User login

Should group directors continue clinical practice?

PRO

Clinical practice is beneficial to patients, the group, and your career

Finding a balance between clinical care and leadership duties truly is a challenge for hospitalist directors. Changes in the landscape of inpatient care delivery, rapid growth of HM groups, and expansion of hospitalist roles have resulted in a substantial increase in a director’s responsibilities. Today’s hospitalist leader squarely faces the dilemma of continuing clinical practice and performing administrative efforts while demonstrating competence in each. To be effective, this is precisely what physician leaders must strive to do.

Maintaining clinical practice alongside directorship duties conveys advantages in critical leadership areas. You must consider the benefits to your patient, your career, and the hospitalist group.

The Patient, Director, Group

Physician leaders offer clinical experience combined with a unique perspective on systems of care, or “the big picture.”

Likewise, caring for patients provides the opportunity to interact with and listen to the customer, which is necessary for important outcomes, such as patient satisfaction. It reminds us that we are here to care for and about patients, keeping our efforts patient-centered.

Direct patient care refocuses directors on the fundamental reason they are in leadership. It offers intrinsic professional rewards and intellectual satisfaction that will sustain and strengthen the leadership role. The effective leader strategically finds balance by delegating, prioritizing, and focusing on time management.

Continuing your clinical practice affords physician leaders leverage with their constituents—the hospitalists. Working in the trenches, especially during critical times, yields legitimacy and credibility. It also allows the leader to identify with and respond to concerns raised by members. This can connect the leader to the group, avoiding the “suit vs. white coat” dynamic. The same principle extends to other stakeholders who are part of the care team, such as nurses and referring physicians.

Other Factors

Maintaining clinical aptitude ensures that leaders stay apprised of current practices, and are aware of the latest techniques, data, and evidence. This is critical for ensuring group performance in quality initiatives, and for setting standards of clinical excellence in the group practice.

In academic centers, ward teaching allows leaders to train future physicians, pass on knowledge, and gain an understanding of the next generation and its priorities, thus keeping an eye on the future and having a clear vision.

Perhaps the most important benefit direct patient care provides in leadership is the ability to accomplish the group’s mission. A firsthand experience brings understanding of issues around workflow, efficiency, and career satisfaction. It allows leaders to audit best practices. It inspires innovative ideas for healthcare delivery and processing improvement changes.

The model of successful physician leadership is based on clinical excellence. The construct of a separation between clinical and administrative roles is a false dichotomy; the two are interdependent. HM directors have a duty to perform both, as it is the combination that makes leaders successful. TH

Dr. Wright is associate clinical professor and chief of the division of hospital medicine at the University of Wisconsin School of Medicine and Public Health in Madison.

CON

Physician leaders should relinquish clinical practice, focus on leading

I believe the vast majority of hospitalists agree with the “pro” side of this debate, but I also believe that this kind of knee-jerk reaction reflects the core deficiency that plagues physicians’ thinking regarding leadership.

The way medicine is being practiced and delivered in the hospital setting is rapidly changing. In fact, our specialty is based on this premise. Yet hospitalists still have a stone-age mentality when it comes to physician leaders. The concept of leadership, in most cases, is an afterthought.

Our Role as Leaders

The HM leader is expected to act as a caretaker: set the schedule, organize and implement QI programs, and represent the hospitalists to administration. Most HM directors are accidental leaders who sheepishly step into a position when the opportunity presents itself. This usually happens as programs grow. Few industries would accept this business model. Leadership should be considered critical and given its due respect in terms of resources, training, and experience. Rarely are supervisory positions rewarded to accidental, part-time volunteers. Leaders are chosen, groomed, and given the sufficient time and resources to carry out their mandate.

When HM programs become dysfunctional, hospitalists are quick to blame the administration—some refer to it as the “evil empire” or “the dark side.” But interesting research by Gallup Inc. has shown that the majority of employees who leave their jobs actually are leaving their manager.1

Wants vs. Needs

Leaders face dilemmas every work day. For instance, leaders need to communicate the administration’s goals and weave them into HM department systems and policies. Conversely, HM leaders have to negotiate with administration to secure the resources they need to execute those goals. Technologies are mere facilitators; people actually produce results. Yet many administrators and HM leaders are fixated on the latest software without giving much thought about how staff will implement the changes.

HM leaders need time and resources to be effective. As hospitalists, we’ve been bombarded by the evidence-based medicine mantra. But most hospitalists have never heard of, or they laugh at, evidence-based techniques that were first documented in the 1970s.2 Data is available regarding management skills that can be used to effect positive organization behavior.

We also need to be authentic leaders to combat internal disruptions from medical staff. Gallup Management research has shown that 42% of physicians on medical staffs are actively disengaged.3 Physicians not only are distant, they also actively sabotage and poison new efforts introduced by administration or physician leaders.

The hospitalist leader should only perform clinical responsibilities if they are absolutely necessary. The HM director should be given all the time, resources, due respect, and training to be a dynamic leader. The hospitalist movement would be better for it. TH

References

- Buckingham, M, Coffman C. First, Break All the Rules: How Managers Trump Companies. 1999. New York City: Simon & Schuster.

- Luthans F. Organizational Behavior. 1973. New York City: McGraw-Hill.

- Paller D. What the doctor ordered. Gallup Management Web site. Available at: http://gmj.gallup.com/content/18361/What-Doctor-Ordered.aspx. Accessed Nov. 9, 2009.

