User login

ACL injury: How do the physical examination tests compare?

CASE An athletic 25-year-old woman presents to her family physician complaining of a painful and swollen knee. She says that she injured the knee the day before during a judo match. The injury occurred when her upper body suddenly changed direction while her foot remained planted and her knee rotated medially. A cruciate ligament injury immediately comes to mind, but other potential diagnoses include meniscal injury, collateral ligament injury, and patellar instability. The first step in determining an accurate diagnosis is to evaluate the stability of the knee by physical examination—often a difficult task immediately following an injury.

How would you proceed?

Rupture of the anterior cruciate ligament (ACL), partial or complete, is a common injury, especially in athletes who hurt their knee in a pivoting movement.1 The number of patients who present with ACL injury is estimated at 252,000 per year.2 Cruciate ligament injury may lead to complaints of instability with subsequent inability to engage in sports activities. Cruciate ligament injury is also associated with premature development of osteoarthritis later in life.3 Operative treatment seems to be superior to conservative treatment in improving both subjective and objective measures of knee instability and in helping athletes return to their former level of activity.4

Because early detection is key to achieving the best clinical outcome, it is essential that the most accurate physical examination tests are performed during the acute phase. Primary care physicians, emergency room doctors, physical therapists, and athletic trainers are the ones who most often see these patients immediately following the injury, and they often have only the physical examination with which to assess ACL injury. Their task is to identify the patient with potential ACL injury and to refer the patient swiftly.

Three physical examination tests are most commonly used to evaluate cruciate ligament injury. The best known and most frequently used technique is the anterior drawer test. The other 2 tests, the Lachman test and the pivot shift test, are more difficult to perform and are used less often, especially by physicians untrained in their use. In addition, there is a relatively new diagnostic test: the lever sign test. The aim of our article is to provide a short, clinically relevant overview of the literature and to assess the diagnostic value of physical examination for the primary care physician.

