User login

Patient-reported outcomes in esophageal diseases

In my introductory comments to the practice management section last year, I wrote about cultivating competencies for value-based care. One of the key competencies was patient centeredness. Patient-reported outcomes (PROs) and patient experience measures specifically were highlighted as examples of meaningful tools for achieving patient centeredness. Starting with this month’s contribution by Drs Reed and Dellon on PROs in esophageal disease, we begin a series of articles focused on this important construct. We will follow this article with reports focused on PRO for patients with irritable bowel syndrome, inflammatory bowel disease, and chronic liver disease. These reports will not only review the importance of PROs, but also highlight the most practical approaches to measuring disease-specific PROs in clinical practice all with the goal of improving the care of our patients.

Ziad Gellad, MD, MPH, AGAF, Special Section Editor

Patients seek medical care for symptoms affecting their quality of life,1 and this is particularly true of digestive diseases, in which many common conditions are symptom predominant. However, clinician and patient perception of symptoms often conflict,2 and formalized measurement tools may have a role for optimizing symptom assessment. Patient-reported outcomes (PROs) directly capture patients’ health status from their own perspectives and can bridge the divide between patient and provider interpretation. The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) defines PROs as “any report of the status of a patient’s health condition that comes directly from the patient without interpretation of the patient’s response by a clinician or anyone else.”3

For the clinical assessment of esophageal diseases, existing physiologic and structural testing modalities cannot ascertain patient disease perception or measure the impact of symptoms on health care–associated quality of life. In contrast, by capturing patient-centric data, PROs can provide insight into the psychosocial aspects of patient disease perceptions; capture health-related quality of life (HRQL); improve provider understanding; highlight discordance between physiologic, symptom, and HRQL measures; and formalize follow-up evaluation of treatment response.1,4 Following up symptoms such as dysphagia or heartburn over time in a structured way allows clinically obtained data to be used in pragmatic or comparative effectiveness studies. PROs are now an integral part of the FDA’s drug approval process.

In this article, we review the available PROs capturing esophageal symptoms with a focus on dysphagia and heartburn measures that were developed with rigorous methodology; it is beyond the scope of this article to perform a thorough review of all upper gastrointestinal (GI) PROs or quality-of-life PROs. We then discuss how esophageal PROs may be incorporated into clinical practice now, as well as opportunities for PRO use in the future.

