User login

Oral Lichen Planus Treated With Plasma Rich in Growth Factors

Lichen planus is a chronic inflammatory mucocutaneous disease that usually affects the skin and/or the genital and oral mucosae.1,2 This disease classically presents with clinical relapses or outbreaks that alternate with periods of remission or latency. Oral lichen planus (OLP) can present with or without extraoral manifestation. It sometimes is difficult to differentiate OLP from oral lichenoid reactions, which can be related to dental materials, some drugs, and systemic conditions or can be idiopathic.1,2

Oral lichen planus is one of the most common noninfectious diseases of the oral cavity, with a reported prevalence of 1% worldwide and marked geographical differences. In Europe, the prevalence of OLP ranges from 1% to 2%.3,4 It is more frequent in women (1.5:1 to 2:1) and usually appears in the fourth and fifth decades of life.1-4

The causes of OLP have not been entirely elucidated, but it is broadly accepted that there is a deregulation on different T lymphocytes that in turn causes effects on CD8 lymphocytes in response to an external noxa. This unknown “trigger” or starting factor also produces an impact on basal keratinocytes. Therefore, the pathogenesis of lichen planus is influenced by a series of cellular events mediated by different cytokines.2,5,6 Among these, tumor necrosis factor α and IL-1 are known to have important roles in the disease. More recently, other cytokines, such as IL-4, secreted by type 2 helper T cells, also have been related to the development and progression of the oral lesions.5,6 In addition to the factors that generate the onset of the disease, there are others that may precipitate clinical outbreaks. Different factors have been related to the progression of the disease, influencing the initiation, perpetuation, and/or worsening of OLP lesions.1,2 Exactly how these factors affect disease progression is another challenging question. The list of possible or potential factors related to disease progression is long; nonetheless, in the vast majority, a clear explanation at a molecular level has not been clearly demonstrated.2,5

Conventionally, 6 clinical presentations of OLP lesions divided into 2 main groups have been described in the oral cavity: white forms (reticular, papular, and plaquelike) and red forms (erythematous, atrophic-erosive, and bullous).1,7-9

Oral lichen planus mainly is treated with topically or systemically administered steroids based on the presence of symptoms such as pain and inability to perform daily activities (eg, eating, talking).5,10 The treatment of choice often is based on the professional’s experience, as there are no broadly accepted national or international clinical practice guidelines on steroid type, administration route, dose, vehicle for administration, or maintenance.11 Despite this lack of unified criteria, different topical and systemic steroid administration protocols allow a reduction in the symptoms or even the disappearance of the red lesions to be achieved in many cases. Unfortunately, there are many patients with lesions refractory to standard treatments for OLP.12 Several alternatives for these patients have been described in the literature, though on many occasions these alternatives present substantial side effects for the patient.13 The search for an effective treatment without side effects is still challenging. One of the treatments tested under this premise has been the application of plasma rich in growth factors (PRGF) by means of infiltration or topical application, in both cases obtaining good results without side effects.14

We sought to analyze the information from a case series of patients treated at the Eduardo Anitua Clinic (Vitoria-Gasteiz, Spain) and describe the results and follow-up of patients with erosive OLP refractory to standard therapy who have been successfully treated by local infiltration of PRGF as the only treatment.

Material and Methods

Patients—We included data from the database of the clinical center with de-identified information of patients with erosive OLP diagnosed clinically and histopathologically who did not respond to conventional treatment (ie, topical and/or systemic corticosteroids [depending on the case]) as well as patients who presented with extensive erosive OLP with systemic involvement and whose systemic treatment was not effective in resolving oral manifestations.

Therapies Administered and Evaluations—Lesions refractory to conventional corticosteroid protocols had been previously treated for 30 days with 0.5% triamcinolone acetonide mouth rinse followed by a cycle of 1% triamcinolone acetonide mouth rinse. Subsequently, a cycle of oral corticosteroids (prednisone for 30 days: 1 mg/kg/d in a single morning dose with staged reduction after the first week) had been administered. One dayafter the corticosteroid treatment was suspended, the patients were treated by PRGF-Endoret (BTI Biotechnology Institute) infiltration following the protocol described by Anitua et al.15,16

Before starting the infiltrations with PRGF, the patient had been asked to rate the pain level on a visual analog scale (VAS) of 1 to 10, with 10 being the most intense imaginable pain. Pain score was subsequently rated and registered during every visit. An initial photograph of the lesion also was obtained to establish a starting point for further comparisons of clinical evolution of the lesions.

Prior to each infiltration, the plasma was separated into 2 fractions. The second fraction was the one that corresponded to the highest number of platelets and included the 2 mL of plasma just above the white series (or buffy coat). This fraction of plasma was the one used to infiltrate the lesions.

Plasma rich in growth factors was activated just before infiltration. The activation was done by adding 10% calcium chloride. Once activated, it was infiltrated into the active lesion using a 31-G × 1/6-in hypodermic needle and a 2-mL Luer-lock syringe. Infiltrations were performed without anesthesia. Four punctures were made for each ulcerative lesion, dividing the lesion into 4 points: upper, lower, right, and left. Plasma rich in growth factors was infiltrated until a slight blanching was observed in the surrounding tissue. At that moment, the infiltration was stopped and was carried out in the next infiltration site.

One treatment session was performed per week, with follow-up 1 week after treatment. In the control visit, the state of the lesions was re-evaluated, and it was decided whether new infiltrations were needed. The treatment was finished when complete epithelialization of the lesion was visualized or the associated symptoms disappeared. At each visit, photographs were taken, and the patient assessed the severity of pain on the VAS.

Statistical Analysis—A Shapiro-Wilk test was carried out with the obtained data to check the normal distribution of the sample. The evolution of pain during the study was compared by paired t test. The qualitative variables were described by means of a frequency analysis. Quantitative variables were described by the mean and the SD. The data were analyzed with SPSS V15.0 for Windows (SPSS Inc). P<.05 showed statistical significance.

Results

A total of 15 patients were included in the study, all with atrophic-erosive lichen planus. Two patients were male, and 13 were female. The mean age (SD) of the patients included in the study was 55.27 (14.19) years. The mean number of outbreaks per year (SD) was 3.2 (1.7), with a range of 1 to 8 outbreaks.

