User login

MRI is a critical part of the MS precision medicine toolkit

DALLAS – MRI has long been important in both diagnosis and management of multiple sclerosis (MS). It’s more important than ever though, as perivenular demyelinating lesions emerge as a potential biomarker of the disease, and a key tool in precision medicine initiatives that target MS.

“The central vein sign is at the current time still a research tool that is being touted as an imaging finding that may be a very useful biomarker for diagnosis in MS,” said Jiwon Oh, MD, PhD, in an interview at the meeting presented by the Americas Committee for Treatment and Research in Multiple Sclerosis.

It’s almost ready for “prime time,” she said, “because it can easily be acquired on most conventional 3 Tesla MRI scanners, the sequences that you use don’t require an inordinate amount of time [and] it doesn’t take too much training to be able to easily identify the sign.”

A number of groups have evaluated the central vein sign and are finding it “a very specific biomarker” for MS, Dr. Oh said.

“It would be very useful in very early stages of diagnosis because it would prevent people from being misdiagnosed” and being treated unnecessarily, she said.

In her own work, Dr. Oh and her collaborators are following a cohort of people with radiologically isolated syndrome (RIS) discovered incidentally on brain imaging. “It’s a very valuable patient population to study because it may give us insight into the very earliest stages of MS,” as the lesions were not accompanied by any symptoms when they were first noticed.

Dr. Oh and her colleagues are finding that, among RIS patients, “the vast, vast majority of people have lesions with central veins; in our cohort, over 90% of patients met the 40% threshold that has been proposed to distinguish MS from other white matter changes.”

Dr. Oh said that the central vein sign may prove to be prognostic among RIS patients; they continue to follow the cohort being studied at the University of Toronto, where Dr. Oh is a neurologist.

DALLAS – MRI has long been important in both diagnosis and management of multiple sclerosis (MS). It’s more important than ever though, as perivenular demyelinating lesions emerge as a potential biomarker of the disease, and a key tool in precision medicine initiatives that target MS.

“The central vein sign is at the current time still a research tool that is being touted as an imaging finding that may be a very useful biomarker for diagnosis in MS,” said Jiwon Oh, MD, PhD, in an interview at the meeting presented by the Americas Committee for Treatment and Research in Multiple Sclerosis.

It’s almost ready for “prime time,” she said, “because it can easily be acquired on most conventional 3 Tesla MRI scanners, the sequences that you use don’t require an inordinate amount of time [and] it doesn’t take too much training to be able to easily identify the sign.”

A number of groups have evaluated the central vein sign and are finding it “a very specific biomarker” for MS, Dr. Oh said.

“It would be very useful in very early stages of diagnosis because it would prevent people from being misdiagnosed” and being treated unnecessarily, she said.

In her own work, Dr. Oh and her collaborators are following a cohort of people with radiologically isolated syndrome (RIS) discovered incidentally on brain imaging. “It’s a very valuable patient population to study because it may give us insight into the very earliest stages of MS,” as the lesions were not accompanied by any symptoms when they were first noticed.

Dr. Oh and her colleagues are finding that, among RIS patients, “the vast, vast majority of people have lesions with central veins; in our cohort, over 90% of patients met the 40% threshold that has been proposed to distinguish MS from other white matter changes.”

Dr. Oh said that the central vein sign may prove to be prognostic among RIS patients; they continue to follow the cohort being studied at the University of Toronto, where Dr. Oh is a neurologist.

DALLAS – MRI has long been important in both diagnosis and management of multiple sclerosis (MS). It’s more important than ever though, as perivenular demyelinating lesions emerge as a potential biomarker of the disease, and a key tool in precision medicine initiatives that target MS.

“The central vein sign is at the current time still a research tool that is being touted as an imaging finding that may be a very useful biomarker for diagnosis in MS,” said Jiwon Oh, MD, PhD, in an interview at the meeting presented by the Americas Committee for Treatment and Research in Multiple Sclerosis.

It’s almost ready for “prime time,” she said, “because it can easily be acquired on most conventional 3 Tesla MRI scanners, the sequences that you use don’t require an inordinate amount of time [and] it doesn’t take too much training to be able to easily identify the sign.”

A number of groups have evaluated the central vein sign and are finding it “a very specific biomarker” for MS, Dr. Oh said.

“It would be very useful in very early stages of diagnosis because it would prevent people from being misdiagnosed” and being treated unnecessarily, she said.

In her own work, Dr. Oh and her collaborators are following a cohort of people with radiologically isolated syndrome (RIS) discovered incidentally on brain imaging. “It’s a very valuable patient population to study because it may give us insight into the very earliest stages of MS,” as the lesions were not accompanied by any symptoms when they were first noticed.

Dr. Oh and her colleagues are finding that, among RIS patients, “the vast, vast majority of people have lesions with central veins; in our cohort, over 90% of patients met the 40% threshold that has been proposed to distinguish MS from other white matter changes.”

Dr. Oh said that the central vein sign may prove to be prognostic among RIS patients; they continue to follow the cohort being studied at the University of Toronto, where Dr. Oh is a neurologist.

REPORTING FROM ACTRIMS FORUM 2019

Tight intrapartum glucose control doesn’t improve neonatal outcomes

LAS VEGAS – There was no difference in first neonatal glucose level or glucose levels within the first 24 hours of life when women with gestational diabetes received strict, rather than liberalized, glucose management in labor.

In a study of 76 women with gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM), the mean first blood glucose level was 53 mg/dL for neonates born to the 38 mothers who received tight glucose control during labor; for those born to the 38 women who received liberalized control, mean first glucose level was 56 mg/dL (interquartile ranges, 22-85 mg/dL and 27-126 mg/dL, respectively; P = .56).

Secondary outcomes tracked in the study included the proportion of neonates whose glucose levels were low (defined as less than 40 mg/dL) at birth. This figure was identical in both groups, at 24%.

These findings ran counter to the hypothesis that Maureen Hamel, MD, and her colleagues at Brown University, Providence, R.I., had formulated – that neonates whose mothers had tight intrapartum glucose control would have lower rates of neonatal hypoglycemia than those born to women with liberalized intrapartum control.

Although the differences did not reach statistical significance, numerically more infants in the tight-control group required any intervention for hypoglycemia (45% vs. 32%; P = .35) or intravenous intervention for hypoglycemia (11% vs 0%; P = .35). Neonatal ICU admission was required for 13% of the tight-control neonates versus 3% of the liberalized-control group (P = .20).

“A protocol aimed at tight maternal glucose management in labor, compared to liberalized management, for women with GDM, did not result in a lower rate of neonatal hypoglycemia and was associated with mean neonatal glucose closer to hypoglycemia [40 mg/dL] in the first 24 hours of life,” said Dr. Hamel, discussing the findings of her award-winning abstract at the meeting presented by the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine.

Women were included if they were at least 18 years old with a singleton pregnancy and a diagnosis of gestational diabetes. Participants received care through a specialized program for pregnant women with diabetes; they were considered to have GDM if they had at least two abnormal values from a 100-g, 3-hour glucose tolerance test (GTT) or had a blood glucose reading of at least 200 mg/dL from a 1-hour 50-g GTT. About two-thirds of women required medical management of GDM; about 80% received labor induction at 39 weeks’ gestation.

At 36 weeks’ gestation, participants were block-randomized 1:1 to receive tight or liberalized intrapartum blood glucose control, with allocation unknown to both providers and patients until participants were admitted for delivery. Neonatal providers were blinded as to allocation throughout the admission. “In the tight glucose control group, point-of-care glucose was assessed hourly,” said Dr. Hamel. “Goal glucose levels were 70-100 [mg/dL], and treatment was initiated for a single maternal glucose greater than 100 and less than 60 [mg/dL].”

Those in the liberalized group had blood sugar checked every 4 hours in the absence of symptoms, with a goal blood glucose range of 70-120 mg/dL and treatment initiated for blood glucose over 120 or less than 60 mg/dL.

The increase in older women giving birth partly underlies the increase in GDM, said Dr. Hamel. By 35 years of age, about 15% of women will develop GDM, compared with under 6% for women giving birth between 20 and 24 years of age.

Neonatal hypoglycemia, with associated risks for neonatal ICU admission, seizures, and neurologic injury, is more common in women with GDM, said Dr. Hamel, a maternal-fetal medicine fellow.

There’s wide institutional and geographic variation in intrapartum maternal glucose management, said Dr. Hamel. Even within her own institution, blood sugar might be checked just once in labor, every 2 hours, or every hour, and the threshold for treatment might be set at a maternal blood glucose level over 100, 120, or even 200 mg/dL.

The study benefited from the fact that there was standardized antepartum GDM management in place and that 100% of outcome data were available. Also, the a priori sample size to detect significant between-group differences was obtained, and neonatal providers were blinded as to maternal glucose control strategy. Replication of the study should be both easy and feasible, said Dr. Hamel.

However, only very short-term outcomes were tracked, and the study was not powered to detect differences in such less-frequent neonatal outcomes as neonatal ICU admission.

