User login

Management of wound complications following obstetric anal sphincter injury (OASIS)

During vaginal delivery spontaneous perineal trauma and extension of episiotomy incisions are common. A severe perineal laceration that extends into or through the anal sphincter complex is referred to as an obstetric anal sphincter injury (OASIS) and requires meticulous repair. Following the repair of an OASIS, serious wound complications, including dehiscence and infection, may occur. In Europe the reported rate of OASIS varies widely among countries, with a rate of 0.1% in Romania, possibly due to underreporting, and 4.9% in Iceland.1 In the United States the rates of 3rd- and 4th-degree lacerations were reported to be 3.3% and 1.1%, respectively.2

Risk factors for OASIS include forceps delivery (odds ratio [OR], 5.50), vacuum-assisted delivery (OR, 3.98), and midline episiotomy (OR, 3.82).3 Additional risk factors for severe perineal injury at vaginal delivery include nulliparity (adjusted odds ratio [aOR], 2.58), delivery from a persistent occiput posterior position (aOR, 2.24), and above-average newborn birth weight (aOR, 1.28).4

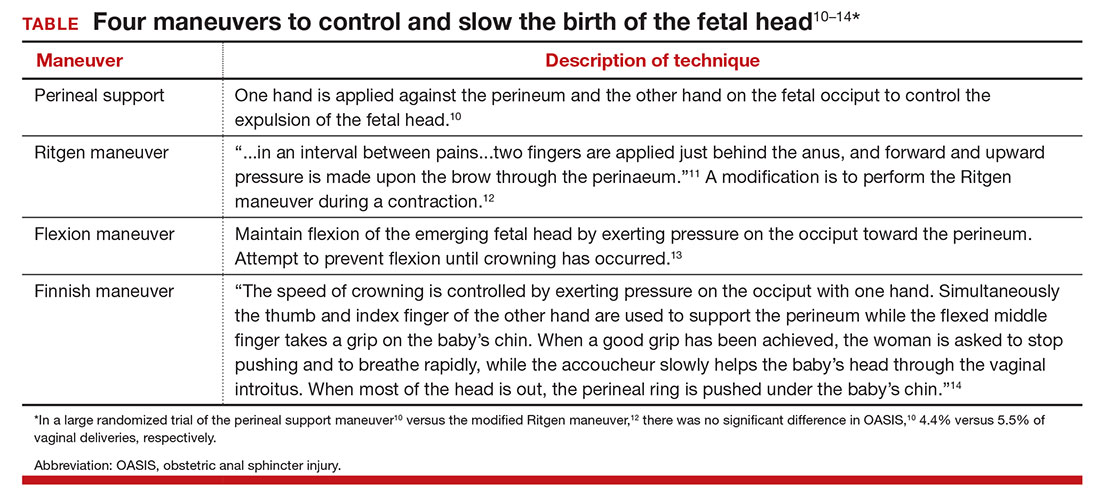

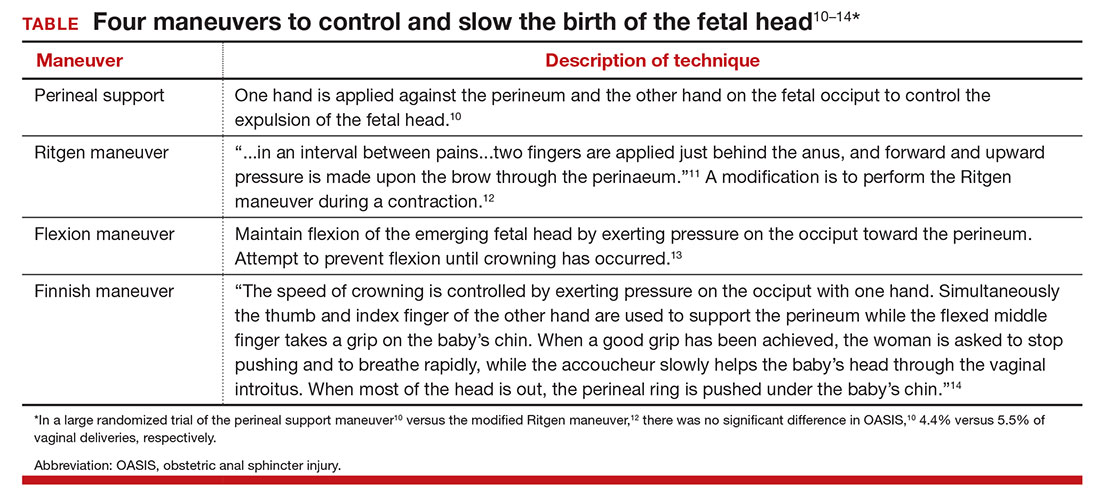

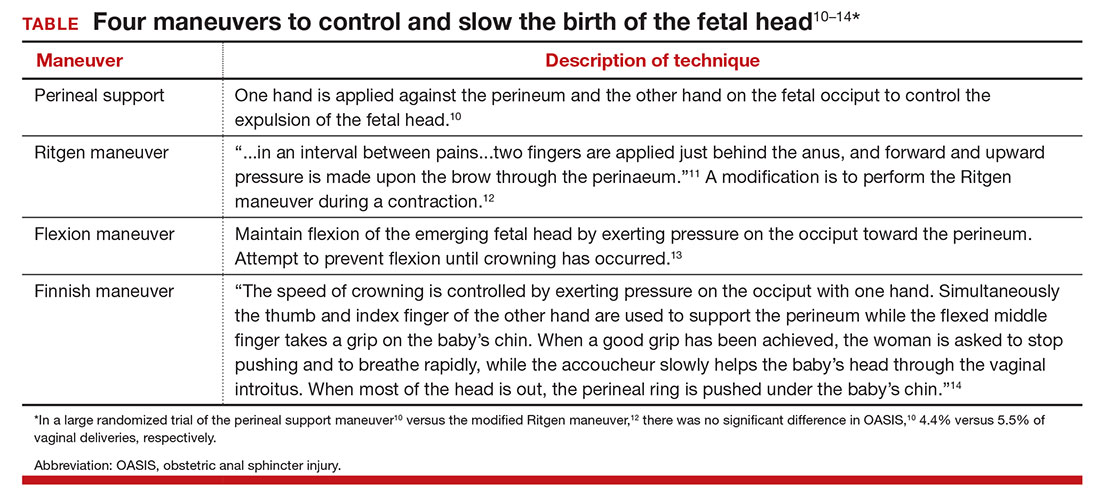

In a meta-analysis of randomized trials, the researchers reported that restrictive use of episiotomy reduced the risk of severe perineal trauma (relative risk [RR], 0.67) but increased the risk of anterior perineal trauma (RR, 1.84).5 The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) recommends that episiotomy should not be a routine practice and is best restricted to use in a limited number of cases where fetal and maternal benefit is likely.6 In addition, ACOG recommends that if episiotomy is indicated, a mediolateral incision is favored over a midline incision. In my practice I perform only mediolateral episiotomy incisions. However, mediolateral episiotomy may be associated with an increased risk of postpartum perineal pain and dyspareunia.7 Use of warm compresses applied to the perineum during the second stage of labor may reduce the risk of 3rd- and 4th-degree lacerations.8 Techniques to ensure that the fetal head and shoulders are birthed in a slow and controlled fashion may decrease the risk of OASIS.9 See the TABLE, “Four maneuvers to control and slow the birth of the fetal head.”10–14

Related article:

Stop performing median episiotomy!

