User login

Supporting the Needs of Stroke Caregivers Across the Care Continuum

From the School of Nursing, University of North Carolina-Wilmington, Wilmington, NC (Dr. Lutz), and the Kaiser Foundation Rehabilitation Center, Kaiser Permanente, Vallejo, CA (Ms. Camicia).

Abstract

- Objectives: To describe issues faced by stroke family caregivers, discuss evidence-based interventions to improve caregiver outcomes, and provide recommendations for clinicians caring for stroke survivors and their family caregivers.

- Methods: Literature review.

- Results: Caregiver health is linked to the stroke survivor’s degree of functional recovery; the more severe the level of disability, the more likely the caregiver will experience higher levels of strain, increased depression, and poor health. Inadequate caregiver preparation contributes to poorer outcomes. Caregivers describe many unmet needs including skills training; communicating with providers; resource identification and activation; finances; respite; and emotional support. Caregivers need to be assessed for gaps in preparation to provide care. Interventions are recommended that combine skill-building and psycho-educational strategies; are tailored to individual caregiver needs; are face-to-face when feasible; and include 5 to 9 sessions. Family counseling may also be indicated. Intermittent assessment of caregiving outcomes should be conducted so that changing needs can be addressed.

- Conclusions: Stroke caregiving affects the caregiver’s physical, mental, and emotional health, and these effects are sustained over time. Poorly prepared caregivers are more likely to experience negative outcomes and their needs are high during the transition from inpatient care to home. Ongoing support is also important, especially for caregivers who are caring for a stroke survivor with moderate to severe functional limitations. In order to better address unmet needs of stroke caregivers, intermittent assessments should be conducted so that interventions can be tailored to their changing needs over time.

Key words: stroke; family caregivers; care transitions; patient-centered care.

Stroke is a leading cause of major disability in the United States [1] and around the world [2]. Of the estimated 6.6 million stroke survivors living in the US, more than 4.5 million have some level of disability following stroke [1]. In 2009, more than 970,000 persons were hospitalized with stroke in the US with an average length of stay of 5.3 days [3]. Approximately 44% of stroke survivors are discharged home directly from acute care without post-acute care [4]. Only about 25% of stroke survivors receive care in inpatient rehabilitation facilities [4] even though the American Heart Association (AHA) stroke rehabilitation guidelines recommend this level of care for qualified patients [5]. Regardless of the care trajectory, when stroke survivors return home they frequently require assistance with basic and instrumental activities of daily living (BADL/IADL), usually provided by family members who often feel unprepared and overwhelmed by the demands and responsibilities of this caregiving role.

The deleterious effects of caregiving have been identified as a major public health concern [6]. A robust body of literature has established that caregivers are often adversely affected by the demands of their caregiving role. However, much of this literature focuses on caregivers for persons with dementia. Needs of stroke caregivers are categorically different from caregivers of persons with dementia in that stroke is an unpredictable, life-disrupting, crisis event that occurs suddenly leaving family members with insufficient time to prepare for the new roles and caregiving responsibilities. The patient typically transitions from being cared for by multiple providers in an acute care, inpatient rehabilitation facility, or skilled nursing facility (SNF)—24 hours a day, 7 days a week—to relying fully on one person (most often a spouse or adult child) who may not be ready to handle the overwhelming demands and constant vigilance required for adequate care at home. Studies have repeatedly demonstrated the damaging health effects of caregiving. Caregivers describe feeling isolated, abandoned, and alone [7–9], and what frequently follows is a predictable trajectory of depression and deteriorating health and well-being [7,10–13]. The purpose of this article is to describe difficulties and issues faced by family members who are caring for a loved one following stroke, discuss evidence-based interventions designed to improve stroke caregiver outcomes, and provide recommendations for clinicians who care for stroke survivors and their family caregivers post-stroke.

Difficulties and Issues Faced by Caregivers

With an aging population and increasing incidence of stroke, it is imperative that we identify and address the ongoing needs of stroke survivors and their family caregivers in the post-stroke recovery period. Multiple studies acknowledge that stroke is a life-changing event for patients and their family members [9,14] that often results in overwhelming feelings of uncertainty, fear [15], grief, and loss [9]. Stroke also can have long-term effects on the health of stroke survivors and their family caregivers. Studies have identified the effects of caregiving on the health of caregivers and subsequent links between stroke survivor and caregiver outcomes over time [12,16,17]; the ongoing needs of stroke caregivers post-discharge [18,19]; and the importance of assessing caregiver preparedness and subsequent caregiving outcomes [5,20].

Effects of Caregiving on the Health of Caregivers and Stroke Survivors

Research on stroke caregiving consistently indicates that caregiver health is inextricably linked to the stroke survivor’s degree of physical, cognitive, psychological, and emotional recovery. The more severe the patient’s level of disability, the more likely the caregiver will experience higher levels of strain, increased depression, and poor health outcomes [21]. Studies also indicate that certain caregiver characteristics, such as being female or having lower educational level, pre-existing health conditions [7,22,23], poor family functioning, lack of social support [22,24], or lack of preparation [25], are all risk factors for poorer caregiver outcomes.

Stroke family caregivers often experience overwhelming physical and emotional strain, depressive symptoms, sleep deprivation, decline in physical and mental health, reduced quality of life, and increased isolation [7,10,11,14,26,27]. Perceived burden has been positively associated with caregiver depressive symptoms [12,14,28,29]. Depressive symptoms in caregivers, with a reported incidence of 14% [30] to 33% [31], may persist for several years post-stroke. In a study of the long-term effects of caregiving with 235 stroke caregivers when compared with non-caregivers, researchers found that caregivers had more depressive symptoms and poorer life satisfaction and mental health quality of life at 9 months post-stroke, and many of these differences continued for 3 years post-discharge [23].

Lower stroke survivor functioning and higher depressive symptoms are correlated with higher caregiver depressive symptoms and burden, and poorer coping skills and mental health [12,21]. A review of stroke caregiving literature by van Heugten et al [32] indicated that long-term caregiver functioning was influenced by stroke survivor physical and cognitive functioning and behavioral issues; caregiver psychological and emotional health; quality of family relationships; social support; and caregiver demographics. Caregivers of stroke survivors with aphasia may have more difficulties providing care, increased burden and strain, higher depressive symptoms, and other negative stroke-related outcomes [33].

Gaugler [34] conducted a systematic review of 117 studies and reported that caring for stroke survivors who were older, in poorer health, and had greater stroke severity increased the likelihood of poorer emotional and psychological family caregiver outcomes. Caregivers who had “negative problem orientation and less social support” were more likely to have depressive symptoms and poorer self-rated health at 1-year post-stroke. One of the best predictors of caregiver stress and poor health in the first year post-stroke was lack of caregiver preparation [25,34].

Research also suggests that stroke survivor outcomes are influenced by the ability of the family caregiver to provide emotional and instrumental support as well as assistance with BADL/IADL [6,35]. As the caregiver’s health decreases, the stroke survivor’s health and recovery will also likely suffer and ultimately may result in re-hospitalization or nursing home placement. For example, Perrin et al found a consistent reciprocal relationship between caregiver health and stroke survivor functioning, such that the quality of caregiving may be affected by caregiver burden and depressive symptoms, which in turn can impair the functional, psychological, and emotional recovery of the stroke survivor [21]. Studies have also linked poorer caregiver well-being to increased depressive symptoms in stroke survivors [36,37].

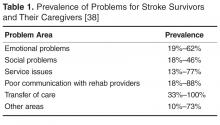

Positive effects of caregiving have also been reported, including a feeling of confidence, satisfaction in providing good quality care [30,39,40], an improved relationship with the care recipient [30,40,41], having greater life appreciation, and feeling needed and appreciated [40]. In a systematic review of 9 studies, improvements in the stroke survivor’s condition was a source of positive caregiving experiences [40]. In 2 studies, two-thirds of caregivers surveyed affirmed all survey items related to positive aspects of caregiving [30,42]. Additionally, studies have demonstrated that caregivers who engaged in emotion- and problem-focused coping strategies had positive caregiving experiences [40]. Haley et al found that by 3 years post-stroke many of the ill effects of caregiving had resolved, suggesting that some caregivers may be successful in adapting to their “new” post-stroke lives [23].

