User login

Better late than later: Lessons learned from an investigator-led clinical trial

As a second-year gastroenterology fellow, I designed a prospective, double-blind randomized, controlled trial for vitamin D repletion in patients with Crohn’s disease at a referral inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) center. I had the support of a dedicated research team, several mentors, and a 2-year time frame in which to complete this study. Intellectually curious and academically eager, I labored over a grant application that I did not receive. Under generous financial support from my department, I forged on and opened the trial for enrollment at the start of my advanced IBD fellowship year. However, we experienced recruitment challenges that ultimately led to the study’s premature termination. Through this journey, I gained invaluable experience that will continue to serve me – and, I hope, the reader – as I progress in my career. Below are some important insights gleaned from this experience that may benefit others interested in clinical trial design.

Know your “why” (personally and clinically)

Asked to reflect on their career path, experts tend to recount their “being in the right place at the right time” and having “good mentors.” While luck and good mentorship are necessary, I propose that doing your homework is equally as important. Before ambling down the path of an investigator-led trial, I urge a hard pause to reflect on your “why.” The personal “why” of “getting into fellowship,” “advancement in the department,” or “learning more about the principles of research,” are all valid. But I suggest a deeper dive is in order. Successful clinical trials require resources, a substantial time commitment, lots of sweat and maybe a few tears. In the ideal setting, your trial experience will serve as the foundation for a compelling personal narrative and might help launch a productive clinical research career. With stakes that high, asking the tough questions is critical.

The clinical “why” is just as critical. We press our attendings on why they used this drug or that clip, so don’t be afraid to ask whether this is a space in which others have succeeded. Or conversely, why is there such a large gap in the literature? I remember emailing the world’s expert about my topic because the published data were so murky. He had more questions than answers which, in retrospect, should have raised red flags about the ability to design a sound study. It is equally important to determine if patients are vested in the research question. A successful clinical trial hinges on subject participation, often outside their clinic visit. Patients with complex chronic diseases spend a lot of time navigating the health care system. Participating in a clinical trial needs to be meaningful to them if you want your patients to fully engage. Thoughtfully answering these questions on the front end – for yourself and the study in question – will improve both your experience and the ultimate outcome exponentially.

Identify your village (and listen to them)

Designing a clinical trial truly takes a village, and you need to identify the villagers early. As trainees, the value of mentorship is frequently underscored. But the importance of, and the nuance involved in managing, collaborating, and support cannot be overstated. Meet with a biostatistician to ensure your sample size calculations are correct. Work closely with the research pharmacist to ensure the medication formulation is available; decide on the manner of distribution so as not to inconvenience subjects; create a budget with an experienced manager. Seek out research coordinators often for assistance in creating case report forms, learning appropriate documentation, and crafting responses to Institutional Review Board concerns. Ask clinic personnel about arranging consent or follow-up visits around subjects’ clinic appointments. Present a draft of the protocol to your colleagues, as you will ultimately need them on board to recruit patients. And most importantly, listen to them ... all of them. Get your biases in check and write down all constructive criticism. Thoughtfully address each concern encountered to your satisfaction (and your mentor’s) and present to your village again. Rinse and repeat. Throw nothing under the rug, because if you do, it will eventually rear its head while you are in the throes of the study.

In retrospect, there were concerns raised by faculty and grant reviewers that I did not adequately address. First was the feasibility of screening, recruiting, and enrolling 80 patients during a busy clinical fellowship. While I took this criticism as a reflection of my personal commitment to the project, it was actually a call to consider the impact on clinical (and familial) responsibilities. But as I started enrolling patients, I realized there were logistic issues implied in this suggestion. I could not recruit subjects in Clinic A if I was assigned to see patients at the same time in Clinic B. Patients were not likely to come back another day for study-related discussions. Second, I designed eligibility criteria to make the data as clean as possible. Limiting the study to subjects with Crohn’s disease, in clinical and biochemical remission, without complications of their disease, who also have vitamin deficiency, may be an unrealistic recipe to recruit 80 people in a limited period of time. Finally, I designed laboratory follow-up schedules based on the pharmacokinetics of the drug alone, failing to consider the clinical milieu from which study subjects were recruited. Neglecting the fact that many patients obtain labs with their infusions, my study increased lab draw burden, heaped more patient reminders onto my plate – and more concerning – decreased overall study compliance. In short, trial design cannot be done in a vacuum or by just poring over published data. There are logistical and patient-related considerations that require early input from physicians and clinical staff in order for all the moving parts of a clinical trial to successfully work in harmony.

Create a timetable and follow it

Make a recruitment timetable very early on in the enrollment period. Set up biweekly meetings with mentors to discuss enrollment numbers and reflect on any unforeseen challenges. And be sure to celebrate the wins as well – not matter how small. In our study, falling behind on recruitment goals forced me to amend the stringent eligibility criteria and add additional manpower to help with reminders for laboratory follow-up and patient screening. These pivots caused study delays and cost resources. Ultimately, having a timetable forced me to take pause when it became clear I could not finish the study in the allotted time.

Know when to fold ’em

Knowing when to close a study is far easier said than done. The sunk cost fallacy says it is much harder to abandon a project after investing so many resources into it. For us, it was the recruitment timetable that gave us pause. Finishing trial accrual by the end of my advanced fellowship year was wholly unfeasible. When it became clear that nobody in the department could see it through to completion, I was propelled to terminate the study. If there is concern about termination, I suggest sending the protocol, recruitment numbers, and timeline to an outside colleague for a second, unbiased opinion. Review the already compiled data for any notable findings worthy of a smaller publication. It is said, we often learn more from our failures than our successes. The experience described herein – largely in part to my mentors, collaborators, and the patients who put their faith in me – translates to a lasting, invaluable win.

Mentor’s note

Clinical research is hard. Many trainees meet with me to “get involved” in clinical research, and the challenge as a mentor is to identify a project appropriate to the level of training and provide the infrastructure and resources to facilitate success for the motivated trainee. Trainees have various goals of their involvement in research – to foster a relationship in the hopes of receiving a strong letter of support, to facilitate getting into a competitive training program, and/or to publish. My goal as a mentor is to help my trainees reach their goals, but as a clinical researcher, I look for the trainee’s desire to engage with and learn the research process, with the ancillary potential for a letter, for acceptance to a program, or for publication.

This particular study, a randomized, controlled trial of vitamin D in patients with Crohn’s disease, involved an enormous undertaking by a very motivated trainee who took the project from its inception; to putting a thoughtful grant proposal together; to developing a full clinical trial protocol with its ancillary regulatory documents; and obtaining institutional review board approval, statistician input, pharmacy support, and buy-in from faculty and ancillary staff stakeholders. The study ultimately failed because of low enrollment – patients did not want to participate (for reasons elucidated above) – not because of poor design or execution of the myriad components of a prospective clinical trial. Low enrollment has led to the failure of many otherwise excellent studies, including several in our field of IBD.1,2 As a mentor, it is rational to accept blame for the failure of a trainee project; how could I have better foreseen the outcome of this study? Could this have been prevented with more support, more oversight, or more “micromanagement,” to the potential detriment of fostering independence?

Ultimately, the value of clinical research to trainees is multifaceted. If the goal was a first-author publication with high clinical impact, this trial failed. But if the goal was to learn about the clinical trial process, this study was a resounding success. Ultimately, it behooves trainees and their mentors to engage in early, upfront conversations about research. What are the goals? What does success look like? What if the trial fails? By shifting the focus from the success of the project to the success of the mentorship and educational process, even failed projects are resounding successes, upon which future careers can be further developed.

References

1. Kan S et al. When subjects violate the research covenant: Lessons learned from a failed clinical trial of fecal microbiota transplantation. Am J Gastroenterol 2016;111:1508-10.

2. Dassopoulos T et al. Randomised clinical trial: Individualised vs.weight-based dosing of azathioprine in Crohn’s disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2014 Jan;39(2):163-75.

Dr. Cohen is an inflammatory bowel disease fellow, inflammatory bowel disease center, division of gastroenterology and hepatology, department of medicine, Cedars-Sinai Medical Center, Los Angeles. Dr. Melmed is director, inflammatory bowel disease clinical research and codirector, clinical inflammatory bowel disease, inflammatory bowel disease center, division of gastroenterology and hepatology, department of medicine, Cedars-Sinai Medical Center, Los Angeles.

As a second-year gastroenterology fellow, I designed a prospective, double-blind randomized, controlled trial for vitamin D repletion in patients with Crohn’s disease at a referral inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) center. I had the support of a dedicated research team, several mentors, and a 2-year time frame in which to complete this study. Intellectually curious and academically eager, I labored over a grant application that I did not receive. Under generous financial support from my department, I forged on and opened the trial for enrollment at the start of my advanced IBD fellowship year. However, we experienced recruitment challenges that ultimately led to the study’s premature termination. Through this journey, I gained invaluable experience that will continue to serve me – and, I hope, the reader – as I progress in my career. Below are some important insights gleaned from this experience that may benefit others interested in clinical trial design.

