User login

Richard Quinn is an award-winning journalist with 15 years’ experience. He has worked at the Asbury Park Press in New Jersey and The Virginian-Pilot in Norfolk, Va., and currently is managing editor for a leading commercial real estate publication. His freelance work has appeared in The Jewish State, The Hospitalist, The Rheumatologist, ACEP Now, and ENT Today. He lives in New Jersey with his wife and three cats.

Resident Fatigue and Distress Contribute to Perceived Medical Errors

Clinical question: Do resident fatigue and distress contribute to medical errors?

Background: In recent years, such measures as work-hour limitations have been implemented to decrease resident fatigue and, it is presumed, medical errors. However, few studies address the relationship between residents’ well-being and self-reported medical errors.

Study design: Prospective six-year longitudinal cohort study.

Setting: Single academic medical center.

Synopsis: The authors had 380 internal-medicine residents complete quarterly surveys to assess fatigue, quality of life, burnout, symptoms of depression, and frequency of perceived medical errors. In a univariate analysis, fatigue/sleepiness, burnout, depression, and overall quality of life measures correlated significantly with self-reported major medical errors. Fatigue/sleepiness and measures of distress additively increased the risk of self-reported errors. Increases in one or both domains were estimated to increase the risk of self-reported errors by as much as 15% to 28%.

The authors studied only self-reported medical errors. It is difficult to know whether these errors directly affected patient outcomes. Additionally, results of this single-site study might not be able to be generalized.

Bottom line: Fatigue and distress contribute to self-perceived medical errors among residents.

Citation: West CP, Tan AD, Habermann TM, Sloan JA, Shanafelt TD. Association of resident fatigue and distress with perceived medical errors. JAMA. 2009;302(12):1294-1300.

Clinical question: Do resident fatigue and distress contribute to medical errors?

Background: In recent years, such measures as work-hour limitations have been implemented to decrease resident fatigue and, it is presumed, medical errors. However, few studies address the relationship between residents’ well-being and self-reported medical errors.

Study design: Prospective six-year longitudinal cohort study.

Setting: Single academic medical center.

Synopsis: The authors had 380 internal-medicine residents complete quarterly surveys to assess fatigue, quality of life, burnout, symptoms of depression, and frequency of perceived medical errors. In a univariate analysis, fatigue/sleepiness, burnout, depression, and overall quality of life measures correlated significantly with self-reported major medical errors. Fatigue/sleepiness and measures of distress additively increased the risk of self-reported errors. Increases in one or both domains were estimated to increase the risk of self-reported errors by as much as 15% to 28%.

The authors studied only self-reported medical errors. It is difficult to know whether these errors directly affected patient outcomes. Additionally, results of this single-site study might not be able to be generalized.

Bottom line: Fatigue and distress contribute to self-perceived medical errors among residents.

Citation: West CP, Tan AD, Habermann TM, Sloan JA, Shanafelt TD. Association of resident fatigue and distress with perceived medical errors. JAMA. 2009;302(12):1294-1300.

Clinical question: Do resident fatigue and distress contribute to medical errors?

Background: In recent years, such measures as work-hour limitations have been implemented to decrease resident fatigue and, it is presumed, medical errors. However, few studies address the relationship between residents’ well-being and self-reported medical errors.

Study design: Prospective six-year longitudinal cohort study.

Setting: Single academic medical center.

Synopsis: The authors had 380 internal-medicine residents complete quarterly surveys to assess fatigue, quality of life, burnout, symptoms of depression, and frequency of perceived medical errors. In a univariate analysis, fatigue/sleepiness, burnout, depression, and overall quality of life measures correlated significantly with self-reported major medical errors. Fatigue/sleepiness and measures of distress additively increased the risk of self-reported errors. Increases in one or both domains were estimated to increase the risk of self-reported errors by as much as 15% to 28%.

The authors studied only self-reported medical errors. It is difficult to know whether these errors directly affected patient outcomes. Additionally, results of this single-site study might not be able to be generalized.

Bottom line: Fatigue and distress contribute to self-perceived medical errors among residents.

Citation: West CP, Tan AD, Habermann TM, Sloan JA, Shanafelt TD. Association of resident fatigue and distress with perceived medical errors. JAMA. 2009;302(12):1294-1300.

Dabigatran Is Not Inferior to Warfarin in Atrial Fibrillation

Clinical question: Is dabigatran, an oral thrombin inhibitor, an effective and safe alternative to warfarin in patients with atrial fibrillation?

Background: Warfarin reduces the risk of stroke among patients with atrial fibrillation (AF) but requires frequent laboratory monitoring. Dabigatran is an oral direct thrombin inhibitor given in fixed dosages without laboratory monitoring.

Study design: Randomized, multicenter, open-label, noninferiority trial.

Setting: 951 clinical centers in 44 countries.

Synopsis: More than 18,000 patients 65 and older with AF and at least one stroke risk factor were enrolled. The average CHADS2 score was 2.1. Patients were randomized to receive fixed doses of dabigatran (110 mg or 150 mg, twice daily) or warfarin adjusted to an INR of 2.0-3.0. The primary outcomes were a) stroke or systemic embolism and b) major hemorrhage. Median followup was two years.

The annual rates of stroke or systemic embolism for both doses of dabigatran were noninferior to warfarin (P<0.001); higher-dose dabigatran was statistically superior to warfarin (relative risk (RR)=0.66, P<0.001). The annual rate of major hemorrhage was lowest in the lower-dose dabigatran group (RR=0.80, P=0.003 compared with warfarin); the higher-dose dabigatran and warfarin groups had equivalent rates of major bleeding. No increased risk of liver function abnormalities was noted.

Bottom line: Dabigatran appears to be an effective and safe alternative to warfarin in AF patients. If the drug were to be FDA-approved, appropriate patient selection and cost will need to be established.

Citation: Connolly SJ, Ezekowitz MD, Yusuf S, et al. Dabigatran versus warfarin in patients with atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med. 2009;361(12):1139-1151.

Clinical question: Is dabigatran, an oral thrombin inhibitor, an effective and safe alternative to warfarin in patients with atrial fibrillation?

Background: Warfarin reduces the risk of stroke among patients with atrial fibrillation (AF) but requires frequent laboratory monitoring. Dabigatran is an oral direct thrombin inhibitor given in fixed dosages without laboratory monitoring.

Study design: Randomized, multicenter, open-label, noninferiority trial.

Setting: 951 clinical centers in 44 countries.

Synopsis: More than 18,000 patients 65 and older with AF and at least one stroke risk factor were enrolled. The average CHADS2 score was 2.1. Patients were randomized to receive fixed doses of dabigatran (110 mg or 150 mg, twice daily) or warfarin adjusted to an INR of 2.0-3.0. The primary outcomes were a) stroke or systemic embolism and b) major hemorrhage. Median followup was two years.

The annual rates of stroke or systemic embolism for both doses of dabigatran were noninferior to warfarin (P<0.001); higher-dose dabigatran was statistically superior to warfarin (relative risk (RR)=0.66, P<0.001). The annual rate of major hemorrhage was lowest in the lower-dose dabigatran group (RR=0.80, P=0.003 compared with warfarin); the higher-dose dabigatran and warfarin groups had equivalent rates of major bleeding. No increased risk of liver function abnormalities was noted.

Bottom line: Dabigatran appears to be an effective and safe alternative to warfarin in AF patients. If the drug were to be FDA-approved, appropriate patient selection and cost will need to be established.

Citation: Connolly SJ, Ezekowitz MD, Yusuf S, et al. Dabigatran versus warfarin in patients with atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med. 2009;361(12):1139-1151.

Clinical question: Is dabigatran, an oral thrombin inhibitor, an effective and safe alternative to warfarin in patients with atrial fibrillation?

Background: Warfarin reduces the risk of stroke among patients with atrial fibrillation (AF) but requires frequent laboratory monitoring. Dabigatran is an oral direct thrombin inhibitor given in fixed dosages without laboratory monitoring.

Study design: Randomized, multicenter, open-label, noninferiority trial.

Setting: 951 clinical centers in 44 countries.

