User login

Defect-directed reconstruction: The common-sense technique for rectocele repair

- Tears can almost always be identified without difficulty with the aid of edge-grasping clamps at surgery and a rectal examining finger.

- We can restore the natural anatomic integrity of the rectovaginal septum by reuniting the torn edges, thus eliminating the rectocele.

- The most common tears are transverse. Others include U-shaped, linear, and combined tears.

Why did it take us 2 centuries to learn how to do it right? Posterior pelvic repair for the correction of rectocele combined with restoration of the perineal body has been on gynecologic OR schedules since time immemorial, so one would think we knew what we were doing. Yet only in the past 10 years has there been progressive general recognition of the true nature of the anatomic lesions responsible for rectocele formation, thereby finally pointing us in the right direction.

Although it was always assumed, correctly, that the major factor initiating rectoceles is tissue trauma sustained in vaginal birth, traditionally we were taught, and we believed, that the end result was attenuation and deterioration of the rectovaginal septum (RVS) connective tissue. Similar tissue changes also initiated at vaginal delivery were ascribed to the proximal and distal connective tissue attachments of the RVS, respectively; the cardinal-uterosacral ligament complex; and the perineal body—but tears were never entertained in our perceptions. We know, as emphasized by Nichols in the 1960s and 1970s,1-3 that all of these elements, together with the bilateral RVS connection to levator fascia plus the levator plate of the pelvic floor, constitute the normal vaginal axis when all elements are intact.

To be concise, the disrupted vaginal axis, including its 2 major anatomic abnormalities, rectocele and perineal body defects, was thought to be the direct result of disintegration over time after the initiating shock of vaginal delivery. Specific tissue tears were, until now, an unrealized concept. As a result, we routinely resorted to makeshift methods in attempts to restore posterior pelvic configuration. Today, thanks to A. Cullen Richardson, we are much better informed.4,5

Sutured reunion of RVS tears key to rectocele eradication

This article centers on today’s concepts of the defects isolated within the RVS, a critical part of the vaginal axis. No longer is there any question about the key role of sutured reunion of RVS tears in eradicating rectocele. We must acknowledge, however, that such anatomic restoration alone is insufficient without simultaneous fixed suspension of the posterior vaginal vault above and perineal body reconstitution below, as Nichols emphasized.3

The overall goal in corrective posterior pelvic surgery must always be restoration of the normal vaginal axis in order to preserve the pelvic valve mechanism, as described by Porges.6

The primary reason for connective tissue defects is tears, not attenuation. Richardson dramatically and conclusively demonstrated this fact in the early 1990s, after prolonged and intensive investigation of the anatomy.4,5,7 This astonishing disclosure was nowhere more obvious than in the defective RVS, where discrete separations in otherwise intact tissue could be uncovered and reattached by simple standard stitching technique. We had simply never looked for these torn segments (which were never obvious), so we never found them. Once we were convinced of Richardson’s concepts, the torn edges became easily identifiable in practically every case of rectocele. Suddenly, we were able to restore the natural anatomic integrity of the RVS by reuniting these torn edges. With absolute confidence, we eliminated the rectocele.8-16

The critical digital technique

The key to this logical operative technique was the rectal examining finger. Using this digital strategy, not only could we definitively outline the rectocele on outpatient examination, but we could delineate the exact extent of the rectocele intraoperatively. This is accomplished by performing the first rectal exam just before vaginal mucosal dissection, and then, most accurately, after full dissection and exposure of the entire operative field, thus clearly exposing the torn edges in the RVS. A final anorectal exam is performed to check the restored anatomic configuration of the RVS before vaginal mucosal reunification.8

