User login

Brendon Shank joined the Society of Hospital Medicine in February 2011 and serves as Associate Vice President of Communications. He is responsible for maintaining a dialogue between SHM and its many audiences, including members, media and others in healthcare.

Healthcare Trailblazers

Younger generations blaze new paths through the American economy. Fifteen years ago, Generation X was fresh out of college and flush with the unimagined potential of the Internet. They helped change the way the world shared information and conducted business. The impact of such innovation and enthusiasm for new technology is still felt today.

The healthcare sector possesses pioneers of its own, many with the same kind of drive and vision as the dot-com entrepreneurs of the 1990s. Fifteen years from now, today’s young hospitalists—shaped by ever-changing demands and healthcare hurdles—will be recognized as an authority in the new ways patient care is delivered.

—Brian Markoff, MD, FHM, associate professor of medicine, Mount Sinai Hospitalist Group, New York City

Bijo Chacko, MD, FHM, former chair of SHM’s Young Physicians Committee, sees energy in the newest generation of hospitalists. He also sees great potential from residents who are finishing their training and considering their job options. Until recently, SHM’s Young Physicians Committee operated as a task force. The group’s growth and increased young-physician representation throughout the society prompted SHM leadership to promote the task force to full committee status.

“The wonderful thing is that we have received lots of input from around the country and dramatically increased membership in the past few years,” says Dr. Chacko, hospital medicine medical director for Preferred Health Partners in New York City. “We have moved from simply gathering information about young physicians in hospital medicine to actively disseminating it, including the new Resident’s Corner [department in The Hospitalist]. It addresses the needs of residents and introduces them to the nuances and specifics of hospital medicine.”

The demand for information has spurred the launch of a young physicians section (www.hospitalmedicine.org/youngdoctor) on SHM’s Web site. Combined with SHM’s online career center (www.hospitalmedicine.org/careercenter), the new microsites provide young physicians a broad range of information about the specialty and—most importantly—HM career options.

Natural Progression

Four out of five large hospitals now use hospitalists, and as more hospitals implement HM programs, more residents will be exposed to the hospitalist model of care. For residents, the allure of an HM career is broad and deep. In many ways, HM is the logical extension of residency training. Brian Markoff, MD, FHM, a hospitalist and associate professor of medicine at Mount Sinai Hospitalist Group in New York City, was a chief resident when he founded the hospitalist program at the University of California at Davis Health System in Sacramento in 1998.

“Creating the hospitalist program at UC-Davis was pretty easy,” Dr. Markoff says. “All of the program’s founders were chief residents at the time. The people involved were warm to the idea, and we could teach without being in the fellowship program. Residents are already very comfortable treating patients in the hospital setting.”

Dr. Markoff says practicing hospitalists are a positive influence on residents who are still undecided on a career path. “If you’re a good role model, they’ll be interested in hospital medicine,” he says.

Diversity of Patients, Issues, Settings

Dr. Markoff and others caution that HM encompasses more than an expansion of a resident’s standard roles and responsibilities. “We’re not just super-residents,” he says. “We’re highly trained specialists in the care of hospitalized patients and the process of making care in hospital better.”

Medical conditions, patient issues, and administrative situations that often are outside a resident’s scope quickly come into focus for a new hospitalist. When Mona Patel, DO, associate director of hospitalist services at Staten Island University Hospital in New York, chose an HM career five years ago, the diversity in opportunities was a major draw. Like many hospitalists, she knew she would enjoy the type of care she provides to patients.

“I liked the acuity of the patients and disease processes; it was much more interesting and exciting for me than ongoing outpatient care of chronic diseases,” Dr. Patel says. “I liked the interaction with the hospital house staff and lots of consultants. If I had questions about a patient, I could easily consult with a specialist within the hospital.”

In addition to providing bedside care, new hospitalists often find themselves at the forefront of a monumental change in how healthcare is provided nationwide. Quality improvement (QI) initiatives, such as reducing preventable diseases in the hospital and reducing readmission rates, attracted Bryan Huang, MD, to hospital medicine at the University of California at San Diego.

“When I interviewed at UCSD, I was very interested in quality improvement,” says Dr. Huang, an assistant clinical professor at UCSD’s Division of Hospital Medicine. “UCSD is well known for glycemic control and VTE prophylaxis. We’re now working on quality improvement for treating delirium and hospital discharge.”

His experience as an academic hospitalist has opened up the QI world to him. “Before this job, I was almost not familiar at all with quality improvement,” Dr. Huang says. “As a resident, I did some quality-improvement work, but not much. Quality improvement was missing from residency training, but it’s getting better.”

Dr. Patel says HM’s biggest selling point is the variety of settings available to a new hospitalist. She’s been working for the past two years in an academic hospital program in a community hospital setting with 20 hospitalists. Before that, she worked in private practice as a hospitalist. Now, when she talks with residents, she talks about their options.

“It’s really important that you figure out what kind of setting you want,” Dr. Patel says. “Hospital medicine has a diversity of settings, from a small community hospital where you do a broad range of inpatient care to a larger academic teaching environment or a private practice group.”

Leadership Opportunities

The continuing demand for hospitalists affords young physicians who are considering an HM career additional freedom in the job market. In comparison to more traditional primary-care models, hospitalist jobs offer flexible hours and competitive salaries.

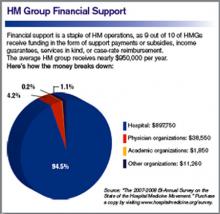

Dr. Chacko points to another benefit that is a direct result of the high demand for hospitalists: increased opportunities to launch management careers. The average age of a hospitalist is 37 and the average age of an HM group leader is 41, according to SHM’s 2007-2008 Bi-Annual Survey on the State of the Hospital Medicine Movement.

“That’s not that much of a difference,” Dr. Chacko says. “Early-career hospitalists find ample leadership opportunities in the specialty. There are lots of opportunities for young hospitalists.”

How to Get Started

Because most teaching hospitals have hospitalists, most residents are exposed to HM. Many hospitalists relish the opportunity to mentor and provide early-career counseling. “Sometimes, a resident will ask to grab coffee and learn more about hospital medicine,” Dr. Huang says. “I tell them what my job is like. Many ask, ‘How do I get started looking for a job?’ I tell them that connections really help. Word of mouth is very important, so I refer people to other people.”

Margaret Fang, MD, MPH, FHM, assistant professor of medicine at the University of California at San Francisco’s division of hospital medicine and a founding member of the Young Physicians Committee, recommends that residents begin with a vision and work backward. “On a broad level, if you’re a resident, you should think about where you want to be in five years,” she says. “Look around your hospital and find a few people whose job you want.”

For some young physicians, looking ahead five years could mean being part of the healthcare revolution of tomorrow. TH

Brendon Shank is a freelance writer based in Philadelphia.

SHM elects board members

SHM has elected three new members to its Board of Directors and re-elected two members. Board members are nominated and elected by the membership and serve a three-year term.The newly elected members of the board are:

Re-elected board members:

Younger generations blaze new paths through the American economy. Fifteen years ago, Generation X was fresh out of college and flush with the unimagined potential of the Internet. They helped change the way the world shared information and conducted business. The impact of such innovation and enthusiasm for new technology is still felt today.

The healthcare sector possesses pioneers of its own, many with the same kind of drive and vision as the dot-com entrepreneurs of the 1990s. Fifteen years from now, today’s young hospitalists—shaped by ever-changing demands and healthcare hurdles—will be recognized as an authority in the new ways patient care is delivered.

—Brian Markoff, MD, FHM, associate professor of medicine, Mount Sinai Hospitalist Group, New York City

Bijo Chacko, MD, FHM, former chair of SHM’s Young Physicians Committee, sees energy in the newest generation of hospitalists. He also sees great potential from residents who are finishing their training and considering their job options. Until recently, SHM’s Young Physicians Committee operated as a task force. The group’s growth and increased young-physician representation throughout the society prompted SHM leadership to promote the task force to full committee status.

