User login

Pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic treatment options for panic disorder

Panic disorder: Break the fear circuit

Ms. K, a 24-year-old waitress who lives with her boyfriend, was referred by her primary care physician for evaluation of panic attacks that began “out of nowhere” at work approximately 6 months ago. The unpredictable attacks occur multiple times per week, causing her to leave work and cancel shifts.

Ms. K reports that before the panic attacks began, she felt happy in her relationship, enjoyed hobbies, and was hopeful about the future. However, she has become concerned that a potentially catastrophic illness is causing her panic attacks. She researches her symptoms on the Internet, and is preoccupied with the possibility of sudden death due to an undiagnosed heart condition. Multiple visits to the emergency room have not identified any physical abnormalities. Her primary care doctor prescribed alprazolam, 0.5 mg as needed for panic attacks, which she reports is helpful, “but only in the moment of the attacks.” Ms. K avoids alcohol and illicit substances and limits her caffeine intake. She is not willing to accept that her life “feels so limited.” Her dream of earning a nursing degree and eventually starting a family now seems unattainable.

Panic disorder (PD) occurs in 3% to 5% of adults, with women affected at roughly twice the rate of men.1 Causing a broad range of distress and varying degrees of impairment, PD commonly occurs with other psychiatric disorders. For most patients, treatment is effective, but those who do not respond to initial approaches require a thoughtful, stepped approach to care. Key considerations include establishing an accurate diagnosis, clarifying comorbid illnesses, ascertaining patient beliefs and expectations, and providing appropriately dosed and maintained treatments.

Panic attacks vs PD

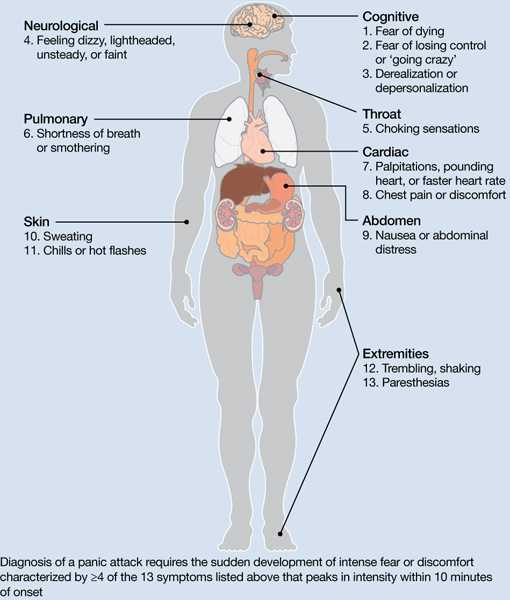

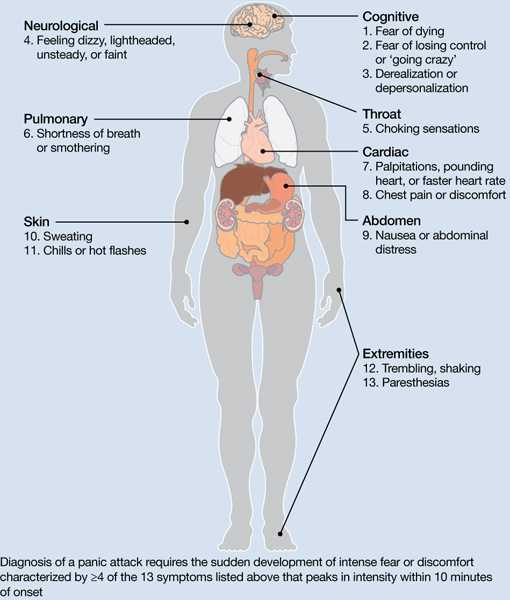

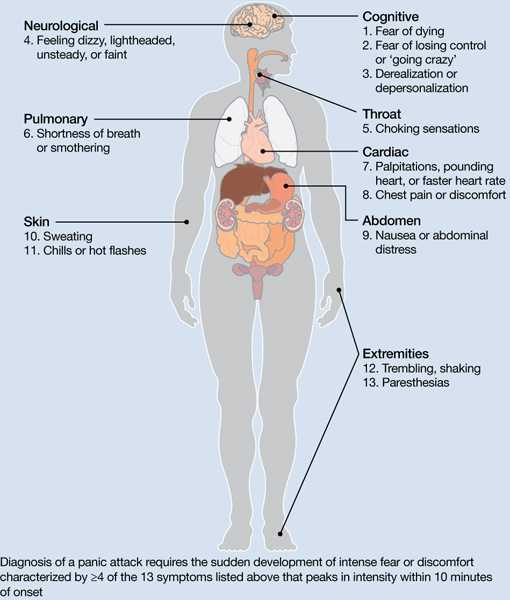

Panic attacks consist of rapid onset of intense anxiety, with prominent somatic symptoms, that peaks within 10 minutes (Figure).2 Attacks in which <4 of the listed symptoms occur are considered limited-symptom panic attacks.

Figure: Body locations of panic attack symptoms

Diagnosis of a panic attack requires the sudden development of intense fear or discomfort characterized by ≥4 of the 13 symptoms listed above that peaks in intensity within 10 minutes of onset

Source: Reference 2

Panic attacks can occur with various disorders, including other anxiety disorders, mood disorders, and substance intoxication or withdrawal. Because serious medical conditions can present with panic-like symptoms, the initial occurrence of such symptoms warrants consideration of physiological causes. For a Box2 that describes the differential diagnosis of panic attacks, see this article at CurrentPsychiatry.com.

To meet diagnostic criteria for panic disorder, panic attacks must initially occur “out of the blue,” meaning no specific object or situation induced the attack. The differential diagnosis of panic attacks includes assessing for other psychiatric disorders that may involve panic attacks. Evaluation requires considering the context in which the panic attacks occur, including their start date, pattern of attacks, instigating situations, and associated thoughts.

Social phobia. Attacks occur only during or immediately before a social interaction in which the patient fears embarrassing himself or herself.

Obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD). Attacks occur when the patient cannot avoid exposure to an obsessional fear or is prevented from performing a ritual that diffuses obsessional anxiety.

Posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Attacks occur when confronted by a trauma-related memory or trigger.

Specific phobia. Attacks occur only when the patient encounters a specifically feared object, place, or situation, unrelated to social phobia, OCD, or PTSD.

Medical conditions. Conditions to consider include—but are not limited to—hyperthyroidism, pulmonary embolism, myocardial infarction, cardiac dysrhythmias, hypoglycemia, asthma, partial complex seizures, and pheochromocytoma.

Source: Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 4th ed, text rev. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2000

A PD diagnosis requires that repeated panic attacks initially must occur from “out of the blue,” meaning no specific object or situation induced the attack. In addition, the diagnosis requires 1 of 3 types of psychological or behavioral changes as a result of the attacks (Table 1).2 Agoraphobia is diagnosed if 1 of the behavioral changes is avoidance of places or situations from which escape might be embarrassing or difficult should an attack occur. A patient can be diagnosed as having PD with agoraphobia, PD without agoraphobia, or agoraphobia without PD (ie, experiences only limited symptom panic attacks, but avoids situations or stimuli associated with them).

Table 1

Definitions of panic disorder and agoraphobia

| Panic disorder |

|---|

|

| Agoraphobia |

| Anxiety about, or avoidance of, being in places or situations from which escape might be difficult or embarrassing, or in which help may not be available in the event of having an unexpected or situationally predisposed panic attack or panic-like symptoms. Agoraphobic fears typically involve characteristic clusters of situations that include being outside the home alone, being in a crowd, standing in a line, being on a bridge, or traveling in a bus, train, or automobile |

| Source: Reference 2 |

Comorbidities are common in patients with PD and predict greater difficulty achieving remission (Box).1,3-6

The most common psychiatric conditions that co-occur with panic disorder (PD) are other anxiety disorders, mood disorders, personality disorders, and substance use disorders.1 Carefully assess the severity and degree of impairment or distress arising from each condition to prioritize treatment goals. For example, treating panic attacks would be a lower priority in a patient with untreated bipolar disorder.

Assessing comorbid substance abuse is important in selecting PD treatments. Benzodiazepines should almost always be avoided in patients with a history of drug abuse—illicit or prescribed. Although complete abstinence should not be a prerequisite for beginning PD treatment, detoxification and concomitant substance abuse treatment are essential.3

Comorbid mood disorders also affect the course of PD treatment. Antidepressants are effective for treating depression and PD, whereas benzodiazepines are not effective for depression.4 Antidepressants in patients with bipolar disorder are controversial because these medications might induce mixed or elevated mood states or rapid cycling. In these complicated patients, consider antidepressants lower in the treatment algorithm.5

Other conditions to consider before beginning treatment include pregnancy or the possibility of becoming pregnant in the near future and suicidal ideation. PD is associated with increased risk for suicidal ideation and progression to suicide attempts, particularly in patients with a comorbid mood or psychotic disorder.6 In addition, consider the potential impact of medications on comorbid medical conditions.

