User login

Learning Experiences in LGBT Health During Dermatology Residency

Approximately 4.5% of adults within the United States identify as members of the lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender (LGBT) community.1 This is an umbrella term inclusive of all individuals identifying as nonheterosexual or noncisgender. Although the LGBT community has increasingly become more recognized and accepted by society over time, health care disparities persist and have been well documented in the literature.2-4 Dermatologists have the potential to greatly impact LGBT health, as many health concerns in this population are cutaneous, such as sun-protection behaviors, side effects of gender-affirming hormone therapy and gender-affirming procedures, and cutaneous manifestations of sexually transmitted infections.5-7

An education gap has been demonstrated in both medical students and resident physicians regarding LGBT health and cultural competency. In a large-scale, multi-institutional survey study published in 2015, approximately two-thirds of medical students rated their schools’ LGBT curriculum as fair, poor, or very poor.8 Additional studies have echoed these results and have demonstrated not only the need but the desire for additional training on LGBT issues in medical school.9-11 The Association of American Medical Colleges has begun implementing curricular and institutional changes to fulfill this need.12,13

The LGBT education gap has been shown to extend into residency training. Multiple studies performed within a variety of medical specialties have demonstrated that resident physicians receive insufficient training in LGBT health issues, lack comfort in caring for LGBT patients, and would benefit from dedicated curricula on these topics.14-18 Currently, the 2022 Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) guidelines related to LGBT health are minimal and nonspecific.19

Ensuring that dermatology trainees are well equipped to manage these issues while providing culturally competent care to LGBT patients is paramount. However, research suggests that dedicated training on these topics likely is insufficient. A survey study of dermatology residency program directors (N=90) revealed that although 81% (72/89) viewed training in LGBT health as either very important or somewhat important, 46% (41/90) of programs did not dedicate any time to this content and 37% (33/90) only dedicated 1 to 2 hours per year.20

To further explore this potential education gap, we surveyed dermatology residents directly to better understand LGBT education within residency training, resident preparedness to care for LGBT patients, and outness/discrimination of LGBT-identifying residents. We believe this study should drive future research on the development and implementation of LGBT-specific curricula in dermatology training programs.

Methods

A cross-sectional survey study of dermatology residents in the United States was conducted. The study was deemed exempt from review by The Ohio State University (Columbus, Ohio) institutional review board. Survey responses were collected from October 7, 2020, to November 13, 2020. Qualtrics software was used to create the 20-question survey, which included a combination of categorical, dichotomous, and optional free-text questions related to patient demographics, LGBT training experiences, perceived areas of curriculum improvement, comfort level managing LGBT health issues, and personal experiences. Some questions were adapted from prior surveys.15,21 Validated survey tools used included the 2020 US Census to collect information regarding race and ethnicity, the Mohr and Fassinger Outness Inventory to measure outness regarding sexual orientation, and select questions from the 2020 Association of American Medical Colleges Medical School Graduation Questionnaire regarding discrimination.22-24

The survey was distributed to current allopathic and osteopathic dermatology residents by a variety of methods, including emails to program director and program coordinator listserves. The survey also was posted in the American Academy of Dermatology Expert Resource Group on LGBTQ Health October 2020 newsletter, as well as dermatology social media groups, including a messaging forum limited to dermatology residents, a Facebook group open to dermatologists and dermatology residents, and the Facebook group of the Gay and Lesbian Dermatology Association. Current dermatology residents, including those in combined dermatology and internal medicine programs, were included. Individuals who had been accepted to dermatology training programs but had not yet started were excluded. A follow-up email was sent to the program director listserve approximately 3 weeks after the initial distribution.

Statistical Analysis—The data were analyzed in Qualtrics and Microsoft Excel using descriptive statistics. Stata software (Stata 15.1, StataCorp) was used to perform a Kruskal-Wallis equality-of-populations rank test to compare the means of education level and feelings of preparedness.

Results

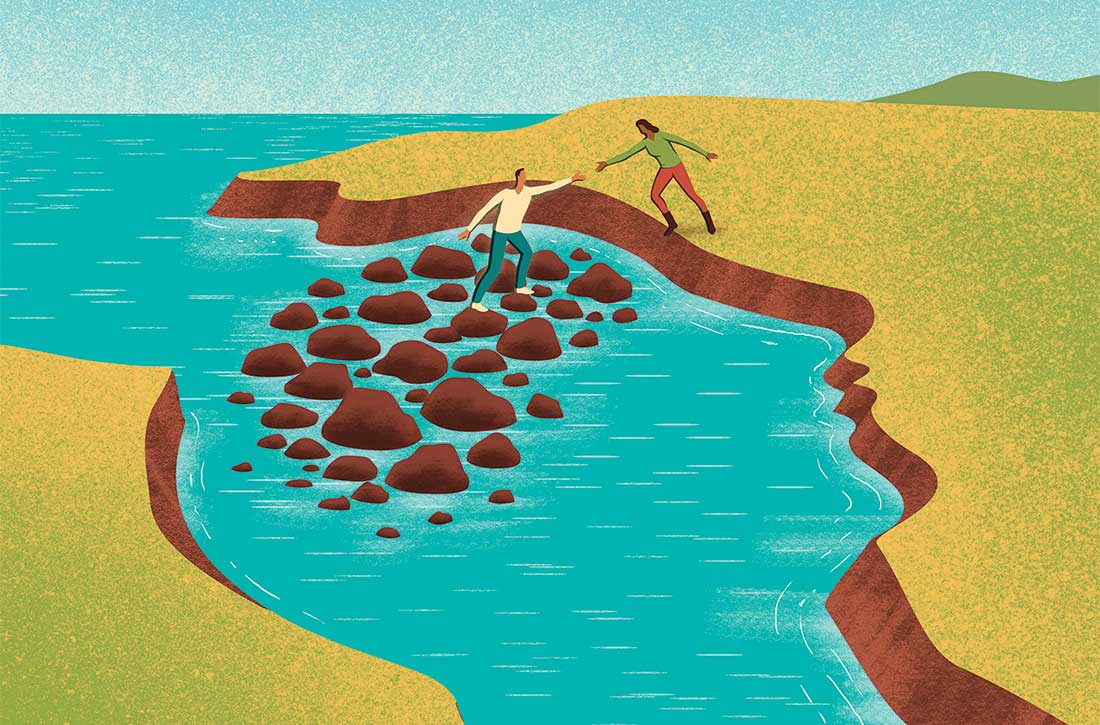

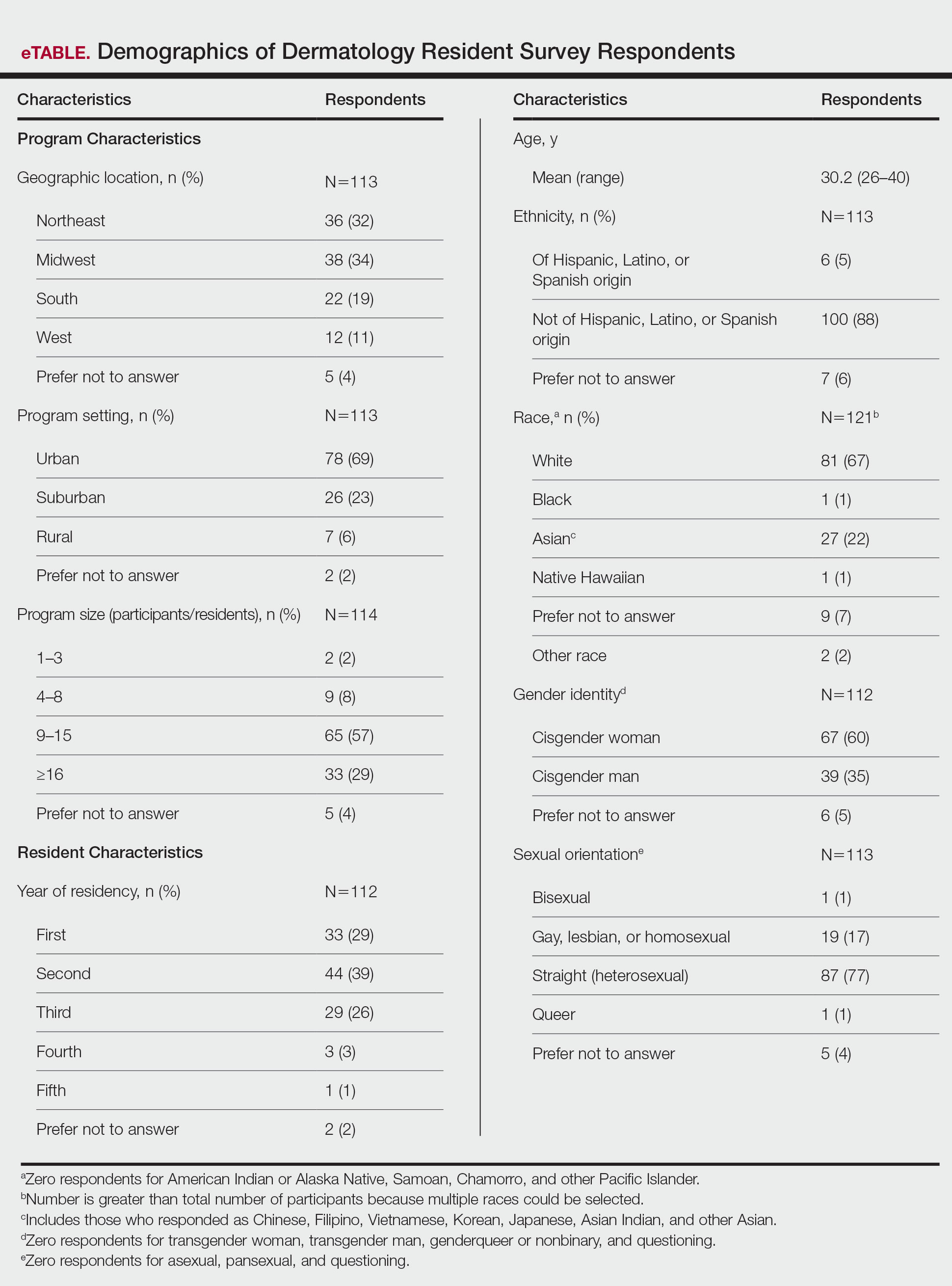

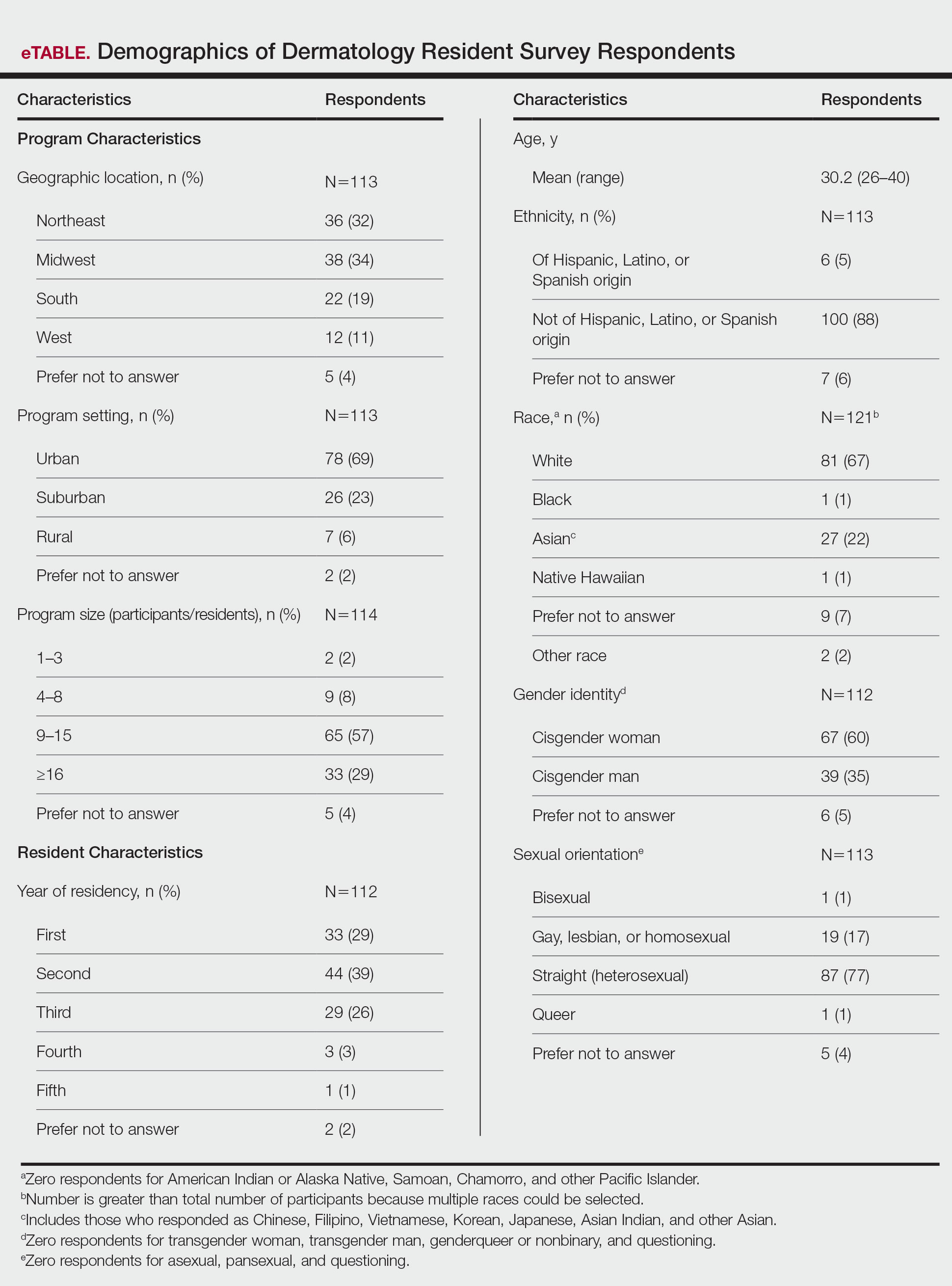

Demographics of Respondents—A total of 126 responses were recorded, 12 of which were blank and were removed from the database. A total of 114 dermatology residents’ responses were collected in Qualtrics and analyzed; 91 completed the entire survey (an 80% completion rate). Based on the 2020-2021 ACGME data listing, there were 1612 dermatology residents in the United States, which is an estimated response rate of 7% (114/1612).25 The eTable outlines the demographics of the survey respondents. Most were cisgender females (60%), followed by cisgender males (35%); the remainder preferred not to answer. Regarding sexual orientation, 77% identified as straight or heterosexual; 17% as gay, lesbian, or homosexual; 1% as queer; and 1% as bisexual. The training programs were in 26 states, the majority of which were in the Midwest (34%) and in urban settings (69%). A wide range of postgraduate levels and residency sizes were represented in the survey.

