durable for our patients, and are very similar to results obtained in the studies,” he said.

Other factors that have been shown to be associated with poor outcomes after CAR T-cell therapy include systemic bridging therapy, high metabolic tumor volume, and extranodal involvement; patients with these characteristics, along with those who have poor ECOG performance status or elevated LDH or CRP levels, do not comprise “a group to exclude from CAR T-cell therapy, but rather ... a group for whom there is an unmet need with our currently available treatments,” he said, adding: “So, it’s a group for which we have to do clinical trials and studies to improve the outcomes of our patient with large B-cell lymphomas.”

“These are all real-world data with commercially available products, he noted.

Product selection

Tisa-cel received Food and Drug Administration approval in 2017 and is used to treat relapsed or refractory acute lymphoblastic leukemia in those aged up to 25 years, and non-Hodgkin lymphoma that has relapsed or is refractory after at least two prior lines of therapy.

Axi-cel was also approved in 2017 for relapsed/refractory non-Hodgkin lymphoma, and in February 2021, after Dr. Corradini’s meeting presentation, the FDA granted a third approval to lisocabtagene maraleucel (liso-cel; Breyanzi) for this indication.

The information to date from both the trial and real-world settings are limited with respect to showing any differences in outcomes between the CAR T-cell products, but provide “an initial suggestion” that outcomes with tisa-cel and axi-cel are comparable, he said, adding that decisions should be strictly based on product registration data given the absence of reliable data for choosing one product over another.

Dr. Corradini reported honoraria and/or payment for travel and accommodations from Abbvie, Amgen, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Celgene, Daiichi Sankyo, and a number of other pharmaceutical companies.

FROM CART21

Alien cells may explain COVID-19 brain fog

, a new report suggests.

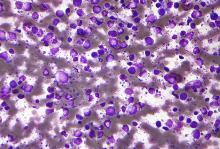

The authors report five separate post-mortem cases from patients who died with COVID-19 in which large cells resembling megakaryocytes were identified in cortical capillaries. Immunohistochemistry subsequently confirmed their megakaryocyte identity.

They point out that the finding is of interest as – to their knowledge – megakaryocytes have not been found in the brain before.

The observations are described in a research letter published online Feb. 12 in JAMA Neurology.

Bone marrow cells in the brain

Lead author David Nauen, MD, PhD, a neuropathologist from Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, reported that he identified these cells in the first analysis of post-mortem brain tissue from a patient who had COVID-19.

“Some other viruses cause changes in the brain such as encephalopathy, and as neurologic symptoms are often reported in COVID-19, I was curious to see if similar effects were seen in brain post-mortem samples from patients who had died with the infection,” Dr. Nauen said.

On his first analysis of the brain tissue of a patient who had COVID-19, Dr. Nauen saw no evidence of viral encephalitis, but he observed some “unusually large” cells in the brain capillaries.

“I was taken aback; I couldn’t figure out what they were. Then I realized these cells were megakaryocytes from the bone marrow. I have never seen these cells in the brain before. I asked several colleagues and none of them had either. After extensive literature searches, I could find no evidence of megakaryocytes being in the brain,” Dr. Nauen noted.

Megakaryocytes, he explained, are “very large cells, and the brain capillaries are very small – just large enough to let red blood cells and lymphocytes pass through. To see these very large cells in such vessels is extremely unusual. It looks like they are causing occlusions.”

By occluding flow through individual capillaries, these large cells could cause ischemic alteration in a distinct pattern, potentially resulting in an atypical form of neurologic impairment, the authors suggest.

“This might alter the hemodynamics and put pressure on other vessels, possibly contributing to the increased risk of stroke that has been reported in COVID-19,” Dr. Nauen said. None of the samples he examined came from patients with COVID-19 who had had a stroke, he reported.

Other than the presence of megakaryocytes in the capillaries, the brain looked normal, he said. He has now examined samples from 15 brains of patients who had COVID-19 and megakaryocytes have been found in the brain capillaries in five cases.