Synopsis: More than 18,000 patients 65 and older with AF and at least one stroke risk factor were enrolled. The average CHADS2 score was 2.1. Patients were randomized to receive fixed doses of dabigatran (110 mg or 150 mg, twice daily) or warfarin adjusted to an INR of 2.0-3.0. The primary outcomes were a) stroke or systemic embolism and b) major hemorrhage. Median followup was two years.

The annual rates of stroke or systemic embolism for both doses of dabigatran were noninferior to warfarin (P<0.001); higher-dose dabigatran was statistically superior to warfarin (relative risk (RR)=0.66, P<0.001). The annual rate of major hemorrhage was lowest in the lower-dose dabigatran group (RR=0.80, P=0.003 compared with warfarin); the higher-dose dabigatran and warfarin groups had equivalent rates of major bleeding. No increased risk of liver function abnormalities was noted.

Bottom line: Dabigatran appears to be an effective and safe alternative to warfarin in AF patients. If the drug were to be FDA-approved, appropriate patient selection and cost will need to be established.

Citation: Connolly SJ, Ezekowitz MD, Yusuf S, et al. Dabigatran versus warfarin in patients with atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med. 2009;361(12):1139-1151.

Cardiac Resynchronization Therapy with Implantable Cardioverter Defibrillator Placement Decreases Heart Failure

Clinical question: Does cardiac resynchronization therapy (CRT) with biventricular pacing decrease cardiac events in patients with reduced ejection fraction (EF) and wide QRS complex but only mild cardiac symptoms?

Background: In patients with severely reduced EF, implantable cardioverter defibrillators (ICDs) have been shown to improve survival. Meanwhile, CRT decreases heart-failure-related hospitalizations for patients with advanced heart-failure symptoms, EF less than 35%, and intraventricular conduction delay. It is not as clear whether patients with less-severe symptoms benefit from CRT.

Study design: Randomized, controlled trial.

Setting: 110 medical centers in the U.S., Canada, and Europe.

Synopsis: This Multicenter Automatic Defibrillator Implantation Trial with Cardiac Resynchronization Therapy (MADIT-CRT) study randomly assigned 1,820 adults with EF less than 30%, New York Health Association Class I or II congestive heart failure, and in sinus rhythm with QRS greater than 130 msec to receive ICD with CRT or ICD alone. The primary endpoint was all-cause mortality or nonfatal heart-failure events. Average followup was 2.4 years.

A 34% reduction in the primary endpoint was found in the ICD-CRT group when compared with the ICD-only group, primarily due to a 41% reduction in heart-failure events. In a subgroup analysis, women and patients with QRS greater than 150 msec experienced particular benefit. Echocardiography one year after device implantation demonstrated significant reductions in left ventricular end-systolic and end-diastolic volume, and a significant increase in EF with ICD-CRT versus ICD-only (P<0.001).

Bottom line: Compared with ICD alone, CRT in combination with ICD prevented heart-failure events in relatively asymptomatic heart-failure patients with low EF and prolonged QRS.

Citation: Moss AJ, Hall WJ, Cannom DS, et al. Cardiac-resynchronization therapy for the prevention of heart-failure events. N Engl J Med. 2009;361(14):1329-1338.

Clinical question: Does cardiac resynchronization therapy (CRT) with biventricular pacing decrease cardiac events in patients with reduced ejection fraction (EF) and wide QRS complex but only mild cardiac symptoms?

Background: In patients with severely reduced EF, implantable cardioverter defibrillators (ICDs) have been shown to improve survival. Meanwhile, CRT decreases heart-failure-related hospitalizations for patients with advanced heart-failure symptoms, EF less than 35%, and intraventricular conduction delay. It is not as clear whether patients with less-severe symptoms benefit from CRT.

Study design: Randomized, controlled trial.

Setting: 110 medical centers in the U.S., Canada, and Europe.

Synopsis: This Multicenter Automatic Defibrillator Implantation Trial with Cardiac Resynchronization Therapy (MADIT-CRT) study randomly assigned 1,820 adults with EF less than 30%, New York Health Association Class I or II congestive heart failure, and in sinus rhythm with QRS greater than 130 msec to receive ICD with CRT or ICD alone. The primary endpoint was all-cause mortality or nonfatal heart-failure events. Average followup was 2.4 years.

A 34% reduction in the primary endpoint was found in the ICD-CRT group when compared with the ICD-only group, primarily due to a 41% reduction in heart-failure events. In a subgroup analysis, women and patients with QRS greater than 150 msec experienced particular benefit. Echocardiography one year after device implantation demonstrated significant reductions in left ventricular end-systolic and end-diastolic volume, and a significant increase in EF with ICD-CRT versus ICD-only (P<0.001).

Bottom line: Compared with ICD alone, CRT in combination with ICD prevented heart-failure events in relatively asymptomatic heart-failure patients with low EF and prolonged QRS.

Citation: Moss AJ, Hall WJ, Cannom DS, et al. Cardiac-resynchronization therapy for the prevention of heart-failure events. N Engl J Med. 2009;361(14):1329-1338.

Clinical question: Does cardiac resynchronization therapy (CRT) with biventricular pacing decrease cardiac events in patients with reduced ejection fraction (EF) and wide QRS complex but only mild cardiac symptoms?

Background: In patients with severely reduced EF, implantable cardioverter defibrillators (ICDs) have been shown to improve survival. Meanwhile, CRT decreases heart-failure-related hospitalizations for patients with advanced heart-failure symptoms, EF less than 35%, and intraventricular conduction delay. It is not as clear whether patients with less-severe symptoms benefit from CRT.

Study design: Randomized, controlled trial.

Setting: 110 medical centers in the U.S., Canada, and Europe.

Synopsis: This Multicenter Automatic Defibrillator Implantation Trial with Cardiac Resynchronization Therapy (MADIT-CRT) study randomly assigned 1,820 adults with EF less than 30%, New York Health Association Class I or II congestive heart failure, and in sinus rhythm with QRS greater than 130 msec to receive ICD with CRT or ICD alone. The primary endpoint was all-cause mortality or nonfatal heart-failure events. Average followup was 2.4 years.

A 34% reduction in the primary endpoint was found in the ICD-CRT group when compared with the ICD-only group, primarily due to a 41% reduction in heart-failure events. In a subgroup analysis, women and patients with QRS greater than 150 msec experienced particular benefit. Echocardiography one year after device implantation demonstrated significant reductions in left ventricular end-systolic and end-diastolic volume, and a significant increase in EF with ICD-CRT versus ICD-only (P<0.001).

Bottom line: Compared with ICD alone, CRT in combination with ICD prevented heart-failure events in relatively asymptomatic heart-failure patients with low EF and prolonged QRS.

Citation: Moss AJ, Hall WJ, Cannom DS, et al. Cardiac-resynchronization therapy for the prevention of heart-failure events. N Engl J Med. 2009;361(14):1329-1338.

Fluvastatin Improves Postoperative Cardiac Outcomes in Patients Undergoing Vascular Surgery

Clinical question: Does perioperative fluvastatin decrease adverse cardiac events after vascular surgery?

Background: Patients with atherosclerotic vascular disease who undergo vascular surgery are at high risk for postoperative cardiac events. Studies in nonsurgical populations have shown the beneficial effects of statin therapy on cardiac outcomes. However, no placebo-controlled trials have addressed the effect of statins on postoperative cardiac outcomes.

Study design: Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial.

Setting: Single large academic medical center in the Netherlands.

Synopsis: The study looked at 497 statin-naïve patients 40 years or older undergoing non-cardiac vascular surgery. The patients were randomized to 80 mg of extended-release fluvastatin versus placebo; all patients received a beta-blocker. Therapy began preoperatively (median of 37 days) and continued for at least 30 days after surgery. Outcomes were assessed at 30 days post-surgery.

Postoperative myocardial infarction (MI) was significantly less common in the fluvastatin group than with placebo (10.8% vs. 19%, hazard ratio (HR) 0.55, P=0.01). In addition, the treatment group had a lower frequency of death from cardiovascular causes (4.8% vs. 10.1%, HR 0.47, P=0.03). Statin therapy was not associated with an increased rate of adverse events.

Notably, all of the patients enrolled in this study were high-risk patients undergoing high-risk (vascular) surgery. Patients already on statins were excluded.

Further studies are needed to determine whether the findings can be extrapolated to other populations, including nonvascular surgery patients.

