User login

Shrink Rap News: Brandon Marshall, the NFL, and borderline personality disorder

I am what you’d call an unwilling sports fan – and then just barely – in that I reside in a family where everyone else is riveted by sports, and by football in particular. The National Football League is the backdrop to my home life on Sundays, Mondays, and Thursdays, with Saturday reserved for college football, all the more so since both of my children have attended Big 10 universities. With that as a background, I was delighted when the Sept. 19 episode of the NFL’s “A Football Life,” focused on Brandon Marshall, the Chicago Bears wide receiver who has talked publicly about his personal struggles with borderline personality disorder.

While many psychiatric disorders are stigmatized by people who are unfamiliar with them, borderline personality disorder is likely the illness that gets most stigmatized within our profession. “Borderline” or “Cluster B” are sometimes uttered as code, to mean that a patient is difficult to work with, unlikeable, or perhaps even manipulative. We often blame patients for their behaviors in ways that we don’t when a patient is ill with an Axis I disorder, and few psychiatrists relish the opportunity to work with patients who have borderline personality disorder.

The television episode focused on Marshall’s football career, his legal struggles, and his interpersonal relationships both on and off the playing field. There were spotlights on many of the people who were affected by his troubling behavior. Marshall described his relationship with his best friend and quarterback, Jay Cutler, as, “We’re the couple that really love each other but shouldn’t be together.”

Cutler was interviewed. He described Marshall as an emotional man who loved media attention and who would lose his temper and hang on to grudges. They first played together for the Denver Broncos, and now both men play for the Chicago Bears.

Marshall’s agent was interviewed and made the point that Marshall had “…personally destroyed maybe five of my vacations.” Marshall’s former coach; his wife; his mother; and his psychiatrist, Dr. John Gunderson of McLean Hospital in Belmont, Mass., were all interviewed on the show.

The narrator for “A Football Life” described Marshall’s behavior as erratic, both on and off the field. Film clips were shown of Marshall losing his temper, kicking the ball off the field during a penalty, and celebrating excessively. His mother referred to his outbursts as “hissy fits,” and she noted, “We were all under the impression Brandon could control this.”

Despite his talent as a wide receiver – while playing for the Broncos, Marshall caught more than 100 passes in each of three consecutive seasons – the Broncos traded him to the Miami Dolphins. His career with the Broncos had been marked by a brief suspension for charges of drunk driving and domestic violence, and Marshall had had numerous arrests over the years. He finally was required to have a psychiatric assessment, and Marshall flew to Massachusetts for a day-long evaluation with Dr. Gunderson. Dr. Gunderson described Marshall at that meeting as “hostile and nondisclosing.”

In Miami, Marshall’s behavior continued to be a source of contention. His girlfriend, Michi, described him as remote and withdrawn. After a domestic dispute in which she was charged with stabbing him – charges that both denied and were later dropped – Marshall returned to see Dr. Gunderson and dedicated 3 months of his off-season to getting treatment.

Dr. Gunderson noted that on his return visit, “He was troubled enough by his behaviors and the difficulties they were causing for him.”

With a diagnosis of borderline personality disorder, Marshall became invested in learning about the disorder and devoted his days to intensive treatment, which included group therapy. He discussed the difficulties he has regulating his emotions and noted that he now had strategies to help him maintain control. Cutler noted that Marshall still loses his cool, but he quickly regains his composure, while in the past he could stay angry for days.

The rest of the show went on to document Marshall’s successes. He gained better control of his temper and became less difficult to work with. Coach Tony Sparano was interviewed, and both he and Marshall talked of Sparano’s role in providing emotional support to the football player. He was offered a $30 million contract extension with the Bears. He and Michi married, started the Brandon Marshall Foundation to support mental health education and treatment, and the couple announced in September that they are expecting twins.

Dr. Gunderson noted that Brandon Marshall’s openness about his disorder does a great deal to alleviate the stigma associated with borderline personality disorder.

“He’s an articulate and charismatic male football player,” he said. “This takes it out of the realm of something that’s about weak people.”

The special did not talk about whether Marshall was taking medications – it was implied that he wasn’t – or if he has continued in treatment. We think of borderline personality disorder as being resistant to treatments, and certainly not as a disorder that can be fixed with 3 months of treatment. It was noted that Marshall has some unusual assets in addition to his charismatic personality: He has a vocation he loves and is good at, and he has supportive relationships. A clip was shown of an appearance he and Michi had made on “The View,” where he credited her support as being key to his success.

As psychiatrists, there is a delicate balance when treating patients with personality disorders. On the one hand, we want them to take ownership for their behaviors in the hopes that they will be able to gain some control over them. To balance this, however, personality disorders can be as crippling as any illness we treat in psychiatry, and the prognosis for some people is dismal. While it may be helpful to have a diagnosis and an explanation, it’s not beneficial if the patient sees himself as the victim of an untreatable condition. The television special on Brandon Marshall did a wonderful job of presenting this disorder with a balance – as a problem that happens to people, perhaps because of their difficult childhoods – but one that the individual can learn to take control of in an empowering way.

We might imagine this remains an ongoing struggle for Marshall, not one that was treated and fixed. I, however, enjoyed watching an NFL production with a positive spin on what we think of as being such a devastating psychiatric disorder.

Dr. Miller is a coauthor of “Shrink Rap: Three Psychiatrists Explain Their Work” (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2011).

I am what you’d call an unwilling sports fan – and then just barely – in that I reside in a family where everyone else is riveted by sports, and by football in particular. The National Football League is the backdrop to my home life on Sundays, Mondays, and Thursdays, with Saturday reserved for college football, all the more so since both of my children have attended Big 10 universities. With that as a background, I was delighted when the Sept. 19 episode of the NFL’s “A Football Life,” focused on Brandon Marshall, the Chicago Bears wide receiver who has talked publicly about his personal struggles with borderline personality disorder.

While many psychiatric disorders are stigmatized by people who are unfamiliar with them, borderline personality disorder is likely the illness that gets most stigmatized within our profession. “Borderline” or “Cluster B” are sometimes uttered as code, to mean that a patient is difficult to work with, unlikeable, or perhaps even manipulative. We often blame patients for their behaviors in ways that we don’t when a patient is ill with an Axis I disorder, and few psychiatrists relish the opportunity to work with patients who have borderline personality disorder.

The television episode focused on Marshall’s football career, his legal struggles, and his interpersonal relationships both on and off the playing field. There were spotlights on many of the people who were affected by his troubling behavior. Marshall described his relationship with his best friend and quarterback, Jay Cutler, as, “We’re the couple that really love each other but shouldn’t be together.”

Cutler was interviewed. He described Marshall as an emotional man who loved media attention and who would lose his temper and hang on to grudges. They first played together for the Denver Broncos, and now both men play for the Chicago Bears.

Marshall’s agent was interviewed and made the point that Marshall had “…personally destroyed maybe five of my vacations.” Marshall’s former coach; his wife; his mother; and his psychiatrist, Dr. John Gunderson of McLean Hospital in Belmont, Mass., were all interviewed on the show.

The narrator for “A Football Life” described Marshall’s behavior as erratic, both on and off the field. Film clips were shown of Marshall losing his temper, kicking the ball off the field during a penalty, and celebrating excessively. His mother referred to his outbursts as “hissy fits,” and she noted, “We were all under the impression Brandon could control this.”

Despite his talent as a wide receiver – while playing for the Broncos, Marshall caught more than 100 passes in each of three consecutive seasons – the Broncos traded him to the Miami Dolphins. His career with the Broncos had been marked by a brief suspension for charges of drunk driving and domestic violence, and Marshall had had numerous arrests over the years. He finally was required to have a psychiatric assessment, and Marshall flew to Massachusetts for a day-long evaluation with Dr. Gunderson. Dr. Gunderson described Marshall at that meeting as “hostile and nondisclosing.”

