User login

Nasal Tanning Sprays: Illuminating the Risks of a Popular TikTok Trend

Nasal tanning spray is a recent phenomenon that has been gaining popularity among consumers on TikTok and other social media platforms. The active ingredient in the tanning spray is melanotan II—a synthetic analog of α‒melanocyte-stimulating hormone,1,2 a naturally occurring hormone responsible for skin pigmentation. α‒Melanocyte-stimulating hormone is a derivative of the precursor proopiomelanocortin, an agonist on the melanocortin-1 receptor that promotes formation of eumelanin.1,3 Eumelanin then provides pigmentation to the skin.3 Apart from its use for tanning, melanotan II has been reported to increase sexual function and aid in weight loss.1

Melanotan II is not approved by the US Food and Drug Administration; however, injectable formulations can be obtained illegally on the Internet as well as at some tanning salons and beauty parlors.4 Although injectable forms of melanotan II have been used for years to artificially increase skin pigmentation, the newly hyped nasal tanning sprays are drawing the attention of consumers. The synthetic chemical spray is inhaled into the nasal mucosae, where it is readily absorbed into the bloodstream to act on melanocortin receptors throughout the body, thus enhancing skin pigmentation.2 Because melanotan II is not approved, there is no guarantee that the product purchased from those sources is pure; therefore, consumers risk inhaling or injecting contaminated chemicals.5

In a 2017 study, Kirk and Greenfield6 cited self-image as a common concern among participants who expressed a preference for appearing tanned.6 Societal influence and standards to which young adults, particularly young women, often are accustomed drive some to take steps to achieve tanned skin, which they view as more attractive and healthier than untanned skin.7,8

Social media consumption is a significant risk factor for developing or exacerbating body dissatisfaction among impressionable teenagers and young adults, who may be less risk averse and therefore choose to embrace trends such as nasal tanning sprays to enhance their appearance, without considering possible consequences. Most young adults, and even teens, are aware of the risks associated with tanning beds, which may propel them to seek out what they perceive as a less-risky tanning alternative such as a tanner delivered via a nasal route, but it is unlikely that this group is fully informed about the possible dangers of nasal tanning sprays.

