User login

POLST: An improvement over traditional advance directives

An 89-year-old woman with advanced dementia is living in a nursing home and is fully dependent in all aspects of personal care, including feeding. She has a health care proxy and a living will.

Her husband is her health care agent and has established that the primary goal of her care should be to keep her comfortable. He has repeatedly discussed this goal with her attending physician and the nursing-home staff and has reiterated that when his wife had capacity, she wanted “no heroics,” “no feeding tube,” and no life-sustaining treatment that would prolong her dying. He has requested that she not be transferred to the hospital and that she receive all further care at the nursing home. These preferences are consistent with her living will.

One evening, she becomes somnolent and febrile, with rapid breathing. The physician covering for the attending physician does not know the patient, cannot reach her husband, and sends her to the hospital, where she is admitted with aspiration pneumonia.

Her level of alertness improves with hydration. However, the hospital nurses have a difficult time feeding her. She does not seem to want to eat, “pockets” food in her cheeks, is slow to swallow, and sometimes coughs during feeding. This is nothing new—at the nursing home, her feeding pattern had been the same for nearly 6 months. During this time she always had a cough; fevers came and went. She has slowly lost weight; she now weighs 100 lb (45 kg), down 30 lb (14 kg) in 3 years.

With treatment, her respiratory distress and fever resolve. The physician orders a swallowing evaluation by a speech therapist, who determines that she needs a feeding tube. After that, a meeting is scheduled with her husband and physician to discuss the speech therapist’s assessment. The patient’s husband emphatically refuses the feeding tube and is upset that she was transferred to the hospital against his expressed wishes.

Why did this happen?

TRADITIONAL ADVANCE DIRECTIVES ARE OFTEN NOT ENOUGH

Even when patients fill out advance directives in accordance with state law, their preferences for care at the end of life are not consistently followed.

Problems with living wills

Living wills state patients’ wishes about medical care in the event that they develop an irreversible condition that prevents them from making their own medical decisions. The living will becomes effective if they become terminally ill, permanently unconscious, or minimally conscious due to brain damage and will never regain the ability to make decisions. People who want to indicate under what set of circumstances they favor or object to receiving any specific treatments use a living will.

The Patient Self-Determination Act of 1990 states that on admission to a hospital or nursing home, patients have to be informed of their rights, including the right to accept or refuse treatment.1 However, the current system of communicating wishes about end-of-life care using solely traditional advance directives such as the living will has proven insufficient. This is because traditional advance directives, being general statements of patients’ preferences, need to be carried out through specifications in medical orders when the need arises.2

Further, traditional advance directives require patients to recognize the importance of advance care planning, understand medical interventions, evaluate their own personal values and beliefs, and communicate their wishes to their agents, loved ones, physicians, and health care providers. Moreover, these documents apply to future circumstances, require further interpretation by the agent and health care professionals, and do not result in actionable medical orders. Decisions about care depend on interpreting earlier conversations, the physician’s estimates of prognosis, and, possibly, the personal convictions of the physician, agent, and loved ones, even though ethically, all involved need to focus on the patient’s stated wishes or best interest. A living will does not help clarify the patient’s wishes in the absence of antecedent conversation with the family, close friends, and the patient’s personal physician. And living wills cannot be read and interpreted in an emergency.

The situation is further complicated by difficulty in defining “terminal” or “irreversible” conditions and accounting for the different perspective that physicians, agents, and loved ones bring to the situation. For example, imagine a patient with dementia nearing the end of life who eats less, has difficulty managing secretions, aspirates, and develops pneumonia. While end-stage dementia is terminal, pneumonia may be reversible.

Increasingly, therefore, people are being counseled to appoint a health care agent (see below).3

The importance of a health care proxy (durable power of attorney for health care)

In a health care proxy document (also known as durable power of attorney for health care), the patient names a health care agent. This person has authority to make decisions about the patient’s medical care, including life-sustaining treatment. In other words, you the patient appoint someone to speak for you in the event you are unable to make your own medical decisions (not only at the end of life).

Since anyone may face a sudden and unexpected acute illness or injury with the risk of becoming incapacitated and unable to make medical decisions, everyone age 18 and older should be encouraged to complete a health care proxy document and to engage in advance care planning discussions with family and loved ones. Physicians can initiate this process as a wellness initiative and can help patients and families understand advance care planning. In all health care settings, trained and qualified health care professionals can provide education on advance care planning to patients, families, and loved ones.

A key issue when naming a health care agent is choosing the right one, someone who will make decisions in accordance with the person’s current values and beliefs and who can separate his or her personal values from the patient’s values. Another key issue: people need to have proactive discussions about their personal values, beliefs, and goals of care, which many are reluctant to do, and the health care agent must be willing to talk about sensitive issues ahead of time. Even when a health care agent is available in an emergency, emergency medical services personnel cannot follow directions from a health care agent. Most importantly, a health care agent must be able to handle potential conflicts between family and providers.

POLST ENSURES PATIENT PREFERENCES ARE HONORED AT THE END OF LIFE

Approximately 20 years ago, a team of health care professionals at the University of Oregon recognized these problems and realized that physicians needed to be more involved in discussions with patients about end-of-life care and in translating the patient’s preferences and values into concrete medical orders. The result was the Physician Orders for Life-Sustaining Treatment (POLST) Paradigm Program.4

What is POLST?