New neurologic complication

Classic encephalitis found with other viruses has not been reported in brain post-mortem examinations from patients who had COVID-19, Dr. Nauen noted. “The cognitive issues such as grogginess associated with COVID-19 would indicate problems with the cortex but that hasn’t been documented. This occlusion of a multitude of tiny vessels by megalokaryocytes may offer some explanation of the cognitive issues. This is a new kind of vascular insult seen on pathology, and suggests a new kind of neurologic complication,” he added.

The big question is what these megakaryocytes are doing in the brain.

“Megakaryocytes are bone marrow cells. They are not immune cells. Their job is to produce platelets to help the blood clot. They are not normally found outside the bone marrow, but they have been reported in other organs in COVID-19 patients.

“But the big puzzle associated with finding them in the brain is how they get through the very fine network of blood vessels in the lungs. The geometry just doesn’t work. We don’t know which part of the COVID inflammatory response makes this happen,” said Dr. Nauen.

The authors suggest one possibility is that altered endothelial or other signaling is recruiting megakaryocytes into the circulation and somehow permitting them to pass through the lungs.

“We need to try and understand if there is anything distinctive about these megakaryocytes – which proteins are they expressing that may explain why they are behaving in such an unusual way,” said Dr. Nauen.

Noting that many patients with severe COVID-19 have problems with clotting, and megakaryocytes are part of the clotting system, he speculated that some sort of aberrant message is being sent to these cells.

“It is notable that we found megakaryocytes in cortical capillaries in 33% of cases examined. Because the standard brain autopsy sections taken sampled at random [are] only a minute portion of the cortical volume, finding these cells suggests the total burden could be considerable,” the authors wrote.

Dr. Nauen added that to his knowledge, this is the first report of such observations, and the next step is to look for similar findings in larger sample sizes.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

, a new report suggests.

The authors report five separate post-mortem cases from patients who died with COVID-19 in which large cells resembling megakaryocytes were identified in cortical capillaries. Immunohistochemistry subsequently confirmed their megakaryocyte identity.

They point out that the finding is of interest as – to their knowledge – megakaryocytes have not been found in the brain before.

The observations are described in a research letter published online Feb. 12 in JAMA Neurology.

Bone marrow cells in the brain

Lead author David Nauen, MD, PhD, a neuropathologist from Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, reported that he identified these cells in the first analysis of post-mortem brain tissue from a patient who had COVID-19.

“Some other viruses cause changes in the brain such as encephalopathy, and as neurologic symptoms are often reported in COVID-19, I was curious to see if similar effects were seen in brain post-mortem samples from patients who had died with the infection,” Dr. Nauen said.

On his first analysis of the brain tissue of a patient who had COVID-19, Dr. Nauen saw no evidence of viral encephalitis, but he observed some “unusually large” cells in the brain capillaries.

“I was taken aback; I couldn’t figure out what they were. Then I realized these cells were megakaryocytes from the bone marrow. I have never seen these cells in the brain before. I asked several colleagues and none of them had either. After extensive literature searches, I could find no evidence of megakaryocytes being in the brain,” Dr. Nauen noted.

Megakaryocytes, he explained, are “very large cells, and the brain capillaries are very small – just large enough to let red blood cells and lymphocytes pass through. To see these very large cells in such vessels is extremely unusual. It looks like they are causing occlusions.”

By occluding flow through individual capillaries, these large cells could cause ischemic alteration in a distinct pattern, potentially resulting in an atypical form of neurologic impairment, the authors suggest.

“This might alter the hemodynamics and put pressure on other vessels, possibly contributing to the increased risk of stroke that has been reported in COVID-19,” Dr. Nauen said. None of the samples he examined came from patients with COVID-19 who had had a stroke, he reported.

Other than the presence of megakaryocytes in the capillaries, the brain looked normal, he said. He has now examined samples from 15 brains of patients who had COVID-19 and megakaryocytes have been found in the brain capillaries in five cases.