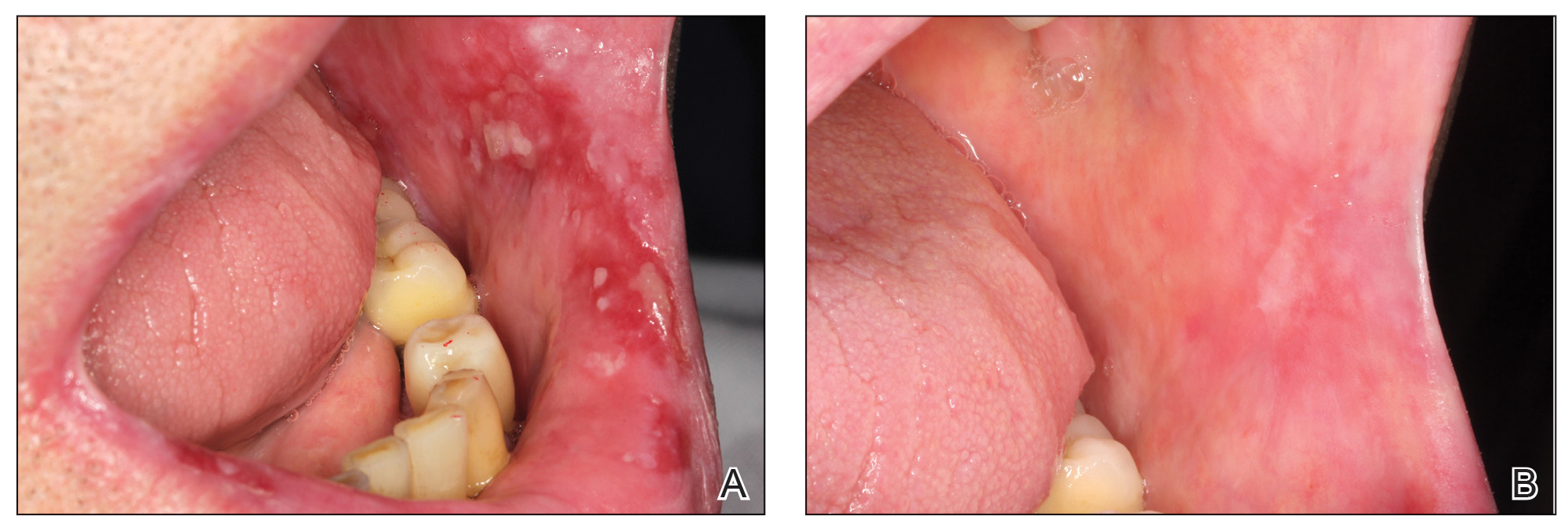

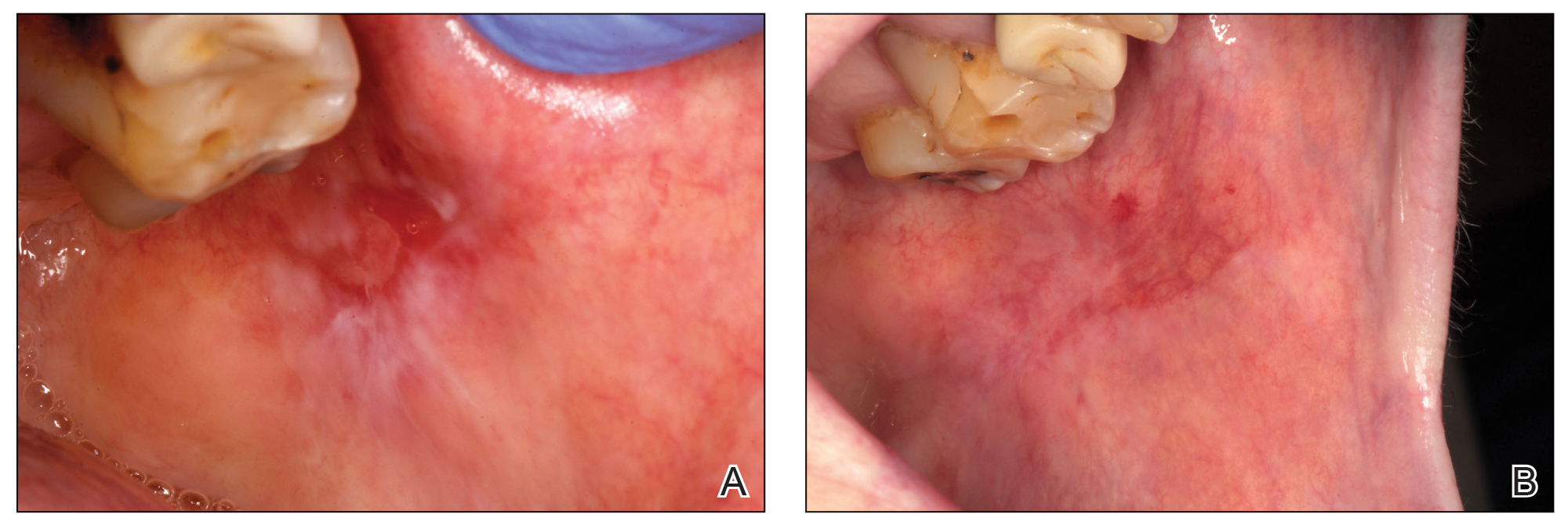

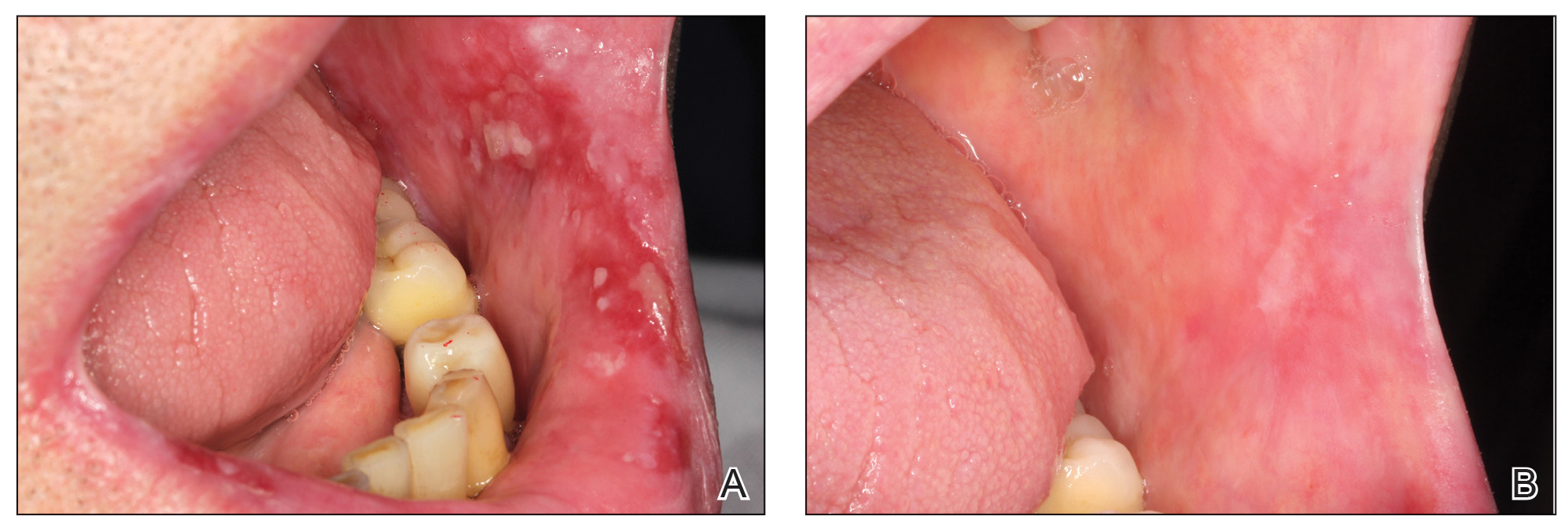

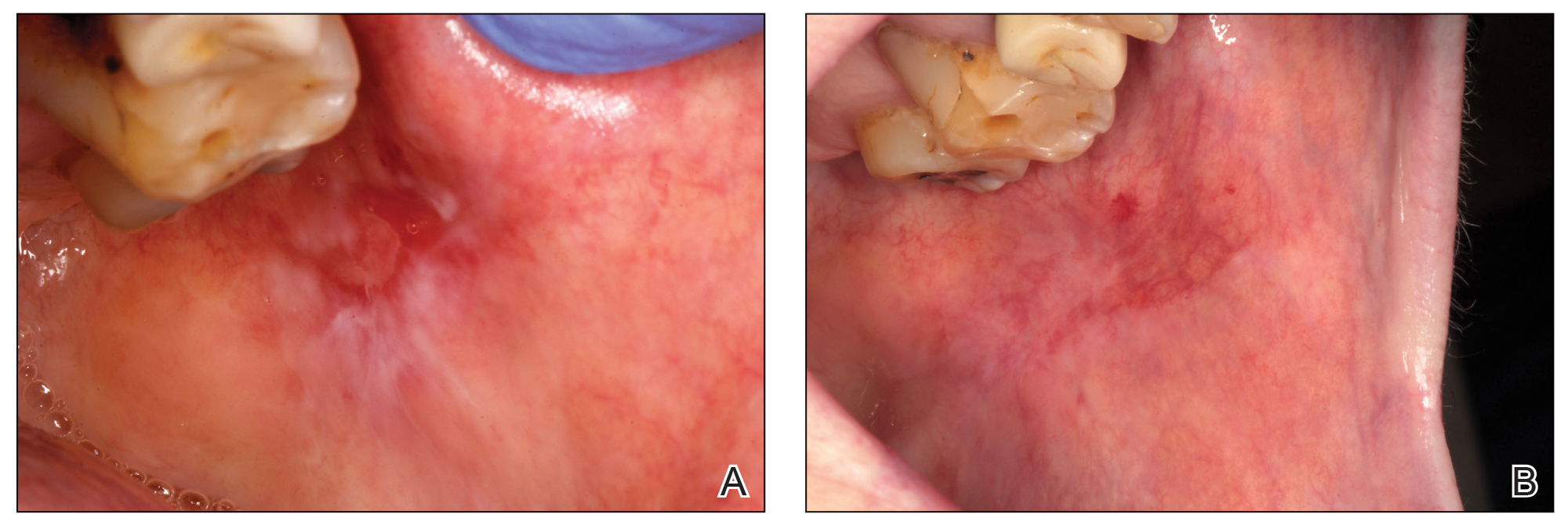

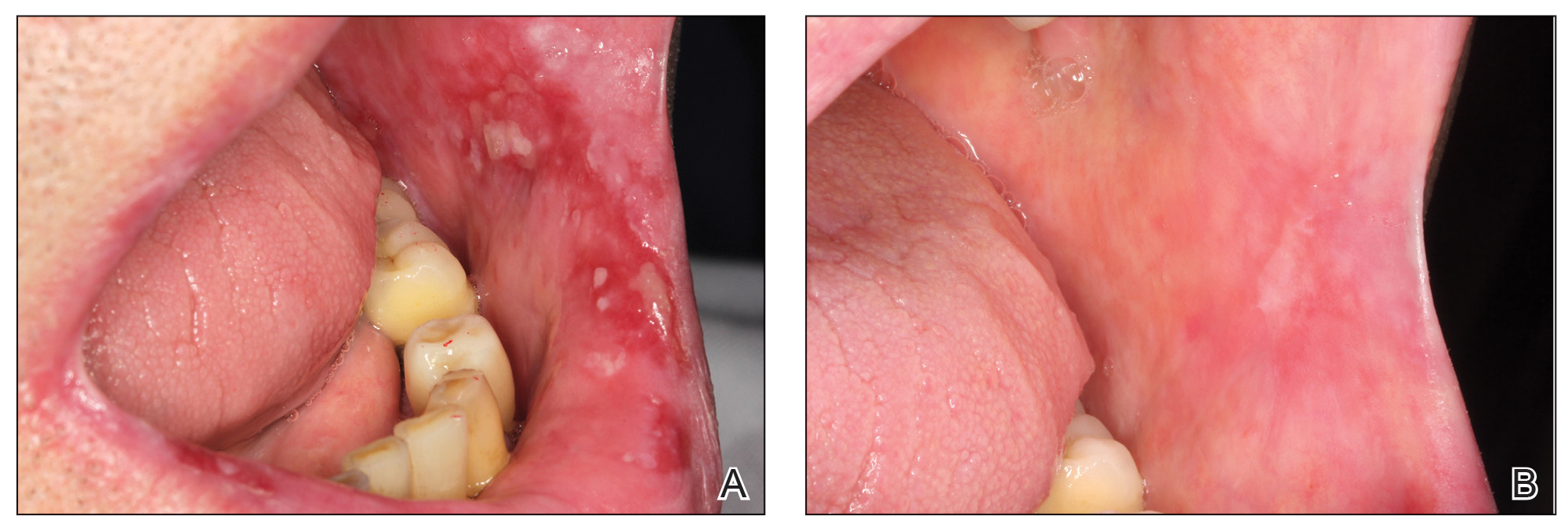

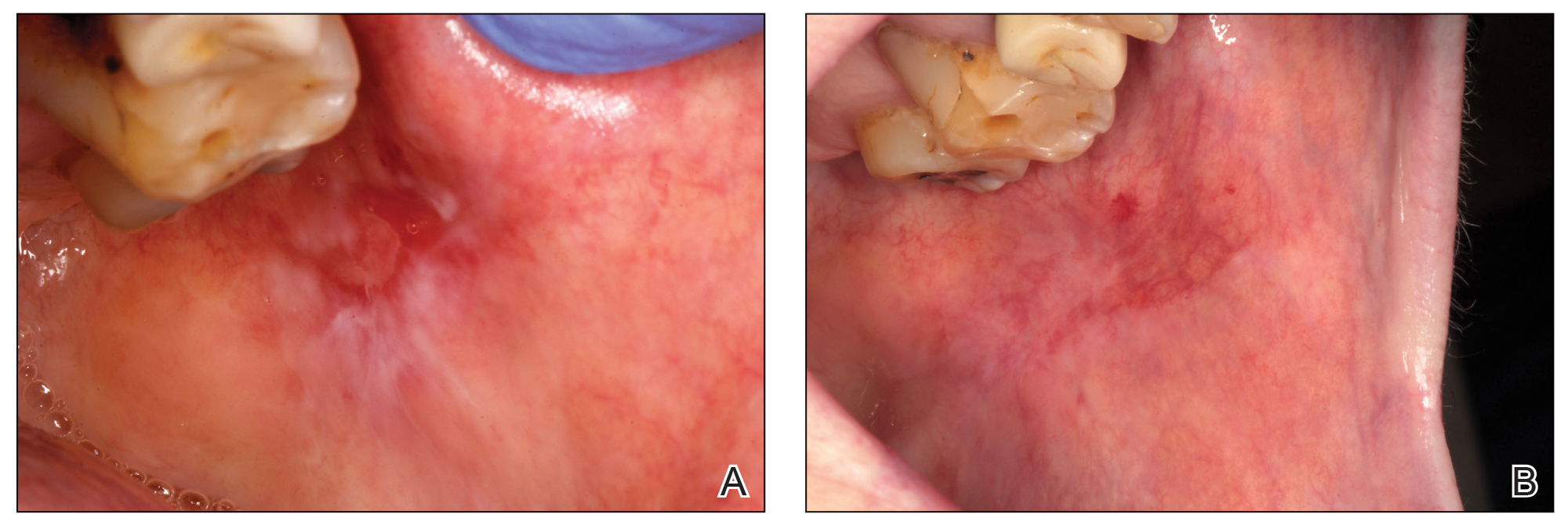

Healing of OLP Lesions—The number of treatment sessions to achieve complete healing varied among the patients (Figures 1 and 2). Ten patients (66.7%) required a single session, 2 patients (13.3%) required 2 sessions, and 3 patients (20%) required 3 sessions. The mean time (SD) without lesions for the patients who required a single session was 10.9 (5.2) months (range, 6–24 months).

Pain Assessment—The mean (SD) score obtained on the VAS before treatment with PRGF was 8.27 (1.16); this score dropped to 1.27 (1.53) after the first treatment session and was a statistically significant difference (P=.006).

For those patients requiring more than 1 session, the mean (SD) pain scores decreased by 0.75 (0.97) points and 0 points after the first and second sessions of treatment, respectively. The mean (SD) amount of PRGF infiltrated in each patient in the first session was 2.60 (0.63) mL. In the second session, the mean (SD) amount was 1.2 (0.33) mL; these differences were statistically significant (P=.008). In the last session, the mean (SD) amount was 1.1 (0.22) mL.

Follow-up and Adverse Effects—The mean (SD) follow-up time was 47.16 (15.78) months. The patients were free of symptoms, and there were no adverse effects derived from the treatment during follow-up.

Comment

The primary goal of OLP treatment is to stop the outbreaks.1,9,13 The lack of potency of corticosteroids in some patients with OLP could be due in part to the inadequate selection of the vehicle (ointment/oral rinse) for the extension and characteristics of the lesion or because of an inappropriate prescription dose, time, and/or frequency, as described by González-Moles.17 However, even when using an appropriate protocol, some lesions are resistant to topical treatment and require other therapeutic modalities.1,9,13 Previously proposed topical treatments include different immunosuppressants, such as the mammalian target of rapamycin, tacrolimus ointment 0.1%, pimecrolimus cream 1%, or cyclosporine A (50–100 mg/mL) formulations.18 Nevertheless, these drugs seem to have a greater number of side effects than topical steroids, and tacrolimus has been associated with cases of oral malignancy after continuing treatment.15

Severe and/or recalcitrant lesions and extraoral involvement have been successfully treated with systemic prednisone (40–80 mg/d).1,9,13 Nevertheless, systemic corticosteroid toxicity requires that these treatments should be used only when necessary at the lowest possible dose and for the shortest possible duration.19 Other nonpharmacologic options for treatment are photodynamic, UV, and low-level laser therapy.20,21 They have been accepted as supplementary modalities in different inflammatory skin conditions but present important technical requirements. Their effectiveness in corticosteroid-resistant cases have not been definitively assessed. Interestingly, promising results recently have been reported by Bennardo et al22 when comparing the efficacy of autologous platelet concentrates with triamcinolone injection.

In our study, the use of PRGF stopped the lesions’ evolution since the first treatment session, reducing them by 6.5-fold. The positive effects observed may have been promoted by the activity of different proteins present in PRGF (eg, platelet-derived growth factor, vascular endothelial growth factor, transforming growth factor, epidermal growth factor, fibroblast growth factor, fibronectin). These molecules contribute to collagen synthesis; angiogenesis; endothelial cell migration and proliferation; or keratinocyte cell migration, proliferation, differentiation, growth, and migration—phenomena that are essential for healing and re-epithelialization.23-25

Different studies also have supported an anti-inflammatory effect of PRGF mediated by an inhibition of the transcription of nuclear factor–κB and the expression of cyclooxygenase-2 and chemokine receptor type 4 produced by its high content of hepatocyte growth factor or the reduction of inflammatory marker expression, such as intercellular adhesion molecule 1. The development of an efficient 3-dimensional fibrin scaffold formation that occurs after PRGF administration also could facilitate healing, helping some cell populations to guide their position and function.23-25

Limitations of our study include the small number of patients and the absence of a control group. The higher number of female patients in the study did not seem to affect the results, as differences related to gender have not been reported when treating patients with OLP with autologous platelet concentrates or other modalities of treatment.

Conclusion

Results from our study indicate that the use of PRGF could be a new treatment option for OLP cases refractory to conventional therapy. No complications were observed during the treatment procedure or during the complete follow-up period. Nonetheless, new prospective studies with a greater number of patients and longer follow-up periods are needed to confirm these preliminary results.

- Al-Hashimi I, Schifter M, Lockhart PB, et al. Oral lichen planus and oral lichenoid lesions: diagnostic and therapeutic considerations. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2007;103:1-12.

- Kurago ZB. Etiology and pathogenesis of oral lichen planus: an overview. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol. 2016;122:72-80.

- McCartan BE, Healy CM. The reported prevalence of oral lichen planus: a review and critique. J Oral Pathol Med. 2008;37:447-453.