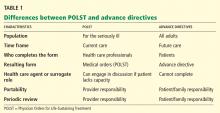

POLST is an end-of-life-care transitions program that focuses on patient-centered goals for care and shared informed medical decision-making.5,6 It offers a mechanism to communicate the wishes of seriously ill patients to have or to limit medical treatment as they move from one care setting to another. Table 1 lists the differences between traditional advance directives and POLST.

The aim is to improve the quality of care that seriously ill patients receive at the end of life. POLST is based on effective communication of the patient’s wishes, with actionable medical orders documented on a brightly colored form (www.ohsu.edu/polst/programs/sample-forms.htm; Figure 1) and a promise by health care professionals to honor these wishes.7 Key features of the program include education, training, and a quality-improvement process.

Who is POLST for?

POLST is for patients with serious life-limiting illness who have a life expectancy of less than 1 year, or anyone of advanced age interested in defining their end-of-life care wishes. Qualified and trained health care professionals (physicians, physician’s assistants, nurse practitioners, and social workers) participate in discussions leading to the completion of a POLST form in all settings, particularly along the long-term care continuum and for home hospice.

The key element of the POLST process: Shared, informed medical decision-making

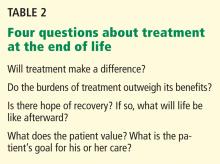

Health care professionals working as an interdisciplinary team play a key role in educating patients and their families about advance care planning and shared, informed medical decision-making, as well as in resolving conflict. To be effective, shared medical decision-making must be well-informed. The decision-maker (patient, health care agent, or surrogate) must weigh the following questions (Table 2):

- Will treatment make a difference?

- Do the burdens of treatment outweigh its benefits?

- Is there hope of recovery? If so, what will life be like afterward?

- What does the patient value? What is the patient’s goal for his or her care?

In-depth discussions with patients, family members, and surrogates are needed, and these people are often reluctant to ask these questions and afraid to discuss the dying process. Even if they are informed of their diagnosis and prognosis, they may not know what they mean in terms of their everyday experience and future.

Health care professionals engaging in these conversations can use the eight-step POLST protocol (Table 3) to elicit their preferences at the end of life. Table 4 lists tools and resources to enhance the understanding of advance care planning and POLST.

What does the POLST form cover?

The POLST form (Figure 1) provides instructions about resuscitation if the patient has no pulse and is not breathing. Additionally, the medical orders indicate decisions about the level of medical intervention that the patient wants or does not want, eg, intubation, mechanical ventilation, transport to the hospital, intensive care, artificial nutrition and hydration, and antibiotics.

Thus, POLST is outcome-neutral and can be used either to limit medical interventions or to clarify a request for any or all medically indicated treatments.

Both the practitioner and the patient or patient’s surrogate sign the form. The original goes into the patient’s chart, and a copy should accompany the patient if he or she is transferred or discharged. Additionally, if the state has a POLST registry, the POLST information should be entered into the registry.

POLST is expanding across the country

The use of POLST has been expanding across the United States, with POLST programs now implemented in all or part of at least 30 states. There are endorsed programs in 14 states, and programs are being developed in 26 more. Requirements for endorsement are found at www.polst.org. Figure 2 shows the status of POLST in the 50 states.

Oregon’s POLST form is the original model for other forms designed to meet specific legislative or regulatory requirements in other states. POLST-like programs are known by different names in different states: eg, New York’s Medical Orders for Life-Sustaining Treatment (MOLST) and West Virginia’s Physicians Orders for Scope of Treatment (POST), but all endorsed programs share common core elements.

POLST research

A number of studies in the past 10 years have shown that POLST improves the documentation and honoring of patient preferences, whatever they may be.4,8–16

Emergency medical technicians in Oregon reported that the POLST form provides clear instructions about patient preferences and is useful when deciding which treatments to provide. In contrast to the single-intervention focus of out-of-hospital do-not-resuscitate orders, the POLST form provides patients the opportunity to document treatment goals and preferences for interventions across a range of treatment options, thus permitting greater individualization.13

Comfort care is not sacrificed if a POLST document is in place. Most hospice patients choose at least one life-sustaining treatment on their POLST form.14

In a multistate study published in 2010, the medical records of residents in 90 randomly chosen Medicaid-eligible nursing homes were reviewed.15 POLST was compared with traditional advance care planning in terms of the effect on the presence of medical orders reflecting treatment preferences, symptom management, and use of life-sustaining treatments. The study found that residents with POLST forms had significantly more medical orders about life-sustaining treatments than residents with traditional advance directives. There were no differences between residents with or without POLST forms on symptom assessment or management measures. POLST was more effective than traditional advance planning at limiting unwanted life-sustaining treatments. The study suggests that POLST offers significant advantages over traditional advance directives in nursing facilities.15,16

In summary, more than a decade of research has shown that the POLST Paradigm Program serves as an emerging national model for implementing shared, informed medical decision-making. Furthermore, POLST more accurately conveys end-of-life care preferences for patients with advanced chronic illness and for dying patients than traditional advance directives and yields higher adherence by medical professionals.

CLINICAL CASE REVISITED

Let’s consider if the physician for our 89-year-old woman with dementia had completed a POLST form with orders indicating “do not attempt resuscitation (DNR/no CPR)” and “comfort measures only, do not transfer to hospital for life-sustaining treatment and transfer if comfort needs cannot be met in current location.”