Transverse tears

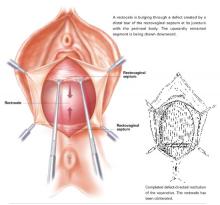

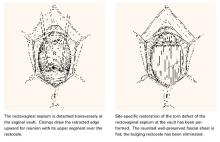

Transverse tears are the most common: either detachment from below, adjacent to the perineal body, or separation at the top in juxtaposition to the fibrous uterosacral extensions in the area of the cul-de-sac. FIGURES 1 AND 2 convey the “before and after” aspects, showing Allis clamps drawing the retracted edge to the site of the tear followed by the revelation of the actual repair accomplished by interrupted O-caliber sutures, either delayed absorbable or nonabsorbable. A rectally inserted index finger initially demonstrates that, except for scraps of areolar tissue, the anorectal wall is the only layer that prevents the examining finger from falling into the operative field as it produces rectocele simulation with forward pressure. When the clamps draw the long-torn RVS segments into normal anatomic positions, the anorectal finger cannot advance at all, despite strong effort, because of the natural firm barrier effect of the anatomically restored RVS.8

FIGURE 1 Lower transverse tear

FIGURE 2 Upper transverse tear

U-shaped tears

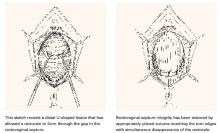

Another not uncommon type of defect can be U-shaped, either at the bottom, as depicted in FIGURE 3, or at the top of the posterior pelvic compartment. Similarly linear (longitudinal) tears near one side or the other directly adjacent to the pelvic sidewalls, rarely in the midline, are not unusual and can be repaired in the same manner.

FIGURE 3 U-shaped tear

Hockey-stick tears

Occasionally, a hockey-stick lesion, combining a longitudinal tear and a transverse tear in continuity, as shown in FIGURE 4, is discovered.

FIGURE 4 Hockey-stick tear

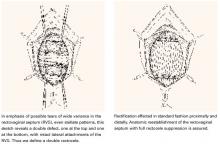

Double defect

A more uncommon type of combined or double defect, in which the Denonvilliers fascia (RVS) has been torn both adjacent to the vault and in the perineal area but retains strong attachments bilaterally, is shown in FIGURE 5.

FIGURE 5 Double defect

A contented vaginal environment

The major breakthrough is the concept that tears in the Denonvilliers fascia, not attenuation, are the cause of rectoceles. These tears—transverse, longitudinal, U-shaped, multidirectional, even stellate—can be identified almost always without difficulty with the aid of a rectal examining finger and edge-grasping clamps at surgery. The repair itself is not only anatomically logical but also much easier and more confidence-inspiring than the traditional, now archaic, method of fishing around for scraps of levator fascia and muscle to approximate, under tension, in the midline.

This defect-directed repair, born of common sense (ie, comprehension and application of normal anatomy), is structurally nonconstrictive and functionally nonrestrictive—truly a contented vaginal environment.

All sketches from TeLinde’s Operative Gynecology, 9th edition, with permission from Lippincott, Williams, and Wilkins, Publishers.

Dr. Grody reports no financial relationship with any companies whose products are mentioned in this article.

1. Nichols DH. Posterior colporrhaphy and perineorrhaphy: separate and distinct operations. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1991;164:714-721.

2. Nichols DH, Milley PS, Randall CL. Significance of restoration of normal vaginal depth and axis. Obstet Gynecol. 1970;36:251-256.

3. Nichols DH, Randall CS. Vaginal Surgery. 3rd ed. Baltimore, Md: Williams & Wilkins; 1989;21.-

4. Richardson AC. The rectovaginal septum revisited: its relationship to rectocele and its importance to rectocele repair. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 1993;36:976-983.

5. Richardson AC. The anatomic defects in rectocele and enterocele. J Pelv Surg. 1995;1:214.-

6. Porges RF, Sinden SW. Long-term analysis of the surgical management of pelvic support defects. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1994;171:1518-1528.

7. Edmonds PB, Richardson AC. Anatomical Approach to Rectocele Repair [videotape]. St. Louis, Mo: Society of Gynecologic Surgeons; 1993.