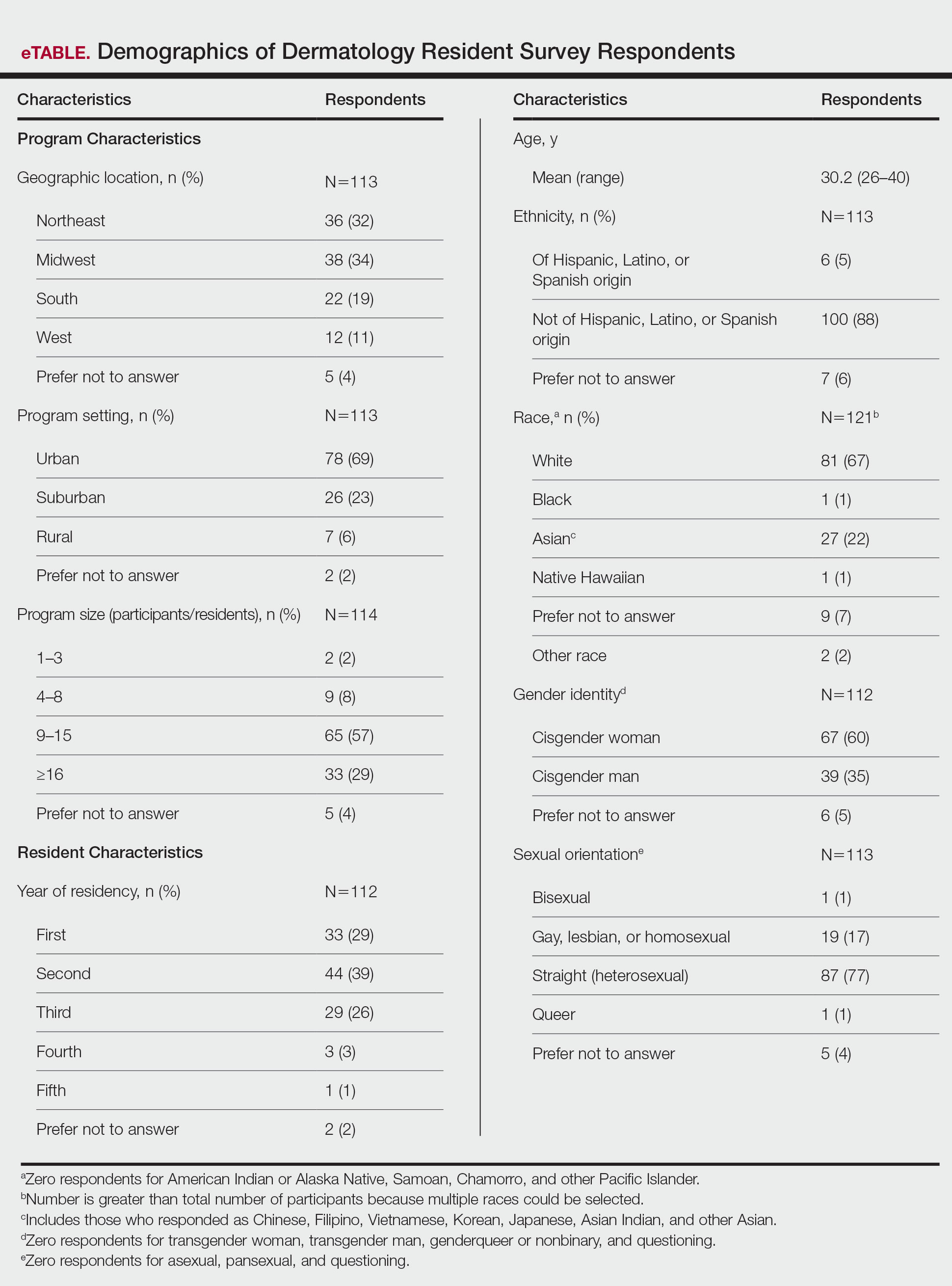

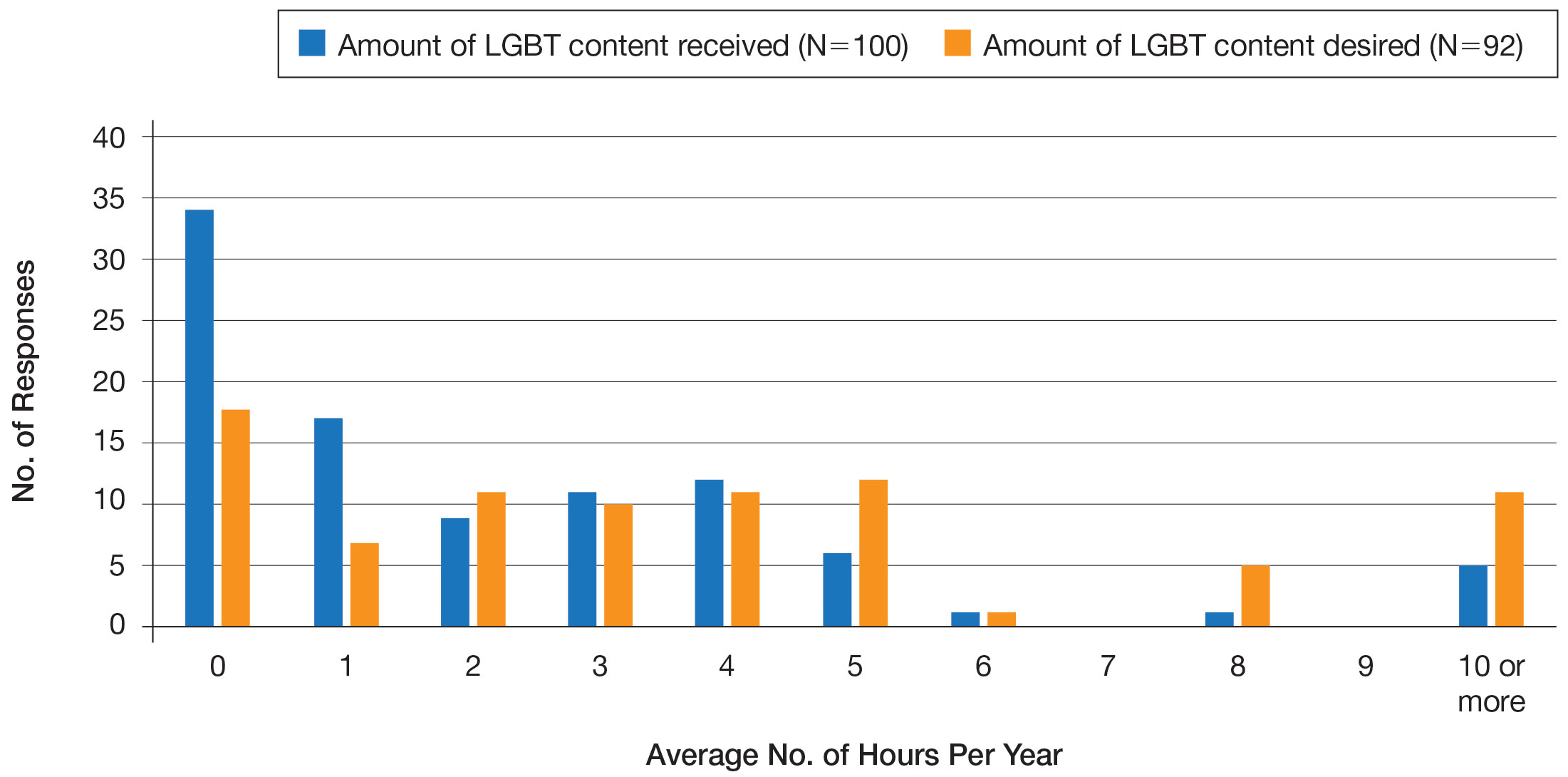

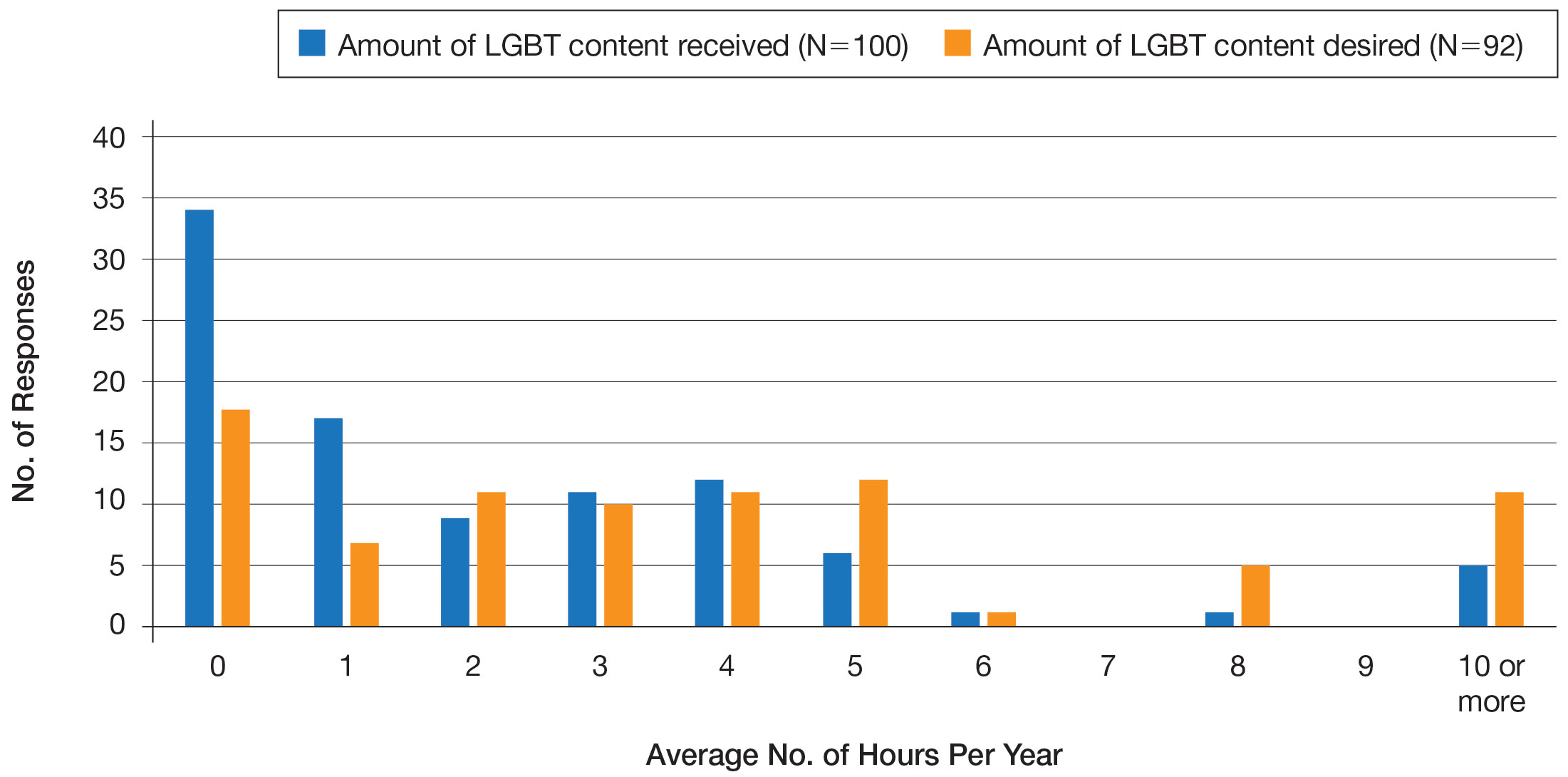

LGBT Education—Fifty-one percent of respondents reported that their programs offer 1 hour or less of LGBT-related curricula per year; 34% reported no time dedicated to this topic. A small portion of residents (5%) reported 10 or more hours of LGBT education per year. Residents also were asked the average number of hours of LGBT education they thought they should receive. The discrepancy between these measures can be visualized in Figure 1. The median hours of education received was 1 hour (IQR, 0–4 hours), whereas the median hours of education desired was 4 hours (IQR, 2–5 hours). The most common and most helpful methods of education reported were clinical experiences with faculty or patients and live lectures.

