User login

Hospitalists in Haiti

The patient had a number of wounds to her battered body, but her most pressing question was how to stanch the flow of milk from her breasts, recalls Lisa Luly-Rivera, MD. The woman was in an endless line of people Dr. Luly-Rivera, a hospitalist at the University of Miami (Fla.) Hospital, cared for during a five-day medical volunteer mission to Haiti in the aftermath of the January earthquake that devastated much of the country.

“She had lost everything, including her seven-month-old baby, who she watched die in the earthquake. She was still lactating and wanted to know how to get the milk to stop,” Dr. Luly-Rivera says. “I heard story after story after story like this. For me, it was emotionally jarring.”

A Haitian-American who has extended-family members in Haiti who survived the Jan. 12 earthquake, Dr. Luly-Rivera leaped at the chance to participate in the medical relief effort organized by the university’s Miller School of Medicine in conjunction with Project Medishare and Jackson Memorial Hospital in Miami. But soon after arriving in the Haitian capital of Port-au-Prince on Jan. 20 and witnessing the magnitude of human suffering there, she second-guessed her decision, wondering if she was emotionally strong enough to deal with such tragedy.

She wasn’t the only one with reservations. Some at the University of Miami Hospital were skeptical that hospitalists could help the situation in Haiti. They questioned why she and her colleagues were included on the volunteer team, Dr. Luly-Rivera says. Ultimately, she proved herself—and the doubters—wrong.

“As internists, we were very valuable there,” says Dr. Luly-Rivera, who logged long hours treating patients and listening to their stories.

Determined to do their part to help survivors of the earthquake, hospitalists across the country joined a surge of American medical personnel in Haiti. Once there, they faced a severely traumatized populace (the Haitian government estimates more than 215,000 were killed and 300,000 injured in the quake), a crippled hospital infrastructure, and a debilitated public health system that had failed even before the earthquake to provide adequate sanitation, vaccinations, infectious-disease control, and basic primary care.

“If Haiti wasn’t chronically poor, if it hadn’t suffered for so long outside of the eye of the world community, then the devastation would have never been so great,” says Sriram Shamasunder, MD, a hospitalist and assistant clinical professor at the University of California at San Francisco’s Department of Medicine who volunteered in the relief effort with the Boston-based nonprofit group Partners in Health. “The house that crumbled is the one chronic poverty built.”

Worthy Cause, Unimaginable Conditions

Mario A. Reyes, MD, FHM, director of the Division of Pediatric Hospital Medicine at Miami Children’s Hospital, shakes his head when he thinks of the conditions in Haiti, one of the poorest nations in the Western Hemisphere. “This is how unfair the world is, that you can fly one and a half hours from a country of such plenty to a country with so much poverty,” says Dr. Reyes, who made his third trip to the island nation in as many years. “Once you go the first time, you feel a connection to the country and the people. It’s a sense of duty to help a very poor neighbor.”

This time, Dr. Reyes and colleague Andrea Maggioni, MD, organized the 75-cot pediatric unit of a 250-bed tent hospital that the University of Miami opened Jan. 21 at the airport in Port-au-Prince in collaboration with Jackson Memorial Hospital and Miami-based Project Medishare, a nonprofit organization founded by doctors from the University of Miami’s medical school in an effort to bring quality healthcare and development services to Haiti.

“There were a few general pediatricians there. They relied on us to lead the way,” Dr. Reyes says. “When I got to the pediatric tent, I saw so many kids screaming at the same time, some with bones sticking out of their body. There’s nothing more gut-wrenching than that. I spent the first night giving morphine and antibiotics like lollipops.”

Before the tent hospital—four tents in all, one for supplies, one for volunteers to sleep in, and two for patients—was set up at the airport, doctors from the University of Miami and its partnering organizations treated adult and pediatric patients at a facility in the United Nations compound in Port-au-Prince. It was utter chaos, according to Amir Jaffer, MD, FHM, chief of the Division of Hospital Medicine and an associate professor of medicine at the Miller School of Medicine. He described earthquake survivors walking around in a daze amidst the rubble, and huge numbers of people searching for food and water.

Same Work, Makeshift Surroundings

Drawing on his HM experience, Dr. Jaffer helped orchestrate the transfer of approximately 140 patients from the makeshift U.N. hospital to the university’s tent hospital a couple of miles away. He also helped lead the effort to organize patients once they arrived at the new facility, which featured a supply tent, staff sleeping tent, medical tent, and surgical tent with four operating rooms. Each patient received a medical wristband and medical record number, and had their medical care charted.

An ICU was set up for those patients who were in more serious condition, and severely ill and injured patients were airlifted to medical centers in Florida and the USNS Comfort, a U.S. Navy ship dispatched to Haiti to provide full hospital service to earthquake survivors. The tent hospital had nearly 250 patients by the end of his five-day trip, Dr. Jaffer says.

Hospitalists administered IV fluids, prescribed antibiotics and pain medication, treated infected wounds, managed patients with dehydration, gastroenteritis, and tetanus, and triaged patients. “Many patients had splints placed in the field, and we would do X-rays to confirm the diagnosis. Patients were being casted right after diagnosis,” Dr. Jaffer says.

Outside the Capital

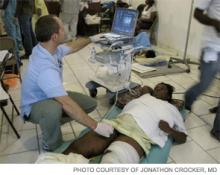

Hospitalists volunteering with Partners in Health (PIH) were tasked with maximizing the time the surgical team could spend in the OR by assessing incoming patients, triaging cases, providing post-op care, monitoring for development of medical issues related to trauma, and ensuring that every patient was seen daily, says Jonathan Crocker, MD, a hospitalist at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center in Boston.

Dr. Crocker arrived in Haiti four days after the earthquake and was sent to Clinique Bon Saveur, a hospital in Cange, a town located two hours outside the capital on the country’s Central Plateau. The hospital is one of 10 health facilities run by Zamni Lasante, PIH’s sister organization in Haiti. Dr. Shamasunder, of UC San Francisco, arrived in the country a few days later and was stationed at St. Marc Hospital, on the west coast of the island, about 60 miles from Port-au-Prince.

At St. Marc’s, conditions were “chaotic but functioning, bare-bones but a work in progress,” as Haitian doctors began returning to work and Creole-speaking nurses from the U.S. reached the hospital, Dr. Shamasunder explains. PIH volunteers coordinated with teams from Canada and Nepal to provide the best possible medical care to patients dealing with sepsis, serious wounds, and heart failure.

Hundreds of patients, many with multiple injuries, had been streaming into Clinique Bon Saveur since the day the earthquake struck. When Dr. Crocker arrived, the hospital was overcrowded, spilling into makeshift wards that had been set up in a church and a nearby school.

“As a hospitalist, my first concern upon arrival was anticipating the likely medical complications we would encounter with a large population of patients having experienced physical trauma,” Dr. Crocker says. “These complications included, namely, DVT and PE events, compartment syndrome, rhabdomyolysis with renal failure, hyperkalemia, wound infection, and sepsis.”

After speaking with their Haitian colleagues, PIH volunteers placed all adult patients at Clinique Bon Saveur on heparin prophylaxis. They also instituted a standard antibiotic regimen for all patients with open fractures, ensured patients received tetanus shots, and made it a priority to see every patient daily in an effort to prevent compartment syndrome and complications from rhabdomyolysis.

“As we identified more patients with acute renal failure, we moved into active screening with ‘creatinine rounds,’ where we performed BUN/Cr checks on any patient suspected of having suffered major crush injuries,” says Dr. Crocker, who used a portable ultrasound to assess patients for suspected lower-extremity DVTs. “As a team, we made a daily A, B, and C priority list for patients in need of surgeries available at the hospital, and a list of patients with injuries too complex for our surgical teams requiring transfer.”

Resume Expansion

Back at the University of Miami’s tent facility, hospitalists were chipping in wherever help was needed. “I cleaned rooms, I took out the trash, I swept floors, I dispensed medicine from the pharmacy. I just did everything,” Dr. Luly-Rivera says. “You have to go with an open mind and be prepared to do things outside your own discipline.”

