User login

Tom Collins is a freelance writer in South Florida who has written about medical topics from nasty infections to ethical dilemmas, runaway tumors to tornado-chasing doctors. He travels the globe gathering conference health news and lives in West Palm Beach.

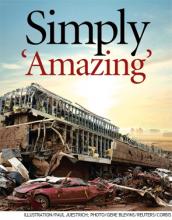

Devastating Superstorm Gone, But Not Forgotten in Moore, Okla.

–Joe R. Womble, MD

The first bit of feedback was fantastic: Everyone who had been inside the hospital—roughly 200 to 300 people, including 30 patients—had survived.

“Everyone was fine,” he said. “All the patients and staff, no one got injured. I was thinking that either the hospital was missed by the storm or that it must not have really damaged it very significantly.”

Unfortunately, the hospital was not OK. He watched as local TV painted a very different picture.

“They started showing aerial shots and I was just shocked. My jaw was just dropped,” Dr. Womble said. “The main entrance that I go in every day was literally stacked with three or four cars deep. A huge stack of about 30 cars was piled up on the main entrance, essentially.”

It was as though they were “toy cars.”

The May 20 tornado, a two-mile-wide superstorm boasting 200-mph winds that struck just south of Oklahoma City, claimed 24 lives and left the regional health system with a void in its network. It also left hospitalists mourning the loss of the place they called a second home several times a week. About a week after the storm, officials announced that Moore Medical Center would have to be demolished.

Miraculous Moments

Despite the terrible events, hospitalists and hospital officials were astounded by the good fortune of the hospital’s inhabitants. Dr. Womble said about 100 people from nearby neighborhoods and businesses used the hospital as shelter.

Senthil Raju, MD, a hospitalist who had done rounds at Moore Medical earlier that day, said the protocol was to take shelter in the hallways. But at some point, probably only minutes before the storm hit, the chief nurse and the house supervisor made the decision to move all the patients to the ground floor because they were in “reasonably stable condition,” according to Dr. Womble, who relayed accounts by staffers who were there. Most of the people in the hospital rode out the storm in the first-floor cafeteria.

After the storm, patient rooms on the second floor were either no longer there or had been reduced to their steel innards.

The decision to move everyone undoubtedly saved lives. “If any of our patients stayed there, they’re probably all dead,” Dr. Raju said.

David Whitaker, CEO of Norman Regional Health System, which includes Moore Medical, marveled at the outcome.

“We had some bumps and bruises, some scratches, but no major lacerations, no broken bones, no injuries that people couldn’t ambulate. It’s totally amazing,” he said. “The leadership that was in place, the employees that were working at that time, they sprang into action, they took command and control of the situation. They got people into the proper areas.”

Dr. Womble said hospital staff at Moore Medical had still more amazing stories of death-defiance. They told him 30 people refused to leave the chapel. Somehow, the chapel remained intact, even though the hospital all around it was destroyed. Whitaker confirmed this.

One woman in active labor was kept in a second-floor operating room—which the medical staff thought was the best place for her, all things considered. Nurses covered the woman with pillows, blankets, and their own bodies as the tornado barreled through the town. She survived and gave birth to a boy several hours later. The parents gave him the middle name Emmanuel, which means “God is with us.”

As the tornado approached, an elderly volunteer had gone outside to get something from a van he used to transport elderly patients to and from a physical therapy program. “Nobody inside knew he had gone outside,” Dr. Womble said. By the time he tried to get back in, the power had gone out, and the doors wouldn’t open. He huddled behind a concrete pillar and ended up with just one minor laceration.

Patients eventually were taken to another hospital, Norman’s HealthPlex, about five miles south. Both Dr. Womble and Dr. Raju have begun working full time at the HealthPlex.

Dr. Raju said that he avoided being at Moore Medical during the tornado only by a turn of luck. He normally rounds at Moore in the afternoon and at the HealthPlex in the morning. But on that day, there were three new admissions at Moore, and only one at HealthPlex. So he went to Moore first, and was gone by the time the tornado hit.

“So lucky,” he said.

–David Whitaker, CEO of Norman Regional Health System

The Aftermath

It remains to be seen what kind of medical facility will be built to replace Moore Medical Center.

“Nobody knows what will happen next, but a lot of us speculate that they will not rebuild an inpatient facility,” said Dr. Womble, who had worked at Moore Medical Center for four years.

Whitaker said the first priority was to re-establish the clinics located at Moore Medical, and that has been done. The next step is, possibly, a temporary building in Moore for urgent care. The long-term plan remains in the discussion phase.

“We’ve already started having some meetings,” Whitaker said. “We’re going to determine what type of facility, what service levels it will be offering as we go back.”

It’s hard knowing that his hospital is no longer there, Dr. Raju said.

“We are going to miss it,” he said. “It’s unimaginable.”

Dr. Womble said those first few hours, when he wasn’t sure of where he’d be working, were difficult. He struggles to describe the feeling of not being able to provide care at his hospital at the time it’s most needed.

“It’s really hard to put it into words,” he said. “It’s the only hospital in that city, and it’s just me and my partner to take care of virtually everyone that comes in with any kind of medical problem. I definitely feel a tie to the community.

“It’s devastating. What is the rest of the city going to do for their hospital care? They essentially will not have a hospital in their city. They’ll have to drive to another city for care.”

Tom Collins is a freelance writer in South Florida.

–Joe R. Womble, MD

The first bit of feedback was fantastic: Everyone who had been inside the hospital—roughly 200 to 300 people, including 30 patients—had survived.

“Everyone was fine,” he said. “All the patients and staff, no one got injured. I was thinking that either the hospital was missed by the storm or that it must not have really damaged it very significantly.”

Unfortunately, the hospital was not OK. He watched as local TV painted a very different picture.

“They started showing aerial shots and I was just shocked. My jaw was just dropped,” Dr. Womble said. “The main entrance that I go in every day was literally stacked with three or four cars deep. A huge stack of about 30 cars was piled up on the main entrance, essentially.”

It was as though they were “toy cars.”

The May 20 tornado, a two-mile-wide superstorm boasting 200-mph winds that struck just south of Oklahoma City, claimed 24 lives and left the regional health system with a void in its network. It also left hospitalists mourning the loss of the place they called a second home several times a week. About a week after the storm, officials announced that Moore Medical Center would have to be demolished.

Miraculous Moments

Despite the terrible events, hospitalists and hospital officials were astounded by the good fortune of the hospital’s inhabitants. Dr. Womble said about 100 people from nearby neighborhoods and businesses used the hospital as shelter.

Senthil Raju, MD, a hospitalist who had done rounds at Moore Medical earlier that day, said the protocol was to take shelter in the hallways. But at some point, probably only minutes before the storm hit, the chief nurse and the house supervisor made the decision to move all the patients to the ground floor because they were in “reasonably stable condition,” according to Dr. Womble, who relayed accounts by staffers who were there. Most of the people in the hospital rode out the storm in the first-floor cafeteria.

After the storm, patient rooms on the second floor were either no longer there or had been reduced to their steel innards.

The decision to move everyone undoubtedly saved lives. “If any of our patients stayed there, they’re probably all dead,” Dr. Raju said.

David Whitaker, CEO of Norman Regional Health System, which includes Moore Medical, marveled at the outcome.

“We had some bumps and bruises, some scratches, but no major lacerations, no broken bones, no injuries that people couldn’t ambulate. It’s totally amazing,” he said. “The leadership that was in place, the employees that were working at that time, they sprang into action, they took command and control of the situation. They got people into the proper areas.”

Dr. Womble said hospital staff at Moore Medical had still more amazing stories of death-defiance. They told him 30 people refused to leave the chapel. Somehow, the chapel remained intact, even though the hospital all around it was destroyed. Whitaker confirmed this.

One woman in active labor was kept in a second-floor operating room—which the medical staff thought was the best place for her, all things considered. Nurses covered the woman with pillows, blankets, and their own bodies as the tornado barreled through the town. She survived and gave birth to a boy several hours later. The parents gave him the middle name Emmanuel, which means “God is with us.”