- González-Moles MÁ, Warnakulasuriya S, González-Ruiz I, et al. Worldwide prevalence of oral lichen planus: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Oral Dis. 2021;27:813-828.

- Nosratzehi T. Oral lichen planus: an overview of potential risk factors, biomarkers and treatments. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2018;19:1161-1167.

- Mehrbani SP, Motahari P, Azar FP, et al. Role of interleukin-4 in pathogenesis of oral lichen planus: a systematic review. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal. 2020;25:E410-E415.

- Edwards PC, Kelsch R. Oral lichen planus: clinical presentation and management. J Can Dent Assoc. 2002;68:494-499.

- Gorouhi F, Davari P, Fazel N. Cutaneous and mucosal lichen planus: a comprehensive review of clinical subtypes, risk factors, diagnosis, and prognosis. ScientificWorldJournal. 2014;2014:742826.

- Babu A, Chellaswamy S, Muthukumar S, et al. Bullous lichen planus: case report and review. J Pharm Bioallied Sci. 2019;11(suppl 2):S499-S506.

- Thongprasom K, Carrozzo M, Furness S, et al. Interventions for treating oral lichen planus. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;7:CD001168.

- López-Jornet P, Martínez-Beneyto Y, Nicolás AV, et al. Professional attitudes toward oral lichen planus: need for national and international guidelines. J Eval Clin Pract. 2009;15:541-542.

- Yang H, Wu Y, Jiang L, et al. Possible alternative therapies for oral lichen planus cases refractory to steroid therapies. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol. 2016;121:496-509.

- Ribero S, Borradori L. Re: risk of malignancy and systemic absorption after application of topical tacrolimus in oral lichen planus. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2017;31:E85-E86.

- Piñas L, Alkhraisat MH, Fernández RS, et al. Biological therapy of refractory ulcerative oral lichen planus with plasma rich in growth factors. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2017;18:429-433.

- Anitua E, Zalduendo MM, Prado R, et al. Morphogen and proinflammatory cytokine release kinetics from PRGF-Endoret fibrin scaffolds: evaluation of the effect of leukocyte inclusion. J Biomed Mater Res A. 2015;103:1011-1020.

- Anitua E, Prado R, Sánchez M, et al. Platelet-rich plasma: preparation and formulation. Oper Tech Orthop. 2012;22:25-32.

- González-Moles MA. The use of topical corticoids in oral pathology. Med Oral Pathol Oral Cir Bucal. 2010;15:E827-E831.

- Siponen M, Huuskonen L, Kallio-Pulkkinen S, et al. Topical tacrolimus, triamcinolone acetonide, and placebo in oral lichen planus: a pilot randomized controlled trial. Oral Dis. 2017;23:660-668.

- Adami G, Saag KG. Glucocorticoid-induced osteoporosis update. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2019;31:388-393.

- Lavaee F, Shadmanpour M. Comparison of the effect of photodynamic therapy and topical corticosteroid on oral lichen planus lesions. Oral Dis. 2019;25:1954-1963.

- Derikvand N, Ghasemi SS, Moharami M, et al. Management of oral lichen planus by 980 nm diode laser. J Lasers Med Sci. 2017;8:150-154.

- Bennardo F, Liborio F, Barone S, et al. Efficacy of platelet-rich fibrin compared with triamcinolone acetonide as injective therapy in the treatment of symptomatic oral lichen planus: a pilot study. Clin Oral Investig. 2021;25:3747-3755.

- Anitua E, Andia I, Ardanza B, et al. Autologous platelets as a source of proteins for healing and tissue regeneration. Thromb Haemost. 2004;91:4-15.

- Barrientos S, Brem H, Stojadinovic O, et al. Clinical application of growth factors and cytokines in wound healing. Wound Repair Regen. 2014;22:569-578.

- Anitua E. Plasma rich in growth factors: preliminary results of use in the preparation of future sites for implants. Int J Oral Maxillofac Implants. 1999;14:529-535.

Lichen planus is a chronic inflammatory mucocutaneous disease that usually affects the skin and/or the genital and oral mucosae.1,2 This disease classically presents with clinical relapses or outbreaks that alternate with periods of remission or latency. Oral lichen planus (OLP) can present with or without extraoral manifestation. It sometimes is difficult to differentiate OLP from oral lichenoid reactions, which can be related to dental materials, some drugs, and systemic conditions or can be idiopathic.1,2

Oral lichen planus is one of the most common noninfectious diseases of the oral cavity, with a reported prevalence of 1% worldwide and marked geographical differences. In Europe, the prevalence of OLP ranges from 1% to 2%.3,4 It is more frequent in women (1.5:1 to 2:1) and usually appears in the fourth and fifth decades of life.1-4

The causes of OLP have not been entirely elucidated, but it is broadly accepted that there is a deregulation on different T lymphocytes that in turn causes effects on CD8 lymphocytes in response to an external noxa. This unknown “trigger” or starting factor also produces an impact on basal keratinocytes. Therefore, the pathogenesis of lichen planus is influenced by a series of cellular events mediated by different cytokines.2,5,6 Among these, tumor necrosis factor α and IL-1 are known to have important roles in the disease. More recently, other cytokines, such as IL-4, secreted by type 2 helper T cells, also have been related to the development and progression of the oral lesions.5,6 In addition to the factors that generate the onset of the disease, there are others that may precipitate clinical outbreaks. Different factors have been related to the progression of the disease, influencing the initiation, perpetuation, and/or worsening of OLP lesions.1,2 Exactly how these factors affect disease progression is another challenging question. The list of possible or potential factors related to disease progression is long; nonetheless, in the vast majority, a clear explanation at a molecular level has not been clearly demonstrated.2,5

Conventionally, 6 clinical presentations of OLP lesions divided into 2 main groups have been described in the oral cavity: white forms (reticular, papular, and plaquelike) and red forms (erythematous, atrophic-erosive, and bullous).1,7-9

Oral lichen planus mainly is treated with topically or systemically administered steroids based on the presence of symptoms such as pain and inability to perform daily activities (eg, eating, talking).5,10 The treatment of choice often is based on the professional’s experience, as there are no broadly accepted national or international clinical practice guidelines on steroid type, administration route, dose, vehicle for administration, or maintenance.11 Despite this lack of unified criteria, different topical and systemic steroid administration protocols allow a reduction in the symptoms or even the disappearance of the red lesions to be achieved in many cases. Unfortunately, there are many patients with lesions refractory to standard treatments for OLP.12 Several alternatives for these patients have been described in the literature, though on many occasions these alternatives present substantial side effects for the patient.13 The search for an effective treatment without side effects is still challenging. One of the treatments tested under this premise has been the application of plasma rich in growth factors (PRGF) by means of infiltration or topical application, in both cases obtaining good results without side effects.14

We sought to analyze the information from a case series of patients treated at the Eduardo Anitua Clinic (Vitoria-Gasteiz, Spain) and describe the results and follow-up of patients with erosive OLP refractory to standard therapy who have been successfully treated by local infiltration of PRGF as the only treatment.

Material and Methods

Patients—We included data from the database of the clinical center with de-identified information of patients with erosive OLP diagnosed clinically and histopathologically who did not respond to conventional treatment (ie, topical and/or systemic corticosteroids [depending on the case]) as well as patients who presented with extensive erosive OLP with systemic involvement and whose systemic treatment was not effective in resolving oral manifestations.

Therapies Administered and Evaluations—Lesions refractory to conventional corticosteroid protocols had been previously treated for 30 days with 0.5% triamcinolone acetonide mouth rinse followed by a cycle of 1% triamcinolone acetonide mouth rinse. Subsequently, a cycle of oral corticosteroids (prednisone for 30 days: 1 mg/kg/d in a single morning dose with staged reduction after the first week) had been administered. One dayafter the corticosteroid treatment was suspended, the patients were treated by PRGF-Endoret (BTI Biotechnology Institute) infiltration following the protocol described by Anitua et al.15,16

Before starting the infiltrations with PRGF, the patient had been asked to rate the pain level on a visual analog scale (VAS) of 1 to 10, with 10 being the most intense imaginable pain. Pain score was subsequently rated and registered during every visit. An initial photograph of the lesion also was obtained to establish a starting point for further comparisons of clinical evolution of the lesions.

Prior to each infiltration, the plasma was separated into 2 fractions. The second fraction was the one that corresponded to the highest number of platelets and included the 2 mL of plasma just above the white series (or buffy coat). This fraction of plasma was the one used to infiltrate the lesions.

Plasma rich in growth factors was activated just before infiltration. The activation was done by adding 10% calcium chloride. Once activated, it was infiltrated into the active lesion using a 31-G × 1/6-in hypodermic needle and a 2-mL Luer-lock syringe. Infiltrations were performed without anesthesia. Four punctures were made for each ulcerative lesion, dividing the lesion into 4 points: upper, lower, right, and left. Plasma rich in growth factors was infiltrated until a slight blanching was observed in the surrounding tissue. At that moment, the infiltration was stopped and was carried out in the next infiltration site.

One treatment session was performed per week, with follow-up 1 week after treatment. In the control visit, the state of the lesions was re-evaluated, and it was decided whether new infiltrations were needed. The treatment was finished when complete epithelialization of the lesion was visualized or the associated symptoms disappeared. At each visit, photographs were taken, and the patient assessed the severity of pain on the VAS.

Statistical Analysis—A Shapiro-Wilk test was carried out with the obtained data to check the normal distribution of the sample. The evolution of pain during the study was compared by paired t test. The qualitative variables were described by means of a frequency analysis. Quantitative variables were described by the mean and the SD. The data were analyzed with SPSS V15.0 for Windows (SPSS Inc). P<.05 showed statistical significance.

Results

A total of 15 patients were included in the study, all with atrophic-erosive lichen planus. Two patients were male, and 13 were female. The mean age (SD) of the patients included in the study was 55.27 (14.19) years. The mean number of outbreaks per year (SD) was 3.2 (1.7), with a range of 1 to 8 outbreaks.

Healing of OLP Lesions—The number of treatment sessions to achieve complete healing varied among the patients (Figures 1 and 2). Ten patients (66.7%) required a single session, 2 patients (13.3%) required 2 sessions, and 3 patients (20%) required 3 sessions. The mean time (SD) without lesions for the patients who required a single session was 10.9 (5.2) months (range, 6–24 months).

Pain Assessment—The mean (SD) score obtained on the VAS before treatment with PRGF was 8.27 (1.16); this score dropped to 1.27 (1.53) after the first treatment session and was a statistically significant difference (P=.006).

For those patients requiring more than 1 session, the mean (SD) pain scores decreased by 0.75 (0.97) points and 0 points after the first and second sessions of treatment, respectively. The mean (SD) amount of PRGF infiltrated in each patient in the first session was 2.60 (0.63) mL. In the second session, the mean (SD) amount was 1.2 (0.33) mL; these differences were statistically significant (P=.008). In the last session, the mean (SD) amount was 1.1 (0.22) mL.

Follow-up and Adverse Effects—The mean (SD) follow-up time was 47.16 (15.78) months. The patients were free of symptoms, and there were no adverse effects derived from the treatment during follow-up.

Comment

The primary goal of OLP treatment is to stop the outbreaks.1,9,13 The lack of potency of corticosteroids in some patients with OLP could be due in part to the inadequate selection of the vehicle (ointment/oral rinse) for the extension and characteristics of the lesion or because of an inappropriate prescription dose, time, and/or frequency, as described by González-Moles.17 However, even when using an appropriate protocol, some lesions are resistant to topical treatment and require other therapeutic modalities.1,9,13 Previously proposed topical treatments include different immunosuppressants, such as the mammalian target of rapamycin, tacrolimus ointment 0.1%, pimecrolimus cream 1%, or cyclosporine A (50–100 mg/mL) formulations.18 Nevertheless, these drugs seem to have a greater number of side effects than topical steroids, and tacrolimus has been associated with cases of oral malignancy after continuing treatment.15

Severe and/or recalcitrant lesions and extraoral involvement have been successfully treated with systemic prednisone (40–80 mg/d).1,9,13 Nevertheless, systemic corticosteroid toxicity requires that these treatments should be used only when necessary at the lowest possible dose and for the shortest possible duration.19 Other nonpharmacologic options for treatment are photodynamic, UV, and low-level laser therapy.20,21 They have been accepted as supplementary modalities in different inflammatory skin conditions but present important technical requirements. Their effectiveness in corticosteroid-resistant cases have not been definitively assessed. Interestingly, promising results recently have been reported by Bennardo et al22 when comparing the efficacy of autologous platelet concentrates with triamcinolone injection.

In our study, the use of PRGF stopped the lesions’ evolution since the first treatment session, reducing them by 6.5-fold. The positive effects observed may have been promoted by the activity of different proteins present in PRGF (eg, platelet-derived growth factor, vascular endothelial growth factor, transforming growth factor, epidermal growth factor, fibroblast growth factor, fibronectin). These molecules contribute to collagen synthesis; angiogenesis; endothelial cell migration and proliferation; or keratinocyte cell migration, proliferation, differentiation, growth, and migration—phenomena that are essential for healing and re-epithelialization.23-25

Different studies also have supported an anti-inflammatory effect of PRGF mediated by an inhibition of the transcription of nuclear factor–κB and the expression of cyclooxygenase-2 and chemokine receptor type 4 produced by its high content of hepatocyte growth factor or the reduction of inflammatory marker expression, such as intercellular adhesion molecule 1. The development of an efficient 3-dimensional fibrin scaffold formation that occurs after PRGF administration also could facilitate healing, helping some cell populations to guide their position and function.23-25

Limitations of our study include the small number of patients and the absence of a control group. The higher number of female patients in the study did not seem to affect the results, as differences related to gender have not been reported when treating patients with OLP with autologous platelet concentrates or other modalities of treatment.

