User login

A paranoid, violent teenager

Discuss this article at www.facebook.com/CurrentPsychiatry

CASE: Sleepless and paranoid

Ms. V, age 16, is referred to our psychiatric hospital from a juvenile detention center after she is charged with killing her sister with a hammer. She reports paranoid delusions, including believing that her sister was poisoning her food. Ms. V’s troubling behavior increased in the 6 months before the murder. She began to ask her mother to smell her food for possible poison. Her school grades dropped and she experienced decreased sleep and appetite. According to her mother, Ms. V’s insomnia worsened recently because of her paranoid thinking, which was evident when she noticed that her daughter slept with a hammer. Ms. V stopped socializing with her peers and no longer went to the gym.

Ms. V’s mother describes her daughter’s negative symptoms as consisting of social isolation and a flat affect. There was no evidence of auditory or visual hallucinations. After noticing the change in her daughter’s behavior, Ms. V’s mother attempted to schedule an appointment with a mental health professional, but there was a 2-month waiting list.

Ms. V cleaned her room before the murder, which was uncharacteristic of her routine behavior. On the day of the murder, Ms. V approached her sister while she was sleeping on the sofa and struck her on the head several times with a hammer. After the sister died, neighbors spotted Ms. V washing blood off her hands in their backyard with a sprinkler. Soaked in blood, she approached one of the neighbors and said that someone had been killed in the house. The neighbors called the police and Ms. V was arrested. She did not express remorse. She did not exhibit physical aggression toward others before the murder. Ms. V’s sense of entitlement and grandiosity persisted after the murder.

The authors’ observations

Paranoid delusions are fixed false beliefs with severe fears of others that may impair functioning at school or work, in personal relationships, and in other social dimensions. Paranoid thinking can have diverse presentations, ranging from social concerns such as fear of rejection to severe threat perceptions of people trying to cause substantial physical harm.1 Paranoid thoughts can be a result of misinterpretation of language, a personality disorder, anxiety, or psychosis.

Feelings of low self-esteem2 and anger1 may develop in a patient experiencing paranoid ideations. When anger begins to escalate, it may erupt into violent behavior. In Ms. V’s case, her paranoid ideations increased until she killed her younger sister. Ms. V’s case is similar to a mass shooting near Tucson, AZ on January 8, 2011 in that it possibly could have been prevented with earlier psychiatric intervention (Box).3-6

On January 8, 2011, a mass shooting occurred near Tucson, AZ that killed 6 and wounded 13. The suspect, 22-year-old Jared Lee Loughner, refused to cooperate with authorities by invoking his right to remain silent.3 Although the motives behind this crime remain undisclosed, mental illness appears to be a contributing factor.

Reports indicate that Mr. Loughner was abusing drugs and those close to him had noticed personality changes.4,5 The college he was attending advised Mr. Loughner to undergo a mental health evaluation, but he refused and dropped out of school.4,5 While in custody after the shooting, Mr. Loughner was diagnosed with paranoid schizophrenia, deemed incompetent to stand trial, and ordered to receive psychiatric treatment.6

This tragic mass shooting and similar incidents have led to questions regarding the adequacy of the mental health care infrastructure in United States. Experts suggest that this tragedy could have been prevented with more aggressive psychiatric prevention and intervention. Critical analysis of similar recent cases and expert opinions are needed to address this problem effectively.

EVALUATION: Remorseless

At admission, Ms. V’s affect is restricted and, at times, inappropriate. She is guarded about discussing the homicide but describes paranoid thoughts about her sister poisoning her. She is eager to learn if the police had found poison in her food. Her speech is soft with good articulation. Based on her presentation, her intelligence is average. She shows no evidence of remorse and is preoccupied with her sister poisoning her.

The Rorschach Inkblot Technique reveals positive evidence for a severe thought disorder. Ms. V’s thinking seems regressed. Ms. V’s medical workup, including MRI, electroencephalogram, and laboratory tests, are all within normal limits.

In the 5th grade, Ms. V’s primary care provider prescribed amphetamine and dextroamphetamine for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, but she discontinued the drug after 1 year. Ms. V has never been hospitalized for psychiatric illness. She had no chronic medical conditions and no developmental delays.

Ms. V also has a history of periodic temper problems characterized by verbal aggression such as threatening the assistant principal at her school, and throwing her cellphone at her mother a few weeks before the murder, but no other aggressive episodes. Ms. V’s history does not suggest conduct disorder. She has no history of suicidal ideation or suicide attempts. Ms. V has used alcohol since age 15, but her mother reports that she was not a heavy or frequent user. Her last reported alcohol use was 10 days before the murder. A maternal uncle had been diagnosed with schizophrenia.