Treatment begins with education

The goal of treatment is remission of symptoms, ideally including an absence of panic attacks, agoraphobic avoidance, and anticipatory anxiety.1 The Panic Disorder Severity Scale self-report is a validated measure of panic symptoms that may be useful in clinical practice.7

The first step in treatment is educating patients about panic attacks, framing them as an overreactive fear circuit in the brain that produces physical symptoms that are not dangerous. Using a brain model that shows the location of the amygdala, hippocampus, and prefrontal cortex—which play crucial roles in generating and controlling anxiety and fear—can make this discussion more concrete.8 Although highly simplified, such models allow clinicians to demonstrate that excessive reactivity of limbic regions can be reduced by both top-down (cortico-limbic connections via cognitive-behavioral therapy [CBT]) and bottom-up (pharmacotherapy directly acting on limbic structures) approaches. Such discussions lead to treatment recommendations for CBT, pharmacotherapy, or their combination.

No single treatment has emerged as the definitive “best” for PD, and no reliable predictors can guide specific treatment for an individual.3 Combining CBT with pharmacotherapy produces higher short-term response rates than either treatment alone, but in the long term, combination treatment does not appear to be superior to CBT alone.9 Base the initial treatment selection for PD on patient preference, treatment availability and cost, and comorbid medical and psychiatric conditions. For an Algorithm to guide treatment decisions, see this article at CurrentPsychiatry.com.

Algorithm: Treatment for panic disorder: A suggested algorithm

aPoor response to an SSRI should lead to a switch to venlafaxine extended-release, and vice versa

bBenzodiazepines are relatively contraindicated in geriatric patients and patients with a history of substance abuse or dependence

CBT: cognitive-behavioral therapy; MAOI: monoamine oxidase inhibitor; SSRI: selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor; TCA: tricyclic antidepressant; Ven XR: venlafaxine extended-release

First-line treatments

Psychotherapy. CBT is the most efficacious psychotherapy for PD. Twelve to 15 sessions of CBT has demonstrated efficacy for PD, with additional effects on comorbid anxiety and depressive symptoms.10 No large clinical trials of CBT have used cognitive restructuring alone; all have included at least some component of exposure that requires the patient to confront feared physical sensations. Gains during treatment may be steady and gradual or sudden and uneven, with rapid improvement in some but not all symptoms. CBT and pharmacotherapy have demonstrated similar levels of benefit in short-term trials, but CBT has proven superior in most9 but not all11 trials evaluating long-term outcomes, particularly compared with pharmacotherapy that is discontinued during follow-up. Although less studied, group CBT also may be considered if a patient cannot afford individual CBT.

Pharmacotherapy. Evidence supports selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), venlafaxine extended-release (XR), benzodiazepines, and tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs) as effective treatments for PD.3 No class of medication has demonstrated superiority over others in short-term treatment.3,12 Because of the medical risks associated with benzodiazepines and TCAs, an SSRI or venlafaxine XR should be the first medication option for most patients. Fluoxetine, paroxetine, sertraline, and venlafaxine XR are FDA-approved for PD. Paroxetine is associated with weight gain and may increase the risk for panic recurrence upon discontinuation more than sertraline, making it a less favorable option for many patients.13 Start doses at half the normal starting dose used for treating major depressive disorder and continue for 4 to 7 days, then increase to the minimal effective dose. For a Table3 that lists dosing recommendations for antidepressants to treat PD, see this article at CurrentPsychiatry.com. If there is no improvement by 4 weeks, increase the dose every 2 to 4 weeks until remission is achieved or side effects prevent further dose increases.

Table

Recommended doses for antidepressants used to treat panic disorder

| Medication | Starting dose (mg/d) | Therapeutic range (mg/d) |

|---|---|---|

| SSRIs | ||

| Citalopram | 10 | 20 to 40 |

| Escitalopram | 5 | 10 to 40 |

| Fluoxetine | 5 to 10 | 20 to 80 |

| Fluvoxamine | 25 | 100 to 300 |

| Paroxetine | 10 | 20 to 80 |

| Paroxetine CR | 12.5 | 25 to 50 |

| Sertraline | 25 | 100 to 200 |

| SNRIs | ||

| Duloxetine | 20 to 30 | 60 to 120 |

| Venlafaxine XR | 37.5 | 150 to 225 |

| TCAs | ||

| Clomipramine | 10 to 25 | 100 to 300 |

| Imipramine | 10 | 100 to 300 |

| MAOI | ||

| Phenelzine | 15 | 45 to 90 |

| CR: controlled release; MAOI: monoamine oxidase inhibitor; SNRIs: serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors; SSRIs: selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors; TCAs: tricyclic antidepressants; XR: extended release Source: American Psychiatric Association. Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with panic disorder. 2nd ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2009 | ||

Treatment nonresponse. True non-response needs to be distinguished from poor response caused by inadequate treatment delivery, eg, patients not completing homework assignments in CBT or not adhering to pharmacotherapy. Asking patients about adverse effects or personal and family beliefs about treatment may reveal reasons for nonadherence.

Second-line treatments

Little data are available to guide next-step treatment options in patients who don’t achieve remission from their initial treatment. Patients who benefit from an SSRI, venlafaxine XR, or CBT but still have symptoms should be started on combination treatment. For a patient who experiences complete non-response to the initial treatment, discontinue the first treatment and switch to the other modality. In general, completely ineffective treatments should be discontinued when another treatment is added, but when partial improvement (>30%) occurs, continue the original treatment and augment it with another approach.

For patients pursuing pharmacotherapy, poor response to an adequate SSRI trial usually should lead to a switch to venlafaxine XR, and vice versa. Failure to respond to both of these medication classes should prompt a switch to a benzodiazepine or TCA.

Benzodiazepines are a fast-acting, effective treatment for PD, with efficacy similar to SSRIs in acute and long-term treatment.14 Benzodiazepines may be prescribed with antidepressants at the beginning of treatment to improve response speed.15 Clonazepam and alprazolam are FDA-approved for treating PD. A high-potency, long-acting agent, clonazepam is the preferred initial benzodiazepine, dosed 0.5 to 4 mg/d on a fixed schedule. Although substantial data support using alprazolam for PD, it requires more frequent dosing and has a greater risk of rebound anxiety and abuse potential because of its more rapid onset of action. Compared with immediate-release alprazolam, alprazolam XR has a slower absorption rate and longer steady state in the blood, but this formulation does not have lower abuse potential or greater efficacy. Although not FDA-approved for PD, diazepam and lorazepam also have proven efficacy for PD.3

Benzodiazepines should be considered contraindicated in patients with a history of substance abuse, except in select cases.4 Benzodiazepines generally should be avoided in older patients because of increased risk for falls, cognitive impairment, and motor vehicle accidents. Table 2 lists situations in which benzodiazepines may be used to treat PD.

Table 2

Clinical scenarios in which to consider using benzodiazepines

| Coadministration for 2 to 4 weeks when initiating treatment with an SSRI or venlafaxine XR to achieve more rapid relief and mitigate potential antidepressant-induced anxiety |

| For patients who wish to avoid antidepressants because of concern about sexual dysfunction |

| For patients who need chronic aspirin or an NSAID, which may increase the risk for upper gastrointestinal bleeding when taken in combination with an SSRI |

| For patients with comorbid bipolar disorder or epilepsy |

| Next-step monotherapy or augmentation in patients who respond poorly to an SSRI, venlafaxine XR, TCA, or CBT |

| CBT: cognitive-behavioral therapy; NSAID: nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug; SSRI: selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor; TCA: tricyclic antidepressant; XR: extended release |

TCAs are effective as monotherapy for PD. Most support comes from studies of imipramine or clomipramine.12 Similar to SSRIs and venlafaxine XR, use a low initial dose and gradually increase until the patient remits or side effects prevent further increases. SSRI and TCA combinations rarely are used unless the TCA is a relatively specific norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor (eg, desipramine, nortriptyline). Because TCAs are metabolized via the cytochrome P450 2D6 system and some SSRIs—particularly fluoxetine and paroxetine—strongly inhibit 2D6, combinations of TCAs with these agents may lead to dangerously high plasma TCA levels, placing patients at risk for cardiac dysrhythmias and other side effects.16

Monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs)—particularly phenelzine—are underused for PD. They have the strongest efficacy data for any class of medications outside the first- and second-line agents and have a unique mechanism of action. In patients who can comply with the dietary and medication limitations, an MAOI generally should be the next step after nonresponse to other treatments.3

Alternative treatments

For patients who do not respond to any of the treatments described above, data from uncontrolled studies support mirtazapine, levetiracetam, and the serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors duloxetine and milnacipran as monotherapy for PD.17 Pindolol—a beta blocker and 5-HT1A receptor antagonist—proved superior to placebo as an adjunctive agent to SSRIs in treatment-resistant PD in 1 of 2 trials.17 Minimal evidence supports the atypical antipsychotics risperidone and olanzapine in treatment-resistant PD, although a placebo-controlled trial of quetiapine SR coadministered with SSRIs recently was completed (NCT00619892; results pending). Atypical antipsychotics are best reserved for patients with a primary psychotic disorder or bipolar disorder who experience panic attacks.5

Panic-focused psychodynamic psychotherapy, a 12-week (approximately 24 sessions) form of psychotherapy, has demonstrated superiority vs applied relaxation therapy.18 This treatment could be considered for patients who do not respond to standard first-line treatments, but few community therapists are familiar with this method.

