User login

Müllerian anomalies: Operative considerations

Anterior discoid resection using a ‘squeeze’ technique

Rectosigmoid endometriosis has been estimated to affect between 4% and 37% of patients with endometriosis and is one of the most advanced and complex forms of the disease. Bowel endometriosis can be asymptomatic but often involves severe dysmenorrhea, dyspareunia, and a spectrum of bowel symptoms such as dyschezia, diarrhea, constipation, bloating, and rectal bleeding. Deep infiltrating rectovaginal endometriosis causes persistent or recurrent pain and is best treated by surgical removal of nodular lesions.

I have found that laparoscopic full-thickness disc resection (anterior discoid resection) with primary two-layer closure is often feasible and avoids the need for a complete bowel reanastomosis. It may not be an option in cases of multifocal rectal involvement (which may affect between one-quarter and one-third of patients with bowel endometriosis) or in cases involving large rectal nodules or luminal stenosis secondary to advanced fibrosis. In these cases, segmental bowel resection (low anterior resection) is often necessary. When anterior discoid resection is feasible, however, patients face significantly less morbidity with comparable outcomes.

Less morbidity

Preoperative evaluation is far from straightforward, and practices vary. Transvaginal ultrasonography is used for diagnosing rectal endometriosis in select centers in certain regions of the world, but there are important limitations; not only is it highly operator dependent, but its limited range does not allow for the detection of endometriosis higher in the sigmoid colon. Endorectal ultrasonography can be an excellent tool for more fully evaluating rectal wall involvement, but it does not usually allow for the evaluation of disease elsewhere in the pelvis.

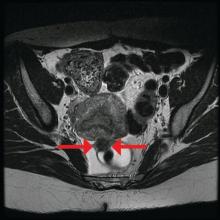

The preoperative tool we utilize most often along with clinical examination is MRI with vaginal and rectal contrast. MRI provides us with a superior anatomic perspective on the disease. Not only can we assess the depth of bowel wall infiltration and the distribution of the affected areas of the bowel, but we can see the bladder, the uterosacral ligaments, and how the uterus is situated relative to areas of disease. However, there are individualized limits to how high the contrast will travel, even with bowel preparation; disease that occurs significantly above the uterus often cannot be visualized as well as disease that occurs lower.

My general surgeon colleague and I have been working together for years, and we both are involved in counseling the patient suspected of having deep infiltrating disease. I typically talk with the patient about the probability of segmental resection based on my exam and preoperative MRI, and my colleague expands on this discussion with further explanation of the risks of bowel surgery.

Segmental resection has been associated with significant postoperative complications. In a single-center series of 436 laparoscopic colorectal resections for deep infiltrating endometriosis, rectovaginal and anastomotic fistula were among the most frequent postoperative complications (3.2% and 1.1%), along with transient urinary retention, which occurred in almost 20% (Surg Endosc. 2010 Jan;24:63-7).

Patients undergoing discoid resection for deep infiltrating endometriosis also had a significantly lower rate of temporary ileostomy (2.1% vs. 9.1%), a reduced rate of postoperative fever, and a reduced rate of gastrointestinal complications, mainly anastomotic leak or rectovaginal fistula (2.1% vs. 5.6%). There were no significant differences in the recurrence rate (13.8% vs. 11.5%).

A retrospective cohort study from our institution similarly showed decreased operative time, blood loss, hospital stay, and a lower rate of anastomotic strictures in patients who underwent laparoscopic anterior discoid resection between 2001 and 2009. The ADR group consistently had higher increments of improvement in bowel symptoms and dyspareunia, compared with patients who were selected to have segmental resection. Patients were followed for a mean of 41 months (JSLS. 2011;15[3]:331-8).

In general, there is agreement among surgeons that for consideration of discoid resection, nodule diameter should not exceed 3 cm, with a maximum of half of the bowel circumference and a maximum of 60% stenosis. I view these numbers as guiding principles, however, and not firm rules. Surgical decisions should be personalized based on the patient, the surgeon’s impression of the extent of the disease, and the ability to perform anterior discoid resection without compromising the rectal lumen with primary closure of the defect.