New neurologic complication

Classic encephalitis found with other viruses has not been reported in brain post-mortem examinations from patients who had COVID-19, Dr. Nauen noted. “The cognitive issues such as grogginess associated with COVID-19 would indicate problems with the cortex but that hasn’t been documented. This occlusion of a multitude of tiny vessels by megalokaryocytes may offer some explanation of the cognitive issues. This is a new kind of vascular insult seen on pathology, and suggests a new kind of neurologic complication,” he added.

The big question is what these megakaryocytes are doing in the brain.

“Megakaryocytes are bone marrow cells. They are not immune cells. Their job is to produce platelets to help the blood clot. They are not normally found outside the bone marrow, but they have been reported in other organs in COVID-19 patients.

“But the big puzzle associated with finding them in the brain is how they get through the very fine network of blood vessels in the lungs. The geometry just doesn’t work. We don’t know which part of the COVID inflammatory response makes this happen,” said Dr. Nauen.

The authors suggest one possibility is that altered endothelial or other signaling is recruiting megakaryocytes into the circulation and somehow permitting them to pass through the lungs.

“We need to try and understand if there is anything distinctive about these megakaryocytes – which proteins are they expressing that may explain why they are behaving in such an unusual way,” said Dr. Nauen.

Noting that many patients with severe COVID-19 have problems with clotting, and megakaryocytes are part of the clotting system, he speculated that some sort of aberrant message is being sent to these cells.

“It is notable that we found megakaryocytes in cortical capillaries in 33% of cases examined. Because the standard brain autopsy sections taken sampled at random [are] only a minute portion of the cortical volume, finding these cells suggests the total burden could be considerable,” the authors wrote.

Dr. Nauen added that to his knowledge, this is the first report of such observations, and the next step is to look for similar findings in larger sample sizes.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

, a new report suggests.

The authors report five separate post-mortem cases from patients who died with COVID-19 in which large cells resembling megakaryocytes were identified in cortical capillaries. Immunohistochemistry subsequently confirmed their megakaryocyte identity.

They point out that the finding is of interest as – to their knowledge – megakaryocytes have not been found in the brain before.

The observations are described in a research letter published online Feb. 12 in JAMA Neurology.

Bone marrow cells in the brain

Lead author David Nauen, MD, PhD, a neuropathologist from Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, reported that he identified these cells in the first analysis of post-mortem brain tissue from a patient who had COVID-19.

“Some other viruses cause changes in the brain such as encephalopathy, and as neurologic symptoms are often reported in COVID-19, I was curious to see if similar effects were seen in brain post-mortem samples from patients who had died with the infection,” Dr. Nauen said.

On his first analysis of the brain tissue of a patient who had COVID-19, Dr. Nauen saw no evidence of viral encephalitis, but he observed some “unusually large” cells in the brain capillaries.

“I was taken aback; I couldn’t figure out what they were. Then I realized these cells were megakaryocytes from the bone marrow. I have never seen these cells in the brain before. I asked several colleagues and none of them had either. After extensive literature searches, I could find no evidence of megakaryocytes being in the brain,” Dr. Nauen noted.

Megakaryocytes, he explained, are “very large cells, and the brain capillaries are very small – just large enough to let red blood cells and lymphocytes pass through. To see these very large cells in such vessels is extremely unusual. It looks like they are causing occlusions.”

By occluding flow through individual capillaries, these large cells could cause ischemic alteration in a distinct pattern, potentially resulting in an atypical form of neurologic impairment, the authors suggest.

“This might alter the hemodynamics and put pressure on other vessels, possibly contributing to the increased risk of stroke that has been reported in COVID-19,” Dr. Nauen said. None of the samples he examined came from patients with COVID-19 who had had a stroke, he reported.

Other than the presence of megakaryocytes in the capillaries, the brain looked normal, he said. He has now examined samples from 15 brains of patients who had COVID-19 and megakaryocytes have been found in the brain capillaries in five cases.

