User login

The 15-Year Itch

A 58-year-old woman presents to dermatology with a 15-year history of an itchy rash on her left leg. A native of India, she has been in this country for more than 20 years and enjoys generally good health.

But about 15 years ago, she experienced some personal problems that caused great stress. About that same time, she developed a small rash on her left leg, which she began to scratch.

Over time, the lesion has become larger and more pruritic, prompting her to scratch and rub it more. Lately, she has started to use a hairbrush to scratch it. The itching has taken on a whole new level of intensity.

Her primary care provider referred her to a wound care clinic, where her lesion was treated with twice-weekly whirlpool therapy, followed by debridement and dressing with a zinc oxide–based paste. Although this calmed the affected site a bit, when treatment ceased, the rash flared again.

EXAMINATION

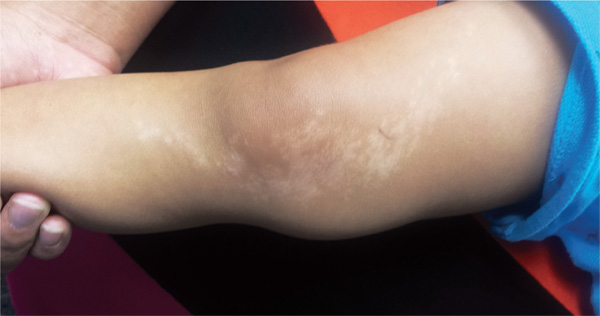

The patient has type IV skin, consistent with her origins. The lesion is an impressive, elongated oval plaque measuring about 20 x 10 cm. It covers most of the anterolateral portion of her left leg and calf.

An underlying area of brown macular hyperpigmentation extends an additional 2 to 3 cm around the periphery of the plaque. The central area is slightly edematous, quite pink, and shiny. No focal breaks in the skin are observed. There is no increased warmth or tenderness on palpation.

What is the diagnosis?

DISCUSSION

This complaint and its location are typical of an extremely common dermatologic entity called lichen simplex chronicus (LSC), formerly known as neurodermatitis. All cases of LSC start with a relatively minor, itchy trigger—such as dry skin, eczema, or a bug bite—that the patient begins to scratch or rub. This has the effect of lowering the threshold for itching by making the nerves more numerous and sensitive; the patient then reacts by scratching or rubbing even more. As a result, the epidermal layer thickens and, particularly in patients with darker skin, postinflammatory hyperpigmentation develops.

The patient will persistently respond to the itching by scratching, a reaction that becomes habitual (and in some cases, even pleasurable) and perpetuates the cycle. Although the original insult has long since resolved, the problem has taken on a life of its own.

In the 15-year history of this lesion, the patient had seen a number of clinicians but, incredibly, never a dermatology provider. She had taken several courses of oral antibiotics, used triple-antibiotic ointment, and tried tea tree oil, emu oil, antifungal creams, and most recently, topical triamcinolone cream—the last of which helped a bit.

The actual solution to the problem is utterly simple, at least in concept: Stop scratching. But there’s the rub—the impulse to scratch is quite powerful, and habits are difficult to break.

That’s where we intervened, with the use of a stronger topical steroid ointment (clobetasol 0.05% bid) on an occlusive dressing (eg, an elastic bandage wrap), which potentiates the steroid and serves as a barrier to the patient’s scratching. A soft cast (eg, an Unna boot) would accomplish the same thing but is more troublesome to apply.

Given this patient’s skin type, this area of her leg will always be discolored. She should, however, be able to control the problem from now on. If this treatment attempt were to fail, a biopsy would be needed to rule out other diagnostic possibilities, such as psoriasis or lichen planus.

TAKE-HOME LEARNING POINTS

• Lichen simplex chronicus (LSC) is quite common, especially on the anterolateral leg.

• LSC is always secondary to an original trigger, such as xerosis, eczema, bug bite, or even psoriasis.

• The chronicity of the problem, sometimes extreme (as in this case), is not only common but often diagnostic.

• Postinflammatory color changes, especially on darker skinned individuals, are common with LSC.

• Other common areas for LSC include the scrotum/vulvae and nuchal scalp.

A 58-year-old woman presents to dermatology with a 15-year history of an itchy rash on her left leg. A native of India, she has been in this country for more than 20 years and enjoys generally good health.

But about 15 years ago, she experienced some personal problems that caused great stress. About that same time, she developed a small rash on her left leg, which she began to scratch.

Over time, the lesion has become larger and more pruritic, prompting her to scratch and rub it more. Lately, she has started to use a hairbrush to scratch it. The itching has taken on a whole new level of intensity.

Her primary care provider referred her to a wound care clinic, where her lesion was treated with twice-weekly whirlpool therapy, followed by debridement and dressing with a zinc oxide–based paste. Although this calmed the affected site a bit, when treatment ceased, the rash flared again.

EXAMINATION

The patient has type IV skin, consistent with her origins. The lesion is an impressive, elongated oval plaque measuring about 20 x 10 cm. It covers most of the anterolateral portion of her left leg and calf.

An underlying area of brown macular hyperpigmentation extends an additional 2 to 3 cm around the periphery of the plaque. The central area is slightly edematous, quite pink, and shiny. No focal breaks in the skin are observed. There is no increased warmth or tenderness on palpation.

What is the diagnosis?

DISCUSSION

This complaint and its location are typical of an extremely common dermatologic entity called lichen simplex chronicus (LSC), formerly known as neurodermatitis. All cases of LSC start with a relatively minor, itchy trigger—such as dry skin, eczema, or a bug bite—that the patient begins to scratch or rub. This has the effect of lowering the threshold for itching by making the nerves more numerous and sensitive; the patient then reacts by scratching or rubbing even more. As a result, the epidermal layer thickens and, particularly in patients with darker skin, postinflammatory hyperpigmentation develops.

The patient will persistently respond to the itching by scratching, a reaction that becomes habitual (and in some cases, even pleasurable) and perpetuates the cycle. Although the original insult has long since resolved, the problem has taken on a life of its own.

In the 15-year history of this lesion, the patient had seen a number of clinicians but, incredibly, never a dermatology provider. She had taken several courses of oral antibiotics, used triple-antibiotic ointment, and tried tea tree oil, emu oil, antifungal creams, and most recently, topical triamcinolone cream—the last of which helped a bit.

The actual solution to the problem is utterly simple, at least in concept: Stop scratching. But there’s the rub—the impulse to scratch is quite powerful, and habits are difficult to break.

That’s where we intervened, with the use of a stronger topical steroid ointment (clobetasol 0.05% bid) on an occlusive dressing (eg, an elastic bandage wrap), which potentiates the steroid and serves as a barrier to the patient’s scratching. A soft cast (eg, an Unna boot) would accomplish the same thing but is more troublesome to apply.

Given this patient’s skin type, this area of her leg will always be discolored. She should, however, be able to control the problem from now on. If this treatment attempt were to fail, a biopsy would be needed to rule out other diagnostic possibilities, such as psoriasis or lichen planus.

TAKE-HOME LEARNING POINTS

• Lichen simplex chronicus (LSC) is quite common, especially on the anterolateral leg.

• LSC is always secondary to an original trigger, such as xerosis, eczema, bug bite, or even psoriasis.

• The chronicity of the problem, sometimes extreme (as in this case), is not only common but often diagnostic.

• Postinflammatory color changes, especially on darker skinned individuals, are common with LSC.

• Other common areas for LSC include the scrotum/vulvae and nuchal scalp.

A 58-year-old woman presents to dermatology with a 15-year history of an itchy rash on her left leg. A native of India, she has been in this country for more than 20 years and enjoys generally good health.

But about 15 years ago, she experienced some personal problems that caused great stress. About that same time, she developed a small rash on her left leg, which she began to scratch.

Over time, the lesion has become larger and more pruritic, prompting her to scratch and rub it more. Lately, she has started to use a hairbrush to scratch it. The itching has taken on a whole new level of intensity.

Her primary care provider referred her to a wound care clinic, where her lesion was treated with twice-weekly whirlpool therapy, followed by debridement and dressing with a zinc oxide–based paste. Although this calmed the affected site a bit, when treatment ceased, the rash flared again.