The technique

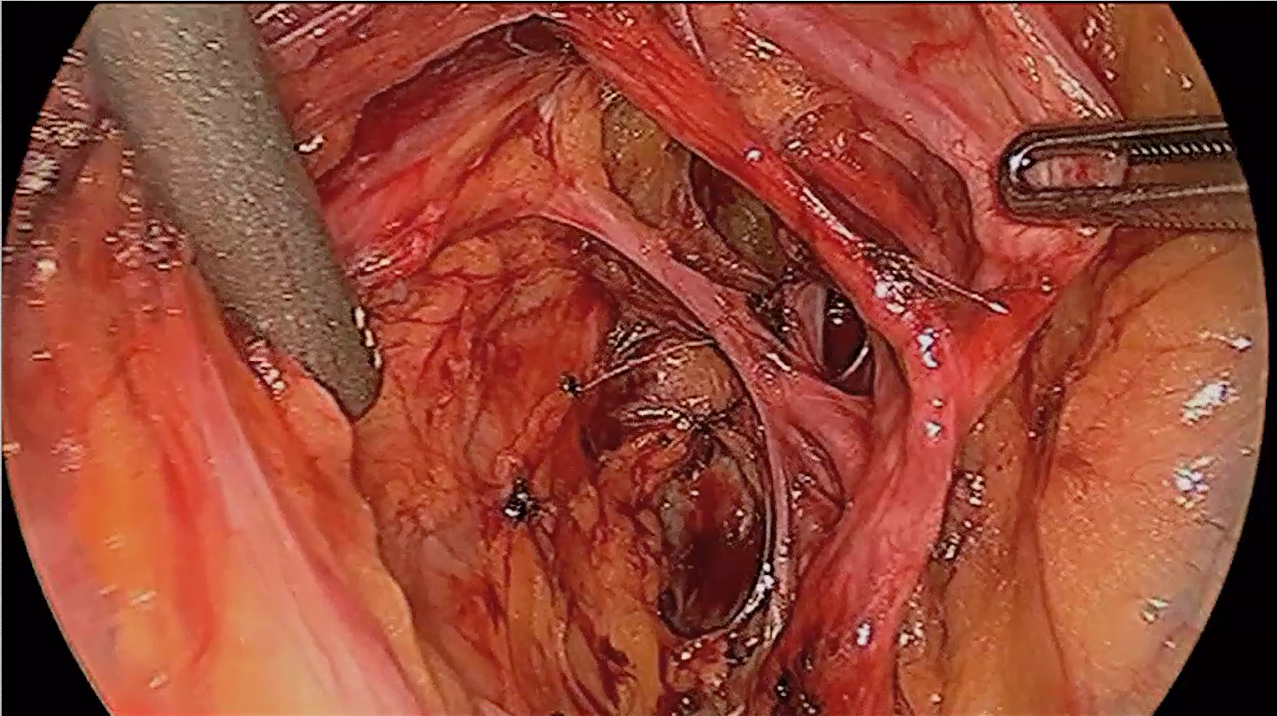

Rectosigmoid endometriotic nodules may present within the context of an obliterated posterior cul-de-sac, but the avascular pararectal space can be used to approach the nodules. Detailed knowledge of the avascular planes of this space, as well as the rectovaginal space, is crucial. Development of the rectovaginal space frees the bowel from its attachments to the posterior uterus and vagina. Judicious use of energized instruments in sharp dissection, and frequently sharp cold cutting, should be used near the bowel serosa to prevent thermal injury.

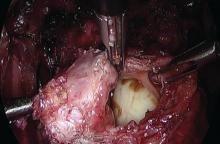

Presurgical imaging usually offers a good assessment of a nodule’s size and location, but intraoperatively, I typically use an atraumatic grasper to further assess size and contour and to determine if the nodule is suitable for discoid resection. If so, a suture is placed through the nodule to improve manipulation, and enucleation of the nodule itself is achieved through a “squeeze” technique in which an advanced bipolar device is used to circumscribe the lesion, dissecting the nodule as the device bounces off the thick endometriotic tissue.