“The wonderful thing is that we have received lots of input from around the country and dramatically increased membership in the past few years,” says Dr. Chacko, hospital medicine medical director for Preferred Health Partners in New York City. “We have moved from simply gathering information about young physicians in hospital medicine to actively disseminating it, including the new Resident’s Corner [department in The Hospitalist]. It addresses the needs of residents and introduces them to the nuances and specifics of hospital medicine.”

The demand for information has spurred the launch of a young physicians section (www.hospitalmedicine.org/youngdoctor) on SHM’s Web site. Combined with SHM’s online career center (www.hospitalmedicine.org/careercenter), the new microsites provide young physicians a broad range of information about the specialty and—most importantly—HM career options.

Natural Progression

Four out of five large hospitals now use hospitalists, and as more hospitals implement HM programs, more residents will be exposed to the hospitalist model of care. For residents, the allure of an HM career is broad and deep. In many ways, HM is the logical extension of residency training. Brian Markoff, MD, FHM, a hospitalist and associate professor of medicine at Mount Sinai Hospitalist Group in New York City, was a chief resident when he founded the hospitalist program at the University of California at Davis Health System in Sacramento in 1998.

“Creating the hospitalist program at UC-Davis was pretty easy,” Dr. Markoff says. “All of the program’s founders were chief residents at the time. The people involved were warm to the idea, and we could teach without being in the fellowship program. Residents are already very comfortable treating patients in the hospital setting.”

Dr. Markoff says practicing hospitalists are a positive influence on residents who are still undecided on a career path. “If you’re a good role model, they’ll be interested in hospital medicine,” he says.

Diversity of Patients, Issues, Settings

Dr. Markoff and others caution that HM encompasses more than an expansion of a resident’s standard roles and responsibilities. “We’re not just super-residents,” he says. “We’re highly trained specialists in the care of hospitalized patients and the process of making care in hospital better.”

Medical conditions, patient issues, and administrative situations that often are outside a resident’s scope quickly come into focus for a new hospitalist. When Mona Patel, DO, associate director of hospitalist services at Staten Island University Hospital in New York, chose an HM career five years ago, the diversity in opportunities was a major draw. Like many hospitalists, she knew she would enjoy the type of care she provides to patients.

“I liked the acuity of the patients and disease processes; it was much more interesting and exciting for me than ongoing outpatient care of chronic diseases,” Dr. Patel says. “I liked the interaction with the hospital house staff and lots of consultants. If I had questions about a patient, I could easily consult with a specialist within the hospital.”

In addition to providing bedside care, new hospitalists often find themselves at the forefront of a monumental change in how healthcare is provided nationwide. Quality improvement (QI) initiatives, such as reducing preventable diseases in the hospital and reducing readmission rates, attracted Bryan Huang, MD, to hospital medicine at the University of California at San Diego.

“When I interviewed at UCSD, I was very interested in quality improvement,” says Dr. Huang, an assistant clinical professor at UCSD’s Division of Hospital Medicine. “UCSD is well known for glycemic control and VTE prophylaxis. We’re now working on quality improvement for treating delirium and hospital discharge.”

His experience as an academic hospitalist has opened up the QI world to him. “Before this job, I was almost not familiar at all with quality improvement,” Dr. Huang says. “As a resident, I did some quality-improvement work, but not much. Quality improvement was missing from residency training, but it’s getting better.”

Dr. Patel says HM’s biggest selling point is the variety of settings available to a new hospitalist. She’s been working for the past two years in an academic hospital program in a community hospital setting with 20 hospitalists. Before that, she worked in private practice as a hospitalist. Now, when she talks with residents, she talks about their options.

“It’s really important that you figure out what kind of setting you want,” Dr. Patel says. “Hospital medicine has a diversity of settings, from a small community hospital where you do a broad range of inpatient care to a larger academic teaching environment or a private practice group.”

Leadership Opportunities

The continuing demand for hospitalists affords young physicians who are considering an HM career additional freedom in the job market. In comparison to more traditional primary-care models, hospitalist jobs offer flexible hours and competitive salaries.

Dr. Chacko points to another benefit that is a direct result of the high demand for hospitalists: increased opportunities to launch management careers. The average age of a hospitalist is 37 and the average age of an HM group leader is 41, according to SHM’s 2007-2008 Bi-Annual Survey on the State of the Hospital Medicine Movement.

“That’s not that much of a difference,” Dr. Chacko says. “Early-career hospitalists find ample leadership opportunities in the specialty. There are lots of opportunities for young hospitalists.”

How to Get Started

Because most teaching hospitals have hospitalists, most residents are exposed to HM. Many hospitalists relish the opportunity to mentor and provide early-career counseling. “Sometimes, a resident will ask to grab coffee and learn more about hospital medicine,” Dr. Huang says. “I tell them what my job is like. Many ask, ‘How do I get started looking for a job?’ I tell them that connections really help. Word of mouth is very important, so I refer people to other people.”

Margaret Fang, MD, MPH, FHM, assistant professor of medicine at the University of California at San Francisco’s division of hospital medicine and a founding member of the Young Physicians Committee, recommends that residents begin with a vision and work backward. “On a broad level, if you’re a resident, you should think about where you want to be in five years,” she says. “Look around your hospital and find a few people whose job you want.”

For some young physicians, looking ahead five years could mean being part of the healthcare revolution of tomorrow. TH

Brendon Shank is a freelance writer based in Philadelphia.

SHM elects board members

SHM has elected three new members to its Board of Directors and re-elected two members. Board members are nominated and elected by the membership and serve a three-year term.The newly elected members of the board are:

Re-elected board members:

Younger generations blaze new paths through the American economy. Fifteen years ago, Generation X was fresh out of college and flush with the unimagined potential of the Internet. They helped change the way the world shared information and conducted business. The impact of such innovation and enthusiasm for new technology is still felt today.

The healthcare sector possesses pioneers of its own, many with the same kind of drive and vision as the dot-com entrepreneurs of the 1990s. Fifteen years from now, today’s young hospitalists—shaped by ever-changing demands and healthcare hurdles—will be recognized as an authority in the new ways patient care is delivered.

—Brian Markoff, MD, FHM, associate professor of medicine, Mount Sinai Hospitalist Group, New York City

Bijo Chacko, MD, FHM, former chair of SHM’s Young Physicians Committee, sees energy in the newest generation of hospitalists. He also sees great potential from residents who are finishing their training and considering their job options. Until recently, SHM’s Young Physicians Committee operated as a task force. The group’s growth and increased young-physician representation throughout the society prompted SHM leadership to promote the task force to full committee status.

“The wonderful thing is that we have received lots of input from around the country and dramatically increased membership in the past few years,” says Dr. Chacko, hospital medicine medical director for Preferred Health Partners in New York City. “We have moved from simply gathering information about young physicians in hospital medicine to actively disseminating it, including the new Resident’s Corner [department in The Hospitalist]. It addresses the needs of residents and introduces them to the nuances and specifics of hospital medicine.”

The demand for information has spurred the launch of a young physicians section (www.hospitalmedicine.org/youngdoctor) on SHM’s Web site. Combined with SHM’s online career center (www.hospitalmedicine.org/careercenter), the new microsites provide young physicians a broad range of information about the specialty and—most importantly—HM career options.

Natural Progression

Four out of five large hospitals now use hospitalists, and as more hospitals implement HM programs, more residents will be exposed to the hospitalist model of care. For residents, the allure of an HM career is broad and deep. In many ways, HM is the logical extension of residency training. Brian Markoff, MD, FHM, a hospitalist and associate professor of medicine at Mount Sinai Hospitalist Group in New York City, was a chief resident when he founded the hospitalist program at the University of California at Davis Health System in Sacramento in 1998.

“Creating the hospitalist program at UC-Davis was pretty easy,” Dr. Markoff says. “All of the program’s founders were chief residents at the time. The people involved were warm to the idea, and we could teach without being in the fellowship program. Residents are already very comfortable treating patients in the hospital setting.”

Dr. Markoff says practicing hospitalists are a positive influence on residents who are still undecided on a career path. “If you’re a good role model, they’ll be interested in hospital medicine,” he says.