Volunteers must be prepared to deal with difficult patients who are under considerable stress over their present and future situations, Dr. Luly-Rivera explains. She worries about what is to come for a country that’s ill-equipped to handle so many physically disabled people. For years, there will be a pressing need for orthopedic surgeons and physical and occupational therapists, she says.

Earthquake survivors also will need help in coping with the psychological trauma they’ve endured, says Dr. Reyes, who frequently played the role of hospital clown in the tent facility’s pediatric ward—just to help the children to laugh a bit.

“These kids are fully traumatized. They don’t want to go inside buildings because they’re afraid they will collapse,” he says. “There’s a high percentage of them who lost at least one parent in the disaster. When you go to discharge them, many don’t have a home to go to. You just feel tremendous sadness.”

Emotional Connection

The sorrow intensified when Dr. Reyes returned to work after returning from his trip to Haiti. “You can barely eat because you have a knot in your throat,” he says.

Upon her return to Miami, Dr. Luly-Rivera spent almost every spare minute watching news coverage on television and reading about the relief effort online. It was difficult for her to concentrate when working, she admits.

“It wasn’t that I felt the patients here didn’t need me,” she says. “It’s just that my mind was still in Haiti and thinking about my patients there. I had to let it go.”

Feelings of sadness and grief are common reactions to witnessing acute injuries and loss of life, says Dr. Jaffer. Some people react by refusing to leave until the work is done, or returning to the relief effort before they are ready.

—Mario Reyes, MD, FHM, director, Division of Pediatric Hospital Medicine, Miami Children’s Hospital

“Medical volunteerism shows you there is life beyond what you do in your workplace. It allows you to bridge the gap between your job and people who are less fortunate. The experience can be invigorating, but it can also be stress-inducing and lead to depression,” Dr. Jaffer says. “It’s always good to have someone you pair up with to monitor your stress level.”

After taking time to decompress, Drs. Luly-Rivera and Reyes plan to return to Haiti. They hope healthcare workers from all parts of the U.S. will continue to volunteer in the months ahead. Haiti’s weighty issues demand that non-governmental organizations (NGOs) working in the country stay and better coordinate their efforts, Dr. Reyes says.

“Ultimately, it is going to be important for any group present in Haiti to work to support the Haitian medical community,” Dr. Crocker adds. “The long-term recovery and rehabilitation of so many thousands of patients will be possible only through a robust, functional, public healthcare delivery system.”

It remains to be seen how many NGOs and volunteers will still be in Haiti a few months from now, the hospitalists said.

It’s always a concern that the attention of the global community may shift away from Haiti when the next calamity strikes in another part of the world, Dr. Jaffer notes. If the focus stays on Haiti as it rebuilds, then possibly some good will come out of the earthquake, Dr. Luly-Rivera says. But if NGOs begin to leave in the short term, the quake would only be the latest setback for one of the world’s poorest and most underdeveloped countries.

Even if the latter were to happen, Dr. Luly-Rivera still says she and other volunteers make a difference. “I’m still glad I went,” she says. “The people were so thankful.”

“You see the best of the American people there,” Dr. Reyes adds. “It’s encouraging and uplifting. It brings back faith in the medical profession and faith in people.” TH

Lisa Ryan is a freelance writer based in New Jersey.

The patient had a number of wounds to her battered body, but her most pressing question was how to stanch the flow of milk from her breasts, recalls Lisa Luly-Rivera, MD. The woman was in an endless line of people Dr. Luly-Rivera, a hospitalist at the University of Miami (Fla.) Hospital, cared for during a five-day medical volunteer mission to Haiti in the aftermath of the January earthquake that devastated much of the country.

“She had lost everything, including her seven-month-old baby, who she watched die in the earthquake. She was still lactating and wanted to know how to get the milk to stop,” Dr. Luly-Rivera says. “I heard story after story after story like this. For me, it was emotionally jarring.”

A Haitian-American who has extended-family members in Haiti who survived the Jan. 12 earthquake, Dr. Luly-Rivera leaped at the chance to participate in the medical relief effort organized by the university’s Miller School of Medicine in conjunction with Project Medishare and Jackson Memorial Hospital in Miami. But soon after arriving in the Haitian capital of Port-au-Prince on Jan. 20 and witnessing the magnitude of human suffering there, she second-guessed her decision, wondering if she was emotionally strong enough to deal with such tragedy.

She wasn’t the only one with reservations. Some at the University of Miami Hospital were skeptical that hospitalists could help the situation in Haiti. They questioned why she and her colleagues were included on the volunteer team, Dr. Luly-Rivera says. Ultimately, she proved herself—and the doubters—wrong.

“As internists, we were very valuable there,” says Dr. Luly-Rivera, who logged long hours treating patients and listening to their stories.

Determined to do their part to help survivors of the earthquake, hospitalists across the country joined a surge of American medical personnel in Haiti. Once there, they faced a severely traumatized populace (the Haitian government estimates more than 215,000 were killed and 300,000 injured in the quake), a crippled hospital infrastructure, and a debilitated public health system that had failed even before the earthquake to provide adequate sanitation, vaccinations, infectious-disease control, and basic primary care.

“If Haiti wasn’t chronically poor, if it hadn’t suffered for so long outside of the eye of the world community, then the devastation would have never been so great,” says Sriram Shamasunder, MD, a hospitalist and assistant clinical professor at the University of California at San Francisco’s Department of Medicine who volunteered in the relief effort with the Boston-based nonprofit group Partners in Health. “The house that crumbled is the one chronic poverty built.”

Worthy Cause, Unimaginable Conditions

Mario A. Reyes, MD, FHM, director of the Division of Pediatric Hospital Medicine at Miami Children’s Hospital, shakes his head when he thinks of the conditions in Haiti, one of the poorest nations in the Western Hemisphere. “This is how unfair the world is, that you can fly one and a half hours from a country of such plenty to a country with so much poverty,” says Dr. Reyes, who made his third trip to the island nation in as many years. “Once you go the first time, you feel a connection to the country and the people. It’s a sense of duty to help a very poor neighbor.”

This time, Dr. Reyes and colleague Andrea Maggioni, MD, organized the 75-cot pediatric unit of a 250-bed tent hospital that the University of Miami opened Jan. 21 at the airport in Port-au-Prince in collaboration with Jackson Memorial Hospital and Miami-based Project Medishare, a nonprofit organization founded by doctors from the University of Miami’s medical school in an effort to bring quality healthcare and development services to Haiti.

“There were a few general pediatricians there. They relied on us to lead the way,” Dr. Reyes says. “When I got to the pediatric tent, I saw so many kids screaming at the same time, some with bones sticking out of their body. There’s nothing more gut-wrenching than that. I spent the first night giving morphine and antibiotics like lollipops.”

Before the tent hospital—four tents in all, one for supplies, one for volunteers to sleep in, and two for patients—was set up at the airport, doctors from the University of Miami and its partnering organizations treated adult and pediatric patients at a facility in the United Nations compound in Port-au-Prince. It was utter chaos, according to Amir Jaffer, MD, FHM, chief of the Division of Hospital Medicine and an associate professor of medicine at the Miller School of Medicine. He described earthquake survivors walking around in a daze amidst the rubble, and huge numbers of people searching for food and water.

Same Work, Makeshift Surroundings

Drawing on his HM experience, Dr. Jaffer helped orchestrate the transfer of approximately 140 patients from the makeshift U.N. hospital to the university’s tent hospital a couple of miles away. He also helped lead the effort to organize patients once they arrived at the new facility, which featured a supply tent, staff sleeping tent, medical tent, and surgical tent with four operating rooms. Each patient received a medical wristband and medical record number, and had their medical care charted.

An ICU was set up for those patients who were in more serious condition, and severely ill and injured patients were airlifted to medical centers in Florida and the USNS Comfort, a U.S. Navy ship dispatched to Haiti to provide full hospital service to earthquake survivors. The tent hospital had nearly 250 patients by the end of his five-day trip, Dr. Jaffer says.

Hospitalists administered IV fluids, prescribed antibiotics and pain medication, treated infected wounds, managed patients with dehydration, gastroenteritis, and tetanus, and triaged patients. “Many patients had splints placed in the field, and we would do X-rays to confirm the diagnosis. Patients were being casted right after diagnosis,” Dr. Jaffer says.