Dr. Yu is medical director of hospitalist services at Decatur (Ill.) Memorial Hospital.

PRO

Clinical practice is beneficial to patients, the group, and your career

Finding a balance between clinical care and leadership duties truly is a challenge for hospitalist directors. Changes in the landscape of inpatient care delivery, rapid growth of HM groups, and expansion of hospitalist roles have resulted in a substantial increase in a director’s responsibilities. Today’s hospitalist leader squarely faces the dilemma of continuing clinical practice and performing administrative efforts while demonstrating competence in each. To be effective, this is precisely what physician leaders must strive to do.

Maintaining clinical practice alongside directorship duties conveys advantages in critical leadership areas. You must consider the benefits to your patient, your career, and the hospitalist group.

The Patient, Director, Group

Physician leaders offer clinical experience combined with a unique perspective on systems of care, or “the big picture.”

Likewise, caring for patients provides the opportunity to interact with and listen to the customer, which is necessary for important outcomes, such as patient satisfaction. It reminds us that we are here to care for and about patients, keeping our efforts patient-centered.

Direct patient care refocuses directors on the fundamental reason they are in leadership. It offers intrinsic professional rewards and intellectual satisfaction that will sustain and strengthen the leadership role. The effective leader strategically finds balance by delegating, prioritizing, and focusing on time management.

Continuing your clinical practice affords physician leaders leverage with their constituents—the hospitalists. Working in the trenches, especially during critical times, yields legitimacy and credibility. It also allows the leader to identify with and respond to concerns raised by members. This can connect the leader to the group, avoiding the “suit vs. white coat” dynamic. The same principle extends to other stakeholders who are part of the care team, such as nurses and referring physicians.

Other Factors

Maintaining clinical aptitude ensures that leaders stay apprised of current practices, and are aware of the latest techniques, data, and evidence. This is critical for ensuring group performance in quality initiatives, and for setting standards of clinical excellence in the group practice.

In academic centers, ward teaching allows leaders to train future physicians, pass on knowledge, and gain an understanding of the next generation and its priorities, thus keeping an eye on the future and having a clear vision.

Perhaps the most important benefit direct patient care provides in leadership is the ability to accomplish the group’s mission. A firsthand experience brings understanding of issues around workflow, efficiency, and career satisfaction. It allows leaders to audit best practices. It inspires innovative ideas for healthcare delivery and processing improvement changes.

The model of successful physician leadership is based on clinical excellence. The construct of a separation between clinical and administrative roles is a false dichotomy; the two are interdependent. HM directors have a duty to perform both, as it is the combination that makes leaders successful. TH

Dr. Wright is associate clinical professor and chief of the division of hospital medicine at the University of Wisconsin School of Medicine and Public Health in Madison.

CON

Physician leaders should relinquish clinical practice, focus on leading

I believe the vast majority of hospitalists agree with the “pro” side of this debate, but I also believe that this kind of knee-jerk reaction reflects the core deficiency that plagues physicians’ thinking regarding leadership.

The way medicine is being practiced and delivered in the hospital setting is rapidly changing. In fact, our specialty is based on this premise. Yet hospitalists still have a stone-age mentality when it comes to physician leaders. The concept of leadership, in most cases, is an afterthought.

Our Role as Leaders

The HM leader is expected to act as a caretaker: set the schedule, organize and implement QI programs, and represent the hospitalists to administration. Most HM directors are accidental leaders who sheepishly step into a position when the opportunity presents itself. This usually happens as programs grow. Few industries would accept this business model. Leadership should be considered critical and given its due respect in terms of resources, training, and experience. Rarely are supervisory positions rewarded to accidental, part-time volunteers. Leaders are chosen, groomed, and given the sufficient time and resources to carry out their mandate.

When HM programs become dysfunctional, hospitalists are quick to blame the administration—some refer to it as the “evil empire” or “the dark side.” But interesting research by Gallup Inc. has shown that the majority of employees who leave their jobs actually are leaving their manager.1

Wants vs. Needs

Leaders face dilemmas every work day. For instance, leaders need to communicate the administration’s goals and weave them into HM department systems and policies. Conversely, HM leaders have to negotiate with administration to secure the resources they need to execute those goals. Technologies are mere facilitators; people actually produce results. Yet many administrators and HM leaders are fixated on the latest software without giving much thought about how staff will implement the changes.

HM leaders need time and resources to be effective. As hospitalists, we’ve been bombarded by the evidence-based medicine mantra. But most hospitalists have never heard of, or they laugh at, evidence-based techniques that were first documented in the 1970s.2 Data is available regarding management skills that can be used to effect positive organization behavior.

We also need to be authentic leaders to combat internal disruptions from medical staff. Gallup Management research has shown that 42% of physicians on medical staffs are actively disengaged.3 Physicians not only are distant, they also actively sabotage and poison new efforts introduced by administration or physician leaders.

The hospitalist leader should only perform clinical responsibilities if they are absolutely necessary. The HM director should be given all the time, resources, due respect, and training to be a dynamic leader. The hospitalist movement would be better for it. TH

References

- Buckingham, M, Coffman C. First, Break All the Rules: How Managers Trump Companies. 1999. New York City: Simon & Schuster.

- Luthans F. Organizational Behavior. 1973. New York City: McGraw-Hill.