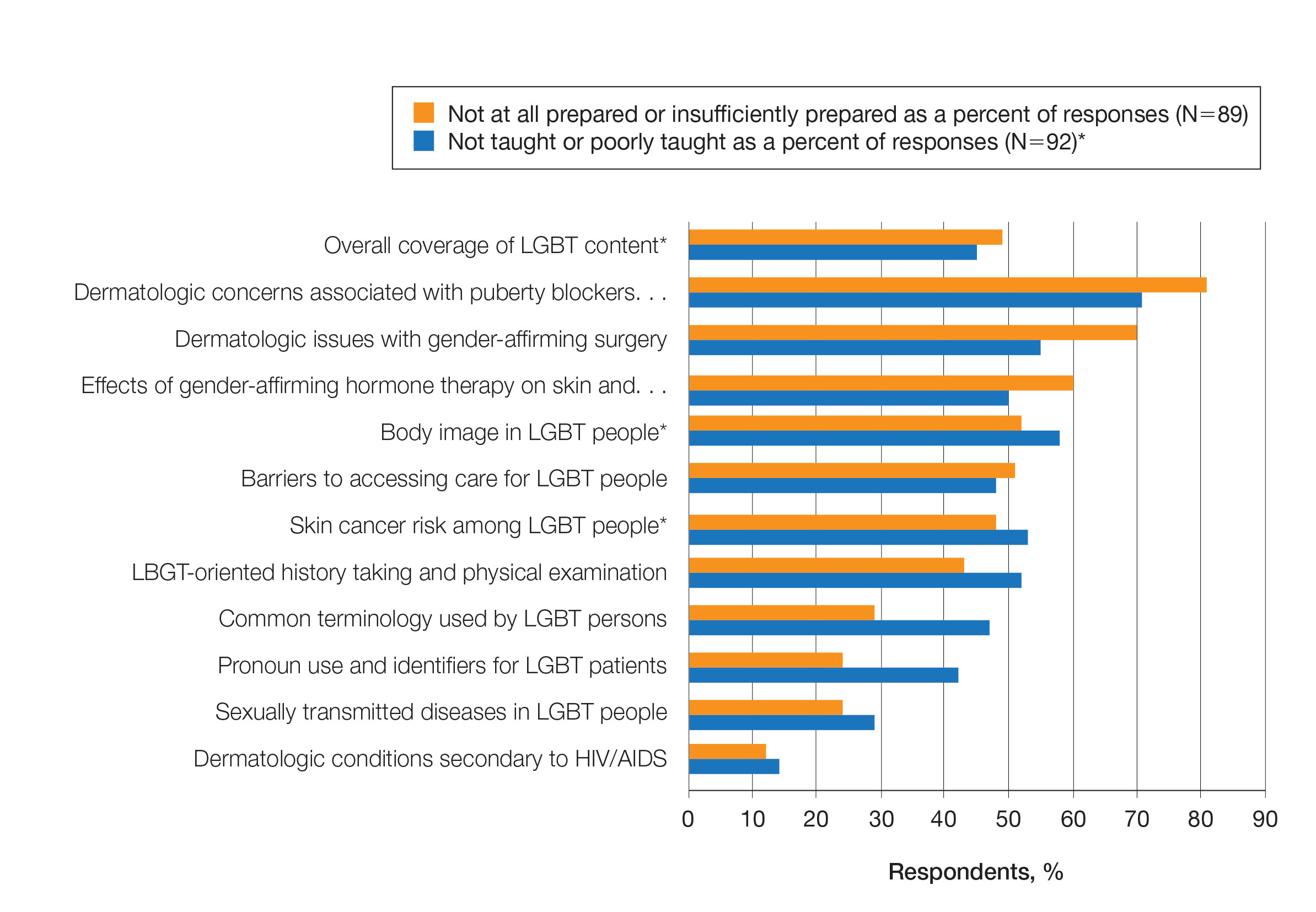

Overall, 45% of survey respondents felt that LGBT topics were covered poorly or not at all in dermatology residency, whereas 26% thought the coverage was good or excellent. The topics that residents were most likely to report receiving good or excellent coverage were dermatologic manifestations of HIV/AIDS (70%) and sexually transmitted diseases in LGBT patients (48%). The topics that were most likely to be reported as not taught or poorly taught included dermatologic concerns associated with puberty blockers (71%), body image (58%), dermatologic concerns associated with gender-affirming surgery (55%), skin cancer risk (53%), taking an LGBT-oriented history and physical examination (52%), and effects of gender-affirming hormone therapy on the skin (50%). A detailed breakdown of coverage level by topic can be found in Figure 2.

Preparedness to Care for LGBT Patients—Only 68% of survey respondents agreed or strongly agreed that they feel comfortable treating LGBT patients. Furthermore, 49% of dermatology residents reported that they feel not at all prepared or insufficiently prepared to provide care to LGBT individuals (Figure 2), and 60% believed that LGBT training needed to be improved at their residency programs.

There was a significant association between reported level of education and feelings of preparedness. A high ranking of provided education was associated with higher levels of feeling prepared to care for LGBT patients (Kruskal-Wallis rank test, P<.001).

Discrimination/Outness—Approximately one-fourth (24%; 4/17) of nonheterosexual dermatology residents reported that they had been subjected to offensive remarks about their sexual orientation in the workplace. One respondent commented that they were less “out” at their residency program due to fear of discrimination. Nearly one-third of the overall group of dermatology residents surveyed (29%; 27/92) reported that they had witnessed inappropriate or discriminatory comments about LGBT persons made by employees or staff at their programs. Most residents surveyed (96%; 88/92) agreed or strongly agreed that they feel comfortable working alongside LGBT physicians.

There were 18 nonheterosexual dermatologyresidents who completed the Mohr and Fassinger Outness Inventory.23 In general, respondents reported that they were more “out” with friends and family than work peers and were least “out” with work supervisors and strangers.

Comment

Dermatology Residents Desire More Time on LGBT Health—This cross-sectional survey study explored dermatology residents’ educational experiences with LGBT health during residency training. Similar studies have been performed in other specialties, including a study from 2019 surveying emergency medicine residents that demonstrated residents find caring for LGBT patients more challenging.15 Another 2019 study surveying psychiatry residents found that 42.4% (N=99) reported no coverage of LGBT topics.18 Our study is unique in that it surveyed dermatology residents directly regarding this topic. Although most dermatology program directors view LGBT dermatologic health as an important topic, a prior study revealed that many programs are lacking dedicated LGBT educational experiences. The most common barriers reported were insufficient time in the didactic schedule and lack of experienced faculty.20

Our study revealed that dermatology residents overall tend to agree with residents from other specialties and dermatology program directors. Most of the dermatology residents surveyed reported desiring more time per year spent on LGBT health education than they receive, and 60% expressed that LGBT educational experiences need to be improved at their residency programs. Education on and subsequent comfort level with LGBT health issues varied by subtopic, with most residents feeling comfortable dealing with dermatologic manifestations of HIV/AIDS and other sexually transmitted diseases and less comfortable with topics such as puberty blockers, gender-affirming surgery and hormone therapy, body image, and skin cancer risk.

Overall, LGBT health training is viewed as important and in need of improvement by both program directors and residents, yet implementation lags at many programs. A small proportion of the represented programs are excelling in this area—just over 5% of respondents reported receiving 10 or more hours of LGBT-relevant education per year, and approximately 26% of residents felt that LGBT coverage was good or excellent at their programs. Our study showed a clear relationship between feelings of preparedness and education level. The lack of LGBT education at some dermatology residency programs translated into a large portion of dermatology residents feeling ill equipped to care for LGBT patients after graduation—nearly 50% of those surveyed reported feeling insufficiently prepared to care for the LGBT community.

Discrimination in Residency Programs—Dermatology residency programs also are not free from sexual orientation–related and gender identity–related workplace discrimination. Although 96% of dermatology residents reported that they feel comfortable working alongside LGBT physicians, 24% of nonheterosexual respondents stated they had been subjected to offensive remarks about their sexual orientation, and 29% of the overall group of dermatology residents had witnessed discriminatory comments to LGBT individuals at their programs. In addition, some nonheterosexual dermatology residents reported being less “out” with their workplace supervisors and strangers, such as patients, than with their family and friends, and 50% of this group reported that their sexual identity was not openly discussed with their workplace supervisors. It has been demonstrated that individuals are more likely to “come out” in perceived LGBT-friendly workplace environments and that being “out” positively impacts psychological health because of the effects of perceived social support and self-coherence.26,27

Study Strengths and Limitations—Strengths of this study include the modest sample size of dermatology residents that participated, high completion rate, and the anonymity of the survey. Limitations include the risk of sampling bias by posting the survey on LGBT-specific groups. The survey also took place in the fall, so the results may not accurately reflect programs that cover this material later in the academic year. Lastly, not all survey questions were validated.

Implementing Change in Residency Programs—Although the results of this study exposed the need for increasing LGBT education in dermatology residency, they do not provide guidelines for the best strategy to begin implementing change. A study from 2020 provides some guidance for incorporating LGBT health training into dermatology residency programs through a combination of curricular modifications and climate optimization.28 Additional future research should focus on the best methods for preparing dermatology residents to care for this population. In this study, residents reported that the most effective teaching methods were real encounters with LGBT patients or faculty educated on LGBT health as well as live lectures from experts. There also appeared to be a correlation between hours spent on LGBT health, including various subtopics, and residents’ perceived preparedness in these areas. Potential actionable items include clarifying the ACGME guidelines on LGBT health topics; increasing the sexual and gender diversity of the faculty, staff, residents, and patients; and dedicating additional didactic and clinical time to LGBT topics and experiences.

Conclusion

This survey study of dermatology residents regarding LGBT learning experiences in residency training provided evidence that dermatology residents as a whole are not adequately taught LGBT health topics and therefore feel unprepared to take care of this patient population. Additionally, most residents desire improvement of LGBT health education and training. Further studies focusing on the best methods for implementing LGBT-specific curricula are needed.

- Newport F. In U.S., estimate of LGBT population rises to 4.5%. Gallup. May 22, 2018. Accessed September 19, 2022. https://news.gallup.com/poll/234863/estimate-lgbt-population-rises.aspx

- Hafeez H, Zeshan M, Tahir MA, et al. Health care disparities among lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender youth: a literature review. Cureus. 2017;9:E1184.

- Gonzales G, Henning-Smith C. Barriers to care among transgender and gender nonconforming adults. Millbank Q. 2017;95:726-748.

- Quinn GP, Sanchez JA, Sutton SK, et al. Cancer and lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender/transsexual, and queer/questioning (LGBTQ) populations. CA Cancer J Clin. 2015;65:384-400.

- Sullivan P, Trinidad J, Hamann D. Issues in transgender dermatology: a systematic review of the literature. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;81:438-447.

- Yeung H, Luk KM, Chen SC, et al. Dermatologic care for lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender persons: epidemiology, screening, and disease prevention. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80:591-602.

- Yeung H, Luk KM, Chen SC, et al. Dermatologic care for lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender persons: terminology, demographics, health disparities, and approaches to care. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80:581-589.

- White W, Brenman S, Paradis E, et al. Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender patient care: medical students’ preparedness and comfort. Teach Learn Med. 2015;27:254-263.

- Nama N, MacPherson P, Sampson M, et al. Medical students’ perception of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) discrimination in their learning environment and their self-reported comfort level for caring for LGBT patients: a survey study. Med Educ Online. 2017;22:1-8.

- Phelan SM, Burke SE, Hardeman RR, et al. Medical school factors associated with changes in implicit and explicit bias against gay and lesbian people among 3492 graduating medical students. J Gen Intern Med. 2017;32:1193-1201.

- Cherabie J, Nilsen K, Houssayni S. Transgender health medical education intervention and its effects on beliefs, attitudes, comfort, and knowledge. Kans J Med. 2018;11:106-109.

- Integrating LGBT and DSD content into medical school curricula. Association of American Medical Colleges website. Published November 2015. Accessed September 23, 2022. https://www.aamc.org/what-we-do/equity-diversity-inclusion/lgbt-health-resources/videos/curricula-integration

- Cooper MB, Chacko M, Christner J. Incorporating LGBT health in an undergraduate medical education curriculum through the construct of social determinants of health. MedEdPORTAL. 2018;14:10781.

- Moll J, Krieger P, Moreno-Walton L, et al. The prevalence of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender health education and training in emergency medicine residency programs: what do we know? Acad Emerg Med. 2014;21:608-611.

- Moll J, Krieger P, Heron SL, et al. Attitudes, behavior, and comfort of emergency medicine residents in caring for LGBT patients: what do we know? AEM Educ Train. 2019;3:129-135.

- Hirschtritt ME, Noy G, Haller E, et al. LGBT-specific education in general psychiatry residency programs: a survey of program directors. Acad Psychiatry. 2019;43:41-45.

- Ufomata E, Eckstrand KL, Spagnoletti C, et al. Comprehensive curriculum for internal medicine residents on primary care of patients identifying as lesbian, gay, bisexual, or transgender. MedEdPORTAL. 2020;16:10875.

- Zonana J, Batchelder S, Pula J, et al. Comment on: LGBT-specific education in general psychiatry residency programs: a survey of program directors. Acad Psychiatry. 2019;43:547-548.

- Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. ACGME Program Requirements for Graduate Medical Education in Dermatology. Revised June 12, 2022. Accessed September 23, 2022. https://www.acgme.org/globalassets/pfassets/programrequirements/080_dermatology_2022.pdf

- Jia JL, Nord KM, Sarin KY, et al. Sexual and gender minority curricula within US dermatology residency programs. JAMA Dermatol. 2020;156:593-594.

- Mansh M, White W, Gee-Tong L, et al. Sexual and gender minority identity disclosure during undergraduate medical education: “in the closet” in medical school. Acad Med. 2015;90:634-644.