Diversity of Patients, Issues, Settings

Dr. Markoff and others caution that HM encompasses more than an expansion of a resident’s standard roles and responsibilities. “We’re not just super-residents,” he says. “We’re highly trained specialists in the care of hospitalized patients and the process of making care in hospital better.”

Medical conditions, patient issues, and administrative situations that often are outside a resident’s scope quickly come into focus for a new hospitalist. When Mona Patel, DO, associate director of hospitalist services at Staten Island University Hospital in New York, chose an HM career five years ago, the diversity in opportunities was a major draw. Like many hospitalists, she knew she would enjoy the type of care she provides to patients.

“I liked the acuity of the patients and disease processes; it was much more interesting and exciting for me than ongoing outpatient care of chronic diseases,” Dr. Patel says. “I liked the interaction with the hospital house staff and lots of consultants. If I had questions about a patient, I could easily consult with a specialist within the hospital.”

In addition to providing bedside care, new hospitalists often find themselves at the forefront of a monumental change in how healthcare is provided nationwide. Quality improvement (QI) initiatives, such as reducing preventable diseases in the hospital and reducing readmission rates, attracted Bryan Huang, MD, to hospital medicine at the University of California at San Diego.

“When I interviewed at UCSD, I was very interested in quality improvement,” says Dr. Huang, an assistant clinical professor at UCSD’s Division of Hospital Medicine. “UCSD is well known for glycemic control and VTE prophylaxis. We’re now working on quality improvement for treating delirium and hospital discharge.”

His experience as an academic hospitalist has opened up the QI world to him. “Before this job, I was almost not familiar at all with quality improvement,” Dr. Huang says. “As a resident, I did some quality-improvement work, but not much. Quality improvement was missing from residency training, but it’s getting better.”

Dr. Patel says HM’s biggest selling point is the variety of settings available to a new hospitalist. She’s been working for the past two years in an academic hospital program in a community hospital setting with 20 hospitalists. Before that, she worked in private practice as a hospitalist. Now, when she talks with residents, she talks about their options.

“It’s really important that you figure out what kind of setting you want,” Dr. Patel says. “Hospital medicine has a diversity of settings, from a small community hospital where you do a broad range of inpatient care to a larger academic teaching environment or a private practice group.”

Leadership Opportunities

The continuing demand for hospitalists affords young physicians who are considering an HM career additional freedom in the job market. In comparison to more traditional primary-care models, hospitalist jobs offer flexible hours and competitive salaries.

Dr. Chacko points to another benefit that is a direct result of the high demand for hospitalists: increased opportunities to launch management careers. The average age of a hospitalist is 37 and the average age of an HM group leader is 41, according to SHM’s 2007-2008 Bi-Annual Survey on the State of the Hospital Medicine Movement.

“That’s not that much of a difference,” Dr. Chacko says. “Early-career hospitalists find ample leadership opportunities in the specialty. There are lots of opportunities for young hospitalists.”

How to Get Started

Because most teaching hospitals have hospitalists, most residents are exposed to HM. Many hospitalists relish the opportunity to mentor and provide early-career counseling. “Sometimes, a resident will ask to grab coffee and learn more about hospital medicine,” Dr. Huang says. “I tell them what my job is like. Many ask, ‘How do I get started looking for a job?’ I tell them that connections really help. Word of mouth is very important, so I refer people to other people.”

Margaret Fang, MD, MPH, FHM, assistant professor of medicine at the University of California at San Francisco’s division of hospital medicine and a founding member of the Young Physicians Committee, recommends that residents begin with a vision and work backward. “On a broad level, if you’re a resident, you should think about where you want to be in five years,” she says. “Look around your hospital and find a few people whose job you want.”

For some young physicians, looking ahead five years could mean being part of the healthcare revolution of tomorrow. TH

Brendon Shank is a freelance writer based in Philadelphia.

SHM elects board members

SHM has elected three new members to its Board of Directors and re-elected two members. Board members are nominated and elected by the membership and serve a three-year term.The newly elected members of the board are:

Re-elected board members:

Focused on the Practice

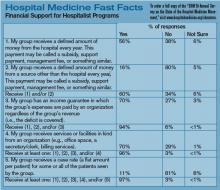

Most HM groups (HMGs) participate in quality initiatives in their hospitals, according to new SHM research. Moreover, 7 out of 10 HMGs participating in QI initiatives are leading those efforts at their hospitals.

The findings are part of SHM’s 2008-2009 Focused Survey, the latest in a series of reports commissioned by the Practice Analysis Committee. The survey and report concentrate on topics of interest from SHM’s comprehensive, biannual survey of its membership.

The survey compiled responses from 145 HMG leaders. In addition to QI initiatives, participants in the survey responded to a variety of questions, including quality-based incentives, hospitalist turnover, and the use of part-time hospitalists.

—Joe Miller, SHM’s executive advisor to the CEO

“This is certain to be a conversation starter for hospitalists, hospital executives, and others,” says Burke Kealey, MD, FHM, medical director for hospital medicine at St. Paul, Minn.-based HealthPartners and chair of SHM’s Practice Analysis Committee. “The Focused Survey is an opportunity for SHM to answer some of the pressing questions that healthcare executives and providers have about managing a hospitalist practice within the larger context of the hospital.”

Hospital executives and hospitalists use SHM survey findings to better understand what is going on in the specialty, says Joe Miller, SHM’s executive advisor to the CEO. “These surveys answer the kinds of questions that often come up when hospitalists and hospitals begin to evaluate their performance and plan for the future,” Miller says. “We use their questions as source material for this survey, so we can help them answer questions like, ‘How are most hospitalists participating in QI?’ or ‘How are other hospitalists using part-time staff members?’ ”

Hospitalists Lead the Way

Hospitalists continue to be at the forefront of QI initiatives within their hospitals, according to the latest survey. Almost all respondents (96.5%) reported that their HMG participated in QI programs; the average HMG has six hospitalists playing an active role in QI within the hospital.

The survey also found that 72.1% of respondents involved in QI activity reported that their hospitalists were “responsible for leading project(s)” on QI initiatives.

“The findings about the active role hospitalists play in QI initiatives may surprise even the most staunch advocate of QI within the hospital medicine specialty,” says Leslie Flores, MHA, SHM’s director of the Practice Management Institute and leader of the Focused Survey research. “In essence, it shows that nearly every hospitalist group is active in promoting QI, and that the vast majority of them are taking a leadership position to improve quality. … It is remarkable and extremely exciting that hospitalists are so deeply involved in QI in their organizations.”

The survey identified patient safety, clinical QI, and quality-related IT initiatives as most popular.

Quality Incentive Compensation

In order to track HMG quality incentive compensation, the 2008-2009 Focused Survey asked similar questions about the topic to questions in the 2006-2007 Focused Survey. Quality incentive compensation—paying bonuses or additional payments for meeting QI measures—not only increased markedly in the past two years, but a majority of HMGs also have adopted the practice. The number of HMGs that have quality incentive compensation plans has increased by 39% since 2006, according to the survey.

Nine out of 10 HMGs that receive performance-based compensation reported that the source of the compensation was the hospital or health system. In most cases, the compensation was paid to an individual hospitalist, which represents a shift from 2006, when more groups reported receiving the compensation directly.

The survey also shows that hospitals and HMGs use a number of process measures to evaluate QI incentives, including participation in quality or safety committees, transition of care measures, or core measures for heart failure, pneumonia, and acute myocardial infarction.

New Numbers Dispel High Turnover Myth

For years, the conventional wisdom throughout the healthcare community has been that HM suffers from a high turnover rate among its hospitalists. Focused Survey findings suggest otherwise. In fact, turnover rates for hospitalist groups have remained constant since 2005. Nearly a third (31.7%) of HMGs reported no turnover at all within the past 12 months.

“Getting an accurate idea about turnover in hospitalist groups has been an ongoing challenge in our research,” Flores says. “In this year’s Focused Survey, we provided clearer definitions and asked more specific questions to improve our measurement of turnover.”

The added specificity only served to reinforce findings from previous surveys that showed relatively low turnover rates. The most recent research revealed a 12.7% turnover rate, compared with 13% in 2007 and 12% in 2005.

