User login

Hearing Patient Stories: Use of Medical Humanities on a Large-Scale, Virtual Platform to Improve Clinician Engagement

Hearing Patient Stories: Use of Medical Humanities on a Large-Scale, Virtual Platform to Improve Clinician Engagement

The COVID-19 pandemic presented stressors for patients and health care professionals alike, and the prevalence of health care practitioner burnout and dissatisfaction has risen dramatically.1,2 This, in combination with an increasingly virtual interface between patients and care teams, has the potential to lead to increased depersonalization, anxiety, distress, and diminished overall well-being among clinicians.1,3 Within the Veterans Health Administration (VHA), women’s health primary care practitioners (PCPs) are specially trained clinicians thatprovide comprehensive care to women veterans. Data suggest that women’s health PCPs may experience higher rates of burnout and attrition (14% per year) compared to general PCPs in VHA.4 Burnout among PCPs, especially those working at VHA, is well known and likely related to poor interdisciplinary team structure, limited administrative time, high patient complexity, and isolation from additional resources (eg, rural settings).4-7 Increased clinician burnout is associated with poorer quality of care and worsening quality of the doctor-patient relationship.8

The medical humanities can act as a countermeasure to clinician burnout.9,10 Studies have demonstrated that physicians who participate in the medical humanities are more empathic and experience less burnout.11,12 Engaging with patient stories through listening and writing has been a source of fulfillment for clinicians.13 Despite the benefits of narrative medicine, programs are often limited in scope in small face-to-face group settings during elective time or outside work hours.14 The COVID-19 pandemic presented significant challenges to implementing such programming. The VHA is a large health care system with many rural locations, which further limits the availability of traditional small-group and face-to-face trainings. Few studies describe large-scale medical humanities training in virtual learning environments.

NARRATIVE MEDICINE EVENT

To improve satisfaction and engagement among PCPs who care for women veterans, we developed, implemented, and evaluated a large-scale, virtual, interprofessional narrative medicine event aimed at achieving the following: (1) gain a deeper appreciation of the impact of deployments on women veterans; (2) describe the social and emotional challenges faced by women veterans returning from deployment (reintegration); (3) identify strategies to support veterans during reintegration; (4) apply narrative medicine techniques on a large-scale, virtual platform; and (5) assess clinician engagement and satisfaction following participation. We hypothesized that clinician satisfaction and appreciation would improve with a better understanding of the unique complexities of deployment and reintegration faced by women veterans. Utilizing a novel, humanities-based intervention would lead to strong engagement and interaction from participants.

Setting

A 3-hour virtual session was conducted on November 15, 2022, for an interdisciplinary audience. This included physicians and trainees in medicine and behavioral health, nurse practitioners, social workers, dieticians, nurses, and clinical support staff. The training was advertised via emails through established mailing lists and newsletters, reaching a large interdisciplinary VHA audience 90 days prior to the event. This allowed potential participants to dedicate time to attend the session. The training was open to all VHA employees, with no inclusion or exclusion criteria for either the training or the evaluation. The training was delivered within existing space utilized for continuing medical education in women’s health.

For the session, the 93-minute documentary Journey to Normal (jtninc.org) was chosen because it focused on the impact of deployment on women veterans and their experiences when returning home. The film follows the stories of several women veterans through combat and reintegration. The screening was split into 2 segments given the emotional impact and length of the documentary.

A facilitator opened the session by reading a series of reflective prompts centered on women veteran deployment, reintegration, and the stressors surrounding these transitions. The initial prompt served to familiarize participants with the session’s interactive components. Additional prompts were interspersed and discussed in real time and were chosen to mirror the major themes of the documentary: the emotional and psychological impact of deployment and reintegration for women veterans. Short responses and word cloud generation were used and debriefed synchronously to encourage ongoing engagement. Participants responded to prompts through anonymous polling and the chat function of the virtual platform.

During intermission, we introduced My Life, My Story (MLMS). MLMS is a VHA initiative started in 2013 that, with the veteran’s permission, shares a piece of a veteran’s life story with their health care practitioner in their medical chart.15 Evaluation of MLMS has demonstrated positive impacts on assessments of patient-clinician connection.16 The MLMS goal to improve patient-centered care competencies by learning stories of veterans aligned with the overarching goals of this program. Following the film, participants were given 10 minutes to respond to a final reflective prompt. The session ended with a review of existing VHA resources to support returning veterans, followed by a question-and-answer session conducted via chat.

We used the Brightcove virtual platform to stream this program, which facilitated significant interaction between participants and facilitators, as well as between participants themselves. In addition to posing questions to the session leaders, participants could directly respond to each other’s comments within the chat function and also upvote/downvote or emphasize others’ comments.

Evaluation

The evaluation schema was 2-fold. Because this session was presented as a part of the national VA Women’s Health webinar series, a standard evaluation was dictated by the VHA Employee Education System. This survey was electronically disseminated and included questions on occupational category and overall satisfaction, plus 9 standard evaluation questions and 4 program-specific questions tied to the workshop objectives. The standard evaluation questions assessed participant satisfaction with the training, satisfaction with the training environment, and appropriateness of the content. The programspecific questions asked the participants whether the session met the stated learning objectives. All questions used a 5-point Likert scale (1, strongly disagree; 5, strongly agree). Descriptive statistics were used for analysis. Individual chat messages and spontaneous replies were analyzed as a surrogate measures of audience engagement. A qualitative analysis of participants’ final reflections to assess for attitudes related to patient care, empathy, and burnout following participation in this curriculum is forthcoming.

