User login

Aspirin alone preferred antithrombotic strategy after TAVI

Aspirin alone after transcatheter aortic valve implantation (TAVI) significantly reduced bleeding, compared with aspirin plus clopidogrel, without increasing thromboembolic events, in the latest results from the POPular TAVI study.

“Physicians can easily and safely reduce rate of bleeding by omitting clopidogrel after TAVI,” lead author, Jorn Brouwer, MD, St Antonius Hospital, Nieuwegein, the Netherlands, said.

“Aspirin alone should be used in patients undergoing TAVI who are not on oral anticoagulants and have not recently undergone coronary stenting,” he concluded.

Senior author, Jurriën ten Berg, MD, PhD, also from St Antonius Hospital, said in an interview: “I think we can say for TAVI patients, when it comes to antithrombotic therapy, less is definitely more.”

“This is a major change to clinical practice, with current guidelines recommending 3-6 months of dual antiplatelet therapy after a TAVI procedure,” he added. “We expected that these guidelines will change after our results.”

These latest results from POPular TAVI were presented at the virtual European Society of Cardiology Congress 2020 and simultaneously published online in The New England Journal of Medicine.

The trial was conducted in two cohorts of patients undergoing TAVI. The results from cohort B – in patients who were already taking an anticoagulant for another indication – were reported earlier this year and showed no benefit of adding clopidogrel and an increase in bleeding. Now the current results in cohort A – patients undergoing TAVI who do not have an established indication for long-term anticoagulation – show similar results, with aspirin alone preferred over aspirin plus clopidogrel.

Dr. ten Berg explained that the recommendation for dual antiplatelet therapy (DAPT) was adopted mainly because this has been shown to be beneficial in patients undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) with stenting; it was thought the same benefits would be seen in TAVI, which also uses a stent-based delivery system.

“However, TAVI patients are a different population – they are generally much older than PCI patients, with an average age of 80 plus, and they have many more comorbidities, so they are much higher bleeding risk,” Dr. ten Berg explained. “In addition, the catheters used for TAVI are larger than those used for PCI, forcing the femoral route to be employed, and both of these factors increases bleeding risk.”

“We saw that, in the trial, patients on dual antiplatelet therapy had a much greater rate of major bleeding and the addition of clopidogrel did not reduce the risk of major thrombotic events,” such as stroke, myocardial infarction (MI), or cardiovascular (CV) death.

Given that the TAVI procedure is associated with an increase in stroke in the immediate few days after the procedure, it would seem logical that increased antiplatelet therapy would be beneficial in reducing this, Dr. ten Berg noted.

“But this is not what we are seeing,” he said. “The stroke incidence was similar in the two groups in POPular TAVI. This suggests that the strokes may not be platelet mediated. They might be caused by another mechanism, such as dislodgement of calcium from the valve or tissue from the aorta.”

For the current part of the study, 690 patients who were undergoing TAVI and did not have an indication for long-term anticoagulation were randomly assigned to receive aspirin alone or aspirin plus clopidogrel for 3 months.

The two primary outcomes were all bleeding (including minor, major, and life-threatening or disabling bleeding) and non–procedure-related bleeding over a period of 12 months. Most bleeding at the TAVI puncture site was counted as not procedure related.

Results showed that a bleeding event occurred in 15.1% of patients receiving aspirin alone and 26.6% of those receiving aspirin plus clopidogrel (risk ratio, 0.57; P = .001). Non–procedure-related bleeding occurred 15.1% of patients receiving aspirin alone vs 24.9% of those receiving aspirin plus clopidogrel (risk ratio, 0.61; P = .005). Major, life-threatening, or disabling bleeding occurred in 5.1% of the aspirin-alone group versus 10.8% of those in the aspirin plus clopidogrel group.

Two secondary outcomes included thromboembolic events. The secondary composite one endpoint of death from cardiovascular causes, non–procedure-related bleeding, stroke, or MI at 1 year occurred in 23.0% of those receiving aspirin alone and in 31.1% of those receiving aspirin plus clopidogrel (difference, −8.2 percentage points; P for noninferiority < .001; risk ratio, 0.74; P for superiority = .04).

The secondary composite two endpoint of death from cardiovascular causes, ischemic stroke, or MI at 1 year occurred in 9.7% of the aspirin-alone group versus 9.9% of the dual-antiplatelet group (difference, −0.2 percentage points; P for noninferiority = .004; risk ratio, 0.98; P for superiority = .93).

Dr. ten Berg pointed out that the trial was not strictly powered to look at thrombotic events, but he added: “There was no hint of an increase in the aspirin-alone group and there was quite a high event rate, so we should have seen something if it was there.”

The group has also performed a meta-analysis of these results, with some previous smaller studies also comparing aspirin and DAPT in TAVI which again showed no reduction in thrombotic events with dual-antiplatelet therapy.

Dr. ten Berg noted that the trial included all-comer TAVI patients. “The overall risk was quite a low [STS score, 2.5]. This is a reflection of the typical TAVI patient we are seeing but I would say our results apply to patients of all risk.”

Simplifies and clarifies

Discussant of the trial at the ESC Hotline session, Anna Sonia Petronio, MD, Azienda Ospedaliero-Universitaria Pisana, Pisa, Italy, said, “This was an excellent and essential study that simplifies and clarifies aspects of TAVI treatment and needs to change the guidelines.”

“These results will have a large impact on clinical practice in this elderly population,” she said. But she added that more data are needed for younger patients and more complicated cases, such as valve-in-valve and bicuspid valves.

Commenting on the results, Robert Bonow, MD, Northwestern University, Chicago, said, “The optimal antithrombotic management of patients undergoing TAVI who do not otherwise have an indication for anticoagulation [such as atrial fibrillation] has been uncertain and debatable. Aspirin plus clopidogrel for 3-6 months has been the standard, based on the experience with coronary stents.”

“Thus, the current results of cohort A of the POPular TAVI trial showing significant reduction in bleeding events with aspirin alone compared to DAPT for 3 months, with no difference in ischemic events, are important observations,” he said. “It is noteworthy that most of the bleeding events occurred in the first 30 days.

“This is a relatively small randomized trial, so whether these results will be practice changing will depend on confirmation by additional studies, but it is reassuring to know that patients at higher risk for bleeding would appear to do well with low-dose aspirin alone after TAVI,” Dr. Bonow added.

“These results complete the circle in terms of antithrombotic therapy after TAVI,” commented Michael Reardon, MD, Houston Methodist DeBakey Heart & Vascular Institute, Texas.

“I would add two caveats: First is that most of the difference in the primary endpoint occurs in the first month and levels out between the groups after that,” Dr. Reardon said. “Second is that this does not address the issue of leaflet thickening and immobility.”

Ashish Pershad, MD, Banner – University Medicine Heart Institute, Phoenix, added: “This trial answers a very important question and shows dual-antiplatelet therapy is hazardous in TAVI patients. Clopidogrel is not needed.”

Dr. Pershad says he still wonders about patients who receive very small valves who may have a higher risk for valve-induced thrombosis. “While there were some of these patients in the trial, the numbers were small, so we need more data on this group,” he commented.

“But for bread-and-butter TAVI, aspirin alone is the best choice, and the previous results showed, for patients already taking oral anticoagulation, no additional antithrombotic therapy is required,” Dr. Pershad concluded. “This is a big deal and will change the way we treat patients.”

The POPular trial was supported by the Netherlands Organization for Health Research and Development. Brouwer reports no disclosures.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

Aspirin alone after transcatheter aortic valve implantation (TAVI) significantly reduced bleeding, compared with aspirin plus clopidogrel, without increasing thromboembolic events, in the latest results from the POPular TAVI study.

“Physicians can easily and safely reduce rate of bleeding by omitting clopidogrel after TAVI,” lead author, Jorn Brouwer, MD, St Antonius Hospital, Nieuwegein, the Netherlands, said.