“There is no benefit to tight maternal glucose control in labor among women with GDM,” concluded Dr. Hamel. “Our findings support glucose assessment every 4 hours, with intervention for blood glucose levels less than 60 or higher than 120 [mg/dL].”

Dr. Hamel reported no outside sources of funding and no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Hamel M et al. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2019 Jan. 220;1:S36, Abstract 44.

LAS VEGAS – There was no difference in first neonatal glucose level or glucose levels within the first 24 hours of life when women with gestational diabetes received strict, rather than liberalized, glucose management in labor.

In a study of 76 women with gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM), the mean first blood glucose level was 53 mg/dL for neonates born to the 38 mothers who received tight glucose control during labor; for those born to the 38 women who received liberalized control, mean first glucose level was 56 mg/dL (interquartile ranges, 22-85 mg/dL and 27-126 mg/dL, respectively; P = .56).

Secondary outcomes tracked in the study included the proportion of neonates whose glucose levels were low (defined as less than 40 mg/dL) at birth. This figure was identical in both groups, at 24%.

These findings ran counter to the hypothesis that Maureen Hamel, MD, and her colleagues at Brown University, Providence, R.I., had formulated – that neonates whose mothers had tight intrapartum glucose control would have lower rates of neonatal hypoglycemia than those born to women with liberalized intrapartum control.

Although the differences did not reach statistical significance, numerically more infants in the tight-control group required any intervention for hypoglycemia (45% vs. 32%; P = .35) or intravenous intervention for hypoglycemia (11% vs 0%; P = .35). Neonatal ICU admission was required for 13% of the tight-control neonates versus 3% of the liberalized-control group (P = .20).

“A protocol aimed at tight maternal glucose management in labor, compared to liberalized management, for women with GDM, did not result in a lower rate of neonatal hypoglycemia and was associated with mean neonatal glucose closer to hypoglycemia [40 mg/dL] in the first 24 hours of life,” said Dr. Hamel, discussing the findings of her award-winning abstract at the meeting presented by the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine.

Women were included if they were at least 18 years old with a singleton pregnancy and a diagnosis of gestational diabetes. Participants received care through a specialized program for pregnant women with diabetes; they were considered to have GDM if they had at least two abnormal values from a 100-g, 3-hour glucose tolerance test (GTT) or had a blood glucose reading of at least 200 mg/dL from a 1-hour 50-g GTT. About two-thirds of women required medical management of GDM; about 80% received labor induction at 39 weeks’ gestation.

At 36 weeks’ gestation, participants were block-randomized 1:1 to receive tight or liberalized intrapartum blood glucose control, with allocation unknown to both providers and patients until participants were admitted for delivery. Neonatal providers were blinded as to allocation throughout the admission. “In the tight glucose control group, point-of-care glucose was assessed hourly,” said Dr. Hamel. “Goal glucose levels were 70-100 [mg/dL], and treatment was initiated for a single maternal glucose greater than 100 and less than 60 [mg/dL].”

Those in the liberalized group had blood sugar checked every 4 hours in the absence of symptoms, with a goal blood glucose range of 70-120 mg/dL and treatment initiated for blood glucose over 120 or less than 60 mg/dL.

The increase in older women giving birth partly underlies the increase in GDM, said Dr. Hamel. By 35 years of age, about 15% of women will develop GDM, compared with under 6% for women giving birth between 20 and 24 years of age.

Neonatal hypoglycemia, with associated risks for neonatal ICU admission, seizures, and neurologic injury, is more common in women with GDM, said Dr. Hamel, a maternal-fetal medicine fellow.

There’s wide institutional and geographic variation in intrapartum maternal glucose management, said Dr. Hamel. Even within her own institution, blood sugar might be checked just once in labor, every 2 hours, or every hour, and the threshold for treatment might be set at a maternal blood glucose level over 100, 120, or even 200 mg/dL.

The study benefited from the fact that there was standardized antepartum GDM management in place and that 100% of outcome data were available. Also, the a priori sample size to detect significant between-group differences was obtained, and neonatal providers were blinded as to maternal glucose control strategy. Replication of the study should be both easy and feasible, said Dr. Hamel.

However, only very short-term outcomes were tracked, and the study was not powered to detect differences in such less-frequent neonatal outcomes as neonatal ICU admission.

“There is no benefit to tight maternal glucose control in labor among women with GDM,” concluded Dr. Hamel. “Our findings support glucose assessment every 4 hours, with intervention for blood glucose levels less than 60 or higher than 120 [mg/dL].”

Dr. Hamel reported no outside sources of funding and no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Hamel M et al. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2019 Jan. 220;1:S36, Abstract 44.

LAS VEGAS – There was no difference in first neonatal glucose level or glucose levels within the first 24 hours of life when women with gestational diabetes received strict, rather than liberalized, glucose management in labor.

In a study of 76 women with gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM), the mean first blood glucose level was 53 mg/dL for neonates born to the 38 mothers who received tight glucose control during labor; for those born to the 38 women who received liberalized control, mean first glucose level was 56 mg/dL (interquartile ranges, 22-85 mg/dL and 27-126 mg/dL, respectively; P = .56).

Secondary outcomes tracked in the study included the proportion of neonates whose glucose levels were low (defined as less than 40 mg/dL) at birth. This figure was identical in both groups, at 24%.

These findings ran counter to the hypothesis that Maureen Hamel, MD, and her colleagues at Brown University, Providence, R.I., had formulated – that neonates whose mothers had tight intrapartum glucose control would have lower rates of neonatal hypoglycemia than those born to women with liberalized intrapartum control.

Although the differences did not reach statistical significance, numerically more infants in the tight-control group required any intervention for hypoglycemia (45% vs. 32%; P = .35) or intravenous intervention for hypoglycemia (11% vs 0%; P = .35). Neonatal ICU admission was required for 13% of the tight-control neonates versus 3% of the liberalized-control group (P = .20).

“A protocol aimed at tight maternal glucose management in labor, compared to liberalized management, for women with GDM, did not result in a lower rate of neonatal hypoglycemia and was associated with mean neonatal glucose closer to hypoglycemia [40 mg/dL] in the first 24 hours of life,” said Dr. Hamel, discussing the findings of her award-winning abstract at the meeting presented by the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine.

Women were included if they were at least 18 years old with a singleton pregnancy and a diagnosis of gestational diabetes. Participants received care through a specialized program for pregnant women with diabetes; they were considered to have GDM if they had at least two abnormal values from a 100-g, 3-hour glucose tolerance test (GTT) or had a blood glucose reading of at least 200 mg/dL from a 1-hour 50-g GTT. About two-thirds of women required medical management of GDM; about 80% received labor induction at 39 weeks’ gestation.

At 36 weeks’ gestation, participants were block-randomized 1:1 to receive tight or liberalized intrapartum blood glucose control, with allocation unknown to both providers and patients until participants were admitted for delivery. Neonatal providers were blinded as to allocation throughout the admission. “In the tight glucose control group, point-of-care glucose was assessed hourly,” said Dr. Hamel. “Goal glucose levels were 70-100 [mg/dL], and treatment was initiated for a single maternal glucose greater than 100 and less than 60 [mg/dL].”

Those in the liberalized group had blood sugar checked every 4 hours in the absence of symptoms, with a goal blood glucose range of 70-120 mg/dL and treatment initiated for blood glucose over 120 or less than 60 mg/dL.

The increase in older women giving birth partly underlies the increase in GDM, said Dr. Hamel. By 35 years of age, about 15% of women will develop GDM, compared with under 6% for women giving birth between 20 and 24 years of age.

Neonatal hypoglycemia, with associated risks for neonatal ICU admission, seizures, and neurologic injury, is more common in women with GDM, said Dr. Hamel, a maternal-fetal medicine fellow.

There’s wide institutional and geographic variation in intrapartum maternal glucose management, said Dr. Hamel. Even within her own institution, blood sugar might be checked just once in labor, every 2 hours, or every hour, and the threshold for treatment might be set at a maternal blood glucose level over 100, 120, or even 200 mg/dL.

The study benefited from the fact that there was standardized antepartum GDM management in place and that 100% of outcome data were available. Also, the a priori sample size to detect significant between-group differences was obtained, and neonatal providers were blinded as to maternal glucose control strategy. Replication of the study should be both easy and feasible, said Dr. Hamel.

However, only very short-term outcomes were tracked, and the study was not powered to detect differences in such less-frequent neonatal outcomes as neonatal ICU admission.

“There is no benefit to tight maternal glucose control in labor among women with GDM,” concluded Dr. Hamel. “Our findings support glucose assessment every 4 hours, with intervention for blood glucose levels less than 60 or higher than 120 [mg/dL].”

Dr. Hamel reported no outside sources of funding and no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Hamel M et al. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2019 Jan. 220;1:S36, Abstract 44.

REPORTING FROM THE PREGNANCY MEETING

Barancik award winner probes role of fibrinogen in MS

DALLAS – The National Multiple Sclerosis society has awarded the 2018 Barancik Prize for Innovation in Multiple Sclerosis Research to Katerina Akassoglou, PhD.

