User login

Evaluating and monitoring drug and alcohol use during child custody disputes

Alcohol or drug use is frequently reported as a factor in divorce; 10.6% of divorcing couples list it as a precipitant for the marriage dissolution, surpassed by infidelity (21.6%) and incompatibility (19.2%).1 An effective drug and alcohol evaluation and monitoring plan during a child custody dispute safeguards the well-being of the minor children and protects—as much as possible—the parenting time of drug- or alcohol-involved parents. The evaluation maneuvers discussed in this article most likely will produce a complete, fair, and transparent evaluation and monitoring plan.

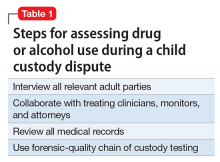

An evaluator—usually a clinician trained in diagnosing and treating a substance use disorder (SUD) and other psychiatric illnesses—performs a comprehensive alcohol/drug evaluation, prepares a monitoring program, or both. The evaluation and monitoring plan should be fair and transparent to all parties. Specific evaluation maneuvers, such as forensic-quality testing, detailed interviews with collateral informants, and ongoing collaboration with attorneys, are likely to yield a thorough evaluation and an effective and fair monitoring program. The evaluating clinician should strive for objectivity, accuracy, and practical workability when constructing these reports and monitoring plans. However, the evaluator should—in most cases—not provide treatment because this likely would represent a boundary violation between clinical treatment and forensic evaluation.

Addiction-specific evaluation maneuvers

As in all forensic matters, the evaluator’s report must answer the court’s “psycho-legal question as objectively as possible”2 rather than benefit the subject of that report. (Describing the individual being examined as the “subject” rather than “patient” emphasizes the forensic rather than clinical nature of the evaluation and the absence of a doctor–patient relationship.) Similarly, a monitoring program for drug/alcohol use should be designed to flag use of banned substances and protect the well-being of the minor child, not the parents.

Acting more as a detective than a clinician, the evaluator should maintain a skeptical—although not cynical or disrespectful—attitude when interviewing individuals who might have knowledge of the subject’s drug or alcohol use, including friends, co-workers, therapists, physicians, and even the soon-to-be-ex spouse. These collateral informants will have their own preferences or loyalties, and the examining clinician must consider these biases in the final report. A spouse often is biased and could exaggerate, emphasize, or invent addictive behaviors committed by the subject.

Collaboration among attorneys and evaluators/monitors

A strong collaboration between the judge and the attorney requesting a drug/alcohol evaluation or monitoring plan likely will result in a better outcome. This collaboration must begin with a clear delineation of the report’s purpose:

- Is the court appointing the evaluator to help gauge a drug/alcohol-involved parent’s ongoing ability to care for a child?

- Is an attorney looking for advice on how to best present the matter to the court?

- Is the evaluator expected to present and maintain a position in a court proceeding against another evaluator in a “battle of the experts?”

- Is the evaluator to consider only drug use? Only illicit drug use?

- Is the subject banned from using the substance at all times or just when she (he) is caring for the child?

A clear understanding of the evaluator’s mission is important, in part because the subject must fully comprehend the plan to consent to having the results disseminated.

To foster an effective collaboration with legal personnel the evaluator should frame the final report, testimony, and monitoring plan using clinical rather than colloquial language. To best describe the subject’s situation, diagnosis, and likely prognosis, these clinical terms often will require explanation or clarification. For example, urine drug screens (UDS) should be described as “positive for the cocaine metabolite benzoylecgonine” rather than “dirty,” and the subject might be described as “meeting criteria for alcohol use disorder” rather than an “alcoholic” or “abuser.” Using DSM-5 terminology allows for a respectful, reasonably reproducible diagnostic assessment that promotes civil discussion about disagreements, rather than name-calling in the courtroom. Professional third-party evaluation and monitoring programs in custody dispute proceedings can de-escalate the tension between the parents around issues of substance use. The conversation becomes professional, dispassionate, and focused on the best interests of the child.

Use of appropriate language allows the evaluator to expand the parameters of the report or recommend an expansion of it. If a drug/alcohol evaluation finds a relevant mental illness—in addition to a SUD—or finds another caregiver who seems incompetent, the evaluator might be professionally obligated to bring up these points, even if they are outside the purview of the requested report and monitoring plan.

Planning a monitoring program

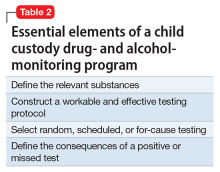

If the evaluation determines a monitoring plan is indicated and the court orders a testing program, the evaluator must design a program that accomplishes the specific goals established by the court order. The evaluator might help the court draft that plan, but the evaluator must accommodate the final court order. Table 2 lists vital aspects of a monitoring program in a child custody dispute.

Describe goals. A court-ordered monitoring program includes:

- a clear description of goals

- what specific substances are being tested for

- how and when they are being tested for

- who pays for the testing

- what will happen after a positive or missed test.

The situation will determine whether random, scheduled, or for-cause testing is indicated.

A frequent sticking point is the decision as to whether an individual can use alcohol or other substances while he (she) is not caring for the child. A person who does not meet criteria for a SUD could argue that abstinence from alcohol or any sort of testing is unwarranted when another person is taking care of the child. The evaluator should provide input, but the court will determine the outcome.

Develop a testing program. The evaluator should develop a testing program that accomplishes the goals set out by the court, usually to protect the child from possible harm caused by a parent who uses alcohol or drugs. However, this narrow goal often is expanded to allow testing for drugs/alcohol at all times, because the parent’s slip or relapse could harm the child in the long or short term.

Describe consequences. A carefully structured definition of the consequences of a positive or missed test is an important aspect of the monitoring program. In protecting the best interests of the child, the consequences usually include the immediate transfer of the child to a safe environment. This often involves the person who receives the positive test result—usually with a physician monitoring the testing—notifying the other parent or the other parent’s attorney of the positive test result.

Testing

Although an important part of evaluation and monitoring, drug and alcohol testing alone does not diagnose a SUD or even misuse.3 Adults often use alcohol with no consequence to their children, and illicit drug use is not a prima facie bar to parenthood or taking care of a child. Also, the results of a thorough alcohol or drug evaluation cannot determine the ideal custody arrangement. The court’s final decision is based on a more wide-ranging evaluation of the family system as a whole, with the drug/alcohol issue as 1 component. In addition, the court could use the results of a forensic examiner’s assessment to advocate or mandate the appropriate treatment.

With that caveat, the specific tests used and the timing of those tests are important in the context of a child custody dispute. Once the parties have agreed on the time frame of the testing (ongoing or only during visits with the child), the specific substances that are tested for must be listed. Forensic quality testing—often called “employment testing” in clinical laboratories—decreases but does not eliminate the possibility of evasion of the test. Although addiction clinicians usually request a full screen for drugs of abuse for their patients, in the legal sphere, often only the problematic substances are tested for, which are listed in the court order.

UDS, the most common test, is non-invasive, although awkward and intrusive for the subject when done with the strictest “observed” protocol. Most testing protocols do not require a “directly observed” urine collection unless there is a suspicion that the testee has substituted her (his) urine for a sample from someone else. Breath testing, although similarly non-invasive, is only useful for alcohol testing and can detect use only several hours before the test.

The urine test for the alcohol metabolites ethyl glucuronide (EtG) and ethyl sulfate (EtS) points toward alcohol use in the previous 3 days, but the test is plagued with false-positives at the lower cutoff values.8 EtG can be accurately assayed in human hair.9

Other tests. Dried blood spot testing for phosphatidylethanol is accurate in finding moderate to heavy alcohol use up to 3 weeks before the test.10 Saliva tests also can be useful for point-of-service testing, but the dearth of studies for this methodology makes it less useful in a courtroom setting. Newer technologies using handheld breathalyzers connected to a device with facial recognition software11,12 allow for random and “for-cause” alcohol testing, and can be useful in child custody negotiations. Hair sample testing, which can detect drug use over the 3 months before the test, is becoming more acceptable in the legal setting. However, hair testing cannot identify drug use 7 to 10 days before the test and does not test for alcohol13; and some questions remain regarding its reliability for different ethnic groups.14