As the tornado approached, an elderly volunteer had gone outside to get something from a van he used to transport elderly patients to and from a physical therapy program. “Nobody inside knew he had gone outside,” Dr. Womble said. By the time he tried to get back in, the power had gone out, and the doors wouldn’t open. He huddled behind a concrete pillar and ended up with just one minor laceration.

Patients eventually were taken to another hospital, Norman’s HealthPlex, about five miles south. Both Dr. Womble and Dr. Raju have begun working full time at the HealthPlex.

Dr. Raju said that he avoided being at Moore Medical during the tornado only by a turn of luck. He normally rounds at Moore in the afternoon and at the HealthPlex in the morning. But on that day, there were three new admissions at Moore, and only one at HealthPlex. So he went to Moore first, and was gone by the time the tornado hit.

“So lucky,” he said.

–David Whitaker, CEO of Norman Regional Health System

The Aftermath

It remains to be seen what kind of medical facility will be built to replace Moore Medical Center.

“Nobody knows what will happen next, but a lot of us speculate that they will not rebuild an inpatient facility,” said Dr. Womble, who had worked at Moore Medical Center for four years.

Whitaker said the first priority was to re-establish the clinics located at Moore Medical, and that has been done. The next step is, possibly, a temporary building in Moore for urgent care. The long-term plan remains in the discussion phase.

“We’ve already started having some meetings,” Whitaker said. “We’re going to determine what type of facility, what service levels it will be offering as we go back.”

It’s hard knowing that his hospital is no longer there, Dr. Raju said.

“We are going to miss it,” he said. “It’s unimaginable.”

Dr. Womble said those first few hours, when he wasn’t sure of where he’d be working, were difficult. He struggles to describe the feeling of not being able to provide care at his hospital at the time it’s most needed.

“It’s really hard to put it into words,” he said. “It’s the only hospital in that city, and it’s just me and my partner to take care of virtually everyone that comes in with any kind of medical problem. I definitely feel a tie to the community.

“It’s devastating. What is the rest of the city going to do for their hospital care? They essentially will not have a hospital in their city. They’ll have to drive to another city for care.”

Tom Collins is a freelance writer in South Florida.

–Joe R. Womble, MD

The first bit of feedback was fantastic: Everyone who had been inside the hospital—roughly 200 to 300 people, including 30 patients—had survived.

“Everyone was fine,” he said. “All the patients and staff, no one got injured. I was thinking that either the hospital was missed by the storm or that it must not have really damaged it very significantly.”

Unfortunately, the hospital was not OK. He watched as local TV painted a very different picture.

“They started showing aerial shots and I was just shocked. My jaw was just dropped,” Dr. Womble said. “The main entrance that I go in every day was literally stacked with three or four cars deep. A huge stack of about 30 cars was piled up on the main entrance, essentially.”

It was as though they were “toy cars.”

The May 20 tornado, a two-mile-wide superstorm boasting 200-mph winds that struck just south of Oklahoma City, claimed 24 lives and left the regional health system with a void in its network. It also left hospitalists mourning the loss of the place they called a second home several times a week. About a week after the storm, officials announced that Moore Medical Center would have to be demolished.

Miraculous Moments

Despite the terrible events, hospitalists and hospital officials were astounded by the good fortune of the hospital’s inhabitants. Dr. Womble said about 100 people from nearby neighborhoods and businesses used the hospital as shelter.

Senthil Raju, MD, a hospitalist who had done rounds at Moore Medical earlier that day, said the protocol was to take shelter in the hallways. But at some point, probably only minutes before the storm hit, the chief nurse and the house supervisor made the decision to move all the patients to the ground floor because they were in “reasonably stable condition,” according to Dr. Womble, who relayed accounts by staffers who were there. Most of the people in the hospital rode out the storm in the first-floor cafeteria.

After the storm, patient rooms on the second floor were either no longer there or had been reduced to their steel innards.

The decision to move everyone undoubtedly saved lives. “If any of our patients stayed there, they’re probably all dead,” Dr. Raju said.

David Whitaker, CEO of Norman Regional Health System, which includes Moore Medical, marveled at the outcome.

“We had some bumps and bruises, some scratches, but no major lacerations, no broken bones, no injuries that people couldn’t ambulate. It’s totally amazing,” he said. “The leadership that was in place, the employees that were working at that time, they sprang into action, they took command and control of the situation. They got people into the proper areas.”

Dr. Womble said hospital staff at Moore Medical had still more amazing stories of death-defiance. They told him 30 people refused to leave the chapel. Somehow, the chapel remained intact, even though the hospital all around it was destroyed. Whitaker confirmed this.

One woman in active labor was kept in a second-floor operating room—which the medical staff thought was the best place for her, all things considered. Nurses covered the woman with pillows, blankets, and their own bodies as the tornado barreled through the town. She survived and gave birth to a boy several hours later. The parents gave him the middle name Emmanuel, which means “God is with us.”

As the tornado approached, an elderly volunteer had gone outside to get something from a van he used to transport elderly patients to and from a physical therapy program. “Nobody inside knew he had gone outside,” Dr. Womble said. By the time he tried to get back in, the power had gone out, and the doors wouldn’t open. He huddled behind a concrete pillar and ended up with just one minor laceration.

Patients eventually were taken to another hospital, Norman’s HealthPlex, about five miles south. Both Dr. Womble and Dr. Raju have begun working full time at the HealthPlex.

Dr. Raju said that he avoided being at Moore Medical during the tornado only by a turn of luck. He normally rounds at Moore in the afternoon and at the HealthPlex in the morning. But on that day, there were three new admissions at Moore, and only one at HealthPlex. So he went to Moore first, and was gone by the time the tornado hit.

“So lucky,” he said.

–David Whitaker, CEO of Norman Regional Health System

The Aftermath

It remains to be seen what kind of medical facility will be built to replace Moore Medical Center.

“Nobody knows what will happen next, but a lot of us speculate that they will not rebuild an inpatient facility,” said Dr. Womble, who had worked at Moore Medical Center for four years.

Whitaker said the first priority was to re-establish the clinics located at Moore Medical, and that has been done. The next step is, possibly, a temporary building in Moore for urgent care. The long-term plan remains in the discussion phase.

“We’ve already started having some meetings,” Whitaker said. “We’re going to determine what type of facility, what service levels it will be offering as we go back.”

It’s hard knowing that his hospital is no longer there, Dr. Raju said.

“We are going to miss it,” he said. “It’s unimaginable.”

Dr. Womble said those first few hours, when he wasn’t sure of where he’d be working, were difficult. He struggles to describe the feeling of not being able to provide care at his hospital at the time it’s most needed.

“It’s really hard to put it into words,” he said. “It’s the only hospital in that city, and it’s just me and my partner to take care of virtually everyone that comes in with any kind of medical problem. I definitely feel a tie to the community.

“It’s devastating. What is the rest of the city going to do for their hospital care? They essentially will not have a hospital in their city. They’ll have to drive to another city for care.”

Tom Collins is a freelance writer in South Florida.

11 Things Neurologists Think Hospitalists Need To Know

11 Things: At a Glance

- You might be overdiagnosing transient ischemic attacks (TIA).

- Early mobilization after a stroke might be better for some patients.

- MRI is the best tool to evaluate TIA patients.

- Consider focal seizure or complex partial seizure as one of the possible causes of confusion or speech disturbance, or both.

- Tracking the time a hospitalized patient was last seen to be normal is crucial.

- Consider neuromuscular disorders when a patient presents with weakness.

- Urinary tract infections (UTIs) are not the only cause of altered mental status.

- Take care in distinguishing aphasia from general confusion.

- A simple checklist might eliminate the need to consult the neurologist.

- Calling a neurologist earlier is way better than calling later.

- Hire a neurohospitalist if your institution doesn’t have one already.

When a patient is admitted to the hospital with neurological symptoms, such as altered mental status, he or she might not be the only one who is confused. Hospitalists might be a little confused, too.

Of all the subspecialties to which hospitalists are exposed, none might make them more uncomfortable than neurology. Because of what often is a dearth of training in this area, and because of the vexing and sometimes fleeting nature of symptoms, hospitalists might be inclined to lean on neurologists more than other specialists.