In Miami, Marshall’s behavior continued to be a source of contention. His girlfriend, Michi, described him as remote and withdrawn. After a domestic dispute in which she was charged with stabbing him – charges that both denied and were later dropped – Marshall returned to see Dr. Gunderson and dedicated 3 months of his off-season to getting treatment.

Dr. Gunderson noted that on his return visit, “He was troubled enough by his behaviors and the difficulties they were causing for him.”

With a diagnosis of borderline personality disorder, Marshall became invested in learning about the disorder and devoted his days to intensive treatment, which included group therapy. He discussed the difficulties he has regulating his emotions and noted that he now had strategies to help him maintain control. Cutler noted that Marshall still loses his cool, but he quickly regains his composure, while in the past he could stay angry for days.

The rest of the show went on to document Marshall’s successes. He gained better control of his temper and became less difficult to work with. Coach Tony Sparano was interviewed, and both he and Marshall talked of Sparano’s role in providing emotional support to the football player. He was offered a $30 million contract extension with the Bears. He and Michi married, started the Brandon Marshall Foundation to support mental health education and treatment, and the couple announced in September that they are expecting twins.

Dr. Gunderson noted that Brandon Marshall’s openness about his disorder does a great deal to alleviate the stigma associated with borderline personality disorder.

“He’s an articulate and charismatic male football player,” he said. “This takes it out of the realm of something that’s about weak people.”

The special did not talk about whether Marshall was taking medications – it was implied that he wasn’t – or if he has continued in treatment. We think of borderline personality disorder as being resistant to treatments, and certainly not as a disorder that can be fixed with 3 months of treatment. It was noted that Marshall has some unusual assets in addition to his charismatic personality: He has a vocation he loves and is good at, and he has supportive relationships. A clip was shown of an appearance he and Michi had made on “The View,” where he credited her support as being key to his success.

As psychiatrists, there is a delicate balance when treating patients with personality disorders. On the one hand, we want them to take ownership for their behaviors in the hopes that they will be able to gain some control over them. To balance this, however, personality disorders can be as crippling as any illness we treat in psychiatry, and the prognosis for some people is dismal. While it may be helpful to have a diagnosis and an explanation, it’s not beneficial if the patient sees himself as the victim of an untreatable condition. The television special on Brandon Marshall did a wonderful job of presenting this disorder with a balance – as a problem that happens to people, perhaps because of their difficult childhoods – but one that the individual can learn to take control of in an empowering way.

We might imagine this remains an ongoing struggle for Marshall, not one that was treated and fixed. I, however, enjoyed watching an NFL production with a positive spin on what we think of as being such a devastating psychiatric disorder.

Dr. Miller is a coauthor of “Shrink Rap: Three Psychiatrists Explain Their Work” (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2011).

I am what you’d call an unwilling sports fan – and then just barely – in that I reside in a family where everyone else is riveted by sports, and by football in particular. The National Football League is the backdrop to my home life on Sundays, Mondays, and Thursdays, with Saturday reserved for college football, all the more so since both of my children have attended Big 10 universities. With that as a background, I was delighted when the Sept. 19 episode of the NFL’s “A Football Life,” focused on Brandon Marshall, the Chicago Bears wide receiver who has talked publicly about his personal struggles with borderline personality disorder.

While many psychiatric disorders are stigmatized by people who are unfamiliar with them, borderline personality disorder is likely the illness that gets most stigmatized within our profession. “Borderline” or “Cluster B” are sometimes uttered as code, to mean that a patient is difficult to work with, unlikeable, or perhaps even manipulative. We often blame patients for their behaviors in ways that we don’t when a patient is ill with an Axis I disorder, and few psychiatrists relish the opportunity to work with patients who have borderline personality disorder.

The television episode focused on Marshall’s football career, his legal struggles, and his interpersonal relationships both on and off the playing field. There were spotlights on many of the people who were affected by his troubling behavior. Marshall described his relationship with his best friend and quarterback, Jay Cutler, as, “We’re the couple that really love each other but shouldn’t be together.”

Cutler was interviewed. He described Marshall as an emotional man who loved media attention and who would lose his temper and hang on to grudges. They first played together for the Denver Broncos, and now both men play for the Chicago Bears.

Marshall’s agent was interviewed and made the point that Marshall had “…personally destroyed maybe five of my vacations.” Marshall’s former coach; his wife; his mother; and his psychiatrist, Dr. John Gunderson of McLean Hospital in Belmont, Mass., were all interviewed on the show.

The narrator for “A Football Life” described Marshall’s behavior as erratic, both on and off the field. Film clips were shown of Marshall losing his temper, kicking the ball off the field during a penalty, and celebrating excessively. His mother referred to his outbursts as “hissy fits,” and she noted, “We were all under the impression Brandon could control this.”

Despite his talent as a wide receiver – while playing for the Broncos, Marshall caught more than 100 passes in each of three consecutive seasons – the Broncos traded him to the Miami Dolphins. His career with the Broncos had been marked by a brief suspension for charges of drunk driving and domestic violence, and Marshall had had numerous arrests over the years. He finally was required to have a psychiatric assessment, and Marshall flew to Massachusetts for a day-long evaluation with Dr. Gunderson. Dr. Gunderson described Marshall at that meeting as “hostile and nondisclosing.”

In Miami, Marshall’s behavior continued to be a source of contention. His girlfriend, Michi, described him as remote and withdrawn. After a domestic dispute in which she was charged with stabbing him – charges that both denied and were later dropped – Marshall returned to see Dr. Gunderson and dedicated 3 months of his off-season to getting treatment.

Dr. Gunderson noted that on his return visit, “He was troubled enough by his behaviors and the difficulties they were causing for him.”

With a diagnosis of borderline personality disorder, Marshall became invested in learning about the disorder and devoted his days to intensive treatment, which included group therapy. He discussed the difficulties he has regulating his emotions and noted that he now had strategies to help him maintain control. Cutler noted that Marshall still loses his cool, but he quickly regains his composure, while in the past he could stay angry for days.

The rest of the show went on to document Marshall’s successes. He gained better control of his temper and became less difficult to work with. Coach Tony Sparano was interviewed, and both he and Marshall talked of Sparano’s role in providing emotional support to the football player. He was offered a $30 million contract extension with the Bears. He and Michi married, started the Brandon Marshall Foundation to support mental health education and treatment, and the couple announced in September that they are expecting twins.

Dr. Gunderson noted that Brandon Marshall’s openness about his disorder does a great deal to alleviate the stigma associated with borderline personality disorder.

“He’s an articulate and charismatic male football player,” he said. “This takes it out of the realm of something that’s about weak people.”

The special did not talk about whether Marshall was taking medications – it was implied that he wasn’t – or if he has continued in treatment. We think of borderline personality disorder as being resistant to treatments, and certainly not as a disorder that can be fixed with 3 months of treatment. It was noted that Marshall has some unusual assets in addition to his charismatic personality: He has a vocation he loves and is good at, and he has supportive relationships. A clip was shown of an appearance he and Michi had made on “The View,” where he credited her support as being key to his success.

As psychiatrists, there is a delicate balance when treating patients with personality disorders. On the one hand, we want them to take ownership for their behaviors in the hopes that they will be able to gain some control over them. To balance this, however, personality disorders can be as crippling as any illness we treat in psychiatry, and the prognosis for some people is dismal. While it may be helpful to have a diagnosis and an explanation, it’s not beneficial if the patient sees himself as the victim of an untreatable condition. The television special on Brandon Marshall did a wonderful job of presenting this disorder with a balance – as a problem that happens to people, perhaps because of their difficult childhoods – but one that the individual can learn to take control of in an empowering way.

We might imagine this remains an ongoing struggle for Marshall, not one that was treated and fixed. I, however, enjoyed watching an NFL production with a positive spin on what we think of as being such a devastating psychiatric disorder.