Esophageal symptom-specific patient-reported outcomes

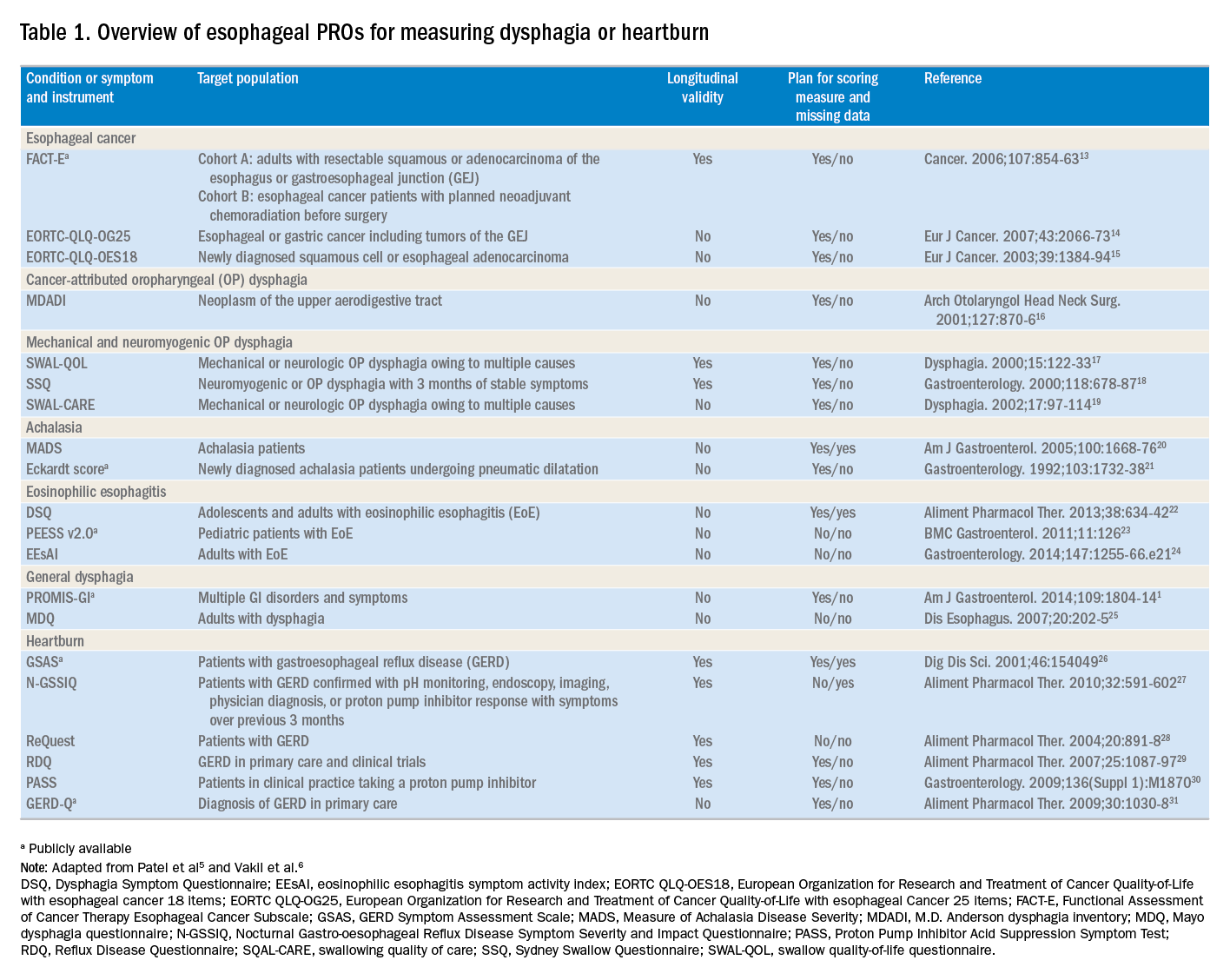

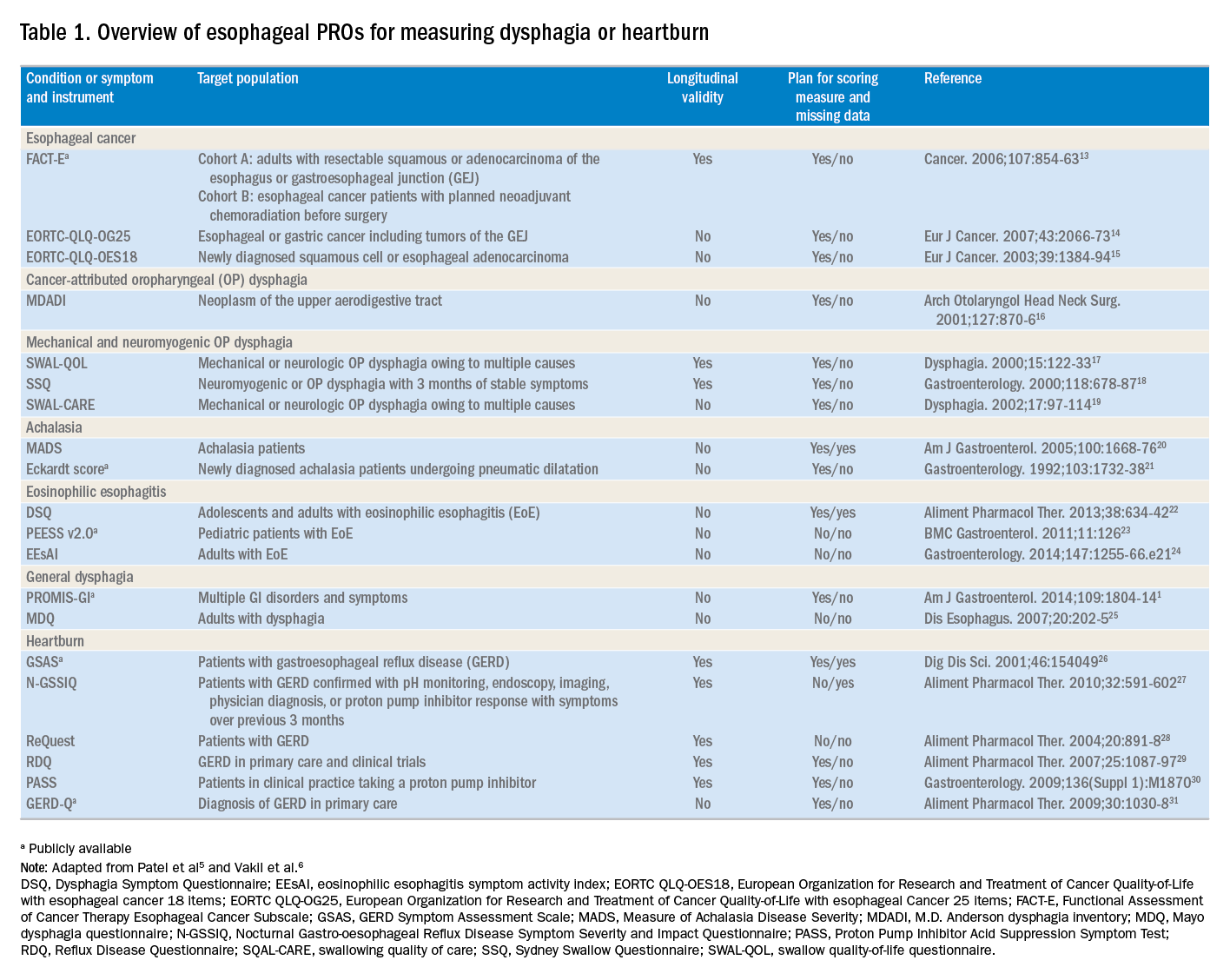

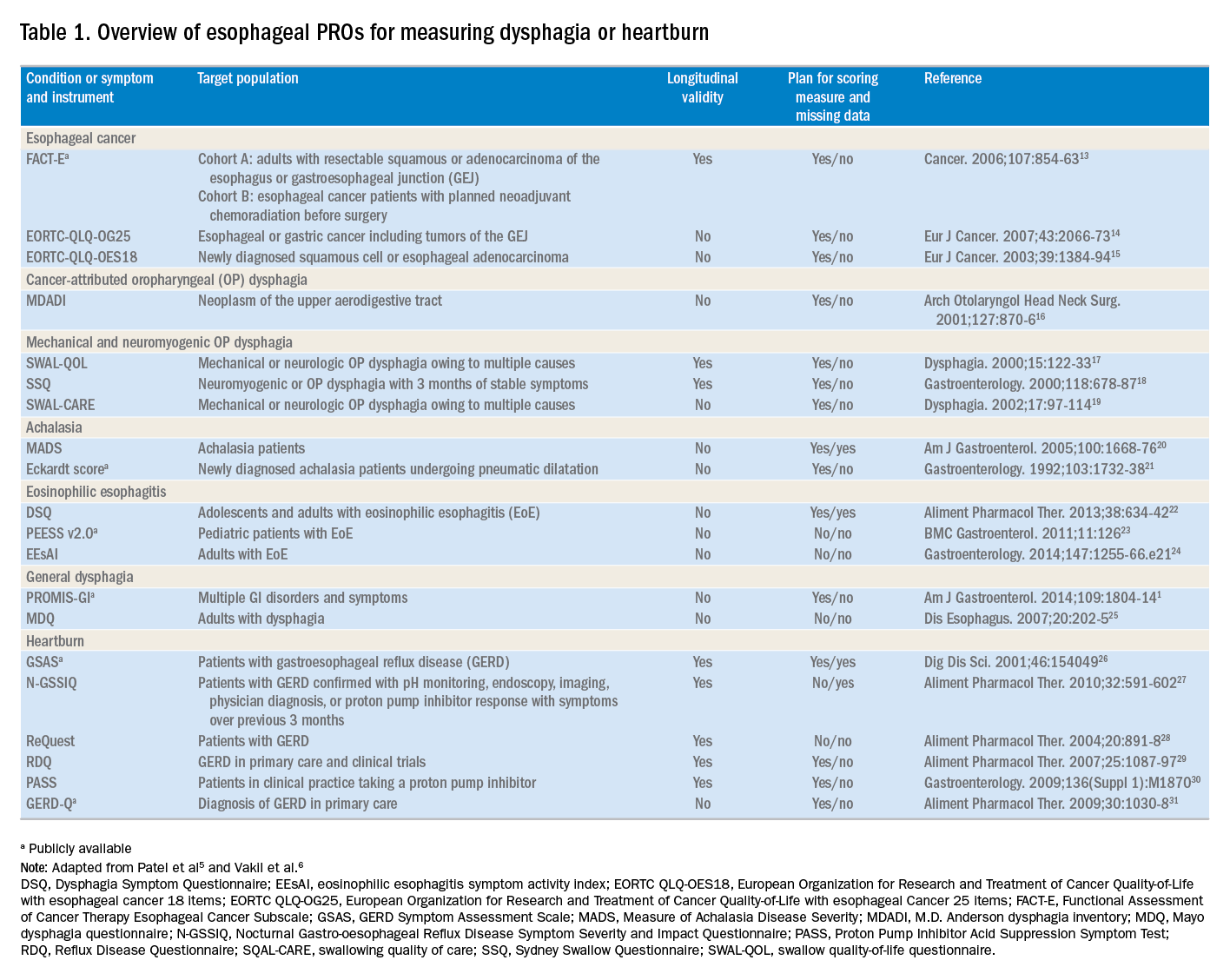

The literature pertinent to upper GI and esophageal-specific PROs is heterogeneous, and the development of PROs has been variable in rigor. Two recent systematic reviews identified PROs pertinent to dysphagia and heartburn (Table 1) and both emphasized rigorous measures developed in accordance with FDA guidance.3

Patel et al5 identified 34 dysphagia-specific PRO measures, of which 10 were rigorously developed (Table 1). These measures encompassed multiple conditions including esophageal cancer (Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy Esophageal Cancer Subscale, European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality-of-Life with esophageal Cancer 25 items, European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality-of-Life with esophageal cancer 18 items, upper aerodigestive neoplasm-attributable oropharyngeal dysphagia [M.D. Anderson dysphagia inventory], mechanical and neuromyogenic oropharyngeal dysphagia [swallow quality-of-life questionnaire], Sydney Swallow Questionnaire, [swallowing quality of care], achalasia [Measure of Achalasia Disease Severity], eosinophilic esophagitis [Dysphagia Symptom Questionnaire], and general dysphagia symptoms and gastroesophageal reflux [Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System Gastrointestinal Symptom Scales (PROMIS-GI)]. PROMIS-GI, produced as part of the National Institutes of Health PROMIS program, includes rigorous measures for general dysphagia symptoms and gastroesophageal reflux in addition to lower gastrointestinal symptom measures.

The systematic review by Vakil et al6 found 15 PRO measures for gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) symptoms that underwent psychometric evaluation (Table 1). Of these, 5 measures were devised according to the developmental steps stipulated by the US FDA and the European Medicines Agency, and each measure has been used as an end point for a clinical trial. The 5 measures include the GERD Symptom Assessment Scale, the Nocturnal Gastro-oesophageal Reflux Disease Symptom Severity and Impact Questionnaire, the Reflux Questionnaire, the Reflux Disease Questionnaire, and the Proton Pump Inhibitor Acid Suppression Symptom Test (Table 1). Additional PROs capturing esophageal symptoms include the eosinophilic esophagitis symptom activity index, Eckardt score (used for achalasia), Mayo dysphagia questionnaire, and GERD-Q (Table 1).

