User login

When Should an IVC Filter Be Used to Treat a DVT?

Case

A 67-year-old man with a history of hypertension presents with a swollen right lower extremity. An ultrasound reveals a DVT, and he is commenced on low-molecular-weight heparin and warfarin. Two days later, he develops slurred speech and right-sided weakness. A head CT reveals an intracranial hemorrhage. When should an inferior vena cava (IVC) filter be utilized for treatment of DVT?

Overview

It is estimated that 350,000 to 600,000 Americans develop a VTE each year.1 Patients with a DVT are at high risk of developing a pulmonary embolism (PE). In a multicenter study, nearly 40% of patients admitted with a DVT had evidence of a PE on ventilation perfusion scan.2 Treatment of a DVT is aimed at preventing the extension of the DVT and embolization.3 The American College of Chest Physicians (ACCP) recommends anticoagulation as the primary DVT treatment (Grade 1A).4 However, IVC filters might be considered when anticoagulation is contraindicated.

In 1868, Trousseau created the conceptual model of surgical interruption of the IVC to prevent PE. However, it wasn’t until 1959 by Bottini that the surgical interruption was successfully performed.5 The Mobin-Uddin filter was introduced in 1967 as the first mechanical IVC filter.6 IVC filters mechanically trap the DVT, preventing emboli from traveling into the pulmonary vasculature.7

There are two classes of IVC filters: permanent filters and removable filters. Removable filters include both temporary filters and retrievable filters. Temporary filters are attached to a catheter that exits the skin and therefore must be removed due to the risk of infection and embolization.7 Retrievable filters are similar in design to permanent filters but are designed to be removed. However, this must be done with caution, as neointimal hyperplasia can prevent removal or cause vessel wall damage upon removal.8

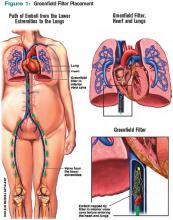

IVC filters are inserted into the vena cava percutaneously via the femoral or jugular approach under fluoroscopy or ultrasound guidance (see Figure 1, p. 16). The filters typically are placed infrarenally, unless there is an indication for a suprarenal filter (e.g., renal vein thrombosis or IVC thrombus extending above the renal veins).7 Complete IVC thrombosis is an absolute contraindication to IVC filter placement, and the relative contraindications include significant coagulopathy and bacteremia.9

The incidence of complications related to IVC filter placement is 4% to 11%. Complications include:

- Insertion-site thrombosis;

- IVC thrombosis;

- Recurrent DVT postphlebitic syndrome;

- Filter migration;

- Erosion of the filter through the vessel wall; and

- Vena caval obstruction.10

A review of the National Hospital Discharge Survey database for trends in IVC filter use in the U.S. found a dramatic increase in the use of IVC filters from 1979 to 1999—to 49,000 patients from 2,000 patients with IVC filters in place. The indications for IVC filter use vary such that it is imperative there are well-designed trials and guidelines to guide appropriate use.11

The Evidence

The 2008 ACCP guidelines on VTE management follow a grading system that classifies recommendations as Grade 1 (strong) or Grade 2 (weak), and classifies the quality of evidence as A (high), B (moderate), or C (low).12 The ACCP guidelines’ recommended first-line treatment for a confirmed DVT is anticoagulation with subcutaneous low-molecular-weight heparin, intravenous unfractionated heparin, monitored subcutaneous heparin, fixed-dose subcutaneous unfractionated heparin, or subcutaneous fondaparinux (all Grade 1A recommendations). The ACCP recommends against the routine use of an IVC filter in addition to anticoagulants (Grade 1A). However, for patients with acute proximal DVT, if anticoagulant therapy is not possible because of the risk of bleeding, IVC filter placement is recommended (Grade 1C). If a patient requires an IVC filter for treatment of an acute DVT as an alternative to anticoagulation, it is recommended to start anticoagulant therapy once the risk of bleeding resolves (Grade 1C).4

The 2008 ACCP guidelines for IVC filter use have a few important changes from the 2004 version. First, the IVC filter placement recommendation for patients with contraindications to anticoagulation was strengthened from Grade 2C to Grade 1C. Second, the 2008 guidelines omitted the early recommendation of IVC filter use for recurrent VTE, despite adequate anticoagulation (Grade 2C).13

Only one randomized study has evaluated the efficacy of IVC filters. All other studies of IVC filters are retrospective or prospective case series.

The PREPIC study randomized 400 patients with proximal DVT considered to be at high risk for PE to receive either an IVC filter or no IVC filter. Additionally, patients were randomized to receive enoxaparin or unfractionated heparin as a bridge to warfarin therapy, which was continued for at least three months. The primary endpoints were recurrent DVT, PE, major bleeding, or death. The patients were followed up at day 12, two years, and then annually up to eight years following randomization.14 At day 12, there were fewer PEs in the group that received filters (OR 0.22, 95% CI, 0.05-0.90). However, at year two, there was no significant difference in PE development in the filter group compared with the no-filter group (OR 0.50, 95% CI, 0.19-1.33).

Additionally, at year two, the filter group was more likely to develop recurrent DVT (OR 1.87, 95% CI, 1.10-3.20). At year eight, there was a significant reduction in the number of PEs in the filter group versus the no-filter group (6.2% vs.15.1%, P=0.008). However, at eight-year followup, IVC filter use was associated with increased DVT (35.7% vs. 27.5%, P=0.042). There was no difference in mortality between the two groups.

In summary, the use of IVC filters was associated with decreased incidence of PE at eight years, offset by higher rates of recurrent DVT and no overall mortality benefit.14,15 Importantly, the indications for IVC filter use in this study differ from the current ACCP guidelines; all patients were given concomitant anticoagulation for at least three months, which might not be possible in patients for whom the ACCP recommends IVC filters.

There are no randomized studies to compare the efficacy of permanent IVC filters and retrievable filters for PE prevention. A retrospective study comparing the clinical effectiveness of the two filter types reported no difference in the rates of symptomatic PE (permanent filter 4% vs. retrievable filter 4.7%, P=0.67) or DVT (11.3% vs. 12.6%, P=0.59). In addition, the frequency of symptomatic IVC thrombosis was similar (1.1% vs. 0.5%, p=0.39).16 A paper reviewing the efficacy of IVC filters reported that permanent filters were associated with a 0%-6.2% rate of PE versus a 0%-1.9% rate with retrievable filters.7 Notably, these studies were not randomized controlled trials—rather, case series—and the indications for IVC filters were not necessarily those currently recommended by the ACCP.

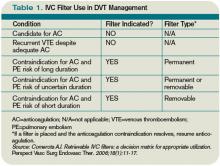

Due to the long-term complications of permanent IVC filters, it is suggested that a retrievable IVC filter be used for patients with temporary contraindications to anticoagulation.17 Comerata et al created a clinical decision-making tool for picking the type of filter to employ. If the duration of contraindication to anticoagulation is short or uncertain, a retrievable filter is recommended.18 Table 1 (p. 15) outlines the recommendations for IVC filter placement.

There are no randomized controlled trials to guide the use of concomitant anticoagulation after filter insertion, although this intervention may be beneficial to prevent DVT propagation, recurrence, or IVC filter thrombosis.5 A meta-analysis of 14 studies evaluating the rates of VTE after IVC filter placement demonstrated a non-statistically significant trend toward fewer VTE events in the patients with an IVC filter and concomitant anticoagulation in comparison with those who solely had an IVC filter (OR 0.64, 95% CI, 0.35-1.2). The duration and degree of anticoagulation was not presented in all of the studies in the meta-analysis, therefore limiting the analysis.19

In addition to the ACCP guidelines, there have been other proposed indications for IVC filter use, including recurrent VTE despite anticoagulation, chronic recurrent PE with pulmonary hypertension, extensive free-floating iliofemoral thrombus, and thrombolysis of ilio-caval thrombus.20 The ACCP guidelines do not specifically address these individual indications, and at this time there are no randomized controlled trials to guide IVC filter use in these cases.

Back to the Case

Our patient developed a significant complication from anticoagulation. Current ACCP guidelines recommend an IVC filter if anticoagulant therapy is contraindicated (Grade 1C). The anticoagulation was discontinued and a retrievable IVC filter was placed. Once a patient no longer has a contraindication for anticoagulation, the ACCP recommends restarting a conventional course of anticoagulation. Thus, once the patient can tolerate anticoagulation, consideration will be given to removal of the retrievable filter.

