User login

Manic after taking a vacation

CASE From soft-spoken to manic

Mr. K, age 36, an Asian male with no psychiatric history, arrives at the outpatient psychiatry clinic accompanied by his wife, after being referred from the emergency room the night before. He reports racing thoughts, euphoric mood, increased speech, hypergraphia, elevated self-esteem, decreased need for sleep, distractibility, and increased goal-directed activity. Notably, Mr. K states that he likes how he is feeling.

Mr. K’s wife says that his condition is a clear change from his baseline demeanor: soft-spoken and mild-mannered.

Mr. K reports that his symptoms started approximately 10 days earlier, after he returned from a cruise with his wife. During the cruise, he used a scopolamine patch to prevent motion sickness. Mr. K and his wife say that they believe that the scopolamine patch caused his symptoms.

Can scopolamine cause mania?

a) No

b) Yes; this is well-documented in the literature

c) It is theoretically possible because of scopolamine’s antidepressant and central anticholinergic effects

TREATMENT Lithium, close follow up

Mr. K has no history of psychiatric illness or substance use and no recent use of psychoactive substances—other than scopolamine—that could trigger a manic episode. His family history is significant for a younger brother who had a single manic episode at age 12 and a suicide attempt as a young adult.

Mr. K works full-time on rotating shifts—including some overnight shifts—as a manufacturing supervisor at a biotechnology company. He has been unable to work since returning from the cruise because of his psychiatric symptoms.

Mr. K is started on sustained-release (SR) lithium, 900 mg/d. In addition, the psychiatrist advises Mr. K to continue taking clonazepam, 0.5 to 1 mg as needed, which the emergency medicine physician prescribed, for insomnia. Mr. K is referred to a psychiatric intensive outpatient program (IOP), 3 days a week for 2 weeks, and is advised to stay home from work until symptoms stabilize.

Mr. K follows up closely with the psychiatrist in the clinic, every 1 to 2 weeks for the first month, as well as by several telephone and e-mail contacts. Lithium SR is titrated to 1,200 mg/d, to a therapeutic serum level of 1.1 mEq/L. Clonazepam is switched to quetiapine, 25 to 50 mg as needed, to address ongoing insomnia and to reduce the risk of dependency on clonazepam.

Mr. K’s mania gradually abates. He finishes the IOP and returns to work 3 weeks after his initial presentation. At an office visit, Mr. K’s wife gives the psychiatrist 2 scientific articles documenting the antidepressant effect of scopolamine.1,2 Mr. K and his wife both continue to believe that Mr. K’s manic episode was triggered by the scopolamine patch he used while on the cruise. They think this is important because Mr. K believes he would not have developed mania otherwise, and he does not want to take a mood stabilizer for the rest of his life.

The author’s observations

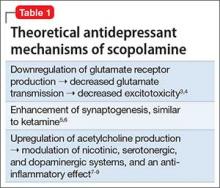

There are several proposed mechanisms for scopolamine’s antidepressant effect (Table 1).3-9 Scopolamine blocks central muscarinic cholinergic receptors, which reduces production of glutamate receptors and leads to reduced glutamate transmission and neurotoxicity.3,4 Scopolamine—similar to ketamine—could enhance synaptogenesis and synaptic signaling.5,6 Also, by blocking muscarinic autoreceptors, scopolamine results in an acute upregulation of acetylcholine release, which, in turn, influences the nicotinic, dopamine, serotonin, and neuropeptide Y systems. This action could contribute to anti-inflammatory effects, all of which can benefit mood.7-9 These antidepressant mechanisms also could explain why, theoretically, scopolamine could precipitate mania in a person predisposed to mental illness.

Proposed by Janowsky et al10 in 1972, the cholinergic−adrenergic balance hypothesis of affective disorders suggests that depression represents an excess of central cholinergic tone over adrenergic tone, and that mania represents the opposite imbalance. Several lines of evidence in the literature support this theory. For example, depressed patients have been found to have hypersensitive central cholinergic receptors.11,12 Also, central cholinesterase inhibition has been shown to affect pituitary hormone and epinephrine levels via central muscarinic receptors.13 In addition, scopolamine has been shown to attenuate these effects via the central anti-muscarinic mechanism.14

Rapid antidepressant therapy. Scopolamine is being studied as a rapid antidepressant treatment, although it usually is administered via IV infusion, rather than patch form, in trials.15-17 IV ketamine is another therapy being investigated for rapid treatment of depression, which might have downstream mechanisms of action related to scopolamine.5,18 Electroconvulsive therapy is a well-known for its quick antidepressant effect, which could involve synaptogenesis or effects on the neuroendocrine system.19 Sleep deprivation also can produce a rapid antidepressant effect20 (Table 21,2,5,6,15,16,18-20).

