User login

Mental illness during pregnancy

Young, pregnant, ataxic—and jilted

CASE Difficulty walking

Ms. M, age 15, is a pregnant, Spanish-speaking Guatemalan woman who is brought to obstetrics triage in a large academic medical center at 35 weeks gestational age. She complains of dizziness, tinnitus, left orbital headache, and difficulty walking.

The neurology service finds profound truncal ataxia, astasia-abasia, and buckling of the knees; a normal brain and spine MRI are not consistent with a neurologic etiology. Otolaryngology service evaluates Ms. M to rule out a cholesteatoma and suggests a head CT and endoscopy, which are normal.

Ms. M’s symptoms resolve after 3 days, although the gait disturbances persist. When no clear cause is found for her difficulty walking, the psychiatry service is consulted to evaluate whether an underlying psychiatric disorder is contributing to symptoms.

What could be causing Ms. M’s symptoms?

a) malingering

b) factitious disorder

c) undiagnosed neurologic disorder

d) conversion disorder

The authors’ observations

Women are vulnerable to a variety of psychiatric illnesses during pregnancy1 that have deleterious effects on mother, baby, and family.2-6 Although there is a burgeoning literature on affective and anxiety disorders occurring in pregnancy, there is a dearth of information about somatoform disorders.

HISTORY Abandonment

Ms. M reports that, although her boyfriend deserted her after learning about the unexpected pregnancy, she will welcome the baby and looks forward to motherhood. She seems unaware of the responsibilities of being a mother.

Ms. M acknowledges a history of depression and self-harm a few years earlier, yet says she feels better now and thinks that psychiatric care is unnecessary. Because she does not endorse a history of trauma or symptoms suggesting an affective, anxiety, or psychotic illness, the psychiatrist does not recommend treatment with psychotropic medication.

At age 5, Ms. M’s parents sent her to the United States with her aunt, hoping that she would have a better life than she would have had in Guatemala. Her aunt reports that Ms. M initially had difficulty adjusting to life in the United States without her parents, yet she has made substantial strides over the years and is now quite accustomed to the country. Her aunt describes Ms. M as an independent high school student who earns good grades.

During the interview, the psychiatrist observes that Ms. M exhibits childlike mannerisms, including sleeping with stuffed toys and coloring in Disney books with crayons. She also is indifferent to her gait difficulty, pregnancy, and psychosocial stressors. Her affect is inconsistent with the content of her speech and she is alexithymic.

Ms. M’s aunt reports that her niece is becoming more dependent on her, which is not consistent with her baseline. Her aunt also notes that several years earlier, Ms. M’s nephew was diagnosed with a cholesteatoma after he presented with similar symptoms.

The combination of (1) Ms. M’s clinical presentation, which was causing her significant impairment in her social functioning, (2) the incompatibility of symptoms with any recognized neurologic and medical disease, and (3) prior family experience with cholesteatoma leads the consulting psychiatrist to suspect conversion disorder. Ms. M’s alexithymia, indifference to her symptoms, and recent abandonment by the baby’s father also support a conversion disorder diagnosis.

From a psychodynamic perspective, the ataxia appears to be her way of protecting herself from the abandonment she is experiencing by being left again to “stand alone” by her boyfriend as she had been when her parents sent her to the United States. Her regressive behavior could be her way of securing her aunt’s love and support.

The authors’ observations

This is the first case of psychogenic gait disturbance during pregnancy described in the literature. Authors have reported on pseudotoxemia,7 hyperemesis gravidarum,8 and pesudocyesis,9 yet there is a paucity of information on psychogenic gait disturbance during pregnancy. Ms. M’s case elucidates many of the clinical quandaries that occur when managing psychiatric illness—and, more specifically, conversion disorder— during pregnancy. Many women are hesitant to seek psychiatric treatment during pregnancy because of shame, stigma, and fear of loss of personal or parental rights10,11; it is not surprising that emotionally distressed women communicate their feelings or troubled thoughts through physical symptoms.

Likely diagnosis

Conversion disorder is the presence of neurologic symptoms in the absence of a neurologic diagnosis that fully explains those symptoms. Conversion disorder, previously known as hysteria, is called functional neurologic symptom disorder in DSM-5 (Box).12 Symptoms are not feigned; instead, they represent “conversion” of emotional distress into neurologic symptoms.13,14 Although misdiagnosing conversion disorder in patients with true neurologic disease is uncommon, clinicians often are uncomfortable making the diagnosis until all medical causes have been ruled out.14 It is not always possible to find a psychological explanation for conversion disorder, but a history of childhood abuse, particularly sexual abuse, could play a role.14

Because of the variety of presentations, clinicians in all specialties should be familiar with somatoform disorders; this is especially important in obstetrics and gynecology because women are more likely than men to develop these disorders.15 It is important to consider that Ms. M is a teenager and somatoform disorders can present differently in adults. The diagnostic process should include a diligent somatic workup and a personal and social history to identify the patient’s developmental tasks, stressors, and coping style.15

How would you treat Ms. M?

a) destigmatize psychiatric illness and provide psychoeducation regarding treatment benefits

b) identify and treat any comorbid psychiatric disorders

c) maintain a proactive and multidisciplinary approach that includes assessment of psychosocial stressors and psychodynamic factors, particularly those related to the pregnancy

d) all of the above

TREATMENT Close follow-up

The psychiatrist recommends continued close psychiatric follow-up as well as multidisciplinary involvement, including physical therapy, neurology, and obstetrics.