Utilization of esophageal patient-reported outcomes in practice

Before incorporating a PRO into clinical practice, providers must appreciate the construct(s), intent, developmental measurement properties, validation strategies, and responsiveness characteristics associated with the measure.4 PROs can be symptom- and/or condition-specific. For example, this could include dysphagia associated with achalasia or eosinophilic esophagitis, postoperative dysphagia from spine surgery, or general dysphagia symptoms regardless of the etiology (Table 1). Intent refers to the context in which a PRO should be used and generally is stratified into 3 areas: population surveillance, individual patient-clinician interactions, and research studies.4 A thorough analysis of PRO developmental properties exceeds the scope of this article. However, several key considerations are worth discussing. Each measure should clearly delineate the construct, or outcome, in addition to the population used to create the measure (eg, patients with achalasia). PROs should be assessed for reliability, construct validity, and content validity. Reliability pertains to the degree in which scores are free from measurement error, the extent to which items (ie, questions) correlate, and test–retest reliability. Construct validity includes dimensionality (evidence of whether a single or multiple subscales exist in the measure), responsiveness to change (longitudinal validity), and convergent validity (correlation with additional construct-specific measures). Central to the PRO development process is the involvement of patients and content experts (content validity). PRO measures should be readily interpretable, and the handling of missing items should be stipulated. The burden, or time required for administering and scoring the instrument, and the reading level of the PRO need to be considered.8 In short, a PRO should measure something important to patients, in a way that patients can understand, and in a way that accurately reflects the underlying symptom and disease.

Although PROs traditionally represent a method for gathering data for research, they also should be viewed as a means of improving clinical care. The monitoring of change in a particular construct represents a common application of PROs in clinical practice. This helps quantify the efficacy of an intervention and can provide insight into the comparative effectiveness of alternative therapies. For example, in a patient with an esophageal stricture, a dysphagia-specific measure could be used at baseline before an endoscopy and dilation, in follow-up evaluation after dilation, and then as a monitoring tool to determine when repeat dilation may be needed. Similarly, the Eckardt score has been used commonly to monitor response to achalasia treatments. Clinicians also may use PROs in real time to optimize patient management. The data gathered from PROs may help triage patients into treatment pathways, trigger follow-up appointments, supply patient education prompts, and produce patient and provider alerts.8 For providers engaging in clinical research, PROs administered at the point of patient intake, whether electronically through a patient portal or in the clinic, provide a means of gathering baseline data.9 A key question, however, is whether it is practical to use a PRO routinely in the clinic, esophageal function laboratory, or endoscopy suite.

These practical issues include cultivating a conducive environment for PRO utilization, considering the burden of the measure on the patient, and utilization of the results in an expedient manner.9 To promote seamless use of a PRO in clinical work-flows, a multimodal means of collecting PRO data should be arranged. Electronic PROs available through a patient portal, designed with a user-friendly and intuitive interface, facilitate patient completion of PROs at their convenience, and ideally before a clinical or procedure visit. For patients without access to the internet, tablets and/or computer terminals within the office are convenient options. Nurses or clinic staff also could help patients complete a PRO during check-in for clinic, esophageal testing, or endoscopy. The burden a PRO imposes on patients also limits the utility of a measure. For instance, PROs with a small number of questions are more likely to be completed, while scales consisting of 30 of more items are infrequently finished. Clinicians also should consider how they plan to use the results of a PRO before implementing one; if the data will not be used, then the effort to implement and collect it will be wasted. Moreover, patients will anticipate that the time required to complete a PRO will translate to an impact on their management plan and will more readily complete additional PROs if previous measures expediently affected their care.9

Barriers to patient-reported outcome implementation and future directions

Given the potential benefits to PRO use, why are they not implemented routinely? In practice, there are multiple barriers that thwart the adoption of PROs into both health care systems and individual practices. The integration of PROs into large health care systems languishes partly because of technological and operational barriers.9 For instance, the manual distribution, collection, and transcription of handwritten information requires substantial investitures of time, which is magnified by the number of patients whose care is provided within a large health system. One approach to the technological barrier includes the creation of an electronic platform integrating with patient portals. Such a platform would obviate the need to manually collect and transcribe documents, and could import data directly into provider documentation and flowsheets. However, the programming time and costs are substantial upfront, and without clear data that this could lead to improved outcomes or decreased costs downstream there may be reluctance to devote resources to this. In clinical practice, the already significant demands on providers’ time mitigates enthusiasm to add additional tasks. Providers also could face annual licensing agreements, fees on a per-study basis, or royalties associated with particular PROs, and at the individual practice level, there may not be appropriate expertise to select and implement routine PRO monitoring. To address this, efforts are being made to simplify the process of incorporating PROs. For example, given the relatively large number of heterogeneous PROs, the PROMIS project1 endeavors to clarify which PROs constitute the best measure for each construct and condition.9 The PROMIS measures also are provided publicly and are available without license or fee.

Areas particularly well situated for growth in the use of PRO measures include comparative effectiveness studies and pragmatic clinical trials. PRO-derived data may promote a shift from explanatory randomized controlled trials to pragmatic randomized controlled trials because these data emphasize patient-centered care and are more broadly generalizable to clinical settings. Furthermore, the derivation of data directly from the health care delivery system through PROs, such as two-way text messages, increases the relevance and cost effectiveness of clinical trials. Given the current medical climate, pressures continue to mount to identify cost-efficient and efficacious medical therapies.10 In this capacity, PROs facilitate the understanding of changes in HRQL domains subject to treatment choices. PROs further consider the comparative symptom burden and side effects associated with competing treatment strategies.11 Finally, PROs also have enabled the procurement of data from patient-powered research networks. Although this concept has not yet been applied to esophageal diseases, one example of this in the GI field is the Crohn’s and Colitis Foundation of America Partners project, which has built an internet cohort consisting of approximately 14,200 inflammatory bowel disease patients who are monitored with a series of PROs.12 An endeavor such as this should be a model for esophageal conditions in the future.

Conclusions

PROs, as a structured means of directly assessing symptoms, help facilitate a provider’s understanding from a patient’s perspectives. Multiple PROs have been developed to characterize constructs pertinent to esophageal diseases and symptoms. These vary in methodologic rigor, but multiple well-constructed PROs exist for symptom domains such as dysphagia and heartburn, and can be used to monitor symptoms over time and assess treatment efficacy. Implementation of esophageal PROs, both in large health systems and in routine clinical practice, is not yet standard and faces a number of barriers. However, the potential benefits are substantial and include increased patient-centeredness, more accurate and timely disease monitoring, and applicability to comparative effectiveness studies, pragmatic clinical trials, and patient-powered research networks.

References

1. Spiegel B., Hays R., Bolus R., et al. Development of the NIH Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) gastrointestinal symptom scales. Am J Gastroenterol. 2014;109:1804-14.

2. Chassany O., Shaheen N.J., Karlsson M., et al. Systematic review: symptom assessment using patient-reported outcomes in gastroesophageal reflux disease and dyspepsia. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2012;47:1412-21.

3. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services FDA Center for Drug Evaluation and Research, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services FDA Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services FDA Center for Devices and Radiological Health. Guidance for industry: patient-reported outcome measures: use in medical product development to support labeling claims: draft guidance. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2006;4:79. Available from:http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17034633%0Ahttp://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?artid=PMC1629006

Accessed May 23, 2017

4. Lipscomb J. Cancer outcomes research and the arenas of application. J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr. 2004;2004:1-7.

5. Patel D.A., Sharda R., Hovis K.L., et al. Patient-reported outcome measures in dysphagia: a systematic review of instrument development and validation. Dis Esophagus. 2017;30:1-23.

6. Vakil N.B., Halling K., Becher A., et al. Systematic review of patient-reported outcome instruments for gastroesophageal reflux disease symptoms. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;25:2-14.

7. Bedell A., Taft T.H., Keefer L. Development of the Northwestern Esophageal Quality of Life Scale: a hybrid measure for use across esophageal conditions. Am J Gastroenterol. 2016;111:493-9.

8. Farnik M., Pierzchala W. Instrument development and evaluation for patient-related outcomes assessments. Patient Relat Outcome Meas. 2012;3:1-7.

9. Wagle N.W.. Implementing patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs). N Engl J Med Catal. 2016; :1-2. Available from:

http://catalyst.nejm.org/implementing-proms-patient-reported-outcome-measures/. Accessed July 14, 2017

10. Richesson R.L., Hammond W.E., Nahm M., et al. Electronic health records based phenotyping in next-generation clinical trials: a perspective from the NIH Health Care Systems Collaboratory. J Am Med Informatics Assoc. 2013;20: e226-e231.

11. Coon C.D., McLeod L.D. Patient-reported outcomes: current perspectives and future directions. Clin Ther. 2013;35:399-401.