The patient’s respiratory distress and fever would have been treated at her nursing home with medication and oxygen. She would have been transferred to the hospital only if her comfort needs would not have been met at the nursing home. Unwanted life-sustaining treatment would have been avoided. The wishes of the patient, based on her values and careful consideration of options, would have been respected.

- Dunn PM, Tolle SW, Moss AH, Black JS. The POLST paradigm: respecting the wishes of patients and families. Ann Long-Term Care 2007; 15:33–40.

- Patient Self-Determination Act of 1990. Pub. L. No. 101-508, ss 4206, 104 Stat. 1388.

- Bomba PA, Sabatino CP. POLST: an emerging model for end-of-life care planning. The ElderLaw Report 2009; 20:1–5.

- Karp Sabatino C. AARP Public Policy Institute, Improving advance illness care: the evolution of state POLST programs 2011. http://assets.aarp.org/rgcenter/ppi/cons-prot/POLST-Report-04-11.pdf. Accessed May 30, 2012.

- Bomba PA. Discussing patient p and end of life care, Journal of the Monroe County Medical Society, 7th District Branch, MSSNY 2011;12–15. www.compassionandsupport.org/index.php/research_/. Accessed May 30, 2012.

- Citko J, Moss AH, Carley M, Tolle SW. The National POLST Paradigm Initiative, 2ND ed. Fast Facts and Concepts 2010;178. www.eperc.mcw.edu/fastfact/ff_178.htm. Accessed May 30, 2012.

- Center for Ethics in Health Care, Oregon Health & Science University. www.ohsu.edu/polst/. Accessed May 30, 2012.

- Lee MA, Brummel-Smith K, Meyer J, Drew N, London MR. Physician orders for life-sustaining treatment (POLST): outcomes in a PACE program. Program of All-Inclusive Care for the Elderly. J Am Geriatr Soc 2000; 48:1219–1225.

- Meyers JL, Moore C, McGrory A, Sparr J, Ahern M. Physician orders for life-sustaining treatment form: honoring end-of-life directives for nursing home residents. J Gerontol Nurs 2004; 30:37–46.

- Dunn PM, Schmidt TA, Carley MM, Donius M, Weinstein MA, Dull VT. A method to communicate patient p about medically indicated life-sustaining treatment in the out-of-hospital setting. J Am Geriatr Soc 1996; 44:785–791.

- Cantor MD. Improving advance care planning: lessons from POLST. Physician Orders for Life-Sustaining Treatment (comment). J Am Geriatr Soc 2000; 48:1343–1344.

- Tolle SW, Tilden VP, Nelson CA, Dunn PM. A prospective study of the efficacy of the physician order form for life-sustaining treatment. J Am Geriatr Soc 1998; 46:1097–1102.

- Schmidt TA, Hickman SE, Tolle SW, Brooks HS. The Physician Orders for Life-Sustaining Treatment program: Oregon emergency medical technicians’ practical experiences and attitudes. J Am Geriatr Soc 2004; 52:1430–1434.

- Hickman SE, Nelson CA, Moss AH, et al. Use of the Physician Orders for Life-Sustaining Treatment (POLST) paradigm program in the hospice setting. J Palliat Med 2009; 12:133–141.

- Hickman SE, Nelson CA, Perrin NA, Moss AH, Hammes BJ, Tolle SW. A comparison of methods to communicate treatment p in nursing facilities: traditional practices versus the physician orders for life-sustaining treatment program. J Am Geriatr Soc 2010; 58:1241–1248.

- Hickman SE, Nelson CA, Moss AH, Tolle SW, Perrin NA, Hammes BJ. The consistency between treatments provided to nursing facility residents and orders on the physician orders for life-sustaining treatment form. J Am Geriatr Soc 2011; 59:2091–2099.

An 89-year-old woman with advanced dementia is living in a nursing home and is fully dependent in all aspects of personal care, including feeding. She has a health care proxy and a living will.

Her husband is her health care agent and has established that the primary goal of her care should be to keep her comfortable. He has repeatedly discussed this goal with her attending physician and the nursing-home staff and has reiterated that when his wife had capacity, she wanted “no heroics,” “no feeding tube,” and no life-sustaining treatment that would prolong her dying. He has requested that she not be transferred to the hospital and that she receive all further care at the nursing home. These preferences are consistent with her living will.

One evening, she becomes somnolent and febrile, with rapid breathing. The physician covering for the attending physician does not know the patient, cannot reach her husband, and sends her to the hospital, where she is admitted with aspiration pneumonia.

Her level of alertness improves with hydration. However, the hospital nurses have a difficult time feeding her. She does not seem to want to eat, “pockets” food in her cheeks, is slow to swallow, and sometimes coughs during feeding. This is nothing new—at the nursing home, her feeding pattern had been the same for nearly 6 months. During this time she always had a cough; fevers came and went. She has slowly lost weight; she now weighs 100 lb (45 kg), down 30 lb (14 kg) in 3 years.

With treatment, her respiratory distress and fever resolve. The physician orders a swallowing evaluation by a speech therapist, who determines that she needs a feeding tube. After that, a meeting is scheduled with her husband and physician to discuss the speech therapist’s assessment. The patient’s husband emphatically refuses the feeding tube and is upset that she was transferred to the hospital against his expressed wishes.

Why did this happen?

TRADITIONAL ADVANCE DIRECTIVES ARE OFTEN NOT ENOUGH

Even when patients fill out advance directives in accordance with state law, their preferences for care at the end of life are not consistently followed.

