User login

What Is the Best Approach to Medical Therapy for Patients with Ischemic Stroke?

Case

A 58-year-old woman with diabetes mellitus and hypertension presents with dysarthria and weakness on the right side of her body starting six hours prior to presentation. She is afebrile and has a blood pressure of 162/84 mmHg. Exam reveals the absence of a heart murmur and no lower-extremity swelling or calf tenderness. There is weakness of the right side of the body on exam with diminished proprioception. A noncontrast head CT shows no intracranial hemorrhage. She is admitted to the hospital with the diagnosis of acute ischemic stroke. What anticlotting or antiplatelet medications should she receive?

Overview

Stroke remains a significant cause of morbidity and mortality in the U.S. and around the world. The majority of strokes are ischemic in etiology. Although thrombolytic therapy is the most effective way to salvage ischemic brain tissue that has not yet infarcted, there is a narrow window for the use of thrombolytics in the treatment of acute ischemic stroke. As a result, many patients will not be eligible for thrombolysis. Outside of 4.5 hours from symptom onset, evidence suggests that the risk outweighs the benefit of using the thrombolytic alteplase. For patients ineligible for thrombolytic therapy, antiplatelet therapy remains the best choice for treatment.

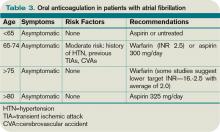

Medications that prevent blood from coagulating or clotting are used to treat and prevent a recurring or second stroke. Typically, an antiplatelet agent (most often aspirin) is initiated within 48 hours of an ischemic stroke and continued in low doses as maintenance. Multiple studies suggest that antiplatelet therapy can reduce the risk for a second stroke by 25%. Specific anticlotting agents might be warranted in some patients with high-risk conditions for a stroke.

Review of Data

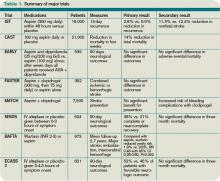

Early initiation of aspirin has shown benefit in the treatment of an acute ischemic stroke. Two major trials—the International Stroke Trial (IST) and the Chinese Acute Stroke Trial (CAST)— evaluated the role of aspirin (see Table 1, p. 15).1,2 The IST and CAST trials showed that roughly nine nonfatal strokes were avoided per every 1,000 early treatments. Taking the endpoint of death, as well as focal deficits, the two trials confirmed a rate of reduction of 13 per 1,000 patients.

Overall, the consensus was that initiating aspirin within 48 hours of a presumed ischemic cerebrovascular accident posed no major risk of hemorrhagic complication and improved the long-term outcomes.

Along with aspirin, other antiplatelet agents have been studied, most commonly dipyridamole and clopidrogel. The EARLY trial demonstrated no significant differences in the aspirin and dipyridamole groups at 90 days.3

Another large trial, which focused on clopidrogel and aspirin, looked at aspirin plus clopidrogel or aspirin alone. The FASTER trial enrolled mostly patients with mild cerebrovasular accidents (CVA) or transient ischemic attacks (TIA), and there was no difference in outcome measures between the groups.4 However, the MATCH trial found that aspirin and clopidrogel did not provide improved stroke preventions versus clopidogrel alone but had a larger risk of hemorrhagic/bleeding complications.5

Aspirin dosage is somewhat controversial. Fewer side effects occur with lower doses. Combining the trials, consensus treatment includes early aspirin dosing (325 mg initially, then 150 mg-325 mg daily) given to patients with ischemic stroke. Early aspirin should be avoided in those patients who qualify for and are receiving alteplase, heparin, or oral warfarin therapy.

There are other antiplatelet agents for long-term management of ischemic stroke. Whereas aspirin alone is used in the early management of acute ischemic stroke in those ineligible for thrombolytic therapy, many patients are transitioned to other antiplatelet strategies for secondary prevention long-term. The number needed to treat for aspirin to reduce one future stroke, myocardial infarction (MI), or vascular death when compared to placebo is quite high at 33. However, the combination of aspirin and dipyradimole does not prevent MI, vascular death, or the combined endpoint of either stroke or death.

Clopidogrel is more effective than aspirin in preventing a combined endpoint of ischemic stroke, MI, or vascular death, but it is not superior to aspirin in preventing recurrent stroke in TIA or stroke patients. The effects of clopidrogel are greater in patients with peripheral arterial disease, previous coronary artery bypass grafting, insulin-dependent diabetes, or recurrent vascular events.