The latest Focused Survey also includes detailed findings on turnover among full-time hospitalists compared with part-time hospitalists.

Part-Time vs. Full-Time

The new data challenge long-held assumptions about the role of part-time hospitalists. The survey queried HMGs about full-time and part-time hospitalist staff, and the proportion of time that each employee covers in the hospital.

Although there isn’t a consensus about what constitutes a full-time hospitalist, it is clear that they cover the vast majority (85%) of HMG staff hours. Part-time hospitalists are responsible for 10% of hospitalist staff hours, and “casual” hospitalists—temporary hospitalists or moonlighters—make up the remaining 5%.

Part-time hospitalists share the same responsibilities as their full-time colleagues, according to the report. More than 70% of HMG leaders said their part-time staff is deployed to cover the same shifts and responsibilities as full-time staff. Many HMGs use part-time staff to cover night and weekend shifts.

Trend Today, Initiative Tomorrow

Taken together, SHM’s bi-annual survey and Focused Survey have begun to reveal some of the most prevalent trends within the specialty, including low turnover and a specialty-wide QI emphasis. However, Flores sees room for additional research in the near future.

“There is a lot more to learn about the nature of hospitalists’ involvement in organizational quality initiatives and what benefits that involvement is delivering to their organizations,” she says. “The survey suggests some areas, particularly in the quality arena, where SHM can develop additional programs and services to support hospitalists and the work they do.”

The 10-page 2008-2009 Focused Survey report is available at www.hospitalmedicine.org/shmstore. TH

Brendon Shank is a freelance writer based in Philadelphia.

Most HM groups (HMGs) participate in quality initiatives in their hospitals, according to new SHM research. Moreover, 7 out of 10 HMGs participating in QI initiatives are leading those efforts at their hospitals.

The findings are part of SHM’s 2008-2009 Focused Survey, the latest in a series of reports commissioned by the Practice Analysis Committee. The survey and report concentrate on topics of interest from SHM’s comprehensive, biannual survey of its membership.

The survey compiled responses from 145 HMG leaders. In addition to QI initiatives, participants in the survey responded to a variety of questions, including quality-based incentives, hospitalist turnover, and the use of part-time hospitalists.

—Joe Miller, SHM’s executive advisor to the CEO

“This is certain to be a conversation starter for hospitalists, hospital executives, and others,” says Burke Kealey, MD, FHM, medical director for hospital medicine at St. Paul, Minn.-based HealthPartners and chair of SHM’s Practice Analysis Committee. “The Focused Survey is an opportunity for SHM to answer some of the pressing questions that healthcare executives and providers have about managing a hospitalist practice within the larger context of the hospital.”

Hospital executives and hospitalists use SHM survey findings to better understand what is going on in the specialty, says Joe Miller, SHM’s executive advisor to the CEO. “These surveys answer the kinds of questions that often come up when hospitalists and hospitals begin to evaluate their performance and plan for the future,” Miller says. “We use their questions as source material for this survey, so we can help them answer questions like, ‘How are most hospitalists participating in QI?’ or ‘How are other hospitalists using part-time staff members?’ ”

Hospitalists Lead the Way

Hospitalists continue to be at the forefront of QI initiatives within their hospitals, according to the latest survey. Almost all respondents (96.5%) reported that their HMG participated in QI programs; the average HMG has six hospitalists playing an active role in QI within the hospital.

The survey also found that 72.1% of respondents involved in QI activity reported that their hospitalists were “responsible for leading project(s)” on QI initiatives.

“The findings about the active role hospitalists play in QI initiatives may surprise even the most staunch advocate of QI within the hospital medicine specialty,” says Leslie Flores, MHA, SHM’s director of the Practice Management Institute and leader of the Focused Survey research. “In essence, it shows that nearly every hospitalist group is active in promoting QI, and that the vast majority of them are taking a leadership position to improve quality. … It is remarkable and extremely exciting that hospitalists are so deeply involved in QI in their organizations.”

The survey identified patient safety, clinical QI, and quality-related IT initiatives as most popular.

Quality Incentive Compensation

In order to track HMG quality incentive compensation, the 2008-2009 Focused Survey asked similar questions about the topic to questions in the 2006-2007 Focused Survey. Quality incentive compensation—paying bonuses or additional payments for meeting QI measures—not only increased markedly in the past two years, but a majority of HMGs also have adopted the practice. The number of HMGs that have quality incentive compensation plans has increased by 39% since 2006, according to the survey.

Nine out of 10 HMGs that receive performance-based compensation reported that the source of the compensation was the hospital or health system. In most cases, the compensation was paid to an individual hospitalist, which represents a shift from 2006, when more groups reported receiving the compensation directly.

The survey also shows that hospitals and HMGs use a number of process measures to evaluate QI incentives, including participation in quality or safety committees, transition of care measures, or core measures for heart failure, pneumonia, and acute myocardial infarction.

New Numbers Dispel High Turnover Myth

For years, the conventional wisdom throughout the healthcare community has been that HM suffers from a high turnover rate among its hospitalists. Focused Survey findings suggest otherwise. In fact, turnover rates for hospitalist groups have remained constant since 2005. Nearly a third (31.7%) of HMGs reported no turnover at all within the past 12 months.

“Getting an accurate idea about turnover in hospitalist groups has been an ongoing challenge in our research,” Flores says. “In this year’s Focused Survey, we provided clearer definitions and asked more specific questions to improve our measurement of turnover.”

The added specificity only served to reinforce findings from previous surveys that showed relatively low turnover rates. The most recent research revealed a 12.7% turnover rate, compared with 13% in 2007 and 12% in 2005.

The latest Focused Survey also includes detailed findings on turnover among full-time hospitalists compared with part-time hospitalists.

Part-Time vs. Full-Time

The new data challenge long-held assumptions about the role of part-time hospitalists. The survey queried HMGs about full-time and part-time hospitalist staff, and the proportion of time that each employee covers in the hospital.

Although there isn’t a consensus about what constitutes a full-time hospitalist, it is clear that they cover the vast majority (85%) of HMG staff hours. Part-time hospitalists are responsible for 10% of hospitalist staff hours, and “casual” hospitalists—temporary hospitalists or moonlighters—make up the remaining 5%.

Part-time hospitalists share the same responsibilities as their full-time colleagues, according to the report. More than 70% of HMG leaders said their part-time staff is deployed to cover the same shifts and responsibilities as full-time staff. Many HMGs use part-time staff to cover night and weekend shifts.

Trend Today, Initiative Tomorrow

Taken together, SHM’s bi-annual survey and Focused Survey have begun to reveal some of the most prevalent trends within the specialty, including low turnover and a specialty-wide QI emphasis. However, Flores sees room for additional research in the near future.

“There is a lot more to learn about the nature of hospitalists’ involvement in organizational quality initiatives and what benefits that involvement is delivering to their organizations,” she says. “The survey suggests some areas, particularly in the quality arena, where SHM can develop additional programs and services to support hospitalists and the work they do.”

The 10-page 2008-2009 Focused Survey report is available at www.hospitalmedicine.org/shmstore. TH

Brendon Shank is a freelance writer based in Philadelphia.

Most HM groups (HMGs) participate in quality initiatives in their hospitals, according to new SHM research. Moreover, 7 out of 10 HMGs participating in QI initiatives are leading those efforts at their hospitals.

The findings are part of SHM’s 2008-2009 Focused Survey, the latest in a series of reports commissioned by the Practice Analysis Committee. The survey and report concentrate on topics of interest from SHM’s comprehensive, biannual survey of its membership.

The survey compiled responses from 145 HMG leaders. In addition to QI initiatives, participants in the survey responded to a variety of questions, including quality-based incentives, hospitalist turnover, and the use of part-time hospitalists.

—Joe Miller, SHM’s executive advisor to the CEO

“This is certain to be a conversation starter for hospitalists, hospital executives, and others,” says Burke Kealey, MD, FHM, medical director for hospital medicine at St. Paul, Minn.-based HealthPartners and chair of SHM’s Practice Analysis Committee. “The Focused Survey is an opportunity for SHM to answer some of the pressing questions that healthcare executives and providers have about managing a hospitalist practice within the larger context of the hospital.”

