User login

Alcohol-use disorders after bariatric surgery: The case for targeted group therapy

Maladaptive alcohol use has emerged as a risk for a subset of individuals who have undergone weight loss surgery (WLS); studies report they are vulnerable to consuming alcohol in greater quantities or more frequently.1,2 Estimates of the prevalence of “high-risk” or “hazardous” alcohol use after WLS range from 4% to 28%,3,4 while the prevalence of alcohol use meeting DSM-IV-TR5 criteria for alcohol use disorders (AUDs) hovers around 10%.6

Heavy alcohol users or patients who have active AUD at the time of WLS are at greater risk for continuation of these problems after surgery.2,6 For patients with a long-remitted history of AUD, the evidence regarding risk for post-WLS relapse is lacking, and some evidence suggests they may have better weight loss outcomes after WLS.7

However, approximately two-third of cases of post-WLS alcohol problems occur in patients who have had no history of such problems before surgery.5,8,9 Reported prevalence rates of new-onset alcohol problems range from 3% to 18%,6,9 with the modal finding being approximately 7% to 8%. New-onset alcohol problems appear to occur at a considerable latency after surgery. One study found little risk at 1 year post-surgery, but a significant increase in AUD symptoms at 2 years.6 Another study identified 3 years post-surgery as a high-risk time point,8 and yet another reported a linear increase in the risk for developing alcohol problems for at least 10 years after WLS.10

This article describes a group treatment protocol developed specifically for patients with post-WLS substance use disorder (SUD), and explores:

- risk factors and causal mechanisms of post-WLS AUDs

- weight stigma and emotional stressors

- the role of specialized treatment

- group treatment based on the Health at Every Size® (HAES)-oriented, trauma-informed and fat acceptance framework.

Post-WLS patients with alcohol problems may be a distinct phenotype among people with substance abuse issues. For this reason, they may have a need to address their experiences and issues specific to WLS as part of their alcohol treatment.

Etiology

Risk factors. Empirical findings have identified few predictors or risk factors for post-WLS SUD. These patients are more likely to be male and of a younger age.6 Notably, the vast majority of individuals reporting post-WLS alcohol problems have undergone Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (RYGB), rather than other WLS procedures, such as the laparoscopic adjustable gastric band,6,11 suggesting some physiological mechanism specific to RYGB.

Other potential predictors of postoperative alcohol problems include a pre-operative history of depression, generalized anxiety disorder, smoking, and/or recreational drug use.3,6 Likewise, patients with depression or anxiety disorder symptoms after surgery also may be at higher risk for postoperative alcohol problems.4 The evidence of an association between postoperative weight outcomes and post-WLS alcohol problems is mixed.3,12 Interestingly, patients who had no personal history of substance abuse but who have a family history may have a higher risk of new-onset alcohol problems after surgery.9,12

Causal mechanisms. The etiology of post-WLS alcohol problems is not well understood. If anything, epidemiological data suggest that larger-bodied individuals tend to consume lower levels of alcohol and have lower rates of AUD than individuals in the general population with thinner bodies.13 However, an association has been found between a family history of SUD, but not a personal history, and being large.14 This suggests a shared etiological pathway between addiction and being “overweight,” of which the onset of AUD after RYGB may be a manifestation.

Human and animal studies have shown that WLS may affect alcohol use differently in specific subgroups. Studies have shown that wild-type rats greatly increase their consumption of, or operant responding for, alcohol after RYGB,15 while genetically “alcohol-preferring” rats decrease consumption of, or responding for, alcohol after RYGB.16 A human study likewise found some patients decreased alcohol use or experienced improvement of or remission of AUD symptoms after WLS.4 Combined with the finding that a family history of substance abuse is related to risk for post-operative AUD, these data suggest a potential genetic vulnerability or protection in some individuals.

Turning to potential psychosocial explanations, the lay media has popularized the concepts of “addiction transfer,” or “transfer addiction,”12 with the implication that some patients, who had a preoperative history of “food addiction,” transfer that “addiction” after surgery to substances of abuse.

However, the “addiction transfer” model has a number of flaws:

- it is stigmatizing, because it assumes the patient possesses an innate, chronic, and inalterable pathology

- it relies upon the validity of the controversial construct of “food addiction,” a construct of mixed scientific evidence.17

Further, our knowledge of post-WLS SUD argues against “addiction transfer.” As noted, postoperative alcohol problems are more likely to develop years after surgery, rather than in the first few months afterward when eating is most significantly curtailed. Additionally, post-WLS alcohol problems are significantly more likely to occur after RYGB than other procedures, whereas the “addiction transfer” model would hypothesize that all WLS patients would be at equal risk for postoperative “addiction transfer,” because their eating is similarly affected after surgery.

Links to RYGB. Some clues to physiological mechanisms underlying alcohol problems after RYGB have been identified. After surgery, many RYGB patients report a quicker effect from a smaller amount of alcohol than was the case pre-surgery.18 Studies have demonstrated a number of changes in the pharmacodynamics of alcohol after RYGB not seen in other WLS procedures19:

- a much faster time to peak blood (or breath) alcohol content (BAC)

- significantly higher peak BAC

- a precipitous initial decline in perceived intoxication.18,20

Anatomical features of RYGB may explain such changes.8 However, an increased response to both IV alcohol and IV morphine after RYGB21,22 in rodents suggests that gastrointestinal tract changes are not solely responsible for changes in alcohol use. Emerging research reports that WLS has been found to cause alterations in brain reward pathways,23 which may be an additional contributor to changes in alcohol misuse after surgery.

However, even combined, pharmacokinetic and neurobiological factors cannot entirely explain new-onset alcohol problems after WLS; if they could, one would expect to see a much higher prevalence of this complication. Some psychosocial factors are likely involved as well.

Emotional stressors. One possibility involves a mismatch between post-WLS stressors and coping skills. After WLS, these patients face a multitude of challenges inherent in adjusting to changes in lifestyle, weight, body image, and social functioning, which most individuals would find daunting. These challenges become even more acute in the absence of appropriate psychoeducation, preparation, and intervention from qualified professionals. Individuals who lack effective and adaptive coping skills and supports may have a particularly heightened vulnerability to increased alcohol use in the setting of post-surgery changes in brain reward circuits and pharmacodynamics in alcohol metabolism. For example, one patient reported that her spouse’s pressure to “do something about her weight” was a significant factor in her decision to undergo surgery, but that her spouse was blaming and unsupportive when post-WLS complications developed. The patient believed that these experiences helped fuel development of her post-RYGB alcohol abuse.

Specialized treatment

The number of patients experiencing post-WLS alcohol problems likely will continue to grow, given that the risk of onset of has been shown increase over years. Already, post-WLS patients are proportionally overrepresented among substance abuse treatment populations.24 Empirically, however, we do not know yet if these patients need a different type of addiction treatment than patients who have not had WLS.

Some evidence suggests that post-WLS patients with alcohol problems may be a distinct phenotype within the general population with alcohol problems, as their presentations differ in several ways, including their demographics, alcohol use patterns, and premorbid functioning. A number of studies have found that, despite their increased pharmacodynamic sensitivity to alcohol, people with post-WLS AUDs actually consume a larger amount of alcohol on both typical and maximum drinking days than other individuals with AUDs.24 Additionally, although the median age of onset for AUD is around age 20,25 patients presenting with new-onset, post-WLS alcohol problems are usually in their late 30s, or even 40s or 50s. Further, many of these patients were quite high functioning before their alcohol problems, and are unlikely to identify with the cultural stereotype of a person with AUD (eg, homeless, unemployed), which may hamper or delay their own willingness to accept that they have a problem. These phenotypic differences suggest that post-WLS patients may require substance abuse treatment approaches tailored to their unique presentation. There are additional factors specific to the experiences of being larger-bodied and WLS that also may need to be addressed in specialized treatment for post-WLS addiction patients.

Weight stigma. By definition, patients who have undergone WLS have spent a significant portion of their lives inhabiting larger bodies, an experience that, in our culture, can produce adverse psychosocial effects. Compared with the general population, patients seeking WLS exhibit psychological distress equivalent to psychiatric patients.26 Weight stigma or weight bias—negative judgments directed toward people in larger bodies—is pervasive and continues to increase.27 Further, evidence suggests that, unlike almost all other stigmatized groups, people in larger bodies tend to internalize this stigma, holding an unfavorable attitude toward their own social group.28 Weight stigma impacts the well-being of people all along the weight spectrum, affecting many domains including educational achievements and classroom experiences, job opportunities, salaries, and medical care.27 Weight stigma increases the likelihood of bullying, teasing, and harassment for both adults and children.27 Weight bias has been associated with any number of adverse psychosocial effects, including symptoms of depression, anxiety, and eating pathology; poor body image; and a decrease in healthy self-care behaviors.29-33

Weight stigma makes it more difficult for people to enjoy physical activities, nourish their bodies, and manage stress, which contributes to poorer health outcomes and lower quality of life.33,34 For example, one study showed that, regardless of actual body mass index, people experiencing weight stigma have significantly increased risk of developing an illness or dying.35

Factors specific to WLS. WLS may lead to significant changes in eating habits, and some patients experience a sense of loss, particularly if eating represented one of their primary coping strategies—this may represent a heightened emotional vulnerability for developing AUD.