Outside the Capital

Hospitalists volunteering with Partners in Health (PIH) were tasked with maximizing the time the surgical team could spend in the OR by assessing incoming patients, triaging cases, providing post-op care, monitoring for development of medical issues related to trauma, and ensuring that every patient was seen daily, says Jonathan Crocker, MD, a hospitalist at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center in Boston.

Dr. Crocker arrived in Haiti four days after the earthquake and was sent to Clinique Bon Saveur, a hospital in Cange, a town located two hours outside the capital on the country’s Central Plateau. The hospital is one of 10 health facilities run by Zamni Lasante, PIH’s sister organization in Haiti. Dr. Shamasunder, of UC San Francisco, arrived in the country a few days later and was stationed at St. Marc Hospital, on the west coast of the island, about 60 miles from Port-au-Prince.

At St. Marc’s, conditions were “chaotic but functioning, bare-bones but a work in progress,” as Haitian doctors began returning to work and Creole-speaking nurses from the U.S. reached the hospital, Dr. Shamasunder explains. PIH volunteers coordinated with teams from Canada and Nepal to provide the best possible medical care to patients dealing with sepsis, serious wounds, and heart failure.

Hundreds of patients, many with multiple injuries, had been streaming into Clinique Bon Saveur since the day the earthquake struck. When Dr. Crocker arrived, the hospital was overcrowded, spilling into makeshift wards that had been set up in a church and a nearby school.

“As a hospitalist, my first concern upon arrival was anticipating the likely medical complications we would encounter with a large population of patients having experienced physical trauma,” Dr. Crocker says. “These complications included, namely, DVT and PE events, compartment syndrome, rhabdomyolysis with renal failure, hyperkalemia, wound infection, and sepsis.”

After speaking with their Haitian colleagues, PIH volunteers placed all adult patients at Clinique Bon Saveur on heparin prophylaxis. They also instituted a standard antibiotic regimen for all patients with open fractures, ensured patients received tetanus shots, and made it a priority to see every patient daily in an effort to prevent compartment syndrome and complications from rhabdomyolysis.

“As we identified more patients with acute renal failure, we moved into active screening with ‘creatinine rounds,’ where we performed BUN/Cr checks on any patient suspected of having suffered major crush injuries,” says Dr. Crocker, who used a portable ultrasound to assess patients for suspected lower-extremity DVTs. “As a team, we made a daily A, B, and C priority list for patients in need of surgeries available at the hospital, and a list of patients with injuries too complex for our surgical teams requiring transfer.”

Resume Expansion

Back at the University of Miami’s tent facility, hospitalists were chipping in wherever help was needed. “I cleaned rooms, I took out the trash, I swept floors, I dispensed medicine from the pharmacy. I just did everything,” Dr. Luly-Rivera says. “You have to go with an open mind and be prepared to do things outside your own discipline.”

Volunteers must be prepared to deal with difficult patients who are under considerable stress over their present and future situations, Dr. Luly-Rivera explains. She worries about what is to come for a country that’s ill-equipped to handle so many physically disabled people. For years, there will be a pressing need for orthopedic surgeons and physical and occupational therapists, she says.

Earthquake survivors also will need help in coping with the psychological trauma they’ve endured, says Dr. Reyes, who frequently played the role of hospital clown in the tent facility’s pediatric ward—just to help the children to laugh a bit.

“These kids are fully traumatized. They don’t want to go inside buildings because they’re afraid they will collapse,” he says. “There’s a high percentage of them who lost at least one parent in the disaster. When you go to discharge them, many don’t have a home to go to. You just feel tremendous sadness.”

Emotional Connection

The sorrow intensified when Dr. Reyes returned to work after returning from his trip to Haiti. “You can barely eat because you have a knot in your throat,” he says.

Upon her return to Miami, Dr. Luly-Rivera spent almost every spare minute watching news coverage on television and reading about the relief effort online. It was difficult for her to concentrate when working, she admits.

“It wasn’t that I felt the patients here didn’t need me,” she says. “It’s just that my mind was still in Haiti and thinking about my patients there. I had to let it go.”

Feelings of sadness and grief are common reactions to witnessing acute injuries and loss of life, says Dr. Jaffer. Some people react by refusing to leave until the work is done, or returning to the relief effort before they are ready.

—Mario Reyes, MD, FHM, director, Division of Pediatric Hospital Medicine, Miami Children’s Hospital

“Medical volunteerism shows you there is life beyond what you do in your workplace. It allows you to bridge the gap between your job and people who are less fortunate. The experience can be invigorating, but it can also be stress-inducing and lead to depression,” Dr. Jaffer says. “It’s always good to have someone you pair up with to monitor your stress level.”

After taking time to decompress, Drs. Luly-Rivera and Reyes plan to return to Haiti. They hope healthcare workers from all parts of the U.S. will continue to volunteer in the months ahead. Haiti’s weighty issues demand that non-governmental organizations (NGOs) working in the country stay and better coordinate their efforts, Dr. Reyes says.

“Ultimately, it is going to be important for any group present in Haiti to work to support the Haitian medical community,” Dr. Crocker adds. “The long-term recovery and rehabilitation of so many thousands of patients will be possible only through a robust, functional, public healthcare delivery system.”

It remains to be seen how many NGOs and volunteers will still be in Haiti a few months from now, the hospitalists said.

It’s always a concern that the attention of the global community may shift away from Haiti when the next calamity strikes in another part of the world, Dr. Jaffer notes. If the focus stays on Haiti as it rebuilds, then possibly some good will come out of the earthquake, Dr. Luly-Rivera says. But if NGOs begin to leave in the short term, the quake would only be the latest setback for one of the world’s poorest and most underdeveloped countries.

Even if the latter were to happen, Dr. Luly-Rivera still says she and other volunteers make a difference. “I’m still glad I went,” she says. “The people were so thankful.”

“You see the best of the American people there,” Dr. Reyes adds. “It’s encouraging and uplifting. It brings back faith in the medical profession and faith in people.” TH

Lisa Ryan is a freelance writer based in New Jersey.

The patient had a number of wounds to her battered body, but her most pressing question was how to stanch the flow of milk from her breasts, recalls Lisa Luly-Rivera, MD. The woman was in an endless line of people Dr. Luly-Rivera, a hospitalist at the University of Miami (Fla.) Hospital, cared for during a five-day medical volunteer mission to Haiti in the aftermath of the January earthquake that devastated much of the country.

“She had lost everything, including her seven-month-old baby, who she watched die in the earthquake. She was still lactating and wanted to know how to get the milk to stop,” Dr. Luly-Rivera says. “I heard story after story after story like this. For me, it was emotionally jarring.”

A Haitian-American who has extended-family members in Haiti who survived the Jan. 12 earthquake, Dr. Luly-Rivera leaped at the chance to participate in the medical relief effort organized by the university’s Miller School of Medicine in conjunction with Project Medishare and Jackson Memorial Hospital in Miami. But soon after arriving in the Haitian capital of Port-au-Prince on Jan. 20 and witnessing the magnitude of human suffering there, she second-guessed her decision, wondering if she was emotionally strong enough to deal with such tragedy.

She wasn’t the only one with reservations. Some at the University of Miami Hospital were skeptical that hospitalists could help the situation in Haiti. They questioned why she and her colleagues were included on the volunteer team, Dr. Luly-Rivera says. Ultimately, she proved herself—and the doubters—wrong.

“As internists, we were very valuable there,” says Dr. Luly-Rivera, who logged long hours treating patients and listening to their stories.

Determined to do their part to help survivors of the earthquake, hospitalists across the country joined a surge of American medical personnel in Haiti. Once there, they faced a severely traumatized populace (the Haitian government estimates more than 215,000 were killed and 300,000 injured in the quake), a crippled hospital infrastructure, and a debilitated public health system that had failed even before the earthquake to provide adequate sanitation, vaccinations, infectious-disease control, and basic primary care.