New neurologic complication

Classic encephalitis found with other viruses has not been reported in brain post-mortem examinations from patients who had COVID-19, Dr. Nauen noted. “The cognitive issues such as grogginess associated with COVID-19 would indicate problems with the cortex but that hasn’t been documented. This occlusion of a multitude of tiny vessels by megalokaryocytes may offer some explanation of the cognitive issues. This is a new kind of vascular insult seen on pathology, and suggests a new kind of neurologic complication,” he added.

The big question is what these megakaryocytes are doing in the brain.

“Megakaryocytes are bone marrow cells. They are not immune cells. Their job is to produce platelets to help the blood clot. They are not normally found outside the bone marrow, but they have been reported in other organs in COVID-19 patients.

“But the big puzzle associated with finding them in the brain is how they get through the very fine network of blood vessels in the lungs. The geometry just doesn’t work. We don’t know which part of the COVID inflammatory response makes this happen,” said Dr. Nauen.

The authors suggest one possibility is that altered endothelial or other signaling is recruiting megakaryocytes into the circulation and somehow permitting them to pass through the lungs.

“We need to try and understand if there is anything distinctive about these megakaryocytes – which proteins are they expressing that may explain why they are behaving in such an unusual way,” said Dr. Nauen.

Noting that many patients with severe COVID-19 have problems with clotting, and megakaryocytes are part of the clotting system, he speculated that some sort of aberrant message is being sent to these cells.

“It is notable that we found megakaryocytes in cortical capillaries in 33% of cases examined. Because the standard brain autopsy sections taken sampled at random [are] only a minute portion of the cortical volume, finding these cells suggests the total burden could be considerable,” the authors wrote.

Dr. Nauen added that to his knowledge, this is the first report of such observations, and the next step is to look for similar findings in larger sample sizes.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM JAMA NEUROLOGY

Chronic GVHD therapies offer hope for treating refractory disease

Despite improvements in prevention of graft-versus-host disease, chronic GVHD still occurs in 10%-50% of patients who undergo an allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplant, and these patients may require prolonged treatment with multiple lines of therapy, said a hematologist and transplant researcher.

“More effective, less toxic therapies for chronic GVHD are needed,” Stephanie Lee, MD, MPH, from the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center in Seattle said at the Transplant & Cellular Therapies Meetings.

Dr. Lee reviewed clinical trials for chronic GVHD at the meeting held by the American Society for Blood and Marrow Transplantation and the Center for International Blood and Marrow Transplant Research.

Although the incidence of chronic GVHD has gradually declined over the last 40 years and both relapse-free and overall survival following a chronic GVHD diagnosis have improved, “for patients who are diagnosed with chronic GVHD, they still will see many lines of therapy and many years of therapy,” she said.

Among 148 patients with chronic GVHD treated at her center, for example, 66% went on to two lines of therapy, 50% went on to three lines, 37% required four lines of therapy, and 20% needed five lines or more.

Salvage therapies for patients with chronic GVHD have evolved away from immunomodulators and immunosuppressants in the early 1990s, toward monoclonal antibodies such as rituximab in the early 2000s, to interleukin-2 and to tyrosine kinase inhibitors such as ruxolitinib (Jakafi) and ibrutinib (Imbruvica).

There are currently 36 agents that are FDA approved for at least one indication and can also be prescribed for the treatment of chronic GVHD, Dr. Lee noted.

Treatment goals

Dr. Lee laid out six goals for treating patients with chronic GVHD. They include:

- Controlling current signs and symptoms, measured by response rates and patient-reported outcomes

- Preventing further tissue and organ damage

- Minimizing toxicity

- Maintaining graft-versus-tumor effect

- Achieving graft tolerance and stopping immunosuppression

- Decreasing nonrelapse mortality and improving survival

Active trials

Dr. Lee identified 33 trials with chronic GVHD as an indication that are currently recruiting, and an additional 13 trials that are active but closed to recruiting. The trials can be generally grouped by mechanism of action, and involve agents targeting T-regulatory cells, B cells and/or B-cell receptor (BCR) signaling, monocytes/macrophages, costimulatory blockage, a proteasome inhibition, Janus kinase (JAK) 1/2 inhibitors, ROCK2 inhibitors, hedgehog pathway inhibition, cellular therapy, and organ-targeted therapy.