Problems with living wills

Living wills state patients’ wishes about medical care in the event that they develop an irreversible condition that prevents them from making their own medical decisions. The living will becomes effective if they become terminally ill, permanently unconscious, or minimally conscious due to brain damage and will never regain the ability to make decisions. People who want to indicate under what set of circumstances they favor or object to receiving any specific treatments use a living will.

The Patient Self-Determination Act of 1990 states that on admission to a hospital or nursing home, patients have to be informed of their rights, including the right to accept or refuse treatment.1 However, the current system of communicating wishes about end-of-life care using solely traditional advance directives such as the living will has proven insufficient. This is because traditional advance directives, being general statements of patients’ preferences, need to be carried out through specifications in medical orders when the need arises.2

Further, traditional advance directives require patients to recognize the importance of advance care planning, understand medical interventions, evaluate their own personal values and beliefs, and communicate their wishes to their agents, loved ones, physicians, and health care providers. Moreover, these documents apply to future circumstances, require further interpretation by the agent and health care professionals, and do not result in actionable medical orders. Decisions about care depend on interpreting earlier conversations, the physician’s estimates of prognosis, and, possibly, the personal convictions of the physician, agent, and loved ones, even though ethically, all involved need to focus on the patient’s stated wishes or best interest. A living will does not help clarify the patient’s wishes in the absence of antecedent conversation with the family, close friends, and the patient’s personal physician. And living wills cannot be read and interpreted in an emergency.

The situation is further complicated by difficulty in defining “terminal” or “irreversible” conditions and accounting for the different perspective that physicians, agents, and loved ones bring to the situation. For example, imagine a patient with dementia nearing the end of life who eats less, has difficulty managing secretions, aspirates, and develops pneumonia. While end-stage dementia is terminal, pneumonia may be reversible.

Increasingly, therefore, people are being counseled to appoint a health care agent (see below).3

The importance of a health care proxy (durable power of attorney for health care)

In a health care proxy document (also known as durable power of attorney for health care), the patient names a health care agent. This person has authority to make decisions about the patient’s medical care, including life-sustaining treatment. In other words, you the patient appoint someone to speak for you in the event you are unable to make your own medical decisions (not only at the end of life).

Since anyone may face a sudden and unexpected acute illness or injury with the risk of becoming incapacitated and unable to make medical decisions, everyone age 18 and older should be encouraged to complete a health care proxy document and to engage in advance care planning discussions with family and loved ones. Physicians can initiate this process as a wellness initiative and can help patients and families understand advance care planning. In all health care settings, trained and qualified health care professionals can provide education on advance care planning to patients, families, and loved ones.

A key issue when naming a health care agent is choosing the right one, someone who will make decisions in accordance with the person’s current values and beliefs and who can separate his or her personal values from the patient’s values. Another key issue: people need to have proactive discussions about their personal values, beliefs, and goals of care, which many are reluctant to do, and the health care agent must be willing to talk about sensitive issues ahead of time. Even when a health care agent is available in an emergency, emergency medical services personnel cannot follow directions from a health care agent. Most importantly, a health care agent must be able to handle potential conflicts between family and providers.

POLST ENSURES PATIENT PREFERENCES ARE HONORED AT THE END OF LIFE

Approximately 20 years ago, a team of health care professionals at the University of Oregon recognized these problems and realized that physicians needed to be more involved in discussions with patients about end-of-life care and in translating the patient’s preferences and values into concrete medical orders. The result was the Physician Orders for Life-Sustaining Treatment (POLST) Paradigm Program.4

What is POLST?

POLST is an end-of-life-care transitions program that focuses on patient-centered goals for care and shared informed medical decision-making.5,6 It offers a mechanism to communicate the wishes of seriously ill patients to have or to limit medical treatment as they move from one care setting to another. Table 1 lists the differences between traditional advance directives and POLST.

The aim is to improve the quality of care that seriously ill patients receive at the end of life. POLST is based on effective communication of the patient’s wishes, with actionable medical orders documented on a brightly colored form (www.ohsu.edu/polst/programs/sample-forms.htm; Figure 1) and a promise by health care professionals to honor these wishes.7 Key features of the program include education, training, and a quality-improvement process.

Who is POLST for?

POLST is for patients with serious life-limiting illness who have a life expectancy of less than 1 year, or anyone of advanced age interested in defining their end-of-life care wishes. Qualified and trained health care professionals (physicians, physician’s assistants, nurse practitioners, and social workers) participate in discussions leading to the completion of a POLST form in all settings, particularly along the long-term care continuum and for home hospice.

The key element of the POLST process: Shared, informed medical decision-making

Health care professionals working as an interdisciplinary team play a key role in educating patients and their families about advance care planning and shared, informed medical decision-making, as well as in resolving conflict. To be effective, shared medical decision-making must be well-informed. The decision-maker (patient, health care agent, or surrogate) must weigh the following questions (Table 2):

- Will treatment make a difference?

- Do the burdens of treatment outweigh its benefits?

- Is there hope of recovery? If so, what will life be like afterward?

- What does the patient value? What is the patient’s goal for his or her care?

In-depth discussions with patients, family members, and surrogates are needed, and these people are often reluctant to ask these questions and afraid to discuss the dying process. Even if they are informed of their diagnosis and prognosis, they may not know what they mean in terms of their everyday experience and future.

Health care professionals engaging in these conversations can use the eight-step POLST protocol (Table 3) to elicit their preferences at the end of life. Table 4 lists tools and resources to enhance the understanding of advance care planning and POLST.