Know your “why” (personally and clinically)

Asked to reflect on their career path, experts tend to recount their “being in the right place at the right time” and having “good mentors.” While luck and good mentorship are necessary, I propose that doing your homework is equally as important. Before ambling down the path of an investigator-led trial, I urge a hard pause to reflect on your “why.” The personal “why” of “getting into fellowship,” “advancement in the department,” or “learning more about the principles of research,” are all valid. But I suggest a deeper dive is in order. Successful clinical trials require resources, a substantial time commitment, lots of sweat and maybe a few tears. In the ideal setting, your trial experience will serve as the foundation for a compelling personal narrative and might help launch a productive clinical research career. With stakes that high, asking the tough questions is critical.

The clinical “why” is just as critical. We press our attendings on why they used this drug or that clip, so don’t be afraid to ask whether this is a space in which others have succeeded. Or conversely, why is there such a large gap in the literature? I remember emailing the world’s expert about my topic because the published data were so murky. He had more questions than answers which, in retrospect, should have raised red flags about the ability to design a sound study. It is equally important to determine if patients are vested in the research question. A successful clinical trial hinges on subject participation, often outside their clinic visit. Patients with complex chronic diseases spend a lot of time navigating the health care system. Participating in a clinical trial needs to be meaningful to them if you want your patients to fully engage. Thoughtfully answering these questions on the front end – for yourself and the study in question – will improve both your experience and the ultimate outcome exponentially.

Identify your village (and listen to them)

Designing a clinical trial truly takes a village, and you need to identify the villagers early. As trainees, the value of mentorship is frequently underscored. But the importance of, and the nuance involved in managing, collaborating, and support cannot be overstated. Meet with a biostatistician to ensure your sample size calculations are correct. Work closely with the research pharmacist to ensure the medication formulation is available; decide on the manner of distribution so as not to inconvenience subjects; create a budget with an experienced manager. Seek out research coordinators often for assistance in creating case report forms, learning appropriate documentation, and crafting responses to Institutional Review Board concerns. Ask clinic personnel about arranging consent or follow-up visits around subjects’ clinic appointments. Present a draft of the protocol to your colleagues, as you will ultimately need them on board to recruit patients. And most importantly, listen to them ... all of them. Get your biases in check and write down all constructive criticism. Thoughtfully address each concern encountered to your satisfaction (and your mentor’s) and present to your village again. Rinse and repeat. Throw nothing under the rug, because if you do, it will eventually rear its head while you are in the throes of the study.

In retrospect, there were concerns raised by faculty and grant reviewers that I did not adequately address. First was the feasibility of screening, recruiting, and enrolling 80 patients during a busy clinical fellowship. While I took this criticism as a reflection of my personal commitment to the project, it was actually a call to consider the impact on clinical (and familial) responsibilities. But as I started enrolling patients, I realized there were logistic issues implied in this suggestion. I could not recruit subjects in Clinic A if I was assigned to see patients at the same time in Clinic B. Patients were not likely to come back another day for study-related discussions. Second, I designed eligibility criteria to make the data as clean as possible. Limiting the study to subjects with Crohn’s disease, in clinical and biochemical remission, without complications of their disease, who also have vitamin deficiency, may be an unrealistic recipe to recruit 80 people in a limited period of time. Finally, I designed laboratory follow-up schedules based on the pharmacokinetics of the drug alone, failing to consider the clinical milieu from which study subjects were recruited. Neglecting the fact that many patients obtain labs with their infusions, my study increased lab draw burden, heaped more patient reminders onto my plate – and more concerning – decreased overall study compliance. In short, trial design cannot be done in a vacuum or by just poring over published data. There are logistical and patient-related considerations that require early input from physicians and clinical staff in order for all the moving parts of a clinical trial to successfully work in harmony.

Create a timetable and follow it

Make a recruitment timetable very early on in the enrollment period. Set up biweekly meetings with mentors to discuss enrollment numbers and reflect on any unforeseen challenges. And be sure to celebrate the wins as well – not matter how small. In our study, falling behind on recruitment goals forced me to amend the stringent eligibility criteria and add additional manpower to help with reminders for laboratory follow-up and patient screening. These pivots caused study delays and cost resources. Ultimately, having a timetable forced me to take pause when it became clear I could not finish the study in the allotted time.

Know when to fold ’em

Knowing when to close a study is far easier said than done. The sunk cost fallacy says it is much harder to abandon a project after investing so many resources into it. For us, it was the recruitment timetable that gave us pause. Finishing trial accrual by the end of my advanced fellowship year was wholly unfeasible. When it became clear that nobody in the department could see it through to completion, I was propelled to terminate the study. If there is concern about termination, I suggest sending the protocol, recruitment numbers, and timeline to an outside colleague for a second, unbiased opinion. Review the already compiled data for any notable findings worthy of a smaller publication. It is said, we often learn more from our failures than our successes. The experience described herein – largely in part to my mentors, collaborators, and the patients who put their faith in me – translates to a lasting, invaluable win.

Mentor’s note

Clinical research is hard. Many trainees meet with me to “get involved” in clinical research, and the challenge as a mentor is to identify a project appropriate to the level of training and provide the infrastructure and resources to facilitate success for the motivated trainee. Trainees have various goals of their involvement in research – to foster a relationship in the hopes of receiving a strong letter of support, to facilitate getting into a competitive training program, and/or to publish. My goal as a mentor is to help my trainees reach their goals, but as a clinical researcher, I look for the trainee’s desire to engage with and learn the research process, with the ancillary potential for a letter, for acceptance to a program, or for publication.

This particular study, a randomized, controlled trial of vitamin D in patients with Crohn’s disease, involved an enormous undertaking by a very motivated trainee who took the project from its inception; to putting a thoughtful grant proposal together; to developing a full clinical trial protocol with its ancillary regulatory documents; and obtaining institutional review board approval, statistician input, pharmacy support, and buy-in from faculty and ancillary staff stakeholders. The study ultimately failed because of low enrollment – patients did not want to participate (for reasons elucidated above) – not because of poor design or execution of the myriad components of a prospective clinical trial. Low enrollment has led to the failure of many otherwise excellent studies, including several in our field of IBD.1,2 As a mentor, it is rational to accept blame for the failure of a trainee project; how could I have better foreseen the outcome of this study? Could this have been prevented with more support, more oversight, or more “micromanagement,” to the potential detriment of fostering independence?

Ultimately, the value of clinical research to trainees is multifaceted. If the goal was a first-author publication with high clinical impact, this trial failed. But if the goal was to learn about the clinical trial process, this study was a resounding success. Ultimately, it behooves trainees and their mentors to engage in early, upfront conversations about research. What are the goals? What does success look like? What if the trial fails? By shifting the focus from the success of the project to the success of the mentorship and educational process, even failed projects are resounding successes, upon which future careers can be further developed.

References

1. Kan S et al. When subjects violate the research covenant: Lessons learned from a failed clinical trial of fecal microbiota transplantation. Am J Gastroenterol 2016;111:1508-10.

2. Dassopoulos T et al. Randomised clinical trial: Individualised vs.weight-based dosing of azathioprine in Crohn’s disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2014 Jan;39(2):163-75.

Dr. Cohen is an inflammatory bowel disease fellow, inflammatory bowel disease center, division of gastroenterology and hepatology, department of medicine, Cedars-Sinai Medical Center, Los Angeles. Dr. Melmed is director, inflammatory bowel disease clinical research and codirector, clinical inflammatory bowel disease, inflammatory bowel disease center, division of gastroenterology and hepatology, department of medicine, Cedars-Sinai Medical Center, Los Angeles.

As a second-year gastroenterology fellow, I designed a prospective, double-blind randomized, controlled trial for vitamin D repletion in patients with Crohn’s disease at a referral inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) center. I had the support of a dedicated research team, several mentors, and a 2-year time frame in which to complete this study. Intellectually curious and academically eager, I labored over a grant application that I did not receive. Under generous financial support from my department, I forged on and opened the trial for enrollment at the start of my advanced IBD fellowship year. However, we experienced recruitment challenges that ultimately led to the study’s premature termination. Through this journey, I gained invaluable experience that will continue to serve me – and, I hope, the reader – as I progress in my career. Below are some important insights gleaned from this experience that may benefit others interested in clinical trial design.

Know your “why” (personally and clinically)

Asked to reflect on their career path, experts tend to recount their “being in the right place at the right time” and having “good mentors.” While luck and good mentorship are necessary, I propose that doing your homework is equally as important. Before ambling down the path of an investigator-led trial, I urge a hard pause to reflect on your “why.” The personal “why” of “getting into fellowship,” “advancement in the department,” or “learning more about the principles of research,” are all valid. But I suggest a deeper dive is in order. Successful clinical trials require resources, a substantial time commitment, lots of sweat and maybe a few tears. In the ideal setting, your trial experience will serve as the foundation for a compelling personal narrative and might help launch a productive clinical research career. With stakes that high, asking the tough questions is critical.