Most of the trials have overall response rate as the primary endpoint, and all but five are currently in phase 1 or 2. The currently active phase 3 trials include two with ibrutinib, one with the investigational agent itacitinib, one with ruxolitinib, and one with mesenchymal stem cells.

“I’ll note that, when results are reported, the denominator really matters for the overall response rate, especially if you’re talking about small trials, because if you require the patient to be treated with an agent for a certain period of time, and you take out all the people who didn’t make it to that time point, then your overall response rate looks better,” she said.

BTK inhibitors

The first-in-class Bruton tyrosine kinase (BTK) inhibitor ibrutinib was the first and thus far only agent approved by the Food and Drug Administration for chronic GVHD. The approval was based on a single-arm, multicenter trial with 42 patients.

The ORR in this trial was 69%, consisting of 31% complete responses and 38% partial responses, with a duration of response longer than 10 months in slightly more than half of all patients. In all, 24% of patients had improvement of symptoms in two consecutive visits, and 29% continued on ibrutinib at the time of the primary analysis in 2017.

Based on these promising results, acalabrutinib, which is more potent and selective for BTK than ibrutinib, with no effect on either platelets or natural killer cells, is currently under investigation in a phase 2 trial in 50 patients at a dose of 100 mg orally twice daily.

JAK1/2 inhibition

The JAK1 inhibitor itacitinib failed to meet its primary ORR endpoint in the phase 3 GRAVITAS-301 study, according to a press release, but the manufacturer (Incyte) said that it is continuing its commitment to JAK inhibitors with ruxolitinib, which has shown activity against acute, steroid-refractory GVHD, and is being explored for prevention of chronic GVHD in the randomized, phase 3 REACH3 study.

The trial met its primary endpoint for a higher ORR at week 24 with ruxolitinib versus best available therapy, at 49.7% versus 25.6%, respectively, which translated into an odds ratio for response with the JAK inhibitor of 2.99 (P < .0001).

Selective T-cell expansion

Efavaleukin alfa is an IL-2-mutated protein (mutein), with a mutation in the IL-2RB-binding portion of IL-2 causing increased selectivity for regulatory T-cell expansion. It is bound to an IgG-Fc domain that is itself mutated, with reduced Fc receptor binding and IgG effector function to give it a longer half life. This agent is being studied in a phase 1/2 trial in a subcutaneous formulation delivered every 1 or 2 weeks to 68 patients.

Monocyte/macrophage depletion

Axatilimab is a high-affinity antibody targeting colony stimulating factor–1 receptor (CSF-1R) expressed on monocytes and macrophages. By blocking CSF-1R, it depletes circulation of nonclassical monocytes and prevents the differentiation and survival of M2 macrophages in tissue.

It is currently being investigated 30 patients in a phase 1/2 study in an intravenous formulation delivered over 30 minutes every 2-4 weeks.

Hedgehog pathway inhibition

There is evidence suggesting that hedgehog pathway inhibition can lessen fibrosis. Glasdegib (Daurismo) a potent selective oral inhibitor of the hedgehog signaling pathway, is approved for use with low-dose cytarabine for patients with newly diagnosed acute myeloid leukemia aged older than 75 years or have comorbidities precluding intensive chemotherapy.

This agent is associated with drug intolerance because of muscle spasms, dysgeusia, and alopecia, however.

The drug is currently in phase 1/2 at a dose of 50 mg orally per day in 20 patients.

ROCK2 inhibition

Belumosudil (formerly KD025) “appears to rebalance the immune system,” Dr. Lee said. Investigators think that the drug dampens an autoaggressive inflammatory response by selective inhibition of ROCK2.

This drug has been studied in a dose-escalation study and a phase 2 trial, in which 132 participants were randomized to receive belumosudil 200 mg either once or twice daily.