There is a substantially high cost of treatment and long-term disability associated with stroke. Costs can vary from 3% to 5% of the annual healthcare budget. The newer antiplatelet agents are more expensive than aspirin, and overall cost-effectiveness is difficult to estimate. Yet, from an economic standpoint, the combination of aspirin and dipyradimole can be recommended as an alternative for secondary stroke prevention in patients without major comorbidities. In those patients with higher risk factors and/or comorbidities, clopidogrel might be more cost-effective than aspirin alone. Furthermore, in patients with aspirin intolerance, clopidogrel is a useful, but expensive, alternative.

Thrombolytic therapy. Restora-tion of blood flow with thrombolytic therapy is the most effective way of salvaging ischemic brain tissue that has not already infarcted. The window for use of the thrombolytic alteplase is narrow; studies suggest that its benefit diminishes with increasing time to treatment. Indeed, after 4.5 hours from the onset of symptoms, evidence suggests that the harm might outweigh the benefit, so the determination of who is eligible for its use has to be made quickly.

Guidelines published by the American Heart Association/American Stoke Association stroke council outline strict inclusion and exclusion criteria for the use of alteplase in the management of acute ischemic stroke.6 Obtaining informed consent and emergent neuroimaging are vital in preventing delays in alteplase administration.

Two major trials that illustrate the benefit of alteplase in the treatment of acute ischemic stroke are the NINDS trial and the ECASS 3 trial. NINDS showed that when intravenous alteplase was used within three hours of symptom onset, patients had improved functional outcome at three months.7 The ECASS 3 trial showed that intravenous alteplase has benefit when given up to 4.5 hours after symptom onset.8 Treatment with intravenous alteplase from three-4.5 hours in the ECASS 3 trial showed a modest improvement in patient outcomes at three months, with a number needed to treat of 14 for a favorable outcome.

A 2010 meta-analysis looked specifically at outcomes in stroke based on time to treat with alteplase using pooled data from the NINDS, ATLANTIS, ECASS (1, 2, and 3), and EPITHET trials.9 It showed that the number needed to treat for a favorable outcome at three months increased steadily when time to treatment was delayed. It also showed that the risk of death after alteplase administration increased significantly after 4.5 hours. Thus, after 4.5 hours, it suggests that harm might exceed the benefits of treatment.

Anticoagulant use in ischemic stroke. Clinical trials have not been effective in demonstrating the use of heparin and low-molecular-weight heparins (LMWHs). A 2008 systematic review of 24 trials (approximately 24,000 patients) demonstrated:

- Anticoagulant therapy did not reduce odds of death;

- Therapy was associated with nine fewer recurrent ischemic strokes per 1,000 patients, but also showed a similar increase in symptomatic intracranial hemorrhages; and

- Overall, researchers could not specify a particular anticoagulant mode or regimen that had an overall net patient benefit.

The use of heparin in atrial fibrillation and stroke has generated controversy in recent years. Review of the data, however, indicates that early treatment with heparin might cause more harm than benefit. A 2007 meta-analysis did not support the use of early anticoagulant therapy. Seven trials (4,200 patients) compared heparin or LMWH started within 48 hours to other treatments (aspirin, placebo). The study authors found:

- Nonsignificant reduction in recurrent ischemic stroke within seven to 14 days;

- Statistically significant increase in symptomatic intracranial hemorrhages; and

- Similar rates of death/disability at final follow-up of studies.

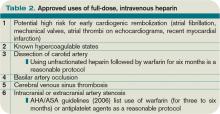

For those patients who continue to demonstrate neurological deterioration, heparin and LMWH use did not appear to improve outcomes. Therefore, based on a consensus of national guidelines, the use of full-dose anticoagulation with heparin or LMWH is not recommended.

The data suggest that in patients with stroke secondary to:

- Dissection of cervical or intracranial arteries;

- Intracardiac thrombus and valvular disease; and

- Mechanical heart valves, full-dose anticoagulation can be initiated. However, the benefit is unproven.

Back to the Case

Our patient with acute ischemic stroke with right-sided weakness on exam presented outside of the window within which alteplase could be administered safely. She was started on aspirin 325 mg daily. There was no indication for full anticoagulation with intravenous heparin or warfarin. Her weakness showed slight improvement on exam during the hospitalization. As an insulin-dependent diabetic, she was thought to be at high risk for recurrent stroke. As such, she was transitioned to a combination of aspirin and clopidogrel prior to her discharge to an acute inpatient rehabilitation hospital.