Dr. Akassoglou laid out the course of research into the role of fibrinogen in multiple sclerosis and other neurodegenerative disorders during her talk at the meeting held by the Americas Committee for Treatment and Research in Multiple Sclerosis.

Dr. Akassoglou and her collaborators questioned the received wisdom about what happens when the brain’s vasculature is disrupted, she said in a video interview. “Fibrinogen was studied for several decades as only a marker of blood-brain barrier disruption. We asked the question, ‘Is it possible that it’s not only a marker, but it also plays a role in disease pathogenesis?’ ”

Over the years, said Dr. Akassoglou, she and her collaborators have developed tools “to dissect this chicken-and-egg question.” A key answer came when the researchers found that when fibrinogen leaks through the vasculature into brain tissue, it can promote inflammatory processes. “At the same time, it induced pathogenic responses in brain immune cells, causing them to be toxic to neuronal cells.”

“Using genetic models of depleting fibrinogen, or blocking its interactions with immune receptors, provided compelling data that this could be an important target for neurodegeneration and neuroinflammation,” said Dr. Akassoglou, professor of neurology at the University of California, San Francisco.

The problem came in trying to find a way to block or deplete fibrinogen inside central nervous system tissue without inactivating it throughout the circulation, since it’s essential for hemostasis.

A promising answer to this problem lies in an investigational monoclonal antibody that binds selectively to sites on fibrinogen that are activated in the brain but are not involved with fibrinogen’s usual role in the clotting cascade in the peripheral circulation, she said.

DALLAS – The National Multiple Sclerosis society has awarded the 2018 Barancik Prize for Innovation in Multiple Sclerosis Research to Katerina Akassoglou, PhD.

Dr. Akassoglou laid out the course of research into the role of fibrinogen in multiple sclerosis and other neurodegenerative disorders during her talk at the meeting held by the Americas Committee for Treatment and Research in Multiple Sclerosis.

Dr. Akassoglou and her collaborators questioned the received wisdom about what happens when the brain’s vasculature is disrupted, she said in a video interview. “Fibrinogen was studied for several decades as only a marker of blood-brain barrier disruption. We asked the question, ‘Is it possible that it’s not only a marker, but it also plays a role in disease pathogenesis?’ ”

Over the years, said Dr. Akassoglou, she and her collaborators have developed tools “to dissect this chicken-and-egg question.” A key answer came when the researchers found that when fibrinogen leaks through the vasculature into brain tissue, it can promote inflammatory processes. “At the same time, it induced pathogenic responses in brain immune cells, causing them to be toxic to neuronal cells.”

“Using genetic models of depleting fibrinogen, or blocking its interactions with immune receptors, provided compelling data that this could be an important target for neurodegeneration and neuroinflammation,” said Dr. Akassoglou, professor of neurology at the University of California, San Francisco.

The problem came in trying to find a way to block or deplete fibrinogen inside central nervous system tissue without inactivating it throughout the circulation, since it’s essential for hemostasis.

A promising answer to this problem lies in an investigational monoclonal antibody that binds selectively to sites on fibrinogen that are activated in the brain but are not involved with fibrinogen’s usual role in the clotting cascade in the peripheral circulation, she said.

DALLAS – The National Multiple Sclerosis society has awarded the 2018 Barancik Prize for Innovation in Multiple Sclerosis Research to Katerina Akassoglou, PhD.

Dr. Akassoglou laid out the course of research into the role of fibrinogen in multiple sclerosis and other neurodegenerative disorders during her talk at the meeting held by the Americas Committee for Treatment and Research in Multiple Sclerosis.

Dr. Akassoglou and her collaborators questioned the received wisdom about what happens when the brain’s vasculature is disrupted, she said in a video interview. “Fibrinogen was studied for several decades as only a marker of blood-brain barrier disruption. We asked the question, ‘Is it possible that it’s not only a marker, but it also plays a role in disease pathogenesis?’ ”

Over the years, said Dr. Akassoglou, she and her collaborators have developed tools “to dissect this chicken-and-egg question.” A key answer came when the researchers found that when fibrinogen leaks through the vasculature into brain tissue, it can promote inflammatory processes. “At the same time, it induced pathogenic responses in brain immune cells, causing them to be toxic to neuronal cells.”

“Using genetic models of depleting fibrinogen, or blocking its interactions with immune receptors, provided compelling data that this could be an important target for neurodegeneration and neuroinflammation,” said Dr. Akassoglou, professor of neurology at the University of California, San Francisco.

The problem came in trying to find a way to block or deplete fibrinogen inside central nervous system tissue without inactivating it throughout the circulation, since it’s essential for hemostasis.

A promising answer to this problem lies in an investigational monoclonal antibody that binds selectively to sites on fibrinogen that are activated in the brain but are not involved with fibrinogen’s usual role in the clotting cascade in the peripheral circulation, she said.

REPORTING FROM ACTRIMS FORUM 2019

From bedside to bench to bedside: Derisking MS research

DALLAS – Rhonda Voskuhl, MD, delivered the Kenneth P. Johnson Memorial lecture at the meeting held by the Americas Committee for Treatment and Research in Multiple Sclerosis. In an hour-long talk, Dr. Voskuhl outlined her research approach, which she terms the “bedside to bench to bedside” strategy.

“My view has been that, when we start out research based on a molecule, we don’t really know for sure its clinical relevance. It’s kind of high risk, because you could go through a lot of work, for many years,” she said in a video interview. When work begins in vitro, the researcher runs the risk of proceeding from test tubes, to animal experiments, and then to people, “and then ultimately finding out that it’s not relevant,” said Dr. Voskuhl, director of the multiple sclerosis (MS) program and Jack H. Skirball Chair of Multiple Sclerosis Research at the University of California, Los Angeles.

“And so I just thought, to derisk this whole thing, I think I want to start at the end and then work backwards,” by choosing a physiologically relevant manifestation of MS, she said. “We know that there’s something there. ... All we have to do is figure it out.”

In iterative fashion, Dr. Voskuhl proceeds from the clinical observation, “which we know is true, and then go to the laboratory bench and figure it out by doing a lot of manipulation and isolation of one thing versus another.”

“When you put this in the context of cell-specific and region-specific gene expression, to find disability-specific treatments,” Dr. Voskuhl said, this targeted approach helps address the fact that MS patients differ so much in their presentations and disease course.

“We know that, for example, the neuronal cells differ, and some of the neurotrophic cells differ from pathway to pathway; furthermore, what’s important is that oligocytes and astrocytes and dendrocytes have been shown to differ from one region of the brain and spinal cord to another. So these clearly would have different gene expression signatures, potentially posing different targets for treatment,” Dr. Voskuhl said.

DALLAS – Rhonda Voskuhl, MD, delivered the Kenneth P. Johnson Memorial lecture at the meeting held by the Americas Committee for Treatment and Research in Multiple Sclerosis. In an hour-long talk, Dr. Voskuhl outlined her research approach, which she terms the “bedside to bench to bedside” strategy.

“My view has been that, when we start out research based on a molecule, we don’t really know for sure its clinical relevance. It’s kind of high risk, because you could go through a lot of work, for many years,” she said in a video interview. When work begins in vitro, the researcher runs the risk of proceeding from test tubes, to animal experiments, and then to people, “and then ultimately finding out that it’s not relevant,” said Dr. Voskuhl, director of the multiple sclerosis (MS) program and Jack H. Skirball Chair of Multiple Sclerosis Research at the University of California, Los Angeles.

“And so I just thought, to derisk this whole thing, I think I want to start at the end and then work backwards,” by choosing a physiologically relevant manifestation of MS, she said. “We know that there’s something there. ... All we have to do is figure it out.”

In iterative fashion, Dr. Voskuhl proceeds from the clinical observation, “which we know is true, and then go to the laboratory bench and figure it out by doing a lot of manipulation and isolation of one thing versus another.”

“When you put this in the context of cell-specific and region-specific gene expression, to find disability-specific treatments,” Dr. Voskuhl said, this targeted approach helps address the fact that MS patients differ so much in their presentations and disease course.

“We know that, for example, the neuronal cells differ, and some of the neurotrophic cells differ from pathway to pathway; furthermore, what’s important is that oligocytes and astrocytes and dendrocytes have been shown to differ from one region of the brain and spinal cord to another. So these clearly would have different gene expression signatures, potentially posing different targets for treatment,” Dr. Voskuhl said.

DALLAS – Rhonda Voskuhl, MD, delivered the Kenneth P. Johnson Memorial lecture at the meeting held by the Americas Committee for Treatment and Research in Multiple Sclerosis. In an hour-long talk, Dr. Voskuhl outlined her research approach, which she terms the “bedside to bench to bedside” strategy.

“My view has been that, when we start out research based on a molecule, we don’t really know for sure its clinical relevance. It’s kind of high risk, because you could go through a lot of work, for many years,” she said in a video interview. When work begins in vitro, the researcher runs the risk of proceeding from test tubes, to animal experiments, and then to people, “and then ultimately finding out that it’s not relevant,” said Dr. Voskuhl, director of the multiple sclerosis (MS) program and Jack H. Skirball Chair of Multiple Sclerosis Research at the University of California, Los Angeles.