The Hospitalist spoke with a half-dozen experts, gathering their words of guidance and clinical tips. Here’s hoping they give you a little extra confidence the next time you see a patient with altered mental status.

You might be overdiagnosing transient ischemic attacks (TIA).

Ira Chang, MD, a neurohospitalist with Blue Sky Neurology in Englewood, Colo., and assistant clinical professor at the University of Colorado Health Sciences Center in Denver, says TIA is all too commonly a go-to diagnosis, frequently when there’s another cause.

“I think that hospitalists, and maybe medical internists in general, are very quick to diagnose anything that has a neurologic symptom that comes and goes as a TIA,” she says. “Patients have to have specific neurologic symptoms that we think are due to arterial blood flow or ischemia problems.”

Near-fainting spells and dizzy spells involving confusion commonly are diagnosed as TIA when these symptoms could be due to “a number of other causes,” Dr. Chang adds.

Kevin Barrett, MD, assistant professor of neurology and a neurohospitalist at Mayo Clinic in Jacksonville, Fla., says the suspicion of a TIA should be greater if the patient is older or has traditional cardiovascular risk factors, such as hyptertension, diabetes, hyperlipidemia, or tobacco use.

A TIA typically causes symptoms referable to common arterial distributions. Carotid-distribution TIA often causes ipsilateral loss of vision and contralateral weakness or numbness. Posterior-circulation TIAs bring on symptoms such as ataxia, unilateral or bilateral limb weakness, diplopia, and slurred or slow speech.

TIA diagnoses can be tricky even for those trained in neurology, Dr. Barrett says.

“Even among fellowship-trained vascular neurologists, TIA can be a challenging diagnosis, often with poor inter-observer agreement,” he notes.

Early mobilization after a stroke might be better for some patients.

After receiving tissue plasminogen activator (tPA) therapy for stroke, patients historically were kept on bed rest for 24 hours to reduce the risk of hemorrhage. Evidence now is coming to light that some patients might benefit from getting out of bed sooner, Dr. Barrett says.1

“We’re learning that in selected patients, they can actually be mobilized at 12 hours,” he says. “In some cases, that would not only reduce the risk of complications related to immobilization like DVT but shorten length of stay. These are all important metrics for anybody who practices primarily within an inpatient setting.”

Early mobilization generally is more suitable for patients with less severe deficits and who are hemodynamically stable.

MRI is the best tool to evaluate TIA patients.

TIA patients who have transient symptoms and normal diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI) abnormalities on an MRI are at a very low risk. “Less than 1% of those patients have a stroke within the subsequent seven days,” Dr. Barrett says.2 “But those patients who do have a DWI abnormality, they’re at very high risk: 7.1% at seven days.

“The utility of MRI following TIA is becoming very much apparent. It is something that hospitalists should be aware of.”

Consider focal seizure or complex partial seizure as one of the possible causes of confusion or speech disturbance, or both.

Patients experiencing confusion or speech disturbance or altered mentation—particularly if they’re elderly or have dementia—could be having a partial seizure, Dr. Chang says. Dementia patients have a 10% to 15% incidence of complex partial seizures, she says.

“I see that underdiagnosed a lot,” she says. “They keep coming back, and everybody diagnoses them with TIAs. So they keep getting put on aspirin, and they get switched to Aggrenox [to prevent clotting]. They keep coming back with the same symptoms.”

Tracking the time a hospitalized patient was last seen to be normal is crucial.

About 10% to 15% of strokes occur in patients who are in the hospital.

“While a lot of those strokes are perioperative, there also are patients who are going to be on hospitalist services,” says Eric Adelman, MD, assistant professor of neurology at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor.

Hospitalists should note that patients suffering strokes are found not just in the ED but also on the floor, where all the tools for treatment might not be as readily available. That makes those cases a challenge and makes forethought that much more important, Dr. Adelman says.

“It’s a matter of trying to track down last normal times,” he says. “If they’re eligible for tPA and they’re within the therapeutic window, we should be able to do that within a hospital.”

Establishing a neurological baseline is particularly important for patients who are at higher stroke risk, like those with atrial fibrillation and other cardiovascular risk factors.

“In case something does happen,” Dr. Adelman says, “at least you have a baseline so you can [know that] at time X, we knew they had full strength in their right arm, and now they don’t.”

Consider neuromuscular disorders when a patient presents with weakness.

It’s safe to say some hospitalists might miss a neuromuscular disorder, Dr. Chang says.

“A lot of disorders that are harder for hospitalists to diagnose and that tend to take longer to call a neurologist [on] are things that are due to myasthenia gravis [a breakdown between nerves and muscles leading to muscle fatigue], myopathy, or ALS,” she says. “Many patients present with weakness. I think a lot of times there will be a lot of tests on and a lot of treatment for general medical conditions that can cause weakness.”

And that might be a case of misdirected attention. Patients with weakness accompanied by persistent swallowing problems, slurred speech with no other obvious cause, or the inability to lift their head off the bed without an obvious cause may end up with a neuromuscular diagnosis, she says.

It would be helpful to have a neurologist’s input in these cases, she says, where “nothing’s getting better, and three, four, five days later, the patient’s still weak.

“I think a neurologist would be more in tune with something like that,” she adds.

Urinary tract infections (UTIs) are not the only cause of altered mental status.

That might seem obvious, but too often, a UTI can be pegged as the source of altered mental status when it should not be, Dr. Chang says.

“We get a lot of people who come in with confusion and they have a slightly abnormal urinalysis and they diagnose them with UTI,” Dr. Chang says. “And it turns out that they actually had a stroke or they had a seizure.”

Significantly altered mentation should show a significantly abnormal urine with a positive culture, she says. “They ought to have significant laboratory support for a urinary tract infection.”

Dr. Barrett says a neurologic review of systems, or at least a neurologic exam, should be the physician’s guide.

“Those are key parts of a hospitalist’s practice,” he says, “because that’s what’s truly going to guide them to consider primary neurological causes of altered mental status.”

Take care in distinguishing aphasia from general confusion.

If a patient is still talking and is fairly fluent, that doesn’t mean they aren’t suffering from certain types of aphasia, a disorder caused by damage to parts of the brain that control language, Dr. Adelman says.

“Oftentimes, when you’re dealing with a patient with confusion, you want to make sure that it’s confusion, or encephalopathy, rather than a focal neurologic problem like aphasia,” he says. “Frequently patients with aphasia will have other symptoms such as a facial drop or weakness in the arm, but stroke can present as isolated aphasia.”

A good habit to get into is to determine whether the patient can repeat a phrase, follow a command, or name objects, he says. If they can, they probably do not have aphasia.

“The thing that you worry about with aphasia, particularly acute onset aphasia, is an ischemic stroke,” Dr. Adelman says.

A simple checklist might eliminate the need to consult the neurologist.

When Edgar Kenton, MD, now director of the stroke program at Geisinger Health System in Danville, Pa., was at Emory University Hospital in Atlanta, he found he was getting snowed under with consults from hospitalists. There were about 15 hospitalists for just one or two neurologists.

“There was no way I was able to see these patients, particularly in follow-up, because you might get five consults every day,” he says. “By the middle of the week, that’s 15 consults. You don’t get a chance to go back and see the patients because you’re just going from one consult to the other.”

The situation improved with a checklist of things to consider when a patient presents with altered mental status. Before seeking a consult, neurologists suggested the hospitalists check the electrolytes, blood pressure, and urine, and use CT scans as a screening test. That might uncover the root of the patient’s problems. If those are clear, by all means get the neurologist involved, he says.

“We were able to educate the hospitalists so they knew when to call; they knew when it was beyond their expertise to take care of the patient, so we weren’t getting called for every patient with altered mental status when all they needed to do was to check the electrolytes,” Dr. Kenton says.

Calling a neurologist earlier is way better than calling later.

Once the decision is made to consult with a neurologist, the consult should be done right away, Dr. Kenton says, not after a few days when symptoms don’t appear to be improving.