Understanding the difficulties and issues faced by caregivers throughout the trajectory, from immediately following the stroke through the transition home and, ideally, the adaptation of the caregiver to this new life, provides an opportunity for health care professionals to intervene with strategies to support this major life change.

Caregiving Trajectory and Ongoing Needs of Stroke Caregivers

Stroke survivors and their family caregivers rapidly move from intensive therapy and nursing case management while in a facility to little or no assistance following discharge. Despite case management and discharge planning services received while in an institutional setting, the transition from inpatient care to home can be a crisis point for caregivers [9]. They describe having to figure things out for themselves with little or no formal support after discharge [9,43,44], leaving them feeling overwhelmed, exhausted, and abandoned once they return home [9].

These family members rarely make an active choice to become caregivers; rather, they take on the role because they are unable to perceive or access any other suitable alternatives [8,45]. Whatever their circumstances, these devoted family members are particularly vulnerable as they transition into the caregiving role without an adequate support system for assessing and addressing their needs [7–9,46]. Without this assistance, caregivers develop their own solutions and strategies to meet the needs of the care recipient after discharge [47,48]. Unfortunately, these strategies are often ineffective and may result in safety risks for patients (eg, falls, skin breakdown, choking), and care-related injuries (eg, falls, muscle strains, bruises) and increased stress and anxiety for caregivers [48–50].

Caregivers have described unmet needs in many domains including skills training, communicating with providers, resource identification and activation, finances, respite, and emotional support [35,44,48,51,52]. Bakas et al found that in the first 6 months post-discharge, stroke caregivers had needs and concerns related to information, emotions and behaviors, physical care, instrumental care, and personal responses to caregiving [48], and that their information needs change during the course of the patient’s recovery [53]. In a study by Lutz et al [44], caregivers identified multiple areas where they felt they were unprepared to assume the caregiving role post-discharge. These included identifying and activating resources; making home and transportation modifications to improve accessibility; developing skills in providing physical care and therapies; managing medications and behavioral issues; preventing falls; coordinating care across settings; attending to other family responsibilities; and caring for themselves.

In a study of interactions between rehabilitation providers and stroke caregivers, Creasy et al [52] noted that caregivers have needs, which were often not recognized, in the following areas: information; providing emotional support for the stroke survivor and having their own emotional support needs met; being involved in treatment decisions; and being adequately prepared for discharge home. Caregivers’ interaction styles with providers, which ranged from passive to active/directing, affected their abilities to have their needs recognized and addressed. These findings highlight the importance of recognizing the caregiver’s interaction style and tailoring communication strategies accordingly.

Cameron et al [54] noted that caregiver support needs change over time, with needs being highest during the inpatient phase as they prepare for discharge home. Moreover, caregivers who are providing care for stroke survivors with more severe functional limitations need more support over a longer period of time. Recognizing the needs of stroke caregivers, the 2016 Canadian Stroke Best Practice Recommendations on Managing Transitions of Care Following Stroke includes recommendations related to assessing, educating, and supporting stroke family caregivers [55].

Assessing Caregiver Readiness and Related Outcomes

Young et al [58] recommend specific domains for a comprehensive readiness assessment of stroke family caregivers. Caregiver domains include strength of the caregiver/care recipient relationship; caregiver willingness to provide care; pre-existing health conditions, previous responsibilities, caregiving experience, home and transportation accessibility, available resources, emotional response to the stroke, and ability to sustain the caregiving role. This type of readiness assessment should be completed early in the care trajectory, while the stroke survivor is receiving inpatient care, so that care plans can be tailored to address gaps in caregiver preparation prior to discharge. It is especially important for new caregivers and those caring for stroke survivors with significant functional limitations [44]. Currently there are no tools designed to assess a family member’s readiness to assume the caregiver role.

Validated instruments have been developed to assess caregiving outcomes, including preparedness, with caregivers who have been providing care for a period of time. For example, the Mutuality and Preparedness Scales of the Family Caregiver Inventory was developed with caregivers 6 months post-discharge [59] and has been validated with stroke caregivers at 3 months post-discharge [60].

Several validated tools are available to assess the caregiver’s changing needs and the effects of care provision on well-being [8,45,61]. For example, the Caregiver Strain Index [62] has been validated in studies with stroke family caregivers [11,28]. Bakas developed 2 scales to specifically assess stroke caregivers post-discharge. The Bakas Caregiving Outcomes Scale assesses caregiver life changes [63] and the Needs and Concerns Checklist assesses post-discharge caregiver needs [48]. There are many other instruments designed to assess general caregiving outcomes, including depressive symptoms, burden, anxiety, and well-being. For a list relevant tools see Deeken et al [61] and The Selected Caregiver Assessment Measures from the Family Caregiver Alliance [64].

While these scales are helpful for assessing caregivers who are already providing care, they do not capture the gaps in caregiver readiness prior to patient discharge from the institutional setting. Taken together, these studies suggest that assessing readiness and implementing interventions to improve caregiver preparation prior to discharge and assessing and addressing their changing needs over time, from inpatient care to community reintegration, may be important strategies for improving both caregiver and stroke survivor outcomes. These strategies may also facilitate sustainability of the caregiver role over time.

Interventions to Improve Caregiver Outcomes

In a review of 39 articles representing 32 caregiver and dyad intervention studies, researchers from the AHA made 13 evidence-based recommendations. Recommendations with the highest level of evidence indicated that (1) interventions that combined skill-building with psycho-educational programs were better than psycho-educational interventions alone; (2) interventions that are tailored to the individual are preferred over “one-size-fits-all” interventions; (3) face-to-face interventions are preferred, but telephone interventions can be useful when face-to-face is not feasible; and (4) interventions with 5 to 9 sessions are recommended [65]. In a review of 18 studies, Cheng et al confirmed the recommendation that psychoeducational interventions that focused on skill building improved caregiver well-being and reduced stroke survivor heath care utilization [66].

Studies also recommend that families may need family counseling to help them develop positive coping strategies and adjust to their lives after stroke [66]. Stroke survivors and their families experience grief and loss as they begin to realize how the stroke has changed their relationships, roles, responsibilities, and future plans for their lives (eg, work, retirement). While many inpatient rehabilitation facilities may provide services from a neuro-psychologist to discuss post-stroke changes in the brain and possible behavioral and emotional manifestations, referrals for family counseling to address the impact of stroke on the family and community reintegration are seldom provided [9].

Recent interventions have shown promise in improving stroke caregiver outcomes. For example, Bakas et al. completed a randomized controlled trial of an 8-week, nurse-delivered, Telephone Assessment and Skill-Building Kit (TASK) intervention [67]. Caregivers in the intervention group with moderate to severe depressive symptoms at baseline demonstrated significant improvements in depressive symptoms and life changes at 8, 24, and 52 weeks. The TASK shows promise because it can reach caregivers in rural and urban areas at a relatively low cost [67].

Recognizing the need to improve post-acute care for stroke survivors and their family caregivers, several large funded clinical trials are being tested in the US and globally. For example, the ATTEND Trial in India is testing a home-based, caregiver-led rehabilitation intervention [68]. The Comprehensive Post-Acute Stroke Services (COMPASS) study in North Carolina, is a state-wide pragmatic, randomized controlled trial testing a comprehensive community-based patient-centered post-acute care intervention with stroke survivors and their caregivers (www.nccompass-study.org). Results of these and other studies will continue to identify evidence-based strategies to improve care coordination, quality of care, and post-stroke outcomes for stroke survivors and their caregivers

Recommendations for Clinicians

Based on this review we have identified strategies that clinicians can implement across the care continuum that may help reduce caregiver strain and burden, and improve outcomes for family caregivers and the stroke survivors for whom they provide care. The evidence suggests that caregivers need assistance in building skills, not only in providing the care needed by the stroke survivor but also in solving problems as they arise; navigating the multiple systems of care, including understanding options for post-acute care; accessing community resources; communicating effectively with health care and social support providers; and dealing with the emotional effects of stroke [44,52].