“Aspirin alone should be used in patients undergoing TAVI who are not on oral anticoagulants and have not recently undergone coronary stenting,” he concluded.

Senior author, Jurriën ten Berg, MD, PhD, also from St Antonius Hospital, said in an interview: “I think we can say for TAVI patients, when it comes to antithrombotic therapy, less is definitely more.”

“This is a major change to clinical practice, with current guidelines recommending 3-6 months of dual antiplatelet therapy after a TAVI procedure,” he added. “We expected that these guidelines will change after our results.”

These latest results from POPular TAVI were presented at the virtual European Society of Cardiology Congress 2020 and simultaneously published online in The New England Journal of Medicine.

The trial was conducted in two cohorts of patients undergoing TAVI. The results from cohort B – in patients who were already taking an anticoagulant for another indication – were reported earlier this year and showed no benefit of adding clopidogrel and an increase in bleeding. Now the current results in cohort A – patients undergoing TAVI who do not have an established indication for long-term anticoagulation – show similar results, with aspirin alone preferred over aspirin plus clopidogrel.

Dr. ten Berg explained that the recommendation for dual antiplatelet therapy (DAPT) was adopted mainly because this has been shown to be beneficial in patients undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) with stenting; it was thought the same benefits would be seen in TAVI, which also uses a stent-based delivery system.

“However, TAVI patients are a different population – they are generally much older than PCI patients, with an average age of 80 plus, and they have many more comorbidities, so they are much higher bleeding risk,” Dr. ten Berg explained. “In addition, the catheters used for TAVI are larger than those used for PCI, forcing the femoral route to be employed, and both of these factors increases bleeding risk.”

“We saw that, in the trial, patients on dual antiplatelet therapy had a much greater rate of major bleeding and the addition of clopidogrel did not reduce the risk of major thrombotic events,” such as stroke, myocardial infarction (MI), or cardiovascular (CV) death.

Given that the TAVI procedure is associated with an increase in stroke in the immediate few days after the procedure, it would seem logical that increased antiplatelet therapy would be beneficial in reducing this, Dr. ten Berg noted.

“But this is not what we are seeing,” he said. “The stroke incidence was similar in the two groups in POPular TAVI. This suggests that the strokes may not be platelet mediated. They might be caused by another mechanism, such as dislodgement of calcium from the valve or tissue from the aorta.”

For the current part of the study, 690 patients who were undergoing TAVI and did not have an indication for long-term anticoagulation were randomly assigned to receive aspirin alone or aspirin plus clopidogrel for 3 months.

The two primary outcomes were all bleeding (including minor, major, and life-threatening or disabling bleeding) and non–procedure-related bleeding over a period of 12 months. Most bleeding at the TAVI puncture site was counted as not procedure related.

Results showed that a bleeding event occurred in 15.1% of patients receiving aspirin alone and 26.6% of those receiving aspirin plus clopidogrel (risk ratio, 0.57; P = .001). Non–procedure-related bleeding occurred 15.1% of patients receiving aspirin alone vs 24.9% of those receiving aspirin plus clopidogrel (risk ratio, 0.61; P = .005). Major, life-threatening, or disabling bleeding occurred in 5.1% of the aspirin-alone group versus 10.8% of those in the aspirin plus clopidogrel group.

Two secondary outcomes included thromboembolic events. The secondary composite one endpoint of death from cardiovascular causes, non–procedure-related bleeding, stroke, or MI at 1 year occurred in 23.0% of those receiving aspirin alone and in 31.1% of those receiving aspirin plus clopidogrel (difference, −8.2 percentage points; P for noninferiority < .001; risk ratio, 0.74; P for superiority = .04).

The secondary composite two endpoint of death from cardiovascular causes, ischemic stroke, or MI at 1 year occurred in 9.7% of the aspirin-alone group versus 9.9% of the dual-antiplatelet group (difference, −0.2 percentage points; P for noninferiority = .004; risk ratio, 0.98; P for superiority = .93).

Dr. ten Berg pointed out that the trial was not strictly powered to look at thrombotic events, but he added: “There was no hint of an increase in the aspirin-alone group and there was quite a high event rate, so we should have seen something if it was there.”

The group has also performed a meta-analysis of these results, with some previous smaller studies also comparing aspirin and DAPT in TAVI which again showed no reduction in thrombotic events with dual-antiplatelet therapy.

Dr. ten Berg noted that the trial included all-comer TAVI patients. “The overall risk was quite a low [STS score, 2.5]. This is a reflection of the typical TAVI patient we are seeing but I would say our results apply to patients of all risk.”

Simplifies and clarifies

Discussant of the trial at the ESC Hotline session, Anna Sonia Petronio, MD, Azienda Ospedaliero-Universitaria Pisana, Pisa, Italy, said, “This was an excellent and essential study that simplifies and clarifies aspects of TAVI treatment and needs to change the guidelines.”

“These results will have a large impact on clinical practice in this elderly population,” she said. But she added that more data are needed for younger patients and more complicated cases, such as valve-in-valve and bicuspid valves.

Commenting on the results, Robert Bonow, MD, Northwestern University, Chicago, said, “The optimal antithrombotic management of patients undergoing TAVI who do not otherwise have an indication for anticoagulation [such as atrial fibrillation] has been uncertain and debatable. Aspirin plus clopidogrel for 3-6 months has been the standard, based on the experience with coronary stents.”

“Thus, the current results of cohort A of the POPular TAVI trial showing significant reduction in bleeding events with aspirin alone compared to DAPT for 3 months, with no difference in ischemic events, are important observations,” he said. “It is noteworthy that most of the bleeding events occurred in the first 30 days.

“This is a relatively small randomized trial, so whether these results will be practice changing will depend on confirmation by additional studies, but it is reassuring to know that patients at higher risk for bleeding would appear to do well with low-dose aspirin alone after TAVI,” Dr. Bonow added.

“These results complete the circle in terms of antithrombotic therapy after TAVI,” commented Michael Reardon, MD, Houston Methodist DeBakey Heart & Vascular Institute, Texas.

“I would add two caveats: First is that most of the difference in the primary endpoint occurs in the first month and levels out between the groups after that,” Dr. Reardon said. “Second is that this does not address the issue of leaflet thickening and immobility.”

Ashish Pershad, MD, Banner – University Medicine Heart Institute, Phoenix, added: “This trial answers a very important question and shows dual-antiplatelet therapy is hazardous in TAVI patients. Clopidogrel is not needed.”

Dr. Pershad says he still wonders about patients who receive very small valves who may have a higher risk for valve-induced thrombosis. “While there were some of these patients in the trial, the numbers were small, so we need more data on this group,” he commented.

“But for bread-and-butter TAVI, aspirin alone is the best choice, and the previous results showed, for patients already taking oral anticoagulation, no additional antithrombotic therapy is required,” Dr. Pershad concluded. “This is a big deal and will change the way we treat patients.”

The POPular trial was supported by the Netherlands Organization for Health Research and Development. Brouwer reports no disclosures.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

Aspirin alone after transcatheter aortic valve implantation (TAVI) significantly reduced bleeding, compared with aspirin plus clopidogrel, without increasing thromboembolic events, in the latest results from the POPular TAVI study.

“Physicians can easily and safely reduce rate of bleeding by omitting clopidogrel after TAVI,” lead author, Jorn Brouwer, MD, St Antonius Hospital, Nieuwegein, the Netherlands, said.

“Aspirin alone should be used in patients undergoing TAVI who are not on oral anticoagulants and have not recently undergone coronary stenting,” he concluded.

Senior author, Jurriën ten Berg, MD, PhD, also from St Antonius Hospital, said in an interview: “I think we can say for TAVI patients, when it comes to antithrombotic therapy, less is definitely more.”