Anterior drawer test

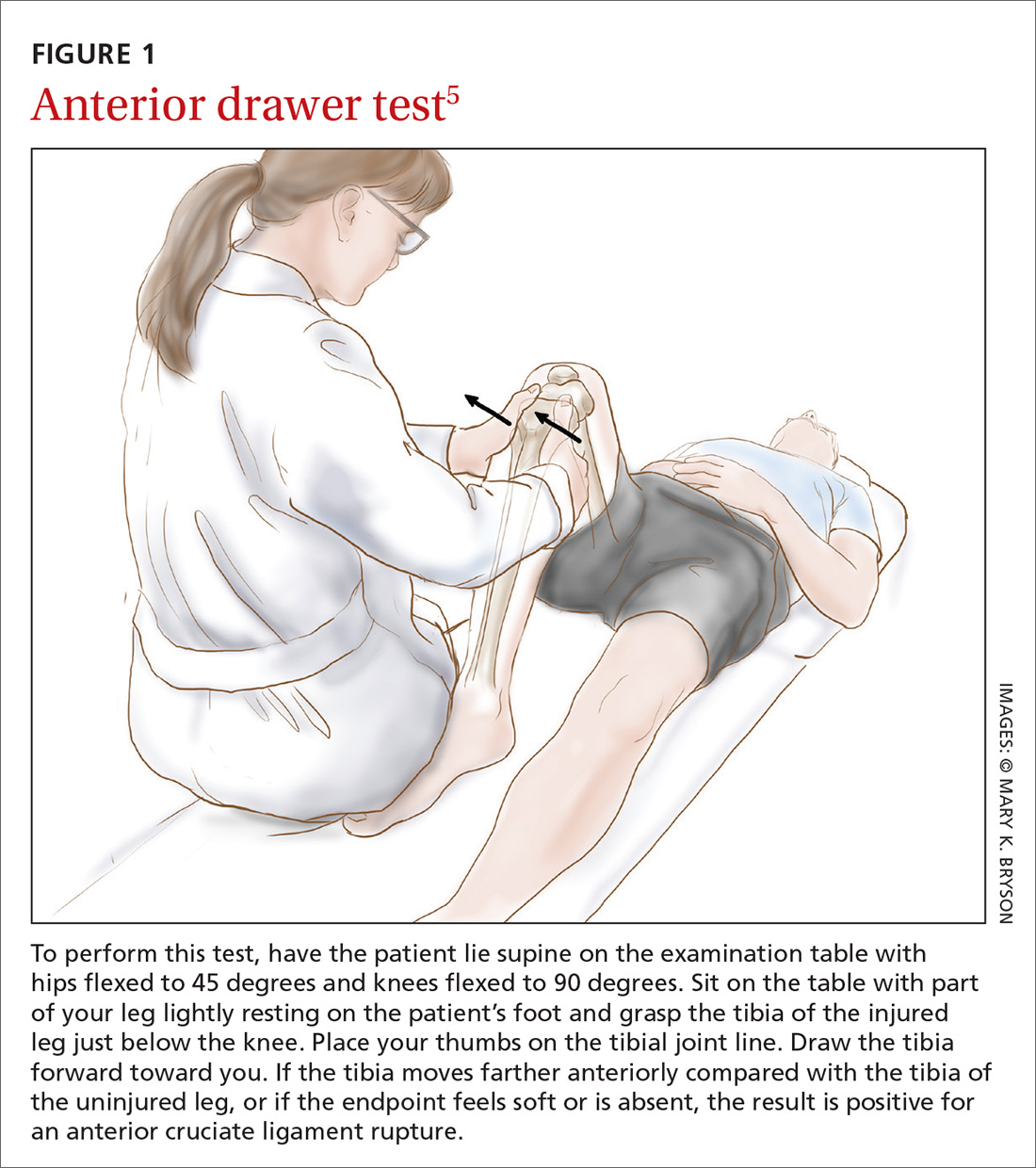

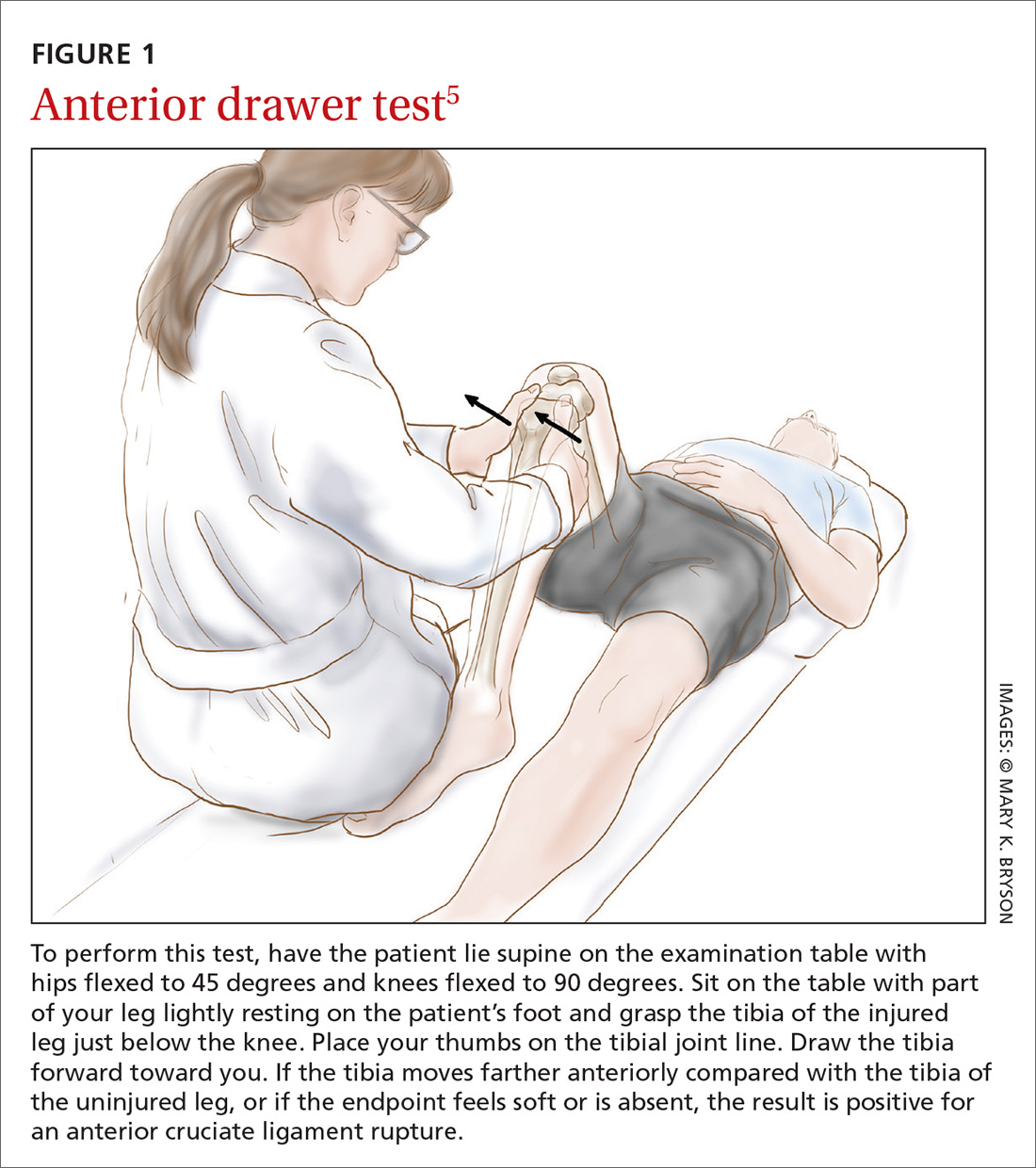

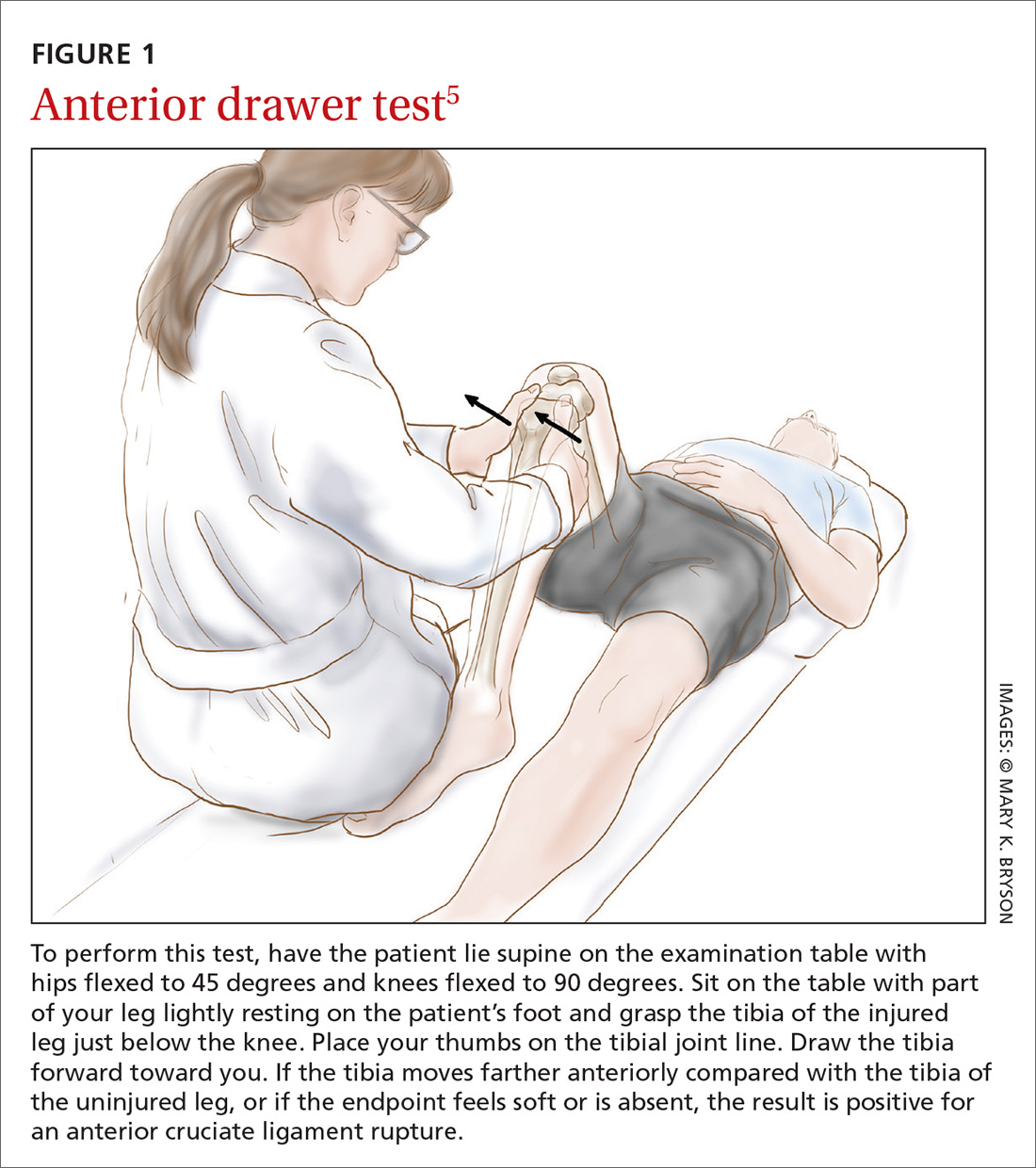

How it’s done. In this test, the patient lies supine on the examination table with hips flexed to 45 degrees and knees flexed to 90 degrees (FIGURE 1).5 The examiner sits on the table with a leg resting on the patient's foot, grasps the tibia of the injured leg just below the knee, and draws the tibia forward. If the tibia, compared with the tibia of the uninjured leg, moves farther anteriorly, or if the endpoint feels softened or is absent, the result is positive for an ACL injury.

The literature. Nine systematic reviews conclude that the anterior drawer test is inferior to the Lachman test,6-14 which we’ll describe in a moment. This is due, in part, to the anterior drawer test’s unacceptably low sensitivity and specificity in the clinical setting—especially during the acute phase.10 The most recent meta-analysis on the anterior drawer test reports a sensitivity of 38% and a specificity of 81%.9 In other words, out of 100 ruptured ligaments, only 38 will test positive with the anterior drawer test.

The literature offers possible explanations for findings on the test’s validity. First, rupture of the ACL is often accompanied by swelling of the knee caused by hemarthrosis and reactive synovitis that can prevent the patient from flexing the knee to 90 degrees. Second, the joint pain may induce a protective muscle action, also called guarding of the hamstrings, that creates a vector opposing the passive anterior translation.15

Apart from the matter of a test’s validity, it's also important to consider the test’s inter- and intra-rater reliability.16 Compared with the Lachman test, the anterior drawer test is inferior in reliability.7