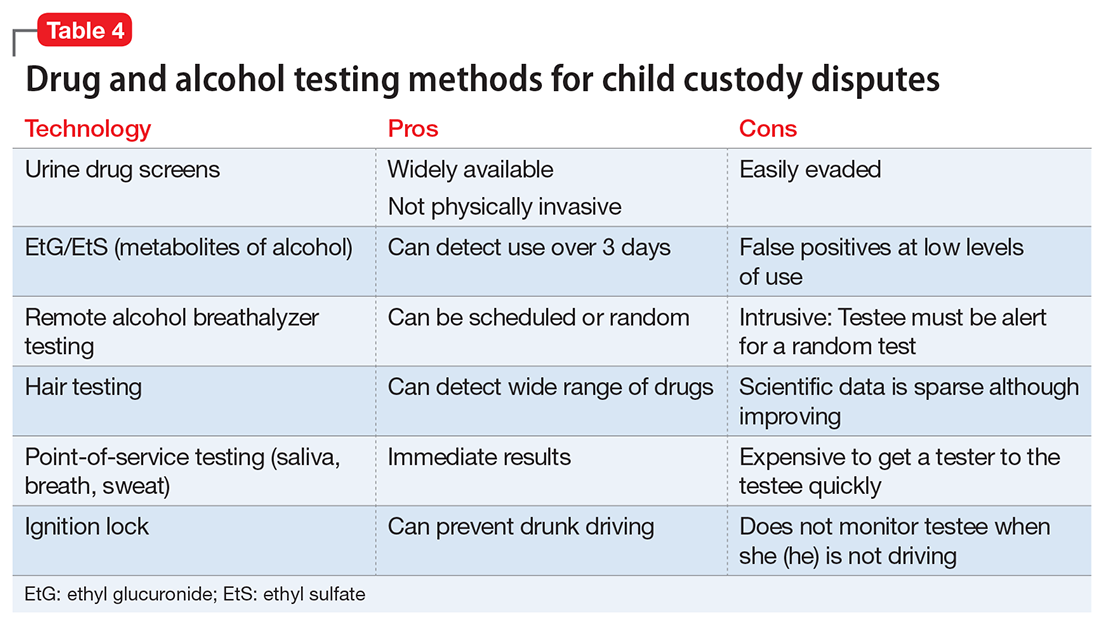

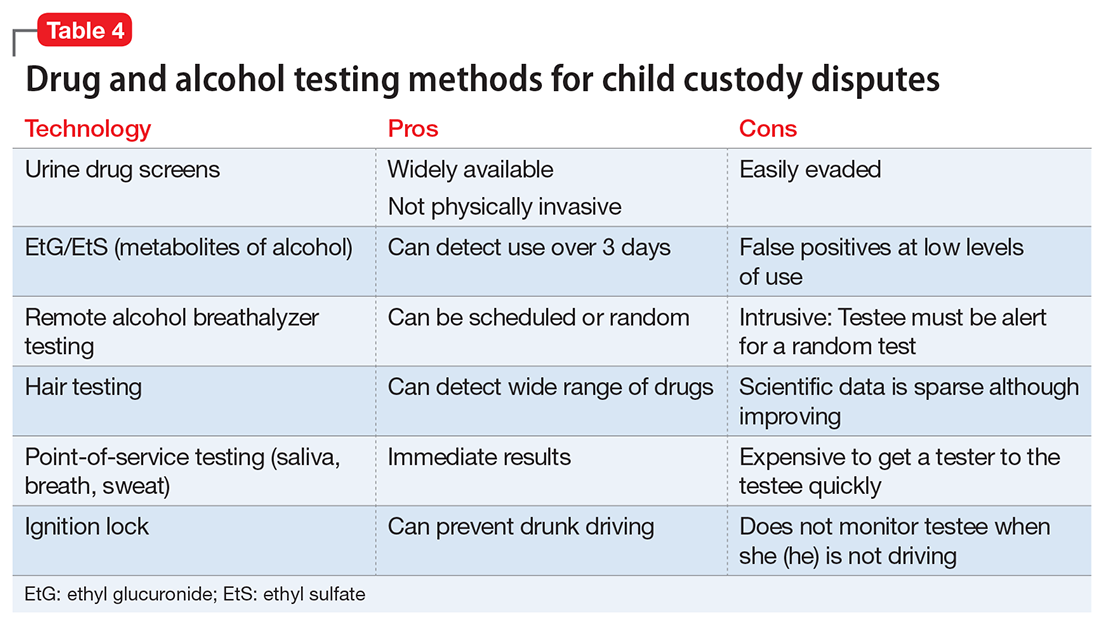

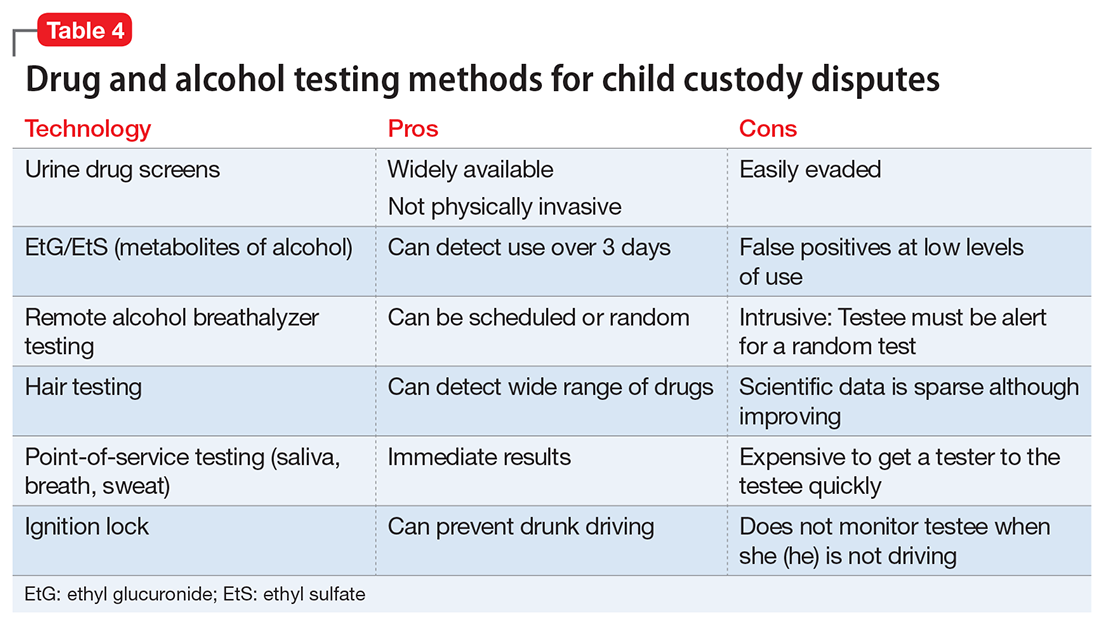

Table 4 summarizes some of the most productive testing methods for child custody disputes. Selecting the best tissue, method, and timing for testing will depend on the clinical scenario, as well as the court’s requirements. For example, negotiations between parties could result in a testing protocol that uses both random and for-cause testing of urine, breath, and hair to prove that the individual does not use any illicit substances. In a less serious clinical circumstance—or less contentious legal situation—the testing protocol may necessitate only occasional UDS to make sure that the subject is not using prohibited substances.

Practical considerations

It is important to remember that drug/alcohol evaluation and testing does not provide a clear-cut answer in child custody proceedings. Any drug or alcohol use must be evaluated under the standard used in child custody disputes: “the best interests of the child.” However, what is in the child’s best interests can be disputed in a courtroom. One California judge understood this as a process to identify the parent who can best provide the child with “… the ethical, emotional, and intellectual guidance the parent gives the child throughout his formative years, and beyond ….”15 However, in determining child custody the need for assuring the child’s physical and emotional safety overrules these long-term goals, and the parents’ emotional needs are disregarded. In a custody dispute, the conflict between parents vying for custody of their child is matched by a corresponding tension between the state’s interest in protecting a minor child while preserving an adult’s right to parent her child.

The Montana custody dispute described in Stout v Stout16 demonstrates some aspects typical of these cases. In deciding to grant custody of a then 3-year-old girl to the father, the presiding judge noted that, although the mother had completed an inpatient alcohol treatment program, her apparent unwillingness or inability to stop drinking or enroll in outpatient treatment, combined with a driving under the influence arrest while the child was in her care, were too worrisome to allow her to have physical custody of the child. The judge mentioned other factors that supported granting custody to the father, but a deciding factor was that “the evidence shows that her drinking adversely affects her parenting ability.” The judge’s ruling demonstrates his judgment in balancing the mother’s legal but harmful alcohol use with potential catastrophic effects for the child.

Although a thorough drug/alcohol evaluation, an evidence-based set of treatment recommendations, and a well-planned monitoring program all promote progress in a child custody dispute, the reality is that the clinical situation could change and all 3 aspects would have to be modified.

Manualized diagnostic rubrics and formal psychological testing, although often used in general forensic assessments, usually are not central to the drug/alcohol evaluation in a child custody dispute,17 because confirming a SUD diagnosis might not be relevant to the task of attending to the child’s best interest. Rather, the danger—or potential danger—of the subject’s substance use to the minor child is paramount, regardless of the diagnosis. Of course, an established diagnosis of a SUD might be relevant to the parent being examined, and might necessitate modifications in the testing protocol, the tissues examined, and the monitor’s overall level of skepticism about testing results.

The evaluator and monitor should be prepared to respond quickly to a slip or relapse, while remaining vigilant for exaggerated, inaccurate, or even deceitful accusations about the subject from the co-parent or others. The evaluator should assess all the relevant sources of information when performing an evaluation and use careful interviewing and testing techniques during the monitoring process. Even with this sort of deliberate evaluation and monitoring the evaluator should never assert that any testing regimen is incapable of error, and always keep in mind that the primary goal—and presumably the interest of all parties involved—is to protect the child’s well-being.

1. Amato PT, Previti D. People’s reasons for divorcing: gender, social class, the life course, and adjustment. J Fam Issues. 2003;24(5):602-606.