Caregivers need help in navigating the multiple providers and systems of care to get the services the stroke survivor needs as well as to secure support services. They need information from trusted sources about stroke prevention and available community resources. Providinga list of resources is often insufficient, especially in the first few weeks or months post-stroke; these caregivers are already overwhelmed with the enormity of the tasks and responsibilities that they have taken on as a caregiver. Instead they need someone who can advocate for them and connect them with the appropriate resources at the right time.

They also need assistance developing and maintaining self-care strategies so they can sustain the caregiving role long-term. Identifying opportunities for respite and helping them activate informal and formal resources, such as other family members, friends, church groups, neighbors, and services from local senior centers, independent living centers, or area agencies on aging can help them identify assistance with the breadth of duties including care of the stroke survivor, meal preparation, transportation, or a supportive listening ear. It is important for the caregiver, in addition to any other close support person as available, to have a facilitated discussion withthe healthcare team to brainstorm activities where assistance may be provided and who might be approached to help.

The timing of providing support and resources is also critical. Becoming a caregiver is a process and often family members who are new to the role need more intense direct assistance and support when the stroke survivor first comes home, but many may need ongoing support over time. Research suggests it can take caregivers up to 3 years to figure out how to manage the new responsibilities, learn to navigate the multiple systems for careand services, establish confidence in their abilities, deal with the emotional upheaval, and to adapt to their new lives [23].

Research indicates the 44% of stroke patients receive no post-acute care. Clinicians also need to advocate for patients to get the most appropriate level of organized, coordinated, and inter-professional post-acute care [5]. This requires that they understand the different levels of post-acute care, including the criteria for admission, the scope and intensity of nursing, therapy, physician and other services provided in each setting, and the associated clinical outcomes. This knowledge is also necessary to enable clinicians to educate stroke survivors and their caregivers on post-acute care so that they understand the process and can effectively self-advocate for the provision of appropriate services as needed.

Approximately 45% of stroke survivors in the US are discharged either to an inpatient rehabilitation facility or SNF for rehabilitation [4]. Patients discharged to an inpatient rehabilitation facility receive a minimum of 3 hours of therapy per day and are cared for 24 hours/day by a staff led by registered nurses (RNs) with rehabilitation expertise. SNFs do not have minimum requirements for hours of therapy, 24-hour RN staffing, nor a requirement for nurses with specialty training in rehabilitation. Pressure to reduce the length of stay in acute care often results in providers transitioning stroke survivors to the post-acute care setting that accepts the patient first. Because SNFs have fewer criteria for admission, they are more likely to rapidly accept a patient for care when compared to an inpatient rehabilitation facility. Providers must determine and make recommendations for the most appropriate level of post-acute care to ensure the stroke patients’ rehabilitation needs can be met in the recommended setting [5,69]. It is also essential that family caregivers have the knowledge and skills to advocate for the appropriate level of post-acute care based on the stroke survivor’s expected recovery trajectory. Research has demonstrated that that stroke survivors admitted to an inpatient rehabilitation facility, when compared to similar patients in a SNF, have better outcomes, including improved function [70] and lower re-hospitalization and death rates [71,72]. The Association of Rehabilitation Nurses provides resources for health care professionals and patients regarding rehabilitation. For more information for professionals about levels of post-acute care, see www.rehabnurse.org/uploads/files/healthpolicy/ARN_Care_Transitions_White_Paper_Journal_Copy_FINAL.pdf [73]. For information for patients and caregivers, see www.restartrecovery.org.

Providers must also be knowledgeable about community resources in order to provide connections to services and agencies that are relevant to the changing needs of the caregiver over time. Initially, caregivers may need assistance in meeting the stroke survivor’s BADL/IADL, and later needs may expand to include support groups, respite, and opportunities for a greater community engagement.

Training in time management provides room in the busy caregiving schedule for self-care for the caregiver. Providers must assist with determining routines that meet the needs of both the caregiver and stroke survivor, as the health of each is dependent on the other. Assistance in developing a wellness program that is feasible for the caregiver to maintain will improve adoption of health promoting practices.

As discussed above, the needs of both the stroke survivor and caregiver vary along the post-stroke trajectory. Therefore, both caregivers and stroke survivors should be assessed intermittently over time: caregivers for evidence of effective coping strategies and confidence in the sustaining the caregiving role, and stroke survivors for improvement in their functional abilities and compensatory strategies in BADL/IADL. The opportunity for the stroke survivor to assume household tasks that decrease the caregiver burden, in addition to providing a greater sense of purpose for the stroke survivor, must be explored. For example, the stroke survivor may be able to assist with activities such as meal planning and components of meal preparation or light housekeeping utilizing adaptive devices as needed.

Additional research is necessary to understand how the needs of caregivers change over time, the appropriate timing of reassessment, and the evaluation of interventions to facilitate the transition into this role, while preventing the adverse effects of caregiving on the health of the caregiver and stroke survivor during this transition period.

Conclusion

There is clear evidence that stroke caregiving can have detrimental effects on the physical, mental, and emotional health of caregivers, and that these effects are sustained over time. Evidence also indicates that caregivers who are not well-prepared to assume the caregiving role are more likely to experience negative outcomes. Studies suggest that the time of transition from inpatient care to home is a time of crisis for caregivers and that their support needs are high during this time. However, research also indicates that while needs may change over time, caregivers need ongoing support, especially if they are providing care for a stroke survivor who has moderate to severe physical, cognitive, and/or communication limitations.

In order to better understand the needs of stroke caregivers, a pre-discharge assessment of their readiness to provide care should be conducted so that interventions can be tailored to address their needs to minimize negative effects of a poorly planned transition [69]. Currently, there are assessment tools that can be used with caregivers post-discharge to assess their self-reported needs (after they have an understanding of the role) and caregiving outcomes. Research is needed to develop a valid and reliable tool thatpre-emptively assesses the gaps in caregiver readiness that can be utilized prior to the transition from the institutional setting to home. This will enable the identification and evaluation of primary prevention strategies to improve caregiver preparation so that the adaption to the new caregiving role can be expedited, minimizing the adverse health effects on both the caregiver and stroke survivor.

Providers must be aware of the changing needs of stroke survivors and tailor plans of care accordingly, using evidenced-based interventions. Policy makers must consider research on the long term effects of caregiving and consider legislation to support the health and respite needs of the growing population of caregivers. This will contribute to attaining the 3 aims of the National Quality Strategy: improving quality of care, improving health, and reducing health care system costs [74].

Corresponding author: Barbara J. Lutz, PhD, 601 S. College Rd., Wilmington, NC 28403, [email protected].

Financial disclosures: None.

1. Mozaffarian D, Benjamin EJ, Go AS, et al. on behalf of the American Heart Association Statistics Committee & Stroke Statistics Subcommittee. Heart disease and stroke statistics - 2016 update: A report from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2016;132:e38–e360.

2. Feigin VL, Krishnamurthi RV, Parmar P, et al. Update on the global burden of ischemic and hemorrhagic stroke in 1990-2013: The GBD 2013 Study. Neuroepidemiology 2015;45:161–76.

3. Hall MJ, Levant S, DeFrances CJ. Hospitalization for stroke in U.S. hospitals, 1989-2009. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Heatlh Statistics; 2012.

4. Prvu Bettger J, McCoy L, Smith EE, et al. Contemporary trends and predictors of postacute service use and routine discharge home after stroke. J Am Heart Assoc 2015;4(2).

5. Winstein CJ, Stein J, Arena R, et al. Guidelines for adult stroke rehabilitation and recovery: a guideline for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke 2016;47:e98–e169.

6. Talley RC, Crews JE. Framing the public health of caregiving. Am J Public Health 2007;97:224–8.

7. van Exel NJ, Koopmanschap MA, van den Berg B, et al. Burden of informal caregiving for stroke patients: odentification of caregivers at risk of adverse health effects. Cerebrovasc Dis 2005;19:11–7.