Hospital executives and hospitalists use SHM survey findings to better understand what is going on in the specialty, says Joe Miller, SHM’s executive advisor to the CEO. “These surveys answer the kinds of questions that often come up when hospitalists and hospitals begin to evaluate their performance and plan for the future,” Miller says. “We use their questions as source material for this survey, so we can help them answer questions like, ‘How are most hospitalists participating in QI?’ or ‘How are other hospitalists using part-time staff members?’ ”

Hospitalists Lead the Way

Hospitalists continue to be at the forefront of QI initiatives within their hospitals, according to the latest survey. Almost all respondents (96.5%) reported that their HMG participated in QI programs; the average HMG has six hospitalists playing an active role in QI within the hospital.

The survey also found that 72.1% of respondents involved in QI activity reported that their hospitalists were “responsible for leading project(s)” on QI initiatives.

“The findings about the active role hospitalists play in QI initiatives may surprise even the most staunch advocate of QI within the hospital medicine specialty,” says Leslie Flores, MHA, SHM’s director of the Practice Management Institute and leader of the Focused Survey research. “In essence, it shows that nearly every hospitalist group is active in promoting QI, and that the vast majority of them are taking a leadership position to improve quality. … It is remarkable and extremely exciting that hospitalists are so deeply involved in QI in their organizations.”

The survey identified patient safety, clinical QI, and quality-related IT initiatives as most popular.

Quality Incentive Compensation

In order to track HMG quality incentive compensation, the 2008-2009 Focused Survey asked similar questions about the topic to questions in the 2006-2007 Focused Survey. Quality incentive compensation—paying bonuses or additional payments for meeting QI measures—not only increased markedly in the past two years, but a majority of HMGs also have adopted the practice. The number of HMGs that have quality incentive compensation plans has increased by 39% since 2006, according to the survey.

Nine out of 10 HMGs that receive performance-based compensation reported that the source of the compensation was the hospital or health system. In most cases, the compensation was paid to an individual hospitalist, which represents a shift from 2006, when more groups reported receiving the compensation directly.

The survey also shows that hospitals and HMGs use a number of process measures to evaluate QI incentives, including participation in quality or safety committees, transition of care measures, or core measures for heart failure, pneumonia, and acute myocardial infarction.

New Numbers Dispel High Turnover Myth

For years, the conventional wisdom throughout the healthcare community has been that HM suffers from a high turnover rate among its hospitalists. Focused Survey findings suggest otherwise. In fact, turnover rates for hospitalist groups have remained constant since 2005. Nearly a third (31.7%) of HMGs reported no turnover at all within the past 12 months.

“Getting an accurate idea about turnover in hospitalist groups has been an ongoing challenge in our research,” Flores says. “In this year’s Focused Survey, we provided clearer definitions and asked more specific questions to improve our measurement of turnover.”

The added specificity only served to reinforce findings from previous surveys that showed relatively low turnover rates. The most recent research revealed a 12.7% turnover rate, compared with 13% in 2007 and 12% in 2005.

The latest Focused Survey also includes detailed findings on turnover among full-time hospitalists compared with part-time hospitalists.

Part-Time vs. Full-Time

The new data challenge long-held assumptions about the role of part-time hospitalists. The survey queried HMGs about full-time and part-time hospitalist staff, and the proportion of time that each employee covers in the hospital.

Although there isn’t a consensus about what constitutes a full-time hospitalist, it is clear that they cover the vast majority (85%) of HMG staff hours. Part-time hospitalists are responsible for 10% of hospitalist staff hours, and “casual” hospitalists—temporary hospitalists or moonlighters—make up the remaining 5%.

Part-time hospitalists share the same responsibilities as their full-time colleagues, according to the report. More than 70% of HMG leaders said their part-time staff is deployed to cover the same shifts and responsibilities as full-time staff. Many HMGs use part-time staff to cover night and weekend shifts.

Trend Today, Initiative Tomorrow

Taken together, SHM’s bi-annual survey and Focused Survey have begun to reveal some of the most prevalent trends within the specialty, including low turnover and a specialty-wide QI emphasis. However, Flores sees room for additional research in the near future.

“There is a lot more to learn about the nature of hospitalists’ involvement in organizational quality initiatives and what benefits that involvement is delivering to their organizations,” she says. “The survey suggests some areas, particularly in the quality arena, where SHM can develop additional programs and services to support hospitalists and the work they do.”

The 10-page 2008-2009 Focused Survey report is available at www.hospitalmedicine.org/shmstore. TH

Brendon Shank is a freelance writer based in Philadelphia.

2010: HM Goes to Washington

Enter text here

Enter text here

Enter text here

SHM’s Down with Digital

When hospitalist Robert Wachter, MD, FHM, started his HM blog almost two years ago, he didn’t anticipate that one of his blog entries would be about pop-music icon Britney Spears. Or that it would become his most popular, attracting nearly double the number of readers as his next-most-popular post.

Dr. Wachter—professor and chief of the division of hospital medicine at the University of California at San Francisco, a former SHM president, and author of the blog “Wachter’s World” (www.wachtersworld.com)—attributes the popularity of that post partly to Spears, but also to the fact it touched on a topic that always sparks interest among hospitalists, other healthcare providers, and hospital executives: the relationship between doctors and nurses in a hospital setting. Dr. Wachter’s most-popular post used Spears’ hospitalization in early 2008 and the controversy surrounding care providers who sneaked a peek at her medical records to make a point about how physicians and nurses often are treated differently in a hospital setting.

—Robert Chang, MD, hospitalist, University of Michigan Medical Center, Ann Arbor

But that was just one story. In the first year alone, Dr. Wachter wrote 76 blog posts, each of which easily exceeded 1,000 words. During the first year of blogging, the average post was read more than 1,800 times and the Web site attracted nearly 140,000 views.

“This has been one of the most gratifying things I’ve done in my career,” Dr. Wachter says. “I’ve published hundreds of articles in journals, but something about this form has an immediacy and connection to the audience that feels very important.”

And he isn’t alone. Blogs and HM have experienced similar growth trajectories in recent years. Now they are coming together to help hospitalists understand the most pressing issues in the specialty and provide the best care to hospitalized patients.

A Blog Primer

Blogs are Web sites that feature regular articles, or “posts.” The topic, length, and regularity of the posts are entirely at the discretion of the author, also known as the blogger. Some blogs are updated dozens of times a day; others, such as Wachter’s World, only feature new posts every week or so, but often with more depth and insight.

Although initially dismissed by many as outlets for trivial information, blogs are now recognized by experts in nearly every field as an important and cost-effective way to spark conversation and take positions on issues of the day.

Compared with more traditional media outlets, the ability to create dialogue is perhaps the most distinctive blog characteristic. Bloggers often invite readers to post or e-mail comments, creating interactivity between author and reader. In addition, many blogs automatically e-mail and distribute new blog posts to subscribers.

The “viral” aspect of blogs is a major contributor to their success. For instance, say Dr. Wachter writes a new blog post at 8:30 in the morning. Shortly thereafter, his readers will receive an automatically generated e-mail from the blog informing readers that Dr. Wachter has posted a new blog entry. When the reader visits the blog and reads the new post, they might think it could be of interest to a colleague, so they forward it to a colleague via e-mail. The colleague not only reads the article, but they also are impressed and post a comment for the rest of the blog’s readers to view.

SHM Blogs Advance the Specialty

The feedback loop of blogs isn’t limited to the on-screen world. That’s the lesson learned by clinical hospitalist Danielle Scheurer, MD, MSCR, SHM’s Web editor and director of General Medical Services at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston.

As the author of SHM’s new clinical practice blog, “Hospital Medicine Quick Hits,” Dr. Scheurer knew the fledgling blog provided a valuable resource to busy clinicians, but she didn’t expect it to get back to her. She recalls that one day, “my blog was quoted to me by one of my house staff, who said, ‘I found this great hospital medicine blog today,’ and he didn’t realize I was the author.”

For the blog, Scheurer scours through 50 of the top medical journals for articles that are relevant to practicing clinical hospitalists. She posts concise overviews of the articles, along with links to the original research.