Lachman test

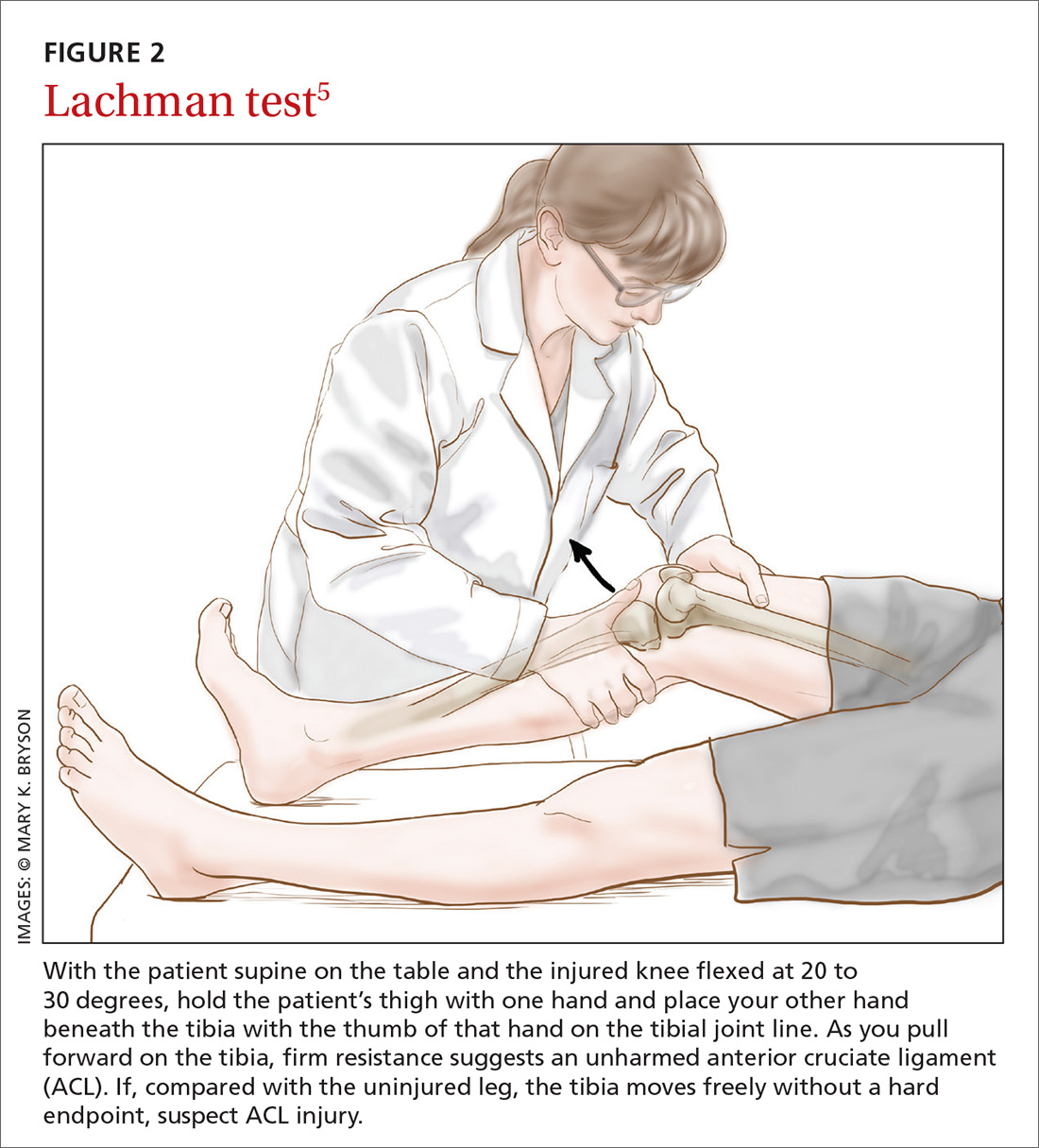

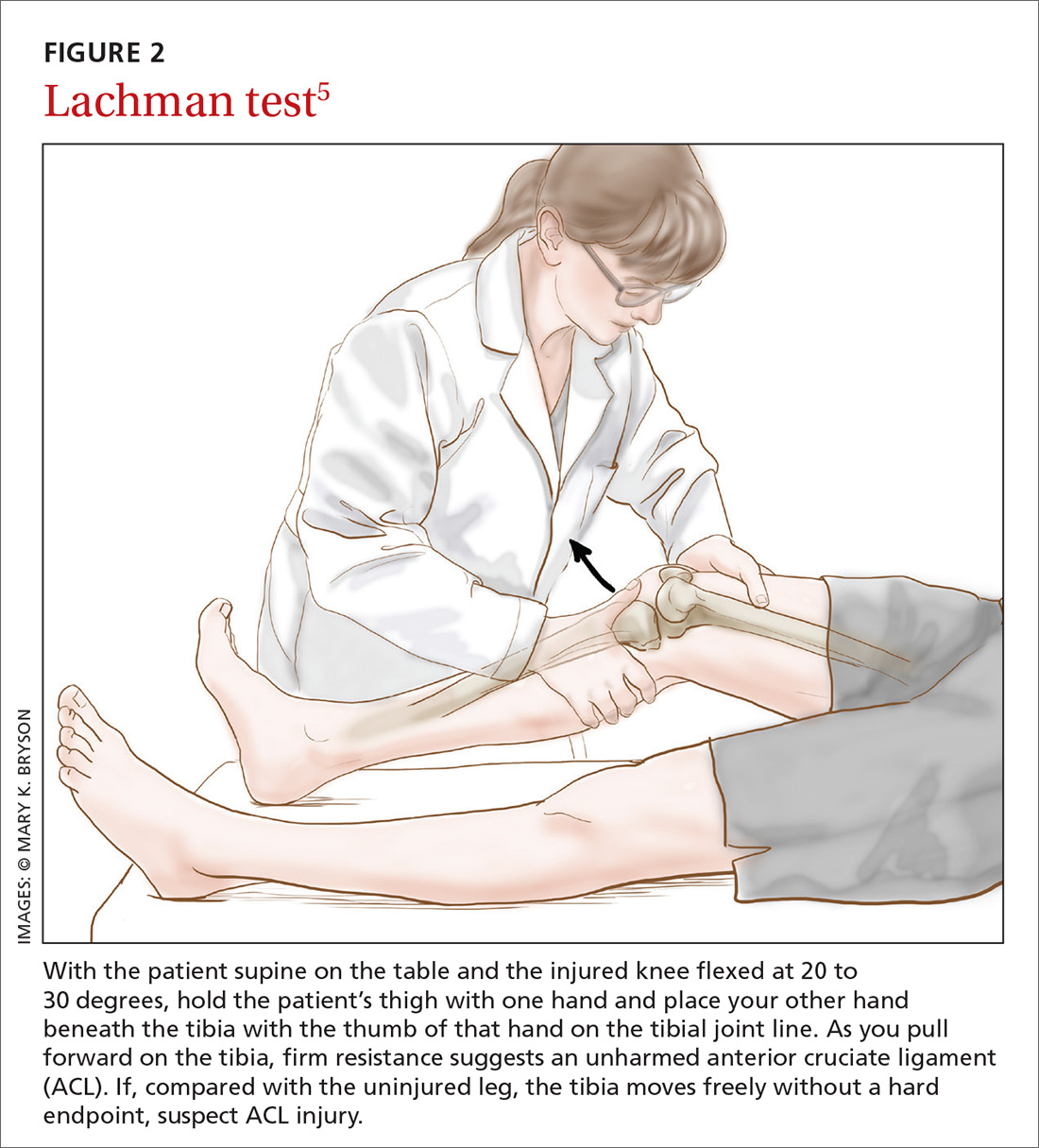

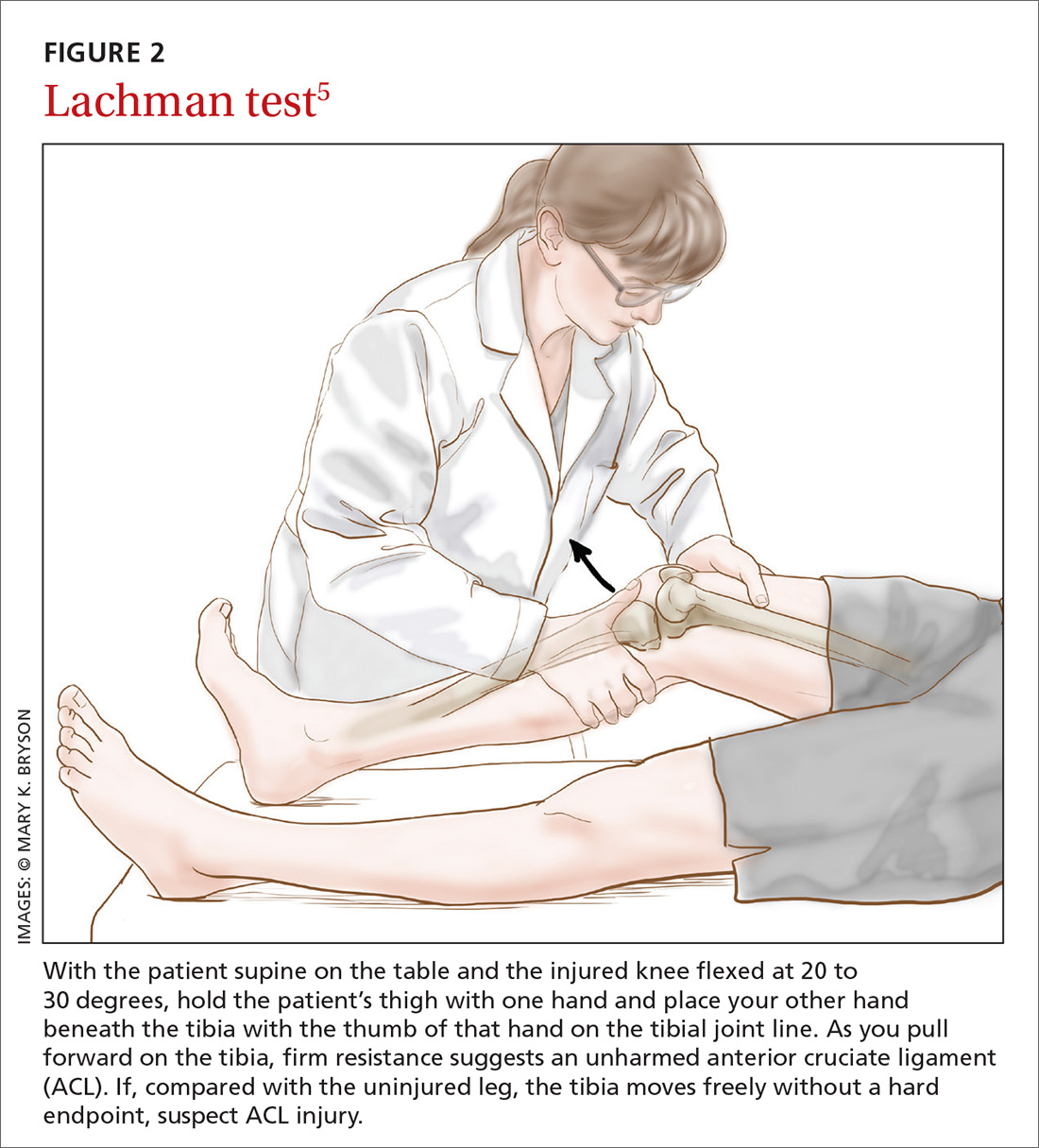

How it’s done. The Lachman test is performed with the patient supine on the table and the injured knee flexed at 20 to 30 degrees (FIGURE 2).5 The examiner holds the patient’s thigh with one hand and places the other hand beneath the tibia with the thumb of that hand on the tibial joint line. As the tibia is pulled forward, firm resistance suggests an uninjured ACL. Free movement without a hard endpoint, compared with the uninjured knee, indicates ACL injury.

The literature. The Lachman test is the most accurate of the 3 diagnostic physical procedures. The most recent meta-analysis reports a sensitivity of 68% for partial ruptures and 96% for complete ACL ruptures.6 According to a recently published overview of systematic reviews, the Lachman test has high diagnostic value in confirming or ruling out an ACL injury.17

