User login

Brazil sees first live birth from deceased-donor uterus transplant

The healthy 2,550-g infant girl was born in December 2017 via a planned cesarean delivery at about 36 weeks’ gestation. Her mother, the transplant recipient, has congenital absence of the uterus from Mayer-Rokitansky-Küster-Hauser (MRKH) syndrome. Removal of the transplanted uterus at the time of delivery allowed the woman to stop taking the immunosuppressive medications that she’d been on since the transplantation, which had been performed less than a year and a half previously.

The uterus had been retrieved from a 45-year-old donor who experienced a subarachnoid hemorrhage and subsequent brain death. The donor had three vaginal deliveries, and no history of reproductive issues or sexually transmitted infection, wrote Dani Ejzenberg, MD, and his colleagues at the University of São Paolo, Brazil.

The retrieval and transplantation procedures were done at the university’s hospital, in accordance with a research protocol approved by the university, a Brazilian national ethics committee, and the country’s national transplantation system. Thorough psychological evaluation was part of the research protocol, and the patient and her partner had monthly psychological counseling from therapists with expertise in transplant and fertility, wrote Dr. Ejzenberg and his colleagues.

In preparation for the transplantation, which occurred when the recipient was 32 years old, she had in vitro fertilization several months before the procedure. Eight “good-quality” blastocysts were retrieved and cryopreserved, said Dr. Ejzenberg and his coauthors. The recipient’s menstrual cycle resumed 37 days after transplantation, and one of the cryopreserved embryos was transferred about 7 months after the uterine transplantation procedure, resulting in the pregnancy.

The donor and recipient were matched only by ABO blood type, with no further tissue typing being done, wrote Dr. Ejzenberg and his colleagues. The immunosuppressive regimen paralleled that used in previous successful uterine transplantations from live donors in Sweden, with induction via 1 g intraoperative methylprednisolone and 1.5 mg/kg of thymoglobulin. Thereafter, the recipient received tacrolimus titrated to a trough of 8-10 ng/mL, along with mycophenolate mofetil 720 mg twice daily. Five months after her transplantation, the mycophenolate mofetil was replaced with 100 mg azathioprine and 10 mg prednisone daily, a regimen that she stayed on until cesarean delivery.

Broad-spectrum antibiotics, antifungals, and anthelmintics were administered during the patient’s hospital stay. Prophylactic antibiotics were continued for 6 months, and antiviral medication was given prophylactically for 3 months. The recipient had one episode of vaginal discharge, treated with antifungal medication, and one episode of pyelonephritis during pregnancy, treated during a brief inpatient stay.

Enoxaparin and aspirin were used for inpatient venous thromboembolism prophylaxis, and heparin and aspirin thereafter. Aspirin was discontinued at 34 weeks, and heparin the day before delivery.

Swedish and American teams involved in uterine transplantation are working to develop standardization of surgical techniques, immunosuppression protocol, and methods to monitor rejection.

However, pointed out Dr. Ejzenberg and his coauthors, some technical aspects were unique to the deceased donor transplantation. These included managing total ischemic time for the donor tissue because heart, liver, and kidney retrieval all were given priority.

One downstream effect of this was longer-than-expected procedure and anesthesia time for the recipient, because coordinating donor uterus retrieval and preparation of the surgical bed in the live recipient was tricky; surgery time was about 10.5 hours. Also, there was prolonged warm-ischemia time because six small-vessel anastomoses needed to be performed, wrote the investigators.

After reperfusion of the implanted uterus, there was brisk bleeding from a number of small vessels that had not been ligated on retrieval because of concerns about ischemic time. These were identified and sutured or cauterized, but the total estimated blood loss during the procedures was 1,200 mL, with most of that coming from the uterus, said Dr. Ejzenberg and his coauthors.

The donor uterus had a total of almost 8 hours of ischemic time, exceeding the previously published live donor maximum uterine ischemic time of 3 hours, 25 minutes. This experience can inform surgical teams considering future uterine transplantations.

Dr. Ejzenberg and his colleagues also said that they cast a broad net with immunosuppression, erring on the side of caution. With more experience may come the ability to scale back immunosuppressive regimens, they noted.

The explantation of the uterus and associated blood vessels after delivery afforded the opportunity for pathological examination of the uterus and other tissues, which showed no signs of rejection. The uterine arteries did have mild intimal fibrous hyperplasia that was likely related to the age of the donor, said Dr. Ejzenberg and his coauthors.

This successful completion of a deceased-donor uterine transplantation demonstrates the feasibility of accessing “a much wider potential donor population, as the numbers of people willing and committed to donate organs upon their own deaths are far larger than those of potential live donors,” wrote Dr. Ejzenberg and his colleagues. “Further incidental but substantial benefits of the use of deceased donors include lower costs and avoidance of live donors’ surgical risks.”

In 2011, a uterine transplantation from a deceased donor resulted in pregnancy, but ended in miscarriage.

Funding was provided by Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado de São Paulo and the Hospital das Clínicas of University of São Paulo School of Medicine. Dr. Ejzenberg and his colleagues reported that they had no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Ejzenberg D. et al. Lancet. 2018 Dec. doi: 10.1015/S0140-6736(18)31766-5.

Among the advances seen in this deceased-donor uterus transplant is a demonstration that ischemic time of nearly 8 hours – four times the average seen in live donation – does not preclude a successful transplantation.

Also, the timetable for transplantation seen here did not involve the year-long waiting period between transplantation and pregnancy that has been the norm in live uterine transplantation.

However, uterine transplantation, whether from a living or deceased donor, is still in its early stages. Among the many unsettled questions are whether live or deceased donor transplantations yield superior results. Additional technical aspects to be further studied include best surgical approach for the donor uterus, best anastomosis technique, and optimal immunosuppression and antimicrobial/antifungal/antiviral regimens.

Continued work needs to be done to standardize these and other aspects of the peri- and postoperative care of women undergoing uterine transplantation.

In addition, long-term tracking of children born from transplanted uteri is needed, so outcomes can be assessed over the lifespan.

Going forward, it could be that uterine transplantation may be offered to an expanded cohort of women, including those with bulky, nonoperable uterine fibroids, those who have received pelvic radiotherapy, and even those who have had multiple unexplained problems with implantation during fertility treatments. In all cases, researchers should work toward achieving the highest live birth rate at the lowest risk to donors and patients, while also working to make more organs available; establishing registries, and encouraging prospective registration and transparent reporting of uterus transplantation procedures.

Cesar Diaz-Garcia, MD, is medical director of IVI-London, and Antonio Pellicer, MD, is professor of obstetrics and gynecology at the University of Valencia, Spain. These remarks were drawn from their editorial accompanying the report by Ejzenberg et al. (Lancet. 2018 Dec. doi: 10.1016/50140-6736(18)32106-8).

Among the advances seen in this deceased-donor uterus transplant is a demonstration that ischemic time of nearly 8 hours – four times the average seen in live donation – does not preclude a successful transplantation.

Also, the timetable for transplantation seen here did not involve the year-long waiting period between transplantation and pregnancy that has been the norm in live uterine transplantation.

However, uterine transplantation, whether from a living or deceased donor, is still in its early stages. Among the many unsettled questions are whether live or deceased donor transplantations yield superior results. Additional technical aspects to be further studied include best surgical approach for the donor uterus, best anastomosis technique, and optimal immunosuppression and antimicrobial/antifungal/antiviral regimens.

Continued work needs to be done to standardize these and other aspects of the peri- and postoperative care of women undergoing uterine transplantation.

In addition, long-term tracking of children born from transplanted uteri is needed, so outcomes can be assessed over the lifespan.

Going forward, it could be that uterine transplantation may be offered to an expanded cohort of women, including those with bulky, nonoperable uterine fibroids, those who have received pelvic radiotherapy, and even those who have had multiple unexplained problems with implantation during fertility treatments. In all cases, researchers should work toward achieving the highest live birth rate at the lowest risk to donors and patients, while also working to make more organs available; establishing registries, and encouraging prospective registration and transparent reporting of uterus transplantation procedures.

Cesar Diaz-Garcia, MD, is medical director of IVI-London, and Antonio Pellicer, MD, is professor of obstetrics and gynecology at the University of Valencia, Spain. These remarks were drawn from their editorial accompanying the report by Ejzenberg et al. (Lancet. 2018 Dec. doi: 10.1016/50140-6736(18)32106-8).

Among the advances seen in this deceased-donor uterus transplant is a demonstration that ischemic time of nearly 8 hours – four times the average seen in live donation – does not preclude a successful transplantation.

Also, the timetable for transplantation seen here did not involve the year-long waiting period between transplantation and pregnancy that has been the norm in live uterine transplantation.

