User login

Trustworthy Recommendations: A Closer Look Inside the AGA’s Clinical Guideline Development Process

The AGA understands how important it is for busy physicians to have access to the most trustworthy, actionable, and evidence-based guidelines in order to achieve the highest possible quality of patient care. According to a 2016 survey, AGA members ranked guidelines as the most important of all AGA-specific benefits, giving guidelines an average of 4.61 out of 5 (where 5 was defined as “extremely important”). The AGA’s guidelines landing page (www.gastro.org/guidelines) has long been the most frequently accessed page on the AGA website.

The life cycle of an AGA guideline

In 2010, the AGA Institute officially adopted the GRADE (Grades of Recommendation Assessment, Development, and Evaluation) methodology for the development of all future guidelines. Since the publication of our first GRADE-based guideline in 2013, the AGA has developed and published 12 guidelines with an additional 11 more to be published by 2019. Based on the systematic rigor of the GRADE approach, the AGA’s guideline development process was created to result in clinical recommendations that are not only evidence based but actionable and responsive to varying patient needs and preferences at the point of care.

All told, a single AGA guideline costs around $45,000 and takes approximately 24 months to complete and publish. Currently, the AGA is working to pilot new methods of shortening the time to publication through the development of rapid reviews within a focused topic (e.g., opioid-induced constipation).1 The development of each guideline requires a team of one or more specially trained GRADE methodologists, two or more content experts, a medical librarian, a panel of three or more guideline authors, two AGA staff members, and the Clinical Guidelines Committee Chair.

Determining the focused questions. First, the entire team of physician-authors determines a list of focused questions that the guideline will address. This list of focused questions is translated into a table of Population, Intervention, Comparison, Outcomes (PICOs) that operationalize the general questions into search terms utilized by the medical librarian to run the systematic search as well as define the final scope of the guideline. The focused questions and related PICOs are sent to the Governing Board for review and approval.

Developing the technical review. Over the next several months, the methodologist and content experts meet on a weekly basis to review the search results question-by-question and develop the technical review of evidence that will form the basis of the clinical recommendations. For each PICO, the technical review assesses the entire body of evidence and rates the overall quality of evidence gathered for each outcome related to the PICOs (from “very low” to “low” to “moderate” to “high”).

Drafting the clinical recommendations. The technical review presents the findings of the literature along with the authors’ assessment of the evidence quality. At a face-to-face meeting, these results are presented by the technical review authors to the guideline panel, who are responsible for developing the official guideline document. The role of the guideline panel is to understand the quality of evidence and determine an ultimate list of clinical recommendations and assign a strength (strong or conditional) to each recommendation, all while considering important factors such as the balance between benefits and downsides, potential variability in patients’ values and preferences, and impact on resource utilization. Oftentimes, but not always, recommendations based on higher-quality evidence for which most patients would request the recommended course of action translate into strong recommendations. Recommendations based on lower-quality evidence and those for which there is a higher variability in patient values or issues surrounding resource utilization are more likely to be conditional.

In addition to the guideline document, the guideline panel also drafts a Clinical Decision Support Tool, which illustrates the clinical recommendations within a visual algorithm. At the same time, AGA staff draft a patient summary that explains the recommendations in plain language. This summary can be used by physicians to improve clinical communication and shared decision making with their patients.2

Revising the guideline. Each AGA technical review goes through two layers of review: once by an anonymous peer-review panel of three content experts, and again during a 30-day public comment period in which both the technical review and guideline are posted for public input. The authors take all input into consideration while finalizing the documents, which are sent to the Governing Board for final approval. Once approved by the Board, the technical review, guideline, and all related materials are submitted for publication in Gastroenterology. In addition to print publication, each guideline is disseminated on the AGA website and through the official Clinical Guidelines mobile app (available via the App Store and Google Play), which includes interactive versions of the Clinical Decision Support Tools and plain-language summaries that can be sent via e-mail to patients at the point of care. The AGA is currently pursuing future directions for the dissemination and implementation of our guidelines, such as the seamless integration of clinical recommendations into electronic health records to further improve decision making and facilitate quality measurement and improvement.