Before the murder, Ms. V lived with her sister and mother. Her parents were divorced. At age 9, Ms. V was sexually abused by a soccer coach; however, she denied symptoms of posttraumatic stress disorder related to the sexual abuse. She had no criminal history before the murder.

The authors’ observations

Based on Ms. V’s presentation and history, schizophrenia, paranoid type seems to be the most likely diagnosis because of her negative symptoms, including affective flattening, positive family history for schizophrenia, and paranoid delusions leading to dysfunction (Table).7 Delusional disorder seems less likely because Ms. V is young and has negative symptoms. Because she is generally healthy and her medical workup is negative, psychotic disorder due to a general medical condition is ruled out. She does not appear to be over-reporting, malingering, or exaggerating symptoms. In the context of psychosis, adolescent psychopathy does not seem likely even though there is evidence of grandiosity and a lack of remorse.

Table

DSM-IV-TR criteria for schizophrenia

A. Characteristic symptoms: ≥2 of the following, each present for a significant portion of time during a 1-month period:

|

| B. Social/occupational dysfunction: For a significant portion of the time since the onset of the disturbance, ≥1 major areas of functioning such as work, interpersonal relations, or self-care are markedly below the level achieved prior to the onset |

| C. Duration: Continuous signs of the disturbance persist for at least 6 months. This 6-month period must include at least 1 month of symptoms that meet Criterion A and may include periods of prodromal or residual symptoms |

| D. Schizoaffective and mood disorder exclusion: Schizoaffective disorder and mood disorder with psychotic features have been ruled out because either (1) no major depressive, manic, or mixed episodes have occurred concurrently with the active-phase symptoms; or (2) if mood episodes have occurred during active-phase symptoms, their total duration has been brief relative to the duration of the active and residual periods |

| E. Substance/general medical condition exclusion: The disturbance is not due to the direct physiological effects of a substance or a general medical condition |

| F. Relationship to a pervasive developmental disorder: If there is a history of autistic disorder or another pervasive developmental disorder, the additional diagnosis of schizophrenia is made only if prominent delusions or hallucinations are also present for at least 1 month |

| Diagnostic criteria for paranoid type: A type of schizophrenia in which the following criteria are met: A. Preoccupation with ≥1 delusions or frequent auditory hallucinations B. None of the following are prominent: disorganized speech, disorganized or catatonic behavior, or flat or inappropriate affect |

| Source: Reference 7 |

The authors’ observations

Various treatments can be used for paranoia with aggression, but the severity of the paranoia should be assessed before initiating treatment. Although categorizing paranoid ideations as mild, moderate, and severe is mainly a clinical judgment, Freeman et al1 have attempted to design a paranoia hierarchy from social concerns to severe threats. CBT8 and antipsychotic medication may help reduce mild to moderate paranoid delusions, particularly those associated with schizophrenia or mood disorders. For severe paranoia, hospitalization should carefully be considered.

When a patient exhibits moderate paranoia, the probability of progressing to severe symptoms or improving to mild symptoms depends on several variables. Pharmacologic treatment, family insight, and social support may be important variables in such circumstances. Psychoeducation for the family is vital.

In patients experiencing paranoia, violence may be prevented by proper assessment and treatment. The patient’s family should be educated about paranoid ideation and the need for treatment to improve symptoms and ensure safety. The long-term effects of untreated paranoia and types of treatment modalities available should be discussed with the family and the patient. During these teaching sessions, focus on improving the overall insight of the family and the patient about the psychotic illness to improve treatment adherence.9 This step may be challenging if the family is resistant to the patient receiving mental health treatment.

Gaining a detailed clinical history of a patient’s paranoia is important. A clinician should look for changes in behavior, such as the patient becoming quieter or more hostile, and impaired academic or social functioning. After gathering sufficient evidence contrary to the delusion, clinicians can help patients improve their reality testing.

Rule out medical and neurologic conditions that may be contributing to paranoia and aggression.

TREATMENT: Some improvement

Ms. V is started on risperidone, 1 mg/d, which leads to a partial response. She starts interacting more with staff and her peers on the unit, but her delusions of her sister poisioning her persist. Given the severity of the crime, Ms. V is sent to adult court, where she is found not guilty by reason of insanity and committed to a state hospital.

The authors’ observations

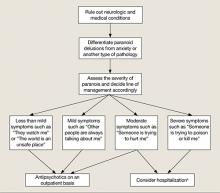

New-onset paranoia is a serious symptom that requires immediate evaluation and treatment. We recommend an approach presened in a flowchart (Figure) that highlights the importance of early intervention and aggressive treatment.