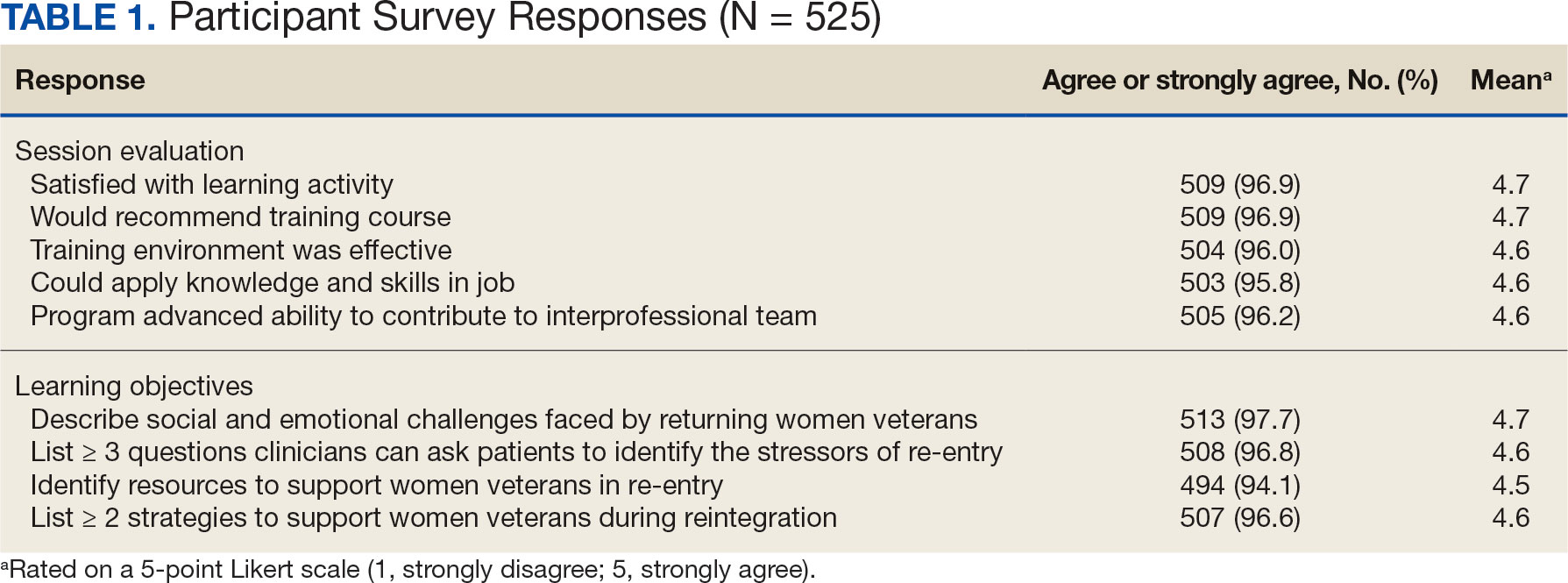

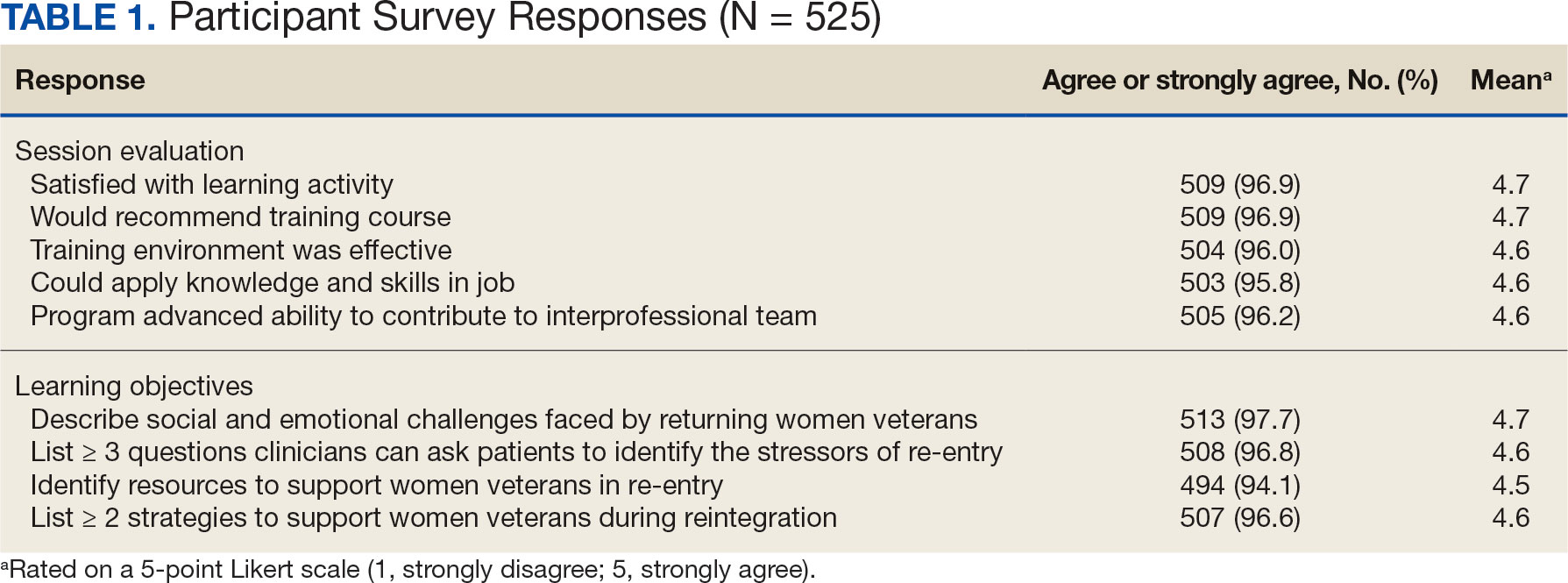

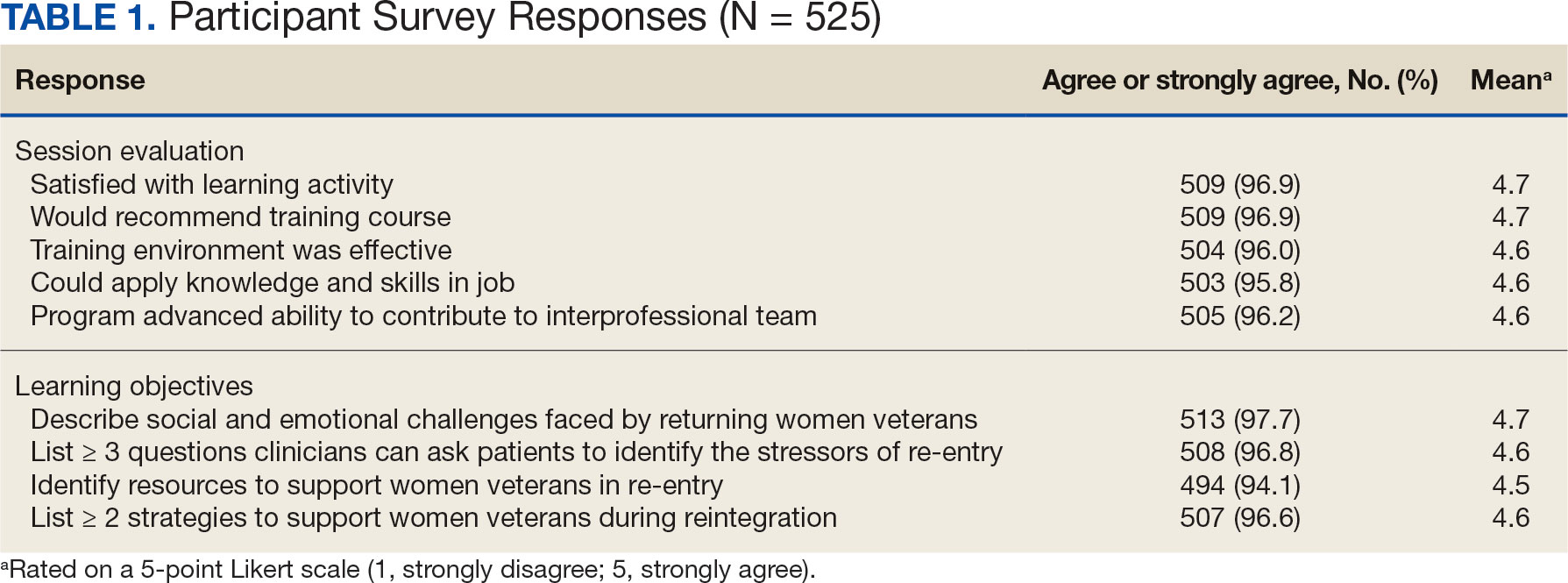

A total of 876 participants attended the virtual setting and 525 (59.9%) completed the immediate postevaluation survey. Respondents represented a variety of disciplines, including 179 nurses (34.1%), 100 social workers (19.0%), 65 physicians (12.4%), and 10 physician assistants (1.9%), with < 10% comprising counselors, dentists, dietitians, pharmacists, physical therapists, and psychologists. Nearly all participants reported satisfaction with the learning activity, would recommend it to others, and felt it advanced their knowledge, attitudes, and skills to better contribute to their VHA interprofessional team for patient care (Table 1). Similarly, participants reported a highlevel of agreement that the program satisfied the session-specific objectives. In response to an open-ended question on the standard VA evaluation regarding overall perceptions of the training, free-text responses included such statements as, “I think this should be mandatory training for all VA [clinicians]”; and “This webinar [opened] my mind to the various struggles women veterans may encounter when [they] return to civilian life and [increased] my understanding of how I could support.”