Bottom Line

Early aspirin therapy (within 48 hours) is recommended (initial dose 325 mg, then 150 mg-325 mg daily) for patients with ischemic stroke who are not candidates for alteplase, IV heparin, or oral anticoagulants.10 Aspirin is the only antiplatelet agent that has been shown to be effective for the early treatment of acute ischemic stroke. In patients without contraindications, aspirin, the combination of aspirin-dipyradimole, or clopidogrel is appropriate for secondary prevention.

The subset of patients at high risk of recurrent stroke should be transitioned to clopidogrel or aspirin/clopidogrel, unless otherwise contraindicated. TH

Dr. Chaturvedi is an instructor in the Division of Hospital Medicine at Northwestern University’s Feinberg School of Medicine in Chicago, and medical director of HM at Northwestern Lake Forest Hospital. Dr. Abraham is an instructor in the Division of Hospital Medicine at Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine.

References

- The International Stroke Trial (IST): a randomised trial of aspirin, subcutaneous heparin, both, or neither among 19,435 patients with acute ischemic stroke. International Stroke Trial Collaborative Group. Lancet. 1997;349:1569-1581.

- CAST: randomised placebo-controlled trial of early aspirin use in 20,000 patients with acute ischaemic stroke. CAST (Chinese Acute Stroke Trial) Collaborative Group. Lancet. 1997;349:1641-1649.

- Dengler R, Diener HC, Schwartz A, et al. Early treatment with aspirin plus extended-release dipyridamole for transient ischaemic attack or ischaemic stroke within 24 h of symptom onset (EARLY trial): a randomised, open-label, blinded-endpoint trial. Lancet Neurol. 2010;9:159-166.

- Kennedy J, Hill MD, Ryckborst KJ, et al. Fast assessment of stroke and transient ischaemic attack to prevent early recurrence (FASTER): a randomised controlled pilot trial. Lancet Neurol. 2007;6:961-969.

- Diener HC, Bogousslavsky J, Brass LM, et al. Aspirin and clopidogrel compared with clopidogrel alone after recent ischaemic stroke or transient ischaemic attack in high-risk patients (MATCH): randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2004;364:331-337.

- Adams HP Jr, del Zoppo G, Alberts MJ, et al. Guidelines for the early management of adults with ischemic stroke: a guideline from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association Stroke Council, Clinical Cardiology Council, Cardiovascular Radiology and Intervention Council, and the Atherosclerotic Peripheral Vascular Disease and Quality of Care Outcomes in Research Interdisciplinary Working Groups: The American Academy of Neurology affirms the value of this guideline as an educational tool for neurologists. Stroke. 2007;38:1655-1711.

- Lees KR, Bluhmki E, von Kummer R, et al. Time to treatment with intravenous alteplase and outcome in stroke: an updated pooled analysis of ECASS, ATLANTIS, NINDS, and EPITHET trials. Lancet. 2010;375:1695-1703.

- Hacke W, Kaste M, Bluhmki E, et al. Thombolysis with alteplase 3 to 4.5 hours after acute ischemic stroke. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:1317-1329.

- Tissue plasminogen activator for acute ischemic stroke. The National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke rt-PA Stroke Study Group. N Engl J Med. 1995;333:1581-1587.

- Albers GW, Amarenco P, Easton JD, et al. Antithrombotic and thrombolytic therapy for ischemic stroke: American College of Chest Physicians Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guidelines (8th Edition). Chest. 2008;133:630S-669S.

Case

A 58-year-old woman with diabetes mellitus and hypertension presents with dysarthria and weakness on the right side of her body starting six hours prior to presentation. She is afebrile and has a blood pressure of 162/84 mmHg. Exam reveals the absence of a heart murmur and no lower-extremity swelling or calf tenderness. There is weakness of the right side of the body on exam with diminished proprioception. A noncontrast head CT shows no intracranial hemorrhage. She is admitted to the hospital with the diagnosis of acute ischemic stroke. What anticlotting or antiplatelet medications should she receive?

Overview

Stroke remains a significant cause of morbidity and mortality in the U.S. and around the world. The majority of strokes are ischemic in etiology. Although thrombolytic therapy is the most effective way to salvage ischemic brain tissue that has not yet infarcted, there is a narrow window for the use of thrombolytics in the treatment of acute ischemic stroke. As a result, many patients will not be eligible for thrombolysis. Outside of 4.5 hours from symptom onset, evidence suggests that the risk outweighs the benefit of using the thrombolytic alteplase. For patients ineligible for thrombolytic therapy, antiplatelet therapy remains the best choice for treatment.