However, uterine transplantation, whether from a living or deceased donor, is still in its early stages. Among the many unsettled questions are whether live or deceased donor transplantations yield superior results. Additional technical aspects to be further studied include best surgical approach for the donor uterus, best anastomosis technique, and optimal immunosuppression and antimicrobial/antifungal/antiviral regimens.

Continued work needs to be done to standardize these and other aspects of the peri- and postoperative care of women undergoing uterine transplantation.

In addition, long-term tracking of children born from transplanted uteri is needed, so outcomes can be assessed over the lifespan.

Going forward, it could be that uterine transplantation may be offered to an expanded cohort of women, including those with bulky, nonoperable uterine fibroids, those who have received pelvic radiotherapy, and even those who have had multiple unexplained problems with implantation during fertility treatments. In all cases, researchers should work toward achieving the highest live birth rate at the lowest risk to donors and patients, while also working to make more organs available; establishing registries, and encouraging prospective registration and transparent reporting of uterus transplantation procedures.

Cesar Diaz-Garcia, MD, is medical director of IVI-London, and Antonio Pellicer, MD, is professor of obstetrics and gynecology at the University of Valencia, Spain. These remarks were drawn from their editorial accompanying the report by Ejzenberg et al. (Lancet. 2018 Dec. doi: 10.1016/50140-6736(18)32106-8).

The healthy 2,550-g infant girl was born in December 2017 via a planned cesarean delivery at about 36 weeks’ gestation. Her mother, the transplant recipient, has congenital absence of the uterus from Mayer-Rokitansky-Küster-Hauser (MRKH) syndrome. Removal of the transplanted uterus at the time of delivery allowed the woman to stop taking the immunosuppressive medications that she’d been on since the transplantation, which had been performed less than a year and a half previously.

The uterus had been retrieved from a 45-year-old donor who experienced a subarachnoid hemorrhage and subsequent brain death. The donor had three vaginal deliveries, and no history of reproductive issues or sexually transmitted infection, wrote Dani Ejzenberg, MD, and his colleagues at the University of São Paolo, Brazil.

The retrieval and transplantation procedures were done at the university’s hospital, in accordance with a research protocol approved by the university, a Brazilian national ethics committee, and the country’s national transplantation system. Thorough psychological evaluation was part of the research protocol, and the patient and her partner had monthly psychological counseling from therapists with expertise in transplant and fertility, wrote Dr. Ejzenberg and his colleagues.

In preparation for the transplantation, which occurred when the recipient was 32 years old, she had in vitro fertilization several months before the procedure. Eight “good-quality” blastocysts were retrieved and cryopreserved, said Dr. Ejzenberg and his coauthors. The recipient’s menstrual cycle resumed 37 days after transplantation, and one of the cryopreserved embryos was transferred about 7 months after the uterine transplantation procedure, resulting in the pregnancy.

The donor and recipient were matched only by ABO blood type, with no further tissue typing being done, wrote Dr. Ejzenberg and his colleagues. The immunosuppressive regimen paralleled that used in previous successful uterine transplantations from live donors in Sweden, with induction via 1 g intraoperative methylprednisolone and 1.5 mg/kg of thymoglobulin. Thereafter, the recipient received tacrolimus titrated to a trough of 8-10 ng/mL, along with mycophenolate mofetil 720 mg twice daily. Five months after her transplantation, the mycophenolate mofetil was replaced with 100 mg azathioprine and 10 mg prednisone daily, a regimen that she stayed on until cesarean delivery.

Broad-spectrum antibiotics, antifungals, and anthelmintics were administered during the patient’s hospital stay. Prophylactic antibiotics were continued for 6 months, and antiviral medication was given prophylactically for 3 months. The recipient had one episode of vaginal discharge, treated with antifungal medication, and one episode of pyelonephritis during pregnancy, treated during a brief inpatient stay.

Enoxaparin and aspirin were used for inpatient venous thromboembolism prophylaxis, and heparin and aspirin thereafter. Aspirin was discontinued at 34 weeks, and heparin the day before delivery.

Swedish and American teams involved in uterine transplantation are working to develop standardization of surgical techniques, immunosuppression protocol, and methods to monitor rejection.

However, pointed out Dr. Ejzenberg and his coauthors, some technical aspects were unique to the deceased donor transplantation. These included managing total ischemic time for the donor tissue because heart, liver, and kidney retrieval all were given priority.

One downstream effect of this was longer-than-expected procedure and anesthesia time for the recipient, because coordinating donor uterus retrieval and preparation of the surgical bed in the live recipient was tricky; surgery time was about 10.5 hours. Also, there was prolonged warm-ischemia time because six small-vessel anastomoses needed to be performed, wrote the investigators.

After reperfusion of the implanted uterus, there was brisk bleeding from a number of small vessels that had not been ligated on retrieval because of concerns about ischemic time. These were identified and sutured or cauterized, but the total estimated blood loss during the procedures was 1,200 mL, with most of that coming from the uterus, said Dr. Ejzenberg and his coauthors.

The donor uterus had a total of almost 8 hours of ischemic time, exceeding the previously published live donor maximum uterine ischemic time of 3 hours, 25 minutes. This experience can inform surgical teams considering future uterine transplantations.

Dr. Ejzenberg and his colleagues also said that they cast a broad net with immunosuppression, erring on the side of caution. With more experience may come the ability to scale back immunosuppressive regimens, they noted.

The explantation of the uterus and associated blood vessels after delivery afforded the opportunity for pathological examination of the uterus and other tissues, which showed no signs of rejection. The uterine arteries did have mild intimal fibrous hyperplasia that was likely related to the age of the donor, said Dr. Ejzenberg and his coauthors.

This successful completion of a deceased-donor uterine transplantation demonstrates the feasibility of accessing “a much wider potential donor population, as the numbers of people willing and committed to donate organs upon their own deaths are far larger than those of potential live donors,” wrote Dr. Ejzenberg and his colleagues. “Further incidental but substantial benefits of the use of deceased donors include lower costs and avoidance of live donors’ surgical risks.”

In 2011, a uterine transplantation from a deceased donor resulted in pregnancy, but ended in miscarriage.

Funding was provided by Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado de São Paulo and the Hospital das Clínicas of University of São Paulo School of Medicine. Dr. Ejzenberg and his colleagues reported that they had no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Ejzenberg D. et al. Lancet. 2018 Dec. doi: 10.1015/S0140-6736(18)31766-5.

The healthy 2,550-g infant girl was born in December 2017 via a planned cesarean delivery at about 36 weeks’ gestation. Her mother, the transplant recipient, has congenital absence of the uterus from Mayer-Rokitansky-Küster-Hauser (MRKH) syndrome. Removal of the transplanted uterus at the time of delivery allowed the woman to stop taking the immunosuppressive medications that she’d been on since the transplantation, which had been performed less than a year and a half previously.

The uterus had been retrieved from a 45-year-old donor who experienced a subarachnoid hemorrhage and subsequent brain death. The donor had three vaginal deliveries, and no history of reproductive issues or sexually transmitted infection, wrote Dani Ejzenberg, MD, and his colleagues at the University of São Paolo, Brazil.

The retrieval and transplantation procedures were done at the university’s hospital, in accordance with a research protocol approved by the university, a Brazilian national ethics committee, and the country’s national transplantation system. Thorough psychological evaluation was part of the research protocol, and the patient and her partner had monthly psychological counseling from therapists with expertise in transplant and fertility, wrote Dr. Ejzenberg and his colleagues.

In preparation for the transplantation, which occurred when the recipient was 32 years old, she had in vitro fertilization several months before the procedure. Eight “good-quality” blastocysts were retrieved and cryopreserved, said Dr. Ejzenberg and his coauthors. The recipient’s menstrual cycle resumed 37 days after transplantation, and one of the cryopreserved embryos was transferred about 7 months after the uterine transplantation procedure, resulting in the pregnancy.

The donor and recipient were matched only by ABO blood type, with no further tissue typing being done, wrote Dr. Ejzenberg and his colleagues. The immunosuppressive regimen paralleled that used in previous successful uterine transplantations from live donors in Sweden, with induction via 1 g intraoperative methylprednisolone and 1.5 mg/kg of thymoglobulin. Thereafter, the recipient received tacrolimus titrated to a trough of 8-10 ng/mL, along with mycophenolate mofetil 720 mg twice daily. Five months after her transplantation, the mycophenolate mofetil was replaced with 100 mg azathioprine and 10 mg prednisone daily, a regimen that she stayed on until cesarean delivery.

Broad-spectrum antibiotics, antifungals, and anthelmintics were administered during the patient’s hospital stay. Prophylactic antibiotics were continued for 6 months, and antiviral medication was given prophylactically for 3 months. The recipient had one episode of vaginal discharge, treated with antifungal medication, and one episode of pyelonephritis during pregnancy, treated during a brief inpatient stay.