OUTCOME Prone to motion sickness

Approximately 3.5 months after his initial presentation, Mr. K continues to do well with treatment. He is euthymic and functioning well at work. He and his wife are preparing for the birth of their first child.

Mr. K is prone to motion sickness, and asks if he can take over-the-counter dimenhydrinate tablets for long car rides. He reports that dimenhydrinate has worked well for him in the past without triggering manic episodes, and he did not anticipate needing to take it very often.

What would you tell Mr. K about dimenhydrinate for motion sickness during car rides?

a) Mr. K should not take dimenhydrinate to prevent motion sickness because he experienced a manic episode triggered by a scopolamine patch

b) Mr. K can use dimenhydrinate as much as he wants to prevent motion sickness because it poses no risk of mania

c) Mr. K can use dimenhydrinate with caution and sparingly on a trial basis, as long as he is taking his mood stabilizer

FOLLOW UP Cautious use

The psychiatrist advised Mr. K to take dimenhydrinate cautiously when needed for long car rides. The psychiatrist feels this is safe because Mr. K is taking a mood stabilizer (lithium). Also, although dimenhydrinate has anticholinergic properties, occasional use is thought to pose less risk of triggering mania than the constant anticholinergic exposure over several days with a scopolamine patch. (The scopolamine patch contains 1.5 mg of the drug delivered over 3 days [ie, 0.5 mg/d]. In trials of IV scopolamine for depression, the dosage was 0.4 mcg/kg/d administered over 3 consecutive days.15-17 For an adult weighing 70 kg, this would be equivalent to 0.24 mg/d. Therefore, using a scopolamine patch over 3 days would appear to deliver a robust antidepressant-level dosage, even taking into account possible lower bioavailability with transdermal administration compared with IV infusion.)

The psychiatrist concludes that sporadic use of dimenhydrinate tablets for motion sickness during occasional long car rides poses less of a risk for Mr. K of triggering mania than repeat use of a scopolamine patch.

The author’s observations

Mr. K’s case is notable for several reasons:

- Novelty. This might be the first report of scopolamine-induced mania in the literature. In clinical trials by Furey and Drevets,15 Drevets and Furey,16 and Ellis et al,17 no study participants who received scopolamine infusion developed mania or hypomania. Although it is possible that Mr. K’s manic episode could have occurred spontaneously and was coincidental to his scopolamine use, there are valid reasons why scopolamine could trigger mania in a vulnerable person.

- Biochemical insight. The case underscores the role of the muscarinic cholinergic system in regulating mood.10

- Rational medical care. Sensible clinical decision-making was needed when Mr. K asked about using dimenhydrinate for motion sickness during car rides. Although there might not be definitively correct answers for questions that arose during Mr. K’s care (in the absence of research literature), theoretical understanding of the antidepressant effects of anticholinergic medications helped inform the psychiatrist’s responses to Mr. K and his wife.

1. Drevets WC, Zarate CA Jr, Furey ML. Antidepressant effects of the muscarinic cholinergic receptor antagonist scopolamine: a review. Biol Psychiatry. 2013;73(12):1156-1163.

2. Jaffe RJ, Novakovic V, Peselow ED. Scopolamine as an antidepressant: a systematic review. Clin Neuropharmacol. 2013;36(1):24-26.

3. Rami A, Ausmeir F, Winckler J, et al. Differential effects of scopolamine on neuronal survival in ischemia and glutamate neurotoxicity: relationships to the excessive vulnerability of the dorsoseptal hippocampus. J Chem Neuroanat. 1997;13(3):201-208.

4. Benveniste M, Wilhelm J, Dingledine RJ, et al. Subunit-dependent modulation of kainate receptors by muscarinic acetylcholine receptors. Brain Res. 2010;1352:61-69.

5. Duman RS, Li N, Liu RJ, et al. Signaling pathways underlying the rapid antidepressant actions of ketamine. Neuropharmacology. 2012;62(1):35-41.