The fairly rapid and substantial weight loss that WLS produces can lead to sweeping changes in lifestyle, body image, and functional factors for many individuals. Patients often report profound changes, both positive and negative, in their relationships and interactions not only with people in their support network, but also with strangers.36

After the first year or 2 post-WLS, it is fairly common for patients to regain some weight, sometimes in significant amounts.37 This can lead to a sense of “failure.” Life stressors, including difficulties in important relationships, can further add to patients’ vulnerability. For example, one patient noticed that when she was at her thinnest after WLS, drivers were more likely to stop for her when she crossed the street, which pleased but also angered her because they hadn’t extended the same courtesy before WLS. After she regained a significant amount of weight, she began to notice drivers stopping for her less and less frequently. This took her back to her previous feelings of being ignored but now with the certainty that she would be treated better if she were thinner.

Patients also may experience ambivalence about changes in their body size. One might expect that body image would improve after weight loss, but the evidence is mixed.38 Although there is some evidence that body image improves in the short term after WLS,38 other research indicates that body image does not improve with weight loss.39 However, the evidence is clear that the appearance of excess skin after weight loss worsens some patients’ body image.40

To date, there has been no research examining treatment modalities for this population. Because experiences common to individuals who have had WLS could play a role in the development of AUD after surgery, it is intuitive that it would be important to address these factors when designing a treatment plan for post-WLS substance abuse.

Group treatment approach

In 2013, in response to the increase in rates of post-WLS addictions presenting to West End Clinic, an outpatient dual-diagnosis (addiction and psychiatry) service at Massachusetts General Hospital, a specialized treatment group was developed. Nine patients have enrolled since October 2013.

The Post-WLS Addictions Group (PWAG) was designed to be HAES-oriented, trauma-informed, and run within a fat acceptance framework. The HAES model prioritizes a weight-neutral approach that sees health and well-being as multifaceted. This approach directs both patient and clinician to focus on improving health behaviors and reducing internalized weight bias, while building a supportive community that buffers against external cultural weight bias.41

Trauma-informed care42 emphasizes the principles of safety, trustworthiness, and transparency; peer support; collaboration and mutuality; empowerment; and awareness of cultural, historical, and gender issues. In the context of PWAG, weight stigma is conceptualized as a traumatic experience.43 The fat acceptance approach promotes a culture that accepts people of every size with dignity and equality in all aspects of life.44

Self-care emphasis. The HAES model encourages patients to allow their bodies to determine what weight to settle at, and to focus on sustainable health-enhancing behaviors rather than weight loss. Patients who asked about the PWAG were told that this group would not explicitly support, or even encourage, continued pursuit of weight loss per se, but instead would assist patients with relapse prevention, mindful eating, improving self-care, and ongoing stress management. Moving away from a focus on weight loss and toward improvement of self-care skills allowed patients to focus on behaviors and outcomes over which they had more direct control and were more likely to yield immediate benefits.