8. Grody MHT. Posterior compartment defects. In: Rock JA, Jones III HW, eds. TeLinde’s Operative Gynecology. 9th ed. Philadelphia, Pa: Lippincott, Williams and Wilkins; 2003;966-985.

9. Cundiff GW, Weidner AC, Visco AG, Addison WA, Bump RC. An anatomic and functional assessment of the discrete defect rectocele repair. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1998;179:1456-1457.

10. Kenton K, Shott S, Brubaker L. Outcome after rectovaginal fascia reattachment for rectocele repair. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1999;181:360-364.

11. Porter WE, Steele A, Walsh P, Kohli N, Karram MM. The anatomic and functional outcomes of defect-specific rectocele repairs. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1999;181:1353-13549.

12. Glavind K, Madsen H. A prospective study of the discrete fascial defect rectocele repair. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2000;79:145-147.

13. Cundiff GW. Defect Directed Rectocele Repairs: Restorative and Compensatory Techniques [videotape]. Washington, DC: American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists; 2001.

14. Maccarone JL, Caraballo R, Holzberg A, Grody MHT. Innovative Defect-specific Posterior Pelvic Surgery: Triggered Ligament Sutures and Collagen Graft [videotape]. Washington, DC: American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists; 2003.

15. Caraballo R, Maccarone JL, Holzberg AS, Grody MHT. New Concepts in Reconstructive Pelvic Surgery: Slings, Collagen Matrix Grafts, Triggered Sutures [videotape]. Washington, DC: American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists; 2003.

16. Singh K, Cortes E, Reid WMN. Evaluation of the fascial technique for surgical repair of isolated posterior vaginal wall prolapse. Obstet Gynecol. 2003;101:320-324.

- Tears can almost always be identified without difficulty with the aid of edge-grasping clamps at surgery and a rectal examining finger.

- We can restore the natural anatomic integrity of the rectovaginal septum by reuniting the torn edges, thus eliminating the rectocele.

- The most common tears are transverse. Others include U-shaped, linear, and combined tears.

Why did it take us 2 centuries to learn how to do it right? Posterior pelvic repair for the correction of rectocele combined with restoration of the perineal body has been on gynecologic OR schedules since time immemorial, so one would think we knew what we were doing. Yet only in the past 10 years has there been progressive general recognition of the true nature of the anatomic lesions responsible for rectocele formation, thereby finally pointing us in the right direction.

Although it was always assumed, correctly, that the major factor initiating rectoceles is tissue trauma sustained in vaginal birth, traditionally we were taught, and we believed, that the end result was attenuation and deterioration of the rectovaginal septum (RVS) connective tissue. Similar tissue changes also initiated at vaginal delivery were ascribed to the proximal and distal connective tissue attachments of the RVS, respectively; the cardinal-uterosacral ligament complex; and the perineal body—but tears were never entertained in our perceptions. We know, as emphasized by Nichols in the 1960s and 1970s,1-3 that all of these elements, together with the bilateral RVS connection to levator fascia plus the levator plate of the pelvic floor, constitute the normal vaginal axis when all elements are intact.

To be concise, the disrupted vaginal axis, including its 2 major anatomic abnormalities, rectocele and perineal body defects, was thought to be the direct result of disintegration over time after the initiating shock of vaginal delivery. Specific tissue tears were, until now, an unrealized concept. As a result, we routinely resorted to makeshift methods in attempts to restore posterior pelvic configuration. Today, thanks to A. Cullen Richardson, we are much better informed.4,5

Sutured reunion of RVS tears key to rectocele eradication

This article centers on today’s concepts of the defects isolated within the RVS, a critical part of the vaginal axis. No longer is there any question about the key role of sutured reunion of RVS tears in eradicating rectocele. We must acknowledge, however, that such anatomic restoration alone is insufficient without simultaneous fixed suspension of the posterior vaginal vault above and perineal body reconstitution below, as Nichols emphasized.3