- Paller D. What the doctor ordered. Gallup Management Web site. Available at: http://gmj.gallup.com/content/18361/What-Doctor-Ordered.aspx. Accessed Nov. 9, 2009.

Dr. Yu is medical director of hospitalist services at Decatur (Ill.) Memorial Hospital.

PRO

Clinical practice is beneficial to patients, the group, and your career

Finding a balance between clinical care and leadership duties truly is a challenge for hospitalist directors. Changes in the landscape of inpatient care delivery, rapid growth of HM groups, and expansion of hospitalist roles have resulted in a substantial increase in a director’s responsibilities. Today’s hospitalist leader squarely faces the dilemma of continuing clinical practice and performing administrative efforts while demonstrating competence in each. To be effective, this is precisely what physician leaders must strive to do.

Maintaining clinical practice alongside directorship duties conveys advantages in critical leadership areas. You must consider the benefits to your patient, your career, and the hospitalist group.

The Patient, Director, Group

Physician leaders offer clinical experience combined with a unique perspective on systems of care, or “the big picture.”

Likewise, caring for patients provides the opportunity to interact with and listen to the customer, which is necessary for important outcomes, such as patient satisfaction. It reminds us that we are here to care for and about patients, keeping our efforts patient-centered.

Direct patient care refocuses directors on the fundamental reason they are in leadership. It offers intrinsic professional rewards and intellectual satisfaction that will sustain and strengthen the leadership role. The effective leader strategically finds balance by delegating, prioritizing, and focusing on time management.

Continuing your clinical practice affords physician leaders leverage with their constituents—the hospitalists. Working in the trenches, especially during critical times, yields legitimacy and credibility. It also allows the leader to identify with and respond to concerns raised by members. This can connect the leader to the group, avoiding the “suit vs. white coat” dynamic. The same principle extends to other stakeholders who are part of the care team, such as nurses and referring physicians.

Other Factors

Maintaining clinical aptitude ensures that leaders stay apprised of current practices, and are aware of the latest techniques, data, and evidence. This is critical for ensuring group performance in quality initiatives, and for setting standards of clinical excellence in the group practice.

In academic centers, ward teaching allows leaders to train future physicians, pass on knowledge, and gain an understanding of the next generation and its priorities, thus keeping an eye on the future and having a clear vision.

Perhaps the most important benefit direct patient care provides in leadership is the ability to accomplish the group’s mission. A firsthand experience brings understanding of issues around workflow, efficiency, and career satisfaction. It allows leaders to audit best practices. It inspires innovative ideas for healthcare delivery and processing improvement changes.

The model of successful physician leadership is based on clinical excellence. The construct of a separation between clinical and administrative roles is a false dichotomy; the two are interdependent. HM directors have a duty to perform both, as it is the combination that makes leaders successful. TH

Dr. Wright is associate clinical professor and chief of the division of hospital medicine at the University of Wisconsin School of Medicine and Public Health in Madison.

CON

Physician leaders should relinquish clinical practice, focus on leading

I believe the vast majority of hospitalists agree with the “pro” side of this debate, but I also believe that this kind of knee-jerk reaction reflects the core deficiency that plagues physicians’ thinking regarding leadership.

The way medicine is being practiced and delivered in the hospital setting is rapidly changing. In fact, our specialty is based on this premise. Yet hospitalists still have a stone-age mentality when it comes to physician leaders. The concept of leadership, in most cases, is an afterthought.

Our Role as Leaders

The HM leader is expected to act as a caretaker: set the schedule, organize and implement QI programs, and represent the hospitalists to administration. Most HM directors are accidental leaders who sheepishly step into a position when the opportunity presents itself. This usually happens as programs grow. Few industries would accept this business model. Leadership should be considered critical and given its due respect in terms of resources, training, and experience. Rarely are supervisory positions rewarded to accidental, part-time volunteers. Leaders are chosen, groomed, and given the sufficient time and resources to carry out their mandate.

When HM programs become dysfunctional, hospitalists are quick to blame the administration—some refer to it as the “evil empire” or “the dark side.” But interesting research by Gallup Inc. has shown that the majority of employees who leave their jobs actually are leaving their manager.1

Wants vs. Needs

Leaders face dilemmas every work day. For instance, leaders need to communicate the administration’s goals and weave them into HM department systems and policies. Conversely, HM leaders have to negotiate with administration to secure the resources they need to execute those goals. Technologies are mere facilitators; people actually produce results. Yet many administrators and HM leaders are fixated on the latest software without giving much thought about how staff will implement the changes.

HM leaders need time and resources to be effective. As hospitalists, we’ve been bombarded by the evidence-based medicine mantra. But most hospitalists have never heard of, or they laugh at, evidence-based techniques that were first documented in the 1970s.2 Data is available regarding management skills that can be used to effect positive organization behavior.

We also need to be authentic leaders to combat internal disruptions from medical staff. Gallup Management research has shown that 42% of physicians on medical staffs are actively disengaged.3 Physicians not only are distant, they also actively sabotage and poison new efforts introduced by administration or physician leaders.

The hospitalist leader should only perform clinical responsibilities if they are absolutely necessary. The HM director should be given all the time, resources, due respect, and training to be a dynamic leader. The hospitalist movement would be better for it. TH

References

- Buckingham, M, Coffman C. First, Break All the Rules: How Managers Trump Companies. 1999. New York City: Simon & Schuster.

- Luthans F. Organizational Behavior. 1973. New York City: McGraw-Hill.