Ms. M initially is resistant to psychiatric follow-up because she says that “people on the street” told her that, if she saw a psychiatrist, her baby would be taken away. After the psychiatrist explains that it is unlikely her baby would be taken away, Ms. M immediately appears relieved, smiles, and readily agrees to outpatient psychotherapy.

Over the next 24 hours, she continues to work with a physical therapist and her gait significantly improves. She is discharged home 2 days later with a walking aid (Zimmer frame) for assistance.

Four days later, however, Ms. M is readmitted with worsening ataxia. Her aunt reports that, at home, Ms. M’s regressed behaviors are worsening; she is sleeping in bed with her and had several episodes of enuresis at home.

Ms. M continues to deny psychiatric symptoms or anxiety about the delivery. Although she shows some improvement when working with physical therapists, they note that Ms. M is still unable to ambulate or stand on her own. The psychiatrist is increasingly concerned about her regressed behavior and continued ataxia.

A family meeting is held and the psychiatrist and social worker educate Ms. M and her aunt about conversion disorder, including how some emotionally distressed women communicate their feelings or troubled thoughts through physical symptoms and how that may apply to Ms. M. During the meeting, the team also destigmatizes psychiatric illness and treatment and provides psychoeducation regarding its benefits. The psychiatrist and social worker also provide a psychodynamic interpretation that her ataxia could be a way of protecting herself against the abandonment she is experiencing by being left to “stand alone” by her boyfriend— as she had been when her parents sent her to the United States, and that her behavior could be her way of securing her aunt’s love and support.Ms. M and her aunt both readily agree with this interpretation. The aunt notes that her niece is more anxious about motherhood than she acknowledges and is concerned that Ms. M expects her to be the primary caregiver for the baby. Those present note that Ms. M is becoming increasingly dependent on her aunt, and that it is important for her to retain her independence, especially once she becomes a mother.

Ms. M immediately begins to display more affect; she smiles and reports feeling relieved. Similar to the previous admission, her gait significantly improves over the next 2 days and she is discharged home with a walking aid.

The authors’ observations

A broad differential diagnosis and early multidisciplinary involvement might facilitate earlier diagnosis and treatment.16 Assessment of psychosocial stressors in the patient’s personal and family life, including circumstances around the pregnancy and the meaning of motherhood, as well as investigation of what the patient may gain from the sick role, are paramount. In Ms. M’s case, cultural background, separation from her parents at a young age, and recent abandonment by her boyfriend have contributed to her inability to “stand alone,” which manifested as ataxia. Young age, regressed behavior, and her minimization of stressors also point to her difficulty acknowledging and coping with psychosocial stressors.

Successful delivery of the diagnosis is key to treatment success. After building a therapeutic alliance, a multidisciplinary discussion should take place that allows the patient to understand the diagnosis and treatment plan.17,18 The patient and family should be reassured that the fetus is healthy and all organic causes of symptoms have been investigated.17 Although management of conversion disorder during pregnancy is similar to that in non-pregnant women, several additional avenues of investigation should be considered:

• Explore the psychodynamic basis of the disorder and the role of the pregnancy and motherhood.

• Identify any comorbid psychiatric disorders, particularly those specific to pregnancy or the postpartum period.

• Because of the shame and stigma associated with seeking psychiatric treatment during pregnancy,10,11 it is imperative to destigmatize treatment and provide psychoeducation regarding its benefits.

A treatment plan can then be developed that involves psychotherapy, psychoeducation, stress management, and, when appropriate, pharmacotherapy.17

Providing psychoeducation about postpartum depression and other perinatal psychiatric illness could be beneficial. Physical therapy often is culturally acceptable and can help re-establish healthy patterns of motor function.19 Ms. M’s gait showed some improvement with physical therapy as part of the multidisciplinary approach, which also should include a thorough medical workup. Appropriate psychiatric treatment can help patients give up the sick role and return to their previous level of functioning.17

Maintain close communication with the outpatient perinatal care team as they monitor the patient’s parenting capacity. The outpatient perinatal care team also should engage pregnant or postpartum women in prioritizing their emotional well-being and encourage outpatient mental health treatment. Despite a dearth of data on the regressive symptoms and prognosis for future pregnancies, it is important to monitor maternal capacity and discuss the possibility of symptom recurrence.

OUTCOME Healthy baby

Three days later, Ms. M returns in labor with improved gait yet still using a walking aid. She has a normal vaginal delivery of a healthy baby boy at 37 weeks’ gestational age.

After the birth, Ms. M reports feeling well and enjoying motherhood, and denies psychiatric symptoms. She is ambulating without assistance within hours of delivery. This spontaneous resolution of symptoms could have been because of the psychodynamically oriented multidisciplinary approach to her care, which may have helped her realize that she did not have to “stand alone” as she embarked on motherhood.

Before being discharged home, Ms. M and her aunt meet with the inpatient obstetric social worker to assess Ms. M’s ability to care for the baby and discuss the importance of continued emotional support. The social worker does not contact the Department of Children and Families because Ms. M is walking independently and not endorsing or exhibiting regressive behaviors. Ms. M also reports that she will ask her aunt to take care of the baby should ataxia recur. Her aunt reassures the social workers that she will encourage Ms. M to attend outpatient psychotherapy and will contact the social worker if she becomes concerned about Ms. M’s or the baby’s well-being.