The overall goal in corrective posterior pelvic surgery must always be restoration of the normal vaginal axis in order to preserve the pelvic valve mechanism, as described by Porges.6

The primary reason for connective tissue defects is tears, not attenuation. Richardson dramatically and conclusively demonstrated this fact in the early 1990s, after prolonged and intensive investigation of the anatomy.4,5,7 This astonishing disclosure was nowhere more obvious than in the defective RVS, where discrete separations in otherwise intact tissue could be uncovered and reattached by simple standard stitching technique. We had simply never looked for these torn segments (which were never obvious), so we never found them. Once we were convinced of Richardson’s concepts, the torn edges became easily identifiable in practically every case of rectocele. Suddenly, we were able to restore the natural anatomic integrity of the RVS by reuniting these torn edges. With absolute confidence, we eliminated the rectocele.8-16

The critical digital technique

The key to this logical operative technique was the rectal examining finger. Using this digital strategy, not only could we definitively outline the rectocele on outpatient examination, but we could delineate the exact extent of the rectocele intraoperatively. This is accomplished by performing the first rectal exam just before vaginal mucosal dissection, and then, most accurately, after full dissection and exposure of the entire operative field, thus clearly exposing the torn edges in the RVS. A final anorectal exam is performed to check the restored anatomic configuration of the RVS before vaginal mucosal reunification.8

Transverse tears

Transverse tears are the most common: either detachment from below, adjacent to the perineal body, or separation at the top in juxtaposition to the fibrous uterosacral extensions in the area of the cul-de-sac. FIGURES 1 AND 2 convey the “before and after” aspects, showing Allis clamps drawing the retracted edge to the site of the tear followed by the revelation of the actual repair accomplished by interrupted O-caliber sutures, either delayed absorbable or nonabsorbable. A rectally inserted index finger initially demonstrates that, except for scraps of areolar tissue, the anorectal wall is the only layer that prevents the examining finger from falling into the operative field as it produces rectocele simulation with forward pressure. When the clamps draw the long-torn RVS segments into normal anatomic positions, the anorectal finger cannot advance at all, despite strong effort, because of the natural firm barrier effect of the anatomically restored RVS.8

FIGURE 1 Lower transverse tear

FIGURE 2 Upper transverse tear

U-shaped tears

Another not uncommon type of defect can be U-shaped, either at the bottom, as depicted in FIGURE 3, or at the top of the posterior pelvic compartment. Similarly linear (longitudinal) tears near one side or the other directly adjacent to the pelvic sidewalls, rarely in the midline, are not unusual and can be repaired in the same manner.

FIGURE 3 U-shaped tear

Hockey-stick tears

Occasionally, a hockey-stick lesion, combining a longitudinal tear and a transverse tear in continuity, as shown in FIGURE 4, is discovered.

FIGURE 4 Hockey-stick tear

Double defect

A more uncommon type of combined or double defect, in which the Denonvilliers fascia (RVS) has been torn both adjacent to the vault and in the perineal area but retains strong attachments bilaterally, is shown in FIGURE 5.

FIGURE 5 Double defect

A contented vaginal environment

The major breakthrough is the concept that tears in the Denonvilliers fascia, not attenuation, are the cause of rectoceles. These tears—transverse, longitudinal, U-shaped, multidirectional, even stellate—can be identified almost always without difficulty with the aid of a rectal examining finger and edge-grasping clamps at surgery. The repair itself is not only anatomically logical but also much easier and more confidence-inspiring than the traditional, now archaic, method of fishing around for scraps of levator fascia and muscle to approximate, under tension, in the midline.

This defect-directed repair, born of common sense (ie, comprehension and application of normal anatomy), is structurally nonconstrictive and functionally nonrestrictive—truly a contented vaginal environment.

All sketches from TeLinde’s Operative Gynecology, 9th edition, with permission from Lippincott, Williams, and Wilkins, Publishers.