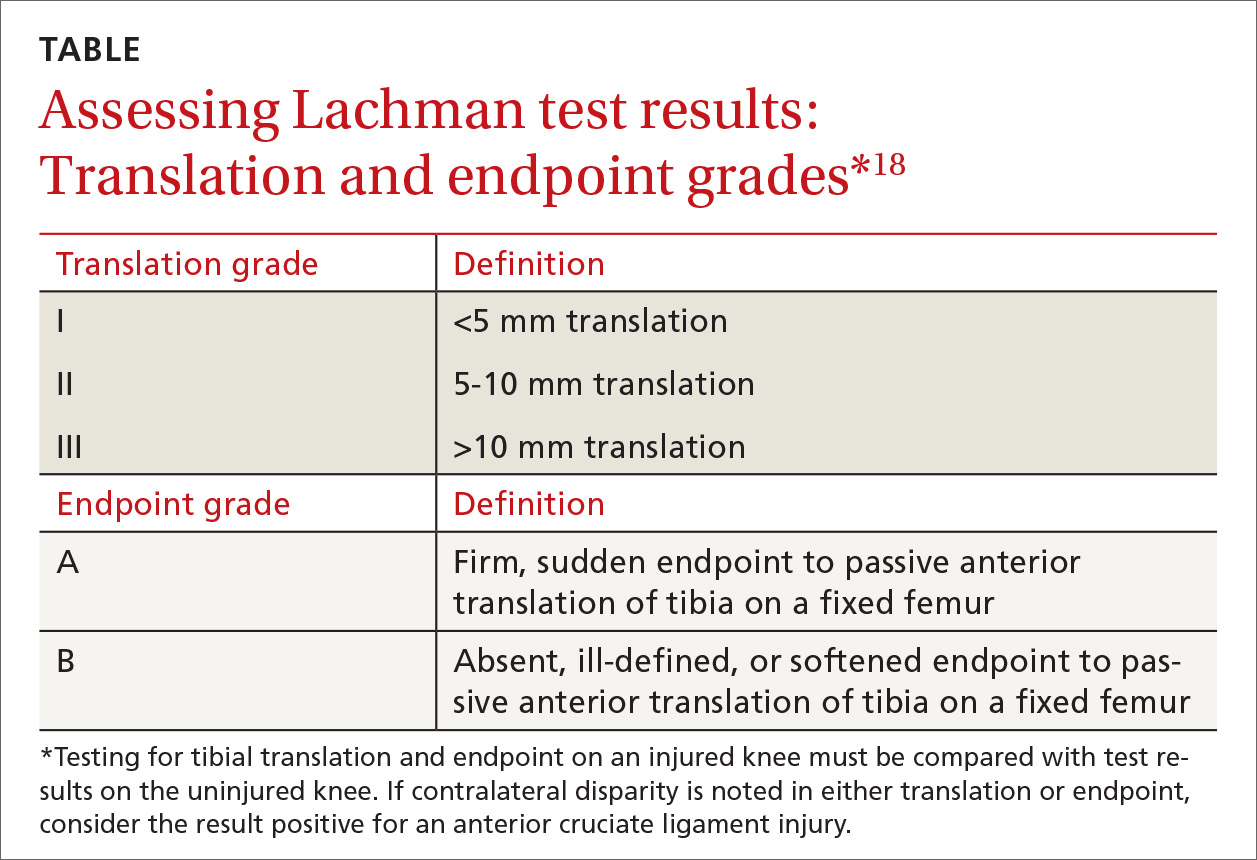

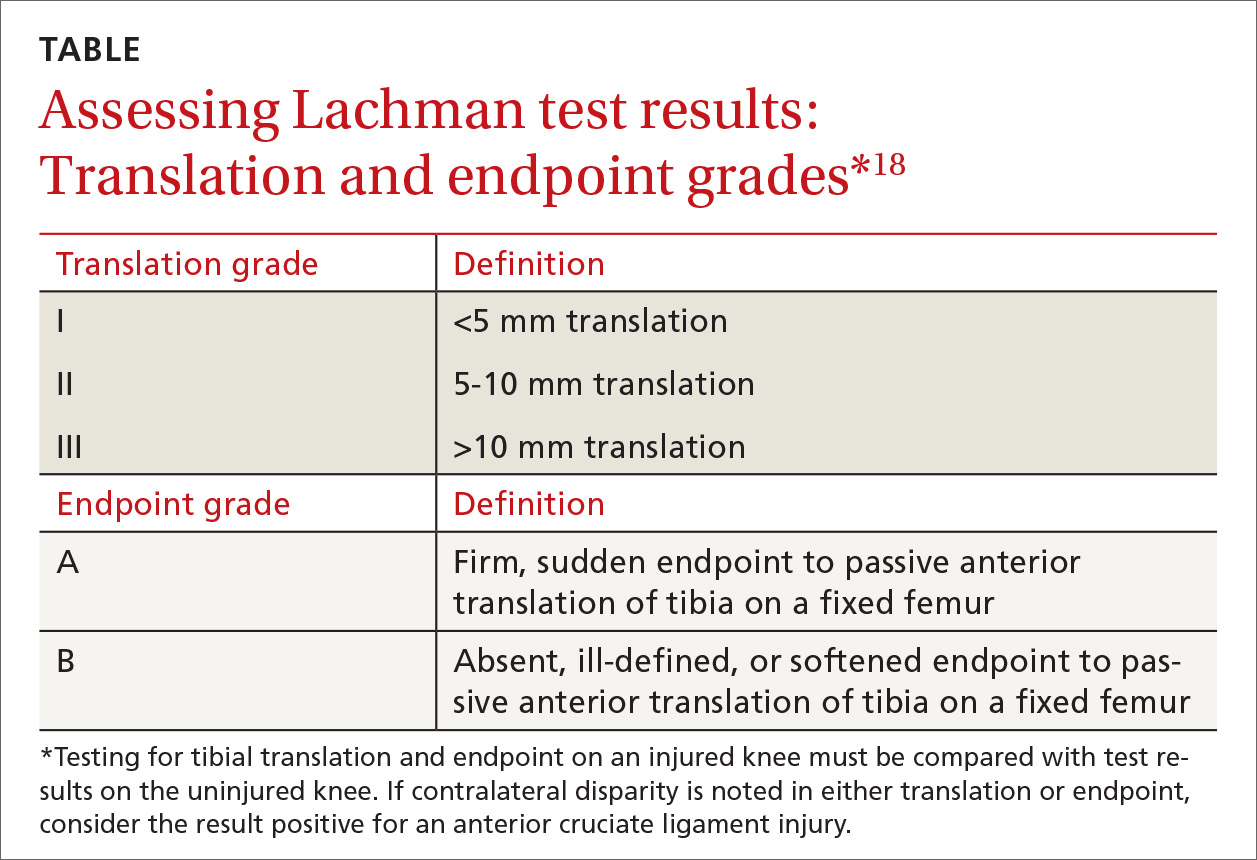

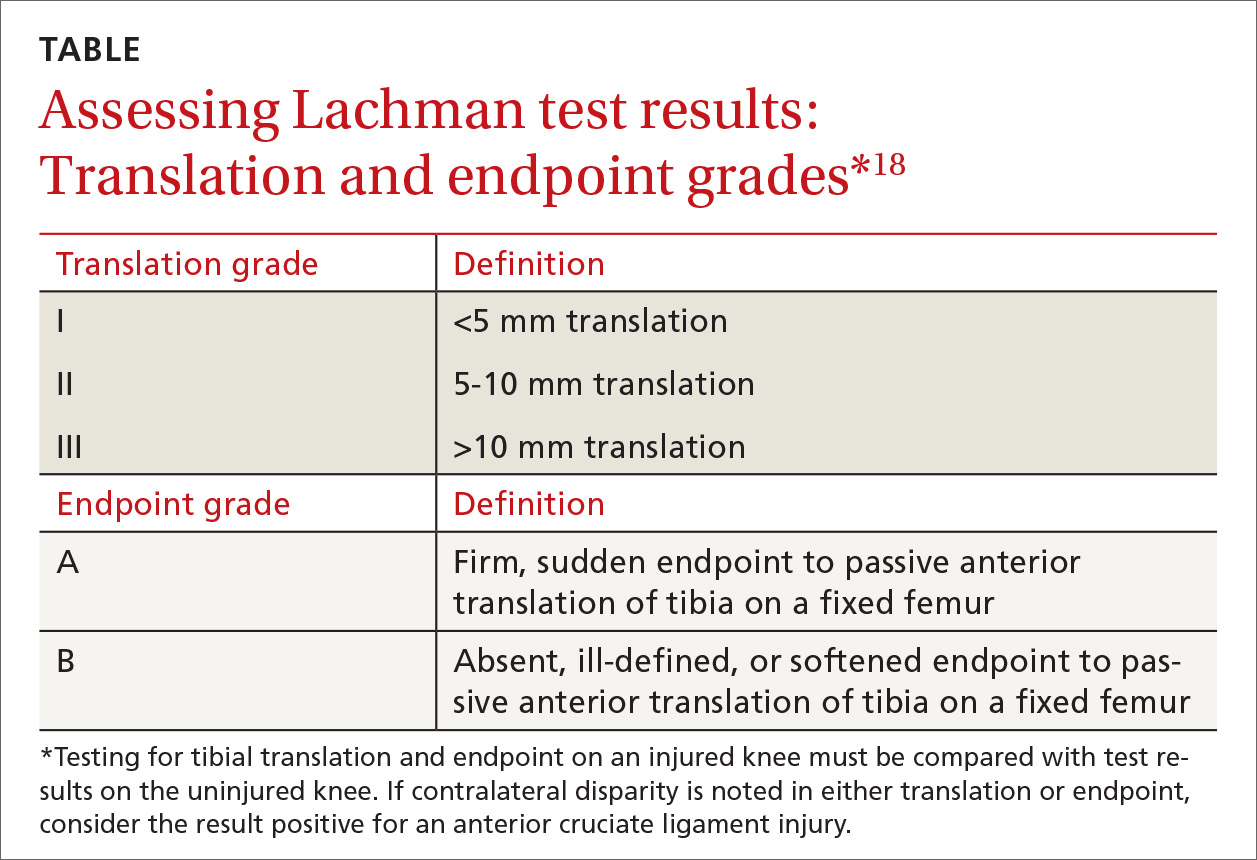

Two factors are important when assessing results of the Lachman test. The quantity of anterior translation of the tibia relative to the femur is as important as the quality of the endpoint of the anterior translation. Quantity of translation must always be compared with the unaffected knee. Quality of the endpoint in passive anterior translation should be assessed as “firm” or “sudden,” indicating an intact ACL, or as “absent, ill-defined, or softened,” indicating ACL pathology (TABLE).18

A drawback of the Lachman test is that it is challenging to perform correctly.19 The patient’s ability to relax the upper leg musculature is critically important. It is also essential to stabilize the distal femur, which can be problematic if the examiner has small hands relative to the size of the patient's leg musculature.10 These difficulties might be resolved by conducting the Lachman test with the patient in the prone position, known as the Prone Lachman.19 However, good evidence is not yet available to support this proposed solution. One systematic review, though, reports that the Prone Lachman test has the highest inter-rater reliability of all commonly used physical examination tests.7

The Lachman test is known as the test with highest validity on physical examination. When the outcome of a correctly performed Lachman test is negative, a rupture of the ACL is very unlikely.

