User login

Sim and Learn: Simulation and its Value in Neurology Education

Sim and Learn: Simulation and its Value in Neurology Education

Clinical simulation is a technique, not a technology, used to replace or amplify real experiences with guided experiences that evoke or replicate substantial aspects of the real world in a fully interactive fashion.1 Simulation is widely used in medical education and spans a spectrum of sophistication, from simple reproduction of isolated body parts to high-fidelity human patient simulators that replicate whole body appearance and variable physiological parameters.2,3

Simulation-based medical education can be a valuable tool for safe health care delivery.4Simulation-based education is typically provided via 5 modalities: mannequins, computer-based mannequins, standardized patients, computer-based simulators, and software-based simulations. Simulation technology increases procedural skill by allowing for deliberate practice in a safe environment.5 Mastery learning is a stringent form of competency-based education that requires trainees to acquire clinical skill measured against a fixed achievement standard.6 In mastery learning, educational practice time varies but results are uniform. This approach improves patient outcomes and is more effective than clinical training alone.7-9

Advanced simulation models are helpful tools for neurologic education and training, especially for emergency department encounters.10 In recent years, advanced simulation models have been applied in various fields of medicine, especially emergency medicine and anesthesia.11-14

Acute neurology

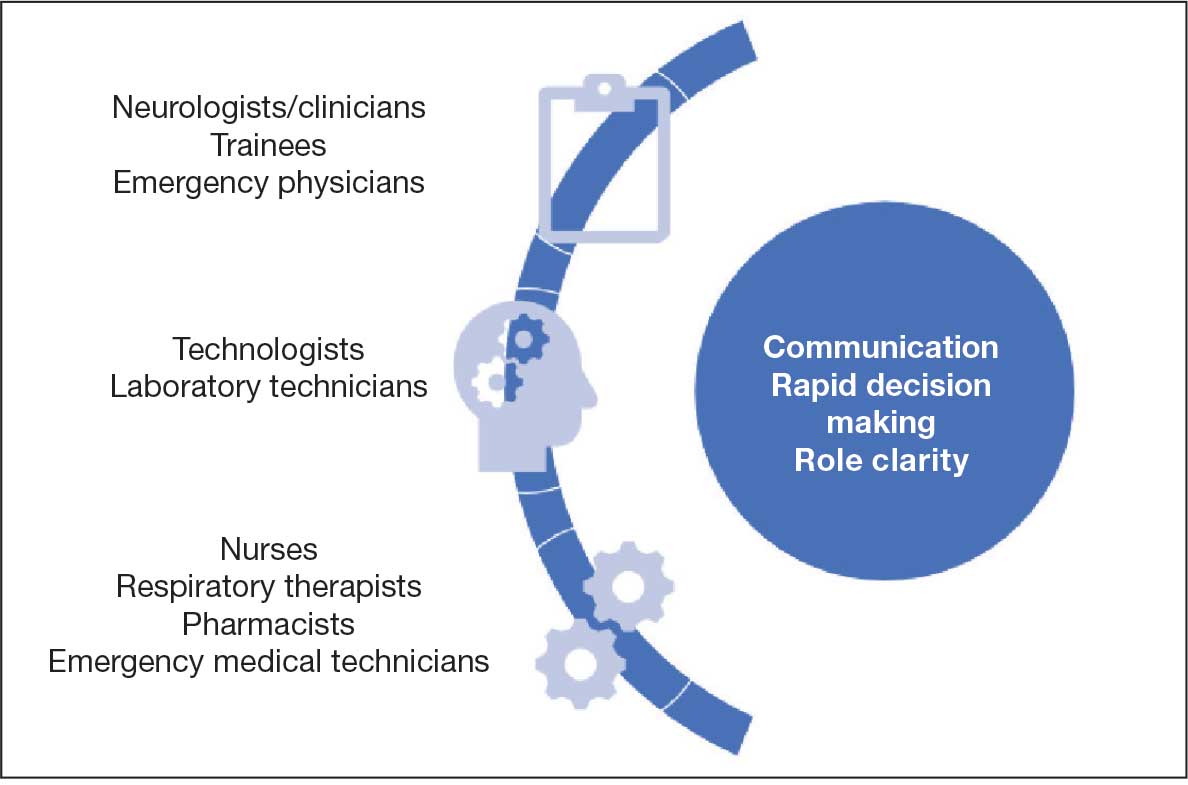

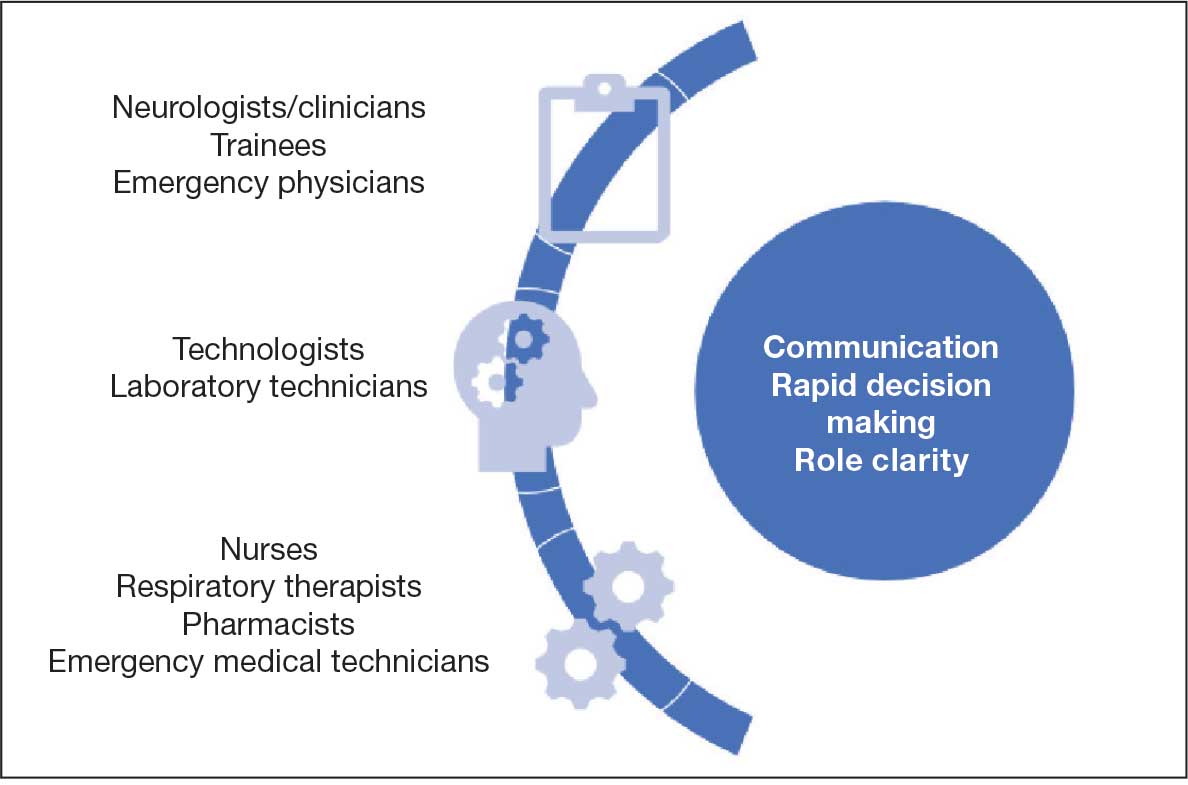

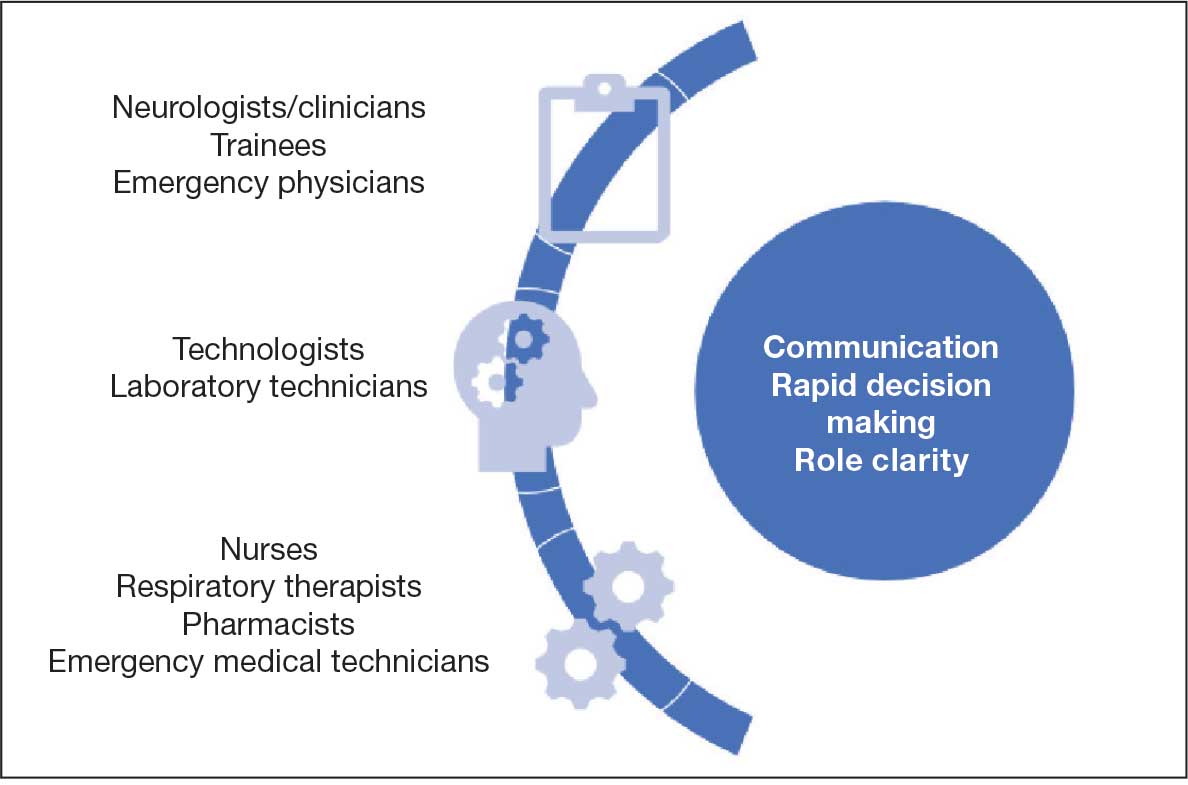

In acute neurologic conditions (eg, stroke, intracerebral hemorrhage, status epilepticus, and neuromuscular respiratory failure) clinical outcomes are highly time dependent; consequently, a reduction in treatment delays can improve patient care. The application of simulation methodology allows trainees to address acute and potentially life-threatening emergencies in a safe, controlled, and reproducible environment. In addition to improving trainees’ knowledge base, simulation also helps to enhance team skills, communication, multidisciplinary collaboration, and leadership. Research has shown that deliberate practice leads to a decrease in clinical errors and improved procedural performance in the operating room.8,15 These results can be extrapolated to acute neurology settings to improve adherence to set protocols, thus streamlining management in acute settings.

Scenarios can be built to teach skills such as eliciting an appropriate history, establishing inclusion or exclusion criteria for the use of certain medications, evaluating neuroimaging and laboratory studies (while avoiding related common pitfalls), and managing treatment complications. Simulation also provides an opportunity for interprofessional education by training nurses and collaborative staff. It can be used to enhance nontechnical skills (eg, communication, situation awareness, decision making, and leadership) that further contribute to patient safety.

Simulation can be performed with the help of mannequins such as the SimMan 3G(Laerdal), which can display neurologic symptoms and physiological findings, or live actors who portray a patient by mimicking focal neurologic deficits.16,17 A briefing familiarizes the trainees with the equipment and explains the simulation process. The documentation and equipment are the same as that which is used in emergency departments or intensive care units.

Once the simulation is completed, a trainee’s performance is checked against a critical action checklist before a debriefing process during which the scenario is reviewed and learning goals are assessed. Immediate feedback is given to trainees to identify weaknesses and the simulation is repeated if multiple critical action items are missed. (Figure).17

RESIDENCY TRAINING

Simulation training in stroke is mandatory in some residency programs for neurology postgraduate year (PGY) 2 residents.18 These simulations are a part of a boot camp for incoming neurology residents after completing an internal medicine internship. The simulation program is not standardized across various training programs. The European Stroke Organization Simulation Committee has published an opinion paper with a consensus of experts about the implementation of simulation techniques in the stroke field.19,20 Residents participating in these mandatory programs are required to complete certification in the National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale (NIHSS) and the modified Rankin Scale, including a pretest that assesses their knowledge of acute stroke protocols prior to live simulation.17 A stepwise algorithm that incorporates faculty specialized in the field is used to evaluate and debrief the simulation.

Stroke vignettes are typically selected by the vascular neurology attending physician to cover thrombolytic therapy (indications and contraindications), mechanical thrombectomy, early arterial blood pressure management, anticoagulant reversal protocols, and management of thrombolytic complications (eg, neurologic worsening). Nursing staff is educated on the acute stroke protocol. Computed tomography (CT) and CT angiography scans are retrieved from teaching files. These are provided as live responses along with pertinent laboratory work, vital signs, and electrocardiogram tracings. Trainee performance is based on adherence to a critical action checklist, which includes (but is not limited to) identification of relative and absolute contraindications of thrombolytic treatments, estimation of NIHSS within 5 minutes of arrival, and consideration of candidacy for endovascular intervention.17

EVIDENCE FOR SIMULATION TRAINING

Simulations for acute ischemic stroke also improve cohesive teamwork to improve the door-to-needle and door-to-puncture time. A retrospective analysis involving first-year neurology residents at a comprehensive stroke center that compared patient cohort data before and after implementation of simulation training found that there was an improvement in door-to-needle time after implementation of stroke simulation training program by nearly 10 minutes.17 This was likely due to improvement in the comfort of the flow of management across multidisciplinary teams.