Bottom Line

An IVC filter should be considered in patients with a DVT who have a contraindication to anticoagulation. Other indications for IVC filter use are not supported by the current literature. TH

Drs. Bhogal and Eid are hospitalist fellows and instructors at Johns Hopkins Bayview Medical Center in Baltimore. Dr. Kantsiper is a hospitalist and assistant professor at Bayview Medical Center.

References

- The Surgeon General’s Call to Action to Prevent Deep Vein Thrombosis and Pulmonary Embolism. U.S. Department of Health & Human Services Web site. Available at: www.surgeongeneral.gov/topics/deepvein/. Accessed Jan. 25, 2010.

- Moser KM, Fedullo PR, LitteJohn JK, Crawford R. Frequent asymptomatic pulmonary embolism in patients with deep venous thrombosis. JAMA. 1994;271(3):223-225.

- Bates SM, Ginsberg JS. Treatment of deep vein thrombosis. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:268-277.

- Kearon C, Kahn SR, Agnelli G, Goldhaber S, Raskob GE, Comerota AJ, American College of Chest Physicians. Antithrombotic therapy for venous theomboembolic disease: American College of Chest Physicians Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guidelines (8th Edition). Chest. 2008;133(6 Suppl):454S-545S.

- Becker DM, Philbrick JT, Selby JB. Inferior vena cava filters. Indications, safety, effectiveness. Arch Intern Med. 1992;152(10):1985-1994.

- Streiff MB. Vena caval filters: a comprehensive review. Blood. 2000;95(12):3669-3677.

- Chung J, Owen RJ. Using inferior vena cava filters to prevent pulmonary embolism. Can Fam Physician. 2008;54(1):49-55.

- Ku GH. Billett HH. Long lives, short indications. The case for removable inferior cava filters. Thromb Haemost. 2005;93(1):17-22.

- Stavropoulos WS. Inferior vena cava filters. Tech Vasc Interv Radiol. 2004;7(2):91-95.

- Crowther MA. Inferior vena cava filters in the management of venous thromboembolism. Am J Med. 2007;120(10 Suppl 2):S13–S17.

- Stein PD, Kayali F, Olson RE. Twenty-one-year trends in the use of inferior vena cava filters. Arch Intern Med. 2004;164(14):1541-1545.

- Guyatt G, Gutterman D, Baumann MH, et al. Grading strength of recommendations and quality of evidence in clinical guidelines: report from an American College of Chest Physicians task force. Chest. 2006;129(1):174-181.

- Büller HR, Agnelli G, Hull RD, Hyers TM, Prins MH, Raskob GE. Antithrombotic therapy for venous thromboembolic disease: the Seventh ACCP Conference on Antithrombotic and Thrombolytic Therapy. Chest. 2004;126(3 Suppl):401S-428S.

- Decousus H, Leizorovicz A, Parent F, et al. A clinical trial of vena caval filters in the prevention of pulmonary embolism in patients with proximal deep-vein thrombosis. Prévention du Risque d’Embolie Pulmonaire par Interruption Cave Study Group. N Engl J Med. 1998;338(7):409-415.

- Decousus H, Barral F, Buchmuller-Cordier A, et al. Participating centers eight-year follow-up of patients with permanent vena cava filters in the prevention of pulmonary embolism: the PREPIC randomization croup. Circulation. 2005;112:416-422.

- Kim HS, Young MJ, Narayan AK, Liddell RP, Streiff MB. A comparison of clinical outcomes with retrievable and permanent inferior vena cava filters. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2008:19(3):393-399.

- Houman Fekrazad M, Lopes RD, Stashenko GJ, Alexander JH, Garcia D. Treatment of venous thromboembolism: guidelines translated for the clinician. J Thromb Thrombolysis. 2009; 28(3):270–275.

- Comerota AJ. Retrievable IVC filters: a decision matrix for appropriate utilization. Perspect Vasc Surg Endovasc Ther. 2006;18(1):11-17.

- Ray CE Jr, Prochazka A. The need for anticoagulation following inferior vena cava filter placement: systematic review. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2008; 31(2):316-324.

- Hajduk B, Tomkowski WZ, Malek G, Davidson BL. Vena cava filter occlusion and venous thromboembolism risk in persistently anticoagulated patients: A prospective, observational cohort study. Chest. 2009.

Case

A 67-year-old man with a history of hypertension presents with a swollen right lower extremity. An ultrasound reveals a DVT, and he is commenced on low-molecular-weight heparin and warfarin. Two days later, he develops slurred speech and right-sided weakness. A head CT reveals an intracranial hemorrhage. When should an inferior vena cava (IVC) filter be utilized for treatment of DVT?

Overview

It is estimated that 350,000 to 600,000 Americans develop a VTE each year.1 Patients with a DVT are at high risk of developing a pulmonary embolism (PE). In a multicenter study, nearly 40% of patients admitted with a DVT had evidence of a PE on ventilation perfusion scan.2 Treatment of a DVT is aimed at preventing the extension of the DVT and embolization.3 The American College of Chest Physicians (ACCP) recommends anticoagulation as the primary DVT treatment (Grade 1A).4 However, IVC filters might be considered when anticoagulation is contraindicated.

In 1868, Trousseau created the conceptual model of surgical interruption of the IVC to prevent PE. However, it wasn’t until 1959 by Bottini that the surgical interruption was successfully performed.5 The Mobin-Uddin filter was introduced in 1967 as the first mechanical IVC filter.6 IVC filters mechanically trap the DVT, preventing emboli from traveling into the pulmonary vasculature.7

There are two classes of IVC filters: permanent filters and removable filters. Removable filters include both temporary filters and retrievable filters. Temporary filters are attached to a catheter that exits the skin and therefore must be removed due to the risk of infection and embolization.7 Retrievable filters are similar in design to permanent filters but are designed to be removed. However, this must be done with caution, as neointimal hyperplasia can prevent removal or cause vessel wall damage upon removal.8

IVC filters are inserted into the vena cava percutaneously via the femoral or jugular approach under fluoroscopy or ultrasound guidance (see Figure 1, p. 16). The filters typically are placed infrarenally, unless there is an indication for a suprarenal filter (e.g., renal vein thrombosis or IVC thrombus extending above the renal veins).7 Complete IVC thrombosis is an absolute contraindication to IVC filter placement, and the relative contraindications include significant coagulopathy and bacteremia.9

The incidence of complications related to IVC filter placement is 4% to 11%. Complications include:

- Insertion-site thrombosis;

- IVC thrombosis;

- Recurrent DVT postphlebitic syndrome;

- Filter migration;

- Erosion of the filter through the vessel wall; and

- Vena caval obstruction.10

A review of the National Hospital Discharge Survey database for trends in IVC filter use in the U.S. found a dramatic increase in the use of IVC filters from 1979 to 1999—to 49,000 patients from 2,000 patients with IVC filters in place. The indications for IVC filter use vary such that it is imperative there are well-designed trials and guidelines to guide appropriate use.11

The Evidence

The 2008 ACCP guidelines on VTE management follow a grading system that classifies recommendations as Grade 1 (strong) or Grade 2 (weak), and classifies the quality of evidence as A (high), B (moderate), or C (low).12 The ACCP guidelines’ recommended first-line treatment for a confirmed DVT is anticoagulation with subcutaneous low-molecular-weight heparin, intravenous unfractionated heparin, monitored subcutaneous heparin, fixed-dose subcutaneous unfractionated heparin, or subcutaneous fondaparinux (all Grade 1A recommendations). The ACCP recommends against the routine use of an IVC filter in addition to anticoagulants (Grade 1A). However, for patients with acute proximal DVT, if anticoagulant therapy is not possible because of the risk of bleeding, IVC filter placement is recommended (Grade 1C). If a patient requires an IVC filter for treatment of an acute DVT as an alternative to anticoagulation, it is recommended to start anticoagulant therapy once the risk of bleeding resolves (Grade 1C).4

The 2008 ACCP guidelines for IVC filter use have a few important changes from the 2004 version. First, the IVC filter placement recommendation for patients with contraindications to anticoagulation was strengthened from Grade 2C to Grade 1C. Second, the 2008 guidelines omitted the early recommendation of IVC filter use for recurrent VTE, despite adequate anticoagulation (Grade 2C).13

Only one randomized study has evaluated the efficacy of IVC filters. All other studies of IVC filters are retrospective or prospective case series.

The PREPIC study randomized 400 patients with proximal DVT considered to be at high risk for PE to receive either an IVC filter or no IVC filter. Additionally, patients were randomized to receive enoxaparin or unfractionated heparin as a bridge to warfarin therapy, which was continued for at least three months. The primary endpoints were recurrent DVT, PE, major bleeding, or death. The patients were followed up at day 12, two years, and then annually up to eight years following randomization.14 At day 12, there were fewer PEs in the group that received filters (OR 0.22, 95% CI, 0.05-0.90). However, at year two, there was no significant difference in PE development in the filter group compared with the no-filter group (OR 0.50, 95% CI, 0.19-1.33).