Pivot shift test

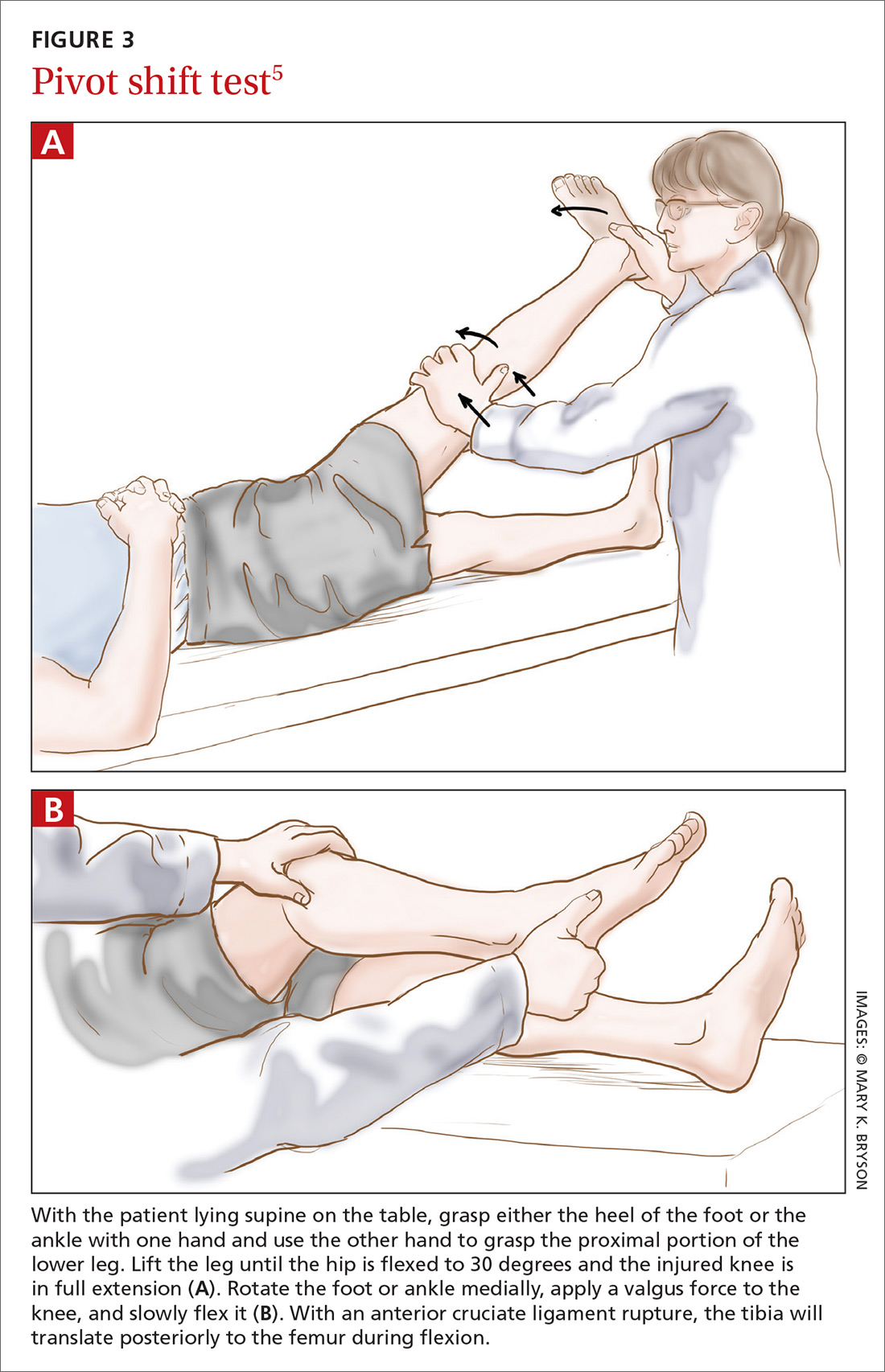

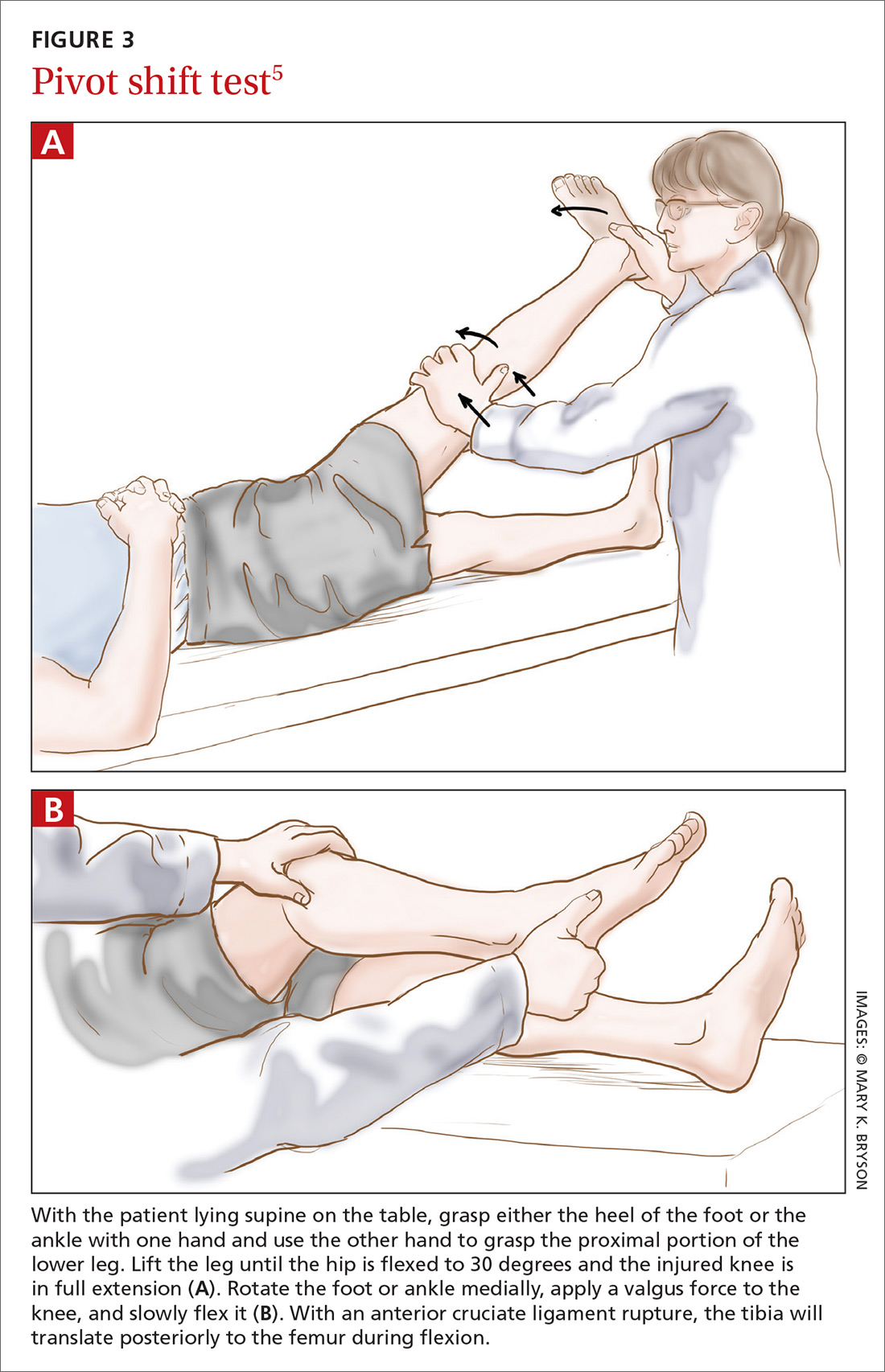

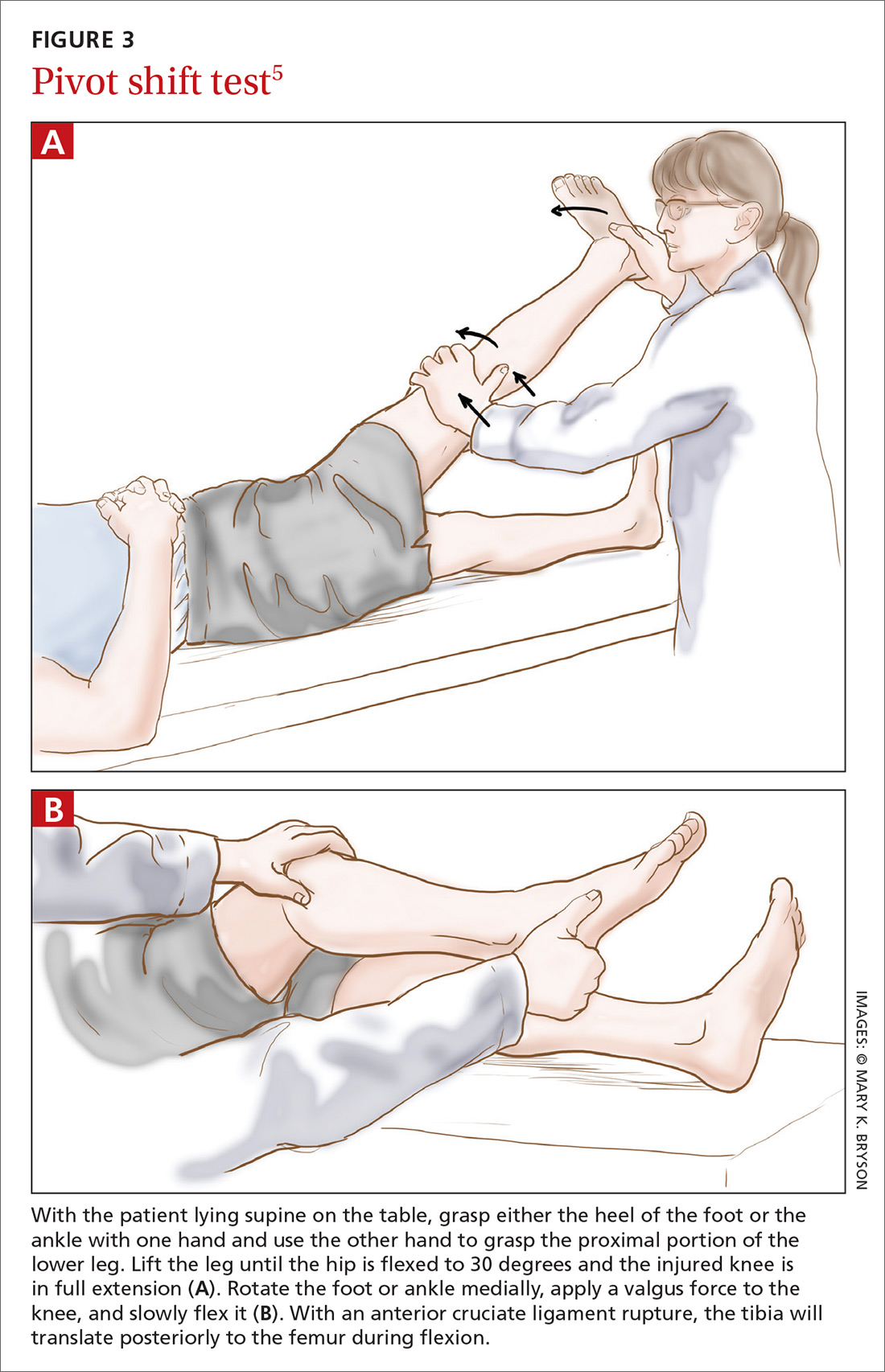

How it’s done.

The literature. The pivot shift test is technically more challenging to perform than the other 2 tests and is, therefore, less practical in the primary care setting. However, when this test is done correctly, a positive result is highly specific for ACL injury.9,10 Reported sensitivity values are contradictory. The most recent meta-analysis reports a sensitivity of 85%.6 Two other studies cite much lower values: 24% and 28%.9,10 These data suggest that the pivot shift test, when carried out correctly, can be of use in confirming a possible ACL rupture. However, the test should not be used alone in ruling out a possible ACL injury.