Conclusion

Not all clinical guidelines are created with equal rigor. Clinicians should examine guidelines closely and consider whether or not they follow the Institute of Medicine’s standards for trustworthy clinical guidelines: Is the focus on transparency? Is a rigorous conflict of interest system in place that eliminates major sources of financial and intellectual conflict? Was an unconflicted GRADE-trained methodologist involved in ensuring that a systematic review process is followed and the method of rating the quality of evidence and strength of recommendation follows published principles? Are the recommendations clear and actionable?3 AGA Institute guidelines are developed with the goal of striking a balance between presenting the highest ideals of evidence-based medicine while remaining responsive to the needs of everyday practitioners dealing with real patients in real clinical settings.

Ms. Siedler is the director of clinical practice at the AGA Institute national office in Bethesda, Md.; Dr. Falck-Ytter is a professor of medicine at Case-Western Reserve University, Cleveland, chair of the AGA Institute Clinical Guidelines Committee, and chief of the division of gastroenterology at the Louis Stokes VA Medical Center in Cleveland. The authors disclose no conflicts of interest.

References

1. Hanson B., Siedler M., Falck-Ytter Y., Sultan S. Introducing the rapid review: How the AGA is working to get trustworthy clinical guidelines to practitioners in less time. AGA Perspectives. 2017; in press.

2. Siedler M., Allen J., Falck-Ytter Y., Weinberg D. AGA clinical practice guidelines: Robust, evidence-based tools for guiding clinical care decisions. Gastroenterology. 2015;149:493-5.