Bottom line: Perioperative statin therapy resulted in a significant decrease in postoperative MI and death within 30 days of vascular surgery.

Citation: Schouten O, Boersma E, Hoeks SE, et al. Fluvastatin and perioperative events in patients undergoing vascular surgery. N Engl J Med. 2009;361(10):980-989.

Clinical question: Does perioperative fluvastatin decrease adverse cardiac events after vascular surgery?

Background: Patients with atherosclerotic vascular disease who undergo vascular surgery are at high risk for postoperative cardiac events. Studies in nonsurgical populations have shown the beneficial effects of statin therapy on cardiac outcomes. However, no placebo-controlled trials have addressed the effect of statins on postoperative cardiac outcomes.

Study design: Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial.

Setting: Single large academic medical center in the Netherlands.

Synopsis: The study looked at 497 statin-naïve patients 40 years or older undergoing non-cardiac vascular surgery. The patients were randomized to 80 mg of extended-release fluvastatin versus placebo; all patients received a beta-blocker. Therapy began preoperatively (median of 37 days) and continued for at least 30 days after surgery. Outcomes were assessed at 30 days post-surgery.

Postoperative myocardial infarction (MI) was significantly less common in the fluvastatin group than with placebo (10.8% vs. 19%, hazard ratio (HR) 0.55, P=0.01). In addition, the treatment group had a lower frequency of death from cardiovascular causes (4.8% vs. 10.1%, HR 0.47, P=0.03). Statin therapy was not associated with an increased rate of adverse events.

Notably, all of the patients enrolled in this study were high-risk patients undergoing high-risk (vascular) surgery. Patients already on statins were excluded.

Further studies are needed to determine whether the findings can be extrapolated to other populations, including nonvascular surgery patients.

Bottom line: Perioperative statin therapy resulted in a significant decrease in postoperative MI and death within 30 days of vascular surgery.

Citation: Schouten O, Boersma E, Hoeks SE, et al. Fluvastatin and perioperative events in patients undergoing vascular surgery. N Engl J Med. 2009;361(10):980-989.

Clinical question: Does perioperative fluvastatin decrease adverse cardiac events after vascular surgery?

Background: Patients with atherosclerotic vascular disease who undergo vascular surgery are at high risk for postoperative cardiac events. Studies in nonsurgical populations have shown the beneficial effects of statin therapy on cardiac outcomes. However, no placebo-controlled trials have addressed the effect of statins on postoperative cardiac outcomes.

Study design: Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial.

Setting: Single large academic medical center in the Netherlands.

Synopsis: The study looked at 497 statin-naïve patients 40 years or older undergoing non-cardiac vascular surgery. The patients were randomized to 80 mg of extended-release fluvastatin versus placebo; all patients received a beta-blocker. Therapy began preoperatively (median of 37 days) and continued for at least 30 days after surgery. Outcomes were assessed at 30 days post-surgery.

Postoperative myocardial infarction (MI) was significantly less common in the fluvastatin group than with placebo (10.8% vs. 19%, hazard ratio (HR) 0.55, P=0.01). In addition, the treatment group had a lower frequency of death from cardiovascular causes (4.8% vs. 10.1%, HR 0.47, P=0.03). Statin therapy was not associated with an increased rate of adverse events.

Notably, all of the patients enrolled in this study were high-risk patients undergoing high-risk (vascular) surgery. Patients already on statins were excluded.

Further studies are needed to determine whether the findings can be extrapolated to other populations, including nonvascular surgery patients.

Bottom line: Perioperative statin therapy resulted in a significant decrease in postoperative MI and death within 30 days of vascular surgery.

Citation: Schouten O, Boersma E, Hoeks SE, et al. Fluvastatin and perioperative events in patients undergoing vascular surgery. N Engl J Med. 2009;361(10):980-989.

Hospitalists Less-Likely Targets of Malpractice Claims Than Other Physicians

In the article "Liability Impact of the Hospitalist Model of Care," Adam Schaffer, MD, a hospitalist at Brigham and Women's Hospital in Boston, writes that hospitalists average 0.52 malpractice claims per 100 physician coverage years (PCYs), while non-hospitalist internal medicine physicians have a rate of 1.91 claims per 100 PCYs. By comparison, ED physicians average 3.5 claims per 100 PYCs, general surgeons average 4.7 claims, and OB/GYNs average 5.56 claims (P<0.001 for all comparisons).

"I was fairly surprised because the magnitude of the decreased risk…was fairly significant and statistically significant," Dr. Schaffer says. He notes that having relatively short interactions with patients and the difficulties of care transitions would appear to make it difficult for hospitalists to establish the type of close relationships with patients that can help prevent malpractice claims. However, hospitalists have overcome that hurdle.

An editorial that accompanies the JHM study contends that hospitalists develop and hone skills "which allow them to quickly establish rapport with patients and families." The editorial was penned by hospitalist Kevin O'Leary, MD, MS, SFHM, of Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine in Chicago, and JHM Editor-in-Chief Andrew Auerbach, MD, MPH, SFHM, of the University of California, San Francisco.

"Even though you may have a relatively brief relationship with the patient," Dr. Schaffer adds, "the fact that you're in the hospital, able to see them, meet with them, answer their questions multiple times a day if need be, that may actually help establish a strong and robust physician-patient relationship."

Visit SHM's blog, "The Hospital Leader," for an exploration of malpractice suits and a Q&A with study author Adam Schaffer.

In the article "Liability Impact of the Hospitalist Model of Care," Adam Schaffer, MD, a hospitalist at Brigham and Women's Hospital in Boston, writes that hospitalists average 0.52 malpractice claims per 100 physician coverage years (PCYs), while non-hospitalist internal medicine physicians have a rate of 1.91 claims per 100 PCYs. By comparison, ED physicians average 3.5 claims per 100 PYCs, general surgeons average 4.7 claims, and OB/GYNs average 5.56 claims (P<0.001 for all comparisons).

"I was fairly surprised because the magnitude of the decreased risk…was fairly significant and statistically significant," Dr. Schaffer says. He notes that having relatively short interactions with patients and the difficulties of care transitions would appear to make it difficult for hospitalists to establish the type of close relationships with patients that can help prevent malpractice claims. However, hospitalists have overcome that hurdle.

An editorial that accompanies the JHM study contends that hospitalists develop and hone skills "which allow them to quickly establish rapport with patients and families." The editorial was penned by hospitalist Kevin O'Leary, MD, MS, SFHM, of Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine in Chicago, and JHM Editor-in-Chief Andrew Auerbach, MD, MPH, SFHM, of the University of California, San Francisco.

"Even though you may have a relatively brief relationship with the patient," Dr. Schaffer adds, "the fact that you're in the hospital, able to see them, meet with them, answer their questions multiple times a day if need be, that may actually help establish a strong and robust physician-patient relationship."

Visit SHM's blog, "The Hospital Leader," for an exploration of malpractice suits and a Q&A with study author Adam Schaffer.

In the article "Liability Impact of the Hospitalist Model of Care," Adam Schaffer, MD, a hospitalist at Brigham and Women's Hospital in Boston, writes that hospitalists average 0.52 malpractice claims per 100 physician coverage years (PCYs), while non-hospitalist internal medicine physicians have a rate of 1.91 claims per 100 PCYs. By comparison, ED physicians average 3.5 claims per 100 PYCs, general surgeons average 4.7 claims, and OB/GYNs average 5.56 claims (P<0.001 for all comparisons).

"I was fairly surprised because the magnitude of the decreased risk…was fairly significant and statistically significant," Dr. Schaffer says. He notes that having relatively short interactions with patients and the difficulties of care transitions would appear to make it difficult for hospitalists to establish the type of close relationships with patients that can help prevent malpractice claims. However, hospitalists have overcome that hurdle.

An editorial that accompanies the JHM study contends that hospitalists develop and hone skills "which allow them to quickly establish rapport with patients and families." The editorial was penned by hospitalist Kevin O'Leary, MD, MS, SFHM, of Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine in Chicago, and JHM Editor-in-Chief Andrew Auerbach, MD, MPH, SFHM, of the University of California, San Francisco.

"Even though you may have a relatively brief relationship with the patient," Dr. Schaffer adds, "the fact that you're in the hospital, able to see them, meet with them, answer their questions multiple times a day if need be, that may actually help establish a strong and robust physician-patient relationship."

