User login

Proactive Penicillin Allergy Delabeling: Lessons Learned From a Quality Improvement Project

Proactive Penicillin Allergy Delabeling: Lessons Learned From a Quality Improvement Project

Penicillin allergy is common in the United States. About 9.0% to 13.8% of patients have a diagnosed penicillin allergy documented in their electronic health record. The annual incidence rates is 1.1% in males and 1.4% in females.1,2

Penicillin hypersensitivity likely wanes over time. A 1981 study found that 93% of patients who experienced an allergic reaction to penicillin had a positive skin test 7 to 12 months postreaction, but only 22% still had a positive test after 10 years.3 Confirmed type 1 hypersensitivity penicillin allergies, as demonstrated by positive skin prick testing, also are decreasing over time.4 Furthermore, many patients’ reactions may have been misdiagnosed as a penicillin allergy. Upon actual confirmatory testing of penicillin allergy, only 8.5% to 13.8% of patients believed to have a penicillin allergy were positive on skin prick testing of penicillin products.5,6 A 2024 US study found that 11% of individuals with a history of a penicillin reaction tested positive on skin testing.7

The positive predictive value of penicillin allergy skin testing is poorly defined due to the ethical dilemma of orally challenging a patient who demonstrates skin test reactivity. Due to its high negative predictive value (NPV), skin prick combined with intradermal testing has been the gold-standard test in cases of clinical concern.6 Patients with positive skin testing are assumed to be truly positive, and therefore penicillin allergic, even though false-positive results to penicillin skin testing are known to occur.8

Misdiagnosis of penicillin allergy carries substantial clinical and economic consequences. A 2011 study suggested a statistically significant 1.8% increased absolute risk of mortality and 5.5% increased absolute risk of intensive care unit admission for those labeled with penicillin allergy and admitted for an infection.9 Another study found a 14% increase in mortality associated with the diagnosis of penicillin allergy.10 In a 2014 case-control study, penicillin allergy also was associated with a 23.4% greater risk of Clostridioides difficile, 14.1% more methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus, and 30.1% more vancomycin-resistant enterococci infections.11Direct cost savings during an inpatient admission for infection were as much as $609 per patient with additional indirect cost savings of up to $4254 per admission.12 When viewed from the perspective of a health care system, these costs quickly accumulate, negatively impacting the fiscal stability of our patients and placing additional financial strain on an over-burdened system.

If 10% of US patients have penicillin allergy labels, then about 33 million patients might be eligible for delabeling. There are only 6309 board-certified allergists actively practicing in the US, which could amount to about 5231 potential penicillin challenges per allergist, not even including the 3.3 million new patients per year (assuming a 1% incidence).13 Clarifying each patient’s tolerance of penicillin products will clearly require nonallergist cooperation.

The 2022 drug allergy practice parameter update recommends several consensus-based statements (CBSs) to directly address penicillin allergy.14 This guideline recommends proactive efforts to delabel patients with a reported penicillin allergy (CBS 4); advise against testing in cases where the history is inconsistent with a true allergic reaction, though a challenge may be offered (CBS 5); skin testing for those with a history of anaphylaxis or a recent reaction (CBS 6); advise against multiple-day penicillin challenges (CBS 7); advise against skin testing for pediatric patients with benign cutaneous reactions (CBS 8); and recommends direct oral challenge for adults with distant or benign cutaneous reactions (CBS 9). These recommendations create a potentially high demand for delabeling with allergy specialists. One potential solution is to perform direct oral challenges in primary care, emergency departments, and urgent care clinics.

Evidence supporting the safety of direct oral penicillin challenges in low-risk patients was initially noted in the allergy community, but now evidence for their use in primary care clinics is growing—including in children.15 In a military-specific population, an amoxicillin challenge of Marine recruits with suspected penicillin allergy revealed that only 1.5% of those challenged acutely reacted and should be considered allergic to penicillin.16 Historically, in order to refute the diagnosis of penicillin allergy, an allergist would order penicillin skin prick testing. If the test was negative, an allergist would proceed to intradermal testing and if negative again (NPV of 97.9%), proceed to a graded oral challenge.6 However, this process is not fully reproducible in most clinics because the minor determinants mixture used in skin testing is not commercially available.17 Additionally, the full skin testing procedure requires specialized training, is more time-consuming, causes more discomfort, lacks US Food and Drug Administration approval for children, and has a higher cost ($220 per test for each patient as of 2016).18 As such, the movement toward direct oral challenges is progressing. Nonetheless, the best method for primary care or emergency department clinicians to determine who the appropriate patients are for this procedure has not been fully established. Risk tools have been created in the past to help delineate low-risk patients who would be appropriate for direct oral amoxicillin challenges, but these were not widely replicated or validated.19 The PEN-FAST standardized risk score was first published in 2020 and has since been validated in different groups with additional safety data. This scoring system ranges from 0 to 5 points, assigning 2 points for a penicillin reaction within the past five (F) years, 2 points for angioedema/anaphylaxis (A) or a severe (S) cutaneous reaction, and 1 point if treatment (T) was required for the reaction. A score < 3 is considered low-risk and safe for direct oral challenge, although most of the safety data are in patients with a score of 0 or 1.20 The PEN-FAST guided direct oral challenge with an NPV of 96.3% has now been prospectively shown to be noninferior to standard skin prick test/intradermal test/graded challenge for low-risk patients with a PEN-FAST score < 3.21 The PEN-FAST validating study was conducted predominantly with an Australian population of adult White women, but now it also has been validated in children aged > 12 years, as well as in European and North American cohorts.22-24

Air Force Delabeling Program

This article describes a method for proactively, safely, and efficiently delabeling penicillin allergic patients at an Air Force clinic. This quality improvement (QI) report provides a successful model for penicillin allergy delabeling, illustrates lessons learned, and suggests next steps toward improving patient options for an invaluable antibiotic class.

The first step was to proactively delabel penicillin allergy from a population of active duty service members and their dependents. Electronic health record (EHR) allergy search functions are a helpful tool in finding patients with allergy labels. The Kadena Medical Clinic, in Okinawa, Japan, uses the Military Health System GENESIS EHR, which includes a discern reporting portal with a patient allergy search that creates a patient-specific medication allergy report. To compile the most complete database of patients with a penicillin allergy, all 15 potential allergy search options for “penicillin” were selected, as were 4 relevant options for amoxicillin (including options with clavulanate). Including so many options for specific penicillin medication allergies helps add specificity to the diagnosis in the EHR but can make aggregation of data more difficult. The

The complete compiled list was manually reviewed for high-risk patients with severe cutaneous adverse reactions (SCARs) of any age. Patients with pregnancy, unsuitable medical histories (ie, severe asthma), or taking β-blockers were excluded. Patients remaining on the list were contacted by telephone and offered appointments during a single week that was dedicated to penicillin allergy delabeling. Allergists in the Air Force are assigned to a region where they offer allergy services at clinics without a regular allergist. The allergist for the region traveled to the QI site for a 1-week campaign at an estimated cost of $4600. When the patients were contacted, they were briefly informed of the goal of the penicillin delabeling campaign, and if interested, they were scheduled for 1 of 50 available appointments that week. Patients were contacted with enough lead time to stop oral antihistamines (OAH) for ≥ 7 days before the appointment.

Patients were given an intake questionnaire and interviewed about their penicillin allergy history. This questionnaire inquired about the nature of the allergy, mental and physical health impacts of the allergy label, PEN-FAST scoring questions, and posttest attitude toward delabeling, if applicable. Patients with a PEN-FAST score < 3 were offered direct, graded oral challenge or the standard skin prick, followed by intradermal, followed by graded oral challenge protocol. Patients with PEN-FAST scores of ≥ 3 were offered skin testing prior to oral challenge protocol. Patients could decline further testing. If patients wished to proceed, they were asked to complete a written informed consent document.