“We’ll get the call on a Friday afternoon because they thought, finally, ‘Well, you know, we need to get neurology involved because we a) haven’t solved the problem and b) there may be some other tests we should be getting,’” he says of common situations. “That has been a problem. If you don’t have a neurohospitalist involved day by day, working with the patient and the general hospitalist, neurology becomes an afterthought.”

He says accurate and early diagnosis is paramount to the patient.

“If the diagnosis is delayed, obviously there’s more insult to the patients, more persistent insult,” he says, noting the timing is particularly important in neurological conditions “because things can get bad in a hurry.”

He strongly urges hospitalists to consult with a neurologist before ordering an entire battery of tests.

At Geisinger, neurologists are encouraging hospitalists to chat informally with neurosurgeons about cases for guidance at the outset rather than after several days.

Hire a neurohospitalist if your institution doesn’t have one already.

At the top of the list of Dr. Kenton’s suggestions on caring for hospitalized neurology patients is this declaration: “Get a neurohospitalist.”

“It’s important to have the neurologist involved from the time the patient’s admitted,” he says. “That’s the value of connecting the general hospitalist with neurologists.”

S. Andrew Josephson, MD, director of the neurohospitalist program at the University of California at San Francisco, says his colleagues are team players and improve patient care.

“Neurology consultations can be called very quickly, and a nice partnership can develop between internal medicine hospitalists and neurohospitalists to care for those patients who have those medical and neurologic problems,” he says.

He also says having a neurohospitalist on board can ease some of the tension.

“No longer if there’s a neurologic condition does a hospitalist have to think about, ‘Well, does this rise to the level of something that I need to get the neurologist to drive across the city to come see?’” he explains. “‘Or is this something we should try to manage ourselves?’”

Tom Collins is a freelance writer in South Florida.

References

- Bernhardt J, Dewey H, Thrift A, Collier J, Donnan G. A very early rehabilitation trial for stroke (AVERT): phase II safety and feasibility. Stroke. 2008;39;390-396.

- Giles MF, Albers GW, Amarenco P, et al. Early stroke risk and ABCD2 score performance in tissue- vs. time-defined TIA: a multicenter study. Neurology. 2011;77(13):1222-1228.

- Zinchuk AV, Flanagan EP, Tubridy NJ, Miller WA, McCullough LD. Attitudes of US medical trainees towards neurology education: “Neurophobia”—a global issue. BMC Med Educ. 2010;10:49.

11 Things: At a Glance

- You might be overdiagnosing transient ischemic attacks (TIA).

- Early mobilization after a stroke might be better for some patients.

- MRI is the best tool to evaluate TIA patients.

- Consider focal seizure or complex partial seizure as one of the possible causes of confusion or speech disturbance, or both.

- Tracking the time a hospitalized patient was last seen to be normal is crucial.

- Consider neuromuscular disorders when a patient presents with weakness.

- Urinary tract infections (UTIs) are not the only cause of altered mental status.

- Take care in distinguishing aphasia from general confusion.

- A simple checklist might eliminate the need to consult the neurologist.

- Calling a neurologist earlier is way better than calling later.

- Hire a neurohospitalist if your institution doesn’t have one already.

When a patient is admitted to the hospital with neurological symptoms, such as altered mental status, he or she might not be the only one who is confused. Hospitalists might be a little confused, too.

Of all the subspecialties to which hospitalists are exposed, none might make them more uncomfortable than neurology. Because of what often is a dearth of training in this area, and because of the vexing and sometimes fleeting nature of symptoms, hospitalists might be inclined to lean on neurologists more than other specialists.

The Hospitalist spoke with a half-dozen experts, gathering their words of guidance and clinical tips. Here’s hoping they give you a little extra confidence the next time you see a patient with altered mental status.

You might be overdiagnosing transient ischemic attacks (TIA).

Ira Chang, MD, a neurohospitalist with Blue Sky Neurology in Englewood, Colo., and assistant clinical professor at the University of Colorado Health Sciences Center in Denver, says TIA is all too commonly a go-to diagnosis, frequently when there’s another cause.

“I think that hospitalists, and maybe medical internists in general, are very quick to diagnose anything that has a neurologic symptom that comes and goes as a TIA,” she says. “Patients have to have specific neurologic symptoms that we think are due to arterial blood flow or ischemia problems.”

Near-fainting spells and dizzy spells involving confusion commonly are diagnosed as TIA when these symptoms could be due to “a number of other causes,” Dr. Chang adds.

Kevin Barrett, MD, assistant professor of neurology and a neurohospitalist at Mayo Clinic in Jacksonville, Fla., says the suspicion of a TIA should be greater if the patient is older or has traditional cardiovascular risk factors, such as hyptertension, diabetes, hyperlipidemia, or tobacco use.

A TIA typically causes symptoms referable to common arterial distributions. Carotid-distribution TIA often causes ipsilateral loss of vision and contralateral weakness or numbness. Posterior-circulation TIAs bring on symptoms such as ataxia, unilateral or bilateral limb weakness, diplopia, and slurred or slow speech.

TIA diagnoses can be tricky even for those trained in neurology, Dr. Barrett says.

“Even among fellowship-trained vascular neurologists, TIA can be a challenging diagnosis, often with poor inter-observer agreement,” he notes.

Early mobilization after a stroke might be better for some patients.

After receiving tissue plasminogen activator (tPA) therapy for stroke, patients historically were kept on bed rest for 24 hours to reduce the risk of hemorrhage. Evidence now is coming to light that some patients might benefit from getting out of bed sooner, Dr. Barrett says.1

“We’re learning that in selected patients, they can actually be mobilized at 12 hours,” he says. “In some cases, that would not only reduce the risk of complications related to immobilization like DVT but shorten length of stay. These are all important metrics for anybody who practices primarily within an inpatient setting.”

Early mobilization generally is more suitable for patients with less severe deficits and who are hemodynamically stable.

MRI is the best tool to evaluate TIA patients.

TIA patients who have transient symptoms and normal diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI) abnormalities on an MRI are at a very low risk. “Less than 1% of those patients have a stroke within the subsequent seven days,” Dr. Barrett says.2 “But those patients who do have a DWI abnormality, they’re at very high risk: 7.1% at seven days.

“The utility of MRI following TIA is becoming very much apparent. It is something that hospitalists should be aware of.”

Consider focal seizure or complex partial seizure as one of the possible causes of confusion or speech disturbance, or both.

Patients experiencing confusion or speech disturbance or altered mentation—particularly if they’re elderly or have dementia—could be having a partial seizure, Dr. Chang says. Dementia patients have a 10% to 15% incidence of complex partial seizures, she says.

“I see that underdiagnosed a lot,” she says. “They keep coming back, and everybody diagnoses them with TIAs. So they keep getting put on aspirin, and they get switched to Aggrenox [to prevent clotting]. They keep coming back with the same symptoms.”

Tracking the time a hospitalized patient was last seen to be normal is crucial.

About 10% to 15% of strokes occur in patients who are in the hospital.

“While a lot of those strokes are perioperative, there also are patients who are going to be on hospitalist services,” says Eric Adelman, MD, assistant professor of neurology at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor.

Hospitalists should note that patients suffering strokes are found not just in the ED but also on the floor, where all the tools for treatment might not be as readily available. That makes those cases a challenge and makes forethought that much more important, Dr. Adelman says.

“It’s a matter of trying to track down last normal times,” he says. “If they’re eligible for tPA and they’re within the therapeutic window, we should be able to do that within a hospital.”

Establishing a neurological baseline is particularly important for patients who are at higher stroke risk, like those with atrial fibrillation and other cardiovascular risk factors.

“In case something does happen,” Dr. Adelman says, “at least you have a baseline so you can [know that] at time X, we knew they had full strength in their right arm, and now they don’t.”

Consider neuromuscular disorders when a patient presents with weakness.

It’s safe to say some hospitalists might miss a neuromuscular disorder, Dr. Chang says.

“A lot of disorders that are harder for hospitalists to diagnose and that tend to take longer to call a neurologist [on] are things that are due to myasthenia gravis [a breakdown between nerves and muscles leading to muscle fatigue], myopathy, or ALS,” she says. “Many patients present with weakness. I think a lot of times there will be a lot of tests on and a lot of treatment for general medical conditions that can cause weakness.”