Dr. Miller is a coauthor of “Shrink Rap: Three Psychiatrists Explain Their Work” (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2011).

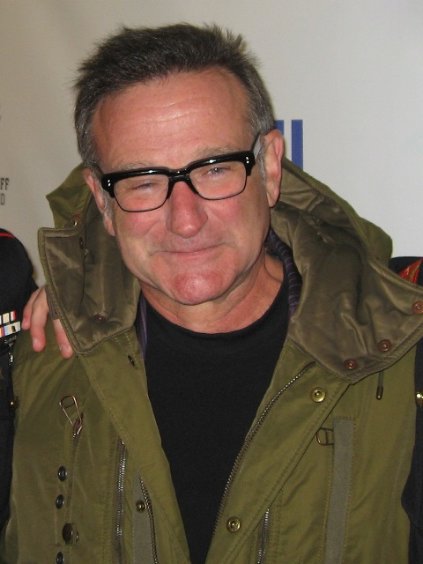

Shrink Rap News: Suicide hotline calls increase after Robin Williams’ death

National Suicide Prevention Day fell on Sept. 10 this year, surrounded by National Suicide Prevention Week Sept. 8-14. The conversation, as I’m sure everyone noticed, was focused on the suicide of actor Robin Williams. As we move out a few weeks, my patients – especially those who have contemplated ending their own lives – continue to talk about this tragic loss.

The fear is that the suicide of a celebrity will lead to an increase in the suicide rate in the general public – copycat suicides, if you will. In the month after Marilyn Monroe died of an overdose in 1962, the suicide rate rose by more than 10%. On the other hand, the death of a celebrity may lead to a decrease in the suicide rate, as happened after Kurt Cobain’s death from a self-inflicted gunshot wound in 1994. In the period after Cobain’s death, an effort was made to publicize resources for those who need help. The suicide rate dropped, while calls to hotlines rose.

After Robin Williams’ death, my own social media feeds were full of ads for the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline (NSPL), a hotline with the number 1-800-273-TALK. There are other hotlines, but this was the one I saw most. I wanted to learn about suicide hotlines, so I did a few things: I asked readers of our Shrink Rap blog to tell me about their experiences, and I called the hotline myself to see if I could learn about the structure of the organization, what resources they had to offer a distraught caller, and whether there had been a change in the number of calls they’d received in the time following Mr. Williams’ death.

I called from my cell phone, which is registered in Maryland, while sitting in my home in Baltimore City. The call was routed to Grassroots Crisis Intervention Center in Columbia, Md. Google Maps tells me the center is 25 miles from my house, and it would take me 32 minutes to drive there. In addition to being part of a network of 160 hotline centers across the country, Grassroots has a walk-in crisis center and a mobile treatment center, and is adjacent to a homeless shelter.

“Most of the people who call the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline are suicidal,” said Nicole DeChirico, director of crisis intervention services for Grassroots. “There is a gradation in suicidal thinking, but about 90% of our callers are considering it.”

“We first form rapport, and then we try to quickly assess if an attempt has already been made, and if they are in any danger. We use the assessment of suicidality that is put out by the NSPL. It’s a structured template that is used as a guideline.”

Ms. DeChirico noted that the people who man the hotlines have bachelor’s or master’s degrees – often in psychology, social work, counseling, or education. If feasible, a Safety Planning Intervention is implemented, based on the work of Barbara Stanley, Ph.D., at Columbia University in New York.

“We talk to people about what they need to do to feel safe. If they allow it, we set up a follow-up call. Of the total number of people who have attempted suicide once in the past and lived, 90%-96% never go on to attempt suicide again,” Ms. DeChirico noted. Suicide is a time-limited acute crisis.”

The Grassroots team can see patients on site while they wait for appointments with an outpatient clinician, and can send a mobile crisis team to those who need it if they are in the county served by the organization. I wondered if all 160 agencies that received calls from the NSPL could also provide crisis services.

Marcia Epstein, LMSW, was director of the Headquarters Counseling Center in Lawrence, Kan., from 1979 to 2013. The center became part of the first national suicide prevention hotline network, the National Hopeline Network, 1-800-SUICIDE, in 2001, and then became part of the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline, 1-800-274-TALK (8255), when that network began in January 2005.

“The types of programs and agencies which are part of NSPL vary greatly. The accreditation that allows them to be part of the NSPL network also varies. Some centers are staffed totally by licensed mental health therapists, while others might include trained volunteers and paid counselors who have no professional degree or licensure. Service may be delivered by phone, as well as in person, by text, and by live chat. In person might be on site or through mobile crisis outreach. Some centers are part of other organizations, while others are free-standing, and some serve entire states, while others serve geographically smaller regions,” Ms. Epstein explained in a series of e-mails. She noted that some centers assess and refer, while others, like Grassroots, are able to provide more counseling.

“So if it sounds like I’m saying there is little consistency between centers, yes, that is my experience. But the centers all bring strong commitment to preventing suicide.”

Ms. Epstein continued to discuss the power of the work done with hotline callers.

“The really helpful counseling comes from the heart, from connecting to people with caring and respect and patience, and using our skills in helping them stay safer through the crisis and then, when needed, to stay safer in the long run. It takes a lot of bravery from the people letting us help. And it takes a lot of creativity and flexibility in coming up together with realistic plans to support safety.”

I was curious about the patient response, and I found that was mixed. It was also notable that different patients found different forms of communication to be helpful.

A woman who identified herself only as “Virginia Woolf” wrote, “I have contacted the Samaritans on the [email protected] line because I could write to them via e-mail. I don’t like phones and I also know too many of the counselors on the local crisis line. Each time I was definitely close to suicide. I was in despair and I had the means at hand. I think what stopped me was knowing they would reply. They always did, within a few hours, but waiting for their reply kept me safe.”

Not every response was as positive.

One writer noted, “It was not a productive, supportive, or empathetic person. I felt like she was arrogant, judgmental, and didn’t really care about why I was calling.” The same writer, however, was able to find solace elsewhere. “I have texted CrisisChat and it was an excellent chat and I did feel better.”

Finally, Ms. DeChirico sent me information about the call volume from our local NPSL center in Columbia. From July 1, 2013, to July 31, 2014, the Lifeline received an average of 134 calls per month. December had the highest number of calls, with 163, while August had the lowest with 118. September, February, and April all had 120 calls or fewer.

Robin Williams died on Aug. 11, 2014, and the center received 200 calls in August – a 49% increase over the average volume. Hopefully, we’ll end up seeing a decline in suicide in the months following Mr. Williams’ tragic death.

Dr. Miller is a coauthor of “Shrink Rap: Three Psychiatrists Explain Their Work” (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2011).

National Suicide Prevention Day fell on Sept. 10 this year, surrounded by National Suicide Prevention Week Sept. 8-14. The conversation, as I’m sure everyone noticed, was focused on the suicide of actor Robin Williams. As we move out a few weeks, my patients – especially those who have contemplated ending their own lives – continue to talk about this tragic loss.

The fear is that the suicide of a celebrity will lead to an increase in the suicide rate in the general public – copycat suicides, if you will. In the month after Marilyn Monroe died of an overdose in 1962, the suicide rate rose by more than 10%. On the other hand, the death of a celebrity may lead to a decrease in the suicide rate, as happened after Kurt Cobain’s death from a self-inflicted gunshot wound in 1994. In the period after Cobain’s death, an effort was made to publicize resources for those who need help. The suicide rate dropped, while calls to hotlines rose.

After Robin Williams’ death, my own social media feeds were full of ads for the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline (NSPL), a hotline with the number 1-800-273-TALK. There are other hotlines, but this was the one I saw most. I wanted to learn about suicide hotlines, so I did a few things: I asked readers of our Shrink Rap blog to tell me about their experiences, and I called the hotline myself to see if I could learn about the structure of the organization, what resources they had to offer a distraught caller, and whether there had been a change in the number of calls they’d received in the time following Mr. Williams’ death.