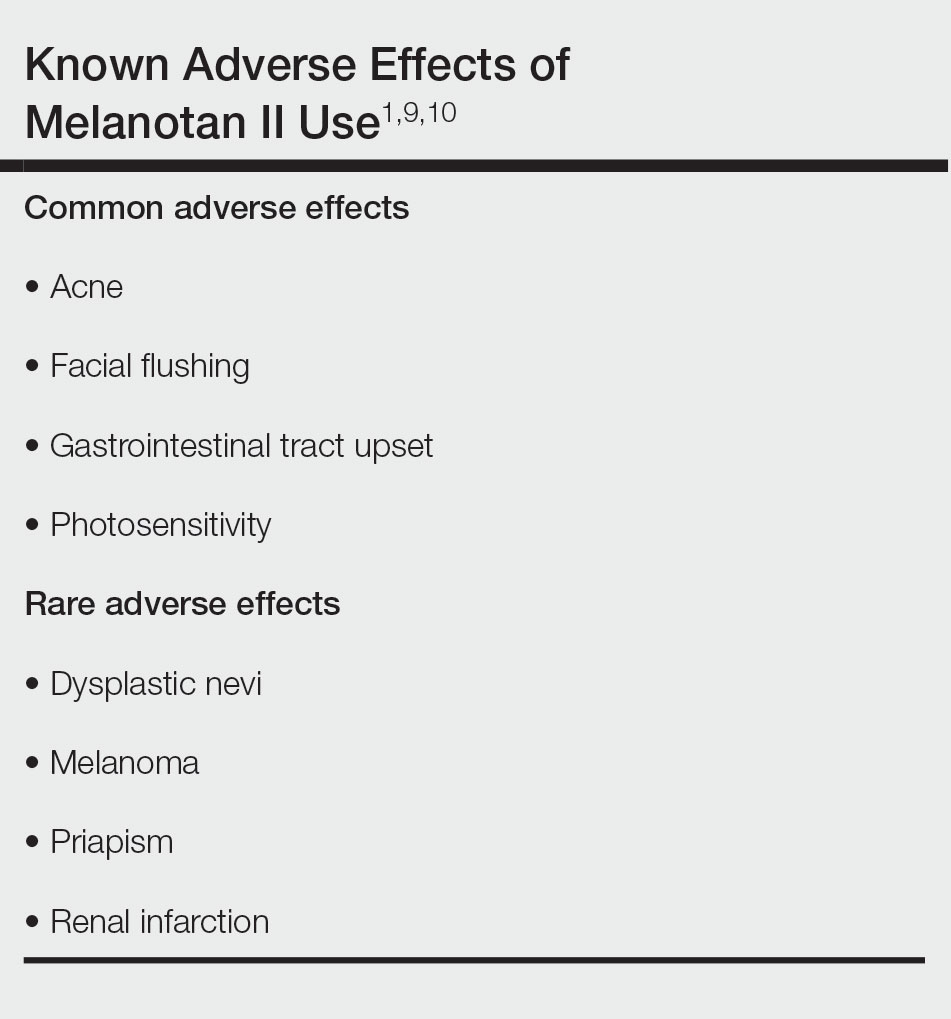

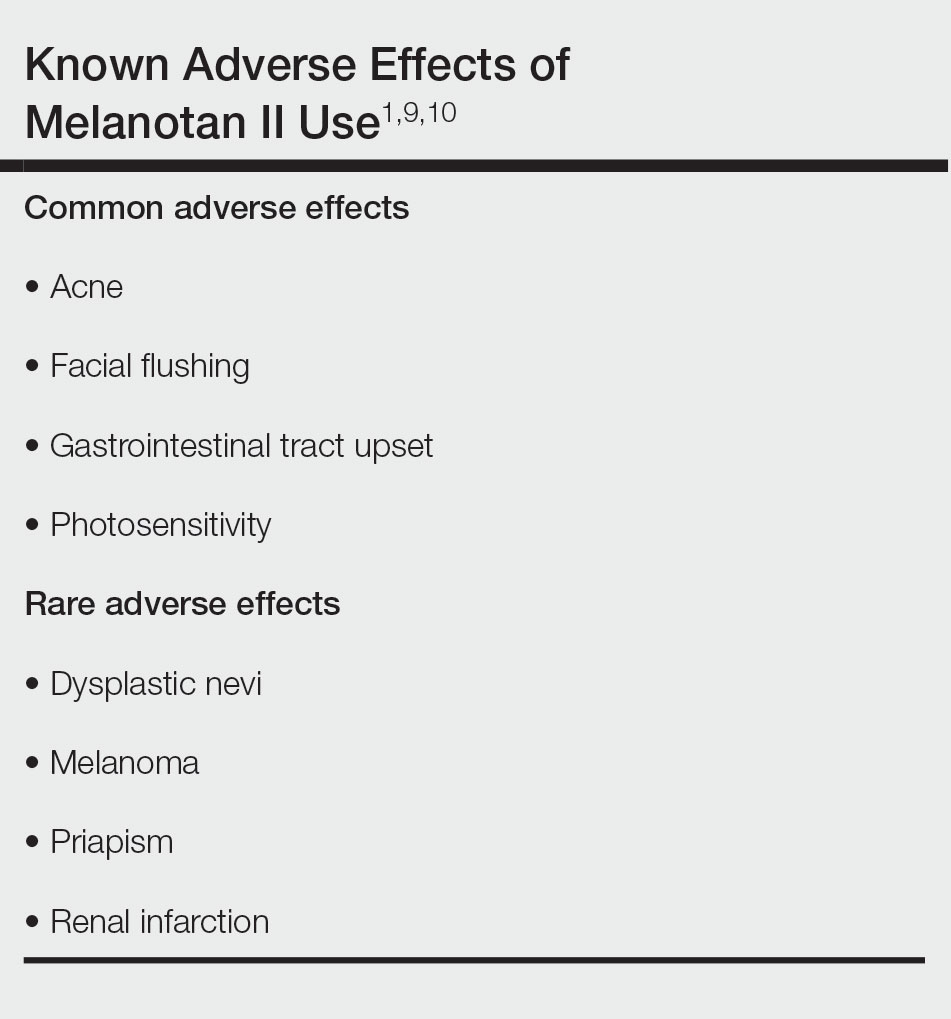

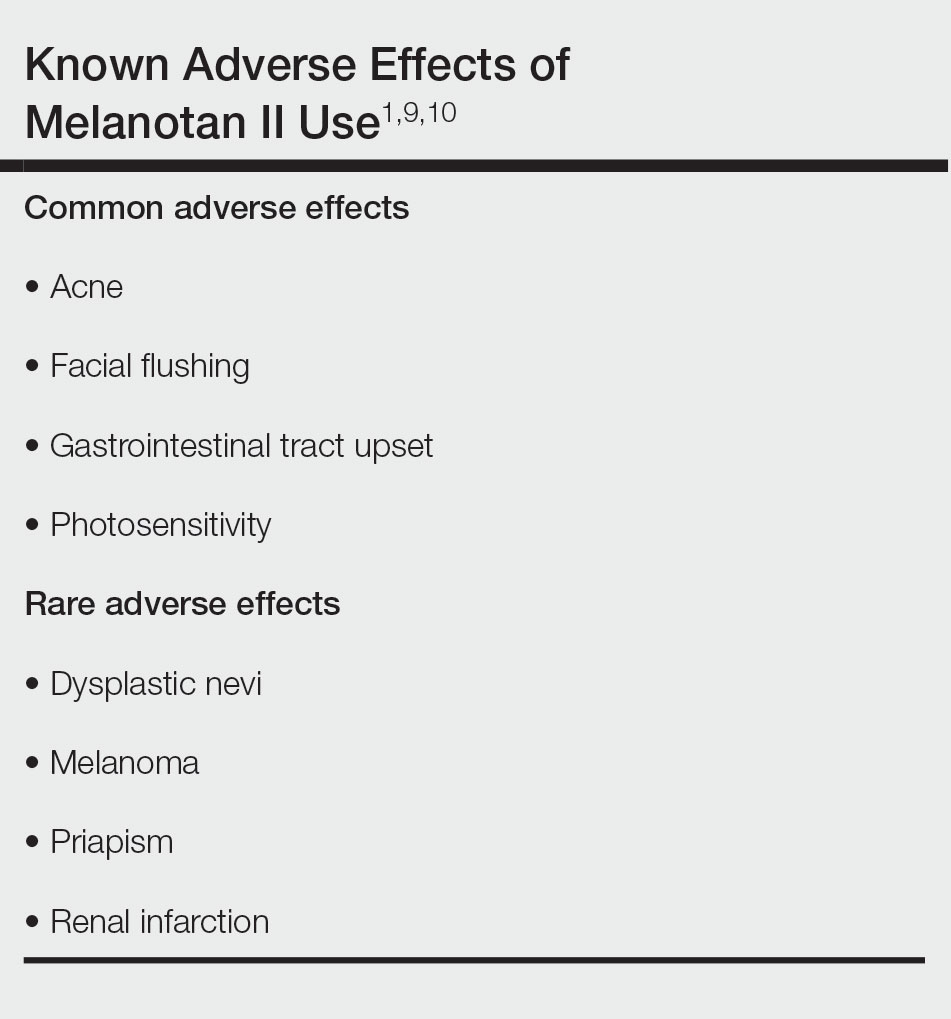

It is crucial for dermatologists and other clinicians to provide awareness and education about the potential harm of nasal tanning sprays. Along with the general risks of using an unregulated substance, common adverse effects include acne, facial flushing, gastrointestinal tract upset, and sensitivity to sunlight (Table).1,9,10 Several case reports have linked melanotan II to cutaneous changes, including dysplastic nevi and even melanoma.1 Less common complications, such as renal infarction and priapism, also have been observed with melanotan II use.9,10