6. Voleti B, Navarria A, Liu R, et al. Scopolamine rapidly increases mammalian target of rapamycin complex 1 signaling, synaptogenesis, and antidepressant behavioral responses. Biol Psychiatry. 2013;74(10):742-749.

7. Overstreet DH, Friedman E, Mathé AA, et al. The Flinders Sensitive Line rat: a selectively bred putative animal model of depression. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2005;29(4-5):739-759.

8. Tizabi Y, Getachew B, Rezvani AH, et al. Antidepressant-like effects of nicotine and reduced nicotinic receptor binding in the Fawn-Hooded rat, an animal model of co-morbid depression and alcoholism. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2009;33(3):398-402.

9. Wang DW, Zhou RB, Yao YM. Role of cholinergic anti-inflammatory pathway in regulating host response and its interventional strategy for inflammatory diseases. Chin J Traumatol. 2009;12(6):355-364.

10. Janowsky DS, el-Yousef MK, Davis JM, et al. A cholinergic-adrenergic hypothesis of mania and depression. Lancet. 1972;2(7778):632-635.

11. Risch SC, Kalin NH, Janowsky DS. Cholinergic challenges in affective illness: behavioral and neuroendocrine correlates. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 1981;1(4):186-192.

12. Risch SC, Janowsky DS, Gillin JC. Muscarinic supersensitivity of anterior pituitary ACTH and β-endorphin release in major depressive illness. Peptides. 1983;4(5):789-792.

13. Risch SC, Janowsky DS, Mott MA, et al. Central and peripheral cholinesterase inhibition: effects on anterior pituitary and sympathomimetic function. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 1986;11(2):221-230.

14. Janowsky DS, Risch SC, Kennedy B, et al. Central muscarinic effects of physostigmine on mood, cardiovascular function, pituitary and adrenal neuroendocrine release. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 1986;89(2):150-154.

15. Furey ML, Drevets WC. Antidepressant efficacy of the antimuscarinic drug scopolamine: a randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2006;63(10):1121-1129.

16. Drevets WC, Furey ML. Replication of scopolamine’s antidepressant efficacy in major depressive disorder: a randomized, placebo-controlled clinical trial. Biol Psychiatry. 2010;67(5):432-438.

17. Ellis JS, Zarate CA Jr, Luckenbaugh DA, et al. Antidepressant treatment history as a predictor of response to scopolamine: clinical implications. J Affect Disord. 2014;162:39-42.

18. Newport DJ, Carpenter LL, McDonald WM, et al. Ketamine and other NMDA antagonists: early clinical trials and possible mechanisms in depression. Am J Psychiatry. 2015;172(10):950-966.

19. Bolwig TG. How does electroconvulsive therapy work? Theories on its mechanism. Can J Psychiatry. 2011;56(1):13-18.

20. Wu JC, Kelsoe JR, Schachat C, et al. Rapid and sustained antidepressant response with sleep deprivation and chronotherapy in bipolar disorder. Biol Psychiatry. 2009;66(3):298-301.

CASE From soft-spoken to manic

Mr. K, age 36, an Asian male with no psychiatric history, arrives at the outpatient psychiatry clinic accompanied by his wife, after being referred from the emergency room the night before. He reports racing thoughts, euphoric mood, increased speech, hypergraphia, elevated self-esteem, decreased need for sleep, distractibility, and increased goal-directed activity. Notably, Mr. K states that he likes how he is feeling.

Mr. K’s wife says that his condition is a clear change from his baseline demeanor: soft-spoken and mild-mannered.

Mr. K reports that his symptoms started approximately 10 days earlier, after he returned from a cruise with his wife. During the cruise, he used a scopolamine patch to prevent motion sickness. Mr. K and his wife say that they believe that the scopolamine patch caused his symptoms.

Can scopolamine cause mania?

a) No

b) Yes; this is well-documented in the literature

c) It is theoretically possible because of scopolamine’s antidepressant and central anticholinergic effects

TREATMENT Lithium, close follow up

Mr. K has no history of psychiatric illness or substance use and no recent use of psychoactive substances—other than scopolamine—that could trigger a manic episode. His family history is significant for a younger brother who had a single manic episode at age 12 and a suicide attempt as a young adult.

Mr. K works full-time on rotating shifts—including some overnight shifts—as a manufacturing supervisor at a biotechnology company. He has been unable to work since returning from the cruise because of his psychiatric symptoms.