The ENSEAL bipolar device (Ethicon, Somerville, N.J.) was designed as a vessel sealer, but because it will not cut through hard tissue as will other laparoscopic cutting devices, it serves as a useful tool for resecting endometriotic nodules while minimizing the removal of healthy rectal tissue. The device bounces off the nodule because it will avoid cutting through the thick tissue; in the process, it facilitates a fairly complete enucleation of the endometriotic nodule, starting with dissection until an intentional colotomy/enterotomy is made and followed by circumscription of the lesion once the rectum is entered.

Gentle traction and counter-traction increase the efficiency of dissection and minimize the amount of normal rectal tissue removed. Quick cutting with short bursts of energy allows for good hemostasis and minimizes thermal spread, which will maximize tissue healing from subsequent repair.

I then use a rectal probe as a template for repair. The probe is advanced underneath the defect between the distal and proximal portions, and the tissue is moved over the probe to ensure that the repair will be tension free. An ability to reapproximate the defect while keeping the probe in place indicates that the defect can be safely closed. (For a video presentation of the surgery, see www.surgeryu.com/leeobgyn.) If suturing is not feasible, the general surgeon is called to perform segmental resection.

The integrity of the repair is then thoroughly assessed with an air leak test. A bowel clamp is placed across the rectum and the pelvis is filled with sterile saline. Air is placed into the rectum with a rigid proctoscope while the operative field is inspected for evidence of an air leak.

Discoid resection may also be performed with a circular stapler. While this technique is faster than suturing, its use is limited by nodule size and has the potential to compromise complete excision of the nodule.

Dr. Lee is director of minimally invasive gynecologic surgery, Magee-Women’s Hospital of the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center.

Rectosigmoid endometriosis has been estimated to affect between 4% and 37% of patients with endometriosis and is one of the most advanced and complex forms of the disease. Bowel endometriosis can be asymptomatic but often involves severe dysmenorrhea, dyspareunia, and a spectrum of bowel symptoms such as dyschezia, diarrhea, constipation, bloating, and rectal bleeding. Deep infiltrating rectovaginal endometriosis causes persistent or recurrent pain and is best treated by surgical removal of nodular lesions.

I have found that laparoscopic full-thickness disc resection (anterior discoid resection) with primary two-layer closure is often feasible and avoids the need for a complete bowel reanastomosis. It may not be an option in cases of multifocal rectal involvement (which may affect between one-quarter and one-third of patients with bowel endometriosis) or in cases involving large rectal nodules or luminal stenosis secondary to advanced fibrosis. In these cases, segmental bowel resection (low anterior resection) is often necessary. When anterior discoid resection is feasible, however, patients face significantly less morbidity with comparable outcomes.

Less morbidity

Preoperative evaluation is far from straightforward, and practices vary. Transvaginal ultrasonography is used for diagnosing rectal endometriosis in select centers in certain regions of the world, but there are important limitations; not only is it highly operator dependent, but its limited range does not allow for the detection of endometriosis higher in the sigmoid colon. Endorectal ultrasonography can be an excellent tool for more fully evaluating rectal wall involvement, but it does not usually allow for the evaluation of disease elsewhere in the pelvis.

The preoperative tool we utilize most often along with clinical examination is MRI with vaginal and rectal contrast. MRI provides us with a superior anatomic perspective on the disease. Not only can we assess the depth of bowel wall infiltration and the distribution of the affected areas of the bowel, but we can see the bladder, the uterosacral ligaments, and how the uterus is situated relative to areas of disease. However, there are individualized limits to how high the contrast will travel, even with bowel preparation; disease that occurs significantly above the uterus often cannot be visualized as well as disease that occurs lower.

My general surgeon colleague and I have been working together for years, and we both are involved in counseling the patient suspected of having deep infiltrating disease. I typically talk with the patient about the probability of segmental resection based on my exam and preoperative MRI, and my colleague expands on this discussion with further explanation of the risks of bowel surgery.