I called from my cell phone, which is registered in Maryland, while sitting in my home in Baltimore City. The call was routed to Grassroots Crisis Intervention Center in Columbia, Md. Google Maps tells me the center is 25 miles from my house, and it would take me 32 minutes to drive there. In addition to being part of a network of 160 hotline centers across the country, Grassroots has a walk-in crisis center and a mobile treatment center, and is adjacent to a homeless shelter.

“Most of the people who call the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline are suicidal,” said Nicole DeChirico, director of crisis intervention services for Grassroots. “There is a gradation in suicidal thinking, but about 90% of our callers are considering it.”

“We first form rapport, and then we try to quickly assess if an attempt has already been made, and if they are in any danger. We use the assessment of suicidality that is put out by the NSPL. It’s a structured template that is used as a guideline.”

Ms. DeChirico noted that the people who man the hotlines have bachelor’s or master’s degrees – often in psychology, social work, counseling, or education. If feasible, a Safety Planning Intervention is implemented, based on the work of Barbara Stanley, Ph.D., at Columbia University in New York.

“We talk to people about what they need to do to feel safe. If they allow it, we set up a follow-up call. Of the total number of people who have attempted suicide once in the past and lived, 90%-96% never go on to attempt suicide again,” Ms. DeChirico noted. Suicide is a time-limited acute crisis.”

The Grassroots team can see patients on site while they wait for appointments with an outpatient clinician, and can send a mobile crisis team to those who need it if they are in the county served by the organization. I wondered if all 160 agencies that received calls from the NSPL could also provide crisis services.

Marcia Epstein, LMSW, was director of the Headquarters Counseling Center in Lawrence, Kan., from 1979 to 2013. The center became part of the first national suicide prevention hotline network, the National Hopeline Network, 1-800-SUICIDE, in 2001, and then became part of the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline, 1-800-274-TALK (8255), when that network began in January 2005.

“The types of programs and agencies which are part of NSPL vary greatly. The accreditation that allows them to be part of the NSPL network also varies. Some centers are staffed totally by licensed mental health therapists, while others might include trained volunteers and paid counselors who have no professional degree or licensure. Service may be delivered by phone, as well as in person, by text, and by live chat. In person might be on site or through mobile crisis outreach. Some centers are part of other organizations, while others are free-standing, and some serve entire states, while others serve geographically smaller regions,” Ms. Epstein explained in a series of e-mails. She noted that some centers assess and refer, while others, like Grassroots, are able to provide more counseling.

“So if it sounds like I’m saying there is little consistency between centers, yes, that is my experience. But the centers all bring strong commitment to preventing suicide.”

Ms. Epstein continued to discuss the power of the work done with hotline callers.

“The really helpful counseling comes from the heart, from connecting to people with caring and respect and patience, and using our skills in helping them stay safer through the crisis and then, when needed, to stay safer in the long run. It takes a lot of bravery from the people letting us help. And it takes a lot of creativity and flexibility in coming up together with realistic plans to support safety.”

I was curious about the patient response, and I found that was mixed. It was also notable that different patients found different forms of communication to be helpful.

A woman who identified herself only as “Virginia Woolf” wrote, “I have contacted the Samaritans on the [email protected] line because I could write to them via e-mail. I don’t like phones and I also know too many of the counselors on the local crisis line. Each time I was definitely close to suicide. I was in despair and I had the means at hand. I think what stopped me was knowing they would reply. They always did, within a few hours, but waiting for their reply kept me safe.”

Not every response was as positive.

One writer noted, “It was not a productive, supportive, or empathetic person. I felt like she was arrogant, judgmental, and didn’t really care about why I was calling.” The same writer, however, was able to find solace elsewhere. “I have texted CrisisChat and it was an excellent chat and I did feel better.”

Finally, Ms. DeChirico sent me information about the call volume from our local NPSL center in Columbia. From July 1, 2013, to July 31, 2014, the Lifeline received an average of 134 calls per month. December had the highest number of calls, with 163, while August had the lowest with 118. September, February, and April all had 120 calls or fewer.

Robin Williams died on Aug. 11, 2014, and the center received 200 calls in August – a 49% increase over the average volume. Hopefully, we’ll end up seeing a decline in suicide in the months following Mr. Williams’ tragic death.

Dr. Miller is a coauthor of “Shrink Rap: Three Psychiatrists Explain Their Work” (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2011).

National Suicide Prevention Day fell on Sept. 10 this year, surrounded by National Suicide Prevention Week Sept. 8-14. The conversation, as I’m sure everyone noticed, was focused on the suicide of actor Robin Williams. As we move out a few weeks, my patients – especially those who have contemplated ending their own lives – continue to talk about this tragic loss.

The fear is that the suicide of a celebrity will lead to an increase in the suicide rate in the general public – copycat suicides, if you will. In the month after Marilyn Monroe died of an overdose in 1962, the suicide rate rose by more than 10%. On the other hand, the death of a celebrity may lead to a decrease in the suicide rate, as happened after Kurt Cobain’s death from a self-inflicted gunshot wound in 1994. In the period after Cobain’s death, an effort was made to publicize resources for those who need help. The suicide rate dropped, while calls to hotlines rose.

After Robin Williams’ death, my own social media feeds were full of ads for the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline (NSPL), a hotline with the number 1-800-273-TALK. There are other hotlines, but this was the one I saw most. I wanted to learn about suicide hotlines, so I did a few things: I asked readers of our Shrink Rap blog to tell me about their experiences, and I called the hotline myself to see if I could learn about the structure of the organization, what resources they had to offer a distraught caller, and whether there had been a change in the number of calls they’d received in the time following Mr. Williams’ death.

I called from my cell phone, which is registered in Maryland, while sitting in my home in Baltimore City. The call was routed to Grassroots Crisis Intervention Center in Columbia, Md. Google Maps tells me the center is 25 miles from my house, and it would take me 32 minutes to drive there. In addition to being part of a network of 160 hotline centers across the country, Grassroots has a walk-in crisis center and a mobile treatment center, and is adjacent to a homeless shelter.

“Most of the people who call the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline are suicidal,” said Nicole DeChirico, director of crisis intervention services for Grassroots. “There is a gradation in suicidal thinking, but about 90% of our callers are considering it.”

“We first form rapport, and then we try to quickly assess if an attempt has already been made, and if they are in any danger. We use the assessment of suicidality that is put out by the NSPL. It’s a structured template that is used as a guideline.”

Ms. DeChirico noted that the people who man the hotlines have bachelor’s or master’s degrees – often in psychology, social work, counseling, or education. If feasible, a Safety Planning Intervention is implemented, based on the work of Barbara Stanley, Ph.D., at Columbia University in New York.

“We talk to people about what they need to do to feel safe. If they allow it, we set up a follow-up call. Of the total number of people who have attempted suicide once in the past and lived, 90%-96% never go on to attempt suicide again,” Ms. DeChirico noted. Suicide is a time-limited acute crisis.”

The Grassroots team can see patients on site while they wait for appointments with an outpatient clinician, and can send a mobile crisis team to those who need it if they are in the county served by the organization. I wondered if all 160 agencies that received calls from the NSPL could also provide crisis services.

Marcia Epstein, LMSW, was director of the Headquarters Counseling Center in Lawrence, Kan., from 1979 to 2013. The center became part of the first national suicide prevention hotline network, the National Hopeline Network, 1-800-SUICIDE, in 2001, and then became part of the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline, 1-800-274-TALK (8255), when that network began in January 2005.

