User login

Transitioning GI patients from pediatric to adult care

As pediatric patients with chronic gastrointestinal (GI) disorders mature into adulthood, they require a seamless transition of care into an adult practice. Health care transition is more than a simple transfer of care to an adult provider; it is a purposeful, planned movement of young adults with chronic medical conditions from a child-centered health care system to adult-oriented one.1 Many adolescents with chronic GI disorders are at increased risk of developmental and psychosocial delays and depressive disorders.2-6 A successful transition program can mitigate some of the psychosocial impacts of chronic disorders by improving self-efficacy and autonomy.7

Timing of transition

Unlike other nations where legislation often mandates the age of transition to adult care, the United States leaves decisions about the appropriate time to transition to the discretion of individual patients and pediatricians. While the actual transfer of care may not happen until later, it is prudent to start planning when the patient is in early adolescence. The pediatric gastroenterologist should initiate the discussion with patients and caregivers when the child is 13-15 years of age.12,13 Since health care transition is a complex and lengthy process, it should be approached within a framework that is appropriate for the developmental stage of the patient and at a time when their disease is in remission.14

During the initial discussions, the idea of transition should be introduced to the patient and his or her family by emphasizing the benefits of improved self-management skills, adherence to therapy, and normalization of development. The pediatrician should encourage a greater sense of independence and self-reliance by seeing the patient alone for at least a portion of the clinic visit and encourage future independent visits.

Developing a transition plan

Once the concept of transition of care has been introduced, it is prudent to devise a transition plan tailored to the specific needs and goals of the patient and family.24 Each plan should include who the adult provider will be, the tasks the adolescent must master before entering adult care, and how the care will be financed (because insurance coverage and options may change).25 A well-planned transition should enhance self-efficacy and self-management skills, increase knowledge of medical states, ensure adherence to therapy, and encourage independent decision making.12

Assessing transition readiness

Once the process of transitioning has been initiated, it is helpful to assess transition readiness at regular intervals. This will identify gaps in knowledge and inform appropriate interventions for individual patients. There are several questionnaires that can be administered at regular intervals and be made an integral part of routine clinic visits for adolescent patients. These assessments are now billable under CPT Code 99420 (administration and interpretation of health risk assessment). A standardized instrument should be used and the results recorded in the clinical encounter to ensure billing compliance.

The Transition Readiness Assessment Questionnaire (available online at www.GotTransition.org) is a validated tool that assesses an individual’s awareness of his or her medical needs, treatment plan, and ability to communicate effectively with his or her health care provider.26-28 While not specific to GI disorders, it has been validated in IBD patients and shown to correlate well with the IBD Self-Efficacy Scale for Adolescents.29,30 The University of North Carolina’s TRxANSITION Index, as well as the Social-Ecological Model of Adolescent and Young Adult Readiness for Transition, can be used for patients with various chronic diseases.31,32 Instruments specifically developed to assess transition readiness among patients with IBD include the “IBD-Yourself” questionnaire and MyHealth Passport for IBD.33,34 Additionally, Hait et al. provide a checklist of age-appropriate tasks for patients and their providers.14 The North American Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition has created the “Healthcare Provider Transition Checklist,” which is applicable to all chronic GI disorders.35

Transfer of care

The actual transfer of care is the culmination of the transition process. While the onus of initiating and monitoring a patient’s progress is driven by his or her pediatric provider, a responsive adult provider is integral, so it is vital to identify an adult gastroenterologist ahead of time. This can be especially difficult because most adult gastroenterologists feel uncomfortable about addressing adolescent developmental and mental health issues.36

Local chapters of societies such as the Crohn’s and Colitis Foundation, the American Liver Foundation, and statewide GI societies affiliated with the American College of Gastroenterology, as well as local or regional teaching institutions, are all good resources to identify adult providers interested in a coordinated transition of young adults into their practices. Depending on the availability of a local adult gastroenterologist, one approach to minimize the “growing pains” of transition can be to establish joint clinic visits with pediatric and adult providers; this strategy can help foster trust in the new physician and is generally well-received by patients.37,38 Other institutions may offer alternating visits with adult and pediatric providers during the first year of transition.

Regardless of the manner of the actual transfer of care, it is imperative the adult gastroenterologist be well versed with the natural history and disease complications of the pediatric onset of the specific GI disorder and also appreciate nutrition and concerns regarding growth and radiation. Moreover, they must recognize the convergence and divergence of traditional pediatric and adult care models, as well as the move from a family-centered to an individual-focused environment.39

At the time of the patient’s initial visit, the adult gastroenterologist needs a detailed history of the patient’s disease, a list of past and present medications, the details of any disease- or treatment-related complications or surgeries, and so on. The transfer of relevant medical records is an often overlooked, yet easily remediable, aspect of transfer of care.36 The overall process is best completed by eliciting posttransfer feedback from patients and families after they have established care with the adult provider.

