User login

The human mind: Wasted or cultivated?

Some of us seem completely blank, but our minds are predisposed to constantly engage in various mental activities. Our minds can problem solve, fantasize, remember past events, get preoccupied with a book or movie, pay attention to social relationships and/or pay attention to our relationship with ourselves, focus on what we are doing in the moment, and more.

Many of us understand that our minds sometime operate on more than one level, for example, I can be talking or listening to someone in the “front of my mind” and be thinking something seemingly unrelated in the “back of my mind.” Accordingly, Sometimes we try to take a break from this never-ending mental activity by going to sleep or even taking drugs to “turn our minds off.”

Another important aspect of our minds is “will.” I like to think that most of us are familiar with the concept of “will” and put ours to good use. We intentionally or unintentionally use our wills in various ways – to improve ourselves; have fun; dawdle our lives away on imaginary activities; accomplish something tangible (for example, write a paper or wash the kitchen floor); pay attention to what we are doing in the moment; be healthy; and practice cultivating a “sound mind.”

Many of us would agree that to be of sound mind means having the ability to be comfortable with ourselves; to have some regulation of our emotions and affects; not to worry too much, but just enough to stay motivated; and to apply our minds toward accomplishing a goal we have chosen for ourselves. A sound mind also involves having a good memory, being aware and awake, being able to sort things out and adapt to various difficulties life throws at us, solving problems creatively and effectively, being able to relax, and being able to have a purpose in our lives that we have some success in fulfilling.

As a psychiatrist, I often have been curious about how people use their minds and how they direct their mental activities, or, if they do not direct their mental activities at all and simply meander through their mental lives not doing much thinking about thinking (many of us do both). Further, what is even more curious to me is how we psychiatrists use our minds; after all, we are supposed to be the experts. Certainly, with the advent of psychoanalysis, cognitive-behavioral therapy and other techniques, we are teaching our patients, and, hopefully, learning ourselves about how to manage our minds and what they preoccupy themselves with thinking. Of course, there were the methods of Abraham A. Low, MD, about “will training,” which I consider the first iteration of CBT. Prior to psychoanalysis and Low’s ideas, there have always been various forms of mindfulness.

So, my questions to my fellow psychiatrists are: What are your doing with your mind? Are you wasting it, cultivating it, or doing a little bit of both?

Dr. Bell is staff psychiatrist at Jackson Park Hospital Surgical-Medical/Psychiatric Inpatient Unit; clinical professor emeritus, department of psychiatry, University of Illinois at Chicago; and former director of the Institute for Juvenile Research (the birthplace of child psychiatry), all in Chicago. He serves as chair of psychiatry at Windsor University, St. Kitts.

Some of us seem completely blank, but our minds are predisposed to constantly engage in various mental activities. Our minds can problem solve, fantasize, remember past events, get preoccupied with a book or movie, pay attention to social relationships and/or pay attention to our relationship with ourselves, focus on what we are doing in the moment, and more.

Many of us understand that our minds sometime operate on more than one level, for example, I can be talking or listening to someone in the “front of my mind” and be thinking something seemingly unrelated in the “back of my mind.” Accordingly, Sometimes we try to take a break from this never-ending mental activity by going to sleep or even taking drugs to “turn our minds off.”

Another important aspect of our minds is “will.” I like to think that most of us are familiar with the concept of “will” and put ours to good use. We intentionally or unintentionally use our wills in various ways – to improve ourselves; have fun; dawdle our lives away on imaginary activities; accomplish something tangible (for example, write a paper or wash the kitchen floor); pay attention to what we are doing in the moment; be healthy; and practice cultivating a “sound mind.”

Many of us would agree that to be of sound mind means having the ability to be comfortable with ourselves; to have some regulation of our emotions and affects; not to worry too much, but just enough to stay motivated; and to apply our minds toward accomplishing a goal we have chosen for ourselves. A sound mind also involves having a good memory, being aware and awake, being able to sort things out and adapt to various difficulties life throws at us, solving problems creatively and effectively, being able to relax, and being able to have a purpose in our lives that we have some success in fulfilling.

As a psychiatrist, I often have been curious about how people use their minds and how they direct their mental activities, or, if they do not direct their mental activities at all and simply meander through their mental lives not doing much thinking about thinking (many of us do both). Further, what is even more curious to me is how we psychiatrists use our minds; after all, we are supposed to be the experts. Certainly, with the advent of psychoanalysis, cognitive-behavioral therapy and other techniques, we are teaching our patients, and, hopefully, learning ourselves about how to manage our minds and what they preoccupy themselves with thinking. Of course, there were the methods of Abraham A. Low, MD, about “will training,” which I consider the first iteration of CBT. Prior to psychoanalysis and Low’s ideas, there have always been various forms of mindfulness.

So, my questions to my fellow psychiatrists are: What are your doing with your mind? Are you wasting it, cultivating it, or doing a little bit of both?

Dr. Bell is staff psychiatrist at Jackson Park Hospital Surgical-Medical/Psychiatric Inpatient Unit; clinical professor emeritus, department of psychiatry, University of Illinois at Chicago; and former director of the Institute for Juvenile Research (the birthplace of child psychiatry), all in Chicago. He serves as chair of psychiatry at Windsor University, St. Kitts.

Some of us seem completely blank, but our minds are predisposed to constantly engage in various mental activities. Our minds can problem solve, fantasize, remember past events, get preoccupied with a book or movie, pay attention to social relationships and/or pay attention to our relationship with ourselves, focus on what we are doing in the moment, and more.

Many of us understand that our minds sometime operate on more than one level, for example, I can be talking or listening to someone in the “front of my mind” and be thinking something seemingly unrelated in the “back of my mind.” Accordingly, Sometimes we try to take a break from this never-ending mental activity by going to sleep or even taking drugs to “turn our minds off.”

Another important aspect of our minds is “will.” I like to think that most of us are familiar with the concept of “will” and put ours to good use. We intentionally or unintentionally use our wills in various ways – to improve ourselves; have fun; dawdle our lives away on imaginary activities; accomplish something tangible (for example, write a paper or wash the kitchen floor); pay attention to what we are doing in the moment; be healthy; and practice cultivating a “sound mind.”

Many of us would agree that to be of sound mind means having the ability to be comfortable with ourselves; to have some regulation of our emotions and affects; not to worry too much, but just enough to stay motivated; and to apply our minds toward accomplishing a goal we have chosen for ourselves. A sound mind also involves having a good memory, being aware and awake, being able to sort things out and adapt to various difficulties life throws at us, solving problems creatively and effectively, being able to relax, and being able to have a purpose in our lives that we have some success in fulfilling.

As a psychiatrist, I often have been curious about how people use their minds and how they direct their mental activities, or, if they do not direct their mental activities at all and simply meander through their mental lives not doing much thinking about thinking (many of us do both). Further, what is even more curious to me is how we psychiatrists use our minds; after all, we are supposed to be the experts. Certainly, with the advent of psychoanalysis, cognitive-behavioral therapy and other techniques, we are teaching our patients, and, hopefully, learning ourselves about how to manage our minds and what they preoccupy themselves with thinking. Of course, there were the methods of Abraham A. Low, MD, about “will training,” which I consider the first iteration of CBT. Prior to psychoanalysis and Low’s ideas, there have always been various forms of mindfulness.

So, my questions to my fellow psychiatrists are: What are your doing with your mind? Are you wasting it, cultivating it, or doing a little bit of both?

Dr. Bell is staff psychiatrist at Jackson Park Hospital Surgical-Medical/Psychiatric Inpatient Unit; clinical professor emeritus, department of psychiatry, University of Illinois at Chicago; and former director of the Institute for Juvenile Research (the birthplace of child psychiatry), all in Chicago. He serves as chair of psychiatry at Windsor University, St. Kitts.

Is the pay-to-publish movement a good thing?

Is it me, or is anyone else worried about the online, pay-to-publish movement sweeping science?

I am being inundated with “please publish in our online journal for a fee” emails. I confess, I tried it once or twice and was pleased with the published outcome, as I communicated a concept that I thought was important to the practice of medicine. However, it was a bit disconcerting that the publishers of this online journal wanted an article within 3 weeks. Naturally, a scientific publication thrown together in 3 weeks could not be that good – unless it already had been on the drawing board for a while. Of note, the various editors of these journals often maintain that the articles are “peer reviewed.”