“And so I just thought, to derisk this whole thing, I think I want to start at the end and then work backwards,” by choosing a physiologically relevant manifestation of MS, she said. “We know that there’s something there. ... All we have to do is figure it out.”

In iterative fashion, Dr. Voskuhl proceeds from the clinical observation, “which we know is true, and then go to the laboratory bench and figure it out by doing a lot of manipulation and isolation of one thing versus another.”

“When you put this in the context of cell-specific and region-specific gene expression, to find disability-specific treatments,” Dr. Voskuhl said, this targeted approach helps address the fact that MS patients differ so much in their presentations and disease course.

“We know that, for example, the neuronal cells differ, and some of the neurotrophic cells differ from pathway to pathway; furthermore, what’s important is that oligocytes and astrocytes and dendrocytes have been shown to differ from one region of the brain and spinal cord to another. So these clearly would have different gene expression signatures, potentially posing different targets for treatment,” Dr. Voskuhl said.

REPORTING FROM ACTRIMS FORUM 2019

MS research: “Our patients can’t wait” for conventional techniques

DALLAS – The time is right to bring big data and high-horsepower computation to the thorniest problems in multiple sclerosis (MS) research, said Jennifer Graves, MD, who cochaired the closing session at the meeting held by the Americas Committee for Research and Treatment in Multiple Sclerosis. The session focused on harnessing machine learning, deep learning, and the newest noninvasive observational techniques to move research and clinical care forward.

“We’ve reached a point in MS research where we’re hitting some stumbling blocks. And a lot of those stumbling blocks are related to how well and how precisely we can measure phenotype in MS. The reason that’s important is that our next frontier is treating progressive MS – and what that requires is finding things that let us know what’s happening at the biological level, so that we can screen drugs faster. We can’t afford to have 3- to 5-year clinical trials. ... Because our patients can’t wait,” said Dr. Graves, an associate professor of neuroscience at the University of California, San Diego.

“We can use all sorts of big data sources, whether it’s the rich imaging data we get on patients when they go into the MRI scanner, whether it’s wearable sensors,” or even newer technology, Dr. Graves said. “We can use technology to give us the sensitivity that we’ve been missing.”

Wearable technology, including accelerometers, can track physical activity that tracks with outcomes in MS, she added. As the tech armament increases, so will data available for analysis and correlation.

However, the key to progress will be to focus on technology that measures change over time. “This is the key: sensitivity to change over time. A lot of things can be associated with disability,” said Dr. Graves, but the key is tracking what changes in an individual patient with disease progression, “so that we can detect treatment effects or side effects.”

DALLAS – The time is right to bring big data and high-horsepower computation to the thorniest problems in multiple sclerosis (MS) research, said Jennifer Graves, MD, who cochaired the closing session at the meeting held by the Americas Committee for Research and Treatment in Multiple Sclerosis. The session focused on harnessing machine learning, deep learning, and the newest noninvasive observational techniques to move research and clinical care forward.

“We’ve reached a point in MS research where we’re hitting some stumbling blocks. And a lot of those stumbling blocks are related to how well and how precisely we can measure phenotype in MS. The reason that’s important is that our next frontier is treating progressive MS – and what that requires is finding things that let us know what’s happening at the biological level, so that we can screen drugs faster. We can’t afford to have 3- to 5-year clinical trials. ... Because our patients can’t wait,” said Dr. Graves, an associate professor of neuroscience at the University of California, San Diego.

“We can use all sorts of big data sources, whether it’s the rich imaging data we get on patients when they go into the MRI scanner, whether it’s wearable sensors,” or even newer technology, Dr. Graves said. “We can use technology to give us the sensitivity that we’ve been missing.”

Wearable technology, including accelerometers, can track physical activity that tracks with outcomes in MS, she added. As the tech armament increases, so will data available for analysis and correlation.

However, the key to progress will be to focus on technology that measures change over time. “This is the key: sensitivity to change over time. A lot of things can be associated with disability,” said Dr. Graves, but the key is tracking what changes in an individual patient with disease progression, “so that we can detect treatment effects or side effects.”

DALLAS – The time is right to bring big data and high-horsepower computation to the thorniest problems in multiple sclerosis (MS) research, said Jennifer Graves, MD, who cochaired the closing session at the meeting held by the Americas Committee for Research and Treatment in Multiple Sclerosis. The session focused on harnessing machine learning, deep learning, and the newest noninvasive observational techniques to move research and clinical care forward.

“We’ve reached a point in MS research where we’re hitting some stumbling blocks. And a lot of those stumbling blocks are related to how well and how precisely we can measure phenotype in MS. The reason that’s important is that our next frontier is treating progressive MS – and what that requires is finding things that let us know what’s happening at the biological level, so that we can screen drugs faster. We can’t afford to have 3- to 5-year clinical trials. ... Because our patients can’t wait,” said Dr. Graves, an associate professor of neuroscience at the University of California, San Diego.

“We can use all sorts of big data sources, whether it’s the rich imaging data we get on patients when they go into the MRI scanner, whether it’s wearable sensors,” or even newer technology, Dr. Graves said. “We can use technology to give us the sensitivity that we’ve been missing.”

Wearable technology, including accelerometers, can track physical activity that tracks with outcomes in MS, she added. As the tech armament increases, so will data available for analysis and correlation.

However, the key to progress will be to focus on technology that measures change over time. “This is the key: sensitivity to change over time. A lot of things can be associated with disability,” said Dr. Graves, but the key is tracking what changes in an individual patient with disease progression, “so that we can detect treatment effects or side effects.”

REPORTING FROM ACTRIMS FORUM 2019

Medical tourism for MS stem cell therapy is common

DALLAS – “Stem cell therapy is something that has been a topic of interest for neurologists for a while,” said Wijdan Rai, MD, speaking at the meeting presented by the American Committee for Treatment and Research in Multiple Sclerosis.

However, “stem cell tourism is notoriously difficult to study, because it’s not regulated; there’s no database we can access to try to figure out what exactly is going on in these clinics,” said Dr. Rai.

Dr. Rai, a neurology resident at the Ohio State University, Columbus, said that she and her colleagues had noticed patients with multiple sclerosis (MS) were asking more frequently about stem cell therapies, and mesenchymal stem cell therapy in particular.

To translate these anecdotal observations into more concrete data, Dr. Rai and her colleagues surveyed academic neurologists in the outpatient setting to see if their patients were asking them about medical tourism for stem cell therapy. Additionally, they were asked about patients who actually had sought out the therapy and if there were adverse reactions from stem cell therapy.

The 25-item questionnaire was sent to academic neurologists via an online survey tool called Synapse through the American Academy of Neurology. Dr. Rai and her colleagues found that over 90% of respondents had been asked about stem cell therapies and that 25% of respondents said their patients had some kind of complication from the treatment.

“Most commonly, it was some variation of an infection, like meningitis, encephalitis, or hepatitis C,” said Dr. Rai. Other physicians reported that their patients had spinal cord tumors, deterioration of MS, or stroke.

with this evidence in hand, she hopes that a fact sheet can be developed and hosted on a website so physicians can point their patients to evidence-based information about stem cell therapies in MS.

DALLAS – “Stem cell therapy is something that has been a topic of interest for neurologists for a while,” said Wijdan Rai, MD, speaking at the meeting presented by the American Committee for Treatment and Research in Multiple Sclerosis.

However, “stem cell tourism is notoriously difficult to study, because it’s not regulated; there’s no database we can access to try to figure out what exactly is going on in these clinics,” said Dr. Rai.

Dr. Rai, a neurology resident at the Ohio State University, Columbus, said that she and her colleagues had noticed patients with multiple sclerosis (MS) were asking more frequently about stem cell therapies, and mesenchymal stem cell therapy in particular.

To translate these anecdotal observations into more concrete data, Dr. Rai and her colleagues surveyed academic neurologists in the outpatient setting to see if their patients were asking them about medical tourism for stem cell therapy. Additionally, they were asked about patients who actually had sought out the therapy and if there were adverse reactions from stem cell therapy.

The 25-item questionnaire was sent to academic neurologists via an online survey tool called Synapse through the American Academy of Neurology. Dr. Rai and her colleagues found that over 90% of respondents had been asked about stem cell therapies and that 25% of respondents said their patients had some kind of complication from the treatment.

“Most commonly, it was some variation of an infection, like meningitis, encephalitis, or hepatitis C,” said Dr. Rai. Other physicians reported that their patients had spinal cord tumors, deterioration of MS, or stroke.

with this evidence in hand, she hopes that a fact sheet can be developed and hosted on a website so physicians can point their patients to evidence-based information about stem cell therapies in MS.

DALLAS – “Stem cell therapy is something that has been a topic of interest for neurologists for a while,” said Wijdan Rai, MD, speaking at the meeting presented by the American Committee for Treatment and Research in Multiple Sclerosis.