- Paller D. What the doctor ordered. Gallup Management Web site. Available at: http://gmj.gallup.com/content/18361/What-Doctor-Ordered.aspx. Accessed Nov. 9, 2009.

Dr. Yu is medical director of hospitalist services at Decatur (Ill.) Memorial Hospital.

When Is GI Bleeding Prophylaxis Indicated in Hospitalized Patients?

Case

A 69-year-old man with Type 2 diabetes mellitus and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease is admitted to the ICU with respiratory compromise related to community-acquired pneumonia (CAP), accompanied by delirium, hyperglycemia, and hypovolemia. He responds well to supportive, noninvasive ventilatory therapy, but develops positive stool occult blood testing during the second day in the ICU. Upon clinical improvement, you transfer him to the general medical floor. What is the best strategy for preventing clinically significant gastrointestinal (GI) bleeding during his hospitalization?

Background

Stress-related mucosal disease (SRMD) refers to superficial erosions or focal ulceration of the proximal gastrointestinal mucosa resulting from physiologic demand in acute illness. Multiple factors contribute to its development, including disruption of the protective mucosal barrier, splanchnic vasculature hypoperfusion, and release of inflammatory mediators.1,2 Increasing severity and number of lesions are associated with the propensity for stress-related mucosal bleeding (SRMB). Based on severity, GI hemorrhage can be defined as occult (detected on chemical testing), overt (grossly evident), or clinically important (overt with compromised hemodynamics or requiring transfusion).3

The majority of clinically significant GI bleeding events occur in critically ill patients. Although more than 75% of patients have endoscopic evidence of SRMD within 24 hours of ICU admission, lesions often resolve spontaneously as patients stabilize, and the average frequency of significant bleeding is only 6%. However, when present, SRMB in ICU patients increases the length of hospitalization, cost, and mortality rates.1,3 By contrast, significant GI bleeding occurs in less than 1% of inpatients without critical illness.4

While preventing clinically important bleeding in hospitalized patients is a crucial objective, current practice reflects significant stress ulcer phophylaxis (SUP) overutilization, with substantial economic impact and potential for harm. One in three patients takes antisecretory therapy (AST) upon admission.5 Additionally, SUP is prescribed in 32% to 54% of general medical inpatients, despite the low risk for SRMB. Importantly, these prophylactic agents are continued on discharge in more than half of these patients.6-9 Clinician prescribing practices potentially can set an unfounded standard of care for obligatory prophylaxis among inpatients.

Data for Clinical Decision-Making

Several studies report the risks for gastrointestinal hemorrhage related to acute illness. In a prospective study of 2,252 ICU patients, two independent predictors of clinically important, new-onset SRMB were identified: mechanical ventilation for more than 48 hours and coagulopathy (see Table 1). Of these risk factors, respiratory failure was present in virtually all patients with GI hemorrhage; only one patient had coagulopathy alone. Mechanical ventilation or coagulopathy was associated with a 4% risk of clinically important GI bleeding, whereas patients with neither symptom had a 0.1% risk.

Though GI bleeding was uncommon, mortality associated with bleeding was 49%, compared with 9% in the nonbleeding group. In the absence of one of these two risk factors, 900 ICU patients would need to be treated to prevent one clinically important GI bleeding event.3 Other studies identify an increased risk of GI bleeding in subsets of patients with trauma, thermal injury, and organ transplantation. Additional possible risk factors might include septic shock, glucocorticoid or NSAID use, renal or hepatic failure, and prior GI bleeding or ulcer.10 The likelihood of GI bleeding increases proportionate to the number of risk factors present.

Limited data for non-ICU patients demonstrate an increased bleeding risk in the presence of ischemic heart disease, chronic renal failure, mechanical ventilation, or prior ICU stay.11 One study of 17,707 general medical patients found a low overall incidence (0.4%) of overt or clinically important GI bleeding, mainly in patients treated with anticoagulants without a mortality difference related to bleeding events.4

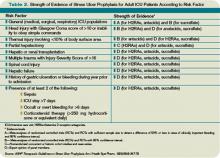

The 1999 American Society of Health System Pharmacists (ASHP) Therapeutic Guidelines on Stress Ulcer Prophylaxis reviewed extensive data by level of evidence to identify clinical indicators of patients at higher risk (see Table 2, p. 31).10 The bottom line is that stress-related bleeding depends on the type and severity of illness. Independent risk factors for critically ill patients include mechanical ventilation or coagulopathy. Stable general medical inpatients are at very low risk of clinically significant GI bleeding.

Clinical predictors help define patients at the greatest risk of SRMB. However, to be meaningful, SUP must improve clinical outcomes. Despite extensive studies on the efficacy of pharmacologic agents in the prevention of significant bleeding, several trials do not show a benefit of SUP over placebo, even in patients with major risk factors.4,12,13 Other independent studies and meta-analyses demonstrate that H2-receptor antagonists (H2RAs) prevent ICU bleeding, reducing events by approximately 50%.10 Of all the available prophylactic agents, H2RAs are FDA-approved for this use, proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) are likely as effective, and both are well-tolerated. However, data suggest that the use of AST is associated with C. difficile-associated disease, hip fracture, and pneumonia.