Discussing goals of care, communicating poor prognosis or complex decisions with distraught family members or patients requires practice. Simulation programs with video playback help focus on trainee’s body language, avoiding medical jargon and handling ethical dilemmas while adjusting the communication style to the patient’s personality.20 Enhanced communication skills improve patient satisfaction, trust, and adherence to treatments, all of which lead to better outcomes.21

Simulation has been effectively used as a training tool for recognizing and managing acute neuromuscular respiratory failure. These scenarios emphasize the importance of obtaining a focused clinical history, performing key neurological assessments (such as neck flexion strength and breath counting), evaluating pulmonary function tests, and identifying when to initiate ventilatory support.22 In a study designed as a simulation-based learning curriculum for status epilepticus, there was an improvement in the performance of PGY-2 residents after completing the curriculum from a median of 44.2% at pretest to 94.2% at posttest.23 In this curriculum, an emphasis was placed on the following: recognizing the delay in identification and treatment of status epilepticus; evaluating contraindications of certain antiseizure medication (ASM) based on history or laboratory work; giving first-line ASM within 5 minutes of seizure onset; airway and blood pressure assessment; suctioning the patient; use of second-line ASMs after first-line has failed; ordering a head CT and re-evaluating the case with postload ASM level; ordering a stat electroencephalography (EEG); and communicating the decision regarding patient disposition/level of care.24

There is a growing need for well designed simulation education programs targeted at the management of disorders requiring acute neurologic care, including not only stroke and status epilepticus, but also traumatic brain injury, subarachnoid hemorrhage, neuromuscular respiratory failure, flare of multiple sclerosis, acutely elevated intracranial pressure, malignant cerebral infarction, deterioration of Parkinson disease, and brain death evaluation with family counseling.25 This novel approach to teaching provides an opportunity to learn in addition to remediation with repetition of scenario and might be used for maintenance of recertification programs.

PROCEDURAL SKILLs

Perhaps one of the most studied uses for simulation in neurology is in procedural skills. This extends beyond neurology trainees and can include pulmonary critical care fellows, pediatric residents, and internal medicine residents receiving training in neurology-based procedures such as lumbar punctures (LPs). Other examples of neurology procedures and protocols in which simulation has been studied include fundoscopy, brain death evaluation, EEG interpretation in context of status epilepticus, and simulated stroke code responses. Additional procedures that lack research but may benefit from simulation-based training include the use of Doppler ultrasound and botulinum toxin injections practiced on mannequins.

Proficiency in LP procedural skills has been extensively studied by multiple institutions, with trainee levels ranging from medical students to fellows. One study in France enrolled 115 medical students without prior LP experience and randomized them to either a simulation or a control group.26 Those in the simulation group received instruction using a mannequin, and those in the control group received clinical training through hospital rotations. Both groups received an email containing literature-based information on the procedure as well as a self-assessment questionnaire before participating in either educational program.

The study showed that those students who received simulation training had a success rate of 67% on their first LP on a live patient compared with a success rate of 14% in those with traditional training. Students receiving simulation training required less assistance during the procedure from a supervisor and had higher satisfaction rates and confidence in their procedural skills.26

Another study of 128 medical students at the University of Pittsburgh found that a hybrid LP simulation significantly improved students’ confidence and perceived skill in performing LPs, obtaining informed consent, and electronic order entry. For example, confidence with LP increased from 5.95% presimulation to 90% postsimulation, with 58.24% of students reporting an improvement from minimal or no confidence to average or better (P < .001). Similarly, the proportion of students who felt able to perform LP with minimal or no assistance rose from 0% to 38.57% (P < .001). Confidence and perceived skill in obtaining informed consent and electronic order entry also saw significant gains. Although real-world skill assessments were limited by low survey response rates, preceptor evaluations and follow-up surveys suggested that students who participated in the simulation were more likely to perform these tasks independently or with minimal supervision during clinical rotations.27

Research on simulation training involving nonneurology residents is also encouraging. One study compared the LP skills of traditionally trained neurology residents (PGY-2 to PGY-4) to internal medicine residents (PGY-1) who underwent simulation on a mannequin.28 The internal medicine residents first underwent a pretest on LP performance, watched an educational video, underwent an LP demonstration, and practiced on a mannequin with feedback. The neurology residents completed the checklist-style pretest and performed an LP on a mannequin. Internal medicine residents were found to increase their pretest scores from a mean of 46.3% to 95.7% following training, whereas neurology residents scored a mean of 65.4%. More than half of neurology residents were unable to identify the correct anatomic location or standard cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) tests to be ordered on a routine LP.28

A pediatric resident study in Canada found that following simulation-based training, LP procedural skill improved in 15 of 16 residents tested, and PGY-1 residents showed a reduction in anxiety related to performing the procedure.29

Virtual Reality

An additional tool for simulation is the use of virtual reality (VR) in combination with mannequins. A French study used videos of LPs on actual patients, from equipment set up to final CSF collection and termination of the procedure.30 These videos included a 360-degree view of the procedure. The short video was administered through a VR device (the Oculus Go headset by Microsoft) or by a YouTube video (if VR was not desired).