- US Census Bureau. 2020 Census Informational Questionnaire. Accessed September 19, 2022. https://www2.census.gov/programs-surveys/decennial/2020/technical-documentation/questionnaires-and-instructions/questionnaires/2020-informational-questionnaire-english_DI-Q1.pdf

- Mohr JJ, Fassinger RE. Measuring dimensions of lesbian and gay male experience. Meas Eval Couns Dev. 2000;33:66-90.

- Association of American Medical Colleges. Medical School Graduation Questionnaire: 2020 All Schools Summary Report. Published July 2020. Accessed September 19, 2022. https://www.aamc.org/media/46851/download

- Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. Data Resource Book: Academic Year 2019-2020. Accessed September 19, 2022. https://www.acgme.org/globalassets/pfassets/publicationsbooks/2019-2020_acgme_databook_document.pdf

- Mohr JJ, Jackson SD, Sheets RL. Sexual orientation self-presentation among bisexual-identified women and men: patterns and predictors. Arch Sex Behav. 2017;46:1465-1479.

- Tatum AK. Workplace climate and job satisfaction: a test of social cognitive career theory (SCCT)’s workplace self-management model with sexual minority employees. Semantic Scholar. 2018. Accessed September 19, 2022. https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/Workplace-Climate-and-Job-Satisfaction%3A-A-Test-of-Tatum/5af75ab70acfb73c54e34b95597576d30e07df12

- Fakhoury JW, Daveluy S. Incorporating lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender training into a residency program. Dermatol Clin. 2020;38:285-292.

Approximately 4.5% of adults within the United States identify as members of the lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender (LGBT) community.1 This is an umbrella term inclusive of all individuals identifying as nonheterosexual or noncisgender. Although the LGBT community has increasingly become more recognized and accepted by society over time, health care disparities persist and have been well documented in the literature.2-4 Dermatologists have the potential to greatly impact LGBT health, as many health concerns in this population are cutaneous, such as sun-protection behaviors, side effects of gender-affirming hormone therapy and gender-affirming procedures, and cutaneous manifestations of sexually transmitted infections.5-7

An education gap has been demonstrated in both medical students and resident physicians regarding LGBT health and cultural competency. In a large-scale, multi-institutional survey study published in 2015, approximately two-thirds of medical students rated their schools’ LGBT curriculum as fair, poor, or very poor.8 Additional studies have echoed these results and have demonstrated not only the need but the desire for additional training on LGBT issues in medical school.9-11 The Association of American Medical Colleges has begun implementing curricular and institutional changes to fulfill this need.12,13

The LGBT education gap has been shown to extend into residency training. Multiple studies performed within a variety of medical specialties have demonstrated that resident physicians receive insufficient training in LGBT health issues, lack comfort in caring for LGBT patients, and would benefit from dedicated curricula on these topics.14-18 Currently, the 2022 Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) guidelines related to LGBT health are minimal and nonspecific.19

Ensuring that dermatology trainees are well equipped to manage these issues while providing culturally competent care to LGBT patients is paramount. However, research suggests that dedicated training on these topics likely is insufficient. A survey study of dermatology residency program directors (N=90) revealed that although 81% (72/89) viewed training in LGBT health as either very important or somewhat important, 46% (41/90) of programs did not dedicate any time to this content and 37% (33/90) only dedicated 1 to 2 hours per year.20

To further explore this potential education gap, we surveyed dermatology residents directly to better understand LGBT education within residency training, resident preparedness to care for LGBT patients, and outness/discrimination of LGBT-identifying residents. We believe this study should drive future research on the development and implementation of LGBT-specific curricula in dermatology training programs.

Methods

A cross-sectional survey study of dermatology residents in the United States was conducted. The study was deemed exempt from review by The Ohio State University (Columbus, Ohio) institutional review board. Survey responses were collected from October 7, 2020, to November 13, 2020. Qualtrics software was used to create the 20-question survey, which included a combination of categorical, dichotomous, and optional free-text questions related to patient demographics, LGBT training experiences, perceived areas of curriculum improvement, comfort level managing LGBT health issues, and personal experiences. Some questions were adapted from prior surveys.15,21 Validated survey tools used included the 2020 US Census to collect information regarding race and ethnicity, the Mohr and Fassinger Outness Inventory to measure outness regarding sexual orientation, and select questions from the 2020 Association of American Medical Colleges Medical School Graduation Questionnaire regarding discrimination.22-24

The survey was distributed to current allopathic and osteopathic dermatology residents by a variety of methods, including emails to program director and program coordinator listserves. The survey also was posted in the American Academy of Dermatology Expert Resource Group on LGBTQ Health October 2020 newsletter, as well as dermatology social media groups, including a messaging forum limited to dermatology residents, a Facebook group open to dermatologists and dermatology residents, and the Facebook group of the Gay and Lesbian Dermatology Association. Current dermatology residents, including those in combined dermatology and internal medicine programs, were included. Individuals who had been accepted to dermatology training programs but had not yet started were excluded. A follow-up email was sent to the program director listserve approximately 3 weeks after the initial distribution.

Statistical Analysis—The data were analyzed in Qualtrics and Microsoft Excel using descriptive statistics. Stata software (Stata 15.1, StataCorp) was used to perform a Kruskal-Wallis equality-of-populations rank test to compare the means of education level and feelings of preparedness.

Results

Demographics of Respondents—A total of 126 responses were recorded, 12 of which were blank and were removed from the database. A total of 114 dermatology residents’ responses were collected in Qualtrics and analyzed; 91 completed the entire survey (an 80% completion rate). Based on the 2020-2021 ACGME data listing, there were 1612 dermatology residents in the United States, which is an estimated response rate of 7% (114/1612).25 The eTable outlines the demographics of the survey respondents. Most were cisgender females (60%), followed by cisgender males (35%); the remainder preferred not to answer. Regarding sexual orientation, 77% identified as straight or heterosexual; 17% as gay, lesbian, or homosexual; 1% as queer; and 1% as bisexual. The training programs were in 26 states, the majority of which were in the Midwest (34%) and in urban settings (69%). A wide range of postgraduate levels and residency sizes were represented in the survey.

LGBT Education—Fifty-one percent of respondents reported that their programs offer 1 hour or less of LGBT-related curricula per year; 34% reported no time dedicated to this topic. A small portion of residents (5%) reported 10 or more hours of LGBT education per year. Residents also were asked the average number of hours of LGBT education they thought they should receive. The discrepancy between these measures can be visualized in Figure 1. The median hours of education received was 1 hour (IQR, 0–4 hours), whereas the median hours of education desired was 4 hours (IQR, 2–5 hours). The most common and most helpful methods of education reported were clinical experiences with faculty or patients and live lectures.

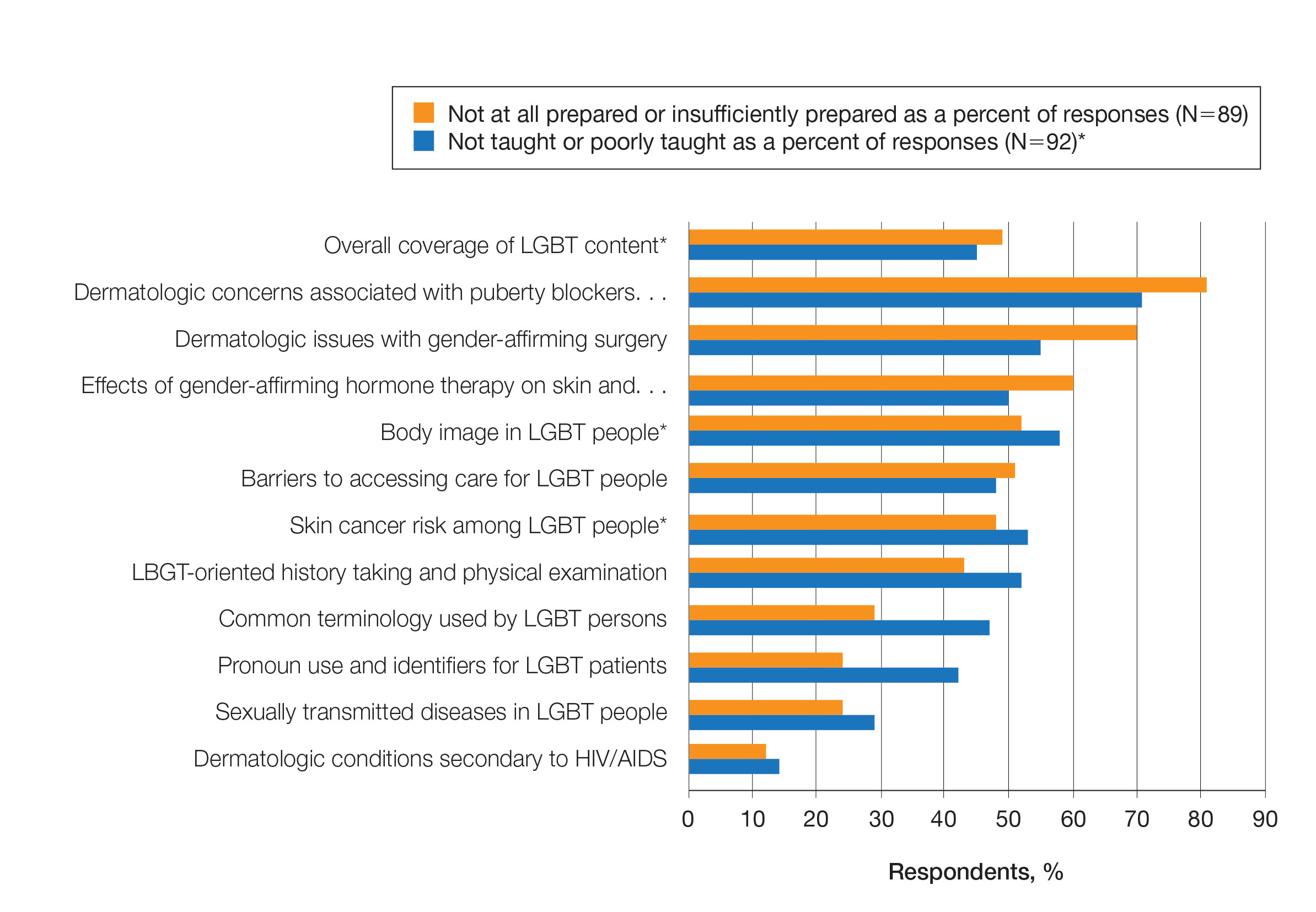

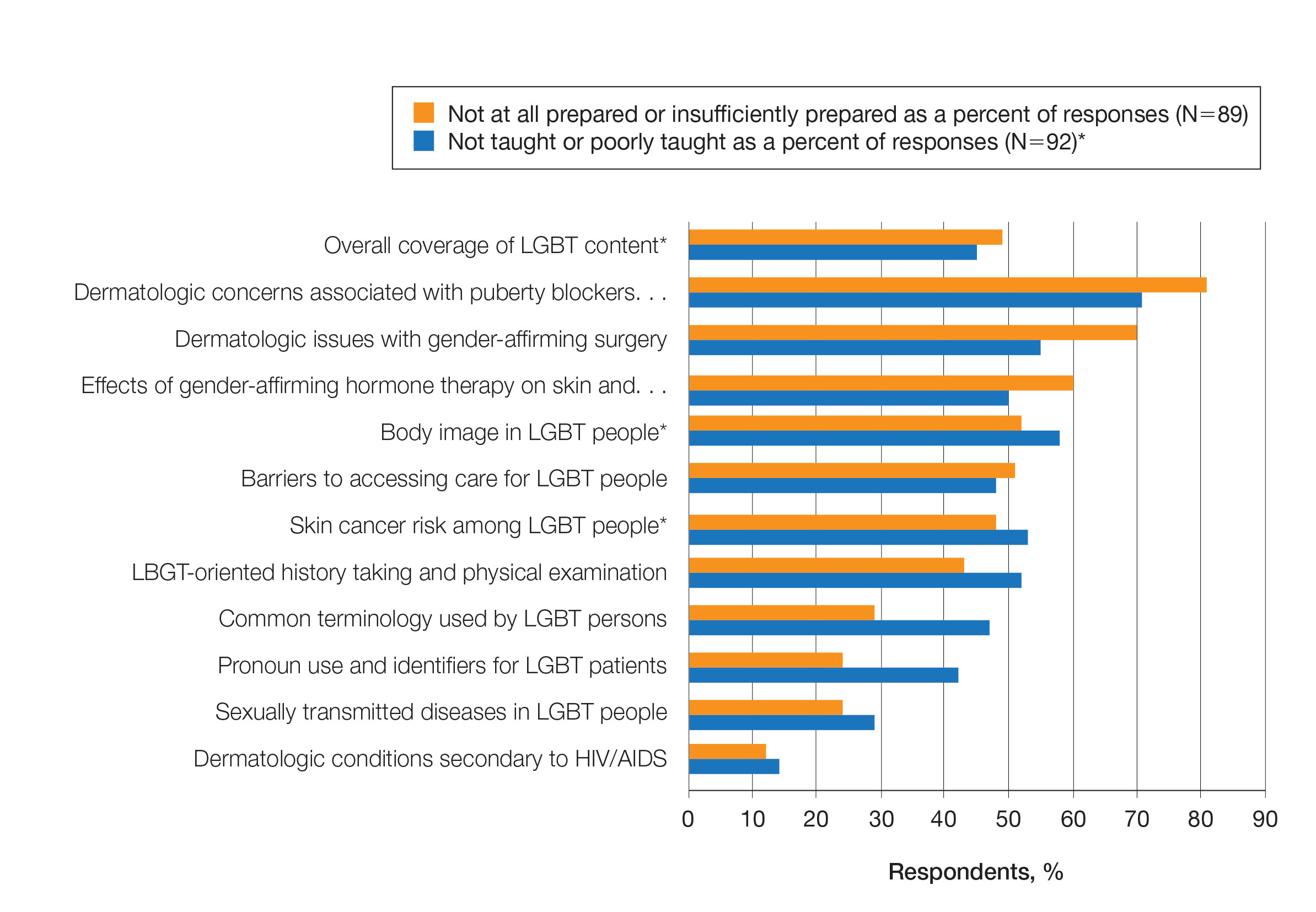

Overall, 45% of survey respondents felt that LGBT topics were covered poorly or not at all in dermatology residency, whereas 26% thought the coverage was good or excellent. The topics that residents were most likely to report receiving good or excellent coverage were dermatologic manifestations of HIV/AIDS (70%) and sexually transmitted diseases in LGBT patients (48%). The topics that were most likely to be reported as not taught or poorly taught included dermatologic concerns associated with puberty blockers (71%), body image (58%), dermatologic concerns associated with gender-affirming surgery (55%), skin cancer risk (53%), taking an LGBT-oriented history and physical examination (52%), and effects of gender-affirming hormone therapy on the skin (50%). A detailed breakdown of coverage level by topic can be found in Figure 2.

