User login

Hysterotomy incision and repair: Many options, many personal preferences

CASE: Your colleague’s hysterotomy practices vary from yours

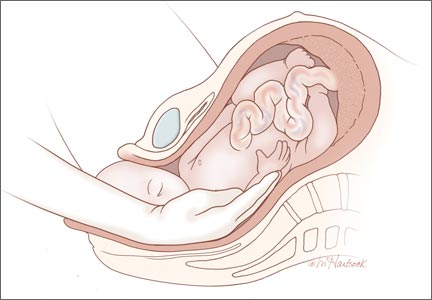

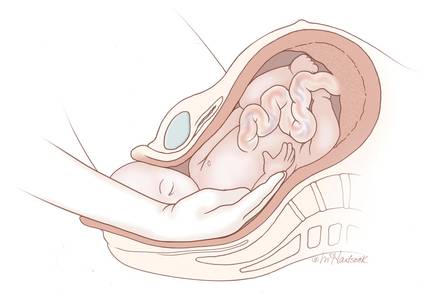

You are in the hospital on a weekend inducing labor in your patient with hypertension. A colleague asks you to assist at a primary cesarean delivery for failure to progress in the second stage. You are glad to help. During the cesarean delivery, your colleague does not create a bladder flap, makes a superficial incision in the uterus and enters the uterine cavity bluntly with her index finger, uses blunt cephalad-caudad expansion of the uterine incision, and closes the uterine incision in a single-layer of continuous suture.

In your practice your general preference is to routinely dissect a bladder flap, enter the uterus using Allis clamps and sharp dissection; use blunt transverse expansion of the uterine incision; and close the uterine incision in two layers, locking the first layer. You wonder, is there any evidence that there is one best approach to managing the hysterotomy incision?

For many obstetrician-gynecologists, cesarean delivery is the major operation we perform most frequently. In planning and performing a cesarean delivery there are many technical surgical decision points, each with many options. A recent Cochrane review concluded that for most surgical options for uterine incision and closure, short-term maternal outcomes were similar among the options and that surgeons should use the techniques that they prefer and are comfortable performing.1 However, other authorities believe that the available evidence indicates that certain surgical techniques are associated with better maternal outcomes.2,3

In this editorial I focus on the varying surgical options available when performing a low transverse hysterotomy during cesarean delivery and the impact of these choices on maternal outcomes.

The bladder flap—surgeon’s choice

Theoretically, dissecting a bladder flap moves the dome of the bladder away from the anterior surface of the lower uterine segment, thereby protecting it from injury during the hysterotomy incision and repair. Three randomized trials have evaluated maternal outcomes following a hysterotomy with or without a bladder flap. All three trials reported that maternal outcomes were similar whether or not a bladder flap was created.4–6 In one trial, the creation of a bladder flap during a primary cesarean delivery was associated with increased adhesions between the parietal and visceral peritoneum and between the bladder and uterus at a repeat cesarean delivery.5

Some authorities have concluded that in most cesarean deliveries it is not necessary to create a bladder flap because the evidence does not indicate that it improves surgical outcomes.3 However, there may be clinical situations where a bladder flap is warranted. For example, during a repeat cesarean delivery, if the bladder is observed to be advanced high on the anterior uterine wall because of previous uterine surgery, a bladder flap may be helpful to ensure that the hysterotomy incision is performed in the lower uterine segment and not in the thickest, most muscular part of the uterine wall.

A second example is a case of arrested labor in the second stage with a deep transverse arrest of a macrosomic fetus. Lower segment lacerations may occur in this scenario, and some clinicians elect to dissect a bladder flap in anticipation of the risk of multiple extensions and a difficult hysterotomy repair. Since bladder injury occurs in less than 1% of cesarean deliveries, it would be difficult to perform a study with sufficient statistical power to determine whether creating a bladder flap influences the rate of bladder injury.7

Entering the uterine cavity—Try blunt entry

There are few clinical trial data to guide the technique for entering the uterine cavity. A major goal is to minimize the risk of a fetal laceration. One technique to reduce this risk is to superficially incise the uterus with a scalpel and then enter the uterus bluntly with a finger. Both the Misgav Ladach and modified Joel-Cohen techniques for cesarean delivery advocate the use of a superficial incision of the lower uterine segment with blunt entry into the uterine cavity.8,9 Other surgical options for entering the uterine cavity with minimal risk to the fetus include:

- Superficially incise the uterus with a scalpel and then apply Allis clamps to the upper and lower incision. Pull the tissue away from the underlying fetus before incising the final layer of uterine tissue and entering the cavity.10

- Apply the tip of the suction tubing with suction on and gently elevate the tissue trapped in the suction tip, incising the tissue to enter the uterus.

- Use a surgical device designed to reduce fetal lacerations (such as C-SAFE, CooperSurgical) to enter the uterus and extend the hysterotomy incision.11

Expanding the uterine incision—Use blunt expansion

Authors of a recent Cochrane meta-analysis analyzed five randomized controlled trials, involving

2,141 women, that evaluated blunt versus sharp expansion of a low transverse uterine incision.1 There was no difference in maternal febrile morbidity or major morbidity between the two techniques. However, blunt expansion of the uterine incision was associated with slightly less maternal blood loss and a lower risk of maternal blood transfusion than sharp incision (0.7% vs 3.1%).1 In another meta-analysis blunt expansion of the uterine incision with the surgeon’s fingers resulted in a smaller decrease in hematocrit and hemoglobin levels and fewer unintended extensions, but no difference in the rate of blood transfusion.12 Based on these findings some authorities recommend using blunt expansion of the uterine incision when a lower uterine segment incision is performed.3

One study, involving 811 women, compared cephalad-caudad blunt expansion versus transverse blunt expansion of the uterine incision.13 Cephalad-caudad blunt expansion compared with transverse blunt expansion resulted in a trend to less blood loss (398 mL versus 440 mL; P = .09), a significantly lower rate of unintended extension of the uterine incision (3.7% vs 7.4%, P = .03) and fewer cases with blood loss greater than 1,500 mL (0.2% vs 2.0%, P = .04). However, there was no difference in the rate of transfusion (0.7% vs 0.7%, P = 1.0) between cephalad-caudad versus transverse blunt expansion. Based on the results from this one trial, some authorities recommend that cephalad-caudad blunt extension be utilized rather than transverse blunt extension.3

Closing the uterine incision—One or two layers?

In the recent Cochrane meta-analysis, researchers compared outcomes of single-layer and two-layer closure of the uterine incision in 14 studies involving 13,890 women.1 There was no difference in rates of febrile morbidity (5.0% vs 5.1%), wound infection (9.4% vs 9.5%), or blood transfusion (2.1% vs 2.4%) between the two techniques. Authors of another systematic review of 20 trials of single- versus double-layer closure of the uterine incision concluded that, based on the available evidence from randomized trials, single- and double-layer closure appeared to produce similar outcomes.14 These authors cautioned, however, that based on nonrandomized studies, single layer closure might be associated with an increased risk of uterine rupture in a subsequent pregnancy.15,16

A uterine incision that was closed with a locked single-layer closure may be at an especially high risk of rupture during a subsequent trial of labor. In one analysis of relevant reports with heterogeneous study designs, the risk of uterine rupture during a trial of labor after a prior cesarean was 1.8% with a double-layer closure, 3.5% with an unlocked single-layer closure, and 6.2% with a locked single-layer closure.17 My perspective is that a double-layer closure generally is preferred because in a future pregnancy with a planned vaginal delivery, the double-layer closure may be associated with a lower rate of uterine rupture.

Some authorities recommend single-layer uterine closure if the patient is sure that she has no future plans to conceive. For example, a woman who is undergoing a tubal ligation at the time of cesarean delivery may be an optimal candidate for single-layer closure.3

Individualization and innovation in surgical care

Surgeons advance their skills by continually using the best evidence and advice from colleagues to guide changes in their practice. Many clinical situations present unique combinations of medical and anatomic problems, and surgeons need to use both creativity and expert judgment to solve these unique problems. Surgical choices that are guided by both the best evidence and hard-won clinical experience will result in optimal patient outcomes.

Share your thoughts on this article! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

1. Dodd JM, Anderson ER, Gates S, Grivell RM. Surgical techniques for uterine incision and uterine closure at the time of cesarean section. Cochrane Database Sys Rev. 2014;7(3):CD004732.

2. Berghella V, Baxter JK, Chauhan SP. Evidence-based surgery for cesarean delivery. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2005;193(5):1607–1617.

3. Dahlke JD, Mendez-Figueroa H, Rouse DJ, Berghella V, Baxter JK, Chauhan SP. Evidence-based surgery for cesarean delivery: an updated systematic review. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2013;209(4):294–306.

4. Hohlagschwandtner M, Ruecklinger E, Husslein P, Joura EA. Is the formation of a bladder flap at cesarean necessary? A randomized trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2001;98(6):1089–1092.

5. Malvasi A, Tinelli A, Guido M, et al. Effect of avoiding bladder flap formation in caesarean section on repeat caesarean delivery Eur J Obstet Gynecol. 2011;159(2):300–304.