For many patients with PD, complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) approaches are appealing. See this article at CurrentPsychiatry.com for a Box that discusses CAM for PD.

Although no complementary and alternative medicine treatments have strong evidence of efficacy as monotherapy for panic disorder (PD), several have data that suggest benefit with little evidence of risk. These include bibliotherapy, yoga, aerobic exercise, and the dietary supplements kava and inositol.a Exercise as a treatment poses a challenge because it can induce symptoms that the patient fears, such as tachycardia and shortness of breath. In addition to any direct physiologic benefit from aerobic exercise, there is also an exposure component that can be harnessed by gradually increasing the exertion level.

Another approach undergoing extensive evaluation is Internet-provided cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT). Using guided CBT modules with or without therapist support, Internet-provided CBT provides an option for motivated patients unable to complete in-person CBT because of logistical factors.b A helpful resource that reviews Internet self-help and psychotherapy guided programs for PD and other psychiatric conditions is http://beacon.anu.edu.au.

References

a. Antonacci DJ, Davis E, Bloch RM, et al. CAM for your anxious patient: what the evidence says. Current Psychiatry. 2010;9(10):42-52.

b. Johnston L, Titov N, Andrews G, et al. A RCT of a transdiagnostic internet-delivered treatment for three anxiety disorders: examination of support roles and disorder-specific outcomes. PLoS One. 2011;6(11):e28079.

Maintenance treatment

Patients who complete a course of CBT for PD often follow up with several “booster sessions” at monthly or longer intervals that focus on relapse prevention techniques. Few controlled trials have evaluated pharmacotherapy discontinuation in PD. Most guidelines recommend continuing treatment for ≥1 year after achieving remission to minimize the risk of relapse.3 Researchers are focusing on whether medication dosage can be reduced during maintenance without loss of efficacy.

Treatment discontinuation

In the absence of urgent medical need, taper medications for PD gradually over several months. PD patients are highly sensitive to unusual physical sensations, which can occur while discontinuing antidepressants or benzodiazepines. If a benzodiazepine is used in conjunction with an antidepressant, the benzodiazepine should be discontinued first, so that the antidepressant can help ease benzodiazepine-associated discontinuation symptoms. A brief course of CBT during pharmacotherapy discontinuation may increase the likelihood of successful tapering.19

CASE CONTINUED: A successful switch

Ms. K has to discontinue sequential trials of fluoxetine, 40 mg/d, and venlafaxine XR, 225 mg/d because of side effects, and she does not reduce the frequency of her alprazolam use. She agrees to switch from alprazolam to clonazepam, 0.5 mg every morning and 1 mg at bedtime, and to start CBT. Clonazepam reduces her anxiety sufficiently so she can address her symptoms in therapy. Through CBT she becomes motivated to monitor her thoughts and treat them as guesses rather than facts, reviewing the evidence for her thoughts and generating rational responses. She participates in exposure exercises, which she practices between sessions, and grows to tolerate uncomfortable sensations until they no longer signal danger. After 12 CBT sessions, she is panic-free. Despite some trepidation, she agrees to a slow taper off clonazepam, reducing the dose by 0.25 mg every 2 weeks. She continues booster sessions with her therapist to manage any re-emerging anxiety. After an additional 12 weeks, she successfully discontinues clonazepam and remains panic-free.

Related Resources

- American Psychiatric Association. Panic disorder. http://healthyminds.org/Main-Topic/Panic-Disorder.aspx.

- Anxiety and Depression Association of America. Panic disorder & agoraphobia. http://adaa.org/understanding-anxiety/panic-disorder-agoraphobia.

- Mayo Clinic. Panic attacks and panic disorder. www.mayoclinic.com/health/panic-attacks/DS00338.

- National Health Service Self-Help Guides. www.ntw.nhs.uk/pic/selfhelp.

- National Institute of Mental Health. Panic disorder. www.nimh.nih.gov/health/topics/panic-disorder/index.shtml.

Drug Brand Names

- Alprazolam • Xanax

- Alprazolam XR • Xanax XR

- Citalopram • Celexa

- Clomipramine • Anafranil

- Clonazepam • Klonopin

- Desipramine • Norpramin

- Diazepam • Valium

- Duloxetine • Cymbalta

- Escitalopram • Lexapro

- Fluoxetine • Prozac

- Fluvoxamine • Luvox

- Imipramine • Tofranil

- Levetiracetam • Keppra

- Lorazepam • Ativan

- Milnacipran • Savella

- Mirtazapine • Remeron

- Nortriptyline • Aventyl, Pamelor

- Olanzapine • Zyprexa

- Paroxetine • Paxil

- Paroxetine CR • Paxil CR

- Phenelzine • Nardil

- Pindolol • Visken

- Quetiapine SR • Seroquel SR

- Risperidone • Risperdal

- Sertraline • Zoloft

- Venlafaxine XR • Effexor XR

Disclosures

Dr. Dunlop receives research support from Bristol-Myers Squibb, GlaxoSmithKline, and the National Institute of Mental Health. He serves as a consultant to MedAvante and Roche.

Ms. Schneider and Dr. Gerardi report no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. Roy-Byrne PP, Craske MG, Stein MB. Panic disorder. Lancet. 2006;368(9540):1023-1032.

2. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 4th ed, text rev. Washington DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2000.

3. American Psychiatric Association. Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with panic disorder. 2nd ed. Washington DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2009.

4. Dunlop BW, Davis PG. Combination treatment with benzodiazepines and SSRIs for comorbid anxiety and depression: a review. Prim Care Companion J Clin Psychiatry. 2008;10(3):222-228.

5. Rakofsky JJ, Dunlop BW. Treating nonspecific anxiety and anxiety disorders in patients with bipolar disorder: a review. J Clin Psychiatry. 2011;72(1):81-90.

6. Sareen J, Cox BJ, Afifi TO, et al. Anxiety disorders and risk for suicidal ideation and suicide attempts: a population-based longitudinal study of adults. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62(11):1249-1257.

7. Houck PR, Spiegel DA, Shear MK, et al. Reliability of the self-report version of the panic disorder severity scale. Depress Anxiety. 2002;15(4):183-185.

8. Ninan PT, Dunlop BW. Neurobiology and etiology of panic disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 2005;66(suppl 4):3-7.

9. Furukawa TA, Watanabe N, Churchill R. Psychotherapy plus antidepressant for panic disorder with or without agoraphobia: systematic review. Br J Psychiatry. 2006;188:305-312.

10. Barlow DH, Gorman JM, Shear MK, et al. Cognitive-behavioral therapy, imipramine, or their combination for panic disorder: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2000;283(19):2529-2536.

11. van Apeldoorn FJ, Timmerman ME, Mersch PP, et al. A randomized trial of cognitive-behavioral therapy or selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor or both combined for panic disorder with or without agoraphobia: treatment results through 1-year follow-up. J Clin Psychiatry. 2010;71(5):574-586.

12. Bakker A, van Balkom AJ, Spinhoven P. SSRIs vs. TCAs in the treatment of panic disorder: a meta-analysis. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2002;106(3):163-167.

13. Bandelow B, Behnke K, Lenoir S, et al. Sertraline versus paroxetine in the treatment of panic disorder: an acute, double-blind noninferiority comparison. J Clin Psychiatry. 2004;65(3):405-413.

14. Nardi AE, Freire RC, Mochcovitch MD, et al. A randomized, naturalistic, parallel-group study for the long-term treatment of panic disorder with clonazepam or paroxetine. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2012;32(1):120-126.

15. Goddard AW, Brouette T, Almai A, et al. Early coadministration of clonazepam with sertraline for panic disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2001;58(7):681-686.

16. Preskorn SH, Shah R, Neff M, et al. The potential for clinically significant drug-drug interactions involving the CYP 2D6 system: effects with fluoxetine and paroxetine versus sertraline. J Psychiatr Pract. 2007;13(1):5-12.

17. Perna G, Guerriero G, Caldirola D. Emerging drugs for panic disorder. Expert Opin Emerg Drugs. 2011;16(4):631-645.

18. Milrod B, Leon AC, Busch F, et al. A randomized controlled clinical trial of psychoanalytic psychotherapy for panic disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2007;164(2):265-272.

19. Otto MW, Pollack MH, Sachs GS, et al. Discontinuation of benzodiazepine treatment: efficacy of cognitive-behavioral therapy for patients with panic disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 1993;150(10):1485-1490.