Wound complications following the repair of a 3rd- or 4th-degree laceration are reported to occur in approximately 5% to 10% of cases.15 The most common wound complications are dehiscence, infection, abscess formation, pain, sexual dysfunction, and anal incontinence. Minor wound complications, including superficial epithelial separation, can be managed expectantly. However, major wound complications need intensive treatment.

In one study of 21 women who had a major wound complication following the repair of a 4th-degree laceration, 53% had dehiscence plus infection, 33% had dehiscence alone, and 14% had infection alone.16 Major wound complications present at a mean of 5 days after delivery, with a wide range from 1 to 17 days following delivery.17 In a study of 144 cases of wound breakdown following a perineal laceration repair, the major risk factors for wound breakdown were episiotomy (aOR, 11.1), smoking (aOR, 6.4), midwife repair of laceration (aOR, 4.7), use of chromic suture (aOR, 3.9), and operative vaginal delivery (aOR, 3.4).18 In one study of 66 women with a wound complication following the repair of a 3rd- or 4th-degree laceration, clinical risk factors for a wound complication were cigarette smoking (OR, 4.04), 4th-degree laceration (OR, 1.89), and operative vaginal delivery (OR, 1.76).19 The use of intrapartum antibiotics appears to be protective (OR, 0.29) against wound complications following a major perineal laceration.19

Approach to the patient with a dehisced and infected perineal wound

Historically, wound dehiscence following surgical repair of a perineal injury was managed by allowing the wound to slowly close. This approach adversely impacts the quality of life of the affected woman because it may take weeks for the wound to heal. One small randomized trial17 and multiple case series20–24 report that an active multistep management algorithm permits early closure of the majority of these wounds, thereby accelerating the patient’s full recovery. Delayed primary (within 72 hours postpartum) or early secondary reconstruction (within 14 days of delivery) has been demonstrated to be safe with acceptable long-term functional out-comes.25 The modern approach to the treatment of a patient with an infected wound dehiscence following a severe perineal injury involves 3 steps.

Related article:

It’s time to restrict the use of episiotomy

Step 1. Restore tissue to health

The dehisced wound is cultured and, if infection is present, treatment is initiated with intravenous antibiotics appropriate for an infection with colorectal flora. One antibiotic option includes a cephalosporin (cefotetan 2 g IV every 6 hours) plus metronidazole (500 mg IV every 8 hours).

In the operating room, the wound should be thoroughly assessed, cleansed, and debrided. This step includes irrigation of the wound with a warm fluid, mechanical debridement, and sharp dissection of necrotic tissue. If the wound is infected, removal of stitches that are visible in the open wound is recommended.

Often more than one session of debridement may be needed to obtain wound edges that are free from exudate and show granulation at the wound margins. Between debridement sessions, wet-to-dry dressings are utilized. Two to 10 days of wound care may be needed before an attempt is made to close the wound. The wound is suitable for repair when there is no infected tissue and granulation tissue is present. Some surgeons prefer a mechanical bowel preparation regimen just before surgically closing the open wound. This may prevent early bowel movements and provide for tissue healing after surgery.26 The same preparations recommended for colonoscopy can be considered prior to surgical repair.

Step 2. Surgically close the wound

The wound is surgically closed in the operating room. If in Step 1 the assessment of the wound shows major trauma, assistance from a urogynecologist may be warranted. Surgical management of a perineal wound dehiscence requires a clear understanding of perineal anatomy and the structures contained between the vagina and the anorectum.

Six key structures may be involved in perineal injury: the anorectal mucosa, internal anal sphincter, external anal sphincter, vaginal wall and perineal skin, bulbocavernosus muscle, and transverse perineal muscles. It is important to definitively identify the individual structures that need to be repaired. Careful dissection is then carried out to mobilize these structures for repair. Additional debridement may be necessary to remove excess granulation tissue.

Anorectal mucosa repair. With repair of a 4th-degree perineal wound dehiscence, the apex of the defect in the anorectal mucosa is identified. The defect is repaired beginning at the apex using closely spaced interrupted sutures or a running suture of 3-0 or 4-0 polyglactin 910. Adequate tissue bites that will resist tearing should be taken. If interrupted sutures are used, tying the knots within the anorectal canal prevents them from being located within the healing wound.

Internal anal sphincter repair. After the anorectal mucosa is closed, attention is turned to reapproximation of the internal anal sphincter. The ends of a torn internal anal sphincter are often located lateral to the anorectal mucosa and appear as shiny gray-white fibrous tissue. The surgeon’s gloved index finger can be placed within the anorectal canal to aid in identification of the internal anal sphincter, as it tends to have a rubbery feel. Additionally, while the surgeon’s gloved index finger is in the anorectal canal, the surgeon’s gloved thumb can be used to retract the anorectal mucosa slightly medial and inferior so that adequate bites of the internal anal sphincter can be taken on each side.

Alternatively, Allis clamps canbe placed on the ends of the retracted internal anal sphincter to facilitate repair. Suture selection for repair of the internal anal sphincter can include 3-0 polyglactin 910 or 3-0 monofilament, delayed-absorbable suture such as polydioxanone sulfate (PDS). Some surgeons prefer delayed-absorbable suture (PDS) for this layer given the internal anal sphincter is constantly contracting and relaxing as it samples stool.26 This layer also can be closed with either interrupted sutures or a running suture.

External anal sphincter repair. After the anorectal mucosa and internal anal sphincter defects are reapproximated, attention is turned to the external anal sphincter. Like the internal anal sphincter, the ends of the external anal sphincter are often retracted laterally and must be definitively identified and mobilized in order to ensure an adequate tension-free repair. It is important to include the fascial sheath in the repair of the external anal sphincter.27 Allis clamps can be used to grasp the ends of the torn muscle after they are identified.

We recommend 0 or 2-0 PDS for repair of the external sphincter. Repair can be performed using either an end-to-end or overlapping technique. An end-to-end repair traditionally involves reapproximating the ends of the torn muscle and its overlying fascial sheath using interrupted sutures placed at four quadrants (12:00, 3:00, 6:00, 9:00).