Even with the known risks involving tanning beds and skin cancer, an analysis by Kream et al11 in 2020 showed that 90% (441/488) of tanning-related videos on TikTok promoted a positive view of tanning. Of these TikTok videos involving pro-tanning trends, 3% (12/441) were specifically about melanotan II nasal spray, injection, or both, which has only become more popular since this study was published.11

Dermatologists should be aware of the impact that tanning trends, such as nasal tanning spray, can have on all patients and initiate discussions regarding the risks of using these products with patients as appropriate. Alternatives to nasal tanning sprays such as spray-on tans and self-tanning lotions are safer ways for patients to achieve a tanned look without the health risks associated with melanotan II.

- Habbema L, Halk AB, Neumann M, et al. Risks of unregulated use of alpha-melanocyte-stimulating hormone analogues: a review. Int J Dermatol. 2017;56:975-980. doi:10.1111/ijd.13585

- Why you should never use nasal tanning spray. Cleveland Clinic Health Essentials [Internet]. November 1, 2022. Accessed December 18, 2023. https://health.clevelandclinic.org/nasal-tanning-spray

- Hjuler KF, Lorentzen HF. Melanoma associated with the use of melanotan-II. Dermatology. 2014;228:34-36. doi:10.1159/000356389

- Evans-Brown M, Dawson RT, Chandler M, et al. Use of melanotan I and II in the general population. BMJ. 2009;338:b566. doi:10.116/bmj.b566

- Callaghan DJ III. A glimpse into the underground market of melanotan. Dermatol Online J. 2018;24:1-5. doi:10.5070/D3245040036

- Kirk L, Greenfield S. Knowledge and attitudes of UK university students in relation to ultraviolet radiation (UVR) exposure and their sun-related behaviours: a qualitative study. BMJ Open. 2017;7:e014388. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2016-014388

- Hay JL, Geller AC, Schoenhammer M, et al. Tanning and beauty: mother and teenage daughters in discussion. J Health Psychol. 2016;21:1261-1270. doi:10.1177/1359105314551621

- Gillen MM, Markey CN. The role of body image and depression in tanning behaviors and attitudes. Behav Med. 2017;38:74-82.

- Peters B, Hadimeri H, Wahlberg R, et al. Melanotan II: a possible cause of renal infarction: review of the literature and case report. CEN Case Rep. 2020;9:159-161. doi:10.1007/s13730-020-00447-z

- Mallory CW, Lopategui DM, Cordon BH. Melanotan tanning injection: a rare cause of priapism. Sex Med. 2021;9:100298. doi:10.1016/j.esxm.2020.100298

- Kream E, Watchmaker JD, Dover JS. TikTok sheds light on tanning: tanning is still popular and emerging trends pose new risks. Dermatol Surg. 2022;48:1018-1021. doi:10.1097/DSS.0000000000003549

Nasal tanning spray is a recent phenomenon that has been gaining popularity among consumers on TikTok and other social media platforms. The active ingredient in the tanning spray is melanotan II—a synthetic analog of α‒melanocyte-stimulating hormone,1,2 a naturally occurring hormone responsible for skin pigmentation. α‒Melanocyte-stimulating hormone is a derivative of the precursor proopiomelanocortin, an agonist on the melanocortin-1 receptor that promotes formation of eumelanin.1,3 Eumelanin then provides pigmentation to the skin.3 Apart from its use for tanning, melanotan II has been reported to increase sexual function and aid in weight loss.1

Melanotan II is not approved by the US Food and Drug Administration; however, injectable formulations can be obtained illegally on the Internet as well as at some tanning salons and beauty parlors.4 Although injectable forms of melanotan II have been used for years to artificially increase skin pigmentation, the newly hyped nasal tanning sprays are drawing the attention of consumers. The synthetic chemical spray is inhaled into the nasal mucosae, where it is readily absorbed into the bloodstream to act on melanocortin receptors throughout the body, thus enhancing skin pigmentation.2 Because melanotan II is not approved, there is no guarantee that the product purchased from those sources is pure; therefore, consumers risk inhaling or injecting contaminated chemicals.5