12. Chung A.E., Sandler R.S., Long M.D., et al. Harnessing person-generated health data to accelerate patient-centered outcomes research: The Crohn’s and Colitis Foundation of America PCORnet Patient Powered Research Network (CCFA Partners)

J Am Med Informatics Assoc. 2016;23:485-90.

13. Darling G., Eton D.T., Sulman J., et al. Validation of the functional assessment of cancer therapy esophageal cancer subscale. Cancer. 2006;107:854-63.

14. Lagergren P., Fayers P., Conroy T., et al. Clinical and psychometric validation of a questionnaire module, the EORTC QLQ-OG25, to assess health-related quality of life in patients with cancer of the oesophagus, the oesophago-gastric junction and the stomach. Eur J Cancer. 2007;43:2066-73.

15. Blazeby J.M., Conroy T., Hammerlid E., et al. Clinical and psychometric validation of an EORTC questionnaire module, the EORTC QLQ-OES18, to assess quality of life in patients with oesophageal cancer. Eur J Cancer. 2003;39:1384-94.

16. Chen A.Y., Frankowski R., Bishop-Leone J., et al. The development and validation of a dysphagia-specific quality-of-life questionnaire for patients with head and neck cancer: the M. D. Anderson dysphagia inventory. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2001;127:870-6.

17. McHorney C.A., Bricker D.E., Robbins J., et al. The SWAL-QOL outcomes tool for oropharyngeal dysphagia in adults: II. item reduction and preliminary scaling. Dysphagia. 2000;15:122-33.

18. Wallace K.L., Middleton S., Cook I.J. Development and validation of a self-report symptom inventory to assess the severity of oral-pharyngeal dysphagia. Gastroenterology. 2000;118:678-87.

19. McHorney C.A., Robbins J.A., Lomax K., et al. The SWAL-QOL and SWAL-CARE outcomes tool for oropharyngeal dysphagia in adults: III. Documentation of reliability and validity. Dysphagia. 2002;17:97-114.

20. Urbach D.R., Tomlinson G.A., Harnish J.L., et al. A measure of disease-specific health-related quality of life for achalasia. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100:1668-76.

21. Eckardt V., Aignherr C., Bernhard G. Predictors of outcome in patients with achalasia treated by pneumatic dilation. Gastroenterology. 1992;103:1732-8.

22. Dellon E.S., Irani A.M., Hill M.R., et al. Development and field testing of a novel patient-reported outcome measure of dysphagia in patients with eosinophilic esophagitis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2013;38:634-42.

23. Franciosi J.P., Hommel K., DeBrosse C.W., et al. Development of a validated patient-reported symptom metric for pediatric eosinophilic esophagitis: qualitative methods. BMC Gastroenterol. 2011;11:126.

24. Schoepfer A.M., Straumann A., Panczak R., et al. Development and validation of a symptom-based activity index for adults with eosinophilic esophagitis. Gastroenterology. 2014;147:1-24.

25. Grudell A.B., Alexander J.A., Enders F.B., et al. Validation of the Mayo Dysphagia Questionnaire. Dis Esophagus. 2007;20:202-5.

26. Rothman M., Farup C., Steward W., et al. Symptoms associated with gastroesophageal reflux disease: Development of a questionnaire for use in clinical trials. Dig Dis Sci. 2001;46:1540-9.

27. Spiegel B.M., Roberts L., Mody R., et al. The development and validation of a nocturnal gastro-oesophageal reflux disease symptom severity and impact questionnaire for adults. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2010;32:591-602.

28. Bardhan K.D., Stanghellini V., Armstrong D., et al. International validation of ReQuest in patients with endoscopy-negative gastro-oesophageal reflux disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2004;20:891-8.

29. Van Zanten S.V., Armstrong D., Barkun A., et al. Symptom overlap in patients with upper gastrointestinal complaints in the Canadian confirmatory acid suppression test (CAST) study: Further psychometric validation of the reflux disease questionnaire. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2007;25:1087-97.

30. Armstrong D., Moayyedi P., Hunt R., et al. M1870 resolution of persistent GERD symptoms after a change in therapy: EncomPASS - a cluster-randomized study in primary care. Gastroenterology. 2009;136(Suppl 1):A-435.

31. Jones R., Junghard O., Dent J., et al. Developement of the GerdQ, a tool for the diagnosis and management of gastro-oesophageal reflux disease in primary care. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2009;30:1030-8.

Dr. Reed is a senior fellow and Dr. Dillon is an associate professor of medicine and epidemiology, Center for Esophageal Diseases and Swallowing, division of gastroenterology and hepatology, University of North Carolina School of Medicine, Chapel Hill. Dr. Dellon has received research funding from Adare, Allakos, GSK, Meritage, Miraca, Nutricia, Celgene/Receptos, Regeneron, and Shire; he has been a consultant for Adare, Alivio, Allakos, AstraZeneca, Banner, Calypso, Enumeral, EsoCap, Celgene/Receptos, GSK, Regeneron, Robarts, and Shire; and has received an educational grant from Banner and Holoclara.

In my introductory comments to the practice management section last year, I wrote about cultivating competencies for value-based care. One of the key competencies was patient centeredness. Patient-reported outcomes (PROs) and patient experience measures specifically were highlighted as examples of meaningful tools for achieving patient centeredness. Starting with this month’s contribution by Drs Reed and Dellon on PROs in esophageal disease, we begin a series of articles focused on this important construct. We will follow this article with reports focused on PRO for patients with irritable bowel syndrome, inflammatory bowel disease, and chronic liver disease. These reports will not only review the importance of PROs, but also highlight the most practical approaches to measuring disease-specific PROs in clinical practice all with the goal of improving the care of our patients.

Ziad Gellad, MD, MPH, AGAF, Special Section Editor

Patients seek medical care for symptoms affecting their quality of life,1 and this is particularly true of digestive diseases, in which many common conditions are symptom predominant. However, clinician and patient perception of symptoms often conflict,2 and formalized measurement tools may have a role for optimizing symptom assessment. Patient-reported outcomes (PROs) directly capture patients’ health status from their own perspectives and can bridge the divide between patient and provider interpretation. The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) defines PROs as “any report of the status of a patient’s health condition that comes directly from the patient without interpretation of the patient’s response by a clinician or anyone else.”3

For the clinical assessment of esophageal diseases, existing physiologic and structural testing modalities cannot ascertain patient disease perception or measure the impact of symptoms on health care–associated quality of life. In contrast, by capturing patient-centric data, PROs can provide insight into the psychosocial aspects of patient disease perceptions; capture health-related quality of life (HRQL); improve provider understanding; highlight discordance between physiologic, symptom, and HRQL measures; and formalize follow-up evaluation of treatment response.1,4 Following up symptoms such as dysphagia or heartburn over time in a structured way allows clinically obtained data to be used in pragmatic or comparative effectiveness studies. PROs are now an integral part of the FDA’s drug approval process.

In this article, we review the available PROs capturing esophageal symptoms with a focus on dysphagia and heartburn measures that were developed with rigorous methodology; it is beyond the scope of this article to perform a thorough review of all upper gastrointestinal (GI) PROs or quality-of-life PROs. We then discuss how esophageal PROs may be incorporated into clinical practice now, as well as opportunities for PRO use in the future.

Esophageal symptom-specific patient-reported outcomes

The literature pertinent to upper GI and esophageal-specific PROs is heterogeneous, and the development of PROs has been variable in rigor. Two recent systematic reviews identified PROs pertinent to dysphagia and heartburn (Table 1) and both emphasized rigorous measures developed in accordance with FDA guidance.3

Patel et al5 identified 34 dysphagia-specific PRO measures, of which 10 were rigorously developed (Table 1). These measures encompassed multiple conditions including esophageal cancer (Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy Esophageal Cancer Subscale, European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality-of-Life with esophageal Cancer 25 items, European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality-of-Life with esophageal cancer 18 items, upper aerodigestive neoplasm-attributable oropharyngeal dysphagia [M.D. Anderson dysphagia inventory], mechanical and neuromyogenic oropharyngeal dysphagia [swallow quality-of-life questionnaire], Sydney Swallow Questionnaire, [swallowing quality of care], achalasia [Measure of Achalasia Disease Severity], eosinophilic esophagitis [Dysphagia Symptom Questionnaire], and general dysphagia symptoms and gastroesophageal reflux [Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System Gastrointestinal Symptom Scales (PROMIS-GI)]. PROMIS-GI, produced as part of the National Institutes of Health PROMIS program, includes rigorous measures for general dysphagia symptoms and gastroesophageal reflux in addition to lower gastrointestinal symptom measures.