And that might be a case of misdirected attention. Patients with weakness accompanied by persistent swallowing problems, slurred speech with no other obvious cause, or the inability to lift their head off the bed without an obvious cause may end up with a neuromuscular diagnosis, she says.

It would be helpful to have a neurologist’s input in these cases, she says, where “nothing’s getting better, and three, four, five days later, the patient’s still weak.

“I think a neurologist would be more in tune with something like that,” she adds.

Urinary tract infections (UTIs) are not the only cause of altered mental status.

That might seem obvious, but too often, a UTI can be pegged as the source of altered mental status when it should not be, Dr. Chang says.

“We get a lot of people who come in with confusion and they have a slightly abnormal urinalysis and they diagnose them with UTI,” Dr. Chang says. “And it turns out that they actually had a stroke or they had a seizure.”

Significantly altered mentation should show a significantly abnormal urine with a positive culture, she says. “They ought to have significant laboratory support for a urinary tract infection.”

Dr. Barrett says a neurologic review of systems, or at least a neurologic exam, should be the physician’s guide.

“Those are key parts of a hospitalist’s practice,” he says, “because that’s what’s truly going to guide them to consider primary neurological causes of altered mental status.”

Take care in distinguishing aphasia from general confusion.

If a patient is still talking and is fairly fluent, that doesn’t mean they aren’t suffering from certain types of aphasia, a disorder caused by damage to parts of the brain that control language, Dr. Adelman says.

“Oftentimes, when you’re dealing with a patient with confusion, you want to make sure that it’s confusion, or encephalopathy, rather than a focal neurologic problem like aphasia,” he says. “Frequently patients with aphasia will have other symptoms such as a facial drop or weakness in the arm, but stroke can present as isolated aphasia.”

A good habit to get into is to determine whether the patient can repeat a phrase, follow a command, or name objects, he says. If they can, they probably do not have aphasia.

“The thing that you worry about with aphasia, particularly acute onset aphasia, is an ischemic stroke,” Dr. Adelman says.

A simple checklist might eliminate the need to consult the neurologist.

When Edgar Kenton, MD, now director of the stroke program at Geisinger Health System in Danville, Pa., was at Emory University Hospital in Atlanta, he found he was getting snowed under with consults from hospitalists. There were about 15 hospitalists for just one or two neurologists.

“There was no way I was able to see these patients, particularly in follow-up, because you might get five consults every day,” he says. “By the middle of the week, that’s 15 consults. You don’t get a chance to go back and see the patients because you’re just going from one consult to the other.”

The situation improved with a checklist of things to consider when a patient presents with altered mental status. Before seeking a consult, neurologists suggested the hospitalists check the electrolytes, blood pressure, and urine, and use CT scans as a screening test. That might uncover the root of the patient’s problems. If those are clear, by all means get the neurologist involved, he says.

“We were able to educate the hospitalists so they knew when to call; they knew when it was beyond their expertise to take care of the patient, so we weren’t getting called for every patient with altered mental status when all they needed to do was to check the electrolytes,” Dr. Kenton says.

Calling a neurologist earlier is way better than calling later.

Once the decision is made to consult with a neurologist, the consult should be done right away, Dr. Kenton says, not after a few days when symptoms don’t appear to be improving.

“We’ll get the call on a Friday afternoon because they thought, finally, ‘Well, you know, we need to get neurology involved because we a) haven’t solved the problem and b) there may be some other tests we should be getting,’” he says of common situations. “That has been a problem. If you don’t have a neurohospitalist involved day by day, working with the patient and the general hospitalist, neurology becomes an afterthought.”

He says accurate and early diagnosis is paramount to the patient.

“If the diagnosis is delayed, obviously there’s more insult to the patients, more persistent insult,” he says, noting the timing is particularly important in neurological conditions “because things can get bad in a hurry.”

He strongly urges hospitalists to consult with a neurologist before ordering an entire battery of tests.

At Geisinger, neurologists are encouraging hospitalists to chat informally with neurosurgeons about cases for guidance at the outset rather than after several days.

Hire a neurohospitalist if your institution doesn’t have one already.

At the top of the list of Dr. Kenton’s suggestions on caring for hospitalized neurology patients is this declaration: “Get a neurohospitalist.”

“It’s important to have the neurologist involved from the time the patient’s admitted,” he says. “That’s the value of connecting the general hospitalist with neurologists.”

S. Andrew Josephson, MD, director of the neurohospitalist program at the University of California at San Francisco, says his colleagues are team players and improve patient care.

“Neurology consultations can be called very quickly, and a nice partnership can develop between internal medicine hospitalists and neurohospitalists to care for those patients who have those medical and neurologic problems,” he says.

He also says having a neurohospitalist on board can ease some of the tension.

“No longer if there’s a neurologic condition does a hospitalist have to think about, ‘Well, does this rise to the level of something that I need to get the neurologist to drive across the city to come see?’” he explains. “‘Or is this something we should try to manage ourselves?’”

Tom Collins is a freelance writer in South Florida.

References

- Bernhardt J, Dewey H, Thrift A, Collier J, Donnan G. A very early rehabilitation trial for stroke (AVERT): phase II safety and feasibility. Stroke. 2008;39;390-396.

- Giles MF, Albers GW, Amarenco P, et al. Early stroke risk and ABCD2 score performance in tissue- vs. time-defined TIA: a multicenter study. Neurology. 2011;77(13):1222-1228.

- Zinchuk AV, Flanagan EP, Tubridy NJ, Miller WA, McCullough LD. Attitudes of US medical trainees towards neurology education: “Neurophobia”—a global issue. BMC Med Educ. 2010;10:49.

11 Things: At a Glance

- You might be overdiagnosing transient ischemic attacks (TIA).

- Early mobilization after a stroke might be better for some patients.

- MRI is the best tool to evaluate TIA patients.

- Consider focal seizure or complex partial seizure as one of the possible causes of confusion or speech disturbance, or both.

- Tracking the time a hospitalized patient was last seen to be normal is crucial.

- Consider neuromuscular disorders when a patient presents with weakness.

- Urinary tract infections (UTIs) are not the only cause of altered mental status.

- Take care in distinguishing aphasia from general confusion.

- A simple checklist might eliminate the need to consult the neurologist.

- Calling a neurologist earlier is way better than calling later.

- Hire a neurohospitalist if your institution doesn’t have one already.

When a patient is admitted to the hospital with neurological symptoms, such as altered mental status, he or she might not be the only one who is confused. Hospitalists might be a little confused, too.

Of all the subspecialties to which hospitalists are exposed, none might make them more uncomfortable than neurology. Because of what often is a dearth of training in this area, and because of the vexing and sometimes fleeting nature of symptoms, hospitalists might be inclined to lean on neurologists more than other specialists.

The Hospitalist spoke with a half-dozen experts, gathering their words of guidance and clinical tips. Here’s hoping they give you a little extra confidence the next time you see a patient with altered mental status.

You might be overdiagnosing transient ischemic attacks (TIA).

Ira Chang, MD, a neurohospitalist with Blue Sky Neurology in Englewood, Colo., and assistant clinical professor at the University of Colorado Health Sciences Center in Denver, says TIA is all too commonly a go-to diagnosis, frequently when there’s another cause.

“I think that hospitalists, and maybe medical internists in general, are very quick to diagnose anything that has a neurologic symptom that comes and goes as a TIA,” she says. “Patients have to have specific neurologic symptoms that we think are due to arterial blood flow or ischemia problems.”

Near-fainting spells and dizzy spells involving confusion commonly are diagnosed as TIA when these symptoms could be due to “a number of other causes,” Dr. Chang adds.

Kevin Barrett, MD, assistant professor of neurology and a neurohospitalist at Mayo Clinic in Jacksonville, Fla., says the suspicion of a TIA should be greater if the patient is older or has traditional cardiovascular risk factors, such as hyptertension, diabetes, hyperlipidemia, or tobacco use.