Ms. K, a 24-year-old waitress who lives with her boyfriend, was referred by her primary care physician for evaluation of panic attacks that began “out of nowhere” at work approximately 6 months ago. The unpredictable attacks occur multiple times per week, causing her to leave work and cancel shifts.

Ms. K reports that before the panic attacks began, she felt happy in her relationship, enjoyed hobbies, and was hopeful about the future. However, she has become concerned that a potentially catastrophic illness is causing her panic attacks. She researches her symptoms on the Internet, and is preoccupied with the possibility of sudden death due to an undiagnosed heart condition. Multiple visits to the emergency room have not identified any physical abnormalities. Her primary care doctor prescribed alprazolam, 0.5 mg as needed for panic attacks, which she reports is helpful, “but only in the moment of the attacks.” Ms. K avoids alcohol and illicit substances and limits her caffeine intake. She is not willing to accept that her life “feels so limited.” Her dream of earning a nursing degree and eventually starting a family now seems unattainable.

Panic disorder (PD) occurs in 3% to 5% of adults, with women affected at roughly twice the rate of men.1 Causing a broad range of distress and varying degrees of impairment, PD commonly occurs with other psychiatric disorders. For most patients, treatment is effective, but those who do not respond to initial approaches require a thoughtful, stepped approach to care. Key considerations include establishing an accurate diagnosis, clarifying comorbid illnesses, ascertaining patient beliefs and expectations, and providing appropriately dosed and maintained treatments.

Panic attacks vs PD

Panic attacks consist of rapid onset of intense anxiety, with prominent somatic symptoms, that peaks within 10 minutes (Figure).2 Attacks in which <4 of the listed symptoms occur are considered limited-symptom panic attacks.

Figure: Body locations of panic attack symptoms

Diagnosis of a panic attack requires the sudden development of intense fear or discomfort characterized by ≥4 of the 13 symptoms listed above that peaks in intensity within 10 minutes of onset

Source: Reference 2

Panic attacks can occur with various disorders, including other anxiety disorders, mood disorders, and substance intoxication or withdrawal. Because serious medical conditions can present with panic-like symptoms, the initial occurrence of such symptoms warrants consideration of physiological causes. For a Box2 that describes the differential diagnosis of panic attacks, see this article at CurrentPsychiatry.com.

To meet diagnostic criteria for panic disorder, panic attacks must initially occur “out of the blue,” meaning no specific object or situation induced the attack. The differential diagnosis of panic attacks includes assessing for other psychiatric disorders that may involve panic attacks. Evaluation requires considering the context in which the panic attacks occur, including their start date, pattern of attacks, instigating situations, and associated thoughts.

Social phobia. Attacks occur only during or immediately before a social interaction in which the patient fears embarrassing himself or herself.

Obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD). Attacks occur when the patient cannot avoid exposure to an obsessional fear or is prevented from performing a ritual that diffuses obsessional anxiety.

Posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Attacks occur when confronted by a trauma-related memory or trigger.

Specific phobia. Attacks occur only when the patient encounters a specifically feared object, place, or situation, unrelated to social phobia, OCD, or PTSD.

Medical conditions. Conditions to consider include—but are not limited to—hyperthyroidism, pulmonary embolism, myocardial infarction, cardiac dysrhythmias, hypoglycemia, asthma, partial complex seizures, and pheochromocytoma.

Source: Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 4th ed, text rev. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2000

A PD diagnosis requires that repeated panic attacks initially must occur from “out of the blue,” meaning no specific object or situation induced the attack. In addition, the diagnosis requires 1 of 3 types of psychological or behavioral changes as a result of the attacks (Table 1).2 Agoraphobia is diagnosed if 1 of the behavioral changes is avoidance of places or situations from which escape might be embarrassing or difficult should an attack occur. A patient can be diagnosed as having PD with agoraphobia, PD without agoraphobia, or agoraphobia without PD (ie, experiences only limited symptom panic attacks, but avoids situations or stimuli associated with them).

Table 1

Definitions of panic disorder and agoraphobia

| Panic disorder |

|---|

|

| Agoraphobia |

| Anxiety about, or avoidance of, being in places or situations from which escape might be difficult or embarrassing, or in which help may not be available in the event of having an unexpected or situationally predisposed panic attack or panic-like symptoms. Agoraphobic fears typically involve characteristic clusters of situations that include being outside the home alone, being in a crowd, standing in a line, being on a bridge, or traveling in a bus, train, or automobile |

| Source: Reference 2 |

Comorbidities are common in patients with PD and predict greater difficulty achieving remission (Box).1,3-6

The most common psychiatric conditions that co-occur with panic disorder (PD) are other anxiety disorders, mood disorders, personality disorders, and substance use disorders.1 Carefully assess the severity and degree of impairment or distress arising from each condition to prioritize treatment goals. For example, treating panic attacks would be a lower priority in a patient with untreated bipolar disorder.

Assessing comorbid substance abuse is important in selecting PD treatments. Benzodiazepines should almost always be avoided in patients with a history of drug abuse—illicit or prescribed. Although complete abstinence should not be a prerequisite for beginning PD treatment, detoxification and concomitant substance abuse treatment are essential.3

Comorbid mood disorders also affect the course of PD treatment. Antidepressants are effective for treating depression and PD, whereas benzodiazepines are not effective for depression.4 Antidepressants in patients with bipolar disorder are controversial because these medications might induce mixed or elevated mood states or rapid cycling. In these complicated patients, consider antidepressants lower in the treatment algorithm.5

Other conditions to consider before beginning treatment include pregnancy or the possibility of becoming pregnant in the near future and suicidal ideation. PD is associated with increased risk for suicidal ideation and progression to suicide attempts, particularly in patients with a comorbid mood or psychotic disorder.6 In addition, consider the potential impact of medications on comorbid medical conditions.

Treatment begins with education

The goal of treatment is remission of symptoms, ideally including an absence of panic attacks, agoraphobic avoidance, and anticipatory anxiety.1 The Panic Disorder Severity Scale self-report is a validated measure of panic symptoms that may be useful in clinical practice.7

The first step in treatment is educating patients about panic attacks, framing them as an overreactive fear circuit in the brain that produces physical symptoms that are not dangerous. Using a brain model that shows the location of the amygdala, hippocampus, and prefrontal cortex—which play crucial roles in generating and controlling anxiety and fear—can make this discussion more concrete.8 Although highly simplified, such models allow clinicians to demonstrate that excessive reactivity of limbic regions can be reduced by both top-down (cortico-limbic connections via cognitive-behavioral therapy [CBT]) and bottom-up (pharmacotherapy directly acting on limbic structures) approaches. Such discussions lead to treatment recommendations for CBT, pharmacotherapy, or their combination.

No single treatment has emerged as the definitive “best” for PD, and no reliable predictors can guide specific treatment for an individual.3 Combining CBT with pharmacotherapy produces higher short-term response rates than either treatment alone, but in the long term, combination treatment does not appear to be superior to CBT alone.9 Base the initial treatment selection for PD on patient preference, treatment availability and cost, and comorbid medical and psychiatric conditions. For an Algorithm to guide treatment decisions, see this article at CurrentPsychiatry.com.

Algorithm: Treatment for panic disorder: A suggested algorithm

aPoor response to an SSRI should lead to a switch to venlafaxine extended-release, and vice versa

bBenzodiazepines are relatively contraindicated in geriatric patients and patients with a history of substance abuse or dependence

CBT: cognitive-behavioral therapy; MAOI: monoamine oxidase inhibitor; SSRI: selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor; TCA: tricyclic antidepressant; Ven XR: venlafaxine extended-release

First-line treatments

Psychotherapy. CBT is the most efficacious psychotherapy for PD. Twelve to 15 sessions of CBT has demonstrated efficacy for PD, with additional effects on comorbid anxiety and depressive symptoms.10 No large clinical trials of CBT have used cognitive restructuring alone; all have included at least some component of exposure that requires the patient to confront feared physical sensations. Gains during treatment may be steady and gradual or sudden and uneven, with rapid improvement in some but not all symptoms. CBT and pharmacotherapy have demonstrated similar levels of benefit in short-term trials, but CBT has proven superior in most9 but not all11 trials evaluating long-term outcomes, particularly compared with pharmacotherapy that is discontinued during follow-up. Although less studied, group CBT also may be considered if a patient cannot afford individual CBT.

Pharmacotherapy. Evidence supports selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), venlafaxine extended-release (XR), benzodiazepines, and tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs) as effective treatments for PD.3 No class of medication has demonstrated superiority over others in short-term treatment.3,12 Because of the medical risks associated with benzodiazepines and TCAs, an SSRI or venlafaxine XR should be the first medication option for most patients. Fluoxetine, paroxetine, sertraline, and venlafaxine XR are FDA-approved for PD. Paroxetine is associated with weight gain and may increase the risk for panic recurrence upon discontinuation more than sertraline, making it a less favorable option for many patients.13 Start doses at half the normal starting dose used for treating major depressive disorder and continue for 4 to 7 days, then increase to the minimal effective dose. For a Table3 that lists dosing recommendations for antidepressants to treat PD, see this article at CurrentPsychiatry.com. If there is no improvement by 4 weeks, increase the dose every 2 to 4 weeks until remission is achieved or side effects prevent further dose increases.