Developing a transition model

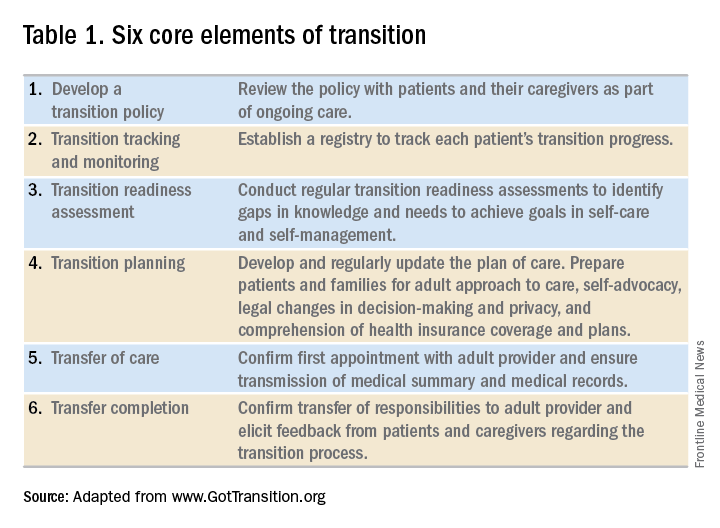

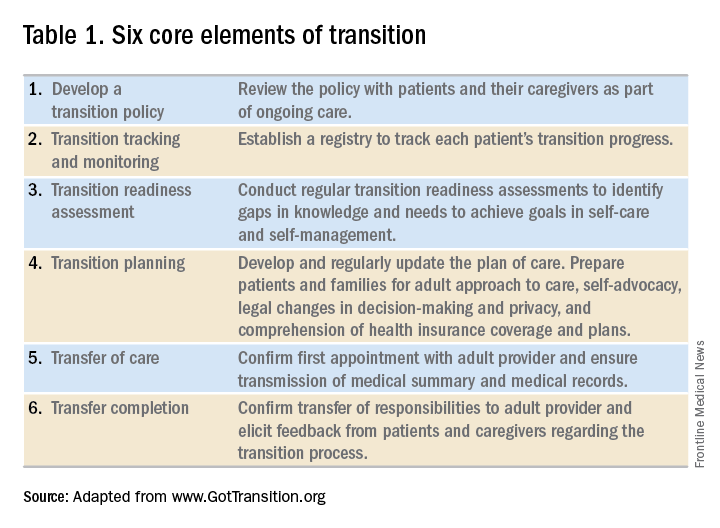

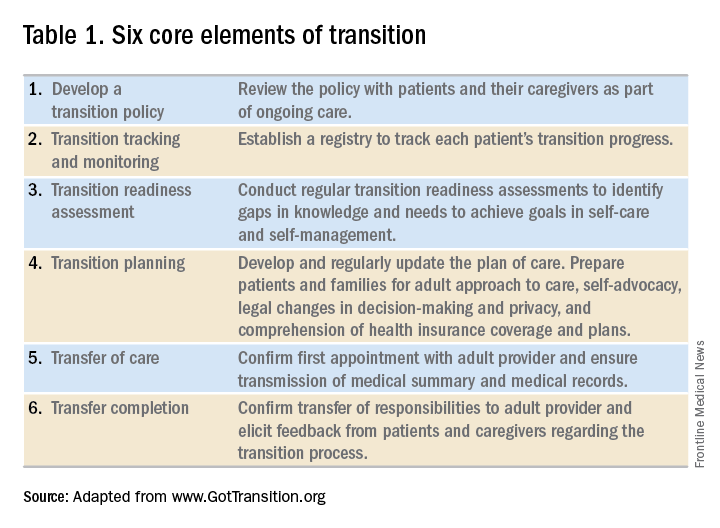

In the absence of standard, disease-specific models of transition, most institutions adapt available resources to develop their own protocols. In 2011, a joint task force of the American Academy of Pediatrics, the American Academy of Family Physicians, and the American College of Physicians published a clinical report on transition. Based on recommendations put forth by the Center for Health Care Transition Improvement – a joint endeavor of the Maternal and Child Health Bureau and the National Alliance to Advance Adolescent Health – the aforementioned task force developed a “Got Transition” model that incorporates six core elements of health care transition (Table 1).

Within the realm of chronic GI disorders, IBD has the most reported data on various models of transition. These include joint adult and pediatric visits, coordinator-initiated transitions, and patient preparation using the assessment tools detailed above. There are no data comparing the efficacy and success of these models and, in the absence of a universally established model for transition in IBD, each institution needs to adopt an approach that best suits the needs of patients and utilizes available resources.