Mr. K is started on sustained-release (SR) lithium, 900 mg/d. In addition, the psychiatrist advises Mr. K to continue taking clonazepam, 0.5 to 1 mg as needed, which the emergency medicine physician prescribed, for insomnia. Mr. K is referred to a psychiatric intensive outpatient program (IOP), 3 days a week for 2 weeks, and is advised to stay home from work until symptoms stabilize.

Mr. K follows up closely with the psychiatrist in the clinic, every 1 to 2 weeks for the first month, as well as by several telephone and e-mail contacts. Lithium SR is titrated to 1,200 mg/d, to a therapeutic serum level of 1.1 mEq/L. Clonazepam is switched to quetiapine, 25 to 50 mg as needed, to address ongoing insomnia and to reduce the risk of dependency on clonazepam.

Mr. K’s mania gradually abates. He finishes the IOP and returns to work 3 weeks after his initial presentation. At an office visit, Mr. K’s wife gives the psychiatrist 2 scientific articles documenting the antidepressant effect of scopolamine.1,2 Mr. K and his wife both continue to believe that Mr. K’s manic episode was triggered by the scopolamine patch he used while on the cruise. They think this is important because Mr. K believes he would not have developed mania otherwise, and he does not want to take a mood stabilizer for the rest of his life.

The author’s observations

There are several proposed mechanisms for scopolamine’s antidepressant effect (Table 1).3-9 Scopolamine blocks central muscarinic cholinergic receptors, which reduces production of glutamate receptors and leads to reduced glutamate transmission and neurotoxicity.3,4 Scopolamine—similar to ketamine—could enhance synaptogenesis and synaptic signaling.5,6 Also, by blocking muscarinic autoreceptors, scopolamine results in an acute upregulation of acetylcholine release, which, in turn, influences the nicotinic, dopamine, serotonin, and neuropeptide Y systems. This action could contribute to anti-inflammatory effects, all of which can benefit mood.7-9 These antidepressant mechanisms also could explain why, theoretically, scopolamine could precipitate mania in a person predisposed to mental illness.

Proposed by Janowsky et al10 in 1972, the cholinergic−adrenergic balance hypothesis of affective disorders suggests that depression represents an excess of central cholinergic tone over adrenergic tone, and that mania represents the opposite imbalance. Several lines of evidence in the literature support this theory. For example, depressed patients have been found to have hypersensitive central cholinergic receptors.11,12 Also, central cholinesterase inhibition has been shown to affect pituitary hormone and epinephrine levels via central muscarinic receptors.13 In addition, scopolamine has been shown to attenuate these effects via the central anti-muscarinic mechanism.14

Rapid antidepressant therapy. Scopolamine is being studied as a rapid antidepressant treatment, although it usually is administered via IV infusion, rather than patch form, in trials.15-17 IV ketamine is another therapy being investigated for rapid treatment of depression, which might have downstream mechanisms of action related to scopolamine.5,18 Electroconvulsive therapy is a well-known for its quick antidepressant effect, which could involve synaptogenesis or effects on the neuroendocrine system.19 Sleep deprivation also can produce a rapid antidepressant effect20 (Table 21,2,5,6,15,16,18-20).

OUTCOME Prone to motion sickness

Approximately 3.5 months after his initial presentation, Mr. K continues to do well with treatment. He is euthymic and functioning well at work. He and his wife are preparing for the birth of their first child.

Mr. K is prone to motion sickness, and asks if he can take over-the-counter dimenhydrinate tablets for long car rides. He reports that dimenhydrinate has worked well for him in the past without triggering manic episodes, and he did not anticipate needing to take it very often.