Table

Recommended doses for antidepressants used to treat panic disorder

| Medication | Starting dose (mg/d) | Therapeutic range (mg/d) |

|---|---|---|

| SSRIs | ||

| Citalopram | 10 | 20 to 40 |

| Escitalopram | 5 | 10 to 40 |

| Fluoxetine | 5 to 10 | 20 to 80 |

| Fluvoxamine | 25 | 100 to 300 |

| Paroxetine | 10 | 20 to 80 |

| Paroxetine CR | 12.5 | 25 to 50 |

| Sertraline | 25 | 100 to 200 |

| SNRIs | ||

| Duloxetine | 20 to 30 | 60 to 120 |

| Venlafaxine XR | 37.5 | 150 to 225 |

| TCAs | ||

| Clomipramine | 10 to 25 | 100 to 300 |

| Imipramine | 10 | 100 to 300 |

| MAOI | ||

| Phenelzine | 15 | 45 to 90 |

| CR: controlled release; MAOI: monoamine oxidase inhibitor; SNRIs: serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors; SSRIs: selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors; TCAs: tricyclic antidepressants; XR: extended release Source: American Psychiatric Association. Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with panic disorder. 2nd ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2009 | ||

Treatment nonresponse. True non-response needs to be distinguished from poor response caused by inadequate treatment delivery, eg, patients not completing homework assignments in CBT or not adhering to pharmacotherapy. Asking patients about adverse effects or personal and family beliefs about treatment may reveal reasons for nonadherence.

Second-line treatments

Little data are available to guide next-step treatment options in patients who don’t achieve remission from their initial treatment. Patients who benefit from an SSRI, venlafaxine XR, or CBT but still have symptoms should be started on combination treatment. For a patient who experiences complete non-response to the initial treatment, discontinue the first treatment and switch to the other modality. In general, completely ineffective treatments should be discontinued when another treatment is added, but when partial improvement (>30%) occurs, continue the original treatment and augment it with another approach.

For patients pursuing pharmacotherapy, poor response to an adequate SSRI trial usually should lead to a switch to venlafaxine XR, and vice versa. Failure to respond to both of these medication classes should prompt a switch to a benzodiazepine or TCA.

Benzodiazepines are a fast-acting, effective treatment for PD, with efficacy similar to SSRIs in acute and long-term treatment.14 Benzodiazepines may be prescribed with antidepressants at the beginning of treatment to improve response speed.15 Clonazepam and alprazolam are FDA-approved for treating PD. A high-potency, long-acting agent, clonazepam is the preferred initial benzodiazepine, dosed 0.5 to 4 mg/d on a fixed schedule. Although substantial data support using alprazolam for PD, it requires more frequent dosing and has a greater risk of rebound anxiety and abuse potential because of its more rapid onset of action. Compared with immediate-release alprazolam, alprazolam XR has a slower absorption rate and longer steady state in the blood, but this formulation does not have lower abuse potential or greater efficacy. Although not FDA-approved for PD, diazepam and lorazepam also have proven efficacy for PD.3

Benzodiazepines should be considered contraindicated in patients with a history of substance abuse, except in select cases.4 Benzodiazepines generally should be avoided in older patients because of increased risk for falls, cognitive impairment, and motor vehicle accidents. Table 2 lists situations in which benzodiazepines may be used to treat PD.

Table 2

Clinical scenarios in which to consider using benzodiazepines

| Coadministration for 2 to 4 weeks when initiating treatment with an SSRI or venlafaxine XR to achieve more rapid relief and mitigate potential antidepressant-induced anxiety |

| For patients who wish to avoid antidepressants because of concern about sexual dysfunction |

| For patients who need chronic aspirin or an NSAID, which may increase the risk for upper gastrointestinal bleeding when taken in combination with an SSRI |

| For patients with comorbid bipolar disorder or epilepsy |

| Next-step monotherapy or augmentation in patients who respond poorly to an SSRI, venlafaxine XR, TCA, or CBT |

| CBT: cognitive-behavioral therapy; NSAID: nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug; SSRI: selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor; TCA: tricyclic antidepressant; XR: extended release |

TCAs are effective as monotherapy for PD. Most support comes from studies of imipramine or clomipramine.12 Similar to SSRIs and venlafaxine XR, use a low initial dose and gradually increase until the patient remits or side effects prevent further increases. SSRI and TCA combinations rarely are used unless the TCA is a relatively specific norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor (eg, desipramine, nortriptyline). Because TCAs are metabolized via the cytochrome P450 2D6 system and some SSRIs—particularly fluoxetine and paroxetine—strongly inhibit 2D6, combinations of TCAs with these agents may lead to dangerously high plasma TCA levels, placing patients at risk for cardiac dysrhythmias and other side effects.16

Monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs)—particularly phenelzine—are underused for PD. They have the strongest efficacy data for any class of medications outside the first- and second-line agents and have a unique mechanism of action. In patients who can comply with the dietary and medication limitations, an MAOI generally should be the next step after nonresponse to other treatments.3

Alternative treatments

For patients who do not respond to any of the treatments described above, data from uncontrolled studies support mirtazapine, levetiracetam, and the serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors duloxetine and milnacipran as monotherapy for PD.17 Pindolol—a beta blocker and 5-HT1A receptor antagonist—proved superior to placebo as an adjunctive agent to SSRIs in treatment-resistant PD in 1 of 2 trials.17 Minimal evidence supports the atypical antipsychotics risperidone and olanzapine in treatment-resistant PD, although a placebo-controlled trial of quetiapine SR coadministered with SSRIs recently was completed (NCT00619892; results pending). Atypical antipsychotics are best reserved for patients with a primary psychotic disorder or bipolar disorder who experience panic attacks.5

Panic-focused psychodynamic psychotherapy, a 12-week (approximately 24 sessions) form of psychotherapy, has demonstrated superiority vs applied relaxation therapy.18 This treatment could be considered for patients who do not respond to standard first-line treatments, but few community therapists are familiar with this method.

For many patients with PD, complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) approaches are appealing. See this article at CurrentPsychiatry.com for a Box that discusses CAM for PD.

Although no complementary and alternative medicine treatments have strong evidence of efficacy as monotherapy for panic disorder (PD), several have data that suggest benefit with little evidence of risk. These include bibliotherapy, yoga, aerobic exercise, and the dietary supplements kava and inositol.a Exercise as a treatment poses a challenge because it can induce symptoms that the patient fears, such as tachycardia and shortness of breath. In addition to any direct physiologic benefit from aerobic exercise, there is also an exposure component that can be harnessed by gradually increasing the exertion level.

Another approach undergoing extensive evaluation is Internet-provided cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT). Using guided CBT modules with or without therapist support, Internet-provided CBT provides an option for motivated patients unable to complete in-person CBT because of logistical factors.b A helpful resource that reviews Internet self-help and psychotherapy guided programs for PD and other psychiatric conditions is http://beacon.anu.edu.au.

References

a. Antonacci DJ, Davis E, Bloch RM, et al. CAM for your anxious patient: what the evidence says. Current Psychiatry. 2010;9(10):42-52.

b. Johnston L, Titov N, Andrews G, et al. A RCT of a transdiagnostic internet-delivered treatment for three anxiety disorders: examination of support roles and disorder-specific outcomes. PLoS One. 2011;6(11):e28079.

Maintenance treatment

Patients who complete a course of CBT for PD often follow up with several “booster sessions” at monthly or longer intervals that focus on relapse prevention techniques. Few controlled trials have evaluated pharmacotherapy discontinuation in PD. Most guidelines recommend continuing treatment for ≥1 year after achieving remission to minimize the risk of relapse.3 Researchers are focusing on whether medication dosage can be reduced during maintenance without loss of efficacy.

Treatment discontinuation

In the absence of urgent medical need, taper medications for PD gradually over several months. PD patients are highly sensitive to unusual physical sensations, which can occur while discontinuing antidepressants or benzodiazepines. If a benzodiazepine is used in conjunction with an antidepressant, the benzodiazepine should be discontinued first, so that the antidepressant can help ease benzodiazepine-associated discontinuation symptoms. A brief course of CBT during pharmacotherapy discontinuation may increase the likelihood of successful tapering.19

CASE CONTINUED: A successful switch

Ms. K has to discontinue sequential trials of fluoxetine, 40 mg/d, and venlafaxine XR, 225 mg/d because of side effects, and she does not reduce the frequency of her alprazolam use. She agrees to switch from alprazolam to clonazepam, 0.5 mg every morning and 1 mg at bedtime, and to start CBT. Clonazepam reduces her anxiety sufficiently so she can address her symptoms in therapy. Through CBT she becomes motivated to monitor her thoughts and treat them as guesses rather than facts, reviewing the evidence for her thoughts and generating rational responses. She participates in exposure exercises, which she practices between sessions, and grows to tolerate uncomfortable sensations until they no longer signal danger. After 12 CBT sessions, she is panic-free. Despite some trepidation, she agrees to a slow taper off clonazepam, reducing the dose by 0.25 mg every 2 weeks. She continues booster sessions with her therapist to manage any re-emerging anxiety. After an additional 12 weeks, she successfully discontinues clonazepam and remains panic-free.