As is the case for patients with IBD, patients with celiac disease need to assume exclusive responsibility for their care as young adults. An important aspect of transition planning for patients with celiac disease is the need to incorporate dietician-led didactic sessions during the transition process. Since patients with celiac disease do not require medications to manage their disease, they are often lost to follow-up as young adults.40 In addition to dietary compliance, it is important to educate young adults about the long-term complications related to celiac disease and the need for regular clinical assessment and monitoring.

Transition of care for patients with EoE is relatively understudied. As EoE was first described only in the 1990s, the diagnosis is still relatively new, and transition programs are limited.41 The natural history and progression of EoE had led to disparate management strategies in adults and children. While the latter are managed with dietary modifications and steroids, adults with EoE often require frequent esophageal dilations because of the increased incidence of fibrosis. In a study of pediatric patients with EoE, most scored lower on transition readiness assessments than did patients with other chronic health conditions.42 Since a majority of patients with EoE require lifelong treatment, they need to be better prepared for transition to adult care.43

In summary, regardless of disease state, transition of care requires planning on the part of the pediatric provider and also close collaboration with patient coordinators, nurses, social workers, and adult providers. While transition is often a complex and lengthy process, it fosters self-reliance and independence among patients while improving their quality of life. Effective communication between pediatric and adult providers as well as patients and families is key to successful transition of care.

Dr. Kaur is the medical director at the Inflammatory Bowel Disease Center and an assistant professor in the section of gastroenterology and hepatology in the department of medicine at Baylor College of Medicine, Houston; Dr. Wyatt is an assistant professor in the section of gastroenterology, hepatology, and nutrition in the department of pediatrics at Baylor.

References

1. Blum RW et al. J Adolesc Health. 1993 Nov;14(7):570-6.

2. Greenley RN et al. J Pediatr Psychol. 2010 Sep;35(8):857-69.

3. Simsek S et al. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2015 Sep;61(3):303-6.

4. Kanof ME et al. Gastroenterology. 1988 Dec;95(6):1523-7.

5. Mackner LM et al. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2006 Mar;12(3):239-44.

6. Hummel TZ et al. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2013 Aug;57(2):219-24.

7. Rosen DS et al. J Adolesc Health. 2003 Oct;33(4):309-11.

8. Bollegala N et al. J Crohns Colitis. 2013 Mar;7(2):e55-60.

9. Reed-Knight B et al. J Pediatr Psychol. 2011 Apr;36(3):308-17.

10. Holmes-Walker DJ et al. Diabet Med. 2007 Jul;24(7):764-9.

11. Dabadie A et al. Gastroenterol Clin Biol. 2008 May;32(5 Pt 1):451-9.

12. A consensus statement on health care transitions for young adults with special health care needs. Pediatrics. 2002 Dec;110(6 Pt 2):1304-6.

13. Baldassano R et al. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2002 Mar;34(3):245-8.

14. Hait E et al. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2006 Jan;12(1):70-3.

15. Gray WN et al. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2015 May;21(5):1125-31.

16. Whitfield EP et al. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2015 Jan;60(1):36-41.

17. Rosen D et al. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2016 Mar;22(3):702-8.

18. Fishman LN et al. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2014 Aug;59(2):221-4.

19. Huang JS et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012 Jun;10(6):626-32.

20. Habibi H et al. Clin Nurse Spec. 2017 Nov;31(6):329-34.

21. Yerushalmy-Feler A et al. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017 Jul;29(7):831-7.

22. Shanske S et al. Soc Work Health Care. 2012;51(4):279-95.

23. Fredericks EM et al. J Clin Psychol Med Settings. 2015 Sep;22(2-3):150-9.

24. Hardin AP et al. Pediatrics. 2017. doi: 10.1542/peds.2017-2151.

25. Leung Y et al. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2011 Oct;17(10):2169-73.

26. Wood DL et al. Acad Pediatr. 2014 Jul-Aug;14(4):415-22.

27. Sample Transition Readiness Assessment for Youth. Got Transition/Center for Health Care Transition Improvement, Jan 2014. Accessed Jan 4, 2017, at http://www.gottransition.org/resourceGet.cfm?id=224.

28. Sawicki GS et al. J Pediatr Psychol. 2011 Mar;36(2):160-71.

29. Izaguirre MR et al. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2017 Nov;65(5):546-50.

30. Carlsen K et al. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2017 Mar;23(3):341-6.

31. Ferris ME et al. Ren Fail. 2012;34(6):744-53.

32. Schwartz LA et al. Child Care Health Dev. 2011 Nov;37(6):883-95.

33. Zijlstra M et al. J Crohns Colitis. 2013 Oct;7(9):e375-85.

34. Benchimol EI et al. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2011 May;17(5):1131-7.

35. Heath Care Provider Transitioning Checklist. NASPGHAN. Accessed Jan 4, 2018, at https://www.naspghan.org/files/documents/pdfs/medical-resources/ibd/Checklist_PatientandHealthcareProdiver_TransitionfromPedtoAdult.pdf.