“This is a major change to clinical practice, with current guidelines recommending 3-6 months of dual antiplatelet therapy after a TAVI procedure,” he added. “We expected that these guidelines will change after our results.”

These latest results from POPular TAVI were presented at the virtual European Society of Cardiology Congress 2020 and simultaneously published online in The New England Journal of Medicine.

The trial was conducted in two cohorts of patients undergoing TAVI. The results from cohort B – in patients who were already taking an anticoagulant for another indication – were reported earlier this year and showed no benefit of adding clopidogrel and an increase in bleeding. Now the current results in cohort A – patients undergoing TAVI who do not have an established indication for long-term anticoagulation – show similar results, with aspirin alone preferred over aspirin plus clopidogrel.

Dr. ten Berg explained that the recommendation for dual antiplatelet therapy (DAPT) was adopted mainly because this has been shown to be beneficial in patients undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) with stenting; it was thought the same benefits would be seen in TAVI, which also uses a stent-based delivery system.

“However, TAVI patients are a different population – they are generally much older than PCI patients, with an average age of 80 plus, and they have many more comorbidities, so they are much higher bleeding risk,” Dr. ten Berg explained. “In addition, the catheters used for TAVI are larger than those used for PCI, forcing the femoral route to be employed, and both of these factors increases bleeding risk.”

“We saw that, in the trial, patients on dual antiplatelet therapy had a much greater rate of major bleeding and the addition of clopidogrel did not reduce the risk of major thrombotic events,” such as stroke, myocardial infarction (MI), or cardiovascular (CV) death.

Given that the TAVI procedure is associated with an increase in stroke in the immediate few days after the procedure, it would seem logical that increased antiplatelet therapy would be beneficial in reducing this, Dr. ten Berg noted.

“But this is not what we are seeing,” he said. “The stroke incidence was similar in the two groups in POPular TAVI. This suggests that the strokes may not be platelet mediated. They might be caused by another mechanism, such as dislodgement of calcium from the valve or tissue from the aorta.”

For the current part of the study, 690 patients who were undergoing TAVI and did not have an indication for long-term anticoagulation were randomly assigned to receive aspirin alone or aspirin plus clopidogrel for 3 months.

The two primary outcomes were all bleeding (including minor, major, and life-threatening or disabling bleeding) and non–procedure-related bleeding over a period of 12 months. Most bleeding at the TAVI puncture site was counted as not procedure related.

Results showed that a bleeding event occurred in 15.1% of patients receiving aspirin alone and 26.6% of those receiving aspirin plus clopidogrel (risk ratio, 0.57; P = .001). Non–procedure-related bleeding occurred 15.1% of patients receiving aspirin alone vs 24.9% of those receiving aspirin plus clopidogrel (risk ratio, 0.61; P = .005). Major, life-threatening, or disabling bleeding occurred in 5.1% of the aspirin-alone group versus 10.8% of those in the aspirin plus clopidogrel group.

Two secondary outcomes included thromboembolic events. The secondary composite one endpoint of death from cardiovascular causes, non–procedure-related bleeding, stroke, or MI at 1 year occurred in 23.0% of those receiving aspirin alone and in 31.1% of those receiving aspirin plus clopidogrel (difference, −8.2 percentage points; P for noninferiority < .001; risk ratio, 0.74; P for superiority = .04).

The secondary composite two endpoint of death from cardiovascular causes, ischemic stroke, or MI at 1 year occurred in 9.7% of the aspirin-alone group versus 9.9% of the dual-antiplatelet group (difference, −0.2 percentage points; P for noninferiority = .004; risk ratio, 0.98; P for superiority = .93).

Dr. ten Berg pointed out that the trial was not strictly powered to look at thrombotic events, but he added: “There was no hint of an increase in the aspirin-alone group and there was quite a high event rate, so we should have seen something if it was there.”

The group has also performed a meta-analysis of these results, with some previous smaller studies also comparing aspirin and DAPT in TAVI which again showed no reduction in thrombotic events with dual-antiplatelet therapy.

Dr. ten Berg noted that the trial included all-comer TAVI patients. “The overall risk was quite a low [STS score, 2.5]. This is a reflection of the typical TAVI patient we are seeing but I would say our results apply to patients of all risk.”

Simplifies and clarifies

Discussant of the trial at the ESC Hotline session, Anna Sonia Petronio, MD, Azienda Ospedaliero-Universitaria Pisana, Pisa, Italy, said, “This was an excellent and essential study that simplifies and clarifies aspects of TAVI treatment and needs to change the guidelines.”

“These results will have a large impact on clinical practice in this elderly population,” she said. But she added that more data are needed for younger patients and more complicated cases, such as valve-in-valve and bicuspid valves.

Commenting on the results, Robert Bonow, MD, Northwestern University, Chicago, said, “The optimal antithrombotic management of patients undergoing TAVI who do not otherwise have an indication for anticoagulation [such as atrial fibrillation] has been uncertain and debatable. Aspirin plus clopidogrel for 3-6 months has been the standard, based on the experience with coronary stents.”

“Thus, the current results of cohort A of the POPular TAVI trial showing significant reduction in bleeding events with aspirin alone compared to DAPT for 3 months, with no difference in ischemic events, are important observations,” he said. “It is noteworthy that most of the bleeding events occurred in the first 30 days.

“This is a relatively small randomized trial, so whether these results will be practice changing will depend on confirmation by additional studies, but it is reassuring to know that patients at higher risk for bleeding would appear to do well with low-dose aspirin alone after TAVI,” Dr. Bonow added.

“These results complete the circle in terms of antithrombotic therapy after TAVI,” commented Michael Reardon, MD, Houston Methodist DeBakey Heart & Vascular Institute, Texas.

“I would add two caveats: First is that most of the difference in the primary endpoint occurs in the first month and levels out between the groups after that,” Dr. Reardon said. “Second is that this does not address the issue of leaflet thickening and immobility.”

Ashish Pershad, MD, Banner – University Medicine Heart Institute, Phoenix, added: “This trial answers a very important question and shows dual-antiplatelet therapy is hazardous in TAVI patients. Clopidogrel is not needed.”

Dr. Pershad says he still wonders about patients who receive very small valves who may have a higher risk for valve-induced thrombosis. “While there were some of these patients in the trial, the numbers were small, so we need more data on this group,” he commented.

“But for bread-and-butter TAVI, aspirin alone is the best choice, and the previous results showed, for patients already taking oral anticoagulation, no additional antithrombotic therapy is required,” Dr. Pershad concluded. “This is a big deal and will change the way we treat patients.”

The POPular trial was supported by the Netherlands Organization for Health Research and Development. Brouwer reports no disclosures.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

ADHD and dyslexia may affect evaluation of concussion

, a new study shows.

“Our results suggest kids with certain learning disorders may respond differently to concussion tests, and this needs to be taken into account when advising on recovery times and when they can return to sport,” said lead author Mathew Stokes, MD. Dr. Stokes is assistant professor of pediatrics and neurology/neurotherapeutics at the University of Texas–Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas.

The study was presented at the American Academy of Neurology Sports Concussion Virtual Conference, held online July 31 to Aug. 1.

Learning disorders affected scores

The researchers analyzed data from participants aged 10-18 years who were enrolled in the North Texas Concussion Registry (ConTex). Participants had been diagnosed with a concussion that was sustained within 30 days of enrollment. The researchers investigated whether there were differences between patients who had no history of learning disorders and those with a history of dyslexia and/or ADD/ADHD with regard to results of clinical testing following concussion.

Of the 1,298 individuals in the study, 58 had been diagnosed with dyslexia, 158 had been diagnosed with ADD/ADHD, and 35 had been diagnosed with both conditions. There was no difference in age, time since injury, or history of concussion between those with learning disorders and those without, but there were more male patients in the ADD/ADHD group.