Medications that prevent blood from coagulating or clotting are used to treat and prevent a recurring or second stroke. Typically, an antiplatelet agent (most often aspirin) is initiated within 48 hours of an ischemic stroke and continued in low doses as maintenance. Multiple studies suggest that antiplatelet therapy can reduce the risk for a second stroke by 25%. Specific anticlotting agents might be warranted in some patients with high-risk conditions for a stroke.

Review of Data

Early initiation of aspirin has shown benefit in the treatment of an acute ischemic stroke. Two major trials—the International Stroke Trial (IST) and the Chinese Acute Stroke Trial (CAST)— evaluated the role of aspirin (see Table 1, p. 15).1,2 The IST and CAST trials showed that roughly nine nonfatal strokes were avoided per every 1,000 early treatments. Taking the endpoint of death, as well as focal deficits, the two trials confirmed a rate of reduction of 13 per 1,000 patients.

Overall, the consensus was that initiating aspirin within 48 hours of a presumed ischemic cerebrovascular accident posed no major risk of hemorrhagic complication and improved the long-term outcomes.

Along with aspirin, other antiplatelet agents have been studied, most commonly dipyridamole and clopidrogel. The EARLY trial demonstrated no significant differences in the aspirin and dipyridamole groups at 90 days.3

Another large trial, which focused on clopidrogel and aspirin, looked at aspirin plus clopidrogel or aspirin alone. The FASTER trial enrolled mostly patients with mild cerebrovasular accidents (CVA) or transient ischemic attacks (TIA), and there was no difference in outcome measures between the groups.4 However, the MATCH trial found that aspirin and clopidrogel did not provide improved stroke preventions versus clopidogrel alone but had a larger risk of hemorrhagic/bleeding complications.5

Aspirin dosage is somewhat controversial. Fewer side effects occur with lower doses. Combining the trials, consensus treatment includes early aspirin dosing (325 mg initially, then 150 mg-325 mg daily) given to patients with ischemic stroke. Early aspirin should be avoided in those patients who qualify for and are receiving alteplase, heparin, or oral warfarin therapy.

There are other antiplatelet agents for long-term management of ischemic stroke. Whereas aspirin alone is used in the early management of acute ischemic stroke in those ineligible for thrombolytic therapy, many patients are transitioned to other antiplatelet strategies for secondary prevention long-term. The number needed to treat for aspirin to reduce one future stroke, myocardial infarction (MI), or vascular death when compared to placebo is quite high at 33. However, the combination of aspirin and dipyradimole does not prevent MI, vascular death, or the combined endpoint of either stroke or death.

Clopidogrel is more effective than aspirin in preventing a combined endpoint of ischemic stroke, MI, or vascular death, but it is not superior to aspirin in preventing recurrent stroke in TIA or stroke patients. The effects of clopidrogel are greater in patients with peripheral arterial disease, previous coronary artery bypass grafting, insulin-dependent diabetes, or recurrent vascular events.

There is a substantially high cost of treatment and long-term disability associated with stroke. Costs can vary from 3% to 5% of the annual healthcare budget. The newer antiplatelet agents are more expensive than aspirin, and overall cost-effectiveness is difficult to estimate. Yet, from an economic standpoint, the combination of aspirin and dipyradimole can be recommended as an alternative for secondary stroke prevention in patients without major comorbidities. In those patients with higher risk factors and/or comorbidities, clopidogrel might be more cost-effective than aspirin alone. Furthermore, in patients with aspirin intolerance, clopidogrel is a useful, but expensive, alternative.

Thrombolytic therapy. Restora-tion of blood flow with thrombolytic therapy is the most effective way of salvaging ischemic brain tissue that has not already infarcted. The window for use of the thrombolytic alteplase is narrow; studies suggest that its benefit diminishes with increasing time to treatment. Indeed, after 4.5 hours from the onset of symptoms, evidence suggests that the harm might outweigh the benefit, so the determination of who is eligible for its use has to be made quickly.

Guidelines published by the American Heart Association/American Stoke Association stroke council outline strict inclusion and exclusion criteria for the use of alteplase in the management of acute ischemic stroke.6 Obtaining informed consent and emergent neuroimaging are vital in preventing delays in alteplase administration.

Two major trials that illustrate the benefit of alteplase in the treatment of acute ischemic stroke are the NINDS trial and the ECASS 3 trial. NINDS showed that when intravenous alteplase was used within three hours of symptom onset, patients had improved functional outcome at three months.7 The ECASS 3 trial showed that intravenous alteplase has benefit when given up to 4.5 hours after symptom onset.8 Treatment with intravenous alteplase from three-4.5 hours in the ECASS 3 trial showed a modest improvement in patient outcomes at three months, with a number needed to treat of 14 for a favorable outcome.