The MacArthur Violence Risk Assessment Study10 indicated that a “suspicious” attitude toward others can be a precipitating cause for increased violence in some cases. In light of ongoing controversy regarding the link between violence and mental illnesses such as schizophrenia,10-12 addressing an individual’s psychiatric illness early is preferable to prevent possible complications such as violent crimes. Because patients with paranoid ideations may have severely impaired ego control, they may be at risk for acting out aggressive and/or destructive urges. Therefore, new-onset paranoia should be thought of as a medical emergency similar to chest pain. Although accurately predicting and preventing violence may be impossible, in Ms. V’s case, earlier mental health treatment and intervention may have been able to prevent a murder.

Figure: Paranoia: A suggested approach to treatment

aBased on clinical judgment and extent of social support

Symptoms may become less severe or more severe (bidirectional). Strong social support has a positive effect on all levels and complements therapy. Regular counseling sessions and enhanced family insight about the patient’s paranoia helps strengthen social support

- Marneros A, Pillmann F, Wustmann T. Delusional disorders—are they simply paranoid schizophrenia? [published online ahead of print November 15, 2010]. Schizophr Bull. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbq125.

Drug Brand Names

Amphetamine and dextroamphetamine • Adderall

Risperidone • Risperdal

Disclosures

The authors report no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

Personal and clinical details of this case were altered to maintain patient confidentiality.

1. Freeman D, Garety PA, Bebbington PE, et al. Psychological investigation of the structure of paranoia in a non-clinical population. Br J Psychiatry. 2005;186:427-435.

2. Kendler KS, Hays P. Paranoid psychosis (delusional disorder) and schizophrenia. A family history study. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1981;38(5):547-551.

3. CNN Wire Staff. Police “actively pursuing” second person in Tucson shooting. CNN. http://us.cnn.com/2011/CRIME/01/08/arizona.shooting. Published January 9 2011. Accessed January 9, 2012.

4. Lipton E, Savage C, Shane S. Arizona suspect’s recent acts offer hints of alienation. The New York Times. January 8 2011:A8. http://www.nytimes.com/2011/01/09/us/politics/09shooter.html. Accessed January 10, 2012.

5. Berger J. Mental health warnings preceded rampage as Arizona gunman likely went untreated. http://www.foxnews.com/us/2011/01/10/mental-health-warnings-preceded-arizona-rampage-evidence-gunman-sought. Published January 10, 2011. Accessed January 11, 2012.

6. Lacey M. Suspect in shooting of Giffords ruled unfit for trial. The New York Times. May 25 2011:A1. http://www.nytimes.com/2011/05/26/us/26loughner.html. Accessed January 5, 2012.

7. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 4th ed, text rev. Washington DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2000.

8. Turkington D, Kingdon D, Weiden PJ. Cognitive behavior therapy for schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163(3):365-373.

9. Smith CM, Barzman DH, Pristach CA. Effect of patient and family insight on compliance of schizophrenic patients. J Clin Pharmacol. 1997;37(2):147-154.

10. Appelbaum PS, Robbins PC, Monahan J. Violence and delusions: data from the MacArthur Violence Risk Assessment Study. Am J Psychiatry. 2000;157(4):566-572.

11. Mullen PE. A reassessment of the link between mental disorder and violent behaviour and its implications for clinical practice. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 1997;31(1):3-11.

12. Fazel S, Gulati G, Linsell L, et al. Schizophrenia and violence: systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS Med. 2009;6(8):e1000120.-

Discuss this article at www.facebook.com/CurrentPsychiatry

CASE: Sleepless and paranoid

Ms. V, age 16, is referred to our psychiatric hospital from a juvenile detention center after she is charged with killing her sister with a hammer. She reports paranoid delusions, including believing that her sister was poisoning her food. Ms. V’s troubling behavior increased in the 6 months before the murder. She began to ask her mother to smell her food for possible poison. Her school grades dropped and she experienced decreased sleep and appetite. According to her mother, Ms. V’s insomnia worsened recently because of her paranoid thinking, which was evident when she noticed that her daughter slept with a hammer. Ms. V stopped socializing with her peers and no longer went to the gym.

Ms. V’s mother describes her daughter’s negative symptoms as consisting of social isolation and a flat affect. There was no evidence of auditory or visual hallucinations. After noticing the change in her daughter’s behavior, Ms. V’s mother attempted to schedule an appointment with a mental health professional, but there was a 2-month waiting list.

Ms. V cleaned her room before the murder, which was uncharacteristic of her routine behavior. On the day of the murder, Ms. V approached her sister while she was sleeping on the sofa and struck her on the head several times with a hammer. After the sister died, neighbors spotted Ms. V washing blood off her hands in their backyard with a sprinkler. Soaked in blood, she approached one of the neighbors and said that someone had been killed in the house. The neighbors called the police and Ms. V was arrested. She did not express remorse. She did not exhibit physical aggression toward others before the murder. Ms. V’s sense of entitlement and grandiosity persisted after the murder.