6. Tuuli MG, Obido AO, Fogertey P, Roehl K, Stamilio D, Macones GA. Utility of the bladder flap at cesarean delivery. A randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2012;119(4):815–821.

7. Cahill AG, Stout MJ, Stamillo DM, Odibo AO, Peipert JF, Macones GA. Risk factors for bladder injury in patients with a prior hysterotomy. Obstet Gynecol. 2008;112(1):116–120.

8. Holmgren G, Sjoholm L, Stark M. The Misgav-Ladach method for cesarean section: method description. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 1999;78(7):615–621.

9. Wallin G, Fall O. Modified Joel-Cohen technique for cesarean delivery. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1999;106(3):221–226.

10. Gilstrap LC, Cunningham FG, Van Dorsten JP, eds. Operative Obstetrics, 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw Hill; 2002.

11. C SAFE. http://www.csafe.us/. Trumbull, CT: CooperSurgical, Inc.

12. Saad AF, Rahman M, Costantine MM, Saade GR. Blunt versus sharp uterine incision expansion during low transverse cesarean delivery: a metaanalysis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2014;211(6):684.e1–e11.

13. Cromi A, Ghezzi F, Di Naro E, Siesto G, Loverro G, Bolis P. Blunt expansion of the low transverse uterine incision at cesarean delivery: a randomized comparison of 2 techniques. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2008;199(3):292.e1–e6.

14. Roberge S, Demers S, Berghella V, Chaillet N, Moore L, Bujold E. Impact of single- and double-layer closure on adverse outcomes and uterine scar defect: a systematic review and metaanalysis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2014; 211(5):453–460.

15. Yasmin S, Sadaf J, Fatima N. Impact of methods for uterine incision closure on repeat cesarean section scar of lower uterine segment. J Coll Physicians Surg Pak. 2011;21(9): 522–526.

16. Bujold E, Mehta SH, Bujold C, Gauthier RJ. Interdelivery interval and uterine rupture. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2002;187(5): 1199–1202.

17. Roberge S, Chaillet N, Boutin A, et al. Single- versus double-layer closure of the hysterotomy incision during cesarean delivery and risk of uterine rupture. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2011;115(1): 5–10.

CASE: Your colleague’s hysterotomy practices vary from yours

You are in the hospital on a weekend inducing labor in your patient with hypertension. A colleague asks you to assist at a primary cesarean delivery for failure to progress in the second stage. You are glad to help. During the cesarean delivery, your colleague does not create a bladder flap, makes a superficial incision in the uterus and enters the uterine cavity bluntly with her index finger, uses blunt cephalad-caudad expansion of the uterine incision, and closes the uterine incision in a single-layer of continuous suture.

In your practice your general preference is to routinely dissect a bladder flap, enter the uterus using Allis clamps and sharp dissection; use blunt transverse expansion of the uterine incision; and close the uterine incision in two layers, locking the first layer. You wonder, is there any evidence that there is one best approach to managing the hysterotomy incision?

For many obstetrician-gynecologists, cesarean delivery is the major operation we perform most frequently. In planning and performing a cesarean delivery there are many technical surgical decision points, each with many options. A recent Cochrane review concluded that for most surgical options for uterine incision and closure, short-term maternal outcomes were similar among the options and that surgeons should use the techniques that they prefer and are comfortable performing.1 However, other authorities believe that the available evidence indicates that certain surgical techniques are associated with better maternal outcomes.2,3

In this editorial I focus on the varying surgical options available when performing a low transverse hysterotomy during cesarean delivery and the impact of these choices on maternal outcomes.

The bladder flap—surgeon’s choice

Theoretically, dissecting a bladder flap moves the dome of the bladder away from the anterior surface of the lower uterine segment, thereby protecting it from injury during the hysterotomy incision and repair. Three randomized trials have evaluated maternal outcomes following a hysterotomy with or without a bladder flap. All three trials reported that maternal outcomes were similar whether or not a bladder flap was created.4–6 In one trial, the creation of a bladder flap during a primary cesarean delivery was associated with increased adhesions between the parietal and visceral peritoneum and between the bladder and uterus at a repeat cesarean delivery.5

Some authorities have concluded that in most cesarean deliveries it is not necessary to create a bladder flap because the evidence does not indicate that it improves surgical outcomes.3 However, there may be clinical situations where a bladder flap is warranted. For example, during a repeat cesarean delivery, if the bladder is observed to be advanced high on the anterior uterine wall because of previous uterine surgery, a bladder flap may be helpful to ensure that the hysterotomy incision is performed in the lower uterine segment and not in the thickest, most muscular part of the uterine wall.

A second example is a case of arrested labor in the second stage with a deep transverse arrest of a macrosomic fetus. Lower segment lacerations may occur in this scenario, and some clinicians elect to dissect a bladder flap in anticipation of the risk of multiple extensions and a difficult hysterotomy repair. Since bladder injury occurs in less than 1% of cesarean deliveries, it would be difficult to perform a study with sufficient statistical power to determine whether creating a bladder flap influences the rate of bladder injury.7

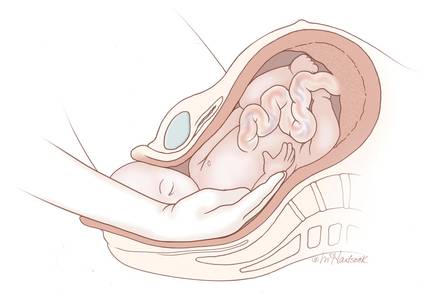

Entering the uterine cavity—Try blunt entry

There are few clinical trial data to guide the technique for entering the uterine cavity. A major goal is to minimize the risk of a fetal laceration. One technique to reduce this risk is to superficially incise the uterus with a scalpel and then enter the uterus bluntly with a finger. Both the Misgav Ladach and modified Joel-Cohen techniques for cesarean delivery advocate the use of a superficial incision of the lower uterine segment with blunt entry into the uterine cavity.8,9 Other surgical options for entering the uterine cavity with minimal risk to the fetus include:

- Superficially incise the uterus with a scalpel and then apply Allis clamps to the upper and lower incision. Pull the tissue away from the underlying fetus before incising the final layer of uterine tissue and entering the cavity.10

- Apply the tip of the suction tubing with suction on and gently elevate the tissue trapped in the suction tip, incising the tissue to enter the uterus.

- Use a surgical device designed to reduce fetal lacerations (such as C-SAFE, CooperSurgical) to enter the uterus and extend the hysterotomy incision.11

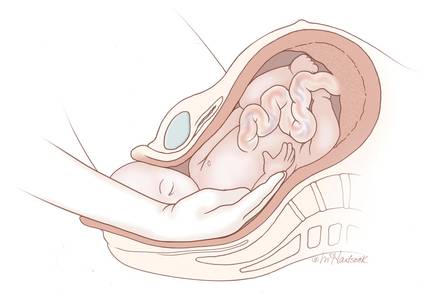

Expanding the uterine incision—Use blunt expansion

Authors of a recent Cochrane meta-analysis analyzed five randomized controlled trials, involving

2,141 women, that evaluated blunt versus sharp expansion of a low transverse uterine incision.1 There was no difference in maternal febrile morbidity or major morbidity between the two techniques. However, blunt expansion of the uterine incision was associated with slightly less maternal blood loss and a lower risk of maternal blood transfusion than sharp incision (0.7% vs 3.1%).1 In another meta-analysis blunt expansion of the uterine incision with the surgeon’s fingers resulted in a smaller decrease in hematocrit and hemoglobin levels and fewer unintended extensions, but no difference in the rate of blood transfusion.12 Based on these findings some authorities recommend using blunt expansion of the uterine incision when a lower uterine segment incision is performed.3

One study, involving 811 women, compared cephalad-caudad blunt expansion versus transverse blunt expansion of the uterine incision.13 Cephalad-caudad blunt expansion compared with transverse blunt expansion resulted in a trend to less blood loss (398 mL versus 440 mL; P = .09), a significantly lower rate of unintended extension of the uterine incision (3.7% vs 7.4%, P = .03) and fewer cases with blood loss greater than 1,500 mL (0.2% vs 2.0%, P = .04). However, there was no difference in the rate of transfusion (0.7% vs 0.7%, P = 1.0) between cephalad-caudad versus transverse blunt expansion. Based on the results from this one trial, some authorities recommend that cephalad-caudad blunt extension be utilized rather than transverse blunt extension.3

Closing the uterine incision—One or two layers?