A 2010 meta-analysis looked specifically at outcomes in stroke based on time to treat with alteplase using pooled data from the NINDS, ATLANTIS, ECASS (1, 2, and 3), and EPITHET trials.9 It showed that the number needed to treat for a favorable outcome at three months increased steadily when time to treatment was delayed. It also showed that the risk of death after alteplase administration increased significantly after 4.5 hours. Thus, after 4.5 hours, it suggests that harm might exceed the benefits of treatment.

Anticoagulant use in ischemic stroke. Clinical trials have not been effective in demonstrating the use of heparin and low-molecular-weight heparins (LMWHs). A 2008 systematic review of 24 trials (approximately 24,000 patients) demonstrated:

- Anticoagulant therapy did not reduce odds of death;

- Therapy was associated with nine fewer recurrent ischemic strokes per 1,000 patients, but also showed a similar increase in symptomatic intracranial hemorrhages; and

- Overall, researchers could not specify a particular anticoagulant mode or regimen that had an overall net patient benefit.

The use of heparin in atrial fibrillation and stroke has generated controversy in recent years. Review of the data, however, indicates that early treatment with heparin might cause more harm than benefit. A 2007 meta-analysis did not support the use of early anticoagulant therapy. Seven trials (4,200 patients) compared heparin or LMWH started within 48 hours to other treatments (aspirin, placebo). The study authors found:

- Nonsignificant reduction in recurrent ischemic stroke within seven to 14 days;

- Statistically significant increase in symptomatic intracranial hemorrhages; and

- Similar rates of death/disability at final follow-up of studies.

For those patients who continue to demonstrate neurological deterioration, heparin and LMWH use did not appear to improve outcomes. Therefore, based on a consensus of national guidelines, the use of full-dose anticoagulation with heparin or LMWH is not recommended.

The data suggest that in patients with stroke secondary to:

- Dissection of cervical or intracranial arteries;

- Intracardiac thrombus and valvular disease; and

- Mechanical heart valves, full-dose anticoagulation can be initiated. However, the benefit is unproven.

Back to the Case

Our patient with acute ischemic stroke with right-sided weakness on exam presented outside of the window within which alteplase could be administered safely. She was started on aspirin 325 mg daily. There was no indication for full anticoagulation with intravenous heparin or warfarin. Her weakness showed slight improvement on exam during the hospitalization. As an insulin-dependent diabetic, she was thought to be at high risk for recurrent stroke. As such, she was transitioned to a combination of aspirin and clopidogrel prior to her discharge to an acute inpatient rehabilitation hospital.

Bottom Line

Early aspirin therapy (within 48 hours) is recommended (initial dose 325 mg, then 150 mg-325 mg daily) for patients with ischemic stroke who are not candidates for alteplase, IV heparin, or oral anticoagulants.10 Aspirin is the only antiplatelet agent that has been shown to be effective for the early treatment of acute ischemic stroke. In patients without contraindications, aspirin, the combination of aspirin-dipyradimole, or clopidogrel is appropriate for secondary prevention.

The subset of patients at high risk of recurrent stroke should be transitioned to clopidogrel or aspirin/clopidogrel, unless otherwise contraindicated. TH

Dr. Chaturvedi is an instructor in the Division of Hospital Medicine at Northwestern University’s Feinberg School of Medicine in Chicago, and medical director of HM at Northwestern Lake Forest Hospital. Dr. Abraham is an instructor in the Division of Hospital Medicine at Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine.

References

- The International Stroke Trial (IST): a randomised trial of aspirin, subcutaneous heparin, both, or neither among 19,435 patients with acute ischemic stroke. International Stroke Trial Collaborative Group. Lancet. 1997;349:1569-1581.

- CAST: randomised placebo-controlled trial of early aspirin use in 20,000 patients with acute ischaemic stroke. CAST (Chinese Acute Stroke Trial) Collaborative Group. Lancet. 1997;349:1641-1649.

- Dengler R, Diener HC, Schwartz A, et al. Early treatment with aspirin plus extended-release dipyridamole for transient ischaemic attack or ischaemic stroke within 24 h of symptom onset (EARLY trial): a randomised, open-label, blinded-endpoint trial. Lancet Neurol. 2010;9:159-166.

- Kennedy J, Hill MD, Ryckborst KJ, et al. Fast assessment of stroke and transient ischaemic attack to prevent early recurrence (FASTER): a randomised controlled pilot trial. Lancet Neurol. 2007;6:961-969.