However, “stem cell tourism is notoriously difficult to study, because it’s not regulated; there’s no database we can access to try to figure out what exactly is going on in these clinics,” said Dr. Rai.

Dr. Rai, a neurology resident at the Ohio State University, Columbus, said that she and her colleagues had noticed patients with multiple sclerosis (MS) were asking more frequently about stem cell therapies, and mesenchymal stem cell therapy in particular.

To translate these anecdotal observations into more concrete data, Dr. Rai and her colleagues surveyed academic neurologists in the outpatient setting to see if their patients were asking them about medical tourism for stem cell therapy. Additionally, they were asked about patients who actually had sought out the therapy and if there were adverse reactions from stem cell therapy.

The 25-item questionnaire was sent to academic neurologists via an online survey tool called Synapse through the American Academy of Neurology. Dr. Rai and her colleagues found that over 90% of respondents had been asked about stem cell therapies and that 25% of respondents said their patients had some kind of complication from the treatment.

“Most commonly, it was some variation of an infection, like meningitis, encephalitis, or hepatitis C,” said Dr. Rai. Other physicians reported that their patients had spinal cord tumors, deterioration of MS, or stroke.

with this evidence in hand, she hopes that a fact sheet can be developed and hosted on a website so physicians can point their patients to evidence-based information about stem cell therapies in MS.

REPORTING FROM ACTRIMS FORUM 2019

Smartphone assessment of motor, cognitive function in MS extends clinicians’ reach

DALLAS –

Alexandra Boukhvalova, a medical student at the University of Maryland School of Medicine, Baltimore, and her collaborators developed an interactive smartphone app to assess some aspects of cognitive and motor function for patients with multiple sclerosis (MS). Their findings were reported during a poster session at the meeting held by the American Society for Prevention and Treatment in Multiple Sclerosis.

“The clinician assessment is an hour-long assessment; it requires a trained neurologist,” Ms. Boukhvalova pointed out. In thinking about how app-based assessment could augment the clinical exam, she and her collaborators realized that “a lot of the neurologic exam is still quite subjective – so is there a way that we can make that exam more objective and quantifiable and also add a little bit of ease with accessibility and mobility?

“We created a suite of test apps ... to assess different neurological systems, ranging from motor function, cognitive and visual dysfunction, general fatigue, and strength,” she said. The apps included tapping tests and balloon-popping tasks, along with measures to give some indication of spasticity by assessing the smoothness of movements.

Participants completed the testing both in the clinic and from home. “We did not need an investigator present for patients to be able to complete the tests,” said Ms. Boukhvalova.

Ms. Boukhvalova and her colleagues compared performance on the gamified tasks between patients with MS and healthy controls. For all tasks, the participants with MS could clearly be differentiated from the healthy participants.

A further plus was that “The patients almost viewed these tests as games.” They reported that they enjoyed completing them, said Ms. Boukhvalova, adding that app-based assessments also offer an additional point of connection between MS patients and specialists, whom they may only see annually or semiannually.

Further app development may focus on utilizing sensor and accelerometer functions in smartphones to perform more natural and sophisticated motor analysis to look at gait and gross motor functioning, she said.

DALLAS –

Alexandra Boukhvalova, a medical student at the University of Maryland School of Medicine, Baltimore, and her collaborators developed an interactive smartphone app to assess some aspects of cognitive and motor function for patients with multiple sclerosis (MS). Their findings were reported during a poster session at the meeting held by the American Society for Prevention and Treatment in Multiple Sclerosis.

“The clinician assessment is an hour-long assessment; it requires a trained neurologist,” Ms. Boukhvalova pointed out. In thinking about how app-based assessment could augment the clinical exam, she and her collaborators realized that “a lot of the neurologic exam is still quite subjective – so is there a way that we can make that exam more objective and quantifiable and also add a little bit of ease with accessibility and mobility?

“We created a suite of test apps ... to assess different neurological systems, ranging from motor function, cognitive and visual dysfunction, general fatigue, and strength,” she said. The apps included tapping tests and balloon-popping tasks, along with measures to give some indication of spasticity by assessing the smoothness of movements.

Participants completed the testing both in the clinic and from home. “We did not need an investigator present for patients to be able to complete the tests,” said Ms. Boukhvalova.

Ms. Boukhvalova and her colleagues compared performance on the gamified tasks between patients with MS and healthy controls. For all tasks, the participants with MS could clearly be differentiated from the healthy participants.

A further plus was that “The patients almost viewed these tests as games.” They reported that they enjoyed completing them, said Ms. Boukhvalova, adding that app-based assessments also offer an additional point of connection between MS patients and specialists, whom they may only see annually or semiannually.

Further app development may focus on utilizing sensor and accelerometer functions in smartphones to perform more natural and sophisticated motor analysis to look at gait and gross motor functioning, she said.

DALLAS –

Alexandra Boukhvalova, a medical student at the University of Maryland School of Medicine, Baltimore, and her collaborators developed an interactive smartphone app to assess some aspects of cognitive and motor function for patients with multiple sclerosis (MS). Their findings were reported during a poster session at the meeting held by the American Society for Prevention and Treatment in Multiple Sclerosis.

“The clinician assessment is an hour-long assessment; it requires a trained neurologist,” Ms. Boukhvalova pointed out. In thinking about how app-based assessment could augment the clinical exam, she and her collaborators realized that “a lot of the neurologic exam is still quite subjective – so is there a way that we can make that exam more objective and quantifiable and also add a little bit of ease with accessibility and mobility?

“We created a suite of test apps ... to assess different neurological systems, ranging from motor function, cognitive and visual dysfunction, general fatigue, and strength,” she said. The apps included tapping tests and balloon-popping tasks, along with measures to give some indication of spasticity by assessing the smoothness of movements.

Participants completed the testing both in the clinic and from home. “We did not need an investigator present for patients to be able to complete the tests,” said Ms. Boukhvalova.

Ms. Boukhvalova and her colleagues compared performance on the gamified tasks between patients with MS and healthy controls. For all tasks, the participants with MS could clearly be differentiated from the healthy participants.

A further plus was that “The patients almost viewed these tests as games.” They reported that they enjoyed completing them, said Ms. Boukhvalova, adding that app-based assessments also offer an additional point of connection between MS patients and specialists, whom they may only see annually or semiannually.

Further app development may focus on utilizing sensor and accelerometer functions in smartphones to perform more natural and sophisticated motor analysis to look at gait and gross motor functioning, she said.

REPORTING FROM ACTRIMS FORUM 2019

ACOG: Avoid inductions before 39 weeks unless medically necessary

Babies should not be delivered before 39 0/7 weeks’ gestation by means besides spontaneous vaginal delivery, in the absence of medical indications for an earlier delivery.

wrote the authors of the new opinion, developed by the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists committee on obstetric practice and the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine.

The opinion, which replaces a 2013 statement, clarifies that their recommendations include avoiding cesarean delivery, labor induction, and cervical ripening before 39 0/7 weeks of gestation, unless a medical indication exists for earlier delivery.

The new opinion statement relied, in part, on a recent systematic review finding that late-preterm and early-term children do not fare as well as do term-delivered children in a variety of cognitive and educational domains. The opinion statement acknowledges that it’s not clear why children delivered earlier are showing performance difficulties and that it is possible that medical indications for an earlier delivery contributed to the differences.

Immediate outcomes for neonates delivered in the late preterm and early term period also are worse, compared with those delivered at term, according to several studies cited in the opinion. For example, composite morbidity was higher for infants delivered at both 37 and 38 weeks gestation, compared with those delivered at 39 weeks, with adjusted odds ratios for the composite outcome of 2.1 and 1.5, respectively (N Engl J Med. 2009 Jan 8;360[2]:111-20).

And lung maturity alone should not guide delivery, wrote the authors of the opinion. “Because nonrespiratory morbidities also are increased in early-term deliveries, documentation of fetal pulmonary maturity does not justify an early nonmedically indicated delivery,” they said, adding that physicians should not perform amniocentesis to determine lung maturity in an effort to guide delivery timing.

Because intrapartum demise remains a risk as long as a woman is pregnant, the potential for adverse neonatal outcomes with early delivery has to be balanced against the risk of stillbirth with continued gestation, the opinion authors acknowledged. But, they said, this question has been addressed by “multiple studies using national population level data,” which show that “even as the gestational age at term has increased in response to efforts to reduce early elective delivery, these efforts have not adversely affected stillbirth rates nationally or even in states with the greatest reductions in early elective delivery.”

Formal programs to reduce nonmedically indicated early-term deliveries have been successful. For example, the state of South Carolina achieved a reduction of almost 50% in nonmedically indicated early-term deliveries over the course of just 1 year. The South Carolina Birth Outcomes Initiative led a collaborative effort to institute a “hard-stop” policy against nonmedically indicated early-term deliveries that resulted in an absolute 4.7% decrease in late-preterm birth during 2011-2012. Similar efforts in Oregon and Ohio have reported significant reductions as well, with no increases in adverse neonatal outcomes.

