User login

Avoid Getting Stuck: A Practical Guide to Managing Chronic Constipation

Introduction

Constipation affects one in six people worldwide and accounts for one third of outpatient visits.1 Chronic constipation is defined by difficult, infrequent, and/or incomplete defecation, quantified by less than three spontaneous bowel movements per week, persisting for at least 3 months. Patients may complain of straining during defecation, incomplete evacuation, hard stools (Bristol stool scale [BSS] type 1-2), and fullness or bloating. Chronic constipation can be subclassified as either a primary or secondary disorder.1,2

Primary Constipation Disorders

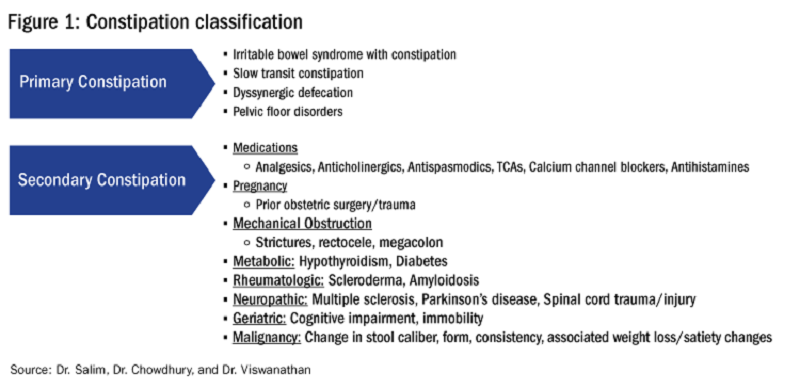

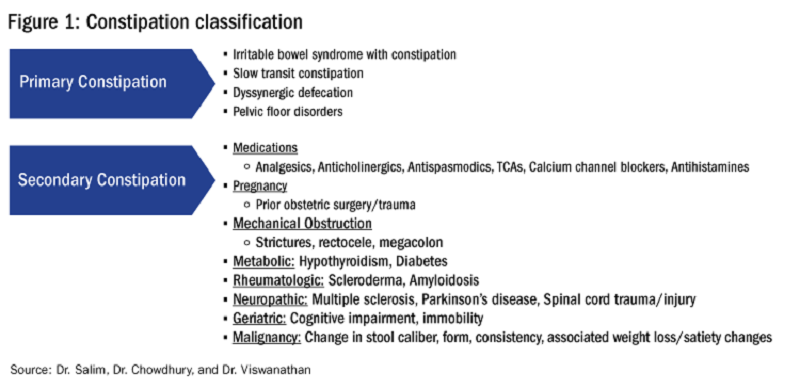

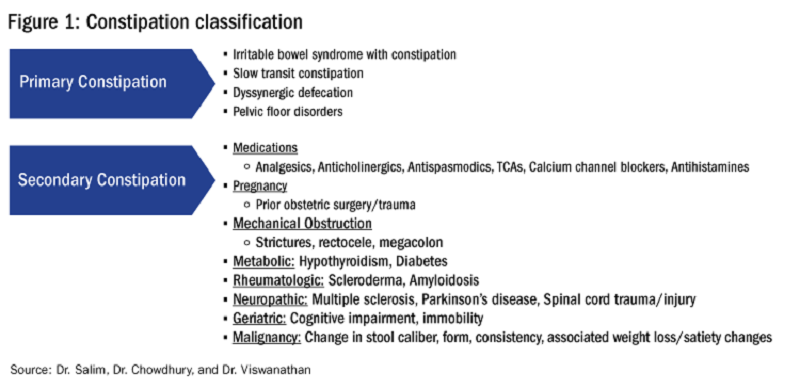

Primary constipation includes disorders of the colon or anorectum. This includes irritable bowel syndrome with constipation (IBS-C), chronic idiopathic constipation (CIC), slow transit constipation (STC), dyssynergic defecation, and pelvic floor disorders (see Figure 1).

IBS-C

IBS-C is a chronic disorder of the gut-brain axis with a worldwide prevalence of 1.3% and a prevalence of 6%-16% in the United States, United Kingdom, and Canada, with females more likely to seek care than males.2 The economic impact of IBS-C is estimated to be $1.5 billion–$10 billion per year in the United States alone.3 The distinguishing characteristic is abdominal pain, however IBS-C can present with a constellation of symptoms. The diagnostic paradigm has shifted from IBS being a diagnosis of exclusion to now using a positive diagnostic strategy.2 Using this Rome IV criteria, one can make the diagnosis with > 95% accuracy.2,4

CIC

CIC, previously defined as functional constipation, is a disorder defined by incomplete defecation and difficult or infrequent stool. CIC is diagnosed in patients without an underlying anatomic or structural abnormality. Rome IV Criteria helps further classify the defining characteristics of chronic idiopathic constipation.2

Slow Transit Constipation

STC is characterized by impaired colonic transit time in the absence of pelvic floor dysfunction. It presents with infrequent bowel movements, diminished urgency, and/or straining with defecation.

Defecatory Disorders: Dyssynergic Defecation and Pelvic Floor Dysfunction

Defecatory disorders (DDs) result from alterations in the colonic-neural pathway with an unclear pathogenesis. A firm understanding of colonic physiology is necessary to identify DDs. The right colon helps to store and mix stool contents, the left colon helps add water to the stool, and the anal canal and rectum enable defecation and maintain continence. Any alteration along this physiologic pathway results in DDs.5

DDs primarily develop via maladaptive pelvic floor contraction during defecation or from muscle or nerve injury and include functional outlet obstruction, anorectal dyssynergia, and pelvic floor dysfunction. Increased resistance to defecation results from anismus, paradoxical anal sphincter contraction, or incomplete relaxation of the pelvic floor and external anal sphincter. This muscle incoordination is described as dyssynergia. DDs can involve either muscle or nerve dysfunction or a combination of the two. Reduced rectal sensation caused by reduced sensory triggers can cause stasis of stool, thus propagating the cycle of constipation. Over time, excessive straining can weaken the pelvic floor, increasing the risk of excessive perineal descent, rectal intussusception, solitary rectal ulcer syndrome, and pudendal neuropathy.5 Thus, identification of DDs is crucial in patients with chronic constipation.

Secondary Constipation Disorders

Secondary constipation disorders are a result of an alternate process and warrant a thorough review of outpatient medications and past medical history. Figure 1 outlines the most common causes of secondary constipation, which span a wide differential.