Related Resources

- American Psychiatric Association. Panic disorder. http://healthyminds.org/Main-Topic/Panic-Disorder.aspx.

- Anxiety and Depression Association of America. Panic disorder & agoraphobia. http://adaa.org/understanding-anxiety/panic-disorder-agoraphobia.

- Mayo Clinic. Panic attacks and panic disorder. www.mayoclinic.com/health/panic-attacks/DS00338.

- National Health Service Self-Help Guides. www.ntw.nhs.uk/pic/selfhelp.

- National Institute of Mental Health. Panic disorder. www.nimh.nih.gov/health/topics/panic-disorder/index.shtml.

Drug Brand Names

- Alprazolam • Xanax

- Alprazolam XR • Xanax XR

- Citalopram • Celexa

- Clomipramine • Anafranil

- Clonazepam • Klonopin

- Desipramine • Norpramin

- Diazepam • Valium

- Duloxetine • Cymbalta

- Escitalopram • Lexapro

- Fluoxetine • Prozac

- Fluvoxamine • Luvox

- Imipramine • Tofranil

- Levetiracetam • Keppra

- Lorazepam • Ativan

- Milnacipran • Savella

- Mirtazapine • Remeron

- Nortriptyline • Aventyl, Pamelor

- Olanzapine • Zyprexa

- Paroxetine • Paxil

- Paroxetine CR • Paxil CR

- Phenelzine • Nardil

- Pindolol • Visken

- Quetiapine SR • Seroquel SR

- Risperidone • Risperdal

- Sertraline • Zoloft

- Venlafaxine XR • Effexor XR

Disclosures

Dr. Dunlop receives research support from Bristol-Myers Squibb, GlaxoSmithKline, and the National Institute of Mental Health. He serves as a consultant to MedAvante and Roche.

Ms. Schneider and Dr. Gerardi report no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

Ms. K, a 24-year-old waitress who lives with her boyfriend, was referred by her primary care physician for evaluation of panic attacks that began “out of nowhere” at work approximately 6 months ago. The unpredictable attacks occur multiple times per week, causing her to leave work and cancel shifts.

Ms. K reports that before the panic attacks began, she felt happy in her relationship, enjoyed hobbies, and was hopeful about the future. However, she has become concerned that a potentially catastrophic illness is causing her panic attacks. She researches her symptoms on the Internet, and is preoccupied with the possibility of sudden death due to an undiagnosed heart condition. Multiple visits to the emergency room have not identified any physical abnormalities. Her primary care doctor prescribed alprazolam, 0.5 mg as needed for panic attacks, which she reports is helpful, “but only in the moment of the attacks.” Ms. K avoids alcohol and illicit substances and limits her caffeine intake. She is not willing to accept that her life “feels so limited.” Her dream of earning a nursing degree and eventually starting a family now seems unattainable.

Panic disorder (PD) occurs in 3% to 5% of adults, with women affected at roughly twice the rate of men.1 Causing a broad range of distress and varying degrees of impairment, PD commonly occurs with other psychiatric disorders. For most patients, treatment is effective, but those who do not respond to initial approaches require a thoughtful, stepped approach to care. Key considerations include establishing an accurate diagnosis, clarifying comorbid illnesses, ascertaining patient beliefs and expectations, and providing appropriately dosed and maintained treatments.

Panic attacks vs PD

Panic attacks consist of rapid onset of intense anxiety, with prominent somatic symptoms, that peaks within 10 minutes (Figure).2 Attacks in which <4 of the listed symptoms occur are considered limited-symptom panic attacks.

Figure: Body locations of panic attack symptoms

Diagnosis of a panic attack requires the sudden development of intense fear or discomfort characterized by ≥4 of the 13 symptoms listed above that peaks in intensity within 10 minutes of onset

Source: Reference 2

Panic attacks can occur with various disorders, including other anxiety disorders, mood disorders, and substance intoxication or withdrawal. Because serious medical conditions can present with panic-like symptoms, the initial occurrence of such symptoms warrants consideration of physiological causes. For a Box2 that describes the differential diagnosis of panic attacks, see this article at CurrentPsychiatry.com.

To meet diagnostic criteria for panic disorder, panic attacks must initially occur “out of the blue,” meaning no specific object or situation induced the attack. The differential diagnosis of panic attacks includes assessing for other psychiatric disorders that may involve panic attacks. Evaluation requires considering the context in which the panic attacks occur, including their start date, pattern of attacks, instigating situations, and associated thoughts.

Social phobia. Attacks occur only during or immediately before a social interaction in which the patient fears embarrassing himself or herself.

Obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD). Attacks occur when the patient cannot avoid exposure to an obsessional fear or is prevented from performing a ritual that diffuses obsessional anxiety.

Posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Attacks occur when confronted by a trauma-related memory or trigger.

Specific phobia. Attacks occur only when the patient encounters a specifically feared object, place, or situation, unrelated to social phobia, OCD, or PTSD.

Medical conditions. Conditions to consider include—but are not limited to—hyperthyroidism, pulmonary embolism, myocardial infarction, cardiac dysrhythmias, hypoglycemia, asthma, partial complex seizures, and pheochromocytoma.

Source: Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 4th ed, text rev. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2000

A PD diagnosis requires that repeated panic attacks initially must occur from “out of the blue,” meaning no specific object or situation induced the attack. In addition, the diagnosis requires 1 of 3 types of psychological or behavioral changes as a result of the attacks (Table 1).2 Agoraphobia is diagnosed if 1 of the behavioral changes is avoidance of places or situations from which escape might be embarrassing or difficult should an attack occur. A patient can be diagnosed as having PD with agoraphobia, PD without agoraphobia, or agoraphobia without PD (ie, experiences only limited symptom panic attacks, but avoids situations or stimuli associated with them).

Table 1

Definitions of panic disorder and agoraphobia

| Panic disorder |

|---|

|

| Agoraphobia |

| Anxiety about, or avoidance of, being in places or situations from which escape might be difficult or embarrassing, or in which help may not be available in the event of having an unexpected or situationally predisposed panic attack or panic-like symptoms. Agoraphobic fears typically involve characteristic clusters of situations that include being outside the home alone, being in a crowd, standing in a line, being on a bridge, or traveling in a bus, train, or automobile |

| Source: Reference 2 |

Comorbidities are common in patients with PD and predict greater difficulty achieving remission (Box).1,3-6

The most common psychiatric conditions that co-occur with panic disorder (PD) are other anxiety disorders, mood disorders, personality disorders, and substance use disorders.1 Carefully assess the severity and degree of impairment or distress arising from each condition to prioritize treatment goals. For example, treating panic attacks would be a lower priority in a patient with untreated bipolar disorder.

Assessing comorbid substance abuse is important in selecting PD treatments. Benzodiazepines should almost always be avoided in patients with a history of drug abuse—illicit or prescribed. Although complete abstinence should not be a prerequisite for beginning PD treatment, detoxification and concomitant substance abuse treatment are essential.3

Comorbid mood disorders also affect the course of PD treatment. Antidepressants are effective for treating depression and PD, whereas benzodiazepines are not effective for depression.4 Antidepressants in patients with bipolar disorder are controversial because these medications might induce mixed or elevated mood states or rapid cycling. In these complicated patients, consider antidepressants lower in the treatment algorithm.5

Other conditions to consider before beginning treatment include pregnancy or the possibility of becoming pregnant in the near future and suicidal ideation. PD is associated with increased risk for suicidal ideation and progression to suicide attempts, particularly in patients with a comorbid mood or psychotic disorder.6 In addition, consider the potential impact of medications on comorbid medical conditions.

Treatment begins with education

The goal of treatment is remission of symptoms, ideally including an absence of panic attacks, agoraphobic avoidance, and anticipatory anxiety.1 The Panic Disorder Severity Scale self-report is a validated measure of panic symptoms that may be useful in clinical practice.7

The first step in treatment is educating patients about panic attacks, framing them as an overreactive fear circuit in the brain that produces physical symptoms that are not dangerous. Using a brain model that shows the location of the amygdala, hippocampus, and prefrontal cortex—which play crucial roles in generating and controlling anxiety and fear—can make this discussion more concrete.8 Although highly simplified, such models allow clinicians to demonstrate that excessive reactivity of limbic regions can be reduced by both top-down (cortico-limbic connections via cognitive-behavioral therapy [CBT]) and bottom-up (pharmacotherapy directly acting on limbic structures) approaches. Such discussions lead to treatment recommendations for CBT, pharmacotherapy, or their combination.