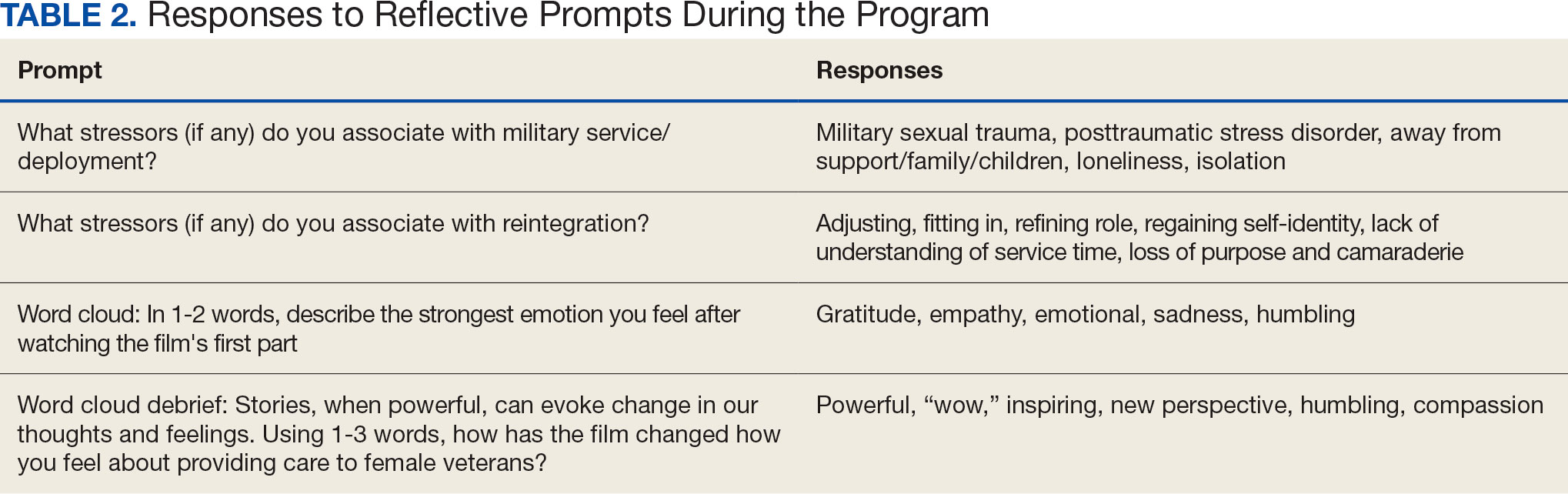

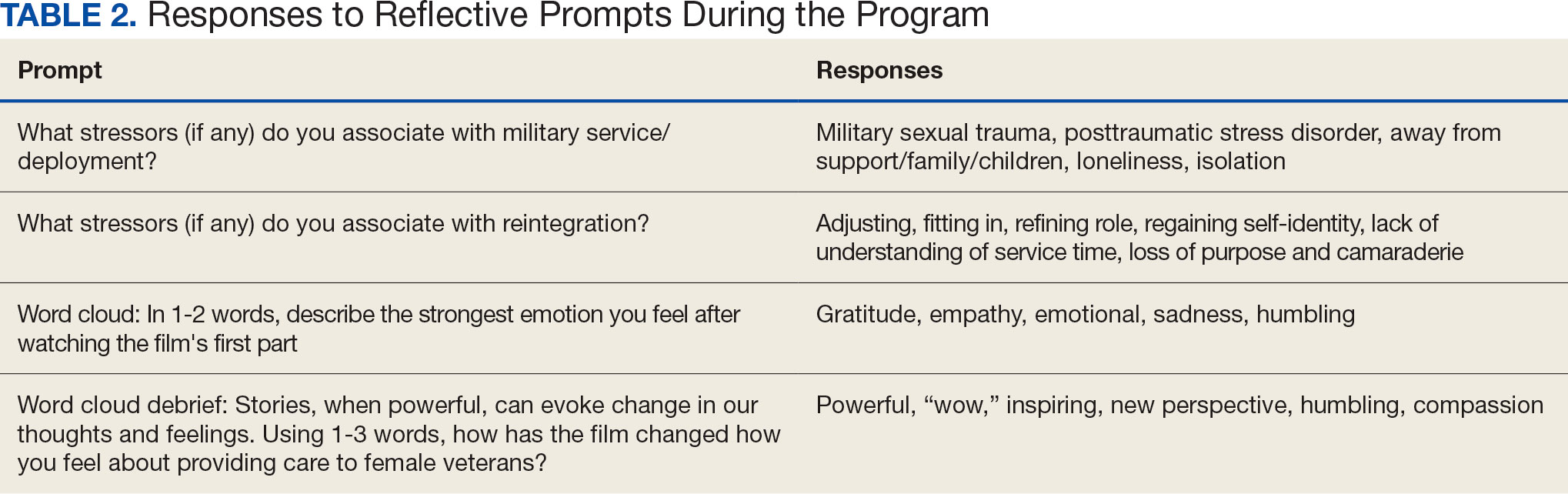

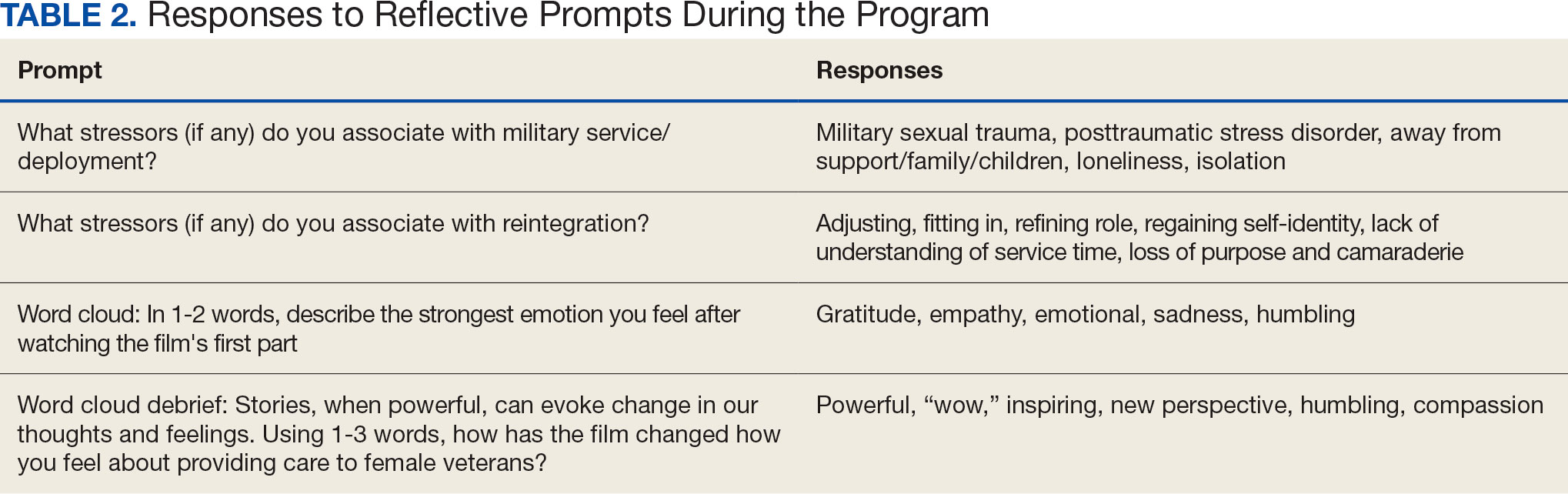

More than 1700 individual chat messages and > 80 spontaneous replies between participants were recorded during the interactive session (Table 2). Spontaneous quotes written in the chat included: “This is the best film representing the female veteran I have ever seen;” “Powerful and perspective changing;” “Thank you for sharing this incredible film;” and “I needed this to remind me to focus on woman veterans. Although our female veteran population is small it will remind me daily of their dedication, recognizing that there are so many facets of making the ultimate sacrifice.” Several participants said such programming should be a mandatory component of VA new employee orientation.