Participants in the study watched the video then performed an LP on a mannequin. Those who used the VR option had minimal adverse effects (eg, low rates of cybersickness, blurred vision, nausea) and high satisfaction regarding their training environment.30Another VR-based program is the vascular intervention system trainer, which allows clinicians to use endovascular devices and simulate procedures such as thrombectomies. VR simulation is used for trainees and to retrain experienced physicians in performance of high-risk procedures.31

Fundoscopic and Ultrasound Simulations

The AR403 eye stimulator device for fundoscopic examinations is a mannequin-based simulation.32 In a single-center, prospective, single-blind study of neurology and pediatric neurology residents, trainees were split into control and intervention groups, with the intervention group receiving simulator training. Both groups received video lectures on fundoscopy techniques. Pre- and postintervention measurements included knowledge, skill, and total scores on the skills assessment. Of the 48 trainees who participated, the intervention group demonstrated significantly higher increases in skills (P = .01) and total (P = .02) scores, although knowledge scores did not improve. The intervention group also reported higher comfort levels, higher confidence, and higher success rates.

Areas that would benefit from simulation training and development include ultrasound training, such as transcranial Doppler evaluation. In a national survey of residents in anesthesia and critical care, trainees reported that simulation was not frequently used in ultrasound training and that bedside teaching was more common. Interestingly, there was a discrepancy between the opinions of residents and program directors. The program directors felt simulation was in fact used (18.2% of program directors reported this vs 5.3% of trainees).33

A new program, the NewroSim (Gaumard), is a computer-based model of cerebral perfusion that may be a useful tool in this setting. It can simulate blood flow velocities, including pathologic ones, both with a mannequin or without.34

Another potential area for development is the use of mannequins to teach botulinum toxin injections for migraine, dystonia and spasticity in a training environment This is typically led by pharmaceutical representatives who are not necessarily clinicians. Residents and fellows may benefit instead from clinician-led education during their training programs.

Simulation in Patient Communication

Simulation provides a realistic environment for teaching rapid decision-making, leadership, and appropriate management of acutely ill neurologic patients; this includes the communication skills needed in response to neurologic injury.35 Simulation can be particularly useful in situations involving brain death determination, where the communication techniques differ significantly from those used in shared decision-making. Simulation provides a low-stakes setting for clinicians to practice the process of brain death determination and communication, leading to improved confidence and knowledge.36

In the context of acute neurologic emergencies, simulation exercises have been used to investigate the consistency of prognostication across a spectrum of neurology physicians. These exercises revealed that acute neuroprognostication is highly variable and often inaccurate among neurology clinicians, suggesting a potential area for improvement through further simulation training.37

FUTURE DIRECTIONS

Simulation education in neurology can be directed towards learners at all levels, including medical students, residents, fellows, nurses, and medical technologists. In addition, simulation has great value to different disciplines, including emergency medicine, intensive care, and psychiatry. In our view simulation is not being used to full potential in neurology.

Simulation can be used to expose clinicians to rare pathology, play an integral role in competency-based evaluations, and serve as the foundation for simulation-based neurology curriculums, teleneurology simulation training programs, and team training for neurologic emergencies.38Another under-recognized aspect of neurology education is teaching interpersonal communication and professionalism. A survey conducted at a neurology department (20 residents and 73 faculty respondents) asked about residents’ comfort level in performing a number of interpersonal communication and professionalism tasks.38 While none of the residents said they were “very uncomfortable” with these tasks, only 1 resident reported being “very comfortable.” In addition, fewer than 50% noted that they had been directly observed by a faculty member while performing these tasks. The results prompted the facility to develop a simulation curriculum that including observation and feedback from 8 objective structured clinical examinations at a simulation center. A standardized professional simulated the role of a patient, caregiver, medical student, or a faculty member. Residents indicated in postsimulation surveys that it was very useful, and a majority voted for the activity to be repeated for future classes.38

Simulation models may also provide a more objective method to evaluate neurology residents. Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education has provided Milestones that are used for assessment of neurology residents. Most of the programs rely on end-of-rotation faculty evaluations. These are subjective evaluations, rely on chance evaluations and may not reflect the exact caliber of a trainee in different clinical situations. Simulation models can serve as alternatives to provide an objective and accurate assessment of resident’s competency in different neurologic scenarios.

In a study of PGY-4 neurology residents from 3 tertiary care academic medical centers were evaluated using simulation-based assessment. Their skills in identifying and managing status epilepticus were assessed via a simulation-based model and compared with clinical experience. No graduating neurology residents were able to meet or exceed the minimum passing score during the testing. It was suggested that end-of-rotation evaluations are inadequate for assigning level of Milestones.24 To move forward with use of simulation-based assessments, these models need to be trialed more extensively and validated.

Morris et al developed simulations for assessment in neurocritical care.39 Ten evaluative simulation cases were developed. Researchers reported on 64 trainee participants in 274 evaluative simulation scenarios. The participants were very satisfied with the cases, found them to be very realistic and appropriately difficult. Interrater reliability was acceptable for both checklist action items and global rating scales. The researchers concluded that they were able to demonstrate validity evidence via the 10 simulation cases for assessment in neurologic emergencies.39 It is the authors’ belief that the future of residents’ competency assessment should include more widespread use of similar simulation models.

Finally, VR and augmented reality (AR) have shown promise in various fields, including neurology. In neurology, these technologies are being explored for applications in rehabilitation, therapy, and medical training. Ongoing research aims to leverage these technologies for improved patient outcomes and medical education. Virtual simulations can recreate neurologic scenarios, allowing learners to interact with 3-dimensional (3D) models of the brain or experience virtual patient cases. AR can enhance traditional learning materials by overlaying digital information onto real-world objects, aiding in the understanding of complex neuroanatomy and medical concepts. These technologies contribute to more engaging and effective neurology education.39In a study of 84 graduate medical students divided into 3 groups, the first group attended a traditional lecture on neuroanatomy, the second group was shown VR-based 3D images, and the third group had a VR-based, interactive and stereoscopic session.40 Groups 2 and 3 showed the highest mean scores in evaluations and differed significantly from Group 1 (P < .05). Groups 2 and 3 did not differ significantly from each other. The researchers concluded that VR-based resources for teaching neuroanatomy fostered significantly higher learning when compared to the traditional methods.40

- Corvetto M, Bravo MP, Montaña R, et al. Simulación en educación médica: una sinopsis. Rev Med Chil. 2013;141:70-79. doi:10.4067/S0034-98872013000100010

- Lane JL, Slavin S, Ziv A. Simulation in medical education: a review. Simul Gaming. 2001;32:297-314. doi:10.1177/104687810103200302

- Bradley P. The history of simulation in medical education and possible future directions. Med Educ. 2006;40:254-262. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2929.2006.02394.x

- Jones F, Passos-Neto C, Melro Braghiroli O. Simulation in medical education: brief history and methodology. Princ Pract Clin Res J. 2015;1:46-54. doi:10.21801/ppcrj.2015.12.8

- Issenberg SB. Simulation technology for health care professional skills training and assessment. JAMA. 1999;28:861-866. doi:10.1001/jama.282.9.861

- McGaghie WC, Miller GE, Sajid AW, et al. Competency-based curriculum development on medical education: an introduction. Public Health Pap. 1978;68:11-91.

- Barsuk JH, Cohen ER, Feinglass J, et al. Use of simulation-based education to reduce catheter-related bloodstream infections. Arch Intern Med. 2009;169:1420-1423. doi:10.1001/archinternmed.2009.215

- Wayne DB, Didwania A, Feinglass J, et al. Simulation-based education improves quality of care during cardiac arrest team responses at an academic teaching hospital: a case-control study. Chest. 2008;133:56-61. doi:10.1378/chest.07-0131

- McGaghie WC, Issenberg SB, Cohen ER, et al. Does simulation-based medical education with deliberate practice yield better results than traditional clinical education? A meta-analytic comparative review of the evidence. Acad Med. 2011;86:706-711. doi:10.1097/ACM.0b013e318217e119

- Micieli G, Cavallini A, Santalucia P, et al. Simulation in neurology. Neurol Sci. 2015;36:1967-1971. doi:10.1007/s10072-015-2228-8

- Bond WF, Lammers RL, Spillane LL, et al. The use of simulation in emergency medicine: a research agenda. Acad Emerg Med. 2007;14:353-363. doi:10.1197/j.aem.2006.11.02112.