What does the POLST form cover?

The POLST form (Figure 1) provides instructions about resuscitation if the patient has no pulse and is not breathing. Additionally, the medical orders indicate decisions about the level of medical intervention that the patient wants or does not want, eg, intubation, mechanical ventilation, transport to the hospital, intensive care, artificial nutrition and hydration, and antibiotics.

Thus, POLST is outcome-neutral and can be used either to limit medical interventions or to clarify a request for any or all medically indicated treatments.

Both the practitioner and the patient or patient’s surrogate sign the form. The original goes into the patient’s chart, and a copy should accompany the patient if he or she is transferred or discharged. Additionally, if the state has a POLST registry, the POLST information should be entered into the registry.

POLST is expanding across the country

The use of POLST has been expanding across the United States, with POLST programs now implemented in all or part of at least 30 states. There are endorsed programs in 14 states, and programs are being developed in 26 more. Requirements for endorsement are found at www.polst.org. Figure 2 shows the status of POLST in the 50 states.

Oregon’s POLST form is the original model for other forms designed to meet specific legislative or regulatory requirements in other states. POLST-like programs are known by different names in different states: eg, New York’s Medical Orders for Life-Sustaining Treatment (MOLST) and West Virginia’s Physicians Orders for Scope of Treatment (POST), but all endorsed programs share common core elements.

POLST research

A number of studies in the past 10 years have shown that POLST improves the documentation and honoring of patient preferences, whatever they may be.4,8–16

Emergency medical technicians in Oregon reported that the POLST form provides clear instructions about patient preferences and is useful when deciding which treatments to provide. In contrast to the single-intervention focus of out-of-hospital do-not-resuscitate orders, the POLST form provides patients the opportunity to document treatment goals and preferences for interventions across a range of treatment options, thus permitting greater individualization.13

Comfort care is not sacrificed if a POLST document is in place. Most hospice patients choose at least one life-sustaining treatment on their POLST form.14

In a multistate study published in 2010, the medical records of residents in 90 randomly chosen Medicaid-eligible nursing homes were reviewed.15 POLST was compared with traditional advance care planning in terms of the effect on the presence of medical orders reflecting treatment preferences, symptom management, and use of life-sustaining treatments. The study found that residents with POLST forms had significantly more medical orders about life-sustaining treatments than residents with traditional advance directives. There were no differences between residents with or without POLST forms on symptom assessment or management measures. POLST was more effective than traditional advance planning at limiting unwanted life-sustaining treatments. The study suggests that POLST offers significant advantages over traditional advance directives in nursing facilities.15,16

In summary, more than a decade of research has shown that the POLST Paradigm Program serves as an emerging national model for implementing shared, informed medical decision-making. Furthermore, POLST more accurately conveys end-of-life care preferences for patients with advanced chronic illness and for dying patients than traditional advance directives and yields higher adherence by medical professionals.

CLINICAL CASE REVISITED

Let’s consider if the physician for our 89-year-old woman with dementia had completed a POLST form with orders indicating “do not attempt resuscitation (DNR/no CPR)” and “comfort measures only, do not transfer to hospital for life-sustaining treatment and transfer if comfort needs cannot be met in current location.”

The patient’s respiratory distress and fever would have been treated at her nursing home with medication and oxygen. She would have been transferred to the hospital only if her comfort needs would not have been met at the nursing home. Unwanted life-sustaining treatment would have been avoided. The wishes of the patient, based on her values and careful consideration of options, would have been respected.

An 89-year-old woman with advanced dementia is living in a nursing home and is fully dependent in all aspects of personal care, including feeding. She has a health care proxy and a living will.

Her husband is her health care agent and has established that the primary goal of her care should be to keep her comfortable. He has repeatedly discussed this goal with her attending physician and the nursing-home staff and has reiterated that when his wife had capacity, she wanted “no heroics,” “no feeding tube,” and no life-sustaining treatment that would prolong her dying. He has requested that she not be transferred to the hospital and that she receive all further care at the nursing home. These preferences are consistent with her living will.

One evening, she becomes somnolent and febrile, with rapid breathing. The physician covering for the attending physician does not know the patient, cannot reach her husband, and sends her to the hospital, where she is admitted with aspiration pneumonia.

Her level of alertness improves with hydration. However, the hospital nurses have a difficult time feeding her. She does not seem to want to eat, “pockets” food in her cheeks, is slow to swallow, and sometimes coughs during feeding. This is nothing new—at the nursing home, her feeding pattern had been the same for nearly 6 months. During this time she always had a cough; fevers came and went. She has slowly lost weight; she now weighs 100 lb (45 kg), down 30 lb (14 kg) in 3 years.

With treatment, her respiratory distress and fever resolve. The physician orders a swallowing evaluation by a speech therapist, who determines that she needs a feeding tube. After that, a meeting is scheduled with her husband and physician to discuss the speech therapist’s assessment. The patient’s husband emphatically refuses the feeding tube and is upset that she was transferred to the hospital against his expressed wishes.

Why did this happen?

TRADITIONAL ADVANCE DIRECTIVES ARE OFTEN NOT ENOUGH

Even when patients fill out advance directives in accordance with state law, their preferences for care at the end of life are not consistently followed.