An article that I paid the Journal of Family Medicine and Disease Prevention to publish was one I coauthored, titled, “Prenatal vitamins deficient in recommended choline intake for pregnant women” (J Fam Med Dis Prev. 2016;2[4]1-3.)

That very straightforward article that surveyed the choline content in the top 75 prenatal vitamins showed that none of those vitamins contained the daily recommended dosage for pregnant women established by the Institute of Medicine in 1998. So, in many ways, the conclusions we drew in the article were a no-brainer and the result of simple, yet important observations that science had overlooked.

Despite the straightforward nature of that pay-to-publish article, the evidence it presented was sufficient to get the American Medical Association’s House of Delegates to pass a resolution calling for an increase in the choline content in prenatal vitamins.

So on the negative side of the ledger, I am concerned that some very “faulty science” could get published in the online, pay-to-publish journals, in light of what seems like their rush to publish. Of course, every now and then some of our prestigious journals publish information that is poorly interpreted, such as the recent article about the suicide rates among U.S. youth (JAMA Pediatr. 2018;172[7]:697-9).

Another separate, but related issue is what at least seems from a distance to be a rush by some of the tried and true medical journals (the New England Journal of Medicine, the various JAMA Network journals, The Lancet, and so on), to keep up with the trend of online journals by making their journals more accessible online.

I am concerned but not sure what to do about these new publishing trends in medicine and science. Accordingly, I will advocate that, as physicians and scientists, we learn how to read research reports critically and how to be clear when a research design is solid and leads to legitimate scientific conclusions. We must be able to discern when reports are poorly designed – and when they lead to “junk science.”

Like most things, Internet access to scientific articles is a blessing and a curse. The blessing is that more people around the world will be able to get access to scientific study and facts they can use to improve health care. The curse is that the “snake oil salespeople” may have better opportunities to convince the public that their “snake oil” works and the public should buy their “cure.”

Dr. Bell is staff psychiatrist at Jackson Park Hospital Surgical-Medical/Psychiatric Inpatient Unit; clinical professor emeritus, department of psychiatry, University of Illinois at Chicago; and former director of the Institute for Juvenile Research (the birthplace of child psychiatry), all in Chicago. He also serves as chair of psychiatry at Windsor University, St. Kitts.

Is it me, or is anyone else worried about the online, pay-to-publish movement sweeping science?

I am being inundated with “please publish in our online journal for a fee” emails. I confess, I tried it once or twice and was pleased with the published outcome, as I communicated a concept that I thought was important to the practice of medicine. However, it was a bit disconcerting that the publishers of this online journal wanted an article within 3 weeks. Naturally, a scientific publication thrown together in 3 weeks could not be that good – unless it already had been on the drawing board for a while. Of note, the various editors of these journals often maintain that the articles are “peer reviewed.”

An article that I paid the Journal of Family Medicine and Disease Prevention to publish was one I coauthored, titled, “Prenatal vitamins deficient in recommended choline intake for pregnant women” (J Fam Med Dis Prev. 2016;2[4]1-3.)

That very straightforward article that surveyed the choline content in the top 75 prenatal vitamins showed that none of those vitamins contained the daily recommended dosage for pregnant women established by the Institute of Medicine in 1998. So, in many ways, the conclusions we drew in the article were a no-brainer and the result of simple, yet important observations that science had overlooked.

Despite the straightforward nature of that pay-to-publish article, the evidence it presented was sufficient to get the American Medical Association’s House of Delegates to pass a resolution calling for an increase in the choline content in prenatal vitamins.

So on the negative side of the ledger, I am concerned that some very “faulty science” could get published in the online, pay-to-publish journals, in light of what seems like their rush to publish. Of course, every now and then some of our prestigious journals publish information that is poorly interpreted, such as the recent article about the suicide rates among U.S. youth (JAMA Pediatr. 2018;172[7]:697-9).

Another separate, but related issue is what at least seems from a distance to be a rush by some of the tried and true medical journals (the New England Journal of Medicine, the various JAMA Network journals, The Lancet, and so on), to keep up with the trend of online journals by making their journals more accessible online.

I am concerned but not sure what to do about these new publishing trends in medicine and science. Accordingly, I will advocate that, as physicians and scientists, we learn how to read research reports critically and how to be clear when a research design is solid and leads to legitimate scientific conclusions. We must be able to discern when reports are poorly designed – and when they lead to “junk science.”

Like most things, Internet access to scientific articles is a blessing and a curse. The blessing is that more people around the world will be able to get access to scientific study and facts they can use to improve health care. The curse is that the “snake oil salespeople” may have better opportunities to convince the public that their “snake oil” works and the public should buy their “cure.”

Dr. Bell is staff psychiatrist at Jackson Park Hospital Surgical-Medical/Psychiatric Inpatient Unit; clinical professor emeritus, department of psychiatry, University of Illinois at Chicago; and former director of the Institute for Juvenile Research (the birthplace of child psychiatry), all in Chicago. He also serves as chair of psychiatry at Windsor University, St. Kitts.

Is it me, or is anyone else worried about the online, pay-to-publish movement sweeping science?

I am being inundated with “please publish in our online journal for a fee” emails. I confess, I tried it once or twice and was pleased with the published outcome, as I communicated a concept that I thought was important to the practice of medicine. However, it was a bit disconcerting that the publishers of this online journal wanted an article within 3 weeks. Naturally, a scientific publication thrown together in 3 weeks could not be that good – unless it already had been on the drawing board for a while. Of note, the various editors of these journals often maintain that the articles are “peer reviewed.”

An article that I paid the Journal of Family Medicine and Disease Prevention to publish was one I coauthored, titled, “Prenatal vitamins deficient in recommended choline intake for pregnant women” (J Fam Med Dis Prev. 2016;2[4]1-3.)

That very straightforward article that surveyed the choline content in the top 75 prenatal vitamins showed that none of those vitamins contained the daily recommended dosage for pregnant women established by the Institute of Medicine in 1998. So, in many ways, the conclusions we drew in the article were a no-brainer and the result of simple, yet important observations that science had overlooked.

Despite the straightforward nature of that pay-to-publish article, the evidence it presented was sufficient to get the American Medical Association’s House of Delegates to pass a resolution calling for an increase in the choline content in prenatal vitamins.

So on the negative side of the ledger, I am concerned that some very “faulty science” could get published in the online, pay-to-publish journals, in light of what seems like their rush to publish. Of course, every now and then some of our prestigious journals publish information that is poorly interpreted, such as the recent article about the suicide rates among U.S. youth (JAMA Pediatr. 2018;172[7]:697-9).

Another separate, but related issue is what at least seems from a distance to be a rush by some of the tried and true medical journals (the New England Journal of Medicine, the various JAMA Network journals, The Lancet, and so on), to keep up with the trend of online journals by making their journals more accessible online.

I am concerned but not sure what to do about these new publishing trends in medicine and science. Accordingly, I will advocate that, as physicians and scientists, we learn how to read research reports critically and how to be clear when a research design is solid and leads to legitimate scientific conclusions. We must be able to discern when reports are poorly designed – and when they lead to “junk science.”

Like most things, Internet access to scientific articles is a blessing and a curse. The blessing is that more people around the world will be able to get access to scientific study and facts they can use to improve health care. The curse is that the “snake oil salespeople” may have better opportunities to convince the public that their “snake oil” works and the public should buy their “cure.”

Dr. Bell is staff psychiatrist at Jackson Park Hospital Surgical-Medical/Psychiatric Inpatient Unit; clinical professor emeritus, department of psychiatry, University of Illinois at Chicago; and former director of the Institute for Juvenile Research (the birthplace of child psychiatry), all in Chicago. He also serves as chair of psychiatry at Windsor University, St. Kitts.

Is the suicide story fake – or just misleading?

Recently, a lot has been in the news about the increasing rates of suicide in all communities, including among African American youth, and two high-profile celebrities. Now that we have a CEO in the White House who has made the phrase “fake news” part of the national lexicon (and as a former CEO myself), I feel compelled to take a critical, clinical look at the way the suicide story has been reported.