A TIA typically causes symptoms referable to common arterial distributions. Carotid-distribution TIA often causes ipsilateral loss of vision and contralateral weakness or numbness. Posterior-circulation TIAs bring on symptoms such as ataxia, unilateral or bilateral limb weakness, diplopia, and slurred or slow speech.

TIA diagnoses can be tricky even for those trained in neurology, Dr. Barrett says.

“Even among fellowship-trained vascular neurologists, TIA can be a challenging diagnosis, often with poor inter-observer agreement,” he notes.

Early mobilization after a stroke might be better for some patients.

After receiving tissue plasminogen activator (tPA) therapy for stroke, patients historically were kept on bed rest for 24 hours to reduce the risk of hemorrhage. Evidence now is coming to light that some patients might benefit from getting out of bed sooner, Dr. Barrett says.1

“We’re learning that in selected patients, they can actually be mobilized at 12 hours,” he says. “In some cases, that would not only reduce the risk of complications related to immobilization like DVT but shorten length of stay. These are all important metrics for anybody who practices primarily within an inpatient setting.”

Early mobilization generally is more suitable for patients with less severe deficits and who are hemodynamically stable.

MRI is the best tool to evaluate TIA patients.

TIA patients who have transient symptoms and normal diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI) abnormalities on an MRI are at a very low risk. “Less than 1% of those patients have a stroke within the subsequent seven days,” Dr. Barrett says.2 “But those patients who do have a DWI abnormality, they’re at very high risk: 7.1% at seven days.

“The utility of MRI following TIA is becoming very much apparent. It is something that hospitalists should be aware of.”

Consider focal seizure or complex partial seizure as one of the possible causes of confusion or speech disturbance, or both.

Patients experiencing confusion or speech disturbance or altered mentation—particularly if they’re elderly or have dementia—could be having a partial seizure, Dr. Chang says. Dementia patients have a 10% to 15% incidence of complex partial seizures, she says.

“I see that underdiagnosed a lot,” she says. “They keep coming back, and everybody diagnoses them with TIAs. So they keep getting put on aspirin, and they get switched to Aggrenox [to prevent clotting]. They keep coming back with the same symptoms.”

Tracking the time a hospitalized patient was last seen to be normal is crucial.

About 10% to 15% of strokes occur in patients who are in the hospital.

“While a lot of those strokes are perioperative, there also are patients who are going to be on hospitalist services,” says Eric Adelman, MD, assistant professor of neurology at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor.

Hospitalists should note that patients suffering strokes are found not just in the ED but also on the floor, where all the tools for treatment might not be as readily available. That makes those cases a challenge and makes forethought that much more important, Dr. Adelman says.

“It’s a matter of trying to track down last normal times,” he says. “If they’re eligible for tPA and they’re within the therapeutic window, we should be able to do that within a hospital.”

Establishing a neurological baseline is particularly important for patients who are at higher stroke risk, like those with atrial fibrillation and other cardiovascular risk factors.

“In case something does happen,” Dr. Adelman says, “at least you have a baseline so you can [know that] at time X, we knew they had full strength in their right arm, and now they don’t.”

Consider neuromuscular disorders when a patient presents with weakness.

It’s safe to say some hospitalists might miss a neuromuscular disorder, Dr. Chang says.

“A lot of disorders that are harder for hospitalists to diagnose and that tend to take longer to call a neurologist [on] are things that are due to myasthenia gravis [a breakdown between nerves and muscles leading to muscle fatigue], myopathy, or ALS,” she says. “Many patients present with weakness. I think a lot of times there will be a lot of tests on and a lot of treatment for general medical conditions that can cause weakness.”

And that might be a case of misdirected attention. Patients with weakness accompanied by persistent swallowing problems, slurred speech with no other obvious cause, or the inability to lift their head off the bed without an obvious cause may end up with a neuromuscular diagnosis, she says.

It would be helpful to have a neurologist’s input in these cases, she says, where “nothing’s getting better, and three, four, five days later, the patient’s still weak.

“I think a neurologist would be more in tune with something like that,” she adds.

Urinary tract infections (UTIs) are not the only cause of altered mental status.

That might seem obvious, but too often, a UTI can be pegged as the source of altered mental status when it should not be, Dr. Chang says.

“We get a lot of people who come in with confusion and they have a slightly abnormal urinalysis and they diagnose them with UTI,” Dr. Chang says. “And it turns out that they actually had a stroke or they had a seizure.”

Significantly altered mentation should show a significantly abnormal urine with a positive culture, she says. “They ought to have significant laboratory support for a urinary tract infection.”

Dr. Barrett says a neurologic review of systems, or at least a neurologic exam, should be the physician’s guide.

“Those are key parts of a hospitalist’s practice,” he says, “because that’s what’s truly going to guide them to consider primary neurological causes of altered mental status.”

Take care in distinguishing aphasia from general confusion.

If a patient is still talking and is fairly fluent, that doesn’t mean they aren’t suffering from certain types of aphasia, a disorder caused by damage to parts of the brain that control language, Dr. Adelman says.

“Oftentimes, when you’re dealing with a patient with confusion, you want to make sure that it’s confusion, or encephalopathy, rather than a focal neurologic problem like aphasia,” he says. “Frequently patients with aphasia will have other symptoms such as a facial drop or weakness in the arm, but stroke can present as isolated aphasia.”

A good habit to get into is to determine whether the patient can repeat a phrase, follow a command, or name objects, he says. If they can, they probably do not have aphasia.

“The thing that you worry about with aphasia, particularly acute onset aphasia, is an ischemic stroke,” Dr. Adelman says.

A simple checklist might eliminate the need to consult the neurologist.

When Edgar Kenton, MD, now director of the stroke program at Geisinger Health System in Danville, Pa., was at Emory University Hospital in Atlanta, he found he was getting snowed under with consults from hospitalists. There were about 15 hospitalists for just one or two neurologists.

“There was no way I was able to see these patients, particularly in follow-up, because you might get five consults every day,” he says. “By the middle of the week, that’s 15 consults. You don’t get a chance to go back and see the patients because you’re just going from one consult to the other.”

The situation improved with a checklist of things to consider when a patient presents with altered mental status. Before seeking a consult, neurologists suggested the hospitalists check the electrolytes, blood pressure, and urine, and use CT scans as a screening test. That might uncover the root of the patient’s problems. If those are clear, by all means get the neurologist involved, he says.

“We were able to educate the hospitalists so they knew when to call; they knew when it was beyond their expertise to take care of the patient, so we weren’t getting called for every patient with altered mental status when all they needed to do was to check the electrolytes,” Dr. Kenton says.

Calling a neurologist earlier is way better than calling later.

Once the decision is made to consult with a neurologist, the consult should be done right away, Dr. Kenton says, not after a few days when symptoms don’t appear to be improving.

“We’ll get the call on a Friday afternoon because they thought, finally, ‘Well, you know, we need to get neurology involved because we a) haven’t solved the problem and b) there may be some other tests we should be getting,’” he says of common situations. “That has been a problem. If you don’t have a neurohospitalist involved day by day, working with the patient and the general hospitalist, neurology becomes an afterthought.”

He says accurate and early diagnosis is paramount to the patient.

“If the diagnosis is delayed, obviously there’s more insult to the patients, more persistent insult,” he says, noting the timing is particularly important in neurological conditions “because things can get bad in a hurry.”

He strongly urges hospitalists to consult with a neurologist before ordering an entire battery of tests.

At Geisinger, neurologists are encouraging hospitalists to chat informally with neurosurgeons about cases for guidance at the outset rather than after several days.

Hire a neurohospitalist if your institution doesn’t have one already.

At the top of the list of Dr. Kenton’s suggestions on caring for hospitalized neurology patients is this declaration: “Get a neurohospitalist.”

“It’s important to have the neurologist involved from the time the patient’s admitted,” he says. “That’s the value of connecting the general hospitalist with neurologists.”

S. Andrew Josephson, MD, director of the neurohospitalist program at the University of California at San Francisco, says his colleagues are team players and improve patient care.

