User login

Digital cohorts within the social mediome to circumvent conventional research challenges?

We are becoming comfortable with the concept of a sharing economy, where resources are shared among many individuals using online forums. Whether activities involve sharing rides (Uber, Lyft, and others), accommodations (Airbnb), or information (social media), underlying attributes include reduced transactional costs, enhanced information transparency, dynamic feedback, and socialization of opportunity. As health care systems realize that they are changing from direct-to-business to a direct-to-customer model, their ability to connect directly with individuals will become a foundational strategy.

This month’s column introduces us to social media as a research tool. Information derived from social media sites can be harvested for critical clinical information (the Centers for Disease and Control and Prevention tracks the spread of influenza using social media analytic tools), research data (patient preferences), and as a recruitment method for clinical studies. Kulanthaivel and colleagues have described their experiences and literature review to help us imagine new ways to collect data at markedly reduced transaction costs (compared to a formal clinical trial). While there are many cautions about the use of social media in your practice or research, we are only beginning to understand its potential.

John I. Allen, MD, MBA, AGAF

Editor in Chief

Medical knowledge, culminating from the collection and translation of patient data, is the primary objective of the clinical research paradigm. The successful conduct of this traditional model has become even more challenging with expansion of costs and a dwindling research infrastructure. Beyond systemic issues, conventional research methods are burdened further by minimal patient engagement, inadequate staffing, and geographic limitations to recruitment. Clinical research also has failed to keep pace with patient demands, and the limited scope of well-funded, disease-specific investigations have left many patients feeling disenfranchised. Social media venues may represent a viable option to surpass these current and evolving barriers when used as an adjunctive approach to traditional clinical investigation.