Results showed that in the dyslexia group, mean time was slower (P = .011), and there was an increase in error scores on the King-Devick (KD) test (P = .028). That test assesses eye movements and involves the rapid naming of numbers that are spaced differently. In addition, those with ADD/ADHD had significantly higher impulse control scores (P = .007) on the ImPACT series of tests, which are commonly used in the evaluation of concussion. Participants with both dyslexia and ADHD demonstrated slower KD times (P = .009) and had higher depression scores and anxiety scores.

Dr. Stokes noted that a limiting factor of the study was that baseline scores were not available. “It is possible that kids with ADD have less impulse control even at baseline, and this would need to be taken into account,” he said. “You may perhaps also expect someone with dyslexia to have a worse score on the KD tests, so we need more data on how these scores are affected from baseline in these individuals. But our results show that when evaluating kids pre- or post concussion, it is important to know about learning disorders, as this will affect how we interpret the data.”

At 3-month follow-up, there were no longer significant differences in anxiety and depression scores for those with and those without learning disorders. “This suggests anxiety and depression may well be worse temporarily after concussion for those with ADD/ADHD but gets better with time,” Dr. Stokes said.

Follow-up data were not available for the other cognitive tests.

Are recovery times longer?

Asked whether young people with these learning disorders needed a longer time to recover after concussion, Dr. Stokes said: “That is a million-dollar question. Studies so far on this have shown conflicting results. Our results add to a growing body of literature on this.” He stressed that it is important to include anxiety and depression scores on both baseline and postconcussion tests. “People don’t tend to think of these symptoms as being associated with concussion, but they are actually very prominent in this situation,” he noted. “Our results suggest that individuals with ADHD may be more prone to anxiety and depression, and a blow to the head may tip them more into these symptoms.”

Discussing the study at a virtual press conference as part of the AAN Sports Concussion meeting, the codirector of the meeting, David Dodick, MD, Mayo Clinic, Scottsdale, Ariz., said: “This is a very interesting and important study which suggests there are differences between adolescents with a history of dyslexia/ADHD and those without these conditions in performance in concussion tests. Understanding the differences in these groups will help health care providers in evaluating these athletes and assisting in counseling them and their families with regard to their risk of injury.

“It is important to recognize that athletes with ADHD, whether or not they are on medication, may take longer to recover from a concussion,” Dr. Dodick added. They also exhibit greater reductions in cognitive skills and visual motor speed regarding hand-eye coordination, he said. There is an increase in the severity of symptoms. “Symptoms that exist in both groups tend to more severe in those individuals with ADHD,” he noted.

“Ascertaining the presence or absence of ADHD or dyslexia in those who are participating in sport is important, especially when trying to interpret the results of baseline testing, the results of postinjury testing, decisions on when to return to play, and assessing for individuals and their families the risk of long-term repeat concussions and adverse outcomes,” he concluded.

The other codirector of the AAN meeting, Brian Hainline, MD, chief medical officer of the National Collegiate Athletic Association, added: “It appears that athletes with ADHD may suffer more with concussion and have a longer recovery time. This can inform our decision making and help these individuals to understand that they are at higher risk.”

Dr. Hainline said this raises another important point: “Concussion is not a homogeneous entity. It is a brain injury that can manifest in multiple parts of the brain, and the way the brain is from a premorbid or comorbid point of view can influence the manifestation of concussion as well,” he said. “All these things need to be taken into account.”

Attentional deficit may itself make an individual more susceptible to sustaining an injury in the first place, he said. “All of this is an evolving body of research which is helping clinicians to make better-informed decisions for athletes who may manifest differently.”

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

, a new study shows.

“Our results suggest kids with certain learning disorders may respond differently to concussion tests, and this needs to be taken into account when advising on recovery times and when they can return to sport,” said lead author Mathew Stokes, MD. Dr. Stokes is assistant professor of pediatrics and neurology/neurotherapeutics at the University of Texas–Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas.

The study was presented at the American Academy of Neurology Sports Concussion Virtual Conference, held online July 31 to Aug. 1.

Learning disorders affected scores

The researchers analyzed data from participants aged 10-18 years who were enrolled in the North Texas Concussion Registry (ConTex). Participants had been diagnosed with a concussion that was sustained within 30 days of enrollment. The researchers investigated whether there were differences between patients who had no history of learning disorders and those with a history of dyslexia and/or ADD/ADHD with regard to results of clinical testing following concussion.

Of the 1,298 individuals in the study, 58 had been diagnosed with dyslexia, 158 had been diagnosed with ADD/ADHD, and 35 had been diagnosed with both conditions. There was no difference in age, time since injury, or history of concussion between those with learning disorders and those without, but there were more male patients in the ADD/ADHD group.

Results showed that in the dyslexia group, mean time was slower (P = .011), and there was an increase in error scores on the King-Devick (KD) test (P = .028). That test assesses eye movements and involves the rapid naming of numbers that are spaced differently. In addition, those with ADD/ADHD had significantly higher impulse control scores (P = .007) on the ImPACT series of tests, which are commonly used in the evaluation of concussion. Participants with both dyslexia and ADHD demonstrated slower KD times (P = .009) and had higher depression scores and anxiety scores.

Dr. Stokes noted that a limiting factor of the study was that baseline scores were not available. “It is possible that kids with ADD have less impulse control even at baseline, and this would need to be taken into account,” he said. “You may perhaps also expect someone with dyslexia to have a worse score on the KD tests, so we need more data on how these scores are affected from baseline in these individuals. But our results show that when evaluating kids pre- or post concussion, it is important to know about learning disorders, as this will affect how we interpret the data.”

At 3-month follow-up, there were no longer significant differences in anxiety and depression scores for those with and those without learning disorders. “This suggests anxiety and depression may well be worse temporarily after concussion for those with ADD/ADHD but gets better with time,” Dr. Stokes said.

Follow-up data were not available for the other cognitive tests.

Are recovery times longer?

Asked whether young people with these learning disorders needed a longer time to recover after concussion, Dr. Stokes said: “That is a million-dollar question. Studies so far on this have shown conflicting results. Our results add to a growing body of literature on this.” He stressed that it is important to include anxiety and depression scores on both baseline and postconcussion tests. “People don’t tend to think of these symptoms as being associated with concussion, but they are actually very prominent in this situation,” he noted. “Our results suggest that individuals with ADHD may be more prone to anxiety and depression, and a blow to the head may tip them more into these symptoms.”

Discussing the study at a virtual press conference as part of the AAN Sports Concussion meeting, the codirector of the meeting, David Dodick, MD, Mayo Clinic, Scottsdale, Ariz., said: “This is a very interesting and important study which suggests there are differences between adolescents with a history of dyslexia/ADHD and those without these conditions in performance in concussion tests. Understanding the differences in these groups will help health care providers in evaluating these athletes and assisting in counseling them and their families with regard to their risk of injury.

“It is important to recognize that athletes with ADHD, whether or not they are on medication, may take longer to recover from a concussion,” Dr. Dodick added. They also exhibit greater reductions in cognitive skills and visual motor speed regarding hand-eye coordination, he said. There is an increase in the severity of symptoms. “Symptoms that exist in both groups tend to more severe in those individuals with ADHD,” he noted.

“Ascertaining the presence or absence of ADHD or dyslexia in those who are participating in sport is important, especially when trying to interpret the results of baseline testing, the results of postinjury testing, decisions on when to return to play, and assessing for individuals and their families the risk of long-term repeat concussions and adverse outcomes,” he concluded.

The other codirector of the AAN meeting, Brian Hainline, MD, chief medical officer of the National Collegiate Athletic Association, added: “It appears that athletes with ADHD may suffer more with concussion and have a longer recovery time. This can inform our decision making and help these individuals to understand that they are at higher risk.”

Dr. Hainline said this raises another important point: “Concussion is not a homogeneous entity. It is a brain injury that can manifest in multiple parts of the brain, and the way the brain is from a premorbid or comorbid point of view can influence the manifestation of concussion as well,” he said. “All these things need to be taken into account.”