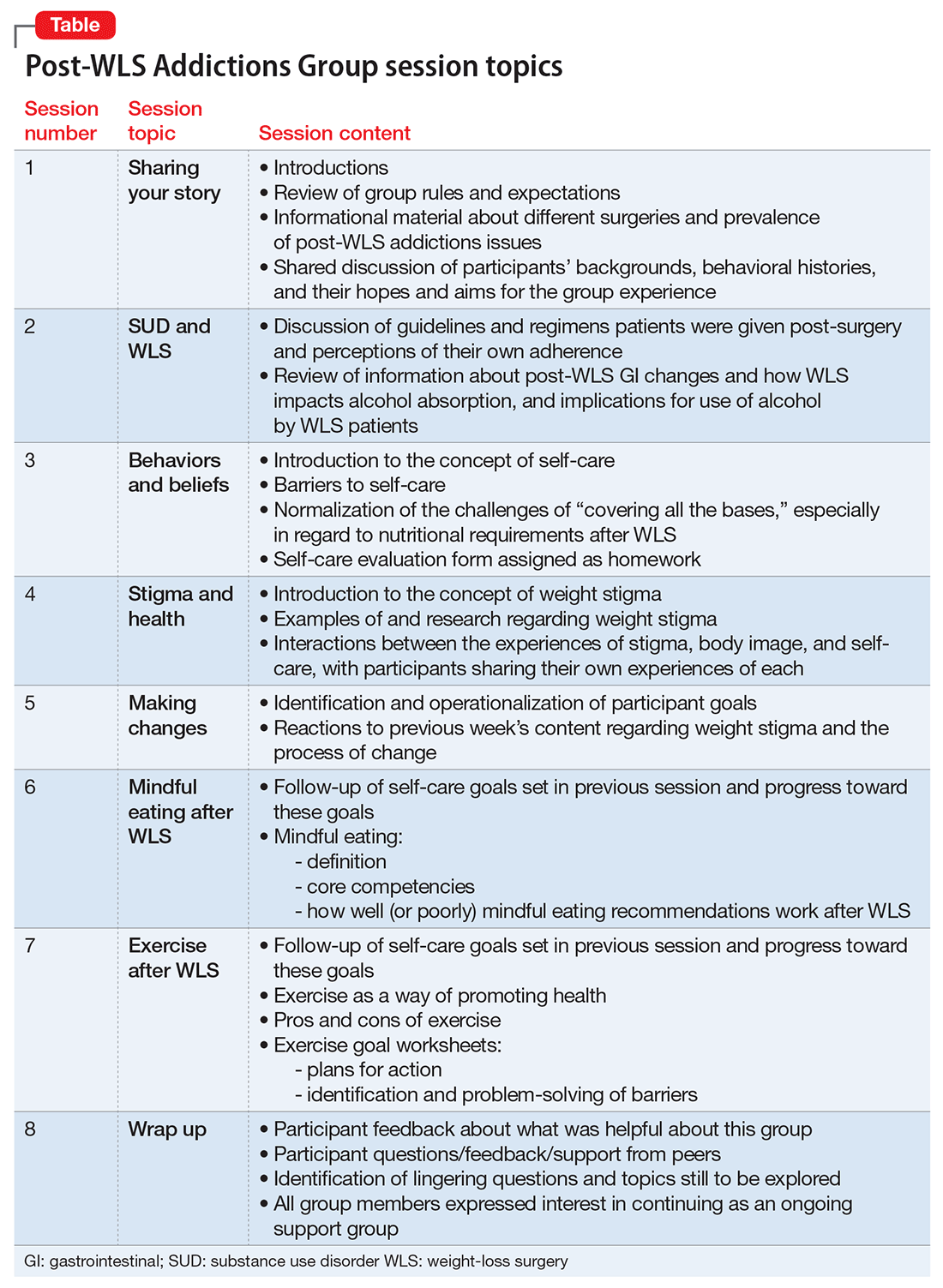

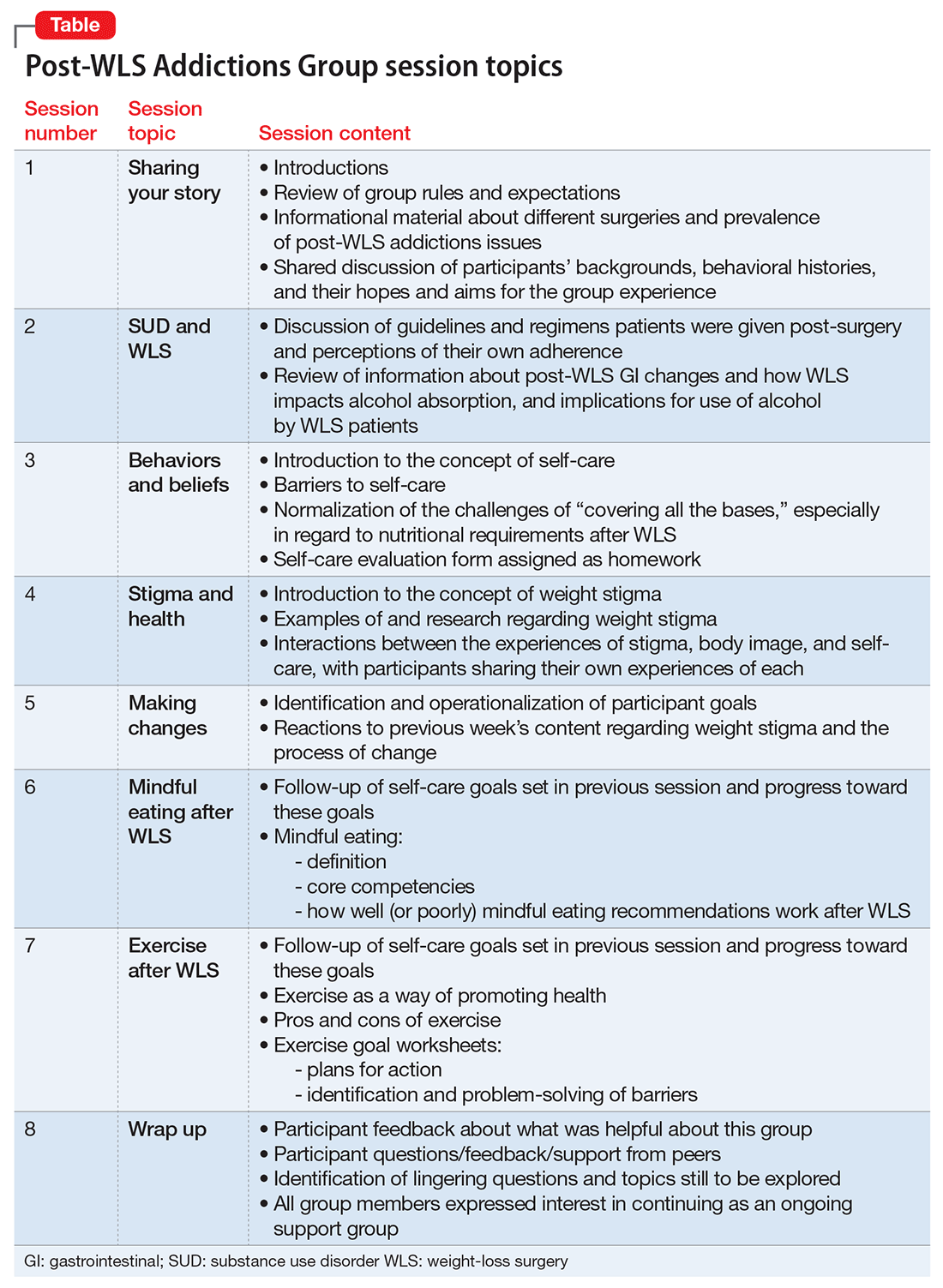

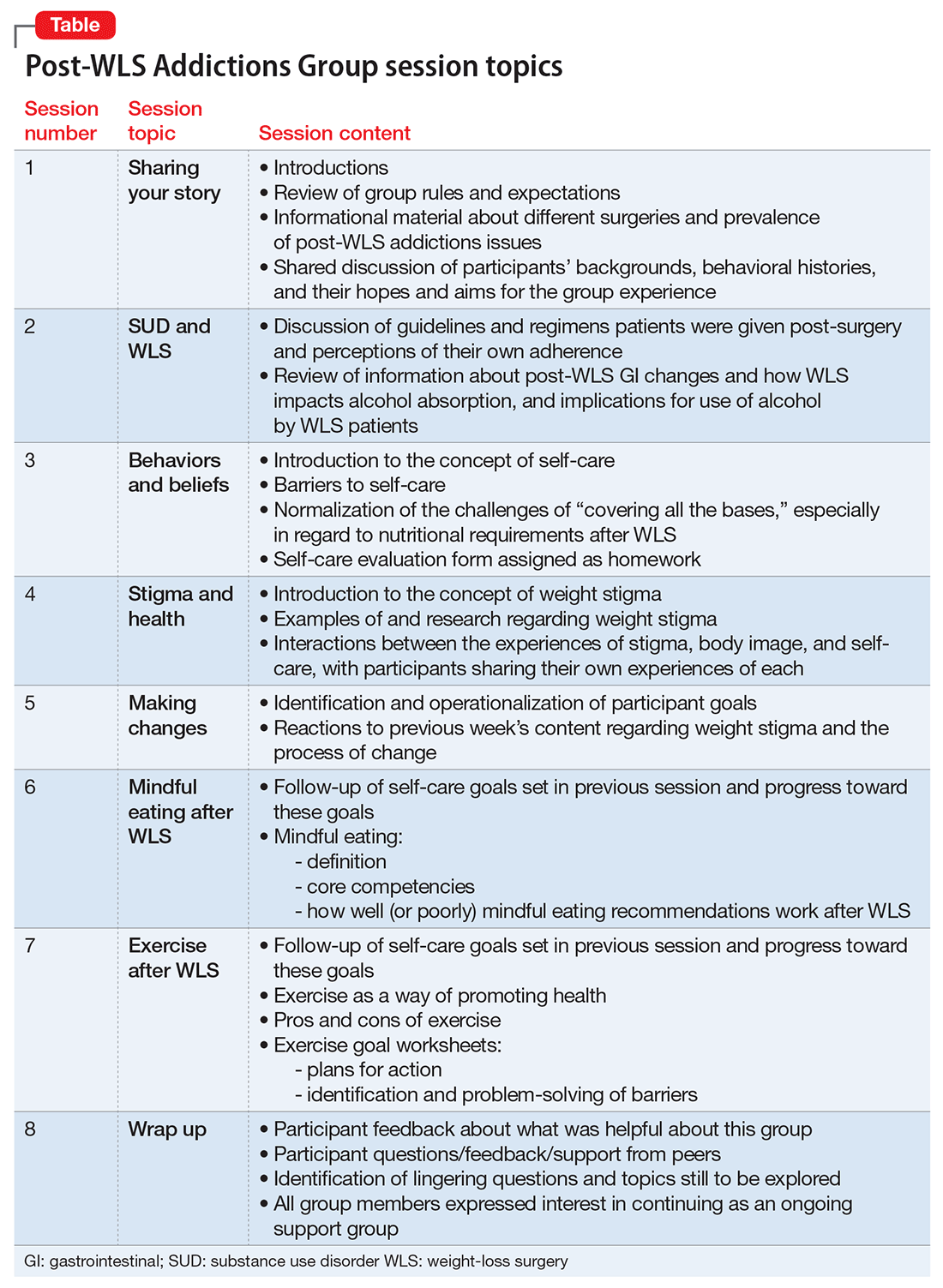

All of the PWAG group members were in early recovery from an SUD, with a minimum of 4 weeks of abstinence; all had at least 1 co-occurring mental health diagnosis. A licensed independent clinical social worker (LICSW) and a physician familiar with bariatric surgery ran the sessions. The group met weekly for 1 hour. The 8 weekly sessions included both psychoeducation and discussion, with each session covering different topics (Table). The first 20 minutes of each session were devoted to an educational presentation; the remaining 40 minutes for reflection and discussion. In sessions 2 through 8, participants were asked about any recent use or cravings, and problem-solving techniques were employed as needed.

The PWAG group leader herself is a large person who modeled fat acceptance and follows the HAES approach; she led the group using both this experience and her specialized clinical training. As is the case with other addictions recovery treatment modalities, clinicians with lived experience may add a valuable component to both the program design and patient experience.

After the first 8 sessions, all members expressed interest in continuing as an ongoing relapse prevention and HAES support group, and they reported that meeting regularly was very helpful. The group continued with the LICSW alone, who continued to share HAES-oriented and fat acceptance information and resources that group members requested specifically. Over time, new members joined following an individual orientation session with the group leader, and the group has revisited each of the psychoeducational topics repeatedly, though not in a formally structured way.

Process and observations. Participants described high levels of excitement and hopefulness about being in a group with other WLS patients who had developed SUDs. They had a particular interest in reviewing medical/anatomical information about WLS and understanding more about the potential reasons for the elevated risk for developing SUD following WLS. Discussions regarding weight stigma proved to be quite emotional; most participants reported that this material readily related to their own experiences with weight stigma, but they had never discussed these ideas before.

Participants explored the role that grief, loss, guilt, and shame had in the decision to have WLS, the development of SUDs, weight regain or medical complications from the surgery or from substance abuse, career and relationship changes, and worsened body image. Another theme that emerged was the various reasons that prompted the members have WLS that they may not have been conscious of, or willing to discuss with others, such as pressure from a spouse, fears of remaining single due to their size, and a desire to finally “fit in.”