What would you tell Mr. K about dimenhydrinate for motion sickness during car rides?

a) Mr. K should not take dimenhydrinate to prevent motion sickness because he experienced a manic episode triggered by a scopolamine patch

b) Mr. K can use dimenhydrinate as much as he wants to prevent motion sickness because it poses no risk of mania

c) Mr. K can use dimenhydrinate with caution and sparingly on a trial basis, as long as he is taking his mood stabilizer

FOLLOW UP Cautious use

The psychiatrist advised Mr. K to take dimenhydrinate cautiously when needed for long car rides. The psychiatrist feels this is safe because Mr. K is taking a mood stabilizer (lithium). Also, although dimenhydrinate has anticholinergic properties, occasional use is thought to pose less risk of triggering mania than the constant anticholinergic exposure over several days with a scopolamine patch. (The scopolamine patch contains 1.5 mg of the drug delivered over 3 days [ie, 0.5 mg/d]. In trials of IV scopolamine for depression, the dosage was 0.4 mcg/kg/d administered over 3 consecutive days.15-17 For an adult weighing 70 kg, this would be equivalent to 0.24 mg/d. Therefore, using a scopolamine patch over 3 days would appear to deliver a robust antidepressant-level dosage, even taking into account possible lower bioavailability with transdermal administration compared with IV infusion.)

The psychiatrist concludes that sporadic use of dimenhydrinate tablets for motion sickness during occasional long car rides poses less of a risk for Mr. K of triggering mania than repeat use of a scopolamine patch.

The author’s observations

Mr. K’s case is notable for several reasons:

- Novelty. This might be the first report of scopolamine-induced mania in the literature. In clinical trials by Furey and Drevets,15 Drevets and Furey,16 and Ellis et al,17 no study participants who received scopolamine infusion developed mania or hypomania. Although it is possible that Mr. K’s manic episode could have occurred spontaneously and was coincidental to his scopolamine use, there are valid reasons why scopolamine could trigger mania in a vulnerable person.

- Biochemical insight. The case underscores the role of the muscarinic cholinergic system in regulating mood.10

- Rational medical care. Sensible clinical decision-making was needed when Mr. K asked about using dimenhydrinate for motion sickness during car rides. Although there might not be definitively correct answers for questions that arose during Mr. K’s care (in the absence of research literature), theoretical understanding of the antidepressant effects of anticholinergic medications helped inform the psychiatrist’s responses to Mr. K and his wife.

CASE From soft-spoken to manic

Mr. K, age 36, an Asian male with no psychiatric history, arrives at the outpatient psychiatry clinic accompanied by his wife, after being referred from the emergency room the night before. He reports racing thoughts, euphoric mood, increased speech, hypergraphia, elevated self-esteem, decreased need for sleep, distractibility, and increased goal-directed activity. Notably, Mr. K states that he likes how he is feeling.

Mr. K’s wife says that his condition is a clear change from his baseline demeanor: soft-spoken and mild-mannered.

Mr. K reports that his symptoms started approximately 10 days earlier, after he returned from a cruise with his wife. During the cruise, he used a scopolamine patch to prevent motion sickness. Mr. K and his wife say that they believe that the scopolamine patch caused his symptoms.

Can scopolamine cause mania?

a) No

b) Yes; this is well-documented in the literature

c) It is theoretically possible because of scopolamine’s antidepressant and central anticholinergic effects

TREATMENT Lithium, close follow up

Mr. K has no history of psychiatric illness or substance use and no recent use of psychoactive substances—other than scopolamine—that could trigger a manic episode. His family history is significant for a younger brother who had a single manic episode at age 12 and a suicide attempt as a young adult.

Mr. K works full-time on rotating shifts—including some overnight shifts—as a manufacturing supervisor at a biotechnology company. He has been unable to work since returning from the cruise because of his psychiatric symptoms.

Mr. K is started on sustained-release (SR) lithium, 900 mg/d. In addition, the psychiatrist advises Mr. K to continue taking clonazepam, 0.5 to 1 mg as needed, which the emergency medicine physician prescribed, for insomnia. Mr. K is referred to a psychiatric intensive outpatient program (IOP), 3 days a week for 2 weeks, and is advised to stay home from work until symptoms stabilize.

Mr. K follows up closely with the psychiatrist in the clinic, every 1 to 2 weeks for the first month, as well as by several telephone and e-mail contacts. Lithium SR is titrated to 1,200 mg/d, to a therapeutic serum level of 1.1 mEq/L. Clonazepam is switched to quetiapine, 25 to 50 mg as needed, to address ongoing insomnia and to reduce the risk of dependency on clonazepam.

Mr. K’s mania gradually abates. He finishes the IOP and returns to work 3 weeks after his initial presentation. At an office visit, Mr. K’s wife gives the psychiatrist 2 scientific articles documenting the antidepressant effect of scopolamine.1,2 Mr. K and his wife both continue to believe that Mr. K’s manic episode was triggered by the scopolamine patch he used while on the cruise. They think this is important because Mr. K believes he would not have developed mania otherwise, and he does not want to take a mood stabilizer for the rest of his life.