The clinical “why” is just as critical. We press our attendings on why they used this drug or that clip, so don’t be afraid to ask whether this is a space in which others have succeeded. Or conversely, why is there such a large gap in the literature? I remember emailing the world’s expert about my topic because the published data were so murky. He had more questions than answers which, in retrospect, should have raised red flags about the ability to design a sound study. It is equally important to determine if patients are vested in the research question. A successful clinical trial hinges on subject participation, often outside their clinic visit. Patients with complex chronic diseases spend a lot of time navigating the health care system. Participating in a clinical trial needs to be meaningful to them if you want your patients to fully engage. Thoughtfully answering these questions on the front end – for yourself and the study in question – will improve both your experience and the ultimate outcome exponentially.

Identify your village (and listen to them)

Designing a clinical trial truly takes a village, and you need to identify the villagers early. As trainees, the value of mentorship is frequently underscored. But the importance of, and the nuance involved in managing, collaborating, and support cannot be overstated. Meet with a biostatistician to ensure your sample size calculations are correct. Work closely with the research pharmacist to ensure the medication formulation is available; decide on the manner of distribution so as not to inconvenience subjects; create a budget with an experienced manager. Seek out research coordinators often for assistance in creating case report forms, learning appropriate documentation, and crafting responses to Institutional Review Board concerns. Ask clinic personnel about arranging consent or follow-up visits around subjects’ clinic appointments. Present a draft of the protocol to your colleagues, as you will ultimately need them on board to recruit patients. And most importantly, listen to them ... all of them. Get your biases in check and write down all constructive criticism. Thoughtfully address each concern encountered to your satisfaction (and your mentor’s) and present to your village again. Rinse and repeat. Throw nothing under the rug, because if you do, it will eventually rear its head while you are in the throes of the study.

In retrospect, there were concerns raised by faculty and grant reviewers that I did not adequately address. First was the feasibility of screening, recruiting, and enrolling 80 patients during a busy clinical fellowship. While I took this criticism as a reflection of my personal commitment to the project, it was actually a call to consider the impact on clinical (and familial) responsibilities. But as I started enrolling patients, I realized there were logistic issues implied in this suggestion. I could not recruit subjects in Clinic A if I was assigned to see patients at the same time in Clinic B. Patients were not likely to come back another day for study-related discussions. Second, I designed eligibility criteria to make the data as clean as possible. Limiting the study to subjects with Crohn’s disease, in clinical and biochemical remission, without complications of their disease, who also have vitamin deficiency, may be an unrealistic recipe to recruit 80 people in a limited period of time. Finally, I designed laboratory follow-up schedules based on the pharmacokinetics of the drug alone, failing to consider the clinical milieu from which study subjects were recruited. Neglecting the fact that many patients obtain labs with their infusions, my study increased lab draw burden, heaped more patient reminders onto my plate – and more concerning – decreased overall study compliance. In short, trial design cannot be done in a vacuum or by just poring over published data. There are logistical and patient-related considerations that require early input from physicians and clinical staff in order for all the moving parts of a clinical trial to successfully work in harmony.

Create a timetable and follow it

Make a recruitment timetable very early on in the enrollment period. Set up biweekly meetings with mentors to discuss enrollment numbers and reflect on any unforeseen challenges. And be sure to celebrate the wins as well – not matter how small. In our study, falling behind on recruitment goals forced me to amend the stringent eligibility criteria and add additional manpower to help with reminders for laboratory follow-up and patient screening. These pivots caused study delays and cost resources. Ultimately, having a timetable forced me to take pause when it became clear I could not finish the study in the allotted time.

Know when to fold ’em

Knowing when to close a study is far easier said than done. The sunk cost fallacy says it is much harder to abandon a project after investing so many resources into it. For us, it was the recruitment timetable that gave us pause. Finishing trial accrual by the end of my advanced fellowship year was wholly unfeasible. When it became clear that nobody in the department could see it through to completion, I was propelled to terminate the study. If there is concern about termination, I suggest sending the protocol, recruitment numbers, and timeline to an outside colleague for a second, unbiased opinion. Review the already compiled data for any notable findings worthy of a smaller publication. It is said, we often learn more from our failures than our successes. The experience described herein – largely in part to my mentors, collaborators, and the patients who put their faith in me – translates to a lasting, invaluable win.

Mentor’s note

Clinical research is hard. Many trainees meet with me to “get involved” in clinical research, and the challenge as a mentor is to identify a project appropriate to the level of training and provide the infrastructure and resources to facilitate success for the motivated trainee. Trainees have various goals of their involvement in research – to foster a relationship in the hopes of receiving a strong letter of support, to facilitate getting into a competitive training program, and/or to publish. My goal as a mentor is to help my trainees reach their goals, but as a clinical researcher, I look for the trainee’s desire to engage with and learn the research process, with the ancillary potential for a letter, for acceptance to a program, or for publication.

This particular study, a randomized, controlled trial of vitamin D in patients with Crohn’s disease, involved an enormous undertaking by a very motivated trainee who took the project from its inception; to putting a thoughtful grant proposal together; to developing a full clinical trial protocol with its ancillary regulatory documents; and obtaining institutional review board approval, statistician input, pharmacy support, and buy-in from faculty and ancillary staff stakeholders. The study ultimately failed because of low enrollment – patients did not want to participate (for reasons elucidated above) – not because of poor design or execution of the myriad components of a prospective clinical trial. Low enrollment has led to the failure of many otherwise excellent studies, including several in our field of IBD.1,2 As a mentor, it is rational to accept blame for the failure of a trainee project; how could I have better foreseen the outcome of this study? Could this have been prevented with more support, more oversight, or more “micromanagement,” to the potential detriment of fostering independence?

Ultimately, the value of clinical research to trainees is multifaceted. If the goal was a first-author publication with high clinical impact, this trial failed. But if the goal was to learn about the clinical trial process, this study was a resounding success. Ultimately, it behooves trainees and their mentors to engage in early, upfront conversations about research. What are the goals? What does success look like? What if the trial fails? By shifting the focus from the success of the project to the success of the mentorship and educational process, even failed projects are resounding successes, upon which future careers can be further developed.

References

1. Kan S et al. When subjects violate the research covenant: Lessons learned from a failed clinical trial of fecal microbiota transplantation. Am J Gastroenterol 2016;111:1508-10.

2. Dassopoulos T et al. Randomised clinical trial: Individualised vs.weight-based dosing of azathioprine in Crohn’s disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2014 Jan;39(2):163-75.

Dr. Cohen is an inflammatory bowel disease fellow, inflammatory bowel disease center, division of gastroenterology and hepatology, department of medicine, Cedars-Sinai Medical Center, Los Angeles. Dr. Melmed is director, inflammatory bowel disease clinical research and codirector, clinical inflammatory bowel disease, inflammatory bowel disease center, division of gastroenterology and hepatology, department of medicine, Cedars-Sinai Medical Center, Los Angeles.

Making a case for patient-reported outcomes in clinical inflammatory bowel disease practice

Patients seek medical care when they perceive a deterioration in their health. Gastroenterologists and health care providers are trained to seek out clinical, laboratory, radiologic, and endoscopic evidence of pathology. Conventional endpoints in inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) clinical trials and clinical care may fail to capture the full health status and disease experience from the patient perspective. The Food and Drug Administration has called for the development of coprimary endpoints in research trials to include an objective measure of inflammation in conjunction with patient-reported outcomes (PROs). The objective is to support labeling claims and improve safety and effectiveness in the drug approval process.1,2 There is also growing recognition that high-value care includes management of biologic and psychosocial factors to enable patients with chronic diseases to regain their health. Clinicians might follow suit by incorporating valid, reliable PRO measures to usual IBD care in order better to achieve patient-centered care, inform decision making, and improve the care provided.

What are patient-reported outcomes?

The FDA defines a PRO as “any report of the status of a patient’s health condition that comes directly from the patient, without interpretation of the patient’s response by a clinician or anyone else.” Two PROs are used to measure various aspects of health including physical, emotional, or social domains. PROs have emerged as tools that may foster a better understanding of the patient’s condition, which may go beyond disease activity or symptoms. In effect, incorporating PROs into clinical practice enables a model of “coproduction” of health care, and may contribute to a more reciprocal patient-provider interaction where the needs of the patient may be more fully understood and incorporated into decision-making that may lead to improved patient satisfaction and outcomes.3,4

There are hundreds of available PROs in gastroenterology,5 ranging from simple (characterizing pain with a basic numeric rating scale) to complex multidomain, multi-item instruments. PROs may cover symptom assessment, health-related quality of life, and adherence to and satisfaction with treatment, and may be generic or disease specific. Numerous PROs have been developed for patients with IBD. Commonly used PROs in IBD include severity scales for pain, defecatory urgency, and bloody stool, and several disease-specific and generic instruments assessing different health-related quality-of-life domains have been used in research studies for patients with IBD.