Enoxaparin and aspirin were used for inpatient venous thromboembolism prophylaxis, and heparin and aspirin thereafter. Aspirin was discontinued at 34 weeks, and heparin the day before delivery.

Swedish and American teams involved in uterine transplantation are working to develop standardization of surgical techniques, immunosuppression protocol, and methods to monitor rejection.

However, pointed out Dr. Ejzenberg and his coauthors, some technical aspects were unique to the deceased donor transplantation. These included managing total ischemic time for the donor tissue because heart, liver, and kidney retrieval all were given priority.

One downstream effect of this was longer-than-expected procedure and anesthesia time for the recipient, because coordinating donor uterus retrieval and preparation of the surgical bed in the live recipient was tricky; surgery time was about 10.5 hours. Also, there was prolonged warm-ischemia time because six small-vessel anastomoses needed to be performed, wrote the investigators.

After reperfusion of the implanted uterus, there was brisk bleeding from a number of small vessels that had not been ligated on retrieval because of concerns about ischemic time. These were identified and sutured or cauterized, but the total estimated blood loss during the procedures was 1,200 mL, with most of that coming from the uterus, said Dr. Ejzenberg and his coauthors.

The donor uterus had a total of almost 8 hours of ischemic time, exceeding the previously published live donor maximum uterine ischemic time of 3 hours, 25 minutes. This experience can inform surgical teams considering future uterine transplantations.

Dr. Ejzenberg and his colleagues also said that they cast a broad net with immunosuppression, erring on the side of caution. With more experience may come the ability to scale back immunosuppressive regimens, they noted.

The explantation of the uterus and associated blood vessels after delivery afforded the opportunity for pathological examination of the uterus and other tissues, which showed no signs of rejection. The uterine arteries did have mild intimal fibrous hyperplasia that was likely related to the age of the donor, said Dr. Ejzenberg and his coauthors.

This successful completion of a deceased-donor uterine transplantation demonstrates the feasibility of accessing “a much wider potential donor population, as the numbers of people willing and committed to donate organs upon their own deaths are far larger than those of potential live donors,” wrote Dr. Ejzenberg and his colleagues. “Further incidental but substantial benefits of the use of deceased donors include lower costs and avoidance of live donors’ surgical risks.”

In 2011, a uterine transplantation from a deceased donor resulted in pregnancy, but ended in miscarriage.

Funding was provided by Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado de São Paulo and the Hospital das Clínicas of University of São Paulo School of Medicine. Dr. Ejzenberg and his colleagues reported that they had no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Ejzenberg D. et al. Lancet. 2018 Dec. doi: 10.1015/S0140-6736(18)31766-5.

FROM THE LANCET

Obesity meds used by just over half of pediatric obesity programs

NASHVILLE, TENN. –

Programs that didn’t offer pharmacotherapy for children and adolescents with obesity cited a variety of reasons in responses to a survey of 33 multicomponent pediatric weight management programs (PWMPs).

Simply not being in favor of using pharmacotherapy for obesity treatment was the most frequently cited reason, named by seven PWMPs that didn’t prescribe obesity medications.

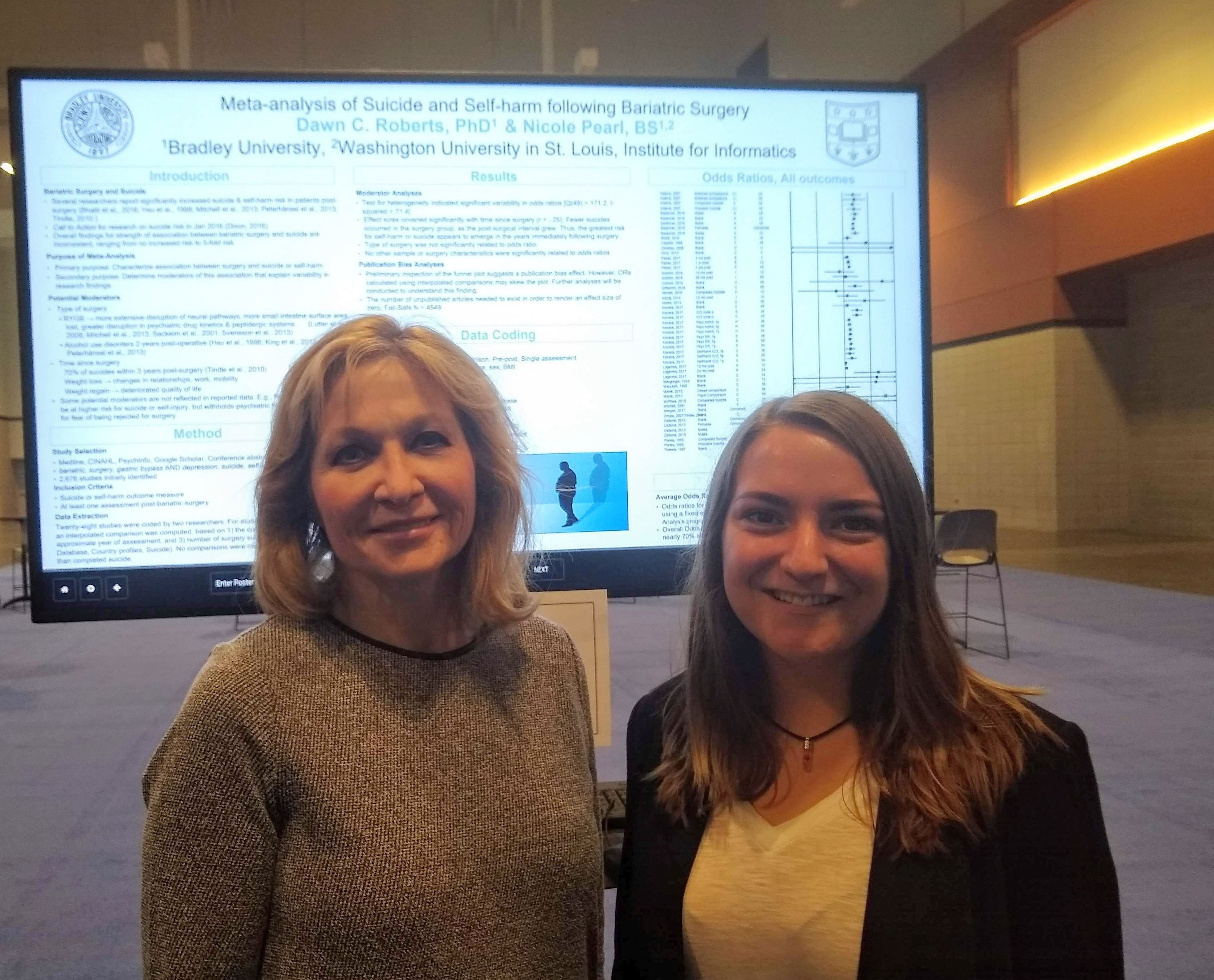

The second most common response to the survey, cited by six programs, was a lack of knowledge about prescribing medications for obesity, and concerns about insurance coverage were noted by five programs, said Claudia Fox, MD, and her colleagues in a poster presentation at a meeting presented by the Obesity Society and the American Society for Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery. “Despite recommendations, few youth with severe obesity are treated with medications.”

Of the programs that did offer pharmacotherapy, 14 prescribed topiramate, and 13 prescribed phentermine. Metformin was used by 11 programs, and orlistat by eight. Six programs prescribed the fixed-dose combination of topiramate and phentermine.

Lorcaserin, naltrexone/bupropion, liraglutide, phendimetrazine, and naltrexone alone all were used by fewer than five programs each.

The national Pediatric Obesity Weight Evaluation Registry (POWER) “was established in 2013 to identify and promote effective intervention strategies for pediatric obesity,” wrote Dr. Fox and her colleagues

Of the 33 POWER PWMPs who were invited to participate, 30 completed a program profile survey. Of these, 16 programs (53%) offered pharmacotherapy, wrote Dr. Fox, the codirector of the University of Minnesota’s Center for Pediatric Obesity Medicine, Minneapolis, and her colleagues in the POWER work group.

In addition to not being in favor of prescribing obesity medication for pediatric patients, lack of knowledge, and insurance concerns, one program cited limited outcome studies for pediatric obesity pharmacotherapy. One other program’s response noted that patients couldn’t be seen frequently enough to assess the safety of obesity medications.

Taken together, the POWER sites had 7,880 patients. Just 5% were aged 2- 5 years, 48% were aged 6-11 years, and 47% were aged 12-18 years. Just over half (53%) were female.

At baseline, about a quarter of patients (26.4%) had class 1 obesity, defined as a body mass index of at least the 95th age- and sex-adjusted percentile. Children and adolescents with class 2 obesity (BMI of at least 1.2-1.4 times the 95th percentile) made up 35.3% of patients; 38.3% had class 3 obesity, with BMIs greater than 1.4 times the 95th percentile.