EXAMINATION

The patient has type IV skin, consistent with her origins. The lesion is an impressive, elongated oval plaque measuring about 20 x 10 cm. It covers most of the anterolateral portion of her left leg and calf.

An underlying area of brown macular hyperpigmentation extends an additional 2 to 3 cm around the periphery of the plaque. The central area is slightly edematous, quite pink, and shiny. No focal breaks in the skin are observed. There is no increased warmth or tenderness on palpation.

What is the diagnosis?

DISCUSSION

This complaint and its location are typical of an extremely common dermatologic entity called lichen simplex chronicus (LSC), formerly known as neurodermatitis. All cases of LSC start with a relatively minor, itchy trigger—such as dry skin, eczema, or a bug bite—that the patient begins to scratch or rub. This has the effect of lowering the threshold for itching by making the nerves more numerous and sensitive; the patient then reacts by scratching or rubbing even more. As a result, the epidermal layer thickens and, particularly in patients with darker skin, postinflammatory hyperpigmentation develops.

The patient will persistently respond to the itching by scratching, a reaction that becomes habitual (and in some cases, even pleasurable) and perpetuates the cycle. Although the original insult has long since resolved, the problem has taken on a life of its own.

In the 15-year history of this lesion, the patient had seen a number of clinicians but, incredibly, never a dermatology provider. She had taken several courses of oral antibiotics, used triple-antibiotic ointment, and tried tea tree oil, emu oil, antifungal creams, and most recently, topical triamcinolone cream—the last of which helped a bit.

The actual solution to the problem is utterly simple, at least in concept: Stop scratching. But there’s the rub—the impulse to scratch is quite powerful, and habits are difficult to break.

That’s where we intervened, with the use of a stronger topical steroid ointment (clobetasol 0.05% bid) on an occlusive dressing (eg, an elastic bandage wrap), which potentiates the steroid and serves as a barrier to the patient’s scratching. A soft cast (eg, an Unna boot) would accomplish the same thing but is more troublesome to apply.

Given this patient’s skin type, this area of her leg will always be discolored. She should, however, be able to control the problem from now on. If this treatment attempt were to fail, a biopsy would be needed to rule out other diagnostic possibilities, such as psoriasis or lichen planus.

TAKE-HOME LEARNING POINTS

• Lichen simplex chronicus (LSC) is quite common, especially on the anterolateral leg.

• LSC is always secondary to an original trigger, such as xerosis, eczema, bug bite, or even psoriasis.

• The chronicity of the problem, sometimes extreme (as in this case), is not only common but often diagnostic.

• Postinflammatory color changes, especially on darker skinned individuals, are common with LSC.

• Other common areas for LSC include the scrotum/vulvae and nuchal scalp.

Scalp Mass Is Painful and Oozes Pus

ANSWER

The correct answer is oral terbinafine or griseofulvin, plus a two-week taper of prednisone (choice “d”); further discussion follows. Most authorities recommend the use of oral steroids with terbinafine (choice “a”) or griseofulvin (choice “b”), to dampen the acute inflammatory reaction to the fungal antigen. Some sources advise the use of itraconazole (choice “c”) but not as a single agent.

DISCUSSION

This case is a classic representation of kerion, a type of tinea capitis. This distinctive presentation results from not only active localized fungal infection with one of the dermatophytes, but also an allergic response to the fungal antigen. (This antigen can also trigger a widespread eczematous rash called an id reaction.) The resulting boggy, tender mass often oozes pus and usually provokes significant localized adenopathy.

A more common type of tinea capitis is uncomplicated dermatophytic infection of the scalp, presenting as mild localized scaling and modest hair loss, with no edema or redness to speak of. Kerion, by contrast, is far more acute and involves an impressive amount of localized redness and edema, along with modest hair loss, purulence, bloody drainage, and marked tenderness. Untreated, kerion can result in permanent scarring alopecia.

Several different dermatophytes have been isolated from kerions, including Trichophyton tonsurans, T violaceum, and various members of the Microsporum family. These zoophilic or geophilic organisms affect children far more than adults. Distinguishing the causative type is significant, because different drugs are required to effectively treat each. This is why a fungal culture is done at the outset.

When the diagnosis is in doubt, a punch biopsy may be necessary, with the sample divided for processing of default H&E stains and for fungal culture. Other information can be obtained by plucking a few hairs from the mass and examining them under 10x power to see if fungal hyphae are confined to the insides of the hair shafts (endothrix) or the outside of the shafts (ectothrix).

This is one situation in which KOH is not helpful for diagnosis: The organisms are too deep to obtain with a superficial scrape.

A number of scalp conditions can mimic a kerion, including lichen planopilaris and folliculitis decalvans. Several years ago, I had a patient who presented with a similar lesion that turned out to be squamous cell carcinoma—which eventually metastasized and led to his death.

TREATMENT

Treatment of more severe types of tinea capitis can be trying, even when the diagnosis is nailed down. The challenge becomes treating the problem long and strong enough to produce a cure.

In this case, I started the patient (who, at age 8, weighed 110 pounds) on a month-long course of terbinafine (250 mg/d) with a two-week taper of prednisone (40 mg). The expectation was that this would rapidly diminish the edema and pain while we waited for the culture results.

If the results showed the expected T tonsurans, treatment would continue as planned. If the cause turned out to be one of the Microsporum species, a switch to griseofulvin, at relatively high doses, would be considered.

ANSWER

The correct answer is oral terbinafine or griseofulvin, plus a two-week taper of prednisone (choice “d”); further discussion follows. Most authorities recommend the use of oral steroids with terbinafine (choice “a”) or griseofulvin (choice “b”), to dampen the acute inflammatory reaction to the fungal antigen. Some sources advise the use of itraconazole (choice “c”) but not as a single agent.

DISCUSSION

This case is a classic representation of kerion, a type of tinea capitis. This distinctive presentation results from not only active localized fungal infection with one of the dermatophytes, but also an allergic response to the fungal antigen. (This antigen can also trigger a widespread eczematous rash called an id reaction.) The resulting boggy, tender mass often oozes pus and usually provokes significant localized adenopathy.

A more common type of tinea capitis is uncomplicated dermatophytic infection of the scalp, presenting as mild localized scaling and modest hair loss, with no edema or redness to speak of. Kerion, by contrast, is far more acute and involves an impressive amount of localized redness and edema, along with modest hair loss, purulence, bloody drainage, and marked tenderness. Untreated, kerion can result in permanent scarring alopecia.

Several different dermatophytes have been isolated from kerions, including Trichophyton tonsurans, T violaceum, and various members of the Microsporum family. These zoophilic or geophilic organisms affect children far more than adults. Distinguishing the causative type is significant, because different drugs are required to effectively treat each. This is why a fungal culture is done at the outset.

When the diagnosis is in doubt, a punch biopsy may be necessary, with the sample divided for processing of default H&E stains and for fungal culture. Other information can be obtained by plucking a few hairs from the mass and examining them under 10x power to see if fungal hyphae are confined to the insides of the hair shafts (endothrix) or the outside of the shafts (ectothrix).

This is one situation in which KOH is not helpful for diagnosis: The organisms are too deep to obtain with a superficial scrape.

A number of scalp conditions can mimic a kerion, including lichen planopilaris and folliculitis decalvans. Several years ago, I had a patient who presented with a similar lesion that turned out to be squamous cell carcinoma—which eventually metastasized and led to his death.

TREATMENT

Treatment of more severe types of tinea capitis can be trying, even when the diagnosis is nailed down. The challenge becomes treating the problem long and strong enough to produce a cure.

In this case, I started the patient (who, at age 8, weighed 110 pounds) on a month-long course of terbinafine (250 mg/d) with a two-week taper of prednisone (40 mg). The expectation was that this would rapidly diminish the edema and pain while we waited for the culture results.

If the results showed the expected T tonsurans, treatment would continue as planned. If the cause turned out to be one of the Microsporum species, a switch to griseofulvin, at relatively high doses, would be considered.

ANSWER

The correct answer is oral terbinafine or griseofulvin, plus a two-week taper of prednisone (choice “d”); further discussion follows. Most authorities recommend the use of oral steroids with terbinafine (choice “a”) or griseofulvin (choice “b”), to dampen the acute inflammatory reaction to the fungal antigen. Some sources advise the use of itraconazole (choice “c”) but not as a single agent.