In contrast, in an overlapping repair, the ends of the muscle are brought together with mattress sutures. Suture is passed top down through the medial aspect of the more superior muscle flap and top down through the inferior muscle flap more laterally. The same suture is then passed bottom up through the inferior muscle flap more laterally and finally bottom up through the medial aspect of the more superior muscle flap. Two to four mattress sutures are usually placed. After all sutures are placed, they are tied securely.

An overlapping repair results in a greater amount of tissue contact between the two torn muscle ends. However, adequate mobility of the external anal sphincter is necessary to perform this type of repair.

Vaginal wall and perineal body repair. After the anal sphincters have been repaired, the vaginal wall and remainder of the perineal body are reconstructed using the same techniques involved in a 2nd-degree laceration repair. Care must be taken to retrieve and reapproximate the torn ends of the bulbocavernosus muscles, which are also often retracted laterally and superiorly. After the bulbocavernosus and transverse perineal muscles are brought together in the midline, the posterior vaginal wall should be perpendicular to the perineum.

An alternative to surgical closure of a 2nd-degree dehiscence is the use of vacuum-assisted wound closure. Disadvantages of this approach include difficulty in maintaining a vacuum seal in the perineal region and the risk of wound contamination with feces. In one case report, 3 weeks of vacuum-assisted wound closure resulted in healing of a 10-cm wound dehiscence that occurred 5 days following a forceps-assisted vaginal delivery with a mediolateral episiotomy.28

Step 3. Ensure complete healing of the wound

Superb postoperative wound care helps to ensure a quick return to full recovery. Wound care should include regularly scheduled sitz baths (at least 3 times daily) followed by drying the perineum. It is preferable to provide a liquid diet that avoids frequent bowel movements in the initial 3 postoperative days. Stool softeners and fiber supplementation are recommended when a full diet is resumed. Some surgeons have found mineral oil (1 to 2 tablespoons daily) effective in producing soft stools that are easy to pass.26 Ensuring soft stool consistency is important to help prevent repair breakdown that may occur with passage of hard stools, fecal impaction, and/or straining during defecation.

We recommend follow-up 1 to 2 weeks after surgery to assess wound healing. No vaginal intercourseis permitted until complete healing is achieved.

Use a surgical checklist

All obstetricians and midwives strive to reduce the risk of OASIS at vaginal birth. When OASIS occurs, it is often useful to use a surgical checklist to ensure the execution of all steps in the management of the repair and recovery process.29 It is heartbreaking to see an OASIS repair breakdown in the week following a vaginal delivery. But by following the 3 steps outlined here, the secondary repair is likely to be successful and will quickly return most patients to full health.

Related article:

Develop and use a checklist for 3rd- and 4th-degree perineal lacerations

The authors report no financial relationships relevant to this article.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

- Blondel B, Alexander S, Bjarnadottir RI, et al; Euro-Peristat Scientific Committee. Variations in rates of severe perineal tears and episiotomies in 20 European countries: a study based on routine national data in Euro-Perstat Project. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2016;95(7):746–754.

- Friedman AM, Ananth CV, Predergast E, D’Alton ME, Wright JD. Evaluation of third-degree and fourth-degree laceration rates as quality indicators. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;125(4):927–937.

- Pergialiotis V, Vlachos D, Protopapas A, Pappa K, Vlachos G. Risk factors for severe perineal lacerations during childbirth. Int J Gynecol Obstet. 2014;125(1):6–14.

- Schmitz T, Alberti C, Andriss B, Moutafoff C, Oury JF, Sibony O. Identification of women at high risk for severe perineal lacerations. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2014;182:11–15.

- Carroli G, Mignini L. Episiotomy for vaginal birth. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009;(1):CD000081.

- ACOG Committee on Practice Bulletins—Obstetrics. Practice bulletin no. 165: Prevention and management of obstetric lacerations at vaginal delivery. Obstet Gynecol. 2016;128(1):e1–e15.

- Sartore A, De Seta F, Maso G, Pregazzi R, Grimaldi E, Guaschino S. The effects of mediolateral episiotomy on pelvic floor function after vaginal delivery. Obstet Gynecol. 2004;103(4):669–673.

- Aasheim V, Nilsen AB, Lukasse M, Reinar LM. Perineal techniques during the second stage of labour for reducing perineal trauma. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;(12):CD006672.

- Harvey MA, Pierce M, Alter JE, et al; Society of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists of Canada. Obstetrical anal sphincter injuries (OASIS): prevention, recognition and repair. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2015;37(12):1131–1148.

- Jonsson ER, Elfaghi I, Rydhstrom H, Herbst A. Modified Ritgen’s maneuver for anal sphincter injury at delivery: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2008;112(2 pt 1):212–217.

- Williams JW. Obstetrics: A Text-book for the Use of Students and Practitioners. New York, NY: D Appleton and Co; 1903:288.

- Cunningham FG. The Ritgen maneuver: another sacred cow questioned. Obstet Gynecol. 2008;112(2 pt 1):210–211.

- Myrfield K, Brook C, Creedy D. Reducing perineal trauma: implications of flexion and extension of the fetal head during birth. Midwifery. 1997;13:197–201.

- Ostergaard Poulsen M, Lund Madsen M, Skriver-Moller AC, Overgaard C. Does the Finnish intervention prevent obstetrical anal sphincter injuries? A systematic review of the literature. BMJ Open. 2015;5:e008346.

- Kamel A, Khaled M. Episiotomy and obstetric perineal wound dehiscence: beyond soreness. J Obstet Gynaecol. 2014;34(3):215–217.

- Goldaber KG, Wendel PJ, McIntire DD, Wendel GD Jr. Postpartum perineal morbidity after fourth-degree perineal repair. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1993;168(2):489–493.

- Monberg J, Hammen S. Ruptured episiotomia resutured primarily. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 1987;66(2):163–164.

- Jallad K, Steele SE, Barber MD. Breakdown of perineal laceration repair after vaginal delivery: a case-control study. Female Pelvic Med Reconstr Surg. 2016;22(4):276–279.

- Stock L, Basham E, Gossett DR, Lewicky-Gaupp C. Factors associated with wound complications in women with obstetric anal sphincter injuries (OASIS). Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2013;208(4):327.e1–e8.

- Hauth JC, Gilstrap LC 3rd, Ward SC, Hankins GD. Early repair of an external sphincter ani muscle and rectal mucosal dehiscence. Obstet Gynecol. 1986;67(6):806–809.

- Hankins GD, Hauth JC, Gilstrap LC 3rd, Hammond TL, Yeomans ER, Snyder RR. Early repair of episiotomy dehiscence. Obstet Gynecol. 1990;75(1):48–51.