Repeatedly, group members expressed how satisfied and emotionally validated they felt being with people with similar experiences. Most of them had felt alone. They reported a belief that “everyone else” who had WLS was doing well, and that they were the exceptions. Such beliefs and emotions increased the risk of relapse and decreased participants’ ability to develop more positive coping strategies and self-care skills.

Participants reported that feeling less alone, understanding how stigma impacts health and well-being, and focusing on the general benefits of good self-care rather than the pursuit of weight loss were particularly helpful. The HAES and fat acceptance approaches have given group members new ways to think about their bodies and decreased shame. Several group members reported that if they had learned about the HAES approach prior to having a WLS, they might have made a different decision about having surgery, or at least might have been better prepared to handle the emotional and psychological challenges after WLS.

Although evidence for post-WLS addictions is fairly robust, causal mechanisms are not well understood, and research identifying specific risk factors is lacking. Because post-WLS patients with addictions seem to represent a specific phenotype, specialized treatment might be indicated. Future research will be needed to determine optimal treatment approaches for post-WLS addictions. However, a number of aspects are likely to be important. For example, it is likely that unaddressed experiences of weight stigma contribute to challenges, including substance abuse, after WLS; therefore, clinicians involved in the care of individuals presenting with post-WLS SUD should be knowledgeable about weight stigma and how to address it. Because of the specific nature of post-WLS addictions, patients often feel alone and isolated, and seem to benefit from the specialized group setting. We note that the PWAG group leader is herself a large person who models fat acceptance and follows the HAES approach, and therefore led the group using this experience and her specialized clinical training. As with other addiction recovery treatment modalities, clinicians who have lived the experience can add a valuable component to the program design and patient experience.

2. Lent MR, Hayes SM, Wood GC, et al. Smoking and alcohol use in gastric bypass patients. Eat Behav. 2013;14(4):460-463.

4. Wee CC, Mukamal KJ, Huskey KW, et al. High-risk alcohol use after weight loss surgery. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2014;10(3):508-513.

5. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 4th, text rev. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2000.

6. King WC, Chen JY, Mitchell JE, et al. Prevalence of alcohol use disorders before and after bariatric surgery. JAMA. 2012;307(23):2516-2525.

9. Ivezaj V, Saules KK, Schuh LM. New-onset substance use disorder after gastric bypass surgery: rates and associated characteristics. Obes Surg. 2014;24(11):1975-1980.

10. Svensson PA, Anveden Å, Romeo S, et al. Alcohol consumption and alcohol problems after bariatric surgery in the Swedish obese subjects study. Obesity. 2013;21(12):2444-2451.

11. Ostlund MP, Backman O, Marsk R, et al. Increased admission for alcohol dependence after gastric bypass surgery compared with restrictive bariatric surgery. JAMA Surg. 2013;148(4):374-377.

13. Gearhardt AN, Corbin WR. Body mass index and alcohol consumption: family history of alcoholism as a moderator. Psychol Addict Behav. 2009;23(2):216-225.

14. Grucza RA, Krueger RF, Racette SB, et al. The emerging link between alcoholism risk and obesity in the United States. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2010;67(12):1301-1308.

15. Davis JF, Tracy AL, Schurdak JD, et al. Roux en y gastric bypass increases ethanol intake in the rat. Obes Surg. 2013;23(7):920-930.

16. Davis JF, Schurdak JD, Magrisso IJ, et al. Gastric bypass surgery attenuates ethanol consumption in ethanol-preferring rats. Biol Psychiatry. 2012;72(5):354-360.

18. Pepino MY, Okunade AL, Eagon JC, et al. Effect of Roux-en-Y gastric bypass surgery: converting 2 alcoholic drinks to 4. JAMA Surg. 2015

19. Changchien EM, Woodard GA, Hernandez-Boussard T, et al. Normal alcohol metabolism after gastric banding and sleeve gastrectomy: a case-cross-over trial. J Am Coll Surg. 2012;215(4):475-479.

22. Polston JE, Pritchett CE, Tomasko JM, et al. Roux-en-Y gastric bypass increases intravenous ethanol self-administration in dietary obese rats. PLoS ONE. 2013;8(12):e83741. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0083741.

26. Higgs ML, Wade T, Cescato M, et al. Differences between treatment seekers in an obese population: medical intervention vs. dietary restriction. J Behav Med. 1997;20(4):391-405.

35. Sutin AR, Stephan Y, Terracciano A. Weight discrimination and risk of mortality. Psychol Sci. 2015;26(11):1803-1811.

36. Sogg S, Gorman MJ. Interpersonal changes and challenges after weight loss surgery. Prim Psychiatry. 2008;15(8):61-66.

37. Yanos BR, Saules KK, Schuh LM, et al. Predictors of lowest weight and long-term weight regain among Roux-en-Y gastric bypass patients. Obes Surg. 2015;25(8):1364-1370.

40. van der Beek E, Te Riele W, Specken TF, et al. The impact of reconstructive procedures following bariatric surgery on patient well-being and quality of life. Obes Surg. 2010;20(1):36-41.

Maladaptive alcohol use has emerged as a risk for a subset of individuals who have undergone weight loss surgery (WLS); studies report they are vulnerable to consuming alcohol in greater quantities or more frequently.1,2 Estimates of the prevalence of “high-risk” or “hazardous” alcohol use after WLS range from 4% to 28%,3,4 while the prevalence of alcohol use meeting DSM-IV-TR5 criteria for alcohol use disorders (AUDs) hovers around 10%.6

Heavy alcohol users or patients who have active AUD at the time of WLS are at greater risk for continuation of these problems after surgery.2,6 For patients with a long-remitted history of AUD, the evidence regarding risk for post-WLS relapse is lacking, and some evidence suggests they may have better weight loss outcomes after WLS.7

However, approximately two-third of cases of post-WLS alcohol problems occur in patients who have had no history of such problems before surgery.5,8,9 Reported prevalence rates of new-onset alcohol problems range from 3% to 18%,6,9 with the modal finding being approximately 7% to 8%. New-onset alcohol problems appear to occur at a considerable latency after surgery. One study found little risk at 1 year post-surgery, but a significant increase in AUD symptoms at 2 years.6 Another study identified 3 years post-surgery as a high-risk time point,8 and yet another reported a linear increase in the risk for developing alcohol problems for at least 10 years after WLS.10

This article describes a group treatment protocol developed specifically for patients with post-WLS substance use disorder (SUD), and explores:

- risk factors and causal mechanisms of post-WLS AUDs

- weight stigma and emotional stressors

- the role of specialized treatment

- group treatment based on the Health at Every Size® (HAES)-oriented, trauma-informed and fat acceptance framework.

Post-WLS patients with alcohol problems may be a distinct phenotype among people with substance abuse issues. For this reason, they may have a need to address their experiences and issues specific to WLS as part of their alcohol treatment.

Etiology

Risk factors. Empirical findings have identified few predictors or risk factors for post-WLS SUD. These patients are more likely to be male and of a younger age.6 Notably, the vast majority of individuals reporting post-WLS alcohol problems have undergone Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (RYGB), rather than other WLS procedures, such as the laparoscopic adjustable gastric band,6,11 suggesting some physiological mechanism specific to RYGB.

Other potential predictors of postoperative alcohol problems include a pre-operative history of depression, generalized anxiety disorder, smoking, and/or recreational drug use.3,6 Likewise, patients with depression or anxiety disorder symptoms after surgery also may be at higher risk for postoperative alcohol problems.4 The evidence of an association between postoperative weight outcomes and post-WLS alcohol problems is mixed.3,12 Interestingly, patients who had no personal history of substance abuse but who have a family history may have a higher risk of new-onset alcohol problems after surgery.9,12

Causal mechanisms. The etiology of post-WLS alcohol problems is not well understood. If anything, epidemiological data suggest that larger-bodied individuals tend to consume lower levels of alcohol and have lower rates of AUD than individuals in the general population with thinner bodies.13 However, an association has been found between a family history of SUD, but not a personal history, and being large.14 This suggests a shared etiological pathway between addiction and being “overweight,” of which the onset of AUD after RYGB may be a manifestation.

Human and animal studies have shown that WLS may affect alcohol use differently in specific subgroups. Studies have shown that wild-type rats greatly increase their consumption of, or operant responding for, alcohol after RYGB,15 while genetically “alcohol-preferring” rats decrease consumption of, or responding for, alcohol after RYGB.16 A human study likewise found some patients decreased alcohol use or experienced improvement of or remission of AUD symptoms after WLS.4 Combined with the finding that a family history of substance abuse is related to risk for post-operative AUD, these data suggest a potential genetic vulnerability or protection in some individuals.