During her postpartum obstetric visit, Ms. M is walking independently and does not exhibit or endorse neurologic symptoms. The social worker provides psychoeducation about the importance of outpatient psychotherapy and schedules an initial appointment; Ms. M does not attend outpatient psychotherapy after discharge.

Bottom Line

Consider conversion disorder in obstetric patients who present with ataxia without a neurologic cause. Management involves a proactive and multidisciplinary approach that includes a thorough medical workup and assessment of psychosocial stressors and psychodynamic factors, particularly those related to the pregnancy. Early identification and delivery of the diagnosis, destigmatization, and provision of appropriate psychiatric treatment can facilitate treatment success.

Disclosures

Dr. Byatt has received grant funding/support for this project from the National Center for Research Resources and the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, National Institutes of Health, through Grant KL2TR000160. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH. Dr. Toor reports no financial relationships with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or manufacturers of competing products.

1. Vesga-Lopez O, Blanco C, Keyes K, et al. Psychiatric disorders in pregnant and postpartum women in the United States. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2008;65(7):805-815.

2. Britton HL, Gronwaldt V, Britton JR. Maternal postpartum behaviors and mother-infant relationship during the first year of life. J Pediatr. 2001;138(6):905-909.

3. Deave T, Heron J, Evans J, et al. The impact of maternal depression in pregnancy on early child development. BJOG. 2008;115(8):1043-1051.

4. Paulson JF, Keefe HA, Leiferman JA. Early parental depression and child language development. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2009;50(3):254-262.

5. Zuckerman B, Amaro H, Bauchner H, et al. Depressive symptoms during pregnancy: relationship to poor health behaviors. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1989;160(5 pt 1):1107-1111.

6. Forman DR, O’Hara MW, Stuart S, et al. Effective treatment for postpartum depression is not sufficient to improve the developing mother-child relationship. Dev Psychopathol. 2007;19(2):585-602.

7. Brady WJ Jr, Huff JS. Pseudotoxemia: new onset psychogenic seizure in third trimester pregnancy. J Emerg Med. 1997;15(6):815-820.

8. el-Mallakh RS, Liebowitz NR, Hale MS. Hyperemesis gravidarum as conversion disorder. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1990; 178(10):655-659.

9. Paulman PM, Sadat A. Pseudocyesis. J Fam Pract. 1990;30(5):575-576.

10. Dennis CL, Chung-Lee L. Postpartum depression help-seeking barriers and maternal treatment p: a qualitative systematic review. Birth. 2006;33(4):323-331.

11. Byatt N, Simas TA, Lundquist RS, et al. Strategies for improving perinatal depression treatment in North American outpatient obstetric settings. J Psychosom Obstetr Gynaecol. 2012;33(4):143-161.

12. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 5th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

13. Feinstein A. Conversion disorder: advances in our understanding. CMAJ. 2011;183(8):915-920.

14. Nicholson TR, Stone J, Kanaan RA. Conversion disorder: a problematic diagnosis. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2011;82(11):1267-1273.

15. Bitzer J. Somatization disorders in obstetrics and gynecology. Arch Womens Mental health, 2003;6(2):99-107.

16. Smith HE, Rynning RE, Okafor C, et al. Evaluation of neurologic deficit without apparent cause: the importance of a multidisciplinary approach. J Spinal Cord Med. 2007;30(5):509-517.

17. Hinson VK, Haren WB. Psychogenic movement disorders. Lancet Neurol. 2006;5(8):695-700.

18. Oyama O, Paltoo C, Greengold J. Somatoform disorders. Am Fam Physician. 2007;76(9):1333-1338.

19. Ness D. Physical therapy management for conversion disorder: case series. J Neurol Phys Ther. 2007;31(1):30-39.

CASE Difficulty walking

Ms. M, age 15, is a pregnant, Spanish-speaking Guatemalan woman who is brought to obstetrics triage in a large academic medical center at 35 weeks gestational age. She complains of dizziness, tinnitus, left orbital headache, and difficulty walking.

The neurology service finds profound truncal ataxia, astasia-abasia, and buckling of the knees; a normal brain and spine MRI are not consistent with a neurologic etiology. Otolaryngology service evaluates Ms. M to rule out a cholesteatoma and suggests a head CT and endoscopy, which are normal.

Ms. M’s symptoms resolve after 3 days, although the gait disturbances persist. When no clear cause is found for her difficulty walking, the psychiatry service is consulted to evaluate whether an underlying psychiatric disorder is contributing to symptoms.

What could be causing Ms. M’s symptoms?

a) malingering

b) factitious disorder

c) undiagnosed neurologic disorder

d) conversion disorder

The authors’ observations

Women are vulnerable to a variety of psychiatric illnesses during pregnancy1 that have deleterious effects on mother, baby, and family.2-6 Although there is a burgeoning literature on affective and anxiety disorders occurring in pregnancy, there is a dearth of information about somatoform disorders.

HISTORY Abandonment

Ms. M reports that, although her boyfriend deserted her after learning about the unexpected pregnancy, she will welcome the baby and looks forward to motherhood. She seems unaware of the responsibilities of being a mother.

Ms. M acknowledges a history of depression and self-harm a few years earlier, yet says she feels better now and thinks that psychiatric care is unnecessary. Because she does not endorse a history of trauma or symptoms suggesting an affective, anxiety, or psychotic illness, the psychiatrist does not recommend treatment with psychotropic medication.