Problems with living wills

Living wills state patients’ wishes about medical care in the event that they develop an irreversible condition that prevents them from making their own medical decisions. The living will becomes effective if they become terminally ill, permanently unconscious, or minimally conscious due to brain damage and will never regain the ability to make decisions. People who want to indicate under what set of circumstances they favor or object to receiving any specific treatments use a living will.

The Patient Self-Determination Act of 1990 states that on admission to a hospital or nursing home, patients have to be informed of their rights, including the right to accept or refuse treatment.1 However, the current system of communicating wishes about end-of-life care using solely traditional advance directives such as the living will has proven insufficient. This is because traditional advance directives, being general statements of patients’ preferences, need to be carried out through specifications in medical orders when the need arises.2

Further, traditional advance directives require patients to recognize the importance of advance care planning, understand medical interventions, evaluate their own personal values and beliefs, and communicate their wishes to their agents, loved ones, physicians, and health care providers. Moreover, these documents apply to future circumstances, require further interpretation by the agent and health care professionals, and do not result in actionable medical orders. Decisions about care depend on interpreting earlier conversations, the physician’s estimates of prognosis, and, possibly, the personal convictions of the physician, agent, and loved ones, even though ethically, all involved need to focus on the patient’s stated wishes or best interest. A living will does not help clarify the patient’s wishes in the absence of antecedent conversation with the family, close friends, and the patient’s personal physician. And living wills cannot be read and interpreted in an emergency.

The situation is further complicated by difficulty in defining “terminal” or “irreversible” conditions and accounting for the different perspective that physicians, agents, and loved ones bring to the situation. For example, imagine a patient with dementia nearing the end of life who eats less, has difficulty managing secretions, aspirates, and develops pneumonia. While end-stage dementia is terminal, pneumonia may be reversible.

Increasingly, therefore, people are being counseled to appoint a health care agent (see below).3

The importance of a health care proxy (durable power of attorney for health care)

In a health care proxy document (also known as durable power of attorney for health care), the patient names a health care agent. This person has authority to make decisions about the patient’s medical care, including life-sustaining treatment. In other words, you the patient appoint someone to speak for you in the event you are unable to make your own medical decisions (not only at the end of life).

Since anyone may face a sudden and unexpected acute illness or injury with the risk of becoming incapacitated and unable to make medical decisions, everyone age 18 and older should be encouraged to complete a health care proxy document and to engage in advance care planning discussions with family and loved ones. Physicians can initiate this process as a wellness initiative and can help patients and families understand advance care planning. In all health care settings, trained and qualified health care professionals can provide education on advance care planning to patients, families, and loved ones.

A key issue when naming a health care agent is choosing the right one, someone who will make decisions in accordance with the person’s current values and beliefs and who can separate his or her personal values from the patient’s values. Another key issue: people need to have proactive discussions about their personal values, beliefs, and goals of care, which many are reluctant to do, and the health care agent must be willing to talk about sensitive issues ahead of time. Even when a health care agent is available in an emergency, emergency medical services personnel cannot follow directions from a health care agent. Most importantly, a health care agent must be able to handle potential conflicts between family and providers.

POLST ENSURES PATIENT PREFERENCES ARE HONORED AT THE END OF LIFE

Approximately 20 years ago, a team of health care professionals at the University of Oregon recognized these problems and realized that physicians needed to be more involved in discussions with patients about end-of-life care and in translating the patient’s preferences and values into concrete medical orders. The result was the Physician Orders for Life-Sustaining Treatment (POLST) Paradigm Program.4

What is POLST?

POLST is an end-of-life-care transitions program that focuses on patient-centered goals for care and shared informed medical decision-making.5,6 It offers a mechanism to communicate the wishes of seriously ill patients to have or to limit medical treatment as they move from one care setting to another. Table 1 lists the differences between traditional advance directives and POLST.

The aim is to improve the quality of care that seriously ill patients receive at the end of life. POLST is based on effective communication of the patient’s wishes, with actionable medical orders documented on a brightly colored form (www.ohsu.edu/polst/programs/sample-forms.htm; Figure 1) and a promise by health care professionals to honor these wishes.7 Key features of the program include education, training, and a quality-improvement process.

Who is POLST for?

POLST is for patients with serious life-limiting illness who have a life expectancy of less than 1 year, or anyone of advanced age interested in defining their end-of-life care wishes. Qualified and trained health care professionals (physicians, physician’s assistants, nurse practitioners, and social workers) participate in discussions leading to the completion of a POLST form in all settings, particularly along the long-term care continuum and for home hospice.

The key element of the POLST process: Shared, informed medical decision-making

Health care professionals working as an interdisciplinary team play a key role in educating patients and their families about advance care planning and shared, informed medical decision-making, as well as in resolving conflict. To be effective, shared medical decision-making must be well-informed. The decision-maker (patient, health care agent, or surrogate) must weigh the following questions (Table 2):

- Will treatment make a difference?

- Do the burdens of treatment outweigh its benefits?

- Is there hope of recovery? If so, what will life be like afterward?

- What does the patient value? What is the patient’s goal for his or her care?

In-depth discussions with patients, family members, and surrogates are needed, and these people are often reluctant to ask these questions and afraid to discuss the dying process. Even if they are informed of their diagnosis and prognosis, they may not know what they mean in terms of their everyday experience and future.

Health care professionals engaging in these conversations can use the eight-step POLST protocol (Table 3) to elicit their preferences at the end of life. Table 4 lists tools and resources to enhance the understanding of advance care planning and POLST.