Visit SHM's blog, "The Hospital Leader," for an exploration of malpractice suits and a Q&A with study author Adam Schaffer.

Four Things HMGs Should Do To Prepare for Ebola

Hospitalist Monal Shah, MD, FACP, physician advisor for Parkland Health & Hospital System in Dallas, says that HM groups looking to anticipate potential cases of Ebola in their region should:

- Make sure doctors know contact information for infection-prevention staffers and their local health department;

- Double-check that physicians know how to quickly get in contact with infectious-disease (ID) specialists;

- Be aware of isolation procedures that will be necessary for this type of patient, including the use of standard, contact, and droplet precautions as well as others recommended by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; and

- Be diligent about asking patients about their recent travels when taking patient histories.

"For this particular disease, the travel is the big kicker," says Dr. Shah, a member of Team Hospitalist. "The other symptoms are just so nonspecific. It's vomiting, diarrhea, headaches, weakness...if we tried to admit everyone who had those types of symptoms, it wouldn't make sense."

Dr. Shah says that although he wasn't involved, emergency-preparedness discussions at his institution about dealing with potential Ebola patients started a couple of months ago as spread of the disease in Africa became global news. But although the disease has been making headlines, HM groups are unlikely to make major changes to their care delivery processes, as even just changing the primary lead from a hospitalist to an ID physician could have unintended consequences, he adds.

"Who would cover at night?" Dr. Shah asks. "Who would be the first call at night? Would our nurses know that flow?

"There are a lot of potential downstream things that would need to be changed."

Hospitalist Monal Shah, MD, FACP, physician advisor for Parkland Health & Hospital System in Dallas, says that HM groups looking to anticipate potential cases of Ebola in their region should:

- Make sure doctors know contact information for infection-prevention staffers and their local health department;

- Double-check that physicians know how to quickly get in contact with infectious-disease (ID) specialists;

- Be aware of isolation procedures that will be necessary for this type of patient, including the use of standard, contact, and droplet precautions as well as others recommended by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; and

- Be diligent about asking patients about their recent travels when taking patient histories.

"For this particular disease, the travel is the big kicker," says Dr. Shah, a member of Team Hospitalist. "The other symptoms are just so nonspecific. It's vomiting, diarrhea, headaches, weakness...if we tried to admit everyone who had those types of symptoms, it wouldn't make sense."

Dr. Shah says that although he wasn't involved, emergency-preparedness discussions at his institution about dealing with potential Ebola patients started a couple of months ago as spread of the disease in Africa became global news. But although the disease has been making headlines, HM groups are unlikely to make major changes to their care delivery processes, as even just changing the primary lead from a hospitalist to an ID physician could have unintended consequences, he adds.

"Who would cover at night?" Dr. Shah asks. "Who would be the first call at night? Would our nurses know that flow?

"There are a lot of potential downstream things that would need to be changed."

Hospitalist Monal Shah, MD, FACP, physician advisor for Parkland Health & Hospital System in Dallas, says that HM groups looking to anticipate potential cases of Ebola in their region should:

- Make sure doctors know contact information for infection-prevention staffers and their local health department;

- Double-check that physicians know how to quickly get in contact with infectious-disease (ID) specialists;

- Be aware of isolation procedures that will be necessary for this type of patient, including the use of standard, contact, and droplet precautions as well as others recommended by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; and

- Be diligent about asking patients about their recent travels when taking patient histories.

"For this particular disease, the travel is the big kicker," says Dr. Shah, a member of Team Hospitalist. "The other symptoms are just so nonspecific. It's vomiting, diarrhea, headaches, weakness...if we tried to admit everyone who had those types of symptoms, it wouldn't make sense."

Dr. Shah says that although he wasn't involved, emergency-preparedness discussions at his institution about dealing with potential Ebola patients started a couple of months ago as spread of the disease in Africa became global news. But although the disease has been making headlines, HM groups are unlikely to make major changes to their care delivery processes, as even just changing the primary lead from a hospitalist to an ID physician could have unintended consequences, he adds.

"Who would cover at night?" Dr. Shah asks. "Who would be the first call at night? Would our nurses know that flow?

"There are a lot of potential downstream things that would need to be changed."

Hospitalists May Share Smaller Slice of Healthcare Spending Pie

Committee member Bradley Flansbaum, DO, MPH, SFHM, says he expects the amount of funding going to hospitalists to decrease in the coming years as healthcare reform focuses on keeping patients out of the hospital.

"The slice that's going to be dedicated to inpatient medicine in hospitals is going to shrink," says Dr. Flansbaum, a hospitalist at Lenox Hill Hospital in New York City. "From a hospitalist standpoint, I don't think it's kick back, flip open the beer lid, and turn the game on. Things are really going to change."

A report in this month's Health Affairs shows that spending growth in 2013 fell to 3.6%, down from 7.2% annually on average between 1990 and 2008. The decreased rate is attributed to a "sluggish economic recovery, the effects of sequestration, and continued increases in private health insurance cost-sharing requirements," according to the report.

However, the combination of money being pumped into healthcare reform and a growing economy is projected to push up spending by 5.6% this year and 6% annually each year from 2015 to 2023, according to the report. How much of that money will flow into HM depends, in part, on how well the specialty improves patient care and hospital bottom lines, Dr. Flansbaum says. "And teasing out that effect is tough," he says. "Mainly, is it that we're ordering less tests or are the prices going down or neither, and [are] other forces contributing to efficiency gains? Those are very different variables."

Committee member Bradley Flansbaum, DO, MPH, SFHM, says he expects the amount of funding going to hospitalists to decrease in the coming years as healthcare reform focuses on keeping patients out of the hospital.

"The slice that's going to be dedicated to inpatient medicine in hospitals is going to shrink," says Dr. Flansbaum, a hospitalist at Lenox Hill Hospital in New York City. "From a hospitalist standpoint, I don't think it's kick back, flip open the beer lid, and turn the game on. Things are really going to change."

A report in this month's Health Affairs shows that spending growth in 2013 fell to 3.6%, down from 7.2% annually on average between 1990 and 2008. The decreased rate is attributed to a "sluggish economic recovery, the effects of sequestration, and continued increases in private health insurance cost-sharing requirements," according to the report.

However, the combination of money being pumped into healthcare reform and a growing economy is projected to push up spending by 5.6% this year and 6% annually each year from 2015 to 2023, according to the report. How much of that money will flow into HM depends, in part, on how well the specialty improves patient care and hospital bottom lines, Dr. Flansbaum says. "And teasing out that effect is tough," he says. "Mainly, is it that we're ordering less tests or are the prices going down or neither, and [are] other forces contributing to efficiency gains? Those are very different variables."

Committee member Bradley Flansbaum, DO, MPH, SFHM, says he expects the amount of funding going to hospitalists to decrease in the coming years as healthcare reform focuses on keeping patients out of the hospital.

"The slice that's going to be dedicated to inpatient medicine in hospitals is going to shrink," says Dr. Flansbaum, a hospitalist at Lenox Hill Hospital in New York City. "From a hospitalist standpoint, I don't think it's kick back, flip open the beer lid, and turn the game on. Things are really going to change."

A report in this month's Health Affairs shows that spending growth in 2013 fell to 3.6%, down from 7.2% annually on average between 1990 and 2008. The decreased rate is attributed to a "sluggish economic recovery, the effects of sequestration, and continued increases in private health insurance cost-sharing requirements," according to the report.

However, the combination of money being pumped into healthcare reform and a growing economy is projected to push up spending by 5.6% this year and 6% annually each year from 2015 to 2023, according to the report. How much of that money will flow into HM depends, in part, on how well the specialty improves patient care and hospital bottom lines, Dr. Flansbaum says. "And teasing out that effect is tough," he says. "Mainly, is it that we're ordering less tests or are the prices going down or neither, and [are] other forces contributing to efficiency gains? Those are very different variables."

Hospital Stipends, Employment Models for Hospitalists Trends to Watch

One of the toughest jobs of group management is teasing out the trends that will define HM in the future. In the past few years, hospitalist leaders have tried to forecast whether the growth in compensation would slow or even recede. Instead, median compensation nationwide climbed 17.7% between 2010 and 2014, telling

Dr. Landis that a specialty barely 20 years old still has room to grow.

“There’s a lot at stake here,” he says. “Our patients’ lives are at stake. A lot of our country’s resources are going into healthcare, and the hospital is a very expensive place to receive care, so we want to be delivering the best value.

“We’ve got to do a better job, The information [in the report] is there to help hospital medicine groups and hospitalists.”

IPC’s Taylor adds that trying to understand trends begins with noticing shifts before they become industry standards. He’s tracking two of those right now.

“We’re now seeing hospital stipends starting to be examined by the hospitals,” he says, noting that healthcare executives are asking if this is “a rational amount of money to be paying to support a program?

“We’re [also] starting to see a reversal in the trend of hospitals employing their own hospitalists, which gained quite a bit of steam about five years ago, but it seemed to start running out of steam. Now, from what we are seeing in the marketplace, it appears to be tipping back the other way, particularly with hospitals that have done the math, and they’re beginning to outsource.”

Whether those early warning signs become full-blown trends or not, Taylor says the best management approach is to measure as much information as possible moving forward. Having the SOHM’s baseline every other year is another piece of that information pie.

“It’s interesting data, but I think it’s going to be more interesting to me to see how that data looks three to four years from now, [to understand] if the trends we see or we believe we see beginning, continue,” he adds. “It will be interesting to see the impact of those two forces on the data.”—RQ

One of the toughest jobs of group management is teasing out the trends that will define HM in the future. In the past few years, hospitalist leaders have tried to forecast whether the growth in compensation would slow or even recede. Instead, median compensation nationwide climbed 17.7% between 2010 and 2014, telling

Dr. Landis that a specialty barely 20 years old still has room to grow.

“There’s a lot at stake here,” he says. “Our patients’ lives are at stake. A lot of our country’s resources are going into healthcare, and the hospital is a very expensive place to receive care, so we want to be delivering the best value.

“We’ve got to do a better job, The information [in the report] is there to help hospital medicine groups and hospitalists.”

IPC’s Taylor adds that trying to understand trends begins with noticing shifts before they become industry standards. He’s tracking two of those right now.

“We’re now seeing hospital stipends starting to be examined by the hospitals,” he says, noting that healthcare executives are asking if this is “a rational amount of money to be paying to support a program?

“We’re [also] starting to see a reversal in the trend of hospitals employing their own hospitalists, which gained quite a bit of steam about five years ago, but it seemed to start running out of steam. Now, from what we are seeing in the marketplace, it appears to be tipping back the other way, particularly with hospitals that have done the math, and they’re beginning to outsource.”

Whether those early warning signs become full-blown trends or not, Taylor says the best management approach is to measure as much information as possible moving forward. Having the SOHM’s baseline every other year is another piece of that information pie.

“It’s interesting data, but I think it’s going to be more interesting to me to see how that data looks three to four years from now, [to understand] if the trends we see or we believe we see beginning, continue,” he adds. “It will be interesting to see the impact of those two forces on the data.”—RQ

One of the toughest jobs of group management is teasing out the trends that will define HM in the future. In the past few years, hospitalist leaders have tried to forecast whether the growth in compensation would slow or even recede. Instead, median compensation nationwide climbed 17.7% between 2010 and 2014, telling

Dr. Landis that a specialty barely 20 years old still has room to grow.

“There’s a lot at stake here,” he says. “Our patients’ lives are at stake. A lot of our country’s resources are going into healthcare, and the hospital is a very expensive place to receive care, so we want to be delivering the best value.

“We’ve got to do a better job, The information [in the report] is there to help hospital medicine groups and hospitalists.”

IPC’s Taylor adds that trying to understand trends begins with noticing shifts before they become industry standards. He’s tracking two of those right now.

“We’re now seeing hospital stipends starting to be examined by the hospitals,” he says, noting that healthcare executives are asking if this is “a rational amount of money to be paying to support a program?

“We’re [also] starting to see a reversal in the trend of hospitals employing their own hospitalists, which gained quite a bit of steam about five years ago, but it seemed to start running out of steam. Now, from what we are seeing in the marketplace, it appears to be tipping back the other way, particularly with hospitals that have done the math, and they’re beginning to outsource.”

Whether those early warning signs become full-blown trends or not, Taylor says the best management approach is to measure as much information as possible moving forward. Having the SOHM’s baseline every other year is another piece of that information pie.

“It’s interesting data, but I think it’s going to be more interesting to me to see how that data looks three to four years from now, [to understand] if the trends we see or we believe we see beginning, continue,” he adds. “It will be interesting to see the impact of those two forces on the data.”—RQ

New State of Hospital Medicine Report Offers Insight to Trends in Hospitalist Compensation, Productivity

The highlight of SHM’s biennial State of Hospital Medicine (SOHM) report is how much hospitalists earn. So it’s to be expected that rank-and-file practitioners and group leaders who read this year’s edition will first notice that median compensation for adult hospitalists rose 8% to $252,996 in 2013, according to data from the Medical Group Management Association (MGMA). The compensation data from MGMA is wrapped into the SOHM 2014 report this year.

But to stop there would be a wasted opportunity, says William “Tex” Landis, MD, FHM, medical director of Wellspan Hospitalists in York, Pa., and a member and former chair of SHM’s Practice Analysis Committee. Along with compensation, the report (available at www.hospitalmedicine.org/survey) delves into scheduling, productivity, staffing, how compensation is broken down, practice models, and dozens of other topics that hospital medicine group (HMG) leaders will find useful.

“Scope of services is a big one,” Dr. Landis adds. “What other things are hospital medicine groups around the country being held responsible for? Are we morphing into universal admitters? How involved in palliative care are we? What about transitions of care? How many hospital medicine groups are becoming involved in managing nursing home patients? What’s the relationship with surgical co-management? How much ICU work are we doing?”

Dr. Landis’ laundry list of unanswered questions might seem daunting, but that’s the point of the research SHM has been collecting and reporting for years. The society surveyed 499 groups, representing some 6,300 providers, to give the specialty’s most detailed list of most popular, if not best, practices.

“It has the usual limitations of any survey; however, it is the very best survey, quantity and quality, of hospital medicine groups,” Dr. Landis says. “And so it becomes the best source of information to make important decisions about resourcing and operating hospital medicine groups.”

Earnings Up

And, like it or not, compensation for providers typically is a HMG’s largest budget line. In that regard, the specialty appears to be doing well. Median compensation for adult hospitalists rose to a record high last year, according to the MGMA Physician Compensation and Production Survey: 2014 Report Based on 2013 Data. Half of respondents work in practices owned by hospitals/integrated delivery systems, down from 56% in SOHM 2012.

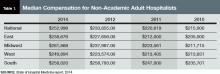

Although hospitalists in the South region continue to earn the most (median compensation $258,020, essentially static with the $258,793 figure reported in 2012), the region was the only one to report a decrease (see Table 1 for historical data). The largest percentage jump (11.8%) was for hospitalists in the West region ($249,894). Hospitalists in the Midwest saw a 10% increase ($261,868), while those in the East had both the smallest increase (4.8%) and the lowest median compensation ($238,676).

—R. Jeffrey Taylor, president and COO, IPC The Hospitalist Co., North Hollywood, Calif.

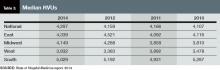

Part of the compensation increase is tied to upward pressure on productivity. Nationwide, median relative value units (RVUs) rose 3.3%, to 4,297 from 4,159. Median collection-to-work RVUs ticked up 6.8%, to 51.5 from 48.21 (see Table 2 for regional breakdowns). Production (10.5%) and performance (6.6%) are also slightly larger portions of mean compensation than they were in 2012, a figure many expect to increase further in future reports. The report also noted that academic/university hospitalists receive more in base pay, while hospitalists in private practice receive less.

Compensation and work volume will be intrinsically tied in the coming years, says R. Jeffrey Taylor, president and chief operating officer of IPC The Hospitalist Co., based in North Hollywood, Calif. And if pay outpaces productivity, “then it’s a bit concerning for the system at large,” he says.

“Particularly for whoever is subsidizing that shortfall, whether it’s a hospital employing doctors or an outsourced group employing the doctors but requiring a large subsidy from the hospital because the doctors are not seeing enough patient flow to pay their salary and benefits,” Taylor says.

More than 89% of HMGs rely on their host hospitals for financial support, according to the new data. The median support is $156,063 per full-time employee (FTE), which would total $1 million at just over seven FTEs. As healthcare reform progresses and hospitals’ budgets are increasingly burdened, Taylor says that pressure for hospitalists to generate enough revenue to cover their own salaries will grow. That sets up a likely showdown between hospitalists and their institutions; SOHM 2014 reported that just 6% of HMGs received enough income from professional fee revenue to cover expenses.

SOURCE: State of Hospital Medicine report, 2014

SOURCE: State of Hospital Medicine report, 2014

“Some productivity element in compensation plans, we believe, and I believe personally, is important,” Taylor says, later adding: “We already have a physician shortage and a shortage of people to see all these patients. It’s exacerbated by two things: lack of productivity and shift-model scheduling.”

To wit, IPC pays lower base salaries but provides bonuses tied to productivity and quality metrics. The average IPC hospitalist, Taylor says, earned more than $290,000 last year, nearly 15% above the median figure in the SOHM report. Between 30%-40% of that compensation, however, was earned via bonus tied to both “productivity and clinical achievement.”

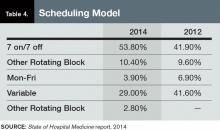

Taylor, an outspoken advocate for moving away from the seven-on/seven-off scheduling model popular throughout hospital medicine, ties some of his doctors’ higher compensation to his firm’s preference for avoiding that schedule. But he’s not surprised the new report shows that 53.8% of responding HMGs use the model, up from 41.9% in 2012.

“It will be interesting to see what the data shows over the next three or four years,” he says, “if stipends, as we believe we are seeing, come under pressure and hospitals are doing more outsourcing.”

SOURCE: State of Hospital Medicine report, 2014

The PCP Link

Industry leaders use the information in the biennial reports to gauge where the specialty stands in the overall healthcare spectrum. Dea Robinson, MA, FACMPE, CPC, director of consulting for MGMA Health Care Consulting Group, says that the growth of hospital medicine (HM) compensation is tied to that of primary care physicians (PCPs).

“I don’t think we can look at hospitalists without looking at primary care, because it’s really an extension of primary care,” says Robinson, a member of SHM’s Practice Management Committee. “As primary care compensation increases, hospitalists’ compensation might increase as well. And with the focus on patient-centered medical homes, which is basically primary care centered, that might very well be part of the driver in the future of seeing hospitalists grow.”

While facing a well-known physician shortage, primary care’s compensation growth also lags behind HM. For example, median compensation for hospitalists rose 8%; it increased 5.5% for PCPs.

“When it comes to growth of the two individual industries, I think they are connected in some way,” she adds. “But in terms of the compensation, now we’re starting to see different codes that hospitalists are able to use but that primary care used to use exclusively. So, you really see more of an extension and a collaboration between true primary care and hospitalists.”

Bryan Weiss, MBA, FHM, managing director of the consulting services practice at Irving, Texas-based MedSynergies, agrees that hospitalists and PCPs are connected. He believes the higher compensation figures are a sign of how young HM is as a specialty. He fears compensation “is probably growing too fast.”

“This takes me back to the 1990s, with the private [physician practice management]-type model, where it just grew so fast that the bottom fell out,” says Weiss, a member of Team Hospitalist. “Not that I think the bottom is going to fall out of hospital medicine, but a lot of this is reminiscent of that, and I think there’s going to be a ceiling, or at least a slowing down.”

—Stuart Guterman, vice president, Medicare and cost control, The Commonwealth Fund

In contrast, one good sign for the specialty’s compensation and financial support is that “hospitals are still the hub of the healthcare system and need to be an important part of healthcare reform,” says Stuart Guterman, vice president for Medicare and cost control at The Commonwealth Fund, a New York foundation focused on improving healthcare delivery. Guterman says that while President Obama and congressional leaders are looking to cut the rate of growth in healthcare spending, the figure is already so high that there should still be plenty of resources in the system.

“If you took today’s spending and you increased it at the [GDP] growth rate for 10 years, I think we’re talking about something over $30 trillion over 10 years,” Guterman says. “And remember that we’re starting at a point that’s over 50% higher than any other country in the world. So, we’re talking about plenty of resources still in this healthcare system.”

With accountable care organizations, the specter of bundled payments, and penalties for readmitted patients, Guterman says that the pending issue for the specialty isn’t whether hospitalists—or other hospital-based practitioners—are going to get paid more or less, but rather what their compensation will be based on.

“Things like better coordination of care, sending the patients to the right place, having the patients in the right place, having them in the hospital if they need to be, or keeping them out of the hospital if they don’t need to be in the hospital,” he explains. “But the hospital is certainly a big part of that health system.”

In fact, physicians who play to the strengths of the new healthcare metrics—quality, value, lower-cost care—can probably earn as much compensation as, if not more than, they could in the traditional fee-for-service model hospitalists, Guterman says.

“The big point is to remind people that when we’re talking about controlling health spending growth, we’re still talking about a growing industry,” he notes. “We’re not talking about disenfranchising healthcare or providers. We’re talking about more reasonable growth and about, more than anything, paying for the right things. Folks ought to be able to do quite well if they do the right things.”

SOURCE: State of Hospital Medicine report, 2014

Multiple Uses

The SOHM report can be used as a measuring stick to compare against national and regional competitors and to provide data points for discussions with hospital administrators, says Team Hospitalist’s Weiss.

“This is vital in terms of recruiting physicians,” he says, “as well as negotiating with the hospital, as far as what the average investment is.”

Dr. Landis of SHM’s Practice Analysis Committee believes that having data points to make “resourcing decisions” with is particularly helpful, both in hiring and scheduling and in “right-sizing” hospital support for groups that are not self-sufficient.

“It is critical for physicians and their administrative partners to get the resourcing right, as inappropriately resourced groups [too much or too little] can quickly become unsustainable and/or unstable,” Dr. Landis says.

Take his group’s compensation.

“When we look at what we want to incent physicians, we’ll look at what other groups are doing,” Dr. Landis adds. “Are they using core measures? Are they using patient satisfaction? What about good citizenship? It’s one thing to say, ‘A hospital down the road is doing it.’ It’s another thing to take this book and say, ‘Let’s look the numbers up.’”

Of course, the wrinkle in benchmarking against national or regional figures is that HMGs can be “very particular,” says MGMA’s Robinson.

“We use benchmarks to give us an idea of what the pulse is, but we don’t use it as the only number,” she adds. “It’s very individualistic to the practice and to the program.”

Dr. Landis understands that point of view. Take his group’s policy on how much of hospitalists’ compensation is based on performance. The median component of compensation tied to performance for hospitalists nationwide is 6.6%, according to SOHM 2014. Dr. Landis’ group is at 15%. In meetings with his C-suite executives, he says he thinks in the back of his mind about how far outside the mean his group is in that regard. But he tempers that thought with the view that many hospitalists believe that performance and other metrics will continue to grow into a larger portion of hospitalists’ overall compensation.

“You have to be careful,” he says. “The first person to do an innovative, valuable thing isn’t going to be the 85%. You have to be careful not to stifle innovation. One of the cautions is not to use ‘just because everyone else is doing it means it’s the best way.’”

Weiss calls on an old adage in the industry: “If you’ve seen one hospitalist program, you’ve seen exactly one hospitalist program,” he says. “Because while they can be part of a large health system or a management company, while they try to have some commonality or some typical procedures, there’s still going to be individuality.”

Richard Quinn is a freelance writer in New Jersey.

The highlight of SHM’s biennial State of Hospital Medicine (SOHM) report is how much hospitalists earn. So it’s to be expected that rank-and-file practitioners and group leaders who read this year’s edition will first notice that median compensation for adult hospitalists rose 8% to $252,996 in 2013, according to data from the Medical Group Management Association (MGMA). The compensation data from MGMA is wrapped into the SOHM 2014 report this year.

But to stop there would be a wasted opportunity, says William “Tex” Landis, MD, FHM, medical director of Wellspan Hospitalists in York, Pa., and a member and former chair of SHM’s Practice Analysis Committee. Along with compensation, the report (available at www.hospitalmedicine.org/survey) delves into scheduling, productivity, staffing, how compensation is broken down, practice models, and dozens of other topics that hospital medicine group (HMG) leaders will find useful.

“Scope of services is a big one,” Dr. Landis adds. “What other things are hospital medicine groups around the country being held responsible for? Are we morphing into universal admitters? How involved in palliative care are we? What about transitions of care? How many hospital medicine groups are becoming involved in managing nursing home patients? What’s the relationship with surgical co-management? How much ICU work are we doing?”

Dr. Landis’ laundry list of unanswered questions might seem daunting, but that’s the point of the research SHM has been collecting and reporting for years. The society surveyed 499 groups, representing some 6,300 providers, to give the specialty’s most detailed list of most popular, if not best, practices.

“It has the usual limitations of any survey; however, it is the very best survey, quantity and quality, of hospital medicine groups,” Dr. Landis says. “And so it becomes the best source of information to make important decisions about resourcing and operating hospital medicine groups.”

Earnings Up

And, like it or not, compensation for providers typically is a HMG’s largest budget line. In that regard, the specialty appears to be doing well. Median compensation for adult hospitalists rose to a record high last year, according to the MGMA Physician Compensation and Production Survey: 2014 Report Based on 2013 Data. Half of respondents work in practices owned by hospitals/integrated delivery systems, down from 56% in SOHM 2012.

Although hospitalists in the South region continue to earn the most (median compensation $258,020, essentially static with the $258,793 figure reported in 2012), the region was the only one to report a decrease (see Table 1 for historical data). The largest percentage jump (11.8%) was for hospitalists in the West region ($249,894). Hospitalists in the Midwest saw a 10% increase ($261,868), while those in the East had both the smallest increase (4.8%) and the lowest median compensation ($238,676).

—R. Jeffrey Taylor, president and COO, IPC The Hospitalist Co., North Hollywood, Calif.

Part of the compensation increase is tied to upward pressure on productivity. Nationwide, median relative value units (RVUs) rose 3.3%, to 4,297 from 4,159. Median collection-to-work RVUs ticked up 6.8%, to 51.5 from 48.21 (see Table 2 for regional breakdowns). Production (10.5%) and performance (6.6%) are also slightly larger portions of mean compensation than they were in 2012, a figure many expect to increase further in future reports. The report also noted that academic/university hospitalists receive more in base pay, while hospitalists in private practice receive less.

Compensation and work volume will be intrinsically tied in the coming years, says R. Jeffrey Taylor, president and chief operating officer of IPC The Hospitalist Co., based in North Hollywood, Calif. And if pay outpaces productivity, “then it’s a bit concerning for the system at large,” he says.

“Particularly for whoever is subsidizing that shortfall, whether it’s a hospital employing doctors or an outsourced group employing the doctors but requiring a large subsidy from the hospital because the doctors are not seeing enough patient flow to pay their salary and benefits,” Taylor says.

More than 89% of HMGs rely on their host hospitals for financial support, according to the new data. The median support is $156,063 per full-time employee (FTE), which would total $1 million at just over seven FTEs. As healthcare reform progresses and hospitals’ budgets are increasingly burdened, Taylor says that pressure for hospitalists to generate enough revenue to cover their own salaries will grow. That sets up a likely showdown between hospitalists and their institutions; SOHM 2014 reported that just 6% of HMGs received enough income from professional fee revenue to cover expenses.

SOURCE: State of Hospital Medicine report, 2014

SOURCE: State of Hospital Medicine report, 2014

“Some productivity element in compensation plans, we believe, and I believe personally, is important,” Taylor says, later adding: “We already have a physician shortage and a shortage of people to see all these patients. It’s exacerbated by two things: lack of productivity and shift-model scheduling.”

To wit, IPC pays lower base salaries but provides bonuses tied to productivity and quality metrics. The average IPC hospitalist, Taylor says, earned more than $290,000 last year, nearly 15% above the median figure in the SOHM report. Between 30%-40% of that compensation, however, was earned via bonus tied to both “productivity and clinical achievement.”

Taylor, an outspoken advocate for moving away from the seven-on/seven-off scheduling model popular throughout hospital medicine, ties some of his doctors’ higher compensation to his firm’s preference for avoiding that schedule. But he’s not surprised the new report shows that 53.8% of responding HMGs use the model, up from 41.9% in 2012.

“It will be interesting to see what the data shows over the next three or four years,” he says, “if stipends, as we believe we are seeing, come under pressure and hospitals are doing more outsourcing.”

SOURCE: State of Hospital Medicine report, 2014

The PCP Link

Industry leaders use the information in the biennial reports to gauge where the specialty stands in the overall healthcare spectrum. Dea Robinson, MA, FACMPE, CPC, director of consulting for MGMA Health Care Consulting Group, says that the growth of hospital medicine (HM) compensation is tied to that of primary care physicians (PCPs).

“I don’t think we can look at hospitalists without looking at primary care, because it’s really an extension of primary care,” says Robinson, a member of SHM’s Practice Management Committee. “As primary care compensation increases, hospitalists’ compensation might increase as well. And with the focus on patient-centered medical homes, which is basically primary care centered, that might very well be part of the driver in the future of seeing hospitalists grow.”

While facing a well-known physician shortage, primary care’s compensation growth also lags behind HM. For example, median compensation for hospitalists rose 8%; it increased 5.5% for PCPs.

“When it comes to growth of the two individual industries, I think they are connected in some way,” she adds. “But in terms of the compensation, now we’re starting to see different codes that hospitalists are able to use but that primary care used to use exclusively. So, you really see more of an extension and a collaboration between true primary care and hospitalists.”

Bryan Weiss, MBA, FHM, managing director of the consulting services practice at Irving, Texas-based MedSynergies, agrees that hospitalists and PCPs are connected. He believes the higher compensation figures are a sign of how young HM is as a specialty. He fears compensation “is probably growing too fast.”

“This takes me back to the 1990s, with the private [physician practice management]-type model, where it just grew so fast that the bottom fell out,” says Weiss, a member of Team Hospitalist. “Not that I think the bottom is going to fall out of hospital medicine, but a lot of this is reminiscent of that, and I think there’s going to be a ceiling, or at least a slowing down.”

—Stuart Guterman, vice president, Medicare and cost control, The Commonwealth Fund

In contrast, one good sign for the specialty’s compensation and financial support is that “hospitals are still the hub of the healthcare system and need to be an important part of healthcare reform,” says Stuart Guterman, vice president for Medicare and cost control at The Commonwealth Fund, a New York foundation focused on improving healthcare delivery. Guterman says that while President Obama and congressional leaders are looking to cut the rate of growth in healthcare spending, the figure is already so high that there should still be plenty of resources in the system.

“If you took today’s spending and you increased it at the [GDP] growth rate for 10 years, I think we’re talking about something over $30 trillion over 10 years,” Guterman says. “And remember that we’re starting at a point that’s over 50% higher than any other country in the world. So, we’re talking about plenty of resources still in this healthcare system.”

With accountable care organizations, the specter of bundled payments, and penalties for readmitted patients, Guterman says that the pending issue for the specialty isn’t whether hospitalists—or other hospital-based practitioners—are going to get paid more or less, but rather what their compensation will be based on.

“Things like better coordination of care, sending the patients to the right place, having the patients in the right place, having them in the hospital if they need to be, or keeping them out of the hospital if they don’t need to be in the hospital,” he explains. “But the hospital is certainly a big part of that health system.”

In fact, physicians who play to the strengths of the new healthcare metrics—quality, value, lower-cost care—can probably earn as much compensation as, if not more than, they could in the traditional fee-for-service model hospitalists, Guterman says.

“The big point is to remind people that when we’re talking about controlling health spending growth, we’re still talking about a growing industry,” he notes. “We’re not talking about disenfranchising healthcare or providers. We’re talking about more reasonable growth and about, more than anything, paying for the right things. Folks ought to be able to do quite well if they do the right things.”

SOURCE: State of Hospital Medicine report, 2014

Multiple Uses

The SOHM report can be used as a measuring stick to compare against national and regional competitors and to provide data points for discussions with hospital administrators, says Team Hospitalist’s Weiss.

“This is vital in terms of recruiting physicians,” he says, “as well as negotiating with the hospital, as far as what the average investment is.”

Dr. Landis of SHM’s Practice Analysis Committee believes that having data points to make “resourcing decisions” with is particularly helpful, both in hiring and scheduling and in “right-sizing” hospital support for groups that are not self-sufficient.

“It is critical for physicians and their administrative partners to get the resourcing right, as inappropriately resourced groups [too much or too little] can quickly become unsustainable and/or unstable,” Dr. Landis says.

Take his group’s compensation.

“When we look at what we want to incent physicians, we’ll look at what other groups are doing,” Dr. Landis adds. “Are they using core measures? Are they using patient satisfaction? What about good citizenship? It’s one thing to say, ‘A hospital down the road is doing it.’ It’s another thing to take this book and say, ‘Let’s look the numbers up.’”

Of course, the wrinkle in benchmarking against national or regional figures is that HMGs can be “very particular,” says MGMA’s Robinson.

“We use benchmarks to give us an idea of what the pulse is, but we don’t use it as the only number,” she adds. “It’s very individualistic to the practice and to the program.”

Dr. Landis understands that point of view. Take his group’s policy on how much of hospitalists’ compensation is based on performance. The median component of compensation tied to performance for hospitalists nationwide is 6.6%, according to SOHM 2014. Dr. Landis’ group is at 15%. In meetings with his C-suite executives, he says he thinks in the back of his mind about how far outside the mean his group is in that regard. But he tempers that thought with the view that many hospitalists believe that performance and other metrics will continue to grow into a larger portion of hospitalists’ overall compensation.

“You have to be careful,” he says. “The first person to do an innovative, valuable thing isn’t going to be the 85%. You have to be careful not to stifle innovation. One of the cautions is not to use ‘just because everyone else is doing it means it’s the best way.’”

Weiss calls on an old adage in the industry: “If you’ve seen one hospitalist program, you’ve seen exactly one hospitalist program,” he says. “Because while they can be part of a large health system or a management company, while they try to have some commonality or some typical procedures, there’s still going to be individuality.”

Richard Quinn is a freelance writer in New Jersey.

The highlight of SHM’s biennial State of Hospital Medicine (SOHM) report is how much hospitalists earn. So it’s to be expected that rank-and-file practitioners and group leaders who read this year’s edition will first notice that median compensation for adult hospitalists rose 8% to $252,996 in 2013, according to data from the Medical Group Management Association (MGMA). The compensation data from MGMA is wrapped into the SOHM 2014 report this year.

But to stop there would be a wasted opportunity, says William “Tex” Landis, MD, FHM, medical director of Wellspan Hospitalists in York, Pa., and a member and former chair of SHM’s Practice Analysis Committee. Along with compensation, the report (available at www.hospitalmedicine.org/survey) delves into scheduling, productivity, staffing, how compensation is broken down, practice models, and dozens of other topics that hospital medicine group (HMG) leaders will find useful.

“Scope of services is a big one,” Dr. Landis adds. “What other things are hospital medicine groups around the country being held responsible for? Are we morphing into universal admitters? How involved in palliative care are we? What about transitions of care? How many hospital medicine groups are becoming involved in managing nursing home patients? What’s the relationship with surgical co-management? How much ICU work are we doing?”

Dr. Landis’ laundry list of unanswered questions might seem daunting, but that’s the point of the research SHM has been collecting and reporting for years. The society surveyed 499 groups, representing some 6,300 providers, to give the specialty’s most detailed list of most popular, if not best, practices.

“It has the usual limitations of any survey; however, it is the very best survey, quantity and quality, of hospital medicine groups,” Dr. Landis says. “And so it becomes the best source of information to make important decisions about resourcing and operating hospital medicine groups.”

Earnings Up

And, like it or not, compensation for providers typically is a HMG’s largest budget line. In that regard, the specialty appears to be doing well. Median compensation for adult hospitalists rose to a record high last year, according to the MGMA Physician Compensation and Production Survey: 2014 Report Based on 2013 Data. Half of respondents work in practices owned by hospitals/integrated delivery systems, down from 56% in SOHM 2012.

Although hospitalists in the South region continue to earn the most (median compensation $258,020, essentially static with the $258,793 figure reported in 2012), the region was the only one to report a decrease (see Table 1 for historical data). The largest percentage jump (11.8%) was for hospitalists in the West region ($249,894). Hospitalists in the Midwest saw a 10% increase ($261,868), while those in the East had both the smallest increase (4.8%) and the lowest median compensation ($238,676).

—R. Jeffrey Taylor, president and COO, IPC The Hospitalist Co., North Hollywood, Calif.

Part of the compensation increase is tied to upward pressure on productivity. Nationwide, median relative value units (RVUs) rose 3.3%, to 4,297 from 4,159. Median collection-to-work RVUs ticked up 6.8%, to 51.5 from 48.21 (see Table 2 for regional breakdowns). Production (10.5%) and performance (6.6%) are also slightly larger portions of mean compensation than they were in 2012, a figure many expect to increase further in future reports. The report also noted that academic/university hospitalists receive more in base pay, while hospitalists in private practice receive less.

Compensation and work volume will be intrinsically tied in the coming years, says R. Jeffrey Taylor, president and chief operating officer of IPC The Hospitalist Co., based in North Hollywood, Calif. And if pay outpaces productivity, “then it’s a bit concerning for the system at large,” he says.

“Particularly for whoever is subsidizing that shortfall, whether it’s a hospital employing doctors or an outsourced group employing the doctors but requiring a large subsidy from the hospital because the doctors are not seeing enough patient flow to pay their salary and benefits,” Taylor says.

More than 89% of HMGs rely on their host hospitals for financial support, according to the new data. The median support is $156,063 per full-time employee (FTE), which would total $1 million at just over seven FTEs. As healthcare reform progresses and hospitals’ budgets are increasingly burdened, Taylor says that pressure for hospitalists to generate enough revenue to cover their own salaries will grow. That sets up a likely showdown between hospitalists and their institutions; SOHM 2014 reported that just 6% of HMGs received enough income from professional fee revenue to cover expenses.

SOURCE: State of Hospital Medicine report, 2014

SOURCE: State of Hospital Medicine report, 2014

“Some productivity element in compensation plans, we believe, and I believe personally, is important,” Taylor says, later adding: “We already have a physician shortage and a shortage of people to see all these patients. It’s exacerbated by two things: lack of productivity and shift-model scheduling.”

To wit, IPC pays lower base salaries but provides bonuses tied to productivity and quality metrics. The average IPC hospitalist, Taylor says, earned more than $290,000 last year, nearly 15% above the median figure in the SOHM report. Between 30%-40% of that compensation, however, was earned via bonus tied to both “productivity and clinical achievement.”

Taylor, an outspoken advocate for moving away from the seven-on/seven-off scheduling model popular throughout hospital medicine, ties some of his doctors’ higher compensation to his firm’s preference for avoiding that schedule. But he’s not surprised the new report shows that 53.8% of responding HMGs use the model, up from 41.9% in 2012.

“It will be interesting to see what the data shows over the next three or four years,” he says, “if stipends, as we believe we are seeing, come under pressure and hospitals are doing more outsourcing.”

SOURCE: State of Hospital Medicine report, 2014

The PCP Link

Industry leaders use the information in the biennial reports to gauge where the specialty stands in the overall healthcare spectrum. Dea Robinson, MA, FACMPE, CPC, director of consulting for MGMA Health Care Consulting Group, says that the growth of hospital medicine (HM) compensation is tied to that of primary care physicians (PCPs).

“I don’t think we can look at hospitalists without looking at primary care, because it’s really an extension of primary care,” says Robinson, a member of SHM’s Practice Management Committee. “As primary care compensation increases, hospitalists’ compensation might increase as well. And with the focus on patient-centered medical homes, which is basically primary care centered, that might very well be part of the driver in the future of seeing hospitalists grow.”

While facing a well-known physician shortage, primary care’s compensation growth also lags behind HM. For example, median compensation for hospitalists rose 8%; it increased 5.5% for PCPs.

“When it comes to growth of the two individual industries, I think they are connected in some way,” she adds. “But in terms of the compensation, now we’re starting to see different codes that hospitalists are able to use but that primary care used to use exclusively. So, you really see more of an extension and a collaboration between true primary care and hospitalists.”