8. van Exel NJ, Scholte op Reimer WJ, Brouwer WB, et al. Instruments for assessing the burden of informal caregiving for stroke patients in clinical practice: a comparison of CSI, CRA, SCQ and self-rated burden. Clin Rehabil 2004;18:203–14.

9. Lutz BJ, Young ME, Cox KJ, et al. The crisis of stroke: experiences of patients and their family caregivers. Top Stroke Rehabil 2011;18:786–97.

10. McCullagh E, Brigstocke G, Donaldson N, Kalra L. Determinants of caregiving burden and quality of life in caregivers of stroke patients. Stroke 2005;36:2181–6.

11. van Exel NJ, Brouwer WB, van den Berg B, et al. What really matters: an inquiry into the relative importance of dimensions of informal caregiver burden. Clin Rehabil 2004;18:683–93.

12. Perrin PB, Heesacker M, Hinojosa MS et al. Identifying at-risk, ethnically diverse stroke caregivers for counseling: a longitudinal study of mental health. Rehabil Psychol 2009;54:138–49.

13. Greenwood N, Mackenzie A, Cloud GC, Wilson N. Informal carers of stroke survivors--factors influencing carers: a systematic review of quantitative studies. Disabil Rehabil 2008;30:1329–49.

14. Camak DJ. Addressing the burden of stroke caregivers: a literature review. J Clin Nurs 2015;24:2376–82.

15. White CL, Barrientos R, Dunn K. Dimensions of uncertainty after stroke: perspectives of the stroke survivor and family caregiver. J Neurosci Nurs 2014;46:233–40.

16. Saban KL, Sherwood PR, DeVon HA, Hynes DM. Measures of psychological stress and physical health in family caregivers of stroke survivors: a literature review. J Neurosci Nurs 2010;42:128–38.

17. Kruithof WJ, Post, MWM, van Mierlo M, et al. Caregiver burden and emotional problems in partners of stroke patients at two months and one year post-stroke: determinants and prediction. Patient Educ Couns 2016. Forthcoming.

18. Sarre S, Redlich C, Tinker A, et al. A systematic review of qualitative studies on adjusting after stroke: lessons for the study of resilience. Disabil Rehabil 2014;36:716–26.

19. Cameron JI, Naglie G, Dick T, et al. Are we meeting the changing needs of family caregivers to stroke survivors across the care continuum? A systematic review of the caregiver intervention literature. Stroke 2012;43:E143-E.

20. Miller EL, Murray L, Richards L, et al. Comprehensive overview of nursing and interdisciplinary rehabilitation care of the stroke ptient: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Stroke 2010;41:2402–48.

21. Perrin PB, Heesacker M, Stidham BS, et al. Structural equation modeling of the relationship between caregiver psychosocial variables and functioning of individuals with stroke. Rehabil Psychol 2008;53:54–62.

22. Roth DL, Perkins M, Wadley VG, et al. Family caregiving and emotional strain: associations with quality of life in a large national sample of middle-aged and older adults. Qual Life Res 2009;18:679–88.

23. Haley WE, Roth DL, Hovater M, Clay OJ. Long-term impact of stroke on family caregiver well-being: a population-based case-control study. Neurology 2015;84:1323–9.

24. Greenwood N, Mackenzie A. Informal caring for stroke survivors: meta-ethnographic review of qualitative literature. Maturitas 2010;66:268–76.

25. Ostwald SK, Bernal MP, Cron SG, Godwin KM. Stress experienced by stroke survivors and spousal caregivers during the first year after discharge from inpatient rehabilitation. Top Stroke Rehabil 2009;16:93–104.

26. Brereton L, Carroll C, Barnston S. Interventions for adult family carers of people who have had a stroke: a systematic review. Clin Rehabil 2007;21:867–84.

27. Greenwood N, Mackenzie A, Cloud G, Wilson N. Loss of autonomy, control and independence when caring: a qualitative study of informal carers of stroke survivors in the first three months after discharge. Disabil Rehabil 2009:1–9.

28. Visser-Meily A, Post M, van de Port I, et al. Psychosocial functioning of spouses of patients with stroke from initial inpatient rehabilitation to 3 years poststroke: course and relations with coping strategies. Stroke 2009;40:1399–404.

29. Visser-Meily A, Post M, van de Port I, et al. Psychosocial functioning of spouses in the chronic phase after stroke: improvement or deterioration between 1 and 3 years after stroke? Patient Educ Couns 2008;73:153–8.

30. Haley WE, Allen JY, Grant JS, et al. Problems and benefits reported by stroke family caregivers: results from a prospective epidemiological study. Stroke 2009;40:2129–33.

31. Berg A, Palomaki H, Lonnqvist J, et al. Depression among caregivers of stroke survivors. Stroke 2005;36:639–43.

32. van Heugten C, Visser-Meily A, Post M, Lindeman E. Care for carers of stroke patients: evidence-based clinical practice guidelines. J Rehabil Med 2006;38:153–8.

33. Bakas T, Kroenke K, Plue LD, et al. Outcomes among family caregivers of aphasic versus nonaphasic stroke survivors. Rehabil Nurs 2006;31:33–42.

34. Gaugler JE. The longitudinal ramifications of stroke caregiving: a systematic review. Rehabil Psychol 2010;55:108–25.

35. Andrew NE, Kilkenny MF, Naylor R, et al. The relationship between caregiver impacts and the unmet needs of survivors of stroke. Patient Prefer Adher 2015;9:1065–73.

36. Chung ML, Bakas T, Plue LD, Williams LS. Effects of self-esteem, optimism, and perceived control on depressive symptoms in stroke survivor-spouse dyads. J Cardiovasc Nurs 2016;31:E8–E16.

37. Grant JS, Clay OJ, Keltner NL, et al. Does caregiver well-being predict stroke survivor depressive symptoms? a mediation analysis. Top Stroke Rehabil 2013;20:44–51.

38. Murray J, Young J, Forster A, Ashworth R. Developing a primary care-based stroke model: the prevalence of longer-term problems experienced by patients and carers. Br J Gen Pract 2003;53:803–7.

39. Pierce LL, Steiner V, Govoni A, et al. Two sides to the caregiving story. Top Stroke Rehabil 2007;14:13–20.

40. Mackenzie A, Greenwood N. Positive experiences of caregiving in stroke: a systematic review. Disabil Rehabil 2012;34:1413–22.

41. Parag V, Hackett ML, Yapa CM, et al. The impact of stroke on unpaid caregivers: results from The Auckland Regional Community Stroke study, 2002-2003. Cerebrovasc Dis (Basel, Switzerland) 2008;25:548–54.

42. Kruithof WJ, Post MWM, Visser-Meily JMA. Measuring negative and positive caregiving experiences: a psychometric analysis of the Caregiver Strain Index Expanded. Clin Rehabil 2015;29:1224–33.

43. Lutz BJ. Determinants of discharge destination for stroke patients. Rehabil Nurs 2004;29:154–63.

44. Lutz BJ, Young ME, Creasy KR, et al. Improving stroke caregiver readiness for transition from inpatinet rehabilitation to home. Gerontologist 2016. Forthcoming.

45. Visser-Meily JM, Post MW, Riphagen II, Lindeman E. Measures used to assess burden among caregivers of stroke patients: a review. Clin Rehabil 2004;18:601–23.

46. Moon M. The unprepared caregiver. Gerontologist 2016 Apr 21.

47. Pierce LL, Steiner V, Govoni AL, et al. Internet-based support for rural caregivers of persons with stroke shows promise. Rehabil Nurs 2004;29:95–9,103.

48. Bakas T, Austin JK, Okonkwo KF, et al. Needs, concerns, strategies, and advice of stroke caregivers the first 6 months after discharge. J Neurosci Nurs 2002;34:242–51.

49. Lutz BJ, Chumbler NR, Lyles T, et al. Testing a home-telehealth programme for US veterans recovering from stroke and their family caregivers. Disabil Rehabil 2009;31:402–9.

50. Hayes J, Chapman P, Young LJ, Rittman M. The prevalence of injury for stroke caregivers and associated risk factors. Top Stroke Rehabil 2009;16:300–7.