The authors’ observations

Paranoid delusions are fixed false beliefs with severe fears of others that may impair functioning at school or work, in personal relationships, and in other social dimensions. Paranoid thinking can have diverse presentations, ranging from social concerns such as fear of rejection to severe threat perceptions of people trying to cause substantial physical harm.1 Paranoid thoughts can be a result of misinterpretation of language, a personality disorder, anxiety, or psychosis.

Feelings of low self-esteem2 and anger1 may develop in a patient experiencing paranoid ideations. When anger begins to escalate, it may erupt into violent behavior. In Ms. V’s case, her paranoid ideations increased until she killed her younger sister. Ms. V’s case is similar to a mass shooting near Tucson, AZ on January 8, 2011 in that it possibly could have been prevented with earlier psychiatric intervention (Box).3-6

On January 8, 2011, a mass shooting occurred near Tucson, AZ that killed 6 and wounded 13. The suspect, 22-year-old Jared Lee Loughner, refused to cooperate with authorities by invoking his right to remain silent.3 Although the motives behind this crime remain undisclosed, mental illness appears to be a contributing factor.

Reports indicate that Mr. Loughner was abusing drugs and those close to him had noticed personality changes.4,5 The college he was attending advised Mr. Loughner to undergo a mental health evaluation, but he refused and dropped out of school.4,5 While in custody after the shooting, Mr. Loughner was diagnosed with paranoid schizophrenia, deemed incompetent to stand trial, and ordered to receive psychiatric treatment.6

This tragic mass shooting and similar incidents have led to questions regarding the adequacy of the mental health care infrastructure in United States. Experts suggest that this tragedy could have been prevented with more aggressive psychiatric prevention and intervention. Critical analysis of similar recent cases and expert opinions are needed to address this problem effectively.

EVALUATION: Remorseless

At admission, Ms. V’s affect is restricted and, at times, inappropriate. She is guarded about discussing the homicide but describes paranoid thoughts about her sister poisoning her. She is eager to learn if the police had found poison in her food. Her speech is soft with good articulation. Based on her presentation, her intelligence is average. She shows no evidence of remorse and is preoccupied with her sister poisoning her.

The Rorschach Inkblot Technique reveals positive evidence for a severe thought disorder. Ms. V’s thinking seems regressed. Ms. V’s medical workup, including MRI, electroencephalogram, and laboratory tests, are all within normal limits.

In the 5th grade, Ms. V’s primary care provider prescribed amphetamine and dextroamphetamine for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, but she discontinued the drug after 1 year. Ms. V has never been hospitalized for psychiatric illness. She had no chronic medical conditions and no developmental delays.

Ms. V also has a history of periodic temper problems characterized by verbal aggression such as threatening the assistant principal at her school, and throwing her cellphone at her mother a few weeks before the murder, but no other aggressive episodes. Ms. V’s history does not suggest conduct disorder. She has no history of suicidal ideation or suicide attempts. Ms. V has used alcohol since age 15, but her mother reports that she was not a heavy or frequent user. Her last reported alcohol use was 10 days before the murder. A maternal uncle had been diagnosed with schizophrenia.

Before the murder, Ms. V lived with her sister and mother. Her parents were divorced. At age 9, Ms. V was sexually abused by a soccer coach; however, she denied symptoms of posttraumatic stress disorder related to the sexual abuse. She had no criminal history before the murder.

The authors’ observations

Based on Ms. V’s presentation and history, schizophrenia, paranoid type seems to be the most likely diagnosis because of her negative symptoms, including affective flattening, positive family history for schizophrenia, and paranoid delusions leading to dysfunction (Table).7 Delusional disorder seems less likely because Ms. V is young and has negative symptoms. Because she is generally healthy and her medical workup is negative, psychotic disorder due to a general medical condition is ruled out. She does not appear to be over-reporting, malingering, or exaggerating symptoms. In the context of psychosis, adolescent psychopathy does not seem likely even though there is evidence of grandiosity and a lack of remorse.