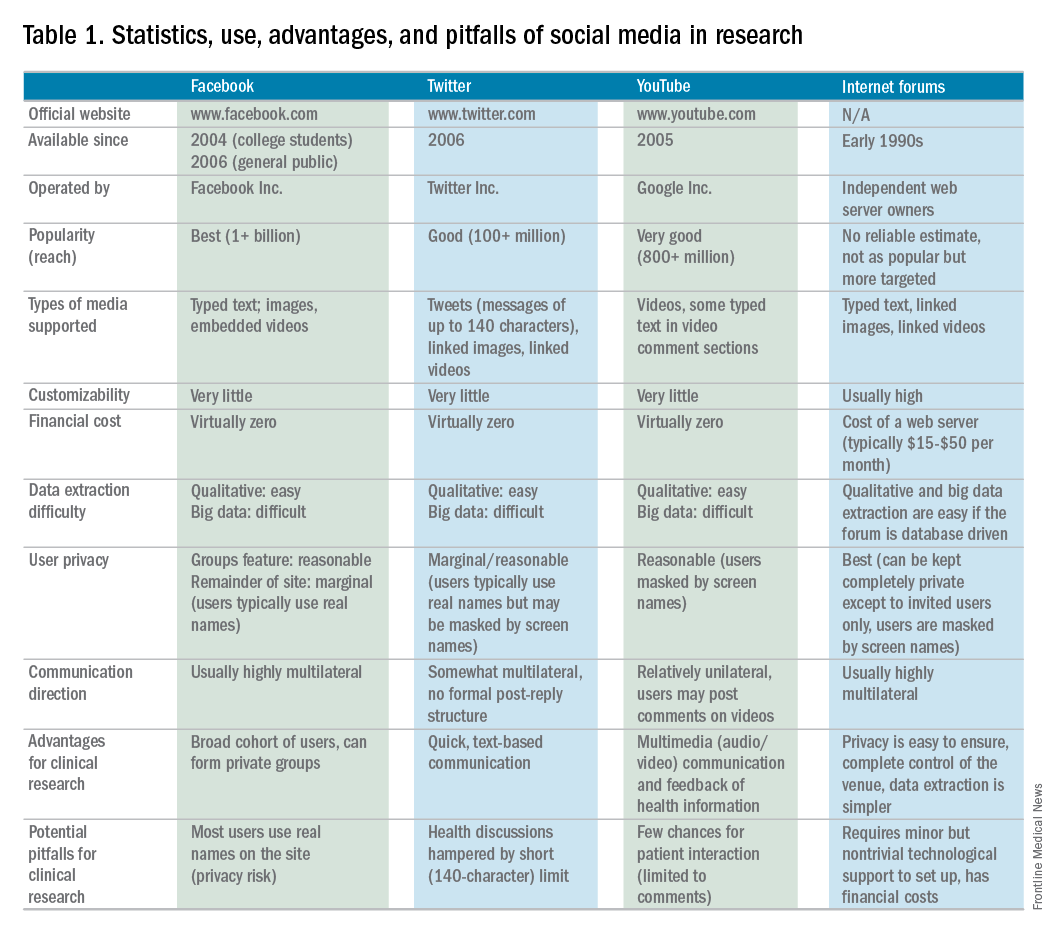

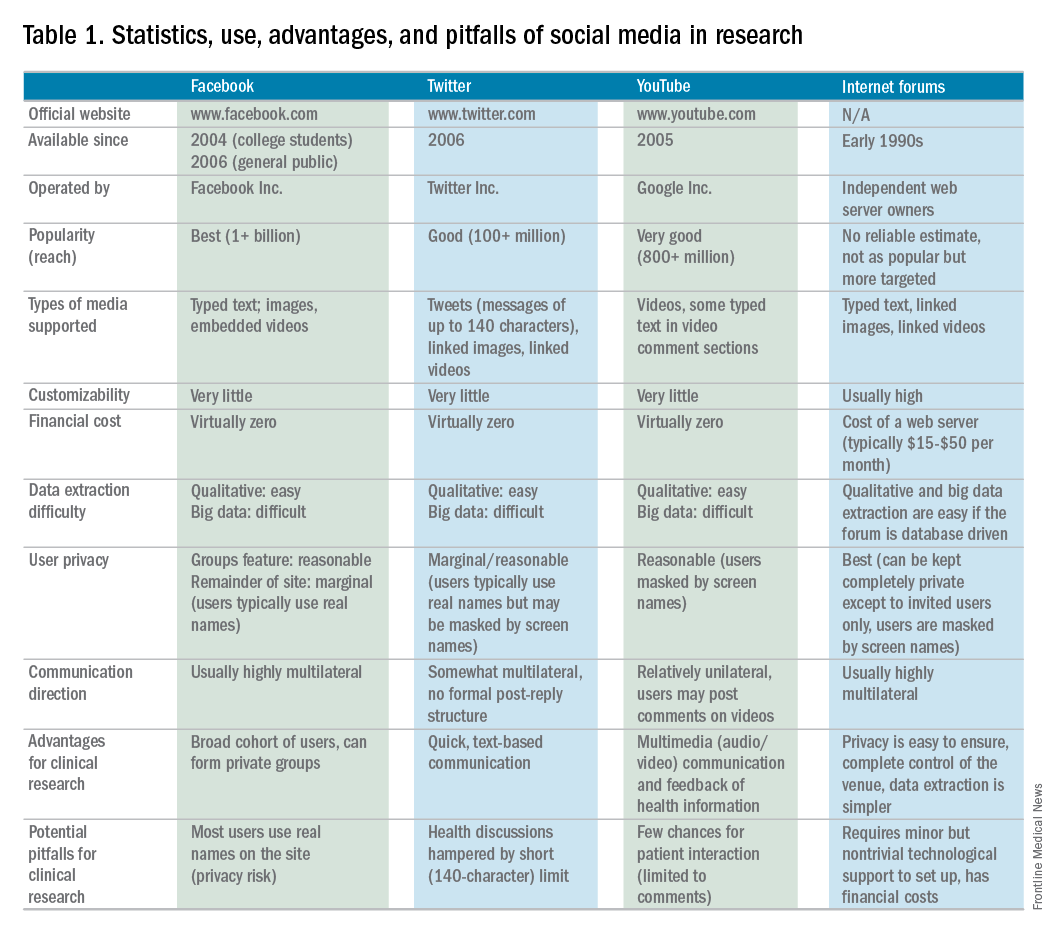

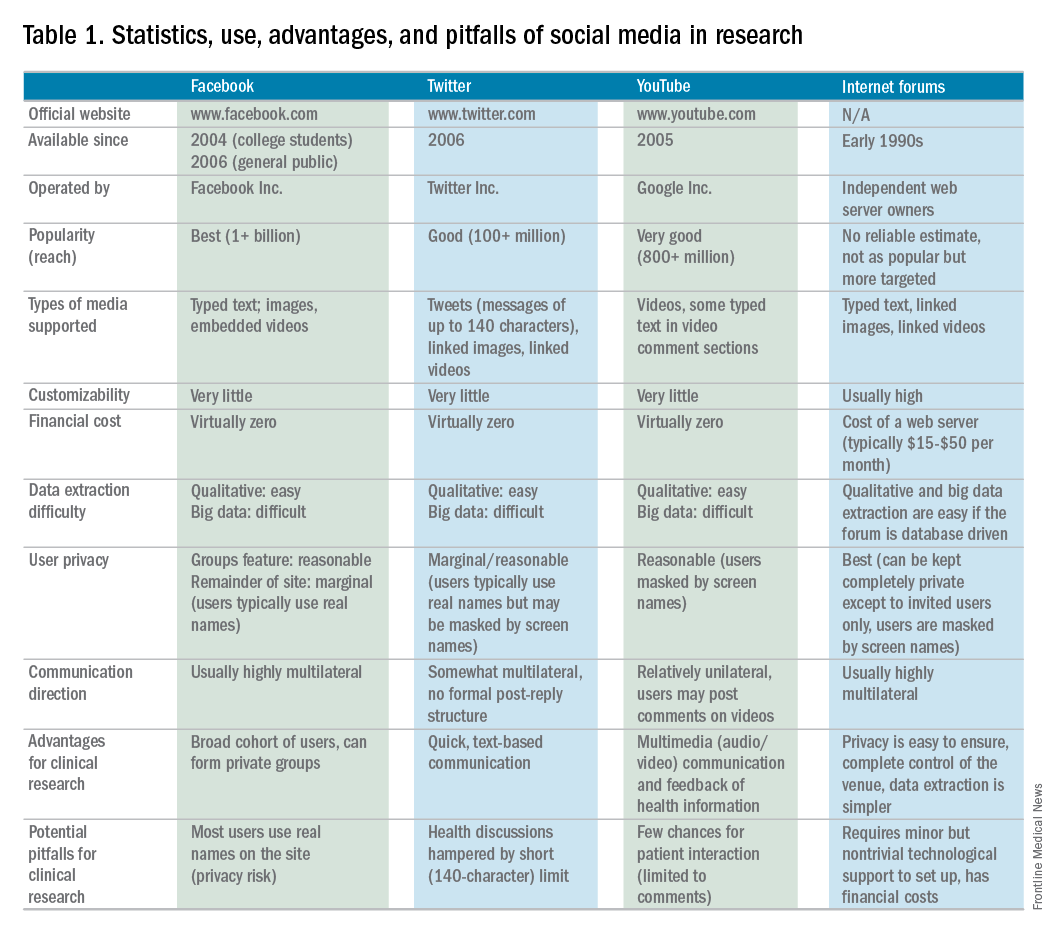

Advantages and pitfalls in social media research

SM is a new frontier containing a wide spectrum of clinical and qualitative data from connected users (patients). Collection and examination of either individuals’ or groups’ SM information use can provide insight into qualitative life experiences, just as analysis of biologic samples can enable dissection of genetic disease underpinnings. This mediome is analogous to the human genome, both in content and utility.1 Analyzing data streams from SM for interpersonal interactions, message content, and even frequency can provide digital investigators with volumes of information that otherwise would remain unattainable.

Several limitations and potential risks of SM for medical research should be addressed, including the possible compromise of privacy and confidentiality, the use and dissemination of medical advice and information, potential demographic biases, and a required trust of the investigator by patients. Many of these challenges can be similar to traditional methods, however, as in the conventional model, careful management can drastically reduce unwanted study issues.

The risk of Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act violations must be considered seriously in the context of patient–researcher interactions on SM. Because of the relatively public nature of these venues, patient confidentiality may be at risk if patients choose to divulge personal medical information. However, if proper protective measures are taken to ensure that the venue is secure (e.g., a private or closed group on Facebook or a by-invitation-only online Internet forum), and the researcher vets all patients who request entrance into the group, this risk may be minimized. Moreover, to further reduce any legal liability, the researcher should not provide any medical advice to patients who participate in a SM study. The drive to provide medical direction in study patients with clinical need may be strong because collaborative relationships between investigator and patients are likely to form. Furthermore, digital access to investigators on SM commonly becomes easy for patients. Safe approaches to communication could include redirecting patients to consult with their own doctor for advice, unbiased dissemination of disease-specific educational materials, or depiction of only institutional review board–approved study materials.7,8

The perception that only younger populations use SM may appear to be a significant limitation for its implementation in clinical research. However, this limitation is rapidly becoming less significant because recent studies have shown that the use of SM has become increasingly common among older adults. As of 2014, more than half of the US adult population used Facebook, including 73% and 63% of Internet-using adults ages 30–49 and 50–64 years, respectively.10 SM may not be suitable for all diseases, however, there is likely significant demographic overlap for many disease populations.