51. Cameron JI, Gignac MA. “Timing It Right”: a conceptual framework for addressing the support needs of family caregivers to stroke survivors from the hospital to the home. Patient Educ Couns 2008;70:305–14.

52. Creasy KR, Lutz BJ, Young ME, et al. The impact of interactions with providers on stroke caregivers’ needs. Rehabil Nurs 2013;38:88–98.

53. Bakas T, Farran CJ, Austin JK, et al. Stroke caregiver outcomes from the Telephone Assessment and Skill-Building Kit (TASK). Top Stroke Rehabil 2009;16:105–21.

54. Cameron JI, Naglie G, Silver FL, Gignac MA. Stroke family caregivers’ support needs change across the care continuum: a qualitative study using the timing it right framework. Disabil Rehabil 2013;35:315–24.

55. Cameron JI, O’Connell C, Foley N, et al. Canadian Stroke Best Practice Recommendations: Managing transitions of care following Stroke. Guidelines Update 2016. Int J Stroke. 2016.

56. Family Caregiver Alliance. Caregivers Count Too! A toolkit to help practitioners assess the needs of family caregivers. San Francisco: 2006. Accessed 16 Aug 2016 at www.caregiver.org/caregivers-count-too-toolkit.

57. Messecar DC. Nursing standard of practice protocol: family caregiving [Internet]. Accessed at www.consultgeri.org/geriatric-topics/family-caregiving.

58. Young ME, Lutz BJ, Creasy KR et al. A comprehensive assessment of family caregivers of stroke survivors during inpatient rehabilitation. Disabil Rehabil 2014;36:1892–902.

59. Archbold PG, Stewart BJ, Greenlick MR, Harvath T. Mutuality and preparedness as predictors of caregiver role strain. Res Nurs Health 1990;13:375–84.

60. Pucciarelli G, Savini S, Byun E, et al. Psychometric properties of the Caregiver Preparedness Scale in caregivers of stroke survivors. Heart & Lung 2014;43:555–60.

61. Deeken JF, Taylor KL, Mangan P et al. Care for the caregivers: a review of self-report instruments developed to measure the burden, needs, and quality of life of informal caregivers. J Pain Symptom Manage 2003;26:922–53.

62. Haley WE, Roth DL, Howard G, Safford MM. Caregiving strain and estimated risk for stroke and coronary heart disease among spouse caregivers: differential effects by race and sex. Stroke 2010;41:331–6.

63. Bakas T, Champion V, Perkins SM, et al. Psychometric testing of the revised 15-item Bakas Caregiving Outcomes Scale. Nurs Res 2006;55:346–55.

64. Family Caregiver Alliance. Selected caregiver assessment measures: A resource inventory for practitioners. 2d ed. Accessed at www.caregiver.org/selected-caregiver-assessment-measures-resource-inventory-practitioners-2012.

65. Bakas T, Clark PC, Kelly-Hayes M, et al. Evidence for stroke family caregiver and dyad interventions: a statement for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke 2014;45:2836–52.

66. Cheng HY, Chair SY, Chau JPC. The effectiveness of psychosocial interventions for stroke family caregivers and stroke survivors: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Patient Educ Couns 2014;95:30–44.

67. Bakas T, Austin JK, Habermann B, et al. Telephone assessment and skill-building kit for stroke caregivers a randomized controlled clinical trial. Stroke 2015;46:3478–87.

68. Alim M, Lindley R, Felix C, et al. Family-led rehabilitation after stroke in India: the ATTEND trial, study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials 2016;17:13.

69. Camicia M, Lutz B. Nursing’s role in successful transitions across settings. Stroke 2016. Forthcoming.

70. Chan L, Sandel ME, Jette AM, et al. Does postacute care site matter? A longitudinal study assessing functional recovery after a stroke. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2013;94:622–9.

71. Kind AJ, Smith MA, Pandhi N, et al. Bouncing-back: rehospitalization in patients with complicated transitions in the first thirty days after hospital discharge for acute stroke. Home Health Care Serv Q 2007;26:37–55.

72. Bettger JP, Liang L, Xian Y, et al. Inpatient rehabilitation facility care reduces the likelihood of death and rehospitalization after stroke compared with skilled nursing facility care [abstract]. Stroke 2015; A146.

73. Camicia M, Black T, Farrell J, et al. The essential role of the rehabilitation nurse in facilitating care transitions: a white paper by the Association of Rehabilitation Nurses. Rehabil Nurs 2014;39:3–15.

74. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid. CMS quality strategy 2016. Accessed at www.cms.gov/medicare/quality-initiatives-patient-assessment-instruments/qualityinitiativesgeninfo/downloads/cms-quality-strategy.pdf.

From the School of Nursing, University of North Carolina-Wilmington, Wilmington, NC (Dr. Lutz), and the Kaiser Foundation Rehabilitation Center, Kaiser Permanente, Vallejo, CA (Ms. Camicia).

Abstract

- Objectives: To describe issues faced by stroke family caregivers, discuss evidence-based interventions to improve caregiver outcomes, and provide recommendations for clinicians caring for stroke survivors and their family caregivers.

- Methods: Literature review.

- Results: Caregiver health is linked to the stroke survivor’s degree of functional recovery; the more severe the level of disability, the more likely the caregiver will experience higher levels of strain, increased depression, and poor health. Inadequate caregiver preparation contributes to poorer outcomes. Caregivers describe many unmet needs including skills training; communicating with providers; resource identification and activation; finances; respite; and emotional support. Caregivers need to be assessed for gaps in preparation to provide care. Interventions are recommended that combine skill-building and psycho-educational strategies; are tailored to individual caregiver needs; are face-to-face when feasible; and include 5 to 9 sessions. Family counseling may also be indicated. Intermittent assessment of caregiving outcomes should be conducted so that changing needs can be addressed.

- Conclusions: Stroke caregiving affects the caregiver’s physical, mental, and emotional health, and these effects are sustained over time. Poorly prepared caregivers are more likely to experience negative outcomes and their needs are high during the transition from inpatient care to home. Ongoing support is also important, especially for caregivers who are caring for a stroke survivor with moderate to severe functional limitations. In order to better address unmet needs of stroke caregivers, intermittent assessments should be conducted so that interventions can be tailored to their changing needs over time.

Key words: stroke; family caregivers; care transitions; patient-centered care.

Stroke is a leading cause of major disability in the United States [1] and around the world [2]. Of the estimated 6.6 million stroke survivors living in the US, more than 4.5 million have some level of disability following stroke [1]. In 2009, more than 970,000 persons were hospitalized with stroke in the US with an average length of stay of 5.3 days [3]. Approximately 44% of stroke survivors are discharged home directly from acute care without post-acute care [4]. Only about 25% of stroke survivors receive care in inpatient rehabilitation facilities [4] even though the American Heart Association (AHA) stroke rehabilitation guidelines recommend this level of care for qualified patients [5]. Regardless of the care trajectory, when stroke survivors return home they frequently require assistance with basic and instrumental activities of daily living (BADL/IADL), usually provided by family members who often feel unprepared and overwhelmed by the demands and responsibilities of this caregiving role.

The deleterious effects of caregiving have been identified as a major public health concern [6]. A robust body of literature has established that caregivers are often adversely affected by the demands of their caregiving role. However, much of this literature focuses on caregivers for persons with dementia. Needs of stroke caregivers are categorically different from caregivers of persons with dementia in that stroke is an unpredictable, life-disrupting, crisis event that occurs suddenly leaving family members with insufficient time to prepare for the new roles and caregiving responsibilities. The patient typically transitions from being cared for by multiple providers in an acute care, inpatient rehabilitation facility, or skilled nursing facility (SNF)—24 hours a day, 7 days a week—to relying fully on one person (most often a spouse or adult child) who may not be ready to handle the overwhelming demands and constant vigilance required for adequate care at home. Studies have repeatedly demonstrated the damaging health effects of caregiving. Caregivers describe feeling isolated, abandoned, and alone [7–9], and what frequently follows is a predictable trajectory of depression and deteriorating health and well-being [7,10–13]. The purpose of this article is to describe difficulties and issues faced by family members who are caring for a loved one following stroke, discuss evidence-based interventions designed to improve stroke caregiver outcomes, and provide recommendations for clinicians who care for stroke survivors and their family caregivers post-stroke.