Attentional deficit may itself make an individual more susceptible to sustaining an injury in the first place, he said. “All of this is an evolving body of research which is helping clinicians to make better-informed decisions for athletes who may manifest differently.”

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

, a new study shows.

“Our results suggest kids with certain learning disorders may respond differently to concussion tests, and this needs to be taken into account when advising on recovery times and when they can return to sport,” said lead author Mathew Stokes, MD. Dr. Stokes is assistant professor of pediatrics and neurology/neurotherapeutics at the University of Texas–Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas.

The study was presented at the American Academy of Neurology Sports Concussion Virtual Conference, held online July 31 to Aug. 1.

Learning disorders affected scores

The researchers analyzed data from participants aged 10-18 years who were enrolled in the North Texas Concussion Registry (ConTex). Participants had been diagnosed with a concussion that was sustained within 30 days of enrollment. The researchers investigated whether there were differences between patients who had no history of learning disorders and those with a history of dyslexia and/or ADD/ADHD with regard to results of clinical testing following concussion.

Of the 1,298 individuals in the study, 58 had been diagnosed with dyslexia, 158 had been diagnosed with ADD/ADHD, and 35 had been diagnosed with both conditions. There was no difference in age, time since injury, or history of concussion between those with learning disorders and those without, but there were more male patients in the ADD/ADHD group.

Results showed that in the dyslexia group, mean time was slower (P = .011), and there was an increase in error scores on the King-Devick (KD) test (P = .028). That test assesses eye movements and involves the rapid naming of numbers that are spaced differently. In addition, those with ADD/ADHD had significantly higher impulse control scores (P = .007) on the ImPACT series of tests, which are commonly used in the evaluation of concussion. Participants with both dyslexia and ADHD demonstrated slower KD times (P = .009) and had higher depression scores and anxiety scores.

Dr. Stokes noted that a limiting factor of the study was that baseline scores were not available. “It is possible that kids with ADD have less impulse control even at baseline, and this would need to be taken into account,” he said. “You may perhaps also expect someone with dyslexia to have a worse score on the KD tests, so we need more data on how these scores are affected from baseline in these individuals. But our results show that when evaluating kids pre- or post concussion, it is important to know about learning disorders, as this will affect how we interpret the data.”

At 3-month follow-up, there were no longer significant differences in anxiety and depression scores for those with and those without learning disorders. “This suggests anxiety and depression may well be worse temporarily after concussion for those with ADD/ADHD but gets better with time,” Dr. Stokes said.

Follow-up data were not available for the other cognitive tests.

Are recovery times longer?

Asked whether young people with these learning disorders needed a longer time to recover after concussion, Dr. Stokes said: “That is a million-dollar question. Studies so far on this have shown conflicting results. Our results add to a growing body of literature on this.” He stressed that it is important to include anxiety and depression scores on both baseline and postconcussion tests. “People don’t tend to think of these symptoms as being associated with concussion, but they are actually very prominent in this situation,” he noted. “Our results suggest that individuals with ADHD may be more prone to anxiety and depression, and a blow to the head may tip them more into these symptoms.”

Discussing the study at a virtual press conference as part of the AAN Sports Concussion meeting, the codirector of the meeting, David Dodick, MD, Mayo Clinic, Scottsdale, Ariz., said: “This is a very interesting and important study which suggests there are differences between adolescents with a history of dyslexia/ADHD and those without these conditions in performance in concussion tests. Understanding the differences in these groups will help health care providers in evaluating these athletes and assisting in counseling them and their families with regard to their risk of injury.

“It is important to recognize that athletes with ADHD, whether or not they are on medication, may take longer to recover from a concussion,” Dr. Dodick added. They also exhibit greater reductions in cognitive skills and visual motor speed regarding hand-eye coordination, he said. There is an increase in the severity of symptoms. “Symptoms that exist in both groups tend to more severe in those individuals with ADHD,” he noted.

“Ascertaining the presence or absence of ADHD or dyslexia in those who are participating in sport is important, especially when trying to interpret the results of baseline testing, the results of postinjury testing, decisions on when to return to play, and assessing for individuals and their families the risk of long-term repeat concussions and adverse outcomes,” he concluded.

The other codirector of the AAN meeting, Brian Hainline, MD, chief medical officer of the National Collegiate Athletic Association, added: “It appears that athletes with ADHD may suffer more with concussion and have a longer recovery time. This can inform our decision making and help these individuals to understand that they are at higher risk.”

Dr. Hainline said this raises another important point: “Concussion is not a homogeneous entity. It is a brain injury that can manifest in multiple parts of the brain, and the way the brain is from a premorbid or comorbid point of view can influence the manifestation of concussion as well,” he said. “All these things need to be taken into account.”

Attentional deficit may itself make an individual more susceptible to sustaining an injury in the first place, he said. “All of this is an evolving body of research which is helping clinicians to make better-informed decisions for athletes who may manifest differently.”

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

From AAN Sports Concussion Conference

Twelve risk factors linked to 40% of world’s dementia cases

according to an update of the Lancet Commission on Dementia Prevention, Intervention, and Care.

The original report, published in 2017, identified nine modifiable risk factors that were estimated to be responsible for one-third of dementia cases. The commission has now added three new modifiable risk factors to the list.

“We reconvened the 2017 Lancet Commission on Dementia Prevention, Intervention, and Care to identify the evidence for advances likely to have the greatest impact since our 2017 paper,” the authors wrote.

The 2020 report was presented at the virtual annual meeting of the Alzheimer’s Association International Conference (AAIC) 2020 and also was published online July 30 in the Lancet.

Alcohol, TBI, air pollution

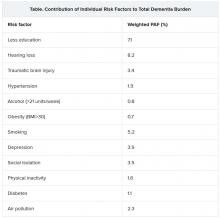

The three new risk factors that have been added in the latest update are excessive alcohol intake, traumatic brain injury (TBI), and air pollution. The original nine risk factors were not completing secondary education; hypertension; obesity; hearing loss; smoking; depression; physical inactivity; social isolation; and diabetes. Together, these 12 risk factors are estimated to account for 40% of the world’s dementia cases.

“We knew in 2017 when we published our first report with the nine risk factors that they would only be part of the story and that several other factors would likely be involved,” said lead author Gill Livingston, MD, professor, University College London (England). “We now have more published data giving enough evidence” to justify adding the three new factors to the list, she said.

The report includes the following nine recommendations for policymakers and individuals to prevent risk for dementia in the general population:

- Aim to maintain systolic blood pressure of 130 mm Hg or less in midlife from around age 40 years.

- Encourage use of hearing aids for hearing loss, and reduce hearing loss by protecting ears from high noise levels.

- Reduce exposure to air pollution and second-hand tobacco smoke.

- Prevent , particularly by targeting high-risk occupations and transport.

- Prevent alcohol misuse and limit drinking to less than 21 units per week.

- Stop smoking and support individuals to stop smoking, which the authors stress is beneficial at any age.

- Provide all children with primary and secondary education.

- Lead an active life into midlife and possibly later life.

- Reduce obesity and diabetes.

The report also summarizes the evidence supporting the three new risk factors for dementia.

TBI is usually caused by car, motorcycle, and bicycle injuries; military exposures; boxing, horse riding, and other recreational sports; firearms; and falls. The report notes that a single severe TBI is associated in humans and in mouse models with widespread hyperphosphorylated tau pathology. It also cites several nationwide studies that show that TBI is linked with a significantly increased risk for long-term dementia.

“We are not advising against partaking in sports, as playing sports is healthy. But we are urging people to take precautions to protect themselves properly,” Dr. Livingston said.