- McLaughlin SA, Doezema D, Sklar DP. Human simulation in emergency medicine training: a model curriculum. Acad Emerg Med. 2002;9:1310-1318. doi:10.1111/j.1553-2712.2002.tb01593.x

- Howard SK, Gaba DM, Fish KJ, et al. Anesthesia crisis resource management training: teaching anesthesiologists to handle critical incidents. Aviat Space Environ Med. 1992;63:763-770.

- Gaba DM. Anaesthesiology as a model for patient safety in health care. BMJ. 2000;320:785-788. doi:10.1136/bmj.320.7237.785

- Sedlack RE, Kolars JC. Computer simulator training enhances the competency of gastroenterology fellows at colonoscopy: results of a pilot study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2004;99:33-37. doi:10.1111/j.1572-0241.2004.04007.x

- Tchopev ZN, Nelson AE, Hunninghake JC, et al. Curriculum innovations: high-fidelity simulation of acute neurology enhances rising resident confidence: results from a multicohort study. Neurol Educ. 2022;1:e200022. doi:10.1212/ne9.0000000000200022

- Mehta T, Strauss S, Beland D, et al. Stroke simulation improves acute stroke management: a systems-based practice experience. J Grad Med Educ. 2018;10:57-62. doi:10.4300/JGME-D-17-00167.1

- Pergakis MB, Chang WTW, Tabatabai A, et al. Simulation-based assessment of graduate neurology trainees’ performance managing acute ischemic stroke. Neurology. 2021;97:e2414-e2422. doi:10.1212/WNL.0000000000012972

- Casolla B. Simulation for neurology training: acute setting and beyond. Rev Neurol (Paris). 2021;177:1207-1213. doi:10.1016/j.neurol.2021.03.008

- Casolla B, de Leciñana MA, Neves R, et al. Simulation training programs for acute stroke care: Objectives and standards of methodology. Eur Stroke J. 2020;5:328-335. doi:10.1177/2396987320971105

- Zolnierek KB, Dimatteo MR. Physician communication and patient adherence to treatment: a meta-analysis. Med Care. 2009;47:826-834.doi:10.1097/MLR.0b013e31819a5acc

- Patel RA, Mohl L, Paetow G, Maiser S. Acute neuromuscular respiratory weakness due to acute inflammatory demyelinating polyneuropathy (AIDP): a simulation scenario for neurology providers. MedEdPORTAL. 2019;15:10811. doi:10.15766/mep_2374-8265.10811

- Mikhaeil-Demo Y, Barsuk JH, Culler GW, et al. Use of a simulation-based mastery learning curriculum for neurology residents to improve the identification and management of status epilepticus. Epilepsy Behav. 2020;111:107247. doi:10.1016/j.yebeh.2020.107247

- Mikhaeil-Demo Y, Holmboe E, Gerard EE, et al. Simulation-based assessments and graduating neurology residents’ milestones: status epilepticus milestones. J Grad Med Educ. 2021;13:223-230. doi:10.4300/JGME-D-20-00832.1

- Hocker S, Wijdicks EFM, Feske SK, et al. Use of simulation in acute neurology training: point and counterpoint. Ann Neurol. 2015;78:337-342. doi:10.1002/ana.24473

- Gaubert S, Blet A, Dib F, et al. Positive effects of lumbar puncture simulation training for medical students in clinical practice. BMC Med Educ. 2021;21:1-6. doi:10.1186/S12909-020-02452-327.

- Yanta C, Knepper L, Van Deusen R, et al. The use of hybrid lumbar puncture simulation to teach entrustable professional activities during a medical student neurology clerkship. MedEdPublish (2016). 2021;9:266. doi:10.15694/mep.2020.000266.2

- Barsuk JH, Cohen ER, Caprio T, et al. Simulation-based education with mastery learning improves residents’ lumbar puncture skills. Neurology. 2012;79:132-137. doi:10.1212/WNL.0B013E31825DD39D

- McMillan HJ, Writer H, Moreau KA, et al. Lumbar puncture simulation in pediatric residency training: improving procedural competence and decreasing anxiety. BMC Med Educ. 2016;16:198. doi:10.1186/S12909-016-0722-1

- Vrillon A, Gonzales-Marabal L, Ceccaldi PF, et al. Using virtual reality in lumbar puncture training improves students learning experience. BMC Med Educ. 2022;22:244. doi:10.1186/S12909-022-03317-7

- Liebig T, Holtmannspötter M, Crossley R, et al. Metric-based virtual reality simulation: a paradigm shift in training for mechanical thrombectomy in acute stroke. Stroke. 2018;49:e239-e242.doi:10.1161/STROKEAHA.118.021089

- Gupta DK, Khandker N, Stacy K, et al. Utility of combining a simulation-based method with a lecture-based method for fundoscopy training in neurology residency. JAMA Neurol. 2017;74:1223-1227. doi:10.1001/JAMANEUROL.2017.2073

- Mongodi S, Bonomi F, Vaschetto R, et al. Point-of-care ultrasound training for residents in anaesthesia and critical care: results of a national survey comparing residents and training program directors’ perspectives. BMC Med Educ. 2022;22:647. doi:10.1186/S12909-022-03708-W

- Morris NA, Czeisler BM, Sarwal A. Simulation in neurocritical care: past, present, and future. Neurocrit Care. 2019;30:522-533. doi:10.1007/S12028-018-0629-2

- Wijdicks EFM, Hocker SE. A future for simulation in acute neurology. Semin Neurol. 2018;38:465-470. doi:10.1055/s-0038-1666986

- Kramer NM, O’Mahony S, Deamant C. Brain death determination and communication: an innovative approach using simulation and standardized patients. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2022;63:e765-e772. doi:10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2022.01.020

- Sloane KL, Miller JJ, Piquet A, et al. Prognostication in acute neurological emergencies. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2022;31:106277. doi:10.1016/J.JSTROKECEREBROVASDIS.2021.106277

- Kurzweil AM, Lewis A, Pleninger P, et al. Education research: teaching and assessing communication and professionalism in neurology residency with simulation. Neurology. 2020;94:229-232. doi:10.1212/WNL.0000000000008895

- Morris NA, Chang WT, Tabatabai A, et al. Development of neurological emergency simulations for assessment: content evidence and response process. Neurocrit Care. 2021;35:389-396. doi:10.1007/S12028-020-01176-Y

- De Faria JWV, Teixeira MJ, De Moura Sousa Júnior L, et al. Virtual and stereoscopic anatomy: when virtual reality meets medical education. J Neurosurg. 2016;125:1105-1111. doi:10.3171/2015.8.JNS141563

Clinical simulation is a technique, not a technology, used to replace or amplify real experiences with guided experiences that evoke or replicate substantial aspects of the real world in a fully interactive fashion.1 Simulation is widely used in medical education and spans a spectrum of sophistication, from simple reproduction of isolated body parts to high-fidelity human patient simulators that replicate whole body appearance and variable physiological parameters.2,3

Simulation-based medical education can be a valuable tool for safe health care delivery.4Simulation-based education is typically provided via 5 modalities: mannequins, computer-based mannequins, standardized patients, computer-based simulators, and software-based simulations. Simulation technology increases procedural skill by allowing for deliberate practice in a safe environment.5 Mastery learning is a stringent form of competency-based education that requires trainees to acquire clinical skill measured against a fixed achievement standard.6 In mastery learning, educational practice time varies but results are uniform. This approach improves patient outcomes and is more effective than clinical training alone.7-9

Advanced simulation models are helpful tools for neurologic education and training, especially for emergency department encounters.10 In recent years, advanced simulation models have been applied in various fields of medicine, especially emergency medicine and anesthesia.11-14

Acute neurology

In acute neurologic conditions (eg, stroke, intracerebral hemorrhage, status epilepticus, and neuromuscular respiratory failure) clinical outcomes are highly time dependent; consequently, a reduction in treatment delays can improve patient care. The application of simulation methodology allows trainees to address acute and potentially life-threatening emergencies in a safe, controlled, and reproducible environment. In addition to improving trainees’ knowledge base, simulation also helps to enhance team skills, communication, multidisciplinary collaboration, and leadership. Research has shown that deliberate practice leads to a decrease in clinical errors and improved procedural performance in the operating room.8,15 These results can be extrapolated to acute neurology settings to improve adherence to set protocols, thus streamlining management in acute settings.

Scenarios can be built to teach skills such as eliciting an appropriate history, establishing inclusion or exclusion criteria for the use of certain medications, evaluating neuroimaging and laboratory studies (while avoiding related common pitfalls), and managing treatment complications. Simulation also provides an opportunity for interprofessional education by training nurses and collaborative staff. It can be used to enhance nontechnical skills (eg, communication, situation awareness, decision making, and leadership) that further contribute to patient safety.

Simulation can be performed with the help of mannequins such as the SimMan 3G(Laerdal), which can display neurologic symptoms and physiological findings, or live actors who portray a patient by mimicking focal neurologic deficits.16,17 A briefing familiarizes the trainees with the equipment and explains the simulation process. The documentation and equipment are the same as that which is used in emergency departments or intensive care units.