36. Hait EJ et al. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2009 Jan;48(1):61-5.

37. Escher JC. Dig Dis. 2009;27(3):382-6.

38. Crowley R et al. Arch Dis Child. 2011 Jun;96(6):548-53.

39. Trivedi I et al. Gastroenterol Res Pract. 2015;2015:260807.

40. O’Leary C et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2004 Dec;99(12):2437-41.

41. de Silva PSA et al. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2017 Jun;64(3):707-20.

42. Eluri S et al. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2017 Jul;65(1):53-7.

43. Dellon ES et al. Dis Esophagus. 2013 Jan;26(1):7-13.

As pediatric patients with chronic gastrointestinal (GI) disorders mature into adulthood, they require a seamless transition of care into an adult practice. Health care transition is more than a simple transfer of care to an adult provider; it is a purposeful, planned movement of young adults with chronic medical conditions from a child-centered health care system to adult-oriented one.1 Many adolescents with chronic GI disorders are at increased risk of developmental and psychosocial delays and depressive disorders.2-6 A successful transition program can mitigate some of the psychosocial impacts of chronic disorders by improving self-efficacy and autonomy.7

Timing of transition

Unlike other nations where legislation often mandates the age of transition to adult care, the United States leaves decisions about the appropriate time to transition to the discretion of individual patients and pediatricians. While the actual transfer of care may not happen until later, it is prudent to start planning when the patient is in early adolescence. The pediatric gastroenterologist should initiate the discussion with patients and caregivers when the child is 13-15 years of age.12,13 Since health care transition is a complex and lengthy process, it should be approached within a framework that is appropriate for the developmental stage of the patient and at a time when their disease is in remission.14

During the initial discussions, the idea of transition should be introduced to the patient and his or her family by emphasizing the benefits of improved self-management skills, adherence to therapy, and normalization of development. The pediatrician should encourage a greater sense of independence and self-reliance by seeing the patient alone for at least a portion of the clinic visit and encourage future independent visits.

Developing a transition plan

Once the concept of transition of care has been introduced, it is prudent to devise a transition plan tailored to the specific needs and goals of the patient and family.24 Each plan should include who the adult provider will be, the tasks the adolescent must master before entering adult care, and how the care will be financed (because insurance coverage and options may change).25 A well-planned transition should enhance self-efficacy and self-management skills, increase knowledge of medical states, ensure adherence to therapy, and encourage independent decision making.12

Assessing transition readiness

Once the process of transitioning has been initiated, it is helpful to assess transition readiness at regular intervals. This will identify gaps in knowledge and inform appropriate interventions for individual patients. There are several questionnaires that can be administered at regular intervals and be made an integral part of routine clinic visits for adolescent patients. These assessments are now billable under CPT Code 99420 (administration and interpretation of health risk assessment). A standardized instrument should be used and the results recorded in the clinical encounter to ensure billing compliance.

The Transition Readiness Assessment Questionnaire (available online at www.GotTransition.org) is a validated tool that assesses an individual’s awareness of his or her medical needs, treatment plan, and ability to communicate effectively with his or her health care provider.26-28 While not specific to GI disorders, it has been validated in IBD patients and shown to correlate well with the IBD Self-Efficacy Scale for Adolescents.29,30 The University of North Carolina’s TRxANSITION Index, as well as the Social-Ecological Model of Adolescent and Young Adult Readiness for Transition, can be used for patients with various chronic diseases.31,32 Instruments specifically developed to assess transition readiness among patients with IBD include the “IBD-Yourself” questionnaire and MyHealth Passport for IBD.33,34 Additionally, Hait et al. provide a checklist of age-appropriate tasks for patients and their providers.14 The North American Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition has created the “Healthcare Provider Transition Checklist,” which is applicable to all chronic GI disorders.35

Transfer of care

The actual transfer of care is the culmination of the transition process. While the onus of initiating and monitoring a patient’s progress is driven by his or her pediatric provider, a responsive adult provider is integral, so it is vital to identify an adult gastroenterologist ahead of time. This can be especially difficult because most adult gastroenterologists feel uncomfortable about addressing adolescent developmental and mental health issues.36

Local chapters of societies such as the Crohn’s and Colitis Foundation, the American Liver Foundation, and statewide GI societies affiliated with the American College of Gastroenterology, as well as local or regional teaching institutions, are all good resources to identify adult providers interested in a coordinated transition of young adults into their practices. Depending on the availability of a local adult gastroenterologist, one approach to minimize the “growing pains” of transition can be to establish joint clinic visits with pediatric and adult providers; this strategy can help foster trust in the new physician and is generally well-received by patients.37,38 Other institutions may offer alternating visits with adult and pediatric providers during the first year of transition.