Finally, it is imperative for researchers to gain the trust of patients on SM to effectively use these venues for research purposes. Because patient–researcher interaction does not occur face-to-face on these platforms, gaining the trust of patients may be more difficult than it would be in a clinical setting. Thus, patient–patient and patient–researcher communications within SM platforms must be cultivated carefully to instill participant confidence in the research being performed on their behalf. One of the authors (C.L.) has established an SM educational model for this exchange.4 Specifically, he provides patients with a distillation of current field research by posting updates in a research-specific Facebook group and on Twitter. This model not only empowers patients with disease education, it also solidifies the importance of patient investment in disease-specific research. Furthermore, invested patients bring ideas to research, take a more educated and proactive role in their care team, and, ultimately, return to seek more study involvement.

Social media in rare disease research

Rare diseases (conditions with a prevalence of less than 200,000 patients in North America), in particular, are prime for high-yield results and community impact using novel SM approaches. This is the result of established digital support groups, publications with historically low study numbers, and few focused investigators. Several studies of rare diseases have shown considerable advantages of using SM as a study tool. For instance, an existing neuroendocrine cervical cancer Facebook support group recently was used to recruit a geographically widespread cohort of patients with this rare cancer. Through an online survey posted in the Facebook group, patients were able to provide specific information on their treatment, disease, and symptom history, current disease status, and quality of life, including various psychological factors. Without the use of SM, collecting this information would have been virtually impossible because the patients were treated at 51 cancer centers across the country.14

Currently, the use of SM in hepatology research, focused specifically on autoimmune hepatitis (AIH), is under exploration at Indiana University. AIH is a rare autoimmune liver disease that results in immune-mediated destruction of liver cells, possibly resulting in fibrosis, cirrhosis, or liver failure if treatment is unsuccessful. One of the authors (C.L.) used both Facebook and Twitter to construct a large study group of individuals affected with AIH called the Autoimmune Hepatitis Research Network (AHRN; 1,500 members) during the past 2 years.4 Interested individuals have joined this research group after searching for AIH online support groups or reading shared AHRN posts on other media platforms. Between April 2015 and April 2016, there were posts by more than 750 unique active members (more than 50% of the group contributes to discussions), most of whom appear to be either caregivers of AIH patients or AIH patients themselves.

Preliminary informational analysis on this group has shown that C.L. and study collaborators have been able to uncover rich clinical and nonclinical information that otherwise would remain unknown. This research was performed by semi-automated download of the Facebook group’s content and subsequent semantic analysis. Qualitative analysis also was performed by direct reading of patient narratives. Collected clinical information has included histories of medication side effects, familial autoimmune diseases, and comorbid conditions. The most common factors that patients were unlikely to discuss with a provider (e.g., financial issues, employment, personal relationships, use of supplements, and alcohol use) frequently were discussed in the AHRN group, allowing a more transparent view of the complete disease experience.

Beyond research conducted in the current paradigm, the AHRN has provided a rich community construct in which patients offer each other social support. The patient impression of AHRN on Facebook has been overwhelmingly positive, and patients often wonder why such a model has not been used with other diseases. The close digital interaction the author (C.L.) has had with numerous patients and families has promoted other benefits of this methodology: more than 40 new AIH patients from outside Indiana have traveled to Indiana University for medical consultation despite no advertisement.

Conclusions

SM has the potential to transform health care research as a supplement to traditional research methods. Compared with a conventional research model, this methodology has proven to be cost and time effective, wide reaching, and similarly capable of data collection. Use of SM in research has tremendous potential to direct patient-centered research because invested patient collaborators can take an active role in their own disease and may hone investigatory focus on stakeholder priorities. Limitations to this method are known, however; if implemented cautiously, these can be mitigated. Investment in and application of the social mediome by investigators and patients has the potential to support and transform research that otherwise would be impossible.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to extend their gratitude to the members of the Autoimmune Hepatitis Research Network for their continued proactivity and engagement in autoimmune hepatitis research. Furthermore, the authors are grateful to Dr. Naga Chalasani for his continued mentorship and extensive contributions to the development of social media approaches in clinical investigation.

References

1. Asch, D.A., Rader, D.J., Merchant, R.M. Mining the social mediome. Trends Mol Med. 2015;21:528-9.

2. Brotherton, C.S., Martin, C.A., Long, M.D. et al. Avoidance of fiber is associated with greater risk of Crohn’s disease flare in a 6-month period. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;14:1130-6.

3. Fenner, Y., Garland, S.M., Moore, E.E., et al. Web-based recruiting for health research using a social networking site: an exploratory study. J Med Internet Res. 2012;14:e20.

4. Lammert, C., Comerford, M., Love, J., et al. Investigation gone viral: application of the social mediasphere in research. Gastroenterology. 2015;149:839-43.

5. Wicks, P., Massagli, M., Frost, J., et al. Sharing health data for better outcomes on PatientsLikeMe. J Med Internet Res. 2010;12:e19.

6. Admon, L., Haefner, J.K., Kolenic, G.E., et al. Recruiting pregnant patients for survey research: a head to head comparison of social media-based versus clinic-based approaches. J Med Internet Res. 2016;18:e326.

7. Farnan, J.M., Sulmasy, L.S., Chaudhry, H. Online medical professionalism. Ann Intern Med. 2013;159:158-9.

8. Massachusetts Medical Society: Social Media Guidelines for Physicians. Available from: http://www.massmed.org/Physicians/Legal-and-Regulatory/Social-Media-Guidelines-for-Physicians/#. Accessed: January 3, 2017.

9. Pirraglia, P.A. Kravitz, R.L. Social media: new opportunities, new ethical concerns. J Gen Intern Med. 2013;28:165-6.

10. Duggan, M., Ellison, N.B., Lampe, C. et al. Demographics of key social networking platforms. (Available from:) (Accessed: January 4, 2017) Pew Res Cent Internet Sci Tech. 2015; http://www.pewinternet.org/2015/01/09/demographics-of-key-social-networking-platforms-2

11. Kang, X., Zhao, L., Leung, F., et al. Delivery of Instructions via mobile social media app increases quality of bowel preparation. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;14:429-35.

12. Bajaj, J.S., Heuman, D.M., Sterling, R.K., et al. Validation of EncephalApp, Smartphone-based Stroop test, for the diagnosis of covert hepatic encephalopathy. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;13:1828-35.

13. Riaz, M.S. Atreja, A. Personalized technologies in chronic gastrointestinal disorders: self-monitoring and remote sensor technologies. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;14:1697-705.

14. Zaid, T., Burzawa, J., Basen-Engquist, K., et al. Use of social media to conduct a cross-sectional epidemiologic and quality of life survey of patients with neuroendocrine carcinoma of the cervix: a feasibility study. Gynecol Oncol. 2014;132:149-53.

15. Schumacher, K.R., Stringer, K.A., Donohue, J.E., et al. Social media methods for studying rare diseases. Pediatrics. 2014;133:e1345–53.

Dr. Kulanthaivel and Dr. Jones are in the school of informatics and computing, Purdue University, Indiana University, Indianapolis; Dr. Fogel and Dr. Lammert are in the department of digestive and liver diseases, Indiana University School of Medicine, Indianapolis. This study was supported by KL2TR001106 and UL1TR001108 from the National Institutes of Health, and the Clinical and Translational Sciences Award from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (C.L.). The authors disclose no conflicts.

We are becoming comfortable with the concept of a sharing economy, where resources are shared among many individuals using online forums. Whether activities involve sharing rides (Uber, Lyft, and others), accommodations (Airbnb), or information (social media), underlying attributes include reduced transactional costs, enhanced information transparency, dynamic feedback, and socialization of opportunity. As health care systems realize that they are changing from direct-to-business to a direct-to-customer model, their ability to connect directly with individuals will become a foundational strategy.

This month’s column introduces us to social media as a research tool. Information derived from social media sites can be harvested for critical clinical information (the Centers for Disease and Control and Prevention tracks the spread of influenza using social media analytic tools), research data (patient preferences), and as a recruitment method for clinical studies. Kulanthaivel and colleagues have described their experiences and literature review to help us imagine new ways to collect data at markedly reduced transaction costs (compared to a formal clinical trial). While there are many cautions about the use of social media in your practice or research, we are only beginning to understand its potential.

John I. Allen, MD, MBA, AGAF

Editor in Chief

Medical knowledge, culminating from the collection and translation of patient data, is the primary objective of the clinical research paradigm. The successful conduct of this traditional model has become even more challenging with expansion of costs and a dwindling research infrastructure. Beyond systemic issues, conventional research methods are burdened further by minimal patient engagement, inadequate staffing, and geographic limitations to recruitment. Clinical research also has failed to keep pace with patient demands, and the limited scope of well-funded, disease-specific investigations have left many patients feeling disenfranchised. Social media venues may represent a viable option to surpass these current and evolving barriers when used as an adjunctive approach to traditional clinical investigation.

Advantages and pitfalls in social media research

SM is a new frontier containing a wide spectrum of clinical and qualitative data from connected users (patients). Collection and examination of either individuals’ or groups’ SM information use can provide insight into qualitative life experiences, just as analysis of biologic samples can enable dissection of genetic disease underpinnings. This mediome is analogous to the human genome, both in content and utility.1 Analyzing data streams from SM for interpersonal interactions, message content, and even frequency can provide digital investigators with volumes of information that otherwise would remain unattainable.

Several limitations and potential risks of SM for medical research should be addressed, including the possible compromise of privacy and confidentiality, the use and dissemination of medical advice and information, potential demographic biases, and a required trust of the investigator by patients. Many of these challenges can be similar to traditional methods, however, as in the conventional model, careful management can drastically reduce unwanted study issues.

The risk of Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act violations must be considered seriously in the context of patient–researcher interactions on SM. Because of the relatively public nature of these venues, patient confidentiality may be at risk if patients choose to divulge personal medical information. However, if proper protective measures are taken to ensure that the venue is secure (e.g., a private or closed group on Facebook or a by-invitation-only online Internet forum), and the researcher vets all patients who request entrance into the group, this risk may be minimized. Moreover, to further reduce any legal liability, the researcher should not provide any medical advice to patients who participate in a SM study. The drive to provide medical direction in study patients with clinical need may be strong because collaborative relationships between investigator and patients are likely to form. Furthermore, digital access to investigators on SM commonly becomes easy for patients. Safe approaches to communication could include redirecting patients to consult with their own doctor for advice, unbiased dissemination of disease-specific educational materials, or depiction of only institutional review board–approved study materials.7,8

The perception that only younger populations use SM may appear to be a significant limitation for its implementation in clinical research. However, this limitation is rapidly becoming less significant because recent studies have shown that the use of SM has become increasingly common among older adults. As of 2014, more than half of the US adult population used Facebook, including 73% and 63% of Internet-using adults ages 30–49 and 50–64 years, respectively.10 SM may not be suitable for all diseases, however, there is likely significant demographic overlap for many disease populations.

Finally, it is imperative for researchers to gain the trust of patients on SM to effectively use these venues for research purposes. Because patient–researcher interaction does not occur face-to-face on these platforms, gaining the trust of patients may be more difficult than it would be in a clinical setting. Thus, patient–patient and patient–researcher communications within SM platforms must be cultivated carefully to instill participant confidence in the research being performed on their behalf. One of the authors (C.L.) has established an SM educational model for this exchange.4 Specifically, he provides patients with a distillation of current field research by posting updates in a research-specific Facebook group and on Twitter. This model not only empowers patients with disease education, it also solidifies the importance of patient investment in disease-specific research. Furthermore, invested patients bring ideas to research, take a more educated and proactive role in their care team, and, ultimately, return to seek more study involvement.

Social media in rare disease research

Rare diseases (conditions with a prevalence of less than 200,000 patients in North America), in particular, are prime for high-yield results and community impact using novel SM approaches. This is the result of established digital support groups, publications with historically low study numbers, and few focused investigators. Several studies of rare diseases have shown considerable advantages of using SM as a study tool. For instance, an existing neuroendocrine cervical cancer Facebook support group recently was used to recruit a geographically widespread cohort of patients with this rare cancer. Through an online survey posted in the Facebook group, patients were able to provide specific information on their treatment, disease, and symptom history, current disease status, and quality of life, including various psychological factors. Without the use of SM, collecting this information would have been virtually impossible because the patients were treated at 51 cancer centers across the country.14

Currently, the use of SM in hepatology research, focused specifically on autoimmune hepatitis (AIH), is under exploration at Indiana University. AIH is a rare autoimmune liver disease that results in immune-mediated destruction of liver cells, possibly resulting in fibrosis, cirrhosis, or liver failure if treatment is unsuccessful. One of the authors (C.L.) used both Facebook and Twitter to construct a large study group of individuals affected with AIH called the Autoimmune Hepatitis Research Network (AHRN; 1,500 members) during the past 2 years.4 Interested individuals have joined this research group after searching for AIH online support groups or reading shared AHRN posts on other media platforms. Between April 2015 and April 2016, there were posts by more than 750 unique active members (more than 50% of the group contributes to discussions), most of whom appear to be either caregivers of AIH patients or AIH patients themselves.

Preliminary informational analysis on this group has shown that C.L. and study collaborators have been able to uncover rich clinical and nonclinical information that otherwise would remain unknown. This research was performed by semi-automated download of the Facebook group’s content and subsequent semantic analysis. Qualitative analysis also was performed by direct reading of patient narratives. Collected clinical information has included histories of medication side effects, familial autoimmune diseases, and comorbid conditions. The most common factors that patients were unlikely to discuss with a provider (e.g., financial issues, employment, personal relationships, use of supplements, and alcohol use) frequently were discussed in the AHRN group, allowing a more transparent view of the complete disease experience.

Beyond research conducted in the current paradigm, the AHRN has provided a rich community construct in which patients offer each other social support. The patient impression of AHRN on Facebook has been overwhelmingly positive, and patients often wonder why such a model has not been used with other diseases. The close digital interaction the author (C.L.) has had with numerous patients and families has promoted other benefits of this methodology: more than 40 new AIH patients from outside Indiana have traveled to Indiana University for medical consultation despite no advertisement.

Conclusions

SM has the potential to transform health care research as a supplement to traditional research methods. Compared with a conventional research model, this methodology has proven to be cost and time effective, wide reaching, and similarly capable of data collection. Use of SM in research has tremendous potential to direct patient-centered research because invested patient collaborators can take an active role in their own disease and may hone investigatory focus on stakeholder priorities. Limitations to this method are known, however; if implemented cautiously, these can be mitigated. Investment in and application of the social mediome by investigators and patients has the potential to support and transform research that otherwise would be impossible.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to extend their gratitude to the members of the Autoimmune Hepatitis Research Network for their continued proactivity and engagement in autoimmune hepatitis research. Furthermore, the authors are grateful to Dr. Naga Chalasani for his continued mentorship and extensive contributions to the development of social media approaches in clinical investigation.

References

1. Asch, D.A., Rader, D.J., Merchant, R.M. Mining the social mediome. Trends Mol Med. 2015;21:528-9.

2. Brotherton, C.S., Martin, C.A., Long, M.D. et al. Avoidance of fiber is associated with greater risk of Crohn’s disease flare in a 6-month period. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;14:1130-6.

3. Fenner, Y., Garland, S.M., Moore, E.E., et al. Web-based recruiting for health research using a social networking site: an exploratory study. J Med Internet Res. 2012;14:e20.

4. Lammert, C., Comerford, M., Love, J., et al. Investigation gone viral: application of the social mediasphere in research. Gastroenterology. 2015;149:839-43.

5. Wicks, P., Massagli, M., Frost, J., et al. Sharing health data for better outcomes on PatientsLikeMe. J Med Internet Res. 2010;12:e19.

6. Admon, L., Haefner, J.K., Kolenic, G.E., et al. Recruiting pregnant patients for survey research: a head to head comparison of social media-based versus clinic-based approaches. J Med Internet Res. 2016;18:e326.

7. Farnan, J.M., Sulmasy, L.S., Chaudhry, H. Online medical professionalism. Ann Intern Med. 2013;159:158-9.

8. Massachusetts Medical Society: Social Media Guidelines for Physicians. Available from: http://www.massmed.org/Physicians/Legal-and-Regulatory/Social-Media-Guidelines-for-Physicians/#. Accessed: January 3, 2017.

9. Pirraglia, P.A. Kravitz, R.L. Social media: new opportunities, new ethical concerns. J Gen Intern Med. 2013;28:165-6.

10. Duggan, M., Ellison, N.B., Lampe, C. et al. Demographics of key social networking platforms. (Available from:) (Accessed: January 4, 2017) Pew Res Cent Internet Sci Tech. 2015; http://www.pewinternet.org/2015/01/09/demographics-of-key-social-networking-platforms-2

11. Kang, X., Zhao, L., Leung, F., et al. Delivery of Instructions via mobile social media app increases quality of bowel preparation. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;14:429-35.

12. Bajaj, J.S., Heuman, D.M., Sterling, R.K., et al. Validation of EncephalApp, Smartphone-based Stroop test, for the diagnosis of covert hepatic encephalopathy. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;13:1828-35.

13. Riaz, M.S. Atreja, A. Personalized technologies in chronic gastrointestinal disorders: self-monitoring and remote sensor technologies. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;14:1697-705.

14. Zaid, T., Burzawa, J., Basen-Engquist, K., et al. Use of social media to conduct a cross-sectional epidemiologic and quality of life survey of patients with neuroendocrine carcinoma of the cervix: a feasibility study. Gynecol Oncol. 2014;132:149-53.

15. Schumacher, K.R., Stringer, K.A., Donohue, J.E., et al. Social media methods for studying rare diseases. Pediatrics. 2014;133:e1345–53.

Dr. Kulanthaivel and Dr. Jones are in the school of informatics and computing, Purdue University, Indiana University, Indianapolis; Dr. Fogel and Dr. Lammert are in the department of digestive and liver diseases, Indiana University School of Medicine, Indianapolis. This study was supported by KL2TR001106 and UL1TR001108 from the National Institutes of Health, and the Clinical and Translational Sciences Award from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (C.L.). The authors disclose no conflicts.

We are becoming comfortable with the concept of a sharing economy, where resources are shared among many individuals using online forums. Whether activities involve sharing rides (Uber, Lyft, and others), accommodations (Airbnb), or information (social media), underlying attributes include reduced transactional costs, enhanced information transparency, dynamic feedback, and socialization of opportunity. As health care systems realize that they are changing from direct-to-business to a direct-to-customer model, their ability to connect directly with individuals will become a foundational strategy.

This month’s column introduces us to social media as a research tool. Information derived from social media sites can be harvested for critical clinical information (the Centers for Disease and Control and Prevention tracks the spread of influenza using social media analytic tools), research data (patient preferences), and as a recruitment method for clinical studies. Kulanthaivel and colleagues have described their experiences and literature review to help us imagine new ways to collect data at markedly reduced transaction costs (compared to a formal clinical trial). While there are many cautions about the use of social media in your practice or research, we are only beginning to understand its potential.

John I. Allen, MD, MBA, AGAF

Editor in Chief

Medical knowledge, culminating from the collection and translation of patient data, is the primary objective of the clinical research paradigm. The successful conduct of this traditional model has become even more challenging with expansion of costs and a dwindling research infrastructure. Beyond systemic issues, conventional research methods are burdened further by minimal patient engagement, inadequate staffing, and geographic limitations to recruitment. Clinical research also has failed to keep pace with patient demands, and the limited scope of well-funded, disease-specific investigations have left many patients feeling disenfranchised. Social media venues may represent a viable option to surpass these current and evolving barriers when used as an adjunctive approach to traditional clinical investigation.

Advantages and pitfalls in social media research

SM is a new frontier containing a wide spectrum of clinical and qualitative data from connected users (patients). Collection and examination of either individuals’ or groups’ SM information use can provide insight into qualitative life experiences, just as analysis of biologic samples can enable dissection of genetic disease underpinnings. This mediome is analogous to the human genome, both in content and utility.1 Analyzing data streams from SM for interpersonal interactions, message content, and even frequency can provide digital investigators with volumes of information that otherwise would remain unattainable.

Several limitations and potential risks of SM for medical research should be addressed, including the possible compromise of privacy and confidentiality, the use and dissemination of medical advice and information, potential demographic biases, and a required trust of the investigator by patients. Many of these challenges can be similar to traditional methods, however, as in the conventional model, careful management can drastically reduce unwanted study issues.

The risk of Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act violations must be considered seriously in the context of patient–researcher interactions on SM. Because of the relatively public nature of these venues, patient confidentiality may be at risk if patients choose to divulge personal medical information. However, if proper protective measures are taken to ensure that the venue is secure (e.g., a private or closed group on Facebook or a by-invitation-only online Internet forum), and the researcher vets all patients who request entrance into the group, this risk may be minimized. Moreover, to further reduce any legal liability, the researcher should not provide any medical advice to patients who participate in a SM study. The drive to provide medical direction in study patients with clinical need may be strong because collaborative relationships between investigator and patients are likely to form. Furthermore, digital access to investigators on SM commonly becomes easy for patients. Safe approaches to communication could include redirecting patients to consult with their own doctor for advice, unbiased dissemination of disease-specific educational materials, or depiction of only institutional review board–approved study materials.7,8

The perception that only younger populations use SM may appear to be a significant limitation for its implementation in clinical research. However, this limitation is rapidly becoming less significant because recent studies have shown that the use of SM has become increasingly common among older adults. As of 2014, more than half of the US adult population used Facebook, including 73% and 63% of Internet-using adults ages 30–49 and 50–64 years, respectively.10 SM may not be suitable for all diseases, however, there is likely significant demographic overlap for many disease populations.

Finally, it is imperative for researchers to gain the trust of patients on SM to effectively use these venues for research purposes. Because patient–researcher interaction does not occur face-to-face on these platforms, gaining the trust of patients may be more difficult than it would be in a clinical setting. Thus, patient–patient and patient–researcher communications within SM platforms must be cultivated carefully to instill participant confidence in the research being performed on their behalf. One of the authors (C.L.) has established an SM educational model for this exchange.4 Specifically, he provides patients with a distillation of current field research by posting updates in a research-specific Facebook group and on Twitter. This model not only empowers patients with disease education, it also solidifies the importance of patient investment in disease-specific research. Furthermore, invested patients bring ideas to research, take a more educated and proactive role in their care team, and, ultimately, return to seek more study involvement.

Social media in rare disease research

Rare diseases (conditions with a prevalence of less than 200,000 patients in North America), in particular, are prime for high-yield results and community impact using novel SM approaches. This is the result of established digital support groups, publications with historically low study numbers, and few focused investigators. Several studies of rare diseases have shown considerable advantages of using SM as a study tool. For instance, an existing neuroendocrine cervical cancer Facebook support group recently was used to recruit a geographically widespread cohort of patients with this rare cancer. Through an online survey posted in the Facebook group, patients were able to provide specific information on their treatment, disease, and symptom history, current disease status, and quality of life, including various psychological factors. Without the use of SM, collecting this information would have been virtually impossible because the patients were treated at 51 cancer centers across the country.14

Currently, the use of SM in hepatology research, focused specifically on autoimmune hepatitis (AIH), is under exploration at Indiana University. AIH is a rare autoimmune liver disease that results in immune-mediated destruction of liver cells, possibly resulting in fibrosis, cirrhosis, or liver failure if treatment is unsuccessful. One of the authors (C.L.) used both Facebook and Twitter to construct a large study group of individuals affected with AIH called the Autoimmune Hepatitis Research Network (AHRN; 1,500 members) during the past 2 years.4 Interested individuals have joined this research group after searching for AIH online support groups or reading shared AHRN posts on other media platforms. Between April 2015 and April 2016, there were posts by more than 750 unique active members (more than 50% of the group contributes to discussions), most of whom appear to be either caregivers of AIH patients or AIH patients themselves.

Preliminary informational analysis on this group has shown that C.L. and study collaborators have been able to uncover rich clinical and nonclinical information that otherwise would remain unknown. This research was performed by semi-automated download of the Facebook group’s content and subsequent semantic analysis. Qualitative analysis also was performed by direct reading of patient narratives. Collected clinical information has included histories of medication side effects, familial autoimmune diseases, and comorbid conditions. The most common factors that patients were unlikely to discuss with a provider (e.g., financial issues, employment, personal relationships, use of supplements, and alcohol use) frequently were discussed in the AHRN group, allowing a more transparent view of the complete disease experience.

Beyond research conducted in the current paradigm, the AHRN has provided a rich community construct in which patients offer each other social support. The patient impression of AHRN on Facebook has been overwhelmingly positive, and patients often wonder why such a model has not been used with other diseases. The close digital interaction the author (C.L.) has had with numerous patients and families has promoted other benefits of this methodology: more than 40 new AIH patients from outside Indiana have traveled to Indiana University for medical consultation despite no advertisement.

Conclusions

SM has the potential to transform health care research as a supplement to traditional research methods. Compared with a conventional research model, this methodology has proven to be cost and time effective, wide reaching, and similarly capable of data collection. Use of SM in research has tremendous potential to direct patient-centered research because invested patient collaborators can take an active role in their own disease and may hone investigatory focus on stakeholder priorities. Limitations to this method are known, however; if implemented cautiously, these can be mitigated. Investment in and application of the social mediome by investigators and patients has the potential to support and transform research that otherwise would be impossible.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to extend their gratitude to the members of the Autoimmune Hepatitis Research Network for their continued proactivity and engagement in autoimmune hepatitis research. Furthermore, the authors are grateful to Dr. Naga Chalasani for his continued mentorship and extensive contributions to the development of social media approaches in clinical investigation.

References

1. Asch, D.A., Rader, D.J., Merchant, R.M. Mining the social mediome. Trends Mol Med. 2015;21:528-9.

2. Brotherton, C.S., Martin, C.A., Long, M.D. et al. Avoidance of fiber is associated with greater risk of Crohn’s disease flare in a 6-month period. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;14:1130-6.

3. Fenner, Y., Garland, S.M., Moore, E.E., et al. Web-based recruiting for health research using a social networking site: an exploratory study. J Med Internet Res. 2012;14:e20.

4. Lammert, C., Comerford, M., Love, J., et al. Investigation gone viral: application of the social mediasphere in research. Gastroenterology. 2015;149:839-43.

5. Wicks, P., Massagli, M., Frost, J., et al. Sharing health data for better outcomes on PatientsLikeMe. J Med Internet Res. 2010;12:e19.

6. Admon, L., Haefner, J.K., Kolenic, G.E., et al. Recruiting pregnant patients for survey research: a head to head comparison of social media-based versus clinic-based approaches. J Med Internet Res. 2016;18:e326.

7. Farnan, J.M., Sulmasy, L.S., Chaudhry, H. Online medical professionalism. Ann Intern Med. 2013;159:158-9.

8. Massachusetts Medical Society: Social Media Guidelines for Physicians. Available from: http://www.massmed.org/Physicians/Legal-and-Regulatory/Social-Media-Guidelines-for-Physicians/#. Accessed: January 3, 2017.

9. Pirraglia, P.A. Kravitz, R.L. Social media: new opportunities, new ethical concerns. J Gen Intern Med. 2013;28:165-6.

10. Duggan, M., Ellison, N.B., Lampe, C. et al. Demographics of key social networking platforms. (Available from:) (Accessed: January 4, 2017) Pew Res Cent Internet Sci Tech. 2015; http://www.pewinternet.org/2015/01/09/demographics-of-key-social-networking-platforms-2

11. Kang, X., Zhao, L., Leung, F., et al. Delivery of Instructions via mobile social media app increases quality of bowel preparation. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;14:429-35.

12. Bajaj, J.S., Heuman, D.M., Sterling, R.K., et al. Validation of EncephalApp, Smartphone-based Stroop test, for the diagnosis of covert hepatic encephalopathy. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;13:1828-35.

13. Riaz, M.S. Atreja, A. Personalized technologies in chronic gastrointestinal disorders: self-monitoring and remote sensor technologies. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;14:1697-705.

14. Zaid, T., Burzawa, J., Basen-Engquist, K., et al. Use of social media to conduct a cross-sectional epidemiologic and quality of life survey of patients with neuroendocrine carcinoma of the cervix: a feasibility study. Gynecol Oncol. 2014;132:149-53.

15. Schumacher, K.R., Stringer, K.A., Donohue, J.E., et al. Social media methods for studying rare diseases. Pediatrics. 2014;133:e1345–53.

Dr. Kulanthaivel and Dr. Jones are in the school of informatics and computing, Purdue University, Indiana University, Indianapolis; Dr. Fogel and Dr. Lammert are in the department of digestive and liver diseases, Indiana University School of Medicine, Indianapolis. This study was supported by KL2TR001106 and UL1TR001108 from the National Institutes of Health, and the Clinical and Translational Sciences Award from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (C.L.). The authors disclose no conflicts.