Preparedness to Care for LGBT Patients—Only 68% of survey respondents agreed or strongly agreed that they feel comfortable treating LGBT patients. Furthermore, 49% of dermatology residents reported that they feel not at all prepared or insufficiently prepared to provide care to LGBT individuals (Figure 2), and 60% believed that LGBT training needed to be improved at their residency programs.

There was a significant association between reported level of education and feelings of preparedness. A high ranking of provided education was associated with higher levels of feeling prepared to care for LGBT patients (Kruskal-Wallis rank test, P<.001).

Discrimination/Outness—Approximately one-fourth (24%; 4/17) of nonheterosexual dermatology residents reported that they had been subjected to offensive remarks about their sexual orientation in the workplace. One respondent commented that they were less “out” at their residency program due to fear of discrimination. Nearly one-third of the overall group of dermatology residents surveyed (29%; 27/92) reported that they had witnessed inappropriate or discriminatory comments about LGBT persons made by employees or staff at their programs. Most residents surveyed (96%; 88/92) agreed or strongly agreed that they feel comfortable working alongside LGBT physicians.

There were 18 nonheterosexual dermatologyresidents who completed the Mohr and Fassinger Outness Inventory.23 In general, respondents reported that they were more “out” with friends and family than work peers and were least “out” with work supervisors and strangers.

Comment

Dermatology Residents Desire More Time on LGBT Health—This cross-sectional survey study explored dermatology residents’ educational experiences with LGBT health during residency training. Similar studies have been performed in other specialties, including a study from 2019 surveying emergency medicine residents that demonstrated residents find caring for LGBT patients more challenging.15 Another 2019 study surveying psychiatry residents found that 42.4% (N=99) reported no coverage of LGBT topics.18 Our study is unique in that it surveyed dermatology residents directly regarding this topic. Although most dermatology program directors view LGBT dermatologic health as an important topic, a prior study revealed that many programs are lacking dedicated LGBT educational experiences. The most common barriers reported were insufficient time in the didactic schedule and lack of experienced faculty.20

Our study revealed that dermatology residents overall tend to agree with residents from other specialties and dermatology program directors. Most of the dermatology residents surveyed reported desiring more time per year spent on LGBT health education than they receive, and 60% expressed that LGBT educational experiences need to be improved at their residency programs. Education on and subsequent comfort level with LGBT health issues varied by subtopic, with most residents feeling comfortable dealing with dermatologic manifestations of HIV/AIDS and other sexually transmitted diseases and less comfortable with topics such as puberty blockers, gender-affirming surgery and hormone therapy, body image, and skin cancer risk.

Overall, LGBT health training is viewed as important and in need of improvement by both program directors and residents, yet implementation lags at many programs. A small proportion of the represented programs are excelling in this area—just over 5% of respondents reported receiving 10 or more hours of LGBT-relevant education per year, and approximately 26% of residents felt that LGBT coverage was good or excellent at their programs. Our study showed a clear relationship between feelings of preparedness and education level. The lack of LGBT education at some dermatology residency programs translated into a large portion of dermatology residents feeling ill equipped to care for LGBT patients after graduation—nearly 50% of those surveyed reported feeling insufficiently prepared to care for the LGBT community.

Discrimination in Residency Programs—Dermatology residency programs also are not free from sexual orientation–related and gender identity–related workplace discrimination. Although 96% of dermatology residents reported that they feel comfortable working alongside LGBT physicians, 24% of nonheterosexual respondents stated they had been subjected to offensive remarks about their sexual orientation, and 29% of the overall group of dermatology residents had witnessed discriminatory comments to LGBT individuals at their programs. In addition, some nonheterosexual dermatology residents reported being less “out” with their workplace supervisors and strangers, such as patients, than with their family and friends, and 50% of this group reported that their sexual identity was not openly discussed with their workplace supervisors. It has been demonstrated that individuals are more likely to “come out” in perceived LGBT-friendly workplace environments and that being “out” positively impacts psychological health because of the effects of perceived social support and self-coherence.26,27

Study Strengths and Limitations—Strengths of this study include the modest sample size of dermatology residents that participated, high completion rate, and the anonymity of the survey. Limitations include the risk of sampling bias by posting the survey on LGBT-specific groups. The survey also took place in the fall, so the results may not accurately reflect programs that cover this material later in the academic year. Lastly, not all survey questions were validated.

Implementing Change in Residency Programs—Although the results of this study exposed the need for increasing LGBT education in dermatology residency, they do not provide guidelines for the best strategy to begin implementing change. A study from 2020 provides some guidance for incorporating LGBT health training into dermatology residency programs through a combination of curricular modifications and climate optimization.28 Additional future research should focus on the best methods for preparing dermatology residents to care for this population. In this study, residents reported that the most effective teaching methods were real encounters with LGBT patients or faculty educated on LGBT health as well as live lectures from experts. There also appeared to be a correlation between hours spent on LGBT health, including various subtopics, and residents’ perceived preparedness in these areas. Potential actionable items include clarifying the ACGME guidelines on LGBT health topics; increasing the sexual and gender diversity of the faculty, staff, residents, and patients; and dedicating additional didactic and clinical time to LGBT topics and experiences.

Conclusion

This survey study of dermatology residents regarding LGBT learning experiences in residency training provided evidence that dermatology residents as a whole are not adequately taught LGBT health topics and therefore feel unprepared to take care of this patient population. Additionally, most residents desire improvement of LGBT health education and training. Further studies focusing on the best methods for implementing LGBT-specific curricula are needed.

Approximately 4.5% of adults within the United States identify as members of the lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender (LGBT) community.1 This is an umbrella term inclusive of all individuals identifying as nonheterosexual or noncisgender. Although the LGBT community has increasingly become more recognized and accepted by society over time, health care disparities persist and have been well documented in the literature.2-4 Dermatologists have the potential to greatly impact LGBT health, as many health concerns in this population are cutaneous, such as sun-protection behaviors, side effects of gender-affirming hormone therapy and gender-affirming procedures, and cutaneous manifestations of sexually transmitted infections.5-7

An education gap has been demonstrated in both medical students and resident physicians regarding LGBT health and cultural competency. In a large-scale, multi-institutional survey study published in 2015, approximately two-thirds of medical students rated their schools’ LGBT curriculum as fair, poor, or very poor.8 Additional studies have echoed these results and have demonstrated not only the need but the desire for additional training on LGBT issues in medical school.9-11 The Association of American Medical Colleges has begun implementing curricular and institutional changes to fulfill this need.12,13

The LGBT education gap has been shown to extend into residency training. Multiple studies performed within a variety of medical specialties have demonstrated that resident physicians receive insufficient training in LGBT health issues, lack comfort in caring for LGBT patients, and would benefit from dedicated curricula on these topics.14-18 Currently, the 2022 Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) guidelines related to LGBT health are minimal and nonspecific.19

Ensuring that dermatology trainees are well equipped to manage these issues while providing culturally competent care to LGBT patients is paramount. However, research suggests that dedicated training on these topics likely is insufficient. A survey study of dermatology residency program directors (N=90) revealed that although 81% (72/89) viewed training in LGBT health as either very important or somewhat important, 46% (41/90) of programs did not dedicate any time to this content and 37% (33/90) only dedicated 1 to 2 hours per year.20

To further explore this potential education gap, we surveyed dermatology residents directly to better understand LGBT education within residency training, resident preparedness to care for LGBT patients, and outness/discrimination of LGBT-identifying residents. We believe this study should drive future research on the development and implementation of LGBT-specific curricula in dermatology training programs.

Methods

A cross-sectional survey study of dermatology residents in the United States was conducted. The study was deemed exempt from review by The Ohio State University (Columbus, Ohio) institutional review board. Survey responses were collected from October 7, 2020, to November 13, 2020. Qualtrics software was used to create the 20-question survey, which included a combination of categorical, dichotomous, and optional free-text questions related to patient demographics, LGBT training experiences, perceived areas of curriculum improvement, comfort level managing LGBT health issues, and personal experiences. Some questions were adapted from prior surveys.15,21 Validated survey tools used included the 2020 US Census to collect information regarding race and ethnicity, the Mohr and Fassinger Outness Inventory to measure outness regarding sexual orientation, and select questions from the 2020 Association of American Medical Colleges Medical School Graduation Questionnaire regarding discrimination.22-24

The survey was distributed to current allopathic and osteopathic dermatology residents by a variety of methods, including emails to program director and program coordinator listserves. The survey also was posted in the American Academy of Dermatology Expert Resource Group on LGBTQ Health October 2020 newsletter, as well as dermatology social media groups, including a messaging forum limited to dermatology residents, a Facebook group open to dermatologists and dermatology residents, and the Facebook group of the Gay and Lesbian Dermatology Association. Current dermatology residents, including those in combined dermatology and internal medicine programs, were included. Individuals who had been accepted to dermatology training programs but had not yet started were excluded. A follow-up email was sent to the program director listserve approximately 3 weeks after the initial distribution.

Statistical Analysis—The data were analyzed in Qualtrics and Microsoft Excel using descriptive statistics. Stata software (Stata 15.1, StataCorp) was used to perform a Kruskal-Wallis equality-of-populations rank test to compare the means of education level and feelings of preparedness.

Results

Demographics of Respondents—A total of 126 responses were recorded, 12 of which were blank and were removed from the database. A total of 114 dermatology residents’ responses were collected in Qualtrics and analyzed; 91 completed the entire survey (an 80% completion rate). Based on the 2020-2021 ACGME data listing, there were 1612 dermatology residents in the United States, which is an estimated response rate of 7% (114/1612).25 The eTable outlines the demographics of the survey respondents. Most were cisgender females (60%), followed by cisgender males (35%); the remainder preferred not to answer. Regarding sexual orientation, 77% identified as straight or heterosexual; 17% as gay, lesbian, or homosexual; 1% as queer; and 1% as bisexual. The training programs were in 26 states, the majority of which were in the Midwest (34%) and in urban settings (69%). A wide range of postgraduate levels and residency sizes were represented in the survey.

LGBT Education—Fifty-one percent of respondents reported that their programs offer 1 hour or less of LGBT-related curricula per year; 34% reported no time dedicated to this topic. A small portion of residents (5%) reported 10 or more hours of LGBT education per year. Residents also were asked the average number of hours of LGBT education they thought they should receive. The discrepancy between these measures can be visualized in Figure 1. The median hours of education received was 1 hour (IQR, 0–4 hours), whereas the median hours of education desired was 4 hours (IQR, 2–5 hours). The most common and most helpful methods of education reported were clinical experiences with faculty or patients and live lectures.

Overall, 45% of survey respondents felt that LGBT topics were covered poorly or not at all in dermatology residency, whereas 26% thought the coverage was good or excellent. The topics that residents were most likely to report receiving good or excellent coverage were dermatologic manifestations of HIV/AIDS (70%) and sexually transmitted diseases in LGBT patients (48%). The topics that were most likely to be reported as not taught or poorly taught included dermatologic concerns associated with puberty blockers (71%), body image (58%), dermatologic concerns associated with gender-affirming surgery (55%), skin cancer risk (53%), taking an LGBT-oriented history and physical examination (52%), and effects of gender-affirming hormone therapy on the skin (50%). A detailed breakdown of coverage level by topic can be found in Figure 2.

Preparedness to Care for LGBT Patients—Only 68% of survey respondents agreed or strongly agreed that they feel comfortable treating LGBT patients. Furthermore, 49% of dermatology residents reported that they feel not at all prepared or insufficiently prepared to provide care to LGBT individuals (Figure 2), and 60% believed that LGBT training needed to be improved at their residency programs.

There was a significant association between reported level of education and feelings of preparedness. A high ranking of provided education was associated with higher levels of feeling prepared to care for LGBT patients (Kruskal-Wallis rank test, P<.001).

Discrimination/Outness—Approximately one-fourth (24%; 4/17) of nonheterosexual dermatology residents reported that they had been subjected to offensive remarks about their sexual orientation in the workplace. One respondent commented that they were less “out” at their residency program due to fear of discrimination. Nearly one-third of the overall group of dermatology residents surveyed (29%; 27/92) reported that they had witnessed inappropriate or discriminatory comments about LGBT persons made by employees or staff at their programs. Most residents surveyed (96%; 88/92) agreed or strongly agreed that they feel comfortable working alongside LGBT physicians.

There were 18 nonheterosexual dermatologyresidents who completed the Mohr and Fassinger Outness Inventory.23 In general, respondents reported that they were more “out” with friends and family than work peers and were least “out” with work supervisors and strangers.