At a median follow-up of 8 months, the ORR with belumosudil 200 mg once and twice daily was 73% and 74%, respectively. Similar results were seen in patients who had previously received either ruxolitinib or ibrutinib. High response rates were seen in patients with severe chronic GVHD, involvement of four or more organs and a refractory response to their last line of therapy.

Hard-to-manage patients

“We’re very hopeful for many of these agents, but we have to acknowledge that there are still many management dilemmas, patients that we just don’t really know what to do with,” Dr. Lee said. “These include patients who have bad sclerosis and fasciitis, nonhealing skin ulcers, bronchiolitis obliterans, serositis that can be very difficult to manage, severe keratoconjunctivitis that can be eyesight threatening, nonhealing mouth ulcers, esophageal structures, and always patients who have frequent infections.

“We are hopeful that some these agents will be useful for our patients who have severe manifestations, but often the number of patients with these manifestations in the trials is too low to say something specific about them,” she added.

‘Exciting time’

“It’s an exciting time because there are a lot of different drugs that are being studied for chronic GVHD,” commented Betty Hamilton, MD, a hematologist/oncologist at the Cleveland Clinic.

“I think that where the field is going in terms of treatment is recognizing that chronic GVHD is a pretty heterogeneous disease, and we have to learn even more about the underlying biologic pathways to be able to determine which class of drugs to use and when,” she said in an interview.

She agreed with Dr. Lee that the goals of treating patients with chronic GVHD include improving symptoms and quality, preventing progression, ideally tapering patients off immunosuppression, and achieving a balance between preventing negative consequences of GVHD while maintain the benefits of a graft-versus-leukemia effect.

“In our center, drug choice is based on physician preference and comfort with how often they’ve used the drug, patients’ comorbidities, toxicities of the drug, and logistical considerations,” Dr. Hamilton said.

Dr. Lee disclosed consulting activities for Pfizer and Kadmon, travel and lodging from Amgen, and research funding from those companies and others. Dr. Hamilton disclosed consulting for Syndax and Incyte.

Despite improvements in prevention of graft-versus-host disease, chronic GVHD still occurs in 10%-50% of patients who undergo an allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplant, and these patients may require prolonged treatment with multiple lines of therapy, said a hematologist and transplant researcher.

“More effective, less toxic therapies for chronic GVHD are needed,” Stephanie Lee, MD, MPH, from the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center in Seattle said at the Transplant & Cellular Therapies Meetings.

Dr. Lee reviewed clinical trials for chronic GVHD at the meeting held by the American Society for Blood and Marrow Transplantation and the Center for International Blood and Marrow Transplant Research.

Although the incidence of chronic GVHD has gradually declined over the last 40 years and both relapse-free and overall survival following a chronic GVHD diagnosis have improved, “for patients who are diagnosed with chronic GVHD, they still will see many lines of therapy and many years of therapy,” she said.

Among 148 patients with chronic GVHD treated at her center, for example, 66% went on to two lines of therapy, 50% went on to three lines, 37% required four lines of therapy, and 20% needed five lines or more.

Salvage therapies for patients with chronic GVHD have evolved away from immunomodulators and immunosuppressants in the early 1990s, toward monoclonal antibodies such as rituximab in the early 2000s, to interleukin-2 and to tyrosine kinase inhibitors such as ruxolitinib (Jakafi) and ibrutinib (Imbruvica).

There are currently 36 agents that are FDA approved for at least one indication and can also be prescribed for the treatment of chronic GVHD, Dr. Lee noted.

Treatment goals

Dr. Lee laid out six goals for treating patients with chronic GVHD. They include:

- Controlling current signs and symptoms, measured by response rates and patient-reported outcomes

- Preventing further tissue and organ damage

- Minimizing toxicity

- Maintaining graft-versus-tumor effect

- Achieving graft tolerance and stopping immunosuppression

- Decreasing nonrelapse mortality and improving survival

Active trials

Dr. Lee identified 33 trials with chronic GVHD as an indication that are currently recruiting, and an additional 13 trials that are active but closed to recruiting. The trials can be generally grouped by mechanism of action, and involve agents targeting T-regulatory cells, B cells and/or B-cell receptor (BCR) signaling, monocytes/macrophages, costimulatory blockage, a proteasome inhibition, Janus kinase (JAK) 1/2 inhibitors, ROCK2 inhibitors, hedgehog pathway inhibition, cellular therapy, and organ-targeted therapy.