The current approach to patient-centered care for IBD is limited

IBD is a difficult disease to manage – in part because there is no known biomarker that accurately reflects the full spectrum of disease activity. Numerous indices have been developed to better quantify disease activity and measure response to treatment. Among the most frequently used indices in clinical trials are the Crohn’s Disease Activity Index (CDAI) and (for ulcerative colitis [UC]) the Mayo Clinic Score. These endpoints incorporate signs and symptoms, laboratory findings (in the CDAI), and endoscopic assessments. The CDAI is a suboptimal instrument because of a lack of correlation with endoscopic inflammation and potential confounding with concomitant gastrointestinal illnesses, such as irritable bowel syndrome.6 The Mayo Clinic Score is difficult to interpret because of some subjective elements (what is considered a normal number of stools per day?); vagueness (mostly bloody stools more than half the time?); and need for a physician assessment, which often does not correspond with the patient’s perception of their disease.7 From a research perspective, this disconnect can compromise the quality of trial data. Clinically, it can negatively impact patients’ satisfaction and impair the patient-provider relationship.8

To that end, regulatory agencies, scientific bodies, and health care payors are shifting toward a more “patient-centered” approach with an emphasis on PROs. However, although the FDA is incorporating the patient perspective in its trials, measuring meaningful outcomes in day-to-day clinical care is challenging. In the absence of active inflammation, more than 30% of patients with IBD still suffer from gastrointestinal symptoms.9 Furthermore, physicians frequently underestimate the effect of depression, anxiety, fatigue, and sleep on patient health. Likewise, some patients with active small-bowel Crohn’s disease (CD) may experience few gastrointestinal symptoms but have profound fatigue, weight loss, and impaired quality of life. A focused assessment for disease activity may fail to identify aspects of health most relevant or important to individual patient well-being. There is a need for effective, efficient, and standardized strategies to better understand the concerns of the individual seeking help.

Although there are several PROs that measure disease activity primarily for clinical research trials,10 their prevalence in gastroenterology practices has not been assessed. Most likely, few clinical practices currently integrate standardized PROs in routine patient care. This may be because of several reasons, including lack of awareness of newly developed PROs, administrative burden including time and resources to collect PROs, potentially complex interpretation of results, and perhaps a reluctance among physicians to alter traditional patient interview methods of obtaining information about the health status of their patients. For effective use in clinical care, PROs require simple and relevant interpretation to add value to the clinician’s practice, and must minimally impact clinical flow and resources. The use of Internet-enabled tablets has been shown to be a feasible, efficient, and effective means of PRO assessment in gastroenterology practices, with good levels of patient satisfaction.11

Reaping potential benefits of patient-reported outcomes

The National Institutes of Health Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) is an initiative developed to investigate and promote implementation of PRO measures among patients with chronic diseases. The collection of PROMIS measures has been shown to be feasible at a tertiary care IBD center, enabling a biopsychosocial model of care.12 Likewise, implementation of PROs in other clinical areas including oncology, orthopedics, and rheumatology has been robust.

In an innovative orthopedic study, PROMIS measures collected and linked to the electronic medical record predicted the likelihood of a clinically meaningful benefit from foot and ankle surgery.13 This facilitated tailored patient-specific preoperative discussions about the expected benefit of surgery. In a study at a rheumatology clinic patients with rheumatoid arthritis were asked to identify their highest priority treatment targets using PROMIS domains (fatigue, pain, depression, social function). The highest priority domain was tracked over time as a patient-centered marker of health, essentially personalizing measures of success for the individual patient.14

PROs have the unique potential to affect multiple levels of health care. At the patient level, PRO data can identify specific concerns, manage expectations of recovery, and tailor treatment decisions to personal preference. At the population level, PRO data can be used to standardize aspects of care to understand comparative health and disease among all patients in a practice or relative to outside practices, identify outliers, and drive improvement.

Optimizing PROs for use in clinical trials: CD–PROs and UC–PROs

Developing standardized, validated instruments according to FDA guidance is a complex process. The lack of an FDA-approved PRO has resulted in substantial variability in the definitions of clinical response or remission in clinical trials to date.15 As a result, IBD-specific PROs (CD-PRO and UC-PRO) are being developed under FDA guidance for use in clinical trials.16 With achievement of prequalification for open use, UC-PRO and CD-PRO will cover five IBD-specific outcomes domains or modules: 1) bowel signs and symptoms, 2) systemic symptoms, 3) emotional impact, 4) coping behaviors, and 5) IBD impact on daily life. The bowel signs and symptoms module may also incorporate a functional impact assessment. Each module includes numerous pertinent items (e.g., “I feel worried,” “I feel scared,” “I feel alone” in the emotional impact module) and are currently being tailored and scored for practicality and relevance. It is hoped that UC-PRO and CD-PRO in final form will be relevant and applicable for clinical trials and gastroenterology practices alike.

Because the development of the UC-PRO and the CD-PRO is still underway, interim PROs are being used in ongoing clinical trials. These interim measures were extracted from existing components of the CDAI, Mayo Clinic Score, and UC Disease Activity Index. The CD PRO-2 consists of two items: abdominal pain and stool frequency. The UC PRO-2 is composed of rectal bleeding and stool frequency. The PRO-3 adds an item regarding general well-being. The sensitivity of these PROs was tested in studies for CD and UC. Both PROs performed similarly to their respective parent instrument. Important limitations include the lack of validation, and the fact that these interim measures were derived from parent measures with acknowledged limitations as previously discussed. Current clinical trials are coupling these interim measures with endoscopic data as coprimary endpoints.

PROs in routine clinical practice: Are we ready for prime time?