DISCUSSION

Clinician burnout diminishes empathetic patient-physician engagement. Patients’ stories are a known, powerful way to evoke empathy. This session provides one of the first examples of a straightforward approach to delivering a medical humanities intervention to a large audience via virtual platform. As measured by its high engagement, participant satisfaction, and narrative evaluations, this model was successful in evoking empathy and reinforcing the core VHA values for patient care: integrity, commitment, advocacy, respect, and excellence.

Rates of burnout and disengagement among PCPs are high and increased during the COVID-19 pandemic.2 This curriculum used a synchronous, narrative-based approach during work hours to address burnout. Lack of empathy is a cause and consequence of burnout and disengagement. Narrative approaches, especially those evoking patients’ stories can evoke empathy and help counteract such burnout. This curriculum demonstrates one of the first large-scale, narrative-based, virtual-platform approaches to utilizing patients’ stories for positive clinician impact, as evidenced by the extensive participation, engagement, and satisfaction of participants.

Individuals interested in implementing a similar program should consider common barriers, including time constraints, advertising, and clinician buy-in. Several key factors led to the successful implementation of this program. First, partnering with established educational efforts related to improving care for veterans provided time to implement the program and establish mechanisms for advertising. The VHA is a mission-driven organization; directly tying this intervention to the mission likely contributed to participant buy-in and programmatic success. Further, by partnering with established educational efforts, this session was conducted during business hours, allowing for widespread participation.

A diverse group of VHA clinicians were actively engaged throughout the session. Chat data demonstrated not only numerous responses to directed prompts, but also a larger extemporaneous conversation among participants. Additionally, it is clear participants were deeply engaged with the material. The quality of participant responses demonstrates the impact of narrative stories and included a new respect for our shared patients, a sense of humbleness as it relates to the women veteran experience, and a sense of pride in both the VHA mission and their roles as a part of the organization.

This session did not end with traditional take-home skills or reference handout resources typical of continuing education. This was intentional; the intended take-home message was the evoked emotional response and resultant perspective shift. The impact of this session on patient care will be examined in a forthcoming qualitative analysis of participants written reflections.

Limitations

Some participants noted that the chat could be distracting from the film. Others described that virtually attending the session allowed increased opportunity for interruption by ongoing patient care responsibilities, resulting in diverted attention. Many participants were granted protected time to attend this continuing education session; however, this was not always the case. Additionally, this evaluation is limited, as 40% of participants elected to not complete the postevent survey. The individuals who choose to respond may have been more engaged with the content or felt more strongly about the impact of the session. However, the volume of chat engagement during the session suggests strong participant involvement. The analysis was also limited by an electronic survey which did not allow more granular assessment of the data.

This session also raised an ethical consideration. The film evoked very strong emotional responses which, for some, were challenging to attend to personally in a large-scale virtual environment. Established clinician resources were highlighted during the session that were available for any participant who needed additional support. Participants were also encouraged to step away and process their emotions, if needed. Future interactions of this session might consider improved interparticipant chat management and upfront warnings about the emotional impact of the film accompanied by proactive dissemination of resources for participant support. One example of such resources includes breakout rooms facilitated by trained counselors. Prompts might also be adjusted to allow for more guided interparticipant engagement; facilitation can be brief as participants’ responses often carry the conversation.

CONCLUSIONS

This study shows that a large-scale, virtual medical humanities intervention is not only possible but well received, as evidenced by both quantity and quality of participant responses and engagement. The narrative approach of hearing patients’ stories, as portrayed in Journey to Normal, was found to be satisfying and appreciated by participants. Such an intervention has the potential to evoke empathy and help counteract burnout and disengagement among clinicians. This study directly aligned to the greater mission of the VHA: to improve quality medical care for all veterans, including women veterans, a subset population that is often overlooked. Organizations beyond the VHA may wish to leverage virtual learning as a mechanism to offer medical humanities to a wider audience. To optimize success, future programs should be tied to organizational missions, highlight patient voices and stories, and utilize platforms that allow for participant interactivity. Through virtual platforms, the medical humanities can reach a broader audience without detracting from its impact.

- Van Wert MJ, Gandhi S, Gupta I, et al. Healthcare worker mental health after the initial peak of the COVID- 19 pandemic: a US medical center cross-sectional survey. J Gen Intern Med. 2022;37(5):1169-1176. doi:10.1007/s11606-021-07251-0

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Vital Signs. Health workers face a mental health crisis: workers report harassment, burnout, and poor mental health; supportive workplaces can help. Updated October 24, 2023. Accessed February 18, 2025. https://www.cdc.gov/vitalsigns/health-worker-mental-health/index.html

- Holmgren AJ, Downing NL, Tang M, Sharp C, Longhurst C, Huckman RS. Assessing the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on clinician ambulatory electronic health record use. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2022;29(3):453-460. doi:10.1093/jamia/ocab268

- Apaydin EA, Mohr DC, Hamilton AB, Rose DE, Haskell S, Yano EM. Differences in burnout and intent to leave between women’s health and general primary care providers in the Veterans Health Administration. J Gen Intern Med. 2022;37(10):2382-2389. doi:10.1007/s11606-021-07133-5

- Willard-Grace R, Knox M, Huang B, Hammer H, Kivlahan C, Grumbach K. Burnout and health care workforce turnover. Ann Fam Med. 2019;17(1):36-41. doi:10.1370/afm.2338

- Rinne ST, Mohr DC, Swamy L, Blok AC, Wong ES, Charns MP. National burnout trends among physicians working in the department of veterans affairs. J Gen Intern Med. 2020;35(5):1382-1388. doi:10.1007/s11606-019-05582-7

- Spinelli WM, Fernstrom KM, Galos DL, Britt HR. Extending our understanding of burnout and its associated factors: providers and staff in primary care clinics. Eval Health Prof. 2016;39(3):282-298. doi:10.1177/0163278716637900

- Abraham CM, Zheng K, Poghosyan L. Predictors and outcomes of burnout among primary care providers in the United States: a systematic review. Med Care Res Rev. 2020;77(5):387-401. doi:10.1177/1077558719888427

- Charon R, Williams P. Introduction: the humanities and medical education. Acad Med. 1995;70(9):758-760.