For excessive alcohol consumption, the report states that an “increasing body of evidence is emerging on alcohol’s complex relationship with cognition and dementia outcomes from a variety of sources including detailed cohorts and large-scale record-based studies.” One French study, which included more than 31 million individuals admitted to the hospital, showed that alcohol use disorders were associated with a threefold increased dementia risk. However, other studies have suggested that moderate drinking may be protective.

“We are not saying it is bad to drink, but we are saying it is bad to drink more than 21 units a week,” Dr. Livingston noted.

On air pollution, the report notes that in animal studies, airborne particulate pollutants have been found to accelerate neurodegenerative processes. Also, high nitrogen dioxide concentrations, fine ambient particulate matter from traffic exhaust, and residential wood burning have been shown in past research to be associated with increased dementia incidence.

“While we need international policy on reducing air pollution, individuals can take some action to reduce their risk,” Dr. Livingston said. For example, she suggested avoiding walking right next to busy roads and instead walking “a few streets back if possible.”

Hearing loss

The researchers assessed how much each risk factor contributes to dementia, expressed as the population-attributable fraction (PAF). Hearing loss had the greatest effect, accounting for an estimated 8.2% of dementia cases. This was followed by lower education levels in young people (7.1%) and smoking (5.2%).

Dr. Livingston noted that the evidence that hearing loss is one of the most important risk factors for dementia is very strong. New studies show that correcting hearing loss with hearing aids negates any increased risk.

Hearing loss “has both a high relative risk for dementia and is a common problem, so it contributes a significant amount to dementia cases. This is really something that we can reduce relatively easily by encouraging use of hearing aids. They need to be made more accessible, more comfortable, and more acceptable,” she said.

“This could make a huge difference in reducing dementia cases in the future,” Dr. Livingston added.

Other risk factors for which the evidence base has strengthened since the 2017 report include systolic blood pressure, social interaction, and early-life education.

Dr. Livingston noted that the SPRINT MIND trial showed that aiming for a target systolic blood pressure of 120 mm Hg reduced risk for future mild cognitive impairment. “Before, we thought under 140 was the target, but now are recommending under 130 to reduce risks of dementia,” she said.

Evidence on social interaction “has been very consistent, and we now have more certainty on this. It is now well established that increased social interaction in midlife reduces dementia in late life,” said Dr. Livingston.

On the benefits of education in the young, she noted that it has been known for some time that education for individuals younger than 11 years is important in reducing later-life dementia. However, it is now thought that education to the age of 20 also makes a difference.

“While keeping the brain active in later years has some positive effects, increasing brain activity in young people seems to be more important. This is probably because of the better plasticity of the brain in the young,” she said.

Sleep and diet

Two risk factors that have not made it onto the list are diet and sleep. “While there has also been a lot more data published on nutrition and sleep with regard to dementia in the last few years, we didn’t think the evidence stacked up enough to include these on the list of modifiable risk factors,” Dr. Livingston said.

The report cites studies that suggest that both more sleep and less sleep are associated with increased risk for dementia, which the authors thought did not make “biological sense.” In addition, other underlying factors involved in sleep, such as depression, apathy, and different sleep patterns, may be symptoms of early dementia.

More data have been published on diet and dementia, “but there isn’t any individual vitamin deficit that is associated with the condition. The evidence is quite clear on that,” Dr. Livingston said. “Global diets, such as the Mediterranean or Nordic diets, can probably make a difference, but there doesn’t seem to be any one particular element that is needed,” she noted.

“We just recommend to eat a healthy diet and stay a healthy weight. Diet is very connected to economic circumstances and so very difficult to separate out as a risk factor. We do think it is linked, but we are not convinced enough to put it in the model,” she added.

Among other key information that has become available since 2017, Dr. Livingston highlighted new data showing that dementia is more common in less privileged populations, including Black and minority ethnic groups and low- and middle-income countries.

Although dementia was traditionally considered a disease of high-income countries, that has now been shown not to be the case. “People in low- and middle-income countries are now living longer and so are developing dementia more, and they have higher rates of many of the risk factors, including smoking and low education levels. There is a huge potential for prevention in these countries,” said Dr. Livingston.

She also highlighted new evidence showing that patients with dementia do not do well when admitted to the hospital. “So we need to do more to keep them well at home,” she said.

COVID-19 advice

The report also has a section on COVID-19. It points out that patients with dementia are particularly vulnerable to the disease because of their age, multimorbidities, and difficulties in maintaining physical distancing. Death certificates from the United Kingdom indicate that dementia and Alzheimer’s disease were the most common underlying conditions (present in 25.6% of all deaths involving COVID-19).

The situation is particularly concerning in care homes. In one U.S. study, nursing home residents living with dementia made up 52% of COVID-19 cases, yet they accounted for 72% of all deaths (increased risk, 1.7), the commission reported.

The authors recommended rigorous public health measures, such as protective equipment and hygiene, not moving staff or residents between care homes, and not admitting new residents when their COVID-19 status is unknown. The report also recommends regular testing of staff in care homes and the provision of oxygen therapy at the home to avoid hospital admission.

It is also important to reduce isolation by providing the necessary equipment to relatives and offering them brief training on how to protect themselves and others from COVID-19 so that they can visit their relatives with dementia in nursing homes safely when it is allowed.

“Most comprehensive overview to date”

Alzheimer’s Research UK welcomed the new report. “This is the most comprehensive overview into dementia risk to date, building on previous work by this commission and moving our understanding forward,” Rosa Sancho, PhD, head of research at the charity, said.

“This report underlines the importance of acting at a personal and policy level to reduce dementia risk. With Alzheimer’s Research UK’s Dementia Attitudes Monitor showing just a third of people think it’s possible to reduce their risk of developing dementia, there’s clearly much to do here to increase people’s awareness of the steps they can take,” Dr. Sancho said.

She added that, although there is “no surefire way of preventing dementia,” the best way to keep a brain healthy as it ages is for an individual to stay physically and mentally active, eat a healthy balanced diet, not smoke, drink only within the recommended limits, and keep weight, cholesterol level, and blood pressure in check. “With no treatments yet able to slow or stop the onset of dementia, taking action to reduce these risks is an important part of our strategy for tackling the condition,” Dr. Sancho said.

The Lancet Commission is partnered by University College London, the Alzheimer’s Society UK, the Economic and Social Research Council, and Alzheimer’s Research UK, which funded fares, accommodation, and food for the commission meeting but had no role in the writing of the manuscript or the decision to submit it for publication.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

according to an update of the Lancet Commission on Dementia Prevention, Intervention, and Care.

The original report, published in 2017, identified nine modifiable risk factors that were estimated to be responsible for one-third of dementia cases. The commission has now added three new modifiable risk factors to the list.

“We reconvened the 2017 Lancet Commission on Dementia Prevention, Intervention, and Care to identify the evidence for advances likely to have the greatest impact since our 2017 paper,” the authors wrote.

The 2020 report was presented at the virtual annual meeting of the Alzheimer’s Association International Conference (AAIC) 2020 and also was published online July 30 in the Lancet.

Alcohol, TBI, air pollution

The three new risk factors that have been added in the latest update are excessive alcohol intake, traumatic brain injury (TBI), and air pollution. The original nine risk factors were not completing secondary education; hypertension; obesity; hearing loss; smoking; depression; physical inactivity; social isolation; and diabetes. Together, these 12 risk factors are estimated to account for 40% of the world’s dementia cases.

“We knew in 2017 when we published our first report with the nine risk factors that they would only be part of the story and that several other factors would likely be involved,” said lead author Gill Livingston, MD, professor, University College London (England). “We now have more published data giving enough evidence” to justify adding the three new factors to the list, she said.

The report includes the following nine recommendations for policymakers and individuals to prevent risk for dementia in the general population:

- Aim to maintain systolic blood pressure of 130 mm Hg or less in midlife from around age 40 years.

- Encourage use of hearing aids for hearing loss, and reduce hearing loss by protecting ears from high noise levels.