Segmental resection has been associated with significant postoperative complications. In a single-center series of 436 laparoscopic colorectal resections for deep infiltrating endometriosis, rectovaginal and anastomotic fistula were among the most frequent postoperative complications (3.2% and 1.1%), along with transient urinary retention, which occurred in almost 20% (Surg Endosc. 2010 Jan;24:63-7).

Patients undergoing discoid resection for deep infiltrating endometriosis also had a significantly lower rate of temporary ileostomy (2.1% vs. 9.1%), a reduced rate of postoperative fever, and a reduced rate of gastrointestinal complications, mainly anastomotic leak or rectovaginal fistula (2.1% vs. 5.6%). There were no significant differences in the recurrence rate (13.8% vs. 11.5%).

A retrospective cohort study from our institution similarly showed decreased operative time, blood loss, hospital stay, and a lower rate of anastomotic strictures in patients who underwent laparoscopic anterior discoid resection between 2001 and 2009. The ADR group consistently had higher increments of improvement in bowel symptoms and dyspareunia, compared with patients who were selected to have segmental resection. Patients were followed for a mean of 41 months (JSLS. 2011;15[3]:331-8).

In general, there is agreement among surgeons that for consideration of discoid resection, nodule diameter should not exceed 3 cm, with a maximum of half of the bowel circumference and a maximum of 60% stenosis. I view these numbers as guiding principles, however, and not firm rules. Surgical decisions should be personalized based on the patient, the surgeon’s impression of the extent of the disease, and the ability to perform anterior discoid resection without compromising the rectal lumen with primary closure of the defect.

The technique

Rectosigmoid endometriotic nodules may present within the context of an obliterated posterior cul-de-sac, but the avascular pararectal space can be used to approach the nodules. Detailed knowledge of the avascular planes of this space, as well as the rectovaginal space, is crucial. Development of the rectovaginal space frees the bowel from its attachments to the posterior uterus and vagina. Judicious use of energized instruments in sharp dissection, and frequently sharp cold cutting, should be used near the bowel serosa to prevent thermal injury.

Presurgical imaging usually offers a good assessment of a nodule’s size and location, but intraoperatively, I typically use an atraumatic grasper to further assess size and contour and to determine if the nodule is suitable for discoid resection. If so, a suture is placed through the nodule to improve manipulation, and enucleation of the nodule itself is achieved through a “squeeze” technique in which an advanced bipolar device is used to circumscribe the lesion, dissecting the nodule as the device bounces off the thick endometriotic tissue.

The ENSEAL bipolar device (Ethicon, Somerville, N.J.) was designed as a vessel sealer, but because it will not cut through hard tissue as will other laparoscopic cutting devices, it serves as a useful tool for resecting endometriotic nodules while minimizing the removal of healthy rectal tissue. The device bounces off the nodule because it will avoid cutting through the thick tissue; in the process, it facilitates a fairly complete enucleation of the endometriotic nodule, starting with dissection until an intentional colotomy/enterotomy is made and followed by circumscription of the lesion once the rectum is entered.

Gentle traction and counter-traction increase the efficiency of dissection and minimize the amount of normal rectal tissue removed. Quick cutting with short bursts of energy allows for good hemostasis and minimizes thermal spread, which will maximize tissue healing from subsequent repair.

I then use a rectal probe as a template for repair. The probe is advanced underneath the defect between the distal and proximal portions, and the tissue is moved over the probe to ensure that the repair will be tension free. An ability to reapproximate the defect while keeping the probe in place indicates that the defect can be safely closed. (For a video presentation of the surgery, see www.surgeryu.com/leeobgyn.) If suturing is not feasible, the general surgeon is called to perform segmental resection.

The integrity of the repair is then thoroughly assessed with an air leak test. A bowel clamp is placed across the rectum and the pelvis is filled with sterile saline. Air is placed into the rectum with a rigid proctoscope while the operative field is inspected for evidence of an air leak.

Discoid resection may also be performed with a circular stapler. While this technique is faster than suturing, its use is limited by nodule size and has the potential to compromise complete excision of the nodule.

Dr. Lee is director of minimally invasive gynecologic surgery, Magee-Women’s Hospital of the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center.