- Winkel AF, Yingling S, Jones A-A, Nicholson J. Reflection as a learning tool in graduate medical education: a systematic review. J Grad Med Educ. 2017;9(4):430-439. doi:10.4300/JGME-D-16-00500.1

- Charon R. The patient-physician relationship. Narrative medicine: a model for empathy, reflection, profession, and trust. JAMA. 2001;286(15):1897-1902. doi:10.1001/jama.286.15.1897

- DasGupta S, Charon R. Personal illness narratives: using reflective writing to teach empathy. Acad Med. 2004; 79(4):351-356. doi:10.1097/00001888-200404000-00013

- Liao JM, Secemsky BJ. The value of narrative medical writing in internal medicine residency. J Gen Intern Med. 2015;30(11):1707-1710. doi:10.1007/s11606-015-3460-x

- Branch WT, Kern D, Haidet P, et al. The patient-physician relationship. Teaching the human dimensions of care in clinical settings. JAMA. 2001;286(9):1067-1074. doi:10.1001/jama.286.9.1067

- Roberts TJ, Ringler T, Krahn D, Ahearn E. The my life, my story program: sustained impact of veterans’ personal narratives on healthcare providers 5 years after implementation. Health Commun. 2021;36(7):829-836. doi:10.1080/10410236.2020.1719316

- Lam JA, Feingold-Link M, Noguchi J, et al. My life, my story: integrating a life story narrative component into medical student curricula. MedEdPORTAL. 2022;18:11211. doi:10.15766/mep_2374-8265.11211

The COVID-19 pandemic presented stressors for patients and health care professionals alike, and the prevalence of health care practitioner burnout and dissatisfaction has risen dramatically.1,2 This, in combination with an increasingly virtual interface between patients and care teams, has the potential to lead to increased depersonalization, anxiety, distress, and diminished overall well-being among clinicians.1,3 Within the Veterans Health Administration (VHA), women’s health primary care practitioners (PCPs) are specially trained clinicians thatprovide comprehensive care to women veterans. Data suggest that women’s health PCPs may experience higher rates of burnout and attrition (14% per year) compared to general PCPs in VHA.4 Burnout among PCPs, especially those working at VHA, is well known and likely related to poor interdisciplinary team structure, limited administrative time, high patient complexity, and isolation from additional resources (eg, rural settings).4-7 Increased clinician burnout is associated with poorer quality of care and worsening quality of the doctor-patient relationship.8

The medical humanities can act as a countermeasure to clinician burnout.9,10 Studies have demonstrated that physicians who participate in the medical humanities are more empathic and experience less burnout.11,12 Engaging with patient stories through listening and writing has been a source of fulfillment for clinicians.13 Despite the benefits of narrative medicine, programs are often limited in scope in small face-to-face group settings during elective time or outside work hours.14 The COVID-19 pandemic presented significant challenges to implementing such programming. The VHA is a large health care system with many rural locations, which further limits the availability of traditional small-group and face-to-face trainings. Few studies describe large-scale medical humanities training in virtual learning environments.

NARRATIVE MEDICINE EVENT

To improve satisfaction and engagement among PCPs who care for women veterans, we developed, implemented, and evaluated a large-scale, virtual, interprofessional narrative medicine event aimed at achieving the following: (1) gain a deeper appreciation of the impact of deployments on women veterans; (2) describe the social and emotional challenges faced by women veterans returning from deployment (reintegration); (3) identify strategies to support veterans during reintegration; (4) apply narrative medicine techniques on a large-scale, virtual platform; and (5) assess clinician engagement and satisfaction following participation. We hypothesized that clinician satisfaction and appreciation would improve with a better understanding of the unique complexities of deployment and reintegration faced by women veterans. Utilizing a novel, humanities-based intervention would lead to strong engagement and interaction from participants.

Setting

A 3-hour virtual session was conducted on November 15, 2022, for an interdisciplinary audience. This included physicians and trainees in medicine and behavioral health, nurse practitioners, social workers, dieticians, nurses, and clinical support staff. The training was advertised via emails through established mailing lists and newsletters, reaching a large interdisciplinary VHA audience 90 days prior to the event. This allowed potential participants to dedicate time to attend the session. The training was open to all VHA employees, with no inclusion or exclusion criteria for either the training or the evaluation. The training was delivered within existing space utilized for continuing medical education in women’s health.

For the session, the 93-minute documentary Journey to Normal (jtninc.org) was chosen because it focused on the impact of deployment on women veterans and their experiences when returning home. The film follows the stories of several women veterans through combat and reintegration. The screening was split into 2 segments given the emotional impact and length of the documentary.

A facilitator opened the session by reading a series of reflective prompts centered on women veteran deployment, reintegration, and the stressors surrounding these transitions. The initial prompt served to familiarize participants with the session’s interactive components. Additional prompts were interspersed and discussed in real time and were chosen to mirror the major themes of the documentary: the emotional and psychological impact of deployment and reintegration for women veterans. Short responses and word cloud generation were used and debriefed synchronously to encourage ongoing engagement. Participants responded to prompts through anonymous polling and the chat function of the virtual platform.

During intermission, we introduced My Life, My Story (MLMS). MLMS is a VHA initiative started in 2013 that, with the veteran’s permission, shares a piece of a veteran’s life story with their health care practitioner in their medical chart.15 Evaluation of MLMS has demonstrated positive impacts on assessments of patient-clinician connection.16 The MLMS goal to improve patient-centered care competencies by learning stories of veterans aligned with the overarching goals of this program. Following the film, participants were given 10 minutes to respond to a final reflective prompt. The session ended with a review of existing VHA resources to support returning veterans, followed by a question-and-answer session conducted via chat.

We used the Brightcove virtual platform to stream this program, which facilitated significant interaction between participants and facilitators, as well as between participants themselves. In addition to posing questions to the session leaders, participants could directly respond to each other’s comments within the chat function and also upvote/downvote or emphasize others’ comments.

Evaluation

The evaluation schema was 2-fold. Because this session was presented as a part of the national VA Women’s Health webinar series, a standard evaluation was dictated by the VHA Employee Education System. This survey was electronically disseminated and included questions on occupational category and overall satisfaction, plus 9 standard evaluation questions and 4 program-specific questions tied to the workshop objectives. The standard evaluation questions assessed participant satisfaction with the training, satisfaction with the training environment, and appropriateness of the content. The programspecific questions asked the participants whether the session met the stated learning objectives. All questions used a 5-point Likert scale (1, strongly disagree; 5, strongly agree). Descriptive statistics were used for analysis. Individual chat messages and spontaneous replies were analyzed as a surrogate measures of audience engagement. A qualitative analysis of participants’ final reflections to assess for attitudes related to patient care, empathy, and burnout following participation in this curriculum is forthcoming.

A total of 876 participants attended the virtual setting and 525 (59.9%) completed the immediate postevaluation survey. Respondents represented a variety of disciplines, including 179 nurses (34.1%), 100 social workers (19.0%), 65 physicians (12.4%), and 10 physician assistants (1.9%), with < 10% comprising counselors, dentists, dietitians, pharmacists, physical therapists, and psychologists. Nearly all participants reported satisfaction with the learning activity, would recommend it to others, and felt it advanced their knowledge, attitudes, and skills to better contribute to their VHA interprofessional team for patient care (Table 1). Similarly, participants reported a highlevel of agreement that the program satisfied the session-specific objectives. In response to an open-ended question on the standard VA evaluation regarding overall perceptions of the training, free-text responses included such statements as, “I think this should be mandatory training for all VA [clinicians]”; and “This webinar [opened] my mind to the various struggles women veterans may encounter when [they] return to civilian life and [increased] my understanding of how I could support.”

More than 1700 individual chat messages and > 80 spontaneous replies between participants were recorded during the interactive session (Table 2). Spontaneous quotes written in the chat included: “This is the best film representing the female veteran I have ever seen;” “Powerful and perspective changing;” “Thank you for sharing this incredible film;” and “I needed this to remind me to focus on woman veterans. Although our female veteran population is small it will remind me daily of their dedication, recognizing that there are so many facets of making the ultimate sacrifice.” Several participants said such programming should be a mandatory component of VA new employee orientation.