Regardless of the manner of the actual transfer of care, it is imperative the adult gastroenterologist be well versed with the natural history and disease complications of the pediatric onset of the specific GI disorder and also appreciate nutrition and concerns regarding growth and radiation. Moreover, they must recognize the convergence and divergence of traditional pediatric and adult care models, as well as the move from a family-centered to an individual-focused environment.39

At the time of the patient’s initial visit, the adult gastroenterologist needs a detailed history of the patient’s disease, a list of past and present medications, the details of any disease- or treatment-related complications or surgeries, and so on. The transfer of relevant medical records is an often overlooked, yet easily remediable, aspect of transfer of care.36 The overall process is best completed by eliciting posttransfer feedback from patients and families after they have established care with the adult provider.

Developing a transition model

In the absence of standard, disease-specific models of transition, most institutions adapt available resources to develop their own protocols. In 2011, a joint task force of the American Academy of Pediatrics, the American Academy of Family Physicians, and the American College of Physicians published a clinical report on transition. Based on recommendations put forth by the Center for Health Care Transition Improvement – a joint endeavor of the Maternal and Child Health Bureau and the National Alliance to Advance Adolescent Health – the aforementioned task force developed a “Got Transition” model that incorporates six core elements of health care transition (Table 1).

Within the realm of chronic GI disorders, IBD has the most reported data on various models of transition. These include joint adult and pediatric visits, coordinator-initiated transitions, and patient preparation using the assessment tools detailed above. There are no data comparing the efficacy and success of these models and, in the absence of a universally established model for transition in IBD, each institution needs to adopt an approach that best suits the needs of patients and utilizes available resources.

As is the case for patients with IBD, patients with celiac disease need to assume exclusive responsibility for their care as young adults. An important aspect of transition planning for patients with celiac disease is the need to incorporate dietician-led didactic sessions during the transition process. Since patients with celiac disease do not require medications to manage their disease, they are often lost to follow-up as young adults.40 In addition to dietary compliance, it is important to educate young adults about the long-term complications related to celiac disease and the need for regular clinical assessment and monitoring.

Transition of care for patients with EoE is relatively understudied. As EoE was first described only in the 1990s, the diagnosis is still relatively new, and transition programs are limited.41 The natural history and progression of EoE had led to disparate management strategies in adults and children. While the latter are managed with dietary modifications and steroids, adults with EoE often require frequent esophageal dilations because of the increased incidence of fibrosis. In a study of pediatric patients with EoE, most scored lower on transition readiness assessments than did patients with other chronic health conditions.42 Since a majority of patients with EoE require lifelong treatment, they need to be better prepared for transition to adult care.43

In summary, regardless of disease state, transition of care requires planning on the part of the pediatric provider and also close collaboration with patient coordinators, nurses, social workers, and adult providers. While transition is often a complex and lengthy process, it fosters self-reliance and independence among patients while improving their quality of life. Effective communication between pediatric and adult providers as well as patients and families is key to successful transition of care.

Dr. Kaur is the medical director at the Inflammatory Bowel Disease Center and an assistant professor in the section of gastroenterology and hepatology in the department of medicine at Baylor College of Medicine, Houston; Dr. Wyatt is an assistant professor in the section of gastroenterology, hepatology, and nutrition in the department of pediatrics at Baylor.

References

1. Blum RW et al. J Adolesc Health. 1993 Nov;14(7):570-6.

2. Greenley RN et al. J Pediatr Psychol. 2010 Sep;35(8):857-69.

3. Simsek S et al. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2015 Sep;61(3):303-6.

4. Kanof ME et al. Gastroenterology. 1988 Dec;95(6):1523-7.

5. Mackner LM et al. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2006 Mar;12(3):239-44.

6. Hummel TZ et al. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2013 Aug;57(2):219-24.

7. Rosen DS et al. J Adolesc Health. 2003 Oct;33(4):309-11.

8. Bollegala N et al. J Crohns Colitis. 2013 Mar;7(2):e55-60.

9. Reed-Knight B et al. J Pediatr Psychol. 2011 Apr;36(3):308-17.

10. Holmes-Walker DJ et al. Diabet Med. 2007 Jul;24(7):764-9.

11. Dabadie A et al. Gastroenterol Clin Biol. 2008 May;32(5 Pt 1):451-9.

12. A consensus statement on health care transitions for young adults with special health care needs. Pediatrics. 2002 Dec;110(6 Pt 2):1304-6.