At age 5, Ms. M’s parents sent her to the United States with her aunt, hoping that she would have a better life than she would have had in Guatemala. Her aunt reports that Ms. M initially had difficulty adjusting to life in the United States without her parents, yet she has made substantial strides over the years and is now quite accustomed to the country. Her aunt describes Ms. M as an independent high school student who earns good grades.

During the interview, the psychiatrist observes that Ms. M exhibits childlike mannerisms, including sleeping with stuffed toys and coloring in Disney books with crayons. She also is indifferent to her gait difficulty, pregnancy, and psychosocial stressors. Her affect is inconsistent with the content of her speech and she is alexithymic.

Ms. M’s aunt reports that her niece is becoming more dependent on her, which is not consistent with her baseline. Her aunt also notes that several years earlier, Ms. M’s nephew was diagnosed with a cholesteatoma after he presented with similar symptoms.

The combination of (1) Ms. M’s clinical presentation, which was causing her significant impairment in her social functioning, (2) the incompatibility of symptoms with any recognized neurologic and medical disease, and (3) prior family experience with cholesteatoma leads the consulting psychiatrist to suspect conversion disorder. Ms. M’s alexithymia, indifference to her symptoms, and recent abandonment by the baby’s father also support a conversion disorder diagnosis.

From a psychodynamic perspective, the ataxia appears to be her way of protecting herself from the abandonment she is experiencing by being left again to “stand alone” by her boyfriend as she had been when her parents sent her to the United States. Her regressive behavior could be her way of securing her aunt’s love and support.

The authors’ observations

This is the first case of psychogenic gait disturbance during pregnancy described in the literature. Authors have reported on pseudotoxemia,7 hyperemesis gravidarum,8 and pesudocyesis,9 yet there is a paucity of information on psychogenic gait disturbance during pregnancy. Ms. M’s case elucidates many of the clinical quandaries that occur when managing psychiatric illness—and, more specifically, conversion disorder— during pregnancy. Many women are hesitant to seek psychiatric treatment during pregnancy because of shame, stigma, and fear of loss of personal or parental rights10,11; it is not surprising that emotionally distressed women communicate their feelings or troubled thoughts through physical symptoms.

Likely diagnosis

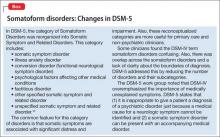

Conversion disorder is the presence of neurologic symptoms in the absence of a neurologic diagnosis that fully explains those symptoms. Conversion disorder, previously known as hysteria, is called functional neurologic symptom disorder in DSM-5 (Box).12 Symptoms are not feigned; instead, they represent “conversion” of emotional distress into neurologic symptoms.13,14 Although misdiagnosing conversion disorder in patients with true neurologic disease is uncommon, clinicians often are uncomfortable making the diagnosis until all medical causes have been ruled out.14 It is not always possible to find a psychological explanation for conversion disorder, but a history of childhood abuse, particularly sexual abuse, could play a role.14

Because of the variety of presentations, clinicians in all specialties should be familiar with somatoform disorders; this is especially important in obstetrics and gynecology because women are more likely than men to develop these disorders.15 It is important to consider that Ms. M is a teenager and somatoform disorders can present differently in adults. The diagnostic process should include a diligent somatic workup and a personal and social history to identify the patient’s developmental tasks, stressors, and coping style.15

How would you treat Ms. M?

a) destigmatize psychiatric illness and provide psychoeducation regarding treatment benefits

b) identify and treat any comorbid psychiatric disorders

c) maintain a proactive and multidisciplinary approach that includes assessment of psychosocial stressors and psychodynamic factors, particularly those related to the pregnancy

d) all of the above

TREATMENT Close follow-up

The psychiatrist recommends continued close psychiatric follow-up as well as multidisciplinary involvement, including physical therapy, neurology, and obstetrics.

Ms. M initially is resistant to psychiatric follow-up because she says that “people on the street” told her that, if she saw a psychiatrist, her baby would be taken away. After the psychiatrist explains that it is unlikely her baby would be taken away, Ms. M immediately appears relieved, smiles, and readily agrees to outpatient psychotherapy.

Over the next 24 hours, she continues to work with a physical therapist and her gait significantly improves. She is discharged home 2 days later with a walking aid (Zimmer frame) for assistance.

Four days later, however, Ms. M is readmitted with worsening ataxia. Her aunt reports that, at home, Ms. M’s regressed behaviors are worsening; she is sleeping in bed with her and had several episodes of enuresis at home.

Ms. M continues to deny psychiatric symptoms or anxiety about the delivery. Although she shows some improvement when working with physical therapists, they note that Ms. M is still unable to ambulate or stand on her own. The psychiatrist is increasingly concerned about her regressed behavior and continued ataxia.

A family meeting is held and the psychiatrist and social worker educate Ms. M and her aunt about conversion disorder, including how some emotionally distressed women communicate their feelings or troubled thoughts through physical symptoms and how that may apply to Ms. M. During the meeting, the team also destigmatizes psychiatric illness and treatment and provides psychoeducation regarding its benefits. The psychiatrist and social worker also provide a psychodynamic interpretation that her ataxia could be a way of protecting herself against the abandonment she is experiencing by being left to “stand alone” by her boyfriend— as she had been when her parents sent her to the United States, and that her behavior could be her way of securing her aunt’s love and support.Ms. M and her aunt both readily agree with this interpretation. The aunt notes that her niece is more anxious about motherhood than she acknowledges and is concerned that Ms. M expects her to be the primary caregiver for the baby. Those present note that Ms. M is becoming increasingly dependent on her aunt, and that it is important for her to retain her independence, especially once she becomes a mother.