DISCUSSION

This case is a classic representation of kerion, a type of tinea capitis. This distinctive presentation results from not only active localized fungal infection with one of the dermatophytes, but also an allergic response to the fungal antigen. (This antigen can also trigger a widespread eczematous rash called an id reaction.) The resulting boggy, tender mass often oozes pus and usually provokes significant localized adenopathy.

A more common type of tinea capitis is uncomplicated dermatophytic infection of the scalp, presenting as mild localized scaling and modest hair loss, with no edema or redness to speak of. Kerion, by contrast, is far more acute and involves an impressive amount of localized redness and edema, along with modest hair loss, purulence, bloody drainage, and marked tenderness. Untreated, kerion can result in permanent scarring alopecia.

Several different dermatophytes have been isolated from kerions, including Trichophyton tonsurans, T violaceum, and various members of the Microsporum family. These zoophilic or geophilic organisms affect children far more than adults. Distinguishing the causative type is significant, because different drugs are required to effectively treat each. This is why a fungal culture is done at the outset.

When the diagnosis is in doubt, a punch biopsy may be necessary, with the sample divided for processing of default H&E stains and for fungal culture. Other information can be obtained by plucking a few hairs from the mass and examining them under 10x power to see if fungal hyphae are confined to the insides of the hair shafts (endothrix) or the outside of the shafts (ectothrix).

This is one situation in which KOH is not helpful for diagnosis: The organisms are too deep to obtain with a superficial scrape.

A number of scalp conditions can mimic a kerion, including lichen planopilaris and folliculitis decalvans. Several years ago, I had a patient who presented with a similar lesion that turned out to be squamous cell carcinoma—which eventually metastasized and led to his death.

TREATMENT

Treatment of more severe types of tinea capitis can be trying, even when the diagnosis is nailed down. The challenge becomes treating the problem long and strong enough to produce a cure.

In this case, I started the patient (who, at age 8, weighed 110 pounds) on a month-long course of terbinafine (250 mg/d) with a two-week taper of prednisone (40 mg). The expectation was that this would rapidly diminish the edema and pain while we waited for the culture results.

If the results showed the expected T tonsurans, treatment would continue as planned. If the cause turned out to be one of the Microsporum species, a switch to griseofulvin, at relatively high doses, would be considered.

Four weeks ago, an 8-year-old boy developed a lesion in his scalp that manifested rather quickly and caused pain. Treatment with both topical medications (triple-antibiotic cream and mupirocin cream) and oral antibiotics (cephalexin and trimethoprim/sulfa) has failed to resolve the problem, so his mother brings him to dermatology for evaluation. The patient is afebrile but complains of fatigue. His mother denies any other health problems for the child. There is no history of foreign travel, and the patient’s brother is healthy. The boy is in no acute distress but complains of tenderness on palpation of the lesion. The mass in his left nuchal scalp, which measures 4 cm, is impressively swollen, boggy, wet, and inflamed. Numerous red folliculocentric papules—many oozing pus—are seen on the surface. Located inferiorly to the lesion on the neck is a firm, palpable subcutaneous mass. Examination of the rest of the scalp reveals nothing of note. The clinical presentation and lack of response to oral antibiotics yield a presumptive diagnosis of kerion. A fungal culture is taken, with plans to prescribe appropriate medication.

Lesion Sprang Up Under His Nose (Well, to One Side, Actually …)

An 80-year-old man is brought in by family for evaluation of a lesion on his nose. It manifested several years ago, at a smaller size, but has recently and abruptly grown. Although asymptomatic, the lesion is disturbing to the patient, who can now see it out of the corner of his eye.

The patient worked all of his adult life in the outdoors, as a farm and ranch hand. He has an extensive history of nonmelanoma skin cancer; several lesions have been removed from his face and arm.

Since the patient lives alone and rarely has visitors, it has been months since anyone has seen him. But as soon as his son-in-law saw the patient, he was sufficiently alarmed by the lesion to insist that care be sought.

EXAMINATION

The patient’s facial skin shows abundant evidence of chronic, severe sun damage: a whitish, spongy look to the skin on his forehead and upper cheeks and a great deal of discoloration and scaling.

The lesion in question is a 3 x 1.5–cm, round, bulbous, smooth mass covering the right alar bulb. The surface is glassy-looking, with multiple telangiectasias. It is very firm but nontender on palpation. Shave biopsy is performed.

What is the diagnosis?

DISCUSSION

The biopsy results confirmed the suspicion of basal cell carcinoma (BCC). BCCs typically grow very slowly, often taking years to become noticeable, although not every BCC follows the rules. Some are more aggressive than others, both in terms of growth and clinical behavior.

It’s quite likely that in this case, the patient’s social isolation created the impression that his lesion grew abruptly and dramatically. (A subsequent eye exam revealed a number of problems, including severe presbyopia and advanced cataracts, so the patient himself might not have noticed the lesion for a while.) However, due to the large size and aggressive nature of the lesion—and the fact that the patient lives more than two hours from the nearest city, rendering his other treatment option, radiation, impractical—he was referred for Mohs surgery.

This process will establish clear surgical margins and provide acceptable closure. The latter may require reconstruction of the nose, depending on the depth of the cancer. Mohs surgeons often co-manage such cases with their counterparts in ENT or plastic surgery.

The differential for this lesion included keratoacanthoma , squamous cell carcinoma, and cyst.

TAKE-HOME LEARNING POINTS

• Basal cell carcinoma (BCC) is typically very slow growing, but there are exceptions.

• Social isolation can allow lesions and conditions to advance before they’re detected.

• Shave biopsy is indicated only for possible nonmelanoma skin cancers. Possible melanomas require excision, multiple punches, or deep shave to establish depth (a key prognostic factor).

• Rapid growth of BCCs suggests more aggressive clinical behavior, which in turn suggests the need for controlled margins to ensure complete removal.

An 80-year-old man is brought in by family for evaluation of a lesion on his nose. It manifested several years ago, at a smaller size, but has recently and abruptly grown. Although asymptomatic, the lesion is disturbing to the patient, who can now see it out of the corner of his eye.

The patient worked all of his adult life in the outdoors, as a farm and ranch hand. He has an extensive history of nonmelanoma skin cancer; several lesions have been removed from his face and arm.

Since the patient lives alone and rarely has visitors, it has been months since anyone has seen him. But as soon as his son-in-law saw the patient, he was sufficiently alarmed by the lesion to insist that care be sought.

EXAMINATION

The patient’s facial skin shows abundant evidence of chronic, severe sun damage: a whitish, spongy look to the skin on his forehead and upper cheeks and a great deal of discoloration and scaling.

The lesion in question is a 3 x 1.5–cm, round, bulbous, smooth mass covering the right alar bulb. The surface is glassy-looking, with multiple telangiectasias. It is very firm but nontender on palpation. Shave biopsy is performed.

What is the diagnosis?

DISCUSSION

The biopsy results confirmed the suspicion of basal cell carcinoma (BCC). BCCs typically grow very slowly, often taking years to become noticeable, although not every BCC follows the rules. Some are more aggressive than others, both in terms of growth and clinical behavior.

It’s quite likely that in this case, the patient’s social isolation created the impression that his lesion grew abruptly and dramatically. (A subsequent eye exam revealed a number of problems, including severe presbyopia and advanced cataracts, so the patient himself might not have noticed the lesion for a while.) However, due to the large size and aggressive nature of the lesion—and the fact that the patient lives more than two hours from the nearest city, rendering his other treatment option, radiation, impractical—he was referred for Mohs surgery.

This process will establish clear surgical margins and provide acceptable closure. The latter may require reconstruction of the nose, depending on the depth of the cancer. Mohs surgeons often co-manage such cases with their counterparts in ENT or plastic surgery.

The differential for this lesion included keratoacanthoma , squamous cell carcinoma, and cyst.

TAKE-HOME LEARNING POINTS

• Basal cell carcinoma (BCC) is typically very slow growing, but there are exceptions.

• Social isolation can allow lesions and conditions to advance before they’re detected.

• Shave biopsy is indicated only for possible nonmelanoma skin cancers. Possible melanomas require excision, multiple punches, or deep shave to establish depth (a key prognostic factor).