Conclusion

Results from our study indicate that the use of PRGF could be a new treatment option for OLP cases refractory to conventional therapy. No complications were observed during the treatment procedure or during the complete follow-up period. Nonetheless, new prospective studies with a greater number of patients and longer follow-up periods are needed to confirm these preliminary results.

Lichen planus is a chronic inflammatory mucocutaneous disease that usually affects the skin and/or the genital and oral mucosae.1,2 This disease classically presents with clinical relapses or outbreaks that alternate with periods of remission or latency. Oral lichen planus (OLP) can present with or without extraoral manifestation. It sometimes is difficult to differentiate OLP from oral lichenoid reactions, which can be related to dental materials, some drugs, and systemic conditions or can be idiopathic.1,2

Oral lichen planus is one of the most common noninfectious diseases of the oral cavity, with a reported prevalence of 1% worldwide and marked geographical differences. In Europe, the prevalence of OLP ranges from 1% to 2%.3,4 It is more frequent in women (1.5:1 to 2:1) and usually appears in the fourth and fifth decades of life.1-4

The causes of OLP have not been entirely elucidated, but it is broadly accepted that there is a deregulation on different T lymphocytes that in turn causes effects on CD8 lymphocytes in response to an external noxa. This unknown “trigger” or starting factor also produces an impact on basal keratinocytes. Therefore, the pathogenesis of lichen planus is influenced by a series of cellular events mediated by different cytokines.2,5,6 Among these, tumor necrosis factor α and IL-1 are known to have important roles in the disease. More recently, other cytokines, such as IL-4, secreted by type 2 helper T cells, also have been related to the development and progression of the oral lesions.5,6 In addition to the factors that generate the onset of the disease, there are others that may precipitate clinical outbreaks. Different factors have been related to the progression of the disease, influencing the initiation, perpetuation, and/or worsening of OLP lesions.1,2 Exactly how these factors affect disease progression is another challenging question. The list of possible or potential factors related to disease progression is long; nonetheless, in the vast majority, a clear explanation at a molecular level has not been clearly demonstrated.2,5

Conventionally, 6 clinical presentations of OLP lesions divided into 2 main groups have been described in the oral cavity: white forms (reticular, papular, and plaquelike) and red forms (erythematous, atrophic-erosive, and bullous).1,7-9

Oral lichen planus mainly is treated with topically or systemically administered steroids based on the presence of symptoms such as pain and inability to perform daily activities (eg, eating, talking).5,10 The treatment of choice often is based on the professional’s experience, as there are no broadly accepted national or international clinical practice guidelines on steroid type, administration route, dose, vehicle for administration, or maintenance.11 Despite this lack of unified criteria, different topical and systemic steroid administration protocols allow a reduction in the symptoms or even the disappearance of the red lesions to be achieved in many cases. Unfortunately, there are many patients with lesions refractory to standard treatments for OLP.12 Several alternatives for these patients have been described in the literature, though on many occasions these alternatives present substantial side effects for the patient.13 The search for an effective treatment without side effects is still challenging. One of the treatments tested under this premise has been the application of plasma rich in growth factors (PRGF) by means of infiltration or topical application, in both cases obtaining good results without side effects.14

We sought to analyze the information from a case series of patients treated at the Eduardo Anitua Clinic (Vitoria-Gasteiz, Spain) and describe the results and follow-up of patients with erosive OLP refractory to standard therapy who have been successfully treated by local infiltration of PRGF as the only treatment.

Material and Methods

Patients—We included data from the database of the clinical center with de-identified information of patients with erosive OLP diagnosed clinically and histopathologically who did not respond to conventional treatment (ie, topical and/or systemic corticosteroids [depending on the case]) as well as patients who presented with extensive erosive OLP with systemic involvement and whose systemic treatment was not effective in resolving oral manifestations.

Therapies Administered and Evaluations—Lesions refractory to conventional corticosteroid protocols had been previously treated for 30 days with 0.5% triamcinolone acetonide mouth rinse followed by a cycle of 1% triamcinolone acetonide mouth rinse. Subsequently, a cycle of oral corticosteroids (prednisone for 30 days: 1 mg/kg/d in a single morning dose with staged reduction after the first week) had been administered. One dayafter the corticosteroid treatment was suspended, the patients were treated by PRGF-Endoret (BTI Biotechnology Institute) infiltration following the protocol described by Anitua et al.15,16

Before starting the infiltrations with PRGF, the patient had been asked to rate the pain level on a visual analog scale (VAS) of 1 to 10, with 10 being the most intense imaginable pain. Pain score was subsequently rated and registered during every visit. An initial photograph of the lesion also was obtained to establish a starting point for further comparisons of clinical evolution of the lesions.

Prior to each infiltration, the plasma was separated into 2 fractions. The second fraction was the one that corresponded to the highest number of platelets and included the 2 mL of plasma just above the white series (or buffy coat). This fraction of plasma was the one used to infiltrate the lesions.

Plasma rich in growth factors was activated just before infiltration. The activation was done by adding 10% calcium chloride. Once activated, it was infiltrated into the active lesion using a 31-G × 1/6-in hypodermic needle and a 2-mL Luer-lock syringe. Infiltrations were performed without anesthesia. Four punctures were made for each ulcerative lesion, dividing the lesion into 4 points: upper, lower, right, and left. Plasma rich in growth factors was infiltrated until a slight blanching was observed in the surrounding tissue. At that moment, the infiltration was stopped and was carried out in the next infiltration site.

One treatment session was performed per week, with follow-up 1 week after treatment. In the control visit, the state of the lesions was re-evaluated, and it was decided whether new infiltrations were needed. The treatment was finished when complete epithelialization of the lesion was visualized or the associated symptoms disappeared. At each visit, photographs were taken, and the patient assessed the severity of pain on the VAS.

Statistical Analysis—A Shapiro-Wilk test was carried out with the obtained data to check the normal distribution of the sample. The evolution of pain during the study was compared by paired t test. The qualitative variables were described by means of a frequency analysis. Quantitative variables were described by the mean and the SD. The data were analyzed with SPSS V15.0 for Windows (SPSS Inc). P<.05 showed statistical significance.

Results

A total of 15 patients were included in the study, all with atrophic-erosive lichen planus. Two patients were male, and 13 were female. The mean age (SD) of the patients included in the study was 55.27 (14.19) years. The mean number of outbreaks per year (SD) was 3.2 (1.7), with a range of 1 to 8 outbreaks.

Healing of OLP Lesions—The number of treatment sessions to achieve complete healing varied among the patients (Figures 1 and 2). Ten patients (66.7%) required a single session, 2 patients (13.3%) required 2 sessions, and 3 patients (20%) required 3 sessions. The mean time (SD) without lesions for the patients who required a single session was 10.9 (5.2) months (range, 6–24 months).

Pain Assessment—The mean (SD) score obtained on the VAS before treatment with PRGF was 8.27 (1.16); this score dropped to 1.27 (1.53) after the first treatment session and was a statistically significant difference (P=.006).

For those patients requiring more than 1 session, the mean (SD) pain scores decreased by 0.75 (0.97) points and 0 points after the first and second sessions of treatment, respectively. The mean (SD) amount of PRGF infiltrated in each patient in the first session was 2.60 (0.63) mL. In the second session, the mean (SD) amount was 1.2 (0.33) mL; these differences were statistically significant (P=.008). In the last session, the mean (SD) amount was 1.1 (0.22) mL.

Follow-up and Adverse Effects—The mean (SD) follow-up time was 47.16 (15.78) months. The patients were free of symptoms, and there were no adverse effects derived from the treatment during follow-up.

Comment

The primary goal of OLP treatment is to stop the outbreaks.1,9,13 The lack of potency of corticosteroids in some patients with OLP could be due in part to the inadequate selection of the vehicle (ointment/oral rinse) for the extension and characteristics of the lesion or because of an inappropriate prescription dose, time, and/or frequency, as described by González-Moles.17 However, even when using an appropriate protocol, some lesions are resistant to topical treatment and require other therapeutic modalities.1,9,13 Previously proposed topical treatments include different immunosuppressants, such as the mammalian target of rapamycin, tacrolimus ointment 0.1%, pimecrolimus cream 1%, or cyclosporine A (50–100 mg/mL) formulations.18 Nevertheless, these drugs seem to have a greater number of side effects than topical steroids, and tacrolimus has been associated with cases of oral malignancy after continuing treatment.15

Severe and/or recalcitrant lesions and extraoral involvement have been successfully treated with systemic prednisone (40–80 mg/d).1,9,13 Nevertheless, systemic corticosteroid toxicity requires that these treatments should be used only when necessary at the lowest possible dose and for the shortest possible duration.19 Other nonpharmacologic options for treatment are photodynamic, UV, and low-level laser therapy.20,21 They have been accepted as supplementary modalities in different inflammatory skin conditions but present important technical requirements. Their effectiveness in corticosteroid-resistant cases have not been definitively assessed. Interestingly, promising results recently have been reported by Bennardo et al22 when comparing the efficacy of autologous platelet concentrates with triamcinolone injection.

In our study, the use of PRGF stopped the lesions’ evolution since the first treatment session, reducing them by 6.5-fold. The positive effects observed may have been promoted by the activity of different proteins present in PRGF (eg, platelet-derived growth factor, vascular endothelial growth factor, transforming growth factor, epidermal growth factor, fibroblast growth factor, fibronectin). These molecules contribute to collagen synthesis; angiogenesis; endothelial cell migration and proliferation; or keratinocyte cell migration, proliferation, differentiation, growth, and migration—phenomena that are essential for healing and re-epithelialization.23-25

Different studies also have supported an anti-inflammatory effect of PRGF mediated by an inhibition of the transcription of nuclear factor–κB and the expression of cyclooxygenase-2 and chemokine receptor type 4 produced by its high content of hepatocyte growth factor or the reduction of inflammatory marker expression, such as intercellular adhesion molecule 1. The development of an efficient 3-dimensional fibrin scaffold formation that occurs after PRGF administration also could facilitate healing, helping some cell populations to guide their position and function.23-25

Limitations of our study include the small number of patients and the absence of a control group. The higher number of female patients in the study did not seem to affect the results, as differences related to gender have not been reported when treating patients with OLP with autologous platelet concentrates or other modalities of treatment.

Conclusion

Results from our study indicate that the use of PRGF could be a new treatment option for OLP cases refractory to conventional therapy. No complications were observed during the treatment procedure or during the complete follow-up period. Nonetheless, new prospective studies with a greater number of patients and longer follow-up periods are needed to confirm these preliminary results.

- Al-Hashimi I, Schifter M, Lockhart PB, et al. Oral lichen planus and oral lichenoid lesions: diagnostic and therapeutic considerations. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2007;103:1-12.

- Kurago ZB. Etiology and pathogenesis of oral lichen planus: an overview. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol. 2016;122:72-80.

- McCartan BE, Healy CM. The reported prevalence of oral lichen planus: a review and critique. J Oral Pathol Med. 2008;37:447-453.

- González-Moles MÁ, Warnakulasuriya S, González-Ruiz I, et al. Worldwide prevalence of oral lichen planus: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Oral Dis. 2021;27:813-828.

- Nosratzehi T. Oral lichen planus: an overview of potential risk factors, biomarkers and treatments. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2018;19:1161-1167.

- Mehrbani SP, Motahari P, Azar FP, et al. Role of interleukin-4 in pathogenesis of oral lichen planus: a systematic review. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal. 2020;25:E410-E415.

- Edwards PC, Kelsch R. Oral lichen planus: clinical presentation and management. J Can Dent Assoc. 2002;68:494-499.

- Gorouhi F, Davari P, Fazel N. Cutaneous and mucosal lichen planus: a comprehensive review of clinical subtypes, risk factors, diagnosis, and prognosis. ScientificWorldJournal. 2014;2014:742826.

- Babu A, Chellaswamy S, Muthukumar S, et al. Bullous lichen planus: case report and review. J Pharm Bioallied Sci. 2019;11(suppl 2):S499-S506.

- Thongprasom K, Carrozzo M, Furness S, et al. Interventions for treating oral lichen planus. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;7:CD001168.

- López-Jornet P, Martínez-Beneyto Y, Nicolás AV, et al. Professional attitudes toward oral lichen planus: need for national and international guidelines. J Eval Clin Pract. 2009;15:541-542.

- Yang H, Wu Y, Jiang L, et al. Possible alternative therapies for oral lichen planus cases refractory to steroid therapies. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol. 2016;121:496-509.

- Ribero S, Borradori L. Re: risk of malignancy and systemic absorption after application of topical tacrolimus in oral lichen planus. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2017;31:E85-E86.