13. Baldassano R et al. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2002 Mar;34(3):245-8.

14. Hait E et al. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2006 Jan;12(1):70-3.

15. Gray WN et al. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2015 May;21(5):1125-31.

16. Whitfield EP et al. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2015 Jan;60(1):36-41.

17. Rosen D et al. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2016 Mar;22(3):702-8.

18. Fishman LN et al. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2014 Aug;59(2):221-4.

19. Huang JS et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012 Jun;10(6):626-32.

20. Habibi H et al. Clin Nurse Spec. 2017 Nov;31(6):329-34.

21. Yerushalmy-Feler A et al. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017 Jul;29(7):831-7.

22. Shanske S et al. Soc Work Health Care. 2012;51(4):279-95.

23. Fredericks EM et al. J Clin Psychol Med Settings. 2015 Sep;22(2-3):150-9.

24. Hardin AP et al. Pediatrics. 2017. doi: 10.1542/peds.2017-2151.

25. Leung Y et al. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2011 Oct;17(10):2169-73.

26. Wood DL et al. Acad Pediatr. 2014 Jul-Aug;14(4):415-22.

27. Sample Transition Readiness Assessment for Youth. Got Transition/Center for Health Care Transition Improvement, Jan 2014. Accessed Jan 4, 2017, at http://www.gottransition.org/resourceGet.cfm?id=224.

28. Sawicki GS et al. J Pediatr Psychol. 2011 Mar;36(2):160-71.

29. Izaguirre MR et al. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2017 Nov;65(5):546-50.

30. Carlsen K et al. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2017 Mar;23(3):341-6.

31. Ferris ME et al. Ren Fail. 2012;34(6):744-53.

32. Schwartz LA et al. Child Care Health Dev. 2011 Nov;37(6):883-95.

33. Zijlstra M et al. J Crohns Colitis. 2013 Oct;7(9):e375-85.

34. Benchimol EI et al. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2011 May;17(5):1131-7.

35. Heath Care Provider Transitioning Checklist. NASPGHAN. Accessed Jan 4, 2018, at https://www.naspghan.org/files/documents/pdfs/medical-resources/ibd/Checklist_PatientandHealthcareProdiver_TransitionfromPedtoAdult.pdf.

36. Hait EJ et al. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2009 Jan;48(1):61-5.

37. Escher JC. Dig Dis. 2009;27(3):382-6.

38. Crowley R et al. Arch Dis Child. 2011 Jun;96(6):548-53.

39. Trivedi I et al. Gastroenterol Res Pract. 2015;2015:260807.

40. O’Leary C et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2004 Dec;99(12):2437-41.

41. de Silva PSA et al. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2017 Jun;64(3):707-20.

42. Eluri S et al. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2017 Jul;65(1):53-7.

43. Dellon ES et al. Dis Esophagus. 2013 Jan;26(1):7-13.

As pediatric patients with chronic gastrointestinal (GI) disorders mature into adulthood, they require a seamless transition of care into an adult practice. Health care transition is more than a simple transfer of care to an adult provider; it is a purposeful, planned movement of young adults with chronic medical conditions from a child-centered health care system to adult-oriented one.1 Many adolescents with chronic GI disorders are at increased risk of developmental and psychosocial delays and depressive disorders.2-6 A successful transition program can mitigate some of the psychosocial impacts of chronic disorders by improving self-efficacy and autonomy.7

Timing of transition

Unlike other nations where legislation often mandates the age of transition to adult care, the United States leaves decisions about the appropriate time to transition to the discretion of individual patients and pediatricians. While the actual transfer of care may not happen until later, it is prudent to start planning when the patient is in early adolescence. The pediatric gastroenterologist should initiate the discussion with patients and caregivers when the child is 13-15 years of age.12,13 Since health care transition is a complex and lengthy process, it should be approached within a framework that is appropriate for the developmental stage of the patient and at a time when their disease is in remission.14

During the initial discussions, the idea of transition should be introduced to the patient and his or her family by emphasizing the benefits of improved self-management skills, adherence to therapy, and normalization of development. The pediatrician should encourage a greater sense of independence and self-reliance by seeing the patient alone for at least a portion of the clinic visit and encourage future independent visits.

Developing a transition plan

Once the concept of transition of care has been introduced, it is prudent to devise a transition plan tailored to the specific needs and goals of the patient and family.24 Each plan should include who the adult provider will be, the tasks the adolescent must master before entering adult care, and how the care will be financed (because insurance coverage and options may change).25 A well-planned transition should enhance self-efficacy and self-management skills, increase knowledge of medical states, ensure adherence to therapy, and encourage independent decision making.12

Assessing transition readiness

Once the process of transitioning has been initiated, it is helpful to assess transition readiness at regular intervals. This will identify gaps in knowledge and inform appropriate interventions for individual patients. There are several questionnaires that can be administered at regular intervals and be made an integral part of routine clinic visits for adolescent patients. These assessments are now billable under CPT Code 99420 (administration and interpretation of health risk assessment). A standardized instrument should be used and the results recorded in the clinical encounter to ensure billing compliance.