In the recent Cochrane meta-analysis, researchers compared outcomes of single-layer and two-layer closure of the uterine incision in 14 studies involving 13,890 women.1 There was no difference in rates of febrile morbidity (5.0% vs 5.1%), wound infection (9.4% vs 9.5%), or blood transfusion (2.1% vs 2.4%) between the two techniques. Authors of another systematic review of 20 trials of single- versus double-layer closure of the uterine incision concluded that, based on the available evidence from randomized trials, single- and double-layer closure appeared to produce similar outcomes.14 These authors cautioned, however, that based on nonrandomized studies, single layer closure might be associated with an increased risk of uterine rupture in a subsequent pregnancy.15,16

A uterine incision that was closed with a locked single-layer closure may be at an especially high risk of rupture during a subsequent trial of labor. In one analysis of relevant reports with heterogeneous study designs, the risk of uterine rupture during a trial of labor after a prior cesarean was 1.8% with a double-layer closure, 3.5% with an unlocked single-layer closure, and 6.2% with a locked single-layer closure.17 My perspective is that a double-layer closure generally is preferred because in a future pregnancy with a planned vaginal delivery, the double-layer closure may be associated with a lower rate of uterine rupture.

Some authorities recommend single-layer uterine closure if the patient is sure that she has no future plans to conceive. For example, a woman who is undergoing a tubal ligation at the time of cesarean delivery may be an optimal candidate for single-layer closure.3

Individualization and innovation in surgical care

Surgeons advance their skills by continually using the best evidence and advice from colleagues to guide changes in their practice. Many clinical situations present unique combinations of medical and anatomic problems, and surgeons need to use both creativity and expert judgment to solve these unique problems. Surgical choices that are guided by both the best evidence and hard-won clinical experience will result in optimal patient outcomes.

Share your thoughts on this article! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

CASE: Your colleague’s hysterotomy practices vary from yours

You are in the hospital on a weekend inducing labor in your patient with hypertension. A colleague asks you to assist at a primary cesarean delivery for failure to progress in the second stage. You are glad to help. During the cesarean delivery, your colleague does not create a bladder flap, makes a superficial incision in the uterus and enters the uterine cavity bluntly with her index finger, uses blunt cephalad-caudad expansion of the uterine incision, and closes the uterine incision in a single-layer of continuous suture.

In your practice your general preference is to routinely dissect a bladder flap, enter the uterus using Allis clamps and sharp dissection; use blunt transverse expansion of the uterine incision; and close the uterine incision in two layers, locking the first layer. You wonder, is there any evidence that there is one best approach to managing the hysterotomy incision?

For many obstetrician-gynecologists, cesarean delivery is the major operation we perform most frequently. In planning and performing a cesarean delivery there are many technical surgical decision points, each with many options. A recent Cochrane review concluded that for most surgical options for uterine incision and closure, short-term maternal outcomes were similar among the options and that surgeons should use the techniques that they prefer and are comfortable performing.1 However, other authorities believe that the available evidence indicates that certain surgical techniques are associated with better maternal outcomes.2,3

In this editorial I focus on the varying surgical options available when performing a low transverse hysterotomy during cesarean delivery and the impact of these choices on maternal outcomes.

The bladder flap—surgeon’s choice

Theoretically, dissecting a bladder flap moves the dome of the bladder away from the anterior surface of the lower uterine segment, thereby protecting it from injury during the hysterotomy incision and repair. Three randomized trials have evaluated maternal outcomes following a hysterotomy with or without a bladder flap. All three trials reported that maternal outcomes were similar whether or not a bladder flap was created.4–6 In one trial, the creation of a bladder flap during a primary cesarean delivery was associated with increased adhesions between the parietal and visceral peritoneum and between the bladder and uterus at a repeat cesarean delivery.5

Some authorities have concluded that in most cesarean deliveries it is not necessary to create a bladder flap because the evidence does not indicate that it improves surgical outcomes.3 However, there may be clinical situations where a bladder flap is warranted. For example, during a repeat cesarean delivery, if the bladder is observed to be advanced high on the anterior uterine wall because of previous uterine surgery, a bladder flap may be helpful to ensure that the hysterotomy incision is performed in the lower uterine segment and not in the thickest, most muscular part of the uterine wall.

A second example is a case of arrested labor in the second stage with a deep transverse arrest of a macrosomic fetus. Lower segment lacerations may occur in this scenario, and some clinicians elect to dissect a bladder flap in anticipation of the risk of multiple extensions and a difficult hysterotomy repair. Since bladder injury occurs in less than 1% of cesarean deliveries, it would be difficult to perform a study with sufficient statistical power to determine whether creating a bladder flap influences the rate of bladder injury.7

Entering the uterine cavity—Try blunt entry

There are few clinical trial data to guide the technique for entering the uterine cavity. A major goal is to minimize the risk of a fetal laceration. One technique to reduce this risk is to superficially incise the uterus with a scalpel and then enter the uterus bluntly with a finger. Both the Misgav Ladach and modified Joel-Cohen techniques for cesarean delivery advocate the use of a superficial incision of the lower uterine segment with blunt entry into the uterine cavity.8,9 Other surgical options for entering the uterine cavity with minimal risk to the fetus include:

- Superficially incise the uterus with a scalpel and then apply Allis clamps to the upper and lower incision. Pull the tissue away from the underlying fetus before incising the final layer of uterine tissue and entering the cavity.10

- Apply the tip of the suction tubing with suction on and gently elevate the tissue trapped in the suction tip, incising the tissue to enter the uterus.

- Use a surgical device designed to reduce fetal lacerations (such as C-SAFE, CooperSurgical) to enter the uterus and extend the hysterotomy incision.11

Expanding the uterine incision—Use blunt expansion

Authors of a recent Cochrane meta-analysis analyzed five randomized controlled trials, involving

2,141 women, that evaluated blunt versus sharp expansion of a low transverse uterine incision.1 There was no difference in maternal febrile morbidity or major morbidity between the two techniques. However, blunt expansion of the uterine incision was associated with slightly less maternal blood loss and a lower risk of maternal blood transfusion than sharp incision (0.7% vs 3.1%).1 In another meta-analysis blunt expansion of the uterine incision with the surgeon’s fingers resulted in a smaller decrease in hematocrit and hemoglobin levels and fewer unintended extensions, but no difference in the rate of blood transfusion.12 Based on these findings some authorities recommend using blunt expansion of the uterine incision when a lower uterine segment incision is performed.3

One study, involving 811 women, compared cephalad-caudad blunt expansion versus transverse blunt expansion of the uterine incision.13 Cephalad-caudad blunt expansion compared with transverse blunt expansion resulted in a trend to less blood loss (398 mL versus 440 mL; P = .09), a significantly lower rate of unintended extension of the uterine incision (3.7% vs 7.4%, P = .03) and fewer cases with blood loss greater than 1,500 mL (0.2% vs 2.0%, P = .04). However, there was no difference in the rate of transfusion (0.7% vs 0.7%, P = 1.0) between cephalad-caudad versus transverse blunt expansion. Based on the results from this one trial, some authorities recommend that cephalad-caudad blunt extension be utilized rather than transverse blunt extension.3

Closing the uterine incision—One or two layers?

In the recent Cochrane meta-analysis, researchers compared outcomes of single-layer and two-layer closure of the uterine incision in 14 studies involving 13,890 women.1 There was no difference in rates of febrile morbidity (5.0% vs 5.1%), wound infection (9.4% vs 9.5%), or blood transfusion (2.1% vs 2.4%) between the two techniques. Authors of another systematic review of 20 trials of single- versus double-layer closure of the uterine incision concluded that, based on the available evidence from randomized trials, single- and double-layer closure appeared to produce similar outcomes.14 These authors cautioned, however, that based on nonrandomized studies, single layer closure might be associated with an increased risk of uterine rupture in a subsequent pregnancy.15,16

A uterine incision that was closed with a locked single-layer closure may be at an especially high risk of rupture during a subsequent trial of labor. In one analysis of relevant reports with heterogeneous study designs, the risk of uterine rupture during a trial of labor after a prior cesarean was 1.8% with a double-layer closure, 3.5% with an unlocked single-layer closure, and 6.2% with a locked single-layer closure.17 My perspective is that a double-layer closure generally is preferred because in a future pregnancy with a planned vaginal delivery, the double-layer closure may be associated with a lower rate of uterine rupture.

Some authorities recommend single-layer uterine closure if the patient is sure that she has no future plans to conceive. For example, a woman who is undergoing a tubal ligation at the time of cesarean delivery may be an optimal candidate for single-layer closure.3

Individualization and innovation in surgical care

Surgeons advance their skills by continually using the best evidence and advice from colleagues to guide changes in their practice. Many clinical situations present unique combinations of medical and anatomic problems, and surgeons need to use both creativity and expert judgment to solve these unique problems. Surgical choices that are guided by both the best evidence and hard-won clinical experience will result in optimal patient outcomes.

Share your thoughts on this article! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

1. Dodd JM, Anderson ER, Gates S, Grivell RM. Surgical techniques for uterine incision and uterine closure at the time of cesarean section. Cochrane Database Sys Rev. 2014;7(3):CD004732.

2. Berghella V, Baxter JK, Chauhan SP. Evidence-based surgery for cesarean delivery. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2005;193(5):1607–1617.

3. Dahlke JD, Mendez-Figueroa H, Rouse DJ, Berghella V, Baxter JK, Chauhan SP. Evidence-based surgery for cesarean delivery: an updated systematic review. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2013;209(4):294–306.