• Rapid growth of BCCs suggests more aggressive clinical behavior, which in turn suggests the need for controlled margins to ensure complete removal.

An 80-year-old man is brought in by family for evaluation of a lesion on his nose. It manifested several years ago, at a smaller size, but has recently and abruptly grown. Although asymptomatic, the lesion is disturbing to the patient, who can now see it out of the corner of his eye.

The patient worked all of his adult life in the outdoors, as a farm and ranch hand. He has an extensive history of nonmelanoma skin cancer; several lesions have been removed from his face and arm.

Since the patient lives alone and rarely has visitors, it has been months since anyone has seen him. But as soon as his son-in-law saw the patient, he was sufficiently alarmed by the lesion to insist that care be sought.

EXAMINATION

The patient’s facial skin shows abundant evidence of chronic, severe sun damage: a whitish, spongy look to the skin on his forehead and upper cheeks and a great deal of discoloration and scaling.

The lesion in question is a 3 x 1.5–cm, round, bulbous, smooth mass covering the right alar bulb. The surface is glassy-looking, with multiple telangiectasias. It is very firm but nontender on palpation. Shave biopsy is performed.

What is the diagnosis?

DISCUSSION

The biopsy results confirmed the suspicion of basal cell carcinoma (BCC). BCCs typically grow very slowly, often taking years to become noticeable, although not every BCC follows the rules. Some are more aggressive than others, both in terms of growth and clinical behavior.

It’s quite likely that in this case, the patient’s social isolation created the impression that his lesion grew abruptly and dramatically. (A subsequent eye exam revealed a number of problems, including severe presbyopia and advanced cataracts, so the patient himself might not have noticed the lesion for a while.) However, due to the large size and aggressive nature of the lesion—and the fact that the patient lives more than two hours from the nearest city, rendering his other treatment option, radiation, impractical—he was referred for Mohs surgery.

This process will establish clear surgical margins and provide acceptable closure. The latter may require reconstruction of the nose, depending on the depth of the cancer. Mohs surgeons often co-manage such cases with their counterparts in ENT or plastic surgery.

The differential for this lesion included keratoacanthoma , squamous cell carcinoma, and cyst.

TAKE-HOME LEARNING POINTS

• Basal cell carcinoma (BCC) is typically very slow growing, but there are exceptions.

• Social isolation can allow lesions and conditions to advance before they’re detected.

• Shave biopsy is indicated only for possible nonmelanoma skin cancers. Possible melanomas require excision, multiple punches, or deep shave to establish depth (a key prognostic factor).

• Rapid growth of BCCs suggests more aggressive clinical behavior, which in turn suggests the need for controlled margins to ensure complete removal.

The Eyes Have It, and It Itches Like Crazy

For several months, a 69-year-old woman has had a rash around her eyes. It is terribly symptomatic, burning and itching with or without treatment (attempts at which have encompassed moisturizers, petroleum jelly, topical vitamin E oil, and most recently, application of triple-antibiotic cream three times a day). She finally requests referral to dermatology from her primary care provider.

When the rash manifested, she reports, she made some alterations to her routine, eliminating or changing the type of makeup, soap, cleanser, and laundry detergent she used. None of these changes helped.

Even before the distressing symptoms started, a friend had suggested the patient might have an eye problem. She consulted an ophthalmologist, who prescribed eye drops (the patient doesn’t recall any details); these only produced more burning and itching around her eyes.

The patient’s history is significant for atopy, with a childhood history of seasonal allergies, asthma, and eczema.

EXAMINATION

There is marked erythema and scaling in the bilateral periocular areas that spills onto both upper and lower lids. Very little edema is seen. The eyes themselves are free of changes.

What is the diagnosis?

DISCUSSION

For many patients, any problem that manifests close to the eye is deemed an “eye problem,” even when the eye itself is uninvolved. Eyelid dermatitis is an extremely common complaint, and this patient’s history is quite typical: The worse the problem gets, the more attempts the patient makes to relieve symptoms.

When this patient presented to dermatology, she was applying six different products (all OTC) to the affected areas. None helped, and in fact, most seemed to worsen the problem. Even if one had helped, she would never have known which. But desperation drives patients to do irrational things, especially when the problem is out in the open for the whole world to see.

Virtually every patient I’ve seen with eyelid dermatitis has (like this patient) already stopped using makeup and changed or discontinued use of laundry detergent and other products. These are almost never the problem; if any of them were, the effects would not be so sharply limited to the periocular area.

Rather, the sharp margins of this condition suggested irritant contact dermatitis. It often appears in this context: The periocular skin is unique in that it’s the thinnest in the female body. This means it is easily traumatized by rubbing and scratching and can be quite permeable to various contactants. This is especially true in atopic patients, whose skin is not only thin and dry but also overreactive to insult.

Though we may never know the full story, I suspect this patient had a more modest case of eczema on her eyelids until she began to apply product after product. One of them—triple-antibiotic cream—is a notorious topical sensitizer. In one sense, this patient is a victim of overattention to the problem.

I advised her to stop use of all the contactants and prescribed hydrocortisone 2.5% ointment for twice-daily application. I also gave her a prescription for a two-week taper of prednisone. When she returned for follow-up three weeks later, the rash was completely resolved.

Other conditions that can cause eyelid dermatitis include seborrhea and psoriasis.

TAKE-HOME LEARNING POINTS

• Eyelid dermatitis, an extremely common complaint, is rarely seen in men and is almost never caused by makeup, soap, or shampoo.

• Eyelid dermatitis is not an eye problem—rather, it is a skin problem that happens to occur near the eye.

• The differential for eyelid dermatitis includes atopic dermatitis, seborrhea and psoriasis.

• Stopping use of all contactant products (except prescription medications) is necessary.

• Class 5 or 6 steroids, especially hydrocortisone 2.5% in ointment form, are useful. In severe cases, a tapering course of oral glucocorticoids (prednisone) is extremely helpful.

For several months, a 69-year-old woman has had a rash around her eyes. It is terribly symptomatic, burning and itching with or without treatment (attempts at which have encompassed moisturizers, petroleum jelly, topical vitamin E oil, and most recently, application of triple-antibiotic cream three times a day). She finally requests referral to dermatology from her primary care provider.

When the rash manifested, she reports, she made some alterations to her routine, eliminating or changing the type of makeup, soap, cleanser, and laundry detergent she used. None of these changes helped.

Even before the distressing symptoms started, a friend had suggested the patient might have an eye problem. She consulted an ophthalmologist, who prescribed eye drops (the patient doesn’t recall any details); these only produced more burning and itching around her eyes.

The patient’s history is significant for atopy, with a childhood history of seasonal allergies, asthma, and eczema.

EXAMINATION

There is marked erythema and scaling in the bilateral periocular areas that spills onto both upper and lower lids. Very little edema is seen. The eyes themselves are free of changes.

What is the diagnosis?

DISCUSSION

For many patients, any problem that manifests close to the eye is deemed an “eye problem,” even when the eye itself is uninvolved. Eyelid dermatitis is an extremely common complaint, and this patient’s history is quite typical: The worse the problem gets, the more attempts the patient makes to relieve symptoms.

When this patient presented to dermatology, she was applying six different products (all OTC) to the affected areas. None helped, and in fact, most seemed to worsen the problem. Even if one had helped, she would never have known which. But desperation drives patients to do irrational things, especially when the problem is out in the open for the whole world to see.

Virtually every patient I’ve seen with eyelid dermatitis has (like this patient) already stopped using makeup and changed or discontinued use of laundry detergent and other products. These are almost never the problem; if any of them were, the effects would not be so sharply limited to the periocular area.

Rather, the sharp margins of this condition suggested irritant contact dermatitis. It often appears in this context: The periocular skin is unique in that it’s the thinnest in the female body. This means it is easily traumatized by rubbing and scratching and can be quite permeable to various contactants. This is especially true in atopic patients, whose skin is not only thin and dry but also overreactive to insult.

Though we may never know the full story, I suspect this patient had a more modest case of eczema on her eyelids until she began to apply product after product. One of them—triple-antibiotic cream—is a notorious topical sensitizer. In one sense, this patient is a victim of overattention to the problem.

