User login

Does primary nocturnal enuresis affect childrens’ self-esteem?

Yes. Children with primary nocturnal enuresis often, but not always, score about 10% lower on standardized rating scales for self-esteem, or scores for symptoms similar to low self-esteem (sadness, anxiety, social fears, distress) than children without enuresis (strength of recommendation [SOR]: B, systematic review of cohort and case-control studies with some heterogenous results).

Enuretic children 8 to 9 years of age are less likely to have lower self-esteem than older children, ages 10 to 12 years (SOR: B, case-control study).

Successful treatment of primary nocturnal enuresis improves self-esteem ratings, probably to normal (SOR: B, randomized, controlled trial, prospective cohort, and case-control studies).

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

A systematic review including 4 case-control and 3 cohort studies of the impact of nocturnal enuresis on children and young people found that bedwetting was often, but not always, associated with lower self-esteem scores (or scores for symptoms similar to lower self-esteem) on standardized questionnaires.1 The studies defined self-esteem in various ways and used a variety of questionnaires to measure it, so direct comparisons weren’t possible.

The first case-control study in the review found that enuretic older children (10-12 years) and girls had lower self-esteem scores than younger children (8-9 years) and boys. The second case-control study reported lower self-esteem scores on only 1 of 3 assessment instruments.

The third case-control study, which compared self-esteem scores in enuretic children with scores for children who had asthma and heart disease, found that enuresis was associated with the lowest self-esteem. The final case-control study reported that young adolescents with enuresis were more likely to suffer “angry distress.”

The first cohort study in the systematic review found a significantly higher incidence of sadness, anxiety, and social fears in children with enuresis than in children without and reported that 65% were “not happy” about having enuresis.

In the second cohort study, children with more severe enuresis, and girls, had significantly worse self-esteem scores than children with mild enuresis or boys (actual scores and some statistics not supplied), although these findings weren’t replicated on the second standardized scale that the investigators used.

The third cohort study reported that 37% of approximately 800 children with enuresis rated it “really difficult,” on a 4-point Likert scale.

How enuresis treatment affects self-esteem

The same systematic review, plus 2 additional studies, demonstrated that successful treatment of enuresis improves self-esteem scores, likely to normal.1-3 A randomized controlled trial found that treatment improved self-esteem scores by about 5%; children with the greatest treatment success showed the largest improvement (no statistics supplied).2

In a prospective cohort study, treated children demonstrated about a 30% improvement in scores measuring anxiety, depression, and internal distress.3 A case-control study in the systematic review also found about a 30% improvement in self-esteem scores among successfully treated children (both boys and girls) and a return to nonenuretic norms.1 Scores for unsuccessfully treated children didn’t improve.

RECOMMENDATIONS

A guideline on the management of bedwetting from the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (now called the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence) says that enuresis can have a deep impact on a child’s behavior and emotional well-being and that treatment has a positive effect on self-esteem.4

The Evidence-Based Medicine guidelines for enuresis in a child5 say that enuresis as such does not indicate a psychological disturbance and that psychotherapy may be useful when enuresis is associated with significant problems of self-esteem or behavior.

The American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry practice parameter for children with enuresis states that the psychological consequences of enuresis must be recognized and addressed with sensitivity during evaluation and management.6

1. National Clinical Guideline Centre (UK). Impact of bedwetting on children and young people and their families. In: Nocturnal Enuresis: The Management of Bedwetting in Children and Young People. London, UK: Royal College of Physicians; 2010. Available at: www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK62729/. Accessed January 24, 2014.

2. Moffatt ME, Kato C, Pless IB. Improvements in self-concept after treatment of nocturnal enuresis: randomized controlled trial. J Pediatr. 1987;110:647-652.

3. HiraSing RA, van Leerdam FJ, Bolk-Bennink LF, et al. Effect of dry bed training on behavioural problems in enuretic children. Acta Paediatr. 2002; 91:960-964.

4. Nunes VD, O’Flynn N, Evans J, et al; Guideline Development Group. Management of bedwetting in children and young people: summary of NICE guidance. BMJ. 2010;341:c5399.

5. Enuresis in a child. Evidence-Based Medicine Guidelines. Essential Evidence Plus [online database]. Available at: www.essentialevidenceplus.com/content/ebmg_ebm/633. Accessed January 24, 2014.

6. Fritz G, Rockney R; American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry Work Group on Quality Issues. Summary of the practice parameter for the assessment and treatment of children and adolescents with enuresis. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2004;43:123-125.

Yes. Children with primary nocturnal enuresis often, but not always, score about 10% lower on standardized rating scales for self-esteem, or scores for symptoms similar to low self-esteem (sadness, anxiety, social fears, distress) than children without enuresis (strength of recommendation [SOR]: B, systematic review of cohort and case-control studies with some heterogenous results).

Enuretic children 8 to 9 years of age are less likely to have lower self-esteem than older children, ages 10 to 12 years (SOR: B, case-control study).

Successful treatment of primary nocturnal enuresis improves self-esteem ratings, probably to normal (SOR: B, randomized, controlled trial, prospective cohort, and case-control studies).

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

A systematic review including 4 case-control and 3 cohort studies of the impact of nocturnal enuresis on children and young people found that bedwetting was often, but not always, associated with lower self-esteem scores (or scores for symptoms similar to lower self-esteem) on standardized questionnaires.1 The studies defined self-esteem in various ways and used a variety of questionnaires to measure it, so direct comparisons weren’t possible.

The first case-control study in the review found that enuretic older children (10-12 years) and girls had lower self-esteem scores than younger children (8-9 years) and boys. The second case-control study reported lower self-esteem scores on only 1 of 3 assessment instruments.

The third case-control study, which compared self-esteem scores in enuretic children with scores for children who had asthma and heart disease, found that enuresis was associated with the lowest self-esteem. The final case-control study reported that young adolescents with enuresis were more likely to suffer “angry distress.”

The first cohort study in the systematic review found a significantly higher incidence of sadness, anxiety, and social fears in children with enuresis than in children without and reported that 65% were “not happy” about having enuresis.

In the second cohort study, children with more severe enuresis, and girls, had significantly worse self-esteem scores than children with mild enuresis or boys (actual scores and some statistics not supplied), although these findings weren’t replicated on the second standardized scale that the investigators used.

The third cohort study reported that 37% of approximately 800 children with enuresis rated it “really difficult,” on a 4-point Likert scale.

How enuresis treatment affects self-esteem

The same systematic review, plus 2 additional studies, demonstrated that successful treatment of enuresis improves self-esteem scores, likely to normal.1-3 A randomized controlled trial found that treatment improved self-esteem scores by about 5%; children with the greatest treatment success showed the largest improvement (no statistics supplied).2

In a prospective cohort study, treated children demonstrated about a 30% improvement in scores measuring anxiety, depression, and internal distress.3 A case-control study in the systematic review also found about a 30% improvement in self-esteem scores among successfully treated children (both boys and girls) and a return to nonenuretic norms.1 Scores for unsuccessfully treated children didn’t improve.

RECOMMENDATIONS

A guideline on the management of bedwetting from the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (now called the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence) says that enuresis can have a deep impact on a child’s behavior and emotional well-being and that treatment has a positive effect on self-esteem.4

The Evidence-Based Medicine guidelines for enuresis in a child5 say that enuresis as such does not indicate a psychological disturbance and that psychotherapy may be useful when enuresis is associated with significant problems of self-esteem or behavior.

The American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry practice parameter for children with enuresis states that the psychological consequences of enuresis must be recognized and addressed with sensitivity during evaluation and management.6

Yes. Children with primary nocturnal enuresis often, but not always, score about 10% lower on standardized rating scales for self-esteem, or scores for symptoms similar to low self-esteem (sadness, anxiety, social fears, distress) than children without enuresis (strength of recommendation [SOR]: B, systematic review of cohort and case-control studies with some heterogenous results).

Enuretic children 8 to 9 years of age are less likely to have lower self-esteem than older children, ages 10 to 12 years (SOR: B, case-control study).

Successful treatment of primary nocturnal enuresis improves self-esteem ratings, probably to normal (SOR: B, randomized, controlled trial, prospective cohort, and case-control studies).

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

A systematic review including 4 case-control and 3 cohort studies of the impact of nocturnal enuresis on children and young people found that bedwetting was often, but not always, associated with lower self-esteem scores (or scores for symptoms similar to lower self-esteem) on standardized questionnaires.1 The studies defined self-esteem in various ways and used a variety of questionnaires to measure it, so direct comparisons weren’t possible.

The first case-control study in the review found that enuretic older children (10-12 years) and girls had lower self-esteem scores than younger children (8-9 years) and boys. The second case-control study reported lower self-esteem scores on only 1 of 3 assessment instruments.

The third case-control study, which compared self-esteem scores in enuretic children with scores for children who had asthma and heart disease, found that enuresis was associated with the lowest self-esteem. The final case-control study reported that young adolescents with enuresis were more likely to suffer “angry distress.”

The first cohort study in the systematic review found a significantly higher incidence of sadness, anxiety, and social fears in children with enuresis than in children without and reported that 65% were “not happy” about having enuresis.

In the second cohort study, children with more severe enuresis, and girls, had significantly worse self-esteem scores than children with mild enuresis or boys (actual scores and some statistics not supplied), although these findings weren’t replicated on the second standardized scale that the investigators used.

The third cohort study reported that 37% of approximately 800 children with enuresis rated it “really difficult,” on a 4-point Likert scale.

How enuresis treatment affects self-esteem

The same systematic review, plus 2 additional studies, demonstrated that successful treatment of enuresis improves self-esteem scores, likely to normal.1-3 A randomized controlled trial found that treatment improved self-esteem scores by about 5%; children with the greatest treatment success showed the largest improvement (no statistics supplied).2

In a prospective cohort study, treated children demonstrated about a 30% improvement in scores measuring anxiety, depression, and internal distress.3 A case-control study in the systematic review also found about a 30% improvement in self-esteem scores among successfully treated children (both boys and girls) and a return to nonenuretic norms.1 Scores for unsuccessfully treated children didn’t improve.

RECOMMENDATIONS

A guideline on the management of bedwetting from the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (now called the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence) says that enuresis can have a deep impact on a child’s behavior and emotional well-being and that treatment has a positive effect on self-esteem.4

The Evidence-Based Medicine guidelines for enuresis in a child5 say that enuresis as such does not indicate a psychological disturbance and that psychotherapy may be useful when enuresis is associated with significant problems of self-esteem or behavior.

The American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry practice parameter for children with enuresis states that the psychological consequences of enuresis must be recognized and addressed with sensitivity during evaluation and management.6

1. National Clinical Guideline Centre (UK). Impact of bedwetting on children and young people and their families. In: Nocturnal Enuresis: The Management of Bedwetting in Children and Young People. London, UK: Royal College of Physicians; 2010. Available at: www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK62729/. Accessed January 24, 2014.

2. Moffatt ME, Kato C, Pless IB. Improvements in self-concept after treatment of nocturnal enuresis: randomized controlled trial. J Pediatr. 1987;110:647-652.

3. HiraSing RA, van Leerdam FJ, Bolk-Bennink LF, et al. Effect of dry bed training on behavioural problems in enuretic children. Acta Paediatr. 2002; 91:960-964.

4. Nunes VD, O’Flynn N, Evans J, et al; Guideline Development Group. Management of bedwetting in children and young people: summary of NICE guidance. BMJ. 2010;341:c5399.

5. Enuresis in a child. Evidence-Based Medicine Guidelines. Essential Evidence Plus [online database]. Available at: www.essentialevidenceplus.com/content/ebmg_ebm/633. Accessed January 24, 2014.

6. Fritz G, Rockney R; American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry Work Group on Quality Issues. Summary of the practice parameter for the assessment and treatment of children and adolescents with enuresis. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2004;43:123-125.

1. National Clinical Guideline Centre (UK). Impact of bedwetting on children and young people and their families. In: Nocturnal Enuresis: The Management of Bedwetting in Children and Young People. London, UK: Royal College of Physicians; 2010. Available at: www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK62729/. Accessed January 24, 2014.

2. Moffatt ME, Kato C, Pless IB. Improvements in self-concept after treatment of nocturnal enuresis: randomized controlled trial. J Pediatr. 1987;110:647-652.

3. HiraSing RA, van Leerdam FJ, Bolk-Bennink LF, et al. Effect of dry bed training on behavioural problems in enuretic children. Acta Paediatr. 2002; 91:960-964.

4. Nunes VD, O’Flynn N, Evans J, et al; Guideline Development Group. Management of bedwetting in children and young people: summary of NICE guidance. BMJ. 2010;341:c5399.

5. Enuresis in a child. Evidence-Based Medicine Guidelines. Essential Evidence Plus [online database]. Available at: www.essentialevidenceplus.com/content/ebmg_ebm/633. Accessed January 24, 2014.

6. Fritz G, Rockney R; American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry Work Group on Quality Issues. Summary of the practice parameter for the assessment and treatment of children and adolescents with enuresis. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2004;43:123-125.

Evidence-based answers from the Family Physicians Inquiries Network

Is red-yeast rice a safe and effective alternative to statins?

Yes, but perhaps not the red-yeast rice extracts available in the United States.

In patients with known coronary artery disease and dyslipidemia (secondary prevention), therapy with red-yeast rice extract containing naturally-occurring lovastatin is associated with a 30% reduction in coronary heart disease (CHD) mortality and a 60% reduction in myocardial infarction (MI), similar to the effect of statin medications (strength of recommendation [SOR]: B, randomized controlled trials [RCTs] in China).

In patients older than 65 years with hypertension and a previous MI, the rate of adverse effects from lovastatin-containing red-yeast rice is 2.1% (SOR: B, RCT in China).

In patients with previous statin intolerance, the rates of myalgias and treatment discontinuation with lovastatin-containing red-yeast rice therapy are similar to either placebo or another statin (SOR: C, low-powered RCTs).

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) doesn’t allow lovastatin-containing red-yeast rice products on the US market; physicians should be aware that products purchased by patients online contain variable amounts of lovastatin.

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

Red-yeast rice is a Chinese dietary and medicinal product of yeast (Monascus purpureus) grown on rice. It contains a wide range of biologically active compounds, including lovastatin (monacolin K). The FDA has banned the sale of red-yeast rice products with more than trace amounts of lovastatin.1

Red-yeast rice beats placebo, similar to statins

A systematic review of 22 RCTs (N=6520), primarily conducted in China using 600 to 2400 mg red-yeast rice extract daily (lovastatin content 5-20 mg), assessed outcomes in patients with known CHD and dyslipidemia.2 In one trial of 4870 patients, users of red-yeast rice had significant reductions in CHD mortality (relative risk [RR]=0.69; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.54-0.89), incidence of MI (RR=0.39; 95% CI, 0.28-0.55), and revascularization (RR=0.67; 95% CI, 0.50-0.89) compared with placebo users.

However, when compared with statin therapy, red-yeast rice didn’t yield statistically significant differences in CHD mortality (2 trials, N=220; RR=0.26; 95% CI, 0.06-1.21), incidence of MI (1 trial, N=84; RR=0.95; 95% CI, 0.30-3.05) or revascularization (1 trial, N=84; RR=1.14; 95% CI, 0.38-3.46).

Red-yeast rice outperforms placebo in CHD and MI—but not stroke

A secondary analysis of an RCT evaluated the impact of red-yeast rice extract (600 mg twice a day) for 4.5 years on cardiovascular events and mortality in 1530 Chinese patients 60 years of age and older with hypertension and a previous MI.3 The lovastatin content of the red-yeast rice was 5 to 6.4 mg/d.

Compared with placebo, red-yeast rice was associated with a lower incidence of CHD events (RR=0.63; 95% CI, 0.36-0.83), nonfatal MI (RR=0.48; 95% CI, 0.37-0.71), and all-cause mortality (RR=0.65; 95% CI, 0.49-0.83) but not with a statistically significant difference in stroke (RR=0.63; 95% CI, 0.47-1.09) or cardiac revascularization (RR=0.68; 95% CI, 0.52-1.19).

Total adverse events in this study were similar for red-yeast rice and placebo (2.1% vs 1.2%, respectively; P>.05). They included gastrointestinal discomfort, allergic reactions, myalgias, edema, erectile dysfunction, and neuropsychological symptoms.

Red-yeast rice is similar to placebo or another statin in statin-induced myalgia

In a small community-based trial of 62 adults with dyslipidemia and a history of statin-induced myalgia, investigators randomized patients to receive either red-yeast rice extract at 1800 mg (with 3.1 mg lovastatin) or placebo twice daily for 24 weeks.4 Patients’ weekly self-reports of pain (on a 10-point scale) were skewed at baseline (1.4 in the red-yeast rice group vs 2.6 in the placebo group; P=.026) but similar at 12 weeks (1.4 with red-yeast rice vs 1.9 with placebo; P=.30) and 24 weeks (1.2 with red-yeast rice vs 2.0 with placebo; P=.120).

An RCT of 43 adults with dyslipidemia and history of statin intolerance compared red-yeast rice extract (2400 mg, with 10 mg lovastatin) with pravastatin (20 mg) dosed twice a day.5 At the end of 12 weeks, mean self-reported pain scores (on a 10-point scale) were similar (1.4 with red-yeast rice vs 1.1 with pravastatin; P=.82), as were discontinuation rates because of myalgia (5% with red-yeast rice vs 9% with pravastatin; P=.99).

RECOMMENDATIONS

A narrative review of alternative therapies for heart failure and hypercholesterolemia states that red yeast rice may be a cost-saving option for hypercholesterolemia in patients who can’t afford other medications (purchased mostly online, cost $8-$20/month for a dosage equivalent to lovastatin 20 mg/d).6

A ConsumerLab review of red yeast rice products available since the FDA ban in 2011 tested products marketed in the United States and found variable amounts of lovastatin.1,7 The group determined that labeling was a poor guide to lovastatin content, which ranged from 0 to 20 mg per daily dose, and that the products may not have been standardized. The group concluded that therapeutic effects weren’t predictable.

1. National Institutes of Health. Red yeast rice: An introduction. National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health Web site. Available at: http://nccam.nih.gov/health/redyeastrice. Accessed October 28, 2013.

2. Shang Q, Liu Z, Chen K, et al. A systematic review of xuezhikang, an extract from red yeast rice, for coronary heart disease complicated by dyslipidemia. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2012;2012:636547.

3. Li JJ, Lu ZL, Kou WR, et al. Beneficial impact of xuezhikang on cardiovascular events and mortality in elderly hypertensive patients with previous myocardial infarction from the China Coronary Secondary Prevention Study (CCSPS). J Clin Pharmacol. 2009;49:947-956.

4. Becker DJ, Gordon RY, Halbert SC, et al. Red yeast rice for dyslipidemia in statin-intolerant patients: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2009;150:830-839,

W147-W149.

5. Halbert SC, French B, Gordon RY, et al. Tolerability of red yeast rice (2,400 mg twice daily) versus pravastatin (20 mg twice daily) in patients with previous statin intolerance. Am J Cardiol. 2010;105:198-204.

6. Morelli V, Zoorob RJ. Alternative therapies: Part II. Congestive heart failure and hypercholesterolemia. Am Fam Physician. 2000;62:1325-1330.

7. Consumerlab.com. Product Review: Red yeast rice supplements review. ConsumerLab Web site. Available at: https://www.consumerlab.com/reviews/Red-Yeast-Rice-Supplements-Review/Red_Yeast_Rice. Accessed January 20, 2015.

Yes, but perhaps not the red-yeast rice extracts available in the United States.

In patients with known coronary artery disease and dyslipidemia (secondary prevention), therapy with red-yeast rice extract containing naturally-occurring lovastatin is associated with a 30% reduction in coronary heart disease (CHD) mortality and a 60% reduction in myocardial infarction (MI), similar to the effect of statin medications (strength of recommendation [SOR]: B, randomized controlled trials [RCTs] in China).

In patients older than 65 years with hypertension and a previous MI, the rate of adverse effects from lovastatin-containing red-yeast rice is 2.1% (SOR: B, RCT in China).

In patients with previous statin intolerance, the rates of myalgias and treatment discontinuation with lovastatin-containing red-yeast rice therapy are similar to either placebo or another statin (SOR: C, low-powered RCTs).

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) doesn’t allow lovastatin-containing red-yeast rice products on the US market; physicians should be aware that products purchased by patients online contain variable amounts of lovastatin.

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

Red-yeast rice is a Chinese dietary and medicinal product of yeast (Monascus purpureus) grown on rice. It contains a wide range of biologically active compounds, including lovastatin (monacolin K). The FDA has banned the sale of red-yeast rice products with more than trace amounts of lovastatin.1

Red-yeast rice beats placebo, similar to statins

A systematic review of 22 RCTs (N=6520), primarily conducted in China using 600 to 2400 mg red-yeast rice extract daily (lovastatin content 5-20 mg), assessed outcomes in patients with known CHD and dyslipidemia.2 In one trial of 4870 patients, users of red-yeast rice had significant reductions in CHD mortality (relative risk [RR]=0.69; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.54-0.89), incidence of MI (RR=0.39; 95% CI, 0.28-0.55), and revascularization (RR=0.67; 95% CI, 0.50-0.89) compared with placebo users.

However, when compared with statin therapy, red-yeast rice didn’t yield statistically significant differences in CHD mortality (2 trials, N=220; RR=0.26; 95% CI, 0.06-1.21), incidence of MI (1 trial, N=84; RR=0.95; 95% CI, 0.30-3.05) or revascularization (1 trial, N=84; RR=1.14; 95% CI, 0.38-3.46).

Red-yeast rice outperforms placebo in CHD and MI—but not stroke

A secondary analysis of an RCT evaluated the impact of red-yeast rice extract (600 mg twice a day) for 4.5 years on cardiovascular events and mortality in 1530 Chinese patients 60 years of age and older with hypertension and a previous MI.3 The lovastatin content of the red-yeast rice was 5 to 6.4 mg/d.

Compared with placebo, red-yeast rice was associated with a lower incidence of CHD events (RR=0.63; 95% CI, 0.36-0.83), nonfatal MI (RR=0.48; 95% CI, 0.37-0.71), and all-cause mortality (RR=0.65; 95% CI, 0.49-0.83) but not with a statistically significant difference in stroke (RR=0.63; 95% CI, 0.47-1.09) or cardiac revascularization (RR=0.68; 95% CI, 0.52-1.19).

Total adverse events in this study were similar for red-yeast rice and placebo (2.1% vs 1.2%, respectively; P>.05). They included gastrointestinal discomfort, allergic reactions, myalgias, edema, erectile dysfunction, and neuropsychological symptoms.

Red-yeast rice is similar to placebo or another statin in statin-induced myalgia

In a small community-based trial of 62 adults with dyslipidemia and a history of statin-induced myalgia, investigators randomized patients to receive either red-yeast rice extract at 1800 mg (with 3.1 mg lovastatin) or placebo twice daily for 24 weeks.4 Patients’ weekly self-reports of pain (on a 10-point scale) were skewed at baseline (1.4 in the red-yeast rice group vs 2.6 in the placebo group; P=.026) but similar at 12 weeks (1.4 with red-yeast rice vs 1.9 with placebo; P=.30) and 24 weeks (1.2 with red-yeast rice vs 2.0 with placebo; P=.120).

An RCT of 43 adults with dyslipidemia and history of statin intolerance compared red-yeast rice extract (2400 mg, with 10 mg lovastatin) with pravastatin (20 mg) dosed twice a day.5 At the end of 12 weeks, mean self-reported pain scores (on a 10-point scale) were similar (1.4 with red-yeast rice vs 1.1 with pravastatin; P=.82), as were discontinuation rates because of myalgia (5% with red-yeast rice vs 9% with pravastatin; P=.99).

RECOMMENDATIONS

A narrative review of alternative therapies for heart failure and hypercholesterolemia states that red yeast rice may be a cost-saving option for hypercholesterolemia in patients who can’t afford other medications (purchased mostly online, cost $8-$20/month for a dosage equivalent to lovastatin 20 mg/d).6

A ConsumerLab review of red yeast rice products available since the FDA ban in 2011 tested products marketed in the United States and found variable amounts of lovastatin.1,7 The group determined that labeling was a poor guide to lovastatin content, which ranged from 0 to 20 mg per daily dose, and that the products may not have been standardized. The group concluded that therapeutic effects weren’t predictable.

Yes, but perhaps not the red-yeast rice extracts available in the United States.

In patients with known coronary artery disease and dyslipidemia (secondary prevention), therapy with red-yeast rice extract containing naturally-occurring lovastatin is associated with a 30% reduction in coronary heart disease (CHD) mortality and a 60% reduction in myocardial infarction (MI), similar to the effect of statin medications (strength of recommendation [SOR]: B, randomized controlled trials [RCTs] in China).

In patients older than 65 years with hypertension and a previous MI, the rate of adverse effects from lovastatin-containing red-yeast rice is 2.1% (SOR: B, RCT in China).

In patients with previous statin intolerance, the rates of myalgias and treatment discontinuation with lovastatin-containing red-yeast rice therapy are similar to either placebo or another statin (SOR: C, low-powered RCTs).

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) doesn’t allow lovastatin-containing red-yeast rice products on the US market; physicians should be aware that products purchased by patients online contain variable amounts of lovastatin.

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

Red-yeast rice is a Chinese dietary and medicinal product of yeast (Monascus purpureus) grown on rice. It contains a wide range of biologically active compounds, including lovastatin (monacolin K). The FDA has banned the sale of red-yeast rice products with more than trace amounts of lovastatin.1

Red-yeast rice beats placebo, similar to statins

A systematic review of 22 RCTs (N=6520), primarily conducted in China using 600 to 2400 mg red-yeast rice extract daily (lovastatin content 5-20 mg), assessed outcomes in patients with known CHD and dyslipidemia.2 In one trial of 4870 patients, users of red-yeast rice had significant reductions in CHD mortality (relative risk [RR]=0.69; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.54-0.89), incidence of MI (RR=0.39; 95% CI, 0.28-0.55), and revascularization (RR=0.67; 95% CI, 0.50-0.89) compared with placebo users.

However, when compared with statin therapy, red-yeast rice didn’t yield statistically significant differences in CHD mortality (2 trials, N=220; RR=0.26; 95% CI, 0.06-1.21), incidence of MI (1 trial, N=84; RR=0.95; 95% CI, 0.30-3.05) or revascularization (1 trial, N=84; RR=1.14; 95% CI, 0.38-3.46).

Red-yeast rice outperforms placebo in CHD and MI—but not stroke

A secondary analysis of an RCT evaluated the impact of red-yeast rice extract (600 mg twice a day) for 4.5 years on cardiovascular events and mortality in 1530 Chinese patients 60 years of age and older with hypertension and a previous MI.3 The lovastatin content of the red-yeast rice was 5 to 6.4 mg/d.

Compared with placebo, red-yeast rice was associated with a lower incidence of CHD events (RR=0.63; 95% CI, 0.36-0.83), nonfatal MI (RR=0.48; 95% CI, 0.37-0.71), and all-cause mortality (RR=0.65; 95% CI, 0.49-0.83) but not with a statistically significant difference in stroke (RR=0.63; 95% CI, 0.47-1.09) or cardiac revascularization (RR=0.68; 95% CI, 0.52-1.19).

Total adverse events in this study were similar for red-yeast rice and placebo (2.1% vs 1.2%, respectively; P>.05). They included gastrointestinal discomfort, allergic reactions, myalgias, edema, erectile dysfunction, and neuropsychological symptoms.

Red-yeast rice is similar to placebo or another statin in statin-induced myalgia

In a small community-based trial of 62 adults with dyslipidemia and a history of statin-induced myalgia, investigators randomized patients to receive either red-yeast rice extract at 1800 mg (with 3.1 mg lovastatin) or placebo twice daily for 24 weeks.4 Patients’ weekly self-reports of pain (on a 10-point scale) were skewed at baseline (1.4 in the red-yeast rice group vs 2.6 in the placebo group; P=.026) but similar at 12 weeks (1.4 with red-yeast rice vs 1.9 with placebo; P=.30) and 24 weeks (1.2 with red-yeast rice vs 2.0 with placebo; P=.120).

An RCT of 43 adults with dyslipidemia and history of statin intolerance compared red-yeast rice extract (2400 mg, with 10 mg lovastatin) with pravastatin (20 mg) dosed twice a day.5 At the end of 12 weeks, mean self-reported pain scores (on a 10-point scale) were similar (1.4 with red-yeast rice vs 1.1 with pravastatin; P=.82), as were discontinuation rates because of myalgia (5% with red-yeast rice vs 9% with pravastatin; P=.99).

RECOMMENDATIONS

A narrative review of alternative therapies for heart failure and hypercholesterolemia states that red yeast rice may be a cost-saving option for hypercholesterolemia in patients who can’t afford other medications (purchased mostly online, cost $8-$20/month for a dosage equivalent to lovastatin 20 mg/d).6

A ConsumerLab review of red yeast rice products available since the FDA ban in 2011 tested products marketed in the United States and found variable amounts of lovastatin.1,7 The group determined that labeling was a poor guide to lovastatin content, which ranged from 0 to 20 mg per daily dose, and that the products may not have been standardized. The group concluded that therapeutic effects weren’t predictable.

1. National Institutes of Health. Red yeast rice: An introduction. National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health Web site. Available at: http://nccam.nih.gov/health/redyeastrice. Accessed October 28, 2013.

2. Shang Q, Liu Z, Chen K, et al. A systematic review of xuezhikang, an extract from red yeast rice, for coronary heart disease complicated by dyslipidemia. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2012;2012:636547.

3. Li JJ, Lu ZL, Kou WR, et al. Beneficial impact of xuezhikang on cardiovascular events and mortality in elderly hypertensive patients with previous myocardial infarction from the China Coronary Secondary Prevention Study (CCSPS). J Clin Pharmacol. 2009;49:947-956.

4. Becker DJ, Gordon RY, Halbert SC, et al. Red yeast rice for dyslipidemia in statin-intolerant patients: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2009;150:830-839,

W147-W149.

5. Halbert SC, French B, Gordon RY, et al. Tolerability of red yeast rice (2,400 mg twice daily) versus pravastatin (20 mg twice daily) in patients with previous statin intolerance. Am J Cardiol. 2010;105:198-204.

6. Morelli V, Zoorob RJ. Alternative therapies: Part II. Congestive heart failure and hypercholesterolemia. Am Fam Physician. 2000;62:1325-1330.

7. Consumerlab.com. Product Review: Red yeast rice supplements review. ConsumerLab Web site. Available at: https://www.consumerlab.com/reviews/Red-Yeast-Rice-Supplements-Review/Red_Yeast_Rice. Accessed January 20, 2015.

1. National Institutes of Health. Red yeast rice: An introduction. National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health Web site. Available at: http://nccam.nih.gov/health/redyeastrice. Accessed October 28, 2013.

2. Shang Q, Liu Z, Chen K, et al. A systematic review of xuezhikang, an extract from red yeast rice, for coronary heart disease complicated by dyslipidemia. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2012;2012:636547.

3. Li JJ, Lu ZL, Kou WR, et al. Beneficial impact of xuezhikang on cardiovascular events and mortality in elderly hypertensive patients with previous myocardial infarction from the China Coronary Secondary Prevention Study (CCSPS). J Clin Pharmacol. 2009;49:947-956.

4. Becker DJ, Gordon RY, Halbert SC, et al. Red yeast rice for dyslipidemia in statin-intolerant patients: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2009;150:830-839,

W147-W149.

5. Halbert SC, French B, Gordon RY, et al. Tolerability of red yeast rice (2,400 mg twice daily) versus pravastatin (20 mg twice daily) in patients with previous statin intolerance. Am J Cardiol. 2010;105:198-204.

6. Morelli V, Zoorob RJ. Alternative therapies: Part II. Congestive heart failure and hypercholesterolemia. Am Fam Physician. 2000;62:1325-1330.

7. Consumerlab.com. Product Review: Red yeast rice supplements review. ConsumerLab Web site. Available at: https://www.consumerlab.com/reviews/Red-Yeast-Rice-Supplements-Review/Red_Yeast_Rice. Accessed January 20, 2015.

Evidence-based answers from the Family Physicians Inquiries Network

Does any antidepressant besides bupropion help smokers quit?

EVIDENCE-BASED ANSWER:

Yes, nortriptyline approximately doubles smoking cessation rates, an effect comparable to bupropion. Adding nortriptyline to nicotine replacement therapy (NRT) doesn’t improve rates further (strength of recommendation [SOR]: A, systematic review of randomized controlled trials [RCTs]).

Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs; fluoxetine, paroxetine, sertraline, citalopram), venlafaxine, monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs; moclobemide, selegiline), doxepin, and St. John’s wort don’t improve smoking cessation rates (SOR: A, systematic reviews and RCTs).

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

Bupropion is the only Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved antidepressant recommended as a first-line pharmacologic agent to assist with smoking cessation, based in part on a meta-analysis of 44 placebo-controlled RCTs (13,728 patients), which found that bupropion had a relative risk (RR) of 1.62 for smoking cessation compared with placebo (95% confidence interval [CI], 1.49-1.76). Bupropion produced quit rates that were approximately double those of placebo rates (18% [range 4%-43%] for bupropion vs 9% [range 0%-18%] for placebo).1

Nortriptyline is also effective, other antidepressants not so much

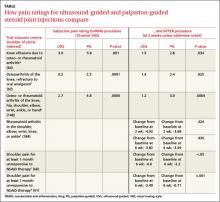

A Cochrane systematic review of 10 antidepressants used for smoking cessation included 64 placebo-controlled trials, measuring at least 6-month abstinence rates as primary outcomes, and monitoring biochemical markers (such as breath carbon monoxide and urinary cotinine) to verify abstinence. Some trials included participants with previous depressive episodes, but most didn’t enroll patients with active major depression.1 The TABLE1 gives an overview of the studies and outcomes.

Nortriptyline, which was evaluated in 6 trials, was the only antidepressant besides bupropion that was superior to placebo.1 Two of the nortriptyline trials included participants with active depression and the other trials had participants with a history of depression. One trial found no difference in quit rates for patients taking nortriptyline with or without a history of major depression, although the subgroups were small. Two trials measured quit rates for 12 months whereas the other 4 trials used 6-month quit rates.

Four additional RCTs with 1644 patients that combined nortriptyline with NRT found no improvement in quit rates compared with NRT alone (RR=1.21; 95% CI, 0.94-1.55).1 Three RCTs with 417 patients compared bupropion with nortriptyline and found no difference (RR=1.3; 95% CI, 0.93-1.8).1

SSRIs. None of the 4 SSRIs investigated in the trials (fluoxetine, paroxetine, sertraline, citalopram) improved smoking cessation rates more than placebo.1 The 5 RCTs that studied the drugs followed participants for as long as a year. None of the participants were depressed at the time of the studies, although some had a history of depression.

The sertraline RCT used individual counseling sessions in conjunction with either sertraline or placebo. All participants had a history of major depression.

The paroxetine trial used NRT in all patients randomized to either paroxetine or placebo.

Venlafaxine. The serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor venlafaxine didn’t improve smoking cessation rates over 12 months.1

MAOIs. Neither of the 2 MAOIs increased smoking cessation rates.1 The moclobemide RCT followed participants for 12 months; the 5 selegiline RCTs followed participants for as long as 6 months.

Other antidepressants. An RCT with 19 participants found that doxepin didn’t improve smoking cessation at 2 months.1 One RCT and one open, randomized trial of St. John’s wort found no benefit for smoking cessation.1,2

RECOMMENDATIONS

The United States Public Health Service (USPHS) and the University of Michigan Health System (UMHS) guidelines recommend the following FDA-approved pharmacotherapies as first-line agents for smoking cessation: sustained-release bupropion, NRT (gum, inhaler, lozenge, nasal spray, or patch), and varenicline.3,4 They say that clonidine and nortriptyline are also effective but recommend them as second-line agents because these drugs lack FDA approval for this purpose.

The USPHS also recommends combinations of NRT and bupropion for long-term use. Because of additional cost and limited benefit, UMHS recommends reserving NRT-bupropion combination therapy for highly addicted tobacco users who have several failed quit attempts.

The United States Preventive Services Task Force guideline emphasizes counseling and interventions to prevent tobacco use; it doesn’t provide recommendations for pharmacotherapy.5 It does cite the same agents recommended by USPHS and UMHS as effective.

1. Hughes JR, Stead LF, Hartmann-Boyce J, et al. Antidepressants for smoking cessation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;1:CD000031.

2. Sood A, Ebbert JO, Prasad K, et al. A randomized clinical trial of St. John’s wort for smoking cessation. J Altern Complement Med. 2010;16:761-767.

3. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Treating tobacco use and dependence: 2008 update. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality Web site. Available at: http://www.ahrq.gov/professionals/clinicians-providers/guidelines-recommendations/tobacco/clinicians/update/treating_tobacco_use08.pdf. Accessed October 9, 2014.

4. University of Michigan Health System. Tobacco treatment. University of Michigan Health System Web site. Available at: http://www.med.umich.edu/1info/fhp/practiceguides/smoking/smoking.pdf. Accessed October 9, 2014.

5. US Preventive Services Task Force. Counseling and interventions to prevent tobacco use and tobacco-caused disease in adults and pregnant women: US Preventive Services Task Force reaffirmation recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med. 2009;150:551-555.

EVIDENCE-BASED ANSWER:

Yes, nortriptyline approximately doubles smoking cessation rates, an effect comparable to bupropion. Adding nortriptyline to nicotine replacement therapy (NRT) doesn’t improve rates further (strength of recommendation [SOR]: A, systematic review of randomized controlled trials [RCTs]).

Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs; fluoxetine, paroxetine, sertraline, citalopram), venlafaxine, monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs; moclobemide, selegiline), doxepin, and St. John’s wort don’t improve smoking cessation rates (SOR: A, systematic reviews and RCTs).

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

Bupropion is the only Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved antidepressant recommended as a first-line pharmacologic agent to assist with smoking cessation, based in part on a meta-analysis of 44 placebo-controlled RCTs (13,728 patients), which found that bupropion had a relative risk (RR) of 1.62 for smoking cessation compared with placebo (95% confidence interval [CI], 1.49-1.76). Bupropion produced quit rates that were approximately double those of placebo rates (18% [range 4%-43%] for bupropion vs 9% [range 0%-18%] for placebo).1

Nortriptyline is also effective, other antidepressants not so much

A Cochrane systematic review of 10 antidepressants used for smoking cessation included 64 placebo-controlled trials, measuring at least 6-month abstinence rates as primary outcomes, and monitoring biochemical markers (such as breath carbon monoxide and urinary cotinine) to verify abstinence. Some trials included participants with previous depressive episodes, but most didn’t enroll patients with active major depression.1 The TABLE1 gives an overview of the studies and outcomes.

Nortriptyline, which was evaluated in 6 trials, was the only antidepressant besides bupropion that was superior to placebo.1 Two of the nortriptyline trials included participants with active depression and the other trials had participants with a history of depression. One trial found no difference in quit rates for patients taking nortriptyline with or without a history of major depression, although the subgroups were small. Two trials measured quit rates for 12 months whereas the other 4 trials used 6-month quit rates.

Four additional RCTs with 1644 patients that combined nortriptyline with NRT found no improvement in quit rates compared with NRT alone (RR=1.21; 95% CI, 0.94-1.55).1 Three RCTs with 417 patients compared bupropion with nortriptyline and found no difference (RR=1.3; 95% CI, 0.93-1.8).1

SSRIs. None of the 4 SSRIs investigated in the trials (fluoxetine, paroxetine, sertraline, citalopram) improved smoking cessation rates more than placebo.1 The 5 RCTs that studied the drugs followed participants for as long as a year. None of the participants were depressed at the time of the studies, although some had a history of depression.

The sertraline RCT used individual counseling sessions in conjunction with either sertraline or placebo. All participants had a history of major depression.

The paroxetine trial used NRT in all patients randomized to either paroxetine or placebo.

Venlafaxine. The serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor venlafaxine didn’t improve smoking cessation rates over 12 months.1

MAOIs. Neither of the 2 MAOIs increased smoking cessation rates.1 The moclobemide RCT followed participants for 12 months; the 5 selegiline RCTs followed participants for as long as 6 months.

Other antidepressants. An RCT with 19 participants found that doxepin didn’t improve smoking cessation at 2 months.1 One RCT and one open, randomized trial of St. John’s wort found no benefit for smoking cessation.1,2

RECOMMENDATIONS

The United States Public Health Service (USPHS) and the University of Michigan Health System (UMHS) guidelines recommend the following FDA-approved pharmacotherapies as first-line agents for smoking cessation: sustained-release bupropion, NRT (gum, inhaler, lozenge, nasal spray, or patch), and varenicline.3,4 They say that clonidine and nortriptyline are also effective but recommend them as second-line agents because these drugs lack FDA approval for this purpose.

The USPHS also recommends combinations of NRT and bupropion for long-term use. Because of additional cost and limited benefit, UMHS recommends reserving NRT-bupropion combination therapy for highly addicted tobacco users who have several failed quit attempts.

The United States Preventive Services Task Force guideline emphasizes counseling and interventions to prevent tobacco use; it doesn’t provide recommendations for pharmacotherapy.5 It does cite the same agents recommended by USPHS and UMHS as effective.

EVIDENCE-BASED ANSWER:

Yes, nortriptyline approximately doubles smoking cessation rates, an effect comparable to bupropion. Adding nortriptyline to nicotine replacement therapy (NRT) doesn’t improve rates further (strength of recommendation [SOR]: A, systematic review of randomized controlled trials [RCTs]).

Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs; fluoxetine, paroxetine, sertraline, citalopram), venlafaxine, monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs; moclobemide, selegiline), doxepin, and St. John’s wort don’t improve smoking cessation rates (SOR: A, systematic reviews and RCTs).

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

Bupropion is the only Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved antidepressant recommended as a first-line pharmacologic agent to assist with smoking cessation, based in part on a meta-analysis of 44 placebo-controlled RCTs (13,728 patients), which found that bupropion had a relative risk (RR) of 1.62 for smoking cessation compared with placebo (95% confidence interval [CI], 1.49-1.76). Bupropion produced quit rates that were approximately double those of placebo rates (18% [range 4%-43%] for bupropion vs 9% [range 0%-18%] for placebo).1

Nortriptyline is also effective, other antidepressants not so much

A Cochrane systematic review of 10 antidepressants used for smoking cessation included 64 placebo-controlled trials, measuring at least 6-month abstinence rates as primary outcomes, and monitoring biochemical markers (such as breath carbon monoxide and urinary cotinine) to verify abstinence. Some trials included participants with previous depressive episodes, but most didn’t enroll patients with active major depression.1 The TABLE1 gives an overview of the studies and outcomes.

Nortriptyline, which was evaluated in 6 trials, was the only antidepressant besides bupropion that was superior to placebo.1 Two of the nortriptyline trials included participants with active depression and the other trials had participants with a history of depression. One trial found no difference in quit rates for patients taking nortriptyline with or without a history of major depression, although the subgroups were small. Two trials measured quit rates for 12 months whereas the other 4 trials used 6-month quit rates.

Four additional RCTs with 1644 patients that combined nortriptyline with NRT found no improvement in quit rates compared with NRT alone (RR=1.21; 95% CI, 0.94-1.55).1 Three RCTs with 417 patients compared bupropion with nortriptyline and found no difference (RR=1.3; 95% CI, 0.93-1.8).1

SSRIs. None of the 4 SSRIs investigated in the trials (fluoxetine, paroxetine, sertraline, citalopram) improved smoking cessation rates more than placebo.1 The 5 RCTs that studied the drugs followed participants for as long as a year. None of the participants were depressed at the time of the studies, although some had a history of depression.

The sertraline RCT used individual counseling sessions in conjunction with either sertraline or placebo. All participants had a history of major depression.

The paroxetine trial used NRT in all patients randomized to either paroxetine or placebo.

Venlafaxine. The serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor venlafaxine didn’t improve smoking cessation rates over 12 months.1

MAOIs. Neither of the 2 MAOIs increased smoking cessation rates.1 The moclobemide RCT followed participants for 12 months; the 5 selegiline RCTs followed participants for as long as 6 months.

Other antidepressants. An RCT with 19 participants found that doxepin didn’t improve smoking cessation at 2 months.1 One RCT and one open, randomized trial of St. John’s wort found no benefit for smoking cessation.1,2

RECOMMENDATIONS

The United States Public Health Service (USPHS) and the University of Michigan Health System (UMHS) guidelines recommend the following FDA-approved pharmacotherapies as first-line agents for smoking cessation: sustained-release bupropion, NRT (gum, inhaler, lozenge, nasal spray, or patch), and varenicline.3,4 They say that clonidine and nortriptyline are also effective but recommend them as second-line agents because these drugs lack FDA approval for this purpose.

The USPHS also recommends combinations of NRT and bupropion for long-term use. Because of additional cost and limited benefit, UMHS recommends reserving NRT-bupropion combination therapy for highly addicted tobacco users who have several failed quit attempts.

The United States Preventive Services Task Force guideline emphasizes counseling and interventions to prevent tobacco use; it doesn’t provide recommendations for pharmacotherapy.5 It does cite the same agents recommended by USPHS and UMHS as effective.

1. Hughes JR, Stead LF, Hartmann-Boyce J, et al. Antidepressants for smoking cessation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;1:CD000031.

2. Sood A, Ebbert JO, Prasad K, et al. A randomized clinical trial of St. John’s wort for smoking cessation. J Altern Complement Med. 2010;16:761-767.

3. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Treating tobacco use and dependence: 2008 update. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality Web site. Available at: http://www.ahrq.gov/professionals/clinicians-providers/guidelines-recommendations/tobacco/clinicians/update/treating_tobacco_use08.pdf. Accessed October 9, 2014.

4. University of Michigan Health System. Tobacco treatment. University of Michigan Health System Web site. Available at: http://www.med.umich.edu/1info/fhp/practiceguides/smoking/smoking.pdf. Accessed October 9, 2014.

5. US Preventive Services Task Force. Counseling and interventions to prevent tobacco use and tobacco-caused disease in adults and pregnant women: US Preventive Services Task Force reaffirmation recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med. 2009;150:551-555.

1. Hughes JR, Stead LF, Hartmann-Boyce J, et al. Antidepressants for smoking cessation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;1:CD000031.

2. Sood A, Ebbert JO, Prasad K, et al. A randomized clinical trial of St. John’s wort for smoking cessation. J Altern Complement Med. 2010;16:761-767.

3. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Treating tobacco use and dependence: 2008 update. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality Web site. Available at: http://www.ahrq.gov/professionals/clinicians-providers/guidelines-recommendations/tobacco/clinicians/update/treating_tobacco_use08.pdf. Accessed October 9, 2014.

4. University of Michigan Health System. Tobacco treatment. University of Michigan Health System Web site. Available at: http://www.med.umich.edu/1info/fhp/practiceguides/smoking/smoking.pdf. Accessed October 9, 2014.

5. US Preventive Services Task Force. Counseling and interventions to prevent tobacco use and tobacco-caused disease in adults and pregnant women: US Preventive Services Task Force reaffirmation recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med. 2009;150:551-555.

Evidence-based answers from the Family Physicians Inquiries Network

Do oral contraceptives put women with a family history of breast cancer at increased risk?

No. Modern combined oral contraceptive pills (OCPs) don’t increase breast cancer risk in women with a family history (strength of recommendation [SOR]: B, systematic review of cohort, case-control studies). However, older, higher-dose OCPs (in use before 1975) did increase breast cancer risk in these women (SOR: C, case-control study).

Similarly, modern OCPs don’t raise breast cancer risk in women with BRCA1/2 mutations, although higher-dose, pre-1975 OCPs did (SOR: B and C, a meta-analysis of cohort and case-control studies).

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

A systematic review of the effect of combined OCPs on women with a family history of breast cancer found no additional increase in risk.1 Investigators identified 3 retrospective cohort studies (N=66,500, with 8500 cases) and 7 case-control studies (total 10,500 cases) from the past 40 years, most including women from the United States and Canada, but one including women from 5 continents.

In most trials, women of reproductive age using combined OCPs had 1 or more first-degree female relatives with breast cancer, although a few trials also included second-degree relatives. Women ranged in age from 20 to 79 years at diagnosis, and most trials controlled for age, parity, menstrual and menopausal history, duration of OCP exposure, and age at first use. Follow-up intervals for the retrospective cohort studies ranged from 5 to 16 years. Investigators were unable to combine results because of heterogenous populations.

Three of the cohort studies found no significant difference in breast cancer risk between OCP users and nonusers, regardless of age or duration of use. One cohort study found an increased risk in women taking older, higher-dose OCPs from before 1975 (relative risk [RR]=3.3; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.5-7.2). All of the case-control studies found no significant difference in breast cancer risk for any age of starting, duration of OCP use, or degree of relative with breast cancer.

A meta-analysis of 54 case-control studies (6757 cases), comprising approximately 90% of the epidemiologic information on this topic, also found no significant difference in breast cancer risk related to OCP use among women with one or more first-degree relatives with breast cancer.2 Investigators found that neither recent OCP use (<10 years, RR=0.77; 95% CI, 0.54-1.11) nor past OCP use (>10 years, RR=1.01; 95% CI, 0.80-1.28) affected risk of developing breast cancer.

Three additional case-control studies involving women with a family history of breast cancer also found no significant association for breast cancer incidence among OCP users compared with nonusers.3-5

Modern combined OCPs don’t raise risk in women with BRCA1/2 mutations

A meta-analysis of 5 studies (one retrospective cohort, 4 case-control, with a total of 2855 breast cancer cases and 2944 controls) evaluated whether combined OCPs increased the risk of breast cancer in women, all of whom were carrying BRCA1/2 mutations.6

Using modern combined OCPs didn’t raise the risk of breast cancer in BRCA1/2 carriers overall (RR=1.13; 95% CI, 0.88-1.45) or separately in BRCA1 carriers (5 studies, RR=1.09; 95% CI, 0.77-1.54) or BRCA2 carriers (3 studies, RR=1.15; 95% CI, 0.88-1.45).

However, pre-1975 (higher dose) combined OCPs produced significantly increased risk (RR=1.47; 95% CI, 1.06-2.04). Similarly, women who had used combined OCPs >10 years before the study (older women, likely to have been using pre-1975 OCPs) also had significantly increased risk (RR=1.46; 95% CI, 1.07-2.07).

A bit of good news: Combined OCPs reduce ovarian cancer risk

The analysis also determined that combined OCPs significantly reduced the risk of ovarian cancer in women carrying BRCA1/2 mutations (RR=0.50; 95% CI, 0.33-0.75), with an additional linear decrease in risk for each 10 years of OCP use (RR=0.64; 95% CI, 0.53-0.78).

RECOMMENDATIONS

The World Health Organization guidelines outlining criteria for contraceptive use state that OCPs don’t alter the risk of breast cancer among women with either a family history of breast cancer or breast cancer susceptibility genes.7

The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) says that a positive family history of breast cancer shouldn’t be regarded as a contraindication to OCP use.8 ACOG also says that women with the BRCA1 mutation have an increased risk of breast cancer if they used OCPs for longer than 5 years before age 30, but this risk may be more than balanced by the benefit of a greatly reduced risk of ovarian cancer.

1. Gaffield ME, Culwell KR, Ravi A. Oral contraceptives and family history of breast cancer. Contraception. 2009;80:372-380.

2. Collaborative Group on Hormonal Factors in Breast Cancer. Breast cancer and hormonal contraceptives: collaborative re-analysis of individual data on 53,297 women with breast cancer and 100,239 women without breast cancer from 54 epidemiological studies. Lancet. 1996;347:1713-1727.

3. Jernström H, Loman N, Johannsson OT, et al. Impact of teenage oral contraceptive use in a population-based series of early-onset breast cancer cases who have undergone BRCA mutation testing. Eur J Cancer. 2005;41:2312-2320.

4. Cibula D, Gompel A, Mueck AO, et al. Hormonal contraception and risk of cancer. Human Reprod Update. 2010;16: 631-650.

5. Long-term oral contraceptive use and the risk of breast cancer. The Centers for Disease Control Cancer and Steroid Hormone Study. JAMA. 1983;249:1591-1595.

6. Iodice S, Barile M, Rotmensz N, et al. Oral contraceptive use and breast or ovarian cancer risk in BRCA1/2 carriers: a meta-analysis. Eur J Cancer. 2010;46:2275-2284.

7. World Health Organization. Medical Eligibility Criteria for Contraceptive Use. 4th ed. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2009. World Health Organization Web site. Available at: http://whqlibdoc.who.int/publications/2010/9789241563888_eng.pdf. Accessed September 24, 2013.

8. ACOG Committee on Practice Bulletins-Gynecology. ACOG Practice Bulletin. No. 73: Use of hormonal contraception in women with coexisting medical conditions. Obstet Gynecol. 2006;107:1453-1472.

No. Modern combined oral contraceptive pills (OCPs) don’t increase breast cancer risk in women with a family history (strength of recommendation [SOR]: B, systematic review of cohort, case-control studies). However, older, higher-dose OCPs (in use before 1975) did increase breast cancer risk in these women (SOR: C, case-control study).

Similarly, modern OCPs don’t raise breast cancer risk in women with BRCA1/2 mutations, although higher-dose, pre-1975 OCPs did (SOR: B and C, a meta-analysis of cohort and case-control studies).

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

A systematic review of the effect of combined OCPs on women with a family history of breast cancer found no additional increase in risk.1 Investigators identified 3 retrospective cohort studies (N=66,500, with 8500 cases) and 7 case-control studies (total 10,500 cases) from the past 40 years, most including women from the United States and Canada, but one including women from 5 continents.

In most trials, women of reproductive age using combined OCPs had 1 or more first-degree female relatives with breast cancer, although a few trials also included second-degree relatives. Women ranged in age from 20 to 79 years at diagnosis, and most trials controlled for age, parity, menstrual and menopausal history, duration of OCP exposure, and age at first use. Follow-up intervals for the retrospective cohort studies ranged from 5 to 16 years. Investigators were unable to combine results because of heterogenous populations.

Three of the cohort studies found no significant difference in breast cancer risk between OCP users and nonusers, regardless of age or duration of use. One cohort study found an increased risk in women taking older, higher-dose OCPs from before 1975 (relative risk [RR]=3.3; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.5-7.2). All of the case-control studies found no significant difference in breast cancer risk for any age of starting, duration of OCP use, or degree of relative with breast cancer.

A meta-analysis of 54 case-control studies (6757 cases), comprising approximately 90% of the epidemiologic information on this topic, also found no significant difference in breast cancer risk related to OCP use among women with one or more first-degree relatives with breast cancer.2 Investigators found that neither recent OCP use (<10 years, RR=0.77; 95% CI, 0.54-1.11) nor past OCP use (>10 years, RR=1.01; 95% CI, 0.80-1.28) affected risk of developing breast cancer.

Three additional case-control studies involving women with a family history of breast cancer also found no significant association for breast cancer incidence among OCP users compared with nonusers.3-5

Modern combined OCPs don’t raise risk in women with BRCA1/2 mutations

A meta-analysis of 5 studies (one retrospective cohort, 4 case-control, with a total of 2855 breast cancer cases and 2944 controls) evaluated whether combined OCPs increased the risk of breast cancer in women, all of whom were carrying BRCA1/2 mutations.6

Using modern combined OCPs didn’t raise the risk of breast cancer in BRCA1/2 carriers overall (RR=1.13; 95% CI, 0.88-1.45) or separately in BRCA1 carriers (5 studies, RR=1.09; 95% CI, 0.77-1.54) or BRCA2 carriers (3 studies, RR=1.15; 95% CI, 0.88-1.45).

However, pre-1975 (higher dose) combined OCPs produced significantly increased risk (RR=1.47; 95% CI, 1.06-2.04). Similarly, women who had used combined OCPs >10 years before the study (older women, likely to have been using pre-1975 OCPs) also had significantly increased risk (RR=1.46; 95% CI, 1.07-2.07).

A bit of good news: Combined OCPs reduce ovarian cancer risk

The analysis also determined that combined OCPs significantly reduced the risk of ovarian cancer in women carrying BRCA1/2 mutations (RR=0.50; 95% CI, 0.33-0.75), with an additional linear decrease in risk for each 10 years of OCP use (RR=0.64; 95% CI, 0.53-0.78).

RECOMMENDATIONS

The World Health Organization guidelines outlining criteria for contraceptive use state that OCPs don’t alter the risk of breast cancer among women with either a family history of breast cancer or breast cancer susceptibility genes.7

The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) says that a positive family history of breast cancer shouldn’t be regarded as a contraindication to OCP use.8 ACOG also says that women with the BRCA1 mutation have an increased risk of breast cancer if they used OCPs for longer than 5 years before age 30, but this risk may be more than balanced by the benefit of a greatly reduced risk of ovarian cancer.

No. Modern combined oral contraceptive pills (OCPs) don’t increase breast cancer risk in women with a family history (strength of recommendation [SOR]: B, systematic review of cohort, case-control studies). However, older, higher-dose OCPs (in use before 1975) did increase breast cancer risk in these women (SOR: C, case-control study).

Similarly, modern OCPs don’t raise breast cancer risk in women with BRCA1/2 mutations, although higher-dose, pre-1975 OCPs did (SOR: B and C, a meta-analysis of cohort and case-control studies).

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

A systematic review of the effect of combined OCPs on women with a family history of breast cancer found no additional increase in risk.1 Investigators identified 3 retrospective cohort studies (N=66,500, with 8500 cases) and 7 case-control studies (total 10,500 cases) from the past 40 years, most including women from the United States and Canada, but one including women from 5 continents.

In most trials, women of reproductive age using combined OCPs had 1 or more first-degree female relatives with breast cancer, although a few trials also included second-degree relatives. Women ranged in age from 20 to 79 years at diagnosis, and most trials controlled for age, parity, menstrual and menopausal history, duration of OCP exposure, and age at first use. Follow-up intervals for the retrospective cohort studies ranged from 5 to 16 years. Investigators were unable to combine results because of heterogenous populations.

Three of the cohort studies found no significant difference in breast cancer risk between OCP users and nonusers, regardless of age or duration of use. One cohort study found an increased risk in women taking older, higher-dose OCPs from before 1975 (relative risk [RR]=3.3; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.5-7.2). All of the case-control studies found no significant difference in breast cancer risk for any age of starting, duration of OCP use, or degree of relative with breast cancer.

A meta-analysis of 54 case-control studies (6757 cases), comprising approximately 90% of the epidemiologic information on this topic, also found no significant difference in breast cancer risk related to OCP use among women with one or more first-degree relatives with breast cancer.2 Investigators found that neither recent OCP use (<10 years, RR=0.77; 95% CI, 0.54-1.11) nor past OCP use (>10 years, RR=1.01; 95% CI, 0.80-1.28) affected risk of developing breast cancer.

Three additional case-control studies involving women with a family history of breast cancer also found no significant association for breast cancer incidence among OCP users compared with nonusers.3-5

Modern combined OCPs don’t raise risk in women with BRCA1/2 mutations

A meta-analysis of 5 studies (one retrospective cohort, 4 case-control, with a total of 2855 breast cancer cases and 2944 controls) evaluated whether combined OCPs increased the risk of breast cancer in women, all of whom were carrying BRCA1/2 mutations.6

Using modern combined OCPs didn’t raise the risk of breast cancer in BRCA1/2 carriers overall (RR=1.13; 95% CI, 0.88-1.45) or separately in BRCA1 carriers (5 studies, RR=1.09; 95% CI, 0.77-1.54) or BRCA2 carriers (3 studies, RR=1.15; 95% CI, 0.88-1.45).

However, pre-1975 (higher dose) combined OCPs produced significantly increased risk (RR=1.47; 95% CI, 1.06-2.04). Similarly, women who had used combined OCPs >10 years before the study (older women, likely to have been using pre-1975 OCPs) also had significantly increased risk (RR=1.46; 95% CI, 1.07-2.07).

A bit of good news: Combined OCPs reduce ovarian cancer risk

The analysis also determined that combined OCPs significantly reduced the risk of ovarian cancer in women carrying BRCA1/2 mutations (RR=0.50; 95% CI, 0.33-0.75), with an additional linear decrease in risk for each 10 years of OCP use (RR=0.64; 95% CI, 0.53-0.78).

RECOMMENDATIONS

The World Health Organization guidelines outlining criteria for contraceptive use state that OCPs don’t alter the risk of breast cancer among women with either a family history of breast cancer or breast cancer susceptibility genes.7

The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) says that a positive family history of breast cancer shouldn’t be regarded as a contraindication to OCP use.8 ACOG also says that women with the BRCA1 mutation have an increased risk of breast cancer if they used OCPs for longer than 5 years before age 30, but this risk may be more than balanced by the benefit of a greatly reduced risk of ovarian cancer.

1. Gaffield ME, Culwell KR, Ravi A. Oral contraceptives and family history of breast cancer. Contraception. 2009;80:372-380.

2. Collaborative Group on Hormonal Factors in Breast Cancer. Breast cancer and hormonal contraceptives: collaborative re-analysis of individual data on 53,297 women with breast cancer and 100,239 women without breast cancer from 54 epidemiological studies. Lancet. 1996;347:1713-1727.

3. Jernström H, Loman N, Johannsson OT, et al. Impact of teenage oral contraceptive use in a population-based series of early-onset breast cancer cases who have undergone BRCA mutation testing. Eur J Cancer. 2005;41:2312-2320.

4. Cibula D, Gompel A, Mueck AO, et al. Hormonal contraception and risk of cancer. Human Reprod Update. 2010;16: 631-650.

5. Long-term oral contraceptive use and the risk of breast cancer. The Centers for Disease Control Cancer and Steroid Hormone Study. JAMA. 1983;249:1591-1595.

6. Iodice S, Barile M, Rotmensz N, et al. Oral contraceptive use and breast or ovarian cancer risk in BRCA1/2 carriers: a meta-analysis. Eur J Cancer. 2010;46:2275-2284.

7. World Health Organization. Medical Eligibility Criteria for Contraceptive Use. 4th ed. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2009. World Health Organization Web site. Available at: http://whqlibdoc.who.int/publications/2010/9789241563888_eng.pdf. Accessed September 24, 2013.

8. ACOG Committee on Practice Bulletins-Gynecology. ACOG Practice Bulletin. No. 73: Use of hormonal contraception in women with coexisting medical conditions. Obstet Gynecol. 2006;107:1453-1472.

1. Gaffield ME, Culwell KR, Ravi A. Oral contraceptives and family history of breast cancer. Contraception. 2009;80:372-380.

2. Collaborative Group on Hormonal Factors in Breast Cancer. Breast cancer and hormonal contraceptives: collaborative re-analysis of individual data on 53,297 women with breast cancer and 100,239 women without breast cancer from 54 epidemiological studies. Lancet. 1996;347:1713-1727.

3. Jernström H, Loman N, Johannsson OT, et al. Impact of teenage oral contraceptive use in a population-based series of early-onset breast cancer cases who have undergone BRCA mutation testing. Eur J Cancer. 2005;41:2312-2320.

4. Cibula D, Gompel A, Mueck AO, et al. Hormonal contraception and risk of cancer. Human Reprod Update. 2010;16: 631-650.

5. Long-term oral contraceptive use and the risk of breast cancer. The Centers for Disease Control Cancer and Steroid Hormone Study. JAMA. 1983;249:1591-1595.

6. Iodice S, Barile M, Rotmensz N, et al. Oral contraceptive use and breast or ovarian cancer risk in BRCA1/2 carriers: a meta-analysis. Eur J Cancer. 2010;46:2275-2284.

7. World Health Organization. Medical Eligibility Criteria for Contraceptive Use. 4th ed. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2009. World Health Organization Web site. Available at: http://whqlibdoc.who.int/publications/2010/9789241563888_eng.pdf. Accessed September 24, 2013.

8. ACOG Committee on Practice Bulletins-Gynecology. ACOG Practice Bulletin. No. 73: Use of hormonal contraception in women with coexisting medical conditions. Obstet Gynecol. 2006;107:1453-1472.

Evidence-based answers from the Family Physicians Inquiries Network

Are topical nitrates safe and effective for upper extremity tendinopathies?

Topical nitrates provide short-term relief with some side effects, especially headache. Topical nitroglycerin (NTG) patches improve subjective pain scores by about 30% and range of motion over 3 days in patients with acute shoulder tendinopathy (strength of recommendation [SOR]: C, small randomized controlled trial [RCT] with no methodologic flaws).

NTG patches, when combined with tendon rehabilitation, improve subjective pain ratings by about 30% and shoulder strength by about 10% in patients with chronic shoulder tendinopathy over 3 to 6 months, but not in the long term (SOR: C, RCTs with methodologic flaws). They improve pain and strength 15% to 50% for chronic extensor tendinosis of the elbow over a 6-month period (SOR: C, small RCT with methodologic flaws).

NTG patches used without tendon rehabilitation don’t improve pain or strength in chronic lateral epicondylitis over 8 weeks (SOR: C, RCT).

Topical NTG patches commonly produce headaches and rashes (SOR: B, multiple RCTs).

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

A small RCT found that NTG therapy improved short-term pain and joint mobility in patients with acute supraspinatus tendinitis.1 Investigators randomized 10 men and 10 women with acute shoulder tendonitis (fewer than 7 days’ duration) to use either 5-mg NTG patches or placebo patches daily for 3 days. Patients rated pain on a 10-point scale, and investigators measured joint mobility on a 4-point scale.

After 48 hours of treatment, NTG patches significantly reduced pain ratings from baseline (from 7 to 2 points; P<.001), whereas placebo didn’t (6 vs 6 points; P not significant). NTG patches also improved joint mobility from baseline (from 2 points “moderately restricted” to .1 points “not restricted”; P<.001), but placebo didn’t (1.2 points “mildly restricted” vs 1.2 points; P not significant). The placebo group had less pain and joint restriction than the NTG group at the start of the study. Two patients reported headache 24 hours after starting treatment.

NTG plus rehabilitation improves chronic shoulder pain, range of motion

A double-blind RCT evaluating NTG patches for 53 patients (57 shoulders) with chronic supraspinatus tendinopathy (shoulder pain lasting longer than 3 months) found that they improved pain, strength, and range of motion at 3 to 6 months.2 Investigators randomized patients to receive one-quarter of a 5-mg 24-hour NTG patch or placebo patch daily and enrolled all patients in a rehabilitation program. They assessed subjective pain (at night and with activity), strength, and external rotation at baseline and at 2, 6, 12, and 24 weeks.

NTG patches improved nighttime pain about 30% (at 12 and 24 weeks), pain with activity about 60% (at 24 weeks), strength about 10% (at 12 and 24 weeks), and range of motion about 20% (at 24 weeks; P<.05 for all comparisons). The placebo group initially had more pain, less strength, and less mobility than the NTG group. Investigators reported no adverse effects.

NTG and rehab improve elbow pain, but with side effects

Another RCT comparing topical NTG patches in patients with chronic extensor tendinosis of the elbow found that they improved most parameters.3 Investigators randomized 86 patients with elbow tendonitis (longer than 3 months) to NTG patches (one-quarter of a 5-mg 24-hour patch) or placebo patches and enrolled all patients in a tendon rehabilitation program. They assessed subjective pain, extensor tendon tenderness, and muscle strength at baseline and at 2, 6, 12, and 24 weeks.

NTG patches improved subjective pain, tendon tenderness, and strength significantly more than placebo at all follow-up points, by 15% to 50% (P<.05 for all comparisons). The study was flawed because the control group started with more pain, tenderness, and weakness than the NTG group. Five patients discontinued NTG because of adverse effects (headache, dermatitis, and facial flushing).

A follow-up study done 5 years after discontinuation of therapy found equal outcomes with NTG and placebo.4 Investigators evaluated, by phone or in person, 58 of the 86 patients in the original study. NTG and placebo therapy produced equivalent reductions in subjective 0 to 4 elbow pain scores over baseline (average pain 2.5 initially, 1.5 at 12 weeks, and 1.0 at 5 years; P<.01 for all comparisons with baseline, no significant difference between nitrates and placebo).

NTG without rehab works no better than placebo

Another RCT that evaluated 3 different doses of NTG patches for 8 weeks in 154 patients with chronic lateral epicondylosis found NTG treatment was no better than placebo for pain or strength.5 Investigators randomized patients with more than 3 months of symptoms to 3 NTG patch doses (.72 mg/24 h, 1.44 mg/ 24 h, or 3.6 mg/24 h) compared with placebo and evaluated subjective pain (at rest, with activity, and at night), grip strength, and force, at baseline and 8 weeks.

The study lacked a formal wrist strengthening rehabilitation program. Patients in the placebo group had lower baseline pain scores than the NTG groups. Seven patients dropped out of the study because of headaches.

RECOMMENDATIONS

We found no authoritative recommendations regarding the use of topical nitrates for upper extremity tendinopathies.

An online reference text doesn’t make a recommendation, but references the studies described previously.6 The authors state that headache is the most common adverse effect of topical nitrates, but it becomes less severe over the course of treatment. They recommend caution in patients with hypotension, pregnancy, or migraines, and those who take diuretics. The authors also note that nitrates are relatively contraindicated in patients with ischemic heart disease, anemia, phosphodiesterase inhibitor therapy (such as sildenafil), angle-closure glaucoma, and allergy to nitrates.

1. Berrazueta JR, Losada A, Poveda J, et al. Successful treatment of shoulder pain syndrome due to supraspinatus tendinitis with transdermal nitroglycerin. A double blind study. Pain. 1996;66:63-67.