What does the POLST form cover?

The POLST form (Figure 1) provides instructions about resuscitation if the patient has no pulse and is not breathing. Additionally, the medical orders indicate decisions about the level of medical intervention that the patient wants or does not want, eg, intubation, mechanical ventilation, transport to the hospital, intensive care, artificial nutrition and hydration, and antibiotics.

Thus, POLST is outcome-neutral and can be used either to limit medical interventions or to clarify a request for any or all medically indicated treatments.

Both the practitioner and the patient or patient’s surrogate sign the form. The original goes into the patient’s chart, and a copy should accompany the patient if he or she is transferred or discharged. Additionally, if the state has a POLST registry, the POLST information should be entered into the registry.

POLST is expanding across the country

The use of POLST has been expanding across the United States, with POLST programs now implemented in all or part of at least 30 states. There are endorsed programs in 14 states, and programs are being developed in 26 more. Requirements for endorsement are found at www.polst.org. Figure 2 shows the status of POLST in the 50 states.

Oregon’s POLST form is the original model for other forms designed to meet specific legislative or regulatory requirements in other states. POLST-like programs are known by different names in different states: eg, New York’s Medical Orders for Life-Sustaining Treatment (MOLST) and West Virginia’s Physicians Orders for Scope of Treatment (POST), but all endorsed programs share common core elements.

POLST research

A number of studies in the past 10 years have shown that POLST improves the documentation and honoring of patient preferences, whatever they may be.4,8–16

Emergency medical technicians in Oregon reported that the POLST form provides clear instructions about patient preferences and is useful when deciding which treatments to provide. In contrast to the single-intervention focus of out-of-hospital do-not-resuscitate orders, the POLST form provides patients the opportunity to document treatment goals and preferences for interventions across a range of treatment options, thus permitting greater individualization.13

Comfort care is not sacrificed if a POLST document is in place. Most hospice patients choose at least one life-sustaining treatment on their POLST form.14

In a multistate study published in 2010, the medical records of residents in 90 randomly chosen Medicaid-eligible nursing homes were reviewed.15 POLST was compared with traditional advance care planning in terms of the effect on the presence of medical orders reflecting treatment preferences, symptom management, and use of life-sustaining treatments. The study found that residents with POLST forms had significantly more medical orders about life-sustaining treatments than residents with traditional advance directives. There were no differences between residents with or without POLST forms on symptom assessment or management measures. POLST was more effective than traditional advance planning at limiting unwanted life-sustaining treatments. The study suggests that POLST offers significant advantages over traditional advance directives in nursing facilities.15,16

In summary, more than a decade of research has shown that the POLST Paradigm Program serves as an emerging national model for implementing shared, informed medical decision-making. Furthermore, POLST more accurately conveys end-of-life care preferences for patients with advanced chronic illness and for dying patients than traditional advance directives and yields higher adherence by medical professionals.

CLINICAL CASE REVISITED

Let’s consider if the physician for our 89-year-old woman with dementia had completed a POLST form with orders indicating “do not attempt resuscitation (DNR/no CPR)” and “comfort measures only, do not transfer to hospital for life-sustaining treatment and transfer if comfort needs cannot be met in current location.”

The patient’s respiratory distress and fever would have been treated at her nursing home with medication and oxygen. She would have been transferred to the hospital only if her comfort needs would not have been met at the nursing home. Unwanted life-sustaining treatment would have been avoided. The wishes of the patient, based on her values and careful consideration of options, would have been respected.

- Dunn PM, Tolle SW, Moss AH, Black JS. The POLST paradigm: respecting the wishes of patients and families. Ann Long-Term Care 2007; 15:33–40.

- Patient Self-Determination Act of 1990. Pub. L. No. 101-508, ss 4206, 104 Stat. 1388.

- Bomba PA, Sabatino CP. POLST: an emerging model for end-of-life care planning. The ElderLaw Report 2009; 20:1–5.

- Karp Sabatino C. AARP Public Policy Institute, Improving advance illness care: the evolution of state POLST programs 2011. http://assets.aarp.org/rgcenter/ppi/cons-prot/POLST-Report-04-11.pdf. Accessed May 30, 2012.

- Bomba PA. Discussing patient p and end of life care, Journal of the Monroe County Medical Society, 7th District Branch, MSSNY 2011;12–15. www.compassionandsupport.org/index.php/research_/. Accessed May 30, 2012.

- Citko J, Moss AH, Carley M, Tolle SW. The National POLST Paradigm Initiative, 2ND ed. Fast Facts and Concepts 2010;178. www.eperc.mcw.edu/fastfact/ff_178.htm. Accessed May 30, 2012.

- Center for Ethics in Health Care, Oregon Health & Science University. www.ohsu.edu/polst/. Accessed May 30, 2012.

- Lee MA, Brummel-Smith K, Meyer J, Drew N, London MR. Physician orders for life-sustaining treatment (POLST): outcomes in a PACE program. Program of All-Inclusive Care for the Elderly. J Am Geriatr Soc 2000; 48:1219–1225.

- Meyers JL, Moore C, McGrory A, Sparr J, Ahern M. Physician orders for life-sustaining treatment form: honoring end-of-life directives for nursing home residents. J Gerontol Nurs 2004; 30:37–46.

- Dunn PM, Schmidt TA, Carley MM, Donius M, Weinstein MA, Dull VT. A method to communicate patient p about medically indicated life-sustaining treatment in the out-of-hospital setting. J Am Geriatr Soc 1996; 44:785–791.

- Cantor MD. Improving advance care planning: lessons from POLST. Physician Orders for Life-Sustaining Treatment (comment). J Am Geriatr Soc 2000; 48:1343–1344.

- Tolle SW, Tilden VP, Nelson CA, Dunn PM. A prospective study of the efficacy of the physician order form for life-sustaining treatment. J Am Geriatr Soc 1998; 46:1097–1102.

- Schmidt TA, Hickman SE, Tolle SW, Brooks HS. The Physician Orders for Life-Sustaining Treatment program: Oregon emergency medical technicians’ practical experiences and attitudes. J Am Geriatr Soc 2004; 52:1430–1434.

- Hickman SE, Nelson CA, Moss AH, et al. Use of the Physician Orders for Life-Sustaining Treatment (POLST) paradigm program in the hospice setting. J Palliat Med 2009; 12:133–141.

- Hickman SE, Nelson CA, Perrin NA, Moss AH, Hammes BJ, Tolle SW. A comparison of methods to communicate treatment p in nursing facilities: traditional practices versus the physician orders for life-sustaining treatment program. J Am Geriatr Soc 2010; 58:1241–1248.

- Hickman SE, Nelson CA, Moss AH, Tolle SW, Perrin NA, Hammes BJ. The consistency between treatments provided to nursing facility residents and orders on the physician orders for life-sustaining treatment form. J Am Geriatr Soc 2011; 59:2091–2099.

- Dunn PM, Tolle SW, Moss AH, Black JS. The POLST paradigm: respecting the wishes of patients and families. Ann Long-Term Care 2007; 15:33–40.

- Patient Self-Determination Act of 1990. Pub. L. No. 101-508, ss 4206, 104 Stat. 1388.

- Bomba PA, Sabatino CP. POLST: an emerging model for end-of-life care planning. The ElderLaw Report 2009; 20:1–5.

- Karp Sabatino C. AARP Public Policy Institute, Improving advance illness care: the evolution of state POLST programs 2011. http://assets.aarp.org/rgcenter/ppi/cons-prot/POLST-Report-04-11.pdf. Accessed May 30, 2012.

- Bomba PA. Discussing patient p and end of life care, Journal of the Monroe County Medical Society, 7th District Branch, MSSNY 2011;12–15. www.compassionandsupport.org/index.php/research_/. Accessed May 30, 2012.

- Citko J, Moss AH, Carley M, Tolle SW. The National POLST Paradigm Initiative, 2ND ed. Fast Facts and Concepts 2010;178. www.eperc.mcw.edu/fastfact/ff_178.htm. Accessed May 30, 2012.

- Center for Ethics in Health Care, Oregon Health & Science University. www.ohsu.edu/polst/. Accessed May 30, 2012.

- Lee MA, Brummel-Smith K, Meyer J, Drew N, London MR. Physician orders for life-sustaining treatment (POLST): outcomes in a PACE program. Program of All-Inclusive Care for the Elderly. J Am Geriatr Soc 2000; 48:1219–1225.

- Meyers JL, Moore C, McGrory A, Sparr J, Ahern M. Physician orders for life-sustaining treatment form: honoring end-of-life directives for nursing home residents. J Gerontol Nurs 2004; 30:37–46.

- Dunn PM, Schmidt TA, Carley MM, Donius M, Weinstein MA, Dull VT. A method to communicate patient p about medically indicated life-sustaining treatment in the out-of-hospital setting. J Am Geriatr Soc 1996; 44:785–791.

- Cantor MD. Improving advance care planning: lessons from POLST. Physician Orders for Life-Sustaining Treatment (comment). J Am Geriatr Soc 2000; 48:1343–1344.

- Tolle SW, Tilden VP, Nelson CA, Dunn PM. A prospective study of the efficacy of the physician order form for life-sustaining treatment. J Am Geriatr Soc 1998; 46:1097–1102.

- Schmidt TA, Hickman SE, Tolle SW, Brooks HS. The Physician Orders for Life-Sustaining Treatment program: Oregon emergency medical technicians’ practical experiences and attitudes. J Am Geriatr Soc 2004; 52:1430–1434.

- Hickman SE, Nelson CA, Moss AH, et al. Use of the Physician Orders for Life-Sustaining Treatment (POLST) paradigm program in the hospice setting. J Palliat Med 2009; 12:133–141.

- Hickman SE, Nelson CA, Perrin NA, Moss AH, Hammes BJ, Tolle SW. A comparison of methods to communicate treatment p in nursing facilities: traditional practices versus the physician orders for life-sustaining treatment program. J Am Geriatr Soc 2010; 58:1241–1248.

- Hickman SE, Nelson CA, Moss AH, Tolle SW, Perrin NA, Hammes BJ. The consistency between treatments provided to nursing facility residents and orders on the physician orders for life-sustaining treatment form. J Am Geriatr Soc 2011; 59:2091–2099.

KEY POINTS

- Failures and opportunities for improvement in current advance care planning processes highlight the need for change.

- Differences exist between traditional advance directives and actionable medical orders.

- Advance care planning discussions can be initiated by physicians as a wellness initiative for everyone 18 years of age and older and can help patients and families understand advance care planning.

- POLST is outcome-neutral and may be used either to limit medical interventions or to clarify a request for any or all medically indicated treatments.

- Shared, informed medical decision-making is an essential element of the POLST process.