- Piñas L, Alkhraisat MH, Fernández RS, et al. Biological therapy of refractory ulcerative oral lichen planus with plasma rich in growth factors. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2017;18:429-433.

- Anitua E, Zalduendo MM, Prado R, et al. Morphogen and proinflammatory cytokine release kinetics from PRGF-Endoret fibrin scaffolds: evaluation of the effect of leukocyte inclusion. J Biomed Mater Res A. 2015;103:1011-1020.

- Anitua E, Prado R, Sánchez M, et al. Platelet-rich plasma: preparation and formulation. Oper Tech Orthop. 2012;22:25-32.

- González-Moles MA. The use of topical corticoids in oral pathology. Med Oral Pathol Oral Cir Bucal. 2010;15:E827-E831.

- Siponen M, Huuskonen L, Kallio-Pulkkinen S, et al. Topical tacrolimus, triamcinolone acetonide, and placebo in oral lichen planus: a pilot randomized controlled trial. Oral Dis. 2017;23:660-668.

- Adami G, Saag KG. Glucocorticoid-induced osteoporosis update. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2019;31:388-393.

- Lavaee F, Shadmanpour M. Comparison of the effect of photodynamic therapy and topical corticosteroid on oral lichen planus lesions. Oral Dis. 2019;25:1954-1963.

- Derikvand N, Ghasemi SS, Moharami M, et al. Management of oral lichen planus by 980 nm diode laser. J Lasers Med Sci. 2017;8:150-154.

- Bennardo F, Liborio F, Barone S, et al. Efficacy of platelet-rich fibrin compared with triamcinolone acetonide as injective therapy in the treatment of symptomatic oral lichen planus: a pilot study. Clin Oral Investig. 2021;25:3747-3755.

- Anitua E, Andia I, Ardanza B, et al. Autologous platelets as a source of proteins for healing and tissue regeneration. Thromb Haemost. 2004;91:4-15.

- Barrientos S, Brem H, Stojadinovic O, et al. Clinical application of growth factors and cytokines in wound healing. Wound Repair Regen. 2014;22:569-578.

- Anitua E. Plasma rich in growth factors: preliminary results of use in the preparation of future sites for implants. Int J Oral Maxillofac Implants. 1999;14:529-535.

- Al-Hashimi I, Schifter M, Lockhart PB, et al. Oral lichen planus and oral lichenoid lesions: diagnostic and therapeutic considerations. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2007;103:1-12.

- Kurago ZB. Etiology and pathogenesis of oral lichen planus: an overview. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol. 2016;122:72-80.

- McCartan BE, Healy CM. The reported prevalence of oral lichen planus: a review and critique. J Oral Pathol Med. 2008;37:447-453.

- González-Moles MÁ, Warnakulasuriya S, González-Ruiz I, et al. Worldwide prevalence of oral lichen planus: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Oral Dis. 2021;27:813-828.

- Nosratzehi T. Oral lichen planus: an overview of potential risk factors, biomarkers and treatments. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2018;19:1161-1167.

- Mehrbani SP, Motahari P, Azar FP, et al. Role of interleukin-4 in pathogenesis of oral lichen planus: a systematic review. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal. 2020;25:E410-E415.

- Edwards PC, Kelsch R. Oral lichen planus: clinical presentation and management. J Can Dent Assoc. 2002;68:494-499.

- Gorouhi F, Davari P, Fazel N. Cutaneous and mucosal lichen planus: a comprehensive review of clinical subtypes, risk factors, diagnosis, and prognosis. ScientificWorldJournal. 2014;2014:742826.

- Babu A, Chellaswamy S, Muthukumar S, et al. Bullous lichen planus: case report and review. J Pharm Bioallied Sci. 2019;11(suppl 2):S499-S506.

- Thongprasom K, Carrozzo M, Furness S, et al. Interventions for treating oral lichen planus. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;7:CD001168.

- López-Jornet P, Martínez-Beneyto Y, Nicolás AV, et al. Professional attitudes toward oral lichen planus: need for national and international guidelines. J Eval Clin Pract. 2009;15:541-542.

- Yang H, Wu Y, Jiang L, et al. Possible alternative therapies for oral lichen planus cases refractory to steroid therapies. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol. 2016;121:496-509.

- Ribero S, Borradori L. Re: risk of malignancy and systemic absorption after application of topical tacrolimus in oral lichen planus. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2017;31:E85-E86.

- Piñas L, Alkhraisat MH, Fernández RS, et al. Biological therapy of refractory ulcerative oral lichen planus with plasma rich in growth factors. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2017;18:429-433.

- Anitua E, Zalduendo MM, Prado R, et al. Morphogen and proinflammatory cytokine release kinetics from PRGF-Endoret fibrin scaffolds: evaluation of the effect of leukocyte inclusion. J Biomed Mater Res A. 2015;103:1011-1020.

- Anitua E, Prado R, Sánchez M, et al. Platelet-rich plasma: preparation and formulation. Oper Tech Orthop. 2012;22:25-32.

- González-Moles MA. The use of topical corticoids in oral pathology. Med Oral Pathol Oral Cir Bucal. 2010;15:E827-E831.

- Siponen M, Huuskonen L, Kallio-Pulkkinen S, et al. Topical tacrolimus, triamcinolone acetonide, and placebo in oral lichen planus: a pilot randomized controlled trial. Oral Dis. 2017;23:660-668.

- Adami G, Saag KG. Glucocorticoid-induced osteoporosis update. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2019;31:388-393.

- Lavaee F, Shadmanpour M. Comparison of the effect of photodynamic therapy and topical corticosteroid on oral lichen planus lesions. Oral Dis. 2019;25:1954-1963.

- Derikvand N, Ghasemi SS, Moharami M, et al. Management of oral lichen planus by 980 nm diode laser. J Lasers Med Sci. 2017;8:150-154.

- Bennardo F, Liborio F, Barone S, et al. Efficacy of platelet-rich fibrin compared with triamcinolone acetonide as injective therapy in the treatment of symptomatic oral lichen planus: a pilot study. Clin Oral Investig. 2021;25:3747-3755.

- Anitua E, Andia I, Ardanza B, et al. Autologous platelets as a source of proteins for healing and tissue regeneration. Thromb Haemost. 2004;91:4-15.

- Barrientos S, Brem H, Stojadinovic O, et al. Clinical application of growth factors and cytokines in wound healing. Wound Repair Regen. 2014;22:569-578.

- Anitua E. Plasma rich in growth factors: preliminary results of use in the preparation of future sites for implants. Int J Oral Maxillofac Implants. 1999;14:529-535.

Practice Points

- Treating erosive oral lichen planus lesions refractory to conventional steroid treatments can be challenging for clinicians.

- Complete re-epithelialization and total pain relief could be observed after 1 to 3 weekly perilesional infiltrations with plasma rich in growth factors.

- No relapse of the lesions in the same area or other complications could be observed during the follow-up time.

Interstitial Granulomatous Dermatitis as an Adverse Reaction to Vedolizumab

The number of monoclonal antibodies developed for therapeutic use has rapidly expanded over the last decade due to their generally favorable adverse effect (AE) profiles and efficacy.1 Tumor necrosis factor α inhibitors and general integrin antagonists are well-known examples of such monoclonal antibodies. Common conditions utilizing immunotherapy include inflammatory bowel diseases (IBDs), such as Crohn disease and ulcerative colitis (UC).2

The monoclonal antibody vedolizumab, approved in 2014 for moderate to severe UC and Crohn disease, selectively antagonizes α4β7 integrin to target a specific population of gastrointestinal T lymphocytes, preventing their mobilization to areas of inflammation.3 Adverse effects in patients treated with vedolizumab occur at a rate comparable to placebo and largely are considered nonserious4,5; the most commonly reported AE is disease exacerbation (13%–17% of patients).5,6 Published reports of cutaneous AEs at administration of vedolizumab include urticaria during infusion, appearance of cutaneous manifestations characteristic of IBD, psoriasis, Henoch-Schönlein purpura, and Sweet syndrome.7-10

We present the case of a 61-year-old woman with UC who developed reactive granulomatous dermatitis (RGD), interstitial granulomatous dermatitis (IGD) type secondary to vedolizumab. This adverse reaction has not, to our knowledge, been previously reported.

Case Report

A 61-year-old woman with a medical history of UC treated with vedolizumab and myelodysplastic syndrome treated with intravenous immunoglobulin (due to hypogammaglobulinemia following allogeneic stem cell transplantation 14 months prior) presented with a concern of a rash. The patient had been in a baseline state of health until 1 week after receiving her second dose of vedolizumab, at which time she developed a mildly pruritic maculopapular rash on the back and chest. Triamcinolone ointment and hydroxyzine were recommended during an initial telehealth consultation with an oncologist with minimal improvement. The rash continued to spread distally with worsening pruritus.

The patient returned to her oncologist for a routine follow-up appointment 5 days after initial teleconsultation. She reported poor oral intake due to oropharyngeal pain and a worsening rash; her husband added a report of recent onset of somnolence. She was admitted to the hospital, and intravenous fluids were administered.