For hospitalists who have an interest in practice management, SHM offers another new blog, “The Hospitalist Leader.” It shares perspectives and ideas on the day-to-day interactions that hospitalists encounter and how best to administer a hospital practice. Four hospitalist co-authors—Robert Chang, MD, FHM, a hospitalist at the University of Michigan Medical Center in Ann Arbor; Rusty Holman, MD, FHM, chief operating officer of Brentwood, Tenn.-based Cogent Healthcare; John Nelson, MD, FHM, principal in Nelson/Flores Associates, a national hospitalist practice management consulting firm; and Robert Bessler, MD, FHM, a hospitalist with Sound Inpatient Physicians in Tacoma, Wash.—use many of their own experiences in the hospital as raw material for the blog.

Dr. Chang views the blog as another way to move HM forward: “I trust and hope that we can use the blog to help the professional status of our profession, as this ultimately will determine the choices we make, large and small,” he says.

What’s Next

If you’re attending HM09 this year, don’t be surprised if you see someone else in the crowd excitedly typing into an iPhone or BlackBerry. You just might find a new blog post on the session you just attended.

Gone are the old images of a blogger in slippers and pajamas stealthily typing on the computer in the basement. These days, posting at or during an event, on site and in real time, is standard practice for many bloggers. In fact, SHM made a concerted effort to invite the most influential bloggers in the industry to HM09.

And if the person typing away isn’t “live blogging,” he may be “tweeting,” or adding super-short updates to the popular Web site Twitter. For many bloggers, it’s a way of communicating instantaneously with their audiences; once they post a blog article, they “tweet”—or send out—the link to thousands of readers.

SHM has its own Twitter account—@SHMLive—and uses the account to keep interested hospitalists updated on new blog posts, society news, and other HM developments.

“Hospital medicine is constantly evolving,” says Heather Abdel-Salam, SHM’s public relations and marketing coordinator, “and so do our efforts t.o communicate the best practices in the specialty. Blogs, Twitter feeds, and other online outreach are a big part of how we promote hospital medicine and help it grow within the healthcare arena.” TH

Brendon Shank is a freelance writer based in Philadelphia.

When hospitalist Robert Wachter, MD, FHM, started his HM blog almost two years ago, he didn’t anticipate that one of his blog entries would be about pop-music icon Britney Spears. Or that it would become his most popular, attracting nearly double the number of readers as his next-most-popular post.

Dr. Wachter—professor and chief of the division of hospital medicine at the University of California at San Francisco, a former SHM president, and author of the blog “Wachter’s World” (www.wachtersworld.com)—attributes the popularity of that post partly to Spears, but also to the fact it touched on a topic that always sparks interest among hospitalists, other healthcare providers, and hospital executives: the relationship between doctors and nurses in a hospital setting. Dr. Wachter’s most-popular post used Spears’ hospitalization in early 2008 and the controversy surrounding care providers who sneaked a peek at her medical records to make a point about how physicians and nurses often are treated differently in a hospital setting.

—Robert Chang, MD, hospitalist, University of Michigan Medical Center, Ann Arbor

But that was just one story. In the first year alone, Dr. Wachter wrote 76 blog posts, each of which easily exceeded 1,000 words. During the first year of blogging, the average post was read more than 1,800 times and the Web site attracted nearly 140,000 views.

“This has been one of the most gratifying things I’ve done in my career,” Dr. Wachter says. “I’ve published hundreds of articles in journals, but something about this form has an immediacy and connection to the audience that feels very important.”

And he isn’t alone. Blogs and HM have experienced similar growth trajectories in recent years. Now they are coming together to help hospitalists understand the most pressing issues in the specialty and provide the best care to hospitalized patients.

A Blog Primer

Blogs are Web sites that feature regular articles, or “posts.” The topic, length, and regularity of the posts are entirely at the discretion of the author, also known as the blogger. Some blogs are updated dozens of times a day; others, such as Wachter’s World, only feature new posts every week or so, but often with more depth and insight.

Although initially dismissed by many as outlets for trivial information, blogs are now recognized by experts in nearly every field as an important and cost-effective way to spark conversation and take positions on issues of the day.

Compared with more traditional media outlets, the ability to create dialogue is perhaps the most distinctive blog characteristic. Bloggers often invite readers to post or e-mail comments, creating interactivity between author and reader. In addition, many blogs automatically e-mail and distribute new blog posts to subscribers.

The “viral” aspect of blogs is a major contributor to their success. For instance, say Dr. Wachter writes a new blog post at 8:30 in the morning. Shortly thereafter, his readers will receive an automatically generated e-mail from the blog informing readers that Dr. Wachter has posted a new blog entry. When the reader visits the blog and reads the new post, they might think it could be of interest to a colleague, so they forward it to a colleague via e-mail. The colleague not only reads the article, but they also are impressed and post a comment for the rest of the blog’s readers to view.

SHM Blogs Advance the Specialty

The feedback loop of blogs isn’t limited to the on-screen world. That’s the lesson learned by clinical hospitalist Danielle Scheurer, MD, MSCR, SHM’s Web editor and director of General Medical Services at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston.

As the author of SHM’s new clinical practice blog, “Hospital Medicine Quick Hits,” Dr. Scheurer knew the fledgling blog provided a valuable resource to busy clinicians, but she didn’t expect it to get back to her. She recalls that one day, “my blog was quoted to me by one of my house staff, who said, ‘I found this great hospital medicine blog today,’ and he didn’t realize I was the author.”

For the blog, Scheurer scours through 50 of the top medical journals for articles that are relevant to practicing clinical hospitalists. She posts concise overviews of the articles, along with links to the original research.

For hospitalists who have an interest in practice management, SHM offers another new blog, “The Hospitalist Leader.” It shares perspectives and ideas on the day-to-day interactions that hospitalists encounter and how best to administer a hospital practice. Four hospitalist co-authors—Robert Chang, MD, FHM, a hospitalist at the University of Michigan Medical Center in Ann Arbor; Rusty Holman, MD, FHM, chief operating officer of Brentwood, Tenn.-based Cogent Healthcare; John Nelson, MD, FHM, principal in Nelson/Flores Associates, a national hospitalist practice management consulting firm; and Robert Bessler, MD, FHM, a hospitalist with Sound Inpatient Physicians in Tacoma, Wash.—use many of their own experiences in the hospital as raw material for the blog.

Dr. Chang views the blog as another way to move HM forward: “I trust and hope that we can use the blog to help the professional status of our profession, as this ultimately will determine the choices we make, large and small,” he says.

What’s Next

If you’re attending HM09 this year, don’t be surprised if you see someone else in the crowd excitedly typing into an iPhone or BlackBerry. You just might find a new blog post on the session you just attended.

Gone are the old images of a blogger in slippers and pajamas stealthily typing on the computer in the basement. These days, posting at or during an event, on site and in real time, is standard practice for many bloggers. In fact, SHM made a concerted effort to invite the most influential bloggers in the industry to HM09.

And if the person typing away isn’t “live blogging,” he may be “tweeting,” or adding super-short updates to the popular Web site Twitter. For many bloggers, it’s a way of communicating instantaneously with their audiences; once they post a blog article, they “tweet”—or send out—the link to thousands of readers.

SHM has its own Twitter account—@SHMLive—and uses the account to keep interested hospitalists updated on new blog posts, society news, and other HM developments.

“Hospital medicine is constantly evolving,” says Heather Abdel-Salam, SHM’s public relations and marketing coordinator, “and so do our efforts t.o communicate the best practices in the specialty. Blogs, Twitter feeds, and other online outreach are a big part of how we promote hospital medicine and help it grow within the healthcare arena.” TH

Brendon Shank is a freelance writer based in Philadelphia.

When hospitalist Robert Wachter, MD, FHM, started his HM blog almost two years ago, he didn’t anticipate that one of his blog entries would be about pop-music icon Britney Spears. Or that it would become his most popular, attracting nearly double the number of readers as his next-most-popular post.