The author’s observations

There are several proposed mechanisms for scopolamine’s antidepressant effect (Table 1).3-9 Scopolamine blocks central muscarinic cholinergic receptors, which reduces production of glutamate receptors and leads to reduced glutamate transmission and neurotoxicity.3,4 Scopolamine—similar to ketamine—could enhance synaptogenesis and synaptic signaling.5,6 Also, by blocking muscarinic autoreceptors, scopolamine results in an acute upregulation of acetylcholine release, which, in turn, influences the nicotinic, dopamine, serotonin, and neuropeptide Y systems. This action could contribute to anti-inflammatory effects, all of which can benefit mood.7-9 These antidepressant mechanisms also could explain why, theoretically, scopolamine could precipitate mania in a person predisposed to mental illness.

Proposed by Janowsky et al10 in 1972, the cholinergic−adrenergic balance hypothesis of affective disorders suggests that depression represents an excess of central cholinergic tone over adrenergic tone, and that mania represents the opposite imbalance. Several lines of evidence in the literature support this theory. For example, depressed patients have been found to have hypersensitive central cholinergic receptors.11,12 Also, central cholinesterase inhibition has been shown to affect pituitary hormone and epinephrine levels via central muscarinic receptors.13 In addition, scopolamine has been shown to attenuate these effects via the central anti-muscarinic mechanism.14

Rapid antidepressant therapy. Scopolamine is being studied as a rapid antidepressant treatment, although it usually is administered via IV infusion, rather than patch form, in trials.15-17 IV ketamine is another therapy being investigated for rapid treatment of depression, which might have downstream mechanisms of action related to scopolamine.5,18 Electroconvulsive therapy is a well-known for its quick antidepressant effect, which could involve synaptogenesis or effects on the neuroendocrine system.19 Sleep deprivation also can produce a rapid antidepressant effect20 (Table 21,2,5,6,15,16,18-20).

OUTCOME Prone to motion sickness

Approximately 3.5 months after his initial presentation, Mr. K continues to do well with treatment. He is euthymic and functioning well at work. He and his wife are preparing for the birth of their first child.

Mr. K is prone to motion sickness, and asks if he can take over-the-counter dimenhydrinate tablets for long car rides. He reports that dimenhydrinate has worked well for him in the past without triggering manic episodes, and he did not anticipate needing to take it very often.

What would you tell Mr. K about dimenhydrinate for motion sickness during car rides?

a) Mr. K should not take dimenhydrinate to prevent motion sickness because he experienced a manic episode triggered by a scopolamine patch

b) Mr. K can use dimenhydrinate as much as he wants to prevent motion sickness because it poses no risk of mania

c) Mr. K can use dimenhydrinate with caution and sparingly on a trial basis, as long as he is taking his mood stabilizer

FOLLOW UP Cautious use

The psychiatrist advised Mr. K to take dimenhydrinate cautiously when needed for long car rides. The psychiatrist feels this is safe because Mr. K is taking a mood stabilizer (lithium). Also, although dimenhydrinate has anticholinergic properties, occasional use is thought to pose less risk of triggering mania than the constant anticholinergic exposure over several days with a scopolamine patch. (The scopolamine patch contains 1.5 mg of the drug delivered over 3 days [ie, 0.5 mg/d]. In trials of IV scopolamine for depression, the dosage was 0.4 mcg/kg/d administered over 3 consecutive days.15-17 For an adult weighing 70 kg, this would be equivalent to 0.24 mg/d. Therefore, using a scopolamine patch over 3 days would appear to deliver a robust antidepressant-level dosage, even taking into account possible lower bioavailability with transdermal administration compared with IV infusion.)

The psychiatrist concludes that sporadic use of dimenhydrinate tablets for motion sickness during occasional long car rides poses less of a risk for Mr. K of triggering mania than repeat use of a scopolamine patch.

The author’s observations

Mr. K’s case is notable for several reasons:

- Novelty. This might be the first report of scopolamine-induced mania in the literature. In clinical trials by Furey and Drevets,15 Drevets and Furey,16 and Ellis et al,17 no study participants who received scopolamine infusion developed mania or hypomania. Although it is possible that Mr. K’s manic episode could have occurred spontaneously and was coincidental to his scopolamine use, there are valid reasons why scopolamine could trigger mania in a vulnerable person.