Once the simulation is completed, a trainee’s performance is checked against a critical action checklist before a debriefing process during which the scenario is reviewed and learning goals are assessed. Immediate feedback is given to trainees to identify weaknesses and the simulation is repeated if multiple critical action items are missed. (Figure).17

RESIDENCY TRAINING

Simulation training in stroke is mandatory in some residency programs for neurology postgraduate year (PGY) 2 residents.18 These simulations are a part of a boot camp for incoming neurology residents after completing an internal medicine internship. The simulation program is not standardized across various training programs. The European Stroke Organization Simulation Committee has published an opinion paper with a consensus of experts about the implementation of simulation techniques in the stroke field.19,20 Residents participating in these mandatory programs are required to complete certification in the National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale (NIHSS) and the modified Rankin Scale, including a pretest that assesses their knowledge of acute stroke protocols prior to live simulation.17 A stepwise algorithm that incorporates faculty specialized in the field is used to evaluate and debrief the simulation.

Stroke vignettes are typically selected by the vascular neurology attending physician to cover thrombolytic therapy (indications and contraindications), mechanical thrombectomy, early arterial blood pressure management, anticoagulant reversal protocols, and management of thrombolytic complications (eg, neurologic worsening). Nursing staff is educated on the acute stroke protocol. Computed tomography (CT) and CT angiography scans are retrieved from teaching files. These are provided as live responses along with pertinent laboratory work, vital signs, and electrocardiogram tracings. Trainee performance is based on adherence to a critical action checklist, which includes (but is not limited to) identification of relative and absolute contraindications of thrombolytic treatments, estimation of NIHSS within 5 minutes of arrival, and consideration of candidacy for endovascular intervention.17

EVIDENCE FOR SIMULATION TRAINING

Simulations for acute ischemic stroke also improve cohesive teamwork to improve the door-to-needle and door-to-puncture time. A retrospective analysis involving first-year neurology residents at a comprehensive stroke center that compared patient cohort data before and after implementation of simulation training found that there was an improvement in door-to-needle time after implementation of stroke simulation training program by nearly 10 minutes.17 This was likely due to improvement in the comfort of the flow of management across multidisciplinary teams.

Discussing goals of care, communicating poor prognosis or complex decisions with distraught family members or patients requires practice. Simulation programs with video playback help focus on trainee’s body language, avoiding medical jargon and handling ethical dilemmas while adjusting the communication style to the patient’s personality.20 Enhanced communication skills improve patient satisfaction, trust, and adherence to treatments, all of which lead to better outcomes.21

Simulation has been effectively used as a training tool for recognizing and managing acute neuromuscular respiratory failure. These scenarios emphasize the importance of obtaining a focused clinical history, performing key neurological assessments (such as neck flexion strength and breath counting), evaluating pulmonary function tests, and identifying when to initiate ventilatory support.22 In a study designed as a simulation-based learning curriculum for status epilepticus, there was an improvement in the performance of PGY-2 residents after completing the curriculum from a median of 44.2% at pretest to 94.2% at posttest.23 In this curriculum, an emphasis was placed on the following: recognizing the delay in identification and treatment of status epilepticus; evaluating contraindications of certain antiseizure medication (ASM) based on history or laboratory work; giving first-line ASM within 5 minutes of seizure onset; airway and blood pressure assessment; suctioning the patient; use of second-line ASMs after first-line has failed; ordering a head CT and re-evaluating the case with postload ASM level; ordering a stat electroencephalography (EEG); and communicating the decision regarding patient disposition/level of care.24

There is a growing need for well designed simulation education programs targeted at the management of disorders requiring acute neurologic care, including not only stroke and status epilepticus, but also traumatic brain injury, subarachnoid hemorrhage, neuromuscular respiratory failure, flare of multiple sclerosis, acutely elevated intracranial pressure, malignant cerebral infarction, deterioration of Parkinson disease, and brain death evaluation with family counseling.25 This novel approach to teaching provides an opportunity to learn in addition to remediation with repetition of scenario and might be used for maintenance of recertification programs.

PROCEDURAL SKILLs

Perhaps one of the most studied uses for simulation in neurology is in procedural skills. This extends beyond neurology trainees and can include pulmonary critical care fellows, pediatric residents, and internal medicine residents receiving training in neurology-based procedures such as lumbar punctures (LPs). Other examples of neurology procedures and protocols in which simulation has been studied include fundoscopy, brain death evaluation, EEG interpretation in context of status epilepticus, and simulated stroke code responses. Additional procedures that lack research but may benefit from simulation-based training include the use of Doppler ultrasound and botulinum toxin injections practiced on mannequins.

Proficiency in LP procedural skills has been extensively studied by multiple institutions, with trainee levels ranging from medical students to fellows. One study in France enrolled 115 medical students without prior LP experience and randomized them to either a simulation or a control group.26 Those in the simulation group received instruction using a mannequin, and those in the control group received clinical training through hospital rotations. Both groups received an email containing literature-based information on the procedure as well as a self-assessment questionnaire before participating in either educational program.

The study showed that those students who received simulation training had a success rate of 67% on their first LP on a live patient compared with a success rate of 14% in those with traditional training. Students receiving simulation training required less assistance during the procedure from a supervisor and had higher satisfaction rates and confidence in their procedural skills.26

Another study of 128 medical students at the University of Pittsburgh found that a hybrid LP simulation significantly improved students’ confidence and perceived skill in performing LPs, obtaining informed consent, and electronic order entry. For example, confidence with LP increased from 5.95% presimulation to 90% postsimulation, with 58.24% of students reporting an improvement from minimal or no confidence to average or better (P < .001). Similarly, the proportion of students who felt able to perform LP with minimal or no assistance rose from 0% to 38.57% (P < .001). Confidence and perceived skill in obtaining informed consent and electronic order entry also saw significant gains. Although real-world skill assessments were limited by low survey response rates, preceptor evaluations and follow-up surveys suggested that students who participated in the simulation were more likely to perform these tasks independently or with minimal supervision during clinical rotations.27

Research on simulation training involving nonneurology residents is also encouraging. One study compared the LP skills of traditionally trained neurology residents (PGY-2 to PGY-4) to internal medicine residents (PGY-1) who underwent simulation on a mannequin.28 The internal medicine residents first underwent a pretest on LP performance, watched an educational video, underwent an LP demonstration, and practiced on a mannequin with feedback. The neurology residents completed the checklist-style pretest and performed an LP on a mannequin. Internal medicine residents were found to increase their pretest scores from a mean of 46.3% to 95.7% following training, whereas neurology residents scored a mean of 65.4%. More than half of neurology residents were unable to identify the correct anatomic location or standard cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) tests to be ordered on a routine LP.28

A pediatric resident study in Canada found that following simulation-based training, LP procedural skill improved in 15 of 16 residents tested, and PGY-1 residents showed a reduction in anxiety related to performing the procedure.29

Virtual Reality

An additional tool for simulation is the use of virtual reality (VR) in combination with mannequins. A French study used videos of LPs on actual patients, from equipment set up to final CSF collection and termination of the procedure.30 These videos included a 360-degree view of the procedure. The short video was administered through a VR device (the Oculus Go headset by Microsoft) or by a YouTube video (if VR was not desired).

Participants in the study watched the video then performed an LP on a mannequin. Those who used the VR option had minimal adverse effects (eg, low rates of cybersickness, blurred vision, nausea) and high satisfaction regarding their training environment.30Another VR-based program is the vascular intervention system trainer, which allows clinicians to use endovascular devices and simulate procedures such as thrombectomies. VR simulation is used for trainees and to retrain experienced physicians in performance of high-risk procedures.31

Fundoscopic and Ultrasound Simulations

The AR403 eye stimulator device for fundoscopic examinations is a mannequin-based simulation.32 In a single-center, prospective, single-blind study of neurology and pediatric neurology residents, trainees were split into control and intervention groups, with the intervention group receiving simulator training. Both groups received video lectures on fundoscopy techniques. Pre- and postintervention measurements included knowledge, skill, and total scores on the skills assessment. Of the 48 trainees who participated, the intervention group demonstrated significantly higher increases in skills (P = .01) and total (P = .02) scores, although knowledge scores did not improve. The intervention group also reported higher comfort levels, higher confidence, and higher success rates.

Areas that would benefit from simulation training and development include ultrasound training, such as transcranial Doppler evaluation. In a national survey of residents in anesthesia and critical care, trainees reported that simulation was not frequently used in ultrasound training and that bedside teaching was more common. Interestingly, there was a discrepancy between the opinions of residents and program directors. The program directors felt simulation was in fact used (18.2% of program directors reported this vs 5.3% of trainees).33

A new program, the NewroSim (Gaumard), is a computer-based model of cerebral perfusion that may be a useful tool in this setting. It can simulate blood flow velocities, including pathologic ones, both with a mannequin or without.34

Another potential area for development is the use of mannequins to teach botulinum toxin injections for migraine, dystonia and spasticity in a training environment This is typically led by pharmaceutical representatives who are not necessarily clinicians. Residents and fellows may benefit instead from clinician-led education during their training programs.