Table

DSM-IV-TR criteria for schizophrenia

A. Characteristic symptoms: ≥2 of the following, each present for a significant portion of time during a 1-month period:

|

| B. Social/occupational dysfunction: For a significant portion of the time since the onset of the disturbance, ≥1 major areas of functioning such as work, interpersonal relations, or self-care are markedly below the level achieved prior to the onset |

| C. Duration: Continuous signs of the disturbance persist for at least 6 months. This 6-month period must include at least 1 month of symptoms that meet Criterion A and may include periods of prodromal or residual symptoms |

| D. Schizoaffective and mood disorder exclusion: Schizoaffective disorder and mood disorder with psychotic features have been ruled out because either (1) no major depressive, manic, or mixed episodes have occurred concurrently with the active-phase symptoms; or (2) if mood episodes have occurred during active-phase symptoms, their total duration has been brief relative to the duration of the active and residual periods |

| E. Substance/general medical condition exclusion: The disturbance is not due to the direct physiological effects of a substance or a general medical condition |

| F. Relationship to a pervasive developmental disorder: If there is a history of autistic disorder or another pervasive developmental disorder, the additional diagnosis of schizophrenia is made only if prominent delusions or hallucinations are also present for at least 1 month |

| Diagnostic criteria for paranoid type: A type of schizophrenia in which the following criteria are met: A. Preoccupation with ≥1 delusions or frequent auditory hallucinations B. None of the following are prominent: disorganized speech, disorganized or catatonic behavior, or flat or inappropriate affect |

| Source: Reference 7 |

The authors’ observations

Various treatments can be used for paranoia with aggression, but the severity of the paranoia should be assessed before initiating treatment. Although categorizing paranoid ideations as mild, moderate, and severe is mainly a clinical judgment, Freeman et al1 have attempted to design a paranoia hierarchy from social concerns to severe threats. CBT8 and antipsychotic medication may help reduce mild to moderate paranoid delusions, particularly those associated with schizophrenia or mood disorders. For severe paranoia, hospitalization should carefully be considered.

When a patient exhibits moderate paranoia, the probability of progressing to severe symptoms or improving to mild symptoms depends on several variables. Pharmacologic treatment, family insight, and social support may be important variables in such circumstances. Psychoeducation for the family is vital.

In patients experiencing paranoia, violence may be prevented by proper assessment and treatment. The patient’s family should be educated about paranoid ideation and the need for treatment to improve symptoms and ensure safety. The long-term effects of untreated paranoia and types of treatment modalities available should be discussed with the family and the patient. During these teaching sessions, focus on improving the overall insight of the family and the patient about the psychotic illness to improve treatment adherence.9 This step may be challenging if the family is resistant to the patient receiving mental health treatment.

Gaining a detailed clinical history of a patient’s paranoia is important. A clinician should look for changes in behavior, such as the patient becoming quieter or more hostile, and impaired academic or social functioning. After gathering sufficient evidence contrary to the delusion, clinicians can help patients improve their reality testing.

Rule out medical and neurologic conditions that may be contributing to paranoia and aggression.

TREATMENT: Some improvement

Ms. V is started on risperidone, 1 mg/d, which leads to a partial response. She starts interacting more with staff and her peers on the unit, but her delusions of her sister poisioning her persist. Given the severity of the crime, Ms. V is sent to adult court, where she is found not guilty by reason of insanity and committed to a state hospital.

The authors’ observations

New-onset paranoia is a serious symptom that requires immediate evaluation and treatment. We recommend an approach presened in a flowchart (Figure) that highlights the importance of early intervention and aggressive treatment.

The MacArthur Violence Risk Assessment Study10 indicated that a “suspicious” attitude toward others can be a precipitating cause for increased violence in some cases. In light of ongoing controversy regarding the link between violence and mental illnesses such as schizophrenia,10-12 addressing an individual’s psychiatric illness early is preferable to prevent possible complications such as violent crimes. Because patients with paranoid ideations may have severely impaired ego control, they may be at risk for acting out aggressive and/or destructive urges. Therefore, new-onset paranoia should be thought of as a medical emergency similar to chest pain. Although accurately predicting and preventing violence may be impossible, in Ms. V’s case, earlier mental health treatment and intervention may have been able to prevent a murder.

Figure: Paranoia: A suggested approach to treatment

aBased on clinical judgment and extent of social support

Symptoms may become less severe or more severe (bidirectional). Strong social support has a positive effect on all levels and complements therapy. Regular counseling sessions and enhanced family insight about the patient’s paranoia helps strengthen social support

- Marneros A, Pillmann F, Wustmann T. Delusional disorders—are they simply paranoid schizophrenia? [published online ahead of print November 15, 2010]. Schizophr Bull. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbq125.

Drug Brand Names

Amphetamine and dextroamphetamine • Adderall

Risperidone • Risperdal

Disclosures

The authors report no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

Personal and clinical details of this case were altered to maintain patient confidentiality.

Discuss this article at www.facebook.com/CurrentPsychiatry

CASE: Sleepless and paranoid

Ms. V, age 16, is referred to our psychiatric hospital from a juvenile detention center after she is charged with killing her sister with a hammer. She reports paranoid delusions, including believing that her sister was poisoning her food. Ms. V’s troubling behavior increased in the 6 months before the murder. She began to ask her mother to smell her food for possible poison. Her school grades dropped and she experienced decreased sleep and appetite. According to her mother, Ms. V’s insomnia worsened recently because of her paranoid thinking, which was evident when she noticed that her daughter slept with a hammer. Ms. V stopped socializing with her peers and no longer went to the gym.