DISCUSSION

Clinician burnout diminishes empathetic patient-physician engagement. Patients’ stories are a known, powerful way to evoke empathy. This session provides one of the first examples of a straightforward approach to delivering a medical humanities intervention to a large audience via virtual platform. As measured by its high engagement, participant satisfaction, and narrative evaluations, this model was successful in evoking empathy and reinforcing the core VHA values for patient care: integrity, commitment, advocacy, respect, and excellence.

Rates of burnout and disengagement among PCPs are high and increased during the COVID-19 pandemic.2 This curriculum used a synchronous, narrative-based approach during work hours to address burnout. Lack of empathy is a cause and consequence of burnout and disengagement. Narrative approaches, especially those evoking patients’ stories can evoke empathy and help counteract such burnout. This curriculum demonstrates one of the first large-scale, narrative-based, virtual-platform approaches to utilizing patients’ stories for positive clinician impact, as evidenced by the extensive participation, engagement, and satisfaction of participants.

Individuals interested in implementing a similar program should consider common barriers, including time constraints, advertising, and clinician buy-in. Several key factors led to the successful implementation of this program. First, partnering with established educational efforts related to improving care for veterans provided time to implement the program and establish mechanisms for advertising. The VHA is a mission-driven organization; directly tying this intervention to the mission likely contributed to participant buy-in and programmatic success. Further, by partnering with established educational efforts, this session was conducted during business hours, allowing for widespread participation.

A diverse group of VHA clinicians were actively engaged throughout the session. Chat data demonstrated not only numerous responses to directed prompts, but also a larger extemporaneous conversation among participants. Additionally, it is clear participants were deeply engaged with the material. The quality of participant responses demonstrates the impact of narrative stories and included a new respect for our shared patients, a sense of humbleness as it relates to the women veteran experience, and a sense of pride in both the VHA mission and their roles as a part of the organization.

This session did not end with traditional take-home skills or reference handout resources typical of continuing education. This was intentional; the intended take-home message was the evoked emotional response and resultant perspective shift. The impact of this session on patient care will be examined in a forthcoming qualitative analysis of participants written reflections.

Limitations

Some participants noted that the chat could be distracting from the film. Others described that virtually attending the session allowed increased opportunity for interruption by ongoing patient care responsibilities, resulting in diverted attention. Many participants were granted protected time to attend this continuing education session; however, this was not always the case. Additionally, this evaluation is limited, as 40% of participants elected to not complete the postevent survey. The individuals who choose to respond may have been more engaged with the content or felt more strongly about the impact of the session. However, the volume of chat engagement during the session suggests strong participant involvement. The analysis was also limited by an electronic survey which did not allow more granular assessment of the data.

This session also raised an ethical consideration. The film evoked very strong emotional responses which, for some, were challenging to attend to personally in a large-scale virtual environment. Established clinician resources were highlighted during the session that were available for any participant who needed additional support. Participants were also encouraged to step away and process their emotions, if needed. Future interactions of this session might consider improved interparticipant chat management and upfront warnings about the emotional impact of the film accompanied by proactive dissemination of resources for participant support. One example of such resources includes breakout rooms facilitated by trained counselors. Prompts might also be adjusted to allow for more guided interparticipant engagement; facilitation can be brief as participants’ responses often carry the conversation.

CONCLUSIONS

This study shows that a large-scale, virtual medical humanities intervention is not only possible but well received, as evidenced by both quantity and quality of participant responses and engagement. The narrative approach of hearing patients’ stories, as portrayed in Journey to Normal, was found to be satisfying and appreciated by participants. Such an intervention has the potential to evoke empathy and help counteract burnout and disengagement among clinicians. This study directly aligned to the greater mission of the VHA: to improve quality medical care for all veterans, including women veterans, a subset population that is often overlooked. Organizations beyond the VHA may wish to leverage virtual learning as a mechanism to offer medical humanities to a wider audience. To optimize success, future programs should be tied to organizational missions, highlight patient voices and stories, and utilize platforms that allow for participant interactivity. Through virtual platforms, the medical humanities can reach a broader audience without detracting from its impact.

The COVID-19 pandemic presented stressors for patients and health care professionals alike, and the prevalence of health care practitioner burnout and dissatisfaction has risen dramatically.1,2 This, in combination with an increasingly virtual interface between patients and care teams, has the potential to lead to increased depersonalization, anxiety, distress, and diminished overall well-being among clinicians.1,3 Within the Veterans Health Administration (VHA), women’s health primary care practitioners (PCPs) are specially trained clinicians thatprovide comprehensive care to women veterans. Data suggest that women’s health PCPs may experience higher rates of burnout and attrition (14% per year) compared to general PCPs in VHA.4 Burnout among PCPs, especially those working at VHA, is well known and likely related to poor interdisciplinary team structure, limited administrative time, high patient complexity, and isolation from additional resources (eg, rural settings).4-7 Increased clinician burnout is associated with poorer quality of care and worsening quality of the doctor-patient relationship.8

The medical humanities can act as a countermeasure to clinician burnout.9,10 Studies have demonstrated that physicians who participate in the medical humanities are more empathic and experience less burnout.11,12 Engaging with patient stories through listening and writing has been a source of fulfillment for clinicians.13 Despite the benefits of narrative medicine, programs are often limited in scope in small face-to-face group settings during elective time or outside work hours.14 The COVID-19 pandemic presented significant challenges to implementing such programming. The VHA is a large health care system with many rural locations, which further limits the availability of traditional small-group and face-to-face trainings. Few studies describe large-scale medical humanities training in virtual learning environments.

NARRATIVE MEDICINE EVENT

To improve satisfaction and engagement among PCPs who care for women veterans, we developed, implemented, and evaluated a large-scale, virtual, interprofessional narrative medicine event aimed at achieving the following: (1) gain a deeper appreciation of the impact of deployments on women veterans; (2) describe the social and emotional challenges faced by women veterans returning from deployment (reintegration); (3) identify strategies to support veterans during reintegration; (4) apply narrative medicine techniques on a large-scale, virtual platform; and (5) assess clinician engagement and satisfaction following participation. We hypothesized that clinician satisfaction and appreciation would improve with a better understanding of the unique complexities of deployment and reintegration faced by women veterans. Utilizing a novel, humanities-based intervention would lead to strong engagement and interaction from participants.

Setting

A 3-hour virtual session was conducted on November 15, 2022, for an interdisciplinary audience. This included physicians and trainees in medicine and behavioral health, nurse practitioners, social workers, dieticians, nurses, and clinical support staff. The training was advertised via emails through established mailing lists and newsletters, reaching a large interdisciplinary VHA audience 90 days prior to the event. This allowed potential participants to dedicate time to attend the session. The training was open to all VHA employees, with no inclusion or exclusion criteria for either the training or the evaluation. The training was delivered within existing space utilized for continuing medical education in women’s health.

For the session, the 93-minute documentary Journey to Normal (jtninc.org) was chosen because it focused on the impact of deployment on women veterans and their experiences when returning home. The film follows the stories of several women veterans through combat and reintegration. The screening was split into 2 segments given the emotional impact and length of the documentary.