In 2017, the Endocrine Society published updated clinical practice guidelines for the assessment, treatment, and prevention of pediatric obesity (J Clin Endocrin Metab. 2017 Mar;102:3;709-57). The guidelines for pediatric obesity treatment recommend intensive lifestyle modifications including dietary, physical activity, and behavioral interventions. Pharmacotherapy is suggested “only after a formal program of intensive lifestyle modification has failed to limit weight gain or to ameliorate comorbidities.” Additionally, say the guidelines, Food and Drug Administration–approved pharmacotherapy should be used only “with a concomitant lifestyle modification program of the highest intensity available and only by clinicians who are experienced in the use of anti-obesity agents and are aware of the potential for adverse reactions.”

“Most commonly prescribed medications are not FDA approved for indication of obesity in pediatrics,” noted Dr. Fox and her coauthors. “Further research is needed to evaluate efficacy of pharmacotherapy in the pediatric population and to understand factors impacting prescribing practices.”

Dr. Fox reported no outside sources of funding and had no relevant financial disclosures.

NASHVILLE, TENN. –

Programs that didn’t offer pharmacotherapy for children and adolescents with obesity cited a variety of reasons in responses to a survey of 33 multicomponent pediatric weight management programs (PWMPs).

Simply not being in favor of using pharmacotherapy for obesity treatment was the most frequently cited reason, named by seven PWMPs that didn’t prescribe obesity medications.

The second most common response to the survey, cited by six programs, was a lack of knowledge about prescribing medications for obesity, and concerns about insurance coverage were noted by five programs, said Claudia Fox, MD, and her colleagues in a poster presentation at a meeting presented by the Obesity Society and the American Society for Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery. “Despite recommendations, few youth with severe obesity are treated with medications.”

Of the programs that did offer pharmacotherapy, 14 prescribed topiramate, and 13 prescribed phentermine. Metformin was used by 11 programs, and orlistat by eight. Six programs prescribed the fixed-dose combination of topiramate and phentermine.

Lorcaserin, naltrexone/bupropion, liraglutide, phendimetrazine, and naltrexone alone all were used by fewer than five programs each.

The national Pediatric Obesity Weight Evaluation Registry (POWER) “was established in 2013 to identify and promote effective intervention strategies for pediatric obesity,” wrote Dr. Fox and her colleagues

Of the 33 POWER PWMPs who were invited to participate, 30 completed a program profile survey. Of these, 16 programs (53%) offered pharmacotherapy, wrote Dr. Fox, the codirector of the University of Minnesota’s Center for Pediatric Obesity Medicine, Minneapolis, and her colleagues in the POWER work group.

In addition to not being in favor of prescribing obesity medication for pediatric patients, lack of knowledge, and insurance concerns, one program cited limited outcome studies for pediatric obesity pharmacotherapy. One other program’s response noted that patients couldn’t be seen frequently enough to assess the safety of obesity medications.

Taken together, the POWER sites had 7,880 patients. Just 5% were aged 2- 5 years, 48% were aged 6-11 years, and 47% were aged 12-18 years. Just over half (53%) were female.

At baseline, about a quarter of patients (26.4%) had class 1 obesity, defined as a body mass index of at least the 95th age- and sex-adjusted percentile. Children and adolescents with class 2 obesity (BMI of at least 1.2-1.4 times the 95th percentile) made up 35.3% of patients; 38.3% had class 3 obesity, with BMIs greater than 1.4 times the 95th percentile.

In 2017, the Endocrine Society published updated clinical practice guidelines for the assessment, treatment, and prevention of pediatric obesity (J Clin Endocrin Metab. 2017 Mar;102:3;709-57). The guidelines for pediatric obesity treatment recommend intensive lifestyle modifications including dietary, physical activity, and behavioral interventions. Pharmacotherapy is suggested “only after a formal program of intensive lifestyle modification has failed to limit weight gain or to ameliorate comorbidities.” Additionally, say the guidelines, Food and Drug Administration–approved pharmacotherapy should be used only “with a concomitant lifestyle modification program of the highest intensity available and only by clinicians who are experienced in the use of anti-obesity agents and are aware of the potential for adverse reactions.”

“Most commonly prescribed medications are not FDA approved for indication of obesity in pediatrics,” noted Dr. Fox and her coauthors. “Further research is needed to evaluate efficacy of pharmacotherapy in the pediatric population and to understand factors impacting prescribing practices.”

Dr. Fox reported no outside sources of funding and had no relevant financial disclosures.

NASHVILLE, TENN. –

Programs that didn’t offer pharmacotherapy for children and adolescents with obesity cited a variety of reasons in responses to a survey of 33 multicomponent pediatric weight management programs (PWMPs).

Simply not being in favor of using pharmacotherapy for obesity treatment was the most frequently cited reason, named by seven PWMPs that didn’t prescribe obesity medications.

The second most common response to the survey, cited by six programs, was a lack of knowledge about prescribing medications for obesity, and concerns about insurance coverage were noted by five programs, said Claudia Fox, MD, and her colleagues in a poster presentation at a meeting presented by the Obesity Society and the American Society for Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery. “Despite recommendations, few youth with severe obesity are treated with medications.”

Of the programs that did offer pharmacotherapy, 14 prescribed topiramate, and 13 prescribed phentermine. Metformin was used by 11 programs, and orlistat by eight. Six programs prescribed the fixed-dose combination of topiramate and phentermine.

Lorcaserin, naltrexone/bupropion, liraglutide, phendimetrazine, and naltrexone alone all were used by fewer than five programs each.

The national Pediatric Obesity Weight Evaluation Registry (POWER) “was established in 2013 to identify and promote effective intervention strategies for pediatric obesity,” wrote Dr. Fox and her colleagues

Of the 33 POWER PWMPs who were invited to participate, 30 completed a program profile survey. Of these, 16 programs (53%) offered pharmacotherapy, wrote Dr. Fox, the codirector of the University of Minnesota’s Center for Pediatric Obesity Medicine, Minneapolis, and her colleagues in the POWER work group.

In addition to not being in favor of prescribing obesity medication for pediatric patients, lack of knowledge, and insurance concerns, one program cited limited outcome studies for pediatric obesity pharmacotherapy. One other program’s response noted that patients couldn’t be seen frequently enough to assess the safety of obesity medications.

Taken together, the POWER sites had 7,880 patients. Just 5% were aged 2- 5 years, 48% were aged 6-11 years, and 47% were aged 12-18 years. Just over half (53%) were female.

At baseline, about a quarter of patients (26.4%) had class 1 obesity, defined as a body mass index of at least the 95th age- and sex-adjusted percentile. Children and adolescents with class 2 obesity (BMI of at least 1.2-1.4 times the 95th percentile) made up 35.3% of patients; 38.3% had class 3 obesity, with BMIs greater than 1.4 times the 95th percentile.

In 2017, the Endocrine Society published updated clinical practice guidelines for the assessment, treatment, and prevention of pediatric obesity (J Clin Endocrin Metab. 2017 Mar;102:3;709-57). The guidelines for pediatric obesity treatment recommend intensive lifestyle modifications including dietary, physical activity, and behavioral interventions. Pharmacotherapy is suggested “only after a formal program of intensive lifestyle modification has failed to limit weight gain or to ameliorate comorbidities.” Additionally, say the guidelines, Food and Drug Administration–approved pharmacotherapy should be used only “with a concomitant lifestyle modification program of the highest intensity available and only by clinicians who are experienced in the use of anti-obesity agents and are aware of the potential for adverse reactions.”

“Most commonly prescribed medications are not FDA approved for indication of obesity in pediatrics,” noted Dr. Fox and her coauthors. “Further research is needed to evaluate efficacy of pharmacotherapy in the pediatric population and to understand factors impacting prescribing practices.”

Dr. Fox reported no outside sources of funding and had no relevant financial disclosures.

REPORTING FROM OBESITY WEEK 2018

Key clinical point: Just over half of pediatric weight management programs prescribed obesity medications.

Major finding: Of 30 programs responding, 16 (53%) prescribed obesity medication.

Study details: Survey of 33 programs in the Pediatric Obesity Weight Evaluation Registry (POWER).

Disclosures: Dr. Fox reported no outside sources of funding and no conflicts of interest.

Dietary sodium still in play as a potential MS risk factor

BERLIN – Among a host of potential risk factors for multiple sclerosis (MS), one emerging risk factor – dietary sodium – has accumulating evidence, bolstered by new imaging techniques and emerging research about the mediating effect of the gut microbiome.

“The word is still out on salt – there’s still some work to do; we are not where we stand with smoking or obesity” and the association with MS, said Ralf Linker, MD, speaking at the annual congress of the European Committee for Treatment and Research in Multiple Sclerosis.