Ms. M immediately begins to display more affect; she smiles and reports feeling relieved. Similar to the previous admission, her gait significantly improves over the next 2 days and she is discharged home with a walking aid.

The authors’ observations

A broad differential diagnosis and early multidisciplinary involvement might facilitate earlier diagnosis and treatment.16 Assessment of psychosocial stressors in the patient’s personal and family life, including circumstances around the pregnancy and the meaning of motherhood, as well as investigation of what the patient may gain from the sick role, are paramount. In Ms. M’s case, cultural background, separation from her parents at a young age, and recent abandonment by her boyfriend have contributed to her inability to “stand alone,” which manifested as ataxia. Young age, regressed behavior, and her minimization of stressors also point to her difficulty acknowledging and coping with psychosocial stressors.

Successful delivery of the diagnosis is key to treatment success. After building a therapeutic alliance, a multidisciplinary discussion should take place that allows the patient to understand the diagnosis and treatment plan.17,18 The patient and family should be reassured that the fetus is healthy and all organic causes of symptoms have been investigated.17 Although management of conversion disorder during pregnancy is similar to that in non-pregnant women, several additional avenues of investigation should be considered:

• Explore the psychodynamic basis of the disorder and the role of the pregnancy and motherhood.

• Identify any comorbid psychiatric disorders, particularly those specific to pregnancy or the postpartum period.

• Because of the shame and stigma associated with seeking psychiatric treatment during pregnancy,10,11 it is imperative to destigmatize treatment and provide psychoeducation regarding its benefits.

A treatment plan can then be developed that involves psychotherapy, psychoeducation, stress management, and, when appropriate, pharmacotherapy.17

Providing psychoeducation about postpartum depression and other perinatal psychiatric illness could be beneficial. Physical therapy often is culturally acceptable and can help re-establish healthy patterns of motor function.19 Ms. M’s gait showed some improvement with physical therapy as part of the multidisciplinary approach, which also should include a thorough medical workup. Appropriate psychiatric treatment can help patients give up the sick role and return to their previous level of functioning.17

Maintain close communication with the outpatient perinatal care team as they monitor the patient’s parenting capacity. The outpatient perinatal care team also should engage pregnant or postpartum women in prioritizing their emotional well-being and encourage outpatient mental health treatment. Despite a dearth of data on the regressive symptoms and prognosis for future pregnancies, it is important to monitor maternal capacity and discuss the possibility of symptom recurrence.

OUTCOME Healthy baby

Three days later, Ms. M returns in labor with improved gait yet still using a walking aid. She has a normal vaginal delivery of a healthy baby boy at 37 weeks’ gestational age.

After the birth, Ms. M reports feeling well and enjoying motherhood, and denies psychiatric symptoms. She is ambulating without assistance within hours of delivery. This spontaneous resolution of symptoms could have been because of the psychodynamically oriented multidisciplinary approach to her care, which may have helped her realize that she did not have to “stand alone” as she embarked on motherhood.

Before being discharged home, Ms. M and her aunt meet with the inpatient obstetric social worker to assess Ms. M’s ability to care for the baby and discuss the importance of continued emotional support. The social worker does not contact the Department of Children and Families because Ms. M is walking independently and not endorsing or exhibiting regressive behaviors. Ms. M also reports that she will ask her aunt to take care of the baby should ataxia recur. Her aunt reassures the social workers that she will encourage Ms. M to attend outpatient psychotherapy and will contact the social worker if she becomes concerned about Ms. M’s or the baby’s well-being.

During her postpartum obstetric visit, Ms. M is walking independently and does not exhibit or endorse neurologic symptoms. The social worker provides psychoeducation about the importance of outpatient psychotherapy and schedules an initial appointment; Ms. M does not attend outpatient psychotherapy after discharge.

Bottom Line

Consider conversion disorder in obstetric patients who present with ataxia without a neurologic cause. Management involves a proactive and multidisciplinary approach that includes a thorough medical workup and assessment of psychosocial stressors and psychodynamic factors, particularly those related to the pregnancy. Early identification and delivery of the diagnosis, destigmatization, and provision of appropriate psychiatric treatment can facilitate treatment success.

Disclosures

Dr. Byatt has received grant funding/support for this project from the National Center for Research Resources and the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, National Institutes of Health, through Grant KL2TR000160. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH. Dr. Toor reports no financial relationships with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or manufacturers of competing products.

CASE Difficulty walking

Ms. M, age 15, is a pregnant, Spanish-speaking Guatemalan woman who is brought to obstetrics triage in a large academic medical center at 35 weeks gestational age. She complains of dizziness, tinnitus, left orbital headache, and difficulty walking.

The neurology service finds profound truncal ataxia, astasia-abasia, and buckling of the knees; a normal brain and spine MRI are not consistent with a neurologic etiology. Otolaryngology service evaluates Ms. M to rule out a cholesteatoma and suggests a head CT and endoscopy, which are normal.

Ms. M’s symptoms resolve after 3 days, although the gait disturbances persist. When no clear cause is found for her difficulty walking, the psychiatry service is consulted to evaluate whether an underlying psychiatric disorder is contributing to symptoms.