Most of the trials have overall response rate as the primary endpoint, and all but five are currently in phase 1 or 2. The currently active phase 3 trials include two with ibrutinib, one with the investigational agent itacitinib, one with ruxolitinib, and one with mesenchymal stem cells.

“I’ll note that, when results are reported, the denominator really matters for the overall response rate, especially if you’re talking about small trials, because if you require the patient to be treated with an agent for a certain period of time, and you take out all the people who didn’t make it to that time point, then your overall response rate looks better,” she said.

BTK inhibitors

The first-in-class Bruton tyrosine kinase (BTK) inhibitor ibrutinib was the first and thus far only agent approved by the Food and Drug Administration for chronic GVHD. The approval was based on a single-arm, multicenter trial with 42 patients.

The ORR in this trial was 69%, consisting of 31% complete responses and 38% partial responses, with a duration of response longer than 10 months in slightly more than half of all patients. In all, 24% of patients had improvement of symptoms in two consecutive visits, and 29% continued on ibrutinib at the time of the primary analysis in 2017.

Based on these promising results, acalabrutinib, which is more potent and selective for BTK than ibrutinib, with no effect on either platelets or natural killer cells, is currently under investigation in a phase 2 trial in 50 patients at a dose of 100 mg orally twice daily.

JAK1/2 inhibition

The JAK1 inhibitor itacitinib failed to meet its primary ORR endpoint in the phase 3 GRAVITAS-301 study, according to a press release, but the manufacturer (Incyte) said that it is continuing its commitment to JAK inhibitors with ruxolitinib, which has shown activity against acute, steroid-refractory GVHD, and is being explored for prevention of chronic GVHD in the randomized, phase 3 REACH3 study.

The trial met its primary endpoint for a higher ORR at week 24 with ruxolitinib versus best available therapy, at 49.7% versus 25.6%, respectively, which translated into an odds ratio for response with the JAK inhibitor of 2.99 (P < .0001).

Selective T-cell expansion

Efavaleukin alfa is an IL-2-mutated protein (mutein), with a mutation in the IL-2RB-binding portion of IL-2 causing increased selectivity for regulatory T-cell expansion. It is bound to an IgG-Fc domain that is itself mutated, with reduced Fc receptor binding and IgG effector function to give it a longer half life. This agent is being studied in a phase 1/2 trial in a subcutaneous formulation delivered every 1 or 2 weeks to 68 patients.

Monocyte/macrophage depletion

Axatilimab is a high-affinity antibody targeting colony stimulating factor–1 receptor (CSF-1R) expressed on monocytes and macrophages. By blocking CSF-1R, it depletes circulation of nonclassical monocytes and prevents the differentiation and survival of M2 macrophages in tissue.

It is currently being investigated 30 patients in a phase 1/2 study in an intravenous formulation delivered over 30 minutes every 2-4 weeks.

Hedgehog pathway inhibition

There is evidence suggesting that hedgehog pathway inhibition can lessen fibrosis. Glasdegib (Daurismo) a potent selective oral inhibitor of the hedgehog signaling pathway, is approved for use with low-dose cytarabine for patients with newly diagnosed acute myeloid leukemia aged older than 75 years or have comorbidities precluding intensive chemotherapy.

This agent is associated with drug intolerance because of muscle spasms, dysgeusia, and alopecia, however.

The drug is currently in phase 1/2 at a dose of 50 mg orally per day in 20 patients.

ROCK2 inhibition

Belumosudil (formerly KD025) “appears to rebalance the immune system,” Dr. Lee said. Investigators think that the drug dampens an autoaggressive inflammatory response by selective inhibition of ROCK2.