Comment

Dermatology Residents Desire More Time on LGBT Health—This cross-sectional survey study explored dermatology residents’ educational experiences with LGBT health during residency training. Similar studies have been performed in other specialties, including a study from 2019 surveying emergency medicine residents that demonstrated residents find caring for LGBT patients more challenging.15 Another 2019 study surveying psychiatry residents found that 42.4% (N=99) reported no coverage of LGBT topics.18 Our study is unique in that it surveyed dermatology residents directly regarding this topic. Although most dermatology program directors view LGBT dermatologic health as an important topic, a prior study revealed that many programs are lacking dedicated LGBT educational experiences. The most common barriers reported were insufficient time in the didactic schedule and lack of experienced faculty.20

Our study revealed that dermatology residents overall tend to agree with residents from other specialties and dermatology program directors. Most of the dermatology residents surveyed reported desiring more time per year spent on LGBT health education than they receive, and 60% expressed that LGBT educational experiences need to be improved at their residency programs. Education on and subsequent comfort level with LGBT health issues varied by subtopic, with most residents feeling comfortable dealing with dermatologic manifestations of HIV/AIDS and other sexually transmitted diseases and less comfortable with topics such as puberty blockers, gender-affirming surgery and hormone therapy, body image, and skin cancer risk.

Overall, LGBT health training is viewed as important and in need of improvement by both program directors and residents, yet implementation lags at many programs. A small proportion of the represented programs are excelling in this area—just over 5% of respondents reported receiving 10 or more hours of LGBT-relevant education per year, and approximately 26% of residents felt that LGBT coverage was good or excellent at their programs. Our study showed a clear relationship between feelings of preparedness and education level. The lack of LGBT education at some dermatology residency programs translated into a large portion of dermatology residents feeling ill equipped to care for LGBT patients after graduation—nearly 50% of those surveyed reported feeling insufficiently prepared to care for the LGBT community.

Discrimination in Residency Programs—Dermatology residency programs also are not free from sexual orientation–related and gender identity–related workplace discrimination. Although 96% of dermatology residents reported that they feel comfortable working alongside LGBT physicians, 24% of nonheterosexual respondents stated they had been subjected to offensive remarks about their sexual orientation, and 29% of the overall group of dermatology residents had witnessed discriminatory comments to LGBT individuals at their programs. In addition, some nonheterosexual dermatology residents reported being less “out” with their workplace supervisors and strangers, such as patients, than with their family and friends, and 50% of this group reported that their sexual identity was not openly discussed with their workplace supervisors. It has been demonstrated that individuals are more likely to “come out” in perceived LGBT-friendly workplace environments and that being “out” positively impacts psychological health because of the effects of perceived social support and self-coherence.26,27

Study Strengths and Limitations—Strengths of this study include the modest sample size of dermatology residents that participated, high completion rate, and the anonymity of the survey. Limitations include the risk of sampling bias by posting the survey on LGBT-specific groups. The survey also took place in the fall, so the results may not accurately reflect programs that cover this material later in the academic year. Lastly, not all survey questions were validated.

Implementing Change in Residency Programs—Although the results of this study exposed the need for increasing LGBT education in dermatology residency, they do not provide guidelines for the best strategy to begin implementing change. A study from 2020 provides some guidance for incorporating LGBT health training into dermatology residency programs through a combination of curricular modifications and climate optimization.28 Additional future research should focus on the best methods for preparing dermatology residents to care for this population. In this study, residents reported that the most effective teaching methods were real encounters with LGBT patients or faculty educated on LGBT health as well as live lectures from experts. There also appeared to be a correlation between hours spent on LGBT health, including various subtopics, and residents’ perceived preparedness in these areas. Potential actionable items include clarifying the ACGME guidelines on LGBT health topics; increasing the sexual and gender diversity of the faculty, staff, residents, and patients; and dedicating additional didactic and clinical time to LGBT topics and experiences.

Conclusion

This survey study of dermatology residents regarding LGBT learning experiences in residency training provided evidence that dermatology residents as a whole are not adequately taught LGBT health topics and therefore feel unprepared to take care of this patient population. Additionally, most residents desire improvement of LGBT health education and training. Further studies focusing on the best methods for implementing LGBT-specific curricula are needed.

- Newport F. In U.S., estimate of LGBT population rises to 4.5%. Gallup. May 22, 2018. Accessed September 19, 2022. https://news.gallup.com/poll/234863/estimate-lgbt-population-rises.aspx

- Hafeez H, Zeshan M, Tahir MA, et al. Health care disparities among lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender youth: a literature review. Cureus. 2017;9:E1184.

- Gonzales G, Henning-Smith C. Barriers to care among transgender and gender nonconforming adults. Millbank Q. 2017;95:726-748.

- Quinn GP, Sanchez JA, Sutton SK, et al. Cancer and lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender/transsexual, and queer/questioning (LGBTQ) populations. CA Cancer J Clin. 2015;65:384-400.

- Sullivan P, Trinidad J, Hamann D. Issues in transgender dermatology: a systematic review of the literature. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;81:438-447.

- Yeung H, Luk KM, Chen SC, et al. Dermatologic care for lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender persons: epidemiology, screening, and disease prevention. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80:591-602.

- Yeung H, Luk KM, Chen SC, et al. Dermatologic care for lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender persons: terminology, demographics, health disparities, and approaches to care. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80:581-589.

- White W, Brenman S, Paradis E, et al. Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender patient care: medical students’ preparedness and comfort. Teach Learn Med. 2015;27:254-263.

- Nama N, MacPherson P, Sampson M, et al. Medical students’ perception of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) discrimination in their learning environment and their self-reported comfort level for caring for LGBT patients: a survey study. Med Educ Online. 2017;22:1-8.

- Phelan SM, Burke SE, Hardeman RR, et al. Medical school factors associated with changes in implicit and explicit bias against gay and lesbian people among 3492 graduating medical students. J Gen Intern Med. 2017;32:1193-1201.

- Cherabie J, Nilsen K, Houssayni S. Transgender health medical education intervention and its effects on beliefs, attitudes, comfort, and knowledge. Kans J Med. 2018;11:106-109.

- Integrating LGBT and DSD content into medical school curricula. Association of American Medical Colleges website. Published November 2015. Accessed September 23, 2022. https://www.aamc.org/what-we-do/equity-diversity-inclusion/lgbt-health-resources/videos/curricula-integration

- Cooper MB, Chacko M, Christner J. Incorporating LGBT health in an undergraduate medical education curriculum through the construct of social determinants of health. MedEdPORTAL. 2018;14:10781.

- Moll J, Krieger P, Moreno-Walton L, et al. The prevalence of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender health education and training in emergency medicine residency programs: what do we know? Acad Emerg Med. 2014;21:608-611.

- Moll J, Krieger P, Heron SL, et al. Attitudes, behavior, and comfort of emergency medicine residents in caring for LGBT patients: what do we know? AEM Educ Train. 2019;3:129-135.

- Hirschtritt ME, Noy G, Haller E, et al. LGBT-specific education in general psychiatry residency programs: a survey of program directors. Acad Psychiatry. 2019;43:41-45.

- Ufomata E, Eckstrand KL, Spagnoletti C, et al. Comprehensive curriculum for internal medicine residents on primary care of patients identifying as lesbian, gay, bisexual, or transgender. MedEdPORTAL. 2020;16:10875.

- Zonana J, Batchelder S, Pula J, et al. Comment on: LGBT-specific education in general psychiatry residency programs: a survey of program directors. Acad Psychiatry. 2019;43:547-548.

- Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. ACGME Program Requirements for Graduate Medical Education in Dermatology. Revised June 12, 2022. Accessed September 23, 2022. https://www.acgme.org/globalassets/pfassets/programrequirements/080_dermatology_2022.pdf

- Jia JL, Nord KM, Sarin KY, et al. Sexual and gender minority curricula within US dermatology residency programs. JAMA Dermatol. 2020;156:593-594.

- Mansh M, White W, Gee-Tong L, et al. Sexual and gender minority identity disclosure during undergraduate medical education: “in the closet” in medical school. Acad Med. 2015;90:634-644.

- US Census Bureau. 2020 Census Informational Questionnaire. Accessed September 19, 2022. https://www2.census.gov/programs-surveys/decennial/2020/technical-documentation/questionnaires-and-instructions/questionnaires/2020-informational-questionnaire-english_DI-Q1.pdf

- Mohr JJ, Fassinger RE. Measuring dimensions of lesbian and gay male experience. Meas Eval Couns Dev. 2000;33:66-90.

- Association of American Medical Colleges. Medical School Graduation Questionnaire: 2020 All Schools Summary Report. Published July 2020. Accessed September 19, 2022. https://www.aamc.org/media/46851/download

- Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. Data Resource Book: Academic Year 2019-2020. Accessed September 19, 2022. https://www.acgme.org/globalassets/pfassets/publicationsbooks/2019-2020_acgme_databook_document.pdf

- Mohr JJ, Jackson SD, Sheets RL. Sexual orientation self-presentation among bisexual-identified women and men: patterns and predictors. Arch Sex Behav. 2017;46:1465-1479.

- Tatum AK. Workplace climate and job satisfaction: a test of social cognitive career theory (SCCT)’s workplace self-management model with sexual minority employees. Semantic Scholar. 2018. Accessed September 19, 2022. https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/Workplace-Climate-and-Job-Satisfaction%3A-A-Test-of-Tatum/5af75ab70acfb73c54e34b95597576d30e07df12

- Fakhoury JW, Daveluy S. Incorporating lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender training into a residency program. Dermatol Clin. 2020;38:285-292.

- Newport F. In U.S., estimate of LGBT population rises to 4.5%. Gallup. May 22, 2018. Accessed September 19, 2022. https://news.gallup.com/poll/234863/estimate-lgbt-population-rises.aspx

- Hafeez H, Zeshan M, Tahir MA, et al. Health care disparities among lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender youth: a literature review. Cureus. 2017;9:E1184.

- Gonzales G, Henning-Smith C. Barriers to care among transgender and gender nonconforming adults. Millbank Q. 2017;95:726-748.

- Quinn GP, Sanchez JA, Sutton SK, et al. Cancer and lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender/transsexual, and queer/questioning (LGBTQ) populations. CA Cancer J Clin. 2015;65:384-400.

- Sullivan P, Trinidad J, Hamann D. Issues in transgender dermatology: a systematic review of the literature. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;81:438-447.

- Yeung H, Luk KM, Chen SC, et al. Dermatologic care for lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender persons: epidemiology, screening, and disease prevention. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80:591-602.

- Yeung H, Luk KM, Chen SC, et al. Dermatologic care for lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender persons: terminology, demographics, health disparities, and approaches to care. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80:581-589.

- White W, Brenman S, Paradis E, et al. Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender patient care: medical students’ preparedness and comfort. Teach Learn Med. 2015;27:254-263.

- Nama N, MacPherson P, Sampson M, et al. Medical students’ perception of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) discrimination in their learning environment and their self-reported comfort level for caring for LGBT patients: a survey study. Med Educ Online. 2017;22:1-8.

- Phelan SM, Burke SE, Hardeman RR, et al. Medical school factors associated with changes in implicit and explicit bias against gay and lesbian people among 3492 graduating medical students. J Gen Intern Med. 2017;32:1193-1201.

- Cherabie J, Nilsen K, Houssayni S. Transgender health medical education intervention and its effects on beliefs, attitudes, comfort, and knowledge. Kans J Med. 2018;11:106-109.

- Integrating LGBT and DSD content into medical school curricula. Association of American Medical Colleges website. Published November 2015. Accessed September 23, 2022. https://www.aamc.org/what-we-do/equity-diversity-inclusion/lgbt-health-resources/videos/curricula-integration

- Cooper MB, Chacko M, Christner J. Incorporating LGBT health in an undergraduate medical education curriculum through the construct of social determinants of health. MedEdPORTAL. 2018;14:10781.

- Moll J, Krieger P, Moreno-Walton L, et al. The prevalence of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender health education and training in emergency medicine residency programs: what do we know? Acad Emerg Med. 2014;21:608-611.

- Moll J, Krieger P, Heron SL, et al. Attitudes, behavior, and comfort of emergency medicine residents in caring for LGBT patients: what do we know? AEM Educ Train. 2019;3:129-135.

- Hirschtritt ME, Noy G, Haller E, et al. LGBT-specific education in general psychiatry residency programs: a survey of program directors. Acad Psychiatry. 2019;43:41-45.

- Ufomata E, Eckstrand KL, Spagnoletti C, et al. Comprehensive curriculum for internal medicine residents on primary care of patients identifying as lesbian, gay, bisexual, or transgender. MedEdPORTAL. 2020;16:10875.

- Zonana J, Batchelder S, Pula J, et al. Comment on: LGBT-specific education in general psychiatry residency programs: a survey of program directors. Acad Psychiatry. 2019;43:547-548.

- Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. ACGME Program Requirements for Graduate Medical Education in Dermatology. Revised June 12, 2022. Accessed September 23, 2022. https://www.acgme.org/globalassets/pfassets/programrequirements/080_dermatology_2022.pdf

- Jia JL, Nord KM, Sarin KY, et al. Sexual and gender minority curricula within US dermatology residency programs. JAMA Dermatol. 2020;156:593-594.

- Mansh M, White W, Gee-Tong L, et al. Sexual and gender minority identity disclosure during undergraduate medical education: “in the closet” in medical school. Acad Med. 2015;90:634-644.

- US Census Bureau. 2020 Census Informational Questionnaire. Accessed September 19, 2022. https://www2.census.gov/programs-surveys/decennial/2020/technical-documentation/questionnaires-and-instructions/questionnaires/2020-informational-questionnaire-english_DI-Q1.pdf

- Mohr JJ, Fassinger RE. Measuring dimensions of lesbian and gay male experience. Meas Eval Couns Dev. 2000;33:66-90.