In a 2017 study, Kirk and Greenfield6 cited self-image as a common concern among participants who expressed a preference for appearing tanned.6 Societal influence and standards to which young adults, particularly young women, often are accustomed drive some to take steps to achieve tanned skin, which they view as more attractive and healthier than untanned skin.7,8

Social media consumption is a significant risk factor for developing or exacerbating body dissatisfaction among impressionable teenagers and young adults, who may be less risk averse and therefore choose to embrace trends such as nasal tanning sprays to enhance their appearance, without considering possible consequences. Most young adults, and even teens, are aware of the risks associated with tanning beds, which may propel them to seek out what they perceive as a less-risky tanning alternative such as a tanner delivered via a nasal route, but it is unlikely that this group is fully informed about the possible dangers of nasal tanning sprays.

It is crucial for dermatologists and other clinicians to provide awareness and education about the potential harm of nasal tanning sprays. Along with the general risks of using an unregulated substance, common adverse effects include acne, facial flushing, gastrointestinal tract upset, and sensitivity to sunlight (Table).1,9,10 Several case reports have linked melanotan II to cutaneous changes, including dysplastic nevi and even melanoma.1 Less common complications, such as renal infarction and priapism, also have been observed with melanotan II use.9,10

Even with the known risks involving tanning beds and skin cancer, an analysis by Kream et al11 in 2020 showed that 90% (441/488) of tanning-related videos on TikTok promoted a positive view of tanning. Of these TikTok videos involving pro-tanning trends, 3% (12/441) were specifically about melanotan II nasal spray, injection, or both, which has only become more popular since this study was published.11

Dermatologists should be aware of the impact that tanning trends, such as nasal tanning spray, can have on all patients and initiate discussions regarding the risks of using these products with patients as appropriate. Alternatives to nasal tanning sprays such as spray-on tans and self-tanning lotions are safer ways for patients to achieve a tanned look without the health risks associated with melanotan II.

Nasal tanning spray is a recent phenomenon that has been gaining popularity among consumers on TikTok and other social media platforms. The active ingredient in the tanning spray is melanotan II—a synthetic analog of α‒melanocyte-stimulating hormone,1,2 a naturally occurring hormone responsible for skin pigmentation. α‒Melanocyte-stimulating hormone is a derivative of the precursor proopiomelanocortin, an agonist on the melanocortin-1 receptor that promotes formation of eumelanin.1,3 Eumelanin then provides pigmentation to the skin.3 Apart from its use for tanning, melanotan II has been reported to increase sexual function and aid in weight loss.1

Melanotan II is not approved by the US Food and Drug Administration; however, injectable formulations can be obtained illegally on the Internet as well as at some tanning salons and beauty parlors.4 Although injectable forms of melanotan II have been used for years to artificially increase skin pigmentation, the newly hyped nasal tanning sprays are drawing the attention of consumers. The synthetic chemical spray is inhaled into the nasal mucosae, where it is readily absorbed into the bloodstream to act on melanocortin receptors throughout the body, thus enhancing skin pigmentation.2 Because melanotan II is not approved, there is no guarantee that the product purchased from those sources is pure; therefore, consumers risk inhaling or injecting contaminated chemicals.5

In a 2017 study, Kirk and Greenfield6 cited self-image as a common concern among participants who expressed a preference for appearing tanned.6 Societal influence and standards to which young adults, particularly young women, often are accustomed drive some to take steps to achieve tanned skin, which they view as more attractive and healthier than untanned skin.7,8

Social media consumption is a significant risk factor for developing or exacerbating body dissatisfaction among impressionable teenagers and young adults, who may be less risk averse and therefore choose to embrace trends such as nasal tanning sprays to enhance their appearance, without considering possible consequences. Most young adults, and even teens, are aware of the risks associated with tanning beds, which may propel them to seek out what they perceive as a less-risky tanning alternative such as a tanner delivered via a nasal route, but it is unlikely that this group is fully informed about the possible dangers of nasal tanning sprays.