The systematic review by Vakil et al6 found 15 PRO measures for gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) symptoms that underwent psychometric evaluation (Table 1). Of these, 5 measures were devised according to the developmental steps stipulated by the US FDA and the European Medicines Agency, and each measure has been used as an end point for a clinical trial. The 5 measures include the GERD Symptom Assessment Scale, the Nocturnal Gastro-oesophageal Reflux Disease Symptom Severity and Impact Questionnaire, the Reflux Questionnaire, the Reflux Disease Questionnaire, and the Proton Pump Inhibitor Acid Suppression Symptom Test (Table 1). Additional PROs capturing esophageal symptoms include the eosinophilic esophagitis symptom activity index, Eckardt score (used for achalasia), Mayo dysphagia questionnaire, and GERD-Q (Table 1).

Utilization of esophageal patient-reported outcomes in practice

Before incorporating a PRO into clinical practice, providers must appreciate the construct(s), intent, developmental measurement properties, validation strategies, and responsiveness characteristics associated with the measure.4 PROs can be symptom- and/or condition-specific. For example, this could include dysphagia associated with achalasia or eosinophilic esophagitis, postoperative dysphagia from spine surgery, or general dysphagia symptoms regardless of the etiology (Table 1). Intent refers to the context in which a PRO should be used and generally is stratified into 3 areas: population surveillance, individual patient-clinician interactions, and research studies.4 A thorough analysis of PRO developmental properties exceeds the scope of this article. However, several key considerations are worth discussing. Each measure should clearly delineate the construct, or outcome, in addition to the population used to create the measure (eg, patients with achalasia). PROs should be assessed for reliability, construct validity, and content validity. Reliability pertains to the degree in which scores are free from measurement error, the extent to which items (ie, questions) correlate, and test–retest reliability. Construct validity includes dimensionality (evidence of whether a single or multiple subscales exist in the measure), responsiveness to change (longitudinal validity), and convergent validity (correlation with additional construct-specific measures). Central to the PRO development process is the involvement of patients and content experts (content validity). PRO measures should be readily interpretable, and the handling of missing items should be stipulated. The burden, or time required for administering and scoring the instrument, and the reading level of the PRO need to be considered.8 In short, a PRO should measure something important to patients, in a way that patients can understand, and in a way that accurately reflects the underlying symptom and disease.

Although PROs traditionally represent a method for gathering data for research, they also should be viewed as a means of improving clinical care. The monitoring of change in a particular construct represents a common application of PROs in clinical practice. This helps quantify the efficacy of an intervention and can provide insight into the comparative effectiveness of alternative therapies. For example, in a patient with an esophageal stricture, a dysphagia-specific measure could be used at baseline before an endoscopy and dilation, in follow-up evaluation after dilation, and then as a monitoring tool to determine when repeat dilation may be needed. Similarly, the Eckardt score has been used commonly to monitor response to achalasia treatments. Clinicians also may use PROs in real time to optimize patient management. The data gathered from PROs may help triage patients into treatment pathways, trigger follow-up appointments, supply patient education prompts, and produce patient and provider alerts.8 For providers engaging in clinical research, PROs administered at the point of patient intake, whether electronically through a patient portal or in the clinic, provide a means of gathering baseline data.9 A key question, however, is whether it is practical to use a PRO routinely in the clinic, esophageal function laboratory, or endoscopy suite.

These practical issues include cultivating a conducive environment for PRO utilization, considering the burden of the measure on the patient, and utilization of the results in an expedient manner.9 To promote seamless use of a PRO in clinical work-flows, a multimodal means of collecting PRO data should be arranged. Electronic PROs available through a patient portal, designed with a user-friendly and intuitive interface, facilitate patient completion of PROs at their convenience, and ideally before a clinical or procedure visit. For patients without access to the internet, tablets and/or computer terminals within the office are convenient options. Nurses or clinic staff also could help patients complete a PRO during check-in for clinic, esophageal testing, or endoscopy. The burden a PRO imposes on patients also limits the utility of a measure. For instance, PROs with a small number of questions are more likely to be completed, while scales consisting of 30 of more items are infrequently finished. Clinicians also should consider how they plan to use the results of a PRO before implementing one; if the data will not be used, then the effort to implement and collect it will be wasted. Moreover, patients will anticipate that the time required to complete a PRO will translate to an impact on their management plan and will more readily complete additional PROs if previous measures expediently affected their care.9

Barriers to patient-reported outcome implementation and future directions

Given the potential benefits to PRO use, why are they not implemented routinely? In practice, there are multiple barriers that thwart the adoption of PROs into both health care systems and individual practices. The integration of PROs into large health care systems languishes partly because of technological and operational barriers.9 For instance, the manual distribution, collection, and transcription of handwritten information requires substantial investitures of time, which is magnified by the number of patients whose care is provided within a large health system. One approach to the technological barrier includes the creation of an electronic platform integrating with patient portals. Such a platform would obviate the need to manually collect and transcribe documents, and could import data directly into provider documentation and flowsheets. However, the programming time and costs are substantial upfront, and without clear data that this could lead to improved outcomes or decreased costs downstream there may be reluctance to devote resources to this. In clinical practice, the already significant demands on providers’ time mitigates enthusiasm to add additional tasks. Providers also could face annual licensing agreements, fees on a per-study basis, or royalties associated with particular PROs, and at the individual practice level, there may not be appropriate expertise to select and implement routine PRO monitoring. To address this, efforts are being made to simplify the process of incorporating PROs. For example, given the relatively large number of heterogeneous PROs, the PROMIS project1 endeavors to clarify which PROs constitute the best measure for each construct and condition.9 The PROMIS measures also are provided publicly and are available without license or fee.

Areas particularly well situated for growth in the use of PRO measures include comparative effectiveness studies and pragmatic clinical trials. PRO-derived data may promote a shift from explanatory randomized controlled trials to pragmatic randomized controlled trials because these data emphasize patient-centered care and are more broadly generalizable to clinical settings. Furthermore, the derivation of data directly from the health care delivery system through PROs, such as two-way text messages, increases the relevance and cost effectiveness of clinical trials. Given the current medical climate, pressures continue to mount to identify cost-efficient and efficacious medical therapies.10 In this capacity, PROs facilitate the understanding of changes in HRQL domains subject to treatment choices. PROs further consider the comparative symptom burden and side effects associated with competing treatment strategies.11 Finally, PROs also have enabled the procurement of data from patient-powered research networks. Although this concept has not yet been applied to esophageal diseases, one example of this in the GI field is the Crohn’s and Colitis Foundation of America Partners project, which has built an internet cohort consisting of approximately 14,200 inflammatory bowel disease patients who are monitored with a series of PROs.12 An endeavor such as this should be a model for esophageal conditions in the future.

Conclusions

PROs, as a structured means of directly assessing symptoms, help facilitate a provider’s understanding from a patient’s perspectives. Multiple PROs have been developed to characterize constructs pertinent to esophageal diseases and symptoms. These vary in methodologic rigor, but multiple well-constructed PROs exist for symptom domains such as dysphagia and heartburn, and can be used to monitor symptoms over time and assess treatment efficacy. Implementation of esophageal PROs, both in large health systems and in routine clinical practice, is not yet standard and faces a number of barriers. However, the potential benefits are substantial and include increased patient-centeredness, more accurate and timely disease monitoring, and applicability to comparative effectiveness studies, pragmatic clinical trials, and patient-powered research networks.

References

1. Spiegel B., Hays R., Bolus R., et al. Development of the NIH Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) gastrointestinal symptom scales. Am J Gastroenterol. 2014;109:1804-14.

2. Chassany O., Shaheen N.J., Karlsson M., et al. Systematic review: symptom assessment using patient-reported outcomes in gastroesophageal reflux disease and dyspepsia. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2012;47:1412-21.

3. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services FDA Center for Drug Evaluation and Research, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services FDA Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services FDA Center for Devices and Radiological Health. Guidance for industry: patient-reported outcome measures: use in medical product development to support labeling claims: draft guidance. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2006;4:79. Available from:http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17034633%0Ahttp://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?artid=PMC1629006

Accessed May 23, 2017

4. Lipscomb J. Cancer outcomes research and the arenas of application. J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr. 2004;2004:1-7.

5. Patel D.A., Sharda R., Hovis K.L., et al. Patient-reported outcome measures in dysphagia: a systematic review of instrument development and validation. Dis Esophagus. 2017;30:1-23.

6. Vakil N.B., Halling K., Becher A., et al. Systematic review of patient-reported outcome instruments for gastroesophageal reflux disease symptoms. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;25:2-14.

7. Bedell A., Taft T.H., Keefer L. Development of the Northwestern Esophageal Quality of Life Scale: a hybrid measure for use across esophageal conditions. Am J Gastroenterol. 2016;111:493-9.

8. Farnik M., Pierzchala W. Instrument development and evaluation for patient-related outcomes assessments. Patient Relat Outcome Meas. 2012;3:1-7.

9. Wagle N.W.. Implementing patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs). N Engl J Med Catal. 2016; :1-2. Available from:

http://catalyst.nejm.org/implementing-proms-patient-reported-outcome-measures/. Accessed July 14, 2017

10. Richesson R.L., Hammond W.E., Nahm M., et al. Electronic health records based phenotyping in next-generation clinical trials: a perspective from the NIH Health Care Systems Collaboratory. J Am Med Informatics Assoc. 2013;20: e226-e231.

11. Coon C.D., McLeod L.D. Patient-reported outcomes: current perspectives and future directions. Clin Ther. 2013;35:399-401.

12. Chung A.E., Sandler R.S., Long M.D., et al. Harnessing person-generated health data to accelerate patient-centered outcomes research: The Crohn’s and Colitis Foundation of America PCORnet Patient Powered Research Network (CCFA Partners)

J Am Med Informatics Assoc. 2016;23:485-90.

13. Darling G., Eton D.T., Sulman J., et al. Validation of the functional assessment of cancer therapy esophageal cancer subscale. Cancer. 2006;107:854-63.

14. Lagergren P., Fayers P., Conroy T., et al. Clinical and psychometric validation of a questionnaire module, the EORTC QLQ-OG25, to assess health-related quality of life in patients with cancer of the oesophagus, the oesophago-gastric junction and the stomach. Eur J Cancer. 2007;43:2066-73.

15. Blazeby J.M., Conroy T., Hammerlid E., et al. Clinical and psychometric validation of an EORTC questionnaire module, the EORTC QLQ-OES18, to assess quality of life in patients with oesophageal cancer. Eur J Cancer. 2003;39:1384-94.

16. Chen A.Y., Frankowski R., Bishop-Leone J., et al. The development and validation of a dysphagia-specific quality-of-life questionnaire for patients with head and neck cancer: the M. D. Anderson dysphagia inventory. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2001;127:870-6.

17. McHorney C.A., Bricker D.E., Robbins J., et al. The SWAL-QOL outcomes tool for oropharyngeal dysphagia in adults: II. item reduction and preliminary scaling. Dysphagia. 2000;15:122-33.

18. Wallace K.L., Middleton S., Cook I.J. Development and validation of a self-report symptom inventory to assess the severity of oral-pharyngeal dysphagia. Gastroenterology. 2000;118:678-87.

19. McHorney C.A., Robbins J.A., Lomax K., et al. The SWAL-QOL and SWAL-CARE outcomes tool for oropharyngeal dysphagia in adults: III. Documentation of reliability and validity. Dysphagia. 2002;17:97-114.

20. Urbach D.R., Tomlinson G.A., Harnish J.L., et al. A measure of disease-specific health-related quality of life for achalasia. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100:1668-76.

21. Eckardt V., Aignherr C., Bernhard G. Predictors of outcome in patients with achalasia treated by pneumatic dilation. Gastroenterology. 1992;103:1732-8.

22. Dellon E.S., Irani A.M., Hill M.R., et al. Development and field testing of a novel patient-reported outcome measure of dysphagia in patients with eosinophilic esophagitis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2013;38:634-42.

23. Franciosi J.P., Hommel K., DeBrosse C.W., et al. Development of a validated patient-reported symptom metric for pediatric eosinophilic esophagitis: qualitative methods. BMC Gastroenterol. 2011;11:126.

24. Schoepfer A.M., Straumann A., Panczak R., et al. Development and validation of a symptom-based activity index for adults with eosinophilic esophagitis. Gastroenterology. 2014;147:1-24.

25. Grudell A.B., Alexander J.A., Enders F.B., et al. Validation of the Mayo Dysphagia Questionnaire. Dis Esophagus. 2007;20:202-5.

26. Rothman M., Farup C., Steward W., et al. Symptoms associated with gastroesophageal reflux disease: Development of a questionnaire for use in clinical trials. Dig Dis Sci. 2001;46:1540-9.

27. Spiegel B.M., Roberts L., Mody R., et al. The development and validation of a nocturnal gastro-oesophageal reflux disease symptom severity and impact questionnaire for adults. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2010;32:591-602.

28. Bardhan K.D., Stanghellini V., Armstrong D., et al. International validation of ReQuest in patients with endoscopy-negative gastro-oesophageal reflux disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2004;20:891-8.

29. Van Zanten S.V., Armstrong D., Barkun A., et al. Symptom overlap in patients with upper gastrointestinal complaints in the Canadian confirmatory acid suppression test (CAST) study: Further psychometric validation of the reflux disease questionnaire. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2007;25:1087-97.

30. Armstrong D., Moayyedi P., Hunt R., et al. M1870 resolution of persistent GERD symptoms after a change in therapy: EncomPASS - a cluster-randomized study in primary care. Gastroenterology. 2009;136(Suppl 1):A-435.

31. Jones R., Junghard O., Dent J., et al. Developement of the GerdQ, a tool for the diagnosis and management of gastro-oesophageal reflux disease in primary care. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2009;30:1030-8.

Dr. Reed is a senior fellow and Dr. Dillon is an associate professor of medicine and epidemiology, Center for Esophageal Diseases and Swallowing, division of gastroenterology and hepatology, University of North Carolina School of Medicine, Chapel Hill. Dr. Dellon has received research funding from Adare, Allakos, GSK, Meritage, Miraca, Nutricia, Celgene/Receptos, Regeneron, and Shire; he has been a consultant for Adare, Alivio, Allakos, AstraZeneca, Banner, Calypso, Enumeral, EsoCap, Celgene/Receptos, GSK, Regeneron, Robarts, and Shire; and has received an educational grant from Banner and Holoclara.

In my introductory comments to the practice management section last year, I wrote about cultivating competencies for value-based care. One of the key competencies was patient centeredness. Patient-reported outcomes (PROs) and patient experience measures specifically were highlighted as examples of meaningful tools for achieving patient centeredness. Starting with this month’s contribution by Drs Reed and Dellon on PROs in esophageal disease, we begin a series of articles focused on this important construct. We will follow this article with reports focused on PRO for patients with irritable bowel syndrome, inflammatory bowel disease, and chronic liver disease. These reports will not only review the importance of PROs, but also highlight the most practical approaches to measuring disease-specific PROs in clinical practice all with the goal of improving the care of our patients.

Ziad Gellad, MD, MPH, AGAF, Special Section Editor

Patients seek medical care for symptoms affecting their quality of life,1 and this is particularly true of digestive diseases, in which many common conditions are symptom predominant. However, clinician and patient perception of symptoms often conflict,2 and formalized measurement tools may have a role for optimizing symptom assessment. Patient-reported outcomes (PROs) directly capture patients’ health status from their own perspectives and can bridge the divide between patient and provider interpretation. The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) defines PROs as “any report of the status of a patient’s health condition that comes directly from the patient without interpretation of the patient’s response by a clinician or anyone else.”3

For the clinical assessment of esophageal diseases, existing physiologic and structural testing modalities cannot ascertain patient disease perception or measure the impact of symptoms on health care–associated quality of life. In contrast, by capturing patient-centric data, PROs can provide insight into the psychosocial aspects of patient disease perceptions; capture health-related quality of life (HRQL); improve provider understanding; highlight discordance between physiologic, symptom, and HRQL measures; and formalize follow-up evaluation of treatment response.1,4 Following up symptoms such as dysphagia or heartburn over time in a structured way allows clinically obtained data to be used in pragmatic or comparative effectiveness studies. PROs are now an integral part of the FDA’s drug approval process.