Outside of the ICU, there is no difference in de novo GI bleeding among general medical patients prescribed SUP. The ASHP guidelines thus conclude there is no indication for SUP in stable, general medical inpatients.10

Prevention Strategies

A subset of seriously ill patients has an increased risk for significant SRMB, but ideal prevention is not well-defined. As noted in the ASHP guidelines, “prophylaxis does not necessarily prevent bleeding in patients with documented risk factors, and the efficacy of prophylaxis varies in different patient populations.”

Given the effect of SRMB, it is reasonable to provide preventive agents to subgroups of critically ill patients with significant risk factors of mechanical ventilation for more than 48 hours and underlying coagulopathy. Studies report that judicious SUP prescription when these risks are present reduces cost without increasing morbidity or mortality in the ICU.14

Back to the Case

Our case addresses a patient in both an ICU and general medical setting. Based on his lack of risk factors for significant GI bleeding, SUP was not indicated. In this case, the patient improved. Had he developed ventilatory failure requiring intubation, the risk of clinically important GI bleeding would have approached 4%, and H2RA prophylaxis would have been recommended. Although the optimal length of prophylaxis is unknown, SUP likely can be discontinued on transfer out of the ICU, as clinical stability is associated with a substantially lower risk of clinically important bleeding.

Bottom Line

Literature supports the limited use of SUP in hospitalized medical inpatients. SUP can be reserved for critically-ill patients with major risk factors, including prolonged mechanical ventilation or coagulopathy. TH

Dr. Wright is associate professor and head of the section of hospital medicine of the Department of Medicine at the University of Wisconsin School of Medicine and Public Health.

References

1. Stollman N, Metz D. Pathophysiology and prophylaxis of stress ulcer in intensive care unit patients. J Crit Care. 2005;20:35-45.

2. Fennerty M. Pathophysiology of the upper gastrointestinal tract in the critically ill patient: rationale for the therapeutic benefits of acid suppression. Crit Care Med. 2002;30(6 Suppl):S351-S355.

3. Cook D, Fuller H, Guyatt G, et al. Risk factors for gastrointestinal bleeding in critically ill patients. New Engl J Med. 1994;330:377-381.

4. Qadeer M, Richter J, Brotman D. Hospital-acquired gastrointestinal bleeding outside the critical care unit: risk factors, role of acid suppression, and endoscopy findings. J Hosp Med. 2006;1:13-20.

5. Heidelbaugh J, Inadomi J. Magnitude and economic impact of inappropriate use of stress ulcer prophylaxis in non-ICU hospitalized patients. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101:2200-2205.

6. Nardino R, Vender R, Herbert P. Overuse of acid-suppressive therapy in hospitalized patients. Am J Gastroenterol. 2000;95:3118-3122.

7. Pham C, Regal R, Bostwick T, Knauf K. Acid suppressive therapy use on an inpatient internal medicine service. Ann Pharmacother. 2006;40:1261-1266.

8. Hwang K, Kolarov S, Cheng L, Griffith R. Stress ulcer prophylaxis for non-critically ill patients on a teaching service. J Eval Clin Pract. 2007;13:716-721.

9. Wohlt P, Hansen L, Fish J. Inappropriate continuation of stress ulcer prophylactic therapy after discharge. Ann Pharmachother. 2007;41:1611-1616.

10. ASHP therapeutic guidelines on stress ulcer prophylaxis. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 1999;56:347-379.

11. Janicki T, Stewart S. Stress-ulcer prophylaxis for general medical patients: a review of the evidence. J Hosp Med. 2007;2:86-92.

12. Faisy C, Guerot E, Diehl J, Iftimovici E, Fagon J. Clinically significant gastrointestinal bleeding in critically ill patients with and without stress-ulcer prophylaxis. Intensive Care Med. 2003;29:1306-1313.

13. Kantorova I, Svoboda P, Scheer P, et al. Stress ulcer prophylaxis in critically ill patients: a randomized controlled trial. Hepatogastroenterology. 2004;51:757-761.

14. Coursol C, Sanzari S. Impact of stress ulcer prophylaxis algorithm study. Ann Pharmacother. 2005;39:810-816.

Case

A 69-year-old man with Type 2 diabetes mellitus and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease is admitted to the ICU with respiratory compromise related to community-acquired pneumonia (CAP), accompanied by delirium, hyperglycemia, and hypovolemia. He responds well to supportive, noninvasive ventilatory therapy, but develops positive stool occult blood testing during the second day in the ICU. Upon clinical improvement, you transfer him to the general medical floor. What is the best strategy for preventing clinically significant gastrointestinal (GI) bleeding during his hospitalization?

Background

Stress-related mucosal disease (SRMD) refers to superficial erosions or focal ulceration of the proximal gastrointestinal mucosa resulting from physiologic demand in acute illness. Multiple factors contribute to its development, including disruption of the protective mucosal barrier, splanchnic vasculature hypoperfusion, and release of inflammatory mediators.1,2 Increasing severity and number of lesions are associated with the propensity for stress-related mucosal bleeding (SRMB). Based on severity, GI hemorrhage can be defined as occult (detected on chemical testing), overt (grossly evident), or clinically important (overt with compromised hemodynamics or requiring transfusion).3

The majority of clinically significant GI bleeding events occur in critically ill patients. Although more than 75% of patients have endoscopic evidence of SRMD within 24 hours of ICU admission, lesions often resolve spontaneously as patients stabilize, and the average frequency of significant bleeding is only 6%. However, when present, SRMB in ICU patients increases the length of hospitalization, cost, and mortality rates.1,3 By contrast, significant GI bleeding occurs in less than 1% of inpatients without critical illness.4

While preventing clinically important bleeding in hospitalized patients is a crucial objective, current practice reflects significant stress ulcer phophylaxis (SUP) overutilization, with substantial economic impact and potential for harm. One in three patients takes antisecretory therapy (AST) upon admission.5 Additionally, SUP is prescribed in 32% to 54% of general medical inpatients, despite the low risk for SRMB. Importantly, these prophylactic agents are continued on discharge in more than half of these patients.6-9 Clinician prescribing practices potentially can set an unfounded standard of care for obligatory prophylaxis among inpatients.