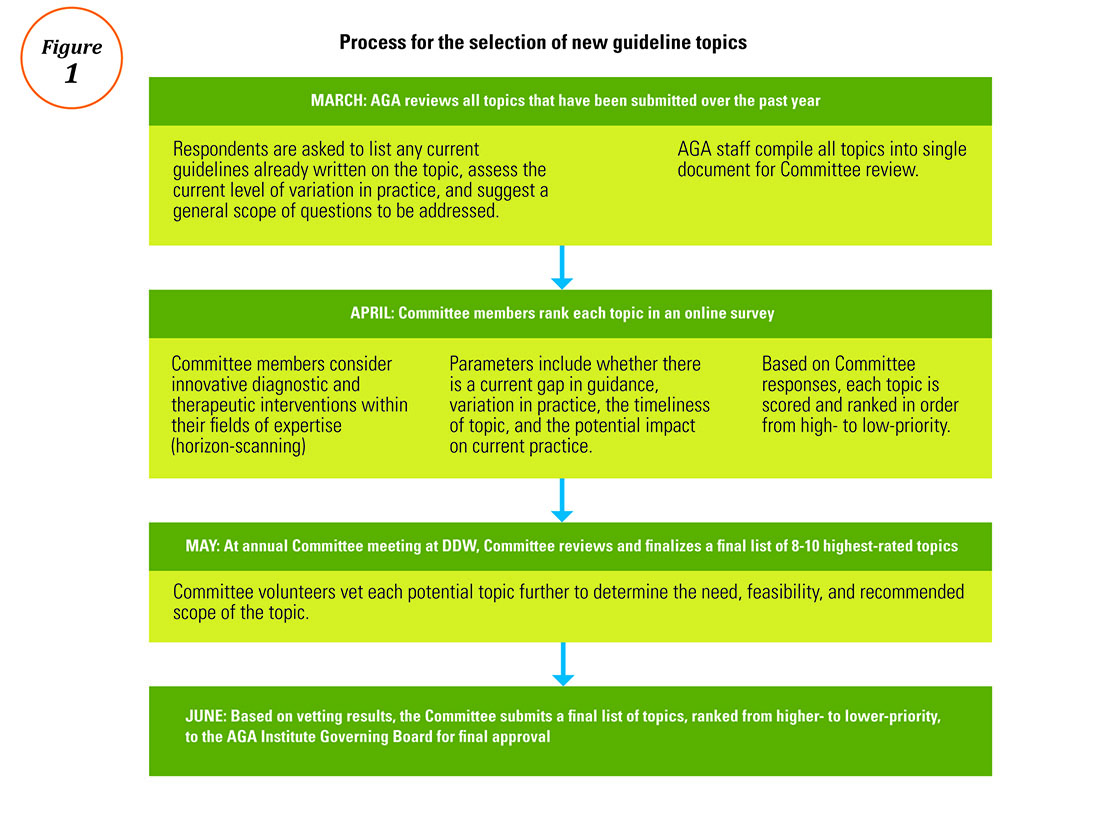

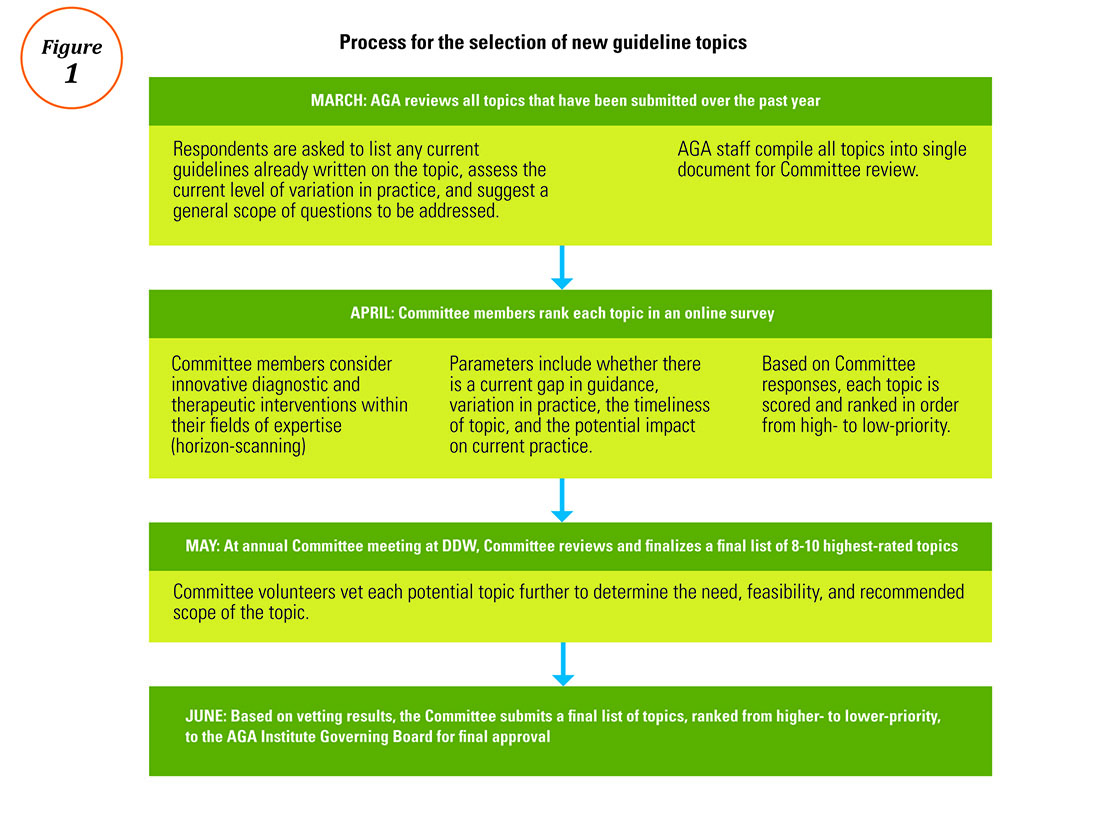

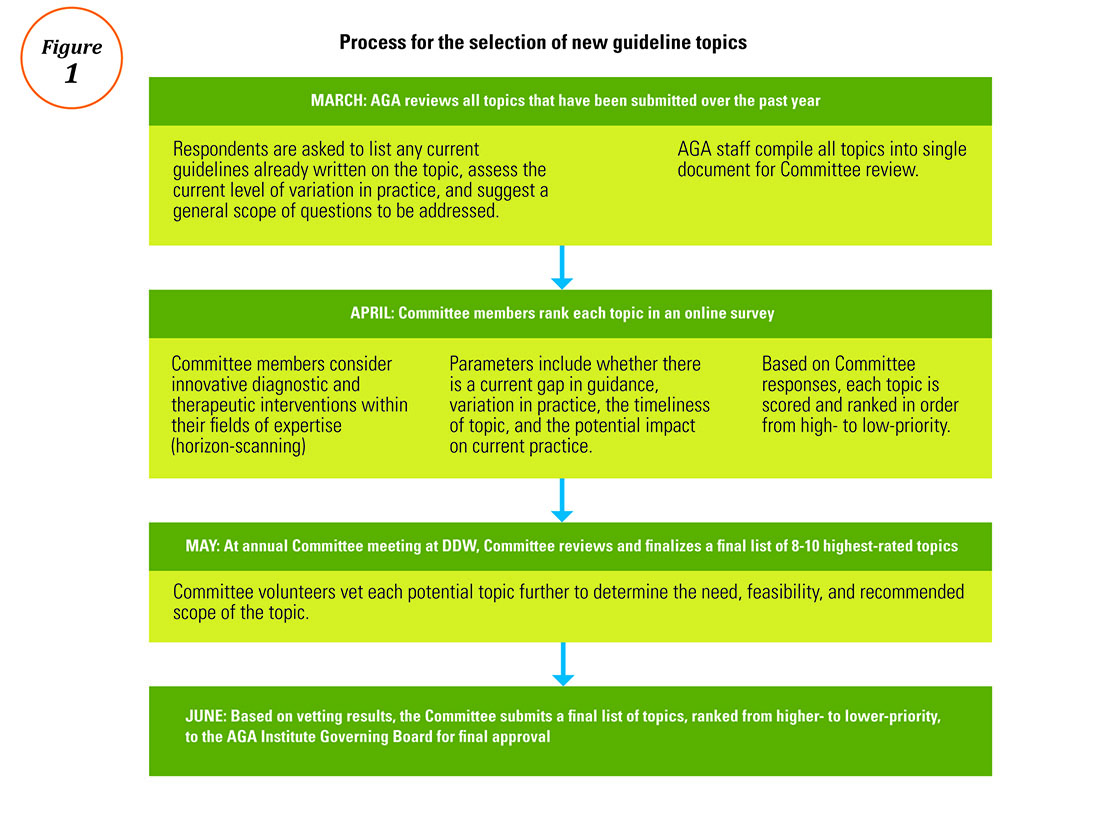

3. Institute of Medicine: Standards for developing trustworthy clinical practice guidelines. Available at http://www.nationalacademies.org/hmd/Reports/2011/Clinical-Practice-Guidelines-We-Can-Trust/Standards.aspx. Last accessed May 2017.Process for the selection of new guideline topics

The AGA understands how important it is for busy physicians to have access to the most trustworthy, actionable, and evidence-based guidelines in order to achieve the highest possible quality of patient care. According to a 2016 survey, AGA members ranked guidelines as the most important of all AGA-specific benefits, giving guidelines an average of 4.61 out of 5 (where 5 was defined as “extremely important”). The AGA’s guidelines landing page (www.gastro.org/guidelines) has long been the most frequently accessed page on the AGA website.

The life cycle of an AGA guideline

In 2010, the AGA Institute officially adopted the GRADE (Grades of Recommendation Assessment, Development, and Evaluation) methodology for the development of all future guidelines. Since the publication of our first GRADE-based guideline in 2013, the AGA has developed and published 12 guidelines with an additional 11 more to be published by 2019. Based on the systematic rigor of the GRADE approach, the AGA’s guideline development process was created to result in clinical recommendations that are not only evidence based but actionable and responsive to varying patient needs and preferences at the point of care.

All told, a single AGA guideline costs around $45,000 and takes approximately 24 months to complete and publish. Currently, the AGA is working to pilot new methods of shortening the time to publication through the development of rapid reviews within a focused topic (e.g., opioid-induced constipation).1 The development of each guideline requires a team of one or more specially trained GRADE methodologists, two or more content experts, a medical librarian, a panel of three or more guideline authors, two AGA staff members, and the Clinical Guidelines Committee Chair.