Simulation in Patient Communication

Simulation provides a realistic environment for teaching rapid decision-making, leadership, and appropriate management of acutely ill neurologic patients; this includes the communication skills needed in response to neurologic injury.35 Simulation can be particularly useful in situations involving brain death determination, where the communication techniques differ significantly from those used in shared decision-making. Simulation provides a low-stakes setting for clinicians to practice the process of brain death determination and communication, leading to improved confidence and knowledge.36

In the context of acute neurologic emergencies, simulation exercises have been used to investigate the consistency of prognostication across a spectrum of neurology physicians. These exercises revealed that acute neuroprognostication is highly variable and often inaccurate among neurology clinicians, suggesting a potential area for improvement through further simulation training.37

FUTURE DIRECTIONS

Simulation education in neurology can be directed towards learners at all levels, including medical students, residents, fellows, nurses, and medical technologists. In addition, simulation has great value to different disciplines, including emergency medicine, intensive care, and psychiatry. In our view simulation is not being used to full potential in neurology.

Simulation can be used to expose clinicians to rare pathology, play an integral role in competency-based evaluations, and serve as the foundation for simulation-based neurology curriculums, teleneurology simulation training programs, and team training for neurologic emergencies.38Another under-recognized aspect of neurology education is teaching interpersonal communication and professionalism. A survey conducted at a neurology department (20 residents and 73 faculty respondents) asked about residents’ comfort level in performing a number of interpersonal communication and professionalism tasks.38 While none of the residents said they were “very uncomfortable” with these tasks, only 1 resident reported being “very comfortable.” In addition, fewer than 50% noted that they had been directly observed by a faculty member while performing these tasks. The results prompted the facility to develop a simulation curriculum that including observation and feedback from 8 objective structured clinical examinations at a simulation center. A standardized professional simulated the role of a patient, caregiver, medical student, or a faculty member. Residents indicated in postsimulation surveys that it was very useful, and a majority voted for the activity to be repeated for future classes.38

Simulation models may also provide a more objective method to evaluate neurology residents. Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education has provided Milestones that are used for assessment of neurology residents. Most of the programs rely on end-of-rotation faculty evaluations. These are subjective evaluations, rely on chance evaluations and may not reflect the exact caliber of a trainee in different clinical situations. Simulation models can serve as alternatives to provide an objective and accurate assessment of resident’s competency in different neurologic scenarios.

In a study of PGY-4 neurology residents from 3 tertiary care academic medical centers were evaluated using simulation-based assessment. Their skills in identifying and managing status epilepticus were assessed via a simulation-based model and compared with clinical experience. No graduating neurology residents were able to meet or exceed the minimum passing score during the testing. It was suggested that end-of-rotation evaluations are inadequate for assigning level of Milestones.24 To move forward with use of simulation-based assessments, these models need to be trialed more extensively and validated.

Morris et al developed simulations for assessment in neurocritical care.39 Ten evaluative simulation cases were developed. Researchers reported on 64 trainee participants in 274 evaluative simulation scenarios. The participants were very satisfied with the cases, found them to be very realistic and appropriately difficult. Interrater reliability was acceptable for both checklist action items and global rating scales. The researchers concluded that they were able to demonstrate validity evidence via the 10 simulation cases for assessment in neurologic emergencies.39 It is the authors’ belief that the future of residents’ competency assessment should include more widespread use of similar simulation models.

Finally, VR and augmented reality (AR) have shown promise in various fields, including neurology. In neurology, these technologies are being explored for applications in rehabilitation, therapy, and medical training. Ongoing research aims to leverage these technologies for improved patient outcomes and medical education. Virtual simulations can recreate neurologic scenarios, allowing learners to interact with 3-dimensional (3D) models of the brain or experience virtual patient cases. AR can enhance traditional learning materials by overlaying digital information onto real-world objects, aiding in the understanding of complex neuroanatomy and medical concepts. These technologies contribute to more engaging and effective neurology education.39In a study of 84 graduate medical students divided into 3 groups, the first group attended a traditional lecture on neuroanatomy, the second group was shown VR-based 3D images, and the third group had a VR-based, interactive and stereoscopic session.40 Groups 2 and 3 showed the highest mean scores in evaluations and differed significantly from Group 1 (P < .05). Groups 2 and 3 did not differ significantly from each other. The researchers concluded that VR-based resources for teaching neuroanatomy fostered significantly higher learning when compared to the traditional methods.40

Clinical simulation is a technique, not a technology, used to replace or amplify real experiences with guided experiences that evoke or replicate substantial aspects of the real world in a fully interactive fashion.1 Simulation is widely used in medical education and spans a spectrum of sophistication, from simple reproduction of isolated body parts to high-fidelity human patient simulators that replicate whole body appearance and variable physiological parameters.2,3

Simulation-based medical education can be a valuable tool for safe health care delivery.4Simulation-based education is typically provided via 5 modalities: mannequins, computer-based mannequins, standardized patients, computer-based simulators, and software-based simulations. Simulation technology increases procedural skill by allowing for deliberate practice in a safe environment.5 Mastery learning is a stringent form of competency-based education that requires trainees to acquire clinical skill measured against a fixed achievement standard.6 In mastery learning, educational practice time varies but results are uniform. This approach improves patient outcomes and is more effective than clinical training alone.7-9

Advanced simulation models are helpful tools for neurologic education and training, especially for emergency department encounters.10 In recent years, advanced simulation models have been applied in various fields of medicine, especially emergency medicine and anesthesia.11-14

Acute neurology

In acute neurologic conditions (eg, stroke, intracerebral hemorrhage, status epilepticus, and neuromuscular respiratory failure) clinical outcomes are highly time dependent; consequently, a reduction in treatment delays can improve patient care. The application of simulation methodology allows trainees to address acute and potentially life-threatening emergencies in a safe, controlled, and reproducible environment. In addition to improving trainees’ knowledge base, simulation also helps to enhance team skills, communication, multidisciplinary collaboration, and leadership. Research has shown that deliberate practice leads to a decrease in clinical errors and improved procedural performance in the operating room.8,15 These results can be extrapolated to acute neurology settings to improve adherence to set protocols, thus streamlining management in acute settings.

Scenarios can be built to teach skills such as eliciting an appropriate history, establishing inclusion or exclusion criteria for the use of certain medications, evaluating neuroimaging and laboratory studies (while avoiding related common pitfalls), and managing treatment complications. Simulation also provides an opportunity for interprofessional education by training nurses and collaborative staff. It can be used to enhance nontechnical skills (eg, communication, situation awareness, decision making, and leadership) that further contribute to patient safety.

Simulation can be performed with the help of mannequins such as the SimMan 3G(Laerdal), which can display neurologic symptoms and physiological findings, or live actors who portray a patient by mimicking focal neurologic deficits.16,17 A briefing familiarizes the trainees with the equipment and explains the simulation process. The documentation and equipment are the same as that which is used in emergency departments or intensive care units.

Once the simulation is completed, a trainee’s performance is checked against a critical action checklist before a debriefing process during which the scenario is reviewed and learning goals are assessed. Immediate feedback is given to trainees to identify weaknesses and the simulation is repeated if multiple critical action items are missed. (Figure).17

RESIDENCY TRAINING

Simulation training in stroke is mandatory in some residency programs for neurology postgraduate year (PGY) 2 residents.18 These simulations are a part of a boot camp for incoming neurology residents after completing an internal medicine internship. The simulation program is not standardized across various training programs. The European Stroke Organization Simulation Committee has published an opinion paper with a consensus of experts about the implementation of simulation techniques in the stroke field.19,20 Residents participating in these mandatory programs are required to complete certification in the National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale (NIHSS) and the modified Rankin Scale, including a pretest that assesses their knowledge of acute stroke protocols prior to live simulation.17 A stepwise algorithm that incorporates faculty specialized in the field is used to evaluate and debrief the simulation.

Stroke vignettes are typically selected by the vascular neurology attending physician to cover thrombolytic therapy (indications and contraindications), mechanical thrombectomy, early arterial blood pressure management, anticoagulant reversal protocols, and management of thrombolytic complications (eg, neurologic worsening). Nursing staff is educated on the acute stroke protocol. Computed tomography (CT) and CT angiography scans are retrieved from teaching files. These are provided as live responses along with pertinent laboratory work, vital signs, and electrocardiogram tracings. Trainee performance is based on adherence to a critical action checklist, which includes (but is not limited to) identification of relative and absolute contraindications of thrombolytic treatments, estimation of NIHSS within 5 minutes of arrival, and consideration of candidacy for endovascular intervention.17

EVIDENCE FOR SIMULATION TRAINING

Simulations for acute ischemic stroke also improve cohesive teamwork to improve the door-to-needle and door-to-puncture time. A retrospective analysis involving first-year neurology residents at a comprehensive stroke center that compared patient cohort data before and after implementation of simulation training found that there was an improvement in door-to-needle time after implementation of stroke simulation training program by nearly 10 minutes.17 This was likely due to improvement in the comfort of the flow of management across multidisciplinary teams.