What could be causing Ms. M’s symptoms?

a) malingering

b) factitious disorder

c) undiagnosed neurologic disorder

d) conversion disorder

The authors’ observations

Women are vulnerable to a variety of psychiatric illnesses during pregnancy1 that have deleterious effects on mother, baby, and family.2-6 Although there is a burgeoning literature on affective and anxiety disorders occurring in pregnancy, there is a dearth of information about somatoform disorders.

HISTORY Abandonment

Ms. M reports that, although her boyfriend deserted her after learning about the unexpected pregnancy, she will welcome the baby and looks forward to motherhood. She seems unaware of the responsibilities of being a mother.

Ms. M acknowledges a history of depression and self-harm a few years earlier, yet says she feels better now and thinks that psychiatric care is unnecessary. Because she does not endorse a history of trauma or symptoms suggesting an affective, anxiety, or psychotic illness, the psychiatrist does not recommend treatment with psychotropic medication.

At age 5, Ms. M’s parents sent her to the United States with her aunt, hoping that she would have a better life than she would have had in Guatemala. Her aunt reports that Ms. M initially had difficulty adjusting to life in the United States without her parents, yet she has made substantial strides over the years and is now quite accustomed to the country. Her aunt describes Ms. M as an independent high school student who earns good grades.

During the interview, the psychiatrist observes that Ms. M exhibits childlike mannerisms, including sleeping with stuffed toys and coloring in Disney books with crayons. She also is indifferent to her gait difficulty, pregnancy, and psychosocial stressors. Her affect is inconsistent with the content of her speech and she is alexithymic.

Ms. M’s aunt reports that her niece is becoming more dependent on her, which is not consistent with her baseline. Her aunt also notes that several years earlier, Ms. M’s nephew was diagnosed with a cholesteatoma after he presented with similar symptoms.

The combination of (1) Ms. M’s clinical presentation, which was causing her significant impairment in her social functioning, (2) the incompatibility of symptoms with any recognized neurologic and medical disease, and (3) prior family experience with cholesteatoma leads the consulting psychiatrist to suspect conversion disorder. Ms. M’s alexithymia, indifference to her symptoms, and recent abandonment by the baby’s father also support a conversion disorder diagnosis.

From a psychodynamic perspective, the ataxia appears to be her way of protecting herself from the abandonment she is experiencing by being left again to “stand alone” by her boyfriend as she had been when her parents sent her to the United States. Her regressive behavior could be her way of securing her aunt’s love and support.

The authors’ observations

This is the first case of psychogenic gait disturbance during pregnancy described in the literature. Authors have reported on pseudotoxemia,7 hyperemesis gravidarum,8 and pesudocyesis,9 yet there is a paucity of information on psychogenic gait disturbance during pregnancy. Ms. M’s case elucidates many of the clinical quandaries that occur when managing psychiatric illness—and, more specifically, conversion disorder— during pregnancy. Many women are hesitant to seek psychiatric treatment during pregnancy because of shame, stigma, and fear of loss of personal or parental rights10,11; it is not surprising that emotionally distressed women communicate their feelings or troubled thoughts through physical symptoms.

Likely diagnosis

Conversion disorder is the presence of neurologic symptoms in the absence of a neurologic diagnosis that fully explains those symptoms. Conversion disorder, previously known as hysteria, is called functional neurologic symptom disorder in DSM-5 (Box).12 Symptoms are not feigned; instead, they represent “conversion” of emotional distress into neurologic symptoms.13,14 Although misdiagnosing conversion disorder in patients with true neurologic disease is uncommon, clinicians often are uncomfortable making the diagnosis until all medical causes have been ruled out.14 It is not always possible to find a psychological explanation for conversion disorder, but a history of childhood abuse, particularly sexual abuse, could play a role.14

Because of the variety of presentations, clinicians in all specialties should be familiar with somatoform disorders; this is especially important in obstetrics and gynecology because women are more likely than men to develop these disorders.15 It is important to consider that Ms. M is a teenager and somatoform disorders can present differently in adults. The diagnostic process should include a diligent somatic workup and a personal and social history to identify the patient’s developmental tasks, stressors, and coping style.15

How would you treat Ms. M?

a) destigmatize psychiatric illness and provide psychoeducation regarding treatment benefits

b) identify and treat any comorbid psychiatric disorders

c) maintain a proactive and multidisciplinary approach that includes assessment of psychosocial stressors and psychodynamic factors, particularly those related to the pregnancy

d) all of the above

TREATMENT Close follow-up

The psychiatrist recommends continued close psychiatric follow-up as well as multidisciplinary involvement, including physical therapy, neurology, and obstetrics.

Ms. M initially is resistant to psychiatric follow-up because she says that “people on the street” told her that, if she saw a psychiatrist, her baby would be taken away. After the psychiatrist explains that it is unlikely her baby would be taken away, Ms. M immediately appears relieved, smiles, and readily agrees to outpatient psychotherapy.

Over the next 24 hours, she continues to work with a physical therapist and her gait significantly improves. She is discharged home 2 days later with a walking aid (Zimmer frame) for assistance.

Four days later, however, Ms. M is readmitted with worsening ataxia. Her aunt reports that, at home, Ms. M’s regressed behaviors are worsening; she is sleeping in bed with her and had several episodes of enuresis at home.

Ms. M continues to deny psychiatric symptoms or anxiety about the delivery. Although she shows some improvement when working with physical therapists, they note that Ms. M is still unable to ambulate or stand on her own. The psychiatrist is increasingly concerned about her regressed behavior and continued ataxia.