- Reduce exposure to air pollution and second-hand tobacco smoke.

- Prevent , particularly by targeting high-risk occupations and transport.

- Prevent alcohol misuse and limit drinking to less than 21 units per week.

- Stop smoking and support individuals to stop smoking, which the authors stress is beneficial at any age.

- Provide all children with primary and secondary education.

- Lead an active life into midlife and possibly later life.

- Reduce obesity and diabetes.

The report also summarizes the evidence supporting the three new risk factors for dementia.

TBI is usually caused by car, motorcycle, and bicycle injuries; military exposures; boxing, horse riding, and other recreational sports; firearms; and falls. The report notes that a single severe TBI is associated in humans and in mouse models with widespread hyperphosphorylated tau pathology. It also cites several nationwide studies that show that TBI is linked with a significantly increased risk for long-term dementia.

“We are not advising against partaking in sports, as playing sports is healthy. But we are urging people to take precautions to protect themselves properly,” Dr. Livingston said.

For excessive alcohol consumption, the report states that an “increasing body of evidence is emerging on alcohol’s complex relationship with cognition and dementia outcomes from a variety of sources including detailed cohorts and large-scale record-based studies.” One French study, which included more than 31 million individuals admitted to the hospital, showed that alcohol use disorders were associated with a threefold increased dementia risk. However, other studies have suggested that moderate drinking may be protective.

“We are not saying it is bad to drink, but we are saying it is bad to drink more than 21 units a week,” Dr. Livingston noted.

On air pollution, the report notes that in animal studies, airborne particulate pollutants have been found to accelerate neurodegenerative processes. Also, high nitrogen dioxide concentrations, fine ambient particulate matter from traffic exhaust, and residential wood burning have been shown in past research to be associated with increased dementia incidence.

“While we need international policy on reducing air pollution, individuals can take some action to reduce their risk,” Dr. Livingston said. For example, she suggested avoiding walking right next to busy roads and instead walking “a few streets back if possible.”

Hearing loss

The researchers assessed how much each risk factor contributes to dementia, expressed as the population-attributable fraction (PAF). Hearing loss had the greatest effect, accounting for an estimated 8.2% of dementia cases. This was followed by lower education levels in young people (7.1%) and smoking (5.2%).

Dr. Livingston noted that the evidence that hearing loss is one of the most important risk factors for dementia is very strong. New studies show that correcting hearing loss with hearing aids negates any increased risk.

Hearing loss “has both a high relative risk for dementia and is a common problem, so it contributes a significant amount to dementia cases. This is really something that we can reduce relatively easily by encouraging use of hearing aids. They need to be made more accessible, more comfortable, and more acceptable,” she said.

“This could make a huge difference in reducing dementia cases in the future,” Dr. Livingston added.

Other risk factors for which the evidence base has strengthened since the 2017 report include systolic blood pressure, social interaction, and early-life education.

Dr. Livingston noted that the SPRINT MIND trial showed that aiming for a target systolic blood pressure of 120 mm Hg reduced risk for future mild cognitive impairment. “Before, we thought under 140 was the target, but now are recommending under 130 to reduce risks of dementia,” she said.

Evidence on social interaction “has been very consistent, and we now have more certainty on this. It is now well established that increased social interaction in midlife reduces dementia in late life,” said Dr. Livingston.

On the benefits of education in the young, she noted that it has been known for some time that education for individuals younger than 11 years is important in reducing later-life dementia. However, it is now thought that education to the age of 20 also makes a difference.

“While keeping the brain active in later years has some positive effects, increasing brain activity in young people seems to be more important. This is probably because of the better plasticity of the brain in the young,” she said.

Sleep and diet

Two risk factors that have not made it onto the list are diet and sleep. “While there has also been a lot more data published on nutrition and sleep with regard to dementia in the last few years, we didn’t think the evidence stacked up enough to include these on the list of modifiable risk factors,” Dr. Livingston said.

The report cites studies that suggest that both more sleep and less sleep are associated with increased risk for dementia, which the authors thought did not make “biological sense.” In addition, other underlying factors involved in sleep, such as depression, apathy, and different sleep patterns, may be symptoms of early dementia.

More data have been published on diet and dementia, “but there isn’t any individual vitamin deficit that is associated with the condition. The evidence is quite clear on that,” Dr. Livingston said. “Global diets, such as the Mediterranean or Nordic diets, can probably make a difference, but there doesn’t seem to be any one particular element that is needed,” she noted.

“We just recommend to eat a healthy diet and stay a healthy weight. Diet is very connected to economic circumstances and so very difficult to separate out as a risk factor. We do think it is linked, but we are not convinced enough to put it in the model,” she added.

Among other key information that has become available since 2017, Dr. Livingston highlighted new data showing that dementia is more common in less privileged populations, including Black and minority ethnic groups and low- and middle-income countries.

Although dementia was traditionally considered a disease of high-income countries, that has now been shown not to be the case. “People in low- and middle-income countries are now living longer and so are developing dementia more, and they have higher rates of many of the risk factors, including smoking and low education levels. There is a huge potential for prevention in these countries,” said Dr. Livingston.

She also highlighted new evidence showing that patients with dementia do not do well when admitted to the hospital. “So we need to do more to keep them well at home,” she said.

COVID-19 advice

The report also has a section on COVID-19. It points out that patients with dementia are particularly vulnerable to the disease because of their age, multimorbidities, and difficulties in maintaining physical distancing. Death certificates from the United Kingdom indicate that dementia and Alzheimer’s disease were the most common underlying conditions (present in 25.6% of all deaths involving COVID-19).

The situation is particularly concerning in care homes. In one U.S. study, nursing home residents living with dementia made up 52% of COVID-19 cases, yet they accounted for 72% of all deaths (increased risk, 1.7), the commission reported.

The authors recommended rigorous public health measures, such as protective equipment and hygiene, not moving staff or residents between care homes, and not admitting new residents when their COVID-19 status is unknown. The report also recommends regular testing of staff in care homes and the provision of oxygen therapy at the home to avoid hospital admission.

It is also important to reduce isolation by providing the necessary equipment to relatives and offering them brief training on how to protect themselves and others from COVID-19 so that they can visit their relatives with dementia in nursing homes safely when it is allowed.

“Most comprehensive overview to date”

Alzheimer’s Research UK welcomed the new report. “This is the most comprehensive overview into dementia risk to date, building on previous work by this commission and moving our understanding forward,” Rosa Sancho, PhD, head of research at the charity, said.

“This report underlines the importance of acting at a personal and policy level to reduce dementia risk. With Alzheimer’s Research UK’s Dementia Attitudes Monitor showing just a third of people think it’s possible to reduce their risk of developing dementia, there’s clearly much to do here to increase people’s awareness of the steps they can take,” Dr. Sancho said.

She added that, although there is “no surefire way of preventing dementia,” the best way to keep a brain healthy as it ages is for an individual to stay physically and mentally active, eat a healthy balanced diet, not smoke, drink only within the recommended limits, and keep weight, cholesterol level, and blood pressure in check. “With no treatments yet able to slow or stop the onset of dementia, taking action to reduce these risks is an important part of our strategy for tackling the condition,” Dr. Sancho said.

The Lancet Commission is partnered by University College London, the Alzheimer’s Society UK, the Economic and Social Research Council, and Alzheimer’s Research UK, which funded fares, accommodation, and food for the commission meeting but had no role in the writing of the manuscript or the decision to submit it for publication.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

according to an update of the Lancet Commission on Dementia Prevention, Intervention, and Care.

The original report, published in 2017, identified nine modifiable risk factors that were estimated to be responsible for one-third of dementia cases. The commission has now added three new modifiable risk factors to the list.

“We reconvened the 2017 Lancet Commission on Dementia Prevention, Intervention, and Care to identify the evidence for advances likely to have the greatest impact since our 2017 paper,” the authors wrote.