Determining the focused questions. First, the entire team of physician-authors determines a list of focused questions that the guideline will address. This list of focused questions is translated into a table of Population, Intervention, Comparison, Outcomes (PICOs) that operationalize the general questions into search terms utilized by the medical librarian to run the systematic search as well as define the final scope of the guideline. The focused questions and related PICOs are sent to the Governing Board for review and approval.

Developing the technical review. Over the next several months, the methodologist and content experts meet on a weekly basis to review the search results question-by-question and develop the technical review of evidence that will form the basis of the clinical recommendations. For each PICO, the technical review assesses the entire body of evidence and rates the overall quality of evidence gathered for each outcome related to the PICOs (from “very low” to “low” to “moderate” to “high”).

Drafting the clinical recommendations. The technical review presents the findings of the literature along with the authors’ assessment of the evidence quality. At a face-to-face meeting, these results are presented by the technical review authors to the guideline panel, who are responsible for developing the official guideline document. The role of the guideline panel is to understand the quality of evidence and determine an ultimate list of clinical recommendations and assign a strength (strong or conditional) to each recommendation, all while considering important factors such as the balance between benefits and downsides, potential variability in patients’ values and preferences, and impact on resource utilization. Oftentimes, but not always, recommendations based on higher-quality evidence for which most patients would request the recommended course of action translate into strong recommendations. Recommendations based on lower-quality evidence and those for which there is a higher variability in patient values or issues surrounding resource utilization are more likely to be conditional.