Dr. Grody reports no financial relationship with any companies whose products are mentioned in this article.

- Tears can almost always be identified without difficulty with the aid of edge-grasping clamps at surgery and a rectal examining finger.

- We can restore the natural anatomic integrity of the rectovaginal septum by reuniting the torn edges, thus eliminating the rectocele.

- The most common tears are transverse. Others include U-shaped, linear, and combined tears.

Why did it take us 2 centuries to learn how to do it right? Posterior pelvic repair for the correction of rectocele combined with restoration of the perineal body has been on gynecologic OR schedules since time immemorial, so one would think we knew what we were doing. Yet only in the past 10 years has there been progressive general recognition of the true nature of the anatomic lesions responsible for rectocele formation, thereby finally pointing us in the right direction.

Although it was always assumed, correctly, that the major factor initiating rectoceles is tissue trauma sustained in vaginal birth, traditionally we were taught, and we believed, that the end result was attenuation and deterioration of the rectovaginal septum (RVS) connective tissue. Similar tissue changes also initiated at vaginal delivery were ascribed to the proximal and distal connective tissue attachments of the RVS, respectively; the cardinal-uterosacral ligament complex; and the perineal body—but tears were never entertained in our perceptions. We know, as emphasized by Nichols in the 1960s and 1970s,1-3 that all of these elements, together with the bilateral RVS connection to levator fascia plus the levator plate of the pelvic floor, constitute the normal vaginal axis when all elements are intact.

To be concise, the disrupted vaginal axis, including its 2 major anatomic abnormalities, rectocele and perineal body defects, was thought to be the direct result of disintegration over time after the initiating shock of vaginal delivery. Specific tissue tears were, until now, an unrealized concept. As a result, we routinely resorted to makeshift methods in attempts to restore posterior pelvic configuration. Today, thanks to A. Cullen Richardson, we are much better informed.4,5

Sutured reunion of RVS tears key to rectocele eradication

This article centers on today’s concepts of the defects isolated within the RVS, a critical part of the vaginal axis. No longer is there any question about the key role of sutured reunion of RVS tears in eradicating rectocele. We must acknowledge, however, that such anatomic restoration alone is insufficient without simultaneous fixed suspension of the posterior vaginal vault above and perineal body reconstitution below, as Nichols emphasized.3

The overall goal in corrective posterior pelvic surgery must always be restoration of the normal vaginal axis in order to preserve the pelvic valve mechanism, as described by Porges.6

The primary reason for connective tissue defects is tears, not attenuation. Richardson dramatically and conclusively demonstrated this fact in the early 1990s, after prolonged and intensive investigation of the anatomy.4,5,7 This astonishing disclosure was nowhere more obvious than in the defective RVS, where discrete separations in otherwise intact tissue could be uncovered and reattached by simple standard stitching technique. We had simply never looked for these torn segments (which were never obvious), so we never found them. Once we were convinced of Richardson’s concepts, the torn edges became easily identifiable in practically every case of rectocele. Suddenly, we were able to restore the natural anatomic integrity of the RVS by reuniting these torn edges. With absolute confidence, we eliminated the rectocele.8-16

The critical digital technique

The key to this logical operative technique was the rectal examining finger. Using this digital strategy, not only could we definitively outline the rectocele on outpatient examination, but we could delineate the exact extent of the rectocele intraoperatively. This is accomplished by performing the first rectal exam just before vaginal mucosal dissection, and then, most accurately, after full dissection and exposure of the entire operative field, thus clearly exposing the torn edges in the RVS. A final anorectal exam is performed to check the restored anatomic configuration of the RVS before vaginal mucosal reunification.8