CEOs tend to be unique people, and many of them are fond of hyperbole – as it promotes “followship” in employees and fosters business deals. I interpret fake news as the kind of information, or maybe spin is a better word, promulgated by CEOs.

While following a research letter published recently in JAMA Pediatrics – “Age-Related Racial Disparity in Suicide Rates Among U.S. Youths From 2001 Through 2015” (2018 May 21. doi: 10.001/jamapediatrics.2018.0399) – it occurred to me that this struck me as fake news. But as I thought about it, I realized that the conclusions in the research letter would be better characterized as perhaps misleading news. My basis for reaching those conclusions is rooted in the lessons I learned as a 2-year member of the Institute of Medicine’s Board on Neuroscience and Behavioral Health, Committee on Pathophysiology & Prevention of Adolescent & Adult Suicide. In fact, the report we produced was the first one referenced in the research letter. Unfortunately, however, the research letter’s authors seemed to miss the IOM report’s major take-away messages.

For example, the research letter authors compared the suicide rates among black children and white children in this way: “However, suicide rates increased from 1993 to 1997 and 2008 to 2012 among black children aged 5 to 11 years (from 1.36 to 2.54 per million) and decreased among white children of the same age (from 1.14 to 0.77 per million).” That sentence supports the conclusions of the IOM’s “Reducing Suicide” report, as it confirms that those are very low base rates. However, because the base rates are so low in most populations, it is difficult to determine scientifically whether a significant rise or decrease in rates occurred.

To quote page 377 of IOM report: “The base rate of completed suicide is sufficiently low to preclude all but the largest of studies. When such studies are performed, resultant comparisons are between extremely small and large groups of individuals (suicide completers versus non–suicide completers, or suicide attempters versus non–suicide attempters). Use of suicidal ideation as an outcome can increase incidence and alleviate the problem to some extent; however, it is unclear whether suicidal ideation is a strong predictor of suicide completion. Using both attempts and completions can confound the analysis since attempters may account for some of the suicides completed within the study period. Because the duration of the prevention studies is frequently too brief to collect sufficient data on the low frequency endpoints of suicide or suicide attempt, proximal measures such as changes in knowledge or attitude are used. Yet the predictive value of these variables is unconfirmed.”

Further, according to page 410 of the report: “As the statistical analysis above points out, at a suicide rate of 10 per 100,000 population, approximately 100,000 participants are needed to achieve statistical significance in an experimental context. In studying suicide among low-risk groups, the numbers needed are even greater.”

Let me break this down a bit. , because the numerator is so small and the dominator is so large. Let me put it this way – if the black female suicide rates are 2/100,000, and those rates quadrupled (sounds impressive, doesn’t it?) then there would be 8/100,000 black female suicides; the difference between 2 and 8 per 100,000 is not really a significant difference because the base-rates are so small. But to say the rates quadrupled sounds scary and impressive. “Figures don’t lie, but liars can figure.”

So, the premise of the research letter is whack.

I am not impressed that the rates of black children aged 5-7 increased from 1.36/1,000,000 to 2.54/1,000,000. I am not even sure those two numbers are significantly different, much less have clinical relevance. I have tried to make this point before, but it always gets lost by the hyperbolic press – which continues to yell about suicides in the United States rising by 30% or doubling, even quadrupling. The low base rates make drawing firm conclusions from this data like spitting into the ocean. I understand that one suicide is one suicide too many. But this is not science.

The characterizations about soaring U.S. suicide rates are not exactly fake news. Instead, I would call these interpretations misleading science and news.

Dr. Bell is staff psychiatrist at Jackson Park Hospital’s surgical-medical/psychiatric inpatient unit; clinical professor emeritus, department of psychiatry, University of Illinois at Chicago; former director of the Institute for Juvenile Research (the birthplace of child psychiatry), and former president/CEO of the Community Mental Health Council, all in Chicago. He also serves as chair of psychiatry at Windsor University, St. Kitts.

Recently, a lot has been in the news about the increasing rates of suicide in all communities, including among African American youth, and two high-profile celebrities. Now that we have a CEO in the White House who has made the phrase “fake news” part of the national lexicon (and as a former CEO myself), I feel compelled to take a critical, clinical look at the way the suicide story has been reported.

CEOs tend to be unique people, and many of them are fond of hyperbole – as it promotes “followship” in employees and fosters business deals. I interpret fake news as the kind of information, or maybe spin is a better word, promulgated by CEOs.

While following a research letter published recently in JAMA Pediatrics – “Age-Related Racial Disparity in Suicide Rates Among U.S. Youths From 2001 Through 2015” (2018 May 21. doi: 10.001/jamapediatrics.2018.0399) – it occurred to me that this struck me as fake news. But as I thought about it, I realized that the conclusions in the research letter would be better characterized as perhaps misleading news. My basis for reaching those conclusions is rooted in the lessons I learned as a 2-year member of the Institute of Medicine’s Board on Neuroscience and Behavioral Health, Committee on Pathophysiology & Prevention of Adolescent & Adult Suicide. In fact, the report we produced was the first one referenced in the research letter. Unfortunately, however, the research letter’s authors seemed to miss the IOM report’s major take-away messages.

For example, the research letter authors compared the suicide rates among black children and white children in this way: “However, suicide rates increased from 1993 to 1997 and 2008 to 2012 among black children aged 5 to 11 years (from 1.36 to 2.54 per million) and decreased among white children of the same age (from 1.14 to 0.77 per million).” That sentence supports the conclusions of the IOM’s “Reducing Suicide” report, as it confirms that those are very low base rates. However, because the base rates are so low in most populations, it is difficult to determine scientifically whether a significant rise or decrease in rates occurred.

To quote page 377 of IOM report: “The base rate of completed suicide is sufficiently low to preclude all but the largest of studies. When such studies are performed, resultant comparisons are between extremely small and large groups of individuals (suicide completers versus non–suicide completers, or suicide attempters versus non–suicide attempters). Use of suicidal ideation as an outcome can increase incidence and alleviate the problem to some extent; however, it is unclear whether suicidal ideation is a strong predictor of suicide completion. Using both attempts and completions can confound the analysis since attempters may account for some of the suicides completed within the study period. Because the duration of the prevention studies is frequently too brief to collect sufficient data on the low frequency endpoints of suicide or suicide attempt, proximal measures such as changes in knowledge or attitude are used. Yet the predictive value of these variables is unconfirmed.”

Further, according to page 410 of the report: “As the statistical analysis above points out, at a suicide rate of 10 per 100,000 population, approximately 100,000 participants are needed to achieve statistical significance in an experimental context. In studying suicide among low-risk groups, the numbers needed are even greater.”

Let me break this down a bit. , because the numerator is so small and the dominator is so large. Let me put it this way – if the black female suicide rates are 2/100,000, and those rates quadrupled (sounds impressive, doesn’t it?) then there would be 8/100,000 black female suicides; the difference between 2 and 8 per 100,000 is not really a significant difference because the base-rates are so small. But to say the rates quadrupled sounds scary and impressive. “Figures don’t lie, but liars can figure.”

So, the premise of the research letter is whack.

I am not impressed that the rates of black children aged 5-7 increased from 1.36/1,000,000 to 2.54/1,000,000. I am not even sure those two numbers are significantly different, much less have clinical relevance. I have tried to make this point before, but it always gets lost by the hyperbolic press – which continues to yell about suicides in the United States rising by 30% or doubling, even quadrupling. The low base rates make drawing firm conclusions from this data like spitting into the ocean. I understand that one suicide is one suicide too many. But this is not science.

The characterizations about soaring U.S. suicide rates are not exactly fake news. Instead, I would call these interpretations misleading science and news.

Dr. Bell is staff psychiatrist at Jackson Park Hospital’s surgical-medical/psychiatric inpatient unit; clinical professor emeritus, department of psychiatry, University of Illinois at Chicago; former director of the Institute for Juvenile Research (the birthplace of child psychiatry), and former president/CEO of the Community Mental Health Council, all in Chicago. He also serves as chair of psychiatry at Windsor University, St. Kitts.

Recently, a lot has been in the news about the increasing rates of suicide in all communities, including among African American youth, and two high-profile celebrities. Now that we have a CEO in the White House who has made the phrase “fake news” part of the national lexicon (and as a former CEO myself), I feel compelled to take a critical, clinical look at the way the suicide story has been reported.