Various policy approaches have been tried to achieve a reduction in nonmedically indicated late-preterm and early-term birth. These range from awareness raising and education, to “soft-stop” policies in which health care providers agree not to deliver before 39 weeks without medical indication, to “hard-stop” policies in which hospitals prohibit the nonindicated deliveries. In one comparative outcomes study, the hard-stop policy was the most effective, with a drop from 8.2% to 1.7% in nonindicated early deliveries, but the soft-stop policy also produced a decrease from 8.4% to 3.3% (P = .007 and .025, respectively). The educational approach didn’t produce a significant drop in nonmedically indicated early deliveries (Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2010 Nov;203[5]:449.e1-6).

In a separate, preexisting statement (Obstet Gynecol. 2019;133:e151-5), ACOG has outlined the management of medically indicated late-preterm and early-term deliveries and has developed an app (www.acog.org/acogapp) as a decision tool for indicated deliveries.

Examples cited by the current opinion statement authors of medical indications for early delivery include maternal factors such as preeclampsia, gestational hypertension, and poorly controlled diabetes. Placentation problems, fetal growth restriction, and prior cesarean deliveries also may warrant earlier delivery, as may a host of other complications. If an earlier delivery is planned, the committee authors recommend full discussion with the patient and clear documentation of the indications and discussion.

Babies should not be delivered before 39 0/7 weeks’ gestation by means besides spontaneous vaginal delivery, in the absence of medical indications for an earlier delivery.

wrote the authors of the new opinion, developed by the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists committee on obstetric practice and the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine.

The opinion, which replaces a 2013 statement, clarifies that their recommendations include avoiding cesarean delivery, labor induction, and cervical ripening before 39 0/7 weeks of gestation, unless a medical indication exists for earlier delivery.

The new opinion statement relied, in part, on a recent systematic review finding that late-preterm and early-term children do not fare as well as do term-delivered children in a variety of cognitive and educational domains. The opinion statement acknowledges that it’s not clear why children delivered earlier are showing performance difficulties and that it is possible that medical indications for an earlier delivery contributed to the differences.

Immediate outcomes for neonates delivered in the late preterm and early term period also are worse, compared with those delivered at term, according to several studies cited in the opinion. For example, composite morbidity was higher for infants delivered at both 37 and 38 weeks gestation, compared with those delivered at 39 weeks, with adjusted odds ratios for the composite outcome of 2.1 and 1.5, respectively (N Engl J Med. 2009 Jan 8;360[2]:111-20).

And lung maturity alone should not guide delivery, wrote the authors of the opinion. “Because nonrespiratory morbidities also are increased in early-term deliveries, documentation of fetal pulmonary maturity does not justify an early nonmedically indicated delivery,” they said, adding that physicians should not perform amniocentesis to determine lung maturity in an effort to guide delivery timing.

Because intrapartum demise remains a risk as long as a woman is pregnant, the potential for adverse neonatal outcomes with early delivery has to be balanced against the risk of stillbirth with continued gestation, the opinion authors acknowledged. But, they said, this question has been addressed by “multiple studies using national population level data,” which show that “even as the gestational age at term has increased in response to efforts to reduce early elective delivery, these efforts have not adversely affected stillbirth rates nationally or even in states with the greatest reductions in early elective delivery.”

Formal programs to reduce nonmedically indicated early-term deliveries have been successful. For example, the state of South Carolina achieved a reduction of almost 50% in nonmedically indicated early-term deliveries over the course of just 1 year. The South Carolina Birth Outcomes Initiative led a collaborative effort to institute a “hard-stop” policy against nonmedically indicated early-term deliveries that resulted in an absolute 4.7% decrease in late-preterm birth during 2011-2012. Similar efforts in Oregon and Ohio have reported significant reductions as well, with no increases in adverse neonatal outcomes.

Various policy approaches have been tried to achieve a reduction in nonmedically indicated late-preterm and early-term birth. These range from awareness raising and education, to “soft-stop” policies in which health care providers agree not to deliver before 39 weeks without medical indication, to “hard-stop” policies in which hospitals prohibit the nonindicated deliveries. In one comparative outcomes study, the hard-stop policy was the most effective, with a drop from 8.2% to 1.7% in nonindicated early deliveries, but the soft-stop policy also produced a decrease from 8.4% to 3.3% (P = .007 and .025, respectively). The educational approach didn’t produce a significant drop in nonmedically indicated early deliveries (Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2010 Nov;203[5]:449.e1-6).

In a separate, preexisting statement (Obstet Gynecol. 2019;133:e151-5), ACOG has outlined the management of medically indicated late-preterm and early-term deliveries and has developed an app (www.acog.org/acogapp) as a decision tool for indicated deliveries.

Examples cited by the current opinion statement authors of medical indications for early delivery include maternal factors such as preeclampsia, gestational hypertension, and poorly controlled diabetes. Placentation problems, fetal growth restriction, and prior cesarean deliveries also may warrant earlier delivery, as may a host of other complications. If an earlier delivery is planned, the committee authors recommend full discussion with the patient and clear documentation of the indications and discussion.

Babies should not be delivered before 39 0/7 weeks’ gestation by means besides spontaneous vaginal delivery, in the absence of medical indications for an earlier delivery.

wrote the authors of the new opinion, developed by the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists committee on obstetric practice and the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine.

The opinion, which replaces a 2013 statement, clarifies that their recommendations include avoiding cesarean delivery, labor induction, and cervical ripening before 39 0/7 weeks of gestation, unless a medical indication exists for earlier delivery.

The new opinion statement relied, in part, on a recent systematic review finding that late-preterm and early-term children do not fare as well as do term-delivered children in a variety of cognitive and educational domains. The opinion statement acknowledges that it’s not clear why children delivered earlier are showing performance difficulties and that it is possible that medical indications for an earlier delivery contributed to the differences.

Immediate outcomes for neonates delivered in the late preterm and early term period also are worse, compared with those delivered at term, according to several studies cited in the opinion. For example, composite morbidity was higher for infants delivered at both 37 and 38 weeks gestation, compared with those delivered at 39 weeks, with adjusted odds ratios for the composite outcome of 2.1 and 1.5, respectively (N Engl J Med. 2009 Jan 8;360[2]:111-20).

And lung maturity alone should not guide delivery, wrote the authors of the opinion. “Because nonrespiratory morbidities also are increased in early-term deliveries, documentation of fetal pulmonary maturity does not justify an early nonmedically indicated delivery,” they said, adding that physicians should not perform amniocentesis to determine lung maturity in an effort to guide delivery timing.

Because intrapartum demise remains a risk as long as a woman is pregnant, the potential for adverse neonatal outcomes with early delivery has to be balanced against the risk of stillbirth with continued gestation, the opinion authors acknowledged. But, they said, this question has been addressed by “multiple studies using national population level data,” which show that “even as the gestational age at term has increased in response to efforts to reduce early elective delivery, these efforts have not adversely affected stillbirth rates nationally or even in states with the greatest reductions in early elective delivery.”

Formal programs to reduce nonmedically indicated early-term deliveries have been successful. For example, the state of South Carolina achieved a reduction of almost 50% in nonmedically indicated early-term deliveries over the course of just 1 year. The South Carolina Birth Outcomes Initiative led a collaborative effort to institute a “hard-stop” policy against nonmedically indicated early-term deliveries that resulted in an absolute 4.7% decrease in late-preterm birth during 2011-2012. Similar efforts in Oregon and Ohio have reported significant reductions as well, with no increases in adverse neonatal outcomes.

Various policy approaches have been tried to achieve a reduction in nonmedically indicated late-preterm and early-term birth. These range from awareness raising and education, to “soft-stop” policies in which health care providers agree not to deliver before 39 weeks without medical indication, to “hard-stop” policies in which hospitals prohibit the nonindicated deliveries. In one comparative outcomes study, the hard-stop policy was the most effective, with a drop from 8.2% to 1.7% in nonindicated early deliveries, but the soft-stop policy also produced a decrease from 8.4% to 3.3% (P = .007 and .025, respectively). The educational approach didn’t produce a significant drop in nonmedically indicated early deliveries (Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2010 Nov;203[5]:449.e1-6).

In a separate, preexisting statement (Obstet Gynecol. 2019;133:e151-5), ACOG has outlined the management of medically indicated late-preterm and early-term deliveries and has developed an app (www.acog.org/acogapp) as a decision tool for indicated deliveries.

Examples cited by the current opinion statement authors of medical indications for early delivery include maternal factors such as preeclampsia, gestational hypertension, and poorly controlled diabetes. Placentation problems, fetal growth restriction, and prior cesarean deliveries also may warrant earlier delivery, as may a host of other complications. If an earlier delivery is planned, the committee authors recommend full discussion with the patient and clear documentation of the indications and discussion.

FROM OBSTETRICS & GYNECOLOGY

Tanuja Chitnis: “It’s the right time” for precision medicine in MS

DALLAS – In an interview at the meeting held by the Americas Committee for Treatment and Research in Multiple Sclerosis, the conference’s cochair, Tanuja Chitnis, MD, explained why this is the right time to take a deep dive into what precision medicine means in MS, for patients and physicians alike.