Transverse tears

Transverse tears are the most common: either detachment from below, adjacent to the perineal body, or separation at the top in juxtaposition to the fibrous uterosacral extensions in the area of the cul-de-sac. FIGURES 1 AND 2 convey the “before and after” aspects, showing Allis clamps drawing the retracted edge to the site of the tear followed by the revelation of the actual repair accomplished by interrupted O-caliber sutures, either delayed absorbable or nonabsorbable. A rectally inserted index finger initially demonstrates that, except for scraps of areolar tissue, the anorectal wall is the only layer that prevents the examining finger from falling into the operative field as it produces rectocele simulation with forward pressure. When the clamps draw the long-torn RVS segments into normal anatomic positions, the anorectal finger cannot advance at all, despite strong effort, because of the natural firm barrier effect of the anatomically restored RVS.8

FIGURE 1 Lower transverse tear

FIGURE 2 Upper transverse tear

U-shaped tears

Another not uncommon type of defect can be U-shaped, either at the bottom, as depicted in FIGURE 3, or at the top of the posterior pelvic compartment. Similarly linear (longitudinal) tears near one side or the other directly adjacent to the pelvic sidewalls, rarely in the midline, are not unusual and can be repaired in the same manner.

FIGURE 3 U-shaped tear

Hockey-stick tears

Occasionally, a hockey-stick lesion, combining a longitudinal tear and a transverse tear in continuity, as shown in FIGURE 4, is discovered.

FIGURE 4 Hockey-stick tear

Double defect

A more uncommon type of combined or double defect, in which the Denonvilliers fascia (RVS) has been torn both adjacent to the vault and in the perineal area but retains strong attachments bilaterally, is shown in FIGURE 5.

FIGURE 5 Double defect

A contented vaginal environment

The major breakthrough is the concept that tears in the Denonvilliers fascia, not attenuation, are the cause of rectoceles. These tears—transverse, longitudinal, U-shaped, multidirectional, even stellate—can be identified almost always without difficulty with the aid of a rectal examining finger and edge-grasping clamps at surgery. The repair itself is not only anatomically logical but also much easier and more confidence-inspiring than the traditional, now archaic, method of fishing around for scraps of levator fascia and muscle to approximate, under tension, in the midline.

This defect-directed repair, born of common sense (ie, comprehension and application of normal anatomy), is structurally nonconstrictive and functionally nonrestrictive—truly a contented vaginal environment.

All sketches from TeLinde’s Operative Gynecology, 9th edition, with permission from Lippincott, Williams, and Wilkins, Publishers.

Dr. Grody reports no financial relationship with any companies whose products are mentioned in this article.

1. Nichols DH. Posterior colporrhaphy and perineorrhaphy: separate and distinct operations. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1991;164:714-721.

2. Nichols DH, Milley PS, Randall CL. Significance of restoration of normal vaginal depth and axis. Obstet Gynecol. 1970;36:251-256.

3. Nichols DH, Randall CS. Vaginal Surgery. 3rd ed. Baltimore, Md: Williams & Wilkins; 1989;21.-

4. Richardson AC. The rectovaginal septum revisited: its relationship to rectocele and its importance to rectocele repair. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 1993;36:976-983.

5. Richardson AC. The anatomic defects in rectocele and enterocele. J Pelv Surg. 1995;1:214.-

6. Porges RF, Sinden SW. Long-term analysis of the surgical management of pelvic support defects. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1994;171:1518-1528.

7. Edmonds PB, Richardson AC. Anatomical Approach to Rectocele Repair [videotape]. St. Louis, Mo: Society of Gynecologic Surgeons; 1993.

8. Grody MHT. Posterior compartment defects. In: Rock JA, Jones III HW, eds. TeLinde’s Operative Gynecology. 9th ed. Philadelphia, Pa: Lippincott, Williams and Wilkins; 2003;966-985.

9. Cundiff GW, Weidner AC, Visco AG, Addison WA, Bump RC. An anatomic and functional assessment of the discrete defect rectocele repair. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1998;179:1456-1457.

10. Kenton K, Shott S, Brubaker L. Outcome after rectovaginal fascia reattachment for rectocele repair. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1999;181:360-364.