2. Glancy GD, Ash P, Bath EP, et al. AAPL practice guideline for the forensic assessment. J Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 2015;43(suppl 2):S3-S53.

3. Center for Substance Abuse Treatment. Drug testing in child welfare: practice and policy considerations. HHS Pub. No. (SMA) 10-4556. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; 2010.

4. Macdonald DI, DuPont RL. The role of the medical review officer. In: Graham AW, Schultz TK, eds. Principles of addiction medicine, 2nd ed. Chevy Chase, MD: American Society of Addiction Medicine; 1998:1259.

5. Swotinsky RB. The medical review officer’s manual: MROCC’s guide to drug testing. 5th ed. Beverly Farms, MA: OEM Health Information; 2015.

6. Marques PR, McKnight AS. Evaluating transdermal alcohol measuring devices. Calverton, MD: Pacific Institute for Research and Evaluation; 2007.

7. Steroidal.com. How steroid drug testing works. https://www.steroidal.com/steroid-detection-times. Accessed March 8, 2017.

8. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. The role of biomarkers in the treatment of alcohol use disorders, 2012 revision. SAMHSA Advisory. 2012;11(2):1-8.

9. United States Drug Testing Laboratories, Inc. Detection of the direct alcohol biomarker ethyl glucuronide (EtG) in hair: an annotated bibliography. http://www.usdtl.com/media/white-papers/ETG_hair_annotated_bibliography_032014.pdf. Accessed March 8, 2017.

10. Viel G, Boscolo-Berto R, Cecchetto G, et al. Phosphatidylethanol in blood as a marker of chronic alcohol use: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Mol Sci. 2012;13(11):14788-14812.

11. SoberLink. https://www.soberlink.com. Accessed March 8, 2017.

12. Scram Systems. https://www.scramsystems.com/products/scram-continuous-alcohol-monitoring/?gclid=CIqUr8Kqx9ICFZmCswodI0QKPA. Accessed March 8, 2017.

13. Swotinsky RB. The medical review officer’s manual: MROCC’s guide to drug testing. 5th ed. Beverly Farms, MA: OEM Health Information; 2015:208.

14. Chamberlain RT. Legal review for testing of drugs in hair. Forensic Sci Rev. 2007;19(1-2):85-94.

15. Marriage of Carney, 24 Cal 3d725,157 Cal Rptr 383 (1979).

16. Marriage of Stout, 216 Mont 342 (Mont 1985).

17. Hynan DJ. Child custody evaluation, new theoretical applications and research. In: Hynan DJ. Difficult evaluation challenges: domestic violence, child abuse, substance abuse, and relocations. Springfield, IL: Charles C. Thomas Publisher; 2014:178-195.

Alcohol or drug use is frequently reported as a factor in divorce; 10.6% of divorcing couples list it as a precipitant for the marriage dissolution, surpassed by infidelity (21.6%) and incompatibility (19.2%).1 An effective drug and alcohol evaluation and monitoring plan during a child custody dispute safeguards the well-being of the minor children and protects—as much as possible—the parenting time of drug- or alcohol-involved parents. The evaluation maneuvers discussed in this article most likely will produce a complete, fair, and transparent evaluation and monitoring plan.

An evaluator—usually a clinician trained in diagnosing and treating a substance use disorder (SUD) and other psychiatric illnesses—performs a comprehensive alcohol/drug evaluation, prepares a monitoring program, or both. The evaluation and monitoring plan should be fair and transparent to all parties. Specific evaluation maneuvers, such as forensic-quality testing, detailed interviews with collateral informants, and ongoing collaboration with attorneys, are likely to yield a thorough evaluation and an effective and fair monitoring program. The evaluating clinician should strive for objectivity, accuracy, and practical workability when constructing these reports and monitoring plans. However, the evaluator should—in most cases—not provide treatment because this likely would represent a boundary violation between clinical treatment and forensic evaluation.

Addiction-specific evaluation maneuvers

As in all forensic matters, the evaluator’s report must answer the court’s “psycho-legal question as objectively as possible”2 rather than benefit the subject of that report. (Describing the individual being examined as the “subject” rather than “patient” emphasizes the forensic rather than clinical nature of the evaluation and the absence of a doctor–patient relationship.) Similarly, a monitoring program for drug/alcohol use should be designed to flag use of banned substances and protect the well-being of the minor child, not the parents.

Acting more as a detective than a clinician, the evaluator should maintain a skeptical—although not cynical or disrespectful—attitude when interviewing individuals who might have knowledge of the subject’s drug or alcohol use, including friends, co-workers, therapists, physicians, and even the soon-to-be-ex spouse. These collateral informants will have their own preferences or loyalties, and the examining clinician must consider these biases in the final report. A spouse often is biased and could exaggerate, emphasize, or invent addictive behaviors committed by the subject.

Collaboration among attorneys and evaluators/monitors

A strong collaboration between the judge and the attorney requesting a drug/alcohol evaluation or monitoring plan likely will result in a better outcome. This collaboration must begin with a clear delineation of the report’s purpose:

- Is the court appointing the evaluator to help gauge a drug/alcohol-involved parent’s ongoing ability to care for a child?

- Is an attorney looking for advice on how to best present the matter to the court?

- Is the evaluator expected to present and maintain a position in a court proceeding against another evaluator in a “battle of the experts?”

- Is the evaluator to consider only drug use? Only illicit drug use?

- Is the subject banned from using the substance at all times or just when she (he) is caring for the child?

A clear understanding of the evaluator’s mission is important, in part because the subject must fully comprehend the plan to consent to having the results disseminated.

To foster an effective collaboration with legal personnel the evaluator should frame the final report, testimony, and monitoring plan using clinical rather than colloquial language. To best describe the subject’s situation, diagnosis, and likely prognosis, these clinical terms often will require explanation or clarification. For example, urine drug screens (UDS) should be described as “positive for the cocaine metabolite benzoylecgonine” rather than “dirty,” and the subject might be described as “meeting criteria for alcohol use disorder” rather than an “alcoholic” or “abuser.” Using DSM-5 terminology allows for a respectful, reasonably reproducible diagnostic assessment that promotes civil discussion about disagreements, rather than name-calling in the courtroom. Professional third-party evaluation and monitoring programs in custody dispute proceedings can de-escalate the tension between the parents around issues of substance use. The conversation becomes professional, dispassionate, and focused on the best interests of the child.

Use of appropriate language allows the evaluator to expand the parameters of the report or recommend an expansion of it. If a drug/alcohol evaluation finds a relevant mental illness—in addition to a SUD—or finds another caregiver who seems incompetent, the evaluator might be professionally obligated to bring up these points, even if they are outside the purview of the requested report and monitoring plan.

Planning a monitoring program

If the evaluation determines a monitoring plan is indicated and the court orders a testing program, the evaluator must design a program that accomplishes the specific goals established by the court order. The evaluator might help the court draft that plan, but the evaluator must accommodate the final court order. Table 2 lists vital aspects of a monitoring program in a child custody dispute.

Describe goals. A court-ordered monitoring program includes:

- a clear description of goals

- what specific substances are being tested for

- how and when they are being tested for

- who pays for the testing

- what will happen after a positive or missed test.

The situation will determine whether random, scheduled, or for-cause testing is indicated.

A frequent sticking point is the decision as to whether an individual can use alcohol or other substances while he (she) is not caring for the child. A person who does not meet criteria for a SUD could argue that abstinence from alcohol or any sort of testing is unwarranted when another person is taking care of the child. The evaluator should provide input, but the court will determine the outcome.

Develop a testing program. The evaluator should develop a testing program that accomplishes the goals set out by the court, usually to protect the child from possible harm caused by a parent who uses alcohol or drugs. However, this narrow goal often is expanded to allow testing for drugs/alcohol at all times, because the parent’s slip or relapse could harm the child in the long or short term.

Describe consequences. A carefully structured definition of the consequences of a positive or missed test is an important aspect of the monitoring program. In protecting the best interests of the child, the consequences usually include the immediate transfer of the child to a safe environment. This often involves the person who receives the positive test result—usually with a physician monitoring the testing—notifying the other parent or the other parent’s attorney of the positive test result.

Testing

Although an important part of evaluation and monitoring, drug and alcohol testing alone does not diagnose a SUD or even misuse.3 Adults often use alcohol with no consequence to their children, and illicit drug use is not a prima facie bar to parenthood or taking care of a child. Also, the results of a thorough alcohol or drug evaluation cannot determine the ideal custody arrangement. The court’s final decision is based on a more wide-ranging evaluation of the family system as a whole, with the drug/alcohol issue as 1 component. In addition, the court could use the results of a forensic examiner’s assessment to advocate or mandate the appropriate treatment.

With that caveat, the specific tests used and the timing of those tests are important in the context of a child custody dispute. Once the parties have agreed on the time frame of the testing (ongoing or only during visits with the child), the specific substances that are tested for must be listed. Forensic quality testing—often called “employment testing” in clinical laboratories—decreases but does not eliminate the possibility of evasion of the test. Although addiction clinicians usually request a full screen for drugs of abuse for their patients, in the legal sphere, often only the problematic substances are tested for, which are listed in the court order.