“Neurology consultations can be called very quickly, and a nice partnership can develop between internal medicine hospitalists and neurohospitalists to care for those patients who have those medical and neurologic problems,” he says.

He also says having a neurohospitalist on board can ease some of the tension.

“No longer if there’s a neurologic condition does a hospitalist have to think about, ‘Well, does this rise to the level of something that I need to get the neurologist to drive across the city to come see?’” he explains. “‘Or is this something we should try to manage ourselves?’”

Tom Collins is a freelance writer in South Florida.

References

- Bernhardt J, Dewey H, Thrift A, Collier J, Donnan G. A very early rehabilitation trial for stroke (AVERT): phase II safety and feasibility. Stroke. 2008;39;390-396.

- Giles MF, Albers GW, Amarenco P, et al. Early stroke risk and ABCD2 score performance in tissue- vs. time-defined TIA: a multicenter study. Neurology. 2011;77(13):1222-1228.

- Zinchuk AV, Flanagan EP, Tubridy NJ, Miller WA, McCullough LD. Attitudes of US medical trainees towards neurology education: “Neurophobia”—a global issue. BMC Med Educ. 2010;10:49.

Boston Marathon Bombing Calls Hospitalists to Duty

—James Hudspeth, MD, Boston Medical Center

—Dan Hale, MD, Floating Hospital for Children at Tufts Medical Center, Boston

Dan Hale, MD, a pediatric hospitalist at the Floating Hospital for Children at Tufts Medical Center in Boston, was doing discharge paperwork when he started getting text messages he couldn’t quite interpret.

“Are you OK?” “Do you need anything?” friends were asking him. Then he heard a page for all anesthesiologists to report to the OR. Immediately, he knew something terrible must have happened. He soon learned about the bombings at the Boston Marathon. He rushed to the pediatric ED to see how he could help.

James Hudspeth, MD, a hospitalist at Boston Medical Center, was meeting with the program director for internal medicine when he read a text message that bombs had just gone off near the finish line. They went online for local news coverage; soon thereafter, a cap on admissions was lifted. Dr. Hudspeth started expediting discharges to make room for what might be coming the hospital’s way.

Sushrut Jangi, MD, a hospitalist at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, was in a medical tent gathering information for an article on treating the health problems of marathoners that he was writing for The Boston Globe when he heard the blasts. Doctors and medical staff there worried about the possibility of a bomb in the tent, he said, but they were instructed to stay with their patients. Dr. Jangi had expected to work as a journalist for the day, but his doctoring skills were needed.

Hospitalists who were working in downtown Boston on April 15, when two bombs exploded 17 seconds apart, all experienced the tragedy in their own ways. But their accounts also resonate within some of the same themes.

They found themselves unsure of their roles, as most of the work inevitably fell to surgeons and trauma specialists. They described the importance of good leadership in times of crisis. And they say that hospitalists should be incorporated to a greater extent into disaster plans.

Dr. Jangi said that before the bombs went off, the medical tent was almost filled with runners who were “quite ill”—hypothermic and shaking, high sodium levels, disoriented. When the blasts occurred, the main instruction was, “Don’t leave your patients behind.” Those who were well enough were released from the tent, and the bomb-blast victims were essentially “whisked through.”

“We just kind of cleared the way and got them into ambulances as soon as possible. We just didn’t have the capacity to take care of such severe injury,” he said. “Why should we? We weren’t expecting a war zone.”

In the tent, Dr. Jangi wrote in an essay for the New England Journal of Medicine, “Many of us barely laid our hands on anyone. We had no trauma surgeons or supplies of blood products; tourniquets had already been applied; CPR had already been performed. Though some patients required bandages, sutures, and dressings, many of us watched these passing victims in a kind of idle horror, with no idea how to help.”

Dr. Hale was not involved in the treatment of bombing victims as the attending of record, but he said that he had a “bird’s-eye view” of the response in the pediatric ED. One child had shrapnel injuries and a ruptured tympanic membrane and was worked on by the team “professionally and efficiently,” Dr. Hale said.

When reports of a possible third bomb blast, at a library, came in, he saw the physician leaders go from team to team, making sure they were prepared.

“There were clear leaders communicating what to do,” said Dr. Hale, a firefighter in his hometown of Kittery in southern Maine. “As patients came in, it was extremely orderly. I saw very few clinical staff who were rattled.”

For his own part, in addition to his medical training, his training as a firefighter helped keep him calm, he said.

At Boston Medical Center, about a mile and a half from the blasts, the admissions that had been worked up over the course of the afternoon were essentially taken all at once so that there was room in the ED, said Dr. Hudspeth, who also does medical work in Haiti and was in New York on 9/11, though not as a doctor.

Focusing, he said, was “definitely a challenge.” Even though he had faith in hospital security, there was still “some notion of ‘You never know exactly what’s going to happen.’”

“You focus on the patient that’s in front of you. You focus on trying to solve the issues that are at hand. You deal with the logistical questions that come up between patients,” he said. “By and large, just put your nose to the grindstone.”

The doctors said that hospitalists had an unclear role in the response effort and hope to have their roles clarified so that they can better put to use their expertise in internal medicine. If hospitalists are monitoring general medical issues, that will help take some of the pressure off the trauma team.

“We know the [general] medicine stuff very well—that is our bread and butter,” said Dr. Hudspeth, who added that steps are being taken as part of Boston Medical Center’s post-response analysis to determine hospitalists’ role in future disaster responses.

They also said they felt fortunate that the bombings had occurred where they did, with so many hospitals close to the scene. It kept the system from becoming overwhelmed. Even so, “at some point, a disaster is so large that it would overwhelm any system, no matter how many resources were available,” Dr. Hale added.

Dr. Jangi said that he thinks his residency training helped him when he found himself having to provide care in a high-pressure situation in the medical tent.

“During residency, there are a lot of situations where you’re responsible for making a decision on your feet,” he said. “That’s a skill that you’re not really exposed to until you do it and that type of fast decision-making. I felt myself drawing on that. Not that I resuscitated anyone in the tent, but I felt more comfortable with uncertainty, with doing your duty in a situation of uncertainty. And I don’t know—maybe if I hadn’t gone through that, I would have just run out of there.”

He said the experience has helped make him more committed as a doctor.

“It makes it easier to remember what my duty is more, and it just gives me more empathy for suffering in general—I feel that very strongly,” he said. “It’s possible that this experience could have numbed me, but it didn’t. It’s made me more acute to the idea of people suffering.”

Tom Collins is a freelance writer in South Florida.

Reference

—James Hudspeth, MD, Boston Medical Center

—Dan Hale, MD, Floating Hospital for Children at Tufts Medical Center, Boston

Dan Hale, MD, a pediatric hospitalist at the Floating Hospital for Children at Tufts Medical Center in Boston, was doing discharge paperwork when he started getting text messages he couldn’t quite interpret.

“Are you OK?” “Do you need anything?” friends were asking him. Then he heard a page for all anesthesiologists to report to the OR. Immediately, he knew something terrible must have happened. He soon learned about the bombings at the Boston Marathon. He rushed to the pediatric ED to see how he could help.

James Hudspeth, MD, a hospitalist at Boston Medical Center, was meeting with the program director for internal medicine when he read a text message that bombs had just gone off near the finish line. They went online for local news coverage; soon thereafter, a cap on admissions was lifted. Dr. Hudspeth started expediting discharges to make room for what might be coming the hospital’s way.

Sushrut Jangi, MD, a hospitalist at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, was in a medical tent gathering information for an article on treating the health problems of marathoners that he was writing for The Boston Globe when he heard the blasts. Doctors and medical staff there worried about the possibility of a bomb in the tent, he said, but they were instructed to stay with their patients. Dr. Jangi had expected to work as a journalist for the day, but his doctoring skills were needed.

Hospitalists who were working in downtown Boston on April 15, when two bombs exploded 17 seconds apart, all experienced the tragedy in their own ways. But their accounts also resonate within some of the same themes.

They found themselves unsure of their roles, as most of the work inevitably fell to surgeons and trauma specialists. They described the importance of good leadership in times of crisis. And they say that hospitalists should be incorporated to a greater extent into disaster plans.