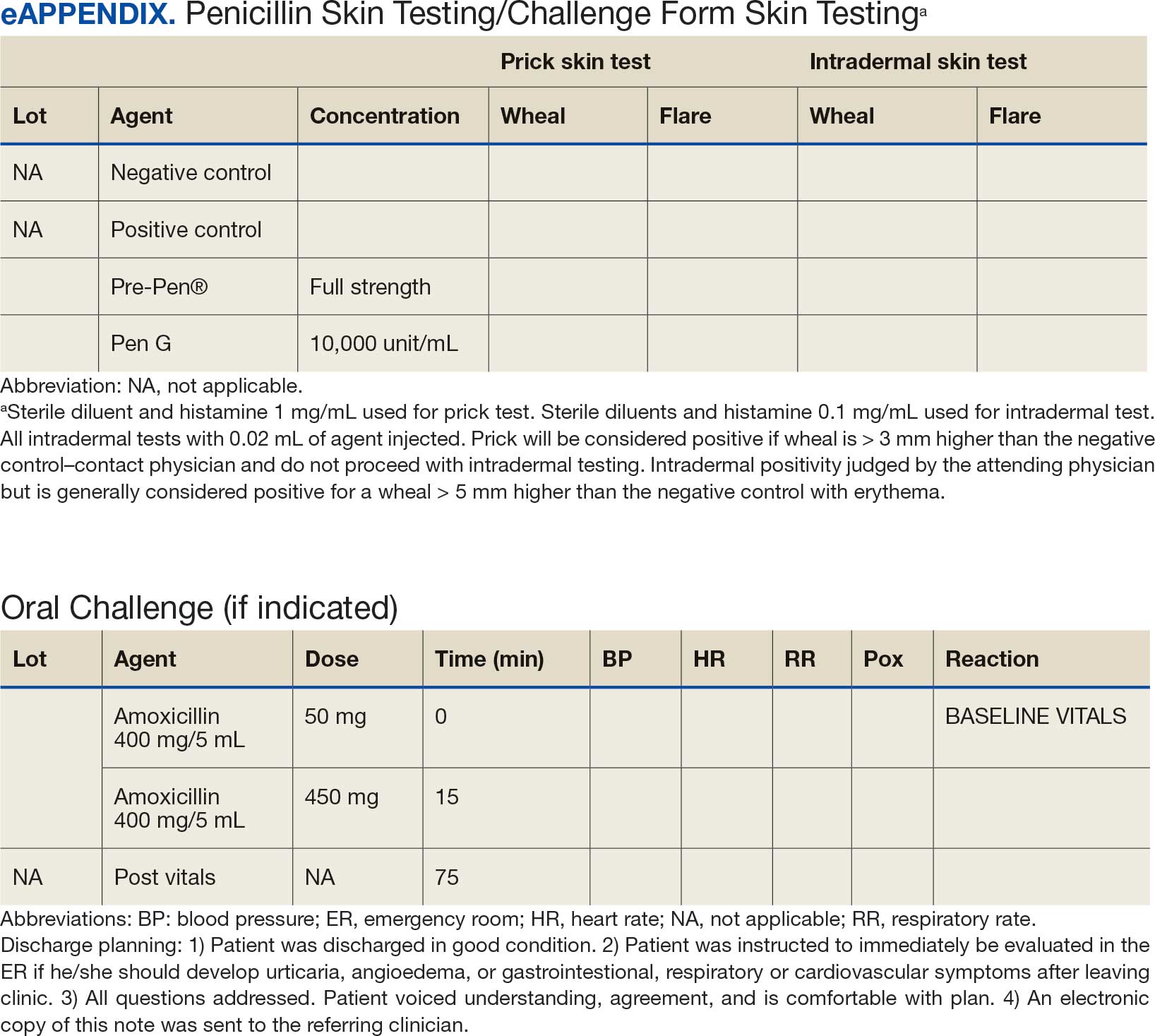

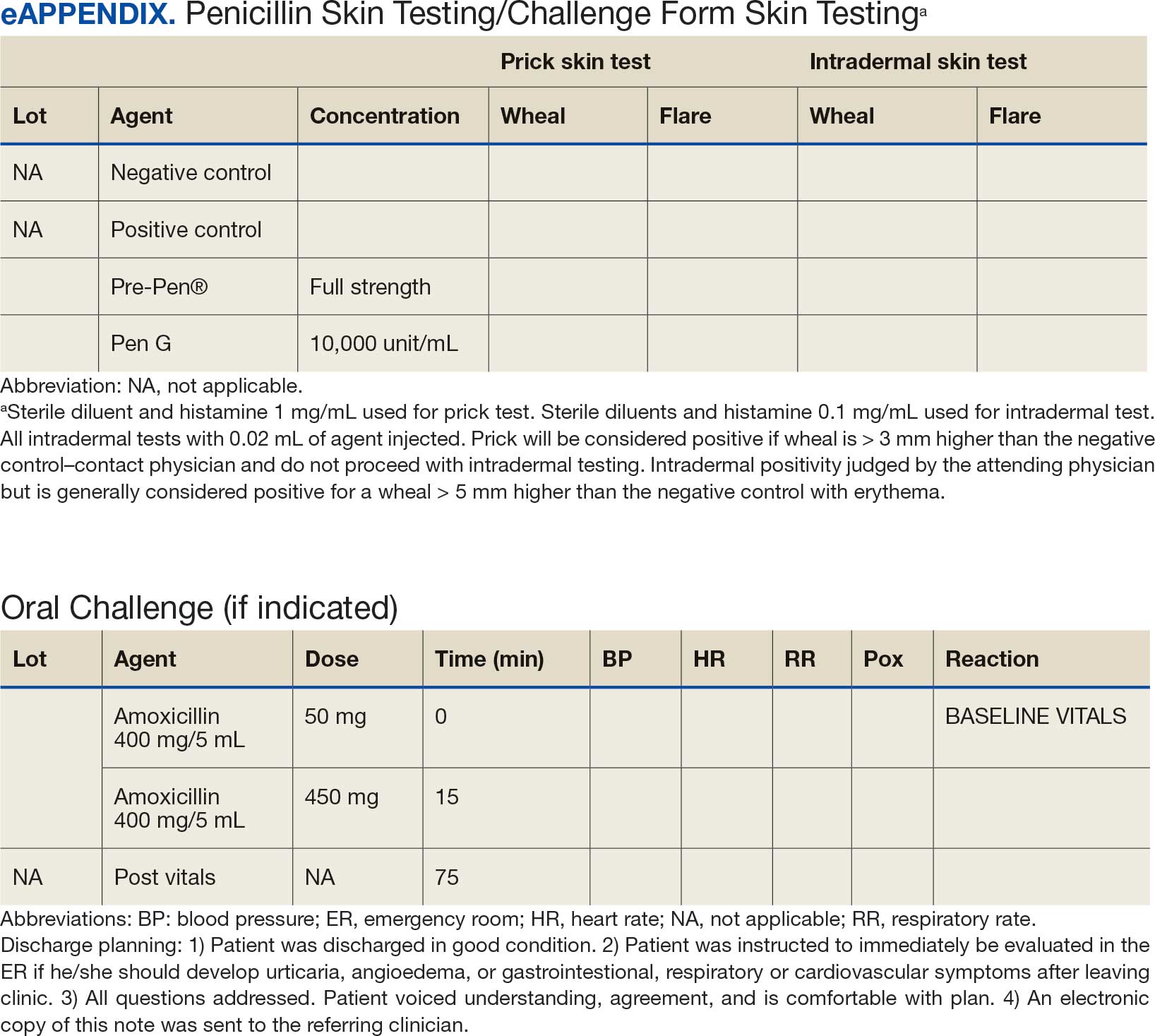

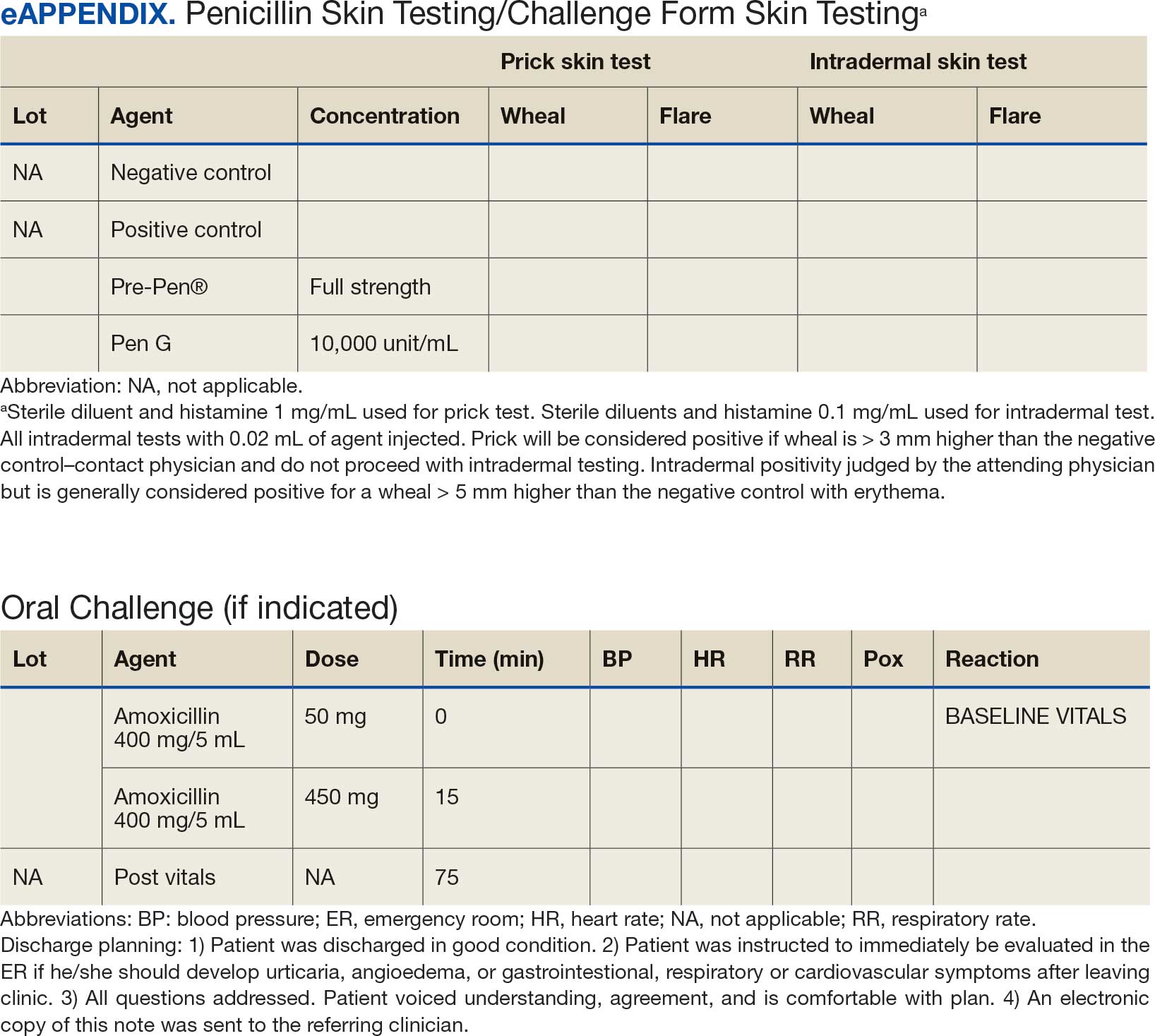

Oral challenges followed a 10%/90% protocol, beginning with 50 mg of liquid amoxicillin followed by 450 mg after 15 minutes, as long as the patient remained asymptomatic. Challenge forms are available in the eAppendix . After receiving the 450-mg amoxicillin dose, the patient remained in the clinic for 60 minutes before a final clinical evaluation. If the patient remained asymptomatic after this period, the penicillin or amoxicillin allergy was marked as resolved in the EHR. The patients were given contact information for the clinic for follow-up if a delayed reaction was noted and they wished the medication allergy to be re-entered. An EHR encounter note was created for each patient detailing the allergy testing and delabeling.

This campaign was conducted at a basic life support-only facility by a single clinician without medical technician support. An allergic reaction medication kit was available and contained OAHs, intramuscular antihistamines, intramuscular epinephrine, intramuscular corticosteroids, and short-acting β-agonists for nebulization. The facility also had an urgent care room (staffed by primary care practitioners [PCPs]) that could help establish intravenous access and administer fluids if necessary and had previously established plans for emergency patient transport to a higher level of care, if necessary.