“We chose the topic of precision medicine for this forum because it’s a really timely issue,” said Dr. Chitnis, noting that there are now over 16 approved treatments for MS, and an increasing recognition that “not every patient has the same disease course.”

“It’s the right time to think about individualized treatment, and not a one-size-fits-all approach,” she said, noting that clinicians and patients stand to benefit from guidance about treatment choices.

“In addition, we are aided by the number of biomarkers that are becoming available,” including quantitative MRI and serum biomarkers. “I think we – as a field – need to understand how to use these in clinical settings in order to guide treatment decisions,” said Dr. Chitnis, professor of neurology at Harvard Medical School, Boston.

Advances in data science are allowing the connection of disparate kinds of data for discovery and hypothesis testing and validation, said Dr. Chitnis, who serves as medical director for the large longitudinal CLIMB study. The study follows about 2,000 patients who have yearly neurologic examinations and brain MRI; serum biomarkers and self-report data are also acquired annually.

“Network science can help in the precision medicine approach to multiple sclerosis, because we have a very clear understanding that MS is a complex disease. It is not one gene; it is not one modality,” she said.

Dr. Chitnis reported that she has received research funding from multiple pharmaceutical companies.

DALLAS – In an interview at the meeting held by the Americas Committee for Treatment and Research in Multiple Sclerosis, the conference’s cochair, Tanuja Chitnis, MD, explained why this is the right time to take a deep dive into what precision medicine means in MS, for patients and physicians alike.

“We chose the topic of precision medicine for this forum because it’s a really timely issue,” said Dr. Chitnis, noting that there are now over 16 approved treatments for MS, and an increasing recognition that “not every patient has the same disease course.”

“It’s the right time to think about individualized treatment, and not a one-size-fits-all approach,” she said, noting that clinicians and patients stand to benefit from guidance about treatment choices.

“In addition, we are aided by the number of biomarkers that are becoming available,” including quantitative MRI and serum biomarkers. “I think we – as a field – need to understand how to use these in clinical settings in order to guide treatment decisions,” said Dr. Chitnis, professor of neurology at Harvard Medical School, Boston.

Advances in data science are allowing the connection of disparate kinds of data for discovery and hypothesis testing and validation, said Dr. Chitnis, who serves as medical director for the large longitudinal CLIMB study. The study follows about 2,000 patients who have yearly neurologic examinations and brain MRI; serum biomarkers and self-report data are also acquired annually.

“Network science can help in the precision medicine approach to multiple sclerosis, because we have a very clear understanding that MS is a complex disease. It is not one gene; it is not one modality,” she said.

Dr. Chitnis reported that she has received research funding from multiple pharmaceutical companies.

DALLAS – In an interview at the meeting held by the Americas Committee for Treatment and Research in Multiple Sclerosis, the conference’s cochair, Tanuja Chitnis, MD, explained why this is the right time to take a deep dive into what precision medicine means in MS, for patients and physicians alike.

“We chose the topic of precision medicine for this forum because it’s a really timely issue,” said Dr. Chitnis, noting that there are now over 16 approved treatments for MS, and an increasing recognition that “not every patient has the same disease course.”

“It’s the right time to think about individualized treatment, and not a one-size-fits-all approach,” she said, noting that clinicians and patients stand to benefit from guidance about treatment choices.

“In addition, we are aided by the number of biomarkers that are becoming available,” including quantitative MRI and serum biomarkers. “I think we – as a field – need to understand how to use these in clinical settings in order to guide treatment decisions,” said Dr. Chitnis, professor of neurology at Harvard Medical School, Boston.

Advances in data science are allowing the connection of disparate kinds of data for discovery and hypothesis testing and validation, said Dr. Chitnis, who serves as medical director for the large longitudinal CLIMB study. The study follows about 2,000 patients who have yearly neurologic examinations and brain MRI; serum biomarkers and self-report data are also acquired annually.

“Network science can help in the precision medicine approach to multiple sclerosis, because we have a very clear understanding that MS is a complex disease. It is not one gene; it is not one modality,” she said.

Dr. Chitnis reported that she has received research funding from multiple pharmaceutical companies.