Dr. Wachter—professor and chief of the division of hospital medicine at the University of California at San Francisco, a former SHM president, and author of the blog “Wachter’s World” (www.wachtersworld.com)—attributes the popularity of that post partly to Spears, but also to the fact it touched on a topic that always sparks interest among hospitalists, other healthcare providers, and hospital executives: the relationship between doctors and nurses in a hospital setting. Dr. Wachter’s most-popular post used Spears’ hospitalization in early 2008 and the controversy surrounding care providers who sneaked a peek at her medical records to make a point about how physicians and nurses often are treated differently in a hospital setting.

—Robert Chang, MD, hospitalist, University of Michigan Medical Center, Ann Arbor

But that was just one story. In the first year alone, Dr. Wachter wrote 76 blog posts, each of which easily exceeded 1,000 words. During the first year of blogging, the average post was read more than 1,800 times and the Web site attracted nearly 140,000 views.

“This has been one of the most gratifying things I’ve done in my career,” Dr. Wachter says. “I’ve published hundreds of articles in journals, but something about this form has an immediacy and connection to the audience that feels very important.”

And he isn’t alone. Blogs and HM have experienced similar growth trajectories in recent years. Now they are coming together to help hospitalists understand the most pressing issues in the specialty and provide the best care to hospitalized patients.

A Blog Primer

Blogs are Web sites that feature regular articles, or “posts.” The topic, length, and regularity of the posts are entirely at the discretion of the author, also known as the blogger. Some blogs are updated dozens of times a day; others, such as Wachter’s World, only feature new posts every week or so, but often with more depth and insight.

Although initially dismissed by many as outlets for trivial information, blogs are now recognized by experts in nearly every field as an important and cost-effective way to spark conversation and take positions on issues of the day.

Compared with more traditional media outlets, the ability to create dialogue is perhaps the most distinctive blog characteristic. Bloggers often invite readers to post or e-mail comments, creating interactivity between author and reader. In addition, many blogs automatically e-mail and distribute new blog posts to subscribers.

The “viral” aspect of blogs is a major contributor to their success. For instance, say Dr. Wachter writes a new blog post at 8:30 in the morning. Shortly thereafter, his readers will receive an automatically generated e-mail from the blog informing readers that Dr. Wachter has posted a new blog entry. When the reader visits the blog and reads the new post, they might think it could be of interest to a colleague, so they forward it to a colleague via e-mail. The colleague not only reads the article, but they also are impressed and post a comment for the rest of the blog’s readers to view.

SHM Blogs Advance the Specialty

The feedback loop of blogs isn’t limited to the on-screen world. That’s the lesson learned by clinical hospitalist Danielle Scheurer, MD, MSCR, SHM’s Web editor and director of General Medical Services at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston.

As the author of SHM’s new clinical practice blog, “Hospital Medicine Quick Hits,” Dr. Scheurer knew the fledgling blog provided a valuable resource to busy clinicians, but she didn’t expect it to get back to her. She recalls that one day, “my blog was quoted to me by one of my house staff, who said, ‘I found this great hospital medicine blog today,’ and he didn’t realize I was the author.”

For the blog, Scheurer scours through 50 of the top medical journals for articles that are relevant to practicing clinical hospitalists. She posts concise overviews of the articles, along with links to the original research.

For hospitalists who have an interest in practice management, SHM offers another new blog, “The Hospitalist Leader.” It shares perspectives and ideas on the day-to-day interactions that hospitalists encounter and how best to administer a hospital practice. Four hospitalist co-authors—Robert Chang, MD, FHM, a hospitalist at the University of Michigan Medical Center in Ann Arbor; Rusty Holman, MD, FHM, chief operating officer of Brentwood, Tenn.-based Cogent Healthcare; John Nelson, MD, FHM, principal in Nelson/Flores Associates, a national hospitalist practice management consulting firm; and Robert Bessler, MD, FHM, a hospitalist with Sound Inpatient Physicians in Tacoma, Wash.—use many of their own experiences in the hospital as raw material for the blog.

Dr. Chang views the blog as another way to move HM forward: “I trust and hope that we can use the blog to help the professional status of our profession, as this ultimately will determine the choices we make, large and small,” he says.

What’s Next

If you’re attending HM09 this year, don’t be surprised if you see someone else in the crowd excitedly typing into an iPhone or BlackBerry. You just might find a new blog post on the session you just attended.

Gone are the old images of a blogger in slippers and pajamas stealthily typing on the computer in the basement. These days, posting at or during an event, on site and in real time, is standard practice for many bloggers. In fact, SHM made a concerted effort to invite the most influential bloggers in the industry to HM09.

And if the person typing away isn’t “live blogging,” he may be “tweeting,” or adding super-short updates to the popular Web site Twitter. For many bloggers, it’s a way of communicating instantaneously with their audiences; once they post a blog article, they “tweet”—or send out—the link to thousands of readers.

SHM has its own Twitter account—@SHMLive—and uses the account to keep interested hospitalists updated on new blog posts, society news, and other HM developments.

“Hospital medicine is constantly evolving,” says Heather Abdel-Salam, SHM’s public relations and marketing coordinator, “and so do our efforts t.o communicate the best practices in the specialty. Blogs, Twitter feeds, and other online outreach are a big part of how we promote hospital medicine and help it grow within the healthcare arena.” TH

Brendon Shank is a freelance writer based in Philadelphia.

VTE Awareness Month

Jason Stein, MD, knows he could walk into almost any nursing unit in any hospital in the country, ask a simple question, and get blank stares in return.

“I would ask, ‘Which patients here in the nursing unit don’t have an order for VTE prophylaxis?’ ” says Dr. Stein, associate director for quality improvement and assistant professor of medicine at Emory University School of Medicine in Atlanta. “And they would tell me, ‘What kind of place do you think this is? How can we possibly know that?’ ”

It’s not idle chat. Venous thromboembolism (VTE) is a condition known throughout HM for three things: It runs rampant in hospitals; it can be deadly; and it’s easily preventable.

This month, SHM—along with dozens of other healthcare organizations, including the Agency for Healthcare Research Quality (AHRQ)—is highlighting the dangers of VTE and deep vein thrombosis (DVT), and promoting best practices to prevent them.

“SHM’s leadership of awareness efforts and championing VTE [prevention] has played an important role in keeping this on everybody’s mind,” Dr. Stein says.

VTE: A Hospital-Based Epidemic

Although it is easy to target at-risk populations and prevent it, VTE is widespread and dangerous.

“By published estimates, each year VTE kills more people than HIV, car accidents, and breast cancer combined,” says Gregory A. Maynard, MD, Ms, chief of the division of hospital medicine and clinical professor of medicine at the University of California at San Diego.

The risk of VTE in hospital patients should give hospitalists and their colleagues pause. Here’s why:

- According to the American Heart Association, more than 200,000 cases of VTE are reported each year, and VTE occurs for the first time in approximately 100 out of every 100,000 persons each year;

- Research published last year in The Lancet estimates 52% of hospitalized patients are at risk for VTE;

- 1 in 3 VTE patients experiences a pulmonary embolism;

- 30% of new VTE patients die within three days;

- 20% of new VTE patients die suddenly from pulmonary embolus; and

- DVT is responsible for approximately 8,000 hospital discharges every year. Pulmonary embolism accounts for nearly 100,000.

Risk Factors and Prevention

In a hospital setting, VTE risk factors are especially straightforward to monitor and prevent, but Dr. Maynard sees room for improvement.

“We don’t need to do better things; we need to do things better,” he told colleagues at a recent grand rounds. “Pharmacologic prophylaxis is the preferred way to prevent VTE in the hospital, which can reduce DVT and pulmonary embolism by 50% to 65%.”

Most hospital patients have at least one of these VTE risk factors, which are sorted into three categories:

- Stasis: conditions such as advanced age, immobility, paralysis, or stroke;

- Hypercoaguability: smoking, pregnancy, cancer, or sepsis; and

- Endothelial damage: surgery, prior VTE, central lines, or trauma.

Because the potential VTE risk is so high in hospital patients, the assessment must go hand in hand with prophylaxis, says Dr. Maynard and other hospitalists working with VTE.