Data for Clinical Decision-Making

Several studies report the risks for gastrointestinal hemorrhage related to acute illness. In a prospective study of 2,252 ICU patients, two independent predictors of clinically important, new-onset SRMB were identified: mechanical ventilation for more than 48 hours and coagulopathy (see Table 1). Of these risk factors, respiratory failure was present in virtually all patients with GI hemorrhage; only one patient had coagulopathy alone. Mechanical ventilation or coagulopathy was associated with a 4% risk of clinically important GI bleeding, whereas patients with neither symptom had a 0.1% risk.

Though GI bleeding was uncommon, mortality associated with bleeding was 49%, compared with 9% in the nonbleeding group. In the absence of one of these two risk factors, 900 ICU patients would need to be treated to prevent one clinically important GI bleeding event.3 Other studies identify an increased risk of GI bleeding in subsets of patients with trauma, thermal injury, and organ transplantation. Additional possible risk factors might include septic shock, glucocorticoid or NSAID use, renal or hepatic failure, and prior GI bleeding or ulcer.10 The likelihood of GI bleeding increases proportionate to the number of risk factors present.

Limited data for non-ICU patients demonstrate an increased bleeding risk in the presence of ischemic heart disease, chronic renal failure, mechanical ventilation, or prior ICU stay.11 One study of 17,707 general medical patients found a low overall incidence (0.4%) of overt or clinically important GI bleeding, mainly in patients treated with anticoagulants without a mortality difference related to bleeding events.4

The 1999 American Society of Health System Pharmacists (ASHP) Therapeutic Guidelines on Stress Ulcer Prophylaxis reviewed extensive data by level of evidence to identify clinical indicators of patients at higher risk (see Table 2, p. 31).10 The bottom line is that stress-related bleeding depends on the type and severity of illness. Independent risk factors for critically ill patients include mechanical ventilation or coagulopathy. Stable general medical inpatients are at very low risk of clinically significant GI bleeding.

Clinical predictors help define patients at the greatest risk of SRMB. However, to be meaningful, SUP must improve clinical outcomes. Despite extensive studies on the efficacy of pharmacologic agents in the prevention of significant bleeding, several trials do not show a benefit of SUP over placebo, even in patients with major risk factors.4,12,13 Other independent studies and meta-analyses demonstrate that H2-receptor antagonists (H2RAs) prevent ICU bleeding, reducing events by approximately 50%.10 Of all the available prophylactic agents, H2RAs are FDA-approved for this use, proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) are likely as effective, and both are well-tolerated. However, data suggest that the use of AST is associated with C. difficile-associated disease, hip fracture, and pneumonia.

Outside of the ICU, there is no difference in de novo GI bleeding among general medical patients prescribed SUP. The ASHP guidelines thus conclude there is no indication for SUP in stable, general medical inpatients.10

Prevention Strategies

A subset of seriously ill patients has an increased risk for significant SRMB, but ideal prevention is not well-defined. As noted in the ASHP guidelines, “prophylaxis does not necessarily prevent bleeding in patients with documented risk factors, and the efficacy of prophylaxis varies in different patient populations.”

Given the effect of SRMB, it is reasonable to provide preventive agents to subgroups of critically ill patients with significant risk factors of mechanical ventilation for more than 48 hours and underlying coagulopathy. Studies report that judicious SUP prescription when these risks are present reduces cost without increasing morbidity or mortality in the ICU.14

Back to the Case

Our case addresses a patient in both an ICU and general medical setting. Based on his lack of risk factors for significant GI bleeding, SUP was not indicated. In this case, the patient improved. Had he developed ventilatory failure requiring intubation, the risk of clinically important GI bleeding would have approached 4%, and H2RA prophylaxis would have been recommended. Although the optimal length of prophylaxis is unknown, SUP likely can be discontinued on transfer out of the ICU, as clinical stability is associated with a substantially lower risk of clinically important bleeding.

Bottom Line

Literature supports the limited use of SUP in hospitalized medical inpatients. SUP can be reserved for critically-ill patients with major risk factors, including prolonged mechanical ventilation or coagulopathy. TH

Dr. Wright is associate professor and head of the section of hospital medicine of the Department of Medicine at the University of Wisconsin School of Medicine and Public Health.

References

1. Stollman N, Metz D. Pathophysiology and prophylaxis of stress ulcer in intensive care unit patients. J Crit Care. 2005;20:35-45.

2. Fennerty M. Pathophysiology of the upper gastrointestinal tract in the critically ill patient: rationale for the therapeutic benefits of acid suppression. Crit Care Med. 2002;30(6 Suppl):S351-S355.

3. Cook D, Fuller H, Guyatt G, et al. Risk factors for gastrointestinal bleeding in critically ill patients. New Engl J Med. 1994;330:377-381.