Turning to potential psychosocial explanations, the lay media has popularized the concepts of “addiction transfer,” or “transfer addiction,”12 with the implication that some patients, who had a preoperative history of “food addiction,” transfer that “addiction” after surgery to substances of abuse.

However, the “addiction transfer” model has a number of flaws:

- it is stigmatizing, because it assumes the patient possesses an innate, chronic, and inalterable pathology

- it relies upon the validity of the controversial construct of “food addiction,” a construct of mixed scientific evidence.17

Further, our knowledge of post-WLS SUD argues against “addiction transfer.” As noted, postoperative alcohol problems are more likely to develop years after surgery, rather than in the first few months afterward when eating is most significantly curtailed. Additionally, post-WLS alcohol problems are significantly more likely to occur after RYGB than other procedures, whereas the “addiction transfer” model would hypothesize that all WLS patients would be at equal risk for postoperative “addiction transfer,” because their eating is similarly affected after surgery.

Links to RYGB. Some clues to physiological mechanisms underlying alcohol problems after RYGB have been identified. After surgery, many RYGB patients report a quicker effect from a smaller amount of alcohol than was the case pre-surgery.18 Studies have demonstrated a number of changes in the pharmacodynamics of alcohol after RYGB not seen in other WLS procedures19:

- a much faster time to peak blood (or breath) alcohol content (BAC)

- significantly higher peak BAC

- a precipitous initial decline in perceived intoxication.18,20

Anatomical features of RYGB may explain such changes.8 However, an increased response to both IV alcohol and IV morphine after RYGB21,22 in rodents suggests that gastrointestinal tract changes are not solely responsible for changes in alcohol use. Emerging research reports that WLS has been found to cause alterations in brain reward pathways,23 which may be an additional contributor to changes in alcohol misuse after surgery.

However, even combined, pharmacokinetic and neurobiological factors cannot entirely explain new-onset alcohol problems after WLS; if they could, one would expect to see a much higher prevalence of this complication. Some psychosocial factors are likely involved as well.

Emotional stressors. One possibility involves a mismatch between post-WLS stressors and coping skills. After WLS, these patients face a multitude of challenges inherent in adjusting to changes in lifestyle, weight, body image, and social functioning, which most individuals would find daunting. These challenges become even more acute in the absence of appropriate psychoeducation, preparation, and intervention from qualified professionals. Individuals who lack effective and adaptive coping skills and supports may have a particularly heightened vulnerability to increased alcohol use in the setting of post-surgery changes in brain reward circuits and pharmacodynamics in alcohol metabolism. For example, one patient reported that her spouse’s pressure to “do something about her weight” was a significant factor in her decision to undergo surgery, but that her spouse was blaming and unsupportive when post-WLS complications developed. The patient believed that these experiences helped fuel development of her post-RYGB alcohol abuse.

Specialized treatment

The number of patients experiencing post-WLS alcohol problems likely will continue to grow, given that the risk of onset of has been shown increase over years. Already, post-WLS patients are proportionally overrepresented among substance abuse treatment populations.24 Empirically, however, we do not know yet if these patients need a different type of addiction treatment than patients who have not had WLS.

Some evidence suggests that post-WLS patients with alcohol problems may be a distinct phenotype within the general population with alcohol problems, as their presentations differ in several ways, including their demographics, alcohol use patterns, and premorbid functioning. A number of studies have found that, despite their increased pharmacodynamic sensitivity to alcohol, people with post-WLS AUDs actually consume a larger amount of alcohol on both typical and maximum drinking days than other individuals with AUDs.24 Additionally, although the median age of onset for AUD is around age 20,25 patients presenting with new-onset, post-WLS alcohol problems are usually in their late 30s, or even 40s or 50s. Further, many of these patients were quite high functioning before their alcohol problems, and are unlikely to identify with the cultural stereotype of a person with AUD (eg, homeless, unemployed), which may hamper or delay their own willingness to accept that they have a problem. These phenotypic differences suggest that post-WLS patients may require substance abuse treatment approaches tailored to their unique presentation. There are additional factors specific to the experiences of being larger-bodied and WLS that also may need to be addressed in specialized treatment for post-WLS addiction patients.

Weight stigma. By definition, patients who have undergone WLS have spent a significant portion of their lives inhabiting larger bodies, an experience that, in our culture, can produce adverse psychosocial effects. Compared with the general population, patients seeking WLS exhibit psychological distress equivalent to psychiatric patients.26 Weight stigma or weight bias—negative judgments directed toward people in larger bodies—is pervasive and continues to increase.27 Further, evidence suggests that, unlike almost all other stigmatized groups, people in larger bodies tend to internalize this stigma, holding an unfavorable attitude toward their own social group.28 Weight stigma impacts the well-being of people all along the weight spectrum, affecting many domains including educational achievements and classroom experiences, job opportunities, salaries, and medical care.27 Weight stigma increases the likelihood of bullying, teasing, and harassment for both adults and children.27 Weight bias has been associated with any number of adverse psychosocial effects, including symptoms of depression, anxiety, and eating pathology; poor body image; and a decrease in healthy self-care behaviors.29-33

Weight stigma makes it more difficult for people to enjoy physical activities, nourish their bodies, and manage stress, which contributes to poorer health outcomes and lower quality of life.33,34 For example, one study showed that, regardless of actual body mass index, people experiencing weight stigma have significantly increased risk of developing an illness or dying.35

Factors specific to WLS. WLS may lead to significant changes in eating habits, and some patients experience a sense of loss, particularly if eating represented one of their primary coping strategies—this may represent a heightened emotional vulnerability for developing AUD.

The fairly rapid and substantial weight loss that WLS produces can lead to sweeping changes in lifestyle, body image, and functional factors for many individuals. Patients often report profound changes, both positive and negative, in their relationships and interactions not only with people in their support network, but also with strangers.36

After the first year or 2 post-WLS, it is fairly common for patients to regain some weight, sometimes in significant amounts.37 This can lead to a sense of “failure.” Life stressors, including difficulties in important relationships, can further add to patients’ vulnerability. For example, one patient noticed that when she was at her thinnest after WLS, drivers were more likely to stop for her when she crossed the street, which pleased but also angered her because they hadn’t extended the same courtesy before WLS. After she regained a significant amount of weight, she began to notice drivers stopping for her less and less frequently. This took her back to her previous feelings of being ignored but now with the certainty that she would be treated better if she were thinner.

Patients also may experience ambivalence about changes in their body size. One might expect that body image would improve after weight loss, but the evidence is mixed.38 Although there is some evidence that body image improves in the short term after WLS,38 other research indicates that body image does not improve with weight loss.39 However, the evidence is clear that the appearance of excess skin after weight loss worsens some patients’ body image.40

To date, there has been no research examining treatment modalities for this population. Because experiences common to individuals who have had WLS could play a role in the development of AUD after surgery, it is intuitive that it would be important to address these factors when designing a treatment plan for post-WLS substance abuse.

Group treatment approach

In 2013, in response to the increase in rates of post-WLS addictions presenting to West End Clinic, an outpatient dual-diagnosis (addiction and psychiatry) service at Massachusetts General Hospital, a specialized treatment group was developed. Nine patients have enrolled since October 2013.

The Post-WLS Addictions Group (PWAG) was designed to be HAES-oriented, trauma-informed, and run within a fat acceptance framework. The HAES model prioritizes a weight-neutral approach that sees health and well-being as multifaceted. This approach directs both patient and clinician to focus on improving health behaviors and reducing internalized weight bias, while building a supportive community that buffers against external cultural weight bias.41

Trauma-informed care42 emphasizes the principles of safety, trustworthiness, and transparency; peer support; collaboration and mutuality; empowerment; and awareness of cultural, historical, and gender issues. In the context of PWAG, weight stigma is conceptualized as a traumatic experience.43 The fat acceptance approach promotes a culture that accepts people of every size with dignity and equality in all aspects of life.44

Self-care emphasis. The HAES model encourages patients to allow their bodies to determine what weight to settle at, and to focus on sustainable health-enhancing behaviors rather than weight loss. Patients who asked about the PWAG were told that this group would not explicitly support, or even encourage, continued pursuit of weight loss per se, but instead would assist patients with relapse prevention, mindful eating, improving self-care, and ongoing stress management. Moving away from a focus on weight loss and toward improvement of self-care skills allowed patients to focus on behaviors and outcomes over which they had more direct control and were more likely to yield immediate benefits.