- Biochemical insight. The case underscores the role of the muscarinic cholinergic system in regulating mood.10

- Rational medical care. Sensible clinical decision-making was needed when Mr. K asked about using dimenhydrinate for motion sickness during car rides. Although there might not be definitively correct answers for questions that arose during Mr. K’s care (in the absence of research literature), theoretical understanding of the antidepressant effects of anticholinergic medications helped inform the psychiatrist’s responses to Mr. K and his wife.

1. Drevets WC, Zarate CA Jr, Furey ML. Antidepressant effects of the muscarinic cholinergic receptor antagonist scopolamine: a review. Biol Psychiatry. 2013;73(12):1156-1163.

2. Jaffe RJ, Novakovic V, Peselow ED. Scopolamine as an antidepressant: a systematic review. Clin Neuropharmacol. 2013;36(1):24-26.

3. Rami A, Ausmeir F, Winckler J, et al. Differential effects of scopolamine on neuronal survival in ischemia and glutamate neurotoxicity: relationships to the excessive vulnerability of the dorsoseptal hippocampus. J Chem Neuroanat. 1997;13(3):201-208.

4. Benveniste M, Wilhelm J, Dingledine RJ, et al. Subunit-dependent modulation of kainate receptors by muscarinic acetylcholine receptors. Brain Res. 2010;1352:61-69.

5. Duman RS, Li N, Liu RJ, et al. Signaling pathways underlying the rapid antidepressant actions of ketamine. Neuropharmacology. 2012;62(1):35-41.

6. Voleti B, Navarria A, Liu R, et al. Scopolamine rapidly increases mammalian target of rapamycin complex 1 signaling, synaptogenesis, and antidepressant behavioral responses. Biol Psychiatry. 2013;74(10):742-749.

7. Overstreet DH, Friedman E, Mathé AA, et al. The Flinders Sensitive Line rat: a selectively bred putative animal model of depression. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2005;29(4-5):739-759.

8. Tizabi Y, Getachew B, Rezvani AH, et al. Antidepressant-like effects of nicotine and reduced nicotinic receptor binding in the Fawn-Hooded rat, an animal model of co-morbid depression and alcoholism. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2009;33(3):398-402.

9. Wang DW, Zhou RB, Yao YM. Role of cholinergic anti-inflammatory pathway in regulating host response and its interventional strategy for inflammatory diseases. Chin J Traumatol. 2009;12(6):355-364.

10. Janowsky DS, el-Yousef MK, Davis JM, et al. A cholinergic-adrenergic hypothesis of mania and depression. Lancet. 1972;2(7778):632-635.

11. Risch SC, Kalin NH, Janowsky DS. Cholinergic challenges in affective illness: behavioral and neuroendocrine correlates. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 1981;1(4):186-192.

12. Risch SC, Janowsky DS, Gillin JC. Muscarinic supersensitivity of anterior pituitary ACTH and β-endorphin release in major depressive illness. Peptides. 1983;4(5):789-792.

13. Risch SC, Janowsky DS, Mott MA, et al. Central and peripheral cholinesterase inhibition: effects on anterior pituitary and sympathomimetic function. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 1986;11(2):221-230.

14. Janowsky DS, Risch SC, Kennedy B, et al. Central muscarinic effects of physostigmine on mood, cardiovascular function, pituitary and adrenal neuroendocrine release. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 1986;89(2):150-154.

15. Furey ML, Drevets WC. Antidepressant efficacy of the antimuscarinic drug scopolamine: a randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2006;63(10):1121-1129.

16. Drevets WC, Furey ML. Replication of scopolamine’s antidepressant efficacy in major depressive disorder: a randomized, placebo-controlled clinical trial. Biol Psychiatry. 2010;67(5):432-438.

17. Ellis JS, Zarate CA Jr, Luckenbaugh DA, et al. Antidepressant treatment history as a predictor of response to scopolamine: clinical implications. J Affect Disord. 2014;162:39-42.

18. Newport DJ, Carpenter LL, McDonald WM, et al. Ketamine and other NMDA antagonists: early clinical trials and possible mechanisms in depression. Am J Psychiatry. 2015;172(10):950-966.