UDS, the most common test, is non-invasive, although awkward and intrusive for the subject when done with the strictest “observed” protocol. Most testing protocols do not require a “directly observed” urine collection unless there is a suspicion that the testee has substituted her (his) urine for a sample from someone else. Breath testing, although similarly non-invasive, is only useful for alcohol testing and can detect use only several hours before the test.

The urine test for the alcohol metabolites ethyl glucuronide (EtG) and ethyl sulfate (EtS) points toward alcohol use in the previous 3 days, but the test is plagued with false-positives at the lower cutoff values.8 EtG can be accurately assayed in human hair.9

Other tests. Dried blood spot testing for phosphatidylethanol is accurate in finding moderate to heavy alcohol use up to 3 weeks before the test.10 Saliva tests also can be useful for point-of-service testing, but the dearth of studies for this methodology makes it less useful in a courtroom setting. Newer technologies using handheld breathalyzers connected to a device with facial recognition software11,12 allow for random and “for-cause” alcohol testing, and can be useful in child custody negotiations. Hair sample testing, which can detect drug use over the 3 months before the test, is becoming more acceptable in the legal setting. However, hair testing cannot identify drug use 7 to 10 days before the test and does not test for alcohol13; and some questions remain regarding its reliability for different ethnic groups.14

Table 4 summarizes some of the most productive testing methods for child custody disputes. Selecting the best tissue, method, and timing for testing will depend on the clinical scenario, as well as the court’s requirements. For example, negotiations between parties could result in a testing protocol that uses both random and for-cause testing of urine, breath, and hair to prove that the individual does not use any illicit substances. In a less serious clinical circumstance—or less contentious legal situation—the testing protocol may necessitate only occasional UDS to make sure that the subject is not using prohibited substances.

Practical considerations

It is important to remember that drug/alcohol evaluation and testing does not provide a clear-cut answer in child custody proceedings. Any drug or alcohol use must be evaluated under the standard used in child custody disputes: “the best interests of the child.” However, what is in the child’s best interests can be disputed in a courtroom. One California judge understood this as a process to identify the parent who can best provide the child with “… the ethical, emotional, and intellectual guidance the parent gives the child throughout his formative years, and beyond ….”15 However, in determining child custody the need for assuring the child’s physical and emotional safety overrules these long-term goals, and the parents’ emotional needs are disregarded. In a custody dispute, the conflict between parents vying for custody of their child is matched by a corresponding tension between the state’s interest in protecting a minor child while preserving an adult’s right to parent her child.

The Montana custody dispute described in Stout v Stout16 demonstrates some aspects typical of these cases. In deciding to grant custody of a then 3-year-old girl to the father, the presiding judge noted that, although the mother had completed an inpatient alcohol treatment program, her apparent unwillingness or inability to stop drinking or enroll in outpatient treatment, combined with a driving under the influence arrest while the child was in her care, were too worrisome to allow her to have physical custody of the child. The judge mentioned other factors that supported granting custody to the father, but a deciding factor was that “the evidence shows that her drinking adversely affects her parenting ability.” The judge’s ruling demonstrates his judgment in balancing the mother’s legal but harmful alcohol use with potential catastrophic effects for the child.

Although a thorough drug/alcohol evaluation, an evidence-based set of treatment recommendations, and a well-planned monitoring program all promote progress in a child custody dispute, the reality is that the clinical situation could change and all 3 aspects would have to be modified.

Manualized diagnostic rubrics and formal psychological testing, although often used in general forensic assessments, usually are not central to the drug/alcohol evaluation in a child custody dispute,17 because confirming a SUD diagnosis might not be relevant to the task of attending to the child’s best interest. Rather, the danger—or potential danger—of the subject’s substance use to the minor child is paramount, regardless of the diagnosis. Of course, an established diagnosis of a SUD might be relevant to the parent being examined, and might necessitate modifications in the testing protocol, the tissues examined, and the monitor’s overall level of skepticism about testing results.

The evaluator and monitor should be prepared to respond quickly to a slip or relapse, while remaining vigilant for exaggerated, inaccurate, or even deceitful accusations about the subject from the co-parent or others. The evaluator should assess all the relevant sources of information when performing an evaluation and use careful interviewing and testing techniques during the monitoring process. Even with this sort of deliberate evaluation and monitoring the evaluator should never assert that any testing regimen is incapable of error, and always keep in mind that the primary goal—and presumably the interest of all parties involved—is to protect the child’s well-being.

Alcohol or drug use is frequently reported as a factor in divorce; 10.6% of divorcing couples list it as a precipitant for the marriage dissolution, surpassed by infidelity (21.6%) and incompatibility (19.2%).1 An effective drug and alcohol evaluation and monitoring plan during a child custody dispute safeguards the well-being of the minor children and protects—as much as possible—the parenting time of drug- or alcohol-involved parents. The evaluation maneuvers discussed in this article most likely will produce a complete, fair, and transparent evaluation and monitoring plan.

An evaluator—usually a clinician trained in diagnosing and treating a substance use disorder (SUD) and other psychiatric illnesses—performs a comprehensive alcohol/drug evaluation, prepares a monitoring program, or both. The evaluation and monitoring plan should be fair and transparent to all parties. Specific evaluation maneuvers, such as forensic-quality testing, detailed interviews with collateral informants, and ongoing collaboration with attorneys, are likely to yield a thorough evaluation and an effective and fair monitoring program. The evaluating clinician should strive for objectivity, accuracy, and practical workability when constructing these reports and monitoring plans. However, the evaluator should—in most cases—not provide treatment because this likely would represent a boundary violation between clinical treatment and forensic evaluation.

Addiction-specific evaluation maneuvers

As in all forensic matters, the evaluator’s report must answer the court’s “psycho-legal question as objectively as possible”2 rather than benefit the subject of that report. (Describing the individual being examined as the “subject” rather than “patient” emphasizes the forensic rather than clinical nature of the evaluation and the absence of a doctor–patient relationship.) Similarly, a monitoring program for drug/alcohol use should be designed to flag use of banned substances and protect the well-being of the minor child, not the parents.

Acting more as a detective than a clinician, the evaluator should maintain a skeptical—although not cynical or disrespectful—attitude when interviewing individuals who might have knowledge of the subject’s drug or alcohol use, including friends, co-workers, therapists, physicians, and even the soon-to-be-ex spouse. These collateral informants will have their own preferences or loyalties, and the examining clinician must consider these biases in the final report. A spouse often is biased and could exaggerate, emphasize, or invent addictive behaviors committed by the subject.

Collaboration among attorneys and evaluators/monitors

A strong collaboration between the judge and the attorney requesting a drug/alcohol evaluation or monitoring plan likely will result in a better outcome. This collaboration must begin with a clear delineation of the report’s purpose:

- Is the court appointing the evaluator to help gauge a drug/alcohol-involved parent’s ongoing ability to care for a child?

- Is an attorney looking for advice on how to best present the matter to the court?

- Is the evaluator expected to present and maintain a position in a court proceeding against another evaluator in a “battle of the experts?”

- Is the evaluator to consider only drug use? Only illicit drug use?

- Is the subject banned from using the substance at all times or just when she (he) is caring for the child?

A clear understanding of the evaluator’s mission is important, in part because the subject must fully comprehend the plan to consent to having the results disseminated.

To foster an effective collaboration with legal personnel the evaluator should frame the final report, testimony, and monitoring plan using clinical rather than colloquial language. To best describe the subject’s situation, diagnosis, and likely prognosis, these clinical terms often will require explanation or clarification. For example, urine drug screens (UDS) should be described as “positive for the cocaine metabolite benzoylecgonine” rather than “dirty,” and the subject might be described as “meeting criteria for alcohol use disorder” rather than an “alcoholic” or “abuser.” Using DSM-5 terminology allows for a respectful, reasonably reproducible diagnostic assessment that promotes civil discussion about disagreements, rather than name-calling in the courtroom. Professional third-party evaluation and monitoring programs in custody dispute proceedings can de-escalate the tension between the parents around issues of substance use. The conversation becomes professional, dispassionate, and focused on the best interests of the child.

Use of appropriate language allows the evaluator to expand the parameters of the report or recommend an expansion of it. If a drug/alcohol evaluation finds a relevant mental illness—in addition to a SUD—or finds another caregiver who seems incompetent, the evaluator might be professionally obligated to bring up these points, even if they are outside the purview of the requested report and monitoring plan.

Planning a monitoring program

If the evaluation determines a monitoring plan is indicated and the court orders a testing program, the evaluator must design a program that accomplishes the specific goals established by the court order. The evaluator might help the court draft that plan, but the evaluator must accommodate the final court order. Table 2 lists vital aspects of a monitoring program in a child custody dispute.

Describe goals. A court-ordered monitoring program includes:

- a clear description of goals

- what specific substances are being tested for

- how and when they are being tested for

- who pays for the testing

- what will happen after a positive or missed test.

The situation will determine whether random, scheduled, or for-cause testing is indicated.