Program Outcomes

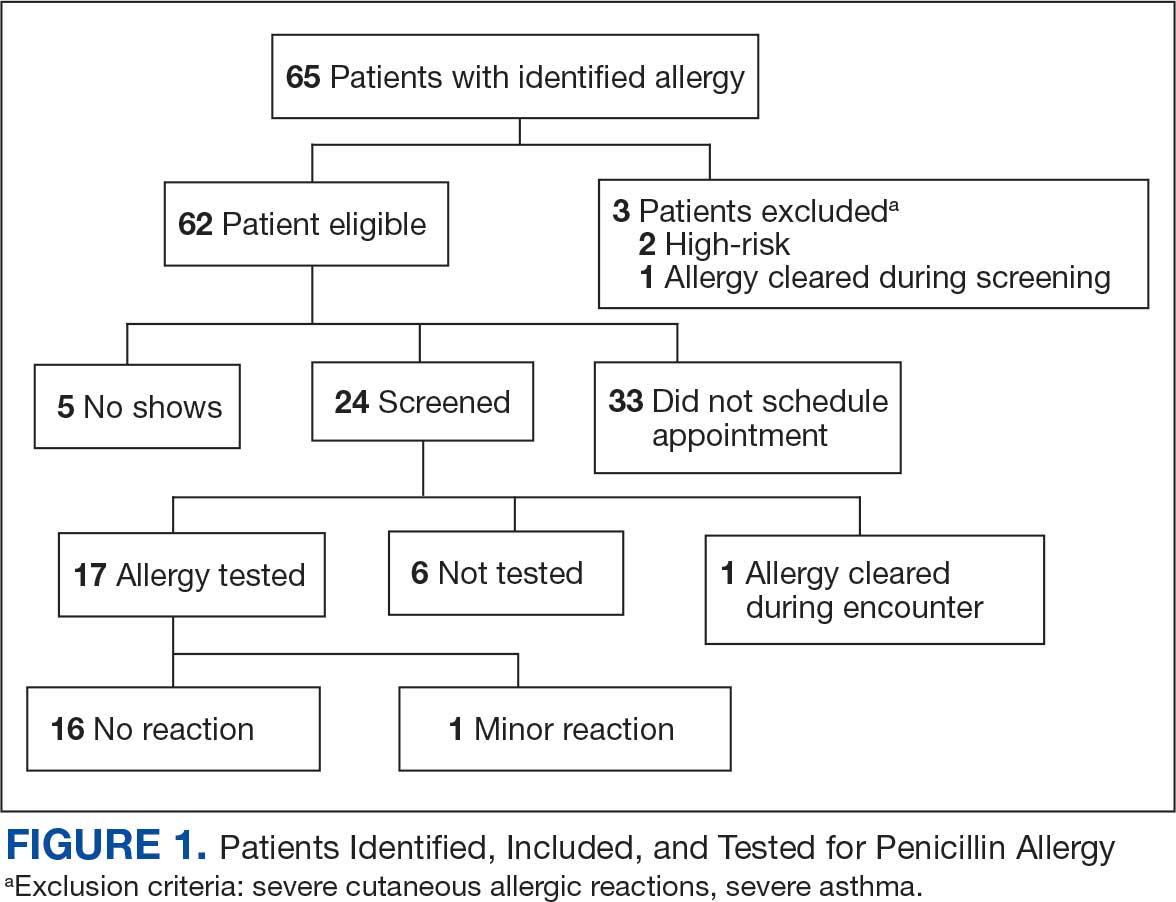

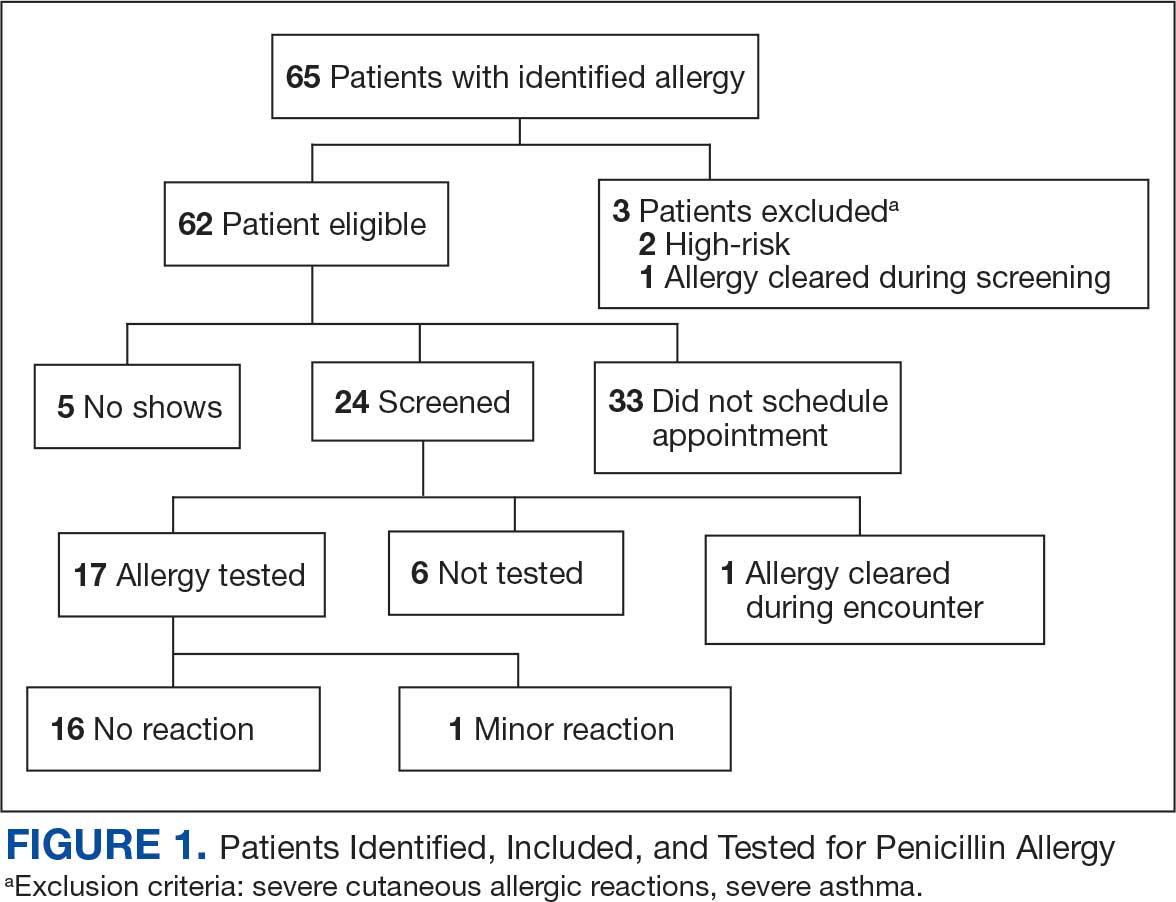

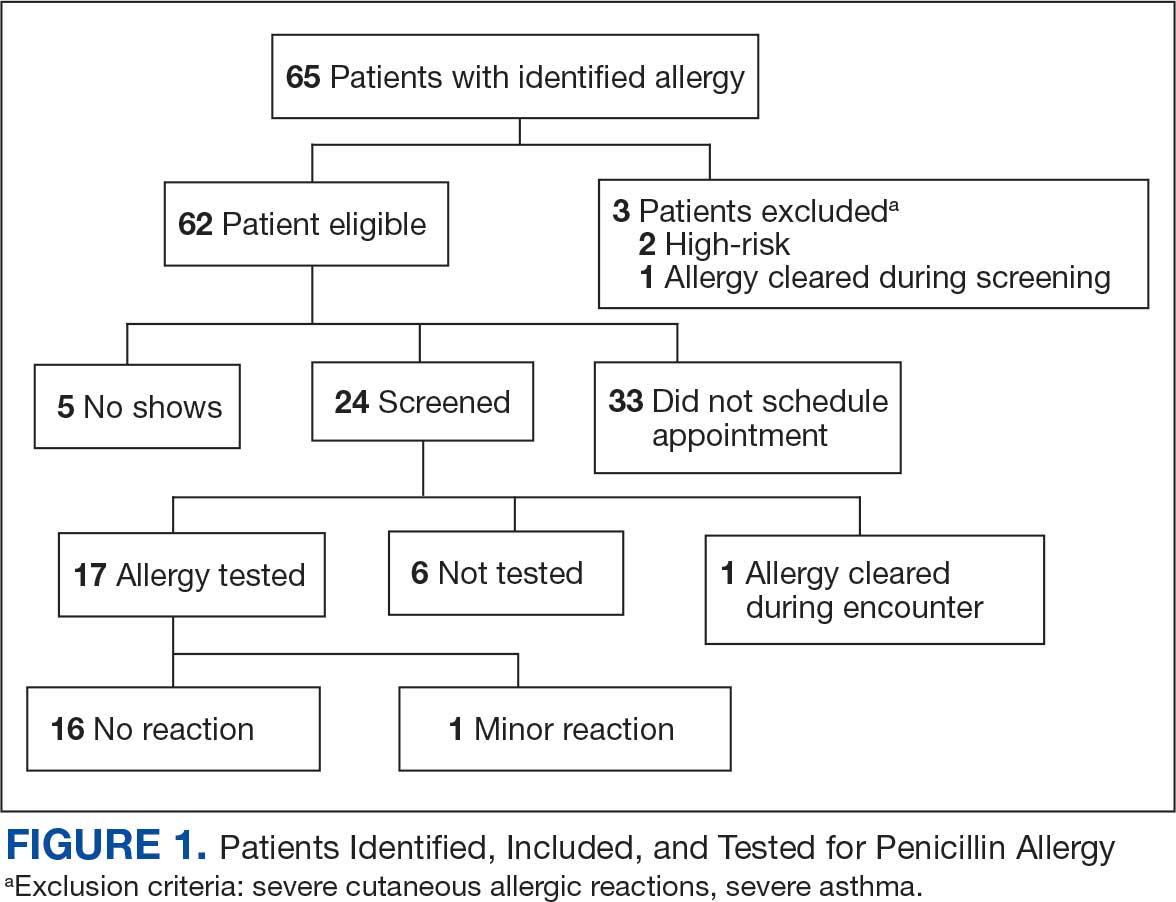

A list of 65 patients that included both active-duty service members and dependents with penicillin or amoxicillin allergy was created. This list was reviewed by an allergist to identify high-risk individuals, which required about 90 minutes. Two patients (3%) were excluded; 1 had a history of SCAR to penicillin and 1 had a complex medical history requiring continued OAH use. Sixty-three patients were contacted via telephone, and 29 patients (46%) scheduled an appointment. One patient (2%) was identified as penicillin-tolerant during the booking process, and the penicillin allergy was removed without testing (Figure 1).

Of the 29 scheduled patients, 5 patients (17%) failed to present for care. Of the potential appointments set aside for the program, only 42% were used. One patient (4%) who was seen in clinic was delabeled based on history alone as they had previously successfully tolerated a course of amoxicillin. Four patients (17%) declined further testing with a PEN-FAST score > 2 due to a clear history of acute immunoglobulin (Ig) E-mediated reaction to a penicillin product within the past year. One patient (4%) was unable to be tested due to ongoing OAH use and 1 patient (4%) declined further penicillin testing after the discussion about risks, benefits, and alternatives to the procedures offered.

Of the 24 patients who arrived for a clinic appointment, 17 (71%) underwent penicillin allergy delabeling testing: 14 (82%) underwent direct challenge, and 3 (18%) underwent the skin testing before oral amoxicillin challenge procedure. Of the 17 who were tested, 16 (94%) tolerated a total dose of 500 mg of oral amoxicillin within the 1-hour observation period. One tested patient (6%) in the direct oral challenge group experienced an adverse reaction that was described as dull headache and hand tremor after the 50-mg dose; although it self-resolved within 15 minutes, this prompted the patient to discontinue the challenge. This adverse reaction was determined to be very unlikely IgE-mediated. None of the 3 patients who underwent the skin testing before oral challenge protocol experienced an adverse drug reaction (ADR). None of the 17 patients who received any oral amoxicillin required follow-up or reported a delayed cutaneous ADR to the challenge. No OAHs or epinephrine were used for any of the challenges.