New diagnostic test: Lever sign test

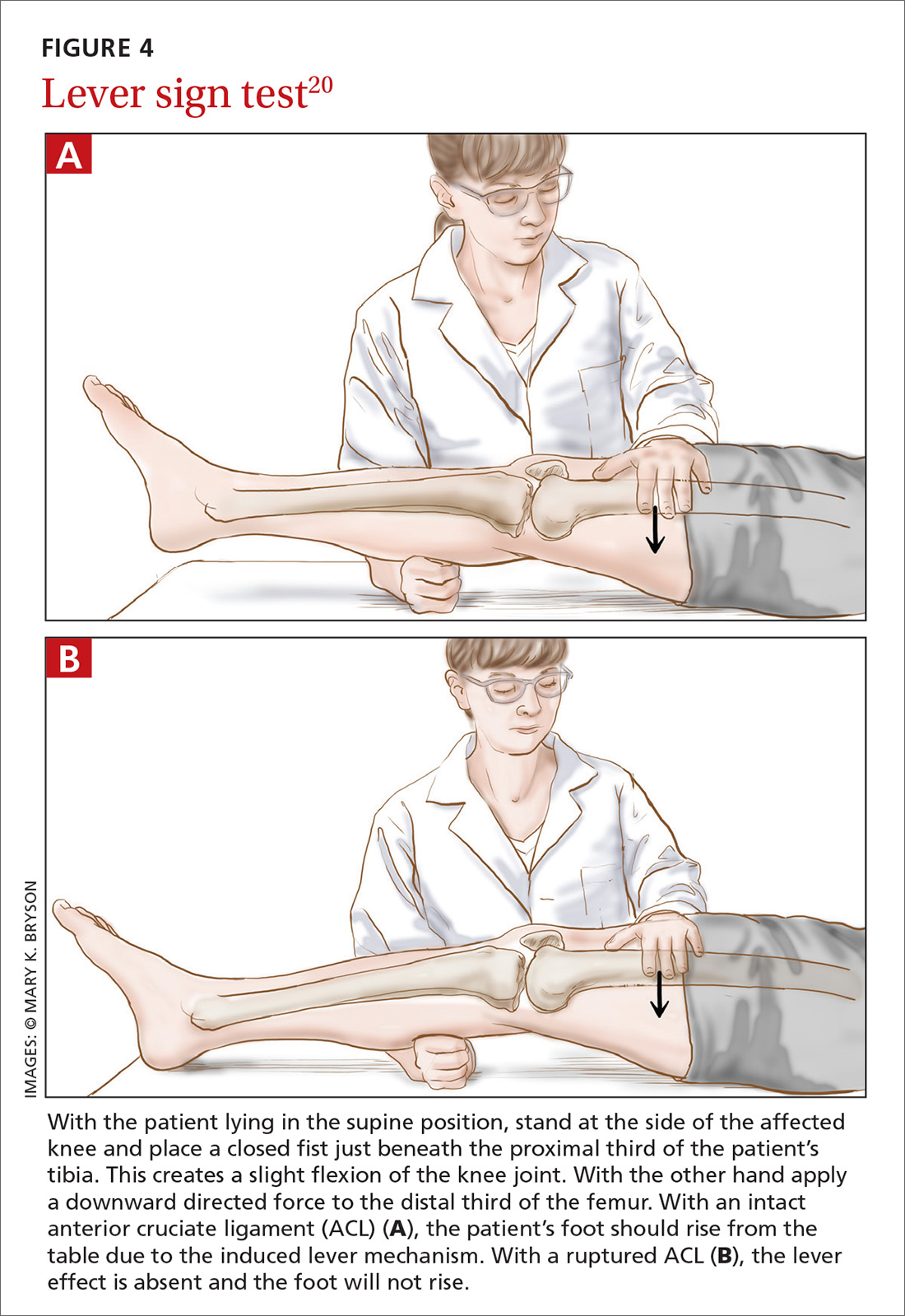

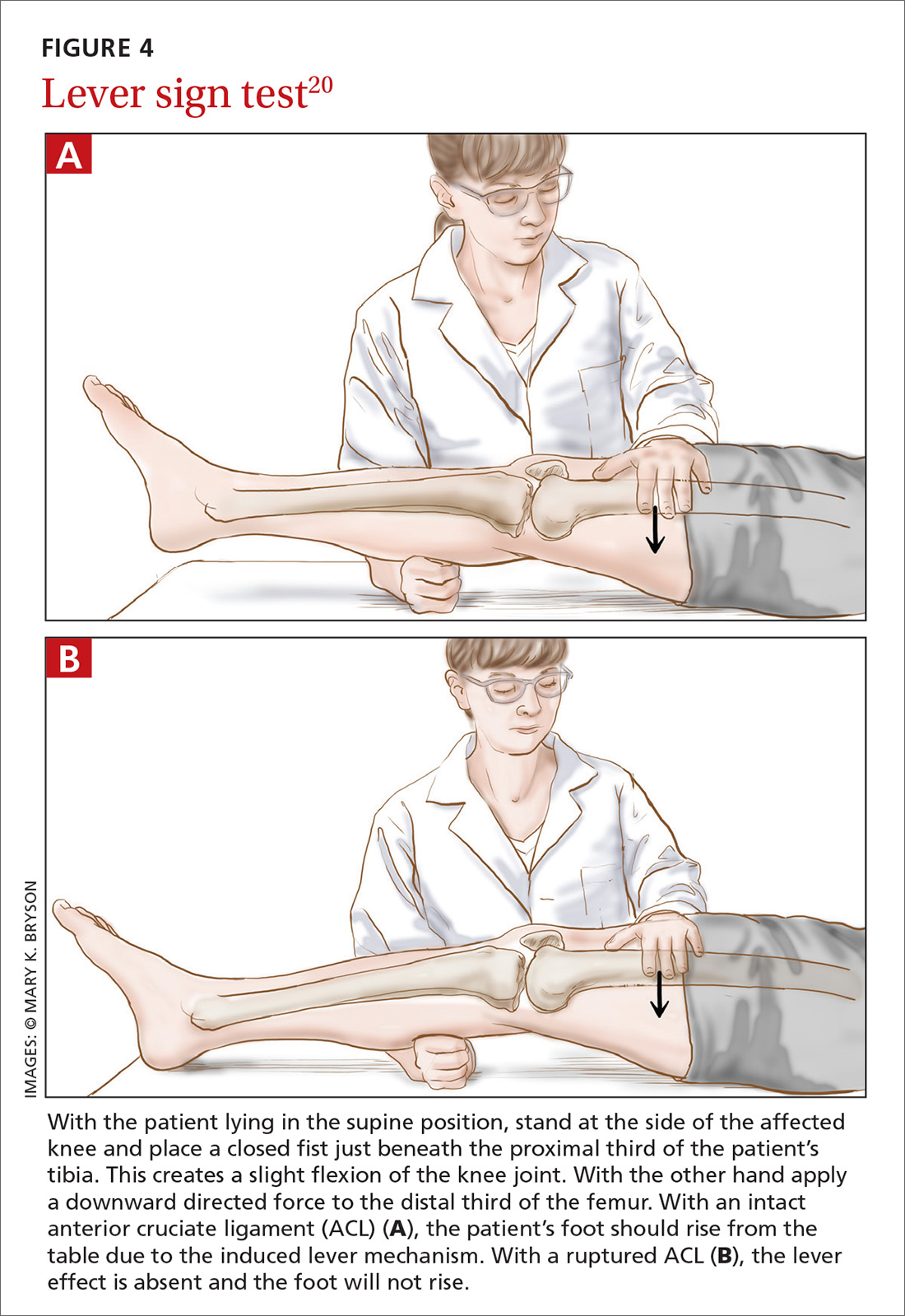

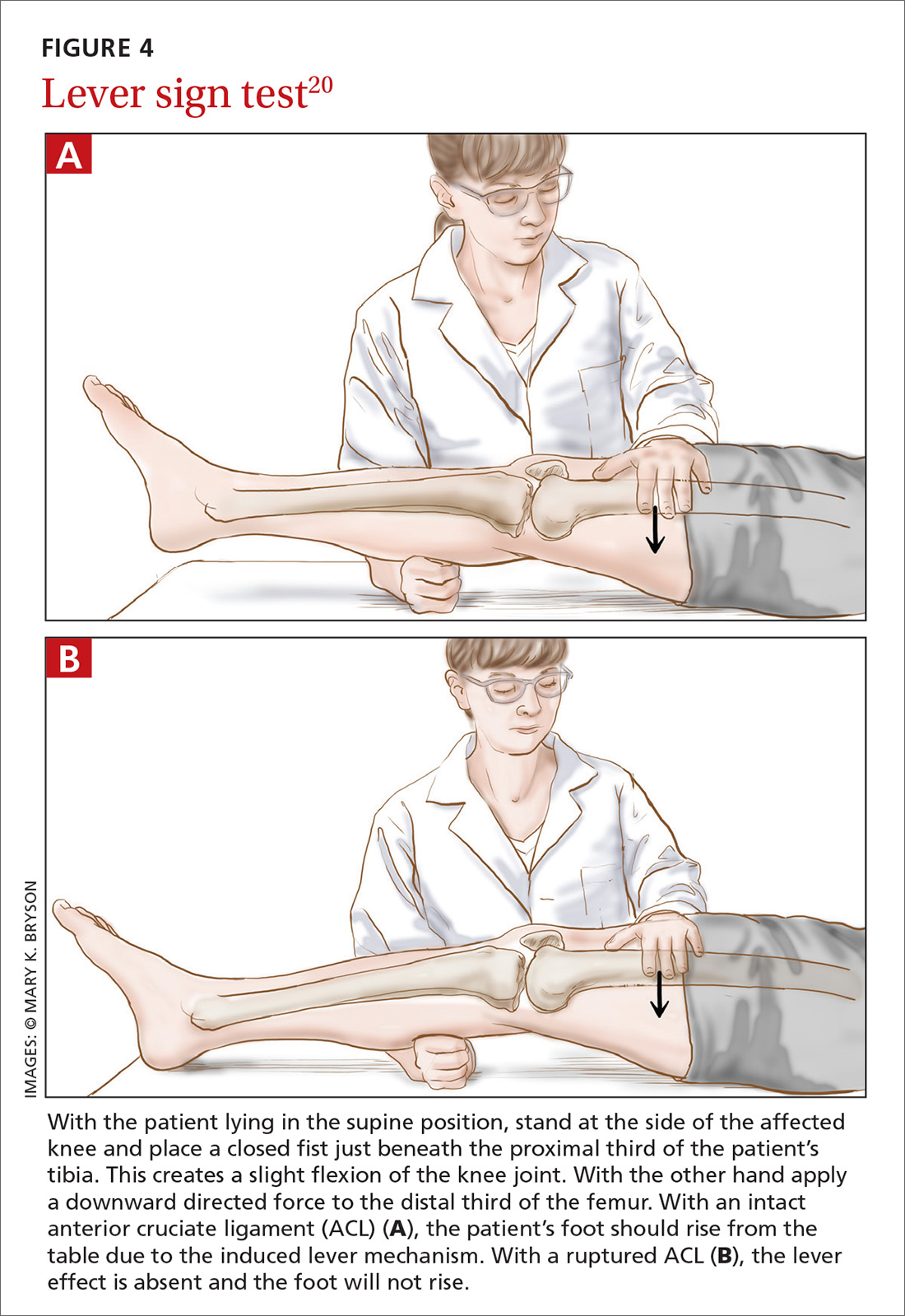

How it’s done. The lever sign test (FIGURE 4),20 introduced in the mid-2010s, is also performed with the patient lying in the supine position. The examiner stands at the side of the affected knee of the patient, places a closed fist just beneath the proximal third of the patient’s tibia, creating a slight flexion of the knee joint. With the other hand, the examiner applies a downward directed force to the distal third of the femur. With an intact ACL, the patient’s foot should rise from the table due to the induced lever mechanism. With a ruptured ACL, the lever effect is absent and the foot will not rise.

The literature. In the prospective clinical study that introduced the lever sign test, the sensitivity rate was reported at 100%—higher than that seen with the other commonly used tests.20 Another study has reported that the lever sign test was easily adopted in clinical practice and showed higher sensitivity than the Lachman test (94% vs 80% in pre-anesthesia assessment).21 However, a more recent study has shown a sensitivity of 77% for the lever sign.22 The lever sign test is relatively easy to perform and requires less examiner strength than does the Lachman test. These factors enhance applicability of the lever sign test in the primary care office and in other settings such as physical therapy centers and emergency departments.

Applying this information in primary care

Given the importance of physical examination in diagnosing ACL injury, how can the current evidence best be applied in primary care practice? Based on its good test properties and feasibility, the Lachman test is preferred in primary care. The anterior drawer test can be used, but its low accuracy must be considered in making an assessment. The pivot shift test, given its difficulty of execution, should not be used by physicians unacquainted with it.

If future research supports early reports of the lever sign test’s accuracy, it could be very helpful in family practice. Going forward, research should aim at developing a constructive strategy for applying these physical examination tests in both primary care and specialty settings.

CORRESPONDENCE

Christiaan H. Koster, Department of Trauma Surgery, VU University Medical Centre, P.O. Box 7057, 1081 HV Amsterdam, The Netherlands; [email protected].

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank Frits Oosterveld, PhD, for critically reviewing the manuscript and Ralph de Vries for his assistance in the literature search.

1. Griffin LY, Agel J, Albohm MJ, et al. Noncontact anterior cruciate ligament injuries: risk factors and prevention strategies. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2000;8:141-50.

2. American Academy of Orthopedic Surgeons. Management of anterior cruciate ligament injuries. Evidence-based clinical practice guideline. 2014. Available at: http://www.aaos.org/research/guidelines/ACLGuidelineFINAL.pdf. Accessed January 26, 2018.

3. Simon D, Mascarenhas R, Saltzman BM, et al. The relationship between anterior cruciate ligament injury and osteoarthritis of the knee. Adv Orthop. 2015;2015:928301. Available at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4410751/. Accessed January 26, 2018.

4. Hinterwimmer S, Engelschalk M, Sauerland S, et al. [Operative or conservative treatment of anterior cruciate ligament rupture: a systematic review of the literature.] Unfallchirurg. 2003;106:374-379.

5. Brown JR, Trojian TH. Anterior and posterior cruciate ligament injuries. Prim Care. 2004;31:925-956.

6. Leblanc MC, Kowalczuk M, Andruszkiewicz N, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of physical examination for anterior knee instability: a systematic review. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2015;10:2805-2813.

7. Lange T, Freiberg A, Dröge P, et al. The reliability of physical examination tests for the diagnosis of anterior cruciate ligament rupture – a systematic review. Man Ther. 2015;20:402-411.

8. Swain MS, Henschke N, Kamper SJ, et al. Accuracy of clinical tests in the diagnosis of anterior cruciate ligament injury: a systematic review. Chiropr Man Therap. 2014;22:25. Available at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4152763/. Accessed January 26, 2018.

9. van Eck CF, van den Bekerom MP, Fu FH, et al. Methods to diagnose acute anterior cruciate ligament rupture: a meta-analysis of physical examinations with and without anaesthesia. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2013;21:1895-1903.

10. Benjaminse A, Gokeler A, van der Schans CP. Clinical diagnosis of an anterior cruciate ligament rupture: a meta-analysis. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2006;36:267-288.

11. Jackson J, O’Malley PG, Kroenke K. Evaluation of acute knee pain in primary care. Ann Intern Med. 2003;139:575-588.

12. Malanga GA, Andrus S, Nadler SF, et al. Physical examination of the knee: a review of the original test description and scientific validity of common orthopedic tests. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2003;84:592-603.

13. Scholten RJ, Opstelten W, van der Plas CG, et al. Accuracy of physical diagnostic tests for assessing ruptures of the anterior cruciate ligament: a meta-analysis. J Fam. Pract. 2003;52:689-694.

14. Solomon DH, Simel DL, Bates DW, et al. The rational clinical examination. Does this patient have a torn meniscus or ligament of the knee? Value of the physical examination. JAMA. 2001;286:1610-1620.

15. Gurtler RA, Stine R, Torg JS. Lachman test evaluated. Quantification of a clinical observation. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1987;216:141-150.

16. Atkinson G, Nevill AM. Statistical methods for assessing measurement error (reliability) in variables relevant to sports medicine. Sports Med. 1998;26:217-238.

17. Décary S, Ouellet P, Vendittoli PA, et al. Diagnostic validity of physical examination tests for common knee disorders: an overview of systematic reviews and meta-analysis. Phys Ther Sport. 2017;23:143-155.

18. Mulligan EP, McGuffie DQ, Coyner K, et al. The reliability and diagnostic accuracy of assessing the translation endpoint during the Lachman test. Int J Sports Phys Ther. 2015;10:52-61.

19. Floyd RT, Peery DS, Andrews JR. Advantages of the prone Lachman versus the traditional Lachman. Orthopedics. 2008;31:671-675.

20. Lelli A, Di Turi RP, Spenciner DB, et al. The "Lever Sign": a new clinical test for the diagnosis of anterior cruciate ligament rupture. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2016;24:2794-2797.

21. Deveci A, Cankaya D, Yilmaz S, et al. The arthroscopical and radiological corelation of lever sign test for the diagnosis of anterior cruciate ligament rupture. Springerplus. 2015;4:830. Available at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4695483/. Accessed January 26, 2018.

22. Jarbo KA, Hartigan DE, Scott KL, et al. Accuracy of the Lever Sign Test in the diagnosis of anterior cruciate ligament injuries. Orthop J Sports Med. 2017;5(10):2325967117729809. Available at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5639970/. Accessed January 26, 2018.

CASE An athletic 25-year-old woman presents to her family physician complaining of a painful and swollen knee. She says that she injured the knee the day before during a judo match. The injury occurred when her upper body suddenly changed direction while her foot remained planted and her knee rotated medially. A cruciate ligament injury immediately comes to mind, but other potential diagnoses include meniscal injury, collateral ligament injury, and patellar instability. The first step in determining an accurate diagnosis is to evaluate the stability of the knee by physical examination—often a difficult task immediately following an injury.

How would you proceed?

Rupture of the anterior cruciate ligament (ACL), partial or complete, is a common injury, especially in athletes who hurt their knee in a pivoting movement.1 The number of patients who present with ACL injury is estimated at 252,000 per year.2 Cruciate ligament injury may lead to complaints of instability with subsequent inability to engage in sports activities. Cruciate ligament injury is also associated with premature development of osteoarthritis later in life.3 Operative treatment seems to be superior to conservative treatment in improving both subjective and objective measures of knee instability and in helping athletes return to their former level of activity.4

Because early detection is key to achieving the best clinical outcome, it is essential that the most accurate physical examination tests are performed during the acute phase. Primary care physicians, emergency room doctors, physical therapists, and athletic trainers are the ones who most often see these patients immediately following the injury, and they often have only the physical examination with which to assess ACL injury. Their task is to identify the patient with potential ACL injury and to refer the patient swiftly.

Three physical examination tests are most commonly used to evaluate cruciate ligament injury. The best known and most frequently used technique is the anterior drawer test. The other 2 tests, the Lachman test and the pivot shift test, are more difficult to perform and are used less often, especially by physicians untrained in their use. In addition, there is a relatively new diagnostic test: the lever sign test. The aim of our article is to provide a short, clinically relevant overview of the literature and to assess the diagnostic value of physical examination for the primary care physician.

Anterior drawer test

How it’s done. In this test, the patient lies supine on the examination table with hips flexed to 45 degrees and knees flexed to 90 degrees (FIGURE 1).5 The examiner sits on the table with a leg resting on the patient's foot, grasps the tibia of the injured leg just below the knee, and draws the tibia forward. If the tibia, compared with the tibia of the uninjured leg, moves farther anteriorly, or if the endpoint feels softened or is absent, the result is positive for an ACL injury.

The literature. Nine systematic reviews conclude that the anterior drawer test is inferior to the Lachman test,6-14 which we’ll describe in a moment. This is due, in part, to the anterior drawer test’s unacceptably low sensitivity and specificity in the clinical setting—especially during the acute phase.10 The most recent meta-analysis on the anterior drawer test reports a sensitivity of 38% and a specificity of 81%.9 In other words, out of 100 ruptured ligaments, only 38 will test positive with the anterior drawer test.

The literature offers possible explanations for findings on the test’s validity. First, rupture of the ACL is often accompanied by swelling of the knee caused by hemarthrosis and reactive synovitis that can prevent the patient from flexing the knee to 90 degrees. Second, the joint pain may induce a protective muscle action, also called guarding of the hamstrings, that creates a vector opposing the passive anterior translation.15

Apart from the matter of a test’s validity, it's also important to consider the test’s inter- and intra-rater reliability.16 Compared with the Lachman test, the anterior drawer test is inferior in reliability.7

Lachman test

How it’s done. The Lachman test is performed with the patient supine on the table and the injured knee flexed at 20 to 30 degrees (FIGURE 2).5 The examiner holds the patient’s thigh with one hand and places the other hand beneath the tibia with the thumb of that hand on the tibial joint line. As the tibia is pulled forward, firm resistance suggests an uninjured ACL. Free movement without a hard endpoint, compared with the uninjured knee, indicates ACL injury.

The literature. The Lachman test is the most accurate of the 3 diagnostic physical procedures. The most recent meta-analysis reports a sensitivity of 68% for partial ruptures and 96% for complete ACL ruptures.6 According to a recently published overview of systematic reviews, the Lachman test has high diagnostic value in confirming or ruling out an ACL injury.17

Two factors are important when assessing results of the Lachman test. The quantity of anterior translation of the tibia relative to the femur is as important as the quality of the endpoint of the anterior translation. Quantity of translation must always be compared with the unaffected knee. Quality of the endpoint in passive anterior translation should be assessed as “firm” or “sudden,” indicating an intact ACL, or as “absent, ill-defined, or softened,” indicating ACL pathology (TABLE).18

A drawback of the Lachman test is that it is challenging to perform correctly.19 The patient’s ability to relax the upper leg musculature is critically important. It is also essential to stabilize the distal femur, which can be problematic if the examiner has small hands relative to the size of the patient's leg musculature.10 These difficulties might be resolved by conducting the Lachman test with the patient in the prone position, known as the Prone Lachman.19 However, good evidence is not yet available to support this proposed solution. One systematic review, though, reports that the Prone Lachman test has the highest inter-rater reliability of all commonly used physical examination tests.7

The Lachman test is known as the test with highest validity on physical examination. When the outcome of a correctly performed Lachman test is negative, a rupture of the ACL is very unlikely.

Pivot shift test

How it’s done.

The literature. The pivot shift test is technically more challenging to perform than the other 2 tests and is, therefore, less practical in the primary care setting. However, when this test is done correctly, a positive result is highly specific for ACL injury.9,10 Reported sensitivity values are contradictory. The most recent meta-analysis reports a sensitivity of 85%.6 Two other studies cite much lower values: 24% and 28%.9,10 These data suggest that the pivot shift test, when carried out correctly, can be of use in confirming a possible ACL rupture. However, the test should not be used alone in ruling out a possible ACL injury.

New diagnostic test: Lever sign test

How it’s done. The lever sign test (FIGURE 4),20 introduced in the mid-2010s, is also performed with the patient lying in the supine position. The examiner stands at the side of the affected knee of the patient, places a closed fist just beneath the proximal third of the patient’s tibia, creating a slight flexion of the knee joint. With the other hand, the examiner applies a downward directed force to the distal third of the femur. With an intact ACL, the patient’s foot should rise from the table due to the induced lever mechanism. With a ruptured ACL, the lever effect is absent and the foot will not rise.

The literature. In the prospective clinical study that introduced the lever sign test, the sensitivity rate was reported at 100%—higher than that seen with the other commonly used tests.20 Another study has reported that the lever sign test was easily adopted in clinical practice and showed higher sensitivity than the Lachman test (94% vs 80% in pre-anesthesia assessment).21 However, a more recent study has shown a sensitivity of 77% for the lever sign.22 The lever sign test is relatively easy to perform and requires less examiner strength than does the Lachman test. These factors enhance applicability of the lever sign test in the primary care office and in other settings such as physical therapy centers and emergency departments.

Applying this information in primary care

Given the importance of physical examination in diagnosing ACL injury, how can the current evidence best be applied in primary care practice? Based on its good test properties and feasibility, the Lachman test is preferred in primary care. The anterior drawer test can be used, but its low accuracy must be considered in making an assessment. The pivot shift test, given its difficulty of execution, should not be used by physicians unacquainted with it.

If future research supports early reports of the lever sign test’s accuracy, it could be very helpful in family practice. Going forward, research should aim at developing a constructive strategy for applying these physical examination tests in both primary care and specialty settings.

CORRESPONDENCE

Christiaan H. Koster, Department of Trauma Surgery, VU University Medical Centre, P.O. Box 7057, 1081 HV Amsterdam, The Netherlands; [email protected].

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank Frits Oosterveld, PhD, for critically reviewing the manuscript and Ralph de Vries for his assistance in the literature search.

CASE An athletic 25-year-old woman presents to her family physician complaining of a painful and swollen knee. She says that she injured the knee the day before during a judo match. The injury occurred when her upper body suddenly changed direction while her foot remained planted and her knee rotated medially. A cruciate ligament injury immediately comes to mind, but other potential diagnoses include meniscal injury, collateral ligament injury, and patellar instability. The first step in determining an accurate diagnosis is to evaluate the stability of the knee by physical examination—often a difficult task immediately following an injury.

How would you proceed?

Rupture of the anterior cruciate ligament (ACL), partial or complete, is a common injury, especially in athletes who hurt their knee in a pivoting movement.1 The number of patients who present with ACL injury is estimated at 252,000 per year.2 Cruciate ligament injury may lead to complaints of instability with subsequent inability to engage in sports activities. Cruciate ligament injury is also associated with premature development of osteoarthritis later in life.3 Operative treatment seems to be superior to conservative treatment in improving both subjective and objective measures of knee instability and in helping athletes return to their former level of activity.4

Because early detection is key to achieving the best clinical outcome, it is essential that the most accurate physical examination tests are performed during the acute phase. Primary care physicians, emergency room doctors, physical therapists, and athletic trainers are the ones who most often see these patients immediately following the injury, and they often have only the physical examination with which to assess ACL injury. Their task is to identify the patient with potential ACL injury and to refer the patient swiftly.

Three physical examination tests are most commonly used to evaluate cruciate ligament injury. The best known and most frequently used technique is the anterior drawer test. The other 2 tests, the Lachman test and the pivot shift test, are more difficult to perform and are used less often, especially by physicians untrained in their use. In addition, there is a relatively new diagnostic test: the lever sign test. The aim of our article is to provide a short, clinically relevant overview of the literature and to assess the diagnostic value of physical examination for the primary care physician.

Anterior drawer test

How it’s done. In this test, the patient lies supine on the examination table with hips flexed to 45 degrees and knees flexed to 90 degrees (FIGURE 1).5 The examiner sits on the table with a leg resting on the patient's foot, grasps the tibia of the injured leg just below the knee, and draws the tibia forward. If the tibia, compared with the tibia of the uninjured leg, moves farther anteriorly, or if the endpoint feels softened or is absent, the result is positive for an ACL injury.

The literature. Nine systematic reviews conclude that the anterior drawer test is inferior to the Lachman test,6-14 which we’ll describe in a moment. This is due, in part, to the anterior drawer test’s unacceptably low sensitivity and specificity in the clinical setting—especially during the acute phase.10 The most recent meta-analysis on the anterior drawer test reports a sensitivity of 38% and a specificity of 81%.9 In other words, out of 100 ruptured ligaments, only 38 will test positive with the anterior drawer test.

The literature offers possible explanations for findings on the test’s validity. First, rupture of the ACL is often accompanied by swelling of the knee caused by hemarthrosis and reactive synovitis that can prevent the patient from flexing the knee to 90 degrees. Second, the joint pain may induce a protective muscle action, also called guarding of the hamstrings, that creates a vector opposing the passive anterior translation.15

Apart from the matter of a test’s validity, it's also important to consider the test’s inter- and intra-rater reliability.16 Compared with the Lachman test, the anterior drawer test is inferior in reliability.7

Lachman test

How it’s done. The Lachman test is performed with the patient supine on the table and the injured knee flexed at 20 to 30 degrees (FIGURE 2).5 The examiner holds the patient’s thigh with one hand and places the other hand beneath the tibia with the thumb of that hand on the tibial joint line. As the tibia is pulled forward, firm resistance suggests an uninjured ACL. Free movement without a hard endpoint, compared with the uninjured knee, indicates ACL injury.

The literature. The Lachman test is the most accurate of the 3 diagnostic physical procedures. The most recent meta-analysis reports a sensitivity of 68% for partial ruptures and 96% for complete ACL ruptures.6 According to a recently published overview of systematic reviews, the Lachman test has high diagnostic value in confirming or ruling out an ACL injury.17

Two factors are important when assessing results of the Lachman test. The quantity of anterior translation of the tibia relative to the femur is as important as the quality of the endpoint of the anterior translation. Quantity of translation must always be compared with the unaffected knee. Quality of the endpoint in passive anterior translation should be assessed as “firm” or “sudden,” indicating an intact ACL, or as “absent, ill-defined, or softened,” indicating ACL pathology (TABLE).18

A drawback of the Lachman test is that it is challenging to perform correctly.19 The patient’s ability to relax the upper leg musculature is critically important. It is also essential to stabilize the distal femur, which can be problematic if the examiner has small hands relative to the size of the patient's leg musculature.10 These difficulties might be resolved by conducting the Lachman test with the patient in the prone position, known as the Prone Lachman.19 However, good evidence is not yet available to support this proposed solution. One systematic review, though, reports that the Prone Lachman test has the highest inter-rater reliability of all commonly used physical examination tests.7

The Lachman test is known as the test with highest validity on physical examination. When the outcome of a correctly performed Lachman test is negative, a rupture of the ACL is very unlikely.

Pivot shift test

How it’s done.