All of the PWAG group members were in early recovery from an SUD, with a minimum of 4 weeks of abstinence; all had at least 1 co-occurring mental health diagnosis. A licensed independent clinical social worker (LICSW) and a physician familiar with bariatric surgery ran the sessions. The group met weekly for 1 hour. The 8 weekly sessions included both psychoeducation and discussion, with each session covering different topics (Table). The first 20 minutes of each session were devoted to an educational presentation; the remaining 40 minutes for reflection and discussion. In sessions 2 through 8, participants were asked about any recent use or cravings, and problem-solving techniques were employed as needed.

The PWAG group leader herself is a large person who modeled fat acceptance and follows the HAES approach; she led the group using both this experience and her specialized clinical training. As is the case with other addictions recovery treatment modalities, clinicians with lived experience may add a valuable component to both the program design and patient experience.

After the first 8 sessions, all members expressed interest in continuing as an ongoing relapse prevention and HAES support group, and they reported that meeting regularly was very helpful. The group continued with the LICSW alone, who continued to share HAES-oriented and fat acceptance information and resources that group members requested specifically. Over time, new members joined following an individual orientation session with the group leader, and the group has revisited each of the psychoeducational topics repeatedly, though not in a formally structured way.

Process and observations. Participants described high levels of excitement and hopefulness about being in a group with other WLS patients who had developed SUDs. They had a particular interest in reviewing medical/anatomical information about WLS and understanding more about the potential reasons for the elevated risk for developing SUD following WLS. Discussions regarding weight stigma proved to be quite emotional; most participants reported that this material readily related to their own experiences with weight stigma, but they had never discussed these ideas before.

Participants explored the role that grief, loss, guilt, and shame had in the decision to have WLS, the development of SUDs, weight regain or medical complications from the surgery or from substance abuse, career and relationship changes, and worsened body image. Another theme that emerged was the various reasons that prompted the members have WLS that they may not have been conscious of, or willing to discuss with others, such as pressure from a spouse, fears of remaining single due to their size, and a desire to finally “fit in.”

Repeatedly, group members expressed how satisfied and emotionally validated they felt being with people with similar experiences. Most of them had felt alone. They reported a belief that “everyone else” who had WLS was doing well, and that they were the exceptions. Such beliefs and emotions increased the risk of relapse and decreased participants’ ability to develop more positive coping strategies and self-care skills.

Participants reported that feeling less alone, understanding how stigma impacts health and well-being, and focusing on the general benefits of good self-care rather than the pursuit of weight loss were particularly helpful. The HAES and fat acceptance approaches have given group members new ways to think about their bodies and decreased shame. Several group members reported that if they had learned about the HAES approach prior to having a WLS, they might have made a different decision about having surgery, or at least might have been better prepared to handle the emotional and psychological challenges after WLS.

Although evidence for post-WLS addictions is fairly robust, causal mechanisms are not well understood, and research identifying specific risk factors is lacking. Because post-WLS patients with addictions seem to represent a specific phenotype, specialized treatment might be indicated. Future research will be needed to determine optimal treatment approaches for post-WLS addictions. However, a number of aspects are likely to be important. For example, it is likely that unaddressed experiences of weight stigma contribute to challenges, including substance abuse, after WLS; therefore, clinicians involved in the care of individuals presenting with post-WLS SUD should be knowledgeable about weight stigma and how to address it. Because of the specific nature of post-WLS addictions, patients often feel alone and isolated, and seem to benefit from the specialized group setting. We note that the PWAG group leader is herself a large person who models fat acceptance and follows the HAES approach, and therefore led the group using this experience and her specialized clinical training. As with other addiction recovery treatment modalities, clinicians who have lived the experience can add a valuable component to the program design and patient experience.

Maladaptive alcohol use has emerged as a risk for a subset of individuals who have undergone weight loss surgery (WLS); studies report they are vulnerable to consuming alcohol in greater quantities or more frequently.1,2 Estimates of the prevalence of “high-risk” or “hazardous” alcohol use after WLS range from 4% to 28%,3,4 while the prevalence of alcohol use meeting DSM-IV-TR5 criteria for alcohol use disorders (AUDs) hovers around 10%.6

Heavy alcohol users or patients who have active AUD at the time of WLS are at greater risk for continuation of these problems after surgery.2,6 For patients with a long-remitted history of AUD, the evidence regarding risk for post-WLS relapse is lacking, and some evidence suggests they may have better weight loss outcomes after WLS.7

However, approximately two-third of cases of post-WLS alcohol problems occur in patients who have had no history of such problems before surgery.5,8,9 Reported prevalence rates of new-onset alcohol problems range from 3% to 18%,6,9 with the modal finding being approximately 7% to 8%. New-onset alcohol problems appear to occur at a considerable latency after surgery. One study found little risk at 1 year post-surgery, but a significant increase in AUD symptoms at 2 years.6 Another study identified 3 years post-surgery as a high-risk time point,8 and yet another reported a linear increase in the risk for developing alcohol problems for at least 10 years after WLS.10

This article describes a group treatment protocol developed specifically for patients with post-WLS substance use disorder (SUD), and explores:

- risk factors and causal mechanisms of post-WLS AUDs

- weight stigma and emotional stressors

- the role of specialized treatment

- group treatment based on the Health at Every Size® (HAES)-oriented, trauma-informed and fat acceptance framework.

Post-WLS patients with alcohol problems may be a distinct phenotype among people with substance abuse issues. For this reason, they may have a need to address their experiences and issues specific to WLS as part of their alcohol treatment.

Etiology

Risk factors. Empirical findings have identified few predictors or risk factors for post-WLS SUD. These patients are more likely to be male and of a younger age.6 Notably, the vast majority of individuals reporting post-WLS alcohol problems have undergone Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (RYGB), rather than other WLS procedures, such as the laparoscopic adjustable gastric band,6,11 suggesting some physiological mechanism specific to RYGB.

Other potential predictors of postoperative alcohol problems include a pre-operative history of depression, generalized anxiety disorder, smoking, and/or recreational drug use.3,6 Likewise, patients with depression or anxiety disorder symptoms after surgery also may be at higher risk for postoperative alcohol problems.4 The evidence of an association between postoperative weight outcomes and post-WLS alcohol problems is mixed.3,12 Interestingly, patients who had no personal history of substance abuse but who have a family history may have a higher risk of new-onset alcohol problems after surgery.9,12

Causal mechanisms. The etiology of post-WLS alcohol problems is not well understood. If anything, epidemiological data suggest that larger-bodied individuals tend to consume lower levels of alcohol and have lower rates of AUD than individuals in the general population with thinner bodies.13 However, an association has been found between a family history of SUD, but not a personal history, and being large.14 This suggests a shared etiological pathway between addiction and being “overweight,” of which the onset of AUD after RYGB may be a manifestation.

Human and animal studies have shown that WLS may affect alcohol use differently in specific subgroups. Studies have shown that wild-type rats greatly increase their consumption of, or operant responding for, alcohol after RYGB,15 while genetically “alcohol-preferring” rats decrease consumption of, or responding for, alcohol after RYGB.16 A human study likewise found some patients decreased alcohol use or experienced improvement of or remission of AUD symptoms after WLS.4 Combined with the finding that a family history of substance abuse is related to risk for post-operative AUD, these data suggest a potential genetic vulnerability or protection in some individuals.

Turning to potential psychosocial explanations, the lay media has popularized the concepts of “addiction transfer,” or “transfer addiction,”12 with the implication that some patients, who had a preoperative history of “food addiction,” transfer that “addiction” after surgery to substances of abuse.

However, the “addiction transfer” model has a number of flaws:

- it is stigmatizing, because it assumes the patient possesses an innate, chronic, and inalterable pathology

- it relies upon the validity of the controversial construct of “food addiction,” a construct of mixed scientific evidence.17

Further, our knowledge of post-WLS SUD argues against “addiction transfer.” As noted, postoperative alcohol problems are more likely to develop years after surgery, rather than in the first few months afterward when eating is most significantly curtailed. Additionally, post-WLS alcohol problems are significantly more likely to occur after RYGB than other procedures, whereas the “addiction transfer” model would hypothesize that all WLS patients would be at equal risk for postoperative “addiction transfer,” because their eating is similarly affected after surgery.

Links to RYGB. Some clues to physiological mechanisms underlying alcohol problems after RYGB have been identified. After surgery, many RYGB patients report a quicker effect from a smaller amount of alcohol than was the case pre-surgery.18 Studies have demonstrated a number of changes in the pharmacodynamics of alcohol after RYGB not seen in other WLS procedures19:

- a much faster time to peak blood (or breath) alcohol content (BAC)

- significantly higher peak BAC

- a precipitous initial decline in perceived intoxication.18,20

Anatomical features of RYGB may explain such changes.8 However, an increased response to both IV alcohol and IV morphine after RYGB21,22 in rodents suggests that gastrointestinal tract changes are not solely responsible for changes in alcohol use. Emerging research reports that WLS has been found to cause alterations in brain reward pathways,23 which may be an additional contributor to changes in alcohol misuse after surgery.