11. Porter WE, Steele A, Walsh P, Kohli N, Karram MM. The anatomic and functional outcomes of defect-specific rectocele repairs. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1999;181:1353-13549.

12. Glavind K, Madsen H. A prospective study of the discrete fascial defect rectocele repair. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2000;79:145-147.

13. Cundiff GW. Defect Directed Rectocele Repairs: Restorative and Compensatory Techniques [videotape]. Washington, DC: American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists; 2001.

14. Maccarone JL, Caraballo R, Holzberg A, Grody MHT. Innovative Defect-specific Posterior Pelvic Surgery: Triggered Ligament Sutures and Collagen Graft [videotape]. Washington, DC: American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists; 2003.

15. Caraballo R, Maccarone JL, Holzberg AS, Grody MHT. New Concepts in Reconstructive Pelvic Surgery: Slings, Collagen Matrix Grafts, Triggered Sutures [videotape]. Washington, DC: American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists; 2003.

16. Singh K, Cortes E, Reid WMN. Evaluation of the fascial technique for surgical repair of isolated posterior vaginal wall prolapse. Obstet Gynecol. 2003;101:320-324.

1. Nichols DH. Posterior colporrhaphy and perineorrhaphy: separate and distinct operations. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1991;164:714-721.

2. Nichols DH, Milley PS, Randall CL. Significance of restoration of normal vaginal depth and axis. Obstet Gynecol. 1970;36:251-256.

3. Nichols DH, Randall CS. Vaginal Surgery. 3rd ed. Baltimore, Md: Williams & Wilkins; 1989;21.-

4. Richardson AC. The rectovaginal septum revisited: its relationship to rectocele and its importance to rectocele repair. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 1993;36:976-983.

5. Richardson AC. The anatomic defects in rectocele and enterocele. J Pelv Surg. 1995;1:214.-

6. Porges RF, Sinden SW. Long-term analysis of the surgical management of pelvic support defects. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1994;171:1518-1528.

7. Edmonds PB, Richardson AC. Anatomical Approach to Rectocele Repair [videotape]. St. Louis, Mo: Society of Gynecologic Surgeons; 1993.

8. Grody MHT. Posterior compartment defects. In: Rock JA, Jones III HW, eds. TeLinde’s Operative Gynecology. 9th ed. Philadelphia, Pa: Lippincott, Williams and Wilkins; 2003;966-985.

9. Cundiff GW, Weidner AC, Visco AG, Addison WA, Bump RC. An anatomic and functional assessment of the discrete defect rectocele repair. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1998;179:1456-1457.

10. Kenton K, Shott S, Brubaker L. Outcome after rectovaginal fascia reattachment for rectocele repair. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1999;181:360-364.

11. Porter WE, Steele A, Walsh P, Kohli N, Karram MM. The anatomic and functional outcomes of defect-specific rectocele repairs. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1999;181:1353-13549.

12. Glavind K, Madsen H. A prospective study of the discrete fascial defect rectocele repair. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2000;79:145-147.

13. Cundiff GW. Defect Directed Rectocele Repairs: Restorative and Compensatory Techniques [videotape]. Washington, DC: American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists; 2001.

14. Maccarone JL, Caraballo R, Holzberg A, Grody MHT. Innovative Defect-specific Posterior Pelvic Surgery: Triggered Ligament Sutures and Collagen Graft [videotape]. Washington, DC: American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists; 2003.

15. Caraballo R, Maccarone JL, Holzberg AS, Grody MHT. New Concepts in Reconstructive Pelvic Surgery: Slings, Collagen Matrix Grafts, Triggered Sutures [videotape]. Washington, DC: American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists; 2003.

16. Singh K, Cortes E, Reid WMN. Evaluation of the fascial technique for surgical repair of isolated posterior vaginal wall prolapse. Obstet Gynecol. 2003;101:320-324.