- Diener HC, Bogousslavsky J, Brass LM, et al. Aspirin and clopidogrel compared with clopidogrel alone after recent ischaemic stroke or transient ischaemic attack in high-risk patients (MATCH): randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2004;364:331-337.

- Adams HP Jr, del Zoppo G, Alberts MJ, et al. Guidelines for the early management of adults with ischemic stroke: a guideline from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association Stroke Council, Clinical Cardiology Council, Cardiovascular Radiology and Intervention Council, and the Atherosclerotic Peripheral Vascular Disease and Quality of Care Outcomes in Research Interdisciplinary Working Groups: The American Academy of Neurology affirms the value of this guideline as an educational tool for neurologists. Stroke. 2007;38:1655-1711.

- Lees KR, Bluhmki E, von Kummer R, et al. Time to treatment with intravenous alteplase and outcome in stroke: an updated pooled analysis of ECASS, ATLANTIS, NINDS, and EPITHET trials. Lancet. 2010;375:1695-1703.

- Hacke W, Kaste M, Bluhmki E, et al. Thombolysis with alteplase 3 to 4.5 hours after acute ischemic stroke. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:1317-1329.

- Tissue plasminogen activator for acute ischemic stroke. The National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke rt-PA Stroke Study Group. N Engl J Med. 1995;333:1581-1587.

- Albers GW, Amarenco P, Easton JD, et al. Antithrombotic and thrombolytic therapy for ischemic stroke: American College of Chest Physicians Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guidelines (8th Edition). Chest. 2008;133:630S-669S.

Case

A 58-year-old woman with diabetes mellitus and hypertension presents with dysarthria and weakness on the right side of her body starting six hours prior to presentation. She is afebrile and has a blood pressure of 162/84 mmHg. Exam reveals the absence of a heart murmur and no lower-extremity swelling or calf tenderness. There is weakness of the right side of the body on exam with diminished proprioception. A noncontrast head CT shows no intracranial hemorrhage. She is admitted to the hospital with the diagnosis of acute ischemic stroke. What anticlotting or antiplatelet medications should she receive?

Overview

Stroke remains a significant cause of morbidity and mortality in the U.S. and around the world. The majority of strokes are ischemic in etiology. Although thrombolytic therapy is the most effective way to salvage ischemic brain tissue that has not yet infarcted, there is a narrow window for the use of thrombolytics in the treatment of acute ischemic stroke. As a result, many patients will not be eligible for thrombolysis. Outside of 4.5 hours from symptom onset, evidence suggests that the risk outweighs the benefit of using the thrombolytic alteplase. For patients ineligible for thrombolytic therapy, antiplatelet therapy remains the best choice for treatment.

Medications that prevent blood from coagulating or clotting are used to treat and prevent a recurring or second stroke. Typically, an antiplatelet agent (most often aspirin) is initiated within 48 hours of an ischemic stroke and continued in low doses as maintenance. Multiple studies suggest that antiplatelet therapy can reduce the risk for a second stroke by 25%. Specific anticlotting agents might be warranted in some patients with high-risk conditions for a stroke.

Review of Data

Early initiation of aspirin has shown benefit in the treatment of an acute ischemic stroke. Two major trials—the International Stroke Trial (IST) and the Chinese Acute Stroke Trial (CAST)— evaluated the role of aspirin (see Table 1, p. 15).1,2 The IST and CAST trials showed that roughly nine nonfatal strokes were avoided per every 1,000 early treatments. Taking the endpoint of death, as well as focal deficits, the two trials confirmed a rate of reduction of 13 per 1,000 patients.

Overall, the consensus was that initiating aspirin within 48 hours of a presumed ischemic cerebrovascular accident posed no major risk of hemorrhagic complication and improved the long-term outcomes.

Along with aspirin, other antiplatelet agents have been studied, most commonly dipyridamole and clopidrogel. The EARLY trial demonstrated no significant differences in the aspirin and dipyridamole groups at 90 days.3

Another large trial, which focused on clopidrogel and aspirin, looked at aspirin plus clopidrogel or aspirin alone. The FASTER trial enrolled mostly patients with mild cerebrovasular accidents (CVA) or transient ischemic attacks (TIA), and there was no difference in outcome measures between the groups.4 However, the MATCH trial found that aspirin and clopidrogel did not provide improved stroke preventions versus clopidogrel alone but had a larger risk of hemorrhagic/bleeding complications.5

Aspirin dosage is somewhat controversial. Fewer side effects occur with lower doses. Combining the trials, consensus treatment includes early aspirin dosing (325 mg initially, then 150 mg-325 mg daily) given to patients with ischemic stroke. Early aspirin should be avoided in those patients who qualify for and are receiving alteplase, heparin, or oral warfarin therapy.