A facilitator opened the session by reading a series of reflective prompts centered on women veteran deployment, reintegration, and the stressors surrounding these transitions. The initial prompt served to familiarize participants with the session’s interactive components. Additional prompts were interspersed and discussed in real time and were chosen to mirror the major themes of the documentary: the emotional and psychological impact of deployment and reintegration for women veterans. Short responses and word cloud generation were used and debriefed synchronously to encourage ongoing engagement. Participants responded to prompts through anonymous polling and the chat function of the virtual platform.

During intermission, we introduced My Life, My Story (MLMS). MLMS is a VHA initiative started in 2013 that, with the veteran’s permission, shares a piece of a veteran’s life story with their health care practitioner in their medical chart.15 Evaluation of MLMS has demonstrated positive impacts on assessments of patient-clinician connection.16 The MLMS goal to improve patient-centered care competencies by learning stories of veterans aligned with the overarching goals of this program. Following the film, participants were given 10 minutes to respond to a final reflective prompt. The session ended with a review of existing VHA resources to support returning veterans, followed by a question-and-answer session conducted via chat.

We used the Brightcove virtual platform to stream this program, which facilitated significant interaction between participants and facilitators, as well as between participants themselves. In addition to posing questions to the session leaders, participants could directly respond to each other’s comments within the chat function and also upvote/downvote or emphasize others’ comments.

Evaluation

The evaluation schema was 2-fold. Because this session was presented as a part of the national VA Women’s Health webinar series, a standard evaluation was dictated by the VHA Employee Education System. This survey was electronically disseminated and included questions on occupational category and overall satisfaction, plus 9 standard evaluation questions and 4 program-specific questions tied to the workshop objectives. The standard evaluation questions assessed participant satisfaction with the training, satisfaction with the training environment, and appropriateness of the content. The programspecific questions asked the participants whether the session met the stated learning objectives. All questions used a 5-point Likert scale (1, strongly disagree; 5, strongly agree). Descriptive statistics were used for analysis. Individual chat messages and spontaneous replies were analyzed as a surrogate measures of audience engagement. A qualitative analysis of participants’ final reflections to assess for attitudes related to patient care, empathy, and burnout following participation in this curriculum is forthcoming.

A total of 876 participants attended the virtual setting and 525 (59.9%) completed the immediate postevaluation survey. Respondents represented a variety of disciplines, including 179 nurses (34.1%), 100 social workers (19.0%), 65 physicians (12.4%), and 10 physician assistants (1.9%), with < 10% comprising counselors, dentists, dietitians, pharmacists, physical therapists, and psychologists. Nearly all participants reported satisfaction with the learning activity, would recommend it to others, and felt it advanced their knowledge, attitudes, and skills to better contribute to their VHA interprofessional team for patient care (Table 1). Similarly, participants reported a highlevel of agreement that the program satisfied the session-specific objectives. In response to an open-ended question on the standard VA evaluation regarding overall perceptions of the training, free-text responses included such statements as, “I think this should be mandatory training for all VA [clinicians]”; and “This webinar [opened] my mind to the various struggles women veterans may encounter when [they] return to civilian life and [increased] my understanding of how I could support.”

More than 1700 individual chat messages and > 80 spontaneous replies between participants were recorded during the interactive session (Table 2). Spontaneous quotes written in the chat included: “This is the best film representing the female veteran I have ever seen;” “Powerful and perspective changing;” “Thank you for sharing this incredible film;” and “I needed this to remind me to focus on woman veterans. Although our female veteran population is small it will remind me daily of their dedication, recognizing that there are so many facets of making the ultimate sacrifice.” Several participants said such programming should be a mandatory component of VA new employee orientation.

DISCUSSION

Clinician burnout diminishes empathetic patient-physician engagement. Patients’ stories are a known, powerful way to evoke empathy. This session provides one of the first examples of a straightforward approach to delivering a medical humanities intervention to a large audience via virtual platform. As measured by its high engagement, participant satisfaction, and narrative evaluations, this model was successful in evoking empathy and reinforcing the core VHA values for patient care: integrity, commitment, advocacy, respect, and excellence.

Rates of burnout and disengagement among PCPs are high and increased during the COVID-19 pandemic.2 This curriculum used a synchronous, narrative-based approach during work hours to address burnout. Lack of empathy is a cause and consequence of burnout and disengagement. Narrative approaches, especially those evoking patients’ stories can evoke empathy and help counteract such burnout. This curriculum demonstrates one of the first large-scale, narrative-based, virtual-platform approaches to utilizing patients’ stories for positive clinician impact, as evidenced by the extensive participation, engagement, and satisfaction of participants.

Individuals interested in implementing a similar program should consider common barriers, including time constraints, advertising, and clinician buy-in. Several key factors led to the successful implementation of this program. First, partnering with established educational efforts related to improving care for veterans provided time to implement the program and establish mechanisms for advertising. The VHA is a mission-driven organization; directly tying this intervention to the mission likely contributed to participant buy-in and programmatic success. Further, by partnering with established educational efforts, this session was conducted during business hours, allowing for widespread participation.

A diverse group of VHA clinicians were actively engaged throughout the session. Chat data demonstrated not only numerous responses to directed prompts, but also a larger extemporaneous conversation among participants. Additionally, it is clear participants were deeply engaged with the material. The quality of participant responses demonstrates the impact of narrative stories and included a new respect for our shared patients, a sense of humbleness as it relates to the women veteran experience, and a sense of pride in both the VHA mission and their roles as a part of the organization.

This session did not end with traditional take-home skills or reference handout resources typical of continuing education. This was intentional; the intended take-home message was the evoked emotional response and resultant perspective shift. The impact of this session on patient care will be examined in a forthcoming qualitative analysis of participants written reflections.

Limitations

Some participants noted that the chat could be distracting from the film. Others described that virtually attending the session allowed increased opportunity for interruption by ongoing patient care responsibilities, resulting in diverted attention. Many participants were granted protected time to attend this continuing education session; however, this was not always the case. Additionally, this evaluation is limited, as 40% of participants elected to not complete the postevent survey. The individuals who choose to respond may have been more engaged with the content or felt more strongly about the impact of the session. However, the volume of chat engagement during the session suggests strong participant involvement. The analysis was also limited by an electronic survey which did not allow more granular assessment of the data.

This session also raised an ethical consideration. The film evoked very strong emotional responses which, for some, were challenging to attend to personally in a large-scale virtual environment. Established clinician resources were highlighted during the session that were available for any participant who needed additional support. Participants were also encouraged to step away and process their emotions, if needed. Future interactions of this session might consider improved interparticipant chat management and upfront warnings about the emotional impact of the film accompanied by proactive dissemination of resources for participant support. One example of such resources includes breakout rooms facilitated by trained counselors. Prompts might also be adjusted to allow for more guided interparticipant engagement; facilitation can be brief as participants’ responses often carry the conversation.

CONCLUSIONS

This study shows that a large-scale, virtual medical humanities intervention is not only possible but well received, as evidenced by both quantity and quality of participant responses and engagement. The narrative approach of hearing patients’ stories, as portrayed in Journey to Normal, was found to be satisfying and appreciated by participants. Such an intervention has the potential to evoke empathy and help counteract burnout and disengagement among clinicians. This study directly aligned to the greater mission of the VHA: to improve quality medical care for all veterans, including women veterans, a subset population that is often overlooked. Organizations beyond the VHA may wish to leverage virtual learning as a mechanism to offer medical humanities to a wider audience. To optimize success, future programs should be tied to organizational missions, highlight patient voices and stories, and utilize platforms that allow for participant interactivity. Through virtual platforms, the medical humanities can reach a broader audience without detracting from its impact.