4. Qadeer M, Richter J, Brotman D. Hospital-acquired gastrointestinal bleeding outside the critical care unit: risk factors, role of acid suppression, and endoscopy findings. J Hosp Med. 2006;1:13-20.

5. Heidelbaugh J, Inadomi J. Magnitude and economic impact of inappropriate use of stress ulcer prophylaxis in non-ICU hospitalized patients. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101:2200-2205.

6. Nardino R, Vender R, Herbert P. Overuse of acid-suppressive therapy in hospitalized patients. Am J Gastroenterol. 2000;95:3118-3122.

7. Pham C, Regal R, Bostwick T, Knauf K. Acid suppressive therapy use on an inpatient internal medicine service. Ann Pharmacother. 2006;40:1261-1266.

8. Hwang K, Kolarov S, Cheng L, Griffith R. Stress ulcer prophylaxis for non-critically ill patients on a teaching service. J Eval Clin Pract. 2007;13:716-721.

9. Wohlt P, Hansen L, Fish J. Inappropriate continuation of stress ulcer prophylactic therapy after discharge. Ann Pharmachother. 2007;41:1611-1616.

10. ASHP therapeutic guidelines on stress ulcer prophylaxis. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 1999;56:347-379.

11. Janicki T, Stewart S. Stress-ulcer prophylaxis for general medical patients: a review of the evidence. J Hosp Med. 2007;2:86-92.

12. Faisy C, Guerot E, Diehl J, Iftimovici E, Fagon J. Clinically significant gastrointestinal bleeding in critically ill patients with and without stress-ulcer prophylaxis. Intensive Care Med. 2003;29:1306-1313.

13. Kantorova I, Svoboda P, Scheer P, et al. Stress ulcer prophylaxis in critically ill patients: a randomized controlled trial. Hepatogastroenterology. 2004;51:757-761.

14. Coursol C, Sanzari S. Impact of stress ulcer prophylaxis algorithm study. Ann Pharmacother. 2005;39:810-816.

Case

A 69-year-old man with Type 2 diabetes mellitus and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease is admitted to the ICU with respiratory compromise related to community-acquired pneumonia (CAP), accompanied by delirium, hyperglycemia, and hypovolemia. He responds well to supportive, noninvasive ventilatory therapy, but develops positive stool occult blood testing during the second day in the ICU. Upon clinical improvement, you transfer him to the general medical floor. What is the best strategy for preventing clinically significant gastrointestinal (GI) bleeding during his hospitalization?

Background

Stress-related mucosal disease (SRMD) refers to superficial erosions or focal ulceration of the proximal gastrointestinal mucosa resulting from physiologic demand in acute illness. Multiple factors contribute to its development, including disruption of the protective mucosal barrier, splanchnic vasculature hypoperfusion, and release of inflammatory mediators.1,2 Increasing severity and number of lesions are associated with the propensity for stress-related mucosal bleeding (SRMB). Based on severity, GI hemorrhage can be defined as occult (detected on chemical testing), overt (grossly evident), or clinically important (overt with compromised hemodynamics or requiring transfusion).3

The majority of clinically significant GI bleeding events occur in critically ill patients. Although more than 75% of patients have endoscopic evidence of SRMD within 24 hours of ICU admission, lesions often resolve spontaneously as patients stabilize, and the average frequency of significant bleeding is only 6%. However, when present, SRMB in ICU patients increases the length of hospitalization, cost, and mortality rates.1,3 By contrast, significant GI bleeding occurs in less than 1% of inpatients without critical illness.4

While preventing clinically important bleeding in hospitalized patients is a crucial objective, current practice reflects significant stress ulcer phophylaxis (SUP) overutilization, with substantial economic impact and potential for harm. One in three patients takes antisecretory therapy (AST) upon admission.5 Additionally, SUP is prescribed in 32% to 54% of general medical inpatients, despite the low risk for SRMB. Importantly, these prophylactic agents are continued on discharge in more than half of these patients.6-9 Clinician prescribing practices potentially can set an unfounded standard of care for obligatory prophylaxis among inpatients.

Data for Clinical Decision-Making

Several studies report the risks for gastrointestinal hemorrhage related to acute illness. In a prospective study of 2,252 ICU patients, two independent predictors of clinically important, new-onset SRMB were identified: mechanical ventilation for more than 48 hours and coagulopathy (see Table 1). Of these risk factors, respiratory failure was present in virtually all patients with GI hemorrhage; only one patient had coagulopathy alone. Mechanical ventilation or coagulopathy was associated with a 4% risk of clinically important GI bleeding, whereas patients with neither symptom had a 0.1% risk.

Though GI bleeding was uncommon, mortality associated with bleeding was 49%, compared with 9% in the nonbleeding group. In the absence of one of these two risk factors, 900 ICU patients would need to be treated to prevent one clinically important GI bleeding event.3 Other studies identify an increased risk of GI bleeding in subsets of patients with trauma, thermal injury, and organ transplantation. Additional possible risk factors might include septic shock, glucocorticoid or NSAID use, renal or hepatic failure, and prior GI bleeding or ulcer.10 The likelihood of GI bleeding increases proportionate to the number of risk factors present.