The 2020 report was presented at the virtual annual meeting of the Alzheimer’s Association International Conference (AAIC) 2020 and also was published online July 30 in the Lancet.

Alcohol, TBI, air pollution

The three new risk factors that have been added in the latest update are excessive alcohol intake, traumatic brain injury (TBI), and air pollution. The original nine risk factors were not completing secondary education; hypertension; obesity; hearing loss; smoking; depression; physical inactivity; social isolation; and diabetes. Together, these 12 risk factors are estimated to account for 40% of the world’s dementia cases.

“We knew in 2017 when we published our first report with the nine risk factors that they would only be part of the story and that several other factors would likely be involved,” said lead author Gill Livingston, MD, professor, University College London (England). “We now have more published data giving enough evidence” to justify adding the three new factors to the list, she said.

The report includes the following nine recommendations for policymakers and individuals to prevent risk for dementia in the general population:

- Aim to maintain systolic blood pressure of 130 mm Hg or less in midlife from around age 40 years.

- Encourage use of hearing aids for hearing loss, and reduce hearing loss by protecting ears from high noise levels.

- Reduce exposure to air pollution and second-hand tobacco smoke.

- Prevent , particularly by targeting high-risk occupations and transport.

- Prevent alcohol misuse and limit drinking to less than 21 units per week.

- Stop smoking and support individuals to stop smoking, which the authors stress is beneficial at any age.

- Provide all children with primary and secondary education.

- Lead an active life into midlife and possibly later life.

- Reduce obesity and diabetes.

The report also summarizes the evidence supporting the three new risk factors for dementia.

TBI is usually caused by car, motorcycle, and bicycle injuries; military exposures; boxing, horse riding, and other recreational sports; firearms; and falls. The report notes that a single severe TBI is associated in humans and in mouse models with widespread hyperphosphorylated tau pathology. It also cites several nationwide studies that show that TBI is linked with a significantly increased risk for long-term dementia.

“We are not advising against partaking in sports, as playing sports is healthy. But we are urging people to take precautions to protect themselves properly,” Dr. Livingston said.

For excessive alcohol consumption, the report states that an “increasing body of evidence is emerging on alcohol’s complex relationship with cognition and dementia outcomes from a variety of sources including detailed cohorts and large-scale record-based studies.” One French study, which included more than 31 million individuals admitted to the hospital, showed that alcohol use disorders were associated with a threefold increased dementia risk. However, other studies have suggested that moderate drinking may be protective.

“We are not saying it is bad to drink, but we are saying it is bad to drink more than 21 units a week,” Dr. Livingston noted.

On air pollution, the report notes that in animal studies, airborne particulate pollutants have been found to accelerate neurodegenerative processes. Also, high nitrogen dioxide concentrations, fine ambient particulate matter from traffic exhaust, and residential wood burning have been shown in past research to be associated with increased dementia incidence.

“While we need international policy on reducing air pollution, individuals can take some action to reduce their risk,” Dr. Livingston said. For example, she suggested avoiding walking right next to busy roads and instead walking “a few streets back if possible.”

Hearing loss

The researchers assessed how much each risk factor contributes to dementia, expressed as the population-attributable fraction (PAF). Hearing loss had the greatest effect, accounting for an estimated 8.2% of dementia cases. This was followed by lower education levels in young people (7.1%) and smoking (5.2%).

Dr. Livingston noted that the evidence that hearing loss is one of the most important risk factors for dementia is very strong. New studies show that correcting hearing loss with hearing aids negates any increased risk.

Hearing loss “has both a high relative risk for dementia and is a common problem, so it contributes a significant amount to dementia cases. This is really something that we can reduce relatively easily by encouraging use of hearing aids. They need to be made more accessible, more comfortable, and more acceptable,” she said.

“This could make a huge difference in reducing dementia cases in the future,” Dr. Livingston added.

Other risk factors for which the evidence base has strengthened since the 2017 report include systolic blood pressure, social interaction, and early-life education.

Dr. Livingston noted that the SPRINT MIND trial showed that aiming for a target systolic blood pressure of 120 mm Hg reduced risk for future mild cognitive impairment. “Before, we thought under 140 was the target, but now are recommending under 130 to reduce risks of dementia,” she said.

Evidence on social interaction “has been very consistent, and we now have more certainty on this. It is now well established that increased social interaction in midlife reduces dementia in late life,” said Dr. Livingston.

On the benefits of education in the young, she noted that it has been known for some time that education for individuals younger than 11 years is important in reducing later-life dementia. However, it is now thought that education to the age of 20 also makes a difference.

“While keeping the brain active in later years has some positive effects, increasing brain activity in young people seems to be more important. This is probably because of the better plasticity of the brain in the young,” she said.

Sleep and diet

Two risk factors that have not made it onto the list are diet and sleep. “While there has also been a lot more data published on nutrition and sleep with regard to dementia in the last few years, we didn’t think the evidence stacked up enough to include these on the list of modifiable risk factors,” Dr. Livingston said.

The report cites studies that suggest that both more sleep and less sleep are associated with increased risk for dementia, which the authors thought did not make “biological sense.” In addition, other underlying factors involved in sleep, such as depression, apathy, and different sleep patterns, may be symptoms of early dementia.

More data have been published on diet and dementia, “but there isn’t any individual vitamin deficit that is associated with the condition. The evidence is quite clear on that,” Dr. Livingston said. “Global diets, such as the Mediterranean or Nordic diets, can probably make a difference, but there doesn’t seem to be any one particular element that is needed,” she noted.

“We just recommend to eat a healthy diet and stay a healthy weight. Diet is very connected to economic circumstances and so very difficult to separate out as a risk factor. We do think it is linked, but we are not convinced enough to put it in the model,” she added.

Among other key information that has become available since 2017, Dr. Livingston highlighted new data showing that dementia is more common in less privileged populations, including Black and minority ethnic groups and low- and middle-income countries.

Although dementia was traditionally considered a disease of high-income countries, that has now been shown not to be the case. “People in low- and middle-income countries are now living longer and so are developing dementia more, and they have higher rates of many of the risk factors, including smoking and low education levels. There is a huge potential for prevention in these countries,” said Dr. Livingston.

She also highlighted new evidence showing that patients with dementia do not do well when admitted to the hospital. “So we need to do more to keep them well at home,” she said.

COVID-19 advice

The report also has a section on COVID-19. It points out that patients with dementia are particularly vulnerable to the disease because of their age, multimorbidities, and difficulties in maintaining physical distancing. Death certificates from the United Kingdom indicate that dementia and Alzheimer’s disease were the most common underlying conditions (present in 25.6% of all deaths involving COVID-19).

The situation is particularly concerning in care homes. In one U.S. study, nursing home residents living with dementia made up 52% of COVID-19 cases, yet they accounted for 72% of all deaths (increased risk, 1.7), the commission reported.

The authors recommended rigorous public health measures, such as protective equipment and hygiene, not moving staff or residents between care homes, and not admitting new residents when their COVID-19 status is unknown. The report also recommends regular testing of staff in care homes and the provision of oxygen therapy at the home to avoid hospital admission.

It is also important to reduce isolation by providing the necessary equipment to relatives and offering them brief training on how to protect themselves and others from COVID-19 so that they can visit their relatives with dementia in nursing homes safely when it is allowed.

“Most comprehensive overview to date”

Alzheimer’s Research UK welcomed the new report. “This is the most comprehensive overview into dementia risk to date, building on previous work by this commission and moving our understanding forward,” Rosa Sancho, PhD, head of research at the charity, said.

“This report underlines the importance of acting at a personal and policy level to reduce dementia risk. With Alzheimer’s Research UK’s Dementia Attitudes Monitor showing just a third of people think it’s possible to reduce their risk of developing dementia, there’s clearly much to do here to increase people’s awareness of the steps they can take,” Dr. Sancho said.