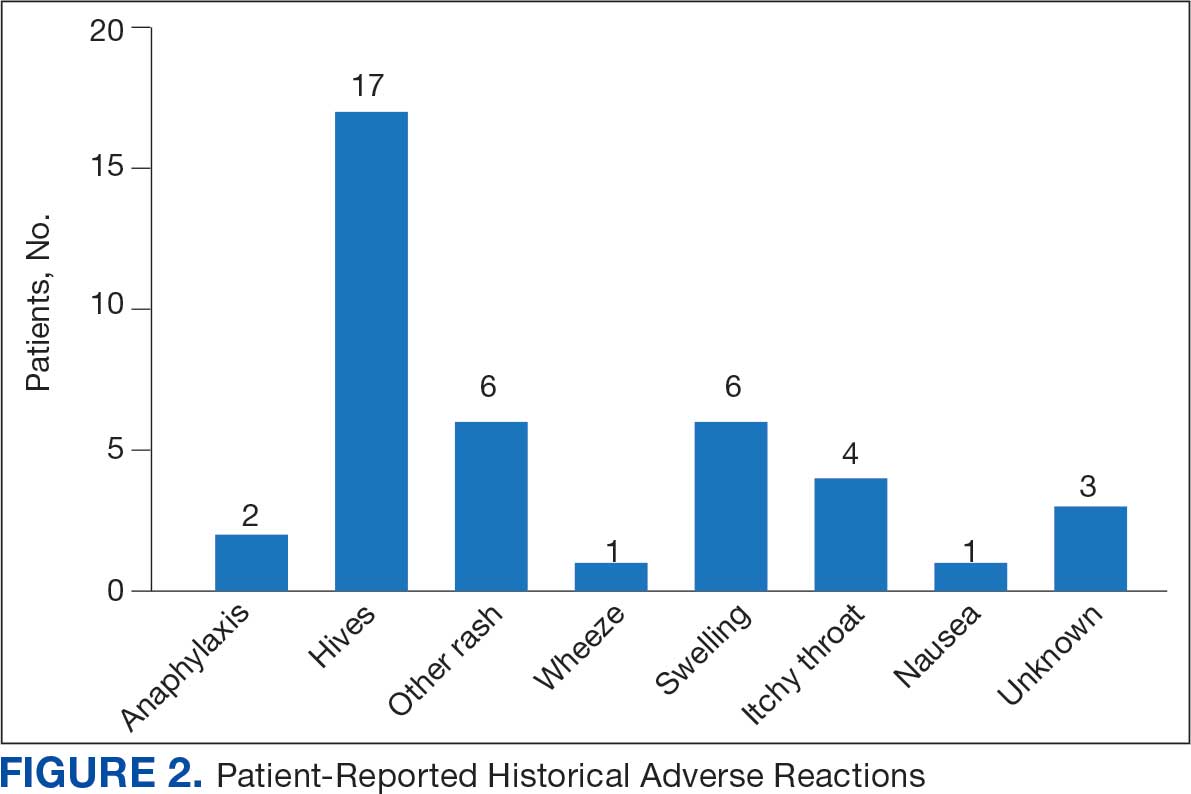

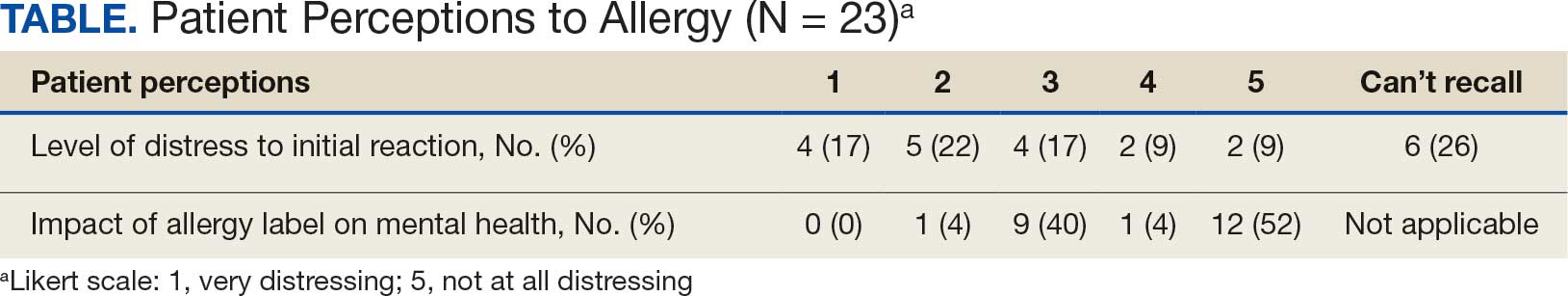

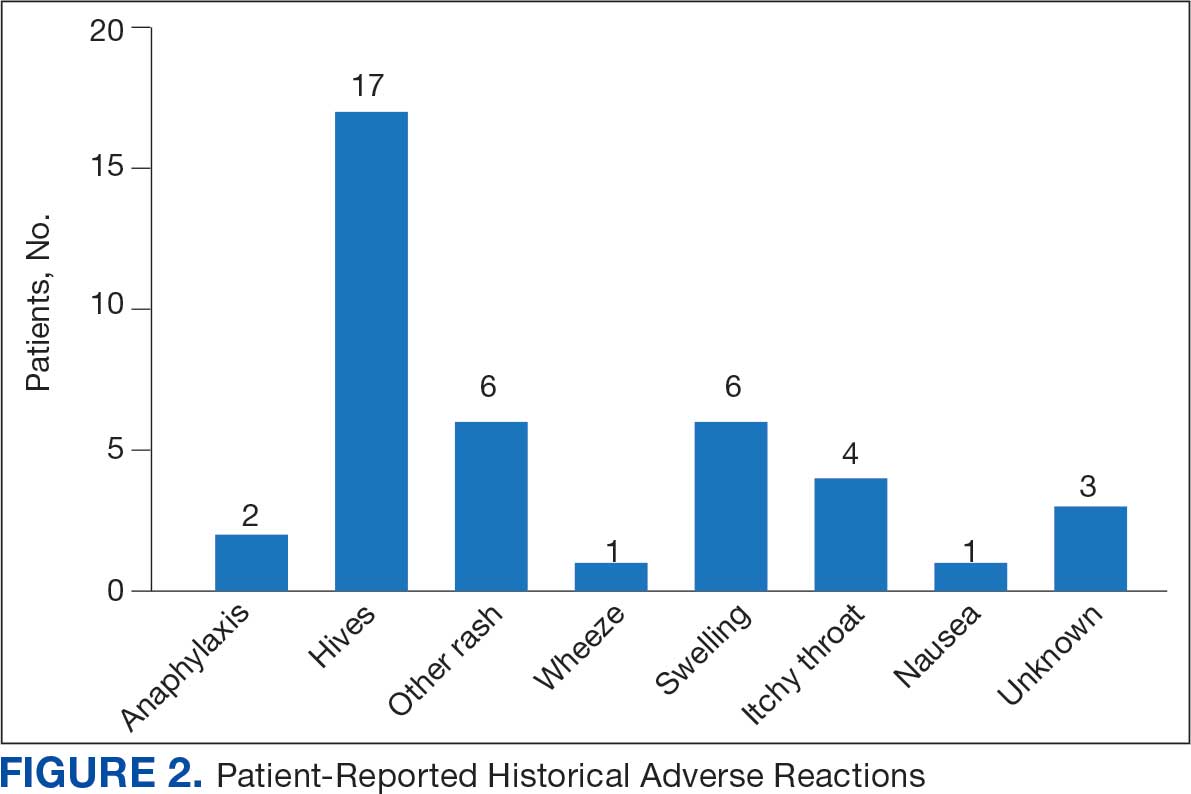

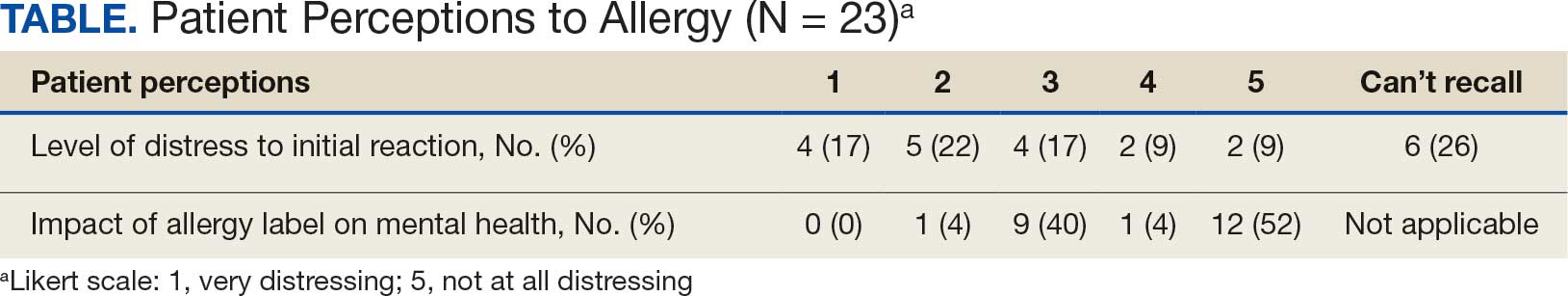

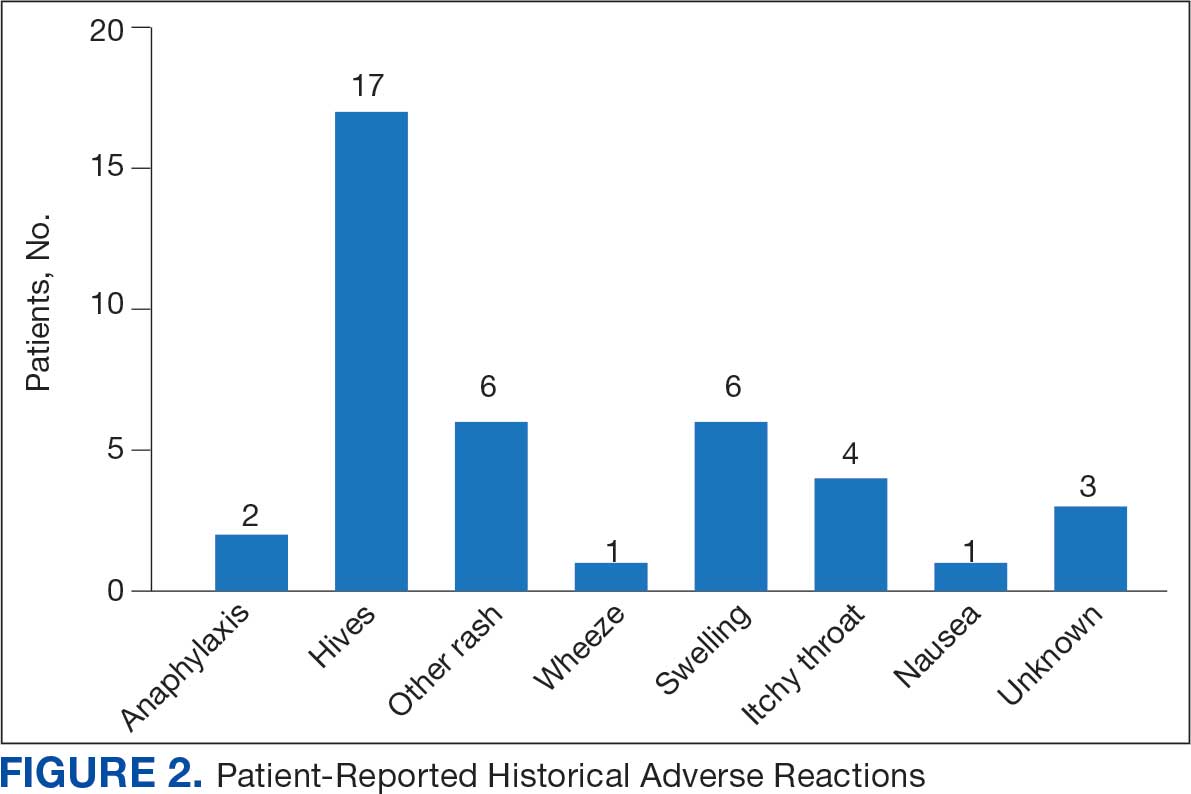

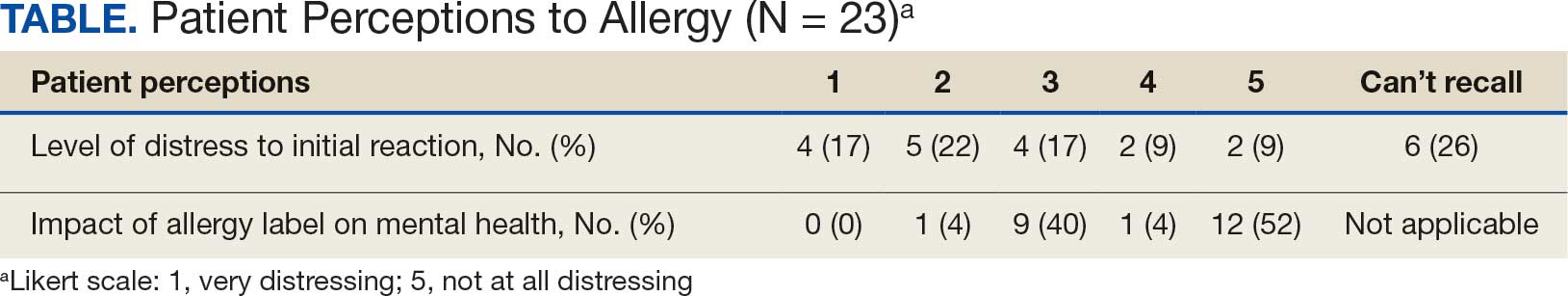

Data collected from patient questionnaires displayed perceived health impacts of a penicillin allergy on the patient population. Patients reported a variety of ADRs to previous administration of penicillin products: 17 (71%) reported urticaria, 2 (8%) reported anaphylaxis, and 3 (13%) were unable to recall the reaction (Figure 2). Nine patients (38%) felt their initial reaction was distressing. Fifteen patients (88%) felt relief following negative testing (Table).

Discussion

To our knowledge, this was the first documented proactive penicillin delabeling QI project in a military clinic treating both active-duty service members and their dependents, modeled on the 2022 drug allergy guidelines.14 Several interesting lessons were learned that may improve future similar QI projects. Only 46% of patients identified as having penicillin allergy presented for evaluation, leaving 42% of available appointments unused. Without prior data on anticipated participation rates, these data provide a crude benchmark for utilization rates, which can inform future resource planning. While attempts were made to contact each patient, additional efforts to publicize the penicillin allergy delabeling campaign would have been useful to improve efficiency.

In addition, when patients with a PEN-FAST score of < 3 were educated about the risks and benefits of each procedure and offered the direct oral graded challenge and skin testing prior to oral challenge, 82% preferred the direct challenge. None of the patients who experienced a penicillin ADR in the past year wished to undergo skin testing or oral challenge, though each was educated on penicillin allergy and the possibility of testing in the future, making each encounter beneficial. Of the 17 patients tested, 16 (94%) tolerated oral amoxicillin and 1 (6%) experienced a mild, self-resolving ADR that was very unlikely of an IgE-mediated origin. Additionally, while plans and preparations for ADRs to the challenges were available, none were required. Patient questionnaires demonstrated the heterogeneity of previous ADRs and their attitude toward their allergy diagnosis. The positive impact of delabeling on patient well-being noted by 88% of patients reinforced the benefit of the effort.

This project was limited by a relatively small sample size, which may not have been large enough to detect ADRs, especially IgE-mediated allergic reactions. Herein lies the importance of having clinicians equipped to treat allergic ADRs to conduct penicillin challenges in the primary care setting. It is prudent to ensure not only proper training of physicians performing these challenges, but also appropriate equipment, medication, and response personnel. Medications that are useful include epinephrine, OAHs, albuterol, steroids, and intravenous fluids.

Having a response area and plan are essential to ensure appropriate care in the rare instance of allergic ADRs progressing to anaphylaxis. In rare cases, emergency medical services may be required and having a plan with appropriate response and transport time is essential to patient safety. This may not be practical in more rural or smaller practices. In those scenarios, it may be helpful to partner with a larger practice to send patients for delabeling or to use clinical space in closer proximity to emergency services. Perhaps an ideal setting might be urgent or emergent care centers due to high acuity resources and frequent prescription of amoxicillin antibiotics; however, this may be complicated by concurrent infections raising the incidence of delayed benign eruptions with amoxicillin ingestion and complicating the patient’s allergy records. Further training of urgent and emergent care practitioners would be helpful for proper patient education regarding antibiotic-associated reactions.

Full testing integration into other primary care clinics may be limited due to the specialized training required for complete skin testing. Nevertheless, as shown in this project, most patients may be delabeled based on a PEN-FAST evaluation followed by oral challenge alone. Incorporation in other QI projects could involve continuing medical education to train staff physicians on PEN-FAST, teaching primary care residents during training, and site visits by allergists to train local physicians on testing. This project involved training 2 PCPs to conduct skin and oral challenge testing using PEN-FAST to guide clinical decision-making with an allergist available for consultation if needed. Future projects might model a similar approach or perhaps focus on training more physicians on oral challenges alone to reach a high percentage of the target population.

Conclusions

This project demonstrates a safe, efficient, and cost-effective model for penicillin allergy delabeling in clinics without regular access to allergy services. The use of PEN-FAST allows a quick and simple method to screen patients with penicillin allergy to meet the goals of the 2022 CBSs, but data are still accumulating to validate this method of screening across populations. This project demonstrates additional support for the use of PEN-FAST, while illustrating appropriate education regarding oral testing technique and its limitations.

Using an EHR report limited the patients in the testing pool and subsequent sample size. This suggests that a primary care identification-driven enrollment in testing may offer even more benefit both in allergy detection and education of testing benefits. Oral challenges are more cost effective, shorter in duration, and have fewer training requirements when compared with antecedent skin testing, making them an ideal option for PCPs in a clinic setting. Trained PCPs may opt to offer periodic appointments for delabeling, or offer days dedicated to delabeling as many patients as possible. Penicillin delabeling is an urgent and expansive charge; this study offers a replicable model for executing this important task.

- Macy E, Poon KYT. Self-reported antibiotic allergy incidence and prevalence: age and sex effects. Am J Med. 2009;122(8):778.e1-778.e7787. doi:10.1016/j.amjmed.2009.01.034

- Zhou L, Dhopeshwarkar N, Blumenthal KG, et al. Drug allergies documented in electronic health records of a large healthcare system. Allergy. 2016;71(9):1305-1313. doi:10.1111/all.12881

- Sullivan TJ, Wedner HJ, Shatz GS, Yecies LD, Parker CW. Skin testing to detect penicillin allergy. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1981;68(3):171-180. doi:10.1016/0091-6749(81)90180-9

- Macy E, Schatz M, Lin C, Poon KY. The falling rate of positive penicillin skin tests from 1995 to 2007. Perm J. 2009;13(2):12-18. doi:10.7812/TPP/08-073

- Fox SJ, Park MA. Penicillin skin testing is a safe and effective tool for evaluating penicillin allergy in the pediatric population. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2014;2(4):439-444. doi:10.1016/j.jaip.2014.04.013

- Solensky R, Jacobs J, Lester M, et al. Penicillin Allergy Evaluation: A Prospective, Multicenter, Open-Label Evaluation of a Comprehensive Penicillin Skin Test Kit. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2019;7(6):1876-1885.e3. doi:10.1016/j.jaip.2019.02.040 7.

- Gonzalez-Estrada A, Park MA, Accarino JJO, et al. Predicting penicillin allergy: A United States multicenter retrospective study. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2024;12(5):1181-1191.e10. doi:10.1016/j.jaip.2024.01.010

- Stüwe HT, Geissler W, Paap A, Cromwell O. The presence of latex can induce false-positive skin tests in subjects tested with penicillin determinants. Allergy. 1997;52(12):1243. doi:10.1111/j.1398-9995.1997.tb00975.x

- Charneski L, Deshpande G, Smith SW. Impact of an antimicrobial allergy label in the medical record on clinical outcomes in hospitalized patients. Pharmacotherapy. 2011;31(8):742-747. doi:10.1592/phco.31.8.742

- Blumenthal KG, Lu N, Zhang Y, Walensky RP, Choi HK. Recorded penicillin allergy and risk of mortality: a population-based matched cohort study. J Gen Intern Med. 2019;34(9):1685-1687. doi:10.1007/s11606-019-04991-y

- Macy E, Contreras R. Health care use and serious infection prevalence associated with penicillin “allergy” in hospitalized patients: A cohort study. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2014;133(3):790-796. doi:10.1016/j.jaci.2013.09.021

- Mattingly TJ II, Fulton A, Lumish RA, et al. The cost of self-reported penicillin allergy: a systematic review. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2018;6(5):1649-1654.e4. doi:10.1016/j.jaip.2017.12.033

- Diplomate Statistics. American Board of Allergy and Immunology website. Published February, 18 2021. Accessed July 28, 2025. https://www.abai.org/statistics_diplomates.asp

- Khan DA, Banerji A, Blumenthal KG, et al. Drug allergy: a 2022 practice parameter update. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2022;150(6):1333-1393. doi:10.1016/j.jaci.2022.08.028

- Mill C, Primeau MN, Medoff E, et al. Assessing the diagnostic properties of a graded oral provocation challenge for the diagnosis of immediate and nonimmediate reactions to amoxicillin in children. JAMA Pediatr. 2016;170:e160033. doi:10.1001/jamapediatrics.2016.0033

- Tucker MH, Lomas CM, Ramchandar N, Waldram JD. Amoxicillin challenge without penicillin skin testing in evaluation of penicillin allergy in a cohort of Marine recruits. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2017;5(3):813-815. doi:10.1016/j.jaip.2017.01.023

- Shenoy ES, Macy E, Rowe T, Blumenthal KG. Evaluation and management of penicillin allergy: a review. JAMA. 2019;321(2):188–99. doi:10.1001/jama.2018.19283

- Blumenthal KG, Li Y, Banerji A, et al. The cost of penicillin allergy evaluation. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2018;6(3):1019-1027.e2. doi:10.1016/j.jaip.2017.08.006

- Banks TA, Tucker M, Macy E. Evaluating penicillin allergies without skin testing. Curr Allergy Asthma Rep. 2019;19(5):27. doi:10.1007/s11882-019-0854-6

- Trubiano JA, Vogrin S, Chua KYL, et al. Development and validation of a penicillin allergy clinical decision rule. JAMA Intern Med. 2020;180(5):745-752. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2020.0403

- Copaescu AM, Vogrin S, James F, et al. Efficacy of a clinical decision rule to enable direct oral challenge in patients with low-risk penicillin allergy: the PALACE randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2023;183(9):944-952. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2023.2986

- Copaescu AM, Vogrin S, Shand G, et al. Validation of the PEN-FAST score in a pediatric population. JAMA Netw Open. 2022;5(9):e2233703. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.33703

- Piotin A, Godet J, Trubiano JA, et al. Predictive factors of amoxicillin immediate hypersensitivity and validation of PEN-FAST clinical decision rule. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2022;128(1):27-32. doi:10.1016/j.anai.2021.07.005

- Su C, Belmont A, Liao J, et al. Evaluating the PEN-FAST clinical decision-making tool to enhance penicillin allergy delabeling. JAMA Intern Med. 2023;183(8):883-885. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2023.1572

Penicillin allergy is common in the United States. About 9.0% to 13.8% of patients have a diagnosed penicillin allergy documented in their electronic health record. The annual incidence rates is 1.1% in males and 1.4% in females.1,2

Penicillin hypersensitivity likely wanes over time. A 1981 study found that 93% of patients who experienced an allergic reaction to penicillin had a positive skin test 7 to 12 months postreaction, but only 22% still had a positive test after 10 years.3 Confirmed type 1 hypersensitivity penicillin allergies, as demonstrated by positive skin prick testing, also are decreasing over time.4 Furthermore, many patients’ reactions may have been misdiagnosed as a penicillin allergy. Upon actual confirmatory testing of penicillin allergy, only 8.5% to 13.8% of patients believed to have a penicillin allergy were positive on skin prick testing of penicillin products.5,6 A 2024 US study found that 11% of individuals with a history of a penicillin reaction tested positive on skin testing.7

The positive predictive value of penicillin allergy skin testing is poorly defined due to the ethical dilemma of orally challenging a patient who demonstrates skin test reactivity. Due to its high negative predictive value (NPV), skin prick combined with intradermal testing has been the gold-standard test in cases of clinical concern.6 Patients with positive skin testing are assumed to be truly positive, and therefore penicillin allergic, even though false-positive results to penicillin skin testing are known to occur.8

Misdiagnosis of penicillin allergy carries substantial clinical and economic consequences. A 2011 study suggested a statistically significant 1.8% increased absolute risk of mortality and 5.5% increased absolute risk of intensive care unit admission for those labeled with penicillin allergy and admitted for an infection.9 Another study found a 14% increase in mortality associated with the diagnosis of penicillin allergy.10 In a 2014 case-control study, penicillin allergy also was associated with a 23.4% greater risk of Clostridioides difficile, 14.1% more methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus, and 30.1% more vancomycin-resistant enterococci infections.11Direct cost savings during an inpatient admission for infection were as much as $609 per patient with additional indirect cost savings of up to $4254 per admission.12 When viewed from the perspective of a health care system, these costs quickly accumulate, negatively impacting the fiscal stability of our patients and placing additional financial strain on an over-burdened system.

If 10% of US patients have penicillin allergy labels, then about 33 million patients might be eligible for delabeling. There are only 6309 board-certified allergists actively practicing in the US, which could amount to about 5231 potential penicillin challenges per allergist, not even including the 3.3 million new patients per year (assuming a 1% incidence).13 Clarifying each patient’s tolerance of penicillin products will clearly require nonallergist cooperation.

The 2022 drug allergy practice parameter update recommends several consensus-based statements (CBSs) to directly address penicillin allergy.14 This guideline recommends proactive efforts to delabel patients with a reported penicillin allergy (CBS 4); advise against testing in cases where the history is inconsistent with a true allergic reaction, though a challenge may be offered (CBS 5); skin testing for those with a history of anaphylaxis or a recent reaction (CBS 6); advise against multiple-day penicillin challenges (CBS 7); advise against skin testing for pediatric patients with benign cutaneous reactions (CBS 8); and recommends direct oral challenge for adults with distant or benign cutaneous reactions (CBS 9). These recommendations create a potentially high demand for delabeling with allergy specialists. One potential solution is to perform direct oral challenges in primary care, emergency departments, and urgent care clinics.

Evidence supporting the safety of direct oral penicillin challenges in low-risk patients was initially noted in the allergy community, but now evidence for their use in primary care clinics is growing—including in children.15 In a military-specific population, an amoxicillin challenge of Marine recruits with suspected penicillin allergy revealed that only 1.5% of those challenged acutely reacted and should be considered allergic to penicillin.16 Historically, in order to refute the diagnosis of penicillin allergy, an allergist would order penicillin skin prick testing. If the test was negative, an allergist would proceed to intradermal testing and if negative again (NPV of 97.9%), proceed to a graded oral challenge.6 However, this process is not fully reproducible in most clinics because the minor determinants mixture used in skin testing is not commercially available.17 Additionally, the full skin testing procedure requires specialized training, is more time-consuming, causes more discomfort, lacks US Food and Drug Administration approval for children, and has a higher cost ($220 per test for each patient as of 2016).18 As such, the movement toward direct oral challenges is progressing. Nonetheless, the best method for primary care or emergency department clinicians to determine who the appropriate patients are for this procedure has not been fully established. Risk tools have been created in the past to help delineate low-risk patients who would be appropriate for direct oral amoxicillin challenges, but these were not widely replicated or validated.19 The PEN-FAST standardized risk score was first published in 2020 and has since been validated in different groups with additional safety data. This scoring system ranges from 0 to 5 points, assigning 2 points for a penicillin reaction within the past five (F) years, 2 points for angioedema/anaphylaxis (A) or a severe (S) cutaneous reaction, and 1 point if treatment (T) was required for the reaction. A score < 3 is considered low-risk and safe for direct oral challenge, although most of the safety data are in patients with a score of 0 or 1.20 The PEN-FAST guided direct oral challenge with an NPV of 96.3% has now been prospectively shown to be noninferior to standard skin prick test/intradermal test/graded challenge for low-risk patients with a PEN-FAST score < 3.21 The PEN-FAST validating study was conducted predominantly with an Australian population of adult White women, but now it also has been validated in children aged > 12 years, as well as in European and North American cohorts.22-24

Air Force Delabeling Program

This article describes a method for proactively, safely, and efficiently delabeling penicillin allergic patients at an Air Force clinic. This quality improvement (QI) report provides a successful model for penicillin allergy delabeling, illustrates lessons learned, and suggests next steps toward improving patient options for an invaluable antibiotic class.

The first step was to proactively delabel penicillin allergy from a population of active duty service members and their dependents. Electronic health record (EHR) allergy search functions are a helpful tool in finding patients with allergy labels. The Kadena Medical Clinic, in Okinawa, Japan, uses the Military Health System GENESIS EHR, which includes a discern reporting portal with a patient allergy search that creates a patient-specific medication allergy report. To compile the most complete database of patients with a penicillin allergy, all 15 potential allergy search options for “penicillin” were selected, as were 4 relevant options for amoxicillin (including options with clavulanate). Including so many options for specific penicillin medication allergies helps add specificity to the diagnosis in the EHR but can make aggregation of data more difficult. The

The complete compiled list was manually reviewed for high-risk patients with severe cutaneous adverse reactions (SCARs) of any age. Patients with pregnancy, unsuitable medical histories (ie, severe asthma), or taking β-blockers were excluded. Patients remaining on the list were contacted by telephone and offered appointments during a single week that was dedicated to penicillin allergy delabeling. Allergists in the Air Force are assigned to a region where they offer allergy services at clinics without a regular allergist. The allergist for the region traveled to the QI site for a 1-week campaign at an estimated cost of $4600. When the patients were contacted, they were briefly informed of the goal of the penicillin delabeling campaign, and if interested, they were scheduled for 1 of 50 available appointments that week. Patients were contacted with enough lead time to stop oral antihistamines (OAH) for ≥ 7 days before the appointment.

Patients were given an intake questionnaire and interviewed about their penicillin allergy history. This questionnaire inquired about the nature of the allergy, mental and physical health impacts of the allergy label, PEN-FAST scoring questions, and posttest attitude toward delabeling, if applicable. Patients with a PEN-FAST score < 3 were offered direct, graded oral challenge or the standard skin prick, followed by intradermal, followed by graded oral challenge protocol. Patients with PEN-FAST scores of ≥ 3 were offered skin testing prior to oral challenge protocol. Patients could decline further testing. If patients wished to proceed, they were asked to complete a written informed consent document.

Oral challenges followed a 10%/90% protocol, beginning with 50 mg of liquid amoxicillin followed by 450 mg after 15 minutes, as long as the patient remained asymptomatic. Challenge forms are available in the eAppendix . After receiving the 450-mg amoxicillin dose, the patient remained in the clinic for 60 minutes before a final clinical evaluation. If the patient remained asymptomatic after this period, the penicillin or amoxicillin allergy was marked as resolved in the EHR. The patients were given contact information for the clinic for follow-up if a delayed reaction was noted and they wished the medication allergy to be re-entered. An EHR encounter note was created for each patient detailing the allergy testing and delabeling.

This campaign was conducted at a basic life support-only facility by a single clinician without medical technician support. An allergic reaction medication kit was available and contained OAHs, intramuscular antihistamines, intramuscular epinephrine, intramuscular corticosteroids, and short-acting β-agonists for nebulization. The facility also had an urgent care room (staffed by primary care practitioners [PCPs]) that could help establish intravenous access and administer fluids if necessary and had previously established plans for emergency patient transport to a higher level of care, if necessary.

Program Outcomes

A list of 65 patients that included both active-duty service members and dependents with penicillin or amoxicillin allergy was created. This list was reviewed by an allergist to identify high-risk individuals, which required about 90 minutes. Two patients (3%) were excluded; 1 had a history of SCAR to penicillin and 1 had a complex medical history requiring continued OAH use. Sixty-three patients were contacted via telephone, and 29 patients (46%) scheduled an appointment. One patient (2%) was identified as penicillin-tolerant during the booking process, and the penicillin allergy was removed without testing (Figure 1).

Of the 29 scheduled patients, 5 patients (17%) failed to present for care. Of the potential appointments set aside for the program, only 42% were used. One patient (4%) who was seen in clinic was delabeled based on history alone as they had previously successfully tolerated a course of amoxicillin. Four patients (17%) declined further testing with a PEN-FAST score > 2 due to a clear history of acute immunoglobulin (Ig) E-mediated reaction to a penicillin product within the past year. One patient (4%) was unable to be tested due to ongoing OAH use and 1 patient (4%) declined further penicillin testing after the discussion about risks, benefits, and alternatives to the procedures offered.

Of the 24 patients who arrived for a clinic appointment, 17 (71%) underwent penicillin allergy delabeling testing: 14 (82%) underwent direct challenge, and 3 (18%) underwent the skin testing before oral amoxicillin challenge procedure. Of the 17 who were tested, 16 (94%) tolerated a total dose of 500 mg of oral amoxicillin within the 1-hour observation period. One tested patient (6%) in the direct oral challenge group experienced an adverse reaction that was described as dull headache and hand tremor after the 50-mg dose; although it self-resolved within 15 minutes, this prompted the patient to discontinue the challenge. This adverse reaction was determined to be very unlikely IgE-mediated. None of the 3 patients who underwent the skin testing before oral challenge protocol experienced an adverse drug reaction (ADR). None of the 17 patients who received any oral amoxicillin required follow-up or reported a delayed cutaneous ADR to the challenge. No OAHs or epinephrine were used for any of the challenges.

Data collected from patient questionnaires displayed perceived health impacts of a penicillin allergy on the patient population. Patients reported a variety of ADRs to previous administration of penicillin products: 17 (71%) reported urticaria, 2 (8%) reported anaphylaxis, and 3 (13%) were unable to recall the reaction (Figure 2). Nine patients (38%) felt their initial reaction was distressing. Fifteen patients (88%) felt relief following negative testing (Table).

Discussion

To our knowledge, this was the first documented proactive penicillin delabeling QI project in a military clinic treating both active-duty service members and their dependents, modeled on the 2022 drug allergy guidelines.14 Several interesting lessons were learned that may improve future similar QI projects. Only 46% of patients identified as having penicillin allergy presented for evaluation, leaving 42% of available appointments unused. Without prior data on anticipated participation rates, these data provide a crude benchmark for utilization rates, which can inform future resource planning. While attempts were made to contact each patient, additional efforts to publicize the penicillin allergy delabeling campaign would have been useful to improve efficiency.

In addition, when patients with a PEN-FAST score of < 3 were educated about the risks and benefits of each procedure and offered the direct oral graded challenge and skin testing prior to oral challenge, 82% preferred the direct challenge. None of the patients who experienced a penicillin ADR in the past year wished to undergo skin testing or oral challenge, though each was educated on penicillin allergy and the possibility of testing in the future, making each encounter beneficial. Of the 17 patients tested, 16 (94%) tolerated oral amoxicillin and 1 (6%) experienced a mild, self-resolving ADR that was very unlikely of an IgE-mediated origin. Additionally, while plans and preparations for ADRs to the challenges were available, none were required. Patient questionnaires demonstrated the heterogeneity of previous ADRs and their attitude toward their allergy diagnosis. The positive impact of delabeling on patient well-being noted by 88% of patients reinforced the benefit of the effort.

This project was limited by a relatively small sample size, which may not have been large enough to detect ADRs, especially IgE-mediated allergic reactions. Herein lies the importance of having clinicians equipped to treat allergic ADRs to conduct penicillin challenges in the primary care setting. It is prudent to ensure not only proper training of physicians performing these challenges, but also appropriate equipment, medication, and response personnel. Medications that are useful include epinephrine, OAHs, albuterol, steroids, and intravenous fluids.

Having a response area and plan are essential to ensure appropriate care in the rare instance of allergic ADRs progressing to anaphylaxis. In rare cases, emergency medical services may be required and having a plan with appropriate response and transport time is essential to patient safety. This may not be practical in more rural or smaller practices. In those scenarios, it may be helpful to partner with a larger practice to send patients for delabeling or to use clinical space in closer proximity to emergency services. Perhaps an ideal setting might be urgent or emergent care centers due to high acuity resources and frequent prescription of amoxicillin antibiotics; however, this may be complicated by concurrent infections raising the incidence of delayed benign eruptions with amoxicillin ingestion and complicating the patient’s allergy records. Further training of urgent and emergent care practitioners would be helpful for proper patient education regarding antibiotic-associated reactions.

Full testing integration into other primary care clinics may be limited due to the specialized training required for complete skin testing. Nevertheless, as shown in this project, most patients may be delabeled based on a PEN-FAST evaluation followed by oral challenge alone. Incorporation in other QI projects could involve continuing medical education to train staff physicians on PEN-FAST, teaching primary care residents during training, and site visits by allergists to train local physicians on testing. This project involved training 2 PCPs to conduct skin and oral challenge testing using PEN-FAST to guide clinical decision-making with an allergist available for consultation if needed. Future projects might model a similar approach or perhaps focus on training more physicians on oral challenges alone to reach a high percentage of the target population.

Conclusions

This project demonstrates a safe, efficient, and cost-effective model for penicillin allergy delabeling in clinics without regular access to allergy services. The use of PEN-FAST allows a quick and simple method to screen patients with penicillin allergy to meet the goals of the 2022 CBSs, but data are still accumulating to validate this method of screening across populations. This project demonstrates additional support for the use of PEN-FAST, while illustrating appropriate education regarding oral testing technique and its limitations.

Using an EHR report limited the patients in the testing pool and subsequent sample size. This suggests that a primary care identification-driven enrollment in testing may offer even more benefit both in allergy detection and education of testing benefits. Oral challenges are more cost effective, shorter in duration, and have fewer training requirements when compared with antecedent skin testing, making them an ideal option for PCPs in a clinic setting. Trained PCPs may opt to offer periodic appointments for delabeling, or offer days dedicated to delabeling as many patients as possible. Penicillin delabeling is an urgent and expansive charge; this study offers a replicable model for executing this important task.

Penicillin allergy is common in the United States. About 9.0% to 13.8% of patients have a diagnosed penicillin allergy documented in their electronic health record. The annual incidence rates is 1.1% in males and 1.4% in females.1,2

Penicillin hypersensitivity likely wanes over time. A 1981 study found that 93% of patients who experienced an allergic reaction to penicillin had a positive skin test 7 to 12 months postreaction, but only 22% still had a positive test after 10 years.3 Confirmed type 1 hypersensitivity penicillin allergies, as demonstrated by positive skin prick testing, also are decreasing over time.4 Furthermore, many patients’ reactions may have been misdiagnosed as a penicillin allergy. Upon actual confirmatory testing of penicillin allergy, only 8.5% to 13.8% of patients believed to have a penicillin allergy were positive on skin prick testing of penicillin products.5,6 A 2024 US study found that 11% of individuals with a history of a penicillin reaction tested positive on skin testing.7

The positive predictive value of penicillin allergy skin testing is poorly defined due to the ethical dilemma of orally challenging a patient who demonstrates skin test reactivity. Due to its high negative predictive value (NPV), skin prick combined with intradermal testing has been the gold-standard test in cases of clinical concern.6 Patients with positive skin testing are assumed to be truly positive, and therefore penicillin allergic, even though false-positive results to penicillin skin testing are known to occur.8

Misdiagnosis of penicillin allergy carries substantial clinical and economic consequences. A 2011 study suggested a statistically significant 1.8% increased absolute risk of mortality and 5.5% increased absolute risk of intensive care unit admission for those labeled with penicillin allergy and admitted for an infection.9 Another study found a 14% increase in mortality associated with the diagnosis of penicillin allergy.10 In a 2014 case-control study, penicillin allergy also was associated with a 23.4% greater risk of Clostridioides difficile, 14.1% more methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus, and 30.1% more vancomycin-resistant enterococci infections.11Direct cost savings during an inpatient admission for infection were as much as $609 per patient with additional indirect cost savings of up to $4254 per admission.12 When viewed from the perspective of a health care system, these costs quickly accumulate, negatively impacting the fiscal stability of our patients and placing additional financial strain on an over-burdened system.