However, even combined, pharmacokinetic and neurobiological factors cannot entirely explain new-onset alcohol problems after WLS; if they could, one would expect to see a much higher prevalence of this complication. Some psychosocial factors are likely involved as well.

Emotional stressors. One possibility involves a mismatch between post-WLS stressors and coping skills. After WLS, these patients face a multitude of challenges inherent in adjusting to changes in lifestyle, weight, body image, and social functioning, which most individuals would find daunting. These challenges become even more acute in the absence of appropriate psychoeducation, preparation, and intervention from qualified professionals. Individuals who lack effective and adaptive coping skills and supports may have a particularly heightened vulnerability to increased alcohol use in the setting of post-surgery changes in brain reward circuits and pharmacodynamics in alcohol metabolism. For example, one patient reported that her spouse’s pressure to “do something about her weight” was a significant factor in her decision to undergo surgery, but that her spouse was blaming and unsupportive when post-WLS complications developed. The patient believed that these experiences helped fuel development of her post-RYGB alcohol abuse.

Specialized treatment

The number of patients experiencing post-WLS alcohol problems likely will continue to grow, given that the risk of onset of has been shown increase over years. Already, post-WLS patients are proportionally overrepresented among substance abuse treatment populations.24 Empirically, however, we do not know yet if these patients need a different type of addiction treatment than patients who have not had WLS.

Some evidence suggests that post-WLS patients with alcohol problems may be a distinct phenotype within the general population with alcohol problems, as their presentations differ in several ways, including their demographics, alcohol use patterns, and premorbid functioning. A number of studies have found that, despite their increased pharmacodynamic sensitivity to alcohol, people with post-WLS AUDs actually consume a larger amount of alcohol on both typical and maximum drinking days than other individuals with AUDs.24 Additionally, although the median age of onset for AUD is around age 20,25 patients presenting with new-onset, post-WLS alcohol problems are usually in their late 30s, or even 40s or 50s. Further, many of these patients were quite high functioning before their alcohol problems, and are unlikely to identify with the cultural stereotype of a person with AUD (eg, homeless, unemployed), which may hamper or delay their own willingness to accept that they have a problem. These phenotypic differences suggest that post-WLS patients may require substance abuse treatment approaches tailored to their unique presentation. There are additional factors specific to the experiences of being larger-bodied and WLS that also may need to be addressed in specialized treatment for post-WLS addiction patients.

Weight stigma. By definition, patients who have undergone WLS have spent a significant portion of their lives inhabiting larger bodies, an experience that, in our culture, can produce adverse psychosocial effects. Compared with the general population, patients seeking WLS exhibit psychological distress equivalent to psychiatric patients.26 Weight stigma or weight bias—negative judgments directed toward people in larger bodies—is pervasive and continues to increase.27 Further, evidence suggests that, unlike almost all other stigmatized groups, people in larger bodies tend to internalize this stigma, holding an unfavorable attitude toward their own social group.28 Weight stigma impacts the well-being of people all along the weight spectrum, affecting many domains including educational achievements and classroom experiences, job opportunities, salaries, and medical care.27 Weight stigma increases the likelihood of bullying, teasing, and harassment for both adults and children.27 Weight bias has been associated with any number of adverse psychosocial effects, including symptoms of depression, anxiety, and eating pathology; poor body image; and a decrease in healthy self-care behaviors.29-33

Weight stigma makes it more difficult for people to enjoy physical activities, nourish their bodies, and manage stress, which contributes to poorer health outcomes and lower quality of life.33,34 For example, one study showed that, regardless of actual body mass index, people experiencing weight stigma have significantly increased risk of developing an illness or dying.35

Factors specific to WLS. WLS may lead to significant changes in eating habits, and some patients experience a sense of loss, particularly if eating represented one of their primary coping strategies—this may represent a heightened emotional vulnerability for developing AUD.

The fairly rapid and substantial weight loss that WLS produces can lead to sweeping changes in lifestyle, body image, and functional factors for many individuals. Patients often report profound changes, both positive and negative, in their relationships and interactions not only with people in their support network, but also with strangers.36

After the first year or 2 post-WLS, it is fairly common for patients to regain some weight, sometimes in significant amounts.37 This can lead to a sense of “failure.” Life stressors, including difficulties in important relationships, can further add to patients’ vulnerability. For example, one patient noticed that when she was at her thinnest after WLS, drivers were more likely to stop for her when she crossed the street, which pleased but also angered her because they hadn’t extended the same courtesy before WLS. After she regained a significant amount of weight, she began to notice drivers stopping for her less and less frequently. This took her back to her previous feelings of being ignored but now with the certainty that she would be treated better if she were thinner.

Patients also may experience ambivalence about changes in their body size. One might expect that body image would improve after weight loss, but the evidence is mixed.38 Although there is some evidence that body image improves in the short term after WLS,38 other research indicates that body image does not improve with weight loss.39 However, the evidence is clear that the appearance of excess skin after weight loss worsens some patients’ body image.40

To date, there has been no research examining treatment modalities for this population. Because experiences common to individuals who have had WLS could play a role in the development of AUD after surgery, it is intuitive that it would be important to address these factors when designing a treatment plan for post-WLS substance abuse.

Group treatment approach

In 2013, in response to the increase in rates of post-WLS addictions presenting to West End Clinic, an outpatient dual-diagnosis (addiction and psychiatry) service at Massachusetts General Hospital, a specialized treatment group was developed. Nine patients have enrolled since October 2013.

The Post-WLS Addictions Group (PWAG) was designed to be HAES-oriented, trauma-informed, and run within a fat acceptance framework. The HAES model prioritizes a weight-neutral approach that sees health and well-being as multifaceted. This approach directs both patient and clinician to focus on improving health behaviors and reducing internalized weight bias, while building a supportive community that buffers against external cultural weight bias.41

Trauma-informed care42 emphasizes the principles of safety, trustworthiness, and transparency; peer support; collaboration and mutuality; empowerment; and awareness of cultural, historical, and gender issues. In the context of PWAG, weight stigma is conceptualized as a traumatic experience.43 The fat acceptance approach promotes a culture that accepts people of every size with dignity and equality in all aspects of life.44

Self-care emphasis. The HAES model encourages patients to allow their bodies to determine what weight to settle at, and to focus on sustainable health-enhancing behaviors rather than weight loss. Patients who asked about the PWAG were told that this group would not explicitly support, or even encourage, continued pursuit of weight loss per se, but instead would assist patients with relapse prevention, mindful eating, improving self-care, and ongoing stress management. Moving away from a focus on weight loss and toward improvement of self-care skills allowed patients to focus on behaviors and outcomes over which they had more direct control and were more likely to yield immediate benefits.

All of the PWAG group members were in early recovery from an SUD, with a minimum of 4 weeks of abstinence; all had at least 1 co-occurring mental health diagnosis. A licensed independent clinical social worker (LICSW) and a physician familiar with bariatric surgery ran the sessions. The group met weekly for 1 hour. The 8 weekly sessions included both psychoeducation and discussion, with each session covering different topics (Table). The first 20 minutes of each session were devoted to an educational presentation; the remaining 40 minutes for reflection and discussion. In sessions 2 through 8, participants were asked about any recent use or cravings, and problem-solving techniques were employed as needed.

The PWAG group leader herself is a large person who modeled fat acceptance and follows the HAES approach; she led the group using both this experience and her specialized clinical training. As is the case with other addictions recovery treatment modalities, clinicians with lived experience may add a valuable component to both the program design and patient experience.

After the first 8 sessions, all members expressed interest in continuing as an ongoing relapse prevention and HAES support group, and they reported that meeting regularly was very helpful. The group continued with the LICSW alone, who continued to share HAES-oriented and fat acceptance information and resources that group members requested specifically. Over time, new members joined following an individual orientation session with the group leader, and the group has revisited each of the psychoeducational topics repeatedly, though not in a formally structured way.

Process and observations. Participants described high levels of excitement and hopefulness about being in a group with other WLS patients who had developed SUDs. They had a particular interest in reviewing medical/anatomical information about WLS and understanding more about the potential reasons for the elevated risk for developing SUD following WLS. Discussions regarding weight stigma proved to be quite emotional; most participants reported that this material readily related to their own experiences with weight stigma, but they had never discussed these ideas before.