19. Bolwig TG. How does electroconvulsive therapy work? Theories on its mechanism. Can J Psychiatry. 2011;56(1):13-18.

20. Wu JC, Kelsoe JR, Schachat C, et al. Rapid and sustained antidepressant response with sleep deprivation and chronotherapy in bipolar disorder. Biol Psychiatry. 2009;66(3):298-301.

1. Drevets WC, Zarate CA Jr, Furey ML. Antidepressant effects of the muscarinic cholinergic receptor antagonist scopolamine: a review. Biol Psychiatry. 2013;73(12):1156-1163.

2. Jaffe RJ, Novakovic V, Peselow ED. Scopolamine as an antidepressant: a systematic review. Clin Neuropharmacol. 2013;36(1):24-26.

3. Rami A, Ausmeir F, Winckler J, et al. Differential effects of scopolamine on neuronal survival in ischemia and glutamate neurotoxicity: relationships to the excessive vulnerability of the dorsoseptal hippocampus. J Chem Neuroanat. 1997;13(3):201-208.

4. Benveniste M, Wilhelm J, Dingledine RJ, et al. Subunit-dependent modulation of kainate receptors by muscarinic acetylcholine receptors. Brain Res. 2010;1352:61-69.

5. Duman RS, Li N, Liu RJ, et al. Signaling pathways underlying the rapid antidepressant actions of ketamine. Neuropharmacology. 2012;62(1):35-41.

6. Voleti B, Navarria A, Liu R, et al. Scopolamine rapidly increases mammalian target of rapamycin complex 1 signaling, synaptogenesis, and antidepressant behavioral responses. Biol Psychiatry. 2013;74(10):742-749.

7. Overstreet DH, Friedman E, Mathé AA, et al. The Flinders Sensitive Line rat: a selectively bred putative animal model of depression. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2005;29(4-5):739-759.

8. Tizabi Y, Getachew B, Rezvani AH, et al. Antidepressant-like effects of nicotine and reduced nicotinic receptor binding in the Fawn-Hooded rat, an animal model of co-morbid depression and alcoholism. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2009;33(3):398-402.

9. Wang DW, Zhou RB, Yao YM. Role of cholinergic anti-inflammatory pathway in regulating host response and its interventional strategy for inflammatory diseases. Chin J Traumatol. 2009;12(6):355-364.

10. Janowsky DS, el-Yousef MK, Davis JM, et al. A cholinergic-adrenergic hypothesis of mania and depression. Lancet. 1972;2(7778):632-635.

11. Risch SC, Kalin NH, Janowsky DS. Cholinergic challenges in affective illness: behavioral and neuroendocrine correlates. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 1981;1(4):186-192.

12. Risch SC, Janowsky DS, Gillin JC. Muscarinic supersensitivity of anterior pituitary ACTH and β-endorphin release in major depressive illness. Peptides. 1983;4(5):789-792.

13. Risch SC, Janowsky DS, Mott MA, et al. Central and peripheral cholinesterase inhibition: effects on anterior pituitary and sympathomimetic function. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 1986;11(2):221-230.

14. Janowsky DS, Risch SC, Kennedy B, et al. Central muscarinic effects of physostigmine on mood, cardiovascular function, pituitary and adrenal neuroendocrine release. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 1986;89(2):150-154.

15. Furey ML, Drevets WC. Antidepressant efficacy of the antimuscarinic drug scopolamine: a randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2006;63(10):1121-1129.

16. Drevets WC, Furey ML. Replication of scopolamine’s antidepressant efficacy in major depressive disorder: a randomized, placebo-controlled clinical trial. Biol Psychiatry. 2010;67(5):432-438.

17. Ellis JS, Zarate CA Jr, Luckenbaugh DA, et al. Antidepressant treatment history as a predictor of response to scopolamine: clinical implications. J Affect Disord. 2014;162:39-42.

18. Newport DJ, Carpenter LL, McDonald WM, et al. Ketamine and other NMDA antagonists: early clinical trials and possible mechanisms in depression. Am J Psychiatry. 2015;172(10):950-966.

19. Bolwig TG. How does electroconvulsive therapy work? Theories on its mechanism. Can J Psychiatry. 2011;56(1):13-18.

20. Wu JC, Kelsoe JR, Schachat C, et al. Rapid and sustained antidepressant response with sleep deprivation and chronotherapy in bipolar disorder. Biol Psychiatry. 2009;66(3):298-301.