- Ramin SM, Ramus RM, Little BB, Gilstrap LC 3rd. Early repair of episiotomy dehiscence associated with infection. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1992;167(4 pt 1):1104–1107.

- Arona AJ, Al-Marayati L, Grimes DA, Ballard CA. Early secondary repair of third- and fourth-degree perineal lacerations after outpatient wound preparation. Obstet Gynecol. 1995;86(2):294–296.

- Uygur D, Yesildaglar N, Kis S, Sipahi T. Early repair of episiotomy dehiscence. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol. 2004;44(3):244–246.

- Soerensen MM, Bek KM, Buntzen S, Hojberg KE, Laurberg S. Long-term outcome of delayed primary or early secondary reconstruction of the anal sphincter after obstetrical injury. Dis Colon Rectum. 2008;51(3):312–317.

- Delancey JOL, Berger MB. Surgical approaches to postobstetrical perineal body defects (rectovaginal fistula and chronic third and fourth-degree lacerations). Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2010;53(1):134–144.

- Leeman L, Spearman M, Rogers R. Repair of obstetric perineal lacerations. Am Fam Physician. 2003;68(8):1585–1590.

- Aviki EM, Batalden RP, del Carmen MG, Berkowitz LR. Vacuum-assisted closure for episiotomy dehiscence. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;126(3):530–533.

- Barbieri RL. Develop and use a checklist for 3rd- and 4th-degree perineal lacerations. OBG Manag. 2013;25(8):8–12.

During vaginal delivery spontaneous perineal trauma and extension of episiotomy incisions are common. A severe perineal laceration that extends into or through the anal sphincter complex is referred to as an obstetric anal sphincter injury (OASIS) and requires meticulous repair. Following the repair of an OASIS, serious wound complications, including dehiscence and infection, may occur. In Europe the reported rate of OASIS varies widely among countries, with a rate of 0.1% in Romania, possibly due to underreporting, and 4.9% in Iceland.1 In the United States the rates of 3rd- and 4th-degree lacerations were reported to be 3.3% and 1.1%, respectively.2

Risk factors for OASIS include forceps delivery (odds ratio [OR], 5.50), vacuum-assisted delivery (OR, 3.98), and midline episiotomy (OR, 3.82).3 Additional risk factors for severe perineal injury at vaginal delivery include nulliparity (adjusted odds ratio [aOR], 2.58), delivery from a persistent occiput posterior position (aOR, 2.24), and above-average newborn birth weight (aOR, 1.28).4

In a meta-analysis of randomized trials, the researchers reported that restrictive use of episiotomy reduced the risk of severe perineal trauma (relative risk [RR], 0.67) but increased the risk of anterior perineal trauma (RR, 1.84).5 The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) recommends that episiotomy should not be a routine practice and is best restricted to use in a limited number of cases where fetal and maternal benefit is likely.6 In addition, ACOG recommends that if episiotomy is indicated, a mediolateral incision is favored over a midline incision. In my practice I perform only mediolateral episiotomy incisions. However, mediolateral episiotomy may be associated with an increased risk of postpartum perineal pain and dyspareunia.7 Use of warm compresses applied to the perineum during the second stage of labor may reduce the risk of 3rd- and 4th-degree lacerations.8 Techniques to ensure that the fetal head and shoulders are birthed in a slow and controlled fashion may decrease the risk of OASIS.9 See the TABLE, “Four maneuvers to control and slow the birth of the fetal head.”10–14

Related article:

Stop performing median episiotomy!

Wound complications following the repair of a 3rd- or 4th-degree laceration are reported to occur in approximately 5% to 10% of cases.15 The most common wound complications are dehiscence, infection, abscess formation, pain, sexual dysfunction, and anal incontinence. Minor wound complications, including superficial epithelial separation, can be managed expectantly. However, major wound complications need intensive treatment.

In one study of 21 women who had a major wound complication following the repair of a 4th-degree laceration, 53% had dehiscence plus infection, 33% had dehiscence alone, and 14% had infection alone.16 Major wound complications present at a mean of 5 days after delivery, with a wide range from 1 to 17 days following delivery.17 In a study of 144 cases of wound breakdown following a perineal laceration repair, the major risk factors for wound breakdown were episiotomy (aOR, 11.1), smoking (aOR, 6.4), midwife repair of laceration (aOR, 4.7), use of chromic suture (aOR, 3.9), and operative vaginal delivery (aOR, 3.4).18 In one study of 66 women with a wound complication following the repair of a 3rd- or 4th-degree laceration, clinical risk factors for a wound complication were cigarette smoking (OR, 4.04), 4th-degree laceration (OR, 1.89), and operative vaginal delivery (OR, 1.76).19 The use of intrapartum antibiotics appears to be protective (OR, 0.29) against wound complications following a major perineal laceration.19

Approach to the patient with a dehisced and infected perineal wound

Historically, wound dehiscence following surgical repair of a perineal injury was managed by allowing the wound to slowly close. This approach adversely impacts the quality of life of the affected woman because it may take weeks for the wound to heal. One small randomized trial17 and multiple case series20–24 report that an active multistep management algorithm permits early closure of the majority of these wounds, thereby accelerating the patient’s full recovery. Delayed primary (within 72 hours postpartum) or early secondary reconstruction (within 14 days of delivery) has been demonstrated to be safe with acceptable long-term functional out-comes.25 The modern approach to the treatment of a patient with an infected wound dehiscence following a severe perineal injury involves 3 steps.

Related article:

It’s time to restrict the use of episiotomy

Step 1. Restore tissue to health

The dehisced wound is cultured and, if infection is present, treatment is initiated with intravenous antibiotics appropriate for an infection with colorectal flora. One antibiotic option includes a cephalosporin (cefotetan 2 g IV every 6 hours) plus metronidazole (500 mg IV every 8 hours).

In the operating room, the wound should be thoroughly assessed, cleansed, and debrided. This step includes irrigation of the wound with a warm fluid, mechanical debridement, and sharp dissection of necrotic tissue. If the wound is infected, removal of stitches that are visible in the open wound is recommended.

Often more than one session of debridement may be needed to obtain wound edges that are free from exudate and show granulation at the wound margins. Between debridement sessions, wet-to-dry dressings are utilized. Two to 10 days of wound care may be needed before an attempt is made to close the wound. The wound is suitable for repair when there is no infected tissue and granulation tissue is present. Some surgeons prefer a mechanical bowel preparation regimen just before surgically closing the open wound. This may prevent early bowel movements and provide for tissue healing after surgery.26 The same preparations recommended for colonoscopy can be considered prior to surgical repair.

Step 2. Surgically close the wound

The wound is surgically closed in the operating room. If in Step 1 the assessment of the wound shows major trauma, assistance from a urogynecologist may be warranted. Surgical management of a perineal wound dehiscence requires a clear understanding of perineal anatomy and the structures contained between the vagina and the anorectum.