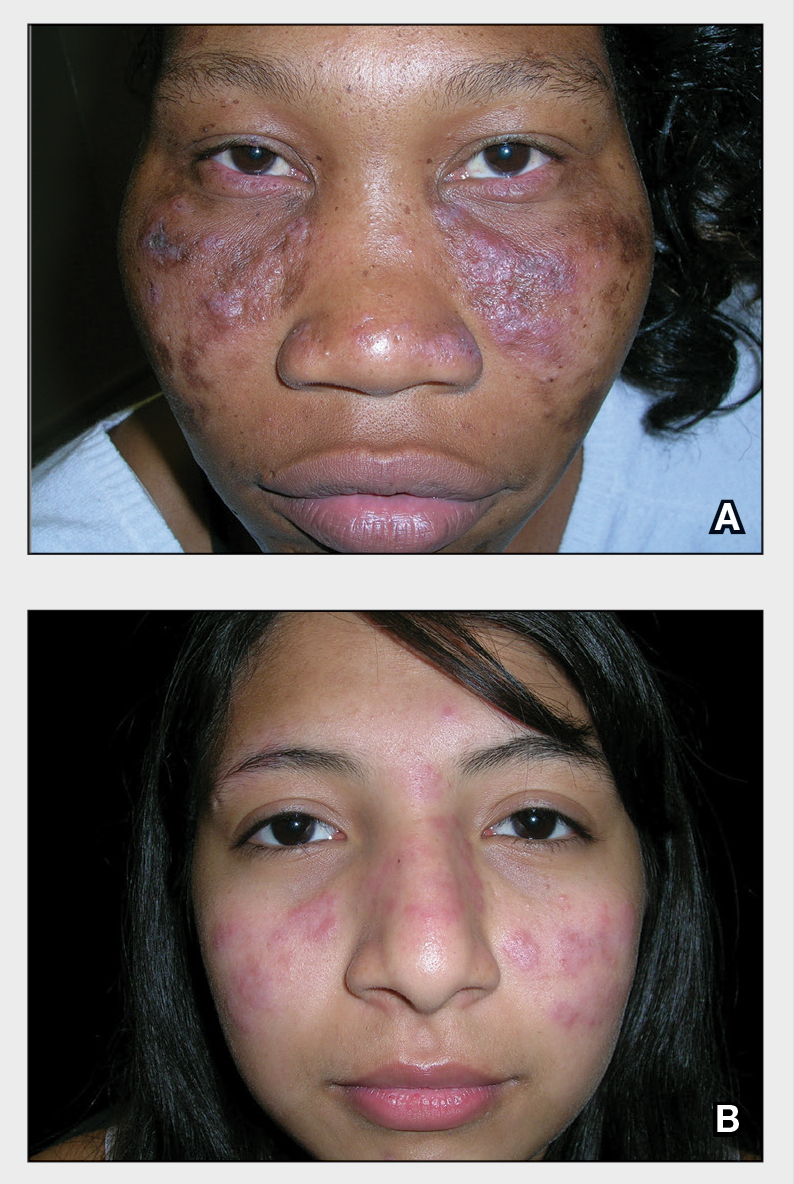

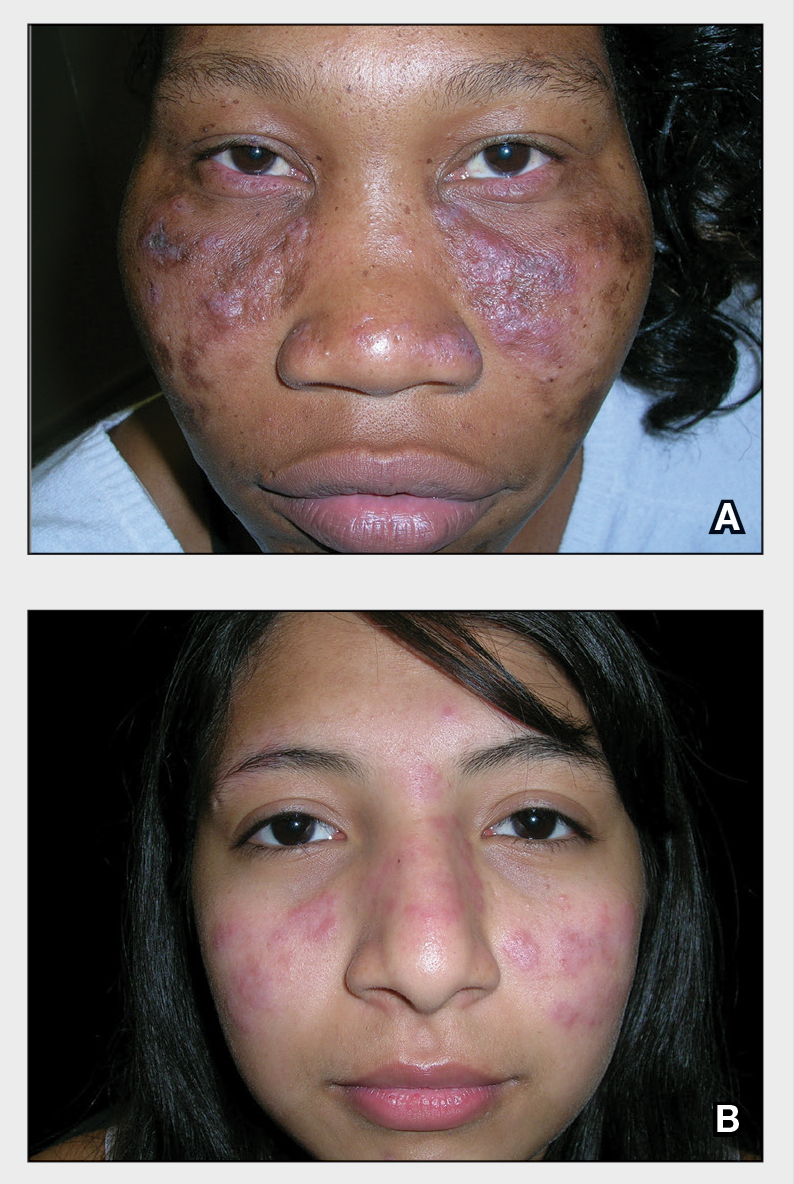

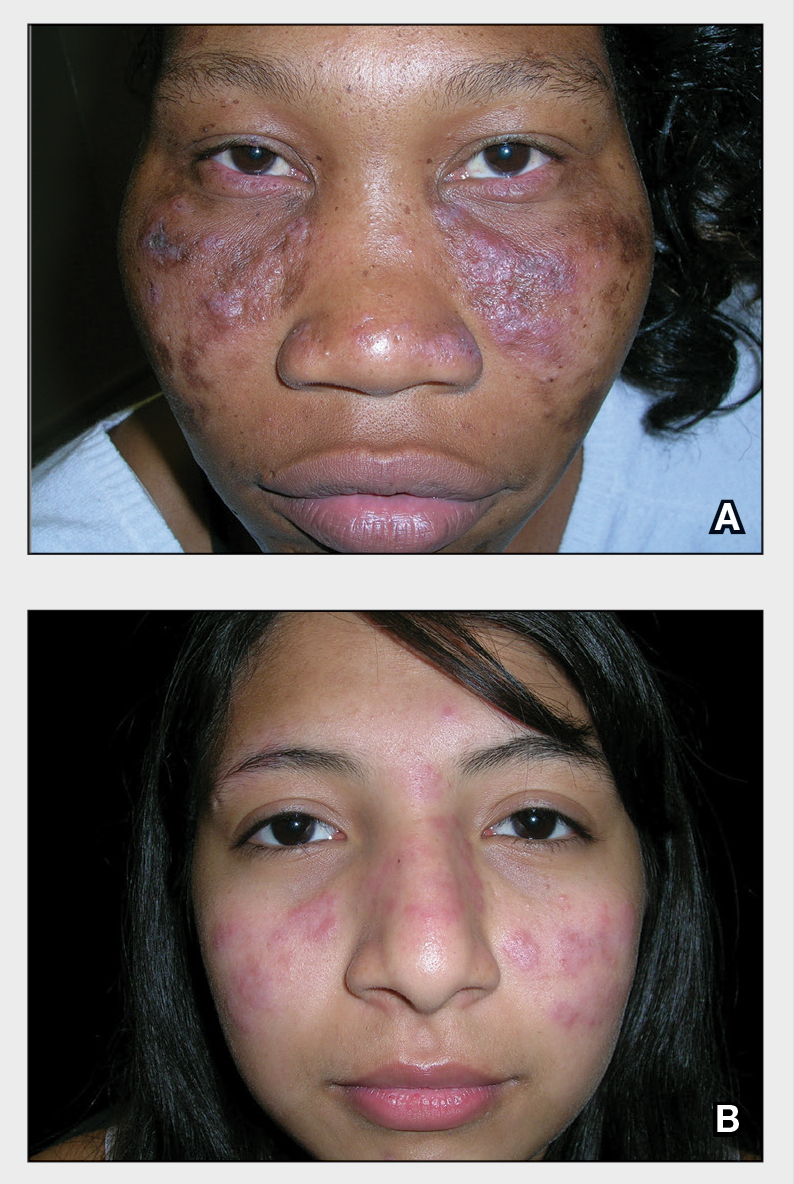

At admission, the patient was hypotensive; vital signs were otherwise normal. Physical examination revealed the oropharynx was erythematous. Pink lichenoid papules coalescing into plaques were present diffusely across the trunk, arms, and legs; the hands, feet, and face were spared (Figure 1).

A complete blood cell count and comprehensive metabolic panel were unremarkable. A lumbar puncture, chest radiograph, blood cultures, urinalysis, and urine cultures did not identify a clear infectious cause for the rash, though the workup for infection did raise concern about active cytomegalovirus (CMV) infection with colitis and pneumonitis. Computed tomography of the head showed no acute hemorrhage.