Difficulties and Issues Faced by Caregivers

With an aging population and increasing incidence of stroke, it is imperative that we identify and address the ongoing needs of stroke survivors and their family caregivers in the post-stroke recovery period. Multiple studies acknowledge that stroke is a life-changing event for patients and their family members [9,14] that often results in overwhelming feelings of uncertainty, fear [15], grief, and loss [9]. Stroke also can have long-term effects on the health of stroke survivors and their family caregivers. Studies have identified the effects of caregiving on the health of caregivers and subsequent links between stroke survivor and caregiver outcomes over time [12,16,17]; the ongoing needs of stroke caregivers post-discharge [18,19]; and the importance of assessing caregiver preparedness and subsequent caregiving outcomes [5,20].

Effects of Caregiving on the Health of Caregivers and Stroke Survivors

Research on stroke caregiving consistently indicates that caregiver health is inextricably linked to the stroke survivor’s degree of physical, cognitive, psychological, and emotional recovery. The more severe the patient’s level of disability, the more likely the caregiver will experience higher levels of strain, increased depression, and poor health outcomes [21]. Studies also indicate that certain caregiver characteristics, such as being female or having lower educational level, pre-existing health conditions [7,22,23], poor family functioning, lack of social support [22,24], or lack of preparation [25], are all risk factors for poorer caregiver outcomes.

Stroke family caregivers often experience overwhelming physical and emotional strain, depressive symptoms, sleep deprivation, decline in physical and mental health, reduced quality of life, and increased isolation [7,10,11,14,26,27]. Perceived burden has been positively associated with caregiver depressive symptoms [12,14,28,29]. Depressive symptoms in caregivers, with a reported incidence of 14% [30] to 33% [31], may persist for several years post-stroke. In a study of the long-term effects of caregiving with 235 stroke caregivers when compared with non-caregivers, researchers found that caregivers had more depressive symptoms and poorer life satisfaction and mental health quality of life at 9 months post-stroke, and many of these differences continued for 3 years post-discharge [23].

Lower stroke survivor functioning and higher depressive symptoms are correlated with higher caregiver depressive symptoms and burden, and poorer coping skills and mental health [12,21]. A review of stroke caregiving literature by van Heugten et al [32] indicated that long-term caregiver functioning was influenced by stroke survivor physical and cognitive functioning and behavioral issues; caregiver psychological and emotional health; quality of family relationships; social support; and caregiver demographics. Caregivers of stroke survivors with aphasia may have more difficulties providing care, increased burden and strain, higher depressive symptoms, and other negative stroke-related outcomes [33].

Gaugler [34] conducted a systematic review of 117 studies and reported that caring for stroke survivors who were older, in poorer health, and had greater stroke severity increased the likelihood of poorer emotional and psychological family caregiver outcomes. Caregivers who had “negative problem orientation and less social support” were more likely to have depressive symptoms and poorer self-rated health at 1-year post-stroke. One of the best predictors of caregiver stress and poor health in the first year post-stroke was lack of caregiver preparation [25,34].

Research also suggests that stroke survivor outcomes are influenced by the ability of the family caregiver to provide emotional and instrumental support as well as assistance with BADL/IADL [6,35]. As the caregiver’s health decreases, the stroke survivor’s health and recovery will also likely suffer and ultimately may result in re-hospitalization or nursing home placement. For example, Perrin et al found a consistent reciprocal relationship between caregiver health and stroke survivor functioning, such that the quality of caregiving may be affected by caregiver burden and depressive symptoms, which in turn can impair the functional, psychological, and emotional recovery of the stroke survivor [21]. Studies have also linked poorer caregiver well-being to increased depressive symptoms in stroke survivors [36,37].

Positive effects of caregiving have also been reported, including a feeling of confidence, satisfaction in providing good quality care [30,39,40], an improved relationship with the care recipient [30,40,41], having greater life appreciation, and feeling needed and appreciated [40]. In a systematic review of 9 studies, improvements in the stroke survivor’s condition was a source of positive caregiving experiences [40]. In 2 studies, two-thirds of caregivers surveyed affirmed all survey items related to positive aspects of caregiving [30,42]. Additionally, studies have demonstrated that caregivers who engaged in emotion- and problem-focused coping strategies had positive caregiving experiences [40]. Haley et al found that by 3 years post-stroke many of the ill effects of caregiving had resolved, suggesting that some caregivers may be successful in adapting to their “new” post-stroke lives [23].

Understanding the difficulties and issues faced by caregivers throughout the trajectory, from immediately following the stroke through the transition home and, ideally, the adaptation of the caregiver to this new life, provides an opportunity for health care professionals to intervene with strategies to support this major life change.

Caregiving Trajectory and Ongoing Needs of Stroke Caregivers

Stroke survivors and their family caregivers rapidly move from intensive therapy and nursing case management while in a facility to little or no assistance following discharge. Despite case management and discharge planning services received while in an institutional setting, the transition from inpatient care to home can be a crisis point for caregivers [9]. They describe having to figure things out for themselves with little or no formal support after discharge [9,43,44], leaving them feeling overwhelmed, exhausted, and abandoned once they return home [9].

These family members rarely make an active choice to become caregivers; rather, they take on the role because they are unable to perceive or access any other suitable alternatives [8,45]. Whatever their circumstances, these devoted family members are particularly vulnerable as they transition into the caregiving role without an adequate support system for assessing and addressing their needs [7–9,46]. Without this assistance, caregivers develop their own solutions and strategies to meet the needs of the care recipient after discharge [47,48]. Unfortunately, these strategies are often ineffective and may result in safety risks for patients (eg, falls, skin breakdown, choking), and care-related injuries (eg, falls, muscle strains, bruises) and increased stress and anxiety for caregivers [48–50].

Caregivers have described unmet needs in many domains including skills training, communicating with providers, resource identification and activation, finances, respite, and emotional support [35,44,48,51,52]. Bakas et al found that in the first 6 months post-discharge, stroke caregivers had needs and concerns related to information, emotions and behaviors, physical care, instrumental care, and personal responses to caregiving [48], and that their information needs change during the course of the patient’s recovery [53]. In a study by Lutz et al [44], caregivers identified multiple areas where they felt they were unprepared to assume the caregiving role post-discharge. These included identifying and activating resources; making home and transportation modifications to improve accessibility; developing skills in providing physical care and therapies; managing medications and behavioral issues; preventing falls; coordinating care across settings; attending to other family responsibilities; and caring for themselves.

In a study of interactions between rehabilitation providers and stroke caregivers, Creasy et al [52] noted that caregivers have needs, which were often not recognized, in the following areas: information; providing emotional support for the stroke survivor and having their own emotional support needs met; being involved in treatment decisions; and being adequately prepared for discharge home. Caregivers’ interaction styles with providers, which ranged from passive to active/directing, affected their abilities to have their needs recognized and addressed. These findings highlight the importance of recognizing the caregiver’s interaction style and tailoring communication strategies accordingly.

Cameron et al [54] noted that caregiver support needs change over time, with needs being highest during the inpatient phase as they prepare for discharge home. Moreover, caregivers who are providing care for stroke survivors with more severe functional limitations need more support over a longer period of time. Recognizing the needs of stroke caregivers, the 2016 Canadian Stroke Best Practice Recommendations on Managing Transitions of Care Following Stroke includes recommendations related to assessing, educating, and supporting stroke family caregivers [55].

Assessing Caregiver Readiness and Related Outcomes

Young et al [58] recommend specific domains for a comprehensive readiness assessment of stroke family caregivers. Caregiver domains include strength of the caregiver/care recipient relationship; caregiver willingness to provide care; pre-existing health conditions, previous responsibilities, caregiving experience, home and transportation accessibility, available resources, emotional response to the stroke, and ability to sustain the caregiving role. This type of readiness assessment should be completed early in the care trajectory, while the stroke survivor is receiving inpatient care, so that care plans can be tailored to address gaps in caregiver preparation prior to discharge. It is especially important for new caregivers and those caring for stroke survivors with significant functional limitations [44]. Currently there are no tools designed to assess a family member’s readiness to assume the caregiver role.

Validated instruments have been developed to assess caregiving outcomes, including preparedness, with caregivers who have been providing care for a period of time. For example, the Mutuality and Preparedness Scales of the Family Caregiver Inventory was developed with caregivers 6 months post-discharge [59] and has been validated with stroke caregivers at 3 months post-discharge [60].

Several validated tools are available to assess the caregiver’s changing needs and the effects of care provision on well-being [8,45,61]. For example, the Caregiver Strain Index [62] has been validated in studies with stroke family caregivers [11,28]. Bakas developed 2 scales to specifically assess stroke caregivers post-discharge. The Bakas Caregiving Outcomes Scale assesses caregiver life changes [63] and the Needs and Concerns Checklist assesses post-discharge caregiver needs [48]. There are many other instruments designed to assess general caregiving outcomes, including depressive symptoms, burden, anxiety, and well-being. For a list relevant tools see Deeken et al [61] and The Selected Caregiver Assessment Measures from the Family Caregiver Alliance [64].

While these scales are helpful for assessing caregivers who are already providing care, they do not capture the gaps in caregiver readiness prior to patient discharge from the institutional setting. Taken together, these studies suggest that assessing readiness and implementing interventions to improve caregiver preparation prior to discharge and assessing and addressing their changing needs over time, from inpatient care to community reintegration, may be important strategies for improving both caregiver and stroke survivor outcomes. These strategies may also facilitate sustainability of the caregiver role over time.

Interventions to Improve Caregiver Outcomes

In a review of 39 articles representing 32 caregiver and dyad intervention studies, researchers from the AHA made 13 evidence-based recommendations. Recommendations with the highest level of evidence indicated that (1) interventions that combined skill-building with psycho-educational programs were better than psycho-educational interventions alone; (2) interventions that are tailored to the individual are preferred over “one-size-fits-all” interventions; (3) face-to-face interventions are preferred, but telephone interventions can be useful when face-to-face is not feasible; and (4) interventions with 5 to 9 sessions are recommended [65]. In a review of 18 studies, Cheng et al confirmed the recommendation that psychoeducational interventions that focused on skill building improved caregiver well-being and reduced stroke survivor heath care utilization [66].

Studies also recommend that families may need family counseling to help them develop positive coping strategies and adjust to their lives after stroke [66]. Stroke survivors and their families experience grief and loss as they begin to realize how the stroke has changed their relationships, roles, responsibilities, and future plans for their lives (eg, work, retirement). While many inpatient rehabilitation facilities may provide services from a neuro-psychologist to discuss post-stroke changes in the brain and possible behavioral and emotional manifestations, referrals for family counseling to address the impact of stroke on the family and community reintegration are seldom provided [9].

Recent interventions have shown promise in improving stroke caregiver outcomes. For example, Bakas et al. completed a randomized controlled trial of an 8-week, nurse-delivered, Telephone Assessment and Skill-Building Kit (TASK) intervention [67]. Caregivers in the intervention group with moderate to severe depressive symptoms at baseline demonstrated significant improvements in depressive symptoms and life changes at 8, 24, and 52 weeks. The TASK shows promise because it can reach caregivers in rural and urban areas at a relatively low cost [67].

Recognizing the need to improve post-acute care for stroke survivors and their family caregivers, several large funded clinical trials are being tested in the US and globally. For example, the ATTEND Trial in India is testing a home-based, caregiver-led rehabilitation intervention [68]. The Comprehensive Post-Acute Stroke Services (COMPASS) study in North Carolina, is a state-wide pragmatic, randomized controlled trial testing a comprehensive community-based patient-centered post-acute care intervention with stroke survivors and their caregivers (www.nccompass-study.org). Results of these and other studies will continue to identify evidence-based strategies to improve care coordination, quality of care, and post-stroke outcomes for stroke survivors and their caregivers

Recommendations for Clinicians

Based on this review we have identified strategies that clinicians can implement across the care continuum that may help reduce caregiver strain and burden, and improve outcomes for family caregivers and the stroke survivors for whom they provide care. The evidence suggests that caregivers need assistance in building skills, not only in providing the care needed by the stroke survivor but also in solving problems as they arise; navigating the multiple systems of care, including understanding options for post-acute care; accessing community resources; communicating effectively with health care and social support providers; and dealing with the emotional effects of stroke [44,52].

Caregivers need help in navigating the multiple providers and systems of care to get the services the stroke survivor needs as well as to secure support services. They need information from trusted sources about stroke prevention and available community resources. Providinga list of resources is often insufficient, especially in the first few weeks or months post-stroke; these caregivers are already overwhelmed with the enormity of the tasks and responsibilities that they have taken on as a caregiver. Instead they need someone who can advocate for them and connect them with the appropriate resources at the right time.

They also need assistance developing and maintaining self-care strategies so they can sustain the caregiving role long-term. Identifying opportunities for respite and helping them activate informal and formal resources, such as other family members, friends, church groups, neighbors, and services from local senior centers, independent living centers, or area agencies on aging can help them identify assistance with the breadth of duties including care of the stroke survivor, meal preparation, transportation, or a supportive listening ear. It is important for the caregiver, in addition to any other close support person as available, to have a facilitated discussion withthe healthcare team to brainstorm activities where assistance may be provided and who might be approached to help.

The timing of providing support and resources is also critical. Becoming a caregiver is a process and often family members who are new to the role need more intense direct assistance and support when the stroke survivor first comes home, but many may need ongoing support over time. Research suggests it can take caregivers up to 3 years to figure out how to manage the new responsibilities, learn to navigate the multiple systems for careand services, establish confidence in their abilities, deal with the emotional upheaval, and to adapt to their new lives [23].

Research indicates the 44% of stroke patients receive no post-acute care. Clinicians also need to advocate for patients to get the most appropriate level of organized, coordinated, and inter-professional post-acute care [5]. This requires that they understand the different levels of post-acute care, including the criteria for admission, the scope and intensity of nursing, therapy, physician and other services provided in each setting, and the associated clinical outcomes. This knowledge is also necessary to enable clinicians to educate stroke survivors and their caregivers on post-acute care so that they understand the process and can effectively self-advocate for the provision of appropriate services as needed.

Approximately 45% of stroke survivors in the US are discharged either to an inpatient rehabilitation facility or SNF for rehabilitation [4]. Patients discharged to an inpatient rehabilitation facility receive a minimum of 3 hours of therapy per day and are cared for 24 hours/day by a staff led by registered nurses (RNs) with rehabilitation expertise. SNFs do not have minimum requirements for hours of therapy, 24-hour RN staffing, nor a requirement for nurses with specialty training in rehabilitation. Pressure to reduce the length of stay in acute care often results in providers transitioning stroke survivors to the post-acute care setting that accepts the patient first. Because SNFs have fewer criteria for admission, they are more likely to rapidly accept a patient for care when compared to an inpatient rehabilitation facility. Providers must determine and make recommendations for the most appropriate level of post-acute care to ensure the stroke patients’ rehabilitation needs can be met in the recommended setting [5,69]. It is also essential that family caregivers have the knowledge and skills to advocate for the appropriate level of post-acute care based on the stroke survivor’s expected recovery trajectory. Research has demonstrated that that stroke survivors admitted to an inpatient rehabilitation facility, when compared to similar patients in a SNF, have better outcomes, including improved function [70] and lower re-hospitalization and death rates [71,72]. The Association of Rehabilitation Nurses provides resources for health care professionals and patients regarding rehabilitation. For more information for professionals about levels of post-acute care, see www.rehabnurse.org/uploads/files/healthpolicy/ARN_Care_Transitions_White_Paper_Journal_Copy_FINAL.pdf [73]. For information for patients and caregivers, see www.restartrecovery.org.