No single treatment has emerged as the definitive “best” for PD, and no reliable predictors can guide specific treatment for an individual.3 Combining CBT with pharmacotherapy produces higher short-term response rates than either treatment alone, but in the long term, combination treatment does not appear to be superior to CBT alone.9 Base the initial treatment selection for PD on patient preference, treatment availability and cost, and comorbid medical and psychiatric conditions. For an Algorithm to guide treatment decisions, see this article at CurrentPsychiatry.com.

Algorithm: Treatment for panic disorder: A suggested algorithm

aPoor response to an SSRI should lead to a switch to venlafaxine extended-release, and vice versa

bBenzodiazepines are relatively contraindicated in geriatric patients and patients with a history of substance abuse or dependence

CBT: cognitive-behavioral therapy; MAOI: monoamine oxidase inhibitor; SSRI: selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor; TCA: tricyclic antidepressant; Ven XR: venlafaxine extended-release

First-line treatments

Psychotherapy. CBT is the most efficacious psychotherapy for PD. Twelve to 15 sessions of CBT has demonstrated efficacy for PD, with additional effects on comorbid anxiety and depressive symptoms.10 No large clinical trials of CBT have used cognitive restructuring alone; all have included at least some component of exposure that requires the patient to confront feared physical sensations. Gains during treatment may be steady and gradual or sudden and uneven, with rapid improvement in some but not all symptoms. CBT and pharmacotherapy have demonstrated similar levels of benefit in short-term trials, but CBT has proven superior in most9 but not all11 trials evaluating long-term outcomes, particularly compared with pharmacotherapy that is discontinued during follow-up. Although less studied, group CBT also may be considered if a patient cannot afford individual CBT.

Pharmacotherapy. Evidence supports selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), venlafaxine extended-release (XR), benzodiazepines, and tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs) as effective treatments for PD.3 No class of medication has demonstrated superiority over others in short-term treatment.3,12 Because of the medical risks associated with benzodiazepines and TCAs, an SSRI or venlafaxine XR should be the first medication option for most patients. Fluoxetine, paroxetine, sertraline, and venlafaxine XR are FDA-approved for PD. Paroxetine is associated with weight gain and may increase the risk for panic recurrence upon discontinuation more than sertraline, making it a less favorable option for many patients.13 Start doses at half the normal starting dose used for treating major depressive disorder and continue for 4 to 7 days, then increase to the minimal effective dose. For a Table3 that lists dosing recommendations for antidepressants to treat PD, see this article at CurrentPsychiatry.com. If there is no improvement by 4 weeks, increase the dose every 2 to 4 weeks until remission is achieved or side effects prevent further dose increases.

Table

Recommended doses for antidepressants used to treat panic disorder

| Medication | Starting dose (mg/d) | Therapeutic range (mg/d) |

|---|---|---|

| SSRIs | ||

| Citalopram | 10 | 20 to 40 |

| Escitalopram | 5 | 10 to 40 |

| Fluoxetine | 5 to 10 | 20 to 80 |

| Fluvoxamine | 25 | 100 to 300 |

| Paroxetine | 10 | 20 to 80 |

| Paroxetine CR | 12.5 | 25 to 50 |

| Sertraline | 25 | 100 to 200 |

| SNRIs | ||

| Duloxetine | 20 to 30 | 60 to 120 |

| Venlafaxine XR | 37.5 | 150 to 225 |

| TCAs | ||

| Clomipramine | 10 to 25 | 100 to 300 |

| Imipramine | 10 | 100 to 300 |

| MAOI | ||

| Phenelzine | 15 | 45 to 90 |

| CR: controlled release; MAOI: monoamine oxidase inhibitor; SNRIs: serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors; SSRIs: selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors; TCAs: tricyclic antidepressants; XR: extended release Source: American Psychiatric Association. Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with panic disorder. 2nd ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2009 | ||

Treatment nonresponse. True non-response needs to be distinguished from poor response caused by inadequate treatment delivery, eg, patients not completing homework assignments in CBT or not adhering to pharmacotherapy. Asking patients about adverse effects or personal and family beliefs about treatment may reveal reasons for nonadherence.

Second-line treatments

Little data are available to guide next-step treatment options in patients who don’t achieve remission from their initial treatment. Patients who benefit from an SSRI, venlafaxine XR, or CBT but still have symptoms should be started on combination treatment. For a patient who experiences complete non-response to the initial treatment, discontinue the first treatment and switch to the other modality. In general, completely ineffective treatments should be discontinued when another treatment is added, but when partial improvement (>30%) occurs, continue the original treatment and augment it with another approach.

For patients pursuing pharmacotherapy, poor response to an adequate SSRI trial usually should lead to a switch to venlafaxine XR, and vice versa. Failure to respond to both of these medication classes should prompt a switch to a benzodiazepine or TCA.

Benzodiazepines are a fast-acting, effective treatment for PD, with efficacy similar to SSRIs in acute and long-term treatment.14 Benzodiazepines may be prescribed with antidepressants at the beginning of treatment to improve response speed.15 Clonazepam and alprazolam are FDA-approved for treating PD. A high-potency, long-acting agent, clonazepam is the preferred initial benzodiazepine, dosed 0.5 to 4 mg/d on a fixed schedule. Although substantial data support using alprazolam for PD, it requires more frequent dosing and has a greater risk of rebound anxiety and abuse potential because of its more rapid onset of action. Compared with immediate-release alprazolam, alprazolam XR has a slower absorption rate and longer steady state in the blood, but this formulation does not have lower abuse potential or greater efficacy. Although not FDA-approved for PD, diazepam and lorazepam also have proven efficacy for PD.3

Benzodiazepines should be considered contraindicated in patients with a history of substance abuse, except in select cases.4 Benzodiazepines generally should be avoided in older patients because of increased risk for falls, cognitive impairment, and motor vehicle accidents. Table 2 lists situations in which benzodiazepines may be used to treat PD.

Table 2

Clinical scenarios in which to consider using benzodiazepines

| Coadministration for 2 to 4 weeks when initiating treatment with an SSRI or venlafaxine XR to achieve more rapid relief and mitigate potential antidepressant-induced anxiety |

| For patients who wish to avoid antidepressants because of concern about sexual dysfunction |

| For patients who need chronic aspirin or an NSAID, which may increase the risk for upper gastrointestinal bleeding when taken in combination with an SSRI |

| For patients with comorbid bipolar disorder or epilepsy |

| Next-step monotherapy or augmentation in patients who respond poorly to an SSRI, venlafaxine XR, TCA, or CBT |

| CBT: cognitive-behavioral therapy; NSAID: nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug; SSRI: selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor; TCA: tricyclic antidepressant; XR: extended release |

TCAs are effective as monotherapy for PD. Most support comes from studies of imipramine or clomipramine.12 Similar to SSRIs and venlafaxine XR, use a low initial dose and gradually increase until the patient remits or side effects prevent further increases. SSRI and TCA combinations rarely are used unless the TCA is a relatively specific norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor (eg, desipramine, nortriptyline). Because TCAs are metabolized via the cytochrome P450 2D6 system and some SSRIs—particularly fluoxetine and paroxetine—strongly inhibit 2D6, combinations of TCAs with these agents may lead to dangerously high plasma TCA levels, placing patients at risk for cardiac dysrhythmias and other side effects.16

Monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs)—particularly phenelzine—are underused for PD. They have the strongest efficacy data for any class of medications outside the first- and second-line agents and have a unique mechanism of action. In patients who can comply with the dietary and medication limitations, an MAOI generally should be the next step after nonresponse to other treatments.3

Alternative treatments

For patients who do not respond to any of the treatments described above, data from uncontrolled studies support mirtazapine, levetiracetam, and the serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors duloxetine and milnacipran as monotherapy for PD.17 Pindolol—a beta blocker and 5-HT1A receptor antagonist—proved superior to placebo as an adjunctive agent to SSRIs in treatment-resistant PD in 1 of 2 trials.17 Minimal evidence supports the atypical antipsychotics risperidone and olanzapine in treatment-resistant PD, although a placebo-controlled trial of quetiapine SR coadministered with SSRIs recently was completed (NCT00619892; results pending). Atypical antipsychotics are best reserved for patients with a primary psychotic disorder or bipolar disorder who experience panic attacks.5

Panic-focused psychodynamic psychotherapy, a 12-week (approximately 24 sessions) form of psychotherapy, has demonstrated superiority vs applied relaxation therapy.18 This treatment could be considered for patients who do not respond to standard first-line treatments, but few community therapists are familiar with this method.

For many patients with PD, complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) approaches are appealing. See this article at CurrentPsychiatry.com for a Box that discusses CAM for PD.

Although no complementary and alternative medicine treatments have strong evidence of efficacy as monotherapy for panic disorder (PD), several have data that suggest benefit with little evidence of risk. These include bibliotherapy, yoga, aerobic exercise, and the dietary supplements kava and inositol.a Exercise as a treatment poses a challenge because it can induce symptoms that the patient fears, such as tachycardia and shortness of breath. In addition to any direct physiologic benefit from aerobic exercise, there is also an exposure component that can be harnessed by gradually increasing the exertion level.