In addition to the guideline document, the guideline panel also drafts a Clinical Decision Support Tool, which illustrates the clinical recommendations within a visual algorithm. At the same time, AGA staff draft a patient summary that explains the recommendations in plain language. This summary can be used by physicians to improve clinical communication and shared decision making with their patients.2

Revising the guideline. Each AGA technical review goes through two layers of review: once by an anonymous peer-review panel of three content experts, and again during a 30-day public comment period in which both the technical review and guideline are posted for public input. The authors take all input into consideration while finalizing the documents, which are sent to the Governing Board for final approval. Once approved by the Board, the technical review, guideline, and all related materials are submitted for publication in Gastroenterology. In addition to print publication, each guideline is disseminated on the AGA website and through the official Clinical Guidelines mobile app (available via the App Store and Google Play), which includes interactive versions of the Clinical Decision Support Tools and plain-language summaries that can be sent via e-mail to patients at the point of care. The AGA is currently pursuing future directions for the dissemination and implementation of our guidelines, such as the seamless integration of clinical recommendations into electronic health records to further improve decision making and facilitate quality measurement and improvement.

Conclusion

Not all clinical guidelines are created with equal rigor. Clinicians should examine guidelines closely and consider whether or not they follow the Institute of Medicine’s standards for trustworthy clinical guidelines: Is the focus on transparency? Is a rigorous conflict of interest system in place that eliminates major sources of financial and intellectual conflict? Was an unconflicted GRADE-trained methodologist involved in ensuring that a systematic review process is followed and the method of rating the quality of evidence and strength of recommendation follows published principles? Are the recommendations clear and actionable?3 AGA Institute guidelines are developed with the goal of striking a balance between presenting the highest ideals of evidence-based medicine while remaining responsive to the needs of everyday practitioners dealing with real patients in real clinical settings.

Ms. Siedler is the director of clinical practice at the AGA Institute national office in Bethesda, Md.; Dr. Falck-Ytter is a professor of medicine at Case-Western Reserve University, Cleveland, chair of the AGA Institute Clinical Guidelines Committee, and chief of the division of gastroenterology at the Louis Stokes VA Medical Center in Cleveland. The authors disclose no conflicts of interest.

References

1. Hanson B., Siedler M., Falck-Ytter Y., Sultan S. Introducing the rapid review: How the AGA is working to get trustworthy clinical guidelines to practitioners in less time. AGA Perspectives. 2017; in press.

2. Siedler M., Allen J., Falck-Ytter Y., Weinberg D. AGA clinical practice guidelines: Robust, evidence-based tools for guiding clinical care decisions. Gastroenterology. 2015;149:493-5.

3. Institute of Medicine: Standards for developing trustworthy clinical practice guidelines. Available at http://www.nationalacademies.org/hmd/Reports/2011/Clinical-Practice-Guidelines-We-Can-Trust/Standards.aspx. Last accessed May 2017.Process for the selection of new guideline topics

The AGA understands how important it is for busy physicians to have access to the most trustworthy, actionable, and evidence-based guidelines in order to achieve the highest possible quality of patient care. According to a 2016 survey, AGA members ranked guidelines as the most important of all AGA-specific benefits, giving guidelines an average of 4.61 out of 5 (where 5 was defined as “extremely important”). The AGA’s guidelines landing page (www.gastro.org/guidelines) has long been the most frequently accessed page on the AGA website.

The life cycle of an AGA guideline

In 2010, the AGA Institute officially adopted the GRADE (Grades of Recommendation Assessment, Development, and Evaluation) methodology for the development of all future guidelines. Since the publication of our first GRADE-based guideline in 2013, the AGA has developed and published 12 guidelines with an additional 11 more to be published by 2019. Based on the systematic rigor of the GRADE approach, the AGA’s guideline development process was created to result in clinical recommendations that are not only evidence based but actionable and responsive to varying patient needs and preferences at the point of care.

All told, a single AGA guideline costs around $45,000 and takes approximately 24 months to complete and publish. Currently, the AGA is working to pilot new methods of shortening the time to publication through the development of rapid reviews within a focused topic (e.g., opioid-induced constipation).1 The development of each guideline requires a team of one or more specially trained GRADE methodologists, two or more content experts, a medical librarian, a panel of three or more guideline authors, two AGA staff members, and the Clinical Guidelines Committee Chair.