Providers must also be knowledgeable about community resources in order to provide connections to services and agencies that are relevant to the changing needs of the caregiver over time. Initially, caregivers may need assistance in meeting the stroke survivor’s BADL/IADL, and later needs may expand to include support groups, respite, and opportunities for a greater community engagement.

Training in time management provides room in the busy caregiving schedule for self-care for the caregiver. Providers must assist with determining routines that meet the needs of both the caregiver and stroke survivor, as the health of each is dependent on the other. Assistance in developing a wellness program that is feasible for the caregiver to maintain will improve adoption of health promoting practices.

As discussed above, the needs of both the stroke survivor and caregiver vary along the post-stroke trajectory. Therefore, both caregivers and stroke survivors should be assessed intermittently over time: caregivers for evidence of effective coping strategies and confidence in the sustaining the caregiving role, and stroke survivors for improvement in their functional abilities and compensatory strategies in BADL/IADL. The opportunity for the stroke survivor to assume household tasks that decrease the caregiver burden, in addition to providing a greater sense of purpose for the stroke survivor, must be explored. For example, the stroke survivor may be able to assist with activities such as meal planning and components of meal preparation or light housekeeping utilizing adaptive devices as needed.

Additional research is necessary to understand how the needs of caregivers change over time, the appropriate timing of reassessment, and the evaluation of interventions to facilitate the transition into this role, while preventing the adverse effects of caregiving on the health of the caregiver and stroke survivor during this transition period.

Conclusion

There is clear evidence that stroke caregiving can have detrimental effects on the physical, mental, and emotional health of caregivers, and that these effects are sustained over time. Evidence also indicates that caregivers who are not well-prepared to assume the caregiving role are more likely to experience negative outcomes. Studies suggest that the time of transition from inpatient care to home is a time of crisis for caregivers and that their support needs are high during this time. However, research also indicates that while needs may change over time, caregivers need ongoing support, especially if they are providing care for a stroke survivor who has moderate to severe physical, cognitive, and/or communication limitations.

In order to better understand the needs of stroke caregivers, a pre-discharge assessment of their readiness to provide care should be conducted so that interventions can be tailored to address their needs to minimize negative effects of a poorly planned transition [69]. Currently, there are assessment tools that can be used with caregivers post-discharge to assess their self-reported needs (after they have an understanding of the role) and caregiving outcomes. Research is needed to develop a valid and reliable tool thatpre-emptively assesses the gaps in caregiver readiness that can be utilized prior to the transition from the institutional setting to home. This will enable the identification and evaluation of primary prevention strategies to improve caregiver preparation so that the adaption to the new caregiving role can be expedited, minimizing the adverse health effects on both the caregiver and stroke survivor.

Providers must be aware of the changing needs of stroke survivors and tailor plans of care accordingly, using evidenced-based interventions. Policy makers must consider research on the long term effects of caregiving and consider legislation to support the health and respite needs of the growing population of caregivers. This will contribute to attaining the 3 aims of the National Quality Strategy: improving quality of care, improving health, and reducing health care system costs [74].

Corresponding author: Barbara J. Lutz, PhD, 601 S. College Rd., Wilmington, NC 28403, [email protected].

Financial disclosures: None.

From the School of Nursing, University of North Carolina-Wilmington, Wilmington, NC (Dr. Lutz), and the Kaiser Foundation Rehabilitation Center, Kaiser Permanente, Vallejo, CA (Ms. Camicia).

Abstract

- Objectives: To describe issues faced by stroke family caregivers, discuss evidence-based interventions to improve caregiver outcomes, and provide recommendations for clinicians caring for stroke survivors and their family caregivers.

- Methods: Literature review.

- Results: Caregiver health is linked to the stroke survivor’s degree of functional recovery; the more severe the level of disability, the more likely the caregiver will experience higher levels of strain, increased depression, and poor health. Inadequate caregiver preparation contributes to poorer outcomes. Caregivers describe many unmet needs including skills training; communicating with providers; resource identification and activation; finances; respite; and emotional support. Caregivers need to be assessed for gaps in preparation to provide care. Interventions are recommended that combine skill-building and psycho-educational strategies; are tailored to individual caregiver needs; are face-to-face when feasible; and include 5 to 9 sessions. Family counseling may also be indicated. Intermittent assessment of caregiving outcomes should be conducted so that changing needs can be addressed.

- Conclusions: Stroke caregiving affects the caregiver’s physical, mental, and emotional health, and these effects are sustained over time. Poorly prepared caregivers are more likely to experience negative outcomes and their needs are high during the transition from inpatient care to home. Ongoing support is also important, especially for caregivers who are caring for a stroke survivor with moderate to severe functional limitations. In order to better address unmet needs of stroke caregivers, intermittent assessments should be conducted so that interventions can be tailored to their changing needs over time.

Key words: stroke; family caregivers; care transitions; patient-centered care.

Stroke is a leading cause of major disability in the United States [1] and around the world [2]. Of the estimated 6.6 million stroke survivors living in the US, more than 4.5 million have some level of disability following stroke [1]. In 2009, more than 970,000 persons were hospitalized with stroke in the US with an average length of stay of 5.3 days [3]. Approximately 44% of stroke survivors are discharged home directly from acute care without post-acute care [4]. Only about 25% of stroke survivors receive care in inpatient rehabilitation facilities [4] even though the American Heart Association (AHA) stroke rehabilitation guidelines recommend this level of care for qualified patients [5]. Regardless of the care trajectory, when stroke survivors return home they frequently require assistance with basic and instrumental activities of daily living (BADL/IADL), usually provided by family members who often feel unprepared and overwhelmed by the demands and responsibilities of this caregiving role.

The deleterious effects of caregiving have been identified as a major public health concern [6]. A robust body of literature has established that caregivers are often adversely affected by the demands of their caregiving role. However, much of this literature focuses on caregivers for persons with dementia. Needs of stroke caregivers are categorically different from caregivers of persons with dementia in that stroke is an unpredictable, life-disrupting, crisis event that occurs suddenly leaving family members with insufficient time to prepare for the new roles and caregiving responsibilities. The patient typically transitions from being cared for by multiple providers in an acute care, inpatient rehabilitation facility, or skilled nursing facility (SNF)—24 hours a day, 7 days a week—to relying fully on one person (most often a spouse or adult child) who may not be ready to handle the overwhelming demands and constant vigilance required for adequate care at home. Studies have repeatedly demonstrated the damaging health effects of caregiving. Caregivers describe feeling isolated, abandoned, and alone [7–9], and what frequently follows is a predictable trajectory of depression and deteriorating health and well-being [7,10–13]. The purpose of this article is to describe difficulties and issues faced by family members who are caring for a loved one following stroke, discuss evidence-based interventions designed to improve stroke caregiver outcomes, and provide recommendations for clinicians who care for stroke survivors and their family caregivers post-stroke.

Difficulties and Issues Faced by Caregivers

With an aging population and increasing incidence of stroke, it is imperative that we identify and address the ongoing needs of stroke survivors and their family caregivers in the post-stroke recovery period. Multiple studies acknowledge that stroke is a life-changing event for patients and their family members [9,14] that often results in overwhelming feelings of uncertainty, fear [15], grief, and loss [9]. Stroke also can have long-term effects on the health of stroke survivors and their family caregivers. Studies have identified the effects of caregiving on the health of caregivers and subsequent links between stroke survivor and caregiver outcomes over time [12,16,17]; the ongoing needs of stroke caregivers post-discharge [18,19]; and the importance of assessing caregiver preparedness and subsequent caregiving outcomes [5,20].

Effects of Caregiving on the Health of Caregivers and Stroke Survivors

Research on stroke caregiving consistently indicates that caregiver health is inextricably linked to the stroke survivor’s degree of physical, cognitive, psychological, and emotional recovery. The more severe the patient’s level of disability, the more likely the caregiver will experience higher levels of strain, increased depression, and poor health outcomes [21]. Studies also indicate that certain caregiver characteristics, such as being female or having lower educational level, pre-existing health conditions [7,22,23], poor family functioning, lack of social support [22,24], or lack of preparation [25], are all risk factors for poorer caregiver outcomes.