- Association of American Medical Colleges. Medical School Graduation Questionnaire: 2020 All Schools Summary Report. Published July 2020. Accessed September 19, 2022. https://www.aamc.org/media/46851/download

- Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. Data Resource Book: Academic Year 2019-2020. Accessed September 19, 2022. https://www.acgme.org/globalassets/pfassets/publicationsbooks/2019-2020_acgme_databook_document.pdf

- Mohr JJ, Jackson SD, Sheets RL. Sexual orientation self-presentation among bisexual-identified women and men: patterns and predictors. Arch Sex Behav. 2017;46:1465-1479.

- Tatum AK. Workplace climate and job satisfaction: a test of social cognitive career theory (SCCT)’s workplace self-management model with sexual minority employees. Semantic Scholar. 2018. Accessed September 19, 2022. https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/Workplace-Climate-and-Job-Satisfaction%3A-A-Test-of-Tatum/5af75ab70acfb73c54e34b95597576d30e07df12

- Fakhoury JW, Daveluy S. Incorporating lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender training into a residency program. Dermatol Clin. 2020;38:285-292.

Practice Points

- Dermatologists have the potential to greatly impact lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender (LGBT) health since many health concerns in this population are cutaneous.

- Improving LGBT health education and training in dermatology residency likely will increase dermatology residents' comfort level in treating this population.

Highlights in Advanced Non–Small Cell Lung Cancer From ESMO 2022

Highlights in advanced non–small lung cancer (NSCLC) from the 2022 European Society for Medical Oncology Congress are presented by Dr Jack West of City of Hope Comprehensive Cancer Center in Duarte, California.

Dr West begins by discussing CodeBreak 200, a study comparing sotorasib with docetaxel in previously treated patients with a KRAS G12C mutation. Sotorasib improved progression-free survival, but overall survival data are awaited.

Next, Dr West examines 5-year updates from KEYNOTE-189 and KEYNOTE-407, comparing pembrolizumab with chemotherapy in nonsquamous and squamous disease, respectively. Around two fifths of patients remained alive and disease-free 5 years after stopping treatment.

Dr West then reports on the IPSOS trial, which compared atezolizumab with single-agent chemotherapy in patients who were ineligible for standard chemotherapy. The results suggested that immunotherapy could be used in patients who are usually excluded from trials.

He finishes with two studies in EGFR-mutated disease. ORIENT-3 indicated that the effect of sintilimab could be boosted with a bevacizumab biosimilar. INSIGHT 2 suggested that adding tepotinib to osimertinib may be effective in patients with MET amplification.

--

Associate Professor, Department of Medical Oncology, City of Hope Comprehensive Cancer Care, Duarte, California; Medical Director, AccessHope, Los Angeles, California

Howard (Jack) West, MD, has disclosed the following relevant financial relationships:

Serve(d) as a director, officer, partner, employee, advisor, consultant, or trustee for: Amgen; AstraZeneca; Eli Lilly; EQRx; Genentech/Roche; Merck; Mirati; Pfizer; Regeneron; Takeda

Serve(d) as a speaker or a member of a speakers bureau for: AstraZeneca; Merck

Highlights in advanced non–small lung cancer (NSCLC) from the 2022 European Society for Medical Oncology Congress are presented by Dr Jack West of City of Hope Comprehensive Cancer Center in Duarte, California.

Dr West begins by discussing CodeBreak 200, a study comparing sotorasib with docetaxel in previously treated patients with a KRAS G12C mutation. Sotorasib improved progression-free survival, but overall survival data are awaited.

Next, Dr West examines 5-year updates from KEYNOTE-189 and KEYNOTE-407, comparing pembrolizumab with chemotherapy in nonsquamous and squamous disease, respectively. Around two fifths of patients remained alive and disease-free 5 years after stopping treatment.

Dr West then reports on the IPSOS trial, which compared atezolizumab with single-agent chemotherapy in patients who were ineligible for standard chemotherapy. The results suggested that immunotherapy could be used in patients who are usually excluded from trials.

He finishes with two studies in EGFR-mutated disease. ORIENT-3 indicated that the effect of sintilimab could be boosted with a bevacizumab biosimilar. INSIGHT 2 suggested that adding tepotinib to osimertinib may be effective in patients with MET amplification.

--

Associate Professor, Department of Medical Oncology, City of Hope Comprehensive Cancer Care, Duarte, California; Medical Director, AccessHope, Los Angeles, California

Howard (Jack) West, MD, has disclosed the following relevant financial relationships:

Serve(d) as a director, officer, partner, employee, advisor, consultant, or trustee for: Amgen; AstraZeneca; Eli Lilly; EQRx; Genentech/Roche; Merck; Mirati; Pfizer; Regeneron; Takeda

Serve(d) as a speaker or a member of a speakers bureau for: AstraZeneca; Merck

Highlights in advanced non–small lung cancer (NSCLC) from the 2022 European Society for Medical Oncology Congress are presented by Dr Jack West of City of Hope Comprehensive Cancer Center in Duarte, California.

Dr West begins by discussing CodeBreak 200, a study comparing sotorasib with docetaxel in previously treated patients with a KRAS G12C mutation. Sotorasib improved progression-free survival, but overall survival data are awaited.

Next, Dr West examines 5-year updates from KEYNOTE-189 and KEYNOTE-407, comparing pembrolizumab with chemotherapy in nonsquamous and squamous disease, respectively. Around two fifths of patients remained alive and disease-free 5 years after stopping treatment.

Dr West then reports on the IPSOS trial, which compared atezolizumab with single-agent chemotherapy in patients who were ineligible for standard chemotherapy. The results suggested that immunotherapy could be used in patients who are usually excluded from trials.

He finishes with two studies in EGFR-mutated disease. ORIENT-3 indicated that the effect of sintilimab could be boosted with a bevacizumab biosimilar. INSIGHT 2 suggested that adding tepotinib to osimertinib may be effective in patients with MET amplification.

--

Associate Professor, Department of Medical Oncology, City of Hope Comprehensive Cancer Care, Duarte, California; Medical Director, AccessHope, Los Angeles, California

Howard (Jack) West, MD, has disclosed the following relevant financial relationships:

Serve(d) as a director, officer, partner, employee, advisor, consultant, or trustee for: Amgen; AstraZeneca; Eli Lilly; EQRx; Genentech/Roche; Merck; Mirati; Pfizer; Regeneron; Takeda

Serve(d) as a speaker or a member of a speakers bureau for: AstraZeneca; Merck

Key Data on Early Non–Small Cell Lung Cancer From ESMO 2022

Dr Jack West of City of Hope Comprehensive Cancer Center in Duarte, California, discusses key presentations on early-stage non–small lung cancer (NSCLC) from the 2022 European Society for Medical Oncology Congress.

He begins by reporting on 2 years of additional follow-up from the ADAURA trial, which looked at osimertinib as adjuvant therapy in patients with resected EGFR-mutated disease. The results raise the question of whether the drug needs to be given indefinitely.

Next, he discusses an analysis of data from the ADAURA trial that looked at longitudinal monitoring of circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA) levels. This revealed that both baseline ctDNA and ctDNA clearance were predictive of later recurrence.

Dr West moves on to a large global study that demonstrated a clear link between air pollution and lung cancer. Pollution was shown to be a tumor promoter of rare driver mutations in normal lung tissue.

After discussing disappointing data from CANOPY-A indicating that adjuvant canakinumab does not improve survival outcomes, he closes with an examination of the PATHFINDER study. This involved more than 6600 patients who were screened for cancer after a single blood test. Although the study identified cancer in 1.4% of participants, the low positive predictive value raises questions over the wider application of this test.

--

Associate Professor, Department of Medical Oncology, City of Hope Comprehensive Cancer Care, Duarte, California; Medical Director, AccessHope, Los Angeles, California

Howard (Jack) West, MD, has disclosed the following relevant financial relationships:

Serve(d) as a director, officer, partner, employee, advisor, consultant, or trustee for: Amgen; AstraZeneca; Eli Lilly; EQRx; Genentech/Roche; Merck; Mirati; Pfizer; Regeneron; Takeda

Serve(d) as a speaker or a member of a speakers bureau for: AstraZeneca; Merck

Dr Jack West of City of Hope Comprehensive Cancer Center in Duarte, California, discusses key presentations on early-stage non–small lung cancer (NSCLC) from the 2022 European Society for Medical Oncology Congress.

He begins by reporting on 2 years of additional follow-up from the ADAURA trial, which looked at osimertinib as adjuvant therapy in patients with resected EGFR-mutated disease. The results raise the question of whether the drug needs to be given indefinitely.

Next, he discusses an analysis of data from the ADAURA trial that looked at longitudinal monitoring of circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA) levels. This revealed that both baseline ctDNA and ctDNA clearance were predictive of later recurrence.

Dr West moves on to a large global study that demonstrated a clear link between air pollution and lung cancer. Pollution was shown to be a tumor promoter of rare driver mutations in normal lung tissue.

After discussing disappointing data from CANOPY-A indicating that adjuvant canakinumab does not improve survival outcomes, he closes with an examination of the PATHFINDER study. This involved more than 6600 patients who were screened for cancer after a single blood test. Although the study identified cancer in 1.4% of participants, the low positive predictive value raises questions over the wider application of this test.

--

Associate Professor, Department of Medical Oncology, City of Hope Comprehensive Cancer Care, Duarte, California; Medical Director, AccessHope, Los Angeles, California

Howard (Jack) West, MD, has disclosed the following relevant financial relationships:

Serve(d) as a director, officer, partner, employee, advisor, consultant, or trustee for: Amgen; AstraZeneca; Eli Lilly; EQRx; Genentech/Roche; Merck; Mirati; Pfizer; Regeneron; Takeda

Serve(d) as a speaker or a member of a speakers bureau for: AstraZeneca; Merck

Dr Jack West of City of Hope Comprehensive Cancer Center in Duarte, California, discusses key presentations on early-stage non–small lung cancer (NSCLC) from the 2022 European Society for Medical Oncology Congress.

He begins by reporting on 2 years of additional follow-up from the ADAURA trial, which looked at osimertinib as adjuvant therapy in patients with resected EGFR-mutated disease. The results raise the question of whether the drug needs to be given indefinitely.

Next, he discusses an analysis of data from the ADAURA trial that looked at longitudinal monitoring of circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA) levels. This revealed that both baseline ctDNA and ctDNA clearance were predictive of later recurrence.

Dr West moves on to a large global study that demonstrated a clear link between air pollution and lung cancer. Pollution was shown to be a tumor promoter of rare driver mutations in normal lung tissue.

After discussing disappointing data from CANOPY-A indicating that adjuvant canakinumab does not improve survival outcomes, he closes with an examination of the PATHFINDER study. This involved more than 6600 patients who were screened for cancer after a single blood test. Although the study identified cancer in 1.4% of participants, the low positive predictive value raises questions over the wider application of this test.

--

Associate Professor, Department of Medical Oncology, City of Hope Comprehensive Cancer Care, Duarte, California; Medical Director, AccessHope, Los Angeles, California

Howard (Jack) West, MD, has disclosed the following relevant financial relationships:

Serve(d) as a director, officer, partner, employee, advisor, consultant, or trustee for: Amgen; AstraZeneca; Eli Lilly; EQRx; Genentech/Roche; Merck; Mirati; Pfizer; Regeneron; Takeda