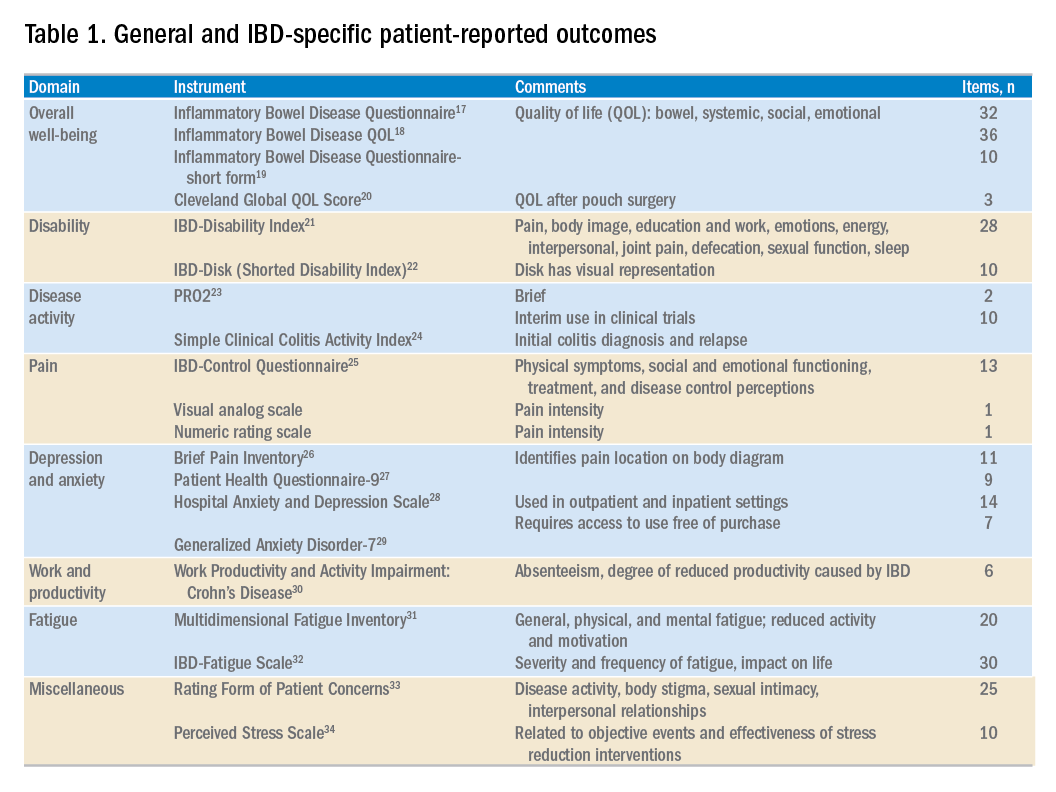

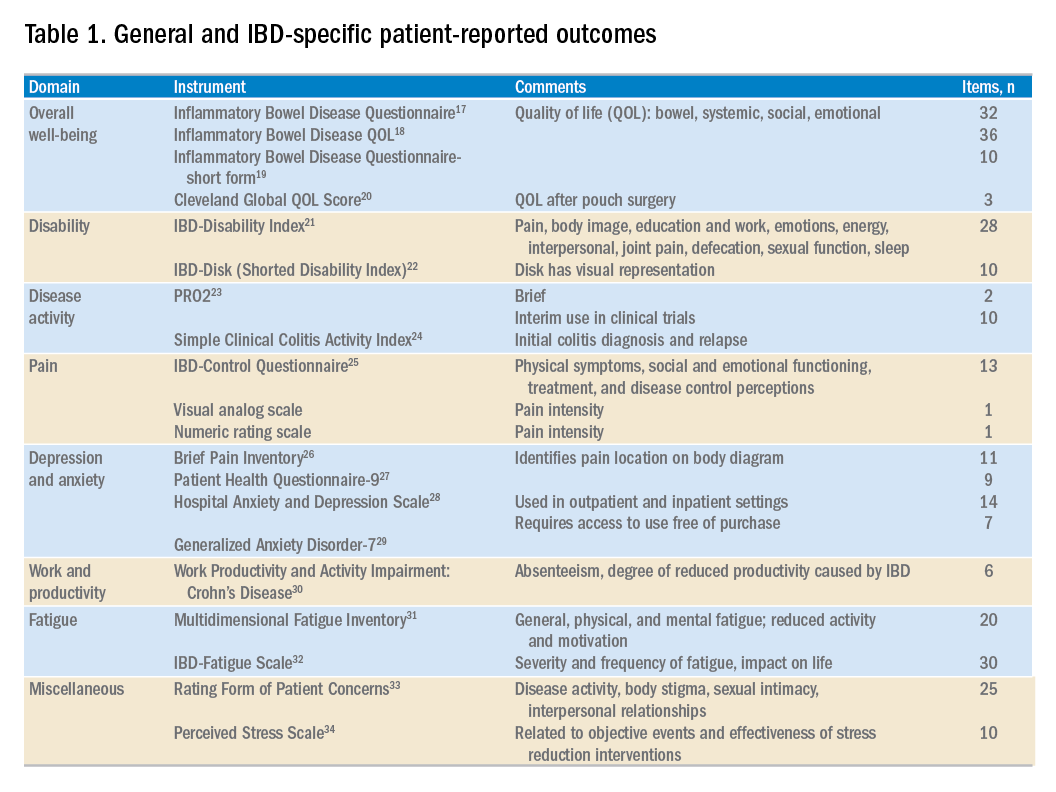

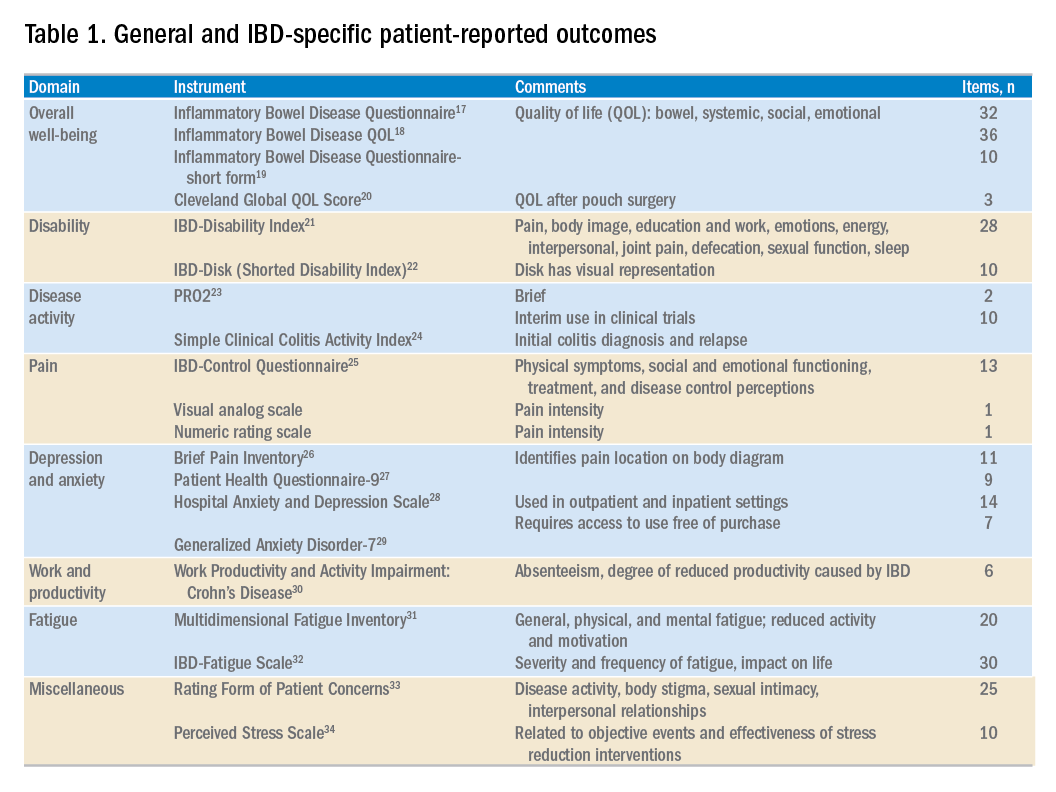

Few instruments developed to date have been widely implemented into routine IBD clinical practice. Table 1 highlights commonly available or recently developed PROs for IBD care. As clinicians strive to more effectively integrate PROs into clinical practice, we propose a three-step process to getting started: 1) select and administer a PRO instrument, 2) identify areas of impairment and create a targeted treatment strategy to focus on those areas, and 3) repeat the same PRO at follow-up to assess for improvement. The instrument can be administered before the visit or in the clinic waiting room. Focus a portion of the patient’s visit on discussing the results and identifying one or more domains to target for improvement. For example, the patient may indicate diarrhea as his/her most important area to target, triggering a symptom-specific investigation and therapeutic approach. The PRO may also highlight social or emotional impairment that may require an ancillary referral. The benefits of this PRO-driven approach to IBD care are twofold. First, the patient’s primary concerns are positioned at the forefront of the clinical visit. Second, aligning the clinician’s focus with the patient input may actually help to streamline each visit and improve overall visit efficiency and patient satisfaction.

Conclusions

As therapies for IBD improve, so should standards of patient-centered care. Clinicians must actively seek and then listen to the concerns of patients and be able to address the multiple facets of living with a chronic disease. PROs empower patients, helping them identify important topics for discussion at the clinical visit. This affords clinicians a better understanding of primary patient concerns before the visit, and potentially improves the quality and value of care. At first, the process of incorporating PROs into a busy clinical practice may be challenging, but targeted treatment plans have the potential to foster a better patient – and physician – experience.

Content from this column was originally published in the “Practice Management: The Road Ahead” section of Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology (2018;16[5]:603-7).

References

1. Guidance for industry: patient-reported outcome measures: use in medical product development to support labeling claims: draft guidance. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2006;4:79.

2. Burke, L.B., Kennedy, D.L., Miskala, P.H., et al. The use of patient-reported outcome measures in the evaluation of medical products for regulatory approval. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2008;84:281-3.

3. Batalden, M., Baltalden, P., Margolis, P., et al. Coproduction of healthcare service. BMJ Qual Saf. 2016;25:509-17.

4. Johnson, L.C. Melmed, G.Y., Nelson, E.C., et al. Fostering collaboration through creation of an IBD learning health system. Am J Gastroenterol. 2017;112:406-8.

5. Khanna, P., Agarwal, N., Khanna, D., et al. Development of an online library of patient reported outcome measures in gastroenterology: the GI-PRO database. Am J Gastroenterol. 2014;109:234-48.

6. Bruining, D.H. Sandborn, W.J. Do not assume symptoms indicate failure of anti-tumor necrosis factor therapy in January 2015 Emerging Treatment Goals in IBD Trials and Practice 45 REVIEWS AND PERSPECTIVES Crohn’s disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;9:395-9.

7. Surti, B., Spiegel, B., Ippoliti, A., et al. Assessing health status in inflammatory bowel disease using a novel single-item numeric rating scale. Dig Dis Sci. 2013;58:1313-21.

8. Marshall, S., Haywood, K. Fitzpatrick R. Impact of patient-reported outcome measures on routine practice: a structured review. J Eval Clin Pract. 2006;12:559-68.

9. Simren, M., Axelsson, J., Gillberg, R., et al. Quality of life in inflammatory bowel disease in remission: the impact of IBD-like symptoms and associated psychological factors. Am J Gastroenterol. 2002;97:389-96.

10. De Jong, M.J., Huibregtse, R., Masclee, A.A.M., et al. Patient-reported outcome measures for use in clinical trials and clinical practice in inflammatory bowel diseases: a systematic review. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;16:648-63.

11. Atreja, A., Rizk, M. Capturing patient reported outcomes and quality of life in routine clinical practice: ready to prime time? Minerva Gastroenterol Dietol. 2012;58:19-24.