Six key structures may be involved in perineal injury: the anorectal mucosa, internal anal sphincter, external anal sphincter, vaginal wall and perineal skin, bulbocavernosus muscle, and transverse perineal muscles. It is important to definitively identify the individual structures that need to be repaired. Careful dissection is then carried out to mobilize these structures for repair. Additional debridement may be necessary to remove excess granulation tissue.

Anorectal mucosa repair. With repair of a 4th-degree perineal wound dehiscence, the apex of the defect in the anorectal mucosa is identified. The defect is repaired beginning at the apex using closely spaced interrupted sutures or a running suture of 3-0 or 4-0 polyglactin 910. Adequate tissue bites that will resist tearing should be taken. If interrupted sutures are used, tying the knots within the anorectal canal prevents them from being located within the healing wound.

Internal anal sphincter repair. After the anorectal mucosa is closed, attention is turned to reapproximation of the internal anal sphincter. The ends of a torn internal anal sphincter are often located lateral to the anorectal mucosa and appear as shiny gray-white fibrous tissue. The surgeon’s gloved index finger can be placed within the anorectal canal to aid in identification of the internal anal sphincter, as it tends to have a rubbery feel. Additionally, while the surgeon’s gloved index finger is in the anorectal canal, the surgeon’s gloved thumb can be used to retract the anorectal mucosa slightly medial and inferior so that adequate bites of the internal anal sphincter can be taken on each side.

Alternatively, Allis clamps canbe placed on the ends of the retracted internal anal sphincter to facilitate repair. Suture selection for repair of the internal anal sphincter can include 3-0 polyglactin 910 or 3-0 monofilament, delayed-absorbable suture such as polydioxanone sulfate (PDS). Some surgeons prefer delayed-absorbable suture (PDS) for this layer given the internal anal sphincter is constantly contracting and relaxing as it samples stool.26 This layer also can be closed with either interrupted sutures or a running suture.

External anal sphincter repair. After the anorectal mucosa and internal anal sphincter defects are reapproximated, attention is turned to the external anal sphincter. Like the internal anal sphincter, the ends of the external anal sphincter are often retracted laterally and must be definitively identified and mobilized in order to ensure an adequate tension-free repair. It is important to include the fascial sheath in the repair of the external anal sphincter.27 Allis clamps can be used to grasp the ends of the torn muscle after they are identified.

We recommend 0 or 2-0 PDS for repair of the external sphincter. Repair can be performed using either an end-to-end or overlapping technique. An end-to-end repair traditionally involves reapproximating the ends of the torn muscle and its overlying fascial sheath using interrupted sutures placed at four quadrants (12:00, 3:00, 6:00, 9:00).

In contrast, in an overlapping repair, the ends of the muscle are brought together with mattress sutures. Suture is passed top down through the medial aspect of the more superior muscle flap and top down through the inferior muscle flap more laterally. The same suture is then passed bottom up through the inferior muscle flap more laterally and finally bottom up through the medial aspect of the more superior muscle flap. Two to four mattress sutures are usually placed. After all sutures are placed, they are tied securely.

An overlapping repair results in a greater amount of tissue contact between the two torn muscle ends. However, adequate mobility of the external anal sphincter is necessary to perform this type of repair.

Vaginal wall and perineal body repair. After the anal sphincters have been repaired, the vaginal wall and remainder of the perineal body are reconstructed using the same techniques involved in a 2nd-degree laceration repair. Care must be taken to retrieve and reapproximate the torn ends of the bulbocavernosus muscles, which are also often retracted laterally and superiorly. After the bulbocavernosus and transverse perineal muscles are brought together in the midline, the posterior vaginal wall should be perpendicular to the perineum.

An alternative to surgical closure of a 2nd-degree dehiscence is the use of vacuum-assisted wound closure. Disadvantages of this approach include difficulty in maintaining a vacuum seal in the perineal region and the risk of wound contamination with feces. In one case report, 3 weeks of vacuum-assisted wound closure resulted in healing of a 10-cm wound dehiscence that occurred 5 days following a forceps-assisted vaginal delivery with a mediolateral episiotomy.28

Step 3. Ensure complete healing of the wound

Superb postoperative wound care helps to ensure a quick return to full recovery. Wound care should include regularly scheduled sitz baths (at least 3 times daily) followed by drying the perineum. It is preferable to provide a liquid diet that avoids frequent bowel movements in the initial 3 postoperative days. Stool softeners and fiber supplementation are recommended when a full diet is resumed. Some surgeons have found mineral oil (1 to 2 tablespoons daily) effective in producing soft stools that are easy to pass.26 Ensuring soft stool consistency is important to help prevent repair breakdown that may occur with passage of hard stools, fecal impaction, and/or straining during defecation.

We recommend follow-up 1 to 2 weeks after surgery to assess wound healing. No vaginal intercourseis permitted until complete healing is achieved.

Use a surgical checklist

All obstetricians and midwives strive to reduce the risk of OASIS at vaginal birth. When OASIS occurs, it is often useful to use a surgical checklist to ensure the execution of all steps in the management of the repair and recovery process.29 It is heartbreaking to see an OASIS repair breakdown in the week following a vaginal delivery. But by following the 3 steps outlined here, the secondary repair is likely to be successful and will quickly return most patients to full health.

Related article:

Develop and use a checklist for 3rd- and 4th-degree perineal lacerations

The authors report no financial relationships relevant to this article.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

During vaginal delivery spontaneous perineal trauma and extension of episiotomy incisions are common. A severe perineal laceration that extends into or through the anal sphincter complex is referred to as an obstetric anal sphincter injury (OASIS) and requires meticulous repair. Following the repair of an OASIS, serious wound complications, including dehiscence and infection, may occur. In Europe the reported rate of OASIS varies widely among countries, with a rate of 0.1% in Romania, possibly due to underreporting, and 4.9% in Iceland.1 In the United States the rates of 3rd- and 4th-degree lacerations were reported to be 3.3% and 1.1%, respectively.2

Risk factors for OASIS include forceps delivery (odds ratio [OR], 5.50), vacuum-assisted delivery (OR, 3.98), and midline episiotomy (OR, 3.82).3 Additional risk factors for severe perineal injury at vaginal delivery include nulliparity (adjusted odds ratio [aOR], 2.58), delivery from a persistent occiput posterior position (aOR, 2.24), and above-average newborn birth weight (aOR, 1.28).4

In a meta-analysis of randomized trials, the researchers reported that restrictive use of episiotomy reduced the risk of severe perineal trauma (relative risk [RR], 0.67) but increased the risk of anterior perineal trauma (RR, 1.84).5 The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) recommends that episiotomy should not be a routine practice and is best restricted to use in a limited number of cases where fetal and maternal benefit is likely.6 In addition, ACOG recommends that if episiotomy is indicated, a mediolateral incision is favored over a midline incision. In my practice I perform only mediolateral episiotomy incisions. However, mediolateral episiotomy may be associated with an increased risk of postpartum perineal pain and dyspareunia.7 Use of warm compresses applied to the perineum during the second stage of labor may reduce the risk of 3rd- and 4th-degree lacerations.8 Techniques to ensure that the fetal head and shoulders are birthed in a slow and controlled fashion may decrease the risk of OASIS.9 See the TABLE, “Four maneuvers to control and slow the birth of the fetal head.”10–14

Related article:

Stop performing median episiotomy!