Participants explored the role that grief, loss, guilt, and shame had in the decision to have WLS, the development of SUDs, weight regain or medical complications from the surgery or from substance abuse, career and relationship changes, and worsened body image. Another theme that emerged was the various reasons that prompted the members have WLS that they may not have been conscious of, or willing to discuss with others, such as pressure from a spouse, fears of remaining single due to their size, and a desire to finally “fit in.”

Repeatedly, group members expressed how satisfied and emotionally validated they felt being with people with similar experiences. Most of them had felt alone. They reported a belief that “everyone else” who had WLS was doing well, and that they were the exceptions. Such beliefs and emotions increased the risk of relapse and decreased participants’ ability to develop more positive coping strategies and self-care skills.

Participants reported that feeling less alone, understanding how stigma impacts health and well-being, and focusing on the general benefits of good self-care rather than the pursuit of weight loss were particularly helpful. The HAES and fat acceptance approaches have given group members new ways to think about their bodies and decreased shame. Several group members reported that if they had learned about the HAES approach prior to having a WLS, they might have made a different decision about having surgery, or at least might have been better prepared to handle the emotional and psychological challenges after WLS.

Although evidence for post-WLS addictions is fairly robust, causal mechanisms are not well understood, and research identifying specific risk factors is lacking. Because post-WLS patients with addictions seem to represent a specific phenotype, specialized treatment might be indicated. Future research will be needed to determine optimal treatment approaches for post-WLS addictions. However, a number of aspects are likely to be important. For example, it is likely that unaddressed experiences of weight stigma contribute to challenges, including substance abuse, after WLS; therefore, clinicians involved in the care of individuals presenting with post-WLS SUD should be knowledgeable about weight stigma and how to address it. Because of the specific nature of post-WLS addictions, patients often feel alone and isolated, and seem to benefit from the specialized group setting. We note that the PWAG group leader is herself a large person who models fat acceptance and follows the HAES approach, and therefore led the group using this experience and her specialized clinical training. As with other addiction recovery treatment modalities, clinicians who have lived the experience can add a valuable component to the program design and patient experience.

2. Lent MR, Hayes SM, Wood GC, et al. Smoking and alcohol use in gastric bypass patients. Eat Behav. 2013;14(4):460-463.

4. Wee CC, Mukamal KJ, Huskey KW, et al. High-risk alcohol use after weight loss surgery. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2014;10(3):508-513.

5. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 4th, text rev. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2000.

6. King WC, Chen JY, Mitchell JE, et al. Prevalence of alcohol use disorders before and after bariatric surgery. JAMA. 2012;307(23):2516-2525.

9. Ivezaj V, Saules KK, Schuh LM. New-onset substance use disorder after gastric bypass surgery: rates and associated characteristics. Obes Surg. 2014;24(11):1975-1980.

10. Svensson PA, Anveden Å, Romeo S, et al. Alcohol consumption and alcohol problems after bariatric surgery in the Swedish obese subjects study. Obesity. 2013;21(12):2444-2451.

11. Ostlund MP, Backman O, Marsk R, et al. Increased admission for alcohol dependence after gastric bypass surgery compared with restrictive bariatric surgery. JAMA Surg. 2013;148(4):374-377.

13. Gearhardt AN, Corbin WR. Body mass index and alcohol consumption: family history of alcoholism as a moderator. Psychol Addict Behav. 2009;23(2):216-225.

14. Grucza RA, Krueger RF, Racette SB, et al. The emerging link between alcoholism risk and obesity in the United States. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2010;67(12):1301-1308.

15. Davis JF, Tracy AL, Schurdak JD, et al. Roux en y gastric bypass increases ethanol intake in the rat. Obes Surg. 2013;23(7):920-930.

16. Davis JF, Schurdak JD, Magrisso IJ, et al. Gastric bypass surgery attenuates ethanol consumption in ethanol-preferring rats. Biol Psychiatry. 2012;72(5):354-360.

18. Pepino MY, Okunade AL, Eagon JC, et al. Effect of Roux-en-Y gastric bypass surgery: converting 2 alcoholic drinks to 4. JAMA Surg. 2015

19. Changchien EM, Woodard GA, Hernandez-Boussard T, et al. Normal alcohol metabolism after gastric banding and sleeve gastrectomy: a case-cross-over trial. J Am Coll Surg. 2012;215(4):475-479.

22. Polston JE, Pritchett CE, Tomasko JM, et al. Roux-en-Y gastric bypass increases intravenous ethanol self-administration in dietary obese rats. PLoS ONE. 2013;8(12):e83741. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0083741.

26. Higgs ML, Wade T, Cescato M, et al. Differences between treatment seekers in an obese population: medical intervention vs. dietary restriction. J Behav Med. 1997;20(4):391-405.

35. Sutin AR, Stephan Y, Terracciano A. Weight discrimination and risk of mortality. Psychol Sci. 2015;26(11):1803-1811.

36. Sogg S, Gorman MJ. Interpersonal changes and challenges after weight loss surgery. Prim Psychiatry. 2008;15(8):61-66.

37. Yanos BR, Saules KK, Schuh LM, et al. Predictors of lowest weight and long-term weight regain among Roux-en-Y gastric bypass patients. Obes Surg. 2015;25(8):1364-1370.

40. van der Beek E, Te Riele W, Specken TF, et al. The impact of reconstructive procedures following bariatric surgery on patient well-being and quality of life. Obes Surg. 2010;20(1):36-41.

2. Lent MR, Hayes SM, Wood GC, et al. Smoking and alcohol use in gastric bypass patients. Eat Behav. 2013;14(4):460-463.

4. Wee CC, Mukamal KJ, Huskey KW, et al. High-risk alcohol use after weight loss surgery. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2014;10(3):508-513.

5. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 4th, text rev. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2000.

6. King WC, Chen JY, Mitchell JE, et al. Prevalence of alcohol use disorders before and after bariatric surgery. JAMA. 2012;307(23):2516-2525.

9. Ivezaj V, Saules KK, Schuh LM. New-onset substance use disorder after gastric bypass surgery: rates and associated characteristics. Obes Surg. 2014;24(11):1975-1980.

10. Svensson PA, Anveden Å, Romeo S, et al. Alcohol consumption and alcohol problems after bariatric surgery in the Swedish obese subjects study. Obesity. 2013;21(12):2444-2451.

11. Ostlund MP, Backman O, Marsk R, et al. Increased admission for alcohol dependence after gastric bypass surgery compared with restrictive bariatric surgery. JAMA Surg. 2013;148(4):374-377.

13. Gearhardt AN, Corbin WR. Body mass index and alcohol consumption: family history of alcoholism as a moderator. Psychol Addict Behav. 2009;23(2):216-225.

14. Grucza RA, Krueger RF, Racette SB, et al. The emerging link between alcoholism risk and obesity in the United States. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2010;67(12):1301-1308.

15. Davis JF, Tracy AL, Schurdak JD, et al. Roux en y gastric bypass increases ethanol intake in the rat. Obes Surg. 2013;23(7):920-930.

16. Davis JF, Schurdak JD, Magrisso IJ, et al. Gastric bypass surgery attenuates ethanol consumption in ethanol-preferring rats. Biol Psychiatry. 2012;72(5):354-360.

18. Pepino MY, Okunade AL, Eagon JC, et al. Effect of Roux-en-Y gastric bypass surgery: converting 2 alcoholic drinks to 4. JAMA Surg. 2015

19. Changchien EM, Woodard GA, Hernandez-Boussard T, et al. Normal alcohol metabolism after gastric banding and sleeve gastrectomy: a case-cross-over trial. J Am Coll Surg. 2012;215(4):475-479.

22. Polston JE, Pritchett CE, Tomasko JM, et al. Roux-en-Y gastric bypass increases intravenous ethanol self-administration in dietary obese rats. PLoS ONE. 2013;8(12):e83741. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0083741.

26. Higgs ML, Wade T, Cescato M, et al. Differences between treatment seekers in an obese population: medical intervention vs. dietary restriction. J Behav Med. 1997;20(4):391-405.

35. Sutin AR, Stephan Y, Terracciano A. Weight discrimination and risk of mortality. Psychol Sci. 2015;26(11):1803-1811.

36. Sogg S, Gorman MJ. Interpersonal changes and challenges after weight loss surgery. Prim Psychiatry. 2008;15(8):61-66.

37. Yanos BR, Saules KK, Schuh LM, et al. Predictors of lowest weight and long-term weight regain among Roux-en-Y gastric bypass patients. Obes Surg. 2015;25(8):1364-1370.

40. van der Beek E, Te Riele W, Specken TF, et al. The impact of reconstructive procedures following bariatric surgery on patient well-being and quality of life. Obes Surg. 2010;20(1):36-41.