This drug has been studied in a dose-escalation study and a phase 2 trial, in which 132 participants were randomized to receive belumosudil 200 mg either once or twice daily.

At a median follow-up of 8 months, the ORR with belumosudil 200 mg once and twice daily was 73% and 74%, respectively. Similar results were seen in patients who had previously received either ruxolitinib or ibrutinib. High response rates were seen in patients with severe chronic GVHD, involvement of four or more organs and a refractory response to their last line of therapy.

Hard-to-manage patients

“We’re very hopeful for many of these agents, but we have to acknowledge that there are still many management dilemmas, patients that we just don’t really know what to do with,” Dr. Lee said. “These include patients who have bad sclerosis and fasciitis, nonhealing skin ulcers, bronchiolitis obliterans, serositis that can be very difficult to manage, severe keratoconjunctivitis that can be eyesight threatening, nonhealing mouth ulcers, esophageal structures, and always patients who have frequent infections.

“We are hopeful that some these agents will be useful for our patients who have severe manifestations, but often the number of patients with these manifestations in the trials is too low to say something specific about them,” she added.

‘Exciting time’

“It’s an exciting time because there are a lot of different drugs that are being studied for chronic GVHD,” commented Betty Hamilton, MD, a hematologist/oncologist at the Cleveland Clinic.

“I think that where the field is going in terms of treatment is recognizing that chronic GVHD is a pretty heterogeneous disease, and we have to learn even more about the underlying biologic pathways to be able to determine which class of drugs to use and when,” she said in an interview.

She agreed with Dr. Lee that the goals of treating patients with chronic GVHD include improving symptoms and quality, preventing progression, ideally tapering patients off immunosuppression, and achieving a balance between preventing negative consequences of GVHD while maintain the benefits of a graft-versus-leukemia effect.

“In our center, drug choice is based on physician preference and comfort with how often they’ve used the drug, patients’ comorbidities, toxicities of the drug, and logistical considerations,” Dr. Hamilton said.

Dr. Lee disclosed consulting activities for Pfizer and Kadmon, travel and lodging from Amgen, and research funding from those companies and others. Dr. Hamilton disclosed consulting for Syndax and Incyte.

Despite improvements in prevention of graft-versus-host disease, chronic GVHD still occurs in 10%-50% of patients who undergo an allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplant, and these patients may require prolonged treatment with multiple lines of therapy, said a hematologist and transplant researcher.

“More effective, less toxic therapies for chronic GVHD are needed,” Stephanie Lee, MD, MPH, from the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center in Seattle said at the Transplant & Cellular Therapies Meetings.

Dr. Lee reviewed clinical trials for chronic GVHD at the meeting held by the American Society for Blood and Marrow Transplantation and the Center for International Blood and Marrow Transplant Research.

Although the incidence of chronic GVHD has gradually declined over the last 40 years and both relapse-free and overall survival following a chronic GVHD diagnosis have improved, “for patients who are diagnosed with chronic GVHD, they still will see many lines of therapy and many years of therapy,” she said.

Among 148 patients with chronic GVHD treated at her center, for example, 66% went on to two lines of therapy, 50% went on to three lines, 37% required four lines of therapy, and 20% needed five lines or more.

Salvage therapies for patients with chronic GVHD have evolved away from immunomodulators and immunosuppressants in the early 1990s, toward monoclonal antibodies such as rituximab in the early 2000s, to interleukin-2 and to tyrosine kinase inhibitors such as ruxolitinib (Jakafi) and ibrutinib (Imbruvica).

There are currently 36 agents that are FDA approved for at least one indication and can also be prescribed for the treatment of chronic GVHD, Dr. Lee noted.

Treatment goals

Dr. Lee laid out six goals for treating patients with chronic GVHD. They include:

- Controlling current signs and symptoms, measured by response rates and patient-reported outcomes

- Preventing further tissue and organ damage

- Minimizing toxicity

- Maintaining graft-versus-tumor effect

- Achieving graft tolerance and stopping immunosuppression

- Decreasing nonrelapse mortality and improving survival

Active trials