“If Haiti wasn’t chronically poor, if it hadn’t suffered for so long outside of the eye of the world community, then the devastation would have never been so great,” says Sriram Shamasunder, MD, a hospitalist and assistant clinical professor at the University of California at San Francisco’s Department of Medicine who volunteered in the relief effort with the Boston-based nonprofit group Partners in Health. “The house that crumbled is the one chronic poverty built.”

Worthy Cause, Unimaginable Conditions

Mario A. Reyes, MD, FHM, director of the Division of Pediatric Hospital Medicine at Miami Children’s Hospital, shakes his head when he thinks of the conditions in Haiti, one of the poorest nations in the Western Hemisphere. “This is how unfair the world is, that you can fly one and a half hours from a country of such plenty to a country with so much poverty,” says Dr. Reyes, who made his third trip to the island nation in as many years. “Once you go the first time, you feel a connection to the country and the people. It’s a sense of duty to help a very poor neighbor.”

This time, Dr. Reyes and colleague Andrea Maggioni, MD, organized the 75-cot pediatric unit of a 250-bed tent hospital that the University of Miami opened Jan. 21 at the airport in Port-au-Prince in collaboration with Jackson Memorial Hospital and Miami-based Project Medishare, a nonprofit organization founded by doctors from the University of Miami’s medical school in an effort to bring quality healthcare and development services to Haiti.

“There were a few general pediatricians there. They relied on us to lead the way,” Dr. Reyes says. “When I got to the pediatric tent, I saw so many kids screaming at the same time, some with bones sticking out of their body. There’s nothing more gut-wrenching than that. I spent the first night giving morphine and antibiotics like lollipops.”

Before the tent hospital—four tents in all, one for supplies, one for volunteers to sleep in, and two for patients—was set up at the airport, doctors from the University of Miami and its partnering organizations treated adult and pediatric patients at a facility in the United Nations compound in Port-au-Prince. It was utter chaos, according to Amir Jaffer, MD, FHM, chief of the Division of Hospital Medicine and an associate professor of medicine at the Miller School of Medicine. He described earthquake survivors walking around in a daze amidst the rubble, and huge numbers of people searching for food and water.

Same Work, Makeshift Surroundings

Drawing on his HM experience, Dr. Jaffer helped orchestrate the transfer of approximately 140 patients from the makeshift U.N. hospital to the university’s tent hospital a couple of miles away. He also helped lead the effort to organize patients once they arrived at the new facility, which featured a supply tent, staff sleeping tent, medical tent, and surgical tent with four operating rooms. Each patient received a medical wristband and medical record number, and had their medical care charted.

An ICU was set up for those patients who were in more serious condition, and severely ill and injured patients were airlifted to medical centers in Florida and the USNS Comfort, a U.S. Navy ship dispatched to Haiti to provide full hospital service to earthquake survivors. The tent hospital had nearly 250 patients by the end of his five-day trip, Dr. Jaffer says.

Hospitalists administered IV fluids, prescribed antibiotics and pain medication, treated infected wounds, managed patients with dehydration, gastroenteritis, and tetanus, and triaged patients. “Many patients had splints placed in the field, and we would do X-rays to confirm the diagnosis. Patients were being casted right after diagnosis,” Dr. Jaffer says.

Outside the Capital

Hospitalists volunteering with Partners in Health (PIH) were tasked with maximizing the time the surgical team could spend in the OR by assessing incoming patients, triaging cases, providing post-op care, monitoring for development of medical issues related to trauma, and ensuring that every patient was seen daily, says Jonathan Crocker, MD, a hospitalist at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center in Boston.

Dr. Crocker arrived in Haiti four days after the earthquake and was sent to Clinique Bon Saveur, a hospital in Cange, a town located two hours outside the capital on the country’s Central Plateau. The hospital is one of 10 health facilities run by Zamni Lasante, PIH’s sister organization in Haiti. Dr. Shamasunder, of UC San Francisco, arrived in the country a few days later and was stationed at St. Marc Hospital, on the west coast of the island, about 60 miles from Port-au-Prince.

At St. Marc’s, conditions were “chaotic but functioning, bare-bones but a work in progress,” as Haitian doctors began returning to work and Creole-speaking nurses from the U.S. reached the hospital, Dr. Shamasunder explains. PIH volunteers coordinated with teams from Canada and Nepal to provide the best possible medical care to patients dealing with sepsis, serious wounds, and heart failure.

Hundreds of patients, many with multiple injuries, had been streaming into Clinique Bon Saveur since the day the earthquake struck. When Dr. Crocker arrived, the hospital was overcrowded, spilling into makeshift wards that had been set up in a church and a nearby school.

“As a hospitalist, my first concern upon arrival was anticipating the likely medical complications we would encounter with a large population of patients having experienced physical trauma,” Dr. Crocker says. “These complications included, namely, DVT and PE events, compartment syndrome, rhabdomyolysis with renal failure, hyperkalemia, wound infection, and sepsis.”

After speaking with their Haitian colleagues, PIH volunteers placed all adult patients at Clinique Bon Saveur on heparin prophylaxis. They also instituted a standard antibiotic regimen for all patients with open fractures, ensured patients received tetanus shots, and made it a priority to see every patient daily in an effort to prevent compartment syndrome and complications from rhabdomyolysis.

“As we identified more patients with acute renal failure, we moved into active screening with ‘creatinine rounds,’ where we performed BUN/Cr checks on any patient suspected of having suffered major crush injuries,” says Dr. Crocker, who used a portable ultrasound to assess patients for suspected lower-extremity DVTs. “As a team, we made a daily A, B, and C priority list for patients in need of surgeries available at the hospital, and a list of patients with injuries too complex for our surgical teams requiring transfer.”

Resume Expansion

Back at the University of Miami’s tent facility, hospitalists were chipping in wherever help was needed. “I cleaned rooms, I took out the trash, I swept floors, I dispensed medicine from the pharmacy. I just did everything,” Dr. Luly-Rivera says. “You have to go with an open mind and be prepared to do things outside your own discipline.”

Volunteers must be prepared to deal with difficult patients who are under considerable stress over their present and future situations, Dr. Luly-Rivera explains. She worries about what is to come for a country that’s ill-equipped to handle so many physically disabled people. For years, there will be a pressing need for orthopedic surgeons and physical and occupational therapists, she says.

Earthquake survivors also will need help in coping with the psychological trauma they’ve endured, says Dr. Reyes, who frequently played the role of hospital clown in the tent facility’s pediatric ward—just to help the children to laugh a bit.

“These kids are fully traumatized. They don’t want to go inside buildings because they’re afraid they will collapse,” he says. “There’s a high percentage of them who lost at least one parent in the disaster. When you go to discharge them, many don’t have a home to go to. You just feel tremendous sadness.”

Emotional Connection

The sorrow intensified when Dr. Reyes returned to work after returning from his trip to Haiti. “You can barely eat because you have a knot in your throat,” he says.

Upon her return to Miami, Dr. Luly-Rivera spent almost every spare minute watching news coverage on television and reading about the relief effort online. It was difficult for her to concentrate when working, she admits.

“It wasn’t that I felt the patients here didn’t need me,” she says. “It’s just that my mind was still in Haiti and thinking about my patients there. I had to let it go.”

Feelings of sadness and grief are common reactions to witnessing acute injuries and loss of life, says Dr. Jaffer. Some people react by refusing to leave until the work is done, or returning to the relief effort before they are ready.

—Mario Reyes, MD, FHM, director, Division of Pediatric Hospital Medicine, Miami Children’s Hospital

“Medical volunteerism shows you there is life beyond what you do in your workplace. It allows you to bridge the gap between your job and people who are less fortunate. The experience can be invigorating, but it can also be stress-inducing and lead to depression,” Dr. Jaffer says. “It’s always good to have someone you pair up with to monitor your stress level.”

After taking time to decompress, Drs. Luly-Rivera and Reyes plan to return to Haiti. They hope healthcare workers from all parts of the U.S. will continue to volunteer in the months ahead. Haiti’s weighty issues demand that non-governmental organizations (NGOs) working in the country stay and better coordinate their efforts, Dr. Reyes says.