Another approach undergoing extensive evaluation is Internet-provided cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT). Using guided CBT modules with or without therapist support, Internet-provided CBT provides an option for motivated patients unable to complete in-person CBT because of logistical factors.b A helpful resource that reviews Internet self-help and psychotherapy guided programs for PD and other psychiatric conditions is http://beacon.anu.edu.au.

References

a. Antonacci DJ, Davis E, Bloch RM, et al. CAM for your anxious patient: what the evidence says. Current Psychiatry. 2010;9(10):42-52.

b. Johnston L, Titov N, Andrews G, et al. A RCT of a transdiagnostic internet-delivered treatment for three anxiety disorders: examination of support roles and disorder-specific outcomes. PLoS One. 2011;6(11):e28079.

Maintenance treatment

Patients who complete a course of CBT for PD often follow up with several “booster sessions” at monthly or longer intervals that focus on relapse prevention techniques. Few controlled trials have evaluated pharmacotherapy discontinuation in PD. Most guidelines recommend continuing treatment for ≥1 year after achieving remission to minimize the risk of relapse.3 Researchers are focusing on whether medication dosage can be reduced during maintenance without loss of efficacy.

Treatment discontinuation

In the absence of urgent medical need, taper medications for PD gradually over several months. PD patients are highly sensitive to unusual physical sensations, which can occur while discontinuing antidepressants or benzodiazepines. If a benzodiazepine is used in conjunction with an antidepressant, the benzodiazepine should be discontinued first, so that the antidepressant can help ease benzodiazepine-associated discontinuation symptoms. A brief course of CBT during pharmacotherapy discontinuation may increase the likelihood of successful tapering.19

CASE CONTINUED: A successful switch

Ms. K has to discontinue sequential trials of fluoxetine, 40 mg/d, and venlafaxine XR, 225 mg/d because of side effects, and she does not reduce the frequency of her alprazolam use. She agrees to switch from alprazolam to clonazepam, 0.5 mg every morning and 1 mg at bedtime, and to start CBT. Clonazepam reduces her anxiety sufficiently so she can address her symptoms in therapy. Through CBT she becomes motivated to monitor her thoughts and treat them as guesses rather than facts, reviewing the evidence for her thoughts and generating rational responses. She participates in exposure exercises, which she practices between sessions, and grows to tolerate uncomfortable sensations until they no longer signal danger. After 12 CBT sessions, she is panic-free. Despite some trepidation, she agrees to a slow taper off clonazepam, reducing the dose by 0.25 mg every 2 weeks. She continues booster sessions with her therapist to manage any re-emerging anxiety. After an additional 12 weeks, she successfully discontinues clonazepam and remains panic-free.

Related Resources

- American Psychiatric Association. Panic disorder. http://healthyminds.org/Main-Topic/Panic-Disorder.aspx.

- Anxiety and Depression Association of America. Panic disorder & agoraphobia. http://adaa.org/understanding-anxiety/panic-disorder-agoraphobia.

- Mayo Clinic. Panic attacks and panic disorder. www.mayoclinic.com/health/panic-attacks/DS00338.

- National Health Service Self-Help Guides. www.ntw.nhs.uk/pic/selfhelp.

- National Institute of Mental Health. Panic disorder. www.nimh.nih.gov/health/topics/panic-disorder/index.shtml.

Drug Brand Names

- Alprazolam • Xanax

- Alprazolam XR • Xanax XR

- Citalopram • Celexa

- Clomipramine • Anafranil

- Clonazepam • Klonopin

- Desipramine • Norpramin

- Diazepam • Valium

- Duloxetine • Cymbalta

- Escitalopram • Lexapro

- Fluoxetine • Prozac

- Fluvoxamine • Luvox

- Imipramine • Tofranil

- Levetiracetam • Keppra

- Lorazepam • Ativan

- Milnacipran • Savella

- Mirtazapine • Remeron

- Nortriptyline • Aventyl, Pamelor

- Olanzapine • Zyprexa

- Paroxetine • Paxil

- Paroxetine CR • Paxil CR

- Phenelzine • Nardil

- Pindolol • Visken

- Quetiapine SR • Seroquel SR

- Risperidone • Risperdal

- Sertraline • Zoloft

- Venlafaxine XR • Effexor XR

Disclosures

Dr. Dunlop receives research support from Bristol-Myers Squibb, GlaxoSmithKline, and the National Institute of Mental Health. He serves as a consultant to MedAvante and Roche.

Ms. Schneider and Dr. Gerardi report no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. Roy-Byrne PP, Craske MG, Stein MB. Panic disorder. Lancet. 2006;368(9540):1023-1032.

2. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 4th ed, text rev. Washington DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2000.

3. American Psychiatric Association. Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with panic disorder. 2nd ed. Washington DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2009.

4. Dunlop BW, Davis PG. Combination treatment with benzodiazepines and SSRIs for comorbid anxiety and depression: a review. Prim Care Companion J Clin Psychiatry. 2008;10(3):222-228.

5. Rakofsky JJ, Dunlop BW. Treating nonspecific anxiety and anxiety disorders in patients with bipolar disorder: a review. J Clin Psychiatry. 2011;72(1):81-90.

6. Sareen J, Cox BJ, Afifi TO, et al. Anxiety disorders and risk for suicidal ideation and suicide attempts: a population-based longitudinal study of adults. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62(11):1249-1257.

7. Houck PR, Spiegel DA, Shear MK, et al. Reliability of the self-report version of the panic disorder severity scale. Depress Anxiety. 2002;15(4):183-185.

8. Ninan PT, Dunlop BW. Neurobiology and etiology of panic disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 2005;66(suppl 4):3-7.

9. Furukawa TA, Watanabe N, Churchill R. Psychotherapy plus antidepressant for panic disorder with or without agoraphobia: systematic review. Br J Psychiatry. 2006;188:305-312.

10. Barlow DH, Gorman JM, Shear MK, et al. Cognitive-behavioral therapy, imipramine, or their combination for panic disorder: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2000;283(19):2529-2536.

11. van Apeldoorn FJ, Timmerman ME, Mersch PP, et al. A randomized trial of cognitive-behavioral therapy or selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor or both combined for panic disorder with or without agoraphobia: treatment results through 1-year follow-up. J Clin Psychiatry. 2010;71(5):574-586.

12. Bakker A, van Balkom AJ, Spinhoven P. SSRIs vs. TCAs in the treatment of panic disorder: a meta-analysis. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2002;106(3):163-167.

13. Bandelow B, Behnke K, Lenoir S, et al. Sertraline versus paroxetine in the treatment of panic disorder: an acute, double-blind noninferiority comparison. J Clin Psychiatry. 2004;65(3):405-413.

14. Nardi AE, Freire RC, Mochcovitch MD, et al. A randomized, naturalistic, parallel-group study for the long-term treatment of panic disorder with clonazepam or paroxetine. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2012;32(1):120-126.

15. Goddard AW, Brouette T, Almai A, et al. Early coadministration of clonazepam with sertraline for panic disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2001;58(7):681-686.

16. Preskorn SH, Shah R, Neff M, et al. The potential for clinically significant drug-drug interactions involving the CYP 2D6 system: effects with fluoxetine and paroxetine versus sertraline. J Psychiatr Pract. 2007;13(1):5-12.

17. Perna G, Guerriero G, Caldirola D. Emerging drugs for panic disorder. Expert Opin Emerg Drugs. 2011;16(4):631-645.

18. Milrod B, Leon AC, Busch F, et al. A randomized controlled clinical trial of psychoanalytic psychotherapy for panic disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2007;164(2):265-272.

19. Otto MW, Pollack MH, Sachs GS, et al. Discontinuation of benzodiazepine treatment: efficacy of cognitive-behavioral therapy for patients with panic disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 1993;150(10):1485-1490.

1. Roy-Byrne PP, Craske MG, Stein MB. Panic disorder. Lancet. 2006;368(9540):1023-1032.

2. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 4th ed, text rev. Washington DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2000.

3. American Psychiatric Association. Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with panic disorder. 2nd ed. Washington DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2009.

4. Dunlop BW, Davis PG. Combination treatment with benzodiazepines and SSRIs for comorbid anxiety and depression: a review. Prim Care Companion J Clin Psychiatry. 2008;10(3):222-228.

5. Rakofsky JJ, Dunlop BW. Treating nonspecific anxiety and anxiety disorders in patients with bipolar disorder: a review. J Clin Psychiatry. 2011;72(1):81-90.

6. Sareen J, Cox BJ, Afifi TO, et al. Anxiety disorders and risk for suicidal ideation and suicide attempts: a population-based longitudinal study of adults. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62(11):1249-1257.

7. Houck PR, Spiegel DA, Shear MK, et al. Reliability of the self-report version of the panic disorder severity scale. Depress Anxiety. 2002;15(4):183-185.