12. Ishak, W.W., Pan, D., Steiner, A.J., et al. Patient reported outcomes of quality of life, functioning, and GI/psychiatric symptom severity in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2017;23:798-803.

13. Ho, B., Houck, J.R., Flemister, A.S., et al. Preoperative PROMIS scores predict postoperative success in foot and ankle patients. Foot Ankle Int. 2016;37:911-8. 14. Bacalao, E., Greene, G.J., Beaumont, J.L., et al. Standardizing and personalizing the treat to target (T2T) approach for rheumatoid arthritis using the Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS): baseline findings on patient-centered treatment priorities. Clin Rheumatol. 2017;36:1729-36.

15. Ma, C., Panaccione, R., Fedorak, R.N., et al. Heterogeneity in definitions of endpoints for clinical trials of ulcerative colitis: a systematic review for development of a core outcome set. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;16:637-47.

16. Higgins P. Patient reported outcomes in IBD 2017. Available at: ibdctworkshop.files.wordpress.com/2017/01/patient-reported-outcomes-in-ibd___peter-higgins.pdf. Accessed Aug. 27, 2017.

17. Guyatt, G., Mitchell, A. Irvine, E.J., et al. A new measure of health status for clinical trials in inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterology. 1989;96:804-10.

18. Love, J.R., Irvine, E.J., Fedorak, R.N. Quality of life in inflammatory bowel disease. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1992;14:15-9.

19. Irvine, E.J., Zhou, Q., Thompson, A.K. The short inflammatory bowel disease questionnaire: a quality of life instrument for community physicians managing inflammatory bowel disease. CCRPT investigators. Canadian Crohn’s Relapse Prevention Trial. Am J Gastroenterol. 1996;91:1571-8.

20. Fazio, V.W., O’Riordain, M.G., Lavery, I.C., et al. Long-term functional outcome and quality of life after stapled restorative proctocolectomy. Ann Surg. 1999;230:575-84.

21. Gower-Rousseau, C., Sarter, H., Savoye, G., et al. Validation of the inflammatory bowel disease disability index in a population-based cohort. Gut. 2017;66:588-96.

22. Gosh, S., Louis, E., Beaugerie, L., et al. Development of the IBD-Disk: a visual self-administered tool assessing disability in inflammatory bowel diseases. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2017;23:333-40.

23. Khanna, R., Zou, G., D’Haens, G., et al. A retrospective analysis: the development of patient reported outcome measures for the assessment of Crohn’s disease activity. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2015;41:77-86.

24. Walmsley, R.S., Ayres, R.C.S., Pounder, P.R., et al. A simple clinical colitis activity index. Gut. 1998;43:29-32.

25. Bodger, K., Ormerod, C., Shackcloth, D., et al. Development and validation of a rapid, general measure of disease control from the patient perspective: the IBD-Control questionnaire. Gut. 2014;63:1092-102.

26. Cleeland, C.S., Ryan, K.M. Pain assessment: global use of the Brief Pain Inventory. Ann Acad Med Singapore. 1994;23:129-38.

27. Kroenke, K., Spitzer, R.L., Williams, J.B.W. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16:606-13.

28. Zigmond, A.S., Snaith, R.P. The Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1983;67:361-70.

29. Spitzer, R.L., Korneke, K., Williams, J.B., et al. A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: the GAD-7. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166:1092-7.

30. Reilly, M.C., Zbrozek, A.S. Dukes, E.M. The validity and reproducibility of a work productivity and activity impairment instrument. Pharmachoeconomics. 1993;4:353-65.

31. Smets, E.M., Garssen, B. Bonke, B., et al. The Multidimensional Fatigue Inventory psychometric qualities of an instrument to assess fatigue. J Psychosom Res. 1995;39:315-25.

32. Czuber-Dochan, W., Norton, C., Bassettt, P., et al. Development and psychometric testing of inflammatory bowel disease fatigue (IBD-F) patient self-assessment scale. J Crohns Colitis. 2014;8:1398-406.

33. Drossman, D.A., Leserman, J., Li, Z.M., et al. The rating form of IBD patient concerns: a new measure of health status. Psychosom Med. 1991;53:701-12. 34. Cohen, S., Kamarck, T., Mermelstein, R. A global measure of perceived stress. J Health Soc Behav. 1983;24:385-96.

Dr. Cohen is in the division of digestive and liver diseases; Dr. Melmed is director, clinical inflammatory bowel disease, director, clinical research in the division of gastroenterology, and director, advanced inflammatory bowel disease fellowship program, Cedars-Sinai Medical Center, Los Angeles. Dr. Melmed is a consultant for AbbVie, Boehringer Ingelheim, Celgene, Genentech, Janssen, Pfizer, Samsung Bioepis, Takeda, and UCB; and received support for research from Prometheus Labs. The remaining author discloses no conflicts.

Patients seek medical care when they perceive a deterioration in their health. Gastroenterologists and health care providers are trained to seek out clinical, laboratory, radiologic, and endoscopic evidence of pathology. Conventional endpoints in inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) clinical trials and clinical care may fail to capture the full health status and disease experience from the patient perspective. The Food and Drug Administration has called for the development of coprimary endpoints in research trials to include an objective measure of inflammation in conjunction with patient-reported outcomes (PROs). The objective is to support labeling claims and improve safety and effectiveness in the drug approval process.1,2 There is also growing recognition that high-value care includes management of biologic and psychosocial factors to enable patients with chronic diseases to regain their health. Clinicians might follow suit by incorporating valid, reliable PRO measures to usual IBD care in order better to achieve patient-centered care, inform decision making, and improve the care provided.

What are patient-reported outcomes?

The FDA defines a PRO as “any report of the status of a patient’s health condition that comes directly from the patient, without interpretation of the patient’s response by a clinician or anyone else.” Two PROs are used to measure various aspects of health including physical, emotional, or social domains. PROs have emerged as tools that may foster a better understanding of the patient’s condition, which may go beyond disease activity or symptoms. In effect, incorporating PROs into clinical practice enables a model of “coproduction” of health care, and may contribute to a more reciprocal patient-provider interaction where the needs of the patient may be more fully understood and incorporated into decision-making that may lead to improved patient satisfaction and outcomes.3,4

There are hundreds of available PROs in gastroenterology,5 ranging from simple (characterizing pain with a basic numeric rating scale) to complex multidomain, multi-item instruments. PROs may cover symptom assessment, health-related quality of life, and adherence to and satisfaction with treatment, and may be generic or disease specific. Numerous PROs have been developed for patients with IBD. Commonly used PROs in IBD include severity scales for pain, defecatory urgency, and bloody stool, and several disease-specific and generic instruments assessing different health-related quality-of-life domains have been used in research studies for patients with IBD.

The current approach to patient-centered care for IBD is limited

IBD is a difficult disease to manage – in part because there is no known biomarker that accurately reflects the full spectrum of disease activity. Numerous indices have been developed to better quantify disease activity and measure response to treatment. Among the most frequently used indices in clinical trials are the Crohn’s Disease Activity Index (CDAI) and (for ulcerative colitis [UC]) the Mayo Clinic Score. These endpoints incorporate signs and symptoms, laboratory findings (in the CDAI), and endoscopic assessments. The CDAI is a suboptimal instrument because of a lack of correlation with endoscopic inflammation and potential confounding with concomitant gastrointestinal illnesses, such as irritable bowel syndrome.6 The Mayo Clinic Score is difficult to interpret because of some subjective elements (what is considered a normal number of stools per day?); vagueness (mostly bloody stools more than half the time?); and need for a physician assessment, which often does not correspond with the patient’s perception of their disease.7 From a research perspective, this disconnect can compromise the quality of trial data. Clinically, it can negatively impact patients’ satisfaction and impair the patient-provider relationship.8

To that end, regulatory agencies, scientific bodies, and health care payors are shifting toward a more “patient-centered” approach with an emphasis on PROs. However, although the FDA is incorporating the patient perspective in its trials, measuring meaningful outcomes in day-to-day clinical care is challenging. In the absence of active inflammation, more than 30% of patients with IBD still suffer from gastrointestinal symptoms.9 Furthermore, physicians frequently underestimate the effect of depression, anxiety, fatigue, and sleep on patient health. Likewise, some patients with active small-bowel Crohn’s disease (CD) may experience few gastrointestinal symptoms but have profound fatigue, weight loss, and impaired quality of life. A focused assessment for disease activity may fail to identify aspects of health most relevant or important to individual patient well-being. There is a need for effective, efficient, and standardized strategies to better understand the concerns of the individual seeking help.