Wound complications following the repair of a 3rd- or 4th-degree laceration are reported to occur in approximately 5% to 10% of cases.15 The most common wound complications are dehiscence, infection, abscess formation, pain, sexual dysfunction, and anal incontinence. Minor wound complications, including superficial epithelial separation, can be managed expectantly. However, major wound complications need intensive treatment.

In one study of 21 women who had a major wound complication following the repair of a 4th-degree laceration, 53% had dehiscence plus infection, 33% had dehiscence alone, and 14% had infection alone.16 Major wound complications present at a mean of 5 days after delivery, with a wide range from 1 to 17 days following delivery.17 In a study of 144 cases of wound breakdown following a perineal laceration repair, the major risk factors for wound breakdown were episiotomy (aOR, 11.1), smoking (aOR, 6.4), midwife repair of laceration (aOR, 4.7), use of chromic suture (aOR, 3.9), and operative vaginal delivery (aOR, 3.4).18 In one study of 66 women with a wound complication following the repair of a 3rd- or 4th-degree laceration, clinical risk factors for a wound complication were cigarette smoking (OR, 4.04), 4th-degree laceration (OR, 1.89), and operative vaginal delivery (OR, 1.76).19 The use of intrapartum antibiotics appears to be protective (OR, 0.29) against wound complications following a major perineal laceration.19

Approach to the patient with a dehisced and infected perineal wound

Historically, wound dehiscence following surgical repair of a perineal injury was managed by allowing the wound to slowly close. This approach adversely impacts the quality of life of the affected woman because it may take weeks for the wound to heal. One small randomized trial17 and multiple case series20–24 report that an active multistep management algorithm permits early closure of the majority of these wounds, thereby accelerating the patient’s full recovery. Delayed primary (within 72 hours postpartum) or early secondary reconstruction (within 14 days of delivery) has been demonstrated to be safe with acceptable long-term functional out-comes.25 The modern approach to the treatment of a patient with an infected wound dehiscence following a severe perineal injury involves 3 steps.

Related article:

It’s time to restrict the use of episiotomy

Step 1. Restore tissue to health

The dehisced wound is cultured and, if infection is present, treatment is initiated with intravenous antibiotics appropriate for an infection with colorectal flora. One antibiotic option includes a cephalosporin (cefotetan 2 g IV every 6 hours) plus metronidazole (500 mg IV every 8 hours).

In the operating room, the wound should be thoroughly assessed, cleansed, and debrided. This step includes irrigation of the wound with a warm fluid, mechanical debridement, and sharp dissection of necrotic tissue. If the wound is infected, removal of stitches that are visible in the open wound is recommended.

Often more than one session of debridement may be needed to obtain wound edges that are free from exudate and show granulation at the wound margins. Between debridement sessions, wet-to-dry dressings are utilized. Two to 10 days of wound care may be needed before an attempt is made to close the wound. The wound is suitable for repair when there is no infected tissue and granulation tissue is present. Some surgeons prefer a mechanical bowel preparation regimen just before surgically closing the open wound. This may prevent early bowel movements and provide for tissue healing after surgery.26 The same preparations recommended for colonoscopy can be considered prior to surgical repair.

Step 2. Surgically close the wound

The wound is surgically closed in the operating room. If in Step 1 the assessment of the wound shows major trauma, assistance from a urogynecologist may be warranted. Surgical management of a perineal wound dehiscence requires a clear understanding of perineal anatomy and the structures contained between the vagina and the anorectum.

Six key structures may be involved in perineal injury: the anorectal mucosa, internal anal sphincter, external anal sphincter, vaginal wall and perineal skin, bulbocavernosus muscle, and transverse perineal muscles. It is important to definitively identify the individual structures that need to be repaired. Careful dissection is then carried out to mobilize these structures for repair. Additional debridement may be necessary to remove excess granulation tissue.

Anorectal mucosa repair. With repair of a 4th-degree perineal wound dehiscence, the apex of the defect in the anorectal mucosa is identified. The defect is repaired beginning at the apex using closely spaced interrupted sutures or a running suture of 3-0 or 4-0 polyglactin 910. Adequate tissue bites that will resist tearing should be taken. If interrupted sutures are used, tying the knots within the anorectal canal prevents them from being located within the healing wound.

Internal anal sphincter repair. After the anorectal mucosa is closed, attention is turned to reapproximation of the internal anal sphincter. The ends of a torn internal anal sphincter are often located lateral to the anorectal mucosa and appear as shiny gray-white fibrous tissue. The surgeon’s gloved index finger can be placed within the anorectal canal to aid in identification of the internal anal sphincter, as it tends to have a rubbery feel. Additionally, while the surgeon’s gloved index finger is in the anorectal canal, the surgeon’s gloved thumb can be used to retract the anorectal mucosa slightly medial and inferior so that adequate bites of the internal anal sphincter can be taken on each side.

Alternatively, Allis clamps canbe placed on the ends of the retracted internal anal sphincter to facilitate repair. Suture selection for repair of the internal anal sphincter can include 3-0 polyglactin 910 or 3-0 monofilament, delayed-absorbable suture such as polydioxanone sulfate (PDS). Some surgeons prefer delayed-absorbable suture (PDS) for this layer given the internal anal sphincter is constantly contracting and relaxing as it samples stool.26 This layer also can be closed with either interrupted sutures or a running suture.

External anal sphincter repair. After the anorectal mucosa and internal anal sphincter defects are reapproximated, attention is turned to the external anal sphincter. Like the internal anal sphincter, the ends of the external anal sphincter are often retracted laterally and must be definitively identified and mobilized in order to ensure an adequate tension-free repair. It is important to include the fascial sheath in the repair of the external anal sphincter.27 Allis clamps can be used to grasp the ends of the torn muscle after they are identified.

We recommend 0 or 2-0 PDS for repair of the external sphincter. Repair can be performed using either an end-to-end or overlapping technique. An end-to-end repair traditionally involves reapproximating the ends of the torn muscle and its overlying fascial sheath using interrupted sutures placed at four quadrants (12:00, 3:00, 6:00, 9:00).

In contrast, in an overlapping repair, the ends of the muscle are brought together with mattress sutures. Suture is passed top down through the medial aspect of the more superior muscle flap and top down through the inferior muscle flap more laterally. The same suture is then passed bottom up through the inferior muscle flap more laterally and finally bottom up through the medial aspect of the more superior muscle flap. Two to four mattress sutures are usually placed. After all sutures are placed, they are tied securely.

An overlapping repair results in a greater amount of tissue contact between the two torn muscle ends. However, adequate mobility of the external anal sphincter is necessary to perform this type of repair.

Vaginal wall and perineal body repair. After the anal sphincters have been repaired, the vaginal wall and remainder of the perineal body are reconstructed using the same techniques involved in a 2nd-degree laceration repair. Care must be taken to retrieve and reapproximate the torn ends of the bulbocavernosus muscles, which are also often retracted laterally and superiorly. After the bulbocavernosus and transverse perineal muscles are brought together in the midline, the posterior vaginal wall should be perpendicular to the perineum.

An alternative to surgical closure of a 2nd-degree dehiscence is the use of vacuum-assisted wound closure. Disadvantages of this approach include difficulty in maintaining a vacuum seal in the perineal region and the risk of wound contamination with feces. In one case report, 3 weeks of vacuum-assisted wound closure resulted in healing of a 10-cm wound dehiscence that occurred 5 days following a forceps-assisted vaginal delivery with a mediolateral episiotomy.28

Step 3. Ensure complete healing of the wound

Superb postoperative wound care helps to ensure a quick return to full recovery. Wound care should include regularly scheduled sitz baths (at least 3 times daily) followed by drying the perineum. It is preferable to provide a liquid diet that avoids frequent bowel movements in the initial 3 postoperative days. Stool softeners and fiber supplementation are recommended when a full diet is resumed. Some surgeons have found mineral oil (1 to 2 tablespoons daily) effective in producing soft stools that are easy to pass.26 Ensuring soft stool consistency is important to help prevent repair breakdown that may occur with passage of hard stools, fecal impaction, and/or straining during defecation.

We recommend follow-up 1 to 2 weeks after surgery to assess wound healing. No vaginal intercourseis permitted until complete healing is achieved.

Use a surgical checklist

All obstetricians and midwives strive to reduce the risk of OASIS at vaginal birth. When OASIS occurs, it is often useful to use a surgical checklist to ensure the execution of all steps in the management of the repair and recovery process.29 It is heartbreaking to see an OASIS repair breakdown in the week following a vaginal delivery. But by following the 3 steps outlined here, the secondary repair is likely to be successful and will quickly return most patients to full health.

Related article:

Develop and use a checklist for 3rd- and 4th-degree perineal lacerations

The authors report no financial relationships relevant to this article.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

- Blondel B, Alexander S, Bjarnadottir RI, et al; Euro-Peristat Scientific Committee. Variations in rates of severe perineal tears and episiotomies in 20 European countries: a study based on routine national data in Euro-Perstat Project. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2016;95(7):746–754.

- Friedman AM, Ananth CV, Predergast E, D’Alton ME, Wright JD. Evaluation of third-degree and fourth-degree laceration rates as quality indicators. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;125(4):927–937.

- Pergialiotis V, Vlachos D, Protopapas A, Pappa K, Vlachos G. Risk factors for severe perineal lacerations during childbirth. Int J Gynecol Obstet. 2014;125(1):6–14.

- Schmitz T, Alberti C, Andriss B, Moutafoff C, Oury JF, Sibony O. Identification of women at high risk for severe perineal lacerations. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2014;182:11–15.

- Carroli G, Mignini L. Episiotomy for vaginal birth. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009;(1):CD000081.

- ACOG Committee on Practice Bulletins—Obstetrics. Practice bulletin no. 165: Prevention and management of obstetric lacerations at vaginal delivery. Obstet Gynecol. 2016;128(1):e1–e15.

- Sartore A, De Seta F, Maso G, Pregazzi R, Grimaldi E, Guaschino S. The effects of mediolateral episiotomy on pelvic floor function after vaginal delivery. Obstet Gynecol. 2004;103(4):669–673.

- Aasheim V, Nilsen AB, Lukasse M, Reinar LM. Perineal techniques during the second stage of labour for reducing perineal trauma. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;(12):CD006672.

- Harvey MA, Pierce M, Alter JE, et al; Society of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists of Canada. Obstetrical anal sphincter injuries (OASIS): prevention, recognition and repair. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2015;37(12):1131–1148.

- Jonsson ER, Elfaghi I, Rydhstrom H, Herbst A. Modified Ritgen’s maneuver for anal sphincter injury at delivery: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2008;112(2 pt 1):212–217.

- Williams JW. Obstetrics: A Text-book for the Use of Students and Practitioners. New York, NY: D Appleton and Co; 1903:288.

- Cunningham FG. The Ritgen maneuver: another sacred cow questioned. Obstet Gynecol. 2008;112(2 pt 1):210–211.

- Myrfield K, Brook C, Creedy D. Reducing perineal trauma: implications of flexion and extension of the fetal head during birth. Midwifery. 1997;13:197–201.

- Ostergaard Poulsen M, Lund Madsen M, Skriver-Moller AC, Overgaard C. Does the Finnish intervention prevent obstetrical anal sphincter injuries? A systematic review of the literature. BMJ Open. 2015;5:e008346.

- Kamel A, Khaled M. Episiotomy and obstetric perineal wound dehiscence: beyond soreness. J Obstet Gynaecol. 2014;34(3):215–217.

- Goldaber KG, Wendel PJ, McIntire DD, Wendel GD Jr. Postpartum perineal morbidity after fourth-degree perineal repair. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1993;168(2):489–493.

- Monberg J, Hammen S. Ruptured episiotomia resutured primarily. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 1987;66(2):163–164.

- Jallad K, Steele SE, Barber MD. Breakdown of perineal laceration repair after vaginal delivery: a case-control study. Female Pelvic Med Reconstr Surg. 2016;22(4):276–279.

- Stock L, Basham E, Gossett DR, Lewicky-Gaupp C. Factors associated with wound complications in women with obstetric anal sphincter injuries (OASIS). Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2013;208(4):327.e1–e8.

- Hauth JC, Gilstrap LC 3rd, Ward SC, Hankins GD. Early repair of an external sphincter ani muscle and rectal mucosal dehiscence. Obstet Gynecol. 1986;67(6):806–809.

- Hankins GD, Hauth JC, Gilstrap LC 3rd, Hammond TL, Yeomans ER, Snyder RR. Early repair of episiotomy dehiscence. Obstet Gynecol. 1990;75(1):48–51.

- Ramin SM, Ramus RM, Little BB, Gilstrap LC 3rd. Early repair of episiotomy dehiscence associated with infection. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1992;167(4 pt 1):1104–1107.

- Arona AJ, Al-Marayati L, Grimes DA, Ballard CA. Early secondary repair of third- and fourth-degree perineal lacerations after outpatient wound preparation. Obstet Gynecol. 1995;86(2):294–296.

- Uygur D, Yesildaglar N, Kis S, Sipahi T. Early repair of episiotomy dehiscence. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol. 2004;44(3):244–246.

- Soerensen MM, Bek KM, Buntzen S, Hojberg KE, Laurberg S. Long-term outcome of delayed primary or early secondary reconstruction of the anal sphincter after obstetrical injury. Dis Colon Rectum. 2008;51(3):312–317.

- Delancey JOL, Berger MB. Surgical approaches to postobstetrical perineal body defects (rectovaginal fistula and chronic third and fourth-degree lacerations). Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2010;53(1):134–144.

- Leeman L, Spearman M, Rogers R. Repair of obstetric perineal lacerations. Am Fam Physician. 2003;68(8):1585–1590.

- Aviki EM, Batalden RP, del Carmen MG, Berkowitz LR. Vacuum-assisted closure for episiotomy dehiscence. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;126(3):530–533.

- Barbieri RL. Develop and use a checklist for 3rd- and 4th-degree perineal lacerations. OBG Manag. 2013;25(8):8–12.

- Blondel B, Alexander S, Bjarnadottir RI, et al; Euro-Peristat Scientific Committee. Variations in rates of severe perineal tears and episiotomies in 20 European countries: a study based on routine national data in Euro-Perstat Project. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2016;95(7):746–754.

- Friedman AM, Ananth CV, Predergast E, D’Alton ME, Wright JD. Evaluation of third-degree and fourth-degree laceration rates as quality indicators. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;125(4):927–937.

- Pergialiotis V, Vlachos D, Protopapas A, Pappa K, Vlachos G. Risk factors for severe perineal lacerations during childbirth. Int J Gynecol Obstet. 2014;125(1):6–14.

- Schmitz T, Alberti C, Andriss B, Moutafoff C, Oury JF, Sibony O. Identification of women at high risk for severe perineal lacerations. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2014;182:11–15.

- Carroli G, Mignini L. Episiotomy for vaginal birth. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009;(1):CD000081.

- ACOG Committee on Practice Bulletins—Obstetrics. Practice bulletin no. 165: Prevention and management of obstetric lacerations at vaginal delivery. Obstet Gynecol. 2016;128(1):e1–e15.

- Sartore A, De Seta F, Maso G, Pregazzi R, Grimaldi E, Guaschino S. The effects of mediolateral episiotomy on pelvic floor function after vaginal delivery. Obstet Gynecol. 2004;103(4):669–673.

- Aasheim V, Nilsen AB, Lukasse M, Reinar LM. Perineal techniques during the second stage of labour for reducing perineal trauma. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;(12):CD006672.

- Harvey MA, Pierce M, Alter JE, et al; Society of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists of Canada. Obstetrical anal sphincter injuries (OASIS): prevention, recognition and repair. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2015;37(12):1131–1148.

- Jonsson ER, Elfaghi I, Rydhstrom H, Herbst A. Modified Ritgen’s maneuver for anal sphincter injury at delivery: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2008;112(2 pt 1):212–217.

- Williams JW. Obstetrics: A Text-book for the Use of Students and Practitioners. New York, NY: D Appleton and Co; 1903:288.

- Cunningham FG. The Ritgen maneuver: another sacred cow questioned. Obstet Gynecol. 2008;112(2 pt 1):210–211.

- Myrfield K, Brook C, Creedy D. Reducing perineal trauma: implications of flexion and extension of the fetal head during birth. Midwifery. 1997;13:197–201.

- Ostergaard Poulsen M, Lund Madsen M, Skriver-Moller AC, Overgaard C. Does the Finnish intervention prevent obstetrical anal sphincter injuries? A systematic review of the literature. BMJ Open. 2015;5:e008346.

- Kamel A, Khaled M. Episiotomy and obstetric perineal wound dehiscence: beyond soreness. J Obstet Gynaecol. 2014;34(3):215–217.

- Goldaber KG, Wendel PJ, McIntire DD, Wendel GD Jr. Postpartum perineal morbidity after fourth-degree perineal repair. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1993;168(2):489–493.

- Monberg J, Hammen S. Ruptured episiotomia resutured primarily. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 1987;66(2):163–164.

- Jallad K, Steele SE, Barber MD. Breakdown of perineal laceration repair after vaginal delivery: a case-control study. Female Pelvic Med Reconstr Surg. 2016;22(4):276–279.

- Stock L, Basham E, Gossett DR, Lewicky-Gaupp C. Factors associated with wound complications in women with obstetric anal sphincter injuries (OASIS). Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2013;208(4):327.e1–e8.

- Hauth JC, Gilstrap LC 3rd, Ward SC, Hankins GD. Early repair of an external sphincter ani muscle and rectal mucosal dehiscence. Obstet Gynecol. 1986;67(6):806–809.

- Hankins GD, Hauth JC, Gilstrap LC 3rd, Hammond TL, Yeomans ER, Snyder RR. Early repair of episiotomy dehiscence. Obstet Gynecol. 1990;75(1):48–51.

- Ramin SM, Ramus RM, Little BB, Gilstrap LC 3rd. Early repair of episiotomy dehiscence associated with infection. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1992;167(4 pt 1):1104–1107.

- Arona AJ, Al-Marayati L, Grimes DA, Ballard CA. Early secondary repair of third- and fourth-degree perineal lacerations after outpatient wound preparation. Obstet Gynecol. 1995;86(2):294–296.

- Uygur D, Yesildaglar N, Kis S, Sipahi T. Early repair of episiotomy dehiscence. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol. 2004;44(3):244–246.

- Soerensen MM, Bek KM, Buntzen S, Hojberg KE, Laurberg S. Long-term outcome of delayed primary or early secondary reconstruction of the anal sphincter after obstetrical injury. Dis Colon Rectum. 2008;51(3):312–317.

- Delancey JOL, Berger MB. Surgical approaches to postobstetrical perineal body defects (rectovaginal fistula and chronic third and fourth-degree lacerations). Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2010;53(1):134–144.

- Leeman L, Spearman M, Rogers R. Repair of obstetric perineal lacerations. Am Fam Physician. 2003;68(8):1585–1590.

- Aviki EM, Batalden RP, del Carmen MG, Berkowitz LR. Vacuum-assisted closure for episiotomy dehiscence. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;126(3):530–533.

- Barbieri RL. Develop and use a checklist for 3rd- and 4th-degree perineal lacerations. OBG Manag. 2013;25(8):8–12.