If 10% of US patients have penicillin allergy labels, then about 33 million patients might be eligible for delabeling. There are only 6309 board-certified allergists actively practicing in the US, which could amount to about 5231 potential penicillin challenges per allergist, not even including the 3.3 million new patients per year (assuming a 1% incidence).13 Clarifying each patient’s tolerance of penicillin products will clearly require nonallergist cooperation.

The 2022 drug allergy practice parameter update recommends several consensus-based statements (CBSs) to directly address penicillin allergy.14 This guideline recommends proactive efforts to delabel patients with a reported penicillin allergy (CBS 4); advise against testing in cases where the history is inconsistent with a true allergic reaction, though a challenge may be offered (CBS 5); skin testing for those with a history of anaphylaxis or a recent reaction (CBS 6); advise against multiple-day penicillin challenges (CBS 7); advise against skin testing for pediatric patients with benign cutaneous reactions (CBS 8); and recommends direct oral challenge for adults with distant or benign cutaneous reactions (CBS 9). These recommendations create a potentially high demand for delabeling with allergy specialists. One potential solution is to perform direct oral challenges in primary care, emergency departments, and urgent care clinics.

Evidence supporting the safety of direct oral penicillin challenges in low-risk patients was initially noted in the allergy community, but now evidence for their use in primary care clinics is growing—including in children.15 In a military-specific population, an amoxicillin challenge of Marine recruits with suspected penicillin allergy revealed that only 1.5% of those challenged acutely reacted and should be considered allergic to penicillin.16 Historically, in order to refute the diagnosis of penicillin allergy, an allergist would order penicillin skin prick testing. If the test was negative, an allergist would proceed to intradermal testing and if negative again (NPV of 97.9%), proceed to a graded oral challenge.6 However, this process is not fully reproducible in most clinics because the minor determinants mixture used in skin testing is not commercially available.17 Additionally, the full skin testing procedure requires specialized training, is more time-consuming, causes more discomfort, lacks US Food and Drug Administration approval for children, and has a higher cost ($220 per test for each patient as of 2016).18 As such, the movement toward direct oral challenges is progressing. Nonetheless, the best method for primary care or emergency department clinicians to determine who the appropriate patients are for this procedure has not been fully established. Risk tools have been created in the past to help delineate low-risk patients who would be appropriate for direct oral amoxicillin challenges, but these were not widely replicated or validated.19 The PEN-FAST standardized risk score was first published in 2020 and has since been validated in different groups with additional safety data. This scoring system ranges from 0 to 5 points, assigning 2 points for a penicillin reaction within the past five (F) years, 2 points for angioedema/anaphylaxis (A) or a severe (S) cutaneous reaction, and 1 point if treatment (T) was required for the reaction. A score < 3 is considered low-risk and safe for direct oral challenge, although most of the safety data are in patients with a score of 0 or 1.20 The PEN-FAST guided direct oral challenge with an NPV of 96.3% has now been prospectively shown to be noninferior to standard skin prick test/intradermal test/graded challenge for low-risk patients with a PEN-FAST score < 3.21 The PEN-FAST validating study was conducted predominantly with an Australian population of adult White women, but now it also has been validated in children aged > 12 years, as well as in European and North American cohorts.22-24

Air Force Delabeling Program

This article describes a method for proactively, safely, and efficiently delabeling penicillin allergic patients at an Air Force clinic. This quality improvement (QI) report provides a successful model for penicillin allergy delabeling, illustrates lessons learned, and suggests next steps toward improving patient options for an invaluable antibiotic class.

The first step was to proactively delabel penicillin allergy from a population of active duty service members and their dependents. Electronic health record (EHR) allergy search functions are a helpful tool in finding patients with allergy labels. The Kadena Medical Clinic, in Okinawa, Japan, uses the Military Health System GENESIS EHR, which includes a discern reporting portal with a patient allergy search that creates a patient-specific medication allergy report. To compile the most complete database of patients with a penicillin allergy, all 15 potential allergy search options for “penicillin” were selected, as were 4 relevant options for amoxicillin (including options with clavulanate). Including so many options for specific penicillin medication allergies helps add specificity to the diagnosis in the EHR but can make aggregation of data more difficult. The

The complete compiled list was manually reviewed for high-risk patients with severe cutaneous adverse reactions (SCARs) of any age. Patients with pregnancy, unsuitable medical histories (ie, severe asthma), or taking β-blockers were excluded. Patients remaining on the list were contacted by telephone and offered appointments during a single week that was dedicated to penicillin allergy delabeling. Allergists in the Air Force are assigned to a region where they offer allergy services at clinics without a regular allergist. The allergist for the region traveled to the QI site for a 1-week campaign at an estimated cost of $4600. When the patients were contacted, they were briefly informed of the goal of the penicillin delabeling campaign, and if interested, they were scheduled for 1 of 50 available appointments that week. Patients were contacted with enough lead time to stop oral antihistamines (OAH) for ≥ 7 days before the appointment.

Patients were given an intake questionnaire and interviewed about their penicillin allergy history. This questionnaire inquired about the nature of the allergy, mental and physical health impacts of the allergy label, PEN-FAST scoring questions, and posttest attitude toward delabeling, if applicable. Patients with a PEN-FAST score < 3 were offered direct, graded oral challenge or the standard skin prick, followed by intradermal, followed by graded oral challenge protocol. Patients with PEN-FAST scores of ≥ 3 were offered skin testing prior to oral challenge protocol. Patients could decline further testing. If patients wished to proceed, they were asked to complete a written informed consent document.

Oral challenges followed a 10%/90% protocol, beginning with 50 mg of liquid amoxicillin followed by 450 mg after 15 minutes, as long as the patient remained asymptomatic. Challenge forms are available in the eAppendix . After receiving the 450-mg amoxicillin dose, the patient remained in the clinic for 60 minutes before a final clinical evaluation. If the patient remained asymptomatic after this period, the penicillin or amoxicillin allergy was marked as resolved in the EHR. The patients were given contact information for the clinic for follow-up if a delayed reaction was noted and they wished the medication allergy to be re-entered. An EHR encounter note was created for each patient detailing the allergy testing and delabeling.

This campaign was conducted at a basic life support-only facility by a single clinician without medical technician support. An allergic reaction medication kit was available and contained OAHs, intramuscular antihistamines, intramuscular epinephrine, intramuscular corticosteroids, and short-acting β-agonists for nebulization. The facility also had an urgent care room (staffed by primary care practitioners [PCPs]) that could help establish intravenous access and administer fluids if necessary and had previously established plans for emergency patient transport to a higher level of care, if necessary.

Program Outcomes

A list of 65 patients that included both active-duty service members and dependents with penicillin or amoxicillin allergy was created. This list was reviewed by an allergist to identify high-risk individuals, which required about 90 minutes. Two patients (3%) were excluded; 1 had a history of SCAR to penicillin and 1 had a complex medical history requiring continued OAH use. Sixty-three patients were contacted via telephone, and 29 patients (46%) scheduled an appointment. One patient (2%) was identified as penicillin-tolerant during the booking process, and the penicillin allergy was removed without testing (Figure 1).

Of the 29 scheduled patients, 5 patients (17%) failed to present for care. Of the potential appointments set aside for the program, only 42% were used. One patient (4%) who was seen in clinic was delabeled based on history alone as they had previously successfully tolerated a course of amoxicillin. Four patients (17%) declined further testing with a PEN-FAST score > 2 due to a clear history of acute immunoglobulin (Ig) E-mediated reaction to a penicillin product within the past year. One patient (4%) was unable to be tested due to ongoing OAH use and 1 patient (4%) declined further penicillin testing after the discussion about risks, benefits, and alternatives to the procedures offered.

Of the 24 patients who arrived for a clinic appointment, 17 (71%) underwent penicillin allergy delabeling testing: 14 (82%) underwent direct challenge, and 3 (18%) underwent the skin testing before oral amoxicillin challenge procedure. Of the 17 who were tested, 16 (94%) tolerated a total dose of 500 mg of oral amoxicillin within the 1-hour observation period. One tested patient (6%) in the direct oral challenge group experienced an adverse reaction that was described as dull headache and hand tremor after the 50-mg dose; although it self-resolved within 15 minutes, this prompted the patient to discontinue the challenge. This adverse reaction was determined to be very unlikely IgE-mediated. None of the 3 patients who underwent the skin testing before oral challenge protocol experienced an adverse drug reaction (ADR). None of the 17 patients who received any oral amoxicillin required follow-up or reported a delayed cutaneous ADR to the challenge. No OAHs or epinephrine were used for any of the challenges.

Data collected from patient questionnaires displayed perceived health impacts of a penicillin allergy on the patient population. Patients reported a variety of ADRs to previous administration of penicillin products: 17 (71%) reported urticaria, 2 (8%) reported anaphylaxis, and 3 (13%) were unable to recall the reaction (Figure 2). Nine patients (38%) felt their initial reaction was distressing. Fifteen patients (88%) felt relief following negative testing (Table).

Discussion

To our knowledge, this was the first documented proactive penicillin delabeling QI project in a military clinic treating both active-duty service members and their dependents, modeled on the 2022 drug allergy guidelines.14 Several interesting lessons were learned that may improve future similar QI projects. Only 46% of patients identified as having penicillin allergy presented for evaluation, leaving 42% of available appointments unused. Without prior data on anticipated participation rates, these data provide a crude benchmark for utilization rates, which can inform future resource planning. While attempts were made to contact each patient, additional efforts to publicize the penicillin allergy delabeling campaign would have been useful to improve efficiency.

In addition, when patients with a PEN-FAST score of < 3 were educated about the risks and benefits of each procedure and offered the direct oral graded challenge and skin testing prior to oral challenge, 82% preferred the direct challenge. None of the patients who experienced a penicillin ADR in the past year wished to undergo skin testing or oral challenge, though each was educated on penicillin allergy and the possibility of testing in the future, making each encounter beneficial. Of the 17 patients tested, 16 (94%) tolerated oral amoxicillin and 1 (6%) experienced a mild, self-resolving ADR that was very unlikely of an IgE-mediated origin. Additionally, while plans and preparations for ADRs to the challenges were available, none were required. Patient questionnaires demonstrated the heterogeneity of previous ADRs and their attitude toward their allergy diagnosis. The positive impact of delabeling on patient well-being noted by 88% of patients reinforced the benefit of the effort.

This project was limited by a relatively small sample size, which may not have been large enough to detect ADRs, especially IgE-mediated allergic reactions. Herein lies the importance of having clinicians equipped to treat allergic ADRs to conduct penicillin challenges in the primary care setting. It is prudent to ensure not only proper training of physicians performing these challenges, but also appropriate equipment, medication, and response personnel. Medications that are useful include epinephrine, OAHs, albuterol, steroids, and intravenous fluids.

Having a response area and plan are essential to ensure appropriate care in the rare instance of allergic ADRs progressing to anaphylaxis. In rare cases, emergency medical services may be required and having a plan with appropriate response and transport time is essential to patient safety. This may not be practical in more rural or smaller practices. In those scenarios, it may be helpful to partner with a larger practice to send patients for delabeling or to use clinical space in closer proximity to emergency services. Perhaps an ideal setting might be urgent or emergent care centers due to high acuity resources and frequent prescription of amoxicillin antibiotics; however, this may be complicated by concurrent infections raising the incidence of delayed benign eruptions with amoxicillin ingestion and complicating the patient’s allergy records. Further training of urgent and emergent care practitioners would be helpful for proper patient education regarding antibiotic-associated reactions.