Serve(d) as a speaker or a member of a speakers bureau for: AstraZeneca; Merck

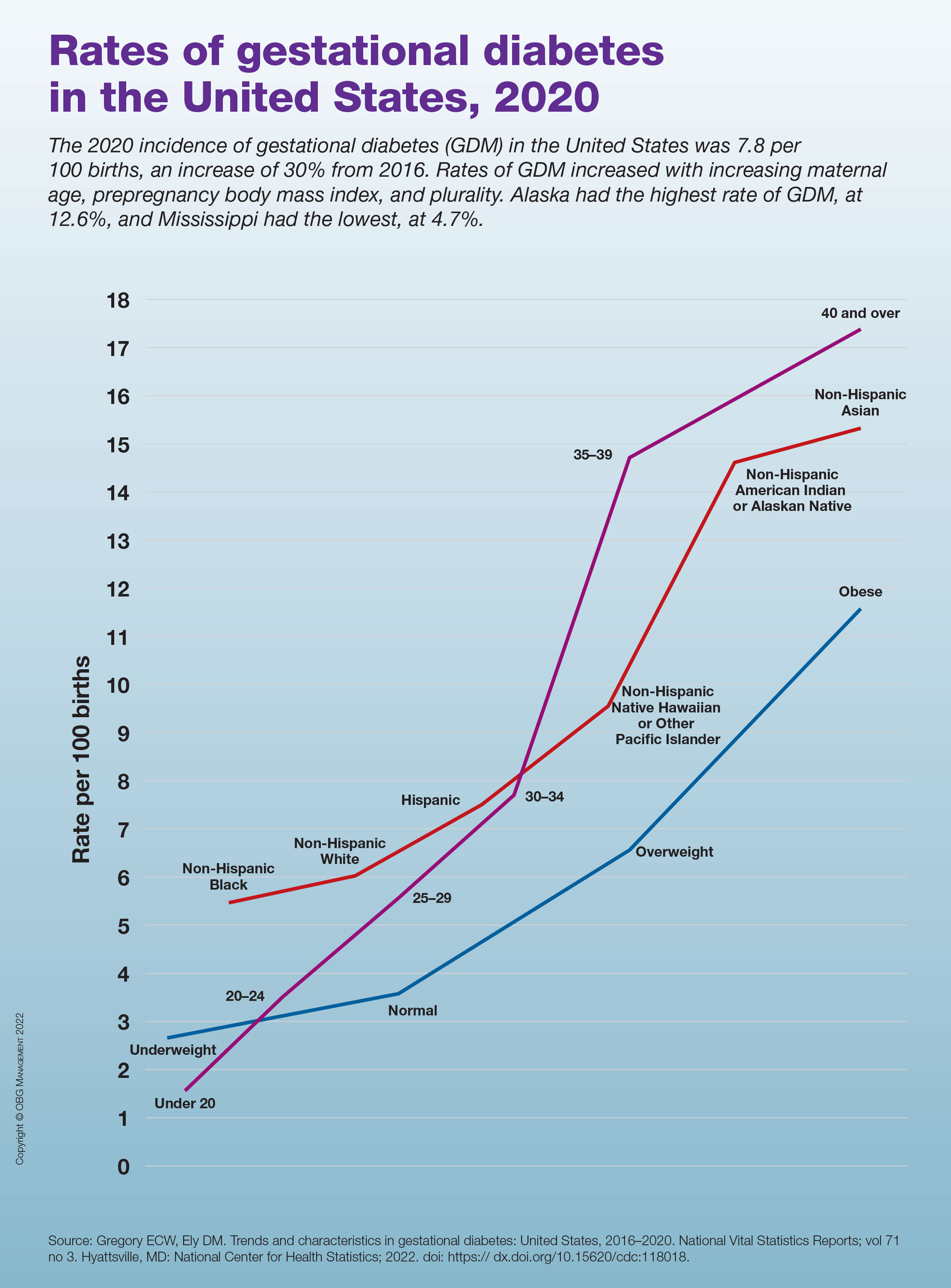

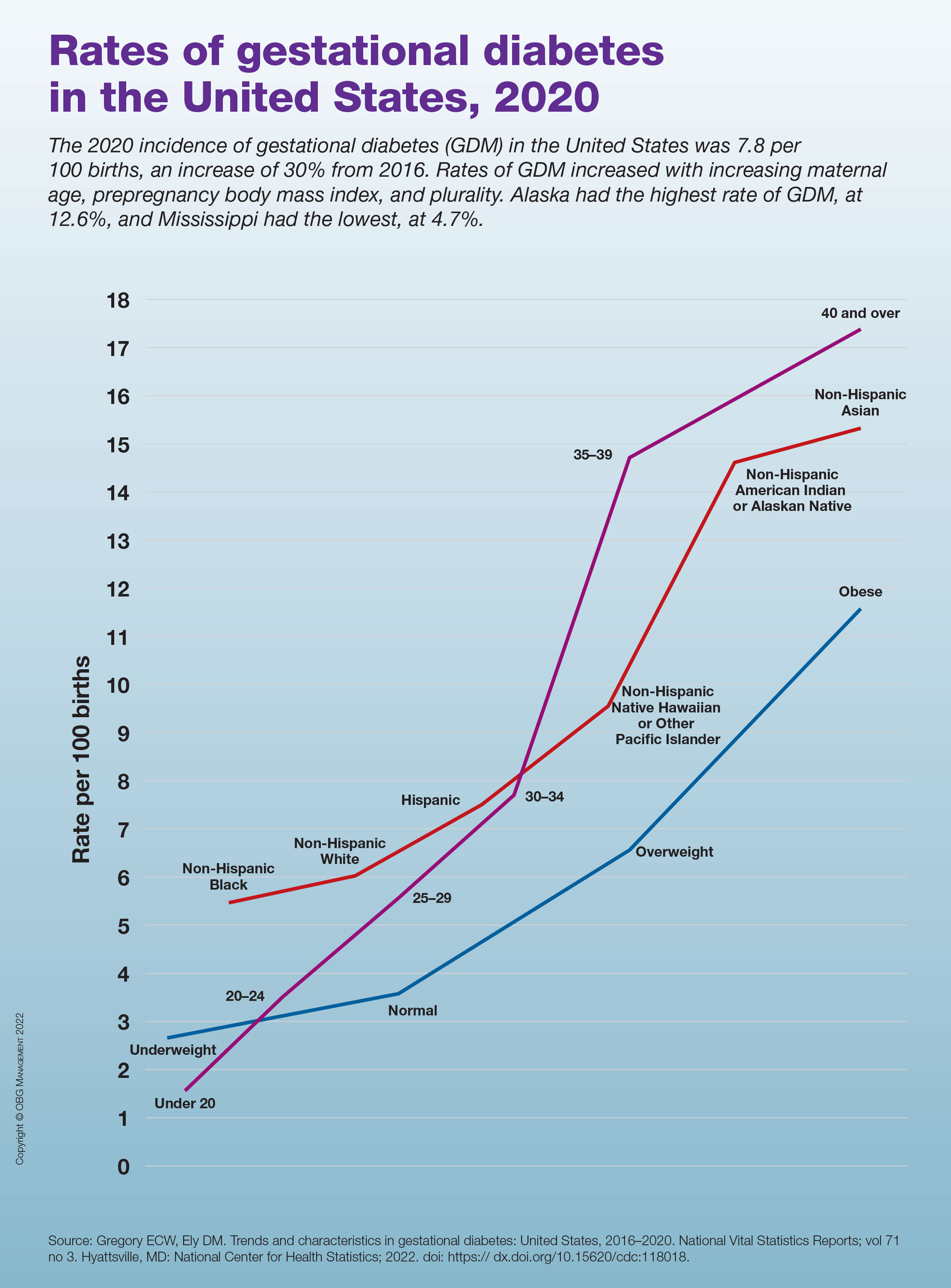

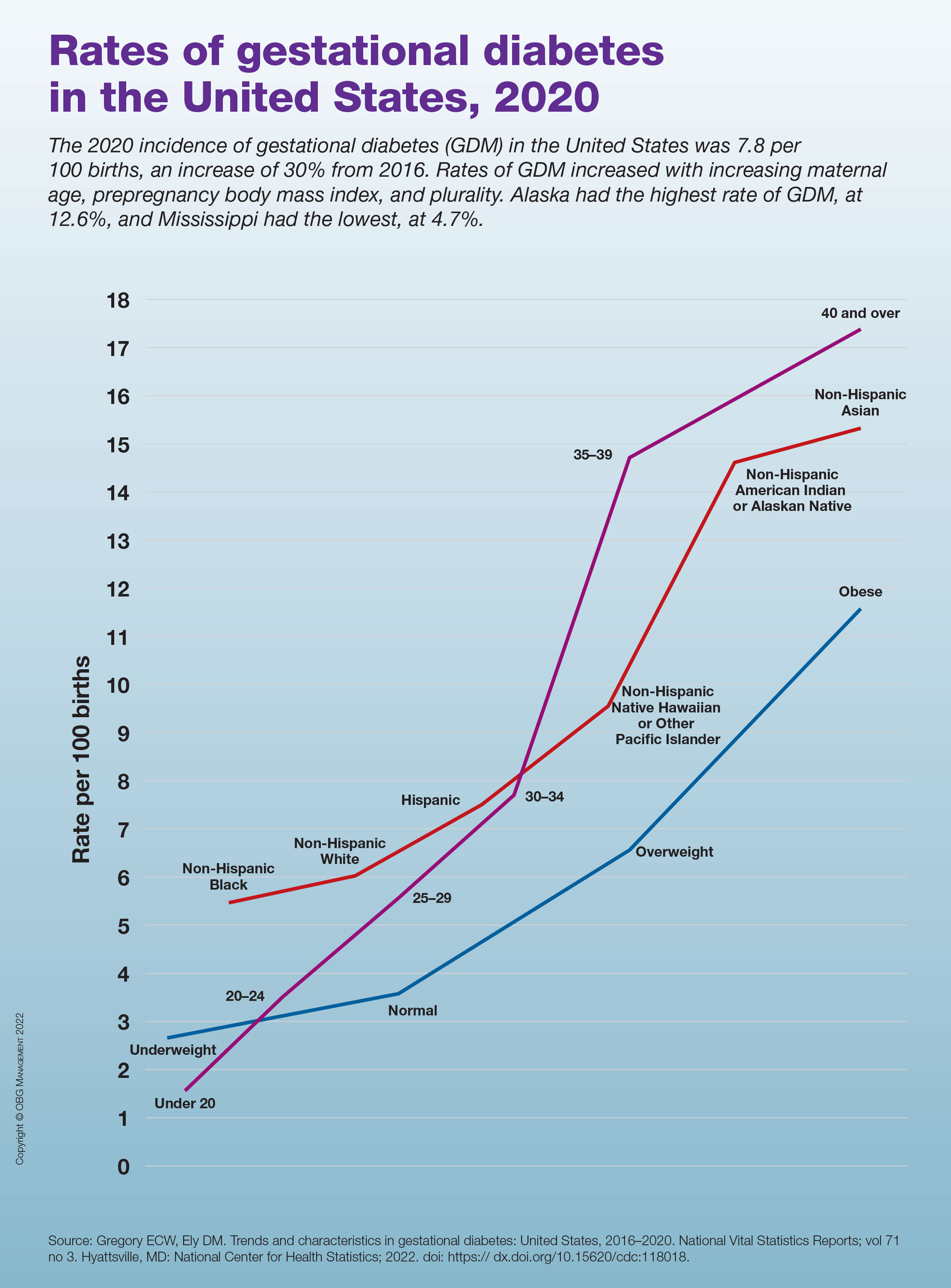

Rates of gestational diabetes in the United States, 2020

Commentary: Menstruation, sleep, and visual disturbances in migraine, October 2022

Lasmiditan—the first migraine treatment in the new ditan class— is a serotonin receptor agonist, similar to triptan medications. However, it is specific for the 5HT1F receptor rather than the 5HT1B/1D receptor. The main purpose of this specificity is that it leads to less vascular risk; specifically, this medication should be safer for populations at higher risk for vascular events, such as myocardial infarction and stroke.

Only one triptan, naratriptan, had previously been studied for the treatment of menstrual migraine, at a recommended dose of 2.5 mg twice daily as a bridge. A new study by MacGregor and colleagues looked at taking 50, 100, or 200 mg of lasmiditan vs placebo for an individual premenstrual attack.

The participants in the study were recruited from the intention-to-treat population of two prior studies for this drug, a phase 2 trial and a phase 3 trial. The menstrual calendars of the female participants were reviewed, followed by randomization into one of the four groups. Patients with chronic migraine were excluded from the study. The primary outcome was freedom from pain at 2 hours; secondary outcomes were freedom from the most bothersome symptom and reduction in pain severity.

Of the four populations followed, all three intervention groups noted significant results in freedom from pain at 2 hours compared with placebo. The 2-hour responder rate was 33.6% for the 200 mg group, 16.7% for the 50 mg and 100 mg groups, and 7.6% for the placebo group. Freedom from the most bothersome symptom and pain reduction were also significant in these populations.

Menstruation-associated migraine and worsening headache attacks due to patients' hormonal fluctuations are some of the most common issues and triggers that neurologists and headache specialists confront. Although the responder rates for freedom from pain at 2 hours were not very robust, lasmiditan does appear to be significantly effective in this population, and in those with menstrual triggers specifically. The field of headache medicine would be even better served by additional studies on both preventive and more acute medications in association with hormonal triggers.

Another very common trigger for migraine is changes in sleep patterns. An astute headache specialist will always ask about sleep quantity and quality during an initial assessment of a patient. Many headache centers have sleep-specific questionnaires that patients fill out during intake. The precise association between migraine and sleep deserves more elucidation. Duan and colleagues specifically set out to reveal whether differences in sleep quality affect migraine frequency; whether this is the same among different gender and age groups; and whether headache disability, severity, mood, and quality of life are related to underlying sleep changes independent of other factors.

A total of 134 participants with migraine and 70 without migraine or any other headache disorder were enrolled in the study. Sleep quality was assessed through The Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI) questionnaire. This is a commonly used self-reported questionnaire for assessing quality and quantity of sleep over the past month and is considered the standard of care in most sleep centers. The investigators here sought to determine the predictive value of the PSQI in regard to migraine. Migraine disability was assessed via the Migraine Disability Assessment (MIDAS) scale as well as the Headache Impact Test (HIT-6). Statistical analysis was performed with logistical regression, t test, and χ2 squared test.

There strongest correlations between poor sleep quality and risk of migraine were found in women, patients over 35 years old, and those with lower education levels. The results revealed that the migraine group had poorer sleep quality, as well as higher anxiety and depression scores, compared with the control group. A low PSQI score (eg, poorer sleep quality) was associated with higher migraine frequency; this was independent of body mass index (BMI), weekly exercise time, and smoking or drinking history. After participants were divided into good and poor sleep quality subgroups, the PSQI score was found to increase the odds ratio of migraine by a factor of 6.

The investigators were able to show the predictive quality of the PSQI score. Worse sleep quality was found to be associated with a higher MIDAS score and HIT-6 score as well as total pain burden, pain severity, decreased quality of life, depression, and anxiety. Although most headache specialists spend a significant amount of time discussing sleep as it relates to migraine, it may be worth considering following a sleep quality scale, such as the PSQI, over time as we monitor our patients. This may allow us to take a more proactive role and be able to prognosticate our patients' migraine journey somewhat better. Although sleep triggers and associations with migraine can be very difficult to discuss and treat, this study very clearly argues for the importance of focusing on sleep with our patients.

Although the most common aura our patients with migraine experience is visual, many patients with migraine will also experience non-aura visual changes. These can range from short-lasting episodes of blurred vision, such as transient visual obscurations, or other transient visual disturbances that do not fit the criteria of aura as defined by the International Classification of Headache Disorders (ICHD).