It is crucial for dermatologists and other clinicians to provide awareness and education about the potential harm of nasal tanning sprays. Along with the general risks of using an unregulated substance, common adverse effects include acne, facial flushing, gastrointestinal tract upset, and sensitivity to sunlight (Table).1,9,10 Several case reports have linked melanotan II to cutaneous changes, including dysplastic nevi and even melanoma.1 Less common complications, such as renal infarction and priapism, also have been observed with melanotan II use.9,10

Even with the known risks involving tanning beds and skin cancer, an analysis by Kream et al11 in 2020 showed that 90% (441/488) of tanning-related videos on TikTok promoted a positive view of tanning. Of these TikTok videos involving pro-tanning trends, 3% (12/441) were specifically about melanotan II nasal spray, injection, or both, which has only become more popular since this study was published.11

Dermatologists should be aware of the impact that tanning trends, such as nasal tanning spray, can have on all patients and initiate discussions regarding the risks of using these products with patients as appropriate. Alternatives to nasal tanning sprays such as spray-on tans and self-tanning lotions are safer ways for patients to achieve a tanned look without the health risks associated with melanotan II.

- Habbema L, Halk AB, Neumann M, et al. Risks of unregulated use of alpha-melanocyte-stimulating hormone analogues: a review. Int J Dermatol. 2017;56:975-980. doi:10.1111/ijd.13585

- Why you should never use nasal tanning spray. Cleveland Clinic Health Essentials [Internet]. November 1, 2022. Accessed December 18, 2023. https://health.clevelandclinic.org/nasal-tanning-spray

- Hjuler KF, Lorentzen HF. Melanoma associated with the use of melanotan-II. Dermatology. 2014;228:34-36. doi:10.1159/000356389

- Evans-Brown M, Dawson RT, Chandler M, et al. Use of melanotan I and II in the general population. BMJ. 2009;338:b566. doi:10.116/bmj.b566

- Callaghan DJ III. A glimpse into the underground market of melanotan. Dermatol Online J. 2018;24:1-5. doi:10.5070/D3245040036

- Kirk L, Greenfield S. Knowledge and attitudes of UK university students in relation to ultraviolet radiation (UVR) exposure and their sun-related behaviours: a qualitative study. BMJ Open. 2017;7:e014388. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2016-014388

- Hay JL, Geller AC, Schoenhammer M, et al. Tanning and beauty: mother and teenage daughters in discussion. J Health Psychol. 2016;21:1261-1270. doi:10.1177/1359105314551621

- Gillen MM, Markey CN. The role of body image and depression in tanning behaviors and attitudes. Behav Med. 2017;38:74-82.

- Peters B, Hadimeri H, Wahlberg R, et al. Melanotan II: a possible cause of renal infarction: review of the literature and case report. CEN Case Rep. 2020;9:159-161. doi:10.1007/s13730-020-00447-z

- Mallory CW, Lopategui DM, Cordon BH. Melanotan tanning injection: a rare cause of priapism. Sex Med. 2021;9:100298. doi:10.1016/j.esxm.2020.100298

- Kream E, Watchmaker JD, Dover JS. TikTok sheds light on tanning: tanning is still popular and emerging trends pose new risks. Dermatol Surg. 2022;48:1018-1021. doi:10.1097/DSS.0000000000003549

- Habbema L, Halk AB, Neumann M, et al. Risks of unregulated use of alpha-melanocyte-stimulating hormone analogues: a review. Int J Dermatol. 2017;56:975-980. doi:10.1111/ijd.13585

- Why you should never use nasal tanning spray. Cleveland Clinic Health Essentials [Internet]. November 1, 2022. Accessed December 18, 2023. https://health.clevelandclinic.org/nasal-tanning-spray

- Hjuler KF, Lorentzen HF. Melanoma associated with the use of melanotan-II. Dermatology. 2014;228:34-36. doi:10.1159/000356389

- Evans-Brown M, Dawson RT, Chandler M, et al. Use of melanotan I and II in the general population. BMJ. 2009;338:b566. doi:10.116/bmj.b566

- Callaghan DJ III. A glimpse into the underground market of melanotan. Dermatol Online J. 2018;24:1-5. doi:10.5070/D3245040036

- Kirk L, Greenfield S. Knowledge and attitudes of UK university students in relation to ultraviolet radiation (UVR) exposure and their sun-related behaviours: a qualitative study. BMJ Open. 2017;7:e014388. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2016-014388

- Hay JL, Geller AC, Schoenhammer M, et al. Tanning and beauty: mother and teenage daughters in discussion. J Health Psychol. 2016;21:1261-1270. doi:10.1177/1359105314551621

- Gillen MM, Markey CN. The role of body image and depression in tanning behaviors and attitudes. Behav Med. 2017;38:74-82.

- Peters B, Hadimeri H, Wahlberg R, et al. Melanotan II: a possible cause of renal infarction: review of the literature and case report. CEN Case Rep. 2020;9:159-161. doi:10.1007/s13730-020-00447-z

- Mallory CW, Lopategui DM, Cordon BH. Melanotan tanning injection: a rare cause of priapism. Sex Med. 2021;9:100298. doi:10.1016/j.esxm.2020.100298

- Kream E, Watchmaker JD, Dover JS. TikTok sheds light on tanning: tanning is still popular and emerging trends pose new risks. Dermatol Surg. 2022;48:1018-1021. doi:10.1097/DSS.0000000000003549

PRACTICE POINTS

- Although tanning beds are arguably the most common and dangerous method used by patients to tan their skin, dermatologists should be aware of the other means by which patients may artificially increase skin pigmentation and the risks imposed by undertaking such practices.

- We challenge dermatologists to note the influence of social media on tanning trends and consider creating a platform on these mediums to combat misinformation and promote sun safety and skin health.

- We encourage dermatologists to diligently stay informed about the popular societal trends related to the skin such as the use of nasal tanning products (eg, melanotan I and II) and be proactive in discussing their risks with patients as deemed appropriate.