Determining the focused questions. First, the entire team of physician-authors determines a list of focused questions that the guideline will address. This list of focused questions is translated into a table of Population, Intervention, Comparison, Outcomes (PICOs) that operationalize the general questions into search terms utilized by the medical librarian to run the systematic search as well as define the final scope of the guideline. The focused questions and related PICOs are sent to the Governing Board for review and approval.

Developing the technical review. Over the next several months, the methodologist and content experts meet on a weekly basis to review the search results question-by-question and develop the technical review of evidence that will form the basis of the clinical recommendations. For each PICO, the technical review assesses the entire body of evidence and rates the overall quality of evidence gathered for each outcome related to the PICOs (from “very low” to “low” to “moderate” to “high”).

Drafting the clinical recommendations. The technical review presents the findings of the literature along with the authors’ assessment of the evidence quality. At a face-to-face meeting, these results are presented by the technical review authors to the guideline panel, who are responsible for developing the official guideline document. The role of the guideline panel is to understand the quality of evidence and determine an ultimate list of clinical recommendations and assign a strength (strong or conditional) to each recommendation, all while considering important factors such as the balance between benefits and downsides, potential variability in patients’ values and preferences, and impact on resource utilization. Oftentimes, but not always, recommendations based on higher-quality evidence for which most patients would request the recommended course of action translate into strong recommendations. Recommendations based on lower-quality evidence and those for which there is a higher variability in patient values or issues surrounding resource utilization are more likely to be conditional.

In addition to the guideline document, the guideline panel also drafts a Clinical Decision Support Tool, which illustrates the clinical recommendations within a visual algorithm. At the same time, AGA staff draft a patient summary that explains the recommendations in plain language. This summary can be used by physicians to improve clinical communication and shared decision making with their patients.2

Revising the guideline. Each AGA technical review goes through two layers of review: once by an anonymous peer-review panel of three content experts, and again during a 30-day public comment period in which both the technical review and guideline are posted for public input. The authors take all input into consideration while finalizing the documents, which are sent to the Governing Board for final approval. Once approved by the Board, the technical review, guideline, and all related materials are submitted for publication in Gastroenterology. In addition to print publication, each guideline is disseminated on the AGA website and through the official Clinical Guidelines mobile app (available via the App Store and Google Play), which includes interactive versions of the Clinical Decision Support Tools and plain-language summaries that can be sent via e-mail to patients at the point of care. The AGA is currently pursuing future directions for the dissemination and implementation of our guidelines, such as the seamless integration of clinical recommendations into electronic health records to further improve decision making and facilitate quality measurement and improvement.

Conclusion

Not all clinical guidelines are created with equal rigor. Clinicians should examine guidelines closely and consider whether or not they follow the Institute of Medicine’s standards for trustworthy clinical guidelines: Is the focus on transparency? Is a rigorous conflict of interest system in place that eliminates major sources of financial and intellectual conflict? Was an unconflicted GRADE-trained methodologist involved in ensuring that a systematic review process is followed and the method of rating the quality of evidence and strength of recommendation follows published principles? Are the recommendations clear and actionable?3 AGA Institute guidelines are developed with the goal of striking a balance between presenting the highest ideals of evidence-based medicine while remaining responsive to the needs of everyday practitioners dealing with real patients in real clinical settings.

Ms. Siedler is the director of clinical practice at the AGA Institute national office in Bethesda, Md.; Dr. Falck-Ytter is a professor of medicine at Case-Western Reserve University, Cleveland, chair of the AGA Institute Clinical Guidelines Committee, and chief of the division of gastroenterology at the Louis Stokes VA Medical Center in Cleveland. The authors disclose no conflicts of interest.

References

1. Hanson B., Siedler M., Falck-Ytter Y., Sultan S. Introducing the rapid review: How the AGA is working to get trustworthy clinical guidelines to practitioners in less time. AGA Perspectives. 2017; in press.

2. Siedler M., Allen J., Falck-Ytter Y., Weinberg D. AGA clinical practice guidelines: Robust, evidence-based tools for guiding clinical care decisions. Gastroenterology. 2015;149:493-5.

3. Institute of Medicine: Standards for developing trustworthy clinical practice guidelines. Available at http://www.nationalacademies.org/hmd/Reports/2011/Clinical-Practice-Guidelines-We-Can-Trust/Standards.aspx. Last accessed May 2017.Process for the selection of new guideline topics