Discussing goals of care, communicating poor prognosis or complex decisions with distraught family members or patients requires practice. Simulation programs with video playback help focus on trainee’s body language, avoiding medical jargon and handling ethical dilemmas while adjusting the communication style to the patient’s personality.20 Enhanced communication skills improve patient satisfaction, trust, and adherence to treatments, all of which lead to better outcomes.21

Simulation has been effectively used as a training tool for recognizing and managing acute neuromuscular respiratory failure. These scenarios emphasize the importance of obtaining a focused clinical history, performing key neurological assessments (such as neck flexion strength and breath counting), evaluating pulmonary function tests, and identifying when to initiate ventilatory support.22 In a study designed as a simulation-based learning curriculum for status epilepticus, there was an improvement in the performance of PGY-2 residents after completing the curriculum from a median of 44.2% at pretest to 94.2% at posttest.23 In this curriculum, an emphasis was placed on the following: recognizing the delay in identification and treatment of status epilepticus; evaluating contraindications of certain antiseizure medication (ASM) based on history or laboratory work; giving first-line ASM within 5 minutes of seizure onset; airway and blood pressure assessment; suctioning the patient; use of second-line ASMs after first-line has failed; ordering a head CT and re-evaluating the case with postload ASM level; ordering a stat electroencephalography (EEG); and communicating the decision regarding patient disposition/level of care.24

There is a growing need for well designed simulation education programs targeted at the management of disorders requiring acute neurologic care, including not only stroke and status epilepticus, but also traumatic brain injury, subarachnoid hemorrhage, neuromuscular respiratory failure, flare of multiple sclerosis, acutely elevated intracranial pressure, malignant cerebral infarction, deterioration of Parkinson disease, and brain death evaluation with family counseling.25 This novel approach to teaching provides an opportunity to learn in addition to remediation with repetition of scenario and might be used for maintenance of recertification programs.

PROCEDURAL SKILLs

Perhaps one of the most studied uses for simulation in neurology is in procedural skills. This extends beyond neurology trainees and can include pulmonary critical care fellows, pediatric residents, and internal medicine residents receiving training in neurology-based procedures such as lumbar punctures (LPs). Other examples of neurology procedures and protocols in which simulation has been studied include fundoscopy, brain death evaluation, EEG interpretation in context of status epilepticus, and simulated stroke code responses. Additional procedures that lack research but may benefit from simulation-based training include the use of Doppler ultrasound and botulinum toxin injections practiced on mannequins.

Proficiency in LP procedural skills has been extensively studied by multiple institutions, with trainee levels ranging from medical students to fellows. One study in France enrolled 115 medical students without prior LP experience and randomized them to either a simulation or a control group.26 Those in the simulation group received instruction using a mannequin, and those in the control group received clinical training through hospital rotations. Both groups received an email containing literature-based information on the procedure as well as a self-assessment questionnaire before participating in either educational program.

The study showed that those students who received simulation training had a success rate of 67% on their first LP on a live patient compared with a success rate of 14% in those with traditional training. Students receiving simulation training required less assistance during the procedure from a supervisor and had higher satisfaction rates and confidence in their procedural skills.26

Another study of 128 medical students at the University of Pittsburgh found that a hybrid LP simulation significantly improved students’ confidence and perceived skill in performing LPs, obtaining informed consent, and electronic order entry. For example, confidence with LP increased from 5.95% presimulation to 90% postsimulation, with 58.24% of students reporting an improvement from minimal or no confidence to average or better (P < .001). Similarly, the proportion of students who felt able to perform LP with minimal or no assistance rose from 0% to 38.57% (P < .001). Confidence and perceived skill in obtaining informed consent and electronic order entry also saw significant gains. Although real-world skill assessments were limited by low survey response rates, preceptor evaluations and follow-up surveys suggested that students who participated in the simulation were more likely to perform these tasks independently or with minimal supervision during clinical rotations.27

Research on simulation training involving nonneurology residents is also encouraging. One study compared the LP skills of traditionally trained neurology residents (PGY-2 to PGY-4) to internal medicine residents (PGY-1) who underwent simulation on a mannequin.28 The internal medicine residents first underwent a pretest on LP performance, watched an educational video, underwent an LP demonstration, and practiced on a mannequin with feedback. The neurology residents completed the checklist-style pretest and performed an LP on a mannequin. Internal medicine residents were found to increase their pretest scores from a mean of 46.3% to 95.7% following training, whereas neurology residents scored a mean of 65.4%. More than half of neurology residents were unable to identify the correct anatomic location or standard cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) tests to be ordered on a routine LP.28

A pediatric resident study in Canada found that following simulation-based training, LP procedural skill improved in 15 of 16 residents tested, and PGY-1 residents showed a reduction in anxiety related to performing the procedure.29

Virtual Reality

An additional tool for simulation is the use of virtual reality (VR) in combination with mannequins. A French study used videos of LPs on actual patients, from equipment set up to final CSF collection and termination of the procedure.30 These videos included a 360-degree view of the procedure. The short video was administered through a VR device (the Oculus Go headset by Microsoft) or by a YouTube video (if VR was not desired).

Participants in the study watched the video then performed an LP on a mannequin. Those who used the VR option had minimal adverse effects (eg, low rates of cybersickness, blurred vision, nausea) and high satisfaction regarding their training environment.30Another VR-based program is the vascular intervention system trainer, which allows clinicians to use endovascular devices and simulate procedures such as thrombectomies. VR simulation is used for trainees and to retrain experienced physicians in performance of high-risk procedures.31

Fundoscopic and Ultrasound Simulations

The AR403 eye stimulator device for fundoscopic examinations is a mannequin-based simulation.32 In a single-center, prospective, single-blind study of neurology and pediatric neurology residents, trainees were split into control and intervention groups, with the intervention group receiving simulator training. Both groups received video lectures on fundoscopy techniques. Pre- and postintervention measurements included knowledge, skill, and total scores on the skills assessment. Of the 48 trainees who participated, the intervention group demonstrated significantly higher increases in skills (P = .01) and total (P = .02) scores, although knowledge scores did not improve. The intervention group also reported higher comfort levels, higher confidence, and higher success rates.

Areas that would benefit from simulation training and development include ultrasound training, such as transcranial Doppler evaluation. In a national survey of residents in anesthesia and critical care, trainees reported that simulation was not frequently used in ultrasound training and that bedside teaching was more common. Interestingly, there was a discrepancy between the opinions of residents and program directors. The program directors felt simulation was in fact used (18.2% of program directors reported this vs 5.3% of trainees).33

A new program, the NewroSim (Gaumard), is a computer-based model of cerebral perfusion that may be a useful tool in this setting. It can simulate blood flow velocities, including pathologic ones, both with a mannequin or without.34

Another potential area for development is the use of mannequins to teach botulinum toxin injections for migraine, dystonia and spasticity in a training environment This is typically led by pharmaceutical representatives who are not necessarily clinicians. Residents and fellows may benefit instead from clinician-led education during their training programs.

Simulation in Patient Communication

Simulation provides a realistic environment for teaching rapid decision-making, leadership, and appropriate management of acutely ill neurologic patients; this includes the communication skills needed in response to neurologic injury.35 Simulation can be particularly useful in situations involving brain death determination, where the communication techniques differ significantly from those used in shared decision-making. Simulation provides a low-stakes setting for clinicians to practice the process of brain death determination and communication, leading to improved confidence and knowledge.36

In the context of acute neurologic emergencies, simulation exercises have been used to investigate the consistency of prognostication across a spectrum of neurology physicians. These exercises revealed that acute neuroprognostication is highly variable and often inaccurate among neurology clinicians, suggesting a potential area for improvement through further simulation training.37

FUTURE DIRECTIONS

Simulation education in neurology can be directed towards learners at all levels, including medical students, residents, fellows, nurses, and medical technologists. In addition, simulation has great value to different disciplines, including emergency medicine, intensive care, and psychiatry. In our view simulation is not being used to full potential in neurology.

Simulation can be used to expose clinicians to rare pathology, play an integral role in competency-based evaluations, and serve as the foundation for simulation-based neurology curriculums, teleneurology simulation training programs, and team training for neurologic emergencies.38Another under-recognized aspect of neurology education is teaching interpersonal communication and professionalism. A survey conducted at a neurology department (20 residents and 73 faculty respondents) asked about residents’ comfort level in performing a number of interpersonal communication and professionalism tasks.38 While none of the residents said they were “very uncomfortable” with these tasks, only 1 resident reported being “very comfortable.” In addition, fewer than 50% noted that they had been directly observed by a faculty member while performing these tasks. The results prompted the facility to develop a simulation curriculum that including observation and feedback from 8 objective structured clinical examinations at a simulation center. A standardized professional simulated the role of a patient, caregiver, medical student, or a faculty member. Residents indicated in postsimulation surveys that it was very useful, and a majority voted for the activity to be repeated for future classes.38

Simulation models may also provide a more objective method to evaluate neurology residents. Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education has provided Milestones that are used for assessment of neurology residents. Most of the programs rely on end-of-rotation faculty evaluations. These are subjective evaluations, rely on chance evaluations and may not reflect the exact caliber of a trainee in different clinical situations. Simulation models can serve as alternatives to provide an objective and accurate assessment of resident’s competency in different neurologic scenarios.

In a study of PGY-4 neurology residents from 3 tertiary care academic medical centers were evaluated using simulation-based assessment. Their skills in identifying and managing status epilepticus were assessed via a simulation-based model and compared with clinical experience. No graduating neurology residents were able to meet or exceed the minimum passing score during the testing. It was suggested that end-of-rotation evaluations are inadequate for assigning level of Milestones.24 To move forward with use of simulation-based assessments, these models need to be trialed more extensively and validated.