Dr. Jangi said that before the bombs went off, the medical tent was almost filled with runners who were “quite ill”—hypothermic and shaking, high sodium levels, disoriented. When the blasts occurred, the main instruction was, “Don’t leave your patients behind.” Those who were well enough were released from the tent, and the bomb-blast victims were essentially “whisked through.”

“We just kind of cleared the way and got them into ambulances as soon as possible. We just didn’t have the capacity to take care of such severe injury,” he said. “Why should we? We weren’t expecting a war zone.”

In the tent, Dr. Jangi wrote in an essay for the New England Journal of Medicine, “Many of us barely laid our hands on anyone. We had no trauma surgeons or supplies of blood products; tourniquets had already been applied; CPR had already been performed. Though some patients required bandages, sutures, and dressings, many of us watched these passing victims in a kind of idle horror, with no idea how to help.”

Dr. Hale was not involved in the treatment of bombing victims as the attending of record, but he said that he had a “bird’s-eye view” of the response in the pediatric ED. One child had shrapnel injuries and a ruptured tympanic membrane and was worked on by the team “professionally and efficiently,” Dr. Hale said.

When reports of a possible third bomb blast, at a library, came in, he saw the physician leaders go from team to team, making sure they were prepared.

“There were clear leaders communicating what to do,” said Dr. Hale, a firefighter in his hometown of Kittery in southern Maine. “As patients came in, it was extremely orderly. I saw very few clinical staff who were rattled.”

For his own part, in addition to his medical training, his training as a firefighter helped keep him calm, he said.

At Boston Medical Center, about a mile and a half from the blasts, the admissions that had been worked up over the course of the afternoon were essentially taken all at once so that there was room in the ED, said Dr. Hudspeth, who also does medical work in Haiti and was in New York on 9/11, though not as a doctor.

Focusing, he said, was “definitely a challenge.” Even though he had faith in hospital security, there was still “some notion of ‘You never know exactly what’s going to happen.’”

“You focus on the patient that’s in front of you. You focus on trying to solve the issues that are at hand. You deal with the logistical questions that come up between patients,” he said. “By and large, just put your nose to the grindstone.”

The doctors said that hospitalists had an unclear role in the response effort and hope to have their roles clarified so that they can better put to use their expertise in internal medicine. If hospitalists are monitoring general medical issues, that will help take some of the pressure off the trauma team.

“We know the [general] medicine stuff very well—that is our bread and butter,” said Dr. Hudspeth, who added that steps are being taken as part of Boston Medical Center’s post-response analysis to determine hospitalists’ role in future disaster responses.

They also said they felt fortunate that the bombings had occurred where they did, with so many hospitals close to the scene. It kept the system from becoming overwhelmed. Even so, “at some point, a disaster is so large that it would overwhelm any system, no matter how many resources were available,” Dr. Hale added.

Dr. Jangi said that he thinks his residency training helped him when he found himself having to provide care in a high-pressure situation in the medical tent.

“During residency, there are a lot of situations where you’re responsible for making a decision on your feet,” he said. “That’s a skill that you’re not really exposed to until you do it and that type of fast decision-making. I felt myself drawing on that. Not that I resuscitated anyone in the tent, but I felt more comfortable with uncertainty, with doing your duty in a situation of uncertainty. And I don’t know—maybe if I hadn’t gone through that, I would have just run out of there.”

He said the experience has helped make him more committed as a doctor.

“It makes it easier to remember what my duty is more, and it just gives me more empathy for suffering in general—I feel that very strongly,” he said. “It’s possible that this experience could have numbed me, but it didn’t. It’s made me more acute to the idea of people suffering.”

Tom Collins is a freelance writer in South Florida.

Reference

—James Hudspeth, MD, Boston Medical Center

—Dan Hale, MD, Floating Hospital for Children at Tufts Medical Center, Boston

Dan Hale, MD, a pediatric hospitalist at the Floating Hospital for Children at Tufts Medical Center in Boston, was doing discharge paperwork when he started getting text messages he couldn’t quite interpret.

“Are you OK?” “Do you need anything?” friends were asking him. Then he heard a page for all anesthesiologists to report to the OR. Immediately, he knew something terrible must have happened. He soon learned about the bombings at the Boston Marathon. He rushed to the pediatric ED to see how he could help.

James Hudspeth, MD, a hospitalist at Boston Medical Center, was meeting with the program director for internal medicine when he read a text message that bombs had just gone off near the finish line. They went online for local news coverage; soon thereafter, a cap on admissions was lifted. Dr. Hudspeth started expediting discharges to make room for what might be coming the hospital’s way.

Sushrut Jangi, MD, a hospitalist at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, was in a medical tent gathering information for an article on treating the health problems of marathoners that he was writing for The Boston Globe when he heard the blasts. Doctors and medical staff there worried about the possibility of a bomb in the tent, he said, but they were instructed to stay with their patients. Dr. Jangi had expected to work as a journalist for the day, but his doctoring skills were needed.

Hospitalists who were working in downtown Boston on April 15, when two bombs exploded 17 seconds apart, all experienced the tragedy in their own ways. But their accounts also resonate within some of the same themes.

They found themselves unsure of their roles, as most of the work inevitably fell to surgeons and trauma specialists. They described the importance of good leadership in times of crisis. And they say that hospitalists should be incorporated to a greater extent into disaster plans.

Dr. Jangi said that before the bombs went off, the medical tent was almost filled with runners who were “quite ill”—hypothermic and shaking, high sodium levels, disoriented. When the blasts occurred, the main instruction was, “Don’t leave your patients behind.” Those who were well enough were released from the tent, and the bomb-blast victims were essentially “whisked through.”

“We just kind of cleared the way and got them into ambulances as soon as possible. We just didn’t have the capacity to take care of such severe injury,” he said. “Why should we? We weren’t expecting a war zone.”

In the tent, Dr. Jangi wrote in an essay for the New England Journal of Medicine, “Many of us barely laid our hands on anyone. We had no trauma surgeons or supplies of blood products; tourniquets had already been applied; CPR had already been performed. Though some patients required bandages, sutures, and dressings, many of us watched these passing victims in a kind of idle horror, with no idea how to help.”

Dr. Hale was not involved in the treatment of bombing victims as the attending of record, but he said that he had a “bird’s-eye view” of the response in the pediatric ED. One child had shrapnel injuries and a ruptured tympanic membrane and was worked on by the team “professionally and efficiently,” Dr. Hale said.

When reports of a possible third bomb blast, at a library, came in, he saw the physician leaders go from team to team, making sure they were prepared.

“There were clear leaders communicating what to do,” said Dr. Hale, a firefighter in his hometown of Kittery in southern Maine. “As patients came in, it was extremely orderly. I saw very few clinical staff who were rattled.”

For his own part, in addition to his medical training, his training as a firefighter helped keep him calm, he said.

At Boston Medical Center, about a mile and a half from the blasts, the admissions that had been worked up over the course of the afternoon were essentially taken all at once so that there was room in the ED, said Dr. Hudspeth, who also does medical work in Haiti and was in New York on 9/11, though not as a doctor.

Focusing, he said, was “definitely a challenge.” Even though he had faith in hospital security, there was still “some notion of ‘You never know exactly what’s going to happen.’”

“You focus on the patient that’s in front of you. You focus on trying to solve the issues that are at hand. You deal with the logistical questions that come up between patients,” he said. “By and large, just put your nose to the grindstone.”

The doctors said that hospitalists had an unclear role in the response effort and hope to have their roles clarified so that they can better put to use their expertise in internal medicine. If hospitalists are monitoring general medical issues, that will help take some of the pressure off the trauma team.

“We know the [general] medicine stuff very well—that is our bread and butter,” said Dr. Hudspeth, who added that steps are being taken as part of Boston Medical Center’s post-response analysis to determine hospitalists’ role in future disaster responses.

They also said they felt fortunate that the bombings had occurred where they did, with so many hospitals close to the scene. It kept the system from becoming overwhelmed. Even so, “at some point, a disaster is so large that it would overwhelm any system, no matter how many resources were available,” Dr. Hale added.