There are other antiplatelet agents for long-term management of ischemic stroke. Whereas aspirin alone is used in the early management of acute ischemic stroke in those ineligible for thrombolytic therapy, many patients are transitioned to other antiplatelet strategies for secondary prevention long-term. The number needed to treat for aspirin to reduce one future stroke, myocardial infarction (MI), or vascular death when compared to placebo is quite high at 33. However, the combination of aspirin and dipyradimole does not prevent MI, vascular death, or the combined endpoint of either stroke or death.

Clopidogrel is more effective than aspirin in preventing a combined endpoint of ischemic stroke, MI, or vascular death, but it is not superior to aspirin in preventing recurrent stroke in TIA or stroke patients. The effects of clopidrogel are greater in patients with peripheral arterial disease, previous coronary artery bypass grafting, insulin-dependent diabetes, or recurrent vascular events.

There is a substantially high cost of treatment and long-term disability associated with stroke. Costs can vary from 3% to 5% of the annual healthcare budget. The newer antiplatelet agents are more expensive than aspirin, and overall cost-effectiveness is difficult to estimate. Yet, from an economic standpoint, the combination of aspirin and dipyradimole can be recommended as an alternative for secondary stroke prevention in patients without major comorbidities. In those patients with higher risk factors and/or comorbidities, clopidogrel might be more cost-effective than aspirin alone. Furthermore, in patients with aspirin intolerance, clopidogrel is a useful, but expensive, alternative.

Thrombolytic therapy. Restora-tion of blood flow with thrombolytic therapy is the most effective way of salvaging ischemic brain tissue that has not already infarcted. The window for use of the thrombolytic alteplase is narrow; studies suggest that its benefit diminishes with increasing time to treatment. Indeed, after 4.5 hours from the onset of symptoms, evidence suggests that the harm might outweigh the benefit, so the determination of who is eligible for its use has to be made quickly.

Guidelines published by the American Heart Association/American Stoke Association stroke council outline strict inclusion and exclusion criteria for the use of alteplase in the management of acute ischemic stroke.6 Obtaining informed consent and emergent neuroimaging are vital in preventing delays in alteplase administration.

Two major trials that illustrate the benefit of alteplase in the treatment of acute ischemic stroke are the NINDS trial and the ECASS 3 trial. NINDS showed that when intravenous alteplase was used within three hours of symptom onset, patients had improved functional outcome at three months.7 The ECASS 3 trial showed that intravenous alteplase has benefit when given up to 4.5 hours after symptom onset.8 Treatment with intravenous alteplase from three-4.5 hours in the ECASS 3 trial showed a modest improvement in patient outcomes at three months, with a number needed to treat of 14 for a favorable outcome.

A 2010 meta-analysis looked specifically at outcomes in stroke based on time to treat with alteplase using pooled data from the NINDS, ATLANTIS, ECASS (1, 2, and 3), and EPITHET trials.9 It showed that the number needed to treat for a favorable outcome at three months increased steadily when time to treatment was delayed. It also showed that the risk of death after alteplase administration increased significantly after 4.5 hours. Thus, after 4.5 hours, it suggests that harm might exceed the benefits of treatment.

Anticoagulant use in ischemic stroke. Clinical trials have not been effective in demonstrating the use of heparin and low-molecular-weight heparins (LMWHs). A 2008 systematic review of 24 trials (approximately 24,000 patients) demonstrated:

- Anticoagulant therapy did not reduce odds of death;

- Therapy was associated with nine fewer recurrent ischemic strokes per 1,000 patients, but also showed a similar increase in symptomatic intracranial hemorrhages; and

- Overall, researchers could not specify a particular anticoagulant mode or regimen that had an overall net patient benefit.

The use of heparin in atrial fibrillation and stroke has generated controversy in recent years. Review of the data, however, indicates that early treatment with heparin might cause more harm than benefit. A 2007 meta-analysis did not support the use of early anticoagulant therapy. Seven trials (4,200 patients) compared heparin or LMWH started within 48 hours to other treatments (aspirin, placebo). The study authors found:

- Nonsignificant reduction in recurrent ischemic stroke within seven to 14 days;

- Statistically significant increase in symptomatic intracranial hemorrhages; and

- Similar rates of death/disability at final follow-up of studies.

