User login

Not once has Vanessa Yasmin Calderón regretted her decision to go into primary care, but she admits she’s disquieted by the amount of debt she’s accumulated while attending the University of California at Los Angeles for medical school and Harvard University’s Kennedy School of Government in pursuit of a master’s degree in public policy.

“I will be 30 years old when I graduate,” says Calderón, who plans to receive her medical degree in 2010. “Right now, I have no retirement account, and I’m staring at loads of debt in a bad economy. There’s a lot to think about.”

Calderón estimates she will have more than $146,000 in loans when she graduates—a daunting sum for someone who used scholarship money and a part-time job to put herself through college. Although Calderón is committed to a career in emergency or general internal medicine (IM), she has watched many of her peers forgo primary care in favor of anesthesiology, dermatology, and surgical specialties—partly because they are worried about how they are going to pay back their education debt.

“I guarantee you that primary care is being the most affected by rising debt,” says Calderón, vice president of finances for the American Medical Student Association (AMSA).

Her personal observations correlate with more than 15 years’ worth of published medical studies that have found compensation plays a role in dissuading medical students who are facing mountains of debt from choosing primary care. That includes careers in IM and, by extension, careers in HM, as more than 82% of hospitalists consider themselves IM specialists, according to SHM’s 2007-2008 “Bi-Annual Survey on the State of the Hospital Medicine Movement.” This doesn’t bode well for the nation’s future, experts say, because primary care and IM comprise the foundation of our nation’s healthcare system.

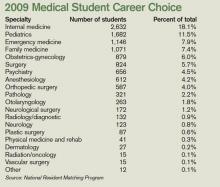

While the steep decline in IM recruits has leveled off in recent years, the number of medical students choosing IM residency (2,632 seniors entered three-year IM residency programs in 2009) is nowhere near the high point (3,884) of the mid-1980s, says Steven E. Weinberger, MD, FACP, senior vice president for medical education and publishing for the American College of Physicians (ACP).

“If there is not a change in how we support students going through medical school, how can we be surprised when they choose a higher-paying specialty?” says Michael Rosenthal, MD, professor and vice chairman of academic programs and research in the Department of Family and Community Medicine at Thomas Jefferson University in Philadelphia.

Loan Obligations

In 2006, more than 84% of medical school graduates had educational debt, with a median debt of $120,000 for graduates of public medical schools and $160,000 for graduates of private medical schools, according to a 2007 report by the Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC). In comparison, the same report shows that, in 2001, the median debt for public and private medical school graduates was $86,000 and $120,000, respectively.

Just as the rising cost of healthcare leads to skyrocketing health insurance premiums, so, too, does it result in higher tuition and fees for medical students, says Brian Hurley, MD, MBA, president of AMSA. Public medical schools in particular are affected as state governments, which are obliged to annually balance their budgets, often pay for burgeoning healthcare expenses by cutting subsidies to higher education, he says.

“In a way, universities are balancing their squeezed budgets on the backs of their students,” says Dr. Hurley, who recently graduated from the University of Southern California’s Keck School of Medicine with $300,000 in educational debt.

There is no regulatory body in place that can moderate medical school tuition increases, he laments. But medical students are partly to blame for the spiraling tuition costs, Dr. Hurley says, because students rarely base their school selections on tuition costs. As a result, medical schools aren’t forced to decelerate tuition hikes, because students aren’t taking them to task.

“When pre-med students decide to go to medical school, they have this idea that they will have more opportunities if they can go to Harvard or some other top medical school,” Dr. Hurley says. “Students want to go to the best school they can, and they trust that everything will work itself out in the end.”

Meanwhile, escalating tuition costs and debt loads deter prospective medical students from low-income backgrounds from going to medical school, which hampers efforts to diversify the nation’s medical workforce and provide quality healthcare in poorer communities. “People tend to practice medicine where they came from,” Dr. Hurley says. “It’s not a perfect correlation, but it does match up.”