I advised her to stop use of all the contactants and prescribed hydrocortisone 2.5% ointment for twice-daily application. I also gave her a prescription for a two-week taper of prednisone. When she returned for follow-up three weeks later, the rash was completely resolved.

Other conditions that can cause eyelid dermatitis include seborrhea and psoriasis.

TAKE-HOME LEARNING POINTS

• Eyelid dermatitis, an extremely common complaint, is rarely seen in men and is almost never caused by makeup, soap, or shampoo.

• Eyelid dermatitis is not an eye problem—rather, it is a skin problem that happens to occur near the eye.

• The differential for eyelid dermatitis includes atopic dermatitis, seborrhea and psoriasis.

• Stopping use of all contactant products (except prescription medications) is necessary.

• Class 5 or 6 steroids, especially hydrocortisone 2.5% in ointment form, are useful. In severe cases, a tapering course of oral glucocorticoids (prednisone) is extremely helpful.

For several months, a 69-year-old woman has had a rash around her eyes. It is terribly symptomatic, burning and itching with or without treatment (attempts at which have encompassed moisturizers, petroleum jelly, topical vitamin E oil, and most recently, application of triple-antibiotic cream three times a day). She finally requests referral to dermatology from her primary care provider.

When the rash manifested, she reports, she made some alterations to her routine, eliminating or changing the type of makeup, soap, cleanser, and laundry detergent she used. None of these changes helped.

Even before the distressing symptoms started, a friend had suggested the patient might have an eye problem. She consulted an ophthalmologist, who prescribed eye drops (the patient doesn’t recall any details); these only produced more burning and itching around her eyes.

The patient’s history is significant for atopy, with a childhood history of seasonal allergies, asthma, and eczema.

EXAMINATION

There is marked erythema and scaling in the bilateral periocular areas that spills onto both upper and lower lids. Very little edema is seen. The eyes themselves are free of changes.

What is the diagnosis?

DISCUSSION

For many patients, any problem that manifests close to the eye is deemed an “eye problem,” even when the eye itself is uninvolved. Eyelid dermatitis is an extremely common complaint, and this patient’s history is quite typical: The worse the problem gets, the more attempts the patient makes to relieve symptoms.

When this patient presented to dermatology, she was applying six different products (all OTC) to the affected areas. None helped, and in fact, most seemed to worsen the problem. Even if one had helped, she would never have known which. But desperation drives patients to do irrational things, especially when the problem is out in the open for the whole world to see.

Virtually every patient I’ve seen with eyelid dermatitis has (like this patient) already stopped using makeup and changed or discontinued use of laundry detergent and other products. These are almost never the problem; if any of them were, the effects would not be so sharply limited to the periocular area.

Rather, the sharp margins of this condition suggested irritant contact dermatitis. It often appears in this context: The periocular skin is unique in that it’s the thinnest in the female body. This means it is easily traumatized by rubbing and scratching and can be quite permeable to various contactants. This is especially true in atopic patients, whose skin is not only thin and dry but also overreactive to insult.

Though we may never know the full story, I suspect this patient had a more modest case of eczema on her eyelids until she began to apply product after product. One of them—triple-antibiotic cream—is a notorious topical sensitizer. In one sense, this patient is a victim of overattention to the problem.

I advised her to stop use of all the contactants and prescribed hydrocortisone 2.5% ointment for twice-daily application. I also gave her a prescription for a two-week taper of prednisone. When she returned for follow-up three weeks later, the rash was completely resolved.

Other conditions that can cause eyelid dermatitis include seborrhea and psoriasis.

TAKE-HOME LEARNING POINTS

• Eyelid dermatitis, an extremely common complaint, is rarely seen in men and is almost never caused by makeup, soap, or shampoo.

• Eyelid dermatitis is not an eye problem—rather, it is a skin problem that happens to occur near the eye.

• The differential for eyelid dermatitis includes atopic dermatitis, seborrhea and psoriasis.

• Stopping use of all contactant products (except prescription medications) is necessary.

• Class 5 or 6 steroids, especially hydrocortisone 2.5% in ointment form, are useful. In severe cases, a tapering course of oral glucocorticoids (prednisone) is extremely helpful.

Alarming Lesion Speaks for Itself

ANSWER

The correct answer is “all of the above” (choice “d”), for reasons discussed in the next section.

DISCUSSION

Cutaneous horn is the term given to this type of keratotic lesion, for obvious reasons. They range in size from a pinpoint to the larger lesion seen on this patient (and sometimes, even larger). The pathology report in this case confirmed the clinical impression of well-differentiated squamous cell carcinoma (SCC; choice “c”); sun exposure is the most likely causative factor, given the location and the patient’s history of sun damage.

The lesion might have been a wart (choice “a”) caused by a human papillomavirus, some of which can trigger the formation of a type of SCC. Evidence of HPV involvement is often noted in the pathology report.

When skin lesions transition from normal to sun-damaged to cancerous, they often go through an actinic keratosis (choice “b”) stage, usually as a tiny hyperkeratotic papule on the forehead, ears, nose, or other directly sun-exposed area. Some consider actinic keratoses to be a form of early SCC; more prevalent is the view that they are merely “precancerous” with the potential to develop into either a frank SCC or, less often, a basal cell carcinoma. Some actinic keratoses, left completely unmolested, can develop into tag-like lesions and then horny outward projections.

Even when cutaneous horns are found to represent SCC, they are termed well-differentiated, a descriptor meant to denote a relatively benign and nonaggressive prognosis. This is the opposite of a poorly differentiated SCC, which would be expected to behave in a more aggressive, less predictable manner.

For well-differentiated lesions, a deep shave biopsy is probably an adequate method of removal. As such, the case patient did not require re-excision. He was, however, scheduled for a return visit to check the site for the (albeit unlikely) possibility of recurrence.

ANSWER

The correct answer is “all of the above” (choice “d”), for reasons discussed in the next section.

DISCUSSION

Cutaneous horn is the term given to this type of keratotic lesion, for obvious reasons. They range in size from a pinpoint to the larger lesion seen on this patient (and sometimes, even larger). The pathology report in this case confirmed the clinical impression of well-differentiated squamous cell carcinoma (SCC; choice “c”); sun exposure is the most likely causative factor, given the location and the patient’s history of sun damage.

The lesion might have been a wart (choice “a”) caused by a human papillomavirus, some of which can trigger the formation of a type of SCC. Evidence of HPV involvement is often noted in the pathology report.

When skin lesions transition from normal to sun-damaged to cancerous, they often go through an actinic keratosis (choice “b”) stage, usually as a tiny hyperkeratotic papule on the forehead, ears, nose, or other directly sun-exposed area. Some consider actinic keratoses to be a form of early SCC; more prevalent is the view that they are merely “precancerous” with the potential to develop into either a frank SCC or, less often, a basal cell carcinoma. Some actinic keratoses, left completely unmolested, can develop into tag-like lesions and then horny outward projections.

Even when cutaneous horns are found to represent SCC, they are termed well-differentiated, a descriptor meant to denote a relatively benign and nonaggressive prognosis. This is the opposite of a poorly differentiated SCC, which would be expected to behave in a more aggressive, less predictable manner.

For well-differentiated lesions, a deep shave biopsy is probably an adequate method of removal. As such, the case patient did not require re-excision. He was, however, scheduled for a return visit to check the site for the (albeit unlikely) possibility of recurrence.

ANSWER

The correct answer is “all of the above” (choice “d”), for reasons discussed in the next section.

DISCUSSION

Cutaneous horn is the term given to this type of keratotic lesion, for obvious reasons. They range in size from a pinpoint to the larger lesion seen on this patient (and sometimes, even larger). The pathology report in this case confirmed the clinical impression of well-differentiated squamous cell carcinoma (SCC; choice “c”); sun exposure is the most likely causative factor, given the location and the patient’s history of sun damage.

The lesion might have been a wart (choice “a”) caused by a human papillomavirus, some of which can trigger the formation of a type of SCC. Evidence of HPV involvement is often noted in the pathology report.

When skin lesions transition from normal to sun-damaged to cancerous, they often go through an actinic keratosis (choice “b”) stage, usually as a tiny hyperkeratotic papule on the forehead, ears, nose, or other directly sun-exposed area. Some consider actinic keratoses to be a form of early SCC; more prevalent is the view that they are merely “precancerous” with the potential to develop into either a frank SCC or, less often, a basal cell carcinoma. Some actinic keratoses, left completely unmolested, can develop into tag-like lesions and then horny outward projections.