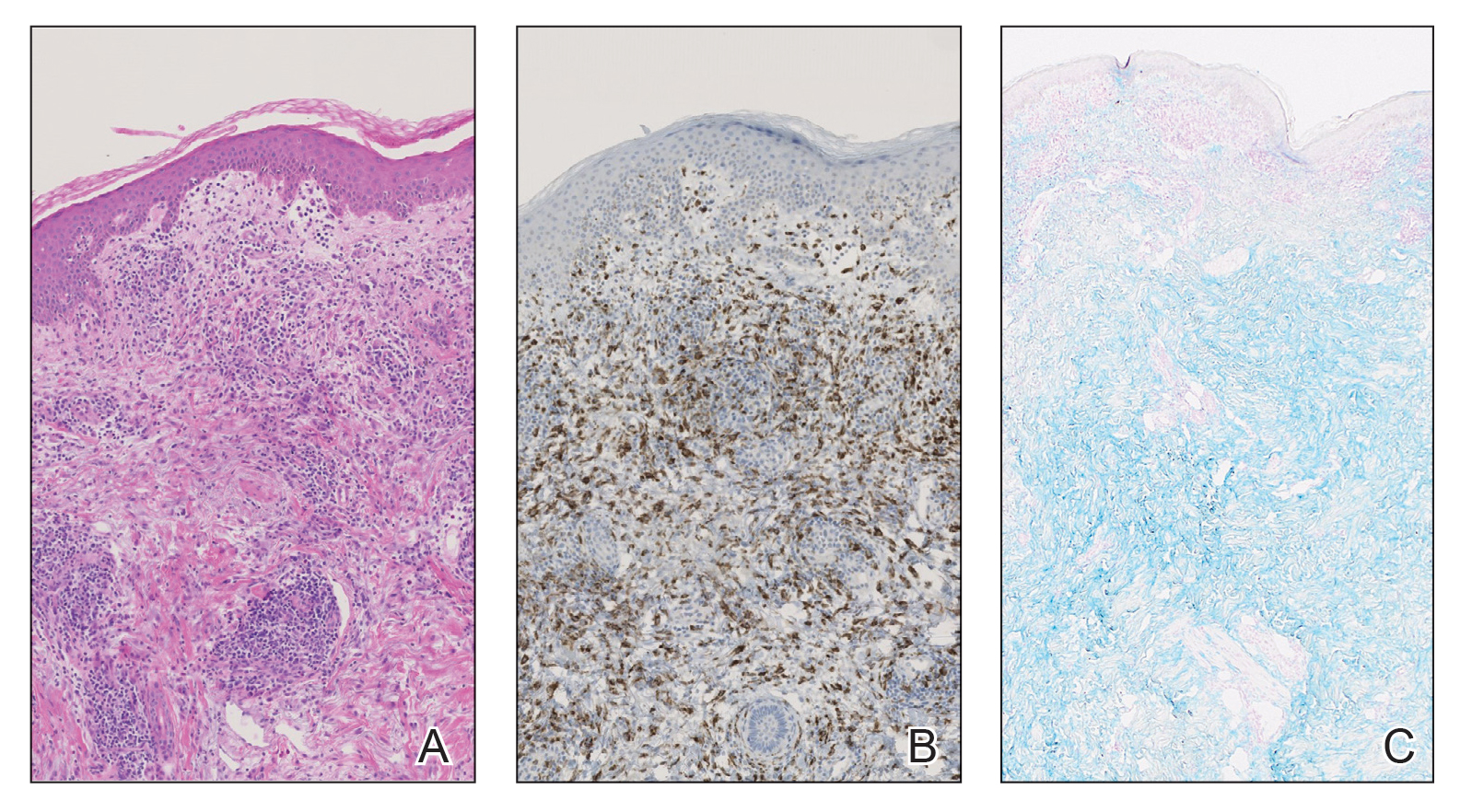

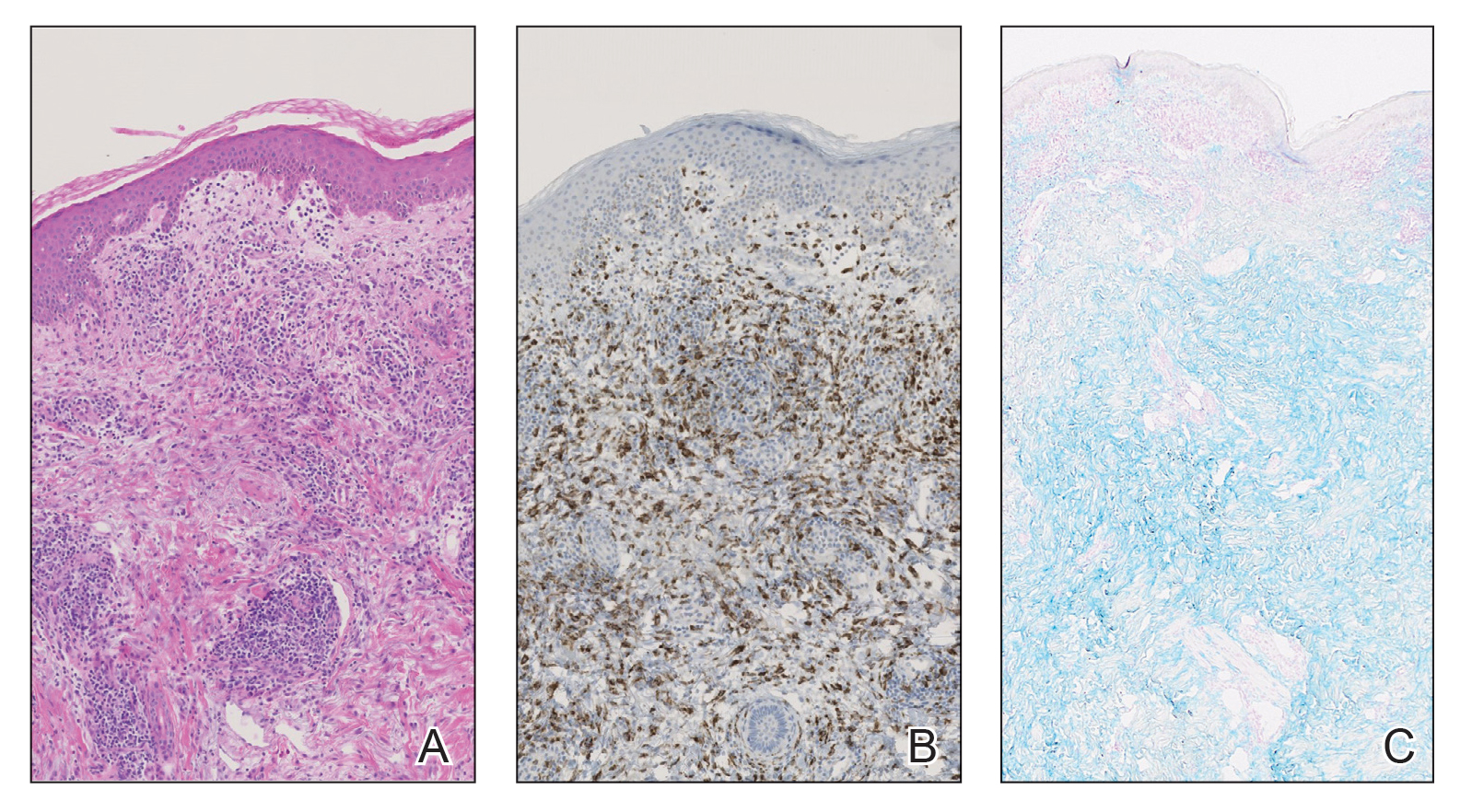

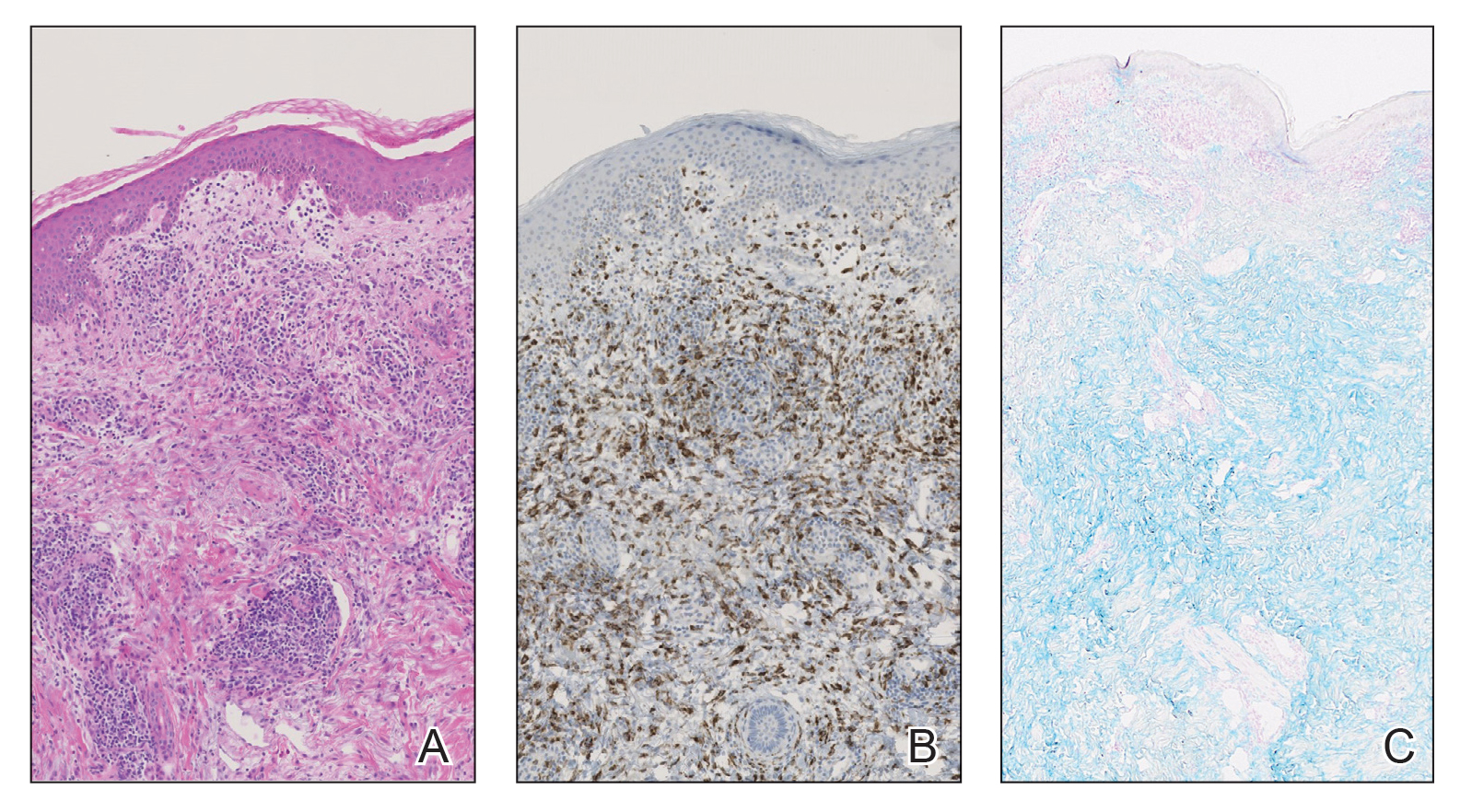

Dermatology was consulted and determined that the appearance of the rash was most consistent with a lichenoid drug eruption, likely secondary to vedolizumab that was administered 1 week before the rash onset. Analysis of a skin biopsy revealed a dense dermal histiocytic and lymphocytic infiltrate in close approximation to blood vessels, confirmed by immunohistochemical staining for CD45, CD43, CD68, CD34, c-KIT, and myeloperoxidase (Figures 2A and 2B). Colloidal iron staining of the specimen revealed no mucin (Figure 2C).

Taken together, the clinical presentation and histopathologic findings were determined to be most consistent with RGD, IGD type, with secondary vasculitis due to vedolizumab. The patient was treated with triamcinolone ointment and low-dose prednisone. Vedolizumab was discontinued. The rash resolved several weeks after cessation of vedolizumab.

Comment

This case describes the development of RGD, IGD type, as an AE of vedolizumab for the treatment of IBD. Reactive granulomatous dermatitis encompasses a spectrum of cutaneous reactions that includes the diagnosis formerly distinctly identified as IGD.11 This variety of RGD is characterized by histologic findings of heavy histiocytic inflammation in the reticular layer of the dermis with interstitial and perivascular neutrophils, lymphocytes, and histiocytes, as well as the absence of mucin. Interstitial granulomatous dermatitis–type reactions commonly are associated with autoimmune conditions and medications, with accumulating examples occurring in the setting of other biologic therapies, including the IL-6 receptor inhibitor tocilizumab; the programmed death receptor-1 inhibitor nivolumab; and the tumor necrosis factor α inhibitors infliximab, etanercept, and adalimumab.12-15

Although our patient represents CMV infection while being treated with vedolizumab, the relationship between the two is unclear. Development of CMV infection while receiving vedolizumab has been reported in the literature in a patient who was concurrently immunosuppressed with azathioprine.16 In contrast, vedolizumab administration has been utilized as a treatment of CMV infection in IBD patients, either alone or in combination with antiviral agents, with successful resolution of infection.17,18 Additional observations of the interaction between CMV infection and vedolizumab would be required to determine if the onset of CMV infection in this patient represents an additional risk of the medication.

Identifying a relationship between a monoclonal antibody therapy, such as vedolizumab, and RGD, IGD type, might be difficult in clinical practice, particularly if this type of reaction has not been previously associated with the culprit medication. In our patient, onset of cutaneous findings in relation to dosing of vedolizumab and exclusion of other possible causes of the rash supported the decision to stop vedolizumab. However, this decision often is challenging in patients with multiple concurrent medical conditions and those whose therapeutic options are limited.

Conclusion

Ulcerative colitis is not an uncommon condition; utilization of targeted monoclonal antibodies as a treatment strategy is expanding.2,19 As implementation of vedolizumab as a targeted biologic therapy for this disease increases, additional cases of IGD might emerge with greater frequency. Because IBD and autoimmune conditions have a tendency to coincide, awareness of the reaction presented here might be particularly important for dermatologists managing cutaneous manifestations of autoimmune conditions, as patients might present with a clinical picture complicated by preexisting skin findings.20 Furthermore, as reports of RGD, IGD type, in response to several monoclonal antibodies accumulate, it is prudent for all physicians to be aware of this potential complication of this class of medication so that they can make educated decisions about continuing monoclonal antibody therapy.

- Grilo AL, Mantalaris A. The increasingly human and profitable monoclonal antibody market. Trends Biotechnol. 2019;37:9-16. doi:10.1016/j.tibtech.2018.05.014

- Yu H, MacIsaac D, Wong JJ, et al. Market share and costs of biologic therapies for inflammatory bowel disease in the USA. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2018;47:364-370. doi:10.1111/apt.14430

- Wyant T, Fedyk E, Abhyankar B. An overview of the mechanism of action of the monoclonal antibody vedolizumab. J Crohns Colitis. 2016;10:1437-1444. doi:10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjw092

- Mosli MH, MacDonald JK, Bickston SJ, et al. Vedolizumab for induction and maintenance of remission in ulcerative colitis: a Cochrane systematic review and meta-analysis. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2015;21:1151-1159. doi:10.1097/MIB.0000000000000396

- Cohen RD, Bhayat F, Blake A, et al. The safety profile of vedolizumab in ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease: 4 years of global post-marketing data. J Crohns Colitis. 2020;14:192-204. doi:10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjz137

- Sands BE, Feagan BG, Rutgeerts P, et al. Effects of vedolizumab induction therapy for patients with Crohn’s disease in whom tumor necrosis factor antagonist treatment failed. Gastroenterology. 2014;147:618-627.e3. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2014.05.008

- Tadbiri S, Peyrin-Biroulet L, Serrero M, et al; . Impact of vedolizumab therapy on extra-intestinal manifestations in patients with inflammatory bowel disease: a multicentre cohort study nested in the OBSERV-IBD cohort. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2018;47:485-493. doi:10.1111/apt.14419

- Pereira Guedes T, Pedroto I, Lago P. Vedolizumab-associated psoriasis: until where does gut selectivity go? Rev Esp Enferm Dig. 2020;112:580-581. doi:10.17235/reed.2020.6817/2019

- Gold SL, Magro C, Scherl E. A unique infusion reaction to vedolizumab in a patient with Crohn’s disease. Gastroenterology. 2018;155:981-982. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2018.03.048

- Martínez Andrés B, Sastre Lozano V, Sánchez Melgarejo JF. Sweet syndrome after treatment with vedolizumab in a patient with Crohn’s disease. Rev Esp Enferm Dig. 2018;110:530. doi:10.17235/reed.2018.5603/2018

- Rosenbach M, English JC 3rd. Reactive granulomatous dermatitis: a review of palisaded neutrophilic and granulomatous dermatitis, interstitial granulomatous dermatitis, interstitial granulomatous drug reaction, and a proposed reclassification. Dermatol Clin. 2015;33:373-387. doi:10.1016/j.det.2015.03.005

- Crowson AN, Magro C. Interstitial granulomatous dermatitis with arthritis. Hum Pathol. 2004;35:779-780. doi:10.1016/j.humpath.2004.05.001

- Altemir A, Iglesias-Sancho M, Sola-Casas MdeLA, et al. Interstitial granulomatous dermatitis following tocilizumab, a paradoxical reaction? Dermatol Ther. 2020;33:e14207. doi:10.1111/dth.14207

- Singh P, Wolfe SP, Alloo A, et al. Interstitial granulomatous dermatitis and granulomatous arteritis in the setting of PD-1 inhibitor therapy for metastatic melanoma. J Cutan Pathol. 2020;47:65-69. doi:10.1111/cup.13562

- Deng A, Harvey V, Sina B, et al. Interstitial granulomatous dermatitis associated with the use of tumor necrosis factor alpha inhibitors. Arch Dermatol. 2006;142:198-202. doi:10.1001/archderm.142.2.198

- Bonfanti E, Bracco C, Biancheri P, et al. Fever during anti-integrin therapy: new immunodeficiency. Eur J Case Rep Intern Med. 2020;7:001288. doi:10.12890/2020_001288

- A, Lenarcik M, E. Resolution of CMV infection in the bowel on vedolizumab therapy. J Crohns Colitis. 2019;13:1234-1235. doi:10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjz033

- Hommel C, Pillet S, Rahier J-F. Comment on: ‘Resolution of CMV infection in the bowel on vedolizumab therapy’. J Crohns Colitis. 2020;14:148-149. doi:10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjz108

- Ng SC, Shi HY, Hamidi N, et al. Worldwide incidence and prevalence of inflammatory bowel disease in the 21st century: a systematic review of population-based studies. Lancet. 2017;390:2769-2778. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(17)32448-0

- Halling ML, Kjeldsen J, Knudsen T, et al. Patients with inflammatory bowel disease have increased risk of autoimmune and inflammatory diseases. World J Gastroenterol. 2017;23:6137-6146. doi:10.3748/wjg.v23.i33.6137

The number of monoclonal antibodies developed for therapeutic use has rapidly expanded over the last decade due to their generally favorable adverse effect (AE) profiles and efficacy.1 Tumor necrosis factor α inhibitors and general integrin antagonists are well-known examples of such monoclonal antibodies. Common conditions utilizing immunotherapy include inflammatory bowel diseases (IBDs), such as Crohn disease and ulcerative colitis (UC).2

The monoclonal antibody vedolizumab, approved in 2014 for moderate to severe UC and Crohn disease, selectively antagonizes α4β7 integrin to target a specific population of gastrointestinal T lymphocytes, preventing their mobilization to areas of inflammation.3 Adverse effects in patients treated with vedolizumab occur at a rate comparable to placebo and largely are considered nonserious4,5; the most commonly reported AE is disease exacerbation (13%–17% of patients).5,6 Published reports of cutaneous AEs at administration of vedolizumab include urticaria during infusion, appearance of cutaneous manifestations characteristic of IBD, psoriasis, Henoch-Schönlein purpura, and Sweet syndrome.7-10

We present the case of a 61-year-old woman with UC who developed reactive granulomatous dermatitis (RGD), interstitial granulomatous dermatitis (IGD) type secondary to vedolizumab. This adverse reaction has not, to our knowledge, been previously reported.

Case Report

A 61-year-old woman with a medical history of UC treated with vedolizumab and myelodysplastic syndrome treated with intravenous immunoglobulin (due to hypogammaglobulinemia following allogeneic stem cell transplantation 14 months prior) presented with a concern of a rash. The patient had been in a baseline state of health until 1 week after receiving her second dose of vedolizumab, at which time she developed a mildly pruritic maculopapular rash on the back and chest. Triamcinolone ointment and hydroxyzine were recommended during an initial telehealth consultation with an oncologist with minimal improvement. The rash continued to spread distally with worsening pruritus.