Although there are several PROs that measure disease activity primarily for clinical research trials,10 their prevalence in gastroenterology practices has not been assessed. Most likely, few clinical practices currently integrate standardized PROs in routine patient care. This may be because of several reasons, including lack of awareness of newly developed PROs, administrative burden including time and resources to collect PROs, potentially complex interpretation of results, and perhaps a reluctance among physicians to alter traditional patient interview methods of obtaining information about the health status of their patients. For effective use in clinical care, PROs require simple and relevant interpretation to add value to the clinician’s practice, and must minimally impact clinical flow and resources. The use of Internet-enabled tablets has been shown to be a feasible, efficient, and effective means of PRO assessment in gastroenterology practices, with good levels of patient satisfaction.11

Reaping potential benefits of patient-reported outcomes

The National Institutes of Health Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) is an initiative developed to investigate and promote implementation of PRO measures among patients with chronic diseases. The collection of PROMIS measures has been shown to be feasible at a tertiary care IBD center, enabling a biopsychosocial model of care.12 Likewise, implementation of PROs in other clinical areas including oncology, orthopedics, and rheumatology has been robust.

In an innovative orthopedic study, PROMIS measures collected and linked to the electronic medical record predicted the likelihood of a clinically meaningful benefit from foot and ankle surgery.13 This facilitated tailored patient-specific preoperative discussions about the expected benefit of surgery. In a study at a rheumatology clinic patients with rheumatoid arthritis were asked to identify their highest priority treatment targets using PROMIS domains (fatigue, pain, depression, social function). The highest priority domain was tracked over time as a patient-centered marker of health, essentially personalizing measures of success for the individual patient.14

PROs have the unique potential to affect multiple levels of health care. At the patient level, PRO data can identify specific concerns, manage expectations of recovery, and tailor treatment decisions to personal preference. At the population level, PRO data can be used to standardize aspects of care to understand comparative health and disease among all patients in a practice or relative to outside practices, identify outliers, and drive improvement.

Optimizing PROs for use in clinical trials: CD–PROs and UC–PROs

Developing standardized, validated instruments according to FDA guidance is a complex process. The lack of an FDA-approved PRO has resulted in substantial variability in the definitions of clinical response or remission in clinical trials to date.15 As a result, IBD-specific PROs (CD-PRO and UC-PRO) are being developed under FDA guidance for use in clinical trials.16 With achievement of prequalification for open use, UC-PRO and CD-PRO will cover five IBD-specific outcomes domains or modules: 1) bowel signs and symptoms, 2) systemic symptoms, 3) emotional impact, 4) coping behaviors, and 5) IBD impact on daily life. The bowel signs and symptoms module may also incorporate a functional impact assessment. Each module includes numerous pertinent items (e.g., “I feel worried,” “I feel scared,” “I feel alone” in the emotional impact module) and are currently being tailored and scored for practicality and relevance. It is hoped that UC-PRO and CD-PRO in final form will be relevant and applicable for clinical trials and gastroenterology practices alike.

Because the development of the UC-PRO and the CD-PRO is still underway, interim PROs are being used in ongoing clinical trials. These interim measures were extracted from existing components of the CDAI, Mayo Clinic Score, and UC Disease Activity Index. The CD PRO-2 consists of two items: abdominal pain and stool frequency. The UC PRO-2 is composed of rectal bleeding and stool frequency. The PRO-3 adds an item regarding general well-being. The sensitivity of these PROs was tested in studies for CD and UC. Both PROs performed similarly to their respective parent instrument. Important limitations include the lack of validation, and the fact that these interim measures were derived from parent measures with acknowledged limitations as previously discussed. Current clinical trials are coupling these interim measures with endoscopic data as coprimary endpoints.

PROs in routine clinical practice: Are we ready for prime time?

Few instruments developed to date have been widely implemented into routine IBD clinical practice. Table 1 highlights commonly available or recently developed PROs for IBD care. As clinicians strive to more effectively integrate PROs into clinical practice, we propose a three-step process to getting started: 1) select and administer a PRO instrument, 2) identify areas of impairment and create a targeted treatment strategy to focus on those areas, and 3) repeat the same PRO at follow-up to assess for improvement. The instrument can be administered before the visit or in the clinic waiting room. Focus a portion of the patient’s visit on discussing the results and identifying one or more domains to target for improvement. For example, the patient may indicate diarrhea as his/her most important area to target, triggering a symptom-specific investigation and therapeutic approach. The PRO may also highlight social or emotional impairment that may require an ancillary referral. The benefits of this PRO-driven approach to IBD care are twofold. First, the patient’s primary concerns are positioned at the forefront of the clinical visit. Second, aligning the clinician’s focus with the patient input may actually help to streamline each visit and improve overall visit efficiency and patient satisfaction.

Conclusions

As therapies for IBD improve, so should standards of patient-centered care. Clinicians must actively seek and then listen to the concerns of patients and be able to address the multiple facets of living with a chronic disease. PROs empower patients, helping them identify important topics for discussion at the clinical visit. This affords clinicians a better understanding of primary patient concerns before the visit, and potentially improves the quality and value of care. At first, the process of incorporating PROs into a busy clinical practice may be challenging, but targeted treatment plans have the potential to foster a better patient – and physician – experience.

Content from this column was originally published in the “Practice Management: The Road Ahead” section of Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology (2018;16[5]:603-7).

References

1. Guidance for industry: patient-reported outcome measures: use in medical product development to support labeling claims: draft guidance. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2006;4:79.

2. Burke, L.B., Kennedy, D.L., Miskala, P.H., et al. The use of patient-reported outcome measures in the evaluation of medical products for regulatory approval. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2008;84:281-3.

3. Batalden, M., Baltalden, P., Margolis, P., et al. Coproduction of healthcare service. BMJ Qual Saf. 2016;25:509-17.

4. Johnson, L.C. Melmed, G.Y., Nelson, E.C., et al. Fostering collaboration through creation of an IBD learning health system. Am J Gastroenterol. 2017;112:406-8.

5. Khanna, P., Agarwal, N., Khanna, D., et al. Development of an online library of patient reported outcome measures in gastroenterology: the GI-PRO database. Am J Gastroenterol. 2014;109:234-48.

6. Bruining, D.H. Sandborn, W.J. Do not assume symptoms indicate failure of anti-tumor necrosis factor therapy in January 2015 Emerging Treatment Goals in IBD Trials and Practice 45 REVIEWS AND PERSPECTIVES Crohn’s disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;9:395-9.

7. Surti, B., Spiegel, B., Ippoliti, A., et al. Assessing health status in inflammatory bowel disease using a novel single-item numeric rating scale. Dig Dis Sci. 2013;58:1313-21.

8. Marshall, S., Haywood, K. Fitzpatrick R. Impact of patient-reported outcome measures on routine practice: a structured review. J Eval Clin Pract. 2006;12:559-68.

9. Simren, M., Axelsson, J., Gillberg, R., et al. Quality of life in inflammatory bowel disease in remission: the impact of IBD-like symptoms and associated psychological factors. Am J Gastroenterol. 2002;97:389-96.

10. De Jong, M.J., Huibregtse, R., Masclee, A.A.M., et al. Patient-reported outcome measures for use in clinical trials and clinical practice in inflammatory bowel diseases: a systematic review. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;16:648-63.

11. Atreja, A., Rizk, M. Capturing patient reported outcomes and quality of life in routine clinical practice: ready to prime time? Minerva Gastroenterol Dietol. 2012;58:19-24.

12. Ishak, W.W., Pan, D., Steiner, A.J., et al. Patient reported outcomes of quality of life, functioning, and GI/psychiatric symptom severity in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2017;23:798-803.

13. Ho, B., Houck, J.R., Flemister, A.S., et al. Preoperative PROMIS scores predict postoperative success in foot and ankle patients. Foot Ankle Int. 2016;37:911-8. 14. Bacalao, E., Greene, G.J., Beaumont, J.L., et al. Standardizing and personalizing the treat to target (T2T) approach for rheumatoid arthritis using the Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS): baseline findings on patient-centered treatment priorities. Clin Rheumatol. 2017;36:1729-36.

15. Ma, C., Panaccione, R., Fedorak, R.N., et al. Heterogeneity in definitions of endpoints for clinical trials of ulcerative colitis: a systematic review for development of a core outcome set. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;16:637-47.

16. Higgins P. Patient reported outcomes in IBD 2017. Available at: ibdctworkshop.files.wordpress.com/2017/01/patient-reported-outcomes-in-ibd___peter-higgins.pdf. Accessed Aug. 27, 2017.

17. Guyatt, G., Mitchell, A. Irvine, E.J., et al. A new measure of health status for clinical trials in inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterology. 1989;96:804-10.

18. Love, J.R., Irvine, E.J., Fedorak, R.N. Quality of life in inflammatory bowel disease. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1992;14:15-9.

19. Irvine, E.J., Zhou, Q., Thompson, A.K. The short inflammatory bowel disease questionnaire: a quality of life instrument for community physicians managing inflammatory bowel disease. CCRPT investigators. Canadian Crohn’s Relapse Prevention Trial. Am J Gastroenterol. 1996;91:1571-8.