For all potential emerging risk factors for MS, there’s an attractive hypothesis and, often, epidemiologic data, Dr. Linker said. “There are probably good [epidemiologic] data in multiple sclerosis for vitamin D, smoking, obesity, and probably also alcohol,” he said. “The therapeutic consequence, however, is much less clear, the best example of that being, of course, vitamin D.”

“The attractive risk factor is not enough to be a hypothesis, although some people seem to believe that nowadays,” said Dr. Linker, chair of the department of neurology at Friedrich-Alexander University, Erlangen, Germany. “Probably it’s better to start with some basic science and some experimental data to get an idea of the mechanism.”

“Today, we need clear associations with clear markers, well-defined cohorts, and proper epidemiological data telling us whether this is a real risk factor. ... If you look at the clinicians – and there are many among us in the room here – your ultimate goal, of course, is to use this as an intervention.”

For salt intake, there’s a clear overlap between high salt consumption in Westernized diets and increasing incidence of MS. The association also holds for many other autoimmune diseases, Dr. Linker added.

“The next step is experimental evidence,” Dr. Linker said. In a rodent model of experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (EAE), rats with high salt intake had a worse clinical course, compared with control rats fed a usual diet (Nature. 2013 Apr 25;496[7446]:518-22).

“There were a lot of follow-up studies on that,” with identification of multiple immune cells that are up- or down-regulated via distinct pathways in a high-salt environment, Dr. Linker said.

More recently, Dr. Linker was a coinvestigator in work showing that healthy humans placed on a high-salt diet had significant increases in T-helper 17 (Th17) cells after just 2 weeks of an additional 6 g of table salt daily over a baseline 2-4 g/day (Nature. 2017 Nov 30;551[7682]:585-9).

“You can also translate it to a more realistic setting,” where individuals who ate fast food four or more times weekly had significantly higher Th17 cell counts than did those who ate less fast food, he noted in reference to unpublished data.

Looking specifically at MS, a single-center study found that increased sodium intake correlated with increased MS clinical disease activity, with the highest sodium intake (more than 4.8 g/day) associated with higher incidence of MS exacerbations. Those in the highest tier of sodium intake also had a higher lesion load, with 3.65 more T2 lesions seen on MRI scans for each gram of salt consumed above average amounts of 2-4.8 g/day (J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2015 Jan;86[1]:26-31).

On the other hand, Dr. Linker said, “There have been recent very well-conducted studies in very well-defined cohorts casting doubt on this translation to multiple sclerosis.” In particular, an examination of data from over 70,000 participants in the Nurse’s Health Study showed no association between MS risk and dietary salt assessed by a nutritional questionnaire (Neurology. 2017 Sep 26;89[13]:1322-9). “There was no hint that the diagnosis was linked in any way with salt exposure,” Dr. Linker said.

In the BENEFIT study, both a spot urine sample and a food questionnaire were used, and patients were grouped into quintiles of sodium intake. For demyelinating events and MS diagnosis, the curves for all quintiles were “completely overlapping,” with no sign of increased risk of MS with higher sodium intake (Ann Neurol. 2017;82:20-9).

An important caveat to the null findings in these analyses is the known poor agreement between self-report of salt intake and actual sodium load, Dr. Linker noted. Renal sodium excretion can vary widely despite fixed salt intake, so spot urine and even 24-hour urine collection don’t guarantee accuracy, he said, citing studies from space travel emulations that show wide day-to-day excursions in sodium excretion with a fixed diet.

A promising tool for accurate assessment of sodium load may be sodium-23 skin spectroscopy using MRI, because skin tissue binds sodium in a stable, nonosmotic fashion. Dr. Linker and his colleagues have recently found that skin sodium levels, measured at the calf, are higher in individuals with relapsing-remitting MS. “Indeed, the sodium level in the skin of the MS patients was significantly higher than in the controls” who did not have MS, he said of the study that matched 20 patients with MS with 20 healthy controls. The MRI studies were assessed by radiologists blinded to the disease status of participants.

The increase is seen in only free sodium and seen in skin, but not muscle tissue, Dr. Linker said.

Using MRI spectroscopy with a powerful 7-Tesla magnet, Dr. Linker and his colleagues returned to the rodent EAE model, also finding increased sodium in the skin. Mass spectrometry findings were similar in other rodent autoimmune models, he said. The differences were not seen for sodium in other organs, or for potassium levels in the skin.

“The most difficult point,” Dr. Linker said, is “can we use this therapeutically somehow? Of course, you can put your patients on a salt-free or very low-salt diet, but it’s not very tasty, of course, and adherence would be probably very, very low.”

The microbiome may play a modulating role that adds to the sodium-MS story and provides a potential therapeutic option. In mice, a high-salt diet was associated with marked and rapid depletion of Lactobacillus species in the mouse gut microbiome. In healthy humans as well, the drop in lactobacilli was quick and profound when 6 g/day of salt was added to the diet, Dr. Linker said (P = .0053 versus the control diet of 2-4 g sodium/day).

Working backward with the same healthy cohort, repletion of Lactobacillus by probiotic supplementation normalized systolic blood pressure, which had become elevated with increased dietary sodium. Further, Lactobacillus repletion downregulated Th17 cells to levels seen before the high-sodium diet, even when dietary sodium stayed high.

“This was even transferred to multiple sclerosis,” in work recently published by another group, Dr. Linker said. For patients with MS who consumed a Lactobacillus-containing probiotic, investigators could “clearly show, besides effects on the microbiome itself, that there were effects on antigen-presenting cells in MS patients.” Intermediate monocytes decreased, as did dendritic cells, in the small study that involved both healthy controls and MS patients who received a probiotic and then underwent a washout period. Stool and blood samples were collected in both groups to compare values with and without probiotic administration.

A question from the audience looked back at historic data: 100 or more years ago, salt was used extensively for food preservation in many parts of the world, so dietary sodium intake is thought to have been higher. The incidence of MS, though, was lower then. Dr. Linker pointed out that food preservation practices varied widely, and that a host of other variables make assessment of past or present associations difficult. “It’s hard to argue that salt is the one and only risk factor; I would strongly doubt that.”

Still, he said, this early work invites more study, with a target of establishing whether probiotic supplementation could be used as “add-on therapy to established immune drugs.”

Dr. Linker has received honoraria and research support from Bayer, Biogen, Genzyme, Merck Serono, Novartis, and TEVA.

SOURCE: Linker R. ECTRIMS 2018, Scientific Session 7.

BERLIN – Among a host of potential risk factors for multiple sclerosis (MS), one emerging risk factor – dietary sodium – has accumulating evidence, bolstered by new imaging techniques and emerging research about the mediating effect of the gut microbiome.

“The word is still out on salt – there’s still some work to do; we are not where we stand with smoking or obesity” and the association with MS, said Ralf Linker, MD, speaking at the annual congress of the European Committee for Treatment and Research in Multiple Sclerosis.

For all potential emerging risk factors for MS, there’s an attractive hypothesis and, often, epidemiologic data, Dr. Linker said. “There are probably good [epidemiologic] data in multiple sclerosis for vitamin D, smoking, obesity, and probably also alcohol,” he said. “The therapeutic consequence, however, is much less clear, the best example of that being, of course, vitamin D.”

“The attractive risk factor is not enough to be a hypothesis, although some people seem to believe that nowadays,” said Dr. Linker, chair of the department of neurology at Friedrich-Alexander University, Erlangen, Germany. “Probably it’s better to start with some basic science and some experimental data to get an idea of the mechanism.”

“Today, we need clear associations with clear markers, well-defined cohorts, and proper epidemiological data telling us whether this is a real risk factor. ... If you look at the clinicians – and there are many among us in the room here – your ultimate goal, of course, is to use this as an intervention.”

For salt intake, there’s a clear overlap between high salt consumption in Westernized diets and increasing incidence of MS. The association also holds for many other autoimmune diseases, Dr. Linker added.

“The next step is experimental evidence,” Dr. Linker said. In a rodent model of experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (EAE), rats with high salt intake had a worse clinical course, compared with control rats fed a usual diet (Nature. 2013 Apr 25;496[7446]:518-22).

“There were a lot of follow-up studies on that,” with identification of multiple immune cells that are up- or down-regulated via distinct pathways in a high-salt environment, Dr. Linker said.

More recently, Dr. Linker was a coinvestigator in work showing that healthy humans placed on a high-salt diet had significant increases in T-helper 17 (Th17) cells after just 2 weeks of an additional 6 g of table salt daily over a baseline 2-4 g/day (Nature. 2017 Nov 30;551[7682]:585-9).

“You can also translate it to a more realistic setting,” where individuals who ate fast food four or more times weekly had significantly higher Th17 cell counts than did those who ate less fast food, he noted in reference to unpublished data.