“The types of programs and agencies which are part of NSPL vary greatly. The accreditation that allows them to be part of the NSPL network also varies. Some centers are staffed totally by licensed mental health therapists, while others might include trained volunteers and paid counselors who have no professional degree or licensure. Service may be delivered by phone, as well as in person, by text, and by live chat. In person might be on site or through mobile crisis outreach. Some centers are part of other organizations, while others are free-standing, and some serve entire states, while others serve geographically smaller regions,” Ms. Epstein explained in a series of e-mails. She noted that some centers assess and refer, while others, like Grassroots, are able to provide more counseling.

“So if it sounds like I’m saying there is little consistency between centers, yes, that is my experience. But the centers all bring strong commitment to preventing suicide.”

Ms. Epstein continued to discuss the power of the work done with hotline callers.

“The really helpful counseling comes from the heart, from connecting to people with caring and respect and patience, and using our skills in helping them stay safer through the crisis and then, when needed, to stay safer in the long run. It takes a lot of bravery from the people letting us help. And it takes a lot of creativity and flexibility in coming up together with realistic plans to support safety.”

I was curious about the patient response, and I found that was mixed. It was also notable that different patients found different forms of communication to be helpful.

A woman who identified herself only as “Virginia Woolf” wrote, “I have contacted the Samaritans on the [email protected] line because I could write to them via e-mail. I don’t like phones and I also know too many of the counselors on the local crisis line. Each time I was definitely close to suicide. I was in despair and I had the means at hand. I think what stopped me was knowing they would reply. They always did, within a few hours, but waiting for their reply kept me safe.”

Not every response was as positive.

One writer noted, “It was not a productive, supportive, or empathetic person. I felt like she was arrogant, judgmental, and didn’t really care about why I was calling.” The same writer, however, was able to find solace elsewhere. “I have texted CrisisChat and it was an excellent chat and I did feel better.”

Finally, Ms. DeChirico sent me information about the call volume from our local NPSL center in Columbia. From July 1, 2013, to July 31, 2014, the Lifeline received an average of 134 calls per month. December had the highest number of calls, with 163, while August had the lowest with 118. September, February, and April all had 120 calls or fewer.

Robin Williams died on Aug. 11, 2014, and the center received 200 calls in August – a 49% increase over the average volume. Hopefully, we’ll end up seeing a decline in suicide in the months following Mr. Williams’ tragic death.

Dr. Miller is a coauthor of “Shrink Rap: Three Psychiatrists Explain Their Work” (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2011).

Psychiatry, free speech, school safety, and cannibalism

Over the past few days, an article has circulated about a 23-year-old middle school teacher in Cambridge, Md., who was suspended from his job because of two futuristic novels he wrote, including one about a school massacre 900 years in the future. The story was reported in The Atlantic under the headline, "In Maryland, a Soviet-Style Punishment for a Novelist."

The article, by Jeffrey Goldberg, said the young teacher had self-published his novels some time ago under a pseudonym. In addition to his being suspended, an "emergency medical evaluation" was ordered, his house was searched, and the school was swept for bombs by K-9 dogs. No charges have been filed as of this writing.

This response was deemed an "overreaction," and certainly has been good for book sales but probably not so much for the young man’s teaching career. The idea that artistic expression must conform to a specific standard or jeopardize one’s job leaves those with creative pursuits to worry and civil rights advocates to protest.

Soon after, the Los Angeles Times published an article stating that the issue was not the novels – the school knew about those in 2012 – but rather the content of a four-page letter the teacher had written to the school board suggesting that the teacher was suffering from some type of psychiatric condition and might have included indications that he was suicidal or dangerous. With this information, it was not as clear if the police response was an overreaction, and such determinations are generally made in hindsight: If a bomb is found, the decision was heroic, if not, it was an overreaction and a civil rights violation.

The case reminded me of the story about a New York City police officer who had Internet discussions about his desire to cook and eat women, including his ex-wife. While the officer never ate anyone, he was part of an online community called the Dark Fetish Network, which has of tens of thousands of registered users who discuss violent sexual fantasies. The officer, known in the media frenzy as Cannibal Cop, lost his job and was convicted of plotting to kidnap, a crime that could carry a life sentence. He reportedly had graphic discussions of plans to kill, roast, and eat specified victims, and he claimed that he had the means to do so. An investigation revealed that he did not own the implements that would enable him to carry out such a plan. His lawyer insisted that he was engaged in a role-playing fantasy, but he was convicted by a jury in 2012. In July, his conviction was overturned and he was released on bond. By that time, Cannibal Cop had served a year and a half in prison, with several months of it in solitary confinement.

Situations in which a person has done nothing illegal but has spoken or written words that indicate he or she might be a threat to public safety are fraught with concerns. While violent fantasies might be seen as "creepy" at a minimum, the criminal justice system is left to decide where the line is between fantasy and plan, and when a real threat exists. A person has the right to his dark fantasies, and the First Amendment right to free speech allows for discussion of those fantasies, while artistic endeavors allow for their expression. At the same time, if there are named or presumed victims, those individuals should not have to live with the terror of wondering if the fantasizer is going to act on the fantasies.

Invariably, psychiatrists end up being involved, even if the individual in question has no psychiatric history or obvious diagnosis. In a New York magazine article about the police officer titled, "A Dangerous Mind," Robert Kolker noted: "Pre-crime and psychiatry often go hand in hand. Legal instruments like institutionalization and sex-offender registration all share the goal of preventing crime from taking place, and for better or worse, they’re based on a psychiatric rationale."

As we all know, it can be difficult – if not impossible – to distinguish those who are having fantasies from those who are planning to commit a dangerous act. As psychiatrists, we deal with this uncertainty for patients who have suicidal thoughts on a regular basis. Often, even the patients don’t know for sure if they will act on their impulses. Fantasies that involve harming others are more unusual in clinical practice, and our risk assessment often begins with the stated intent of the individual. Our strongest predictor of future behavior continues to be past behavior, and neither the teacher nor the police officer in the stories above had criminal records.

To make it even more confusing, the Internet has added to the uncertainty; people have always had dangerous and fetishistic fantasies, but now there are ways others can learn the content of what was once very private. The risk, of course, is that fantasies and artistic endeavors become subject to both psychiatric scrutiny and criminal prosecution in a way that threatens civil rights and squelches creativity.

Dr. Miller is a coauthor of "Shrink Rap: Three Psychiatrists Explain Their Work" (Baltimore:The Johns Hopkins University Press, 2011).

Over the past few days, an article has circulated about a 23-year-old middle school teacher in Cambridge, Md., who was suspended from his job because of two futuristic novels he wrote, including one about a school massacre 900 years in the future. The story was reported in The Atlantic under the headline, "In Maryland, a Soviet-Style Punishment for a Novelist."

The article, by Jeffrey Goldberg, said the young teacher had self-published his novels some time ago under a pseudonym. In addition to his being suspended, an "emergency medical evaluation" was ordered, his house was searched, and the school was swept for bombs by K-9 dogs. No charges have been filed as of this writing.

This response was deemed an "overreaction," and certainly has been good for book sales but probably not so much for the young man’s teaching career. The idea that artistic expression must conform to a specific standard or jeopardize one’s job leaves those with creative pursuits to worry and civil rights advocates to protest.

Soon after, the Los Angeles Times published an article stating that the issue was not the novels – the school knew about those in 2012 – but rather the content of a four-page letter the teacher had written to the school board suggesting that the teacher was suffering from some type of psychiatric condition and might have included indications that he was suicidal or dangerous. With this information, it was not as clear if the police response was an overreaction, and such determinations are generally made in hindsight: If a bomb is found, the decision was heroic, if not, it was an overreaction and a civil rights violation.