The literature. The pivot shift test is technically more challenging to perform than the other 2 tests and is, therefore, less practical in the primary care setting. However, when this test is done correctly, a positive result is highly specific for ACL injury.9,10 Reported sensitivity values are contradictory. The most recent meta-analysis reports a sensitivity of 85%.6 Two other studies cite much lower values: 24% and 28%.9,10 These data suggest that the pivot shift test, when carried out correctly, can be of use in confirming a possible ACL rupture. However, the test should not be used alone in ruling out a possible ACL injury.

New diagnostic test: Lever sign test

How it’s done. The lever sign test (FIGURE 4),20 introduced in the mid-2010s, is also performed with the patient lying in the supine position. The examiner stands at the side of the affected knee of the patient, places a closed fist just beneath the proximal third of the patient’s tibia, creating a slight flexion of the knee joint. With the other hand, the examiner applies a downward directed force to the distal third of the femur. With an intact ACL, the patient’s foot should rise from the table due to the induced lever mechanism. With a ruptured ACL, the lever effect is absent and the foot will not rise.

The literature. In the prospective clinical study that introduced the lever sign test, the sensitivity rate was reported at 100%—higher than that seen with the other commonly used tests.20 Another study has reported that the lever sign test was easily adopted in clinical practice and showed higher sensitivity than the Lachman test (94% vs 80% in pre-anesthesia assessment).21 However, a more recent study has shown a sensitivity of 77% for the lever sign.22 The lever sign test is relatively easy to perform and requires less examiner strength than does the Lachman test. These factors enhance applicability of the lever sign test in the primary care office and in other settings such as physical therapy centers and emergency departments.

Applying this information in primary care

Given the importance of physical examination in diagnosing ACL injury, how can the current evidence best be applied in primary care practice? Based on its good test properties and feasibility, the Lachman test is preferred in primary care. The anterior drawer test can be used, but its low accuracy must be considered in making an assessment. The pivot shift test, given its difficulty of execution, should not be used by physicians unacquainted with it.

If future research supports early reports of the lever sign test’s accuracy, it could be very helpful in family practice. Going forward, research should aim at developing a constructive strategy for applying these physical examination tests in both primary care and specialty settings.

CORRESPONDENCE

Christiaan H. Koster, Department of Trauma Surgery, VU University Medical Centre, P.O. Box 7057, 1081 HV Amsterdam, The Netherlands; [email protected].

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank Frits Oosterveld, PhD, for critically reviewing the manuscript and Ralph de Vries for his assistance in the literature search.

1. Griffin LY, Agel J, Albohm MJ, et al. Noncontact anterior cruciate ligament injuries: risk factors and prevention strategies. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2000;8:141-50.

2. American Academy of Orthopedic Surgeons. Management of anterior cruciate ligament injuries. Evidence-based clinical practice guideline. 2014. Available at: http://www.aaos.org/research/guidelines/ACLGuidelineFINAL.pdf. Accessed January 26, 2018.

3. Simon D, Mascarenhas R, Saltzman BM, et al. The relationship between anterior cruciate ligament injury and osteoarthritis of the knee. Adv Orthop. 2015;2015:928301. Available at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4410751/. Accessed January 26, 2018.

4. Hinterwimmer S, Engelschalk M, Sauerland S, et al. [Operative or conservative treatment of anterior cruciate ligament rupture: a systematic review of the literature.] Unfallchirurg. 2003;106:374-379.

5. Brown JR, Trojian TH. Anterior and posterior cruciate ligament injuries. Prim Care. 2004;31:925-956.

6. Leblanc MC, Kowalczuk M, Andruszkiewicz N, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of physical examination for anterior knee instability: a systematic review. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2015;10:2805-2813.

7. Lange T, Freiberg A, Dröge P, et al. The reliability of physical examination tests for the diagnosis of anterior cruciate ligament rupture – a systematic review. Man Ther. 2015;20:402-411.

8. Swain MS, Henschke N, Kamper SJ, et al. Accuracy of clinical tests in the diagnosis of anterior cruciate ligament injury: a systematic review. Chiropr Man Therap. 2014;22:25. Available at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4152763/. Accessed January 26, 2018.

9. van Eck CF, van den Bekerom MP, Fu FH, et al. Methods to diagnose acute anterior cruciate ligament rupture: a meta-analysis of physical examinations with and without anaesthesia. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2013;21:1895-1903.

10. Benjaminse A, Gokeler A, van der Schans CP. Clinical diagnosis of an anterior cruciate ligament rupture: a meta-analysis. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2006;36:267-288.

11. Jackson J, O’Malley PG, Kroenke K. Evaluation of acute knee pain in primary care. Ann Intern Med. 2003;139:575-588.

12. Malanga GA, Andrus S, Nadler SF, et al. Physical examination of the knee: a review of the original test description and scientific validity of common orthopedic tests. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2003;84:592-603.

13. Scholten RJ, Opstelten W, van der Plas CG, et al. Accuracy of physical diagnostic tests for assessing ruptures of the anterior cruciate ligament: a meta-analysis. J Fam. Pract. 2003;52:689-694.

14. Solomon DH, Simel DL, Bates DW, et al. The rational clinical examination. Does this patient have a torn meniscus or ligament of the knee? Value of the physical examination. JAMA. 2001;286:1610-1620.

15. Gurtler RA, Stine R, Torg JS. Lachman test evaluated. Quantification of a clinical observation. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1987;216:141-150.

16. Atkinson G, Nevill AM. Statistical methods for assessing measurement error (reliability) in variables relevant to sports medicine. Sports Med. 1998;26:217-238.

17. Décary S, Ouellet P, Vendittoli PA, et al. Diagnostic validity of physical examination tests for common knee disorders: an overview of systematic reviews and meta-analysis. Phys Ther Sport. 2017;23:143-155.

18. Mulligan EP, McGuffie DQ, Coyner K, et al. The reliability and diagnostic accuracy of assessing the translation endpoint during the Lachman test. Int J Sports Phys Ther. 2015;10:52-61.

19. Floyd RT, Peery DS, Andrews JR. Advantages of the prone Lachman versus the traditional Lachman. Orthopedics. 2008;31:671-675.

20. Lelli A, Di Turi RP, Spenciner DB, et al. The "Lever Sign": a new clinical test for the diagnosis of anterior cruciate ligament rupture. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2016;24:2794-2797.

21. Deveci A, Cankaya D, Yilmaz S, et al. The arthroscopical and radiological corelation of lever sign test for the diagnosis of anterior cruciate ligament rupture. Springerplus. 2015;4:830. Available at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4695483/. Accessed January 26, 2018.

22. Jarbo KA, Hartigan DE, Scott KL, et al. Accuracy of the Lever Sign Test in the diagnosis of anterior cruciate ligament injuries. Orthop J Sports Med. 2017;5(10):2325967117729809. Available at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5639970/. Accessed January 26, 2018.

1. Griffin LY, Agel J, Albohm MJ, et al. Noncontact anterior cruciate ligament injuries: risk factors and prevention strategies. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2000;8:141-50.

2. American Academy of Orthopedic Surgeons. Management of anterior cruciate ligament injuries. Evidence-based clinical practice guideline. 2014. Available at: http://www.aaos.org/research/guidelines/ACLGuidelineFINAL.pdf. Accessed January 26, 2018.

3. Simon D, Mascarenhas R, Saltzman BM, et al. The relationship between anterior cruciate ligament injury and osteoarthritis of the knee. Adv Orthop. 2015;2015:928301. Available at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4410751/. Accessed January 26, 2018.

4. Hinterwimmer S, Engelschalk M, Sauerland S, et al. [Operative or conservative treatment of anterior cruciate ligament rupture: a systematic review of the literature.] Unfallchirurg. 2003;106:374-379.

5. Brown JR, Trojian TH. Anterior and posterior cruciate ligament injuries. Prim Care. 2004;31:925-956.

6. Leblanc MC, Kowalczuk M, Andruszkiewicz N, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of physical examination for anterior knee instability: a systematic review. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2015;10:2805-2813.

7. Lange T, Freiberg A, Dröge P, et al. The reliability of physical examination tests for the diagnosis of anterior cruciate ligament rupture – a systematic review. Man Ther. 2015;20:402-411.

8. Swain MS, Henschke N, Kamper SJ, et al. Accuracy of clinical tests in the diagnosis of anterior cruciate ligament injury: a systematic review. Chiropr Man Therap. 2014;22:25. Available at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4152763/. Accessed January 26, 2018.

9. van Eck CF, van den Bekerom MP, Fu FH, et al. Methods to diagnose acute anterior cruciate ligament rupture: a meta-analysis of physical examinations with and without anaesthesia. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2013;21:1895-1903.

10. Benjaminse A, Gokeler A, van der Schans CP. Clinical diagnosis of an anterior cruciate ligament rupture: a meta-analysis. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2006;36:267-288.

11. Jackson J, O’Malley PG, Kroenke K. Evaluation of acute knee pain in primary care. Ann Intern Med. 2003;139:575-588.

12. Malanga GA, Andrus S, Nadler SF, et al. Physical examination of the knee: a review of the original test description and scientific validity of common orthopedic tests. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2003;84:592-603.

13. Scholten RJ, Opstelten W, van der Plas CG, et al. Accuracy of physical diagnostic tests for assessing ruptures of the anterior cruciate ligament: a meta-analysis. J Fam. Pract. 2003;52:689-694.

14. Solomon DH, Simel DL, Bates DW, et al. The rational clinical examination. Does this patient have a torn meniscus or ligament of the knee? Value of the physical examination. JAMA. 2001;286:1610-1620.

15. Gurtler RA, Stine R, Torg JS. Lachman test evaluated. Quantification of a clinical observation. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1987;216:141-150.

16. Atkinson G, Nevill AM. Statistical methods for assessing measurement error (reliability) in variables relevant to sports medicine. Sports Med. 1998;26:217-238.

17. Décary S, Ouellet P, Vendittoli PA, et al. Diagnostic validity of physical examination tests for common knee disorders: an overview of systematic reviews and meta-analysis. Phys Ther Sport. 2017;23:143-155.

18. Mulligan EP, McGuffie DQ, Coyner K, et al. The reliability and diagnostic accuracy of assessing the translation endpoint during the Lachman test. Int J Sports Phys Ther. 2015;10:52-61.

19. Floyd RT, Peery DS, Andrews JR. Advantages of the prone Lachman versus the traditional Lachman. Orthopedics. 2008;31:671-675.

20. Lelli A, Di Turi RP, Spenciner DB, et al. The "Lever Sign": a new clinical test for the diagnosis of anterior cruciate ligament rupture. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2016;24:2794-2797.

21. Deveci A, Cankaya D, Yilmaz S, et al. The arthroscopical and radiological corelation of lever sign test for the diagnosis of anterior cruciate ligament rupture. Springerplus. 2015;4:830. Available at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4695483/. Accessed January 26, 2018.

22. Jarbo KA, Hartigan DE, Scott KL, et al. Accuracy of the Lever Sign Test in the diagnosis of anterior cruciate ligament injuries. Orthop J Sports Med. 2017;5(10):2325967117729809. Available at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5639970/. Accessed January 26, 2018.

PRACTICE RECOMMENDATIONS

› Consider using the Lachman test, known to have higher validity than other anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) physical examination tests. When the outcome of a correctly performed test is negative, a rupture of the ACL is unlikely. A

› Use the pivot shift test to confirm a possible ACL rupture only if good execution is assured. Do not use the pivot shift test alone to rule out a possible ACL injury. A

› Familiarize yourself with the lever sign test, which is easy to perform but has yielded varying reports on sensitivity and specificity for ACL rupture. B

Strength of recommendation (SOR)

A Good-quality patient-oriented evidence

B Inconsistent or limited-quality patient-oriented evidence

C Consensus, usual practice, opinion, disease-oriented evidence, case series