Even when cutaneous horns are found to represent SCC, they are termed well-differentiated, a descriptor meant to denote a relatively benign and nonaggressive prognosis. This is the opposite of a poorly differentiated SCC, which would be expected to behave in a more aggressive, less predictable manner.

For well-differentiated lesions, a deep shave biopsy is probably an adequate method of removal. As such, the case patient did not require re-excision. He was, however, scheduled for a return visit to check the site for the (albeit unlikely) possibility of recurrence.

Two years ago, this 82-year-old man developed a lesion on his forehead that has since grown large enough to cause pain with trauma. Furthermore, he recently reunited with some estranged family members, who upon seeing the lesion for the first time expressed alarm at its appearance. As a result, he requests a referral to dermatology for evaluation. The patient’s history includes several instances of skin cancer; these began when he was in his 40s and have all occurred on his face and scalp. Examination of those areas reveals heavy chronic sun damage, including solar elastosis, solar lentigines, and multiple relatively minor actinic keratoses. The patient has type II skin. An impressive 3 x 2.8–cm hornlike keratotic lesion projects prominently from his left forehead. The distal two-thirds is horny and firm, while the proximal base is pink, fleshy, and telangiectatic. The lesion is removed by saucerization under local anesthesia and submitted to pathology.

Can You Nail the Diagnosis? (It’s Not Fungal)

A 50-year-old man is sent to dermatology for evaluation of a “fungal infection” affecting both of his thumbnails. In the past several years, treatment with at least two courses of oral terbinafine and numerous topical antifungal creams has failed to produce any improvement in the problem. The patient denies any nail-related symptoms or trauma to his thumbs.

The patient claims to be otherwise healthy. On further questioning, however, he admits to having intermittent joint pain and swelling, especially in one ankle. He adds that for the past several years, he has experienced severe back pain and stiffness in the morning.

EXAMINATION

The patient looks his stated age, is in no acute distress, and is well developed and well nourished.

Both thumbnails demonstrate identical changes: separation of the distal one-third of the nail plate from the nail bed and yellowish discoloration of that portion of the nails. In and under the nail plate, fine, short, longitudinal black streaks are seen. Proximally, a well-defined brown band is observed in the subungual areas. The patient’s other nails are unaffected.

Broader examination reveals a salmon-pink rash with white scale covering the periumbilical area. A similar rash is seen in the upper intergluteal area.

What is the diagnosis?

DISCUSSION

All these findings add up to the diagnosis of psoriasis vulgaris, or common psoriasis, a disease that affects almost 3% of the US population and is far less common in persons with darker skin. This inflammatory condition, thought to be of autoimmune origin, manifested in predictable ways in this patient, who most likely inherited the genetic predisposition for the disease.

Although numerous related chromosomal abnormalities have been identified, environmental factors often play a role in psoriasis as well. These include antecedent strep infection, stress, smoking, obesity, alcohol intake, and use of certain medications (eg, beta-blockers, lithium).

Psoriasis is known to affect nails. The changes in this patient are classic: onycholysis (separation of the nail plate from the nail bed), deformed nails (known as dystrophy), yellow-brown discoloration (so-called oil spotting), and often, splinter hemorrhages. Nail pitting, though not seen in this case, is also common.

For some psoriasis patients, nail involvement is the sole manifestation of the disease. But more often, observing these nail changes prompts the provider to look elsewhere for corroborative findings, of which periumbilical and upper intergluteal involvement are typical.

Seen in a diagnostic vacuum, such nail changes are often diagnosed as “fungal infection.” This overlooks the fact that fungal infection is far less common in the fingernails than in toenails. In fact, there are several other items in the differential for nail changes, including lichen planus, eczema, and chronic candidal paronychia.

Had fungal infection (onychomycosis) been a serious possibility, culture or histologic examination of a sample of nail plate could have been confirmatory. First, though, the other items in the differential should have been considered. (I’ve said it before, in a variety of contexts: If your only explanation for discolored and misshapen nails is fungal infection, that’s a problem.)

This patient’s skin disease was initially treated with topical steroids. However, due to his joint symptoms and the possibility of psoriatic arthropathy, he was also referred to rheumatology. It’s entirely possible that he’ll be prescribed a biologic, which will eliminate his otherwise-problematic-to-treat nail psoriasis.

TAKE-HOME LEARNING POINTS

• Since fungal infection of the fingernails is distinctly uncommon, other items in the differential should be considered in such cases.

• Other potential diagnostic explanations for nail changes include lichen planus, eczema, and chronic candidal paronychia.

• Nail changes can be the sole manifestation of psoriasis in a given patient.

• Evaluation should include other areas of involvement that exhibit “classic” signs of psoriasis, including extensor surfaces and periumbilical and upper intergluteal skin.

A 50-year-old man is sent to dermatology for evaluation of a “fungal infection” affecting both of his thumbnails. In the past several years, treatment with at least two courses of oral terbinafine and numerous topical antifungal creams has failed to produce any improvement in the problem. The patient denies any nail-related symptoms or trauma to his thumbs.

The patient claims to be otherwise healthy. On further questioning, however, he admits to having intermittent joint pain and swelling, especially in one ankle. He adds that for the past several years, he has experienced severe back pain and stiffness in the morning.

EXAMINATION

The patient looks his stated age, is in no acute distress, and is well developed and well nourished.

Both thumbnails demonstrate identical changes: separation of the distal one-third of the nail plate from the nail bed and yellowish discoloration of that portion of the nails. In and under the nail plate, fine, short, longitudinal black streaks are seen. Proximally, a well-defined brown band is observed in the subungual areas. The patient’s other nails are unaffected.

Broader examination reveals a salmon-pink rash with white scale covering the periumbilical area. A similar rash is seen in the upper intergluteal area.

What is the diagnosis?

DISCUSSION

All these findings add up to the diagnosis of psoriasis vulgaris, or common psoriasis, a disease that affects almost 3% of the US population and is far less common in persons with darker skin. This inflammatory condition, thought to be of autoimmune origin, manifested in predictable ways in this patient, who most likely inherited the genetic predisposition for the disease.

Although numerous related chromosomal abnormalities have been identified, environmental factors often play a role in psoriasis as well. These include antecedent strep infection, stress, smoking, obesity, alcohol intake, and use of certain medications (eg, beta-blockers, lithium).

Psoriasis is known to affect nails. The changes in this patient are classic: onycholysis (separation of the nail plate from the nail bed), deformed nails (known as dystrophy), yellow-brown discoloration (so-called oil spotting), and often, splinter hemorrhages. Nail pitting, though not seen in this case, is also common.

For some psoriasis patients, nail involvement is the sole manifestation of the disease. But more often, observing these nail changes prompts the provider to look elsewhere for corroborative findings, of which periumbilical and upper intergluteal involvement are typical.

Seen in a diagnostic vacuum, such nail changes are often diagnosed as “fungal infection.” This overlooks the fact that fungal infection is far less common in the fingernails than in toenails. In fact, there are several other items in the differential for nail changes, including lichen planus, eczema, and chronic candidal paronychia.

Had fungal infection (onychomycosis) been a serious possibility, culture or histologic examination of a sample of nail plate could have been confirmatory. First, though, the other items in the differential should have been considered. (I’ve said it before, in a variety of contexts: If your only explanation for discolored and misshapen nails is fungal infection, that’s a problem.)

This patient’s skin disease was initially treated with topical steroids. However, due to his joint symptoms and the possibility of psoriatic arthropathy, he was also referred to rheumatology. It’s entirely possible that he’ll be prescribed a biologic, which will eliminate his otherwise-problematic-to-treat nail psoriasis.

TAKE-HOME LEARNING POINTS

• Since fungal infection of the fingernails is distinctly uncommon, other items in the differential should be considered in such cases.

• Other potential diagnostic explanations for nail changes include lichen planus, eczema, and chronic candidal paronychia.

• Nail changes can be the sole manifestation of psoriasis in a given patient.

• Evaluation should include other areas of involvement that exhibit “classic” signs of psoriasis, including extensor surfaces and periumbilical and upper intergluteal skin.