Recent research has shown that prescribing medications to prevent VTE before it begins is safe, effective, and cost-effective.

The Hospitalist’s Role

The responsibility for VTE risk assessment and prevention often falls to hospitalists. In its online VTE Resource Room, SHM provides information for hospitalists working to assess and prevent VTE in their patients. It also provides a complete toolkit for hospitalists interested in addressing VTE prevention systematically throughout their hospitals. The toolkit is part of a comprehensive VTE Prevention Collaborative, which provides real-world mentoring and materials to hospitalists as they develop VTE monitoring and prevention programs.

“In 2005, when SHM set up the Quality Improvement resource room, we began with VTE prophylaxis,” Dr. Stein says. “VTE is the No. 1 cause of preventable death in hospitals, and preventing it is a fundamentally simple thing for hospitalists to do. We’re trying to get physicians to order a shot in the abdomen once a day. … If we can’t do that, we’re in trouble. On the flipside, if we can figure that out, we can derive mechanisms that we can apply to more complex problems in care.”

Together with SHM, Drs. Stein and Maynard have pioneered a two-pronged approach known as “measure-vention.” The underlying principal of measure-vention is that monitoring for VTE risk in real time can empower hospital staff to remedy issues in real time. In most hospitals, VTE risk can only be measured retrospectively through quality improvement data, which can take months to collect.

SHM and Dr. Stein have implemented an information technology approach at five of Emory’s hospitals. Each facility assesses patients who don’t have VTE prophylaxis every hour. The data is distributed to nursing stations, where nurses and other providers can apply VTE interventions within minutes. The program has driven Emory’s VTE prophylaxis rates to more than 90%, and Dr. Stein is working to make the program exportable to other hospitals, with the help of funding and assistance from SHM.

“As the leader of the VTE prevention program at Emory hospitals, I hear lots of stories about preventable VTE—not just about patients, but from friends of friends and family members,” he says. “It’s extraordinary.” TH

Brendon Shank is a freelance writer based in Philadelphia.

Jason Stein, MD, knows he could walk into almost any nursing unit in any hospital in the country, ask a simple question, and get blank stares in return.

“I would ask, ‘Which patients here in the nursing unit don’t have an order for VTE prophylaxis?’ ” says Dr. Stein, associate director for quality improvement and assistant professor of medicine at Emory University School of Medicine in Atlanta. “And they would tell me, ‘What kind of place do you think this is? How can we possibly know that?’ ”

It’s not idle chat. Venous thromboembolism (VTE) is a condition known throughout HM for three things: It runs rampant in hospitals; it can be deadly; and it’s easily preventable.

This month, SHM—along with dozens of other healthcare organizations, including the Agency for Healthcare Research Quality (AHRQ)—is highlighting the dangers of VTE and deep vein thrombosis (DVT), and promoting best practices to prevent them.

“SHM’s leadership of awareness efforts and championing VTE [prevention] has played an important role in keeping this on everybody’s mind,” Dr. Stein says.

VTE: A Hospital-Based Epidemic

Although it is easy to target at-risk populations and prevent it, VTE is widespread and dangerous.

“By published estimates, each year VTE kills more people than HIV, car accidents, and breast cancer combined,” says Gregory A. Maynard, MD, Ms, chief of the division of hospital medicine and clinical professor of medicine at the University of California at San Diego.

The risk of VTE in hospital patients should give hospitalists and their colleagues pause. Here’s why:

- According to the American Heart Association, more than 200,000 cases of VTE are reported each year, and VTE occurs for the first time in approximately 100 out of every 100,000 persons each year;

- Research published last year in The Lancet estimates 52% of hospitalized patients are at risk for VTE;

- 1 in 3 VTE patients experiences a pulmonary embolism;

- 30% of new VTE patients die within three days;

- 20% of new VTE patients die suddenly from pulmonary embolus; and

- DVT is responsible for approximately 8,000 hospital discharges every year. Pulmonary embolism accounts for nearly 100,000.

Risk Factors and Prevention

In a hospital setting, VTE risk factors are especially straightforward to monitor and prevent, but Dr. Maynard sees room for improvement.

“We don’t need to do better things; we need to do things better,” he told colleagues at a recent grand rounds. “Pharmacologic prophylaxis is the preferred way to prevent VTE in the hospital, which can reduce DVT and pulmonary embolism by 50% to 65%.”

Most hospital patients have at least one of these VTE risk factors, which are sorted into three categories:

- Stasis: conditions such as advanced age, immobility, paralysis, or stroke;

- Hypercoaguability: smoking, pregnancy, cancer, or sepsis; and

- Endothelial damage: surgery, prior VTE, central lines, or trauma.

Because the potential VTE risk is so high in hospital patients, the assessment must go hand in hand with prophylaxis, says Dr. Maynard and other hospitalists working with VTE.

Recent research has shown that prescribing medications to prevent VTE before it begins is safe, effective, and cost-effective.

The Hospitalist’s Role

The responsibility for VTE risk assessment and prevention often falls to hospitalists. In its online VTE Resource Room, SHM provides information for hospitalists working to assess and prevent VTE in their patients. It also provides a complete toolkit for hospitalists interested in addressing VTE prevention systematically throughout their hospitals. The toolkit is part of a comprehensive VTE Prevention Collaborative, which provides real-world mentoring and materials to hospitalists as they develop VTE monitoring and prevention programs.

“In 2005, when SHM set up the Quality Improvement resource room, we began with VTE prophylaxis,” Dr. Stein says. “VTE is the No. 1 cause of preventable death in hospitals, and preventing it is a fundamentally simple thing for hospitalists to do. We’re trying to get physicians to order a shot in the abdomen once a day. … If we can’t do that, we’re in trouble. On the flipside, if we can figure that out, we can derive mechanisms that we can apply to more complex problems in care.”

Together with SHM, Drs. Stein and Maynard have pioneered a two-pronged approach known as “measure-vention.” The underlying principal of measure-vention is that monitoring for VTE risk in real time can empower hospital staff to remedy issues in real time. In most hospitals, VTE risk can only be measured retrospectively through quality improvement data, which can take months to collect.

SHM and Dr. Stein have implemented an information technology approach at five of Emory’s hospitals. Each facility assesses patients who don’t have VTE prophylaxis every hour. The data is distributed to nursing stations, where nurses and other providers can apply VTE interventions within minutes. The program has driven Emory’s VTE prophylaxis rates to more than 90%, and Dr. Stein is working to make the program exportable to other hospitals, with the help of funding and assistance from SHM.

“As the leader of the VTE prevention program at Emory hospitals, I hear lots of stories about preventable VTE—not just about patients, but from friends of friends and family members,” he says. “It’s extraordinary.” TH

Brendon Shank is a freelance writer based in Philadelphia.

Jason Stein, MD, knows he could walk into almost any nursing unit in any hospital in the country, ask a simple question, and get blank stares in return.

“I would ask, ‘Which patients here in the nursing unit don’t have an order for VTE prophylaxis?’ ” says Dr. Stein, associate director for quality improvement and assistant professor of medicine at Emory University School of Medicine in Atlanta. “And they would tell me, ‘What kind of place do you think this is? How can we possibly know that?’ ”

It’s not idle chat. Venous thromboembolism (VTE) is a condition known throughout HM for three things: It runs rampant in hospitals; it can be deadly; and it’s easily preventable.

This month, SHM—along with dozens of other healthcare organizations, including the Agency for Healthcare Research Quality (AHRQ)—is highlighting the dangers of VTE and deep vein thrombosis (DVT), and promoting best practices to prevent them.

“SHM’s leadership of awareness efforts and championing VTE [prevention] has played an important role in keeping this on everybody’s mind,” Dr. Stein says.

VTE: A Hospital-Based Epidemic

Although it is easy to target at-risk populations and prevent it, VTE is widespread and dangerous.

“By published estimates, each year VTE kills more people than HIV, car accidents, and breast cancer combined,” says Gregory A. Maynard, MD, Ms, chief of the division of hospital medicine and clinical professor of medicine at the University of California at San Diego.

The risk of VTE in hospital patients should give hospitalists and their colleagues pause. Here’s why: