User login

Avoiding managed care’s pitfalls and pratfalls

Physician career satisfaction has declined since the mid-1990s, and managed care gets much of the blameInstant Poll). Doctors associate managed care with:

- loss of autonomy3

- increased paperwork

- less time with patients

- frustrating phone calls with insurance company representatives.

Patients come to us with many types of medical insurance, and we often are unsure if they have adequate coverage. The stakes are high; career satisfaction and practice viability depend on prompt reimbursement without hassle, and successful outcomes depend on patients getting the care they need.

The “pitfalls” of managed care in mental health practice can be minimized, however. This article describes how to decrease the frustration, time, and effort you spend obtaining authorizations and receiving reimbursement.

Case manager: Nurse or social worker employed by a health maintenance organization (HMO) who processes, reviews, and authorizes claims. Can play a clinical role with severely ill patients, helping to coordinate their care, enrolling them in wellness or disease management programs, or advocating for them within the medical system.

Claims review: Method of reviewing an enrollee’s health care service claims before reimbursement. Purpose is to validate the medical necessity of provided services and ensure that cost of service is not excessive.

Medical necessity: Services that: 1) are appropriate and necessary for diagnosis or treatment of a medical condition; 2) are provided for diagnosis and treatment of a medical condition; 3) meet standards of good medical practice within the medical community; and 4) are the appropriate level of intensity to meet the patient’s need.

Summary plan description (SPD): Document developed by an employer or government entity that details an insurance plan’s medical insurance benefits and coverage limitations.

Third-party payer: HMO or other managed care entity that administers a health care plan and arranges for payment of medical services. Clinicians are the “first party,” and patients are the “second party.”

Utilization review (UR): Prospective, concurrent, or retrospective review of medical care for appropriateness of services delivered to a patient. In hospitals, includes review of admissions, services provided, length of stay, and discharge practices. UR usually involves protocols and guidelines to track, review, and render opinions about patient care. Claims for care that fall outside these guidelines risk being denied.

Managed care primer

Understanding how managed care works can help you develop more positive interactions with these systems. Managed care exists to help control medical costs. Restricting services is one method of medical cost control, but employers and government payers also are interested in improving disease prevention, recognition, and management.

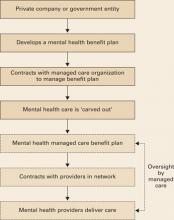

Delivering health benefits. The process begins when a business or government entity develops a summary plan description (SPD) (Box 1), defining what medical and mental health care services a policy covers (Figure).

A managed care company—typically a health maintenance organization (HMO) or similar entity—enters into a contract to implement and manage health care benefits for all persons covered by the plan. Because of their complexity, mental health services are usually “carved out” (Box 2)4 to a mental health specialty managed care company.

Utilization review. Whenever you deliver mental health care, your claims and treatment plans are scrutinized through utilization review (UR). Before authorizing payment, reviewers typically screen claims to:

- verify that the patient’s benefit plan covers the service

- establish the service’s medical necessity

- ensure that the treatment meets accepted standards of care.

UR staff in most managed care companies have administrative authority to authorize care, but care can be denied only by a medical director—typically a psychiatrist who reviews the clinical information submitted by the provider.

Figure Model of a typical managed care plan

Example 1

Claim authorization. A psychiatrist evaluates a patient and diagnoses major depression. The psychiatrist submits a treatment plan to the managed care company requesting authorization for 6 medication management and 10 psychotherapy sessions for the next 12 months. A UR representative reviews the plan, verifies the patient has appropriate coverage, and authorizes the sessions.

Example 2

Claim denial. A psychiatrist evaluates a patient and diagnoses major depression. The psychiatrist submits a treatment plan to the managed care company, requesting authorization for 10 EEG biofeedback sessions to treat the depression. A UR representative examines the plan and asks the medical director to review it. The medical director denies authorization because EEG biofeedback does not meet accepted standards for depression treatment.

Negotiating exceptions. Managed care companies must follow the letter of the benefits they administer. Some employers, however, allow for a “benefit exception” when practitioners identify patient services not covered under the benefit that, if implemented, might improve care and reduce costs.

If you encounter a situation where you believe plan limitations might adversely affect patient outcome and expense, point it out to the managed care company and ask if the patient’s plan allows benefit exceptions. Some plans do not allow for partial hospitalization, for example. If a patient with frequent inpatient admissions could be cared for in the less-intensive environment of a partial hospital program, the managed care case manager might approach the employer and suggest a benefit exception for this patient.

Common reasons claims are denied

Coverage limitations. Insurance plans often exclude or restrict particular services and limit certain types of care such as chemical dependency treatment or psychological testing. Managed care companies do not write the plans they manage and cannot authorize care that the benefit does not cover.

In “carve-out” plans, HMOs and insurance companies that do not have in-house expertise in mental health care or chemical dependency treatment “carve out” these services so that coverage is managed separately from the medical benefit. Carved-out services typically are delivered exclusively by designated providers or groups that contract with the HMO to provide mental health care to members.

Carve-outs have led to concerns about parity, particularly when mental health benefits are reduced or restricted compared with other medical benefits in the plan.

In a “carve-in” plan, mental health care remains within the overall health care coverage, which can facilitate collaboration between mental health and medical care providers. Parity for mental health care may be less of an issue than with “carve-out” plans, but “carve-in” plans might not be equipped to adequately meet the needs of patients with serious, persistent mental illness.4

Recommendation. Make sure you and your patients understand their benefit limitations. All employees with health insurance receive a summary plan description (SPD), which outlines benefit coverage and limitations. Encourage patients to read this document and contact their managed care companies with questions about coverage. Also ensure that your office managers:

- become familiar with SPDs for commonly encountered plans in your practice

- proactively verify patient benefit coverage.

Medical necessity. Practitioners in inpatient or residential settings experience the highest rates of denials of requested care on grounds that care is not medically necessary. Managed care company guidelines specify criteria that must be met—such as active suicidality, disorganized thinking, or significant medical co-morbidity—before care can be authorized.

Recommendation. Document specifically and concisely in daily notes why a patient requires the care you are providing. Managed care company guidelines are only guidelines; when the patient does not meet criteria, the medical director is more likely to authorize care if you clearly state the rationale for that level of care.

Patient is not progressing. Medical and mental health care is expected to provide a therapeutic outcome. When little progress is being made toward treatment goals, managed care companies have an obligation to the payers they represent to ensure that patients receive effective care.

Recommendation. Set realistic goals in the treatment plan. If a patient has a chronic condition and is not expected to improve but requires ongoing care to maintain function, state this in the treatment plan. If a patient is not making progress toward treatment goals, explain the reason and how you are addressing it.

No prior authorization. Some services—such as psychometric testing, inpatient care, or residential treatment—require prior authorization for reimbursement. Particularly for expensive treatments, payers require prior authorization so that utilization review occurs while care is being delivered, as opposed to afterward when costs are more difficult to contain.

Recommendation. Be familiar with prior authorization policies of common plans in your practice. If you discover you have provided care that required prior authorization, make a good-faith effort to submit clinical notes and explain why you did not request prior authorization. Many managed care companies will authorize payment after the fact if care was necessary and reasonable.

Duplication of services. Psychiatric patients often move from practice to practice, sometimes several times a year, without telling clinicians. Thus, laboratory testing, psychometric testing, and other diagnostic services may be repeated. Managed care companies take the stance that duplication of services is expensive and unnecessary, whereas you may argue that you must have adequate information to care for patients appropriately.

Recommendation. When assessing new patients, make it a priority for your office staff to ask patients about care they have received in the last year and obtain records from other providers. If you duplicate services, explain in your treatment plan why it was necessary for your patient’s care.

Interacting with managed care

Unfortunately, clinicians and managed care company representatives often view their relationship as adversarial (Box 3). Yes, some managed care representatives unfairly limit mental health care, and some clinicians maximize income potential by overbilling or providing unnecessary care. In our experience, however, most people on both sides of the equation are doing their jobs fairly and reasonably.

Medical care is expensive. Managed care’s role is not to deny care to patients who need it but to help the fiduciaries they represent—private companies or government entities—ensure that appropriate and economically responsible care is delivered. When you interact with managed care companies, keep 3 principles in mind:

Use common courtesy. Standing up for your patients and practice is reasonable and appropriate. At the same time, treating managed care representatives respectfully and professionally will go a long way as you advocate for your patients.

Document clearly and concisely. Documenting your impressions, goals, and care plans succinctly and well in your notes will save you and the managed care company time, frustration, and dollars. Managed care representatives do not want to review illegible, poorly organized, or overly inclusive documentation.

Some practitioners choose to practice outside of managed care networks—such as in fee for service—thus freeing themselves from guidelines and care limitations associated with managed care. Most health plans permit patients to seek treatment from out-of-network practitioners, although usually with higher out-of-pocket expenses.

Out-of-network practitioners who submit claims to managed care companies must follow many of the in-network rules, such as establishing medical necessity, submitting treatment plans, and undergoing utilization review.

Advantages of being an out-of-network provider—especially in a fee-for-service model—include practice independence, freedom from managed care paperwork, and the possibility of increased revenue by not having to accept reimbursement rates set by managed care contracts.

Disadvantages include potentially seeing fewer patients because of higher out-of-network costs, excluding lower-income patients, and receiving fewer referrals from managed care companies.

Out-of-network practitioners also have not gone through managed care companies’ credentialing, a process that assures patients that network practitioners are licensed and have not had serious quality-of-care or malpractice events that might adversely affect patient care.

Denials take managed care representatives more time than approvals. These busy people often look for reasons to approve reasonable care rather than to deny unreasonable care. If your documentation is clear and practice patterns are sound, your inpatient and outpatient treatment plans are much more likely to avoid the harsh scrutiny of the authorization denial process.

Managed care companies rely on the information you provide. The most common reason for denials being reversed on appeal is that additional information unavailable to the company at the initial review has been provided in the appeals process.

Learn from denials. Whenever you are issued a care denial, find out why. If a pattern emerges, you might need to change your practice or accept that certain types of care will not be covered routinely. For example, you might obtain psychological testing for every patient, whereas many managed care companies authorize testing only in specific circumstances. Thus, you could:

- modify use of testing

- or accept that this practice will not always be reimbursed.

Wellness and prevention programs

Managed care plays an important role in developing and implementing wellness, disease prevention, and disease management programs for employers and government entities. These patient programs reduce health care costs, decrease time away from work (absenteeism), and improve productivity (“presentee-ism”).5,6 Benefit plans often provide free programs and offer financial incentives for patients’ participation.

Health risk assessments, life-style coaching, and condition-specific management programs—such as for diabetes care, smoking cessation, or depression treatment—are becoming common in employee benefit packages. These programs try to improve patients’ health through care coordination with the patients’ health care providers.

As programs are developed, you can expect to regularly receive clinical information about your patients from managed care case managers who are trying to integrate their programs with your patients’ care. Case managers’ goal is to improve clinical outcomes through initiatives such as treatment adherence, patient education, and early detection of treatment resistance or symptom relapse. To take advantage of these resources, be aware of available programs and consider referring patients into them.

Related resources

- Fauman MA. Negotiating managed care: a manual for clinicians. Washington, D.C.: American Psychiatric Publishing; 2002.

- Tuckfelt S, Fink J, Prince Warren M. The psychotherapist’s guide to managed care in the 21st century. Northvale, NJ: Jason Aronson; 1997.

Disclosure

Dr. Sutor is a practicing psychiatrist at the Mayo Clinic, Rochester, MN, and has been assistant medical director for behavioral health at MMSI (the Mayo Clinic’s managed care entity) since 2001.

1. Landon BE, Reschovsky J, Blumenthal D. Changes in career satisfaction among primary care and specialist physicians, 1997-2001. JAMA 2003;289:442-9.

2. Iglehart JK. Health policy report: managed care and mental health. N Engl J Med 1996;334(2):131-5.

3. Wells LA. Psychiatry, managed care, and crooked thinking. Mayo Clin Proc 1998;73(5):483-7.

4. Bartels SJ, Levine KJ, Shea D. Community-based long-term care for older patients with severe and persistent mental illness in the era of managed care. Psychiatr Serv 1999;50:1189-97.

5. Rost K, Smith JL, Dickinson M. The effect of improving primary care depression management on employee absenteeism and productivity. A randomized trial. Medical Care 2004;42(12):1202-10.

6. Keitner GI, Ryan CE, Solomon DA. Realistic expectations and a disease management model for depressed patients with persistent symptoms. J Clin Psychiatry 2006;67(9):1412-21.

Physician career satisfaction has declined since the mid-1990s, and managed care gets much of the blameInstant Poll). Doctors associate managed care with:

- loss of autonomy3

- increased paperwork

- less time with patients

- frustrating phone calls with insurance company representatives.

Patients come to us with many types of medical insurance, and we often are unsure if they have adequate coverage. The stakes are high; career satisfaction and practice viability depend on prompt reimbursement without hassle, and successful outcomes depend on patients getting the care they need.

The “pitfalls” of managed care in mental health practice can be minimized, however. This article describes how to decrease the frustration, time, and effort you spend obtaining authorizations and receiving reimbursement.

Case manager: Nurse or social worker employed by a health maintenance organization (HMO) who processes, reviews, and authorizes claims. Can play a clinical role with severely ill patients, helping to coordinate their care, enrolling them in wellness or disease management programs, or advocating for them within the medical system.

Claims review: Method of reviewing an enrollee’s health care service claims before reimbursement. Purpose is to validate the medical necessity of provided services and ensure that cost of service is not excessive.

Medical necessity: Services that: 1) are appropriate and necessary for diagnosis or treatment of a medical condition; 2) are provided for diagnosis and treatment of a medical condition; 3) meet standards of good medical practice within the medical community; and 4) are the appropriate level of intensity to meet the patient’s need.

Summary plan description (SPD): Document developed by an employer or government entity that details an insurance plan’s medical insurance benefits and coverage limitations.

Third-party payer: HMO or other managed care entity that administers a health care plan and arranges for payment of medical services. Clinicians are the “first party,” and patients are the “second party.”

Utilization review (UR): Prospective, concurrent, or retrospective review of medical care for appropriateness of services delivered to a patient. In hospitals, includes review of admissions, services provided, length of stay, and discharge practices. UR usually involves protocols and guidelines to track, review, and render opinions about patient care. Claims for care that fall outside these guidelines risk being denied.

Managed care primer

Understanding how managed care works can help you develop more positive interactions with these systems. Managed care exists to help control medical costs. Restricting services is one method of medical cost control, but employers and government payers also are interested in improving disease prevention, recognition, and management.

Delivering health benefits. The process begins when a business or government entity develops a summary plan description (SPD) (Box 1), defining what medical and mental health care services a policy covers (Figure).

A managed care company—typically a health maintenance organization (HMO) or similar entity—enters into a contract to implement and manage health care benefits for all persons covered by the plan. Because of their complexity, mental health services are usually “carved out” (Box 2)4 to a mental health specialty managed care company.

Utilization review. Whenever you deliver mental health care, your claims and treatment plans are scrutinized through utilization review (UR). Before authorizing payment, reviewers typically screen claims to:

- verify that the patient’s benefit plan covers the service

- establish the service’s medical necessity

- ensure that the treatment meets accepted standards of care.

UR staff in most managed care companies have administrative authority to authorize care, but care can be denied only by a medical director—typically a psychiatrist who reviews the clinical information submitted by the provider.

Figure Model of a typical managed care plan

Example 1

Claim authorization. A psychiatrist evaluates a patient and diagnoses major depression. The psychiatrist submits a treatment plan to the managed care company requesting authorization for 6 medication management and 10 psychotherapy sessions for the next 12 months. A UR representative reviews the plan, verifies the patient has appropriate coverage, and authorizes the sessions.

Example 2

Claim denial. A psychiatrist evaluates a patient and diagnoses major depression. The psychiatrist submits a treatment plan to the managed care company, requesting authorization for 10 EEG biofeedback sessions to treat the depression. A UR representative examines the plan and asks the medical director to review it. The medical director denies authorization because EEG biofeedback does not meet accepted standards for depression treatment.

Negotiating exceptions. Managed care companies must follow the letter of the benefits they administer. Some employers, however, allow for a “benefit exception” when practitioners identify patient services not covered under the benefit that, if implemented, might improve care and reduce costs.

If you encounter a situation where you believe plan limitations might adversely affect patient outcome and expense, point it out to the managed care company and ask if the patient’s plan allows benefit exceptions. Some plans do not allow for partial hospitalization, for example. If a patient with frequent inpatient admissions could be cared for in the less-intensive environment of a partial hospital program, the managed care case manager might approach the employer and suggest a benefit exception for this patient.

Common reasons claims are denied

Coverage limitations. Insurance plans often exclude or restrict particular services and limit certain types of care such as chemical dependency treatment or psychological testing. Managed care companies do not write the plans they manage and cannot authorize care that the benefit does not cover.

In “carve-out” plans, HMOs and insurance companies that do not have in-house expertise in mental health care or chemical dependency treatment “carve out” these services so that coverage is managed separately from the medical benefit. Carved-out services typically are delivered exclusively by designated providers or groups that contract with the HMO to provide mental health care to members.

Carve-outs have led to concerns about parity, particularly when mental health benefits are reduced or restricted compared with other medical benefits in the plan.

In a “carve-in” plan, mental health care remains within the overall health care coverage, which can facilitate collaboration between mental health and medical care providers. Parity for mental health care may be less of an issue than with “carve-out” plans, but “carve-in” plans might not be equipped to adequately meet the needs of patients with serious, persistent mental illness.4

Recommendation. Make sure you and your patients understand their benefit limitations. All employees with health insurance receive a summary plan description (SPD), which outlines benefit coverage and limitations. Encourage patients to read this document and contact their managed care companies with questions about coverage. Also ensure that your office managers:

- become familiar with SPDs for commonly encountered plans in your practice

- proactively verify patient benefit coverage.

Medical necessity. Practitioners in inpatient or residential settings experience the highest rates of denials of requested care on grounds that care is not medically necessary. Managed care company guidelines specify criteria that must be met—such as active suicidality, disorganized thinking, or significant medical co-morbidity—before care can be authorized.

Recommendation. Document specifically and concisely in daily notes why a patient requires the care you are providing. Managed care company guidelines are only guidelines; when the patient does not meet criteria, the medical director is more likely to authorize care if you clearly state the rationale for that level of care.

Patient is not progressing. Medical and mental health care is expected to provide a therapeutic outcome. When little progress is being made toward treatment goals, managed care companies have an obligation to the payers they represent to ensure that patients receive effective care.

Recommendation. Set realistic goals in the treatment plan. If a patient has a chronic condition and is not expected to improve but requires ongoing care to maintain function, state this in the treatment plan. If a patient is not making progress toward treatment goals, explain the reason and how you are addressing it.

No prior authorization. Some services—such as psychometric testing, inpatient care, or residential treatment—require prior authorization for reimbursement. Particularly for expensive treatments, payers require prior authorization so that utilization review occurs while care is being delivered, as opposed to afterward when costs are more difficult to contain.

Recommendation. Be familiar with prior authorization policies of common plans in your practice. If you discover you have provided care that required prior authorization, make a good-faith effort to submit clinical notes and explain why you did not request prior authorization. Many managed care companies will authorize payment after the fact if care was necessary and reasonable.

Duplication of services. Psychiatric patients often move from practice to practice, sometimes several times a year, without telling clinicians. Thus, laboratory testing, psychometric testing, and other diagnostic services may be repeated. Managed care companies take the stance that duplication of services is expensive and unnecessary, whereas you may argue that you must have adequate information to care for patients appropriately.

Recommendation. When assessing new patients, make it a priority for your office staff to ask patients about care they have received in the last year and obtain records from other providers. If you duplicate services, explain in your treatment plan why it was necessary for your patient’s care.

Interacting with managed care

Unfortunately, clinicians and managed care company representatives often view their relationship as adversarial (Box 3). Yes, some managed care representatives unfairly limit mental health care, and some clinicians maximize income potential by overbilling or providing unnecessary care. In our experience, however, most people on both sides of the equation are doing their jobs fairly and reasonably.

Medical care is expensive. Managed care’s role is not to deny care to patients who need it but to help the fiduciaries they represent—private companies or government entities—ensure that appropriate and economically responsible care is delivered. When you interact with managed care companies, keep 3 principles in mind:

Use common courtesy. Standing up for your patients and practice is reasonable and appropriate. At the same time, treating managed care representatives respectfully and professionally will go a long way as you advocate for your patients.

Document clearly and concisely. Documenting your impressions, goals, and care plans succinctly and well in your notes will save you and the managed care company time, frustration, and dollars. Managed care representatives do not want to review illegible, poorly organized, or overly inclusive documentation.

Some practitioners choose to practice outside of managed care networks—such as in fee for service—thus freeing themselves from guidelines and care limitations associated with managed care. Most health plans permit patients to seek treatment from out-of-network practitioners, although usually with higher out-of-pocket expenses.

Out-of-network practitioners who submit claims to managed care companies must follow many of the in-network rules, such as establishing medical necessity, submitting treatment plans, and undergoing utilization review.

Advantages of being an out-of-network provider—especially in a fee-for-service model—include practice independence, freedom from managed care paperwork, and the possibility of increased revenue by not having to accept reimbursement rates set by managed care contracts.

Disadvantages include potentially seeing fewer patients because of higher out-of-network costs, excluding lower-income patients, and receiving fewer referrals from managed care companies.

Out-of-network practitioners also have not gone through managed care companies’ credentialing, a process that assures patients that network practitioners are licensed and have not had serious quality-of-care or malpractice events that might adversely affect patient care.

Denials take managed care representatives more time than approvals. These busy people often look for reasons to approve reasonable care rather than to deny unreasonable care. If your documentation is clear and practice patterns are sound, your inpatient and outpatient treatment plans are much more likely to avoid the harsh scrutiny of the authorization denial process.

Managed care companies rely on the information you provide. The most common reason for denials being reversed on appeal is that additional information unavailable to the company at the initial review has been provided in the appeals process.

Learn from denials. Whenever you are issued a care denial, find out why. If a pattern emerges, you might need to change your practice or accept that certain types of care will not be covered routinely. For example, you might obtain psychological testing for every patient, whereas many managed care companies authorize testing only in specific circumstances. Thus, you could:

- modify use of testing

- or accept that this practice will not always be reimbursed.

Wellness and prevention programs

Managed care plays an important role in developing and implementing wellness, disease prevention, and disease management programs for employers and government entities. These patient programs reduce health care costs, decrease time away from work (absenteeism), and improve productivity (“presentee-ism”).5,6 Benefit plans often provide free programs and offer financial incentives for patients’ participation.

Health risk assessments, life-style coaching, and condition-specific management programs—such as for diabetes care, smoking cessation, or depression treatment—are becoming common in employee benefit packages. These programs try to improve patients’ health through care coordination with the patients’ health care providers.

As programs are developed, you can expect to regularly receive clinical information about your patients from managed care case managers who are trying to integrate their programs with your patients’ care. Case managers’ goal is to improve clinical outcomes through initiatives such as treatment adherence, patient education, and early detection of treatment resistance or symptom relapse. To take advantage of these resources, be aware of available programs and consider referring patients into them.

Related resources

- Fauman MA. Negotiating managed care: a manual for clinicians. Washington, D.C.: American Psychiatric Publishing; 2002.

- Tuckfelt S, Fink J, Prince Warren M. The psychotherapist’s guide to managed care in the 21st century. Northvale, NJ: Jason Aronson; 1997.

Disclosure

Dr. Sutor is a practicing psychiatrist at the Mayo Clinic, Rochester, MN, and has been assistant medical director for behavioral health at MMSI (the Mayo Clinic’s managed care entity) since 2001.

Physician career satisfaction has declined since the mid-1990s, and managed care gets much of the blameInstant Poll). Doctors associate managed care with:

- loss of autonomy3

- increased paperwork

- less time with patients

- frustrating phone calls with insurance company representatives.

Patients come to us with many types of medical insurance, and we often are unsure if they have adequate coverage. The stakes are high; career satisfaction and practice viability depend on prompt reimbursement without hassle, and successful outcomes depend on patients getting the care they need.

The “pitfalls” of managed care in mental health practice can be minimized, however. This article describes how to decrease the frustration, time, and effort you spend obtaining authorizations and receiving reimbursement.

Case manager: Nurse or social worker employed by a health maintenance organization (HMO) who processes, reviews, and authorizes claims. Can play a clinical role with severely ill patients, helping to coordinate their care, enrolling them in wellness or disease management programs, or advocating for them within the medical system.

Claims review: Method of reviewing an enrollee’s health care service claims before reimbursement. Purpose is to validate the medical necessity of provided services and ensure that cost of service is not excessive.

Medical necessity: Services that: 1) are appropriate and necessary for diagnosis or treatment of a medical condition; 2) are provided for diagnosis and treatment of a medical condition; 3) meet standards of good medical practice within the medical community; and 4) are the appropriate level of intensity to meet the patient’s need.

Summary plan description (SPD): Document developed by an employer or government entity that details an insurance plan’s medical insurance benefits and coverage limitations.

Third-party payer: HMO or other managed care entity that administers a health care plan and arranges for payment of medical services. Clinicians are the “first party,” and patients are the “second party.”

Utilization review (UR): Prospective, concurrent, or retrospective review of medical care for appropriateness of services delivered to a patient. In hospitals, includes review of admissions, services provided, length of stay, and discharge practices. UR usually involves protocols and guidelines to track, review, and render opinions about patient care. Claims for care that fall outside these guidelines risk being denied.

Managed care primer

Understanding how managed care works can help you develop more positive interactions with these systems. Managed care exists to help control medical costs. Restricting services is one method of medical cost control, but employers and government payers also are interested in improving disease prevention, recognition, and management.

Delivering health benefits. The process begins when a business or government entity develops a summary plan description (SPD) (Box 1), defining what medical and mental health care services a policy covers (Figure).

A managed care company—typically a health maintenance organization (HMO) or similar entity—enters into a contract to implement and manage health care benefits for all persons covered by the plan. Because of their complexity, mental health services are usually “carved out” (Box 2)4 to a mental health specialty managed care company.

Utilization review. Whenever you deliver mental health care, your claims and treatment plans are scrutinized through utilization review (UR). Before authorizing payment, reviewers typically screen claims to:

- verify that the patient’s benefit plan covers the service

- establish the service’s medical necessity

- ensure that the treatment meets accepted standards of care.

UR staff in most managed care companies have administrative authority to authorize care, but care can be denied only by a medical director—typically a psychiatrist who reviews the clinical information submitted by the provider.

Figure Model of a typical managed care plan

Example 1

Claim authorization. A psychiatrist evaluates a patient and diagnoses major depression. The psychiatrist submits a treatment plan to the managed care company requesting authorization for 6 medication management and 10 psychotherapy sessions for the next 12 months. A UR representative reviews the plan, verifies the patient has appropriate coverage, and authorizes the sessions.

Example 2

Claim denial. A psychiatrist evaluates a patient and diagnoses major depression. The psychiatrist submits a treatment plan to the managed care company, requesting authorization for 10 EEG biofeedback sessions to treat the depression. A UR representative examines the plan and asks the medical director to review it. The medical director denies authorization because EEG biofeedback does not meet accepted standards for depression treatment.

Negotiating exceptions. Managed care companies must follow the letter of the benefits they administer. Some employers, however, allow for a “benefit exception” when practitioners identify patient services not covered under the benefit that, if implemented, might improve care and reduce costs.

If you encounter a situation where you believe plan limitations might adversely affect patient outcome and expense, point it out to the managed care company and ask if the patient’s plan allows benefit exceptions. Some plans do not allow for partial hospitalization, for example. If a patient with frequent inpatient admissions could be cared for in the less-intensive environment of a partial hospital program, the managed care case manager might approach the employer and suggest a benefit exception for this patient.

Common reasons claims are denied

Coverage limitations. Insurance plans often exclude or restrict particular services and limit certain types of care such as chemical dependency treatment or psychological testing. Managed care companies do not write the plans they manage and cannot authorize care that the benefit does not cover.

In “carve-out” plans, HMOs and insurance companies that do not have in-house expertise in mental health care or chemical dependency treatment “carve out” these services so that coverage is managed separately from the medical benefit. Carved-out services typically are delivered exclusively by designated providers or groups that contract with the HMO to provide mental health care to members.

Carve-outs have led to concerns about parity, particularly when mental health benefits are reduced or restricted compared with other medical benefits in the plan.

In a “carve-in” plan, mental health care remains within the overall health care coverage, which can facilitate collaboration between mental health and medical care providers. Parity for mental health care may be less of an issue than with “carve-out” plans, but “carve-in” plans might not be equipped to adequately meet the needs of patients with serious, persistent mental illness.4

Recommendation. Make sure you and your patients understand their benefit limitations. All employees with health insurance receive a summary plan description (SPD), which outlines benefit coverage and limitations. Encourage patients to read this document and contact their managed care companies with questions about coverage. Also ensure that your office managers:

- become familiar with SPDs for commonly encountered plans in your practice

- proactively verify patient benefit coverage.

Medical necessity. Practitioners in inpatient or residential settings experience the highest rates of denials of requested care on grounds that care is not medically necessary. Managed care company guidelines specify criteria that must be met—such as active suicidality, disorganized thinking, or significant medical co-morbidity—before care can be authorized.

Recommendation. Document specifically and concisely in daily notes why a patient requires the care you are providing. Managed care company guidelines are only guidelines; when the patient does not meet criteria, the medical director is more likely to authorize care if you clearly state the rationale for that level of care.

Patient is not progressing. Medical and mental health care is expected to provide a therapeutic outcome. When little progress is being made toward treatment goals, managed care companies have an obligation to the payers they represent to ensure that patients receive effective care.

Recommendation. Set realistic goals in the treatment plan. If a patient has a chronic condition and is not expected to improve but requires ongoing care to maintain function, state this in the treatment plan. If a patient is not making progress toward treatment goals, explain the reason and how you are addressing it.

No prior authorization. Some services—such as psychometric testing, inpatient care, or residential treatment—require prior authorization for reimbursement. Particularly for expensive treatments, payers require prior authorization so that utilization review occurs while care is being delivered, as opposed to afterward when costs are more difficult to contain.

Recommendation. Be familiar with prior authorization policies of common plans in your practice. If you discover you have provided care that required prior authorization, make a good-faith effort to submit clinical notes and explain why you did not request prior authorization. Many managed care companies will authorize payment after the fact if care was necessary and reasonable.

Duplication of services. Psychiatric patients often move from practice to practice, sometimes several times a year, without telling clinicians. Thus, laboratory testing, psychometric testing, and other diagnostic services may be repeated. Managed care companies take the stance that duplication of services is expensive and unnecessary, whereas you may argue that you must have adequate information to care for patients appropriately.

Recommendation. When assessing new patients, make it a priority for your office staff to ask patients about care they have received in the last year and obtain records from other providers. If you duplicate services, explain in your treatment plan why it was necessary for your patient’s care.

Interacting with managed care

Unfortunately, clinicians and managed care company representatives often view their relationship as adversarial (Box 3). Yes, some managed care representatives unfairly limit mental health care, and some clinicians maximize income potential by overbilling or providing unnecessary care. In our experience, however, most people on both sides of the equation are doing their jobs fairly and reasonably.

Medical care is expensive. Managed care’s role is not to deny care to patients who need it but to help the fiduciaries they represent—private companies or government entities—ensure that appropriate and economically responsible care is delivered. When you interact with managed care companies, keep 3 principles in mind:

Use common courtesy. Standing up for your patients and practice is reasonable and appropriate. At the same time, treating managed care representatives respectfully and professionally will go a long way as you advocate for your patients.

Document clearly and concisely. Documenting your impressions, goals, and care plans succinctly and well in your notes will save you and the managed care company time, frustration, and dollars. Managed care representatives do not want to review illegible, poorly organized, or overly inclusive documentation.

Some practitioners choose to practice outside of managed care networks—such as in fee for service—thus freeing themselves from guidelines and care limitations associated with managed care. Most health plans permit patients to seek treatment from out-of-network practitioners, although usually with higher out-of-pocket expenses.

Out-of-network practitioners who submit claims to managed care companies must follow many of the in-network rules, such as establishing medical necessity, submitting treatment plans, and undergoing utilization review.

Advantages of being an out-of-network provider—especially in a fee-for-service model—include practice independence, freedom from managed care paperwork, and the possibility of increased revenue by not having to accept reimbursement rates set by managed care contracts.

Disadvantages include potentially seeing fewer patients because of higher out-of-network costs, excluding lower-income patients, and receiving fewer referrals from managed care companies.

Out-of-network practitioners also have not gone through managed care companies’ credentialing, a process that assures patients that network practitioners are licensed and have not had serious quality-of-care or malpractice events that might adversely affect patient care.

Denials take managed care representatives more time than approvals. These busy people often look for reasons to approve reasonable care rather than to deny unreasonable care. If your documentation is clear and practice patterns are sound, your inpatient and outpatient treatment plans are much more likely to avoid the harsh scrutiny of the authorization denial process.

Managed care companies rely on the information you provide. The most common reason for denials being reversed on appeal is that additional information unavailable to the company at the initial review has been provided in the appeals process.

Learn from denials. Whenever you are issued a care denial, find out why. If a pattern emerges, you might need to change your practice or accept that certain types of care will not be covered routinely. For example, you might obtain psychological testing for every patient, whereas many managed care companies authorize testing only in specific circumstances. Thus, you could:

- modify use of testing

- or accept that this practice will not always be reimbursed.

Wellness and prevention programs

Managed care plays an important role in developing and implementing wellness, disease prevention, and disease management programs for employers and government entities. These patient programs reduce health care costs, decrease time away from work (absenteeism), and improve productivity (“presentee-ism”).5,6 Benefit plans often provide free programs and offer financial incentives for patients’ participation.

Health risk assessments, life-style coaching, and condition-specific management programs—such as for diabetes care, smoking cessation, or depression treatment—are becoming common in employee benefit packages. These programs try to improve patients’ health through care coordination with the patients’ health care providers.

As programs are developed, you can expect to regularly receive clinical information about your patients from managed care case managers who are trying to integrate their programs with your patients’ care. Case managers’ goal is to improve clinical outcomes through initiatives such as treatment adherence, patient education, and early detection of treatment resistance or symptom relapse. To take advantage of these resources, be aware of available programs and consider referring patients into them.

Related resources

- Fauman MA. Negotiating managed care: a manual for clinicians. Washington, D.C.: American Psychiatric Publishing; 2002.

- Tuckfelt S, Fink J, Prince Warren M. The psychotherapist’s guide to managed care in the 21st century. Northvale, NJ: Jason Aronson; 1997.

Disclosure

Dr. Sutor is a practicing psychiatrist at the Mayo Clinic, Rochester, MN, and has been assistant medical director for behavioral health at MMSI (the Mayo Clinic’s managed care entity) since 2001.

1. Landon BE, Reschovsky J, Blumenthal D. Changes in career satisfaction among primary care and specialist physicians, 1997-2001. JAMA 2003;289:442-9.

2. Iglehart JK. Health policy report: managed care and mental health. N Engl J Med 1996;334(2):131-5.

3. Wells LA. Psychiatry, managed care, and crooked thinking. Mayo Clin Proc 1998;73(5):483-7.

4. Bartels SJ, Levine KJ, Shea D. Community-based long-term care for older patients with severe and persistent mental illness in the era of managed care. Psychiatr Serv 1999;50:1189-97.

5. Rost K, Smith JL, Dickinson M. The effect of improving primary care depression management on employee absenteeism and productivity. A randomized trial. Medical Care 2004;42(12):1202-10.

6. Keitner GI, Ryan CE, Solomon DA. Realistic expectations and a disease management model for depressed patients with persistent symptoms. J Clin Psychiatry 2006;67(9):1412-21.

1. Landon BE, Reschovsky J, Blumenthal D. Changes in career satisfaction among primary care and specialist physicians, 1997-2001. JAMA 2003;289:442-9.

2. Iglehart JK. Health policy report: managed care and mental health. N Engl J Med 1996;334(2):131-5.

3. Wells LA. Psychiatry, managed care, and crooked thinking. Mayo Clin Proc 1998;73(5):483-7.

4. Bartels SJ, Levine KJ, Shea D. Community-based long-term care for older patients with severe and persistent mental illness in the era of managed care. Psychiatr Serv 1999;50:1189-97.

5. Rost K, Smith JL, Dickinson M. The effect of improving primary care depression management on employee absenteeism and productivity. A randomized trial. Medical Care 2004;42(12):1202-10.

6. Keitner GI, Ryan CE, Solomon DA. Realistic expectations and a disease management model for depressed patients with persistent symptoms. J Clin Psychiatry 2006;67(9):1412-21.

Get creative to manage dementia-related behaviors

Mrs. A, age 82, has advanced Alzheimer’s disease and has resided in a nursing home for 2 years. She does not recognize that she lives in a nursing home and waits by the door for her son to take her home. She spends her days weeping, telling visitors and staff she has been abandoned and must go home to care for her children.

Recently she has been wandering from the facility. When staff attempt to direct her away from the door, she resists, becomes physically aggressive, and hollers loudly. Her behavior bothers visitors and other patients, who frequently complain.

Her primary care physician prescribes a trial of olanzapine, 10 mg/d, but she becomes confused and suffers a fall. Staff report that Mrs. A is sleeping poorly and losing weight.

Deciding how to manage agitation, aggression, or psychotic symptoms of dementia is dicey at best. You can try an atypical antipsychotic despite the FDA’s black-box warning (Risks of using vs. not using atypical antipsychotics. Current Psychiatry 2005;4(8):14-28.

- Carbamazepine • Carbatrol

- Donepezil • Aricept

- Lorazepam • Ativan

- Memantine • Namenda

- Mirtazapine • Remeron

- Olanzapine • Zyprexa

- Oxazepam • Serax

- Trazodone • Desyrel

- Valproic acid • Depakote

The authors report no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. Alexopoulos GS, Jeste DV, Chung H, et al. The expert consensus guideline series: Treatment of dementia and its behavioral disturbances. Minneapolis, MN: McGraw-Hill; 2005.

2. Schneider LS, Dagerman LS, Insel P. Risk of death with atypical antipsychotic drug treatment for dementia: Meta-analysis of randomized placebo-controlled trials. JAMA 2005;294:1934-43.

3. FDA Talk Paper. FDA issues public health advisory for antipsychotic drugs used for treatment of behavioral disorders in elderly patients. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Available at: http://www.fda.gov/bbs/topics/ANSWERS/2005/ANS01350.html. Accessed March 10, 2006.

4. Treatment of agitation in older persons with dementia. The Expert Consensus Panel for Agitation in Dementia. Postgrad Med 1998;SPEC NO:1-88.

5. Sutor B, Rummans TA, Smith GE. Assessment and management of behavioral disturbances in nursing home patients with dementia. Mayo Clin Proc 2001;76:540-50.

6. McKeith IG, Dickson DW, Lowe J, et al. Diagnosis and management of dementia in Lewy bodies: Third report of the DLB consortium. Neurology 2005;65:1863-72.

7. Feldman H, Lyketsos LD, Steinberg QM, et al. A 24-week, randomized, double-blind study of donepezil in moderate to severe Alzheimer’s disease. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2003;60:737-46.

8. Sink KM, Holden KF, Yaffe K. Pharmacologic treatment of neuropsychiatric symptoms of dementia: A review of the evidence. JAMA 2005;293:596-608.

9. Gauthier S, Wirth Y, Mobius HJ. Effects of memantine on behavioral symptoms in Alzheimer’s disease patients: An analysis of the Neuropsychiatric Inventory (NPI) data of two randomized controlled studies. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 2005;20:259-62.

10. Porsteinsson AP, Tariot PN, Jakimovich LJ, et al. Valproate therapy for agitation in dementia: Open-label extension of a double-blind trial. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 2003;11:434-40.

11. Tariot PN, Raman R, Jakimovich L, et al. Divalproex sodium in nursing home residents with possible or probable Alzheimer’s disease complicated by agitation: A randomized controlled trial. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 2005;13:942-9.

Mrs. A, age 82, has advanced Alzheimer’s disease and has resided in a nursing home for 2 years. She does not recognize that she lives in a nursing home and waits by the door for her son to take her home. She spends her days weeping, telling visitors and staff she has been abandoned and must go home to care for her children.

Recently she has been wandering from the facility. When staff attempt to direct her away from the door, she resists, becomes physically aggressive, and hollers loudly. Her behavior bothers visitors and other patients, who frequently complain.

Her primary care physician prescribes a trial of olanzapine, 10 mg/d, but she becomes confused and suffers a fall. Staff report that Mrs. A is sleeping poorly and losing weight.

Deciding how to manage agitation, aggression, or psychotic symptoms of dementia is dicey at best. You can try an atypical antipsychotic despite the FDA’s black-box warning (Risks of using vs. not using atypical antipsychotics. Current Psychiatry 2005;4(8):14-28.

- Carbamazepine • Carbatrol

- Donepezil • Aricept

- Lorazepam • Ativan

- Memantine • Namenda

- Mirtazapine • Remeron

- Olanzapine • Zyprexa

- Oxazepam • Serax

- Trazodone • Desyrel

- Valproic acid • Depakote

The authors report no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

Mrs. A, age 82, has advanced Alzheimer’s disease and has resided in a nursing home for 2 years. She does not recognize that she lives in a nursing home and waits by the door for her son to take her home. She spends her days weeping, telling visitors and staff she has been abandoned and must go home to care for her children.

Recently she has been wandering from the facility. When staff attempt to direct her away from the door, she resists, becomes physically aggressive, and hollers loudly. Her behavior bothers visitors and other patients, who frequently complain.

Her primary care physician prescribes a trial of olanzapine, 10 mg/d, but she becomes confused and suffers a fall. Staff report that Mrs. A is sleeping poorly and losing weight.

Deciding how to manage agitation, aggression, or psychotic symptoms of dementia is dicey at best. You can try an atypical antipsychotic despite the FDA’s black-box warning (Risks of using vs. not using atypical antipsychotics. Current Psychiatry 2005;4(8):14-28.

- Carbamazepine • Carbatrol

- Donepezil • Aricept

- Lorazepam • Ativan

- Memantine • Namenda

- Mirtazapine • Remeron

- Olanzapine • Zyprexa

- Oxazepam • Serax

- Trazodone • Desyrel

- Valproic acid • Depakote

The authors report no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. Alexopoulos GS, Jeste DV, Chung H, et al. The expert consensus guideline series: Treatment of dementia and its behavioral disturbances. Minneapolis, MN: McGraw-Hill; 2005.

2. Schneider LS, Dagerman LS, Insel P. Risk of death with atypical antipsychotic drug treatment for dementia: Meta-analysis of randomized placebo-controlled trials. JAMA 2005;294:1934-43.

3. FDA Talk Paper. FDA issues public health advisory for antipsychotic drugs used for treatment of behavioral disorders in elderly patients. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Available at: http://www.fda.gov/bbs/topics/ANSWERS/2005/ANS01350.html. Accessed March 10, 2006.

4. Treatment of agitation in older persons with dementia. The Expert Consensus Panel for Agitation in Dementia. Postgrad Med 1998;SPEC NO:1-88.

5. Sutor B, Rummans TA, Smith GE. Assessment and management of behavioral disturbances in nursing home patients with dementia. Mayo Clin Proc 2001;76:540-50.

6. McKeith IG, Dickson DW, Lowe J, et al. Diagnosis and management of dementia in Lewy bodies: Third report of the DLB consortium. Neurology 2005;65:1863-72.

7. Feldman H, Lyketsos LD, Steinberg QM, et al. A 24-week, randomized, double-blind study of donepezil in moderate to severe Alzheimer’s disease. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2003;60:737-46.

8. Sink KM, Holden KF, Yaffe K. Pharmacologic treatment of neuropsychiatric symptoms of dementia: A review of the evidence. JAMA 2005;293:596-608.

9. Gauthier S, Wirth Y, Mobius HJ. Effects of memantine on behavioral symptoms in Alzheimer’s disease patients: An analysis of the Neuropsychiatric Inventory (NPI) data of two randomized controlled studies. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 2005;20:259-62.

10. Porsteinsson AP, Tariot PN, Jakimovich LJ, et al. Valproate therapy for agitation in dementia: Open-label extension of a double-blind trial. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 2003;11:434-40.

11. Tariot PN, Raman R, Jakimovich L, et al. Divalproex sodium in nursing home residents with possible or probable Alzheimer’s disease complicated by agitation: A randomized controlled trial. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 2005;13:942-9.

1. Alexopoulos GS, Jeste DV, Chung H, et al. The expert consensus guideline series: Treatment of dementia and its behavioral disturbances. Minneapolis, MN: McGraw-Hill; 2005.

2. Schneider LS, Dagerman LS, Insel P. Risk of death with atypical antipsychotic drug treatment for dementia: Meta-analysis of randomized placebo-controlled trials. JAMA 2005;294:1934-43.

3. FDA Talk Paper. FDA issues public health advisory for antipsychotic drugs used for treatment of behavioral disorders in elderly patients. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Available at: http://www.fda.gov/bbs/topics/ANSWERS/2005/ANS01350.html. Accessed March 10, 2006.

4. Treatment of agitation in older persons with dementia. The Expert Consensus Panel for Agitation in Dementia. Postgrad Med 1998;SPEC NO:1-88.

5. Sutor B, Rummans TA, Smith GE. Assessment and management of behavioral disturbances in nursing home patients with dementia. Mayo Clin Proc 2001;76:540-50.

6. McKeith IG, Dickson DW, Lowe J, et al. Diagnosis and management of dementia in Lewy bodies: Third report of the DLB consortium. Neurology 2005;65:1863-72.

7. Feldman H, Lyketsos LD, Steinberg QM, et al. A 24-week, randomized, double-blind study of donepezil in moderate to severe Alzheimer’s disease. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2003;60:737-46.

8. Sink KM, Holden KF, Yaffe K. Pharmacologic treatment of neuropsychiatric symptoms of dementia: A review of the evidence. JAMA 2005;293:596-608.

9. Gauthier S, Wirth Y, Mobius HJ. Effects of memantine on behavioral symptoms in Alzheimer’s disease patients: An analysis of the Neuropsychiatric Inventory (NPI) data of two randomized controlled studies. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 2005;20:259-62.

10. Porsteinsson AP, Tariot PN, Jakimovich LJ, et al. Valproate therapy for agitation in dementia: Open-label extension of a double-blind trial. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 2003;11:434-40.

11. Tariot PN, Raman R, Jakimovich L, et al. Divalproex sodium in nursing home residents with possible or probable Alzheimer’s disease complicated by agitation: A randomized controlled trial. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 2005;13:942-9.