Clinical Evaluation

The evaluation of constipation begins with a thorough history. Description of bowel habits should include frequency, duration, straining, stool consistency using a Bristol stool chart, complete vs incomplete evacuation, pain, bloating, and use of digital maneuvers (vaginal splinting or digital stool removal). One should inquire about back trauma/surgeries and obstetric history to include vaginal forceps injury or episiotomy.

With increased smartphone use, toilet time on average has increased and can contribute to maladaptive bowel habits.6 Patients may not realize they are constipated, so patient education is critical. A patient with daily bowel movements ranging between BSS type 1-6 with incomplete evacuation might complain of diarrhea but may in fact have constipation with overflow diarrhea, for example. Past medical history is also clinically relevant, as systemic conditions can cause secondary constipation. A constipated patient should also be asked what therapies he/she has tried prior to gastroenterology referral as primary care referrals for constipation account for 8 million visits to gastroenterology per year.7

While a sensitive topic, inquire about abuse history, especially in those with childhood constipation symptoms. There is a positive correlation between childhood constipation and physical, emotional, and sexual abuse and, for any number of reasons, your patient may be reluctant to share this or undergo a digital rectal exam (DRE).8 In such cases, be sensitive in asking for this history in private rather than with other family members around and always perform this exam with a chaperone present.

A detailed physical exam is an indispensable tool all gastroenterologists must master when evaluating a constipated patient. Some key exam findings include abdominal distention, high-pitched bowel sounds, and presence of a succussion splash indicating obstructive pathology. Dry skin and brittle hair indicate hypothyroidism while hypermobile joints and skin laxity suggest connective tissue disease. Finally, a physical examination is incomplete without a DRE.

DRE

DRE is an often-overlooked physical exam component which provides helpful insight that can guide management. An informed DRE can help identify structural disorders such as fissure, hemorrhoids, anorectal mass, fecal impaction, rectal prolapse, and excessive perineal descent syndrome.9 Unless contraindicated, DRE should be a standard part of the workup of a patient with chronic constipation.

Workup

Colonoscopy

The role of colonoscopy in chronic constipation is low yield and only indicated if alarm signs are present.2 When no organic causes can be identified, the patient is deemed to have a functional bowel or motility disorder leading to constipation.

Colonic Transit Time

Colonic transit time (CTT) can be evaluated by assessing the presence of radio-opaque sitz markers in the colon with an abdominal x-ray 5 days after ingestion. The presence of five or more sitz markers may indicate STC. However, this can also signal an obstructive defecatory disorder. Colon scintigraphy can determine whether there is diffuse colonic dysmotility or dysfunction in a specific segment of the colon.10

Anorectal Function Testing (AFT)

AFT can evaluate DDs, such as fecal incontinence, dyssynergic defecation, rectal sensory disorders, anorectal pain, and rectal prolapse. AFT comprises three tests: anorectal manometry (ARM), balloon expulsion test (BET), and rectal sensory testing. These assess the defecation, continence, and sensory mechanisms of the rectum, respectively.

ARM testing employs a thin, flexible probe with an attached sensor that is inserted into the rectum to measure internal and external sphincter pressures while at rest, squeezing, and bearing down to give a functional assessment of sphincter tone.11 Cough or party balloon test assesses continence and sphincter strength. Rectal sensation is assessed by inflating a balloon incrementally and asking the patient to indicate first sensation, urgency to defecate, and discomfort. If both ARM and BET are abnormal, the patient meets diagnostic criteria for dyssynergic defecation.12

Pelvic floor disorders can be further assessed by MR defecography or barium defecography. Barium defecography is the more widely available of the two. MR defecography is a dynamic study that directly assesses pelvic floor muscles and endopelvic fascia during various stages of defecation and considered superior. This testing modality can distinguish between functional causes such as dyssynergia or pelvic floor dysfunction and structural causes of obstruction such as rectocele, rectal prolapse, or rectal intussusception. MR defecography is helpful when dyssynergia is suggested by ARM with a normal BET or if there is an absent recto-anal inhibitory reflex on ARM, which may suggest rectal intussusception.

Management

CIC

Incorporating 20-30 g of total soluble fiber, such as psyllium in individuals with low dietary fiber intake is the first-line recommendation for CIC.13 If response to a trial of fiber supplementation is inadequate, over-the-counter (OTC) osmotic laxatives such as polyethylene glycol and magnesium oxide can be incorporated. In the event of failure of OTC osmotic laxatives, lactulose can be considered. Stimulant laxatives such as senna, bisacodyl, or sodium picosulfate can be added as an adjunctive measure for short periods of time, defined as daily for 4 weeks or less.

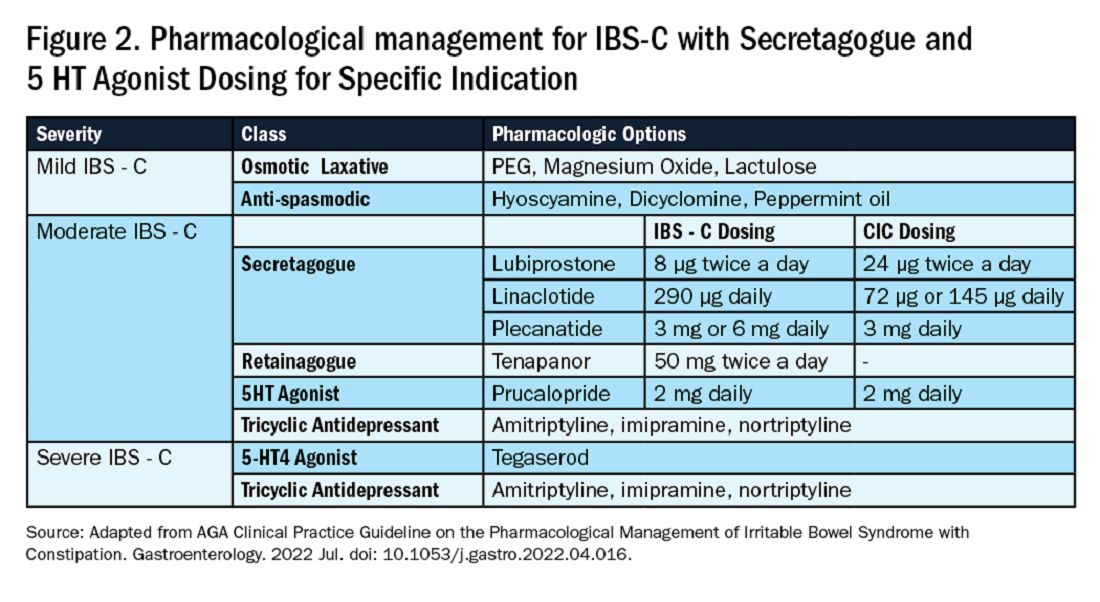

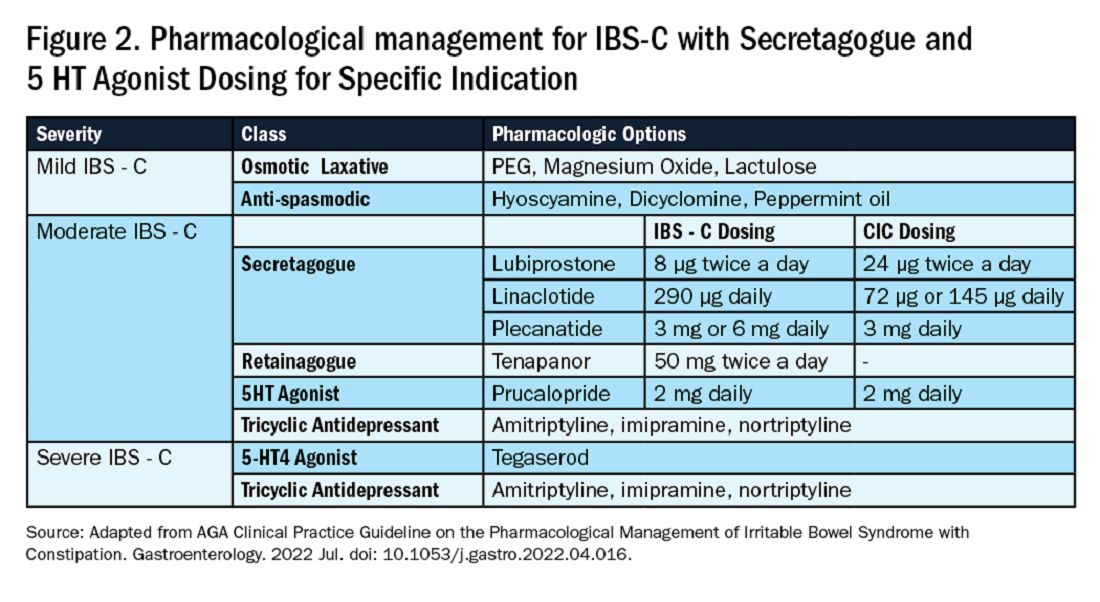

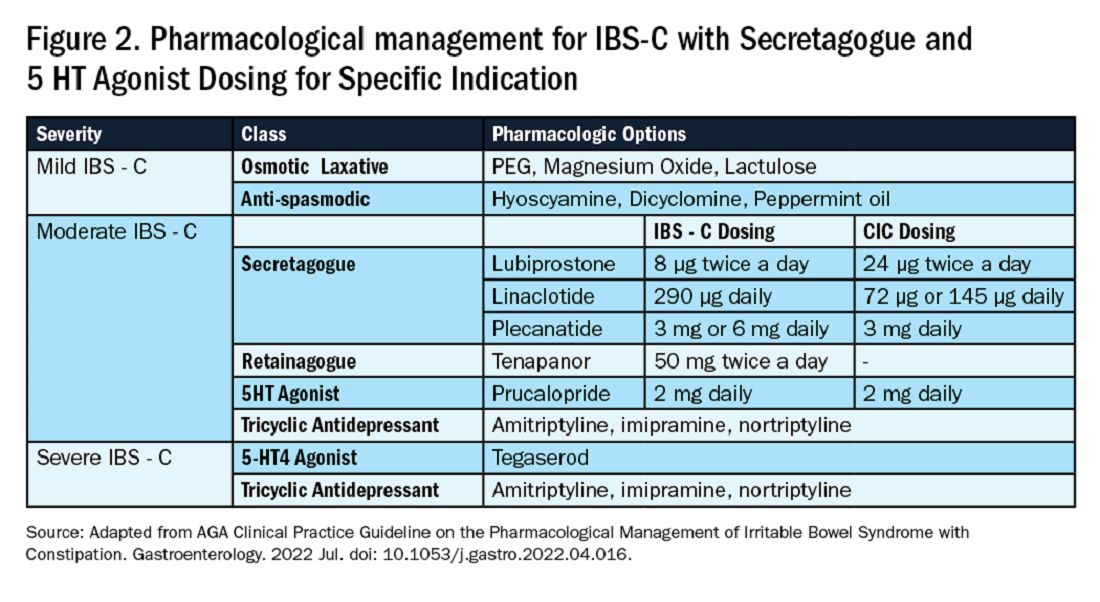

If these measures are inadequate, pharmacological therapy with secretagogues and 5HT agonists can be considered. Prucalopride, a selective agonist of serotonin 5-HT4 receptors, is approved for CIC, prescribed 2 mg daily.14 It can also be used in patients with global motility delays, such as gastroparetics with constipation. The mechanism of action of secretagogues and specific dosing of these medications are discussed in Figure 2.15 Vibrant is a non-pharmacologic, orally ingested, vibrating, and programmable capsule device that has recently received Food and Drug Administration approval for treatment of chronic constipation by stimulating the intestinal wall, thereby promoting colonic contractile activity to achieve more spontaneous bowel movements. Further studies are required to assess its efficacy.16 Additionally, if there is inadequate response to all the above, it would be prudent to evaluate for the presence of pelvic floor dysfunction as well.

IBS-C

Similar to CIC, treatment for mild IBS-C starts with osmotic laxatives with the additional component of pain control. Antispasmodics can be used to manage the abdominal pain, cramping, and spasms associated with IBS-C. Antispasmodics available in the United States include anticholinergic agents that cause smooth muscle relaxation, such as dicyclomine or hyoscyamine or direct smooth muscle relaxants such as peppermint oil.17 IBS-C patients with moderate symptoms may need escalation of therapy to secretagogues or 5HT agonists (see Figure 2). Secretagogues increase fluid retention in the colonic lumen to promote bowel movements and improve visceral hypersensitivity. Lubiprostone is an intestinal chloride channel activator, indicated only for adult women with IBS-C. Linaclotide and plecanatide are guanylate cyclase-C activators which increase intestinal chloride and bicarbonate secretion, and both are indicated in IBS-C and CIC. Tenapanor inhibits the sodium/hydrogen exchanger in the GI tract, leading to increased water secretion, and is recommended for IBS-C in adults who have failed secretagogues.

All four of these drugs can be considered for moderate to severe IBS-C symptoms. In the case of severe IBS-C symptoms, Tegaserod, a 5-HT4 receptor partial agonist has been approved in women under 65 without significant cardiovascular or cerebrovascular disease.18 Regardless of IBS-C symptom severity, persistent visceral hypersensitivity can be treated with low-dose neuromodulators.19 Figure 2 provides treatment recommendations for IBS-C based on symptom severity.

Opioid-Induced Constipation (OIC)

In patients with OIC, peripherally acting mu-opioid receptor antagonists such as methylnaltrexone and naloxegol can be beneficial where stimulant laxatives are insufficient. Additionally, lubiprostone is indicated in OIC in non-cancer patients. At present, there are no head-to-head trials comparing efficacy of these medications.

Defecatory Disorders

Biofeedback therapy is the cornerstone of treatment for dyssynergic defecation, focusing on neuromuscular training to restore a normal pattern of defecation by teaching patients to tense the abdomen and relax the pelvic floor muscles and anal sphincter. It retrains the body to coordinate abdominal, rectal, and anal muscles to achieve synchronous contraction to achieve complete evacuation. It also increases awareness and response to rectal fullness or the need to defecate.

Biofeedback makes patients aware of counterproductive subconscious actions such as contracting of their anal sphincter during defecation followed by simulated defecation training with focus on how to tighten abdominal muscles and relax pelvic floor muscles to initiate and complete defecation.20 This is performed in the office with a physiotherapist or trained nurse for at least six sessions or at home where patients are encouraged to perform the exercises for 20 minutes, twice a day. These sessions utilize tools such as manometry probes, electromyography probes, simulated balloon, or home biofeedback training devices to provide visual feedback while practicing abdominophrenic breathing. Biofeedback is particularly helpful in patients suffering from constipation. Patients with defecatory disorders can also benefit from pelvic floor physical therapy which focuses on strengthening the pelvic and puborectal muscles, external anal sphincter, and pelvic muscles. This is more useful in patients with fecal incontinence. Despite all these treatments, a subset of patients may still not respond and may qualify for surgical evaluation.

Conclusion

While constipation is seldom life-threatening, it has a negative impact on patient quality of life and poses a significant financial burden on our overall healthcare system. The complexity of this condition should be appreciated and understood in order for a complete and thorough evaluation. We trust that our practical guide should serve as a useful tool in the evaluation of a chronically constipated patient.

Dr. Salim (@hamsalim07 on X) is based in the Department of Internal Medicine, University of Texas Medical Branch, Galveston. Dr. Chowdhury (annicho.med on Instagram) is a fellow in the Department of Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and Nutrition, University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston. Dr. Viswanathan (@LavanyaMD on X) is Associate Professor, University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center. The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

1. Mugie S et al. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2011 Feb. doi: 10.1016/j.bpg.2010.12.010.

2. Almario CV et al. Gastroenterology. 2023 Dec. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2023.08.010.

3. Canavan C et al. Clin Epidemiol. 2014 Feb. doi: 10.2147/CLEP.S40245.

4. Rao SSC. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2007 Sep. doi: 10.1016/j.gtc.2007.07.013.

5. Bharucha AE et al. Gastroenterology. 2020 Apr. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2019.12.034.

6. Cinquetti M et al. Clin Exp Pediatr. 2021 Sep. doi: 10.3345/cep.2020.01326.

7. Shah ND et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2008 Jul. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2008.01910.x.

8. Rajindrajith S et al. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2014 Apr. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0000000000000249.

9. Talley NJ. Am J Gastroenterol. 2008 Apr. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2008.01832.x.

10. Maurer AH. J Nucl Med. 2015 Sep. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.113.134551.

11. Frye J et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2024 Aug. doi: 10.14309/ajg.0000000000002670.

12. Rao SSC et al. J Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2016 Jun. doi: 10.5056/jnm16060.

13. Chang L et al. Gastroenterology. 2023 Jun. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2023.03.214.

14. Brenner DM et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2021 Aug. doi: 10.14309/ajg.0000000000001266.

15. Chang L et al. Gastroenterology. 2022 Jul. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2022.04.016.

16. Rao SSC et al. Gastroenterology. 2023 Jun. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2023.02.013.

17. Lacy BE et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2021 Jan. doi: 10.14309/ajg.0000000000001036.

18. Anderson JL et al. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol Ther. 2009 Sep. doi: 10.1177/1074248409340158.

19. Rahimi R et al. World J Gastroenterol. 2009 Apr. doi: 10.3748/wjg.15.1548.

20. Rao SSC. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2011 Feb. doi: 10.1016/j.bpg.2011.01.004.

Introduction

Constipation affects one in six people worldwide and accounts for one third of outpatient visits.1 Chronic constipation is defined by difficult, infrequent, and/or incomplete defecation, quantified by less than three spontaneous bowel movements per week, persisting for at least 3 months. Patients may complain of straining during defecation, incomplete evacuation, hard stools (Bristol stool scale [BSS] type 1-2), and fullness or bloating. Chronic constipation can be subclassified as either a primary or secondary disorder.1,2

Primary Constipation Disorders

Primary constipation includes disorders of the colon or anorectum. This includes irritable bowel syndrome with constipation (IBS-C), chronic idiopathic constipation (CIC), slow transit constipation (STC), dyssynergic defecation, and pelvic floor disorders (see Figure 1).

IBS-C

IBS-C is a chronic disorder of the gut-brain axis with a worldwide prevalence of 1.3% and a prevalence of 6%-16% in the United States, United Kingdom, and Canada, with females more likely to seek care than males.2 The economic impact of IBS-C is estimated to be $1.5 billion–$10 billion per year in the United States alone.3 The distinguishing characteristic is abdominal pain, however IBS-C can present with a constellation of symptoms. The diagnostic paradigm has shifted from IBS being a diagnosis of exclusion to now using a positive diagnostic strategy.2 Using this Rome IV criteria, one can make the diagnosis with > 95% accuracy.2,4

CIC

CIC, previously defined as functional constipation, is a disorder defined by incomplete defecation and difficult or infrequent stool. CIC is diagnosed in patients without an underlying anatomic or structural abnormality. Rome IV Criteria helps further classify the defining characteristics of chronic idiopathic constipation.2

Slow Transit Constipation

STC is characterized by impaired colonic transit time in the absence of pelvic floor dysfunction. It presents with infrequent bowel movements, diminished urgency, and/or straining with defecation.

Defecatory Disorders: Dyssynergic Defecation and Pelvic Floor Dysfunction

Defecatory disorders (DDs) result from alterations in the colonic-neural pathway with an unclear pathogenesis. A firm understanding of colonic physiology is necessary to identify DDs. The right colon helps to store and mix stool contents, the left colon helps add water to the stool, and the anal canal and rectum enable defecation and maintain continence. Any alteration along this physiologic pathway results in DDs.5

DDs primarily develop via maladaptive pelvic floor contraction during defecation or from muscle or nerve injury and include functional outlet obstruction, anorectal dyssynergia, and pelvic floor dysfunction. Increased resistance to defecation results from anismus, paradoxical anal sphincter contraction, or incomplete relaxation of the pelvic floor and external anal sphincter. This muscle incoordination is described as dyssynergia. DDs can involve either muscle or nerve dysfunction or a combination of the two. Reduced rectal sensation caused by reduced sensory triggers can cause stasis of stool, thus propagating the cycle of constipation. Over time, excessive straining can weaken the pelvic floor, increasing the risk of excessive perineal descent, rectal intussusception, solitary rectal ulcer syndrome, and pudendal neuropathy.5 Thus, identification of DDs is crucial in patients with chronic constipation.

Secondary Constipation Disorders

Secondary constipation disorders are a result of an alternate process and warrant a thorough review of outpatient medications and past medical history. Figure 1 outlines the most common causes of secondary constipation, which span a wide differential.

Clinical Evaluation

The evaluation of constipation begins with a thorough history. Description of bowel habits should include frequency, duration, straining, stool consistency using a Bristol stool chart, complete vs incomplete evacuation, pain, bloating, and use of digital maneuvers (vaginal splinting or digital stool removal). One should inquire about back trauma/surgeries and obstetric history to include vaginal forceps injury or episiotomy.

With increased smartphone use, toilet time on average has increased and can contribute to maladaptive bowel habits.6 Patients may not realize they are constipated, so patient education is critical. A patient with daily bowel movements ranging between BSS type 1-6 with incomplete evacuation might complain of diarrhea but may in fact have constipation with overflow diarrhea, for example. Past medical history is also clinically relevant, as systemic conditions can cause secondary constipation. A constipated patient should also be asked what therapies he/she has tried prior to gastroenterology referral as primary care referrals for constipation account for 8 million visits to gastroenterology per year.7

While a sensitive topic, inquire about abuse history, especially in those with childhood constipation symptoms. There is a positive correlation between childhood constipation and physical, emotional, and sexual abuse and, for any number of reasons, your patient may be reluctant to share this or undergo a digital rectal exam (DRE).8 In such cases, be sensitive in asking for this history in private rather than with other family members around and always perform this exam with a chaperone present.

A detailed physical exam is an indispensable tool all gastroenterologists must master when evaluating a constipated patient. Some key exam findings include abdominal distention, high-pitched bowel sounds, and presence of a succussion splash indicating obstructive pathology. Dry skin and brittle hair indicate hypothyroidism while hypermobile joints and skin laxity suggest connective tissue disease. Finally, a physical examination is incomplete without a DRE.

DRE

DRE is an often-overlooked physical exam component which provides helpful insight that can guide management. An informed DRE can help identify structural disorders such as fissure, hemorrhoids, anorectal mass, fecal impaction, rectal prolapse, and excessive perineal descent syndrome.9 Unless contraindicated, DRE should be a standard part of the workup of a patient with chronic constipation.

Workup

Colonoscopy

The role of colonoscopy in chronic constipation is low yield and only indicated if alarm signs are present.2 When no organic causes can be identified, the patient is deemed to have a functional bowel or motility disorder leading to constipation.

Colonic Transit Time

Colonic transit time (CTT) can be evaluated by assessing the presence of radio-opaque sitz markers in the colon with an abdominal x-ray 5 days after ingestion. The presence of five or more sitz markers may indicate STC. However, this can also signal an obstructive defecatory disorder. Colon scintigraphy can determine whether there is diffuse colonic dysmotility or dysfunction in a specific segment of the colon.10

Anorectal Function Testing (AFT)

AFT can evaluate DDs, such as fecal incontinence, dyssynergic defecation, rectal sensory disorders, anorectal pain, and rectal prolapse. AFT comprises three tests: anorectal manometry (ARM), balloon expulsion test (BET), and rectal sensory testing. These assess the defecation, continence, and sensory mechanisms of the rectum, respectively.

ARM testing employs a thin, flexible probe with an attached sensor that is inserted into the rectum to measure internal and external sphincter pressures while at rest, squeezing, and bearing down to give a functional assessment of sphincter tone.11 Cough or party balloon test assesses continence and sphincter strength. Rectal sensation is assessed by inflating a balloon incrementally and asking the patient to indicate first sensation, urgency to defecate, and discomfort. If both ARM and BET are abnormal, the patient meets diagnostic criteria for dyssynergic defecation.12

Pelvic floor disorders can be further assessed by MR defecography or barium defecography. Barium defecography is the more widely available of the two. MR defecography is a dynamic study that directly assesses pelvic floor muscles and endopelvic fascia during various stages of defecation and considered superior. This testing modality can distinguish between functional causes such as dyssynergia or pelvic floor dysfunction and structural causes of obstruction such as rectocele, rectal prolapse, or rectal intussusception. MR defecography is helpful when dyssynergia is suggested by ARM with a normal BET or if there is an absent recto-anal inhibitory reflex on ARM, which may suggest rectal intussusception.

Management

CIC

Incorporating 20-30 g of total soluble fiber, such as psyllium in individuals with low dietary fiber intake is the first-line recommendation for CIC.13 If response to a trial of fiber supplementation is inadequate, over-the-counter (OTC) osmotic laxatives such as polyethylene glycol and magnesium oxide can be incorporated. In the event of failure of OTC osmotic laxatives, lactulose can be considered. Stimulant laxatives such as senna, bisacodyl, or sodium picosulfate can be added as an adjunctive measure for short periods of time, defined as daily for 4 weeks or less.

If these measures are inadequate, pharmacological therapy with secretagogues and 5HT agonists can be considered. Prucalopride, a selective agonist of serotonin 5-HT4 receptors, is approved for CIC, prescribed 2 mg daily.14 It can also be used in patients with global motility delays, such as gastroparetics with constipation. The mechanism of action of secretagogues and specific dosing of these medications are discussed in Figure 2.15 Vibrant is a non-pharmacologic, orally ingested, vibrating, and programmable capsule device that has recently received Food and Drug Administration approval for treatment of chronic constipation by stimulating the intestinal wall, thereby promoting colonic contractile activity to achieve more spontaneous bowel movements. Further studies are required to assess its efficacy.16 Additionally, if there is inadequate response to all the above, it would be prudent to evaluate for the presence of pelvic floor dysfunction as well.

IBS-C

Similar to CIC, treatment for mild IBS-C starts with osmotic laxatives with the additional component of pain control. Antispasmodics can be used to manage the abdominal pain, cramping, and spasms associated with IBS-C. Antispasmodics available in the United States include anticholinergic agents that cause smooth muscle relaxation, such as dicyclomine or hyoscyamine or direct smooth muscle relaxants such as peppermint oil.17 IBS-C patients with moderate symptoms may need escalation of therapy to secretagogues or 5HT agonists (see Figure 2). Secretagogues increase fluid retention in the colonic lumen to promote bowel movements and improve visceral hypersensitivity. Lubiprostone is an intestinal chloride channel activator, indicated only for adult women with IBS-C. Linaclotide and plecanatide are guanylate cyclase-C activators which increase intestinal chloride and bicarbonate secretion, and both are indicated in IBS-C and CIC. Tenapanor inhibits the sodium/hydrogen exchanger in the GI tract, leading to increased water secretion, and is recommended for IBS-C in adults who have failed secretagogues.

All four of these drugs can be considered for moderate to severe IBS-C symptoms. In the case of severe IBS-C symptoms, Tegaserod, a 5-HT4 receptor partial agonist has been approved in women under 65 without significant cardiovascular or cerebrovascular disease.18 Regardless of IBS-C symptom severity, persistent visceral hypersensitivity can be treated with low-dose neuromodulators.19 Figure 2 provides treatment recommendations for IBS-C based on symptom severity.

Opioid-Induced Constipation (OIC)

In patients with OIC, peripherally acting mu-opioid receptor antagonists such as methylnaltrexone and naloxegol can be beneficial where stimulant laxatives are insufficient. Additionally, lubiprostone is indicated in OIC in non-cancer patients. At present, there are no head-to-head trials comparing efficacy of these medications.

Defecatory Disorders

Biofeedback therapy is the cornerstone of treatment for dyssynergic defecation, focusing on neuromuscular training to restore a normal pattern of defecation by teaching patients to tense the abdomen and relax the pelvic floor muscles and anal sphincter. It retrains the body to coordinate abdominal, rectal, and anal muscles to achieve synchronous contraction to achieve complete evacuation. It also increases awareness and response to rectal fullness or the need to defecate.

Biofeedback makes patients aware of counterproductive subconscious actions such as contracting of their anal sphincter during defecation followed by simulated defecation training with focus on how to tighten abdominal muscles and relax pelvic floor muscles to initiate and complete defecation.20 This is performed in the office with a physiotherapist or trained nurse for at least six sessions or at home where patients are encouraged to perform the exercises for 20 minutes, twice a day. These sessions utilize tools such as manometry probes, electromyography probes, simulated balloon, or home biofeedback training devices to provide visual feedback while practicing abdominophrenic breathing. Biofeedback is particularly helpful in patients suffering from constipation. Patients with defecatory disorders can also benefit from pelvic floor physical therapy which focuses on strengthening the pelvic and puborectal muscles, external anal sphincter, and pelvic muscles. This is more useful in patients with fecal incontinence. Despite all these treatments, a subset of patients may still not respond and may qualify for surgical evaluation.

Conclusion

While constipation is seldom life-threatening, it has a negative impact on patient quality of life and poses a significant financial burden on our overall healthcare system. The complexity of this condition should be appreciated and understood in order for a complete and thorough evaluation. We trust that our practical guide should serve as a useful tool in the evaluation of a chronically constipated patient.

Dr. Salim (@hamsalim07 on X) is based in the Department of Internal Medicine, University of Texas Medical Branch, Galveston. Dr. Chowdhury (annicho.med on Instagram) is a fellow in the Department of Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and Nutrition, University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston. Dr. Viswanathan (@LavanyaMD on X) is Associate Professor, University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center. The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

1. Mugie S et al. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2011 Feb. doi: 10.1016/j.bpg.2010.12.010.

2. Almario CV et al. Gastroenterology. 2023 Dec. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2023.08.010.

3. Canavan C et al. Clin Epidemiol. 2014 Feb. doi: 10.2147/CLEP.S40245.

4. Rao SSC. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2007 Sep. doi: 10.1016/j.gtc.2007.07.013.

5. Bharucha AE et al. Gastroenterology. 2020 Apr. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2019.12.034.

6. Cinquetti M et al. Clin Exp Pediatr. 2021 Sep. doi: 10.3345/cep.2020.01326.

7. Shah ND et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2008 Jul. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2008.01910.x.

8. Rajindrajith S et al. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2014 Apr. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0000000000000249.

9. Talley NJ. Am J Gastroenterol. 2008 Apr. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2008.01832.x.

10. Maurer AH. J Nucl Med. 2015 Sep. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.113.134551.

11. Frye J et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2024 Aug. doi: 10.14309/ajg.0000000000002670.

12. Rao SSC et al. J Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2016 Jun. doi: 10.5056/jnm16060.

13. Chang L et al. Gastroenterology. 2023 Jun. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2023.03.214.

14. Brenner DM et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2021 Aug. doi: 10.14309/ajg.0000000000001266.

15. Chang L et al. Gastroenterology. 2022 Jul. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2022.04.016.

16. Rao SSC et al. Gastroenterology. 2023 Jun. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2023.02.013.

17. Lacy BE et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2021 Jan. doi: 10.14309/ajg.0000000000001036.

18. Anderson JL et al. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol Ther. 2009 Sep. doi: 10.1177/1074248409340158.

19. Rahimi R et al. World J Gastroenterol. 2009 Apr. doi: 10.3748/wjg.15.1548.

20. Rao SSC. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2011 Feb. doi: 10.1016/j.bpg.2011.01.004.

Introduction

Constipation affects one in six people worldwide and accounts for one third of outpatient visits.1 Chronic constipation is defined by difficult, infrequent, and/or incomplete defecation, quantified by less than three spontaneous bowel movements per week, persisting for at least 3 months. Patients may complain of straining during defecation, incomplete evacuation, hard stools (Bristol stool scale [BSS] type 1-2), and fullness or bloating. Chronic constipation can be subclassified as either a primary or secondary disorder.1,2

Primary Constipation Disorders

Primary constipation includes disorders of the colon or anorectum. This includes irritable bowel syndrome with constipation (IBS-C), chronic idiopathic constipation (CIC), slow transit constipation (STC), dyssynergic defecation, and pelvic floor disorders (see Figure 1).

IBS-C

IBS-C is a chronic disorder of the gut-brain axis with a worldwide prevalence of 1.3% and a prevalence of 6%-16% in the United States, United Kingdom, and Canada, with females more likely to seek care than males.2 The economic impact of IBS-C is estimated to be $1.5 billion–$10 billion per year in the United States alone.3 The distinguishing characteristic is abdominal pain, however IBS-C can present with a constellation of symptoms. The diagnostic paradigm has shifted from IBS being a diagnosis of exclusion to now using a positive diagnostic strategy.2 Using this Rome IV criteria, one can make the diagnosis with > 95% accuracy.2,4

CIC

CIC, previously defined as functional constipation, is a disorder defined by incomplete defecation and difficult or infrequent stool. CIC is diagnosed in patients without an underlying anatomic or structural abnormality. Rome IV Criteria helps further classify the defining characteristics of chronic idiopathic constipation.2

Slow Transit Constipation

STC is characterized by impaired colonic transit time in the absence of pelvic floor dysfunction. It presents with infrequent bowel movements, diminished urgency, and/or straining with defecation.

Defecatory Disorders: Dyssynergic Defecation and Pelvic Floor Dysfunction

Defecatory disorders (DDs) result from alterations in the colonic-neural pathway with an unclear pathogenesis. A firm understanding of colonic physiology is necessary to identify DDs. The right colon helps to store and mix stool contents, the left colon helps add water to the stool, and the anal canal and rectum enable defecation and maintain continence. Any alteration along this physiologic pathway results in DDs.5

DDs primarily develop via maladaptive pelvic floor contraction during defecation or from muscle or nerve injury and include functional outlet obstruction, anorectal dyssynergia, and pelvic floor dysfunction. Increased resistance to defecation results from anismus, paradoxical anal sphincter contraction, or incomplete relaxation of the pelvic floor and external anal sphincter. This muscle incoordination is described as dyssynergia. DDs can involve either muscle or nerve dysfunction or a combination of the two. Reduced rectal sensation caused by reduced sensory triggers can cause stasis of stool, thus propagating the cycle of constipation. Over time, excessive straining can weaken the pelvic floor, increasing the risk of excessive perineal descent, rectal intussusception, solitary rectal ulcer syndrome, and pudendal neuropathy.5 Thus, identification of DDs is crucial in patients with chronic constipation.

Secondary Constipation Disorders

Secondary constipation disorders are a result of an alternate process and warrant a thorough review of outpatient medications and past medical history. Figure 1 outlines the most common causes of secondary constipation, which span a wide differential.

Clinical Evaluation

The evaluation of constipation begins with a thorough history. Description of bowel habits should include frequency, duration, straining, stool consistency using a Bristol stool chart, complete vs incomplete evacuation, pain, bloating, and use of digital maneuvers (vaginal splinting or digital stool removal). One should inquire about back trauma/surgeries and obstetric history to include vaginal forceps injury or episiotomy.

With increased smartphone use, toilet time on average has increased and can contribute to maladaptive bowel habits.6 Patients may not realize they are constipated, so patient education is critical. A patient with daily bowel movements ranging between BSS type 1-6 with incomplete evacuation might complain of diarrhea but may in fact have constipation with overflow diarrhea, for example. Past medical history is also clinically relevant, as systemic conditions can cause secondary constipation. A constipated patient should also be asked what therapies he/she has tried prior to gastroenterology referral as primary care referrals for constipation account for 8 million visits to gastroenterology per year.7

While a sensitive topic, inquire about abuse history, especially in those with childhood constipation symptoms. There is a positive correlation between childhood constipation and physical, emotional, and sexual abuse and, for any number of reasons, your patient may be reluctant to share this or undergo a digital rectal exam (DRE).8 In such cases, be sensitive in asking for this history in private rather than with other family members around and always perform this exam with a chaperone present.

A detailed physical exam is an indispensable tool all gastroenterologists must master when evaluating a constipated patient. Some key exam findings include abdominal distention, high-pitched bowel sounds, and presence of a succussion splash indicating obstructive pathology. Dry skin and brittle hair indicate hypothyroidism while hypermobile joints and skin laxity suggest connective tissue disease. Finally, a physical examination is incomplete without a DRE.

DRE

DRE is an often-overlooked physical exam component which provides helpful insight that can guide management. An informed DRE can help identify structural disorders such as fissure, hemorrhoids, anorectal mass, fecal impaction, rectal prolapse, and excessive perineal descent syndrome.9 Unless contraindicated, DRE should be a standard part of the workup of a patient with chronic constipation.

Workup

Colonoscopy

The role of colonoscopy in chronic constipation is low yield and only indicated if alarm signs are present.2 When no organic causes can be identified, the patient is deemed to have a functional bowel or motility disorder leading to constipation.

Colonic Transit Time

Colonic transit time (CTT) can be evaluated by assessing the presence of radio-opaque sitz markers in the colon with an abdominal x-ray 5 days after ingestion. The presence of five or more sitz markers may indicate STC. However, this can also signal an obstructive defecatory disorder. Colon scintigraphy can determine whether there is diffuse colonic dysmotility or dysfunction in a specific segment of the colon.10

Anorectal Function Testing (AFT)

AFT can evaluate DDs, such as fecal incontinence, dyssynergic defecation, rectal sensory disorders, anorectal pain, and rectal prolapse. AFT comprises three tests: anorectal manometry (ARM), balloon expulsion test (BET), and rectal sensory testing. These assess the defecation, continence, and sensory mechanisms of the rectum, respectively.

ARM testing employs a thin, flexible probe with an attached sensor that is inserted into the rectum to measure internal and external sphincter pressures while at rest, squeezing, and bearing down to give a functional assessment of sphincter tone.11 Cough or party balloon test assesses continence and sphincter strength. Rectal sensation is assessed by inflating a balloon incrementally and asking the patient to indicate first sensation, urgency to defecate, and discomfort. If both ARM and BET are abnormal, the patient meets diagnostic criteria for dyssynergic defecation.12

Pelvic floor disorders can be further assessed by MR defecography or barium defecography. Barium defecography is the more widely available of the two. MR defecography is a dynamic study that directly assesses pelvic floor muscles and endopelvic fascia during various stages of defecation and considered superior. This testing modality can distinguish between functional causes such as dyssynergia or pelvic floor dysfunction and structural causes of obstruction such as rectocele, rectal prolapse, or rectal intussusception. MR defecography is helpful when dyssynergia is suggested by ARM with a normal BET or if there is an absent recto-anal inhibitory reflex on ARM, which may suggest rectal intussusception.

Management

CIC

Incorporating 20-30 g of total soluble fiber, such as psyllium in individuals with low dietary fiber intake is the first-line recommendation for CIC.13 If response to a trial of fiber supplementation is inadequate, over-the-counter (OTC) osmotic laxatives such as polyethylene glycol and magnesium oxide can be incorporated. In the event of failure of OTC osmotic laxatives, lactulose can be considered. Stimulant laxatives such as senna, bisacodyl, or sodium picosulfate can be added as an adjunctive measure for short periods of time, defined as daily for 4 weeks or less.

If these measures are inadequate, pharmacological therapy with secretagogues and 5HT agonists can be considered. Prucalopride, a selective agonist of serotonin 5-HT4 receptors, is approved for CIC, prescribed 2 mg daily.14 It can also be used in patients with global motility delays, such as gastroparetics with constipation. The mechanism of action of secretagogues and specific dosing of these medications are discussed in Figure 2.15 Vibrant is a non-pharmacologic, orally ingested, vibrating, and programmable capsule device that has recently received Food and Drug Administration approval for treatment of chronic constipation by stimulating the intestinal wall, thereby promoting colonic contractile activity to achieve more spontaneous bowel movements. Further studies are required to assess its efficacy.16 Additionally, if there is inadequate response to all the above, it would be prudent to evaluate for the presence of pelvic floor dysfunction as well.

IBS-C

Similar to CIC, treatment for mild IBS-C starts with osmotic laxatives with the additional component of pain control. Antispasmodics can be used to manage the abdominal pain, cramping, and spasms associated with IBS-C. Antispasmodics available in the United States include anticholinergic agents that cause smooth muscle relaxation, such as dicyclomine or hyoscyamine or direct smooth muscle relaxants such as peppermint oil.17 IBS-C patients with moderate symptoms may need escalation of therapy to secretagogues or 5HT agonists (see Figure 2). Secretagogues increase fluid retention in the colonic lumen to promote bowel movements and improve visceral hypersensitivity. Lubiprostone is an intestinal chloride channel activator, indicated only for adult women with IBS-C. Linaclotide and plecanatide are guanylate cyclase-C activators which increase intestinal chloride and bicarbonate secretion, and both are indicated in IBS-C and CIC. Tenapanor inhibits the sodium/hydrogen exchanger in the GI tract, leading to increased water secretion, and is recommended for IBS-C in adults who have failed secretagogues.

All four of these drugs can be considered for moderate to severe IBS-C symptoms. In the case of severe IBS-C symptoms, Tegaserod, a 5-HT4 receptor partial agonist has been approved in women under 65 without significant cardiovascular or cerebrovascular disease.18 Regardless of IBS-C symptom severity, persistent visceral hypersensitivity can be treated with low-dose neuromodulators.19 Figure 2 provides treatment recommendations for IBS-C based on symptom severity.

Opioid-Induced Constipation (OIC)

In patients with OIC, peripherally acting mu-opioid receptor antagonists such as methylnaltrexone and naloxegol can be beneficial where stimulant laxatives are insufficient. Additionally, lubiprostone is indicated in OIC in non-cancer patients. At present, there are no head-to-head trials comparing efficacy of these medications.

Defecatory Disorders

Biofeedback therapy is the cornerstone of treatment for dyssynergic defecation, focusing on neuromuscular training to restore a normal pattern of defecation by teaching patients to tense the abdomen and relax the pelvic floor muscles and anal sphincter. It retrains the body to coordinate abdominal, rectal, and anal muscles to achieve synchronous contraction to achieve complete evacuation. It also increases awareness and response to rectal fullness or the need to defecate.

Biofeedback makes patients aware of counterproductive subconscious actions such as contracting of their anal sphincter during defecation followed by simulated defecation training with focus on how to tighten abdominal muscles and relax pelvic floor muscles to initiate and complete defecation.20 This is performed in the office with a physiotherapist or trained nurse for at least six sessions or at home where patients are encouraged to perform the exercises for 20 minutes, twice a day. These sessions utilize tools such as manometry probes, electromyography probes, simulated balloon, or home biofeedback training devices to provide visual feedback while practicing abdominophrenic breathing. Biofeedback is particularly helpful in patients suffering from constipation. Patients with defecatory disorders can also benefit from pelvic floor physical therapy which focuses on strengthening the pelvic and puborectal muscles, external anal sphincter, and pelvic muscles. This is more useful in patients with fecal incontinence. Despite all these treatments, a subset of patients may still not respond and may qualify for surgical evaluation.

Conclusion

While constipation is seldom life-threatening, it has a negative impact on patient quality of life and poses a significant financial burden on our overall healthcare system. The complexity of this condition should be appreciated and understood in order for a complete and thorough evaluation. We trust that our practical guide should serve as a useful tool in the evaluation of a chronically constipated patient.

Dr. Salim (@hamsalim07 on X) is based in the Department of Internal Medicine, University of Texas Medical Branch, Galveston. Dr. Chowdhury (annicho.med on Instagram) is a fellow in the Department of Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and Nutrition, University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston. Dr. Viswanathan (@LavanyaMD on X) is Associate Professor, University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center. The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

1. Mugie S et al. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2011 Feb. doi: 10.1016/j.bpg.2010.12.010.

2. Almario CV et al. Gastroenterology. 2023 Dec. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2023.08.010.

3. Canavan C et al. Clin Epidemiol. 2014 Feb. doi: 10.2147/CLEP.S40245.

4. Rao SSC. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2007 Sep. doi: 10.1016/j.gtc.2007.07.013.

5. Bharucha AE et al. Gastroenterology. 2020 Apr. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2019.12.034.

6. Cinquetti M et al. Clin Exp Pediatr. 2021 Sep. doi: 10.3345/cep.2020.01326.

7. Shah ND et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2008 Jul. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2008.01910.x.

8. Rajindrajith S et al. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2014 Apr. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0000000000000249.

9. Talley NJ. Am J Gastroenterol. 2008 Apr. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2008.01832.x.

10. Maurer AH. J Nucl Med. 2015 Sep. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.113.134551.

11. Frye J et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2024 Aug. doi: 10.14309/ajg.0000000000002670.

12. Rao SSC et al. J Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2016 Jun. doi: 10.5056/jnm16060.

13. Chang L et al. Gastroenterology. 2023 Jun. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2023.03.214.

14. Brenner DM et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2021 Aug. doi: 10.14309/ajg.0000000000001266.

15. Chang L et al. Gastroenterology. 2022 Jul. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2022.04.016.

16. Rao SSC et al. Gastroenterology. 2023 Jun. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2023.02.013.

17. Lacy BE et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2021 Jan. doi: 10.14309/ajg.0000000000001036.

18. Anderson JL et al. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol Ther. 2009 Sep. doi: 10.1177/1074248409340158.

19. Rahimi R et al. World J Gastroenterol. 2009 Apr. doi: 10.3748/wjg.15.1548.

20. Rao SSC. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2011 Feb. doi: 10.1016/j.bpg.2011.01.004.