Ms. V’s mother describes her daughter’s negative symptoms as consisting of social isolation and a flat affect. There was no evidence of auditory or visual hallucinations. After noticing the change in her daughter’s behavior, Ms. V’s mother attempted to schedule an appointment with a mental health professional, but there was a 2-month waiting list.

Ms. V cleaned her room before the murder, which was uncharacteristic of her routine behavior. On the day of the murder, Ms. V approached her sister while she was sleeping on the sofa and struck her on the head several times with a hammer. After the sister died, neighbors spotted Ms. V washing blood off her hands in their backyard with a sprinkler. Soaked in blood, she approached one of the neighbors and said that someone had been killed in the house. The neighbors called the police and Ms. V was arrested. She did not express remorse. She did not exhibit physical aggression toward others before the murder. Ms. V’s sense of entitlement and grandiosity persisted after the murder.

The authors’ observations

Paranoid delusions are fixed false beliefs with severe fears of others that may impair functioning at school or work, in personal relationships, and in other social dimensions. Paranoid thinking can have diverse presentations, ranging from social concerns such as fear of rejection to severe threat perceptions of people trying to cause substantial physical harm.1 Paranoid thoughts can be a result of misinterpretation of language, a personality disorder, anxiety, or psychosis.

Feelings of low self-esteem2 and anger1 may develop in a patient experiencing paranoid ideations. When anger begins to escalate, it may erupt into violent behavior. In Ms. V’s case, her paranoid ideations increased until she killed her younger sister. Ms. V’s case is similar to a mass shooting near Tucson, AZ on January 8, 2011 in that it possibly could have been prevented with earlier psychiatric intervention (Box).3-6

On January 8, 2011, a mass shooting occurred near Tucson, AZ that killed 6 and wounded 13. The suspect, 22-year-old Jared Lee Loughner, refused to cooperate with authorities by invoking his right to remain silent.3 Although the motives behind this crime remain undisclosed, mental illness appears to be a contributing factor.

Reports indicate that Mr. Loughner was abusing drugs and those close to him had noticed personality changes.4,5 The college he was attending advised Mr. Loughner to undergo a mental health evaluation, but he refused and dropped out of school.4,5 While in custody after the shooting, Mr. Loughner was diagnosed with paranoid schizophrenia, deemed incompetent to stand trial, and ordered to receive psychiatric treatment.6

This tragic mass shooting and similar incidents have led to questions regarding the adequacy of the mental health care infrastructure in United States. Experts suggest that this tragedy could have been prevented with more aggressive psychiatric prevention and intervention. Critical analysis of similar recent cases and expert opinions are needed to address this problem effectively.

EVALUATION: Remorseless

At admission, Ms. V’s affect is restricted and, at times, inappropriate. She is guarded about discussing the homicide but describes paranoid thoughts about her sister poisoning her. She is eager to learn if the police had found poison in her food. Her speech is soft with good articulation. Based on her presentation, her intelligence is average. She shows no evidence of remorse and is preoccupied with her sister poisoning her.

The Rorschach Inkblot Technique reveals positive evidence for a severe thought disorder. Ms. V’s thinking seems regressed. Ms. V’s medical workup, including MRI, electroencephalogram, and laboratory tests, are all within normal limits.

In the 5th grade, Ms. V’s primary care provider prescribed amphetamine and dextroamphetamine for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, but she discontinued the drug after 1 year. Ms. V has never been hospitalized for psychiatric illness. She had no chronic medical conditions and no developmental delays.

Ms. V also has a history of periodic temper problems characterized by verbal aggression such as threatening the assistant principal at her school, and throwing her cellphone at her mother a few weeks before the murder, but no other aggressive episodes. Ms. V’s history does not suggest conduct disorder. She has no history of suicidal ideation or suicide attempts. Ms. V has used alcohol since age 15, but her mother reports that she was not a heavy or frequent user. Her last reported alcohol use was 10 days before the murder. A maternal uncle had been diagnosed with schizophrenia.

Before the murder, Ms. V lived with her sister and mother. Her parents were divorced. At age 9, Ms. V was sexually abused by a soccer coach; however, she denied symptoms of posttraumatic stress disorder related to the sexual abuse. She had no criminal history before the murder.

The authors’ observations

Based on Ms. V’s presentation and history, schizophrenia, paranoid type seems to be the most likely diagnosis because of her negative symptoms, including affective flattening, positive family history for schizophrenia, and paranoid delusions leading to dysfunction (Table).7 Delusional disorder seems less likely because Ms. V is young and has negative symptoms. Because she is generally healthy and her medical workup is negative, psychotic disorder due to a general medical condition is ruled out. She does not appear to be over-reporting, malingering, or exaggerating symptoms. In the context of psychosis, adolescent psychopathy does not seem likely even though there is evidence of grandiosity and a lack of remorse.