A 50-year-old man is sent to dermatology for evaluation of a “fungal infection” affecting both of his thumbnails. In the past several years, treatment with at least two courses of oral terbinafine and numerous topical antifungal creams has failed to produce any improvement in the problem. The patient denies any nail-related symptoms or trauma to his thumbs.

The patient claims to be otherwise healthy. On further questioning, however, he admits to having intermittent joint pain and swelling, especially in one ankle. He adds that for the past several years, he has experienced severe back pain and stiffness in the morning.

EXAMINATION

The patient looks his stated age, is in no acute distress, and is well developed and well nourished.

Both thumbnails demonstrate identical changes: separation of the distal one-third of the nail plate from the nail bed and yellowish discoloration of that portion of the nails. In and under the nail plate, fine, short, longitudinal black streaks are seen. Proximally, a well-defined brown band is observed in the subungual areas. The patient’s other nails are unaffected.

Broader examination reveals a salmon-pink rash with white scale covering the periumbilical area. A similar rash is seen in the upper intergluteal area.

What is the diagnosis?

DISCUSSION

All these findings add up to the diagnosis of psoriasis vulgaris, or common psoriasis, a disease that affects almost 3% of the US population and is far less common in persons with darker skin. This inflammatory condition, thought to be of autoimmune origin, manifested in predictable ways in this patient, who most likely inherited the genetic predisposition for the disease.

Although numerous related chromosomal abnormalities have been identified, environmental factors often play a role in psoriasis as well. These include antecedent strep infection, stress, smoking, obesity, alcohol intake, and use of certain medications (eg, beta-blockers, lithium).

Psoriasis is known to affect nails. The changes in this patient are classic: onycholysis (separation of the nail plate from the nail bed), deformed nails (known as dystrophy), yellow-brown discoloration (so-called oil spotting), and often, splinter hemorrhages. Nail pitting, though not seen in this case, is also common.

For some psoriasis patients, nail involvement is the sole manifestation of the disease. But more often, observing these nail changes prompts the provider to look elsewhere for corroborative findings, of which periumbilical and upper intergluteal involvement are typical.

Seen in a diagnostic vacuum, such nail changes are often diagnosed as “fungal infection.” This overlooks the fact that fungal infection is far less common in the fingernails than in toenails. In fact, there are several other items in the differential for nail changes, including lichen planus, eczema, and chronic candidal paronychia.

Had fungal infection (onychomycosis) been a serious possibility, culture or histologic examination of a sample of nail plate could have been confirmatory. First, though, the other items in the differential should have been considered. (I’ve said it before, in a variety of contexts: If your only explanation for discolored and misshapen nails is fungal infection, that’s a problem.)

This patient’s skin disease was initially treated with topical steroids. However, due to his joint symptoms and the possibility of psoriatic arthropathy, he was also referred to rheumatology. It’s entirely possible that he’ll be prescribed a biologic, which will eliminate his otherwise-problematic-to-treat nail psoriasis.

TAKE-HOME LEARNING POINTS

• Since fungal infection of the fingernails is distinctly uncommon, other items in the differential should be considered in such cases.

• Other potential diagnostic explanations for nail changes include lichen planus, eczema, and chronic candidal paronychia.

• Nail changes can be the sole manifestation of psoriasis in a given patient.

• Evaluation should include other areas of involvement that exhibit “classic” signs of psoriasis, including extensor surfaces and periumbilical and upper intergluteal skin.

Bluish Pink, Nontender Lesion Worries Patient’s Mother

A 12-year-old girl is brought to dermatology by her mother for evaluation of a lesion on her arm. It’s been there for two years without causing symptoms—but lately it has grown, as has the mother’s concern.

The child is otherwise healthy. The mother reports that the child has neither a personal nor a family history of seizures.

EXAMINATION

A solitary, firm, subcutaneous nodule measuring 2 cm is located on the lateral aspect of the child’s left triceps. It is bluish pink, nontender, and firm on palpation. No other overlying skin changes are seen.

Lateral digital traction toward the center of the lesion produces no dimpling, while lateral traction toward its periphery accentuates the lesion’s central raised portion. The lesion is moderately mobile. No lymph nodes are felt on palpation of nodal sites in the area, and no other such lesions are found elsewhere on the child’s skin.

What is the diagnosis?

DISCUSSION

At this point, the differential included items such as pilomatricoma, dermatofibroma, calcinosis cutis, or epidermal cyst. The firm feel, bluish color, and shallow subcutaneous location of the lesion lent themselves to a provisional diagnosis of pilomatricoma, as did the patient’s age. But the fact that the lesion was changing was of sufficient concern to prompt removal.

Excision revealed a cystic lesion with cottage-cheese–like contents and a poorly defined wall, extending more than a centimeter into the subcutaneous tissue. It was removed in one piece and submitted to pathology. Primary closure completed the procedure.

The pathology report showed sheets of anucleate squamous cells (called ghost cells), benign viable nucleated squamous cells, and a center filled with multiple soft calcified granules. A positive von Kossa stain confirmed the expected diagnosis of pilomatricoma (PMC; also spelled pilomatrixoma).

PMCs, also known by their eponymous designation of calcifying epithelioma of Malherbe, are common, benign appendageal tumors derived from hair matrix. They usually manifest (as in this case) as a solitary subcutaneous firm mass, often with bluish discoloration, on the face, neck, or upper extremities. While they average around 2 cm, they can be as large as 15 cm in diameter. They are more common in children and occur slightly more often in girls.

There is some evidence that the tendency to develop PMCs is associated with increased levels of beta-catenin, which encourages cell growth by diminishing apoptosis. This mechanism is thought to promote malignant transformation of PMCs—a rare event.

As is often the case, the main concern about this patient’s lesion related to its unknown source and recent alteration. Aside from scarring, the patient was no worse off for its removal—and her mother was much relieved.

TAKE-HOME LEARNING POINTS

• PMCs are benign cystic lesions of appendageal origin, commonly found on the necks, faces, and upper extremities of children.

• Diagnostic clues for PMC include firm feel, subcutaneous location, bluish discoloration, and patient age.

• PMCs have poorly defined cyst walls and granular calcified contents.

• Except when occurring in multiples, PMCs have no pathologic implications.

• The term calcifying epithelioma of Malherbe is still in use, as is the alternate spelling of pilomatrixoma.

A 12-year-old girl is brought to dermatology by her mother for evaluation of a lesion on her arm. It’s been there for two years without causing symptoms—but lately it has grown, as has the mother’s concern.

The child is otherwise healthy. The mother reports that the child has neither a personal nor a family history of seizures.

EXAMINATION

A solitary, firm, subcutaneous nodule measuring 2 cm is located on the lateral aspect of the child’s left triceps. It is bluish pink, nontender, and firm on palpation. No other overlying skin changes are seen.

Lateral digital traction toward the center of the lesion produces no dimpling, while lateral traction toward its periphery accentuates the lesion’s central raised portion. The lesion is moderately mobile. No lymph nodes are felt on palpation of nodal sites in the area, and no other such lesions are found elsewhere on the child’s skin.

What is the diagnosis?

DISCUSSION

At this point, the differential included items such as pilomatricoma, dermatofibroma, calcinosis cutis, or epidermal cyst. The firm feel, bluish color, and shallow subcutaneous location of the lesion lent themselves to a provisional diagnosis of pilomatricoma, as did the patient’s age. But the fact that the lesion was changing was of sufficient concern to prompt removal.

Excision revealed a cystic lesion with cottage-cheese–like contents and a poorly defined wall, extending more than a centimeter into the subcutaneous tissue. It was removed in one piece and submitted to pathology. Primary closure completed the procedure.

The pathology report showed sheets of anucleate squamous cells (called ghost cells), benign viable nucleated squamous cells, and a center filled with multiple soft calcified granules. A positive von Kossa stain confirmed the expected diagnosis of pilomatricoma (PMC; also spelled pilomatrixoma).

PMCs, also known by their eponymous designation of calcifying epithelioma of Malherbe, are common, benign appendageal tumors derived from hair matrix. They usually manifest (as in this case) as a solitary subcutaneous firm mass, often with bluish discoloration, on the face, neck, or upper extremities. While they average around 2 cm, they can be as large as 15 cm in diameter. They are more common in children and occur slightly more often in girls.