For its part, AMSA is educating pre-med students on how to select more affordable medical schools that provide a quality education. The association also focuses on teaching medical students how to manage educational debt. “The public perception is that physicians are rich, and it’s a perception we haven’t successfully been able to combat,” Dr. Hurley says. “Right now, medical student debt is not seen as a healthcare issue. We can try to work within the Higher Education Act to better subsidize medical students’ education, but lawmakers tend to focus on undergraduate education.”

Nonprocedurals at Risk

But medical students’ rising debt is a healthcare issue, experts say. “Many students are now leaving medical school with over $200,000 in debt,” says Daniel Dressler, MD, FHM, SHM board member and education director for the HM section and associate program director for the IM residency program at Emory University’s School of Medicine in Atlanta. “As the cost of education increases each year and significantly outpaces the rate of increase in physician salaries, students may look toward specialties where they can pay that off within a more reasonable time frame while they begin their families and build their lives.”

Aside from primary care and IM, the medical fields that have been at the losing end of the bloated-educational-debt trend are nonprocedural-based IM specialties such as geriatrics, endocrinology, pulmonary/critical care, rheumatology, and infectious disease, says Jeffrey Wiese, MD, FACP, FHM, SHM president-elect and associate dean of graduate medical education and director of the IM residency program at Tulane University Hospital in New Orleans.

Doctors in nonprocedural-based IM specialties generally receive lower compensation than those in procedural-based IM specialties like cardiology, gastroenterology, and nephrology. For example, the median annual compensation for private-practice physicians in cardiology and gastroenterology is nearly $385,000; the median salary of endocrinologists and rheumatologists is $184,000; and the median salary for general internists is $166,000, according to a 2007 compensation survey by the Medical Group Management Association.

IM physician salaries always have been significantly less than the salaries of procedure-based specialists, Dr. Wiese says. “But now the workload of general internists has grown, and it hasn’t grown proportional to compensation, as compared to other specialties,” he says. “That’s compelling to students.”

Dr. Weinberger agrees the compensation disparity is disconcerting to medical students who consider IM because “they are choosing a harder lifestyle. It doesn’t help that the doctors who are practicing internal medicine complain about the hassles and the problems with reimbursement. The role models medical students look up to are not as happy as they used to be.”

—Daniel Dressler, MD, FHM, Emory University School of Medicine, Atlanta

HM Holds Its Own

Hospitalists seem to be surviving relatively well in these difficult times, according to data compiled by the American College of Physicians. In 2002, 4% of third-year IM residents surveyed said they were choosing HM. That number has risen steadily, to 10% in 2007 and 2008, Dr. Weinberger notes.

HM compensation varies widely, Dr. Wiese says; however, the mean salary for HM physicians was $196,700 in 2007, according to SHM survey data. That puts hospitalist salaries at the mid- to lower end of the scale when compared with all medical specialties but smack in the middle of IM specialties.

A 2008 study published in the Annals of Internal Medicine suggests that U.S. categorical IM residents with educational debt of $50,000 or more are more likely than those with no debt to choose a HM career, possibly because they can enter the work force right after residency training, as opposed to continuing with fellowship training for a subspecialty at substantially less compensation.1

For HM to continue gaining ground, many say the specialty has to go on the offensive and not wait for medical students and residents to decide to become hospitalists. “It will be more difficult to recruit from residency programs if there are fewer people going into internal medicine,” Dr. Dressler says. “Hospital medicine will simply be competing for a smaller pool of residents.”

Dr. Wiese says academia can contribute by providing a solid foundation in medicine and a clear path to HM careers as next-generation physicians and leaders. “Hospitalists assuming more of a teaching role are good not only for hospital medicine, but internal medicine education,” Dr. Wiese says. “The stronger the mentors, the more internal medicine students you’re going to recruit.”

The same can be said of medical practice settings, Dr. Weinberger explains. Many ambulatory settings in which medical students and residents work are among the most poorly supported and operated, even though they have the sickest patients, he says. That can be a huge turnoff for medical students. To counter that negative, students must be exposed to higher-quality ambulatory settings, Dr. Weinberger says.

Medical schools can help the cause by admitting students who show an inclination to go into primary care and IM, says Dr. Rosenthal, of Thomas Jefferson University. Those students are more likely to leave medical school in pursuit of a generalist career—especially if they’re matched with good IM mentors.

Federal and state governments should consider paying the educational loans of medical students who promise to practice primary care or IM for a certain period of time, especially in high-need communities, Dr. Rosenthal says. Fifteen years ago, he was a lead author in a study published in the Journal of the American Medical Association that found a significant number of fourth-year medical students would go into primary care, including general IM, if positive changes were made to income, hours worked, and loan repayment.2 Dr. Rosenthal says he’s not surprised physicians and researchers are writing about the same topic today.

“The article was written in the Clinton era, at a time when there was a sense the nation’s healthcare system might be reformed. But there was backlash to the plan,” Dr. Rosenthal says. “Today, we are again considering healthcare reform, except this time people are more willing to accept it because the high cost of healthcare is now affecting businesses and the economy.”

Change in Outlook

President Obama’s stated goal of extending health insurance to more Americans makes increasing the ranks of primary-care physicians, general internists, and hospitalists even more urgent, experts say. In Massachusetts, a state that is experimenting with universal health coverage for all of its residents, a shortfall in the primary-care work force is evident, Dr. Weinberger says. It is troubling news, because research consistently shows that when a primary-care physician coordinates a patient’s care, the result is fewer visits to the ED and medical specialists, he says.

“What this means is, we need more internists in the outpatient side to care for these patients longitudinally,” Dr. Dressler says. “We need more hospitalists, as the burden of inpatient care is very likely to grow as well.”

Dr. Rosenthal says more students will be attracted to medicine in part because the recession is making solid, good-paying jobs that play a vital role in communities very attractive. If better support were available for students interested in primary care, he says, he would have reason to hope more students would choose generalist careers.

“There was this expectation among people in their 20s that, if they were bright and able, they would have a nice lifestyle without having to work too hard. But the recession is having an effect on this generation’s outlook,” Dr. Rosenthal says. “I think there is a changing landscape out there.” TH

Lisa Ryan is a freelance writer based in New Jersey.

References

- McDonald FS, West CP, Popkave C, Kolars JC. Educational debt and reported career plans among internal medicine residents. Ann Intern Med. 2008;149(6): 416-420.

- Rosenthal MP, Diamond JJ, Rabinowitz HK, et al. Influence of income, hours worked, and loan repayment on medical students’ decision to pursue a primary care career. JAMA. 1994;271(12):914-917.

Not once has Vanessa Yasmin Calderón regretted her decision to go into primary care, but she admits she’s disquieted by the amount of debt she’s accumulated while attending the University of California at Los Angeles for medical school and Harvard University’s Kennedy School of Government in pursuit of a master’s degree in public policy.

“I will be 30 years old when I graduate,” says Calderón, who plans to receive her medical degree in 2010. “Right now, I have no retirement account, and I’m staring at loads of debt in a bad economy. There’s a lot to think about.”

Calderón estimates she will have more than $146,000 in loans when she graduates—a daunting sum for someone who used scholarship money and a part-time job to put herself through college. Although Calderón is committed to a career in emergency or general internal medicine (IM), she has watched many of her peers forgo primary care in favor of anesthesiology, dermatology, and surgical specialties—partly because they are worried about how they are going to pay back their education debt.

“I guarantee you that primary care is being the most affected by rising debt,” says Calderón, vice president of finances for the American Medical Student Association (AMSA).

Her personal observations correlate with more than 15 years’ worth of published medical studies that have found compensation plays a role in dissuading medical students who are facing mountains of debt from choosing primary care. That includes careers in IM and, by extension, careers in HM, as more than 82% of hospitalists consider themselves IM specialists, according to SHM’s 2007-2008 “Bi-Annual Survey on the State of the Hospital Medicine Movement.” This doesn’t bode well for the nation’s future, experts say, because primary care and IM comprise the foundation of our nation’s healthcare system.

While the steep decline in IM recruits has leveled off in recent years, the number of medical students choosing IM residency (2,632 seniors entered three-year IM residency programs in 2009) is nowhere near the high point (3,884) of the mid-1980s, says Steven E. Weinberger, MD, FACP, senior vice president for medical education and publishing for the American College of Physicians (ACP).

“If there is not a change in how we support students going through medical school, how can we be surprised when they choose a higher-paying specialty?” says Michael Rosenthal, MD, professor and vice chairman of academic programs and research in the Department of Family and Community Medicine at Thomas Jefferson University in Philadelphia.

Loan Obligations

In 2006, more than 84% of medical school graduates had educational debt, with a median debt of $120,000 for graduates of public medical schools and $160,000 for graduates of private medical schools, according to a 2007 report by the Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC). In comparison, the same report shows that, in 2001, the median debt for public and private medical school graduates was $86,000 and $120,000, respectively.

Just as the rising cost of healthcare leads to skyrocketing health insurance premiums, so, too, does it result in higher tuition and fees for medical students, says Brian Hurley, MD, MBA, president of AMSA. Public medical schools in particular are affected as state governments, which are obliged to annually balance their budgets, often pay for burgeoning healthcare expenses by cutting subsidies to higher education, he says.

“In a way, universities are balancing their squeezed budgets on the backs of their students,” says Dr. Hurley, who recently graduated from the University of Southern California’s Keck School of Medicine with $300,000 in educational debt.

There is no regulatory body in place that can moderate medical school tuition increases, he laments. But medical students are partly to blame for the spiraling tuition costs, Dr. Hurley says, because students rarely base their school selections on tuition costs. As a result, medical schools aren’t forced to decelerate tuition hikes, because students aren’t taking them to task.

“When pre-med students decide to go to medical school, they have this idea that they will have more opportunities if they can go to Harvard or some other top medical school,” Dr. Hurley says. “Students want to go to the best school they can, and they trust that everything will work itself out in the end.”

Meanwhile, escalating tuition costs and debt loads deter prospective medical students from low-income backgrounds from going to medical school, which hampers efforts to diversify the nation’s medical workforce and provide quality healthcare in poorer communities. “People tend to practice medicine where they came from,” Dr. Hurley says. “It’s not a perfect correlation, but it does match up.”

For its part, AMSA is educating pre-med students on how to select more affordable medical schools that provide a quality education. The association also focuses on teaching medical students how to manage educational debt. “The public perception is that physicians are rich, and it’s a perception we haven’t successfully been able to combat,” Dr. Hurley says. “Right now, medical student debt is not seen as a healthcare issue. We can try to work within the Higher Education Act to better subsidize medical students’ education, but lawmakers tend to focus on undergraduate education.”

Nonprocedurals at Risk

But medical students’ rising debt is a healthcare issue, experts say. “Many students are now leaving medical school with over $200,000 in debt,” says Daniel Dressler, MD, FHM, SHM board member and education director for the HM section and associate program director for the IM residency program at Emory University’s School of Medicine in Atlanta. “As the cost of education increases each year and significantly outpaces the rate of increase in physician salaries, students may look toward specialties where they can pay that off within a more reasonable time frame while they begin their families and build their lives.”

Aside from primary care and IM, the medical fields that have been at the losing end of the bloated-educational-debt trend are nonprocedural-based IM specialties such as geriatrics, endocrinology, pulmonary/critical care, rheumatology, and infectious disease, says Jeffrey Wiese, MD, FACP, FHM, SHM president-elect and associate dean of graduate medical education and director of the IM residency program at Tulane University Hospital in New Orleans.

Doctors in nonprocedural-based IM specialties generally receive lower compensation than those in procedural-based IM specialties like cardiology, gastroenterology, and nephrology. For example, the median annual compensation for private-practice physicians in cardiology and gastroenterology is nearly $385,000; the median salary of endocrinologists and rheumatologists is $184,000; and the median salary for general internists is $166,000, according to a 2007 compensation survey by the Medical Group Management Association.

IM physician salaries always have been significantly less than the salaries of procedure-based specialists, Dr. Wiese says. “But now the workload of general internists has grown, and it hasn’t grown proportional to compensation, as compared to other specialties,” he says. “That’s compelling to students.”

Dr. Weinberger agrees the compensation disparity is disconcerting to medical students who consider IM because “they are choosing a harder lifestyle. It doesn’t help that the doctors who are practicing internal medicine complain about the hassles and the problems with reimbursement. The role models medical students look up to are not as happy as they used to be.”

—Daniel Dressler, MD, FHM, Emory University School of Medicine, Atlanta

HM Holds Its Own

Hospitalists seem to be surviving relatively well in these difficult times, according to data compiled by the American College of Physicians. In 2002, 4% of third-year IM residents surveyed said they were choosing HM. That number has risen steadily, to 10% in 2007 and 2008, Dr. Weinberger notes.

HM compensation varies widely, Dr. Wiese says; however, the mean salary for HM physicians was $196,700 in 2007, according to SHM survey data. That puts hospitalist salaries at the mid- to lower end of the scale when compared with all medical specialties but smack in the middle of IM specialties.

A 2008 study published in the Annals of Internal Medicine suggests that U.S. categorical IM residents with educational debt of $50,000 or more are more likely than those with no debt to choose a HM career, possibly because they can enter the work force right after residency training, as opposed to continuing with fellowship training for a subspecialty at substantially less compensation.1

For HM to continue gaining ground, many say the specialty has to go on the offensive and not wait for medical students and residents to decide to become hospitalists. “It will be more difficult to recruit from residency programs if there are fewer people going into internal medicine,” Dr. Dressler says. “Hospital medicine will simply be competing for a smaller pool of residents.”

Dr. Wiese says academia can contribute by providing a solid foundation in medicine and a clear path to HM careers as next-generation physicians and leaders. “Hospitalists assuming more of a teaching role are good not only for hospital medicine, but internal medicine education,” Dr. Wiese says. “The stronger the mentors, the more internal medicine students you’re going to recruit.”

The same can be said of medical practice settings, Dr. Weinberger explains. Many ambulatory settings in which medical students and residents work are among the most poorly supported and operated, even though they have the sickest patients, he says. That can be a huge turnoff for medical students. To counter that negative, students must be exposed to higher-quality ambulatory settings, Dr. Weinberger says.

Medical schools can help the cause by admitting students who show an inclination to go into primary care and IM, says Dr. Rosenthal, of Thomas Jefferson University. Those students are more likely to leave medical school in pursuit of a generalist career—especially if they’re matched with good IM mentors.

Federal and state governments should consider paying the educational loans of medical students who promise to practice primary care or IM for a certain period of time, especially in high-need communities, Dr. Rosenthal says. Fifteen years ago, he was a lead author in a study published in the Journal of the American Medical Association that found a significant number of fourth-year medical students would go into primary care, including general IM, if positive changes were made to income, hours worked, and loan repayment.2 Dr. Rosenthal says he’s not surprised physicians and researchers are writing about the same topic today.

“The article was written in the Clinton era, at a time when there was a sense the nation’s healthcare system might be reformed. But there was backlash to the plan,” Dr. Rosenthal says. “Today, we are again considering healthcare reform, except this time people are more willing to accept it because the high cost of healthcare is now affecting businesses and the economy.”

Change in Outlook

President Obama’s stated goal of extending health insurance to more Americans makes increasing the ranks of primary-care physicians, general internists, and hospitalists even more urgent, experts say. In Massachusetts, a state that is experimenting with universal health coverage for all of its residents, a shortfall in the primary-care work force is evident, Dr. Weinberger says. It is troubling news, because research consistently shows that when a primary-care physician coordinates a patient’s care, the result is fewer visits to the ED and medical specialists, he says.

“What this means is, we need more internists in the outpatient side to care for these patients longitudinally,” Dr. Dressler says. “We need more hospitalists, as the burden of inpatient care is very likely to grow as well.”

Dr. Rosenthal says more students will be attracted to medicine in part because the recession is making solid, good-paying jobs that play a vital role in communities very attractive. If better support were available for students interested in primary care, he says, he would have reason to hope more students would choose generalist careers.

“There was this expectation among people in their 20s that, if they were bright and able, they would have a nice lifestyle without having to work too hard. But the recession is having an effect on this generation’s outlook,” Dr. Rosenthal says. “I think there is a changing landscape out there.” TH

Lisa Ryan is a freelance writer based in New Jersey.

References

- McDonald FS, West CP, Popkave C, Kolars JC. Educational debt and reported career plans among internal medicine residents. Ann Intern Med. 2008;149(6): 416-420.

- Rosenthal MP, Diamond JJ, Rabinowitz HK, et al. Influence of income, hours worked, and loan repayment on medical students’ decision to pursue a primary care career. JAMA. 1994;271(12):914-917.

Not once has Vanessa Yasmin Calderón regretted her decision to go into primary care, but she admits she’s disquieted by the amount of debt she’s accumulated while attending the University of California at Los Angeles for medical school and Harvard University’s Kennedy School of Government in pursuit of a master’s degree in public policy.

“I will be 30 years old when I graduate,” says Calderón, who plans to receive her medical degree in 2010. “Right now, I have no retirement account, and I’m staring at loads of debt in a bad economy. There’s a lot to think about.”

Calderón estimates she will have more than $146,000 in loans when she graduates—a daunting sum for someone who used scholarship money and a part-time job to put herself through college. Although Calderón is committed to a career in emergency or general internal medicine (IM), she has watched many of her peers forgo primary care in favor of anesthesiology, dermatology, and surgical specialties—partly because they are worried about how they are going to pay back their education debt.

“I guarantee you that primary care is being the most affected by rising debt,” says Calderón, vice president of finances for the American Medical Student Association (AMSA).

Her personal observations correlate with more than 15 years’ worth of published medical studies that have found compensation plays a role in dissuading medical students who are facing mountains of debt from choosing primary care. That includes careers in IM and, by extension, careers in HM, as more than 82% of hospitalists consider themselves IM specialists, according to SHM’s 2007-2008 “Bi-Annual Survey on the State of the Hospital Medicine Movement.” This doesn’t bode well for the nation’s future, experts say, because primary care and IM comprise the foundation of our nation’s healthcare system.

While the steep decline in IM recruits has leveled off in recent years, the number of medical students choosing IM residency (2,632 seniors entered three-year IM residency programs in 2009) is nowhere near the high point (3,884) of the mid-1980s, says Steven E. Weinberger, MD, FACP, senior vice president for medical education and publishing for the American College of Physicians (ACP).

“If there is not a change in how we support students going through medical school, how can we be surprised when they choose a higher-paying specialty?” says Michael Rosenthal, MD, professor and vice chairman of academic programs and research in the Department of Family and Community Medicine at Thomas Jefferson University in Philadelphia.

Loan Obligations

In 2006, more than 84% of medical school graduates had educational debt, with a median debt of $120,000 for graduates of public medical schools and $160,000 for graduates of private medical schools, according to a 2007 report by the Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC). In comparison, the same report shows that, in 2001, the median debt for public and private medical school graduates was $86,000 and $120,000, respectively.

Just as the rising cost of healthcare leads to skyrocketing health insurance premiums, so, too, does it result in higher tuition and fees for medical students, says Brian Hurley, MD, MBA, president of AMSA. Public medical schools in particular are affected as state governments, which are obliged to annually balance their budgets, often pay for burgeoning healthcare expenses by cutting subsidies to higher education, he says.

“In a way, universities are balancing their squeezed budgets on the backs of their students,” says Dr. Hurley, who recently graduated from the University of Southern California’s Keck School of Medicine with $300,000 in educational debt.

There is no regulatory body in place that can moderate medical school tuition increases, he laments. But medical students are partly to blame for the spiraling tuition costs, Dr. Hurley says, because students rarely base their school selections on tuition costs. As a result, medical schools aren’t forced to decelerate tuition hikes, because students aren’t taking them to task.

“When pre-med students decide to go to medical school, they have this idea that they will have more opportunities if they can go to Harvard or some other top medical school,” Dr. Hurley says. “Students want to go to the best school they can, and they trust that everything will work itself out in the end.”

Meanwhile, escalating tuition costs and debt loads deter prospective medical students from low-income backgrounds from going to medical school, which hampers efforts to diversify the nation’s medical workforce and provide quality healthcare in poorer communities. “People tend to practice medicine where they came from,” Dr. Hurley says. “It’s not a perfect correlation, but it does match up.”

For its part, AMSA is educating pre-med students on how to select more affordable medical schools that provide a quality education. The association also focuses on teaching medical students how to manage educational debt. “The public perception is that physicians are rich, and it’s a perception we haven’t successfully been able to combat,” Dr. Hurley says. “Right now, medical student debt is not seen as a healthcare issue. We can try to work within the Higher Education Act to better subsidize medical students’ education, but lawmakers tend to focus on undergraduate education.”

Nonprocedurals at Risk

But medical students’ rising debt is a healthcare issue, experts say. “Many students are now leaving medical school with over $200,000 in debt,” says Daniel Dressler, MD, FHM, SHM board member and education director for the HM section and associate program director for the IM residency program at Emory University’s School of Medicine in Atlanta. “As the cost of education increases each year and significantly outpaces the rate of increase in physician salaries, students may look toward specialties where they can pay that off within a more reasonable time frame while they begin their families and build their lives.”

Aside from primary care and IM, the medical fields that have been at the losing end of the bloated-educational-debt trend are nonprocedural-based IM specialties such as geriatrics, endocrinology, pulmonary/critical care, rheumatology, and infectious disease, says Jeffrey Wiese, MD, FACP, FHM, SHM president-elect and associate dean of graduate medical education and director of the IM residency program at Tulane University Hospital in New Orleans.

Doctors in nonprocedural-based IM specialties generally receive lower compensation than those in procedural-based IM specialties like cardiology, gastroenterology, and nephrology. For example, the median annual compensation for private-practice physicians in cardiology and gastroenterology is nearly $385,000; the median salary of endocrinologists and rheumatologists is $184,000; and the median salary for general internists is $166,000, according to a 2007 compensation survey by the Medical Group Management Association.

IM physician salaries always have been significantly less than the salaries of procedure-based specialists, Dr. Wiese says. “But now the workload of general internists has grown, and it hasn’t grown proportional to compensation, as compared to other specialties,” he says. “That’s compelling to students.”

Dr. Weinberger agrees the compensation disparity is disconcerting to medical students who consider IM because “they are choosing a harder lifestyle. It doesn’t help that the doctors who are practicing internal medicine complain about the hassles and the problems with reimbursement. The role models medical students look up to are not as happy as they used to be.”

—Daniel Dressler, MD, FHM, Emory University School of Medicine, Atlanta

HM Holds Its Own

Hospitalists seem to be surviving relatively well in these difficult times, according to data compiled by the American College of Physicians. In 2002, 4% of third-year IM residents surveyed said they were choosing HM. That number has risen steadily, to 10% in 2007 and 2008, Dr. Weinberger notes.

HM compensation varies widely, Dr. Wiese says; however, the mean salary for HM physicians was $196,700 in 2007, according to SHM survey data. That puts hospitalist salaries at the mid- to lower end of the scale when compared with all medical specialties but smack in the middle of IM specialties.

A 2008 study published in the Annals of Internal Medicine suggests that U.S. categorical IM residents with educational debt of $50,000 or more are more likely than those with no debt to choose a HM career, possibly because they can enter the work force right after residency training, as opposed to continuing with fellowship training for a subspecialty at substantially less compensation.1

For HM to continue gaining ground, many say the specialty has to go on the offensive and not wait for medical students and residents to decide to become hospitalists. “It will be more difficult to recruit from residency programs if there are fewer people going into internal medicine,” Dr. Dressler says. “Hospital medicine will simply be competing for a smaller pool of residents.”

Dr. Wiese says academia can contribute by providing a solid foundation in medicine and a clear path to HM careers as next-generation physicians and leaders. “Hospitalists assuming more of a teaching role are good not only for hospital medicine, but internal medicine education,” Dr. Wiese says. “The stronger the mentors, the more internal medicine students you’re going to recruit.”

The same can be said of medical practice settings, Dr. Weinberger explains. Many ambulatory settings in which medical students and residents work are among the most poorly supported and operated, even though they have the sickest patients, he says. That can be a huge turnoff for medical students. To counter that negative, students must be exposed to higher-quality ambulatory settings, Dr. Weinberger says.

Medical schools can help the cause by admitting students who show an inclination to go into primary care and IM, says Dr. Rosenthal, of Thomas Jefferson University. Those students are more likely to leave medical school in pursuit of a generalist career—especially if they’re matched with good IM mentors.

Federal and state governments should consider paying the educational loans of medical students who promise to practice primary care or IM for a certain period of time, especially in high-need communities, Dr. Rosenthal says. Fifteen years ago, he was a lead author in a study published in the Journal of the American Medical Association that found a significant number of fourth-year medical students would go into primary care, including general IM, if positive changes were made to income, hours worked, and loan repayment.2 Dr. Rosenthal says he’s not surprised physicians and researchers are writing about the same topic today.

“The article was written in the Clinton era, at a time when there was a sense the nation’s healthcare system might be reformed. But there was backlash to the plan,” Dr. Rosenthal says. “Today, we are again considering healthcare reform, except this time people are more willing to accept it because the high cost of healthcare is now affecting businesses and the economy.”

Change in Outlook

President Obama’s stated goal of extending health insurance to more Americans makes increasing the ranks of primary-care physicians, general internists, and hospitalists even more urgent, experts say. In Massachusetts, a state that is experimenting with universal health coverage for all of its residents, a shortfall in the primary-care work force is evident, Dr. Weinberger says. It is troubling news, because research consistently shows that when a primary-care physician coordinates a patient’s care, the result is fewer visits to the ED and medical specialists, he says.

“What this means is, we need more internists in the outpatient side to care for these patients longitudinally,” Dr. Dressler says. “We need more hospitalists, as the burden of inpatient care is very likely to grow as well.”

Dr. Rosenthal says more students will be attracted to medicine in part because the recession is making solid, good-paying jobs that play a vital role in communities very attractive. If better support were available for students interested in primary care, he says, he would have reason to hope more students would choose generalist careers.

“There was this expectation among people in their 20s that, if they were bright and able, they would have a nice lifestyle without having to work too hard. But the recession is having an effect on this generation’s outlook,” Dr. Rosenthal says. “I think there is a changing landscape out there.” TH

Lisa Ryan is a freelance writer based in New Jersey.

References

- McDonald FS, West CP, Popkave C, Kolars JC. Educational debt and reported career plans among internal medicine residents. Ann Intern Med. 2008;149(6): 416-420.

- Rosenthal MP, Diamond JJ, Rabinowitz HK, et al. Influence of income, hours worked, and loan repayment on medical students’ decision to pursue a primary care career. JAMA. 1994;271(12):914-917.