4. Hohlagschwandtner M, Ruecklinger E, Husslein P, Joura EA. Is the formation of a bladder flap at cesarean necessary? A randomized trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2001;98(6):1089–1092.

5. Malvasi A, Tinelli A, Guido M, et al. Effect of avoiding bladder flap formation in caesarean section on repeat caesarean delivery Eur J Obstet Gynecol. 2011;159(2):300–304.

6. Tuuli MG, Obido AO, Fogertey P, Roehl K, Stamilio D, Macones GA. Utility of the bladder flap at cesarean delivery. A randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2012;119(4):815–821.

7. Cahill AG, Stout MJ, Stamillo DM, Odibo AO, Peipert JF, Macones GA. Risk factors for bladder injury in patients with a prior hysterotomy. Obstet Gynecol. 2008;112(1):116–120.

8. Holmgren G, Sjoholm L, Stark M. The Misgav-Ladach method for cesarean section: method description. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 1999;78(7):615–621.

9. Wallin G, Fall O. Modified Joel-Cohen technique for cesarean delivery. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1999;106(3):221–226.

10. Gilstrap LC, Cunningham FG, Van Dorsten JP, eds. Operative Obstetrics, 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw Hill; 2002.

11. C SAFE. http://www.csafe.us/. Trumbull, CT: CooperSurgical, Inc.

12. Saad AF, Rahman M, Costantine MM, Saade GR. Blunt versus sharp uterine incision expansion during low transverse cesarean delivery: a metaanalysis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2014;211(6):684.e1–e11.

13. Cromi A, Ghezzi F, Di Naro E, Siesto G, Loverro G, Bolis P. Blunt expansion of the low transverse uterine incision at cesarean delivery: a randomized comparison of 2 techniques. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2008;199(3):292.e1–e6.

14. Roberge S, Demers S, Berghella V, Chaillet N, Moore L, Bujold E. Impact of single- and double-layer closure on adverse outcomes and uterine scar defect: a systematic review and metaanalysis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2014; 211(5):453–460.

15. Yasmin S, Sadaf J, Fatima N. Impact of methods for uterine incision closure on repeat cesarean section scar of lower uterine segment. J Coll Physicians Surg Pak. 2011;21(9): 522–526.

16. Bujold E, Mehta SH, Bujold C, Gauthier RJ. Interdelivery interval and uterine rupture. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2002;187(5): 1199–1202.

17. Roberge S, Chaillet N, Boutin A, et al. Single- versus double-layer closure of the hysterotomy incision during cesarean delivery and risk of uterine rupture. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2011;115(1): 5–10.

1. Dodd JM, Anderson ER, Gates S, Grivell RM. Surgical techniques for uterine incision and uterine closure at the time of cesarean section. Cochrane Database Sys Rev. 2014;7(3):CD004732.

2. Berghella V, Baxter JK, Chauhan SP. Evidence-based surgery for cesarean delivery. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2005;193(5):1607–1617.

3. Dahlke JD, Mendez-Figueroa H, Rouse DJ, Berghella V, Baxter JK, Chauhan SP. Evidence-based surgery for cesarean delivery: an updated systematic review. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2013;209(4):294–306.

4. Hohlagschwandtner M, Ruecklinger E, Husslein P, Joura EA. Is the formation of a bladder flap at cesarean necessary? A randomized trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2001;98(6):1089–1092.

5. Malvasi A, Tinelli A, Guido M, et al. Effect of avoiding bladder flap formation in caesarean section on repeat caesarean delivery Eur J Obstet Gynecol. 2011;159(2):300–304.

6. Tuuli MG, Obido AO, Fogertey P, Roehl K, Stamilio D, Macones GA. Utility of the bladder flap at cesarean delivery. A randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2012;119(4):815–821.

7. Cahill AG, Stout MJ, Stamillo DM, Odibo AO, Peipert JF, Macones GA. Risk factors for bladder injury in patients with a prior hysterotomy. Obstet Gynecol. 2008;112(1):116–120.

8. Holmgren G, Sjoholm L, Stark M. The Misgav-Ladach method for cesarean section: method description. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 1999;78(7):615–621.

9. Wallin G, Fall O. Modified Joel-Cohen technique for cesarean delivery. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1999;106(3):221–226.

10. Gilstrap LC, Cunningham FG, Van Dorsten JP, eds. Operative Obstetrics, 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw Hill; 2002.

11. C SAFE. http://www.csafe.us/. Trumbull, CT: CooperSurgical, Inc.

12. Saad AF, Rahman M, Costantine MM, Saade GR. Blunt versus sharp uterine incision expansion during low transverse cesarean delivery: a metaanalysis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2014;211(6):684.e1–e11.

13. Cromi A, Ghezzi F, Di Naro E, Siesto G, Loverro G, Bolis P. Blunt expansion of the low transverse uterine incision at cesarean delivery: a randomized comparison of 2 techniques. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2008;199(3):292.e1–e6.

14. Roberge S, Demers S, Berghella V, Chaillet N, Moore L, Bujold E. Impact of single- and double-layer closure on adverse outcomes and uterine scar defect: a systematic review and metaanalysis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2014; 211(5):453–460.

15. Yasmin S, Sadaf J, Fatima N. Impact of methods for uterine incision closure on repeat cesarean section scar of lower uterine segment. J Coll Physicians Surg Pak. 2011;21(9): 522–526.

16. Bujold E, Mehta SH, Bujold C, Gauthier RJ. Interdelivery interval and uterine rupture. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2002;187(5): 1199–1202.

17. Roberge S, Chaillet N, Boutin A, et al. Single- versus double-layer closure of the hysterotomy incision during cesarean delivery and risk of uterine rupture. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2011;115(1): 5–10.

Optimal pharmacologic treatment of nausea and vomiting of pregnancy

CASE: Pregnant patient seeks medication for her NVP

A 23-year-old G1P0 woman at 9 weeks’ gestation presents to your office with nausea and vomiting that is interfering with work. She has tried many changes in her daily habits. She has tried eating small, frequent meals; snacking on nuts and crackers; using lemon-scented products; and avoiding coffee and strong odors. Following an evaluation you diagnose nausea and vomiting of pregnancy (NVP). She asks, “Is there a medication for my nausea that is safe for my baby?”

Nausea with or without vomiting is a common problem for pregnant women between 6 and 14 weeks of gestation. In one study, nausea with or without vomiting was reported by 69% of patients and resulted in pharmacologic treatment in 15%.1 In a Cochrane review of NVP, investigators analyzed 37 trials involving treatments such as acupressure, acustimulation, acupuncture, ginger, chamomile, lemon oil, vitamin B6, and antiemetic medications. The authors concluded, “There is a lack of high-quality evidence to support any particular intervention.”2 Clinicians are challenged to effectively treat the symptoms of NVP and simultaneously to minimize the risk that the fetus will be exposed to a teratogen during the first trimester, a vulnerable period in organ development.

In this editorial, I briefly review nonpharmacologic options for NVP, but focus on current pharmacologic treatments. Of those available to ObGyns, what is the best first-choice treatment given recent and accumulated data regarding associated congenital anomalies?

Nonpharmacologic treatment

Although the authors of the Cochrane review did not identify high-quality evidence to support nonpharmacologic interventions, results of multiple randomized trials have demonstrated that ginger is effective in reducing pregnancy-associated nausea and vomiting.3 Ginger treatment is recommended at doses of 250 mg in capsules or syrup four times daily.

First-line pharmacologic treatment: Doxylamine plus pyridoxine

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has approved the combination of doxylamine plus pyridoxine (vitamin B6) in a delayed-release formulation for treatment of NVP (Diclegis). Doxylamine is an antihistamine that blocks H1-receptor sites in the chemoreceptor trigger zone. It also diminishes vestibular stimulation and depresses labyrinthine activity through central anticholinergic activity. Its elimination half-life is 10 to 12 hours (Lexicomp). Each tablet contains doxylamine 10 mg and pyridoxine 10 mg. The starting dose is 2 tablets at bedtime.

If the woman has persistent symptoms, a third tablet is added, to be taken in the morning. If symptoms continue, a fourth tablet is recommended to be taken in the afternoon. In a large, randomized clinical trial, doxylamine-pyridoxine treatment reduced nausea, vomiting, and retching and improved perceived quality of life compared with placebo.4 The FDA assigned doxylamine-pyridoxine pregnancy category A because of the extensive evidence that it does not cause an increase in fetal malformations.5,6

If the delayed-release doxylamine-pyridoxine formulation (Diclegis) is not available to the patient, alternative formulations of doxylamine and pyridoxine can be prescribed. Pyridoxine is widely available over the counter as 25-mg tablets, and one tablet can be prescribed two or three times daily. Doxylamine is available as a chewable prescription medicine in 5-mg tablets (Aldex AN) and two tablets can be prescribed two or three times daily. Doxylamine is also available as a 25-mg over-the-counter tablet in Unisom SleepTabs. One-half tablet can be prescribed two or three times daily. The patient should be alerted that Unisom SleepGels contain diphenhydramine, not doxylamine.