Table

DSM-IV-TR criteria for schizophrenia

A. Characteristic symptoms: ≥2 of the following, each present for a significant portion of time during a 1-month period:

|

| B. Social/occupational dysfunction: For a significant portion of the time since the onset of the disturbance, ≥1 major areas of functioning such as work, interpersonal relations, or self-care are markedly below the level achieved prior to the onset |

| C. Duration: Continuous signs of the disturbance persist for at least 6 months. This 6-month period must include at least 1 month of symptoms that meet Criterion A and may include periods of prodromal or residual symptoms |

| D. Schizoaffective and mood disorder exclusion: Schizoaffective disorder and mood disorder with psychotic features have been ruled out because either (1) no major depressive, manic, or mixed episodes have occurred concurrently with the active-phase symptoms; or (2) if mood episodes have occurred during active-phase symptoms, their total duration has been brief relative to the duration of the active and residual periods |

| E. Substance/general medical condition exclusion: The disturbance is not due to the direct physiological effects of a substance or a general medical condition |

| F. Relationship to a pervasive developmental disorder: If there is a history of autistic disorder or another pervasive developmental disorder, the additional diagnosis of schizophrenia is made only if prominent delusions or hallucinations are also present for at least 1 month |

| Diagnostic criteria for paranoid type: A type of schizophrenia in which the following criteria are met: A. Preoccupation with ≥1 delusions or frequent auditory hallucinations B. None of the following are prominent: disorganized speech, disorganized or catatonic behavior, or flat or inappropriate affect |

| Source: Reference 7 |

The authors’ observations

Various treatments can be used for paranoia with aggression, but the severity of the paranoia should be assessed before initiating treatment. Although categorizing paranoid ideations as mild, moderate, and severe is mainly a clinical judgment, Freeman et al1 have attempted to design a paranoia hierarchy from social concerns to severe threats. CBT8 and antipsychotic medication may help reduce mild to moderate paranoid delusions, particularly those associated with schizophrenia or mood disorders. For severe paranoia, hospitalization should carefully be considered.

When a patient exhibits moderate paranoia, the probability of progressing to severe symptoms or improving to mild symptoms depends on several variables. Pharmacologic treatment, family insight, and social support may be important variables in such circumstances. Psychoeducation for the family is vital.

In patients experiencing paranoia, violence may be prevented by proper assessment and treatment. The patient’s family should be educated about paranoid ideation and the need for treatment to improve symptoms and ensure safety. The long-term effects of untreated paranoia and types of treatment modalities available should be discussed with the family and the patient. During these teaching sessions, focus on improving the overall insight of the family and the patient about the psychotic illness to improve treatment adherence.9 This step may be challenging if the family is resistant to the patient receiving mental health treatment.

Gaining a detailed clinical history of a patient’s paranoia is important. A clinician should look for changes in behavior, such as the patient becoming quieter or more hostile, and impaired academic or social functioning. After gathering sufficient evidence contrary to the delusion, clinicians can help patients improve their reality testing.

Rule out medical and neurologic conditions that may be contributing to paranoia and aggression.

TREATMENT: Some improvement

Ms. V is started on risperidone, 1 mg/d, which leads to a partial response. She starts interacting more with staff and her peers on the unit, but her delusions of her sister poisioning her persist. Given the severity of the crime, Ms. V is sent to adult court, where she is found not guilty by reason of insanity and committed to a state hospital.

The authors’ observations

New-onset paranoia is a serious symptom that requires immediate evaluation and treatment. We recommend an approach presened in a flowchart (Figure) that highlights the importance of early intervention and aggressive treatment.

The MacArthur Violence Risk Assessment Study10 indicated that a “suspicious” attitude toward others can be a precipitating cause for increased violence in some cases. In light of ongoing controversy regarding the link between violence and mental illnesses such as schizophrenia,10-12 addressing an individual’s psychiatric illness early is preferable to prevent possible complications such as violent crimes. Because patients with paranoid ideations may have severely impaired ego control, they may be at risk for acting out aggressive and/or destructive urges. Therefore, new-onset paranoia should be thought of as a medical emergency similar to chest pain. Although accurately predicting and preventing violence may be impossible, in Ms. V’s case, earlier mental health treatment and intervention may have been able to prevent a murder.