A family meeting is held and the psychiatrist and social worker educate Ms. M and her aunt about conversion disorder, including how some emotionally distressed women communicate their feelings or troubled thoughts through physical symptoms and how that may apply to Ms. M. During the meeting, the team also destigmatizes psychiatric illness and treatment and provides psychoeducation regarding its benefits. The psychiatrist and social worker also provide a psychodynamic interpretation that her ataxia could be a way of protecting herself against the abandonment she is experiencing by being left to “stand alone” by her boyfriend— as she had been when her parents sent her to the United States, and that her behavior could be her way of securing her aunt’s love and support.Ms. M and her aunt both readily agree with this interpretation. The aunt notes that her niece is more anxious about motherhood than she acknowledges and is concerned that Ms. M expects her to be the primary caregiver for the baby. Those present note that Ms. M is becoming increasingly dependent on her aunt, and that it is important for her to retain her independence, especially once she becomes a mother.

Ms. M immediately begins to display more affect; she smiles and reports feeling relieved. Similar to the previous admission, her gait significantly improves over the next 2 days and she is discharged home with a walking aid.

The authors’ observations

A broad differential diagnosis and early multidisciplinary involvement might facilitate earlier diagnosis and treatment.16 Assessment of psychosocial stressors in the patient’s personal and family life, including circumstances around the pregnancy and the meaning of motherhood, as well as investigation of what the patient may gain from the sick role, are paramount. In Ms. M’s case, cultural background, separation from her parents at a young age, and recent abandonment by her boyfriend have contributed to her inability to “stand alone,” which manifested as ataxia. Young age, regressed behavior, and her minimization of stressors also point to her difficulty acknowledging and coping with psychosocial stressors.

Successful delivery of the diagnosis is key to treatment success. After building a therapeutic alliance, a multidisciplinary discussion should take place that allows the patient to understand the diagnosis and treatment plan.17,18 The patient and family should be reassured that the fetus is healthy and all organic causes of symptoms have been investigated.17 Although management of conversion disorder during pregnancy is similar to that in non-pregnant women, several additional avenues of investigation should be considered:

• Explore the psychodynamic basis of the disorder and the role of the pregnancy and motherhood.

• Identify any comorbid psychiatric disorders, particularly those specific to pregnancy or the postpartum period.

• Because of the shame and stigma associated with seeking psychiatric treatment during pregnancy,10,11 it is imperative to destigmatize treatment and provide psychoeducation regarding its benefits.

A treatment plan can then be developed that involves psychotherapy, psychoeducation, stress management, and, when appropriate, pharmacotherapy.17

Providing psychoeducation about postpartum depression and other perinatal psychiatric illness could be beneficial. Physical therapy often is culturally acceptable and can help re-establish healthy patterns of motor function.19 Ms. M’s gait showed some improvement with physical therapy as part of the multidisciplinary approach, which also should include a thorough medical workup. Appropriate psychiatric treatment can help patients give up the sick role and return to their previous level of functioning.17

Maintain close communication with the outpatient perinatal care team as they monitor the patient’s parenting capacity. The outpatient perinatal care team also should engage pregnant or postpartum women in prioritizing their emotional well-being and encourage outpatient mental health treatment. Despite a dearth of data on the regressive symptoms and prognosis for future pregnancies, it is important to monitor maternal capacity and discuss the possibility of symptom recurrence.

OUTCOME Healthy baby

Three days later, Ms. M returns in labor with improved gait yet still using a walking aid. She has a normal vaginal delivery of a healthy baby boy at 37 weeks’ gestational age.

After the birth, Ms. M reports feeling well and enjoying motherhood, and denies psychiatric symptoms. She is ambulating without assistance within hours of delivery. This spontaneous resolution of symptoms could have been because of the psychodynamically oriented multidisciplinary approach to her care, which may have helped her realize that she did not have to “stand alone” as she embarked on motherhood.

Before being discharged home, Ms. M and her aunt meet with the inpatient obstetric social worker to assess Ms. M’s ability to care for the baby and discuss the importance of continued emotional support. The social worker does not contact the Department of Children and Families because Ms. M is walking independently and not endorsing or exhibiting regressive behaviors. Ms. M also reports that she will ask her aunt to take care of the baby should ataxia recur. Her aunt reassures the social workers that she will encourage Ms. M to attend outpatient psychotherapy and will contact the social worker if she becomes concerned about Ms. M’s or the baby’s well-being.

During her postpartum obstetric visit, Ms. M is walking independently and does not exhibit or endorse neurologic symptoms. The social worker provides psychoeducation about the importance of outpatient psychotherapy and schedules an initial appointment; Ms. M does not attend outpatient psychotherapy after discharge.

Bottom Line

Consider conversion disorder in obstetric patients who present with ataxia without a neurologic cause. Management involves a proactive and multidisciplinary approach that includes a thorough medical workup and assessment of psychosocial stressors and psychodynamic factors, particularly those related to the pregnancy. Early identification and delivery of the diagnosis, destigmatization, and provision of appropriate psychiatric treatment can facilitate treatment success.

Disclosures

Dr. Byatt has received grant funding/support for this project from the National Center for Research Resources and the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, National Institutes of Health, through Grant KL2TR000160. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH. Dr. Toor reports no financial relationships with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or manufacturers of competing products.

1. Vesga-Lopez O, Blanco C, Keyes K, et al. Psychiatric disorders in pregnant and postpartum women in the United States. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2008;65(7):805-815.

2. Britton HL, Gronwaldt V, Britton JR. Maternal postpartum behaviors and mother-infant relationship during the first year of life. J Pediatr. 2001;138(6):905-909.

3. Deave T, Heron J, Evans J, et al. The impact of maternal depression in pregnancy on early child development. BJOG. 2008;115(8):1043-1051.

4. Paulson JF, Keefe HA, Leiferman JA. Early parental depression and child language development. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2009;50(3):254-262.

5. Zuckerman B, Amaro H, Bauchner H, et al. Depressive symptoms during pregnancy: relationship to poor health behaviors. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1989;160(5 pt 1):1107-1111.

6. Forman DR, O’Hara MW, Stuart S, et al. Effective treatment for postpartum depression is not sufficient to improve the developing mother-child relationship. Dev Psychopathol. 2007;19(2):585-602.

7. Brady WJ Jr, Huff JS. Pseudotoxemia: new onset psychogenic seizure in third trimester pregnancy. J Emerg Med. 1997;15(6):815-820.

8. el-Mallakh RS, Liebowitz NR, Hale MS. Hyperemesis gravidarum as conversion disorder. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1990; 178(10):655-659.

9. Paulman PM, Sadat A. Pseudocyesis. J Fam Pract. 1990;30(5):575-576.

10. Dennis CL, Chung-Lee L. Postpartum depression help-seeking barriers and maternal treatment p: a qualitative systematic review. Birth. 2006;33(4):323-331.

11. Byatt N, Simas TA, Lundquist RS, et al. Strategies for improving perinatal depression treatment in North American outpatient obstetric settings. J Psychosom Obstetr Gynaecol. 2012;33(4):143-161.

12. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 5th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

13. Feinstein A. Conversion disorder: advances in our understanding. CMAJ. 2011;183(8):915-920.

14. Nicholson TR, Stone J, Kanaan RA. Conversion disorder: a problematic diagnosis. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2011;82(11):1267-1273.

15. Bitzer J. Somatization disorders in obstetrics and gynecology. Arch Womens Mental health, 2003;6(2):99-107.

16. Smith HE, Rynning RE, Okafor C, et al. Evaluation of neurologic deficit without apparent cause: the importance of a multidisciplinary approach. J Spinal Cord Med. 2007;30(5):509-517.

17. Hinson VK, Haren WB. Psychogenic movement disorders. Lancet Neurol. 2006;5(8):695-700.

18. Oyama O, Paltoo C, Greengold J. Somatoform disorders. Am Fam Physician. 2007;76(9):1333-1338.

19. Ness D. Physical therapy management for conversion disorder: case series. J Neurol Phys Ther. 2007;31(1):30-39.

1. Vesga-Lopez O, Blanco C, Keyes K, et al. Psychiatric disorders in pregnant and postpartum women in the United States. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2008;65(7):805-815.

2. Britton HL, Gronwaldt V, Britton JR. Maternal postpartum behaviors and mother-infant relationship during the first year of life. J Pediatr. 2001;138(6):905-909.

3. Deave T, Heron J, Evans J, et al. The impact of maternal depression in pregnancy on early child development. BJOG. 2008;115(8):1043-1051.

4. Paulson JF, Keefe HA, Leiferman JA. Early parental depression and child language development. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2009;50(3):254-262.

5. Zuckerman B, Amaro H, Bauchner H, et al. Depressive symptoms during pregnancy: relationship to poor health behaviors. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1989;160(5 pt 1):1107-1111.

6. Forman DR, O’Hara MW, Stuart S, et al. Effective treatment for postpartum depression is not sufficient to improve the developing mother-child relationship. Dev Psychopathol. 2007;19(2):585-602.

7. Brady WJ Jr, Huff JS. Pseudotoxemia: new onset psychogenic seizure in third trimester pregnancy. J Emerg Med. 1997;15(6):815-820.

8. el-Mallakh RS, Liebowitz NR, Hale MS. Hyperemesis gravidarum as conversion disorder. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1990; 178(10):655-659.

9. Paulman PM, Sadat A. Pseudocyesis. J Fam Pract. 1990;30(5):575-576.

10. Dennis CL, Chung-Lee L. Postpartum depression help-seeking barriers and maternal treatment p: a qualitative systematic review. Birth. 2006;33(4):323-331.

11. Byatt N, Simas TA, Lundquist RS, et al. Strategies for improving perinatal depression treatment in North American outpatient obstetric settings. J Psychosom Obstetr Gynaecol. 2012;33(4):143-161.

12. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 5th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

13. Feinstein A. Conversion disorder: advances in our understanding. CMAJ. 2011;183(8):915-920.

14. Nicholson TR, Stone J, Kanaan RA. Conversion disorder: a problematic diagnosis. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2011;82(11):1267-1273.

15. Bitzer J. Somatization disorders in obstetrics and gynecology. Arch Womens Mental health, 2003;6(2):99-107.

16. Smith HE, Rynning RE, Okafor C, et al. Evaluation of neurologic deficit without apparent cause: the importance of a multidisciplinary approach. J Spinal Cord Med. 2007;30(5):509-517.

17. Hinson VK, Haren WB. Psychogenic movement disorders. Lancet Neurol. 2006;5(8):695-700.

18. Oyama O, Paltoo C, Greengold J. Somatoform disorders. Am Fam Physician. 2007;76(9):1333-1338.

19. Ness D. Physical therapy management for conversion disorder: case series. J Neurol Phys Ther. 2007;31(1):30-39.