The Transition Readiness Assessment Questionnaire (available online at www.GotTransition.org) is a validated tool that assesses an individual’s awareness of his or her medical needs, treatment plan, and ability to communicate effectively with his or her health care provider.26-28 While not specific to GI disorders, it has been validated in IBD patients and shown to correlate well with the IBD Self-Efficacy Scale for Adolescents.29,30 The University of North Carolina’s TRxANSITION Index, as well as the Social-Ecological Model of Adolescent and Young Adult Readiness for Transition, can be used for patients with various chronic diseases.31,32 Instruments specifically developed to assess transition readiness among patients with IBD include the “IBD-Yourself” questionnaire and MyHealth Passport for IBD.33,34 Additionally, Hait et al. provide a checklist of age-appropriate tasks for patients and their providers.14 The North American Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition has created the “Healthcare Provider Transition Checklist,” which is applicable to all chronic GI disorders.35

Transfer of care

The actual transfer of care is the culmination of the transition process. While the onus of initiating and monitoring a patient’s progress is driven by his or her pediatric provider, a responsive adult provider is integral, so it is vital to identify an adult gastroenterologist ahead of time. This can be especially difficult because most adult gastroenterologists feel uncomfortable about addressing adolescent developmental and mental health issues.36

Local chapters of societies such as the Crohn’s and Colitis Foundation, the American Liver Foundation, and statewide GI societies affiliated with the American College of Gastroenterology, as well as local or regional teaching institutions, are all good resources to identify adult providers interested in a coordinated transition of young adults into their practices. Depending on the availability of a local adult gastroenterologist, one approach to minimize the “growing pains” of transition can be to establish joint clinic visits with pediatric and adult providers; this strategy can help foster trust in the new physician and is generally well-received by patients.37,38 Other institutions may offer alternating visits with adult and pediatric providers during the first year of transition.

Regardless of the manner of the actual transfer of care, it is imperative the adult gastroenterologist be well versed with the natural history and disease complications of the pediatric onset of the specific GI disorder and also appreciate nutrition and concerns regarding growth and radiation. Moreover, they must recognize the convergence and divergence of traditional pediatric and adult care models, as well as the move from a family-centered to an individual-focused environment.39

At the time of the patient’s initial visit, the adult gastroenterologist needs a detailed history of the patient’s disease, a list of past and present medications, the details of any disease- or treatment-related complications or surgeries, and so on. The transfer of relevant medical records is an often overlooked, yet easily remediable, aspect of transfer of care.36 The overall process is best completed by eliciting posttransfer feedback from patients and families after they have established care with the adult provider.

Developing a transition model

In the absence of standard, disease-specific models of transition, most institutions adapt available resources to develop their own protocols. In 2011, a joint task force of the American Academy of Pediatrics, the American Academy of Family Physicians, and the American College of Physicians published a clinical report on transition. Based on recommendations put forth by the Center for Health Care Transition Improvement – a joint endeavor of the Maternal and Child Health Bureau and the National Alliance to Advance Adolescent Health – the aforementioned task force developed a “Got Transition” model that incorporates six core elements of health care transition (Table 1).

Within the realm of chronic GI disorders, IBD has the most reported data on various models of transition. These include joint adult and pediatric visits, coordinator-initiated transitions, and patient preparation using the assessment tools detailed above. There are no data comparing the efficacy and success of these models and, in the absence of a universally established model for transition in IBD, each institution needs to adopt an approach that best suits the needs of patients and utilizes available resources.

As is the case for patients with IBD, patients with celiac disease need to assume exclusive responsibility for their care as young adults. An important aspect of transition planning for patients with celiac disease is the need to incorporate dietician-led didactic sessions during the transition process. Since patients with celiac disease do not require medications to manage their disease, they are often lost to follow-up as young adults.40 In addition to dietary compliance, it is important to educate young adults about the long-term complications related to celiac disease and the need for regular clinical assessment and monitoring.

Transition of care for patients with EoE is relatively understudied. As EoE was first described only in the 1990s, the diagnosis is still relatively new, and transition programs are limited.41 The natural history and progression of EoE had led to disparate management strategies in adults and children. While the latter are managed with dietary modifications and steroids, adults with EoE often require frequent esophageal dilations because of the increased incidence of fibrosis. In a study of pediatric patients with EoE, most scored lower on transition readiness assessments than did patients with other chronic health conditions.42 Since a majority of patients with EoE require lifelong treatment, they need to be better prepared for transition to adult care.43

In summary, regardless of disease state, transition of care requires planning on the part of the pediatric provider and also close collaboration with patient coordinators, nurses, social workers, and adult providers. While transition is often a complex and lengthy process, it fosters self-reliance and independence among patients while improving their quality of life. Effective communication between pediatric and adult providers as well as patients and families is key to successful transition of care.