In this article, we review the available PROs capturing esophageal symptoms with a focus on dysphagia and heartburn measures that were developed with rigorous methodology; it is beyond the scope of this article to perform a thorough review of all upper gastrointestinal (GI) PROs or quality-of-life PROs. We then discuss how esophageal PROs may be incorporated into clinical practice now, as well as opportunities for PRO use in the future.

Esophageal symptom-specific patient-reported outcomes

The literature pertinent to upper GI and esophageal-specific PROs is heterogeneous, and the development of PROs has been variable in rigor. Two recent systematic reviews identified PROs pertinent to dysphagia and heartburn (Table 1) and both emphasized rigorous measures developed in accordance with FDA guidance.3

Patel et al5 identified 34 dysphagia-specific PRO measures, of which 10 were rigorously developed (Table 1). These measures encompassed multiple conditions including esophageal cancer (Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy Esophageal Cancer Subscale, European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality-of-Life with esophageal Cancer 25 items, European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality-of-Life with esophageal cancer 18 items, upper aerodigestive neoplasm-attributable oropharyngeal dysphagia [M.D. Anderson dysphagia inventory], mechanical and neuromyogenic oropharyngeal dysphagia [swallow quality-of-life questionnaire], Sydney Swallow Questionnaire, [swallowing quality of care], achalasia [Measure of Achalasia Disease Severity], eosinophilic esophagitis [Dysphagia Symptom Questionnaire], and general dysphagia symptoms and gastroesophageal reflux [Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System Gastrointestinal Symptom Scales (PROMIS-GI)]. PROMIS-GI, produced as part of the National Institutes of Health PROMIS program, includes rigorous measures for general dysphagia symptoms and gastroesophageal reflux in addition to lower gastrointestinal symptom measures.

The systematic review by Vakil et al6 found 15 PRO measures for gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) symptoms that underwent psychometric evaluation (Table 1). Of these, 5 measures were devised according to the developmental steps stipulated by the US FDA and the European Medicines Agency, and each measure has been used as an end point for a clinical trial. The 5 measures include the GERD Symptom Assessment Scale, the Nocturnal Gastro-oesophageal Reflux Disease Symptom Severity and Impact Questionnaire, the Reflux Questionnaire, the Reflux Disease Questionnaire, and the Proton Pump Inhibitor Acid Suppression Symptom Test (Table 1). Additional PROs capturing esophageal symptoms include the eosinophilic esophagitis symptom activity index, Eckardt score (used for achalasia), Mayo dysphagia questionnaire, and GERD-Q (Table 1).

Utilization of esophageal patient-reported outcomes in practice

Before incorporating a PRO into clinical practice, providers must appreciate the construct(s), intent, developmental measurement properties, validation strategies, and responsiveness characteristics associated with the measure.4 PROs can be symptom- and/or condition-specific. For example, this could include dysphagia associated with achalasia or eosinophilic esophagitis, postoperative dysphagia from spine surgery, or general dysphagia symptoms regardless of the etiology (Table 1). Intent refers to the context in which a PRO should be used and generally is stratified into 3 areas: population surveillance, individual patient-clinician interactions, and research studies.4 A thorough analysis of PRO developmental properties exceeds the scope of this article. However, several key considerations are worth discussing. Each measure should clearly delineate the construct, or outcome, in addition to the population used to create the measure (eg, patients with achalasia). PROs should be assessed for reliability, construct validity, and content validity. Reliability pertains to the degree in which scores are free from measurement error, the extent to which items (ie, questions) correlate, and test–retest reliability. Construct validity includes dimensionality (evidence of whether a single or multiple subscales exist in the measure), responsiveness to change (longitudinal validity), and convergent validity (correlation with additional construct-specific measures). Central to the PRO development process is the involvement of patients and content experts (content validity). PRO measures should be readily interpretable, and the handling of missing items should be stipulated. The burden, or time required for administering and scoring the instrument, and the reading level of the PRO need to be considered.8 In short, a PRO should measure something important to patients, in a way that patients can understand, and in a way that accurately reflects the underlying symptom and disease.

Although PROs traditionally represent a method for gathering data for research, they also should be viewed as a means of improving clinical care. The monitoring of change in a particular construct represents a common application of PROs in clinical practice. This helps quantify the efficacy of an intervention and can provide insight into the comparative effectiveness of alternative therapies. For example, in a patient with an esophageal stricture, a dysphagia-specific measure could be used at baseline before an endoscopy and dilation, in follow-up evaluation after dilation, and then as a monitoring tool to determine when repeat dilation may be needed. Similarly, the Eckardt score has been used commonly to monitor response to achalasia treatments. Clinicians also may use PROs in real time to optimize patient management. The data gathered from PROs may help triage patients into treatment pathways, trigger follow-up appointments, supply patient education prompts, and produce patient and provider alerts.8 For providers engaging in clinical research, PROs administered at the point of patient intake, whether electronically through a patient portal or in the clinic, provide a means of gathering baseline data.9 A key question, however, is whether it is practical to use a PRO routinely in the clinic, esophageal function laboratory, or endoscopy suite.

These practical issues include cultivating a conducive environment for PRO utilization, considering the burden of the measure on the patient, and utilization of the results in an expedient manner.9 To promote seamless use of a PRO in clinical work-flows, a multimodal means of collecting PRO data should be arranged. Electronic PROs available through a patient portal, designed with a user-friendly and intuitive interface, facilitate patient completion of PROs at their convenience, and ideally before a clinical or procedure visit. For patients without access to the internet, tablets and/or computer terminals within the office are convenient options. Nurses or clinic staff also could help patients complete a PRO during check-in for clinic, esophageal testing, or endoscopy. The burden a PRO imposes on patients also limits the utility of a measure. For instance, PROs with a small number of questions are more likely to be completed, while scales consisting of 30 of more items are infrequently finished. Clinicians also should consider how they plan to use the results of a PRO before implementing one; if the data will not be used, then the effort to implement and collect it will be wasted. Moreover, patients will anticipate that the time required to complete a PRO will translate to an impact on their management plan and will more readily complete additional PROs if previous measures expediently affected their care.9

Barriers to patient-reported outcome implementation and future directions

Given the potential benefits to PRO use, why are they not implemented routinely? In practice, there are multiple barriers that thwart the adoption of PROs into both health care systems and individual practices. The integration of PROs into large health care systems languishes partly because of technological and operational barriers.9 For instance, the manual distribution, collection, and transcription of handwritten information requires substantial investitures of time, which is magnified by the number of patients whose care is provided within a large health system. One approach to the technological barrier includes the creation of an electronic platform integrating with patient portals. Such a platform would obviate the need to manually collect and transcribe documents, and could import data directly into provider documentation and flowsheets. However, the programming time and costs are substantial upfront, and without clear data that this could lead to improved outcomes or decreased costs downstream there may be reluctance to devote resources to this. In clinical practice, the already significant demands on providers’ time mitigates enthusiasm to add additional tasks. Providers also could face annual licensing agreements, fees on a per-study basis, or royalties associated with particular PROs, and at the individual practice level, there may not be appropriate expertise to select and implement routine PRO monitoring. To address this, efforts are being made to simplify the process of incorporating PROs. For example, given the relatively large number of heterogeneous PROs, the PROMIS project1 endeavors to clarify which PROs constitute the best measure for each construct and condition.9 The PROMIS measures also are provided publicly and are available without license or fee.

Areas particularly well situated for growth in the use of PRO measures include comparative effectiveness studies and pragmatic clinical trials. PRO-derived data may promote a shift from explanatory randomized controlled trials to pragmatic randomized controlled trials because these data emphasize patient-centered care and are more broadly generalizable to clinical settings. Furthermore, the derivation of data directly from the health care delivery system through PROs, such as two-way text messages, increases the relevance and cost effectiveness of clinical trials. Given the current medical climate, pressures continue to mount to identify cost-efficient and efficacious medical therapies.10 In this capacity, PROs facilitate the understanding of changes in HRQL domains subject to treatment choices. PROs further consider the comparative symptom burden and side effects associated with competing treatment strategies.11 Finally, PROs also have enabled the procurement of data from patient-powered research networks. Although this concept has not yet been applied to esophageal diseases, one example of this in the GI field is the Crohn’s and Colitis Foundation of America Partners project, which has built an internet cohort consisting of approximately 14,200 inflammatory bowel disease patients who are monitored with a series of PROs.12 An endeavor such as this should be a model for esophageal conditions in the future.