Rectosigmoid endometriosis has been estimated to affect between 4% and 37% of patients with endometriosis and is one of the most advanced and complex forms of the disease. Bowel endometriosis can be asymptomatic but often involves severe dysmenorrhea, dyspareunia, and a spectrum of bowel symptoms such as dyschezia, diarrhea, constipation, bloating, and rectal bleeding. Deep infiltrating rectovaginal endometriosis causes persistent or recurrent pain and is best treated by surgical removal of nodular lesions.

I have found that laparoscopic full-thickness disc resection (anterior discoid resection) with primary two-layer closure is often feasible and avoids the need for a complete bowel reanastomosis. It may not be an option in cases of multifocal rectal involvement (which may affect between one-quarter and one-third of patients with bowel endometriosis) or in cases involving large rectal nodules or luminal stenosis secondary to advanced fibrosis. In these cases, segmental bowel resection (low anterior resection) is often necessary. When anterior discoid resection is feasible, however, patients face significantly less morbidity with comparable outcomes.

Less morbidity

Preoperative evaluation is far from straightforward, and practices vary. Transvaginal ultrasonography is used for diagnosing rectal endometriosis in select centers in certain regions of the world, but there are important limitations; not only is it highly operator dependent, but its limited range does not allow for the detection of endometriosis higher in the sigmoid colon. Endorectal ultrasonography can be an excellent tool for more fully evaluating rectal wall involvement, but it does not usually allow for the evaluation of disease elsewhere in the pelvis.

The preoperative tool we utilize most often along with clinical examination is MRI with vaginal and rectal contrast. MRI provides us with a superior anatomic perspective on the disease. Not only can we assess the depth of bowel wall infiltration and the distribution of the affected areas of the bowel, but we can see the bladder, the uterosacral ligaments, and how the uterus is situated relative to areas of disease. However, there are individualized limits to how high the contrast will travel, even with bowel preparation; disease that occurs significantly above the uterus often cannot be visualized as well as disease that occurs lower.

My general surgeon colleague and I have been working together for years, and we both are involved in counseling the patient suspected of having deep infiltrating disease. I typically talk with the patient about the probability of segmental resection based on my exam and preoperative MRI, and my colleague expands on this discussion with further explanation of the risks of bowel surgery.

Segmental resection has been associated with significant postoperative complications. In a single-center series of 436 laparoscopic colorectal resections for deep infiltrating endometriosis, rectovaginal and anastomotic fistula were among the most frequent postoperative complications (3.2% and 1.1%), along with transient urinary retention, which occurred in almost 20% (Surg Endosc. 2010 Jan;24:63-7).

Patients undergoing discoid resection for deep infiltrating endometriosis also had a significantly lower rate of temporary ileostomy (2.1% vs. 9.1%), a reduced rate of postoperative fever, and a reduced rate of gastrointestinal complications, mainly anastomotic leak or rectovaginal fistula (2.1% vs. 5.6%). There were no significant differences in the recurrence rate (13.8% vs. 11.5%).

A retrospective cohort study from our institution similarly showed decreased operative time, blood loss, hospital stay, and a lower rate of anastomotic strictures in patients who underwent laparoscopic anterior discoid resection between 2001 and 2009. The ADR group consistently had higher increments of improvement in bowel symptoms and dyspareunia, compared with patients who were selected to have segmental resection. Patients were followed for a mean of 41 months (JSLS. 2011;15[3]:331-8).

In general, there is agreement among surgeons that for consideration of discoid resection, nodule diameter should not exceed 3 cm, with a maximum of half of the bowel circumference and a maximum of 60% stenosis. I view these numbers as guiding principles, however, and not firm rules. Surgical decisions should be personalized based on the patient, the surgeon’s impression of the extent of the disease, and the ability to perform anterior discoid resection without compromising the rectal lumen with primary closure of the defect.