Limited data for non-ICU patients demonstrate an increased bleeding risk in the presence of ischemic heart disease, chronic renal failure, mechanical ventilation, or prior ICU stay.11 One study of 17,707 general medical patients found a low overall incidence (0.4%) of overt or clinically important GI bleeding, mainly in patients treated with anticoagulants without a mortality difference related to bleeding events.4

The 1999 American Society of Health System Pharmacists (ASHP) Therapeutic Guidelines on Stress Ulcer Prophylaxis reviewed extensive data by level of evidence to identify clinical indicators of patients at higher risk (see Table 2, p. 31).10 The bottom line is that stress-related bleeding depends on the type and severity of illness. Independent risk factors for critically ill patients include mechanical ventilation or coagulopathy. Stable general medical inpatients are at very low risk of clinically significant GI bleeding.

Clinical predictors help define patients at the greatest risk of SRMB. However, to be meaningful, SUP must improve clinical outcomes. Despite extensive studies on the efficacy of pharmacologic agents in the prevention of significant bleeding, several trials do not show a benefit of SUP over placebo, even in patients with major risk factors.4,12,13 Other independent studies and meta-analyses demonstrate that H2-receptor antagonists (H2RAs) prevent ICU bleeding, reducing events by approximately 50%.10 Of all the available prophylactic agents, H2RAs are FDA-approved for this use, proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) are likely as effective, and both are well-tolerated. However, data suggest that the use of AST is associated with C. difficile-associated disease, hip fracture, and pneumonia.

Outside of the ICU, there is no difference in de novo GI bleeding among general medical patients prescribed SUP. The ASHP guidelines thus conclude there is no indication for SUP in stable, general medical inpatients.10

Prevention Strategies

A subset of seriously ill patients has an increased risk for significant SRMB, but ideal prevention is not well-defined. As noted in the ASHP guidelines, “prophylaxis does not necessarily prevent bleeding in patients with documented risk factors, and the efficacy of prophylaxis varies in different patient populations.”

Given the effect of SRMB, it is reasonable to provide preventive agents to subgroups of critically ill patients with significant risk factors of mechanical ventilation for more than 48 hours and underlying coagulopathy. Studies report that judicious SUP prescription when these risks are present reduces cost without increasing morbidity or mortality in the ICU.14

Back to the Case

Our case addresses a patient in both an ICU and general medical setting. Based on his lack of risk factors for significant GI bleeding, SUP was not indicated. In this case, the patient improved. Had he developed ventilatory failure requiring intubation, the risk of clinically important GI bleeding would have approached 4%, and H2RA prophylaxis would have been recommended. Although the optimal length of prophylaxis is unknown, SUP likely can be discontinued on transfer out of the ICU, as clinical stability is associated with a substantially lower risk of clinically important bleeding.

Bottom Line

Literature supports the limited use of SUP in hospitalized medical inpatients. SUP can be reserved for critically-ill patients with major risk factors, including prolonged mechanical ventilation or coagulopathy. TH

Dr. Wright is associate professor and head of the section of hospital medicine of the Department of Medicine at the University of Wisconsin School of Medicine and Public Health.

References

1. Stollman N, Metz D. Pathophysiology and prophylaxis of stress ulcer in intensive care unit patients. J Crit Care. 2005;20:35-45.

2. Fennerty M. Pathophysiology of the upper gastrointestinal tract in the critically ill patient: rationale for the therapeutic benefits of acid suppression. Crit Care Med. 2002;30(6 Suppl):S351-S355.

3. Cook D, Fuller H, Guyatt G, et al. Risk factors for gastrointestinal bleeding in critically ill patients. New Engl J Med. 1994;330:377-381.

4. Qadeer M, Richter J, Brotman D. Hospital-acquired gastrointestinal bleeding outside the critical care unit: risk factors, role of acid suppression, and endoscopy findings. J Hosp Med. 2006;1:13-20.

5. Heidelbaugh J, Inadomi J. Magnitude and economic impact of inappropriate use of stress ulcer prophylaxis in non-ICU hospitalized patients. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101:2200-2205.

6. Nardino R, Vender R, Herbert P. Overuse of acid-suppressive therapy in hospitalized patients. Am J Gastroenterol. 2000;95:3118-3122.

7. Pham C, Regal R, Bostwick T, Knauf K. Acid suppressive therapy use on an inpatient internal medicine service. Ann Pharmacother. 2006;40:1261-1266.

8. Hwang K, Kolarov S, Cheng L, Griffith R. Stress ulcer prophylaxis for non-critically ill patients on a teaching service. J Eval Clin Pract. 2007;13:716-721.

9. Wohlt P, Hansen L, Fish J. Inappropriate continuation of stress ulcer prophylactic therapy after discharge. Ann Pharmachother. 2007;41:1611-1616.

10. ASHP therapeutic guidelines on stress ulcer prophylaxis. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 1999;56:347-379.

11. Janicki T, Stewart S. Stress-ulcer prophylaxis for general medical patients: a review of the evidence. J Hosp Med. 2007;2:86-92.

12. Faisy C, Guerot E, Diehl J, Iftimovici E, Fagon J. Clinically significant gastrointestinal bleeding in critically ill patients with and without stress-ulcer prophylaxis. Intensive Care Med. 2003;29:1306-1313.

13. Kantorova I, Svoboda P, Scheer P, et al. Stress ulcer prophylaxis in critically ill patients: a randomized controlled trial. Hepatogastroenterology. 2004;51:757-761.

14. Coursol C, Sanzari S. Impact of stress ulcer prophylaxis algorithm study. Ann Pharmacother. 2005;39:810-816.