CEOs tend to be unique people, and many of them are fond of hyperbole – as it promotes “followship” in employees and fosters business deals. I interpret fake news as the kind of information, or maybe spin is a better word, promulgated by CEOs.

While following a research letter published recently in JAMA Pediatrics – “Age-Related Racial Disparity in Suicide Rates Among U.S. Youths From 2001 Through 2015” (2018 May 21. doi: 10.001/jamapediatrics.2018.0399) – it occurred to me that this struck me as fake news. But as I thought about it, I realized that the conclusions in the research letter would be better characterized as perhaps misleading news. My basis for reaching those conclusions is rooted in the lessons I learned as a 2-year member of the Institute of Medicine’s Board on Neuroscience and Behavioral Health, Committee on Pathophysiology & Prevention of Adolescent & Adult Suicide. In fact, the report we produced was the first one referenced in the research letter. Unfortunately, however, the research letter’s authors seemed to miss the IOM report’s major take-away messages.

For example, the research letter authors compared the suicide rates among black children and white children in this way: “However, suicide rates increased from 1993 to 1997 and 2008 to 2012 among black children aged 5 to 11 years (from 1.36 to 2.54 per million) and decreased among white children of the same age (from 1.14 to 0.77 per million).” That sentence supports the conclusions of the IOM’s “Reducing Suicide” report, as it confirms that those are very low base rates. However, because the base rates are so low in most populations, it is difficult to determine scientifically whether a significant rise or decrease in rates occurred.

To quote page 377 of IOM report: “The base rate of completed suicide is sufficiently low to preclude all but the largest of studies. When such studies are performed, resultant comparisons are between extremely small and large groups of individuals (suicide completers versus non–suicide completers, or suicide attempters versus non–suicide attempters). Use of suicidal ideation as an outcome can increase incidence and alleviate the problem to some extent; however, it is unclear whether suicidal ideation is a strong predictor of suicide completion. Using both attempts and completions can confound the analysis since attempters may account for some of the suicides completed within the study period. Because the duration of the prevention studies is frequently too brief to collect sufficient data on the low frequency endpoints of suicide or suicide attempt, proximal measures such as changes in knowledge or attitude are used. Yet the predictive value of these variables is unconfirmed.”

Further, according to page 410 of the report: “As the statistical analysis above points out, at a suicide rate of 10 per 100,000 population, approximately 100,000 participants are needed to achieve statistical significance in an experimental context. In studying suicide among low-risk groups, the numbers needed are even greater.”

Let me break this down a bit. , because the numerator is so small and the dominator is so large. Let me put it this way – if the black female suicide rates are 2/100,000, and those rates quadrupled (sounds impressive, doesn’t it?) then there would be 8/100,000 black female suicides; the difference between 2 and 8 per 100,000 is not really a significant difference because the base-rates are so small. But to say the rates quadrupled sounds scary and impressive. “Figures don’t lie, but liars can figure.”

So, the premise of the research letter is whack.

I am not impressed that the rates of black children aged 5-7 increased from 1.36/1,000,000 to 2.54/1,000,000. I am not even sure those two numbers are significantly different, much less have clinical relevance. I have tried to make this point before, but it always gets lost by the hyperbolic press – which continues to yell about suicides in the United States rising by 30% or doubling, even quadrupling. The low base rates make drawing firm conclusions from this data like spitting into the ocean. I understand that one suicide is one suicide too many. But this is not science.

The characterizations about soaring U.S. suicide rates are not exactly fake news. Instead, I would call these interpretations misleading science and news.

Dr. Bell is staff psychiatrist at Jackson Park Hospital’s surgical-medical/psychiatric inpatient unit; clinical professor emeritus, department of psychiatry, University of Illinois at Chicago; former director of the Institute for Juvenile Research (the birthplace of child psychiatry), and former president/CEO of the Community Mental Health Council, all in Chicago. He also serves as chair of psychiatry at Windsor University, St. Kitts.

Words do matter – especially in psychiatry

As psychiatrists, we must be more precise with our language. When we speak, we must not use psychiatric diagnoses to describe common, everyday problems in life.

For example, at the recent American Psychiatric Association meeting in New York City, I frequently heard my colleagues talking about being “traumatized” over a microinsult or a microaggression. Although these individuals suggested that they were so fragile and vulnerable that stressful events caused them to develop posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), I seriously doubted it. Moreover, with further dialogue, it became clear that they were stressed or distressed over the stressful event – not traumatized in the purest sense of the term.

Traumatic stress, on the other hand, is an event that is so painful and disruptive that it runs the risk of breaking the mind’s ability to process or make peace with the event because it is so overwhelming that it disrupts or destroys normal psychic life. Such an event has the potential of causing PTSD, which is a chronic anxiety disorder that needs to be addressed clinically. This precision may seem nitpicky; however, the research on traumatic stress is clear. If you expose 100 people to a genuine traumatic experience, about 10% of the males and 20% of the females will develop PTSD, thus, something must be protecting people from developing PTSD from exposure to trauma. The research also is lucid that catastrophizing increases the risk of developing PTSD from exposure to a trauma by about 33%, and not having a sense of self-efficacy increases the risk by an additional 33%. Accordingly, , as this is catastrophizing and minimizes the belief in self-efficacy.

Similarly, we must be careful how we use the word “depression.” My understanding is depression is a clinical phenomenon that can be disabling. Unfortunately, I often hear patients and others talking about how they are depressed over various events in life that to me are a part of living, for example, being out of a job and not being able to make a way in life. Of course, if you are out actively looking for a job, that is probably not a clinical depression that would respond to antidepressant medication, but which would respond to finding a job. If a person were depressed from not having a job and unable to summon the energy to look for a job for 2 weeks or longer, I possibly would consider them clinically depressed. It seems laypeople are always using the word “depression” interchangeably for “unhappy,” “sad,” “grief,” or even “demoralization,” and although they all have common threads and are interlinked to one another, they are also very different.

Finally, the use of the word “bipolar” seems to be creeping into common usage, as I frequently hear patients who have poor affect regulation, for example, bad tempers, referring to themselves as being “bipolar.” However, after more dialogue, it becomes clear that they are describing a loss of self-control that lasts for maybe for 30 minutes or an hour. What is more distressing are the number of psychiatrists who are willing to take the patients’ word for it that they are “bipolar” and willing to prescribe mood stabilizers for such patients.

We must do better. We must not mislead the public into thinking that the ordinary problems of living are psychiatric disorders.

Dr. Bell is staff psychiatrist at Jackson Park Hospital Surgical-Medical/Psychiatric Inpatient Unit; clinical professor emeritus, department of psychiatry, University of Illinois at Chicago; and former director of the Institute for Juvenile Research (the birthplace of child psychiatry), all in Chicago. He also serves as chair of psychiatry at Windsor University, St. Kitts.

As psychiatrists, we must be more precise with our language. When we speak, we must not use psychiatric diagnoses to describe common, everyday problems in life.

For example, at the recent American Psychiatric Association meeting in New York City, I frequently heard my colleagues talking about being “traumatized” over a microinsult or a microaggression. Although these individuals suggested that they were so fragile and vulnerable that stressful events caused them to develop posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), I seriously doubted it. Moreover, with further dialogue, it became clear that they were stressed or distressed over the stressful event – not traumatized in the purest sense of the term.

Traumatic stress, on the other hand, is an event that is so painful and disruptive that it runs the risk of breaking the mind’s ability to process or make peace with the event because it is so overwhelming that it disrupts or destroys normal psychic life. Such an event has the potential of causing PTSD, which is a chronic anxiety disorder that needs to be addressed clinically. This precision may seem nitpicky; however, the research on traumatic stress is clear. If you expose 100 people to a genuine traumatic experience, about 10% of the males and 20% of the females will develop PTSD, thus, something must be protecting people from developing PTSD from exposure to trauma. The research also is lucid that catastrophizing increases the risk of developing PTSD from exposure to a trauma by about 33%, and not having a sense of self-efficacy increases the risk by an additional 33%. Accordingly, , as this is catastrophizing and minimizes the belief in self-efficacy.

Similarly, we must be careful how we use the word “depression.” My understanding is depression is a clinical phenomenon that can be disabling. Unfortunately, I often hear patients and others talking about how they are depressed over various events in life that to me are a part of living, for example, being out of a job and not being able to make a way in life. Of course, if you are out actively looking for a job, that is probably not a clinical depression that would respond to antidepressant medication, but which would respond to finding a job. If a person were depressed from not having a job and unable to summon the energy to look for a job for 2 weeks or longer, I possibly would consider them clinically depressed. It seems laypeople are always using the word “depression” interchangeably for “unhappy,” “sad,” “grief,” or even “demoralization,” and although they all have common threads and are interlinked to one another, they are also very different.

Finally, the use of the word “bipolar” seems to be creeping into common usage, as I frequently hear patients who have poor affect regulation, for example, bad tempers, referring to themselves as being “bipolar.” However, after more dialogue, it becomes clear that they are describing a loss of self-control that lasts for maybe for 30 minutes or an hour. What is more distressing are the number of psychiatrists who are willing to take the patients’ word for it that they are “bipolar” and willing to prescribe mood stabilizers for such patients.

We must do better. We must not mislead the public into thinking that the ordinary problems of living are psychiatric disorders.

Dr. Bell is staff psychiatrist at Jackson Park Hospital Surgical-Medical/Psychiatric Inpatient Unit; clinical professor emeritus, department of psychiatry, University of Illinois at Chicago; and former director of the Institute for Juvenile Research (the birthplace of child psychiatry), all in Chicago. He also serves as chair of psychiatry at Windsor University, St. Kitts.

As psychiatrists, we must be more precise with our language. When we speak, we must not use psychiatric diagnoses to describe common, everyday problems in life.

For example, at the recent American Psychiatric Association meeting in New York City, I frequently heard my colleagues talking about being “traumatized” over a microinsult or a microaggression. Although these individuals suggested that they were so fragile and vulnerable that stressful events caused them to develop posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), I seriously doubted it. Moreover, with further dialogue, it became clear that they were stressed or distressed over the stressful event – not traumatized in the purest sense of the term.

Traumatic stress, on the other hand, is an event that is so painful and disruptive that it runs the risk of breaking the mind’s ability to process or make peace with the event because it is so overwhelming that it disrupts or destroys normal psychic life. Such an event has the potential of causing PTSD, which is a chronic anxiety disorder that needs to be addressed clinically. This precision may seem nitpicky; however, the research on traumatic stress is clear. If you expose 100 people to a genuine traumatic experience, about 10% of the males and 20% of the females will develop PTSD, thus, something must be protecting people from developing PTSD from exposure to trauma. The research also is lucid that catastrophizing increases the risk of developing PTSD from exposure to a trauma by about 33%, and not having a sense of self-efficacy increases the risk by an additional 33%. Accordingly, , as this is catastrophizing and minimizes the belief in self-efficacy.

Similarly, we must be careful how we use the word “depression.” My understanding is depression is a clinical phenomenon that can be disabling. Unfortunately, I often hear patients and others talking about how they are depressed over various events in life that to me are a part of living, for example, being out of a job and not being able to make a way in life. Of course, if you are out actively looking for a job, that is probably not a clinical depression that would respond to antidepressant medication, but which would respond to finding a job. If a person were depressed from not having a job and unable to summon the energy to look for a job for 2 weeks or longer, I possibly would consider them clinically depressed. It seems laypeople are always using the word “depression” interchangeably for “unhappy,” “sad,” “grief,” or even “demoralization,” and although they all have common threads and are interlinked to one another, they are also very different.

Finally, the use of the word “bipolar” seems to be creeping into common usage, as I frequently hear patients who have poor affect regulation, for example, bad tempers, referring to themselves as being “bipolar.” However, after more dialogue, it becomes clear that they are describing a loss of self-control that lasts for maybe for 30 minutes or an hour. What is more distressing are the number of psychiatrists who are willing to take the patients’ word for it that they are “bipolar” and willing to prescribe mood stabilizers for such patients.

We must do better. We must not mislead the public into thinking that the ordinary problems of living are psychiatric disorders.

Dr. Bell is staff psychiatrist at Jackson Park Hospital Surgical-Medical/Psychiatric Inpatient Unit; clinical professor emeritus, department of psychiatry, University of Illinois at Chicago; and former director of the Institute for Juvenile Research (the birthplace of child psychiatry), all in Chicago. He also serves as chair of psychiatry at Windsor University, St. Kitts.

Fetal alcohol syndrome: Context matters

Recently, there was a lot of hoopla in the popular press caused by the report by Philip A. May, PhD, and his team showing that the rates of fetal alcohol spectrum disorder (FASD) ran between 1.1 to 5.0% in first graders in four U.S. communities (JAMA. 2018;319[5]:474-82). This publication and the press it received made my heart sing because the findings made national news – meaning the issue would be in the public’s consciousness for a day or two. That is progress.

As psychiatrists, we should know that context is important. For example, I was at the Northeast Conference on Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorders in 2017 in Colby, Maine, and heard Larry Burd, PhD, a longstanding expert in the area of FASD, describe the drinking habits of the Native American women who had children with FASD. He described them as being alcoholics. I was floored, because engaged in social drinking during this time, but stopped cold when they realized that they were pregnant. I only saw two of 500 women that I would consider alcoholics, and one went on a 3-day binge with her girlfriends when she learned that she was pregnant. Clearly, context matters.

I continue to maintain that increasing choline in prenatal vitamins is a way out of this mess the United States is in with its hidden epidemic of FASD.

Dr. Bell is a staff psychiatrist at Jackson Park Hospital Family Medicine Clinic in Chicago; a clinical psychiatrist emeritus in the department of psychiatry at the University of Illinois at Chicago; a former president/CEO of Community Mental Health Council; and a former director of the Institute for Juvenile Research (birthplace of child psychiatry), also in Chicago.

Recently, there was a lot of hoopla in the popular press caused by the report by Philip A. May, PhD, and his team showing that the rates of fetal alcohol spectrum disorder (FASD) ran between 1.1 to 5.0% in first graders in four U.S. communities (JAMA. 2018;319[5]:474-82). This publication and the press it received made my heart sing because the findings made national news – meaning the issue would be in the public’s consciousness for a day or two. That is progress.

As psychiatrists, we should know that context is important. For example, I was at the Northeast Conference on Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorders in 2017 in Colby, Maine, and heard Larry Burd, PhD, a longstanding expert in the area of FASD, describe the drinking habits of the Native American women who had children with FASD. He described them as being alcoholics. I was floored, because engaged in social drinking during this time, but stopped cold when they realized that they were pregnant. I only saw two of 500 women that I would consider alcoholics, and one went on a 3-day binge with her girlfriends when she learned that she was pregnant. Clearly, context matters.

I continue to maintain that increasing choline in prenatal vitamins is a way out of this mess the United States is in with its hidden epidemic of FASD.

Dr. Bell is a staff psychiatrist at Jackson Park Hospital Family Medicine Clinic in Chicago; a clinical psychiatrist emeritus in the department of psychiatry at the University of Illinois at Chicago; a former president/CEO of Community Mental Health Council; and a former director of the Institute for Juvenile Research (birthplace of child psychiatry), also in Chicago.

Recently, there was a lot of hoopla in the popular press caused by the report by Philip A. May, PhD, and his team showing that the rates of fetal alcohol spectrum disorder (FASD) ran between 1.1 to 5.0% in first graders in four U.S. communities (JAMA. 2018;319[5]:474-82). This publication and the press it received made my heart sing because the findings made national news – meaning the issue would be in the public’s consciousness for a day or two. That is progress.

As psychiatrists, we should know that context is important. For example, I was at the Northeast Conference on Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorders in 2017 in Colby, Maine, and heard Larry Burd, PhD, a longstanding expert in the area of FASD, describe the drinking habits of the Native American women who had children with FASD. He described them as being alcoholics. I was floored, because engaged in social drinking during this time, but stopped cold when they realized that they were pregnant. I only saw two of 500 women that I would consider alcoholics, and one went on a 3-day binge with her girlfriends when she learned that she was pregnant. Clearly, context matters.

I continue to maintain that increasing choline in prenatal vitamins is a way out of this mess the United States is in with its hidden epidemic of FASD.

Dr. Bell is a staff psychiatrist at Jackson Park Hospital Family Medicine Clinic in Chicago; a clinical psychiatrist emeritus in the department of psychiatry at the University of Illinois at Chicago; a former president/CEO of Community Mental Health Council; and a former director of the Institute for Juvenile Research (birthplace of child psychiatry), also in Chicago.

Fetal alcohol spectrum disorders and suicidality

As psychiatrists, we understand that behavior is complex and determined by multiple factors. However, despite our understanding that behavior is cultural, sociological, psychological, and biological, we often lose sight of the biological perspective because the brain is such a complex organ and because we are inundated with psychological theories of behavior. As I have said before, we cannot abdicate our role of being biologists in the reflection of mental health and wellness.

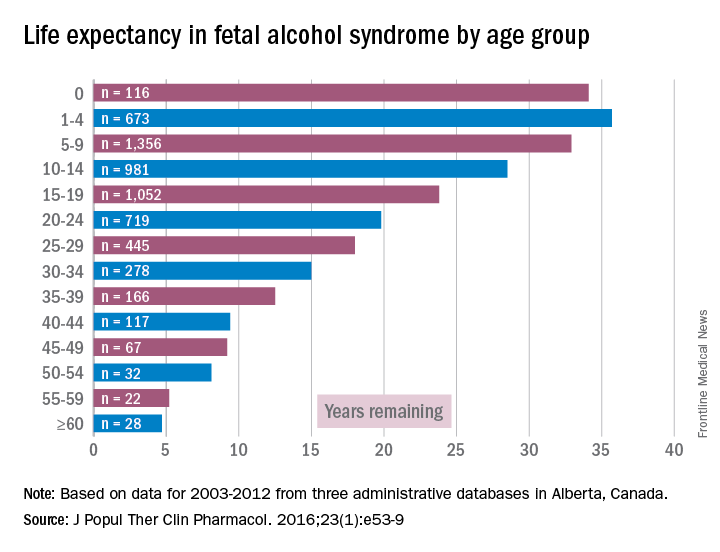

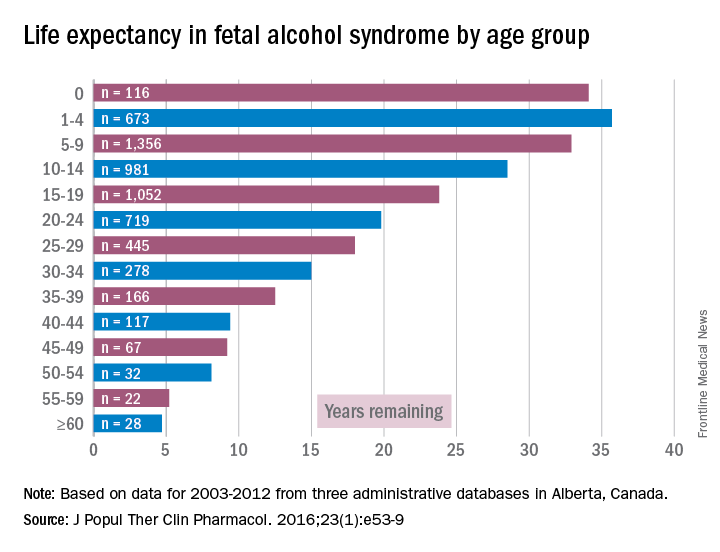

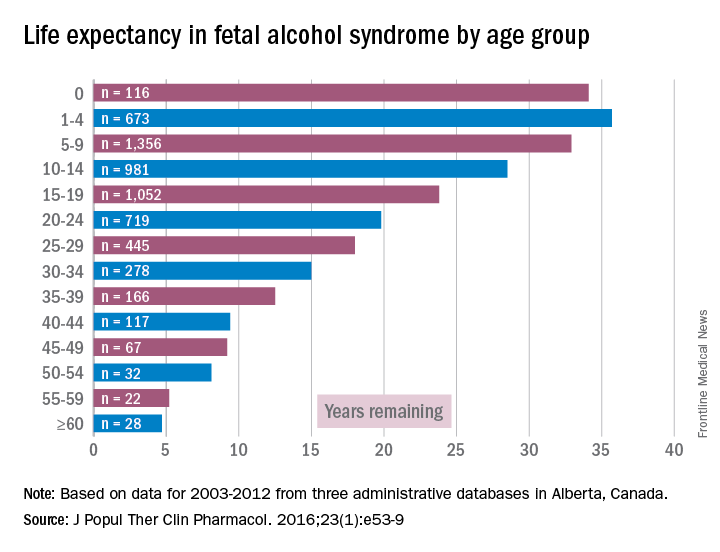

Accordingly, I feel it is my duty to bring our attention to a biologic etiology of suicidal behavior. I came across an article on the life expectancy of individuals afflicted with fetal alcohol syndrome in the Journal of Population Therapeutics and Clinical Pharmacology (2016;23[1]:e53-9). The findings were astonishing. As it turns out, the life expectancy of people with fetal alcohol syndrome is 34 years of age on average, and the leading causes of death were “external causes,” which accounted for 44% of the deaths. Suicide was responsible for 15% of those deaths, accidents for 14%, poisoning by illegal drugs or alcohol for 7%, and other external causes for another 7%, according to the article.

While working in a general hospital in a low-income African American environment where there are high rates of fetal alcohol exposure, I see at least 3-4 suicide attempts a week on the medical-surgical/psychiatric inpatient units where I serve. I am always looking for patients who have ND-PAE because determining such a diagnosis is critical to those patients’ medical-surgical care. For example, there was one woman with ND-PAE who had operable breast carcinoma but did not come in for a return visit until after her carcinoma had become inoperable (she forgot how important it was to get timely treatment). There was a patient who always had out-of-control diabetes because he did not know how to use his glucometer. There was a patient who was taking his antipsychotic medication during the day instead of as prescribed – at bedtime – because he could not read the instructions on his medication bottle. (I have altered several key aspects of my patients’ stories to protect their confidentiality.)

However, until I read that suicide was responsible for 15% of deaths with external causes among patients with fetal alcohol syndrome – patients whose life expectancy averages only 34 years – it did not occur to me that affect dysregulation also was likely to lead to suicide attempts among patients with ND-PAE.

When several of us who were working on the issue of suicide prevention while part of the Committee on Psychopathology & Prevention of Adolescent & Adult Suicide produced our report called “Reducing Suicide: A National Perspective” in 2002, the idea that paying attention to fetal environments and birth outcomes could inform the area of suicide prevention was an alien one. Now, it is a serious consideration because this dynamic just might explain part of the complex phenomena of some suicidal behaviors.

Dr. Bell is a staff psychiatrist at Jackson Park Hospital Family Medicine Clinic in Chicago; clinical psychiatrist emeritus in the department of psychiatry at the University of Illinois at Chicago; former president/CEO of Community Mental Health Council; and former director of the Institute for Juvenile Research (birthplace of child psychiatry), also in Chicago.

As psychiatrists, we understand that behavior is complex and determined by multiple factors. However, despite our understanding that behavior is cultural, sociological, psychological, and biological, we often lose sight of the biological perspective because the brain is such a complex organ and because we are inundated with psychological theories of behavior. As I have said before, we cannot abdicate our role of being biologists in the reflection of mental health and wellness.

Accordingly, I feel it is my duty to bring our attention to a biologic etiology of suicidal behavior. I came across an article on the life expectancy of individuals afflicted with fetal alcohol syndrome in the Journal of Population Therapeutics and Clinical Pharmacology (2016;23[1]:e53-9). The findings were astonishing. As it turns out, the life expectancy of people with fetal alcohol syndrome is 34 years of age on average, and the leading causes of death were “external causes,” which accounted for 44% of the deaths. Suicide was responsible for 15% of those deaths, accidents for 14%, poisoning by illegal drugs or alcohol for 7%, and other external causes for another 7%, according to the article.