Second-line pharmacologic treatment

Metoclopramide Metoclopramide is a dopamine antagonist. It enhances upper gastrointestinal motility, accelerates gastric emptying, and increases lower esophageal sphincter tone. At higher doses it blocks serotonin receptors in the chemoreceptor trigger zone. Its elimination half-life is 5 to 6 hours (Lexicomp). There are no large, randomized, placebo-controlled trials of oral metoclopramide for the treatment of nausea and vomiting of early pregnancy.

I am recommending metoclopramide as a second-line treatment for NVP because it appears to be effective and is not known to be associated with an increased risk of congenital malformations. Metoclopramide is widely used to prevent and treat intraoperative and postoperative nausea associated with cesarean delivery.7 In addition, intravenous (IV) metoclopramide is commonly used to treat women hospitalized with hyperemesis gravidarum. Results of randomized clinical trials demonstrate that when used to treat hyperemesis gravidarum, IV metoclopramide (10 mg every 8 hours) has similar efficacy to IV ondansetron (4 mg every 8 hours)8 and IV promethazine (25 mg every 8 hours).9 When using metoclopramide as an oral treatment for NVP, 10 mg every 8 hours is a commonly recommended regimen.

The FDA has assigned metoclopramide to pregnancy category B, which indicates that there is no evidence of fetal risk. Studies from Israel and Denmark show that metoclopramide is not associated with an increased risk of congenital malformations. In the study from Israel, among 3,458 infants born to women who had filled a prescription for metoclopramide during the first trimester of pregnancy, there was no increase in major congenital malformations, low birth weight, preterm delivery, or perinatal death.10 In the study from Denmark, among 28,486 infants born to mothers who had filled a prescription for metoclopramide in the first trimester there was no increase in congenital malformations or any of 20 individual categories of malformations, including neural tube defects, transposition of the great vessels, ventricular septal defect, atrial septal defect, tetralogy of Fallot, coarctation of the aorta, cleft lip or palate, anorectal atresia/stenosis, or limb reduction.11 The results of these two large studies are reassuring that metoclopramide is not associated with an increased risk of congenital malformations.

Metoclopramide can cause tardive dyskinesia, a serious movement disorder that may be irreversible with discontinuation of the drug. This risk increases with dose and length of treatment. The FDA recommends that clinicians avoid the use of metoclopramide for more than 12 weeks.

Third-line pharmacologic treatment: Ondansetron

In the United States ondansetron is commonly used to treat NVP.12 The drug is a selective 5-HT3 antagonist that blocks serotonin action in the central nervous system chemoreceptor trigger zone. The elimination half-life of ondansetron is 3 to 6 hours (Lexicomp).

The frequent use of ondansetron may be due, in part, to the perception that it is a very effective antiemetic. For example, in one small clinical trial, ondansetron 4 mg every 8 hours was reported to be superior to a combination of pyridoxine 25 mg every 8 hours plus doxylamine 12.5 mg every 8 hours.13 (Note that the pyridoxine and doxylamine tablets used in this trial were not in a combination delayed-release formulation.) I am recommending ondansetron as a third-line treatment for NVP because, although it is effective, it may be associated with an increased risk of fetal cardiac anomalies.

Is ondansetron associated with cardiac malformations?

The FDA has assigned ondansetron to pregnancy category B; however, there is concern that it may be associated with congenital heart defects. In a recent study of 1,349 infants born to Swedish women who had filled a prescription for ondansetron in early pregnancy, a significantly increased risk of cardiovascular defect (odds ratio [OR], 1.62; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.04−2.14) and cardiac septum defect (OR, 2.05; 95% CI, 1.19−3.28) was reported.14 The cardiac anomalies were mostly atrial septal or ventricular septal defects.

In a second study, reported as an abstract, authors analyzed congenital malformations in 1,248 infants born to Danish women who filled a prescription for ondansetron in early pregnancy. These authors also found an increased risk of a congenital heart malformation (OR, 2.0; 95% CI, 1.3−3.1).15

A US case-control study showed an association between ondansetron use and cleft palate.1 The Swedish14 and Danish15 studies reported above did not find an association between ondansetron use and cleft palate.

The FDA issued a warning in June 2012 that at a dose of 32 mg, administered intravenously, ondansetron may prolong the QT interval and result in a potentially fatal heart arrhythmia, torsades de pointes.16 In the announcement the FDA did not alter the recommendations for oral dosing because there is no strong evidence that oral dosing is associated with clinically significant arrhythmias. Authors of a recent systematic review concluded that IV administration of large doses of ondansetron may cause cardiac arrhythmias, especially in patients with cardiac disease and those taking other drugs that prolong the QT interval, but that a single oral dose of ondansetron does not have a significant risk of causing an arrhythmia.17

Health Canada18 has advised that many commonly prescribed medications increase serotonin activity. When multiple drugs that each increase serotonin activity are prescribed in combination, the risk of serotonin syndrome is increased. Serotonin syndrome results in hyperthermia, agitation, tachycardia, and muscle twitching and can be fatal. Ondansetron was specifically mentioned in the Health Canada warning, but a search of the literature revealed very few reported cases of ondansetron being implicated in the serotonin syndrome.19

My bottom-line recommendations

NVP is a common obstetric problem. When oral pharmacologic therapy is indicated, first-line treatment should be with the FDA-approved combination of doxylamine-pyridoxine because it is both effective and associated with no known increased risk of congenital malformations. An effective second-line agent is metoclopramide. Based on very limited data, metoclopramide appears effective and is not associated with an increased risk of congenital malformations. However, it is not FDA approved for treatment of NVP. Ondansetron appears to be effective but its use in early pregnancy may be associated with congenital anomalies. Consequently, ondansetron should not be used to treat NVP unless first- and second-line treatments have been ineffective to treat the patient’s symptoms.

INSTANT POLL

Which of the following pharmacologic treatments of nausea with or without vomiting during pregnancy is your first-line medication choice?

• Ondansetron

• Metoclopramide

• Doxylamine-pyridoxine

• Meclizine Promethazine

• Trimethobenzamide

Visit the Quick Poll on the homepage, give your answer, and then see how other ObGyns have answered.

Share your thoughts on this article! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

1. Anderka M, Mitchell AA, Louik C, Werler MMA, Hernandez-Diaz S, Rasmussen SA; National Birth Defects Prevention Study. Medications used to treat nausea and vomiting of pregnancy and the risk of selected birth defects. Birth Defects Res A Clin Mol Teratol. 2012;94(1):22–30.

2. Matthews A, Haas Dm, O’Mathuna DP, Dowswell T, Doyle M. Interventions for nausea and vomiting in early pregnancy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;(3):CD007575.

3. Borrelli F, Capasso R, Aviello G, Pittler MH, Izzo AA. Effectiveness and safety of ginger in the treatment of pregnancy-induced nausea and vomiting. Obstet Gynecol. 2005;105(4):849–856.

4. Koren G, Clark S, Hankins GD, et al. Effectiveness of delayed-release doxylamine and pyridoxine for nausea and vomiting of pregnancy: a randomized placebo controlled trial. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2010;203(6):571.e1–7.

5. Einarson TR, Leeder JS, Koren G. A method for meta-analysis of epidemiologic studies. Drug Intell Clin Pharm. 1988;22(10):813–824.

6. McKeigue PM, Lamm SH, Linn S, Kutcher JS. Bendectin and birth defects. I. A meta-analysis of the epidemiologic studies. Teratology. 1994;50(1):27–37.

7. Mishriky BM, Habib AS. Metoclopramide for nausea and vomiting prophylaxis during and after cesarean delivery: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Anaesth. 2012;108(3):374–383.

8. Abas MN, Tan PC, Azmi N, Omar SZ. Ondansetron compared with metoclopramide for hyperemesis gravidarum: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2014;123(6):1272–1279.

9. Tan PC, Khine PP, Vallikkannu N, Omar SZ. Promethazine compared with metoclopramide for hyperemesis gravidarum: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2010;115(5):975–981.

10. Matok I, Gorodischer R, Koren G, Sheiner E, Wiznitzer A, Levy A. The safety of metoclopramide use in the first trimester of pregnancy. N Engl J Med. 2009;360(24):2528–2535.

11. Pasternak B, Svanstrom H, Molgaard-Nielsen D, Melbye M, Hviid A. Metoclopramide in pregnancy and risk of major congenital malformations and fetal death. JAMA. 2013;310(15):1601–1611.

12. Koren G. Treating morning sickness in the United States—changes in prescribing are needed. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2014;211(6):602–606.

13. Oliveira LG, Capp SM, You WB, Riffenburgh RH, Carstairs SH. Ondansetron compared with doxylamine and pyridoxine for treatment of nausea in pregnancy : a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2014;124(4):735–742.

14. Danielsson B, Wikner BN, Kallen B. Use of ondansetron during pregnancy and congenital malformations in the infant. Reprod Toxicol. 2014;50:134–137.