Full testing integration into other primary care clinics may be limited due to the specialized training required for complete skin testing. Nevertheless, as shown in this project, most patients may be delabeled based on a PEN-FAST evaluation followed by oral challenge alone. Incorporation in other QI projects could involve continuing medical education to train staff physicians on PEN-FAST, teaching primary care residents during training, and site visits by allergists to train local physicians on testing. This project involved training 2 PCPs to conduct skin and oral challenge testing using PEN-FAST to guide clinical decision-making with an allergist available for consultation if needed. Future projects might model a similar approach or perhaps focus on training more physicians on oral challenges alone to reach a high percentage of the target population.

Conclusions

This project demonstrates a safe, efficient, and cost-effective model for penicillin allergy delabeling in clinics without regular access to allergy services. The use of PEN-FAST allows a quick and simple method to screen patients with penicillin allergy to meet the goals of the 2022 CBSs, but data are still accumulating to validate this method of screening across populations. This project demonstrates additional support for the use of PEN-FAST, while illustrating appropriate education regarding oral testing technique and its limitations.

Using an EHR report limited the patients in the testing pool and subsequent sample size. This suggests that a primary care identification-driven enrollment in testing may offer even more benefit both in allergy detection and education of testing benefits. Oral challenges are more cost effective, shorter in duration, and have fewer training requirements when compared with antecedent skin testing, making them an ideal option for PCPs in a clinic setting. Trained PCPs may opt to offer periodic appointments for delabeling, or offer days dedicated to delabeling as many patients as possible. Penicillin delabeling is an urgent and expansive charge; this study offers a replicable model for executing this important task.

- Macy E, Poon KYT. Self-reported antibiotic allergy incidence and prevalence: age and sex effects. Am J Med. 2009;122(8):778.e1-778.e7787. doi:10.1016/j.amjmed.2009.01.034

- Zhou L, Dhopeshwarkar N, Blumenthal KG, et al. Drug allergies documented in electronic health records of a large healthcare system. Allergy. 2016;71(9):1305-1313. doi:10.1111/all.12881

- Sullivan TJ, Wedner HJ, Shatz GS, Yecies LD, Parker CW. Skin testing to detect penicillin allergy. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1981;68(3):171-180. doi:10.1016/0091-6749(81)90180-9

- Macy E, Schatz M, Lin C, Poon KY. The falling rate of positive penicillin skin tests from 1995 to 2007. Perm J. 2009;13(2):12-18. doi:10.7812/TPP/08-073

- Fox SJ, Park MA. Penicillin skin testing is a safe and effective tool for evaluating penicillin allergy in the pediatric population. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2014;2(4):439-444. doi:10.1016/j.jaip.2014.04.013

- Solensky R, Jacobs J, Lester M, et al. Penicillin Allergy Evaluation: A Prospective, Multicenter, Open-Label Evaluation of a Comprehensive Penicillin Skin Test Kit. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2019;7(6):1876-1885.e3. doi:10.1016/j.jaip.2019.02.040 7.

- Gonzalez-Estrada A, Park MA, Accarino JJO, et al. Predicting penicillin allergy: A United States multicenter retrospective study. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2024;12(5):1181-1191.e10. doi:10.1016/j.jaip.2024.01.010

- Stüwe HT, Geissler W, Paap A, Cromwell O. The presence of latex can induce false-positive skin tests in subjects tested with penicillin determinants. Allergy. 1997;52(12):1243. doi:10.1111/j.1398-9995.1997.tb00975.x

- Charneski L, Deshpande G, Smith SW. Impact of an antimicrobial allergy label in the medical record on clinical outcomes in hospitalized patients. Pharmacotherapy. 2011;31(8):742-747. doi:10.1592/phco.31.8.742

- Blumenthal KG, Lu N, Zhang Y, Walensky RP, Choi HK. Recorded penicillin allergy and risk of mortality: a population-based matched cohort study. J Gen Intern Med. 2019;34(9):1685-1687. doi:10.1007/s11606-019-04991-y

- Macy E, Contreras R. Health care use and serious infection prevalence associated with penicillin “allergy” in hospitalized patients: A cohort study. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2014;133(3):790-796. doi:10.1016/j.jaci.2013.09.021

- Mattingly TJ II, Fulton A, Lumish RA, et al. The cost of self-reported penicillin allergy: a systematic review. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2018;6(5):1649-1654.e4. doi:10.1016/j.jaip.2017.12.033

- Diplomate Statistics. American Board of Allergy and Immunology website. Published February, 18 2021. Accessed July 28, 2025. https://www.abai.org/statistics_diplomates.asp

- Khan DA, Banerji A, Blumenthal KG, et al. Drug allergy: a 2022 practice parameter update. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2022;150(6):1333-1393. doi:10.1016/j.jaci.2022.08.028

- Mill C, Primeau MN, Medoff E, et al. Assessing the diagnostic properties of a graded oral provocation challenge for the diagnosis of immediate and nonimmediate reactions to amoxicillin in children. JAMA Pediatr. 2016;170:e160033. doi:10.1001/jamapediatrics.2016.0033

- Tucker MH, Lomas CM, Ramchandar N, Waldram JD. Amoxicillin challenge without penicillin skin testing in evaluation of penicillin allergy in a cohort of Marine recruits. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2017;5(3):813-815. doi:10.1016/j.jaip.2017.01.023

- Shenoy ES, Macy E, Rowe T, Blumenthal KG. Evaluation and management of penicillin allergy: a review. JAMA. 2019;321(2):188–99. doi:10.1001/jama.2018.19283

- Blumenthal KG, Li Y, Banerji A, et al. The cost of penicillin allergy evaluation. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2018;6(3):1019-1027.e2. doi:10.1016/j.jaip.2017.08.006

- Banks TA, Tucker M, Macy E. Evaluating penicillin allergies without skin testing. Curr Allergy Asthma Rep. 2019;19(5):27. doi:10.1007/s11882-019-0854-6

- Trubiano JA, Vogrin S, Chua KYL, et al. Development and validation of a penicillin allergy clinical decision rule. JAMA Intern Med. 2020;180(5):745-752. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2020.0403

- Copaescu AM, Vogrin S, James F, et al. Efficacy of a clinical decision rule to enable direct oral challenge in patients with low-risk penicillin allergy: the PALACE randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2023;183(9):944-952. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2023.2986

- Copaescu AM, Vogrin S, Shand G, et al. Validation of the PEN-FAST score in a pediatric population. JAMA Netw Open. 2022;5(9):e2233703. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.33703

- Piotin A, Godet J, Trubiano JA, et al. Predictive factors of amoxicillin immediate hypersensitivity and validation of PEN-FAST clinical decision rule. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2022;128(1):27-32. doi:10.1016/j.anai.2021.07.005

- Su C, Belmont A, Liao J, et al. Evaluating the PEN-FAST clinical decision-making tool to enhance penicillin allergy delabeling. JAMA Intern Med. 2023;183(8):883-885. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2023.1572

- Macy E, Poon KYT. Self-reported antibiotic allergy incidence and prevalence: age and sex effects. Am J Med. 2009;122(8):778.e1-778.e7787. doi:10.1016/j.amjmed.2009.01.034

- Zhou L, Dhopeshwarkar N, Blumenthal KG, et al. Drug allergies documented in electronic health records of a large healthcare system. Allergy. 2016;71(9):1305-1313. doi:10.1111/all.12881

- Sullivan TJ, Wedner HJ, Shatz GS, Yecies LD, Parker CW. Skin testing to detect penicillin allergy. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1981;68(3):171-180. doi:10.1016/0091-6749(81)90180-9

- Macy E, Schatz M, Lin C, Poon KY. The falling rate of positive penicillin skin tests from 1995 to 2007. Perm J. 2009;13(2):12-18. doi:10.7812/TPP/08-073

- Fox SJ, Park MA. Penicillin skin testing is a safe and effective tool for evaluating penicillin allergy in the pediatric population. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2014;2(4):439-444. doi:10.1016/j.jaip.2014.04.013

- Solensky R, Jacobs J, Lester M, et al. Penicillin Allergy Evaluation: A Prospective, Multicenter, Open-Label Evaluation of a Comprehensive Penicillin Skin Test Kit. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2019;7(6):1876-1885.e3. doi:10.1016/j.jaip.2019.02.040 7.

- Gonzalez-Estrada A, Park MA, Accarino JJO, et al. Predicting penicillin allergy: A United States multicenter retrospective study. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2024;12(5):1181-1191.e10. doi:10.1016/j.jaip.2024.01.010

- Stüwe HT, Geissler W, Paap A, Cromwell O. The presence of latex can induce false-positive skin tests in subjects tested with penicillin determinants. Allergy. 1997;52(12):1243. doi:10.1111/j.1398-9995.1997.tb00975.x

- Charneski L, Deshpande G, Smith SW. Impact of an antimicrobial allergy label in the medical record on clinical outcomes in hospitalized patients. Pharmacotherapy. 2011;31(8):742-747. doi:10.1592/phco.31.8.742

- Blumenthal KG, Lu N, Zhang Y, Walensky RP, Choi HK. Recorded penicillin allergy and risk of mortality: a population-based matched cohort study. J Gen Intern Med. 2019;34(9):1685-1687. doi:10.1007/s11606-019-04991-y

- Macy E, Contreras R. Health care use and serious infection prevalence associated with penicillin “allergy” in hospitalized patients: A cohort study. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2014;133(3):790-796. doi:10.1016/j.jaci.2013.09.021

- Mattingly TJ II, Fulton A, Lumish RA, et al. The cost of self-reported penicillin allergy: a systematic review. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2018;6(5):1649-1654.e4. doi:10.1016/j.jaip.2017.12.033

- Diplomate Statistics. American Board of Allergy and Immunology website. Published February, 18 2021. Accessed July 28, 2025. https://www.abai.org/statistics_diplomates.asp

- Khan DA, Banerji A, Blumenthal KG, et al. Drug allergy: a 2022 practice parameter update. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2022;150(6):1333-1393. doi:10.1016/j.jaci.2022.08.028

- Mill C, Primeau MN, Medoff E, et al. Assessing the diagnostic properties of a graded oral provocation challenge for the diagnosis of immediate and nonimmediate reactions to amoxicillin in children. JAMA Pediatr. 2016;170:e160033. doi:10.1001/jamapediatrics.2016.0033

- Tucker MH, Lomas CM, Ramchandar N, Waldram JD. Amoxicillin challenge without penicillin skin testing in evaluation of penicillin allergy in a cohort of Marine recruits. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2017;5(3):813-815. doi:10.1016/j.jaip.2017.01.023

- Shenoy ES, Macy E, Rowe T, Blumenthal KG. Evaluation and management of penicillin allergy: a review. JAMA. 2019;321(2):188–99. doi:10.1001/jama.2018.19283

- Blumenthal KG, Li Y, Banerji A, et al. The cost of penicillin allergy evaluation. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2018;6(3):1019-1027.e2. doi:10.1016/j.jaip.2017.08.006

- Banks TA, Tucker M, Macy E. Evaluating penicillin allergies without skin testing. Curr Allergy Asthma Rep. 2019;19(5):27. doi:10.1007/s11882-019-0854-6

- Trubiano JA, Vogrin S, Chua KYL, et al. Development and validation of a penicillin allergy clinical decision rule. JAMA Intern Med. 2020;180(5):745-752. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2020.0403

- Copaescu AM, Vogrin S, James F, et al. Efficacy of a clinical decision rule to enable direct oral challenge in patients with low-risk penicillin allergy: the PALACE randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2023;183(9):944-952. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2023.2986

- Copaescu AM, Vogrin S, Shand G, et al. Validation of the PEN-FAST score in a pediatric population. JAMA Netw Open. 2022;5(9):e2233703. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.33703

- Piotin A, Godet J, Trubiano JA, et al. Predictive factors of amoxicillin immediate hypersensitivity and validation of PEN-FAST clinical decision rule. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2022;128(1):27-32. doi:10.1016/j.anai.2021.07.005

- Su C, Belmont A, Liao J, et al. Evaluating the PEN-FAST clinical decision-making tool to enhance penicillin allergy delabeling. JAMA Intern Med. 2023;183(8):883-885. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2023.1572

Proactive Penicillin Allergy Delabeling: Lessons Learned From a Quality Improvement Project

Proactive Penicillin Allergy Delabeling: Lessons Learned From a Quality Improvement Project