Looking specifically at MS, a single-center study found that increased sodium intake correlated with increased MS clinical disease activity, with the highest sodium intake (more than 4.8 g/day) associated with higher incidence of MS exacerbations. Those in the highest tier of sodium intake also had a higher lesion load, with 3.65 more T2 lesions seen on MRI scans for each gram of salt consumed above average amounts of 2-4.8 g/day (J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2015 Jan;86[1]:26-31).

On the other hand, Dr. Linker said, “There have been recent very well-conducted studies in very well-defined cohorts casting doubt on this translation to multiple sclerosis.” In particular, an examination of data from over 70,000 participants in the Nurse’s Health Study showed no association between MS risk and dietary salt assessed by a nutritional questionnaire (Neurology. 2017 Sep 26;89[13]:1322-9). “There was no hint that the diagnosis was linked in any way with salt exposure,” Dr. Linker said.

In the BENEFIT study, both a spot urine sample and a food questionnaire were used, and patients were grouped into quintiles of sodium intake. For demyelinating events and MS diagnosis, the curves for all quintiles were “completely overlapping,” with no sign of increased risk of MS with higher sodium intake (Ann Neurol. 2017;82:20-9).

An important caveat to the null findings in these analyses is the known poor agreement between self-report of salt intake and actual sodium load, Dr. Linker noted. Renal sodium excretion can vary widely despite fixed salt intake, so spot urine and even 24-hour urine collection don’t guarantee accuracy, he said, citing studies from space travel emulations that show wide day-to-day excursions in sodium excretion with a fixed diet.

A promising tool for accurate assessment of sodium load may be sodium-23 skin spectroscopy using MRI, because skin tissue binds sodium in a stable, nonosmotic fashion. Dr. Linker and his colleagues have recently found that skin sodium levels, measured at the calf, are higher in individuals with relapsing-remitting MS. “Indeed, the sodium level in the skin of the MS patients was significantly higher than in the controls” who did not have MS, he said of the study that matched 20 patients with MS with 20 healthy controls. The MRI studies were assessed by radiologists blinded to the disease status of participants.

The increase is seen in only free sodium and seen in skin, but not muscle tissue, Dr. Linker said.

Using MRI spectroscopy with a powerful 7-Tesla magnet, Dr. Linker and his colleagues returned to the rodent EAE model, also finding increased sodium in the skin. Mass spectrometry findings were similar in other rodent autoimmune models, he said. The differences were not seen for sodium in other organs, or for potassium levels in the skin.

“The most difficult point,” Dr. Linker said, is “can we use this therapeutically somehow? Of course, you can put your patients on a salt-free or very low-salt diet, but it’s not very tasty, of course, and adherence would be probably very, very low.”

The microbiome may play a modulating role that adds to the sodium-MS story and provides a potential therapeutic option. In mice, a high-salt diet was associated with marked and rapid depletion of Lactobacillus species in the mouse gut microbiome. In healthy humans as well, the drop in lactobacilli was quick and profound when 6 g/day of salt was added to the diet, Dr. Linker said (P = .0053 versus the control diet of 2-4 g sodium/day).

Working backward with the same healthy cohort, repletion of Lactobacillus by probiotic supplementation normalized systolic blood pressure, which had become elevated with increased dietary sodium. Further, Lactobacillus repletion downregulated Th17 cells to levels seen before the high-sodium diet, even when dietary sodium stayed high.

“This was even transferred to multiple sclerosis,” in work recently published by another group, Dr. Linker said. For patients with MS who consumed a Lactobacillus-containing probiotic, investigators could “clearly show, besides effects on the microbiome itself, that there were effects on antigen-presenting cells in MS patients.” Intermediate monocytes decreased, as did dendritic cells, in the small study that involved both healthy controls and MS patients who received a probiotic and then underwent a washout period. Stool and blood samples were collected in both groups to compare values with and without probiotic administration.

A question from the audience looked back at historic data: 100 or more years ago, salt was used extensively for food preservation in many parts of the world, so dietary sodium intake is thought to have been higher. The incidence of MS, though, was lower then. Dr. Linker pointed out that food preservation practices varied widely, and that a host of other variables make assessment of past or present associations difficult. “It’s hard to argue that salt is the one and only risk factor; I would strongly doubt that.”

Still, he said, this early work invites more study, with a target of establishing whether probiotic supplementation could be used as “add-on therapy to established immune drugs.”

Dr. Linker has received honoraria and research support from Bayer, Biogen, Genzyme, Merck Serono, Novartis, and TEVA.

SOURCE: Linker R. ECTRIMS 2018, Scientific Session 7.

BERLIN – Among a host of potential risk factors for multiple sclerosis (MS), one emerging risk factor – dietary sodium – has accumulating evidence, bolstered by new imaging techniques and emerging research about the mediating effect of the gut microbiome.

“The word is still out on salt – there’s still some work to do; we are not where we stand with smoking or obesity” and the association with MS, said Ralf Linker, MD, speaking at the annual congress of the European Committee for Treatment and Research in Multiple Sclerosis.

For all potential emerging risk factors for MS, there’s an attractive hypothesis and, often, epidemiologic data, Dr. Linker said. “There are probably good [epidemiologic] data in multiple sclerosis for vitamin D, smoking, obesity, and probably also alcohol,” he said. “The therapeutic consequence, however, is much less clear, the best example of that being, of course, vitamin D.”

“The attractive risk factor is not enough to be a hypothesis, although some people seem to believe that nowadays,” said Dr. Linker, chair of the department of neurology at Friedrich-Alexander University, Erlangen, Germany. “Probably it’s better to start with some basic science and some experimental data to get an idea of the mechanism.”

“Today, we need clear associations with clear markers, well-defined cohorts, and proper epidemiological data telling us whether this is a real risk factor. ... If you look at the clinicians – and there are many among us in the room here – your ultimate goal, of course, is to use this as an intervention.”

For salt intake, there’s a clear overlap between high salt consumption in Westernized diets and increasing incidence of MS. The association also holds for many other autoimmune diseases, Dr. Linker added.

“The next step is experimental evidence,” Dr. Linker said. In a rodent model of experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (EAE), rats with high salt intake had a worse clinical course, compared with control rats fed a usual diet (Nature. 2013 Apr 25;496[7446]:518-22).

“There were a lot of follow-up studies on that,” with identification of multiple immune cells that are up- or down-regulated via distinct pathways in a high-salt environment, Dr. Linker said.

More recently, Dr. Linker was a coinvestigator in work showing that healthy humans placed on a high-salt diet had significant increases in T-helper 17 (Th17) cells after just 2 weeks of an additional 6 g of table salt daily over a baseline 2-4 g/day (Nature. 2017 Nov 30;551[7682]:585-9).

“You can also translate it to a more realistic setting,” where individuals who ate fast food four or more times weekly had significantly higher Th17 cell counts than did those who ate less fast food, he noted in reference to unpublished data.

Looking specifically at MS, a single-center study found that increased sodium intake correlated with increased MS clinical disease activity, with the highest sodium intake (more than 4.8 g/day) associated with higher incidence of MS exacerbations. Those in the highest tier of sodium intake also had a higher lesion load, with 3.65 more T2 lesions seen on MRI scans for each gram of salt consumed above average amounts of 2-4.8 g/day (J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2015 Jan;86[1]:26-31).

On the other hand, Dr. Linker said, “There have been recent very well-conducted studies in very well-defined cohorts casting doubt on this translation to multiple sclerosis.” In particular, an examination of data from over 70,000 participants in the Nurse’s Health Study showed no association between MS risk and dietary salt assessed by a nutritional questionnaire (Neurology. 2017 Sep 26;89[13]:1322-9). “There was no hint that the diagnosis was linked in any way with salt exposure,” Dr. Linker said.

In the BENEFIT study, both a spot urine sample and a food questionnaire were used, and patients were grouped into quintiles of sodium intake. For demyelinating events and MS diagnosis, the curves for all quintiles were “completely overlapping,” with no sign of increased risk of MS with higher sodium intake (Ann Neurol. 2017;82:20-9).

An important caveat to the null findings in these analyses is the known poor agreement between self-report of salt intake and actual sodium load, Dr. Linker noted. Renal sodium excretion can vary widely despite fixed salt intake, so spot urine and even 24-hour urine collection don’t guarantee accuracy, he said, citing studies from space travel emulations that show wide day-to-day excursions in sodium excretion with a fixed diet.

A promising tool for accurate assessment of sodium load may be sodium-23 skin spectroscopy using MRI, because skin tissue binds sodium in a stable, nonosmotic fashion. Dr. Linker and his colleagues have recently found that skin sodium levels, measured at the calf, are higher in individuals with relapsing-remitting MS. “Indeed, the sodium level in the skin of the MS patients was significantly higher than in the controls” who did not have MS, he said of the study that matched 20 patients with MS with 20 healthy controls. The MRI studies were assessed by radiologists blinded to the disease status of participants.