There is some evidence that the tendency to develop PMCs is associated with increased levels of beta-catenin, which encourages cell growth by diminishing apoptosis. This mechanism is thought to promote malignant transformation of PMCs—a rare event.

As is often the case, the main concern about this patient’s lesion related to its unknown source and recent alteration. Aside from scarring, the patient was no worse off for its removal—and her mother was much relieved.

TAKE-HOME LEARNING POINTS

• PMCs are benign cystic lesions of appendageal origin, commonly found on the necks, faces, and upper extremities of children.

• Diagnostic clues for PMC include firm feel, subcutaneous location, bluish discoloration, and patient age.

• PMCs have poorly defined cyst walls and granular calcified contents.

• Except when occurring in multiples, PMCs have no pathologic implications.

• The term calcifying epithelioma of Malherbe is still in use, as is the alternate spelling of pilomatrixoma.

A 12-year-old girl is brought to dermatology by her mother for evaluation of a lesion on her arm. It’s been there for two years without causing symptoms—but lately it has grown, as has the mother’s concern.

The child is otherwise healthy. The mother reports that the child has neither a personal nor a family history of seizures.

EXAMINATION

A solitary, firm, subcutaneous nodule measuring 2 cm is located on the lateral aspect of the child’s left triceps. It is bluish pink, nontender, and firm on palpation. No other overlying skin changes are seen.

Lateral digital traction toward the center of the lesion produces no dimpling, while lateral traction toward its periphery accentuates the lesion’s central raised portion. The lesion is moderately mobile. No lymph nodes are felt on palpation of nodal sites in the area, and no other such lesions are found elsewhere on the child’s skin.

What is the diagnosis?

DISCUSSION

At this point, the differential included items such as pilomatricoma, dermatofibroma, calcinosis cutis, or epidermal cyst. The firm feel, bluish color, and shallow subcutaneous location of the lesion lent themselves to a provisional diagnosis of pilomatricoma, as did the patient’s age. But the fact that the lesion was changing was of sufficient concern to prompt removal.

Excision revealed a cystic lesion with cottage-cheese–like contents and a poorly defined wall, extending more than a centimeter into the subcutaneous tissue. It was removed in one piece and submitted to pathology. Primary closure completed the procedure.

The pathology report showed sheets of anucleate squamous cells (called ghost cells), benign viable nucleated squamous cells, and a center filled with multiple soft calcified granules. A positive von Kossa stain confirmed the expected diagnosis of pilomatricoma (PMC; also spelled pilomatrixoma).

PMCs, also known by their eponymous designation of calcifying epithelioma of Malherbe, are common, benign appendageal tumors derived from hair matrix. They usually manifest (as in this case) as a solitary subcutaneous firm mass, often with bluish discoloration, on the face, neck, or upper extremities. While they average around 2 cm, they can be as large as 15 cm in diameter. They are more common in children and occur slightly more often in girls.

There is some evidence that the tendency to develop PMCs is associated with increased levels of beta-catenin, which encourages cell growth by diminishing apoptosis. This mechanism is thought to promote malignant transformation of PMCs—a rare event.

As is often the case, the main concern about this patient’s lesion related to its unknown source and recent alteration. Aside from scarring, the patient was no worse off for its removal—and her mother was much relieved.

TAKE-HOME LEARNING POINTS

• PMCs are benign cystic lesions of appendageal origin, commonly found on the necks, faces, and upper extremities of children.

• Diagnostic clues for PMC include firm feel, subcutaneous location, bluish discoloration, and patient age.

• PMCs have poorly defined cyst walls and granular calcified contents.

• Except when occurring in multiples, PMCs have no pathologic implications.

• The term calcifying epithelioma of Malherbe is still in use, as is the alternate spelling of pilomatrixoma.

Girl, 10, Asks Tough Questions About Skin Problem

A 10-year-old girl is seen in dermatology for evaluation of dry skin. She reports few if any symptoms but expresses frustration at her inability to curb the problem; she’s tried several different moisturizers to no avail.

Additional history-taking reveals that she’s had patches of dry skin since age 4; these have appeared and disappeared on her arms, legs, and neck. None has ever been problematic enough to require medical attention.

But recently, a dry patch manifested on the patient’s forearm that her primary care provider diagnosed as fungal infection. Unfortunately, the prescribed antifungal creams (terbinafine and clotrimazole) had no positive impact on the situation.

The patient and her mother deny any family history of skin disease.

EXAMINATION

The scaly, annular plaque on the patient’s extensor left forearm is distinctly salmon-pink, with a tenacious white scale. Elsewhere, there are scaly areas in both post-auricular sulci. There are no significant changes to the skin on the patient’s knees, elbows, or scalp. Several tiny pits are observed on her fingernails.

What is the diagnosis?

DISCUSSION

It would be difficult to imagine a more clear-cut case of psoriasis: not only manifesting with a classic plaque on the left extensor forearm but also with corroboratory stigmata behind the ears and classic fingernail pits. Then why, you might ask, was the diagnosis missed?

Psoriasis has a classic look: annular borders, salmon-pink color, and thick, tenacious scale. Distribution matters, since the condition tends to manifest in specific areas, particularly the extensor portions of extremities. It’s helpful to know that psoriasis affects almost 3% of the white population in the United States, meaning that you will see it with considerable frequency. It would also help if you knew the diagnosis can be corroborated by identification of other, lesser known features.

But if you’re unaware of these facts, you won’t look for these things—and if you don’t look specifically for them, you won’t see them. Then, to add insult to injury, when you consult your bag of “diseases that present with annular borders and scaly surfaces,” you’ll find one item in your differential: fungal infection. When antifungal medications don’t work, you’ll find yourself stuck, because you simply don’t have any other diagnoses to consider.

I’ve known internists who have practiced for more than 25 years and still make this diagnostic mistake. So it’s not a matter of lack of intelligence. They simply do not invest the time to expand their knowledge of dermatologic conditions.

My job was to break the news to the patient and her mother about the diagnosis and, perhaps more importantly, her prognosis. The only good news is that the patient is living in the golden age of psoriasis treatment; if her condition flares, and even if she eventually develops psoriatic arthritis (as do almost 25% of psoriasis patients), we have terrific treatment for it.

I prescribed topical fluocinonide 0.05% ointment (for bid application) to address her plaque and scheduled a follow-up visit for one month later. Before she left, though, I had to address her most pressing question: “Why did my doctor say this was a fungal infection?” Good question indeed.

TAKE-HOME LEARNING POINTS

• Psoriasis is quite commonly seen in primary care, since it affects almost 3% of the white population.

• Psoriasis is the quintessential papulosquamous disorder, manifesting with salmon-pink scaly patches on extensor extremities, behind ears, and/or in scalp.

• The diagnosis may be corroborated by identification of pits in the fingernails (25% of cases).

• Confirmation of the diagnosis can be made by punch biopsy, which usually shows characteristic changes.

• The overarching learning point: Your differential for “round and scaly” needs more than one item in it.

A 10-year-old girl is seen in dermatology for evaluation of dry skin. She reports few if any symptoms but expresses frustration at her inability to curb the problem; she’s tried several different moisturizers to no avail.

Additional history-taking reveals that she’s had patches of dry skin since age 4; these have appeared and disappeared on her arms, legs, and neck. None has ever been problematic enough to require medical attention.

But recently, a dry patch manifested on the patient’s forearm that her primary care provider diagnosed as fungal infection. Unfortunately, the prescribed antifungal creams (terbinafine and clotrimazole) had no positive impact on the situation.

The patient and her mother deny any family history of skin disease.

EXAMINATION

The scaly, annular plaque on the patient’s extensor left forearm is distinctly salmon-pink, with a tenacious white scale. Elsewhere, there are scaly areas in both post-auricular sulci. There are no significant changes to the skin on the patient’s knees, elbows, or scalp. Several tiny pits are observed on her fingernails.

What is the diagnosis?

DISCUSSION

It would be difficult to imagine a more clear-cut case of psoriasis: not only manifesting with a classic plaque on the left extensor forearm but also with corroboratory stigmata behind the ears and classic fingernail pits. Then why, you might ask, was the diagnosis missed?