The patient returned to her oncologist for a routine follow-up appointment 5 days after initial teleconsultation. She reported poor oral intake due to oropharyngeal pain and a worsening rash; her husband added a report of recent onset of somnolence. She was admitted to the hospital, and intravenous fluids were administered.

At admission, the patient was hypotensive; vital signs were otherwise normal. Physical examination revealed the oropharynx was erythematous. Pink lichenoid papules coalescing into plaques were present diffusely across the trunk, arms, and legs; the hands, feet, and face were spared (Figure 1).

A complete blood cell count and comprehensive metabolic panel were unremarkable. A lumbar puncture, chest radiograph, blood cultures, urinalysis, and urine cultures did not identify a clear infectious cause for the rash, though the workup for infection did raise concern about active cytomegalovirus (CMV) infection with colitis and pneumonitis. Computed tomography of the head showed no acute hemorrhage.

Dermatology was consulted and determined that the appearance of the rash was most consistent with a lichenoid drug eruption, likely secondary to vedolizumab that was administered 1 week before the rash onset. Analysis of a skin biopsy revealed a dense dermal histiocytic and lymphocytic infiltrate in close approximation to blood vessels, confirmed by immunohistochemical staining for CD45, CD43, CD68, CD34, c-KIT, and myeloperoxidase (Figures 2A and 2B). Colloidal iron staining of the specimen revealed no mucin (Figure 2C).

Taken together, the clinical presentation and histopathologic findings were determined to be most consistent with RGD, IGD type, with secondary vasculitis due to vedolizumab. The patient was treated with triamcinolone ointment and low-dose prednisone. Vedolizumab was discontinued. The rash resolved several weeks after cessation of vedolizumab.

Comment

This case describes the development of RGD, IGD type, as an AE of vedolizumab for the treatment of IBD. Reactive granulomatous dermatitis encompasses a spectrum of cutaneous reactions that includes the diagnosis formerly distinctly identified as IGD.11 This variety of RGD is characterized by histologic findings of heavy histiocytic inflammation in the reticular layer of the dermis with interstitial and perivascular neutrophils, lymphocytes, and histiocytes, as well as the absence of mucin. Interstitial granulomatous dermatitis–type reactions commonly are associated with autoimmune conditions and medications, with accumulating examples occurring in the setting of other biologic therapies, including the IL-6 receptor inhibitor tocilizumab; the programmed death receptor-1 inhibitor nivolumab; and the tumor necrosis factor α inhibitors infliximab, etanercept, and adalimumab.12-15

Although our patient represents CMV infection while being treated with vedolizumab, the relationship between the two is unclear. Development of CMV infection while receiving vedolizumab has been reported in the literature in a patient who was concurrently immunosuppressed with azathioprine.16 In contrast, vedolizumab administration has been utilized as a treatment of CMV infection in IBD patients, either alone or in combination with antiviral agents, with successful resolution of infection.17,18 Additional observations of the interaction between CMV infection and vedolizumab would be required to determine if the onset of CMV infection in this patient represents an additional risk of the medication.

Identifying a relationship between a monoclonal antibody therapy, such as vedolizumab, and RGD, IGD type, might be difficult in clinical practice, particularly if this type of reaction has not been previously associated with the culprit medication. In our patient, onset of cutaneous findings in relation to dosing of vedolizumab and exclusion of other possible causes of the rash supported the decision to stop vedolizumab. However, this decision often is challenging in patients with multiple concurrent medical conditions and those whose therapeutic options are limited.

Conclusion

Ulcerative colitis is not an uncommon condition; utilization of targeted monoclonal antibodies as a treatment strategy is expanding.2,19 As implementation of vedolizumab as a targeted biologic therapy for this disease increases, additional cases of IGD might emerge with greater frequency. Because IBD and autoimmune conditions have a tendency to coincide, awareness of the reaction presented here might be particularly important for dermatologists managing cutaneous manifestations of autoimmune conditions, as patients might present with a clinical picture complicated by preexisting skin findings.20 Furthermore, as reports of RGD, IGD type, in response to several monoclonal antibodies accumulate, it is prudent for all physicians to be aware of this potential complication of this class of medication so that they can make educated decisions about continuing monoclonal antibody therapy.

The number of monoclonal antibodies developed for therapeutic use has rapidly expanded over the last decade due to their generally favorable adverse effect (AE) profiles and efficacy.1 Tumor necrosis factor α inhibitors and general integrin antagonists are well-known examples of such monoclonal antibodies. Common conditions utilizing immunotherapy include inflammatory bowel diseases (IBDs), such as Crohn disease and ulcerative colitis (UC).2

The monoclonal antibody vedolizumab, approved in 2014 for moderate to severe UC and Crohn disease, selectively antagonizes α4β7 integrin to target a specific population of gastrointestinal T lymphocytes, preventing their mobilization to areas of inflammation.3 Adverse effects in patients treated with vedolizumab occur at a rate comparable to placebo and largely are considered nonserious4,5; the most commonly reported AE is disease exacerbation (13%–17% of patients).5,6 Published reports of cutaneous AEs at administration of vedolizumab include urticaria during infusion, appearance of cutaneous manifestations characteristic of IBD, psoriasis, Henoch-Schönlein purpura, and Sweet syndrome.7-10

We present the case of a 61-year-old woman with UC who developed reactive granulomatous dermatitis (RGD), interstitial granulomatous dermatitis (IGD) type secondary to vedolizumab. This adverse reaction has not, to our knowledge, been previously reported.

Case Report

A 61-year-old woman with a medical history of UC treated with vedolizumab and myelodysplastic syndrome treated with intravenous immunoglobulin (due to hypogammaglobulinemia following allogeneic stem cell transplantation 14 months prior) presented with a concern of a rash. The patient had been in a baseline state of health until 1 week after receiving her second dose of vedolizumab, at which time she developed a mildly pruritic maculopapular rash on the back and chest. Triamcinolone ointment and hydroxyzine were recommended during an initial telehealth consultation with an oncologist with minimal improvement. The rash continued to spread distally with worsening pruritus.

The patient returned to her oncologist for a routine follow-up appointment 5 days after initial teleconsultation. She reported poor oral intake due to oropharyngeal pain and a worsening rash; her husband added a report of recent onset of somnolence. She was admitted to the hospital, and intravenous fluids were administered.

At admission, the patient was hypotensive; vital signs were otherwise normal. Physical examination revealed the oropharynx was erythematous. Pink lichenoid papules coalescing into plaques were present diffusely across the trunk, arms, and legs; the hands, feet, and face were spared (Figure 1).

A complete blood cell count and comprehensive metabolic panel were unremarkable. A lumbar puncture, chest radiograph, blood cultures, urinalysis, and urine cultures did not identify a clear infectious cause for the rash, though the workup for infection did raise concern about active cytomegalovirus (CMV) infection with colitis and pneumonitis. Computed tomography of the head showed no acute hemorrhage.

Dermatology was consulted and determined that the appearance of the rash was most consistent with a lichenoid drug eruption, likely secondary to vedolizumab that was administered 1 week before the rash onset. Analysis of a skin biopsy revealed a dense dermal histiocytic and lymphocytic infiltrate in close approximation to blood vessels, confirmed by immunohistochemical staining for CD45, CD43, CD68, CD34, c-KIT, and myeloperoxidase (Figures 2A and 2B). Colloidal iron staining of the specimen revealed no mucin (Figure 2C).

Taken together, the clinical presentation and histopathologic findings were determined to be most consistent with RGD, IGD type, with secondary vasculitis due to vedolizumab. The patient was treated with triamcinolone ointment and low-dose prednisone. Vedolizumab was discontinued. The rash resolved several weeks after cessation of vedolizumab.

Comment

This case describes the development of RGD, IGD type, as an AE of vedolizumab for the treatment of IBD. Reactive granulomatous dermatitis encompasses a spectrum of cutaneous reactions that includes the diagnosis formerly distinctly identified as IGD.11 This variety of RGD is characterized by histologic findings of heavy histiocytic inflammation in the reticular layer of the dermis with interstitial and perivascular neutrophils, lymphocytes, and histiocytes, as well as the absence of mucin. Interstitial granulomatous dermatitis–type reactions commonly are associated with autoimmune conditions and medications, with accumulating examples occurring in the setting of other biologic therapies, including the IL-6 receptor inhibitor tocilizumab; the programmed death receptor-1 inhibitor nivolumab; and the tumor necrosis factor α inhibitors infliximab, etanercept, and adalimumab.12-15

Although our patient represents CMV infection while being treated with vedolizumab, the relationship between the two is unclear. Development of CMV infection while receiving vedolizumab has been reported in the literature in a patient who was concurrently immunosuppressed with azathioprine.16 In contrast, vedolizumab administration has been utilized as a treatment of CMV infection in IBD patients, either alone or in combination with antiviral agents, with successful resolution of infection.17,18 Additional observations of the interaction between CMV infection and vedolizumab would be required to determine if the onset of CMV infection in this patient represents an additional risk of the medication.

Identifying a relationship between a monoclonal antibody therapy, such as vedolizumab, and RGD, IGD type, might be difficult in clinical practice, particularly if this type of reaction has not been previously associated with the culprit medication. In our patient, onset of cutaneous findings in relation to dosing of vedolizumab and exclusion of other possible causes of the rash supported the decision to stop vedolizumab. However, this decision often is challenging in patients with multiple concurrent medical conditions and those whose therapeutic options are limited.

Conclusion

Ulcerative colitis is not an uncommon condition; utilization of targeted monoclonal antibodies as a treatment strategy is expanding.2,19 As implementation of vedolizumab as a targeted biologic therapy for this disease increases, additional cases of IGD might emerge with greater frequency. Because IBD and autoimmune conditions have a tendency to coincide, awareness of the reaction presented here might be particularly important for dermatologists managing cutaneous manifestations of autoimmune conditions, as patients might present with a clinical picture complicated by preexisting skin findings.20 Furthermore, as reports of RGD, IGD type, in response to several monoclonal antibodies accumulate, it is prudent for all physicians to be aware of this potential complication of this class of medication so that they can make educated decisions about continuing monoclonal antibody therapy.

- Grilo AL, Mantalaris A. The increasingly human and profitable monoclonal antibody market. Trends Biotechnol. 2019;37:9-16. doi:10.1016/j.tibtech.2018.05.014

- Yu H, MacIsaac D, Wong JJ, et al. Market share and costs of biologic therapies for inflammatory bowel disease in the USA. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2018;47:364-370. doi:10.1111/apt.14430

- Wyant T, Fedyk E, Abhyankar B. An overview of the mechanism of action of the monoclonal antibody vedolizumab. J Crohns Colitis. 2016;10:1437-1444. doi:10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjw092

- Mosli MH, MacDonald JK, Bickston SJ, et al. Vedolizumab for induction and maintenance of remission in ulcerative colitis: a Cochrane systematic review and meta-analysis. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2015;21:1151-1159. doi:10.1097/MIB.0000000000000396

- Cohen RD, Bhayat F, Blake A, et al. The safety profile of vedolizumab in ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease: 4 years of global post-marketing data. J Crohns Colitis. 2020;14:192-204. doi:10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjz137

- Sands BE, Feagan BG, Rutgeerts P, et al. Effects of vedolizumab induction therapy for patients with Crohn’s disease in whom tumor necrosis factor antagonist treatment failed. Gastroenterology. 2014;147:618-627.e3. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2014.05.008

- Tadbiri S, Peyrin-Biroulet L, Serrero M, et al; . Impact of vedolizumab therapy on extra-intestinal manifestations in patients with inflammatory bowel disease: a multicentre cohort study nested in the OBSERV-IBD cohort. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2018;47:485-493. doi:10.1111/apt.14419

- Pereira Guedes T, Pedroto I, Lago P. Vedolizumab-associated psoriasis: until where does gut selectivity go? Rev Esp Enferm Dig. 2020;112:580-581. doi:10.17235/reed.2020.6817/2019

- Gold SL, Magro C, Scherl E. A unique infusion reaction to vedolizumab in a patient with Crohn’s disease. Gastroenterology. 2018;155:981-982. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2018.03.048

- Martínez Andrés B, Sastre Lozano V, Sánchez Melgarejo JF. Sweet syndrome after treatment with vedolizumab in a patient with Crohn’s disease. Rev Esp Enferm Dig. 2018;110:530. doi:10.17235/reed.2018.5603/2018

- Rosenbach M, English JC 3rd. Reactive granulomatous dermatitis: a review of palisaded neutrophilic and granulomatous dermatitis, interstitial granulomatous dermatitis, interstitial granulomatous drug reaction, and a proposed reclassification. Dermatol Clin. 2015;33:373-387. doi:10.1016/j.det.2015.03.005

- Crowson AN, Magro C. Interstitial granulomatous dermatitis with arthritis. Hum Pathol. 2004;35:779-780. doi:10.1016/j.humpath.2004.05.001

- Altemir A, Iglesias-Sancho M, Sola-Casas MdeLA, et al. Interstitial granulomatous dermatitis following tocilizumab, a paradoxical reaction? Dermatol Ther. 2020;33:e14207. doi:10.1111/dth.14207