“Ultimately, it is going to be important for any group present in Haiti to work to support the Haitian medical community,” Dr. Crocker adds. “The long-term recovery and rehabilitation of so many thousands of patients will be possible only through a robust, functional, public healthcare delivery system.”

It remains to be seen how many NGOs and volunteers will still be in Haiti a few months from now, the hospitalists said.

It’s always a concern that the attention of the global community may shift away from Haiti when the next calamity strikes in another part of the world, Dr. Jaffer notes. If the focus stays on Haiti as it rebuilds, then possibly some good will come out of the earthquake, Dr. Luly-Rivera says. But if NGOs begin to leave in the short term, the quake would only be the latest setback for one of the world’s poorest and most underdeveloped countries.

Even if the latter were to happen, Dr. Luly-Rivera still says she and other volunteers make a difference. “I’m still glad I went,” she says. “The people were so thankful.”

“You see the best of the American people there,” Dr. Reyes adds. “It’s encouraging and uplifting. It brings back faith in the medical profession and faith in people.” TH

Lisa Ryan is a freelance writer based in New Jersey.

Dress for Success

The oft-quoted Hippocrates once stated that physicians should be “clean in person, well-dressed, and anointed with sweet-smelling unguents.” So are hospitalists heeding the father of modern medicine’s counsel about physician appearance in the 21st century?

According to an informal survey about workplace attire conducted recently at the-hospitalist.org, a majority of hospitalists are wearing professional apparel while on the job.

In response to the question "What do you typically wear to work?" more than half (54%) of voters said they dress business casual, commonly defined as a dress shirt, slacks, belt, shoes, and socks for men, and a dress shirt, reasonable-length skirt or full-length trousers, shoes, and hosiery for women. Another 13% stated they wear a suit to work. Meanwhile, the other third of respondents said they dress in scrubs (22%), khakis and polo shirts (10%), and jeans and T-shirts (2%).

Most hospitalists at IPC: The Hospitalist Co., a national physician group practice based in North Hollywood, Calif., opt for business-casual dress, says Rafael Barretto, DO, the company's associate medical director for the Michigan region. While IPC does not have a strict dress code, it does give guidelines to its hospitalists and encourages them to avoid wearing sandals, tennis shoes, and jeans to work.

"IPC considers patients' attitudes on physician appearance to be very important. We want our patients to trust that we're going to do the best we can to take care of them," says Dr. Barretto, who cites several research studies, including a report published in the November 2005 issue of The American Journal of Medicine, that found patients favor physicians in professional attire.

"Fortunately or unfortunately, perception is reality and hospitalists need to be concerned with how a patient or a patient's family perceives them," says Chris Frost, MD, senior vice president of hospital medicine for TeamHealth Hospital Medicine, a national hospitalist management company in Knoxville, Tenn. TeamHealth has a company-wide policy that discourages its physicians from engaging in unprofessional dress.

"Hospitalists only have one chance to make a first impression. If a hospitalist is dressed poorly, that could overshadow any good patient care he or she provides," Dr. Frost says.

The oft-quoted Hippocrates once stated that physicians should be “clean in person, well-dressed, and anointed with sweet-smelling unguents.” So are hospitalists heeding the father of modern medicine’s counsel about physician appearance in the 21st century?

According to an informal survey about workplace attire conducted recently at the-hospitalist.org, a majority of hospitalists are wearing professional apparel while on the job.

In response to the question "What do you typically wear to work?" more than half (54%) of voters said they dress business casual, commonly defined as a dress shirt, slacks, belt, shoes, and socks for men, and a dress shirt, reasonable-length skirt or full-length trousers, shoes, and hosiery for women. Another 13% stated they wear a suit to work. Meanwhile, the other third of respondents said they dress in scrubs (22%), khakis and polo shirts (10%), and jeans and T-shirts (2%).

Most hospitalists at IPC: The Hospitalist Co., a national physician group practice based in North Hollywood, Calif., opt for business-casual dress, says Rafael Barretto, DO, the company's associate medical director for the Michigan region. While IPC does not have a strict dress code, it does give guidelines to its hospitalists and encourages them to avoid wearing sandals, tennis shoes, and jeans to work.

"IPC considers patients' attitudes on physician appearance to be very important. We want our patients to trust that we're going to do the best we can to take care of them," says Dr. Barretto, who cites several research studies, including a report published in the November 2005 issue of The American Journal of Medicine, that found patients favor physicians in professional attire.

"Fortunately or unfortunately, perception is reality and hospitalists need to be concerned with how a patient or a patient's family perceives them," says Chris Frost, MD, senior vice president of hospital medicine for TeamHealth Hospital Medicine, a national hospitalist management company in Knoxville, Tenn. TeamHealth has a company-wide policy that discourages its physicians from engaging in unprofessional dress.

"Hospitalists only have one chance to make a first impression. If a hospitalist is dressed poorly, that could overshadow any good patient care he or she provides," Dr. Frost says.

The oft-quoted Hippocrates once stated that physicians should be “clean in person, well-dressed, and anointed with sweet-smelling unguents.” So are hospitalists heeding the father of modern medicine’s counsel about physician appearance in the 21st century?

According to an informal survey about workplace attire conducted recently at the-hospitalist.org, a majority of hospitalists are wearing professional apparel while on the job.

In response to the question "What do you typically wear to work?" more than half (54%) of voters said they dress business casual, commonly defined as a dress shirt, slacks, belt, shoes, and socks for men, and a dress shirt, reasonable-length skirt or full-length trousers, shoes, and hosiery for women. Another 13% stated they wear a suit to work. Meanwhile, the other third of respondents said they dress in scrubs (22%), khakis and polo shirts (10%), and jeans and T-shirts (2%).

Most hospitalists at IPC: The Hospitalist Co., a national physician group practice based in North Hollywood, Calif., opt for business-casual dress, says Rafael Barretto, DO, the company's associate medical director for the Michigan region. While IPC does not have a strict dress code, it does give guidelines to its hospitalists and encourages them to avoid wearing sandals, tennis shoes, and jeans to work.

"IPC considers patients' attitudes on physician appearance to be very important. We want our patients to trust that we're going to do the best we can to take care of them," says Dr. Barretto, who cites several research studies, including a report published in the November 2005 issue of The American Journal of Medicine, that found patients favor physicians in professional attire.

"Fortunately or unfortunately, perception is reality and hospitalists need to be concerned with how a patient or a patient's family perceives them," says Chris Frost, MD, senior vice president of hospital medicine for TeamHealth Hospital Medicine, a national hospitalist management company in Knoxville, Tenn. TeamHealth has a company-wide policy that discourages its physicians from engaging in unprofessional dress.

"Hospitalists only have one chance to make a first impression. If a hospitalist is dressed poorly, that could overshadow any good patient care he or she provides," Dr. Frost says.

Smooth Moves

Accepting a job in a new city, state, or country can be invigorating for professional and personal reasons, but making the actual move often is stressful, irritating, and more than a little overwhelming. Multiple factors are involved when you transition from one community to another.

For hospitalists relocating for a new job, the good news is it’s almost a given you will receive financial assistance and more than a little guidance to make the move as smooth and hassle-free as possible, says Tommy Bohannon, vice president of hospital-based recruiting for Merritt Hawkins & Associates, a recruitment firm that specializes in the placement of permanent physicians. Ninety-eight percent of physician and certified registered nurse anesthetists are provided relocation assistance, according to a Merritt Hawkins review of recruiting incentives conducted from April 2008 to March 2009. The Irving, Texas-based firm found that the average relocation allowance is $10,427, the highest amount offered since it began tracking recruiting incentives in 2005.

The Upper Hand: HM Still in Demand

While the struggling economy has put a damper on relocation allowances in other professions, it has not had a similar effect on HM, says Cheryl Slack, vice president of human resources for Cogent Healthcare, a Brentwood, Tenn.-based company that partners with hospitals to build and manage hospitalist programs. Hospitalists have become harder and harder to recruit as demand for their services continues to far outpace their supply, she says.

“Relocation assistance is the nature of the beast,” says Slack, whose company typically covers a hospitalist’s move from Point A to Point B, storage fees for a few months, and sometimes travel costs to and from their former home to tie up loose ends. “We see it as the cost of doing business.”