Morris et al developed simulations for assessment in neurocritical care.39 Ten evaluative simulation cases were developed. Researchers reported on 64 trainee participants in 274 evaluative simulation scenarios. The participants were very satisfied with the cases, found them to be very realistic and appropriately difficult. Interrater reliability was acceptable for both checklist action items and global rating scales. The researchers concluded that they were able to demonstrate validity evidence via the 10 simulation cases for assessment in neurologic emergencies.39 It is the authors’ belief that the future of residents’ competency assessment should include more widespread use of similar simulation models.

Finally, VR and augmented reality (AR) have shown promise in various fields, including neurology. In neurology, these technologies are being explored for applications in rehabilitation, therapy, and medical training. Ongoing research aims to leverage these technologies for improved patient outcomes and medical education. Virtual simulations can recreate neurologic scenarios, allowing learners to interact with 3-dimensional (3D) models of the brain or experience virtual patient cases. AR can enhance traditional learning materials by overlaying digital information onto real-world objects, aiding in the understanding of complex neuroanatomy and medical concepts. These technologies contribute to more engaging and effective neurology education.39In a study of 84 graduate medical students divided into 3 groups, the first group attended a traditional lecture on neuroanatomy, the second group was shown VR-based 3D images, and the third group had a VR-based, interactive and stereoscopic session.40 Groups 2 and 3 showed the highest mean scores in evaluations and differed significantly from Group 1 (P < .05). Groups 2 and 3 did not differ significantly from each other. The researchers concluded that VR-based resources for teaching neuroanatomy fostered significantly higher learning when compared to the traditional methods.40

- Corvetto M, Bravo MP, Montaña R, et al. Simulación en educación médica: una sinopsis. Rev Med Chil. 2013;141:70-79. doi:10.4067/S0034-98872013000100010

- Lane JL, Slavin S, Ziv A. Simulation in medical education: a review. Simul Gaming. 2001;32:297-314. doi:10.1177/104687810103200302

- Bradley P. The history of simulation in medical education and possible future directions. Med Educ. 2006;40:254-262. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2929.2006.02394.x

- Jones F, Passos-Neto C, Melro Braghiroli O. Simulation in medical education: brief history and methodology. Princ Pract Clin Res J. 2015;1:46-54. doi:10.21801/ppcrj.2015.12.8

- Issenberg SB. Simulation technology for health care professional skills training and assessment. JAMA. 1999;28:861-866. doi:10.1001/jama.282.9.861

- McGaghie WC, Miller GE, Sajid AW, et al. Competency-based curriculum development on medical education: an introduction. Public Health Pap. 1978;68:11-91.

- Barsuk JH, Cohen ER, Feinglass J, et al. Use of simulation-based education to reduce catheter-related bloodstream infections. Arch Intern Med. 2009;169:1420-1423. doi:10.1001/archinternmed.2009.215

- Wayne DB, Didwania A, Feinglass J, et al. Simulation-based education improves quality of care during cardiac arrest team responses at an academic teaching hospital: a case-control study. Chest. 2008;133:56-61. doi:10.1378/chest.07-0131

- McGaghie WC, Issenberg SB, Cohen ER, et al. Does simulation-based medical education with deliberate practice yield better results than traditional clinical education? A meta-analytic comparative review of the evidence. Acad Med. 2011;86:706-711. doi:10.1097/ACM.0b013e318217e119

- Micieli G, Cavallini A, Santalucia P, et al. Simulation in neurology. Neurol Sci. 2015;36:1967-1971. doi:10.1007/s10072-015-2228-8

- Bond WF, Lammers RL, Spillane LL, et al. The use of simulation in emergency medicine: a research agenda. Acad Emerg Med. 2007;14:353-363. doi:10.1197/j.aem.2006.11.02112.

- McLaughlin SA, Doezema D, Sklar DP. Human simulation in emergency medicine training: a model curriculum. Acad Emerg Med. 2002;9:1310-1318. doi:10.1111/j.1553-2712.2002.tb01593.x

- Howard SK, Gaba DM, Fish KJ, et al. Anesthesia crisis resource management training: teaching anesthesiologists to handle critical incidents. Aviat Space Environ Med. 1992;63:763-770.

- Gaba DM. Anaesthesiology as a model for patient safety in health care. BMJ. 2000;320:785-788. doi:10.1136/bmj.320.7237.785

- Sedlack RE, Kolars JC. Computer simulator training enhances the competency of gastroenterology fellows at colonoscopy: results of a pilot study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2004;99:33-37. doi:10.1111/j.1572-0241.2004.04007.x

- Tchopev ZN, Nelson AE, Hunninghake JC, et al. Curriculum innovations: high-fidelity simulation of acute neurology enhances rising resident confidence: results from a multicohort study. Neurol Educ. 2022;1:e200022. doi:10.1212/ne9.0000000000200022

- Mehta T, Strauss S, Beland D, et al. Stroke simulation improves acute stroke management: a systems-based practice experience. J Grad Med Educ. 2018;10:57-62. doi:10.4300/JGME-D-17-00167.1

- Pergakis MB, Chang WTW, Tabatabai A, et al. Simulation-based assessment of graduate neurology trainees’ performance managing acute ischemic stroke. Neurology. 2021;97:e2414-e2422. doi:10.1212/WNL.0000000000012972

- Casolla B. Simulation for neurology training: acute setting and beyond. Rev Neurol (Paris). 2021;177:1207-1213. doi:10.1016/j.neurol.2021.03.008

- Casolla B, de Leciñana MA, Neves R, et al. Simulation training programs for acute stroke care: Objectives and standards of methodology. Eur Stroke J. 2020;5:328-335. doi:10.1177/2396987320971105

- Zolnierek KB, Dimatteo MR. Physician communication and patient adherence to treatment: a meta-analysis. Med Care. 2009;47:826-834.doi:10.1097/MLR.0b013e31819a5acc

- Patel RA, Mohl L, Paetow G, Maiser S. Acute neuromuscular respiratory weakness due to acute inflammatory demyelinating polyneuropathy (AIDP): a simulation scenario for neurology providers. MedEdPORTAL. 2019;15:10811. doi:10.15766/mep_2374-8265.10811

- Mikhaeil-Demo Y, Barsuk JH, Culler GW, et al. Use of a simulation-based mastery learning curriculum for neurology residents to improve the identification and management of status epilepticus. Epilepsy Behav. 2020;111:107247. doi:10.1016/j.yebeh.2020.107247

- Mikhaeil-Demo Y, Holmboe E, Gerard EE, et al. Simulation-based assessments and graduating neurology residents’ milestones: status epilepticus milestones. J Grad Med Educ. 2021;13:223-230. doi:10.4300/JGME-D-20-00832.1

- Hocker S, Wijdicks EFM, Feske SK, et al. Use of simulation in acute neurology training: point and counterpoint. Ann Neurol. 2015;78:337-342. doi:10.1002/ana.24473

- Gaubert S, Blet A, Dib F, et al. Positive effects of lumbar puncture simulation training for medical students in clinical practice. BMC Med Educ. 2021;21:1-6. doi:10.1186/S12909-020-02452-327.

- Yanta C, Knepper L, Van Deusen R, et al. The use of hybrid lumbar puncture simulation to teach entrustable professional activities during a medical student neurology clerkship. MedEdPublish (2016). 2021;9:266. doi:10.15694/mep.2020.000266.2

- Barsuk JH, Cohen ER, Caprio T, et al. Simulation-based education with mastery learning improves residents’ lumbar puncture skills. Neurology. 2012;79:132-137. doi:10.1212/WNL.0B013E31825DD39D

- McMillan HJ, Writer H, Moreau KA, et al. Lumbar puncture simulation in pediatric residency training: improving procedural competence and decreasing anxiety. BMC Med Educ. 2016;16:198. doi:10.1186/S12909-016-0722-1

- Vrillon A, Gonzales-Marabal L, Ceccaldi PF, et al. Using virtual reality in lumbar puncture training improves students learning experience. BMC Med Educ. 2022;22:244. doi:10.1186/S12909-022-03317-7

- Liebig T, Holtmannspötter M, Crossley R, et al. Metric-based virtual reality simulation: a paradigm shift in training for mechanical thrombectomy in acute stroke. Stroke. 2018;49:e239-e242.doi:10.1161/STROKEAHA.118.021089

- Gupta DK, Khandker N, Stacy K, et al. Utility of combining a simulation-based method with a lecture-based method for fundoscopy training in neurology residency. JAMA Neurol. 2017;74:1223-1227. doi:10.1001/JAMANEUROL.2017.2073

- Mongodi S, Bonomi F, Vaschetto R, et al. Point-of-care ultrasound training for residents in anaesthesia and critical care: results of a national survey comparing residents and training program directors’ perspectives. BMC Med Educ. 2022;22:647. doi:10.1186/S12909-022-03708-W

- Morris NA, Czeisler BM, Sarwal A. Simulation in neurocritical care: past, present, and future. Neurocrit Care. 2019;30:522-533. doi:10.1007/S12028-018-0629-2

- Wijdicks EFM, Hocker SE. A future for simulation in acute neurology. Semin Neurol. 2018;38:465-470. doi:10.1055/s-0038-1666986