The technique

Rectosigmoid endometriotic nodules may present within the context of an obliterated posterior cul-de-sac, but the avascular pararectal space can be used to approach the nodules. Detailed knowledge of the avascular planes of this space, as well as the rectovaginal space, is crucial. Development of the rectovaginal space frees the bowel from its attachments to the posterior uterus and vagina. Judicious use of energized instruments in sharp dissection, and frequently sharp cold cutting, should be used near the bowel serosa to prevent thermal injury.

Presurgical imaging usually offers a good assessment of a nodule’s size and location, but intraoperatively, I typically use an atraumatic grasper to further assess size and contour and to determine if the nodule is suitable for discoid resection. If so, a suture is placed through the nodule to improve manipulation, and enucleation of the nodule itself is achieved through a “squeeze” technique in which an advanced bipolar device is used to circumscribe the lesion, dissecting the nodule as the device bounces off the thick endometriotic tissue.

The ENSEAL bipolar device (Ethicon, Somerville, N.J.) was designed as a vessel sealer, but because it will not cut through hard tissue as will other laparoscopic cutting devices, it serves as a useful tool for resecting endometriotic nodules while minimizing the removal of healthy rectal tissue. The device bounces off the nodule because it will avoid cutting through the thick tissue; in the process, it facilitates a fairly complete enucleation of the endometriotic nodule, starting with dissection until an intentional colotomy/enterotomy is made and followed by circumscription of the lesion once the rectum is entered.

Gentle traction and counter-traction increase the efficiency of dissection and minimize the amount of normal rectal tissue removed. Quick cutting with short bursts of energy allows for good hemostasis and minimizes thermal spread, which will maximize tissue healing from subsequent repair.

I then use a rectal probe as a template for repair. The probe is advanced underneath the defect between the distal and proximal portions, and the tissue is moved over the probe to ensure that the repair will be tension free. An ability to reapproximate the defect while keeping the probe in place indicates that the defect can be safely closed. (For a video presentation of the surgery, see www.surgeryu.com/leeobgyn.) If suturing is not feasible, the general surgeon is called to perform segmental resection.

The integrity of the repair is then thoroughly assessed with an air leak test. A bowel clamp is placed across the rectum and the pelvis is filled with sterile saline. Air is placed into the rectum with a rigid proctoscope while the operative field is inspected for evidence of an air leak.

Discoid resection may also be performed with a circular stapler. While this technique is faster than suturing, its use is limited by nodule size and has the potential to compromise complete excision of the nodule.

Dr. Lee is director of minimally invasive gynecologic surgery, Magee-Women’s Hospital of the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center.

Uterine artery ligation: Advanced techniques and considerations for the difficult laparoscopic hysterectomy

For more videos from the Society of Gynecologic Surgeons, click here

Visit the Society of Gynecologic Surgeons online: sgsonline.org

Related articles:

- Cervical injection of methylene blue for identification of sentinel lymph nodes in cervical cancer

- Misplaced hysteroscopic sterilization micro-insert in the peritoneal cavity: A corpus alienum

- Laparoscopic cystectomy for large, bilateral ovarian dermoids

- Small bowel surgery for the benign gynecologist

- A novel approach to overcoming cervical stenosis and false passages

For more videos from the Society of Gynecologic Surgeons, click here

Visit the Society of Gynecologic Surgeons online: sgsonline.org

Related articles:

- Cervical injection of methylene blue for identification of sentinel lymph nodes in cervical cancer

- Misplaced hysteroscopic sterilization micro-insert in the peritoneal cavity: A corpus alienum

- Laparoscopic cystectomy for large, bilateral ovarian dermoids

- Small bowel surgery for the benign gynecologist

- A novel approach to overcoming cervical stenosis and false passages

For more videos from the Society of Gynecologic Surgeons, click here

Visit the Society of Gynecologic Surgeons online: sgsonline.org

Related articles:

- Cervical injection of methylene blue for identification of sentinel lymph nodes in cervical cancer

- Misplaced hysteroscopic sterilization micro-insert in the peritoneal cavity: A corpus alienum

- Laparoscopic cystectomy for large, bilateral ovarian dermoids

- Small bowel surgery for the benign gynecologist

- A novel approach to overcoming cervical stenosis and false passages

This video is brought to you by ![]()