Because most relocation allowances are not tied to a time or service commitment, hospitalists can use the money to facilitate their move without the worry of having to pay some of it back if the job doesn’t work out. They can get the most mileage out of the assistance by comparison shopping (see “Internet Resources for Relocations,” right) or using companies that have a relationship with their recruiter or employer. “We actually have an in-house relocation team and a preferred-rate contract with a national moving company,” Bohannon says. “The vast majority of our candidates work with the in-house team. We help them with the physical move itself. We assist them in taking an inventory of their belongings to get an idea of how much it will cost to move, and we get the moving company in contact with them.”

Temporary vs. Permanent Decisions

Hospitalists might want to consider renting or taking advantage of temporary housing, if offered by the new employer, in order to get acclimated with the new community and its neighborhoods, says Christian Rutherford, president and CEO of Kendall & Davis, a St. Louis-based physician recruitment firm. In the current housing market, renting or using temporary housing might be the best option for hospitalists who are still trying to sell their last home.

When hospitalists are ready to buy a home in their new community, they should check with people at their new job or their recruiter to get names of real estate agents who have considerable insight into the community and local property values. “When we first discuss an opportunity with a candidate, we will pass along pretty detailed information about neighborhoods, schools, housing costs, churches, local clubs that cater to their interests, and hobbies,” Bohannon says. “The market has changed to where the candidate is interviewing the opportunity. We’re pretty hands-on to make sure they have access to the information they need to make a good decision.”

Community Comes First

—Tommy Bohannon, vice president of hospital-based recruiting, Merritt Hawkins & Associates, Irving, Texas

For most job candidates, 50% of the “sale”—the decision to relocate—is the community in which they will work and live, says Mark Dotson, Cogent Healthcare’s senior director of recruitment. Candidates want to know about the neighborhoods, school systems, and cost of living, and nearby entertainment, cultural, and social amenities. Even though a lot of information is available on the Internet, it is not always dependable. Recruiters and potential employers often provide comprehensive community information packets for hospitalists; many organize a community tour while hospitalists are in town for their on-site interview. Some employers and recruiters schedule meetings with real estate agents, school administrators, even Chamber of Commerce representatives.

“I’ve talked to hospitals about providers’ spouses and where they might be able to find work. It’s all part of the recruitment process and determining what the individual provider’s needs are,” says Mimi Hagan, regional director of hospitalist accounts for Hospital Physician Partners of Fort Lauderdale, Fla., a medical management company that partners with hospitals to build emergency and hospitalist practices. “The last thing we want is for a provider to walk into the hospital thinking this isn’t the right fit for them. It’s not good for the provider, it’s not good for the hospital, and it’s not good for us.”

Hagan and Rutherford advise hospitalists who are seriously contemplating relocating and have families to bring their partners with them for the on-site interview. They might want to consider making another trip to their new community with the children in tow. “Relocating to a different area is a really big cultural change. Candidates have to make sure their spouse is as excited about the change as they are,” Rutherford says. “Don’t ever underestimate how much of a strain this can be on the kids and the spouse.” TH

Lisa Ryan is a freelance writer based in New Jersey.

Accepting a job in a new city, state, or country can be invigorating for professional and personal reasons, but making the actual move often is stressful, irritating, and more than a little overwhelming. Multiple factors are involved when you transition from one community to another.

For hospitalists relocating for a new job, the good news is it’s almost a given you will receive financial assistance and more than a little guidance to make the move as smooth and hassle-free as possible, says Tommy Bohannon, vice president of hospital-based recruiting for Merritt Hawkins & Associates, a recruitment firm that specializes in the placement of permanent physicians. Ninety-eight percent of physician and certified registered nurse anesthetists are provided relocation assistance, according to a Merritt Hawkins review of recruiting incentives conducted from April 2008 to March 2009. The Irving, Texas-based firm found that the average relocation allowance is $10,427, the highest amount offered since it began tracking recruiting incentives in 2005.

The Upper Hand: HM Still in Demand

While the struggling economy has put a damper on relocation allowances in other professions, it has not had a similar effect on HM, says Cheryl Slack, vice president of human resources for Cogent Healthcare, a Brentwood, Tenn.-based company that partners with hospitals to build and manage hospitalist programs. Hospitalists have become harder and harder to recruit as demand for their services continues to far outpace their supply, she says.

“Relocation assistance is the nature of the beast,” says Slack, whose company typically covers a hospitalist’s move from Point A to Point B, storage fees for a few months, and sometimes travel costs to and from their former home to tie up loose ends. “We see it as the cost of doing business.”

Because most relocation allowances are not tied to a time or service commitment, hospitalists can use the money to facilitate their move without the worry of having to pay some of it back if the job doesn’t work out. They can get the most mileage out of the assistance by comparison shopping (see “Internet Resources for Relocations,” right) or using companies that have a relationship with their recruiter or employer. “We actually have an in-house relocation team and a preferred-rate contract with a national moving company,” Bohannon says. “The vast majority of our candidates work with the in-house team. We help them with the physical move itself. We assist them in taking an inventory of their belongings to get an idea of how much it will cost to move, and we get the moving company in contact with them.”

Temporary vs. Permanent Decisions

Hospitalists might want to consider renting or taking advantage of temporary housing, if offered by the new employer, in order to get acclimated with the new community and its neighborhoods, says Christian Rutherford, president and CEO of Kendall & Davis, a St. Louis-based physician recruitment firm. In the current housing market, renting or using temporary housing might be the best option for hospitalists who are still trying to sell their last home.

When hospitalists are ready to buy a home in their new community, they should check with people at their new job or their recruiter to get names of real estate agents who have considerable insight into the community and local property values. “When we first discuss an opportunity with a candidate, we will pass along pretty detailed information about neighborhoods, schools, housing costs, churches, local clubs that cater to their interests, and hobbies,” Bohannon says. “The market has changed to where the candidate is interviewing the opportunity. We’re pretty hands-on to make sure they have access to the information they need to make a good decision.”

Community Comes First

—Tommy Bohannon, vice president of hospital-based recruiting, Merritt Hawkins & Associates, Irving, Texas

For most job candidates, 50% of the “sale”—the decision to relocate—is the community in which they will work and live, says Mark Dotson, Cogent Healthcare’s senior director of recruitment. Candidates want to know about the neighborhoods, school systems, and cost of living, and nearby entertainment, cultural, and social amenities. Even though a lot of information is available on the Internet, it is not always dependable. Recruiters and potential employers often provide comprehensive community information packets for hospitalists; many organize a community tour while hospitalists are in town for their on-site interview. Some employers and recruiters schedule meetings with real estate agents, school administrators, even Chamber of Commerce representatives.

“I’ve talked to hospitals about providers’ spouses and where they might be able to find work. It’s all part of the recruitment process and determining what the individual provider’s needs are,” says Mimi Hagan, regional director of hospitalist accounts for Hospital Physician Partners of Fort Lauderdale, Fla., a medical management company that partners with hospitals to build emergency and hospitalist practices. “The last thing we want is for a provider to walk into the hospital thinking this isn’t the right fit for them. It’s not good for the provider, it’s not good for the hospital, and it’s not good for us.”

Hagan and Rutherford advise hospitalists who are seriously contemplating relocating and have families to bring their partners with them for the on-site interview. They might want to consider making another trip to their new community with the children in tow. “Relocating to a different area is a really big cultural change. Candidates have to make sure their spouse is as excited about the change as they are,” Rutherford says. “Don’t ever underestimate how much of a strain this can be on the kids and the spouse.” TH

Lisa Ryan is a freelance writer based in New Jersey.

Accepting a job in a new city, state, or country can be invigorating for professional and personal reasons, but making the actual move often is stressful, irritating, and more than a little overwhelming. Multiple factors are involved when you transition from one community to another.

For hospitalists relocating for a new job, the good news is it’s almost a given you will receive financial assistance and more than a little guidance to make the move as smooth and hassle-free as possible, says Tommy Bohannon, vice president of hospital-based recruiting for Merritt Hawkins & Associates, a recruitment firm that specializes in the placement of permanent physicians. Ninety-eight percent of physician and certified registered nurse anesthetists are provided relocation assistance, according to a Merritt Hawkins review of recruiting incentives conducted from April 2008 to March 2009. The Irving, Texas-based firm found that the average relocation allowance is $10,427, the highest amount offered since it began tracking recruiting incentives in 2005.

The Upper Hand: HM Still in Demand

While the struggling economy has put a damper on relocation allowances in other professions, it has not had a similar effect on HM, says Cheryl Slack, vice president of human resources for Cogent Healthcare, a Brentwood, Tenn.-based company that partners with hospitals to build and manage hospitalist programs. Hospitalists have become harder and harder to recruit as demand for their services continues to far outpace their supply, she says.

“Relocation assistance is the nature of the beast,” says Slack, whose company typically covers a hospitalist’s move from Point A to Point B, storage fees for a few months, and sometimes travel costs to and from their former home to tie up loose ends. “We see it as the cost of doing business.”

Because most relocation allowances are not tied to a time or service commitment, hospitalists can use the money to facilitate their move without the worry of having to pay some of it back if the job doesn’t work out. They can get the most mileage out of the assistance by comparison shopping (see “Internet Resources for Relocations,” right) or using companies that have a relationship with their recruiter or employer. “We actually have an in-house relocation team and a preferred-rate contract with a national moving company,” Bohannon says. “The vast majority of our candidates work with the in-house team. We help them with the physical move itself. We assist them in taking an inventory of their belongings to get an idea of how much it will cost to move, and we get the moving company in contact with them.”

Temporary vs. Permanent Decisions

Hospitalists might want to consider renting or taking advantage of temporary housing, if offered by the new employer, in order to get acclimated with the new community and its neighborhoods, says Christian Rutherford, president and CEO of Kendall & Davis, a St. Louis-based physician recruitment firm. In the current housing market, renting or using temporary housing might be the best option for hospitalists who are still trying to sell their last home.

When hospitalists are ready to buy a home in their new community, they should check with people at their new job or their recruiter to get names of real estate agents who have considerable insight into the community and local property values. “When we first discuss an opportunity with a candidate, we will pass along pretty detailed information about neighborhoods, schools, housing costs, churches, local clubs that cater to their interests, and hobbies,” Bohannon says. “The market has changed to where the candidate is interviewing the opportunity. We’re pretty hands-on to make sure they have access to the information they need to make a good decision.”

Community Comes First

—Tommy Bohannon, vice president of hospital-based recruiting, Merritt Hawkins & Associates, Irving, Texas

For most job candidates, 50% of the “sale”—the decision to relocate—is the community in which they will work and live, says Mark Dotson, Cogent Healthcare’s senior director of recruitment. Candidates want to know about the neighborhoods, school systems, and cost of living, and nearby entertainment, cultural, and social amenities. Even though a lot of information is available on the Internet, it is not always dependable. Recruiters and potential employers often provide comprehensive community information packets for hospitalists; many organize a community tour while hospitalists are in town for their on-site interview. Some employers and recruiters schedule meetings with real estate agents, school administrators, even Chamber of Commerce representatives.

“I’ve talked to hospitals about providers’ spouses and where they might be able to find work. It’s all part of the recruitment process and determining what the individual provider’s needs are,” says Mimi Hagan, regional director of hospitalist accounts for Hospital Physician Partners of Fort Lauderdale, Fla., a medical management company that partners with hospitals to build emergency and hospitalist practices. “The last thing we want is for a provider to walk into the hospital thinking this isn’t the right fit for them. It’s not good for the provider, it’s not good for the hospital, and it’s not good for us.”

Hagan and Rutherford advise hospitalists who are seriously contemplating relocating and have families to bring their partners with them for the on-site interview. They might want to consider making another trip to their new community with the children in tow. “Relocating to a different area is a really big cultural change. Candidates have to make sure their spouse is as excited about the change as they are,” Rutherford says. “Don’t ever underestimate how much of a strain this can be on the kids and the spouse.” TH

Lisa Ryan is a freelance writer based in New Jersey.

Avoid Social Networking Pitfalls

Although Web sites like Facebook, Linked In, and Ning are touted as valuable tools for social and professional networking, if users aren’t careful, career-related catastrophes can occur. It bears repeating that no online activity is anonymous, especially with more and more healthcare employers and recruiters visiting these sites to learn about job candidates, says Roberta Renaldy, a senior staffing specialist at Northwestern Memorial Hospital in Chicago.

“They’re becoming your resume before your resume,” Renaldy says of social networking sites.

To keep career opportunities open, hospitalists should avoid dishing out “digital dirt”—aka put-downs—about other people, she says. Vulgarity, unsavory photos, incorrect spelling and grammar, angry online disputes, and dispensing medical advice also are taboo. Even strong points of view on controversial issues can run hospitalists the risk of getting passed over for a job or promotion.

“Someone might be willing to take this risk, but I encourage people to really think before they express their opinions,” Renaldy says.

On the flip side, hospitalists should create a personal brand that’s compelling and consistent across their social networking profiles, says E. Chandlee Bryan, a certified career coach at the firm Best Fit Forward in New York City. Be accurate about expertise and keep visitors interested by providing constant career updates, she says. Always thank network contacts for the slightest bit of advice, and don’t hesitate to offer others help, Bryan suggests.

Renaldy emphasizes the old-fashioned approach. “Using the Internet is a way to spark a networking relationship, but many times it doesn’t develop the relationship,” she says. “Nothing replaces face-to-face contact in furthering your professional career.”

Although Web sites like Facebook, Linked In, and Ning are touted as valuable tools for social and professional networking, if users aren’t careful, career-related catastrophes can occur. It bears repeating that no online activity is anonymous, especially with more and more healthcare employers and recruiters visiting these sites to learn about job candidates, says Roberta Renaldy, a senior staffing specialist at Northwestern Memorial Hospital in Chicago.

“They’re becoming your resume before your resume,” Renaldy says of social networking sites.

To keep career opportunities open, hospitalists should avoid dishing out “digital dirt”—aka put-downs—about other people, she says. Vulgarity, unsavory photos, incorrect spelling and grammar, angry online disputes, and dispensing medical advice also are taboo. Even strong points of view on controversial issues can run hospitalists the risk of getting passed over for a job or promotion.

“Someone might be willing to take this risk, but I encourage people to really think before they express their opinions,” Renaldy says.

On the flip side, hospitalists should create a personal brand that’s compelling and consistent across their social networking profiles, says E. Chandlee Bryan, a certified career coach at the firm Best Fit Forward in New York City. Be accurate about expertise and keep visitors interested by providing constant career updates, she says. Always thank network contacts for the slightest bit of advice, and don’t hesitate to offer others help, Bryan suggests.

Renaldy emphasizes the old-fashioned approach. “Using the Internet is a way to spark a networking relationship, but many times it doesn’t develop the relationship,” she says. “Nothing replaces face-to-face contact in furthering your professional career.”

Although Web sites like Facebook, Linked In, and Ning are touted as valuable tools for social and professional networking, if users aren’t careful, career-related catastrophes can occur. It bears repeating that no online activity is anonymous, especially with more and more healthcare employers and recruiters visiting these sites to learn about job candidates, says Roberta Renaldy, a senior staffing specialist at Northwestern Memorial Hospital in Chicago.

“They’re becoming your resume before your resume,” Renaldy says of social networking sites.

To keep career opportunities open, hospitalists should avoid dishing out “digital dirt”—aka put-downs—about other people, she says. Vulgarity, unsavory photos, incorrect spelling and grammar, angry online disputes, and dispensing medical advice also are taboo. Even strong points of view on controversial issues can run hospitalists the risk of getting passed over for a job or promotion.

“Someone might be willing to take this risk, but I encourage people to really think before they express their opinions,” Renaldy says.

On the flip side, hospitalists should create a personal brand that’s compelling and consistent across their social networking profiles, says E. Chandlee Bryan, a certified career coach at the firm Best Fit Forward in New York City. Be accurate about expertise and keep visitors interested by providing constant career updates, she says. Always thank network contacts for the slightest bit of advice, and don’t hesitate to offer others help, Bryan suggests.

Renaldy emphasizes the old-fashioned approach. “Using the Internet is a way to spark a networking relationship, but many times it doesn’t develop the relationship,” she says. “Nothing replaces face-to-face contact in furthering your professional career.”

All Grown Up

There are times when Dan Hale, MD, FAAP, wishes he had more standardized tools to use when he leads a team of four full-time and four part-time pediatric hospitalists at Central Maine Medical Center (CMMC) in Lewiston. Even after five years at the community hospital, the pediatric HM program still is searching for the best way to hand off patients who are leaving the hospital to their primary-care physicians (PCPs).

It also would be beneficial to have markers against which CMMC could compare itself with similarly sized pediatric HM programs around the country, says Dr. Hale, chief of pediatrics at the medical center. CMMC, which averages about 4,000 patient encounters per year, is one of three hospitals in the state with a pediatric HM program. “It would be nice to see progress being made in these areas,” he says.

Dr. Hale might not have to wait long to see his wishes granted. More than 20 pediatric hospitalists from across the nation met in Chicago earlier this year, intent on developing a strategic framework for pediatric HM (PHM). About 10% of the 30,000-plus hospitalists practicing in the U.S. focus exclusively on pediatrics, according to SHM’s 2007-2008 “Bi-Annual Survey on the State of the Hospital Medicine Movement.” Like the hospitalist movement in general, PHM is growing in number and influence as pediatric hospitalists take on leadership roles and develop working relationships with hospital administrators. The time has come to clearly define the discipline for other physicians, as well as patients and their families, and leverage PHM’s growth and usefulness to improve medical care for children, says Erin Stucky, MD, FHM, a pediatric hospitalist at Rady Children’s Hospital and Health Center in San Diego.

—Jennifer Daru, MD, FAAP, FHM, chief, division of pediatric hospital medicine, California Pacific Medical Center, San Francisco

“It’s a little bit of pie in the sky, a little bit of rose-colored glasses, but it’s good to aim high,” she says.

Some PHM leaders think the subspecialty has advanced enough in recent years to apply its collective knowledge and influence on a broader stage. “We have gone through our adolescence, and now we are a big community,” says Jack Percelay, MD, MPH, FHM, a pediatric hospitalist at Saint Barnabas Medical Center in New York City and SHM board member. “We’re active at almost all the major medical centers and we need to step up to the plate. We need to start the hard work of bringing our vision to fruition.”

Definition and Strategy

Drs. Stucky and Percelay attended the Pediatric Hospital Medicine (PHM) Strategic Planning Roundtable and serve on the roundtable’s planning committee. SHM, the Academic Pediatric Association (APA), and the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) sponsored the gathering, which included young and veteran pediatric hospitalists, clinicians, researchers, and hospitalists from academic, children’s, and community hospitals. The net was cast far and wide to gather information from a broad cross-section of stakeholders.

—Jack Percelay, MD, MPH, FHM, pediatric hospitalist, Saint Barnabas Medical Center, New York City, SHM board member

As pediatric hospitalists strive to better demonstrate how they can help hospitals improve the quality of patient care and safety while decreasing its cost, the roundtable is charged with defining and educating healthcare professionals on the key issues. Also in the crosshairs: simultaneously advancing evidence-based medicine and family-based care.

“We need to distinguish that we are not just house physicians, but really establish ourselves as content-area knowledge experts,” Dr. Percelay says. In other words, pediatric hospitalists are physicians who specialize in effective and efficient medicine in resource-intensive facilities.

Pediatric hospitalists also grapple with how to enhance career satisfaction and sustainability at a time when many PHM programs require a burdensome clinical load that fosters burnout. Many PHM leaders also think pediatric hospitalists need extra training but fear they will lose those physicians to fellowships. And as the PHM ranks fill with physicians who have little or no outpatient training, there is the challenge of explaining the capabilities and limitations pediatric hospitalists and primary-care physicians (PCPs) have in order to avoid unrealistic expectations and friction.

Participants in the strategic roundtable aim to address several broad goals outlined in an executive summary, which can be viewed in the “Section on Hospital Medicine” on the AAP Web site (www.aap.org/sections/hospcare/default.cfm). The following are some of the goals:

- Ensure care for hospitalized children is fully integrated and includes the medical home;

- Design and support systems for children that eliminate harm associated with hospital care;

- Develop a skilled and stable workforce that provides expert care for hospitalized children;

- Use collaborative research models to answer questions of clinical efficacy, comparative effectiveness, and quality improvement inclusive of patient safety, and deliver care based on that knowledge;

- Provide the expertise that supports innovative continuing education in the care of the hospitalized child for pediatric hospitalists, trainees, midlevel providers, and hospital staff;

- Create value and provide academic and systems leadership for patients and organizations based on pediatric hospitalists’ unique expertise in PHM clinical care, research, and education; and

- Be leaders and influential agents in local, state, and national healthcare policies that affect hospital care.

Although it was discussed, the roundtable decided against the establishment of a professional organization for pediatric hospitalists. Instead, the group agreed to continue to utilize the resources and organizational support provided by SHM, APA, and AAP. All three groups contributed money to the roundtable, sent representatives to the meeting, and are interested in the results.

“The Academic Pediatric Association has been involved with pediatric hospital medicine from the beginning, and we plan on continuing our involvement,” says Daniel Rauch, MD, FHM, associate director of pediatrics at Elmhurst Hospital Center in New York City and co-chair of the APA’s Hospital Medicine Special Interest Group, which is paying close attention to PHM education and research issues.

Strategic Initiatives

The roundtable established four workgroups: clinical practice/workforce, quality and safety, research, and education. The workgroups are directed to create strategic initiative projects focused on advancing the goals laid out at the roundtable meeting and complete most of the projects no later than the July 2010 PHM Conference in Minneapolis (see “A Closer Look at the Pediatric Hospital Medicine Initiatives,” p. 7). At the 2009 PHM conference in Tampa, Fla., roundtable participants reported on some of the initiatives’ preliminary results.

“I walked away … energized and ready to help change the world, which is a pretty great feeling,” says Jennifer Daru, MD, FAAP, FHM, chief of the division of pediatric hospital medicine at California Pacific Medical Center in San Francisco and co-leader of the roundtable’s clinical practice/workforce workgroup.

One of Dr. Daru’s workgroup’s strategic initiative projects should make Dr. Hale and his pediatric hospitalists at Central Maine Medical Center happy. Dr. Daru’s group is creating a clinical practice dashboard template that PHM programs can use to internally track patient care and compare themselves with other programs and national standards.

“I think very few programs have a dashboard, because it’s a relatively newer thing for pediatric hospital medicine,” Dr. Daru says. “With this dashboard, we want to be able to say, ‘Here are the things you should look at to ensure quality care for your kids, and as you look at them, you should probably track them over time.’ ”

Steve Narang, MD, medical director of quality/safety and pediatric emergency services at Our Lady of the Lake Regional Medical Center and Children’s Hospital in Baton Rouge, La., is leading the quality and safety workgroup, which is focused on patient identification, patient handoffs between pediatric hospitalists and PCPs, and clinical outcomes for common pediatric diagnoses.

“Most doctors don’t like standardized forms or cookbook medicine, but they do understand good care. Hopefully, we will show success in these initiatives and they will serve as a launching pad to other initiatives,” Dr. Narang says.

Dr. Hale, for one, is excited by the initiatives and workgroups, and optimistic the strategic projects will help his program. In recent years, the PHM community has talked about these kinds of advances, and he’s encouraged to see them moving forward. “These initiatives contribute to the strength of our field,” says Dr. Hale, who also serves on the executive board of AAP’s Maine chapter.

About 80 pediatric hospitalists have volunteered to help with the strategic initiatives. Earlier this year, a request for help was broadcast over the Section on Hospital Medicine listserv run by the AAP. It was announced at HM09 in Chicago and the PHM conference in Tampa. Everyone who submitted a resume or CV, references, and a statement of interest is included, Dr. Percelay says. “This is not supposed to be some exclusive club that no one can get into,” he says. “We are committed to a transparent process.”