While working in a general hospital in a low-income African American environment where there are high rates of fetal alcohol exposure, I see at least 3-4 suicide attempts a week on the medical-surgical/psychiatric inpatient units where I serve. I am always looking for patients who have ND-PAE because determining such a diagnosis is critical to those patients’ medical-surgical care. For example, there was one woman with ND-PAE who had operable breast carcinoma but did not come in for a return visit until after her carcinoma had become inoperable (she forgot how important it was to get timely treatment). There was a patient who always had out-of-control diabetes because he did not know how to use his glucometer. There was a patient who was taking his antipsychotic medication during the day instead of as prescribed – at bedtime – because he could not read the instructions on his medication bottle. (I have altered several key aspects of my patients’ stories to protect their confidentiality.)

However, until I read that suicide was responsible for 15% of deaths with external causes among patients with fetal alcohol syndrome – patients whose life expectancy averages only 34 years – it did not occur to me that affect dysregulation also was likely to lead to suicide attempts among patients with ND-PAE.

When several of us who were working on the issue of suicide prevention while part of the Committee on Psychopathology & Prevention of Adolescent & Adult Suicide produced our report called “Reducing Suicide: A National Perspective” in 2002, the idea that paying attention to fetal environments and birth outcomes could inform the area of suicide prevention was an alien one. Now, it is a serious consideration because this dynamic just might explain part of the complex phenomena of some suicidal behaviors.

Dr. Bell is a staff psychiatrist at Jackson Park Hospital Family Medicine Clinic in Chicago; clinical psychiatrist emeritus in the department of psychiatry at the University of Illinois at Chicago; former president/CEO of Community Mental Health Council; and former director of the Institute for Juvenile Research (birthplace of child psychiatry), also in Chicago.

As psychiatrists, we understand that behavior is complex and determined by multiple factors. However, despite our understanding that behavior is cultural, sociological, psychological, and biological, we often lose sight of the biological perspective because the brain is such a complex organ and because we are inundated with psychological theories of behavior. As I have said before, we cannot abdicate our role of being biologists in the reflection of mental health and wellness.

Accordingly, I feel it is my duty to bring our attention to a biologic etiology of suicidal behavior. I came across an article on the life expectancy of individuals afflicted with fetal alcohol syndrome in the Journal of Population Therapeutics and Clinical Pharmacology (2016;23[1]:e53-9). The findings were astonishing. As it turns out, the life expectancy of people with fetal alcohol syndrome is 34 years of age on average, and the leading causes of death were “external causes,” which accounted for 44% of the deaths. Suicide was responsible for 15% of those deaths, accidents for 14%, poisoning by illegal drugs or alcohol for 7%, and other external causes for another 7%, according to the article.

While working in a general hospital in a low-income African American environment where there are high rates of fetal alcohol exposure, I see at least 3-4 suicide attempts a week on the medical-surgical/psychiatric inpatient units where I serve. I am always looking for patients who have ND-PAE because determining such a diagnosis is critical to those patients’ medical-surgical care. For example, there was one woman with ND-PAE who had operable breast carcinoma but did not come in for a return visit until after her carcinoma had become inoperable (she forgot how important it was to get timely treatment). There was a patient who always had out-of-control diabetes because he did not know how to use his glucometer. There was a patient who was taking his antipsychotic medication during the day instead of as prescribed – at bedtime – because he could not read the instructions on his medication bottle. (I have altered several key aspects of my patients’ stories to protect their confidentiality.)

However, until I read that suicide was responsible for 15% of deaths with external causes among patients with fetal alcohol syndrome – patients whose life expectancy averages only 34 years – it did not occur to me that affect dysregulation also was likely to lead to suicide attempts among patients with ND-PAE.

When several of us who were working on the issue of suicide prevention while part of the Committee on Psychopathology & Prevention of Adolescent & Adult Suicide produced our report called “Reducing Suicide: A National Perspective” in 2002, the idea that paying attention to fetal environments and birth outcomes could inform the area of suicide prevention was an alien one. Now, it is a serious consideration because this dynamic just might explain part of the complex phenomena of some suicidal behaviors.

Dr. Bell is a staff psychiatrist at Jackson Park Hospital Family Medicine Clinic in Chicago; clinical psychiatrist emeritus in the department of psychiatry at the University of Illinois at Chicago; former president/CEO of Community Mental Health Council; and former director of the Institute for Juvenile Research (birthplace of child psychiatry), also in Chicago.

National Academy of Medicine should revisit issue of fetal alcohol exposure

More than 20 years ago the Institute of Medicine (recently renamed the National Academy of Medicine, or NAM) issued its landmark report on fetal alcohol syndrome. Since then, there has been an explosion of research on the issue of fetal alcohol exposure – and NAM needs to revisit the issue and release another report.

Unfortunately, too few physicians and not enough people in the larger society understand public health and that the health status of the unfortunate among us affects the health status of the most fortunate of us. In short, low-income people are the proverbial “canary in the coal mine.”

Accordingly, solving the health care problems of low-income people would solve the health care problems of the middle and upper class. Consider where the United States would be had we paid attention to the opioid epidemic in low-income communities instead of waiting until it spread into everyone’s “safe” communities. We would have tried and tested solutions to the problem as it currently exists.

Another reason NAM needs to revisit FASD – currently proposed to be called neurobehavioral disorders associated with prenatal alcohol exposure in the DSM-5 – are the new findings that link FASD to seizure disorders and other neurodevelopmental disorders of childhood, such as intellectual disability, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, speech and language disorders, motor disorders, specific learning disorders, and autism. In fact, new research is emerging from Robert Freedman, MD, and his team at the University of Colorado Denver, to suggest that preventing choline deficiency in pregnancy (the mechanism producing neurodevelopmental defects in FASD) may not only prevent neurodevelopmental disorders of childhood but also schizophrenia. Further, it has become abundantly clear that choline deficiency (often generated by FASD), is responsible for affect dysregulation, which is a common thread in various forms of violence and suicide.

A recent report highlighted the findings that inmates incarcerated in Mexican prisons have high rates of intellectual disability, and we know that FASD is one of the leading causes of this problem, but we are not screening for it in our juvenile detention centers, jails, or prisons. Consequently, we need to look for the prevalence of FASD in special education as well as in foster care, because these services often feed our correctional institutions. There also is some recent animal evidence suggesting that sufficient prenatal choline during pregnancy may be protective against Alzheimer’s disease – soon to be an even greater public problem in the United States. Lastly, the neuroscience findings regarding FASD also are emerging.

Hence, there is substantial information growing in various, different but overlapping areas of our systems addressing the nation’s public health and well-being. One of the most respected sources of credible science in America is the National Academy Science. The NAM should convene a meeting of the experts to examine the current state of FASD knowledge. If there is sufficient new information, the NAM needs to develop a new report on FASD. It has been 21 years since the first FAS report from the Institute of Medicine and it needs to be revisited. But it appears that the correctional, child protective services, special education, and mental health fields are not aware of the breadth of available research and its importance to the nation’s public health. Determining how fetal alcohol exposure/choline deficiency affects children and adults in special education, foster care, juvenile and adult corrections systems – along with such other social issues as prematurity, disability, unemployment, homelessness, suicide, violence, and mental health – is critical to our nation’s future.

Dr. Bell is a staff psychiatrist at Jackson Park Hospital Family Medicine Clinic in Chicago, clinical psychiatrist emeritus in the department of psychiatry at the University of Illinois at Chicago, former president/CEO of Community Mental Health Council, and former director of the Institute for Juvenile Research (birthplace of child psychiatry), also in Chicago.

More than 20 years ago the Institute of Medicine (recently renamed the National Academy of Medicine, or NAM) issued its landmark report on fetal alcohol syndrome. Since then, there has been an explosion of research on the issue of fetal alcohol exposure – and NAM needs to revisit the issue and release another report.

Unfortunately, too few physicians and not enough people in the larger society understand public health and that the health status of the unfortunate among us affects the health status of the most fortunate of us. In short, low-income people are the proverbial “canary in the coal mine.”

Accordingly, solving the health care problems of low-income people would solve the health care problems of the middle and upper class. Consider where the United States would be had we paid attention to the opioid epidemic in low-income communities instead of waiting until it spread into everyone’s “safe” communities. We would have tried and tested solutions to the problem as it currently exists.