A frequent sticking point is the decision as to whether an individual can use alcohol or other substances while he (she) is not caring for the child. A person who does not meet criteria for a SUD could argue that abstinence from alcohol or any sort of testing is unwarranted when another person is taking care of the child. The evaluator should provide input, but the court will determine the outcome.

Develop a testing program. The evaluator should develop a testing program that accomplishes the goals set out by the court, usually to protect the child from possible harm caused by a parent who uses alcohol or drugs. However, this narrow goal often is expanded to allow testing for drugs/alcohol at all times, because the parent’s slip or relapse could harm the child in the long or short term.

Describe consequences. A carefully structured definition of the consequences of a positive or missed test is an important aspect of the monitoring program. In protecting the best interests of the child, the consequences usually include the immediate transfer of the child to a safe environment. This often involves the person who receives the positive test result—usually with a physician monitoring the testing—notifying the other parent or the other parent’s attorney of the positive test result.

Testing

Although an important part of evaluation and monitoring, drug and alcohol testing alone does not diagnose a SUD or even misuse.3 Adults often use alcohol with no consequence to their children, and illicit drug use is not a prima facie bar to parenthood or taking care of a child. Also, the results of a thorough alcohol or drug evaluation cannot determine the ideal custody arrangement. The court’s final decision is based on a more wide-ranging evaluation of the family system as a whole, with the drug/alcohol issue as 1 component. In addition, the court could use the results of a forensic examiner’s assessment to advocate or mandate the appropriate treatment.

With that caveat, the specific tests used and the timing of those tests are important in the context of a child custody dispute. Once the parties have agreed on the time frame of the testing (ongoing or only during visits with the child), the specific substances that are tested for must be listed. Forensic quality testing—often called “employment testing” in clinical laboratories—decreases but does not eliminate the possibility of evasion of the test. Although addiction clinicians usually request a full screen for drugs of abuse for their patients, in the legal sphere, often only the problematic substances are tested for, which are listed in the court order.

UDS, the most common test, is non-invasive, although awkward and intrusive for the subject when done with the strictest “observed” protocol. Most testing protocols do not require a “directly observed” urine collection unless there is a suspicion that the testee has substituted her (his) urine for a sample from someone else. Breath testing, although similarly non-invasive, is only useful for alcohol testing and can detect use only several hours before the test.

The urine test for the alcohol metabolites ethyl glucuronide (EtG) and ethyl sulfate (EtS) points toward alcohol use in the previous 3 days, but the test is plagued with false-positives at the lower cutoff values.8 EtG can be accurately assayed in human hair.9

Other tests. Dried blood spot testing for phosphatidylethanol is accurate in finding moderate to heavy alcohol use up to 3 weeks before the test.10 Saliva tests also can be useful for point-of-service testing, but the dearth of studies for this methodology makes it less useful in a courtroom setting. Newer technologies using handheld breathalyzers connected to a device with facial recognition software11,12 allow for random and “for-cause” alcohol testing, and can be useful in child custody negotiations. Hair sample testing, which can detect drug use over the 3 months before the test, is becoming more acceptable in the legal setting. However, hair testing cannot identify drug use 7 to 10 days before the test and does not test for alcohol13; and some questions remain regarding its reliability for different ethnic groups.14

Table 4 summarizes some of the most productive testing methods for child custody disputes. Selecting the best tissue, method, and timing for testing will depend on the clinical scenario, as well as the court’s requirements. For example, negotiations between parties could result in a testing protocol that uses both random and for-cause testing of urine, breath, and hair to prove that the individual does not use any illicit substances. In a less serious clinical circumstance—or less contentious legal situation—the testing protocol may necessitate only occasional UDS to make sure that the subject is not using prohibited substances.

Practical considerations

It is important to remember that drug/alcohol evaluation and testing does not provide a clear-cut answer in child custody proceedings. Any drug or alcohol use must be evaluated under the standard used in child custody disputes: “the best interests of the child.” However, what is in the child’s best interests can be disputed in a courtroom. One California judge understood this as a process to identify the parent who can best provide the child with “… the ethical, emotional, and intellectual guidance the parent gives the child throughout his formative years, and beyond ….”15 However, in determining child custody the need for assuring the child’s physical and emotional safety overrules these long-term goals, and the parents’ emotional needs are disregarded. In a custody dispute, the conflict between parents vying for custody of their child is matched by a corresponding tension between the state’s interest in protecting a minor child while preserving an adult’s right to parent her child.

The Montana custody dispute described in Stout v Stout16 demonstrates some aspects typical of these cases. In deciding to grant custody of a then 3-year-old girl to the father, the presiding judge noted that, although the mother had completed an inpatient alcohol treatment program, her apparent unwillingness or inability to stop drinking or enroll in outpatient treatment, combined with a driving under the influence arrest while the child was in her care, were too worrisome to allow her to have physical custody of the child. The judge mentioned other factors that supported granting custody to the father, but a deciding factor was that “the evidence shows that her drinking adversely affects her parenting ability.” The judge’s ruling demonstrates his judgment in balancing the mother’s legal but harmful alcohol use with potential catastrophic effects for the child.

Although a thorough drug/alcohol evaluation, an evidence-based set of treatment recommendations, and a well-planned monitoring program all promote progress in a child custody dispute, the reality is that the clinical situation could change and all 3 aspects would have to be modified.

Manualized diagnostic rubrics and formal psychological testing, although often used in general forensic assessments, usually are not central to the drug/alcohol evaluation in a child custody dispute,17 because confirming a SUD diagnosis might not be relevant to the task of attending to the child’s best interest. Rather, the danger—or potential danger—of the subject’s substance use to the minor child is paramount, regardless of the diagnosis. Of course, an established diagnosis of a SUD might be relevant to the parent being examined, and might necessitate modifications in the testing protocol, the tissues examined, and the monitor’s overall level of skepticism about testing results.

The evaluator and monitor should be prepared to respond quickly to a slip or relapse, while remaining vigilant for exaggerated, inaccurate, or even deceitful accusations about the subject from the co-parent or others. The evaluator should assess all the relevant sources of information when performing an evaluation and use careful interviewing and testing techniques during the monitoring process. Even with this sort of deliberate evaluation and monitoring the evaluator should never assert that any testing regimen is incapable of error, and always keep in mind that the primary goal—and presumably the interest of all parties involved—is to protect the child’s well-being.

1. Amato PT, Previti D. People’s reasons for divorcing: gender, social class, the life course, and adjustment. J Fam Issues. 2003;24(5):602-606.

2. Glancy GD, Ash P, Bath EP, et al. AAPL practice guideline for the forensic assessment. J Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 2015;43(suppl 2):S3-S53.

3. Center for Substance Abuse Treatment. Drug testing in child welfare: practice and policy considerations. HHS Pub. No. (SMA) 10-4556. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; 2010.

4. Macdonald DI, DuPont RL. The role of the medical review officer. In: Graham AW, Schultz TK, eds. Principles of addiction medicine, 2nd ed. Chevy Chase, MD: American Society of Addiction Medicine; 1998:1259.

5. Swotinsky RB. The medical review officer’s manual: MROCC’s guide to drug testing. 5th ed. Beverly Farms, MA: OEM Health Information; 2015.

6. Marques PR, McKnight AS. Evaluating transdermal alcohol measuring devices. Calverton, MD: Pacific Institute for Research and Evaluation; 2007.

7. Steroidal.com. How steroid drug testing works. https://www.steroidal.com/steroid-detection-times. Accessed March 8, 2017.

8. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. The role of biomarkers in the treatment of alcohol use disorders, 2012 revision. SAMHSA Advisory. 2012;11(2):1-8.

9. United States Drug Testing Laboratories, Inc. Detection of the direct alcohol biomarker ethyl glucuronide (EtG) in hair: an annotated bibliography. http://www.usdtl.com/media/white-papers/ETG_hair_annotated_bibliography_032014.pdf. Accessed March 8, 2017.

10. Viel G, Boscolo-Berto R, Cecchetto G, et al. Phosphatidylethanol in blood as a marker of chronic alcohol use: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Mol Sci. 2012;13(11):14788-14812.

11. SoberLink. https://www.soberlink.com. Accessed March 8, 2017.

12. Scram Systems. https://www.scramsystems.com/products/scram-continuous-alcohol-monitoring/?gclid=CIqUr8Kqx9ICFZmCswodI0QKPA. Accessed March 8, 2017.

13. Swotinsky RB. The medical review officer’s manual: MROCC’s guide to drug testing. 5th ed. Beverly Farms, MA: OEM Health Information; 2015:208.

14. Chamberlain RT. Legal review for testing of drugs in hair. Forensic Sci Rev. 2007;19(1-2):85-94.

15. Marriage of Carney, 24 Cal 3d725,157 Cal Rptr 383 (1979).

16. Marriage of Stout, 216 Mont 342 (Mont 1985).

17. Hynan DJ. Child custody evaluation, new theoretical applications and research. In: Hynan DJ. Difficult evaluation challenges: domestic violence, child abuse, substance abuse, and relocations. Springfield, IL: Charles C. Thomas Publisher; 2014:178-195.

1. Amato PT, Previti D. People’s reasons for divorcing: gender, social class, the life course, and adjustment. J Fam Issues. 2003;24(5):602-606.

2. Glancy GD, Ash P, Bath EP, et al. AAPL practice guideline for the forensic assessment. J Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 2015;43(suppl 2):S3-S53.

3. Center for Substance Abuse Treatment. Drug testing in child welfare: practice and policy considerations. HHS Pub. No. (SMA) 10-4556. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; 2010.

4. Macdonald DI, DuPont RL. The role of the medical review officer. In: Graham AW, Schultz TK, eds. Principles of addiction medicine, 2nd ed. Chevy Chase, MD: American Society of Addiction Medicine; 1998:1259.

5. Swotinsky RB. The medical review officer’s manual: MROCC’s guide to drug testing. 5th ed. Beverly Farms, MA: OEM Health Information; 2015.

6. Marques PR, McKnight AS. Evaluating transdermal alcohol measuring devices. Calverton, MD: Pacific Institute for Research and Evaluation; 2007.

7. Steroidal.com. How steroid drug testing works. https://www.steroidal.com/steroid-detection-times. Accessed March 8, 2017.

8. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. The role of biomarkers in the treatment of alcohol use disorders, 2012 revision. SAMHSA Advisory. 2012;11(2):1-8.

9. United States Drug Testing Laboratories, Inc. Detection of the direct alcohol biomarker ethyl glucuronide (EtG) in hair: an annotated bibliography. http://www.usdtl.com/media/white-papers/ETG_hair_annotated_bibliography_032014.pdf. Accessed March 8, 2017.

10. Viel G, Boscolo-Berto R, Cecchetto G, et al. Phosphatidylethanol in blood as a marker of chronic alcohol use: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Mol Sci. 2012;13(11):14788-14812.

11. SoberLink. https://www.soberlink.com. Accessed March 8, 2017.

12. Scram Systems. https://www.scramsystems.com/products/scram-continuous-alcohol-monitoring/?gclid=CIqUr8Kqx9ICFZmCswodI0QKPA. Accessed March 8, 2017.

13. Swotinsky RB. The medical review officer’s manual: MROCC’s guide to drug testing. 5th ed. Beverly Farms, MA: OEM Health Information; 2015:208.

14. Chamberlain RT. Legal review for testing of drugs in hair. Forensic Sci Rev. 2007;19(1-2):85-94.

15. Marriage of Carney, 24 Cal 3d725,157 Cal Rptr 383 (1979).

16. Marriage of Stout, 216 Mont 342 (Mont 1985).

17. Hynan DJ. Child custody evaluation, new theoretical applications and research. In: Hynan DJ. Difficult evaluation challenges: domestic violence, child abuse, substance abuse, and relocations. Springfield, IL: Charles C. Thomas Publisher; 2014:178-195.

Teachable moments: Turning alcohol and drug emergencies into catalysts for change

Mrs. R, age 43, is agitated and confused, and her husband has brought her to the hospital’s emergency department. He reports that she has a history of denying alcohol abuse and told him during an argument yesterday that she could stop drinking any time she wanted to.

You are the psychiatrist on call. As the emergency medical team treats the apparent withdrawal episode, you tell Mrs. R’s husband: “We’ll take good care of your wife because alcohol withdrawal is dangerous and painful. But after detoxification, it’s important to prevent her from getting sick again. She needs to enter a rehabilitation program, and then outpatient treatment. When she comes around, maybe you could remind her about how much pain she was in and bring her to the rehab center yourself…”

Addicts face potentially life-threatening consequences from their behavior, which—when handled skillfully in the emergency room—can start them on the road to recovery. Some say the addict must “hit bottom” before making the changes necessary for a sober life. You can help the addict define his or her bottom as an unpleasant trip to the hospital—instead of death or loss of a job or spouse—by realistically assessing the physical consequences of continued drug or alcohol use (Table 1).

Emergencies related to alcohol or drug use accounted for 601,563 visits to U.S. emergency departments in 2000, according to the government-sponsored Drug Abuse Warning Network (DAWN).2 Alcohol in combination with any illegal or illicit drug accounted for 34% of emergency visits, cocaine for 29%, and heroin for 16%.

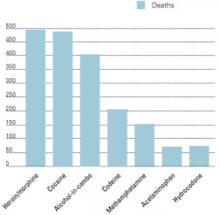

Mortality rates vary by region. In Los Angeles, for instance, heroin and cocaine each caused approximately the same number of deaths when compared with alcohol in combination (Figure).3 Most deaths (73%) were considered accidental/unexpected, with 19% coded as suicide. New York City showed similar percentages of deaths called accidental/unexpected, but heroin as the cause of death ran a distant fourth to cocaine alone, narcotic analgesics alone, and alcohol in combination.2

Addiction crises bring more than a half-million Americans to hospital emergency rooms each year (Box 1,Figure).2,3 This article describes teachable moments—suicide attempts, accidental overdose, intoxication, and withdrawal—that you can use to bundle acute treatment with referral for addiction treatment.

Suicide

Suicide is the addict’s most immediate life-threatening emergency. Psychiatric and addictive disorders often coexist,4 but some substances can trigger suicidal behavior even in the absence of another diagnosable psychiatric disorder. The addicted person who jumps off a roof, believing he can fly, may think perfectly clearly when not using crack cocaine.

Addiction to any substance greatly increases the risk for suicide. An alcohol-dependent person is 32 times more likely to commit suicide than the nonaddicted individual.5 And the suicidal addict often has the means to end his life when he feels most suicidal.

Figure DRUG-RELATED DEATHS IN LOS ANGELES, 20022

Diagnosing and treating suicidality require a high degree of vigilance for subtle clues of suicidal behavior. Because suicide risk has no pathognomonic signs, clinical judgment is required. Though addiction itself can be viewed as a slow form of suicide,6 signs that suggest an immediate threat to life include:

- the addict’s assertion that he intends to kill himself

- serious comorbid mental illness (psychosis, depression)7

- prior suicide attempts

- hopelessness.8

Some addicts feign suicidal thoughts or use them as a cry for help. Any mention or hint regarding suicide marks a severely disturbed patient who needs a complete psychiatric evaluation. This includes a formal mental status examination and exploring whether the patient has access to lethal means.

We cannot consistently predict our patients’ behavior, but a careful examination often reveals the seriousness of a suicidal threat, method, and intention, as well as support systems for keeping the patient safe. Consulting with a colleague can offer a “fresh look,” allowing two clinicians to balance the need for treatment against concerns such as bed availability and possible malingering.

Table 1

EMERGENCY AND LONG-TERM MEDICAL CONSEQUENCES OF ADDICTION

| Addictive substance | Intoxication symptoms | Withdrawal symptoms | Longer-term problems |

|---|---|---|---|

| Alcohol | Slowed respiration, impaired thinking and coordination, coma, death | Seizures, death | Dementia, liver damage |

| Barbiturates | Slowed respiration, impaired thinking and coordination, coma, death | Seizures | Rebound pain, hepatotoxicity |

| Benzodiazepines | Slowed respiration, impaired thinking and coordination | Seizures | |

| Hallucinogens | Paranoia, impaired thinking and coordination | Amotivational syndrome; possession is grounds for arrest | |

| MDMA(‘ecstasy’) | Impaired thinking and coordination, stroke, hyperthymia, dehydration, death | Cognitive impairment; possession is grounds for arrest | |

| Nicotine | Tachycardia, arrhythmia | Lung cancer, chronic-obstructive pulmonary disease | |

| Opiates | Slowed respiration, impaired thinking and coordination, coma, death | Skin infections, HIV, hepatitis (if injected); possession is grounds for arrest | |

| Phencyclidine (PCP, ‘angel dust’) | Impaired thinking and coordination, violent behavior | Possession is grounds for arrest | |

| Stimulants | Impaired thinking and coordination, myocardial infarction, stroke | Nasal damage (if snorted); skin infections, HIV, hepatitis (if injected); possession is grounds for arrest | |

| Inhalants | Impaired thinking and coordination, headache, coma | Neurologic damage |

Suicidal thoughts are unassailable grounds for comprehensive evaluation and treatment—regardless of the suicide evaluation’s outcome. The addict who even hints at suicide should undergo a thorough medical and psychiatric evaluation and then engage in whatever treatment is indicated.

Emphasize the seriousness of suicidal thoughts to the patient, his family, third-party payers, and whomever else has influence in bringing the patient to treatment. Suicidal behaviors or intentions remain one of the few legal justifications for involuntary hospitalization.

Accidental overdose

An accidental overdose provides another teachable moment to convince the addict to enter treatment. Patients who try to make a statement by overdosing on a substance they consider benign, such as oxycodone with acetaminophen, can inadvertently kill or badly injure themselves. Conversely, patients who clearly intend to harm themselves may misconstrue a substance’s lethality and ingest a large amount of a relatively nonlethal substance such as clonazepam. Either case:

- is a true psychiatric emergency

- bodes poorly for the patient’s future

- provides a strong rationale for addiction treatment.

Whether the means or the intent were deadly or benign, the overdose can be used as a convincing argument for treatment.

Intoxication

Intoxication with any addictive substance impairs judgment and increases the danger of injury. Specific medical dangers include alcohol’s powerful CNS depression in the nontolerant individual and the possibility for heart attack and stroke in the cocaine-intoxicated patient.

Attempts to convince an intoxicated person of the need for addiction treatment are usually futile. But the acute treatment represents a golden opportunity to reach out to friends and family members, who often escort the intoxicated addict to the emergency room. A medical record documenting the patient’s impaired behavior serves as evidence for (later) convincing the addict to go into treatment or for legal coercion of that treatment.

Table 2

MANAGING SYMPTOMS OF ALCOHOL WITHDRAWAL AND DELIRIUM TREMENS

| Alcohol withdrawal | Delirium tremens |

|---|---|

| Begins 4 hours to 2 days after cessation of alcohol or precipitous drop in blood alcohol level | Begins 1 to 2 days after cessation of alcohol or precipitous drop in blood alcohol level |

| Symptoms | Symptoms |

| Anxiety Agitation Tremor Autonomic instability Insomnia Confusion | Agitation Severe autonomic instability Seizure Severe confusion Hallucinations |

| Treatment Treatment of co-occurring medical illness Parenteral thiamine Tapering doses of CNS depressants, most often benzodiazepines | |

Withdrawal

Withdrawal, like intoxication, presents emergency conditions specific to the abused substance. Unlike the intoxicated patient, however, a patient experiencing the unpleasant symptoms of withdrawal may understand the need for addiction treatment. Because alcohol withdrawal often requires sedative/hypnotic treatment, the wise clinician can design a treatment plan that combines the anti-withdrawal medication with:

- attending Alcoholics Anonymous meetings

- taking disulfiram 12 hours after the last alcohol use and then daily

- and participation in relapse prevention psychotherapy.

Emergency treatments

Psychiatrists often have close contact with addicted patients in the hospital, clinic, or emergency department and therefore need to be familiar with basic techniques for managing addiction emergencies. Although addiction-trained psychiatrists manage emergencies at many institutions, general psychiatrists who have learned the following guidelines can form quick and solid therapeutic alliances with their addicted patients in the emergency department.

Alcohol

People live dangerously when intoxicated; about 40% of fatal U.S. car accidents involve a drunken driver.9 Alcohol also can incite physical violence and self-damaging sexual behavior and cause respiratory depression and death.

Acute effects of alcohol intoxication must be treated while guarding against potentially lethal withdrawal. Dangerous intoxication states with respiratory compromise may require aggressive supportive care, including intubation and mechanical ventilation. For agitated, intoxicated persons who represent a threat to themselves or others, chemical sedation with benzodiazepines—as opposed to physical restraint—is the preferred treatment.

Alcohol withdrawal requires immediate, definitive treatment (Table 2). Although mild withdrawal is common among alcoholics who cut back on or abruptly stop drinking, it can devolve quickly into delirium tremens (DTs). Serious medical problems—including severe autonomic instability and seizures—occur with DTs, which are associated with mortality rates of 5 to 15%.10 The adroit emergency department clinician can use the alcohol withdrawal/delirium episode to encourage the patient to begin addiction treatment (Box 2).11

Cocaine

Stimulants—most commonly cocaine and smoked methamphetamine—can cause myocardial infarction, cardiac arrhythmia, cerebral hemorrhage, hyperpyrexia, and status epilepticus.12 These emergencies occurring in a young person indicate the need to screen for cocaine use. Because no antidote exists for stimulant intoxication, we can only deliver supportive care while remaining vigilant for other sequelae of stimulant use, such as agitation and hypertension.13

Opiates

Overdoses leading to coma and death are the most devastating physical consequence of opiate abuse. Contrary to popular belief, orally ingested and inhaled opiates can depress respiration enough to cause death, just as injected opiates can. Because even appropriately prescribed opioid medications can lead to overdose or addiction, emergency treaters should be prepared to refer patients for pain management.

High-potency heroin often causes overdose in the novice user or in the addict who is surprised by a sudden increase in the heroin’s purity. Adulterants used by dealers to “cut” heroin also can cause illness and death. Quinine, for instance, can cause cardiac arrhythmias. Contaminants such as fentanyl and cholinergic agents such as scopolamine added to enhance the “high” associated with heroin can increase the risk of toxicity or death.

Opioid overdose is characterized by cyanosis and pulmonary edema: slowed breathing, altered mental status, blue lips and fingernail beds, pinpoint pupils, hypothermia, and gasping respirations. In addition to respiratory and cardiac support, treatment with the narcotic antagonist naloxone immediately reverses opioid overdose.

To what level of care should you refer the addicted patient from the emergency department—an inpatient medical unit, psychiatric unit/detoxification facility, residential treatment, partial hospitalization, or other model of care? The American Society of Addiction Medicine (ASAM) manual lists disposition recommendations to match individual patients’ clinical criteria. The criteria and levels are listed here as reminders of the issues involved in referring the addicted patient.

ASAM patient criteria

- Alcohol intoxication and/or withdrawal potential

- Biomedical conditions and complications

- Emotional, behavioral, or cognitive conditions and complications

- Readiness to change

- Relapse, continued use, or continued problem potential

- Recovery environment

ASAM levels of care

- Early intervention

- Opioid maintenance therapy

- Outpatient treatment

- Intensive outpatient treatment

- Partial hospitalization

- Clinically managed low-intensity residential services

- Clinically managed high-intensity residential services

- Medically monitored intensive inpatient treatment

- Medically managed intensive inpatient treatment

Source: Mee-Lee D, Shulman GD, Fishman M, et al. ASAM patient placement criteria for the treatment of substance-related disorders (2nd ed, rev). Chevy Chase, MD: American Society of Addiction Medicine, 2001:27-33.

Ecstasy

The drug 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA)—also known as Ecstasy, X, and XTC3 —provokes release of dopamine and serotonin into the synapse, causing a sense of blissful open-mindedness, closeness to others, and the ability to “break down (mental) barriers.”14 In the context of “rave” dance parties, MDMA also causes dehydration and hyperthermia, which can lead to rhabdomyolysis, kidney failure, and death.

Life-threatening consequences generally occur only when adequate water is unavailable to a group of intoxicated, dancing teenagers.15 The more common emergency presentations include sudden hypertension, tachycardia, vomiting, depersonalization, panic attacks, and psychosis.16

Immediate treatment includes restoration of normal fluid levels and body temperature, plus reassurance for the non-life-threatening, more common, presentations.

Phencyclidine

Phencyclidine (PCP) and its analogue ketamine—originally developed as anesthetic agents—are no longer used therapeutically because they can cause dissociation, anxiety, and even psychosis. Panic can change to hyperactive behavior, aggressiveness, and violent acts, so the first treatment goal must be to secure the safety of the intoxicated person and others. Chemical restraints such as benzodiazepines are preferred to physical restraints, although some situations may require physical restraint, at least initially.17

PCP affects memory, and often the user is unaware of the agent’s consequences unless he hears descriptions of his behavior from family and friends unfortunate enough to witness the intoxicated state. Coaching by emergency personnel can help the family confront the user with evidence that he needs treatment.

Barbiturates

Physicians prescribe barbiturates such as pentobarbital, phenobarbital, and secobarbital for pain, insomnia, alcohol withdrawal, and anxiety states. Although sometimes useful for acute pain, these drugs can also cause physical dependence, intoxication in overdose, withdrawal seizures, and rebound pain.18

The withdrawal associated with barbiturates—as with withdrawal from other CNS depressants such as alcohol and benzodiazepines—consists of autonomic hyperactivity, confusion, and occasionally seizures.

Overdose, often in combination with alcohol, accounts for most emergency presentations of barbiturate addiction. Supportive treatment—from reassurance and observation to airway support and mechanical ventilation—is required. Since obtundation and coma commonly occur with alcohol/barbiturate combinations, treatment includes monitoring for alcohol intoxication or withdrawal. No antidote exists for barbiturate intoxication.

Alternate medications. If the patient has become addicted to barbiturates prescribed for one of the common indications such as migraine headache, the emergency treater can promote use of a more effective treatment by acknowledging the need to control the headache pain. In managing this pain, the emergency worker can arrange referral:

- to an addiction specialist for treatment of the (now addictive) barbiturate use

- and to a neurologist who can evaluate the patient and prescribe one of many highly effective, nonaddicting headache remedies.

By taking the addiction and the pain seriously, the treater forms an alliance with the patient against the unhealthy consequences of both migraine headaches and addiction.

Benzodiazepines

Often prescribed for anxiety and insomnia, benzodiazepines cause emergency syndromes directly related to their potency, serum half-lives, and lipophilicity. For instance, alprazolam—which is potent, short-acting,19 and highly lipophilic—causes a severe withdrawal syndrome when high doses are stopped abruptly. This withdrawal state includes anxiety, agitation, and autonomic instability and can progress to frank seizures.

Withdrawal is treated by tapering the benzodiazepine dosage or substituting another benzodiazepine such as clonazepam. Benzodiazepine intoxication usually occurs only with large overdoses, although intoxication can last for days in a patient with hepatic disease. Lorazepam and oxazepam are not metabolized by the liver and can be prescribed to the patient in liver failure without causing an overdose.