20. Fazio, V.W., O’Riordain, M.G., Lavery, I.C., et al. Long-term functional outcome and quality of life after stapled restorative proctocolectomy. Ann Surg. 1999;230:575-84.

21. Gower-Rousseau, C., Sarter, H., Savoye, G., et al. Validation of the inflammatory bowel disease disability index in a population-based cohort. Gut. 2017;66:588-96.

22. Gosh, S., Louis, E., Beaugerie, L., et al. Development of the IBD-Disk: a visual self-administered tool assessing disability in inflammatory bowel diseases. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2017;23:333-40.

23. Khanna, R., Zou, G., D’Haens, G., et al. A retrospective analysis: the development of patient reported outcome measures for the assessment of Crohn’s disease activity. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2015;41:77-86.

24. Walmsley, R.S., Ayres, R.C.S., Pounder, P.R., et al. A simple clinical colitis activity index. Gut. 1998;43:29-32.

25. Bodger, K., Ormerod, C., Shackcloth, D., et al. Development and validation of a rapid, general measure of disease control from the patient perspective: the IBD-Control questionnaire. Gut. 2014;63:1092-102.

26. Cleeland, C.S., Ryan, K.M. Pain assessment: global use of the Brief Pain Inventory. Ann Acad Med Singapore. 1994;23:129-38.

27. Kroenke, K., Spitzer, R.L., Williams, J.B.W. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16:606-13.

28. Zigmond, A.S., Snaith, R.P. The Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1983;67:361-70.

29. Spitzer, R.L., Korneke, K., Williams, J.B., et al. A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: the GAD-7. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166:1092-7.

30. Reilly, M.C., Zbrozek, A.S. Dukes, E.M. The validity and reproducibility of a work productivity and activity impairment instrument. Pharmachoeconomics. 1993;4:353-65.

31. Smets, E.M., Garssen, B. Bonke, B., et al. The Multidimensional Fatigue Inventory psychometric qualities of an instrument to assess fatigue. J Psychosom Res. 1995;39:315-25.

32. Czuber-Dochan, W., Norton, C., Bassettt, P., et al. Development and psychometric testing of inflammatory bowel disease fatigue (IBD-F) patient self-assessment scale. J Crohns Colitis. 2014;8:1398-406.

33. Drossman, D.A., Leserman, J., Li, Z.M., et al. The rating form of IBD patient concerns: a new measure of health status. Psychosom Med. 1991;53:701-12. 34. Cohen, S., Kamarck, T., Mermelstein, R. A global measure of perceived stress. J Health Soc Behav. 1983;24:385-96.

Dr. Cohen is in the division of digestive and liver diseases; Dr. Melmed is director, clinical inflammatory bowel disease, director, clinical research in the division of gastroenterology, and director, advanced inflammatory bowel disease fellowship program, Cedars-Sinai Medical Center, Los Angeles. Dr. Melmed is a consultant for AbbVie, Boehringer Ingelheim, Celgene, Genentech, Janssen, Pfizer, Samsung Bioepis, Takeda, and UCB; and received support for research from Prometheus Labs. The remaining author discloses no conflicts.

Patients seek medical care when they perceive a deterioration in their health. Gastroenterologists and health care providers are trained to seek out clinical, laboratory, radiologic, and endoscopic evidence of pathology. Conventional endpoints in inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) clinical trials and clinical care may fail to capture the full health status and disease experience from the patient perspective. The Food and Drug Administration has called for the development of coprimary endpoints in research trials to include an objective measure of inflammation in conjunction with patient-reported outcomes (PROs). The objective is to support labeling claims and improve safety and effectiveness in the drug approval process.1,2 There is also growing recognition that high-value care includes management of biologic and psychosocial factors to enable patients with chronic diseases to regain their health. Clinicians might follow suit by incorporating valid, reliable PRO measures to usual IBD care in order better to achieve patient-centered care, inform decision making, and improve the care provided.

What are patient-reported outcomes?

The FDA defines a PRO as “any report of the status of a patient’s health condition that comes directly from the patient, without interpretation of the patient’s response by a clinician or anyone else.” Two PROs are used to measure various aspects of health including physical, emotional, or social domains. PROs have emerged as tools that may foster a better understanding of the patient’s condition, which may go beyond disease activity or symptoms. In effect, incorporating PROs into clinical practice enables a model of “coproduction” of health care, and may contribute to a more reciprocal patient-provider interaction where the needs of the patient may be more fully understood and incorporated into decision-making that may lead to improved patient satisfaction and outcomes.3,4

There are hundreds of available PROs in gastroenterology,5 ranging from simple (characterizing pain with a basic numeric rating scale) to complex multidomain, multi-item instruments. PROs may cover symptom assessment, health-related quality of life, and adherence to and satisfaction with treatment, and may be generic or disease specific. Numerous PROs have been developed for patients with IBD. Commonly used PROs in IBD include severity scales for pain, defecatory urgency, and bloody stool, and several disease-specific and generic instruments assessing different health-related quality-of-life domains have been used in research studies for patients with IBD.

The current approach to patient-centered care for IBD is limited

IBD is a difficult disease to manage – in part because there is no known biomarker that accurately reflects the full spectrum of disease activity. Numerous indices have been developed to better quantify disease activity and measure response to treatment. Among the most frequently used indices in clinical trials are the Crohn’s Disease Activity Index (CDAI) and (for ulcerative colitis [UC]) the Mayo Clinic Score. These endpoints incorporate signs and symptoms, laboratory findings (in the CDAI), and endoscopic assessments. The CDAI is a suboptimal instrument because of a lack of correlation with endoscopic inflammation and potential confounding with concomitant gastrointestinal illnesses, such as irritable bowel syndrome.6 The Mayo Clinic Score is difficult to interpret because of some subjective elements (what is considered a normal number of stools per day?); vagueness (mostly bloody stools more than half the time?); and need for a physician assessment, which often does not correspond with the patient’s perception of their disease.7 From a research perspective, this disconnect can compromise the quality of trial data. Clinically, it can negatively impact patients’ satisfaction and impair the patient-provider relationship.8

To that end, regulatory agencies, scientific bodies, and health care payors are shifting toward a more “patient-centered” approach with an emphasis on PROs. However, although the FDA is incorporating the patient perspective in its trials, measuring meaningful outcomes in day-to-day clinical care is challenging. In the absence of active inflammation, more than 30% of patients with IBD still suffer from gastrointestinal symptoms.9 Furthermore, physicians frequently underestimate the effect of depression, anxiety, fatigue, and sleep on patient health. Likewise, some patients with active small-bowel Crohn’s disease (CD) may experience few gastrointestinal symptoms but have profound fatigue, weight loss, and impaired quality of life. A focused assessment for disease activity may fail to identify aspects of health most relevant or important to individual patient well-being. There is a need for effective, efficient, and standardized strategies to better understand the concerns of the individual seeking help.

Although there are several PROs that measure disease activity primarily for clinical research trials,10 their prevalence in gastroenterology practices has not been assessed. Most likely, few clinical practices currently integrate standardized PROs in routine patient care. This may be because of several reasons, including lack of awareness of newly developed PROs, administrative burden including time and resources to collect PROs, potentially complex interpretation of results, and perhaps a reluctance among physicians to alter traditional patient interview methods of obtaining information about the health status of their patients. For effective use in clinical care, PROs require simple and relevant interpretation to add value to the clinician’s practice, and must minimally impact clinical flow and resources. The use of Internet-enabled tablets has been shown to be a feasible, efficient, and effective means of PRO assessment in gastroenterology practices, with good levels of patient satisfaction.11

Reaping potential benefits of patient-reported outcomes

The National Institutes of Health Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) is an initiative developed to investigate and promote implementation of PRO measures among patients with chronic diseases. The collection of PROMIS measures has been shown to be feasible at a tertiary care IBD center, enabling a biopsychosocial model of care.12 Likewise, implementation of PROs in other clinical areas including oncology, orthopedics, and rheumatology has been robust.

In an innovative orthopedic study, PROMIS measures collected and linked to the electronic medical record predicted the likelihood of a clinically meaningful benefit from foot and ankle surgery.13 This facilitated tailored patient-specific preoperative discussions about the expected benefit of surgery. In a study at a rheumatology clinic patients with rheumatoid arthritis were asked to identify their highest priority treatment targets using PROMIS domains (fatigue, pain, depression, social function). The highest priority domain was tracked over time as a patient-centered marker of health, essentially personalizing measures of success for the individual patient.14

PROs have the unique potential to affect multiple levels of health care. At the patient level, PRO data can identify specific concerns, manage expectations of recovery, and tailor treatment decisions to personal preference. At the population level, PRO data can be used to standardize aspects of care to understand comparative health and disease among all patients in a practice or relative to outside practices, identify outliers, and drive improvement.

Optimizing PROs for use in clinical trials: CD–PROs and UC–PROs