Another reason NAM needs to revisit FASD – currently proposed to be called neurobehavioral disorders associated with prenatal alcohol exposure in the DSM-5 – are the new findings that link FASD to seizure disorders and other neurodevelopmental disorders of childhood, such as intellectual disability, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, speech and language disorders, motor disorders, specific learning disorders, and autism. In fact, new research is emerging from Robert Freedman, MD, and his team at the University of Colorado Denver, to suggest that preventing choline deficiency in pregnancy (the mechanism producing neurodevelopmental defects in FASD) may not only prevent neurodevelopmental disorders of childhood but also schizophrenia. Further, it has become abundantly clear that choline deficiency (often generated by FASD), is responsible for affect dysregulation, which is a common thread in various forms of violence and suicide.

A recent report highlighted the findings that inmates incarcerated in Mexican prisons have high rates of intellectual disability, and we know that FASD is one of the leading causes of this problem, but we are not screening for it in our juvenile detention centers, jails, or prisons. Consequently, we need to look for the prevalence of FASD in special education as well as in foster care, because these services often feed our correctional institutions. There also is some recent animal evidence suggesting that sufficient prenatal choline during pregnancy may be protective against Alzheimer’s disease – soon to be an even greater public problem in the United States. Lastly, the neuroscience findings regarding FASD also are emerging.

Hence, there is substantial information growing in various, different but overlapping areas of our systems addressing the nation’s public health and well-being. One of the most respected sources of credible science in America is the National Academy Science. The NAM should convene a meeting of the experts to examine the current state of FASD knowledge. If there is sufficient new information, the NAM needs to develop a new report on FASD. It has been 21 years since the first FAS report from the Institute of Medicine and it needs to be revisited. But it appears that the correctional, child protective services, special education, and mental health fields are not aware of the breadth of available research and its importance to the nation’s public health. Determining how fetal alcohol exposure/choline deficiency affects children and adults in special education, foster care, juvenile and adult corrections systems – along with such other social issues as prematurity, disability, unemployment, homelessness, suicide, violence, and mental health – is critical to our nation’s future.

Dr. Bell is a staff psychiatrist at Jackson Park Hospital Family Medicine Clinic in Chicago, clinical psychiatrist emeritus in the department of psychiatry at the University of Illinois at Chicago, former president/CEO of Community Mental Health Council, and former director of the Institute for Juvenile Research (birthplace of child psychiatry), also in Chicago.

More than 20 years ago the Institute of Medicine (recently renamed the National Academy of Medicine, or NAM) issued its landmark report on fetal alcohol syndrome. Since then, there has been an explosion of research on the issue of fetal alcohol exposure – and NAM needs to revisit the issue and release another report.

Unfortunately, too few physicians and not enough people in the larger society understand public health and that the health status of the unfortunate among us affects the health status of the most fortunate of us. In short, low-income people are the proverbial “canary in the coal mine.”

Accordingly, solving the health care problems of low-income people would solve the health care problems of the middle and upper class. Consider where the United States would be had we paid attention to the opioid epidemic in low-income communities instead of waiting until it spread into everyone’s “safe” communities. We would have tried and tested solutions to the problem as it currently exists.

Another reason NAM needs to revisit FASD – currently proposed to be called neurobehavioral disorders associated with prenatal alcohol exposure in the DSM-5 – are the new findings that link FASD to seizure disorders and other neurodevelopmental disorders of childhood, such as intellectual disability, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, speech and language disorders, motor disorders, specific learning disorders, and autism. In fact, new research is emerging from Robert Freedman, MD, and his team at the University of Colorado Denver, to suggest that preventing choline deficiency in pregnancy (the mechanism producing neurodevelopmental defects in FASD) may not only prevent neurodevelopmental disorders of childhood but also schizophrenia. Further, it has become abundantly clear that choline deficiency (often generated by FASD), is responsible for affect dysregulation, which is a common thread in various forms of violence and suicide.

A recent report highlighted the findings that inmates incarcerated in Mexican prisons have high rates of intellectual disability, and we know that FASD is one of the leading causes of this problem, but we are not screening for it in our juvenile detention centers, jails, or prisons. Consequently, we need to look for the prevalence of FASD in special education as well as in foster care, because these services often feed our correctional institutions. There also is some recent animal evidence suggesting that sufficient prenatal choline during pregnancy may be protective against Alzheimer’s disease – soon to be an even greater public problem in the United States. Lastly, the neuroscience findings regarding FASD also are emerging.

Hence, there is substantial information growing in various, different but overlapping areas of our systems addressing the nation’s public health and well-being. One of the most respected sources of credible science in America is the National Academy Science. The NAM should convene a meeting of the experts to examine the current state of FASD knowledge. If there is sufficient new information, the NAM needs to develop a new report on FASD. It has been 21 years since the first FAS report from the Institute of Medicine and it needs to be revisited. But it appears that the correctional, child protective services, special education, and mental health fields are not aware of the breadth of available research and its importance to the nation’s public health. Determining how fetal alcohol exposure/choline deficiency affects children and adults in special education, foster care, juvenile and adult corrections systems – along with such other social issues as prematurity, disability, unemployment, homelessness, suicide, violence, and mental health – is critical to our nation’s future.

Dr. Bell is a staff psychiatrist at Jackson Park Hospital Family Medicine Clinic in Chicago, clinical psychiatrist emeritus in the department of psychiatry at the University of Illinois at Chicago, former president/CEO of Community Mental Health Council, and former director of the Institute for Juvenile Research (birthplace of child psychiatry), also in Chicago.

AMA’s stance on choline, prenatal vitamins could bring ‘staggering’ results

For quite some time now, I’ve been urging my colleagues to follow the science on the powerful impact of choline on the brain.

In May 2017, based on studies using genetically altered mice that show the developmental changes of Down syndrome and Alzheimer’s disease at 6 months, I raised the question of whether prenatal choline could lead to the prevention of Alzheimer’s.

Thanks to the leadership of Niva Lubin-Johnson, MD, now president-elect of the National Medical Association, while a member and immediate past chair of the American Medical Association’s minority affairs section governing council*, the AMA ’s delegates passed a resolution to support an increase in choline in prenatal vitamins.

If the prenatal vitamin companies take the AMA’s resolution to heart and put more choline in their prenatal vitamins or if physicians in the United States pay attention to the AMA’s action and recommend pregnant women ensure they get adequate choline in their diets, the benefit to Americans’ public health could be staggering. Currently, it is known that choline deficiency – usually brought about by fetal alcohol exposure – is a public health problem, and choline deficiency is the leading preventable cause of intellectual disability. Public health efforts aimed at preventing intellectual disabilities from fetal alcohol exposure are designed to warn women about the risks of drinking during pregnancy; while this effort is commendable, it does not solve a very common problem – namely, women’s engaging in social drinking before they realize they are pregnant. (Psychiatric Serv. 2015 66[5]:539-42).

The late Julius B. Richmond, MD, former director of the Institute for Juvenile Research, surgeon general under former President Jimmy Carter, and one of the founders of Head Start under former President Lyndon B. Johnson, used to say that, in order to institutionalize a public policy, you need a solid scientific basis for the policy, a mechanism to actualize the policy, and the “political will” to do so. The AMA’s recommendation has the Institute of Medicine’s science behind it, so putting choline in prenatal vitamins or having physicians recommend that pregnant women get adequate doses of choline should be pretty easy to actualize. The political will to do this extremely important, biotechnical preventive intervention should be a no-brainer.

Should this AMA recommendation gain the traction it deserves, the American people might see a substantial decrease in the prevalence of premature and low-birth-weight infants, intellectual disability, ADHD, speech and language difficulties, epilepsy, heart defects, schizophrenia, Alzheimer’s disease, depression, school failure, juvenile delinquency, violence, and suicide – all of which seem to be tied to choline deficiency.

*This story was updated August 17, 2017.

For quite some time now, I’ve been urging my colleagues to follow the science on the powerful impact of choline on the brain.

In May 2017, based on studies using genetically altered mice that show the developmental changes of Down syndrome and Alzheimer’s disease at 6 months, I raised the question of whether prenatal choline could lead to the prevention of Alzheimer’s.

Thanks to the leadership of Niva Lubin-Johnson, MD, now president-elect of the National Medical Association, while a member and immediate past chair of the American Medical Association’s minority affairs section governing council*, the AMA ’s delegates passed a resolution to support an increase in choline in prenatal vitamins.