Intoxication is usually treated with supportive measures and close observation for signs of withdrawal. Parenteral flumazenil immediately reverses benzodiazepine intoxication—which may assist both diagnosis and treatment—but its potential to cause seizures20 decreases this antagonist’s clinical usefulness.

Because benzodiazepine addiction often begins with prescribed medication, emergency department personnel can educate both patients and prescribers. Medications such as diazepam, lorazepam, and alprazolam are relatively safe short-term soporific agents, but use for more than a few weeks often leads to physical dependence and/or addiction. Emergency personnel can help the patient and prescriber switch to a treatment with fewer side effects and less danger of addiction.

Summary

Addicts do often change their destructive behavior when faced with increasing consequences such as job loss, relationship problems, financial difficulties, and physical deterioration. Emergencies related to drug and alcohol abuse can serve as learning experiences. Emergency department psychiatrists and other clinicians can use these crises as opportunities to help the addict:

- examine the consequences of substance use

- and change the destructive behaviors that lead to medical and social consequences.

Related resources

- American Academy of Addiction Psychiatry. www.aaap.org

- Galanter M, Kleber HD (eds). Textbook of substance abuse treatment (2nd ed). Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press, 1999.

- Graham AW, Schultz TK (eds). Principles of addiction medicine (2nd ed). Chevy Chase, MD: American Society of Addiction Medicine, Inc., 1998.

- National Clearinghouse on Alcohol and Drug Issues. www.ncadi.org

Drug brand names

- Alprazolam • Xanax

- Diazepam • Valium

- Disulfiram • Antabuse

- Flumazenil • Romazicon

- Lorazepan • Ativan

- Oxazepam • Serax

- Secobarbital • Seconal

Disclosure

Dr. Westreich reports that he serves on the speakers’ bureaus of Pfizer Inc. and Bristol-Myers Squibb Company.

1. John F. Kennedy (speech). Indianapolis: April 12, 1959.

2. Office of Applied Studies Emergency department trends from the Drug Abuse Warning Network. Preliminary estimates, January-June 2001, with revised estimates, 1994-2000. Rockville, MD: Department of Health and Human Services, February 2002:40.

3. Office of Applied Studies. Mortality data from the Drug Abuse Warning Network, 2000. Rockville, MD: Department of Health and Human Services. January 2002:56-68.

4. Rosenthal RN, Westreich L. Treatment of persons with dual diagnoses of substance use disorder and other psychological problems. In: McCrady BS, Epstein EE (eds). Addictions: a comprehensive textbook. New York: Oxford University Press, 1999;439-76.

5. Sexia FA. Criteria for the diagnosis of alcoholism. In: Estes NJ, Heinemann ME (eds). Alcoholism: development, consequences and intervention. St. Louis: CV Mosby, 1982;49-66.

6. Menninger K. Man against himself. New York: Harcourt, Brace and World, 1938:147.

7. Hirschfeld RM. When to hospitalize the addict at risk for suicide. Ann NY Acad Sci 2001;932:188-96.

8. Malone KM, Oquendo MA, Haas GL, et al. Protective factors against suicidal acts in major depression: reasons for living. Am J Psychiatry 2000;157:1084-8.

9. Sixth Special Report to the United States Congress on Alcohol and Health Rockville, MD: National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism, 1987.

10. Erwin WE, Williams DB, Speir WA. Delirium tremens. South Med J 1998;91(5):425-32.

11. Mee-Lee D, Shulman GD, Fishman M, et al. ASAM patient placement criteria for the treatment of substance-related disorders (2nd ed, rev). Chevy Chase, MD: American Society of Addiction Medicine, 2001;27-33.

12. Weiss RD, Mirin SM, Bartell RL. Cocaine (2nd ed). Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press, 1994;31-3.

13. Catravas JD, Waters IW, Walz MA, et al. Antidotes for cocaine poisoning. N Engl J Med 1977;301:1238.-

14. Stimmel B. Alcoholism, drug addiction, and the road to recovery. New York: Haworth Medical Press, 2002;142.-

15. Henry JA, Jeffreys KJ, Dawling S. Toxicity and deaths from 3,4 methylenedioxymethamphetamine (“ecstasy”). Lancet 1992;340:384-7.

16. Cohen RS. The love drug: marching to the beat of ecstasy. Binghamton, NY: Haworth Medical Press, 1998.

17. Baldridge EB, Bessen HA. Phencyclidine. Emerg Med Clin North Am 1990;8(3):541-50.

18. Silberstein SD. Drug-induced headache. Neurol Clin North Am 1998;16(1):114.-

19. Arana G, Rosenbaum JF. Handbook of psychiatric drug therapy (4th ed). New York: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2000;179.-

20. Roche Laboratories Romazicon (package insert).

Mrs. R, age 43, is agitated and confused, and her husband has brought her to the hospital’s emergency department. He reports that she has a history of denying alcohol abuse and told him during an argument yesterday that she could stop drinking any time she wanted to.

You are the psychiatrist on call. As the emergency medical team treats the apparent withdrawal episode, you tell Mrs. R’s husband: “We’ll take good care of your wife because alcohol withdrawal is dangerous and painful. But after detoxification, it’s important to prevent her from getting sick again. She needs to enter a rehabilitation program, and then outpatient treatment. When she comes around, maybe you could remind her about how much pain she was in and bring her to the rehab center yourself…”

Addicts face potentially life-threatening consequences from their behavior, which—when handled skillfully in the emergency room—can start them on the road to recovery. Some say the addict must “hit bottom” before making the changes necessary for a sober life. You can help the addict define his or her bottom as an unpleasant trip to the hospital—instead of death or loss of a job or spouse—by realistically assessing the physical consequences of continued drug or alcohol use (Table 1).

Emergencies related to alcohol or drug use accounted for 601,563 visits to U.S. emergency departments in 2000, according to the government-sponsored Drug Abuse Warning Network (DAWN).2 Alcohol in combination with any illegal or illicit drug accounted for 34% of emergency visits, cocaine for 29%, and heroin for 16%.

Mortality rates vary by region. In Los Angeles, for instance, heroin and cocaine each caused approximately the same number of deaths when compared with alcohol in combination (Figure).3 Most deaths (73%) were considered accidental/unexpected, with 19% coded as suicide. New York City showed similar percentages of deaths called accidental/unexpected, but heroin as the cause of death ran a distant fourth to cocaine alone, narcotic analgesics alone, and alcohol in combination.2

Addiction crises bring more than a half-million Americans to hospital emergency rooms each year (Box 1,Figure).2,3 This article describes teachable moments—suicide attempts, accidental overdose, intoxication, and withdrawal—that you can use to bundle acute treatment with referral for addiction treatment.

Suicide

Suicide is the addict’s most immediate life-threatening emergency. Psychiatric and addictive disorders often coexist,4 but some substances can trigger suicidal behavior even in the absence of another diagnosable psychiatric disorder. The addicted person who jumps off a roof, believing he can fly, may think perfectly clearly when not using crack cocaine.

Addiction to any substance greatly increases the risk for suicide. An alcohol-dependent person is 32 times more likely to commit suicide than the nonaddicted individual.5 And the suicidal addict often has the means to end his life when he feels most suicidal.

Figure DRUG-RELATED DEATHS IN LOS ANGELES, 20022

Diagnosing and treating suicidality require a high degree of vigilance for subtle clues of suicidal behavior. Because suicide risk has no pathognomonic signs, clinical judgment is required. Though addiction itself can be viewed as a slow form of suicide,6 signs that suggest an immediate threat to life include:

- the addict’s assertion that he intends to kill himself

- serious comorbid mental illness (psychosis, depression)7

- prior suicide attempts

- hopelessness.8

Some addicts feign suicidal thoughts or use them as a cry for help. Any mention or hint regarding suicide marks a severely disturbed patient who needs a complete psychiatric evaluation. This includes a formal mental status examination and exploring whether the patient has access to lethal means.

We cannot consistently predict our patients’ behavior, but a careful examination often reveals the seriousness of a suicidal threat, method, and intention, as well as support systems for keeping the patient safe. Consulting with a colleague can offer a “fresh look,” allowing two clinicians to balance the need for treatment against concerns such as bed availability and possible malingering.

Table 1

EMERGENCY AND LONG-TERM MEDICAL CONSEQUENCES OF ADDICTION

| Addictive substance | Intoxication symptoms | Withdrawal symptoms | Longer-term problems |

|---|---|---|---|

| Alcohol | Slowed respiration, impaired thinking and coordination, coma, death | Seizures, death | Dementia, liver damage |

| Barbiturates | Slowed respiration, impaired thinking and coordination, coma, death | Seizures | Rebound pain, hepatotoxicity |

| Benzodiazepines | Slowed respiration, impaired thinking and coordination | Seizures | |

| Hallucinogens | Paranoia, impaired thinking and coordination | Amotivational syndrome; possession is grounds for arrest | |

| MDMA(‘ecstasy’) | Impaired thinking and coordination, stroke, hyperthymia, dehydration, death | Cognitive impairment; possession is grounds for arrest | |