Conclusions

PROs, as a structured means of directly assessing symptoms, help facilitate a provider’s understanding from a patient’s perspectives. Multiple PROs have been developed to characterize constructs pertinent to esophageal diseases and symptoms. These vary in methodologic rigor, but multiple well-constructed PROs exist for symptom domains such as dysphagia and heartburn, and can be used to monitor symptoms over time and assess treatment efficacy. Implementation of esophageal PROs, both in large health systems and in routine clinical practice, is not yet standard and faces a number of barriers. However, the potential benefits are substantial and include increased patient-centeredness, more accurate and timely disease monitoring, and applicability to comparative effectiveness studies, pragmatic clinical trials, and patient-powered research networks.

References

1. Spiegel B., Hays R., Bolus R., et al. Development of the NIH Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) gastrointestinal symptom scales. Am J Gastroenterol. 2014;109:1804-14.

2. Chassany O., Shaheen N.J., Karlsson M., et al. Systematic review: symptom assessment using patient-reported outcomes in gastroesophageal reflux disease and dyspepsia. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2012;47:1412-21.

3. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services FDA Center for Drug Evaluation and Research, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services FDA Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services FDA Center for Devices and Radiological Health. Guidance for industry: patient-reported outcome measures: use in medical product development to support labeling claims: draft guidance. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2006;4:79. Available from:http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17034633%0Ahttp://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?artid=PMC1629006

Accessed May 23, 2017

4. Lipscomb J. Cancer outcomes research and the arenas of application. J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr. 2004;2004:1-7.

5. Patel D.A., Sharda R., Hovis K.L., et al. Patient-reported outcome measures in dysphagia: a systematic review of instrument development and validation. Dis Esophagus. 2017;30:1-23.

6. Vakil N.B., Halling K., Becher A., et al. Systematic review of patient-reported outcome instruments for gastroesophageal reflux disease symptoms. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;25:2-14.

7. Bedell A., Taft T.H., Keefer L. Development of the Northwestern Esophageal Quality of Life Scale: a hybrid measure for use across esophageal conditions. Am J Gastroenterol. 2016;111:493-9.

8. Farnik M., Pierzchala W. Instrument development and evaluation for patient-related outcomes assessments. Patient Relat Outcome Meas. 2012;3:1-7.

9. Wagle N.W.. Implementing patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs). N Engl J Med Catal. 2016; :1-2. Available from:

http://catalyst.nejm.org/implementing-proms-patient-reported-outcome-measures/. Accessed July 14, 2017

10. Richesson R.L., Hammond W.E., Nahm M., et al. Electronic health records based phenotyping in next-generation clinical trials: a perspective from the NIH Health Care Systems Collaboratory. J Am Med Informatics Assoc. 2013;20: e226-e231.

11. Coon C.D., McLeod L.D. Patient-reported outcomes: current perspectives and future directions. Clin Ther. 2013;35:399-401.

12. Chung A.E., Sandler R.S., Long M.D., et al. Harnessing person-generated health data to accelerate patient-centered outcomes research: The Crohn’s and Colitis Foundation of America PCORnet Patient Powered Research Network (CCFA Partners)

J Am Med Informatics Assoc. 2016;23:485-90.

13. Darling G., Eton D.T., Sulman J., et al. Validation of the functional assessment of cancer therapy esophageal cancer subscale. Cancer. 2006;107:854-63.

14. Lagergren P., Fayers P., Conroy T., et al. Clinical and psychometric validation of a questionnaire module, the EORTC QLQ-OG25, to assess health-related quality of life in patients with cancer of the oesophagus, the oesophago-gastric junction and the stomach. Eur J Cancer. 2007;43:2066-73.

15. Blazeby J.M., Conroy T., Hammerlid E., et al. Clinical and psychometric validation of an EORTC questionnaire module, the EORTC QLQ-OES18, to assess quality of life in patients with oesophageal cancer. Eur J Cancer. 2003;39:1384-94.

16. Chen A.Y., Frankowski R., Bishop-Leone J., et al. The development and validation of a dysphagia-specific quality-of-life questionnaire for patients with head and neck cancer: the M. D. Anderson dysphagia inventory. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2001;127:870-6.

17. McHorney C.A., Bricker D.E., Robbins J., et al. The SWAL-QOL outcomes tool for oropharyngeal dysphagia in adults: II. item reduction and preliminary scaling. Dysphagia. 2000;15:122-33.

18. Wallace K.L., Middleton S., Cook I.J. Development and validation of a self-report symptom inventory to assess the severity of oral-pharyngeal dysphagia. Gastroenterology. 2000;118:678-87.

19. McHorney C.A., Robbins J.A., Lomax K., et al. The SWAL-QOL and SWAL-CARE outcomes tool for oropharyngeal dysphagia in adults: III. Documentation of reliability and validity. Dysphagia. 2002;17:97-114.

20. Urbach D.R., Tomlinson G.A., Harnish J.L., et al. A measure of disease-specific health-related quality of life for achalasia. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100:1668-76.

21. Eckardt V., Aignherr C., Bernhard G. Predictors of outcome in patients with achalasia treated by pneumatic dilation. Gastroenterology. 1992;103:1732-8.

22. Dellon E.S., Irani A.M., Hill M.R., et al. Development and field testing of a novel patient-reported outcome measure of dysphagia in patients with eosinophilic esophagitis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2013;38:634-42.

23. Franciosi J.P., Hommel K., DeBrosse C.W., et al. Development of a validated patient-reported symptom metric for pediatric eosinophilic esophagitis: qualitative methods. BMC Gastroenterol. 2011;11:126.

24. Schoepfer A.M., Straumann A., Panczak R., et al. Development and validation of a symptom-based activity index for adults with eosinophilic esophagitis. Gastroenterology. 2014;147:1-24.

25. Grudell A.B., Alexander J.A., Enders F.B., et al. Validation of the Mayo Dysphagia Questionnaire. Dis Esophagus. 2007;20:202-5.

26. Rothman M., Farup C., Steward W., et al. Symptoms associated with gastroesophageal reflux disease: Development of a questionnaire for use in clinical trials. Dig Dis Sci. 2001;46:1540-9.

27. Spiegel B.M., Roberts L., Mody R., et al. The development and validation of a nocturnal gastro-oesophageal reflux disease symptom severity and impact questionnaire for adults. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2010;32:591-602.

28. Bardhan K.D., Stanghellini V., Armstrong D., et al. International validation of ReQuest in patients with endoscopy-negative gastro-oesophageal reflux disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2004;20:891-8.

29. Van Zanten S.V., Armstrong D., Barkun A., et al. Symptom overlap in patients with upper gastrointestinal complaints in the Canadian confirmatory acid suppression test (CAST) study: Further psychometric validation of the reflux disease questionnaire. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2007;25:1087-97.

30. Armstrong D., Moayyedi P., Hunt R., et al. M1870 resolution of persistent GERD symptoms after a change in therapy: EncomPASS - a cluster-randomized study in primary care. Gastroenterology. 2009;136(Suppl 1):A-435.

31. Jones R., Junghard O., Dent J., et al. Developement of the GerdQ, a tool for the diagnosis and management of gastro-oesophageal reflux disease in primary care. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2009;30:1030-8.

Dr. Reed is a senior fellow and Dr. Dillon is an associate professor of medicine and epidemiology, Center for Esophageal Diseases and Swallowing, division of gastroenterology and hepatology, University of North Carolina School of Medicine, Chapel Hill. Dr. Dellon has received research funding from Adare, Allakos, GSK, Meritage, Miraca, Nutricia, Celgene/Receptos, Regeneron, and Shire; he has been a consultant for Adare, Alivio, Allakos, AstraZeneca, Banner, Calypso, Enumeral, EsoCap, Celgene/Receptos, GSK, Regeneron, Robarts, and Shire; and has received an educational grant from Banner and Holoclara.