The increase is seen in only free sodium and seen in skin, but not muscle tissue, Dr. Linker said.

Using MRI spectroscopy with a powerful 7-Tesla magnet, Dr. Linker and his colleagues returned to the rodent EAE model, also finding increased sodium in the skin. Mass spectrometry findings were similar in other rodent autoimmune models, he said. The differences were not seen for sodium in other organs, or for potassium levels in the skin.

“The most difficult point,” Dr. Linker said, is “can we use this therapeutically somehow? Of course, you can put your patients on a salt-free or very low-salt diet, but it’s not very tasty, of course, and adherence would be probably very, very low.”

The microbiome may play a modulating role that adds to the sodium-MS story and provides a potential therapeutic option. In mice, a high-salt diet was associated with marked and rapid depletion of Lactobacillus species in the mouse gut microbiome. In healthy humans as well, the drop in lactobacilli was quick and profound when 6 g/day of salt was added to the diet, Dr. Linker said (P = .0053 versus the control diet of 2-4 g sodium/day).

Working backward with the same healthy cohort, repletion of Lactobacillus by probiotic supplementation normalized systolic blood pressure, which had become elevated with increased dietary sodium. Further, Lactobacillus repletion downregulated Th17 cells to levels seen before the high-sodium diet, even when dietary sodium stayed high.

“This was even transferred to multiple sclerosis,” in work recently published by another group, Dr. Linker said. For patients with MS who consumed a Lactobacillus-containing probiotic, investigators could “clearly show, besides effects on the microbiome itself, that there were effects on antigen-presenting cells in MS patients.” Intermediate monocytes decreased, as did dendritic cells, in the small study that involved both healthy controls and MS patients who received a probiotic and then underwent a washout period. Stool and blood samples were collected in both groups to compare values with and without probiotic administration.

A question from the audience looked back at historic data: 100 or more years ago, salt was used extensively for food preservation in many parts of the world, so dietary sodium intake is thought to have been higher. The incidence of MS, though, was lower then. Dr. Linker pointed out that food preservation practices varied widely, and that a host of other variables make assessment of past or present associations difficult. “It’s hard to argue that salt is the one and only risk factor; I would strongly doubt that.”

Still, he said, this early work invites more study, with a target of establishing whether probiotic supplementation could be used as “add-on therapy to established immune drugs.”

Dr. Linker has received honoraria and research support from Bayer, Biogen, Genzyme, Merck Serono, Novartis, and TEVA.

SOURCE: Linker R. ECTRIMS 2018, Scientific Session 7.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM ECTRIMS 2018

Breastfeeding with MS: Good for mom, too

BERLIN – In the changing multiple sclerosis landscape, more women are having babies, and more are asking questions. With these women, what’s the best way to address the complicated interplay among pregnancy, relapse risk, breastfeeding, and medication resumption? A starting point is to recognize that “women with MS are very different today than they were 25 years ago,” said Annette Langer-Gould, MD, PhD. Not only have diagnostic criteria changed but also highly effective treatments now exist that were not available when the first pregnancy cohorts were studied, she pointed out, speaking at the annual congress of the European Committee on Treatment and Research in Multiple Sclerosis.

The existing literature, said Dr. Langer-Gould, has addressed one controversy: “Most women with MS can have normal pregnancies – and breastfeed – without incurring harm,” though it’s true that severe rebound relapses are possible if natalizumab (Tysabri) or fingolimod (Gilenya) are stopped before pregnancy. In any case, new small-molecule MS medications need to be stopped during pregnancy and breastfeeding, she pointed out. “We didn’t have to worry about that too much when we only had injectables and monoclonal antibodies because they were larger and didn’t cross the placenta.”

Since the 1980s, the conversation about pregnancy and MS has moved from asking “Is pregnancy bad for women with MS?” to the current MS landscape, in which sicker women are able to become pregnant, Dr. Langer-Gould said, adding that how women with MS fare through pregnancy and in the postpartum period is changing over time as well. She and her colleagues’ experience with pregnancy in a cohort of women with MS in the Kaiser Permanente care system, where she is a clinical neurologist and regional research lead, revealed a relapse rate of 8.4%. “So it was pretty rare for a woman to have a relapse during pregnancy,” Dr. Langer-Gould said.

Most women with MS who become pregnant, whether their care is received in a referral center or is community based, are now doing so while on a disease-modifying therapy (DMT), Dr. Langer-Gould said. On these highly effective treatments, “women who were too sick to get pregnant are now well controlled and having babies.”

As more women with MS become pregnant, more conversations about breastfeeding will inevitably crop up, she said. And the discussion about breastfeeding has now begun to acknowledge the “strong benefits to mom and the baby of not just breastfeeding, but longer breastfeeding,” as well.

“Because of this baby-friendly push in a lot of hospitals in the United States, where they’re trying to encourage all women to breastfeed,” a full 87% of women breastfed their infants at least some of the time, and over a third of women (35%) breastfed exclusively for at least 2 months, Dr. Langer-Gould said.

“There’s no one clear explanation of why the women seem to be healthier and doing better through pregnancy as a group, but it’s probably a combination of having milder disease, breastfeeding more, and they’ve got better controlled disease before pregnancy,” she said.

At least eight studies to date have examined the relationship between postpartum MS relapses and breastfeeding, Dr. Langer-Gould said.

“The thing to take away ... is that, even though we’ve studied this many, many times, no one can show that it’s harmful,” she said. For mothers who want to breastfeed, “you can support them in the breastfeeding choice, because they are not going to have more severe disease because of that.”

Whether breastfeeding is exclusive or not has not always been tracked in studies of childbearing women with MS, but when it was captured in the data, exclusive breastfeeding has exerted a protective effect, with about a 50% reduction in risk for postpartum relapse seen in one study (JAMA Neurol. 2015 Oct;72[10]:1132-8).

There is a hormonal rationale for exclusive breastfeeding exerting a protective effect on MS: With exclusive breastfeeding comes more frequent, intense suckling, with more profound elevations in prolactin, and larger drops in follicle-stimulating hormone, luteinizing hormone, progesterone, and estradiol. All these hormonal changes work together to produce more prolonged amenorrhea and anovulation, Dr. Langer-Gould said, with potentially beneficial immunologic effects.

When other, more general maternal and infant health benefits of breastfeeding also are taken into account, there’s strong evidence for the benefits of breastfeeding for women with MS whose medication profile allows them to breastfeed, she said.

However, the “treatment” effect of exclusive breastfeeding is only effective until the infant starts taking regular supplemental feedings, including the introduction of table food at around 6 months of age. “Once regular supplemental feedings are introduced, relapses return,” Dr. Langer-Gould said.

There is some suggestion that, in women without MS, prolonged breastfeeding may be associated with reduced risk of MS. In the MS Sunshine study, breastfeeding for 15 months or longer decreased the risk of later MS by 23%-53% (Nutrients. 2018 Feb 27;10[3]:268). The investigators, led by Dr. Langer-Gould, summed the total months of breastfeeding across all children, so that the 15-month threshold could be reached by breastfeeding one child for 15 months, or three children for 5 months each. “It’s a single study; I wouldn’t make too much out of it,” Dr. Langer-Gould said.

Open questions still remain, she said: “So far, no one has been able to demonstrate a clear beneficial effect in reducing the risk of postpartum relapse if they resume their DMT early in the postpartum period.” Dr. Langer-Gould noted that the literature in this area is hampered by heterogeneity and by the fact that newer, more highly active DMTs have not been well studied.

Also, the link between postpartum relapses and long-term prognosis is not completely delineated. Indirect evidence, she said, points to a postpartum relapse as being “overall, a low-impact event.”

Dr. Langer-Gould reported that she has been the site principal investigator for clinical trials sponsored by Roche and Biogen.

SOURCE: Langer-Gould A. ECTRIMS 2018, Abstract 5.

BERLIN – In the changing multiple sclerosis landscape, more women are having babies, and more are asking questions. With these women, what’s the best way to address the complicated interplay among pregnancy, relapse risk, breastfeeding, and medication resumption? A starting point is to recognize that “women with MS are very different today than they were 25 years ago,” said Annette Langer-Gould, MD, PhD. Not only have diagnostic criteria changed but also highly effective treatments now exist that were not available when the first pregnancy cohorts were studied, she pointed out, speaking at the annual congress of the European Committee on Treatment and Research in Multiple Sclerosis.

The existing literature, said Dr. Langer-Gould, has addressed one controversy: “Most women with MS can have normal pregnancies – and breastfeed – without incurring harm,” though it’s true that severe rebound relapses are possible if natalizumab (Tysabri) or fingolimod (Gilenya) are stopped before pregnancy. In any case, new small-molecule MS medications need to be stopped during pregnancy and breastfeeding, she pointed out. “We didn’t have to worry about that too much when we only had injectables and monoclonal antibodies because they were larger and didn’t cross the placenta.”

Since the 1980s, the conversation about pregnancy and MS has moved from asking “Is pregnancy bad for women with MS?” to the current MS landscape, in which sicker women are able to become pregnant, Dr. Langer-Gould said, adding that how women with MS fare through pregnancy and in the postpartum period is changing over time as well. She and her colleagues’ experience with pregnancy in a cohort of women with MS in the Kaiser Permanente care system, where she is a clinical neurologist and regional research lead, revealed a relapse rate of 8.4%. “So it was pretty rare for a woman to have a relapse during pregnancy,” Dr. Langer-Gould said.

Most women with MS who become pregnant, whether their care is received in a referral center or is community based, are now doing so while on a disease-modifying therapy (DMT), Dr. Langer-Gould said. On these highly effective treatments, “women who were too sick to get pregnant are now well controlled and having babies.”

As more women with MS become pregnant, more conversations about breastfeeding will inevitably crop up, she said. And the discussion about breastfeeding has now begun to acknowledge the “strong benefits to mom and the baby of not just breastfeeding, but longer breastfeeding,” as well.

“Because of this baby-friendly push in a lot of hospitals in the United States, where they’re trying to encourage all women to breastfeed,” a full 87% of women breastfed their infants at least some of the time, and over a third of women (35%) breastfed exclusively for at least 2 months, Dr. Langer-Gould said.

“There’s no one clear explanation of why the women seem to be healthier and doing better through pregnancy as a group, but it’s probably a combination of having milder disease, breastfeeding more, and they’ve got better controlled disease before pregnancy,” she said.

At least eight studies to date have examined the relationship between postpartum MS relapses and breastfeeding, Dr. Langer-Gould said.

“The thing to take away ... is that, even though we’ve studied this many, many times, no one can show that it’s harmful,” she said. For mothers who want to breastfeed, “you can support them in the breastfeeding choice, because they are not going to have more severe disease because of that.”

Whether breastfeeding is exclusive or not has not always been tracked in studies of childbearing women with MS, but when it was captured in the data, exclusive breastfeeding has exerted a protective effect, with about a 50% reduction in risk for postpartum relapse seen in one study (JAMA Neurol. 2015 Oct;72[10]:1132-8).

There is a hormonal rationale for exclusive breastfeeding exerting a protective effect on MS: With exclusive breastfeeding comes more frequent, intense suckling, with more profound elevations in prolactin, and larger drops in follicle-stimulating hormone, luteinizing hormone, progesterone, and estradiol. All these hormonal changes work together to produce more prolonged amenorrhea and anovulation, Dr. Langer-Gould said, with potentially beneficial immunologic effects.

When other, more general maternal and infant health benefits of breastfeeding also are taken into account, there’s strong evidence for the benefits of breastfeeding for women with MS whose medication profile allows them to breastfeed, she said.

However, the “treatment” effect of exclusive breastfeeding is only effective until the infant starts taking regular supplemental feedings, including the introduction of table food at around 6 months of age. “Once regular supplemental feedings are introduced, relapses return,” Dr. Langer-Gould said.

There is some suggestion that, in women without MS, prolonged breastfeeding may be associated with reduced risk of MS. In the MS Sunshine study, breastfeeding for 15 months or longer decreased the risk of later MS by 23%-53% (Nutrients. 2018 Feb 27;10[3]:268). The investigators, led by Dr. Langer-Gould, summed the total months of breastfeeding across all children, so that the 15-month threshold could be reached by breastfeeding one child for 15 months, or three children for 5 months each. “It’s a single study; I wouldn’t make too much out of it,” Dr. Langer-Gould said.

Open questions still remain, she said: “So far, no one has been able to demonstrate a clear beneficial effect in reducing the risk of postpartum relapse if they resume their DMT early in the postpartum period.” Dr. Langer-Gould noted that the literature in this area is hampered by heterogeneity and by the fact that newer, more highly active DMTs have not been well studied.

Also, the link between postpartum relapses and long-term prognosis is not completely delineated. Indirect evidence, she said, points to a postpartum relapse as being “overall, a low-impact event.”

Dr. Langer-Gould reported that she has been the site principal investigator for clinical trials sponsored by Roche and Biogen.

SOURCE: Langer-Gould A. ECTRIMS 2018, Abstract 5.

BERLIN – In the changing multiple sclerosis landscape, more women are having babies, and more are asking questions. With these women, what’s the best way to address the complicated interplay among pregnancy, relapse risk, breastfeeding, and medication resumption? A starting point is to recognize that “women with MS are very different today than they were 25 years ago,” said Annette Langer-Gould, MD, PhD. Not only have diagnostic criteria changed but also highly effective treatments now exist that were not available when the first pregnancy cohorts were studied, she pointed out, speaking at the annual congress of the European Committee on Treatment and Research in Multiple Sclerosis.

The existing literature, said Dr. Langer-Gould, has addressed one controversy: “Most women with MS can have normal pregnancies – and breastfeed – without incurring harm,” though it’s true that severe rebound relapses are possible if natalizumab (Tysabri) or fingolimod (Gilenya) are stopped before pregnancy. In any case, new small-molecule MS medications need to be stopped during pregnancy and breastfeeding, she pointed out. “We didn’t have to worry about that too much when we only had injectables and monoclonal antibodies because they were larger and didn’t cross the placenta.”

Since the 1980s, the conversation about pregnancy and MS has moved from asking “Is pregnancy bad for women with MS?” to the current MS landscape, in which sicker women are able to become pregnant, Dr. Langer-Gould said, adding that how women with MS fare through pregnancy and in the postpartum period is changing over time as well. She and her colleagues’ experience with pregnancy in a cohort of women with MS in the Kaiser Permanente care system, where she is a clinical neurologist and regional research lead, revealed a relapse rate of 8.4%. “So it was pretty rare for a woman to have a relapse during pregnancy,” Dr. Langer-Gould said.

Most women with MS who become pregnant, whether their care is received in a referral center or is community based, are now doing so while on a disease-modifying therapy (DMT), Dr. Langer-Gould said. On these highly effective treatments, “women who were too sick to get pregnant are now well controlled and having babies.”

As more women with MS become pregnant, more conversations about breastfeeding will inevitably crop up, she said. And the discussion about breastfeeding has now begun to acknowledge the “strong benefits to mom and the baby of not just breastfeeding, but longer breastfeeding,” as well.

“Because of this baby-friendly push in a lot of hospitals in the United States, where they’re trying to encourage all women to breastfeed,” a full 87% of women breastfed their infants at least some of the time, and over a third of women (35%) breastfed exclusively for at least 2 months, Dr. Langer-Gould said.

“There’s no one clear explanation of why the women seem to be healthier and doing better through pregnancy as a group, but it’s probably a combination of having milder disease, breastfeeding more, and they’ve got better controlled disease before pregnancy,” she said.

At least eight studies to date have examined the relationship between postpartum MS relapses and breastfeeding, Dr. Langer-Gould said.

“The thing to take away ... is that, even though we’ve studied this many, many times, no one can show that it’s harmful,” she said. For mothers who want to breastfeed, “you can support them in the breastfeeding choice, because they are not going to have more severe disease because of that.”

Whether breastfeeding is exclusive or not has not always been tracked in studies of childbearing women with MS, but when it was captured in the data, exclusive breastfeeding has exerted a protective effect, with about a 50% reduction in risk for postpartum relapse seen in one study (JAMA Neurol. 2015 Oct;72[10]:1132-8).

There is a hormonal rationale for exclusive breastfeeding exerting a protective effect on MS: With exclusive breastfeeding comes more frequent, intense suckling, with more profound elevations in prolactin, and larger drops in follicle-stimulating hormone, luteinizing hormone, progesterone, and estradiol. All these hormonal changes work together to produce more prolonged amenorrhea and anovulation, Dr. Langer-Gould said, with potentially beneficial immunologic effects.

When other, more general maternal and infant health benefits of breastfeeding also are taken into account, there’s strong evidence for the benefits of breastfeeding for women with MS whose medication profile allows them to breastfeed, she said.

However, the “treatment” effect of exclusive breastfeeding is only effective until the infant starts taking regular supplemental feedings, including the introduction of table food at around 6 months of age. “Once regular supplemental feedings are introduced, relapses return,” Dr. Langer-Gould said.

There is some suggestion that, in women without MS, prolonged breastfeeding may be associated with reduced risk of MS. In the MS Sunshine study, breastfeeding for 15 months or longer decreased the risk of later MS by 23%-53% (Nutrients. 2018 Feb 27;10[3]:268). The investigators, led by Dr. Langer-Gould, summed the total months of breastfeeding across all children, so that the 15-month threshold could be reached by breastfeeding one child for 15 months, or three children for 5 months each. “It’s a single study; I wouldn’t make too much out of it,” Dr. Langer-Gould said.