Figure: Paranoia: A suggested approach to treatment

aBased on clinical judgment and extent of social support

Symptoms may become less severe or more severe (bidirectional). Strong social support has a positive effect on all levels and complements therapy. Regular counseling sessions and enhanced family insight about the patient’s paranoia helps strengthen social support

- Marneros A, Pillmann F, Wustmann T. Delusional disorders—are they simply paranoid schizophrenia? [published online ahead of print November 15, 2010]. Schizophr Bull. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbq125.

Drug Brand Names

Amphetamine and dextroamphetamine • Adderall

Risperidone • Risperdal

Disclosures

The authors report no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

Personal and clinical details of this case were altered to maintain patient confidentiality.

1. Freeman D, Garety PA, Bebbington PE, et al. Psychological investigation of the structure of paranoia in a non-clinical population. Br J Psychiatry. 2005;186:427-435.

2. Kendler KS, Hays P. Paranoid psychosis (delusional disorder) and schizophrenia. A family history study. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1981;38(5):547-551.

3. CNN Wire Staff. Police “actively pursuing” second person in Tucson shooting. CNN. http://us.cnn.com/2011/CRIME/01/08/arizona.shooting. Published January 9 2011. Accessed January 9, 2012.

4. Lipton E, Savage C, Shane S. Arizona suspect’s recent acts offer hints of alienation. The New York Times. January 8 2011:A8. http://www.nytimes.com/2011/01/09/us/politics/09shooter.html. Accessed January 10, 2012.

5. Berger J. Mental health warnings preceded rampage as Arizona gunman likely went untreated. http://www.foxnews.com/us/2011/01/10/mental-health-warnings-preceded-arizona-rampage-evidence-gunman-sought. Published January 10, 2011. Accessed January 11, 2012.

6. Lacey M. Suspect in shooting of Giffords ruled unfit for trial. The New York Times. May 25 2011:A1. http://www.nytimes.com/2011/05/26/us/26loughner.html. Accessed January 5, 2012.

7. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 4th ed, text rev. Washington DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2000.

8. Turkington D, Kingdon D, Weiden PJ. Cognitive behavior therapy for schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163(3):365-373.

9. Smith CM, Barzman DH, Pristach CA. Effect of patient and family insight on compliance of schizophrenic patients. J Clin Pharmacol. 1997;37(2):147-154.

10. Appelbaum PS, Robbins PC, Monahan J. Violence and delusions: data from the MacArthur Violence Risk Assessment Study. Am J Psychiatry. 2000;157(4):566-572.

11. Mullen PE. A reassessment of the link between mental disorder and violent behaviour and its implications for clinical practice. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 1997;31(1):3-11.

12. Fazel S, Gulati G, Linsell L, et al. Schizophrenia and violence: systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS Med. 2009;6(8):e1000120.-

1. Freeman D, Garety PA, Bebbington PE, et al. Psychological investigation of the structure of paranoia in a non-clinical population. Br J Psychiatry. 2005;186:427-435.

2. Kendler KS, Hays P. Paranoid psychosis (delusional disorder) and schizophrenia. A family history study. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1981;38(5):547-551.

3. CNN Wire Staff. Police “actively pursuing” second person in Tucson shooting. CNN. http://us.cnn.com/2011/CRIME/01/08/arizona.shooting. Published January 9 2011. Accessed January 9, 2012.

4. Lipton E, Savage C, Shane S. Arizona suspect’s recent acts offer hints of alienation. The New York Times. January 8 2011:A8. http://www.nytimes.com/2011/01/09/us/politics/09shooter.html. Accessed January 10, 2012.

5. Berger J. Mental health warnings preceded rampage as Arizona gunman likely went untreated. http://www.foxnews.com/us/2011/01/10/mental-health-warnings-preceded-arizona-rampage-evidence-gunman-sought. Published January 10, 2011. Accessed January 11, 2012.

6. Lacey M. Suspect in shooting of Giffords ruled unfit for trial. The New York Times. May 25 2011:A1. http://www.nytimes.com/2011/05/26/us/26loughner.html. Accessed January 5, 2012.

7. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 4th ed, text rev. Washington DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2000.

8. Turkington D, Kingdon D, Weiden PJ. Cognitive behavior therapy for schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163(3):365-373.

9. Smith CM, Barzman DH, Pristach CA. Effect of patient and family insight on compliance of schizophrenic patients. J Clin Pharmacol. 1997;37(2):147-154.

10. Appelbaum PS, Robbins PC, Monahan J. Violence and delusions: data from the MacArthur Violence Risk Assessment Study. Am J Psychiatry. 2000;157(4):566-572.

11. Mullen PE. A reassessment of the link between mental disorder and violent behaviour and its implications for clinical practice. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 1997;31(1):3-11.

12. Fazel S, Gulati G, Linsell L, et al. Schizophrenia and violence: systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS Med. 2009;6(8):e1000120.-