- Van Wert MJ, Gandhi S, Gupta I, et al. Healthcare worker mental health after the initial peak of the COVID- 19 pandemic: a US medical center cross-sectional survey. J Gen Intern Med. 2022;37(5):1169-1176. doi:10.1007/s11606-021-07251-0

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Vital Signs. Health workers face a mental health crisis: workers report harassment, burnout, and poor mental health; supportive workplaces can help. Updated October 24, 2023. Accessed February 18, 2025. https://www.cdc.gov/vitalsigns/health-worker-mental-health/index.html

- Holmgren AJ, Downing NL, Tang M, Sharp C, Longhurst C, Huckman RS. Assessing the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on clinician ambulatory electronic health record use. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2022;29(3):453-460. doi:10.1093/jamia/ocab268

- Apaydin EA, Mohr DC, Hamilton AB, Rose DE, Haskell S, Yano EM. Differences in burnout and intent to leave between women’s health and general primary care providers in the Veterans Health Administration. J Gen Intern Med. 2022;37(10):2382-2389. doi:10.1007/s11606-021-07133-5

- Willard-Grace R, Knox M, Huang B, Hammer H, Kivlahan C, Grumbach K. Burnout and health care workforce turnover. Ann Fam Med. 2019;17(1):36-41. doi:10.1370/afm.2338

- Rinne ST, Mohr DC, Swamy L, Blok AC, Wong ES, Charns MP. National burnout trends among physicians working in the department of veterans affairs. J Gen Intern Med. 2020;35(5):1382-1388. doi:10.1007/s11606-019-05582-7

- Spinelli WM, Fernstrom KM, Galos DL, Britt HR. Extending our understanding of burnout and its associated factors: providers and staff in primary care clinics. Eval Health Prof. 2016;39(3):282-298. doi:10.1177/0163278716637900

- Abraham CM, Zheng K, Poghosyan L. Predictors and outcomes of burnout among primary care providers in the United States: a systematic review. Med Care Res Rev. 2020;77(5):387-401. doi:10.1177/1077558719888427

- Charon R, Williams P. Introduction: the humanities and medical education. Acad Med. 1995;70(9):758-760.

- Winkel AF, Yingling S, Jones A-A, Nicholson J. Reflection as a learning tool in graduate medical education: a systematic review. J Grad Med Educ. 2017;9(4):430-439. doi:10.4300/JGME-D-16-00500.1

- Charon R. The patient-physician relationship. Narrative medicine: a model for empathy, reflection, profession, and trust. JAMA. 2001;286(15):1897-1902. doi:10.1001/jama.286.15.1897

- DasGupta S, Charon R. Personal illness narratives: using reflective writing to teach empathy. Acad Med. 2004; 79(4):351-356. doi:10.1097/00001888-200404000-00013

- Liao JM, Secemsky BJ. The value of narrative medical writing in internal medicine residency. J Gen Intern Med. 2015;30(11):1707-1710. doi:10.1007/s11606-015-3460-x

- Branch WT, Kern D, Haidet P, et al. The patient-physician relationship. Teaching the human dimensions of care in clinical settings. JAMA. 2001;286(9):1067-1074. doi:10.1001/jama.286.9.1067

- Roberts TJ, Ringler T, Krahn D, Ahearn E. The my life, my story program: sustained impact of veterans’ personal narratives on healthcare providers 5 years after implementation. Health Commun. 2021;36(7):829-836. doi:10.1080/10410236.2020.1719316

- Lam JA, Feingold-Link M, Noguchi J, et al. My life, my story: integrating a life story narrative component into medical student curricula. MedEdPORTAL. 2022;18:11211. doi:10.15766/mep_2374-8265.11211

- Van Wert MJ, Gandhi S, Gupta I, et al. Healthcare worker mental health after the initial peak of the COVID- 19 pandemic: a US medical center cross-sectional survey. J Gen Intern Med. 2022;37(5):1169-1176. doi:10.1007/s11606-021-07251-0

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Vital Signs. Health workers face a mental health crisis: workers report harassment, burnout, and poor mental health; supportive workplaces can help. Updated October 24, 2023. Accessed February 18, 2025. https://www.cdc.gov/vitalsigns/health-worker-mental-health/index.html

- Holmgren AJ, Downing NL, Tang M, Sharp C, Longhurst C, Huckman RS. Assessing the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on clinician ambulatory electronic health record use. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2022;29(3):453-460. doi:10.1093/jamia/ocab268

- Apaydin EA, Mohr DC, Hamilton AB, Rose DE, Haskell S, Yano EM. Differences in burnout and intent to leave between women’s health and general primary care providers in the Veterans Health Administration. J Gen Intern Med. 2022;37(10):2382-2389. doi:10.1007/s11606-021-07133-5

- Willard-Grace R, Knox M, Huang B, Hammer H, Kivlahan C, Grumbach K. Burnout and health care workforce turnover. Ann Fam Med. 2019;17(1):36-41. doi:10.1370/afm.2338

- Rinne ST, Mohr DC, Swamy L, Blok AC, Wong ES, Charns MP. National burnout trends among physicians working in the department of veterans affairs. J Gen Intern Med. 2020;35(5):1382-1388. doi:10.1007/s11606-019-05582-7

- Spinelli WM, Fernstrom KM, Galos DL, Britt HR. Extending our understanding of burnout and its associated factors: providers and staff in primary care clinics. Eval Health Prof. 2016;39(3):282-298. doi:10.1177/0163278716637900

- Abraham CM, Zheng K, Poghosyan L. Predictors and outcomes of burnout among primary care providers in the United States: a systematic review. Med Care Res Rev. 2020;77(5):387-401. doi:10.1177/1077558719888427

- Charon R, Williams P. Introduction: the humanities and medical education. Acad Med. 1995;70(9):758-760.

- Winkel AF, Yingling S, Jones A-A, Nicholson J. Reflection as a learning tool in graduate medical education: a systematic review. J Grad Med Educ. 2017;9(4):430-439. doi:10.4300/JGME-D-16-00500.1

- Charon R. The patient-physician relationship. Narrative medicine: a model for empathy, reflection, profession, and trust. JAMA. 2001;286(15):1897-1902. doi:10.1001/jama.286.15.1897

- DasGupta S, Charon R. Personal illness narratives: using reflective writing to teach empathy. Acad Med. 2004; 79(4):351-356. doi:10.1097/00001888-200404000-00013

- Liao JM, Secemsky BJ. The value of narrative medical writing in internal medicine residency. J Gen Intern Med. 2015;30(11):1707-1710. doi:10.1007/s11606-015-3460-x

- Branch WT, Kern D, Haidet P, et al. The patient-physician relationship. Teaching the human dimensions of care in clinical settings. JAMA. 2001;286(9):1067-1074. doi:10.1001/jama.286.9.1067

- Roberts TJ, Ringler T, Krahn D, Ahearn E. The my life, my story program: sustained impact of veterans’ personal narratives on healthcare providers 5 years after implementation. Health Commun. 2021;36(7):829-836. doi:10.1080/10410236.2020.1719316

- Lam JA, Feingold-Link M, Noguchi J, et al. My life, my story: integrating a life story narrative component into medical student curricula. MedEdPORTAL. 2022;18:11211. doi:10.15766/mep_2374-8265.11211

Hearing Patient Stories: Use of Medical Humanities on a Large-Scale, Virtual Platform to Improve Clinician Engagement

Hearing Patient Stories: Use of Medical Humanities on a Large-Scale, Virtual Platform to Improve Clinician Engagement