Dr. Kaur is the medical director at the Inflammatory Bowel Disease Center and an assistant professor in the section of gastroenterology and hepatology in the department of medicine at Baylor College of Medicine, Houston; Dr. Wyatt is an assistant professor in the section of gastroenterology, hepatology, and nutrition in the department of pediatrics at Baylor.

References

1. Blum RW et al. J Adolesc Health. 1993 Nov;14(7):570-6.

2. Greenley RN et al. J Pediatr Psychol. 2010 Sep;35(8):857-69.

3. Simsek S et al. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2015 Sep;61(3):303-6.

4. Kanof ME et al. Gastroenterology. 1988 Dec;95(6):1523-7.

5. Mackner LM et al. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2006 Mar;12(3):239-44.

6. Hummel TZ et al. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2013 Aug;57(2):219-24.

7. Rosen DS et al. J Adolesc Health. 2003 Oct;33(4):309-11.

8. Bollegala N et al. J Crohns Colitis. 2013 Mar;7(2):e55-60.

9. Reed-Knight B et al. J Pediatr Psychol. 2011 Apr;36(3):308-17.

10. Holmes-Walker DJ et al. Diabet Med. 2007 Jul;24(7):764-9.

11. Dabadie A et al. Gastroenterol Clin Biol. 2008 May;32(5 Pt 1):451-9.

12. A consensus statement on health care transitions for young adults with special health care needs. Pediatrics. 2002 Dec;110(6 Pt 2):1304-6.

13. Baldassano R et al. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2002 Mar;34(3):245-8.

14. Hait E et al. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2006 Jan;12(1):70-3.

15. Gray WN et al. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2015 May;21(5):1125-31.

16. Whitfield EP et al. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2015 Jan;60(1):36-41.

17. Rosen D et al. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2016 Mar;22(3):702-8.

18. Fishman LN et al. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2014 Aug;59(2):221-4.

19. Huang JS et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012 Jun;10(6):626-32.

20. Habibi H et al. Clin Nurse Spec. 2017 Nov;31(6):329-34.

21. Yerushalmy-Feler A et al. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017 Jul;29(7):831-7.

22. Shanske S et al. Soc Work Health Care. 2012;51(4):279-95.

23. Fredericks EM et al. J Clin Psychol Med Settings. 2015 Sep;22(2-3):150-9.

24. Hardin AP et al. Pediatrics. 2017. doi: 10.1542/peds.2017-2151.

25. Leung Y et al. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2011 Oct;17(10):2169-73.

26. Wood DL et al. Acad Pediatr. 2014 Jul-Aug;14(4):415-22.

27. Sample Transition Readiness Assessment for Youth. Got Transition/Center for Health Care Transition Improvement, Jan 2014. Accessed Jan 4, 2017, at http://www.gottransition.org/resourceGet.cfm?id=224.

28. Sawicki GS et al. J Pediatr Psychol. 2011 Mar;36(2):160-71.

29. Izaguirre MR et al. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2017 Nov;65(5):546-50.

30. Carlsen K et al. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2017 Mar;23(3):341-6.

31. Ferris ME et al. Ren Fail. 2012;34(6):744-53.

32. Schwartz LA et al. Child Care Health Dev. 2011 Nov;37(6):883-95.

33. Zijlstra M et al. J Crohns Colitis. 2013 Oct;7(9):e375-85.

34. Benchimol EI et al. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2011 May;17(5):1131-7.

35. Heath Care Provider Transitioning Checklist. NASPGHAN. Accessed Jan 4, 2018, at https://www.naspghan.org/files/documents/pdfs/medical-resources/ibd/Checklist_PatientandHealthcareProdiver_TransitionfromPedtoAdult.pdf.

36. Hait EJ et al. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2009 Jan;48(1):61-5.

37. Escher JC. Dig Dis. 2009;27(3):382-6.

38. Crowley R et al. Arch Dis Child. 2011 Jun;96(6):548-53.

39. Trivedi I et al. Gastroenterol Res Pract. 2015;2015:260807.

40. O’Leary C et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2004 Dec;99(12):2437-41.

41. de Silva PSA et al. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2017 Jun;64(3):707-20.

42. Eluri S et al. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2017 Jul;65(1):53-7.

43. Dellon ES et al. Dis Esophagus. 2013 Jan;26(1):7-13.