15. Andersen JT, Jimenez-Solem E, Andersen NL, Poulsen HE. Ondansetron use in early pregnancy and the risk of congenital malformations—a registry based nationwide cohort study. Abstract presented at: 29th International Conference on Pharmacoepidemiology & Therapeutic Risk Management; August 25–28, 2013; Montreal, Canada. Abstract 25, Pregnancy Session 1. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2013;22(suppl 1):13–14.

16. US Food and Drug Administration. Ondansetron (Zofran) IV: drug safety communication - QT prolongation. http://www.fda.gov/Safety/MedWatch/SafetyInformation/SafetyAlertsforHumanMedicalProducts/ucm310219.htm. Published June 29, 2012. Accessed December 26, 2014.

17. Freedman SB, Uleryk E, Rumantir M, Finkelstein Y. Ondansetron and the risk of cardiac arrhythmias: a systematic review and postmarketing analysis. Ann Emerg Med. 2014;64(1):19–25.

18. Health Canada. Canadian Adverse Reaction Newsletter. 2003;13(3). http://www.hc-sc.gc.ca/dhp-mps/medeff/bulletin/carn-bcei_v13n3-eng.php. Published June 24, 2003. Accessed December 26, 2014.

19. Turkel SB, Nadala JG, Wincor MZ. Possible serotonin syndrome in association with 5-HT3 antagonist agents. Psychosomatics. 2001;42(3):258–260.

CASE: Pregnant patient seeks medication for her NVP

A 23-year-old G1P0 woman at 9 weeks’ gestation presents to your office with nausea and vomiting that is interfering with work. She has tried many changes in her daily habits. She has tried eating small, frequent meals; snacking on nuts and crackers; using lemon-scented products; and avoiding coffee and strong odors. Following an evaluation you diagnose nausea and vomiting of pregnancy (NVP). She asks, “Is there a medication for my nausea that is safe for my baby?”

Nausea with or without vomiting is a common problem for pregnant women between 6 and 14 weeks of gestation. In one study, nausea with or without vomiting was reported by 69% of patients and resulted in pharmacologic treatment in 15%.1 In a Cochrane review of NVP, investigators analyzed 37 trials involving treatments such as acupressure, acustimulation, acupuncture, ginger, chamomile, lemon oil, vitamin B6, and antiemetic medications. The authors concluded, “There is a lack of high-quality evidence to support any particular intervention.”2 Clinicians are challenged to effectively treat the symptoms of NVP and simultaneously to minimize the risk that the fetus will be exposed to a teratogen during the first trimester, a vulnerable period in organ development.

In this editorial, I briefly review nonpharmacologic options for NVP, but focus on current pharmacologic treatments. Of those available to ObGyns, what is the best first-choice treatment given recent and accumulated data regarding associated congenital anomalies?

Nonpharmacologic treatment

Although the authors of the Cochrane review did not identify high-quality evidence to support nonpharmacologic interventions, results of multiple randomized trials have demonstrated that ginger is effective in reducing pregnancy-associated nausea and vomiting.3 Ginger treatment is recommended at doses of 250 mg in capsules or syrup four times daily.

First-line pharmacologic treatment: Doxylamine plus pyridoxine

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has approved the combination of doxylamine plus pyridoxine (vitamin B6) in a delayed-release formulation for treatment of NVP (Diclegis). Doxylamine is an antihistamine that blocks H1-receptor sites in the chemoreceptor trigger zone. It also diminishes vestibular stimulation and depresses labyrinthine activity through central anticholinergic activity. Its elimination half-life is 10 to 12 hours (Lexicomp). Each tablet contains doxylamine 10 mg and pyridoxine 10 mg. The starting dose is 2 tablets at bedtime.

If the woman has persistent symptoms, a third tablet is added, to be taken in the morning. If symptoms continue, a fourth tablet is recommended to be taken in the afternoon. In a large, randomized clinical trial, doxylamine-pyridoxine treatment reduced nausea, vomiting, and retching and improved perceived quality of life compared with placebo.4 The FDA assigned doxylamine-pyridoxine pregnancy category A because of the extensive evidence that it does not cause an increase in fetal malformations.5,6

If the delayed-release doxylamine-pyridoxine formulation (Diclegis) is not available to the patient, alternative formulations of doxylamine and pyridoxine can be prescribed. Pyridoxine is widely available over the counter as 25-mg tablets, and one tablet can be prescribed two or three times daily. Doxylamine is available as a chewable prescription medicine in 5-mg tablets (Aldex AN) and two tablets can be prescribed two or three times daily. Doxylamine is also available as a 25-mg over-the-counter tablet in Unisom SleepTabs. One-half tablet can be prescribed two or three times daily. The patient should be alerted that Unisom SleepGels contain diphenhydramine, not doxylamine.

Second-line pharmacologic treatment

Metoclopramide Metoclopramide is a dopamine antagonist. It enhances upper gastrointestinal motility, accelerates gastric emptying, and increases lower esophageal sphincter tone. At higher doses it blocks serotonin receptors in the chemoreceptor trigger zone. Its elimination half-life is 5 to 6 hours (Lexicomp). There are no large, randomized, placebo-controlled trials of oral metoclopramide for the treatment of nausea and vomiting of early pregnancy.

I am recommending metoclopramide as a second-line treatment for NVP because it appears to be effective and is not known to be associated with an increased risk of congenital malformations. Metoclopramide is widely used to prevent and treat intraoperative and postoperative nausea associated with cesarean delivery.7 In addition, intravenous (IV) metoclopramide is commonly used to treat women hospitalized with hyperemesis gravidarum. Results of randomized clinical trials demonstrate that when used to treat hyperemesis gravidarum, IV metoclopramide (10 mg every 8 hours) has similar efficacy to IV ondansetron (4 mg every 8 hours)8 and IV promethazine (25 mg every 8 hours).9 When using metoclopramide as an oral treatment for NVP, 10 mg every 8 hours is a commonly recommended regimen.

The FDA has assigned metoclopramide to pregnancy category B, which indicates that there is no evidence of fetal risk. Studies from Israel and Denmark show that metoclopramide is not associated with an increased risk of congenital malformations. In the study from Israel, among 3,458 infants born to women who had filled a prescription for metoclopramide during the first trimester of pregnancy, there was no increase in major congenital malformations, low birth weight, preterm delivery, or perinatal death.10 In the study from Denmark, among 28,486 infants born to mothers who had filled a prescription for metoclopramide in the first trimester there was no increase in congenital malformations or any of 20 individual categories of malformations, including neural tube defects, transposition of the great vessels, ventricular septal defect, atrial septal defect, tetralogy of Fallot, coarctation of the aorta, cleft lip or palate, anorectal atresia/stenosis, or limb reduction.11 The results of these two large studies are reassuring that metoclopramide is not associated with an increased risk of congenital malformations.

Metoclopramide can cause tardive dyskinesia, a serious movement disorder that may be irreversible with discontinuation of the drug. This risk increases with dose and length of treatment. The FDA recommends that clinicians avoid the use of metoclopramide for more than 12 weeks.

Third-line pharmacologic treatment: Ondansetron

In the United States ondansetron is commonly used to treat NVP.12 The drug is a selective 5-HT3 antagonist that blocks serotonin action in the central nervous system chemoreceptor trigger zone. The elimination half-life of ondansetron is 3 to 6 hours (Lexicomp).

The frequent use of ondansetron may be due, in part, to the perception that it is a very effective antiemetic. For example, in one small clinical trial, ondansetron 4 mg every 8 hours was reported to be superior to a combination of pyridoxine 25 mg every 8 hours plus doxylamine 12.5 mg every 8 hours.13 (Note that the pyridoxine and doxylamine tablets used in this trial were not in a combination delayed-release formulation.) I am recommending ondansetron as a third-line treatment for NVP because, although it is effective, it may be associated with an increased risk of fetal cardiac anomalies.

Is ondansetron associated with cardiac malformations?

The FDA has assigned ondansetron to pregnancy category B; however, there is concern that it may be associated with congenital heart defects. In a recent study of 1,349 infants born to Swedish women who had filled a prescription for ondansetron in early pregnancy, a significantly increased risk of cardiovascular defect (odds ratio [OR], 1.62; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.04−2.14) and cardiac septum defect (OR, 2.05; 95% CI, 1.19−3.28) was reported.14 The cardiac anomalies were mostly atrial septal or ventricular septal defects.

In a second study, reported as an abstract, authors analyzed congenital malformations in 1,248 infants born to Danish women who filled a prescription for ondansetron in early pregnancy. These authors also found an increased risk of a congenital heart malformation (OR, 2.0; 95% CI, 1.3−3.1).15

A US case-control study showed an association between ondansetron use and cleft palate.1 The Swedish14 and Danish15 studies reported above did not find an association between ondansetron use and cleft palate.

The FDA issued a warning in June 2012 that at a dose of 32 mg, administered intravenously, ondansetron may prolong the QT interval and result in a potentially fatal heart arrhythmia, torsades de pointes.16 In the announcement the FDA did not alter the recommendations for oral dosing because there is no strong evidence that oral dosing is associated with clinically significant arrhythmias. Authors of a recent systematic review concluded that IV administration of large doses of ondansetron may cause cardiac arrhythmias, especially in patients with cardiac disease and those taking other drugs that prolong the QT interval, but that a single oral dose of ondansetron does not have a significant risk of causing an arrhythmia.17

Health Canada18 has advised that many commonly prescribed medications increase serotonin activity. When multiple drugs that each increase serotonin activity are prescribed in combination, the risk of serotonin syndrome is increased. Serotonin syndrome results in hyperthermia, agitation, tachycardia, and muscle twitching and can be fatal. Ondansetron was specifically mentioned in the Health Canada warning, but a search of the literature revealed very few reported cases of ondansetron being implicated in the serotonin syndrome.19

My bottom-line recommendations

NVP is a common obstetric problem. When oral pharmacologic therapy is indicated, first-line treatment should be with the FDA-approved combination of doxylamine-pyridoxine because it is both effective and associated with no known increased risk of congenital malformations. An effective second-line agent is metoclopramide. Based on very limited data, metoclopramide appears effective and is not associated with an increased risk of congenital malformations. However, it is not FDA approved for treatment of NVP. Ondansetron appears to be effective but its use in early pregnancy may be associated with congenital anomalies. Consequently, ondansetron should not be used to treat NVP unless first- and second-line treatments have been ineffective to treat the patient’s symptoms.

INSTANT POLL

Which of the following pharmacologic treatments of nausea with or without vomiting during pregnancy is your first-line medication choice?

• Ondansetron

• Metoclopramide

• Doxylamine-pyridoxine

• Meclizine Promethazine

• Trimethobenzamide

Visit the Quick Poll on the homepage, give your answer, and then see how other ObGyns have answered.

Share your thoughts on this article! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

CASE: Pregnant patient seeks medication for her NVP

A 23-year-old G1P0 woman at 9 weeks’ gestation presents to your office with nausea and vomiting that is interfering with work. She has tried many changes in her daily habits. She has tried eating small, frequent meals; snacking on nuts and crackers; using lemon-scented products; and avoiding coffee and strong odors. Following an evaluation you diagnose nausea and vomiting of pregnancy (NVP). She asks, “Is there a medication for my nausea that is safe for my baby?”

Nausea with or without vomiting is a common problem for pregnant women between 6 and 14 weeks of gestation. In one study, nausea with or without vomiting was reported by 69% of patients and resulted in pharmacologic treatment in 15%.1 In a Cochrane review of NVP, investigators analyzed 37 trials involving treatments such as acupressure, acustimulation, acupuncture, ginger, chamomile, lemon oil, vitamin B6, and antiemetic medications. The authors concluded, “There is a lack of high-quality evidence to support any particular intervention.”2 Clinicians are challenged to effectively treat the symptoms of NVP and simultaneously to minimize the risk that the fetus will be exposed to a teratogen during the first trimester, a vulnerable period in organ development.

In this editorial, I briefly review nonpharmacologic options for NVP, but focus on current pharmacologic treatments. Of those available to ObGyns, what is the best first-choice treatment given recent and accumulated data regarding associated congenital anomalies?

Nonpharmacologic treatment

Although the authors of the Cochrane review did not identify high-quality evidence to support nonpharmacologic interventions, results of multiple randomized trials have demonstrated that ginger is effective in reducing pregnancy-associated nausea and vomiting.3 Ginger treatment is recommended at doses of 250 mg in capsules or syrup four times daily.

First-line pharmacologic treatment: Doxylamine plus pyridoxine

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has approved the combination of doxylamine plus pyridoxine (vitamin B6) in a delayed-release formulation for treatment of NVP (Diclegis). Doxylamine is an antihistamine that blocks H1-receptor sites in the chemoreceptor trigger zone. It also diminishes vestibular stimulation and depresses labyrinthine activity through central anticholinergic activity. Its elimination half-life is 10 to 12 hours (Lexicomp). Each tablet contains doxylamine 10 mg and pyridoxine 10 mg. The starting dose is 2 tablets at bedtime.

If the woman has persistent symptoms, a third tablet is added, to be taken in the morning. If symptoms continue, a fourth tablet is recommended to be taken in the afternoon. In a large, randomized clinical trial, doxylamine-pyridoxine treatment reduced nausea, vomiting, and retching and improved perceived quality of life compared with placebo.4 The FDA assigned doxylamine-pyridoxine pregnancy category A because of the extensive evidence that it does not cause an increase in fetal malformations.5,6

If the delayed-release doxylamine-pyridoxine formulation (Diclegis) is not available to the patient, alternative formulations of doxylamine and pyridoxine can be prescribed. Pyridoxine is widely available over the counter as 25-mg tablets, and one tablet can be prescribed two or three times daily. Doxylamine is available as a chewable prescription medicine in 5-mg tablets (Aldex AN) and two tablets can be prescribed two or three times daily. Doxylamine is also available as a 25-mg over-the-counter tablet in Unisom SleepTabs. One-half tablet can be prescribed two or three times daily. The patient should be alerted that Unisom SleepGels contain diphenhydramine, not doxylamine.

Second-line pharmacologic treatment

Metoclopramide Metoclopramide is a dopamine antagonist. It enhances upper gastrointestinal motility, accelerates gastric emptying, and increases lower esophageal sphincter tone. At higher doses it blocks serotonin receptors in the chemoreceptor trigger zone. Its elimination half-life is 5 to 6 hours (Lexicomp). There are no large, randomized, placebo-controlled trials of oral metoclopramide for the treatment of nausea and vomiting of early pregnancy.

I am recommending metoclopramide as a second-line treatment for NVP because it appears to be effective and is not known to be associated with an increased risk of congenital malformations. Metoclopramide is widely used to prevent and treat intraoperative and postoperative nausea associated with cesarean delivery.7 In addition, intravenous (IV) metoclopramide is commonly used to treat women hospitalized with hyperemesis gravidarum. Results of randomized clinical trials demonstrate that when used to treat hyperemesis gravidarum, IV metoclopramide (10 mg every 8 hours) has similar efficacy to IV ondansetron (4 mg every 8 hours)8 and IV promethazine (25 mg every 8 hours).9 When using metoclopramide as an oral treatment for NVP, 10 mg every 8 hours is a commonly recommended regimen.

The FDA has assigned metoclopramide to pregnancy category B, which indicates that there is no evidence of fetal risk. Studies from Israel and Denmark show that metoclopramide is not associated with an increased risk of congenital malformations. In the study from Israel, among 3,458 infants born to women who had filled a prescription for metoclopramide during the first trimester of pregnancy, there was no increase in major congenital malformations, low birth weight, preterm delivery, or perinatal death.10 In the study from Denmark, among 28,486 infants born to mothers who had filled a prescription for metoclopramide in the first trimester there was no increase in congenital malformations or any of 20 individual categories of malformations, including neural tube defects, transposition of the great vessels, ventricular septal defect, atrial septal defect, tetralogy of Fallot, coarctation of the aorta, cleft lip or palate, anorectal atresia/stenosis, or limb reduction.11 The results of these two large studies are reassuring that metoclopramide is not associated with an increased risk of congenital malformations.

Metoclopramide can cause tardive dyskinesia, a serious movement disorder that may be irreversible with discontinuation of the drug. This risk increases with dose and length of treatment. The FDA recommends that clinicians avoid the use of metoclopramide for more than 12 weeks.

Third-line pharmacologic treatment: Ondansetron

In the United States ondansetron is commonly used to treat NVP.12 The drug is a selective 5-HT3 antagonist that blocks serotonin action in the central nervous system chemoreceptor trigger zone. The elimination half-life of ondansetron is 3 to 6 hours (Lexicomp).

The frequent use of ondansetron may be due, in part, to the perception that it is a very effective antiemetic. For example, in one small clinical trial, ondansetron 4 mg every 8 hours was reported to be superior to a combination of pyridoxine 25 mg every 8 hours plus doxylamine 12.5 mg every 8 hours.13 (Note that the pyridoxine and doxylamine tablets used in this trial were not in a combination delayed-release formulation.) I am recommending ondansetron as a third-line treatment for NVP because, although it is effective, it may be associated with an increased risk of fetal cardiac anomalies.

Is ondansetron associated with cardiac malformations?

The FDA has assigned ondansetron to pregnancy category B; however, there is concern that it may be associated with congenital heart defects. In a recent study of 1,349 infants born to Swedish women who had filled a prescription for ondansetron in early pregnancy, a significantly increased risk of cardiovascular defect (odds ratio [OR], 1.62; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.04−2.14) and cardiac septum defect (OR, 2.05; 95% CI, 1.19−3.28) was reported.14 The cardiac anomalies were mostly atrial septal or ventricular septal defects.

In a second study, reported as an abstract, authors analyzed congenital malformations in 1,248 infants born to Danish women who filled a prescription for ondansetron in early pregnancy. These authors also found an increased risk of a congenital heart malformation (OR, 2.0; 95% CI, 1.3−3.1).15

A US case-control study showed an association between ondansetron use and cleft palate.1 The Swedish14 and Danish15 studies reported above did not find an association between ondansetron use and cleft palate.