The case reminded me of the story about a New York City police officer who had Internet discussions about his desire to cook and eat women, including his ex-wife. While the officer never ate anyone, he was part of an online community called the Dark Fetish Network, which has of tens of thousands of registered users who discuss violent sexual fantasies. The officer, known in the media frenzy as Cannibal Cop, lost his job and was convicted of plotting to kidnap, a crime that could carry a life sentence. He reportedly had graphic discussions of plans to kill, roast, and eat specified victims, and he claimed that he had the means to do so. An investigation revealed that he did not own the implements that would enable him to carry out such a plan. His lawyer insisted that he was engaged in a role-playing fantasy, but he was convicted by a jury in 2012. In July, his conviction was overturned and he was released on bond. By that time, Cannibal Cop had served a year and a half in prison, with several months of it in solitary confinement.

Situations in which a person has done nothing illegal but has spoken or written words that indicate he or she might be a threat to public safety are fraught with concerns. While violent fantasies might be seen as "creepy" at a minimum, the criminal justice system is left to decide where the line is between fantasy and plan, and when a real threat exists. A person has the right to his dark fantasies, and the First Amendment right to free speech allows for discussion of those fantasies, while artistic endeavors allow for their expression. At the same time, if there are named or presumed victims, those individuals should not have to live with the terror of wondering if the fantasizer is going to act on the fantasies.

Invariably, psychiatrists end up being involved, even if the individual in question has no psychiatric history or obvious diagnosis. In a New York magazine article about the police officer titled, "A Dangerous Mind," Robert Kolker noted: "Pre-crime and psychiatry often go hand in hand. Legal instruments like institutionalization and sex-offender registration all share the goal of preventing crime from taking place, and for better or worse, they’re based on a psychiatric rationale."

As we all know, it can be difficult – if not impossible – to distinguish those who are having fantasies from those who are planning to commit a dangerous act. As psychiatrists, we deal with this uncertainty for patients who have suicidal thoughts on a regular basis. Often, even the patients don’t know for sure if they will act on their impulses. Fantasies that involve harming others are more unusual in clinical practice, and our risk assessment often begins with the stated intent of the individual. Our strongest predictor of future behavior continues to be past behavior, and neither the teacher nor the police officer in the stories above had criminal records.

To make it even more confusing, the Internet has added to the uncertainty; people have always had dangerous and fetishistic fantasies, but now there are ways others can learn the content of what was once very private. The risk, of course, is that fantasies and artistic endeavors become subject to both psychiatric scrutiny and criminal prosecution in a way that threatens civil rights and squelches creativity.

Dr. Miller is a coauthor of "Shrink Rap: Three Psychiatrists Explain Their Work" (Baltimore:The Johns Hopkins University Press, 2011).

Over the past few days, an article has circulated about a 23-year-old middle school teacher in Cambridge, Md., who was suspended from his job because of two futuristic novels he wrote, including one about a school massacre 900 years in the future. The story was reported in The Atlantic under the headline, "In Maryland, a Soviet-Style Punishment for a Novelist."

The article, by Jeffrey Goldberg, said the young teacher had self-published his novels some time ago under a pseudonym. In addition to his being suspended, an "emergency medical evaluation" was ordered, his house was searched, and the school was swept for bombs by K-9 dogs. No charges have been filed as of this writing.

This response was deemed an "overreaction," and certainly has been good for book sales but probably not so much for the young man’s teaching career. The idea that artistic expression must conform to a specific standard or jeopardize one’s job leaves those with creative pursuits to worry and civil rights advocates to protest.

Soon after, the Los Angeles Times published an article stating that the issue was not the novels – the school knew about those in 2012 – but rather the content of a four-page letter the teacher had written to the school board suggesting that the teacher was suffering from some type of psychiatric condition and might have included indications that he was suicidal or dangerous. With this information, it was not as clear if the police response was an overreaction, and such determinations are generally made in hindsight: If a bomb is found, the decision was heroic, if not, it was an overreaction and a civil rights violation.

The case reminded me of the story about a New York City police officer who had Internet discussions about his desire to cook and eat women, including his ex-wife. While the officer never ate anyone, he was part of an online community called the Dark Fetish Network, which has of tens of thousands of registered users who discuss violent sexual fantasies. The officer, known in the media frenzy as Cannibal Cop, lost his job and was convicted of plotting to kidnap, a crime that could carry a life sentence. He reportedly had graphic discussions of plans to kill, roast, and eat specified victims, and he claimed that he had the means to do so. An investigation revealed that he did not own the implements that would enable him to carry out such a plan. His lawyer insisted that he was engaged in a role-playing fantasy, but he was convicted by a jury in 2012. In July, his conviction was overturned and he was released on bond. By that time, Cannibal Cop had served a year and a half in prison, with several months of it in solitary confinement.

Situations in which a person has done nothing illegal but has spoken or written words that indicate he or she might be a threat to public safety are fraught with concerns. While violent fantasies might be seen as "creepy" at a minimum, the criminal justice system is left to decide where the line is between fantasy and plan, and when a real threat exists. A person has the right to his dark fantasies, and the First Amendment right to free speech allows for discussion of those fantasies, while artistic endeavors allow for their expression. At the same time, if there are named or presumed victims, those individuals should not have to live with the terror of wondering if the fantasizer is going to act on the fantasies.

Invariably, psychiatrists end up being involved, even if the individual in question has no psychiatric history or obvious diagnosis. In a New York magazine article about the police officer titled, "A Dangerous Mind," Robert Kolker noted: "Pre-crime and psychiatry often go hand in hand. Legal instruments like institutionalization and sex-offender registration all share the goal of preventing crime from taking place, and for better or worse, they’re based on a psychiatric rationale."

As we all know, it can be difficult – if not impossible – to distinguish those who are having fantasies from those who are planning to commit a dangerous act. As psychiatrists, we deal with this uncertainty for patients who have suicidal thoughts on a regular basis. Often, even the patients don’t know for sure if they will act on their impulses. Fantasies that involve harming others are more unusual in clinical practice, and our risk assessment often begins with the stated intent of the individual. Our strongest predictor of future behavior continues to be past behavior, and neither the teacher nor the police officer in the stories above had criminal records.

To make it even more confusing, the Internet has added to the uncertainty; people have always had dangerous and fetishistic fantasies, but now there are ways others can learn the content of what was once very private. The risk, of course, is that fantasies and artistic endeavors become subject to both psychiatric scrutiny and criminal prosecution in a way that threatens civil rights and squelches creativity.

Dr. Miller is a coauthor of "Shrink Rap: Three Psychiatrists Explain Their Work" (Baltimore:The Johns Hopkins University Press, 2011).

Robin Williams’s suspected suicide could encourage others to get help

The news last night was tragic: Robin Williams has died of an apparent suicide at the early age of 63. I saw the news and felt overwhelmingly sad. Really? He was a tremendous actor, a creative genius by any account, a man who I imagined had everything – talent, wealth, fame, the wonderful ability to make people laugh and to brighten lives. Such people also get draped with love and admiration, though certainly at a price. For what it’s worth, Robin Williams has been open about the fact that he’s struggled with both depression and addiction, but the complete story is never the one that gets told by the media.

Twitter started with 140-character links to suicide hotlines and suicide awareness, to statements about how depression is a treatable illness – Is it always? – and I hit retweet on a comment stating:" We’re never going to get anywhere till we take seriously that depression is an illness, not a weakness" and several people retweeted my retweet. I’m not sure why I did this; I don’t think that most people still think of mood disorders as a "weakness," or that those who do might change their minds because of a tweet. And I don’t think that suicide does anything to reduce stigma.

One psychiatrist friend tweeted a comment about how one should never ask someone why they are depressed, I guess because the "why?" implies something other than because biology dictated it, but if you’ve ever spoken to a person suffering from depression, you know that it comes in all shades of severity and that people often write a story to explain it. Sometimes that story is right: I’m depressed because of a breakup, or because I don’t have a job now, or because of ongoing work stress – and indeed, the person suffering often feels better after talking about the situation, after getting a new boyfriend or a new job, or after their boss moves to Zimbabwe.

I’m convinced that treatment works best when psychotherapy is combined with medication (if indicated), and while medicines are a miracle for some, they aren’t for others. As psychiatrists, we certainly see a good deal of treatment-resistant depression. And yes, the antipsychiatry faction may postulate that it is the treatment – the medications, specifically – that cause people to kill themselves and others, but I will leave you with the idea that the science just doesn’t support that. Certainly, they aren’t for everyone, but clinically, I have seen medications do more good than harm in clinical practice overall.

I know nothing about Robin Williams beyond what I’ve read in the media, and I know that the media reports are often incomplete and distorted. I do imagine that Mr. Williams had the resources to get good care and that he may well have had treatment for depression since he was open about his struggle. His story will be used to say: "Get help," and if you’re feeling suicidal and aren’t getting help, please do so. If you’re feeling suicidal and "help" isn’t making you feel better, please consider getting a second opinion or a different kind of help.

The tragic thing about suicide is that it’s a permanent answer to what is often a temporary problem.

Sometimes, I imagine that there are people who have tried and tried to get help and that their pain remains so unbearable for so long that suicide offers them the only possible relief – if such a thing is even to be had given that we don’t what comes next and some religions will say that suicide leads to nowhere good. Even if it provides relief to the person involved, it comes with the cost of leaving those who remain in horrible pain. Sadly, depressed people sometimes imagine that the world will be better off without them, and often that idea is just not true.

I hope that Robin Williams is in a better place, for his sake. I hope that before he ended his life, he tried every possible treatment option, and that this wasn’t an impulsive decision, or one based on an episodic relapse of either depression or substance abuse – a relapse that may have resolved and let him live for decades more. I hope his wife and children and all the people who knew and loved him will eventually find some peace. His death, however, is not simply a personal one because he touched us all with his talent and his charisma. What a tragic loss.

Dr. Miller also posted a version http://bit.ly/1kyO1a7 of this piece on the Shrink Rap News website. She is a coauthor of "Shrink Rap: Three Psychiatrists Explain Their Work" (Baltimore: the Johns Hopkins University Press, 2011).

The news last night was tragic: Robin Williams has died of an apparent suicide at the early age of 63. I saw the news and felt overwhelmingly sad. Really? He was a tremendous actor, a creative genius by any account, a man who I imagined had everything – talent, wealth, fame, the wonderful ability to make people laugh and to brighten lives. Such people also get draped with love and admiration, though certainly at a price. For what it’s worth, Robin Williams has been open about the fact that he’s struggled with both depression and addiction, but the complete story is never the one that gets told by the media.

Twitter started with 140-character links to suicide hotlines and suicide awareness, to statements about how depression is a treatable illness – Is it always? – and I hit retweet on a comment stating:" We’re never going to get anywhere till we take seriously that depression is an illness, not a weakness" and several people retweeted my retweet. I’m not sure why I did this; I don’t think that most people still think of mood disorders as a "weakness," or that those who do might change their minds because of a tweet. And I don’t think that suicide does anything to reduce stigma.

One psychiatrist friend tweeted a comment about how one should never ask someone why they are depressed, I guess because the "why?" implies something other than because biology dictated it, but if you’ve ever spoken to a person suffering from depression, you know that it comes in all shades of severity and that people often write a story to explain it. Sometimes that story is right: I’m depressed because of a breakup, or because I don’t have a job now, or because of ongoing work stress – and indeed, the person suffering often feels better after talking about the situation, after getting a new boyfriend or a new job, or after their boss moves to Zimbabwe.

I’m convinced that treatment works best when psychotherapy is combined with medication (if indicated), and while medicines are a miracle for some, they aren’t for others. As psychiatrists, we certainly see a good deal of treatment-resistant depression. And yes, the antipsychiatry faction may postulate that it is the treatment – the medications, specifically – that cause people to kill themselves and others, but I will leave you with the idea that the science just doesn’t support that. Certainly, they aren’t for everyone, but clinically, I have seen medications do more good than harm in clinical practice overall.

I know nothing about Robin Williams beyond what I’ve read in the media, and I know that the media reports are often incomplete and distorted. I do imagine that Mr. Williams had the resources to get good care and that he may well have had treatment for depression since he was open about his struggle. His story will be used to say: "Get help," and if you’re feeling suicidal and aren’t getting help, please do so. If you’re feeling suicidal and "help" isn’t making you feel better, please consider getting a second opinion or a different kind of help.

The tragic thing about suicide is that it’s a permanent answer to what is often a temporary problem.

Sometimes, I imagine that there are people who have tried and tried to get help and that their pain remains so unbearable for so long that suicide offers them the only possible relief – if such a thing is even to be had given that we don’t what comes next and some religions will say that suicide leads to nowhere good. Even if it provides relief to the person involved, it comes with the cost of leaving those who remain in horrible pain. Sadly, depressed people sometimes imagine that the world will be better off without them, and often that idea is just not true.

I hope that Robin Williams is in a better place, for his sake. I hope that before he ended his life, he tried every possible treatment option, and that this wasn’t an impulsive decision, or one based on an episodic relapse of either depression or substance abuse – a relapse that may have resolved and let him live for decades more. I hope his wife and children and all the people who knew and loved him will eventually find some peace. His death, however, is not simply a personal one because he touched us all with his talent and his charisma. What a tragic loss.

Dr. Miller also posted a version http://bit.ly/1kyO1a7 of this piece on the Shrink Rap News website. She is a coauthor of "Shrink Rap: Three Psychiatrists Explain Their Work" (Baltimore: the Johns Hopkins University Press, 2011).

The news last night was tragic: Robin Williams has died of an apparent suicide at the early age of 63. I saw the news and felt overwhelmingly sad. Really? He was a tremendous actor, a creative genius by any account, a man who I imagined had everything – talent, wealth, fame, the wonderful ability to make people laugh and to brighten lives. Such people also get draped with love and admiration, though certainly at a price. For what it’s worth, Robin Williams has been open about the fact that he’s struggled with both depression and addiction, but the complete story is never the one that gets told by the media.

Twitter started with 140-character links to suicide hotlines and suicide awareness, to statements about how depression is a treatable illness – Is it always? – and I hit retweet on a comment stating:" We’re never going to get anywhere till we take seriously that depression is an illness, not a weakness" and several people retweeted my retweet. I’m not sure why I did this; I don’t think that most people still think of mood disorders as a "weakness," or that those who do might change their minds because of a tweet. And I don’t think that suicide does anything to reduce stigma.

One psychiatrist friend tweeted a comment about how one should never ask someone why they are depressed, I guess because the "why?" implies something other than because biology dictated it, but if you’ve ever spoken to a person suffering from depression, you know that it comes in all shades of severity and that people often write a story to explain it. Sometimes that story is right: I’m depressed because of a breakup, or because I don’t have a job now, or because of ongoing work stress – and indeed, the person suffering often feels better after talking about the situation, after getting a new boyfriend or a new job, or after their boss moves to Zimbabwe.

I’m convinced that treatment works best when psychotherapy is combined with medication (if indicated), and while medicines are a miracle for some, they aren’t for others. As psychiatrists, we certainly see a good deal of treatment-resistant depression. And yes, the antipsychiatry faction may postulate that it is the treatment – the medications, specifically – that cause people to kill themselves and others, but I will leave you with the idea that the science just doesn’t support that. Certainly, they aren’t for everyone, but clinically, I have seen medications do more good than harm in clinical practice overall.

I know nothing about Robin Williams beyond what I’ve read in the media, and I know that the media reports are often incomplete and distorted. I do imagine that Mr. Williams had the resources to get good care and that he may well have had treatment for depression since he was open about his struggle. His story will be used to say: "Get help," and if you’re feeling suicidal and aren’t getting help, please do so. If you’re feeling suicidal and "help" isn’t making you feel better, please consider getting a second opinion or a different kind of help.

The tragic thing about suicide is that it’s a permanent answer to what is often a temporary problem.

Sometimes, I imagine that there are people who have tried and tried to get help and that their pain remains so unbearable for so long that suicide offers them the only possible relief – if such a thing is even to be had given that we don’t what comes next and some religions will say that suicide leads to nowhere good. Even if it provides relief to the person involved, it comes with the cost of leaving those who remain in horrible pain. Sadly, depressed people sometimes imagine that the world will be better off without them, and often that idea is just not true.

I hope that Robin Williams is in a better place, for his sake. I hope that before he ended his life, he tried every possible treatment option, and that this wasn’t an impulsive decision, or one based on an episodic relapse of either depression or substance abuse – a relapse that may have resolved and let him live for decades more. I hope his wife and children and all the people who knew and loved him will eventually find some peace. His death, however, is not simply a personal one because he touched us all with his talent and his charisma. What a tragic loss.

Dr. Miller also posted a version http://bit.ly/1kyO1a7 of this piece on the Shrink Rap News website. She is a coauthor of "Shrink Rap: Three Psychiatrists Explain Their Work" (Baltimore: the Johns Hopkins University Press, 2011).

The stigma of being a shrink

A Clinical Psychiatry News reader wrote in recently to object to the use of the term "shrink" in our column name. The writer noted, "We spend a lot of time trying to destigmatize the field, then use terms like this among ourselves. It’s odd and offensive." The feedback made me pause and wonder to myself if the term "shrink" is, in fact, stigmatizing.

Let me first give a little history of the decision to name our column "Shrink Rap News." In 2006, I was sitting at the kitchen table and decided I wanted a blog. I didn’t know what a blog actually was, but I wanted one. I went to blogger.com to set up a free website and was asked what I’d like to call my blog. On an impulse, I titled it "Shrink Rap." There was no debate or consideration, and no consultation. I liked the play on words with "shrink wrap," which is used for food storage, and I liked the connotation of psychiatrists talking, or "rapping." In a matter of hours, my impulsive thought was turned into the Shrink Rap blog.

Over the next few days, I invited Dr. Steve Daviss and Dr. Annette Hanson to join me in this venture, and Shrink Rap has continued to publish regular blog posts for 8.5 years now. Steve initially balked at the use of "shrink," but when he went to start our podcast, he titled it "My Three Shrinks" and modified the logo from an old television show, "My Three Sons." When we went to title our book, I wanted to call it "Off the Couch," but I was told that there was no room for couches anywhere. After many months of lively debate, we ended up in a restaurant with our editor and a whiteboard, and by the end of the evening we were back at Shrink Rap for a title for the book.

When Clinical Psychiatry News and Psychology Today approached us to write for their sites, we decided to remain with an image that was working for us, and used Shrink Rap News and Shrink Rap Today for column titles. Because the term may imply something less than a serious look at psychiatric issues, the umbrella name for all our endeavors is The Accessible Psychiatry Project.

So, is the term "shrink" actually stigmatizing? When I think of words as being part of stigma, I think of racial and religious slurs, and those induce a visceral response of disgust in me. For whatever reason, I personally don’t have a clear negative association to the term "shrink" or even "headshrinker." To me, it evokes something lighthearted and includes having a sense of humor about the field. I imagine if psychiatrists ever had actually shrunken heads, I might feel differently. Others may well have another response to the term, but the emotional link to something negative is just not there for me.

From a site called World Wide Words – Investigating the English Language Across the Globe, which is devoted to linguistics and run by a British etymologist, I found the following history of the term "headshrinker":

The original meaning of the term head-shrinker was in reference to a member of a group in Amazonia, the Jivaro, who preserved the heads of their enemies by stripping the skin from the skull, which resulted in a shrunken mummified remnant the size of a fist. The term isn’t that old – it’s first recorded from 1926.

All the early evidence suggests that the person who invented the psychiatrist sense worked in the movies (no jokes please). We have to assume that the term came about because people regarded the process of psychiatry as being like head-shrinking because it reduced the size of the swollen egos so common in show business. Or perhaps they were suspicious about what psychiatrists actually did to their heads and how they did it and so made a joke to relieve the tension.

The earliest example we have is from an article in Time in November 1950 to which an editor has helpfully added a footnote to say that head-shrinker was Hollywood jargon for a psychiatrist. The term afterward became moderately popular, in part because it was used in the film Rebel Without a Cause in 1955. Robert Heinlein felt his readers needed it to be explained when he introduced it in "Time for the Stars" in 1956: " ‘Dr. Devereaux is the boss head-shrinker.’ I looked puzzled and Uncle Steve went on, ‘You don’t savvy? Psychiatrist.’ " By the time it turns up in West Side Story on Broadway in 1957, it was becoming established.

Shrink, the abbreviation, became popular in the United States in the 1970s, though it had first appeared in one of Thomas Pynchon’s books, "The Crying of Lot 49," in 1965, and there is anecdotal evidence that it was around earlier, which is only to be expected of a slang term that would have been mainly transmitted through the spoken word in its earliest days.

The issue of stigma in mental health has gotten a lot of attention as being one reason that people who have difficulties may not seek help. Certainly, words can be powerful, but I wonder if the term "shrink" might actually be easier for patients to use? "I’m going to see my shrink," might imply a visit with any number of mental health professionals and might disassociate it from the implication that the patient is going to see a psychiatrist for treatment of a mental illness, a condition that the media is all too happy to tell us causes people to commit mass murders.

"Shrink" may have a disparaging tone to it, or it may have a ring of affection, depending on the context. Certainly, there are many negative associations and jokes related to being an attorney, and one friend told me that his son was "going to the dark side" when the son applied to law school. Still, there is no stigma associated with having an appointment with one’s lawyer, leading me to believe that a profession can be stigmatized without stigmatizing the clientele.

Some words have taken on a pervasively negative meaning; others are harder to capture. After 8 years, Shrink Rap is now a platform for our writing, invested with its own meanings to us and our readers. The psychiatrist who wrote in to say it is offensive, odd, and stigmatizing certainly has a different set of associations to the word then we do, or we would never have let this be a title for our work.

Dr. Miller is a coauthor of "Shrink Rap: Three Psychiatrists Explain Their Work" (Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 2011).

A Clinical Psychiatry News reader wrote in recently to object to the use of the term "shrink" in our column name. The writer noted, "We spend a lot of time trying to destigmatize the field, then use terms like this among ourselves. It’s odd and offensive." The feedback made me pause and wonder to myself if the term "shrink" is, in fact, stigmatizing.

Let me first give a little history of the decision to name our column "Shrink Rap News." In 2006, I was sitting at the kitchen table and decided I wanted a blog. I didn’t know what a blog actually was, but I wanted one. I went to blogger.com to set up a free website and was asked what I’d like to call my blog. On an impulse, I titled it "Shrink Rap." There was no debate or consideration, and no consultation. I liked the play on words with "shrink wrap," which is used for food storage, and I liked the connotation of psychiatrists talking, or "rapping." In a matter of hours, my impulsive thought was turned into the Shrink Rap blog.

Over the next few days, I invited Dr. Steve Daviss and Dr. Annette Hanson to join me in this venture, and Shrink Rap has continued to publish regular blog posts for 8.5 years now. Steve initially balked at the use of "shrink," but when he went to start our podcast, he titled it "My Three Shrinks" and modified the logo from an old television show, "My Three Sons." When we went to title our book, I wanted to call it "Off the Couch," but I was told that there was no room for couches anywhere. After many months of lively debate, we ended up in a restaurant with our editor and a whiteboard, and by the end of the evening we were back at Shrink Rap for a title for the book.

When Clinical Psychiatry News and Psychology Today approached us to write for their sites, we decided to remain with an image that was working for us, and used Shrink Rap News and Shrink Rap Today for column titles. Because the term may imply something less than a serious look at psychiatric issues, the umbrella name for all our endeavors is The Accessible Psychiatry Project.