REPORTING FROM ACTRIMS FORUM 2019

CDC: United States has hit a plateau with HIV

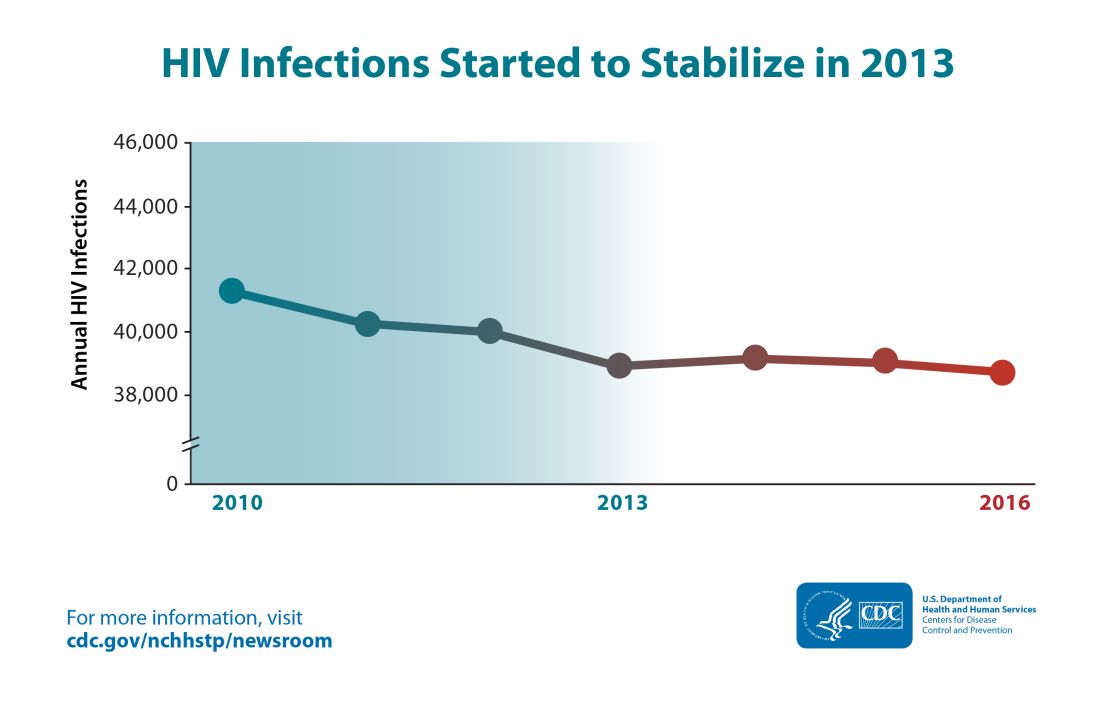

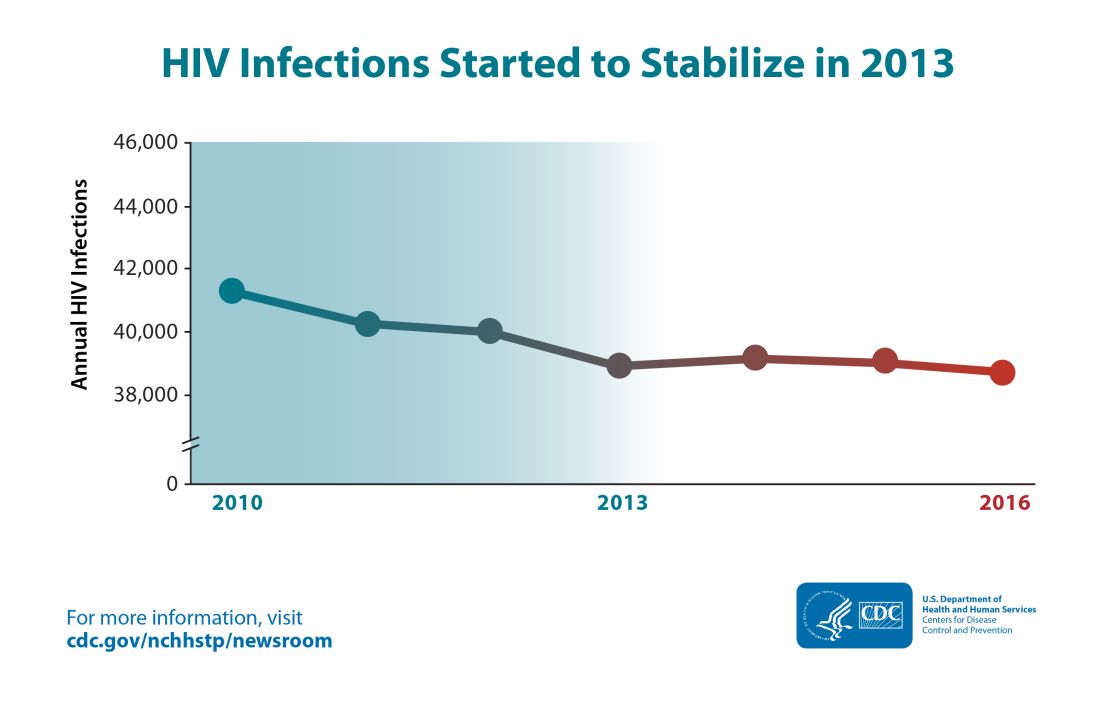

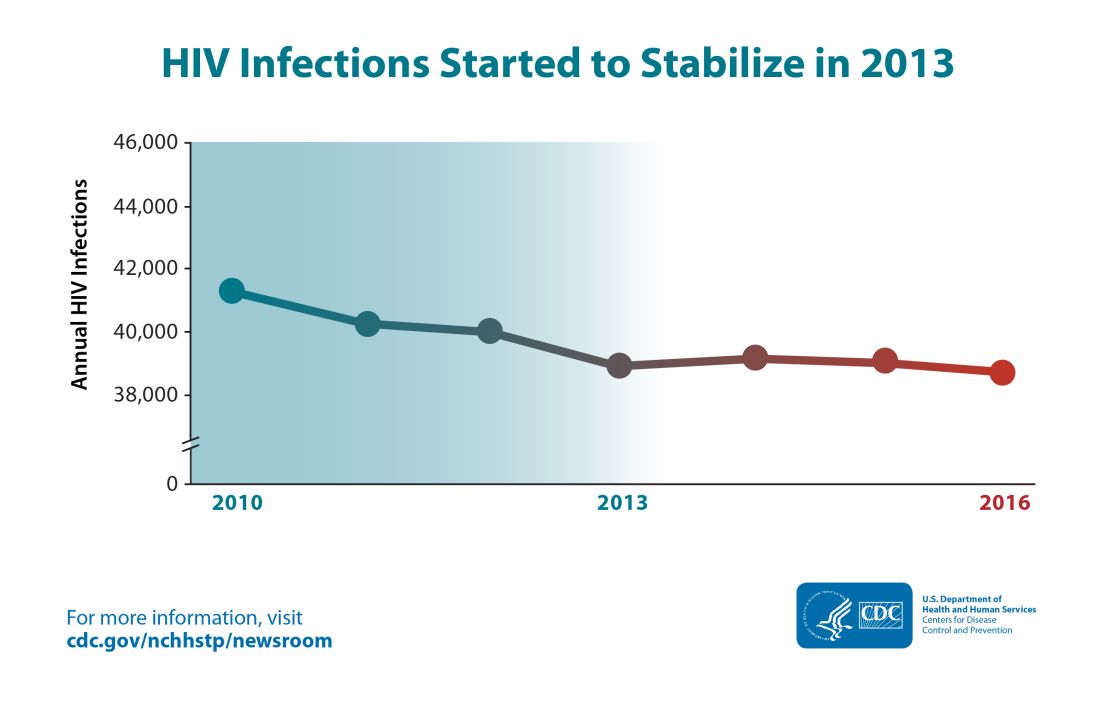

The annual number of new HIV infections has remained stable in recent years, and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention says that’s not good – but solutions are at hand.

Though the estimated number of new HIV infections declined from just under 42,000 per year in 2010 to about 39,000 annually in 2013, that figure was essentially unchanged by 2016, with 38,700 new HIV infections seen that year.

“CDC estimates that the decline in HIV infections has plateaued because effective HIV prevention and treatment are not adequately reaching those who could most benefit from them. These gaps remain particularly troublesome in rural areas and in the South and among disproportionately affected populations like African Americans and Latinos,” said the CDC in a press release accompanying the report.

The report comes soon after President Trump’s State of the Union address, which announced a new multiagency initiative to eliminate the HIV epidemic in the United States, with the goal of reducing new HIV infections by 90% over the next 10 years. The multipronged initiative will implement geographically targeted HIV elimination teams in areas with high HIV prevalence, pulling together federal agencies, local and state governments, and community-level resources.

The initiative, called “Ending the Epidemic: A Plan for America” will combine an intensified approach to early diagnosis and treatment with efforts to boost uptake of pre-exposure prophylaxis for individuals at high risk for HIV infection.

The new CDC report used CD4 counts reported to the National HIV Surveillance System at the time of diagnosis to identify new (incident) cases and to track prevalence. Much of the report is devoted to finely detailed reporting of HIV incidence across sex, age, race/ethnicity, and transmission mode.

Though some groups, such as people who inject drugs, have seen a decrease of about 30% in the annual rate of new HIV cases, new cases have jumped for other groups. In particular, Latino gay and bisexual men saw new cases climb from 6,400 per year in 2010 to 8,300 in 2016. The incidence rate has stayed high and stable among African American gay and bisexual men, with 9,800 new cases reported in 2010; the same number was seen in 2016.

Among gay and bisexual men overall, the rate has also stayed stable, with about 26,000 new HIV infections reported at the beginning and end of the studied period. White heterosexual women saw about 1,000 new cases per year in 2010 and in 2016.

Some groups saw declines in new cases: African American and Latina heterosexual women each saw a falling incidence of new HIV cases. For the former group, new cases fell from 4,700 to 4,000, while the latter group of women saw new cases drop from 1,200 to 980 per year from 2010 to 2016.

Within these broad groups, HIV incidence also rose among some age groups and fell among others. Decreases were seen for younger African American gay and bisexual men (those aged 13-24 years), but rates increased by about two-thirds for men in this group aged 25-34 years. A similar increase was seen for Latino men in the 25-34 years age group, a change which drove the overall 30% increase in new infections for Latino gay and bisexual men.

White gay and bisexual men saw across-the-board decreases in new infections, though the overall decrease was less than 20%.

For heterosexual individuals as a group, new infections dropped by about 17%, from 10,900 to 9,100 annually. This change was driven mostly by decreases in women identifying as heterosexual.

“After a decades-long struggle, the path to eliminate America’s HIV epidemic is clear,” said Eugene McCray, MD, director of CDC’s Division of HIV/AIDS Prevention, in the press release. “Expanding efforts across the country will close gaps, overcome threats, and turn around troublesome trends.”

The press release cited local work in Washington and New York as evidence that targeted resources can make a difference in reducing new HIV cases. In these two areas, new infections dropped by 23% and 40% respectively from 2010 to 2016.

SOURCE: Centers for Disease Control. CDC Report: www.cdc.gov/hiv/library/reports/hiv-surveillance.html.

The annual number of new HIV infections has remained stable in recent years, and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention says that’s not good – but solutions are at hand.

Though the estimated number of new HIV infections declined from just under 42,000 per year in 2010 to about 39,000 annually in 2013, that figure was essentially unchanged by 2016, with 38,700 new HIV infections seen that year.

“CDC estimates that the decline in HIV infections has plateaued because effective HIV prevention and treatment are not adequately reaching those who could most benefit from them. These gaps remain particularly troublesome in rural areas and in the South and among disproportionately affected populations like African Americans and Latinos,” said the CDC in a press release accompanying the report.

The report comes soon after President Trump’s State of the Union address, which announced a new multiagency initiative to eliminate the HIV epidemic in the United States, with the goal of reducing new HIV infections by 90% over the next 10 years. The multipronged initiative will implement geographically targeted HIV elimination teams in areas with high HIV prevalence, pulling together federal agencies, local and state governments, and community-level resources.

The initiative, called “Ending the Epidemic: A Plan for America” will combine an intensified approach to early diagnosis and treatment with efforts to boost uptake of pre-exposure prophylaxis for individuals at high risk for HIV infection.

The new CDC report used CD4 counts reported to the National HIV Surveillance System at the time of diagnosis to identify new (incident) cases and to track prevalence. Much of the report is devoted to finely detailed reporting of HIV incidence across sex, age, race/ethnicity, and transmission mode.

Though some groups, such as people who inject drugs, have seen a decrease of about 30% in the annual rate of new HIV cases, new cases have jumped for other groups. In particular, Latino gay and bisexual men saw new cases climb from 6,400 per year in 2010 to 8,300 in 2016. The incidence rate has stayed high and stable among African American gay and bisexual men, with 9,800 new cases reported in 2010; the same number was seen in 2016.

Among gay and bisexual men overall, the rate has also stayed stable, with about 26,000 new HIV infections reported at the beginning and end of the studied period. White heterosexual women saw about 1,000 new cases per year in 2010 and in 2016.

Some groups saw declines in new cases: African American and Latina heterosexual women each saw a falling incidence of new HIV cases. For the former group, new cases fell from 4,700 to 4,000, while the latter group of women saw new cases drop from 1,200 to 980 per year from 2010 to 2016.

Within these broad groups, HIV incidence also rose among some age groups and fell among others. Decreases were seen for younger African American gay and bisexual men (those aged 13-24 years), but rates increased by about two-thirds for men in this group aged 25-34 years. A similar increase was seen for Latino men in the 25-34 years age group, a change which drove the overall 30% increase in new infections for Latino gay and bisexual men.