The FDA issued a warning in June 2012 that at a dose of 32 mg, administered intravenously, ondansetron may prolong the QT interval and result in a potentially fatal heart arrhythmia, torsades de pointes.16 In the announcement the FDA did not alter the recommendations for oral dosing because there is no strong evidence that oral dosing is associated with clinically significant arrhythmias. Authors of a recent systematic review concluded that IV administration of large doses of ondansetron may cause cardiac arrhythmias, especially in patients with cardiac disease and those taking other drugs that prolong the QT interval, but that a single oral dose of ondansetron does not have a significant risk of causing an arrhythmia.17

Health Canada18 has advised that many commonly prescribed medications increase serotonin activity. When multiple drugs that each increase serotonin activity are prescribed in combination, the risk of serotonin syndrome is increased. Serotonin syndrome results in hyperthermia, agitation, tachycardia, and muscle twitching and can be fatal. Ondansetron was specifically mentioned in the Health Canada warning, but a search of the literature revealed very few reported cases of ondansetron being implicated in the serotonin syndrome.19

My bottom-line recommendations

NVP is a common obstetric problem. When oral pharmacologic therapy is indicated, first-line treatment should be with the FDA-approved combination of doxylamine-pyridoxine because it is both effective and associated with no known increased risk of congenital malformations. An effective second-line agent is metoclopramide. Based on very limited data, metoclopramide appears effective and is not associated with an increased risk of congenital malformations. However, it is not FDA approved for treatment of NVP. Ondansetron appears to be effective but its use in early pregnancy may be associated with congenital anomalies. Consequently, ondansetron should not be used to treat NVP unless first- and second-line treatments have been ineffective to treat the patient’s symptoms.

INSTANT POLL

Which of the following pharmacologic treatments of nausea with or without vomiting during pregnancy is your first-line medication choice?

• Ondansetron

• Metoclopramide

• Doxylamine-pyridoxine

• Meclizine Promethazine

• Trimethobenzamide

Visit the Quick Poll on the homepage, give your answer, and then see how other ObGyns have answered.

Share your thoughts on this article! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

1. Anderka M, Mitchell AA, Louik C, Werler MMA, Hernandez-Diaz S, Rasmussen SA; National Birth Defects Prevention Study. Medications used to treat nausea and vomiting of pregnancy and the risk of selected birth defects. Birth Defects Res A Clin Mol Teratol. 2012;94(1):22–30.

2. Matthews A, Haas Dm, O’Mathuna DP, Dowswell T, Doyle M. Interventions for nausea and vomiting in early pregnancy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;(3):CD007575.

3. Borrelli F, Capasso R, Aviello G, Pittler MH, Izzo AA. Effectiveness and safety of ginger in the treatment of pregnancy-induced nausea and vomiting. Obstet Gynecol. 2005;105(4):849–856.

4. Koren G, Clark S, Hankins GD, et al. Effectiveness of delayed-release doxylamine and pyridoxine for nausea and vomiting of pregnancy: a randomized placebo controlled trial. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2010;203(6):571.e1–7.

5. Einarson TR, Leeder JS, Koren G. A method for meta-analysis of epidemiologic studies. Drug Intell Clin Pharm. 1988;22(10):813–824.

6. McKeigue PM, Lamm SH, Linn S, Kutcher JS. Bendectin and birth defects. I. A meta-analysis of the epidemiologic studies. Teratology. 1994;50(1):27–37.

7. Mishriky BM, Habib AS. Metoclopramide for nausea and vomiting prophylaxis during and after cesarean delivery: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Anaesth. 2012;108(3):374–383.

8. Abas MN, Tan PC, Azmi N, Omar SZ. Ondansetron compared with metoclopramide for hyperemesis gravidarum: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2014;123(6):1272–1279.

9. Tan PC, Khine PP, Vallikkannu N, Omar SZ. Promethazine compared with metoclopramide for hyperemesis gravidarum: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2010;115(5):975–981.

10. Matok I, Gorodischer R, Koren G, Sheiner E, Wiznitzer A, Levy A. The safety of metoclopramide use in the first trimester of pregnancy. N Engl J Med. 2009;360(24):2528–2535.

11. Pasternak B, Svanstrom H, Molgaard-Nielsen D, Melbye M, Hviid A. Metoclopramide in pregnancy and risk of major congenital malformations and fetal death. JAMA. 2013;310(15):1601–1611.

12. Koren G. Treating morning sickness in the United States—changes in prescribing are needed. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2014;211(6):602–606.

13. Oliveira LG, Capp SM, You WB, Riffenburgh RH, Carstairs SH. Ondansetron compared with doxylamine and pyridoxine for treatment of nausea in pregnancy : a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2014;124(4):735–742.

14. Danielsson B, Wikner BN, Kallen B. Use of ondansetron during pregnancy and congenital malformations in the infant. Reprod Toxicol. 2014;50:134–137.

15. Andersen JT, Jimenez-Solem E, Andersen NL, Poulsen HE. Ondansetron use in early pregnancy and the risk of congenital malformations—a registry based nationwide cohort study. Abstract presented at: 29th International Conference on Pharmacoepidemiology & Therapeutic Risk Management; August 25–28, 2013; Montreal, Canada. Abstract 25, Pregnancy Session 1. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2013;22(suppl 1):13–14.

16. US Food and Drug Administration. Ondansetron (Zofran) IV: drug safety communication - QT prolongation. http://www.fda.gov/Safety/MedWatch/SafetyInformation/SafetyAlertsforHumanMedicalProducts/ucm310219.htm. Published June 29, 2012. Accessed December 26, 2014.

17. Freedman SB, Uleryk E, Rumantir M, Finkelstein Y. Ondansetron and the risk of cardiac arrhythmias: a systematic review and postmarketing analysis. Ann Emerg Med. 2014;64(1):19–25.

18. Health Canada. Canadian Adverse Reaction Newsletter. 2003;13(3). http://www.hc-sc.gc.ca/dhp-mps/medeff/bulletin/carn-bcei_v13n3-eng.php. Published June 24, 2003. Accessed December 26, 2014.

19. Turkel SB, Nadala JG, Wincor MZ. Possible serotonin syndrome in association with 5-HT3 antagonist agents. Psychosomatics. 2001;42(3):258–260.

1. Anderka M, Mitchell AA, Louik C, Werler MMA, Hernandez-Diaz S, Rasmussen SA; National Birth Defects Prevention Study. Medications used to treat nausea and vomiting of pregnancy and the risk of selected birth defects. Birth Defects Res A Clin Mol Teratol. 2012;94(1):22–30.

2. Matthews A, Haas Dm, O’Mathuna DP, Dowswell T, Doyle M. Interventions for nausea and vomiting in early pregnancy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;(3):CD007575.

3. Borrelli F, Capasso R, Aviello G, Pittler MH, Izzo AA. Effectiveness and safety of ginger in the treatment of pregnancy-induced nausea and vomiting. Obstet Gynecol. 2005;105(4):849–856.

4. Koren G, Clark S, Hankins GD, et al. Effectiveness of delayed-release doxylamine and pyridoxine for nausea and vomiting of pregnancy: a randomized placebo controlled trial. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2010;203(6):571.e1–7.

5. Einarson TR, Leeder JS, Koren G. A method for meta-analysis of epidemiologic studies. Drug Intell Clin Pharm. 1988;22(10):813–824.

6. McKeigue PM, Lamm SH, Linn S, Kutcher JS. Bendectin and birth defects. I. A meta-analysis of the epidemiologic studies. Teratology. 1994;50(1):27–37.

7. Mishriky BM, Habib AS. Metoclopramide for nausea and vomiting prophylaxis during and after cesarean delivery: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Anaesth. 2012;108(3):374–383.

8. Abas MN, Tan PC, Azmi N, Omar SZ. Ondansetron compared with metoclopramide for hyperemesis gravidarum: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2014;123(6):1272–1279.

9. Tan PC, Khine PP, Vallikkannu N, Omar SZ. Promethazine compared with metoclopramide for hyperemesis gravidarum: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2010;115(5):975–981.

10. Matok I, Gorodischer R, Koren G, Sheiner E, Wiznitzer A, Levy A. The safety of metoclopramide use in the first trimester of pregnancy. N Engl J Med. 2009;360(24):2528–2535.

11. Pasternak B, Svanstrom H, Molgaard-Nielsen D, Melbye M, Hviid A. Metoclopramide in pregnancy and risk of major congenital malformations and fetal death. JAMA. 2013;310(15):1601–1611.

12. Koren G. Treating morning sickness in the United States—changes in prescribing are needed. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2014;211(6):602–606.

13. Oliveira LG, Capp SM, You WB, Riffenburgh RH, Carstairs SH. Ondansetron compared with doxylamine and pyridoxine for treatment of nausea in pregnancy : a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2014;124(4):735–742.