Additionally, at year two, the filter group was more likely to develop recurrent DVT (OR 1.87, 95% CI, 1.10-3.20). At year eight, there was a significant reduction in the number of PEs in the filter group versus the no-filter group (6.2% vs.15.1%, P=0.008). However, at eight-year followup, IVC filter use was associated with increased DVT (35.7% vs. 27.5%, P=0.042). There was no difference in mortality between the two groups.

In summary, the use of IVC filters was associated with decreased incidence of PE at eight years, offset by higher rates of recurrent DVT and no overall mortality benefit.14,15 Importantly, the indications for IVC filter use in this study differ from the current ACCP guidelines; all patients were given concomitant anticoagulation for at least three months, which might not be possible in patients for whom the ACCP recommends IVC filters.

There are no randomized studies to compare the efficacy of permanent IVC filters and retrievable filters for PE prevention. A retrospective study comparing the clinical effectiveness of the two filter types reported no difference in the rates of symptomatic PE (permanent filter 4% vs. retrievable filter 4.7%, P=0.67) or DVT (11.3% vs. 12.6%, P=0.59). In addition, the frequency of symptomatic IVC thrombosis was similar (1.1% vs. 0.5%, p=0.39).16 A paper reviewing the efficacy of IVC filters reported that permanent filters were associated with a 0%-6.2% rate of PE versus a 0%-1.9% rate with retrievable filters.7 Notably, these studies were not randomized controlled trials—rather, case series—and the indications for IVC filters were not necessarily those currently recommended by the ACCP.

Due to the long-term complications of permanent IVC filters, it is suggested that a retrievable IVC filter be used for patients with temporary contraindications to anticoagulation.17 Comerata et al created a clinical decision-making tool for picking the type of filter to employ. If the duration of contraindication to anticoagulation is short or uncertain, a retrievable filter is recommended.18 Table 1 (p. 15) outlines the recommendations for IVC filter placement.

There are no randomized controlled trials to guide the use of concomitant anticoagulation after filter insertion, although this intervention may be beneficial to prevent DVT propagation, recurrence, or IVC filter thrombosis.5 A meta-analysis of 14 studies evaluating the rates of VTE after IVC filter placement demonstrated a non-statistically significant trend toward fewer VTE events in the patients with an IVC filter and concomitant anticoagulation in comparison with those who solely had an IVC filter (OR 0.64, 95% CI, 0.35-1.2). The duration and degree of anticoagulation was not presented in all of the studies in the meta-analysis, therefore limiting the analysis.19

In addition to the ACCP guidelines, there have been other proposed indications for IVC filter use, including recurrent VTE despite anticoagulation, chronic recurrent PE with pulmonary hypertension, extensive free-floating iliofemoral thrombus, and thrombolysis of ilio-caval thrombus.20 The ACCP guidelines do not specifically address these individual indications, and at this time there are no randomized controlled trials to guide IVC filter use in these cases.

Back to the Case

Our patient developed a significant complication from anticoagulation. Current ACCP guidelines recommend an IVC filter if anticoagulant therapy is contraindicated (Grade 1C). The anticoagulation was discontinued and a retrievable IVC filter was placed. Once a patient no longer has a contraindication for anticoagulation, the ACCP recommends restarting a conventional course of anticoagulation. Thus, once the patient can tolerate anticoagulation, consideration will be given to removal of the retrievable filter.

Bottom Line

An IVC filter should be considered in patients with a DVT who have a contraindication to anticoagulation. Other indications for IVC filter use are not supported by the current literature. TH

Drs. Bhogal and Eid are hospitalist fellows and instructors at Johns Hopkins Bayview Medical Center in Baltimore. Dr. Kantsiper is a hospitalist and assistant professor at Bayview Medical Center.

References

- The Surgeon General’s Call to Action to Prevent Deep Vein Thrombosis and Pulmonary Embolism. U.S. Department of Health & Human Services Web site. Available at: www.surgeongeneral.gov/topics/deepvein/. Accessed Jan. 25, 2010.

- Moser KM, Fedullo PR, LitteJohn JK, Crawford R. Frequent asymptomatic pulmonary embolism in patients with deep venous thrombosis. JAMA. 1994;271(3):223-225.

- Bates SM, Ginsberg JS. Treatment of deep vein thrombosis. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:268-277.

- Kearon C, Kahn SR, Agnelli G, Goldhaber S, Raskob GE, Comerota AJ, American College of Chest Physicians. Antithrombotic therapy for venous theomboembolic disease: American College of Chest Physicians Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guidelines (8th Edition). Chest. 2008;133(6 Suppl):454S-545S.

- Becker DM, Philbrick JT, Selby JB. Inferior vena cava filters. Indications, safety, effectiveness. Arch Intern Med. 1992;152(10):1985-1994.

- Streiff MB. Vena caval filters: a comprehensive review. Blood. 2000;95(12):3669-3677.

- Chung J, Owen RJ. Using inferior vena cava filters to prevent pulmonary embolism. Can Fam Physician. 2008;54(1):49-55.

- Ku GH. Billett HH. Long lives, short indications. The case for removable inferior cava filters. Thromb Haemost. 2005;93(1):17-22.

- Stavropoulos WS. Inferior vena cava filters. Tech Vasc Interv Radiol. 2004;7(2):91-95.

- Crowther MA. Inferior vena cava filters in the management of venous thromboembolism. Am J Med. 2007;120(10 Suppl 2):S13–S17.

- Stein PD, Kayali F, Olson RE. Twenty-one-year trends in the use of inferior vena cava filters. Arch Intern Med. 2004;164(14):1541-1545.

- Guyatt G, Gutterman D, Baumann MH, et al. Grading strength of recommendations and quality of evidence in clinical guidelines: report from an American College of Chest Physicians task force. Chest. 2006;129(1):174-181.

- Büller HR, Agnelli G, Hull RD, Hyers TM, Prins MH, Raskob GE. Antithrombotic therapy for venous thromboembolic disease: the Seventh ACCP Conference on Antithrombotic and Thrombolytic Therapy. Chest. 2004;126(3 Suppl):401S-428S.

- Decousus H, Leizorovicz A, Parent F, et al. A clinical trial of vena caval filters in the prevention of pulmonary embolism in patients with proximal deep-vein thrombosis. Prévention du Risque d’Embolie Pulmonaire par Interruption Cave Study Group. N Engl J Med. 1998;338(7):409-415.

- Decousus H, Barral F, Buchmuller-Cordier A, et al. Participating centers eight-year follow-up of patients with permanent vena cava filters in the prevention of pulmonary embolism: the PREPIC randomization croup. Circulation. 2005;112:416-422.

- Kim HS, Young MJ, Narayan AK, Liddell RP, Streiff MB. A comparison of clinical outcomes with retrievable and permanent inferior vena cava filters. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2008:19(3):393-399.

- Houman Fekrazad M, Lopes RD, Stashenko GJ, Alexander JH, Garcia D. Treatment of venous thromboembolism: guidelines translated for the clinician. J Thromb Thrombolysis. 2009; 28(3):270–275.

- Comerota AJ. Retrievable IVC filters: a decision matrix for appropriate utilization. Perspect Vasc Surg Endovasc Ther. 2006;18(1):11-17.

- Ray CE Jr, Prochazka A. The need for anticoagulation following inferior vena cava filter placement: systematic review. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2008; 31(2):316-324.

- Hajduk B, Tomkowski WZ, Malek G, Davidson BL. Vena cava filter occlusion and venous thromboembolism risk in persistently anticoagulated patients: A prospective, observational cohort study. Chest. 2009.

Case

A 67-year-old man with a history of hypertension presents with a swollen right lower extremity. An ultrasound reveals a DVT, and he is commenced on low-molecular-weight heparin and warfarin. Two days later, he develops slurred speech and right-sided weakness. A head CT reveals an intracranial hemorrhage. When should an inferior vena cava (IVC) filter be utilized for treatment of DVT?

Overview

It is estimated that 350,000 to 600,000 Americans develop a VTE each year.1 Patients with a DVT are at high risk of developing a pulmonary embolism (PE). In a multicenter study, nearly 40% of patients admitted with a DVT had evidence of a PE on ventilation perfusion scan.2 Treatment of a DVT is aimed at preventing the extension of the DVT and embolization.3 The American College of Chest Physicians (ACCP) recommends anticoagulation as the primary DVT treatment (Grade 1A).4 However, IVC filters might be considered when anticoagulation is contraindicated.

In 1868, Trousseau created the conceptual model of surgical interruption of the IVC to prevent PE. However, it wasn’t until 1959 by Bottini that the surgical interruption was successfully performed.5 The Mobin-Uddin filter was introduced in 1967 as the first mechanical IVC filter.6 IVC filters mechanically trap the DVT, preventing emboli from traveling into the pulmonary vasculature.7

There are two classes of IVC filters: permanent filters and removable filters. Removable filters include both temporary filters and retrievable filters. Temporary filters are attached to a catheter that exits the skin and therefore must be removed due to the risk of infection and embolization.7 Retrievable filters are similar in design to permanent filters but are designed to be removed. However, this must be done with caution, as neointimal hyperplasia can prevent removal or cause vessel wall damage upon removal.8

IVC filters are inserted into the vena cava percutaneously via the femoral or jugular approach under fluoroscopy or ultrasound guidance (see Figure 1, p. 16). The filters typically are placed infrarenally, unless there is an indication for a suprarenal filter (e.g., renal vein thrombosis or IVC thrombus extending above the renal veins).7 Complete IVC thrombosis is an absolute contraindication to IVC filter placement, and the relative contraindications include significant coagulopathy and bacteremia.9

The incidence of complications related to IVC filter placement is 4% to 11%. Complications include:

- Insertion-site thrombosis;

- IVC thrombosis;

- Recurrent DVT postphlebitic syndrome;

- Filter migration;

- Erosion of the filter through the vessel wall; and

- Vena caval obstruction.10

A review of the National Hospital Discharge Survey database for trends in IVC filter use in the U.S. found a dramatic increase in the use of IVC filters from 1979 to 1999—to 49,000 patients from 2,000 patients with IVC filters in place. The indications for IVC filter use vary such that it is imperative there are well-designed trials and guidelines to guide appropriate use.11

The Evidence

The 2008 ACCP guidelines on VTE management follow a grading system that classifies recommendations as Grade 1 (strong) or Grade 2 (weak), and classifies the quality of evidence as A (high), B (moderate), or C (low).12 The ACCP guidelines’ recommended first-line treatment for a confirmed DVT is anticoagulation with subcutaneous low-molecular-weight heparin, intravenous unfractionated heparin, monitored subcutaneous heparin, fixed-dose subcutaneous unfractionated heparin, or subcutaneous fondaparinux (all Grade 1A recommendations). The ACCP recommends against the routine use of an IVC filter in addition to anticoagulants (Grade 1A). However, for patients with acute proximal DVT, if anticoagulant therapy is not possible because of the risk of bleeding, IVC filter placement is recommended (Grade 1C). If a patient requires an IVC filter for treatment of an acute DVT as an alternative to anticoagulation, it is recommended to start anticoagulant therapy once the risk of bleeding resolves (Grade 1C).4

The 2008 ACCP guidelines for IVC filter use have a few important changes from the 2004 version. First, the IVC filter placement recommendation for patients with contraindications to anticoagulation was strengthened from Grade 2C to Grade 1C. Second, the 2008 guidelines omitted the early recommendation of IVC filter use for recurrent VTE, despite adequate anticoagulation (Grade 2C).13

Only one randomized study has evaluated the efficacy of IVC filters. All other studies of IVC filters are retrospective or prospective case series.

The PREPIC study randomized 400 patients with proximal DVT considered to be at high risk for PE to receive either an IVC filter or no IVC filter. Additionally, patients were randomized to receive enoxaparin or unfractionated heparin as a bridge to warfarin therapy, which was continued for at least three months. The primary endpoints were recurrent DVT, PE, major bleeding, or death. The patients were followed up at day 12, two years, and then annually up to eight years following randomization.14 At day 12, there were fewer PEs in the group that received filters (OR 0.22, 95% CI, 0.05-0.90). However, at year two, there was no significant difference in PE development in the filter group compared with the no-filter group (OR 0.50, 95% CI, 0.19-1.33).

Additionally, at year two, the filter group was more likely to develop recurrent DVT (OR 1.87, 95% CI, 1.10-3.20). At year eight, there was a significant reduction in the number of PEs in the filter group versus the no-filter group (6.2% vs.15.1%, P=0.008). However, at eight-year followup, IVC filter use was associated with increased DVT (35.7% vs. 27.5%, P=0.042). There was no difference in mortality between the two groups.

In summary, the use of IVC filters was associated with decreased incidence of PE at eight years, offset by higher rates of recurrent DVT and no overall mortality benefit.14,15 Importantly, the indications for IVC filter use in this study differ from the current ACCP guidelines; all patients were given concomitant anticoagulation for at least three months, which might not be possible in patients for whom the ACCP recommends IVC filters.

There are no randomized studies to compare the efficacy of permanent IVC filters and retrievable filters for PE prevention. A retrospective study comparing the clinical effectiveness of the two filter types reported no difference in the rates of symptomatic PE (permanent filter 4% vs. retrievable filter 4.7%, P=0.67) or DVT (11.3% vs. 12.6%, P=0.59). In addition, the frequency of symptomatic IVC thrombosis was similar (1.1% vs. 0.5%, p=0.39).16 A paper reviewing the efficacy of IVC filters reported that permanent filters were associated with a 0%-6.2% rate of PE versus a 0%-1.9% rate with retrievable filters.7 Notably, these studies were not randomized controlled trials—rather, case series—and the indications for IVC filters were not necessarily those currently recommended by the ACCP.

Due to the long-term complications of permanent IVC filters, it is suggested that a retrievable IVC filter be used for patients with temporary contraindications to anticoagulation.17 Comerata et al created a clinical decision-making tool for picking the type of filter to employ. If the duration of contraindication to anticoagulation is short or uncertain, a retrievable filter is recommended.18 Table 1 (p. 15) outlines the recommendations for IVC filter placement.

There are no randomized controlled trials to guide the use of concomitant anticoagulation after filter insertion, although this intervention may be beneficial to prevent DVT propagation, recurrence, or IVC filter thrombosis.5 A meta-analysis of 14 studies evaluating the rates of VTE after IVC filter placement demonstrated a non-statistically significant trend toward fewer VTE events in the patients with an IVC filter and concomitant anticoagulation in comparison with those who solely had an IVC filter (OR 0.64, 95% CI, 0.35-1.2). The duration and degree of anticoagulation was not presented in all of the studies in the meta-analysis, therefore limiting the analysis.19

In addition to the ACCP guidelines, there have been other proposed indications for IVC filter use, including recurrent VTE despite anticoagulation, chronic recurrent PE with pulmonary hypertension, extensive free-floating iliofemoral thrombus, and thrombolysis of ilio-caval thrombus.20 The ACCP guidelines do not specifically address these individual indications, and at this time there are no randomized controlled trials to guide IVC filter use in these cases.

Back to the Case

Our patient developed a significant complication from anticoagulation. Current ACCP guidelines recommend an IVC filter if anticoagulant therapy is contraindicated (Grade 1C). The anticoagulation was discontinued and a retrievable IVC filter was placed. Once a patient no longer has a contraindication for anticoagulation, the ACCP recommends restarting a conventional course of anticoagulation. Thus, once the patient can tolerate anticoagulation, consideration will be given to removal of the retrievable filter.

Bottom Line

An IVC filter should be considered in patients with a DVT who have a contraindication to anticoagulation. Other indications for IVC filter use are not supported by the current literature. TH

Drs. Bhogal and Eid are hospitalist fellows and instructors at Johns Hopkins Bayview Medical Center in Baltimore. Dr. Kantsiper is a hospitalist and assistant professor at Bayview Medical Center.

References

- The Surgeon General’s Call to Action to Prevent Deep Vein Thrombosis and Pulmonary Embolism. U.S. Department of Health & Human Services Web site. Available at: www.surgeongeneral.gov/topics/deepvein/. Accessed Jan. 25, 2010.

- Moser KM, Fedullo PR, LitteJohn JK, Crawford R. Frequent asymptomatic pulmonary embolism in patients with deep venous thrombosis. JAMA. 1994;271(3):223-225.

- Bates SM, Ginsberg JS. Treatment of deep vein thrombosis. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:268-277.

- Kearon C, Kahn SR, Agnelli G, Goldhaber S, Raskob GE, Comerota AJ, American College of Chest Physicians. Antithrombotic therapy for venous theomboembolic disease: American College of Chest Physicians Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guidelines (8th Edition). Chest. 2008;133(6 Suppl):454S-545S.

- Becker DM, Philbrick JT, Selby JB. Inferior vena cava filters. Indications, safety, effectiveness. Arch Intern Med. 1992;152(10):1985-1994.

- Streiff MB. Vena caval filters: a comprehensive review. Blood. 2000;95(12):3669-3677.

- Chung J, Owen RJ. Using inferior vena cava filters to prevent pulmonary embolism. Can Fam Physician. 2008;54(1):49-55.

- Ku GH. Billett HH. Long lives, short indications. The case for removable inferior cava filters. Thromb Haemost. 2005;93(1):17-22.

- Stavropoulos WS. Inferior vena cava filters. Tech Vasc Interv Radiol. 2004;7(2):91-95.

- Crowther MA. Inferior vena cava filters in the management of venous thromboembolism. Am J Med. 2007;120(10 Suppl 2):S13–S17.

- Stein PD, Kayali F, Olson RE. Twenty-one-year trends in the use of inferior vena cava filters. Arch Intern Med. 2004;164(14):1541-1545.

- Guyatt G, Gutterman D, Baumann MH, et al. Grading strength of recommendations and quality of evidence in clinical guidelines: report from an American College of Chest Physicians task force. Chest. 2006;129(1):174-181.

- Büller HR, Agnelli G, Hull RD, Hyers TM, Prins MH, Raskob GE. Antithrombotic therapy for venous thromboembolic disease: the Seventh ACCP Conference on Antithrombotic and Thrombolytic Therapy. Chest. 2004;126(3 Suppl):401S-428S.

- Decousus H, Leizorovicz A, Parent F, et al. A clinical trial of vena caval filters in the prevention of pulmonary embolism in patients with proximal deep-vein thrombosis. Prévention du Risque d’Embolie Pulmonaire par Interruption Cave Study Group. N Engl J Med. 1998;338(7):409-415.

- Decousus H, Barral F, Buchmuller-Cordier A, et al. Participating centers eight-year follow-up of patients with permanent vena cava filters in the prevention of pulmonary embolism: the PREPIC randomization croup. Circulation. 2005;112:416-422.

- Kim HS, Young MJ, Narayan AK, Liddell RP, Streiff MB. A comparison of clinical outcomes with retrievable and permanent inferior vena cava filters. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2008:19(3):393-399.

- Houman Fekrazad M, Lopes RD, Stashenko GJ, Alexander JH, Garcia D. Treatment of venous thromboembolism: guidelines translated for the clinician. J Thromb Thrombolysis. 2009; 28(3):270–275.

- Comerota AJ. Retrievable IVC filters: a decision matrix for appropriate utilization. Perspect Vasc Surg Endovasc Ther. 2006;18(1):11-17.

- Ray CE Jr, Prochazka A. The need for anticoagulation following inferior vena cava filter placement: systematic review. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2008; 31(2):316-324.

- Hajduk B, Tomkowski WZ, Malek G, Davidson BL. Vena cava filter occlusion and venous thromboembolism risk in persistently anticoagulated patients: A prospective, observational cohort study. Chest. 2009.

In the Literature: January 2010

In This Edition

Literature at a Glance

A guide to this month’s studies

- Resident duty hours and ICU patient outcomes

- Effect of ER boarding on patient outcomes

- ED voicemail signout of patients

- Adequacy of patient signouts

- D-dimer use in patients with low suspicion of pulmonary embolism

- Patient involvement in medication reconciliation

- Effects of on-screen reminders on outcomes

Decreased ICU Duty Hours Does Not Affect Patient Mortality

Clinical question: Does the reduction in work hours for residents affect mortality in medical and surgical ICUs?

Background: A reduction in work hours for residents was enforced in July 2003. Several prior studies using administrative or claims data did not show an association of the reduced work hours for residents with mortality in teaching hospitals when compared with nonteaching hospitals.

Study design: Observational retrospective registry cohort.

Setting: Twelve academic, 12 community, and 16 nonteaching hospitals in the U.S.

Synopsis: Data from 230,151 patients were extracted as post-hoc analysis from a voluntary clinical registry that uses a well-validated severity-of-illness scoring system. The exposure was defined as date of admission to ICU within two years before and after the reform. Hospitals were categorized as academic, community with residents, or nonteaching. Sophisticated statistical analyses were performed, including interaction terms for teaching status and time. To test the effect the reduced work hours had on mortality, the mortality trends of academic hospitals and community hospitals with residents were compared with the baseline trend of nonteaching hospitals. After risk adjustments, all hospitals had improved in-hospital and ICU mortality after the reform. None of the statistical improvements were significantly different.

Study limitations include the selection bias, as only highly motivated hospitals participating in the registry were included, and misclassification bias, as not all hospitals implemented the reform at the same time. Nevertheless, this study supports the consistent literature on the topic and adds a more robust assessment of severity of illness.

Bottom line: The restriction on resident duty hours does not appear to affect patient mortality.

Citation: Prasad M, Iwashyna TJ, Christie JD, et al. Effect of work-hours regulations on intensive care unit mortality in United States teaching hospitals. Crit Care Med. 2009;37(9):2564-2569.

Emergency Department “Boarding” Results in Undesirable Events

Clinical question: What is the frequency and nature of undesirable events experienced by patients who “board” in the ED?

Background: Hospital crowding results in patients spending extended amounts of time—also known as “boarding”—in the ED as they wait for an inpatient bed. Prior studies have shown that longer ED boarding times are associated with adverse outcomes. Few studies have examined the nature and frequency of undesirable events that patients experience while boarding.

Study design: Retrospective chart review.

Setting: Urban academic medical center.

Synopsis: In this pilot study, authors reviewed the charts of patients who were treated in the ED and subsequently admitted to the hospital on three different days during the study period (n=151). More than a quarter (27.8%) of patients experienced an undesirable event, such as missing a scheduled medication, while they were boarding. Older patients, those with comorbid illnesses, and those who endured prolonged boarding times (greater than six hours) were more likely to experience an undesirable event. In addition, 3.3% of patients experienced such adverse events as suboptimal blood pressure control, hypotension, hypoxia, or arrhythmia.

This study was performed at a single center and lacks a comparison group (i.e., nonboarded patients). It is intended to serve as an exploratory study for future analysis of adverse events in boarded patients.

Bottom line: Undesirable events are common among boarded patients, although it is unknown whether they are more common than in nonboarded patients.

Citation: Liu SW, Thomas SH, Gordon JA, Hamedani AG, Weissman JS. A pilot study examining undesirable events among emergency-department boarded patients awaiting inpatient beds. Ann Emerg Med. 2009;54(3):381-385.

Emergency Department Signout via Voicemail Yields Mixed Reviews

Clinical question: How does traditional, oral signout from emergency providers to inpatient medicine physicians compare to dictated, voicemail signout?

Background: Communication failures contribute to errors in care transition from ED to inpatient medicine units. Signout between ED providers and internal medicine (IM) physicians is typically oral (“synchronous communication”). It is not known how dictated signout to a voicemail system (“asynchronous communication”) affects the quality and safety of handoff communications.

Study design: Prospective, pre-post analysis.

Setting: A 944-bed urban academic medical center in Connecticut.

Synopsis: Surveys were administered to all IM and ED providers before and after the implementation of a voicemail signout system. In the new system, ED providers dictated signout for stable patients, rather than giving traditional synchronous telephone signout. It was the responsibility of the admitting IM physician to listen to the voicemail after receiving a text notification that a patient was being admitted.

ED providers recorded signouts in 89.5% of medicine admissions. However, voicemails were accessed only 58.5% of the time by receiving physicians. All ED providers and 56% of IM physicians believed signout was easier following the voicemail intervention. Overall, ED providers gave the quality, content, and accuracy of their signout communication higher ratings than IM physicians did; 69% of all providers felt the interaction among participants was worse following the intervention. There was no change in the rate of perceived adverse events or ICU transfers within 24 hours after admission.

This intervention was a QI initiative at a single center. Mixed results and small sample size limit generalizability of the study.

Bottom line: Asynchronous signout by voicemail increased efficiency, particularly among ED providers but decreased perceived quality of interaction between medical providers without obviously affecting patient safety.

Citation: Horwitz LI, Parwani V, Shah NR, et al. Evaluation of an asynchronous physician voicemail sign-out for emergency department admissions. Ann Emerg Med. 2009;54:368-378.

Patient Signout Is Not Uniformly Comprehensive and Often Lacks Critical Information

Clinical question: Do signouts vary in the quality and quantity of information, and what are the various factors affecting signout quality?

Background: Miscommunication during transfers of responsibility for hospitalized patients is common and can result in harm. Recommendations for safe and effective handoffs emphasize key content, clear communication, senior staff supervision, and adequate time for questions. Still, little is known about adherence to these recommendations in clinical practice.

Study design: Prospective, observational cohort.

Setting: Medical unit of an acute-care teaching hospital.

Synopsis: Oral signouts were audiotaped among IM house staff teams and the accompanying written signouts were collected for review of content. Signout sessions (n=88) included eight IM teams at one hospital and contained 503 patient signouts.

The median signout duration was 35 seconds (IQR 19-62) per patient. Key clinical information was present in just 62% of combined written or oral signouts. Most signouts included no questions from the recipient. Factors associated with higher rate of content inclusion included: familiarity with the patient, sense of responsibility (primary team vs. covering team), only one signout per day (as compared to sequential signout), presence of a senior resident, and comprehensive, written signouts.

Study limitations include the Hawthorne effect, as several participants mentioned that the presence of audiotape led to more comprehensive signouts than are typical. Also, the signout quality assessment in this study has not been validated with patient-safety outcomes.

Bottom line: Signouts among internal-medicine residents at this one hospital showed variability in terms of quantitative and qualitative information and often missed crucial information about patient care.

Citation: Horwitz LI, Moin T, Krumholz HM, Wang L, Bradley EH. What are covering doctors told about their patients? Analysis of sign-out among internal medicine house staff. Qual Saf Health Care. 2009;18(4):248-255.

Negative D-Dimer Test Can Safely Exclude Pulmonary Embolism in Patients at Low To Intermediate Clinical Risk

Clinical question: In patients with symptoms consistent with pulmonary embolism (PE), can evaluation with a clinical risk assessment tool and D-dimer assay identify patients who do not require CT angiography to exclude PE?

Background: D-dimer is a highly sensitive but nonspecific marker of VTE, and studies suggest that VTE can be ruled out without further imaging in patients with low clinical probability of disease and a negative D-dimer test. Nevertheless, this practice has not been adopted uniformly, and CT angiography (CTA) overuse continues.

Study design: Prospective registry cohort.

Setting: A 550-bed community teaching hospital in Chicago.

Synopsis: Consecutive patients presenting to the ED with symptoms suggestive of PE were evaluated with 1) revised Geneva score; 2) D-dimer assay; and 3) CTA. Among the 627 patients who underwent all three components of the evaluation, 44.8% were identified as low probability for PE by revised Geneva score, 52.6% as intermediate probability, and 2.6% as high probability. The overall prevalence of PE (using CTA as the gold standard) was very low (4.5%); just 2.1% of low-risk, 5.2% of intermediate-risk, and 31.2% of high-risk patients were ultimately found to have PE on CTA.

Using a cutoff of 1.2 mg/L, the D-dimer assay accurately detected all low- to intermediate-probability patients with PE (sensitivity and negative predictive value of 100%). One patient in the high probability group did have a PE, even though the patient had a D-dimer value <1.2 mg/L (sensitivity and NPV both 80%). Had diagnostic testing stopped after a negative D-dimer result in the low- to intermediate-probability patients, 172 CTAs (27%) would have been avoided.

Bottom line: In a low-prevalence cohort, no pulmonary emboli were identified by CTA in any patient with a low to intermediate clinical risk assessment and a negative quantitative D-dimer assay result.

Citation: Gupta RT, Kakarla RK, Kirshenbaum KJ, Tapson VF. D-dimers and efficacy of clinical risk estimation algorithms: sensitivity in evaluation of acute pulmonary embolism. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2009;193(2):425-430.

Patient Participation in Medication Reconciliation at Discharge Helps Detect Prescribing Discrepancies

Clinical question: Does the inclusion of a medication adherence counseling session during a hospital discharge reconciliation process reduce discrepancies in the final medication regimen?

Background: Inadvertent medication prescribing errors are an important cause of preventable adverse drug events and commonly occur at transitions of care. Although medication reconciliation processes can identify errors, the best strategies for implementation remain unclear.

Study design: Prospective, observational cohort.

Setting: A 550-bed teaching hospital in the Netherlands.

Synopsis: Of 437 patients admitted to a pulmonary ward and screened for eligibility, 267 were included in the analysis. A pharmacy specialist reviewed all available community prescription records, inpatient documentation, and discharge medication lists in an effort to identify discrepancies. Potential errors were discussed with the prescriber. Then, the pharmacy specialist interviewed the patient and provided additional counseling. Any new discrepancies were discussed with the prescriber. All questions raised by the pharmacist were recorded, as were all subsequent prescriber interventions.

The primary outcome measure was the number of interventions made as a result of pharmacy review. A total of 940 questions were asked. At least one intervention was recorded for 87% of patients before counseling (mean 2.7 interventions/patient) and for 97% of patients after (mean 5.3 interventions/patient). Discrepancies were addressed for 63.7% of patients before counseling and 72.5% after. Pharmacotherapy was optimized for 67.2% of patients before counseling and 76.3% after.

Bottom line: Patient engagement in the medication reconciliation process incrementally improves the quality of the history and helps identify clinically meaningful discrepancies at the time of hospital discharge.

Citation: Karapinar-Carkit F, Borgsteede S, Zoer J, Smit HJ, Egberts AC, van den Bemt P. Effect of medication reconciliation with and without patient counseling on the number of pharmaceutical interventions among patients discharged from the hospital. Ann Pharmacother. 2009;43(6):1001-1010.

Computer-Based Reminders Have Small to Modest Effect on Care Processes

Clinical question: Do on-screen, computer-based clinical reminders improve adherence to target processes of care or clinical outcomes?

Background: Gaps between practice guidelines and routine care are caused, in part, by the inability of clinicians to access or recall information at the point of care. Although automated reminder systems offer the promise of “just in time” recommendations, studies of electronic reminders have demonstrated mixed results.

Study design: Literature review and meta-analysis.

Setting: Multiple databases and information repositories, including MEDLINE, EMBASE, and CINAHL.

Synopsis: The authors conducted a literature search to identify randomized and quasi-randomized controlled trials measuring the effect of computer-based reminders on process measures or clinical outcomes. To avoid statistical challenges inherent in unit-of-analysis errors, the authors reported median improvement in process adherence or median change in clinical endpoints.

Out of a pool of 2,036 citations, 28 studies detailing 32 comparative analyses were included. Across the 28 studies, reminders resulted in a median improvement in target process adherence of 4.2% (3.3% for prescribing behavior, 2.8% for test ordering). Eight comparisons reported dichotomous clinical endpoints and collectively showed a median absolute improvement of 2.5%.

The greatest contribution to measured treatment effects came from large academic centers with well-established electronic health records and robust informatics departments. No characteristics of the reminder system or the clinical context were associated with the magnitude of impact. A potential limitation in reporting median effects across studies is that all studies were given equal weight.

Bottom line: Electronic reminders appear to have a small, positive effect on clinician adherence to recommended processes, although it is uncertain what contextual or design features are responsible for the greatest treatment effect.

Citation: Shojania K, Jennings A, Mayhew A, Ramsay CR, Eccles MP, Grimshaw J. The effects of on-screen, point of care computer reminders on processes and outcomes of care. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009(3):CD001096. TH

In This Edition

Literature at a Glance

A guide to this month’s studies

- Resident duty hours and ICU patient outcomes

- Effect of ER boarding on patient outcomes

- ED voicemail signout of patients

- Adequacy of patient signouts

- D-dimer use in patients with low suspicion of pulmonary embolism

- Patient involvement in medication reconciliation

- Effects of on-screen reminders on outcomes

Decreased ICU Duty Hours Does Not Affect Patient Mortality

Clinical question: Does the reduction in work hours for residents affect mortality in medical and surgical ICUs?

Background: A reduction in work hours for residents was enforced in July 2003. Several prior studies using administrative or claims data did not show an association of the reduced work hours for residents with mortality in teaching hospitals when compared with nonteaching hospitals.

Study design: Observational retrospective registry cohort.

Setting: Twelve academic, 12 community, and 16 nonteaching hospitals in the U.S.

Synopsis: Data from 230,151 patients were extracted as post-hoc analysis from a voluntary clinical registry that uses a well-validated severity-of-illness scoring system. The exposure was defined as date of admission to ICU within two years before and after the reform. Hospitals were categorized as academic, community with residents, or nonteaching. Sophisticated statistical analyses were performed, including interaction terms for teaching status and time. To test the effect the reduced work hours had on mortality, the mortality trends of academic hospitals and community hospitals with residents were compared with the baseline trend of nonteaching hospitals. After risk adjustments, all hospitals had improved in-hospital and ICU mortality after the reform. None of the statistical improvements were significantly different.

Study limitations include the selection bias, as only highly motivated hospitals participating in the registry were included, and misclassification bias, as not all hospitals implemented the reform at the same time. Nevertheless, this study supports the consistent literature on the topic and adds a more robust assessment of severity of illness.

Bottom line: The restriction on resident duty hours does not appear to affect patient mortality.

Citation: Prasad M, Iwashyna TJ, Christie JD, et al. Effect of work-hours regulations on intensive care unit mortality in United States teaching hospitals. Crit Care Med. 2009;37(9):2564-2569.

Emergency Department “Boarding” Results in Undesirable Events

Clinical question: What is the frequency and nature of undesirable events experienced by patients who “board” in the ED?

Background: Hospital crowding results in patients spending extended amounts of time—also known as “boarding”—in the ED as they wait for an inpatient bed. Prior studies have shown that longer ED boarding times are associated with adverse outcomes. Few studies have examined the nature and frequency of undesirable events that patients experience while boarding.

Study design: Retrospective chart review.

Setting: Urban academic medical center.

Synopsis: In this pilot study, authors reviewed the charts of patients who were treated in the ED and subsequently admitted to the hospital on three different days during the study period (n=151). More than a quarter (27.8%) of patients experienced an undesirable event, such as missing a scheduled medication, while they were boarding. Older patients, those with comorbid illnesses, and those who endured prolonged boarding times (greater than six hours) were more likely to experience an undesirable event. In addition, 3.3% of patients experienced such adverse events as suboptimal blood pressure control, hypotension, hypoxia, or arrhythmia.

This study was performed at a single center and lacks a comparison group (i.e., nonboarded patients). It is intended to serve as an exploratory study for future analysis of adverse events in boarded patients.

Bottom line: Undesirable events are common among boarded patients, although it is unknown whether they are more common than in nonboarded patients.

Citation: Liu SW, Thomas SH, Gordon JA, Hamedani AG, Weissman JS. A pilot study examining undesirable events among emergency-department boarded patients awaiting inpatient beds. Ann Emerg Med. 2009;54(3):381-385.

Emergency Department Signout via Voicemail Yields Mixed Reviews

Clinical question: How does traditional, oral signout from emergency providers to inpatient medicine physicians compare to dictated, voicemail signout?

Background: Communication failures contribute to errors in care transition from ED to inpatient medicine units. Signout between ED providers and internal medicine (IM) physicians is typically oral (“synchronous communication”). It is not known how dictated signout to a voicemail system (“asynchronous communication”) affects the quality and safety of handoff communications.

Study design: Prospective, pre-post analysis.

Setting: A 944-bed urban academic medical center in Connecticut.

Synopsis: Surveys were administered to all IM and ED providers before and after the implementation of a voicemail signout system. In the new system, ED providers dictated signout for stable patients, rather than giving traditional synchronous telephone signout. It was the responsibility of the admitting IM physician to listen to the voicemail after receiving a text notification that a patient was being admitted.

ED providers recorded signouts in 89.5% of medicine admissions. However, voicemails were accessed only 58.5% of the time by receiving physicians. All ED providers and 56% of IM physicians believed signout was easier following the voicemail intervention. Overall, ED providers gave the quality, content, and accuracy of their signout communication higher ratings than IM physicians did; 69% of all providers felt the interaction among participants was worse following the intervention. There was no change in the rate of perceived adverse events or ICU transfers within 24 hours after admission.

This intervention was a QI initiative at a single center. Mixed results and small sample size limit generalizability of the study.

Bottom line: Asynchronous signout by voicemail increased efficiency, particularly among ED providers but decreased perceived quality of interaction between medical providers without obviously affecting patient safety.

Citation: Horwitz LI, Parwani V, Shah NR, et al. Evaluation of an asynchronous physician voicemail sign-out for emergency department admissions. Ann Emerg Med. 2009;54:368-378.

Patient Signout Is Not Uniformly Comprehensive and Often Lacks Critical Information

Clinical question: Do signouts vary in the quality and quantity of information, and what are the various factors affecting signout quality?

Background: Miscommunication during transfers of responsibility for hospitalized patients is common and can result in harm. Recommendations for safe and effective handoffs emphasize key content, clear communication, senior staff supervision, and adequate time for questions. Still, little is known about adherence to these recommendations in clinical practice.

Study design: Prospective, observational cohort.

Setting: Medical unit of an acute-care teaching hospital.

Synopsis: Oral signouts were audiotaped among IM house staff teams and the accompanying written signouts were collected for review of content. Signout sessions (n=88) included eight IM teams at one hospital and contained 503 patient signouts.

The median signout duration was 35 seconds (IQR 19-62) per patient. Key clinical information was present in just 62% of combined written or oral signouts. Most signouts included no questions from the recipient. Factors associated with higher rate of content inclusion included: familiarity with the patient, sense of responsibility (primary team vs. covering team), only one signout per day (as compared to sequential signout), presence of a senior resident, and comprehensive, written signouts.

Study limitations include the Hawthorne effect, as several participants mentioned that the presence of audiotape led to more comprehensive signouts than are typical. Also, the signout quality assessment in this study has not been validated with patient-safety outcomes.

Bottom line: Signouts among internal-medicine residents at this one hospital showed variability in terms of quantitative and qualitative information and often missed crucial information about patient care.

Citation: Horwitz LI, Moin T, Krumholz HM, Wang L, Bradley EH. What are covering doctors told about their patients? Analysis of sign-out among internal medicine house staff. Qual Saf Health Care. 2009;18(4):248-255.

Negative D-Dimer Test Can Safely Exclude Pulmonary Embolism in Patients at Low To Intermediate Clinical Risk

Clinical question: In patients with symptoms consistent with pulmonary embolism (PE), can evaluation with a clinical risk assessment tool and D-dimer assay identify patients who do not require CT angiography to exclude PE?

Background: D-dimer is a highly sensitive but nonspecific marker of VTE, and studies suggest that VTE can be ruled out without further imaging in patients with low clinical probability of disease and a negative D-dimer test. Nevertheless, this practice has not been adopted uniformly, and CT angiography (CTA) overuse continues.

Study design: Prospective registry cohort.

Setting: A 550-bed community teaching hospital in Chicago.

Synopsis: Consecutive patients presenting to the ED with symptoms suggestive of PE were evaluated with 1) revised Geneva score; 2) D-dimer assay; and 3) CTA. Among the 627 patients who underwent all three components of the evaluation, 44.8% were identified as low probability for PE by revised Geneva score, 52.6% as intermediate probability, and 2.6% as high probability. The overall prevalence of PE (using CTA as the gold standard) was very low (4.5%); just 2.1% of low-risk, 5.2% of intermediate-risk, and 31.2% of high-risk patients were ultimately found to have PE on CTA.

Using a cutoff of 1.2 mg/L, the D-dimer assay accurately detected all low- to intermediate-probability patients with PE (sensitivity and negative predictive value of 100%). One patient in the high probability group did have a PE, even though the patient had a D-dimer value <1.2 mg/L (sensitivity and NPV both 80%). Had diagnostic testing stopped after a negative D-dimer result in the low- to intermediate-probability patients, 172 CTAs (27%) would have been avoided.

Bottom line: In a low-prevalence cohort, no pulmonary emboli were identified by CTA in any patient with a low to intermediate clinical risk assessment and a negative quantitative D-dimer assay result.

Citation: Gupta RT, Kakarla RK, Kirshenbaum KJ, Tapson VF. D-dimers and efficacy of clinical risk estimation algorithms: sensitivity in evaluation of acute pulmonary embolism. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2009;193(2):425-430.

Patient Participation in Medication Reconciliation at Discharge Helps Detect Prescribing Discrepancies

Clinical question: Does the inclusion of a medication adherence counseling session during a hospital discharge reconciliation process reduce discrepancies in the final medication regimen?

Background: Inadvertent medication prescribing errors are an important cause of preventable adverse drug events and commonly occur at transitions of care. Although medication reconciliation processes can identify errors, the best strategies for implementation remain unclear.

Study design: Prospective, observational cohort.

Setting: A 550-bed teaching hospital in the Netherlands.

Synopsis: Of 437 patients admitted to a pulmonary ward and screened for eligibility, 267 were included in the analysis. A pharmacy specialist reviewed all available community prescription records, inpatient documentation, and discharge medication lists in an effort to identify discrepancies. Potential errors were discussed with the prescriber. Then, the pharmacy specialist interviewed the patient and provided additional counseling. Any new discrepancies were discussed with the prescriber. All questions raised by the pharmacist were recorded, as were all subsequent prescriber interventions.

The primary outcome measure was the number of interventions made as a result of pharmacy review. A total of 940 questions were asked. At least one intervention was recorded for 87% of patients before counseling (mean 2.7 interventions/patient) and for 97% of patients after (mean 5.3 interventions/patient). Discrepancies were addressed for 63.7% of patients before counseling and 72.5% after. Pharmacotherapy was optimized for 67.2% of patients before counseling and 76.3% after.

Bottom line: Patient engagement in the medication reconciliation process incrementally improves the quality of the history and helps identify clinically meaningful discrepancies at the time of hospital discharge.

Citation: Karapinar-Carkit F, Borgsteede S, Zoer J, Smit HJ, Egberts AC, van den Bemt P. Effect of medication reconciliation with and without patient counseling on the number of pharmaceutical interventions among patients discharged from the hospital. Ann Pharmacother. 2009;43(6):1001-1010.

Computer-Based Reminders Have Small to Modest Effect on Care Processes

Clinical question: Do on-screen, computer-based clinical reminders improve adherence to target processes of care or clinical outcomes?

Background: Gaps between practice guidelines and routine care are caused, in part, by the inability of clinicians to access or recall information at the point of care. Although automated reminder systems offer the promise of “just in time” recommendations, studies of electronic reminders have demonstrated mixed results.

Study design: Literature review and meta-analysis.

Setting: Multiple databases and information repositories, including MEDLINE, EMBASE, and CINAHL.

Synopsis: The authors conducted a literature search to identify randomized and quasi-randomized controlled trials measuring the effect of computer-based reminders on process measures or clinical outcomes. To avoid statistical challenges inherent in unit-of-analysis errors, the authors reported median improvement in process adherence or median change in clinical endpoints.

Out of a pool of 2,036 citations, 28 studies detailing 32 comparative analyses were included. Across the 28 studies, reminders resulted in a median improvement in target process adherence of 4.2% (3.3% for prescribing behavior, 2.8% for test ordering). Eight comparisons reported dichotomous clinical endpoints and collectively showed a median absolute improvement of 2.5%.

The greatest contribution to measured treatment effects came from large academic centers with well-established electronic health records and robust informatics departments. No characteristics of the reminder system or the clinical context were associated with the magnitude of impact. A potential limitation in reporting median effects across studies is that all studies were given equal weight.

Bottom line: Electronic reminders appear to have a small, positive effect on clinician adherence to recommended processes, although it is uncertain what contextual or design features are responsible for the greatest treatment effect.

Citation: Shojania K, Jennings A, Mayhew A, Ramsay CR, Eccles MP, Grimshaw J. The effects of on-screen, point of care computer reminders on processes and outcomes of care. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009(3):CD001096. TH

In This Edition

Literature at a Glance

A guide to this month’s studies

- Resident duty hours and ICU patient outcomes

- Effect of ER boarding on patient outcomes

- ED voicemail signout of patients

- Adequacy of patient signouts

- D-dimer use in patients with low suspicion of pulmonary embolism

- Patient involvement in medication reconciliation

- Effects of on-screen reminders on outcomes

Decreased ICU Duty Hours Does Not Affect Patient Mortality

Clinical question: Does the reduction in work hours for residents affect mortality in medical and surgical ICUs?

Background: A reduction in work hours for residents was enforced in July 2003. Several prior studies using administrative or claims data did not show an association of the reduced work hours for residents with mortality in teaching hospitals when compared with nonteaching hospitals.

Study design: Observational retrospective registry cohort.

Setting: Twelve academic, 12 community, and 16 nonteaching hospitals in the U.S.

Synopsis: Data from 230,151 patients were extracted as post-hoc analysis from a voluntary clinical registry that uses a well-validated severity-of-illness scoring system. The exposure was defined as date of admission to ICU within two years before and after the reform. Hospitals were categorized as academic, community with residents, or nonteaching. Sophisticated statistical analyses were performed, including interaction terms for teaching status and time. To test the effect the reduced work hours had on mortality, the mortality trends of academic hospitals and community hospitals with residents were compared with the baseline trend of nonteaching hospitals. After risk adjustments, all hospitals had improved in-hospital and ICU mortality after the reform. None of the statistical improvements were significantly different.

Study limitations include the selection bias, as only highly motivated hospitals participating in the registry were included, and misclassification bias, as not all hospitals implemented the reform at the same time. Nevertheless, this study supports the consistent literature on the topic and adds a more robust assessment of severity of illness.

Bottom line: The restriction on resident duty hours does not appear to affect patient mortality.

Citation: Prasad M, Iwashyna TJ, Christie JD, et al. Effect of work-hours regulations on intensive care unit mortality in United States teaching hospitals. Crit Care Med. 2009;37(9):2564-2569.

Emergency Department “Boarding” Results in Undesirable Events

Clinical question: What is the frequency and nature of undesirable events experienced by patients who “board” in the ED?

Background: Hospital crowding results in patients spending extended amounts of time—also known as “boarding”—in the ED as they wait for an inpatient bed. Prior studies have shown that longer ED boarding times are associated with adverse outcomes. Few studies have examined the nature and frequency of undesirable events that patients experience while boarding.

Study design: Retrospective chart review.

Setting: Urban academic medical center.

Synopsis: In this pilot study, authors reviewed the charts of patients who were treated in the ED and subsequently admitted to the hospital on three different days during the study period (n=151). More than a quarter (27.8%) of patients experienced an undesirable event, such as missing a scheduled medication, while they were boarding. Older patients, those with comorbid illnesses, and those who endured prolonged boarding times (greater than six hours) were more likely to experience an undesirable event. In addition, 3.3% of patients experienced such adverse events as suboptimal blood pressure control, hypotension, hypoxia, or arrhythmia.

This study was performed at a single center and lacks a comparison group (i.e., nonboarded patients). It is intended to serve as an exploratory study for future analysis of adverse events in boarded patients.

Bottom line: Undesirable events are common among boarded patients, although it is unknown whether they are more common than in nonboarded patients.

Citation: Liu SW, Thomas SH, Gordon JA, Hamedani AG, Weissman JS. A pilot study examining undesirable events among emergency-department boarded patients awaiting inpatient beds. Ann Emerg Med. 2009;54(3):381-385.

Emergency Department Signout via Voicemail Yields Mixed Reviews

Clinical question: How does traditional, oral signout from emergency providers to inpatient medicine physicians compare to dictated, voicemail signout?

Background: Communication failures contribute to errors in care transition from ED to inpatient medicine units. Signout between ED providers and internal medicine (IM) physicians is typically oral (“synchronous communication”). It is not known how dictated signout to a voicemail system (“asynchronous communication”) affects the quality and safety of handoff communications.

Study design: Prospective, pre-post analysis.

Setting: A 944-bed urban academic medical center in Connecticut.

Synopsis: Surveys were administered to all IM and ED providers before and after the implementation of a voicemail signout system. In the new system, ED providers dictated signout for stable patients, rather than giving traditional synchronous telephone signout. It was the responsibility of the admitting IM physician to listen to the voicemail after receiving a text notification that a patient was being admitted.

ED providers recorded signouts in 89.5% of medicine admissions. However, voicemails were accessed only 58.5% of the time by receiving physicians. All ED providers and 56% of IM physicians believed signout was easier following the voicemail intervention. Overall, ED providers gave the quality, content, and accuracy of their signout communication higher ratings than IM physicians did; 69% of all providers felt the interaction among participants was worse following the intervention. There was no change in the rate of perceived adverse events or ICU transfers within 24 hours after admission.

This intervention was a QI initiative at a single center. Mixed results and small sample size limit generalizability of the study.

Bottom line: Asynchronous signout by voicemail increased efficiency, particularly among ED providers but decreased perceived quality of interaction between medical providers without obviously affecting patient safety.

Citation: Horwitz LI, Parwani V, Shah NR, et al. Evaluation of an asynchronous physician voicemail sign-out for emergency department admissions. Ann Emerg Med. 2009;54:368-378.

Patient Signout Is Not Uniformly Comprehensive and Often Lacks Critical Information

Clinical question: Do signouts vary in the quality and quantity of information, and what are the various factors affecting signout quality?

Background: Miscommunication during transfers of responsibility for hospitalized patients is common and can result in harm. Recommendations for safe and effective handoffs emphasize key content, clear communication, senior staff supervision, and adequate time for questions. Still, little is known about adherence to these recommendations in clinical practice.

Study design: Prospective, observational cohort.

Setting: Medical unit of an acute-care teaching hospital.

Synopsis: Oral signouts were audiotaped among IM house staff teams and the accompanying written signouts were collected for review of content. Signout sessions (n=88) included eight IM teams at one hospital and contained 503 patient signouts.