For those patients who continue to demonstrate neurological deterioration, heparin and LMWH use did not appear to improve outcomes. Therefore, based on a consensus of national guidelines, the use of full-dose anticoagulation with heparin or LMWH is not recommended.

The data suggest that in patients with stroke secondary to:

- Dissection of cervical or intracranial arteries;

- Intracardiac thrombus and valvular disease; and

- Mechanical heart valves, full-dose anticoagulation can be initiated. However, the benefit is unproven.

Back to the Case

Our patient with acute ischemic stroke with right-sided weakness on exam presented outside of the window within which alteplase could be administered safely. She was started on aspirin 325 mg daily. There was no indication for full anticoagulation with intravenous heparin or warfarin. Her weakness showed slight improvement on exam during the hospitalization. As an insulin-dependent diabetic, she was thought to be at high risk for recurrent stroke. As such, she was transitioned to a combination of aspirin and clopidogrel prior to her discharge to an acute inpatient rehabilitation hospital.

Bottom Line

Early aspirin therapy (within 48 hours) is recommended (initial dose 325 mg, then 150 mg-325 mg daily) for patients with ischemic stroke who are not candidates for alteplase, IV heparin, or oral anticoagulants.10 Aspirin is the only antiplatelet agent that has been shown to be effective for the early treatment of acute ischemic stroke. In patients without contraindications, aspirin, the combination of aspirin-dipyradimole, or clopidogrel is appropriate for secondary prevention.

The subset of patients at high risk of recurrent stroke should be transitioned to clopidogrel or aspirin/clopidogrel, unless otherwise contraindicated. TH

Dr. Chaturvedi is an instructor in the Division of Hospital Medicine at Northwestern University’s Feinberg School of Medicine in Chicago, and medical director of HM at Northwestern Lake Forest Hospital. Dr. Abraham is an instructor in the Division of Hospital Medicine at Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine.

References

- The International Stroke Trial (IST): a randomised trial of aspirin, subcutaneous heparin, both, or neither among 19,435 patients with acute ischemic stroke. International Stroke Trial Collaborative Group. Lancet. 1997;349:1569-1581.

- CAST: randomised placebo-controlled trial of early aspirin use in 20,000 patients with acute ischaemic stroke. CAST (Chinese Acute Stroke Trial) Collaborative Group. Lancet. 1997;349:1641-1649.

- Dengler R, Diener HC, Schwartz A, et al. Early treatment with aspirin plus extended-release dipyridamole for transient ischaemic attack or ischaemic stroke within 24 h of symptom onset (EARLY trial): a randomised, open-label, blinded-endpoint trial. Lancet Neurol. 2010;9:159-166.

- Kennedy J, Hill MD, Ryckborst KJ, et al. Fast assessment of stroke and transient ischaemic attack to prevent early recurrence (FASTER): a randomised controlled pilot trial. Lancet Neurol. 2007;6:961-969.

- Diener HC, Bogousslavsky J, Brass LM, et al. Aspirin and clopidogrel compared with clopidogrel alone after recent ischaemic stroke or transient ischaemic attack in high-risk patients (MATCH): randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2004;364:331-337.

- Adams HP Jr, del Zoppo G, Alberts MJ, et al. Guidelines for the early management of adults with ischemic stroke: a guideline from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association Stroke Council, Clinical Cardiology Council, Cardiovascular Radiology and Intervention Council, and the Atherosclerotic Peripheral Vascular Disease and Quality of Care Outcomes in Research Interdisciplinary Working Groups: The American Academy of Neurology affirms the value of this guideline as an educational tool for neurologists. Stroke. 2007;38:1655-1711.

- Lees KR, Bluhmki E, von Kummer R, et al. Time to treatment with intravenous alteplase and outcome in stroke: an updated pooled analysis of ECASS, ATLANTIS, NINDS, and EPITHET trials. Lancet. 2010;375:1695-1703.

- Hacke W, Kaste M, Bluhmki E, et al. Thombolysis with alteplase 3 to 4.5 hours after acute ischemic stroke. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:1317-1329.

- Tissue plasminogen activator for acute ischemic stroke. The National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke rt-PA Stroke Study Group. N Engl J Med. 1995;333:1581-1587.

- Albers GW, Amarenco P, Easton JD, et al. Antithrombotic and thrombolytic therapy for ischemic stroke: American College of Chest Physicians Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guidelines (8th Edition). Chest. 2008;133:630S-669S.