Migratory Nodules in a Traveler

The Diagnosis: Gnathostomiasis

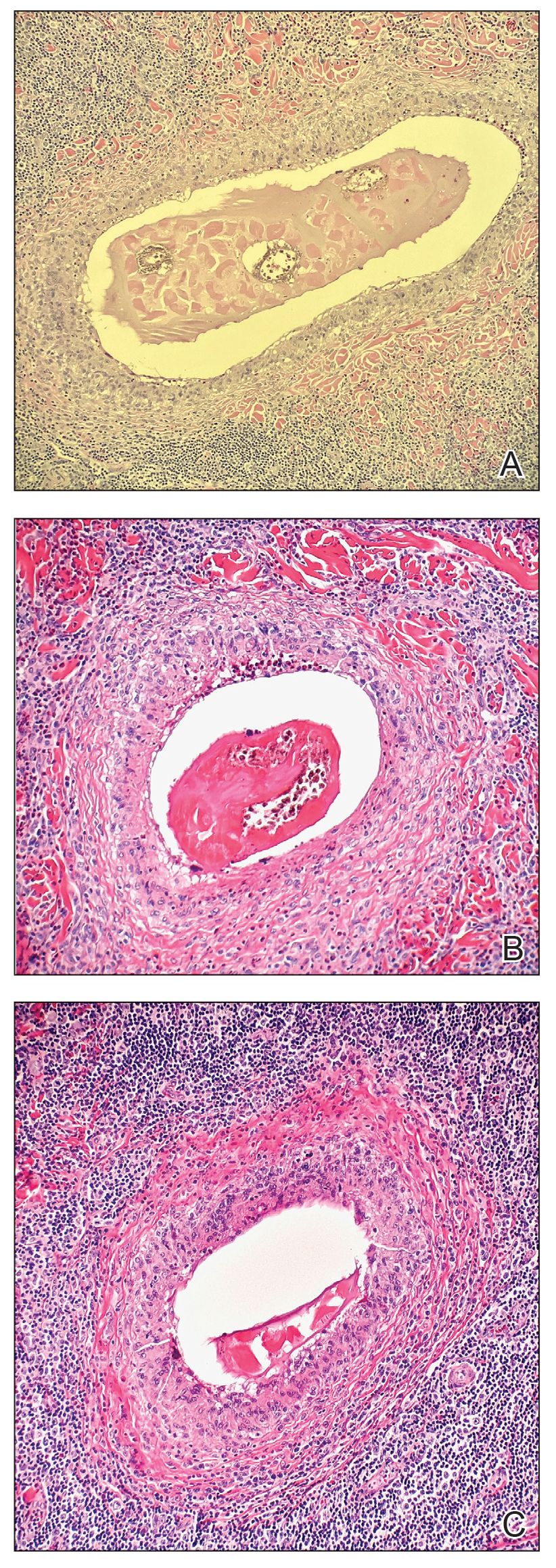

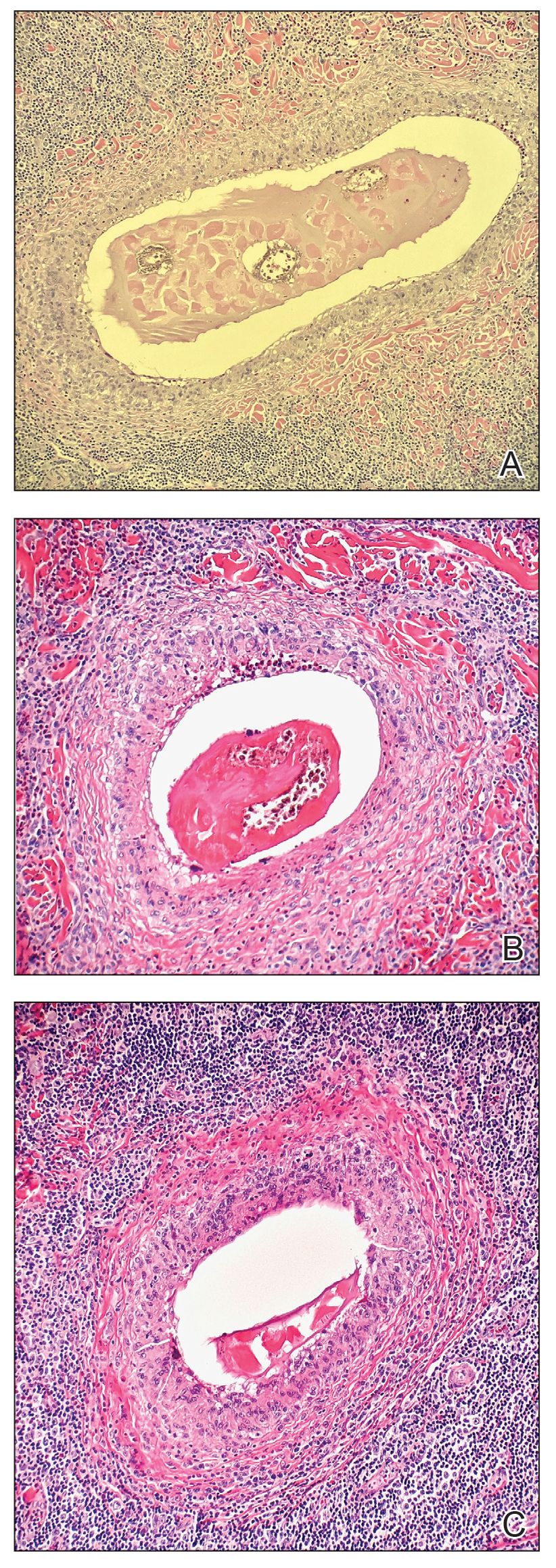

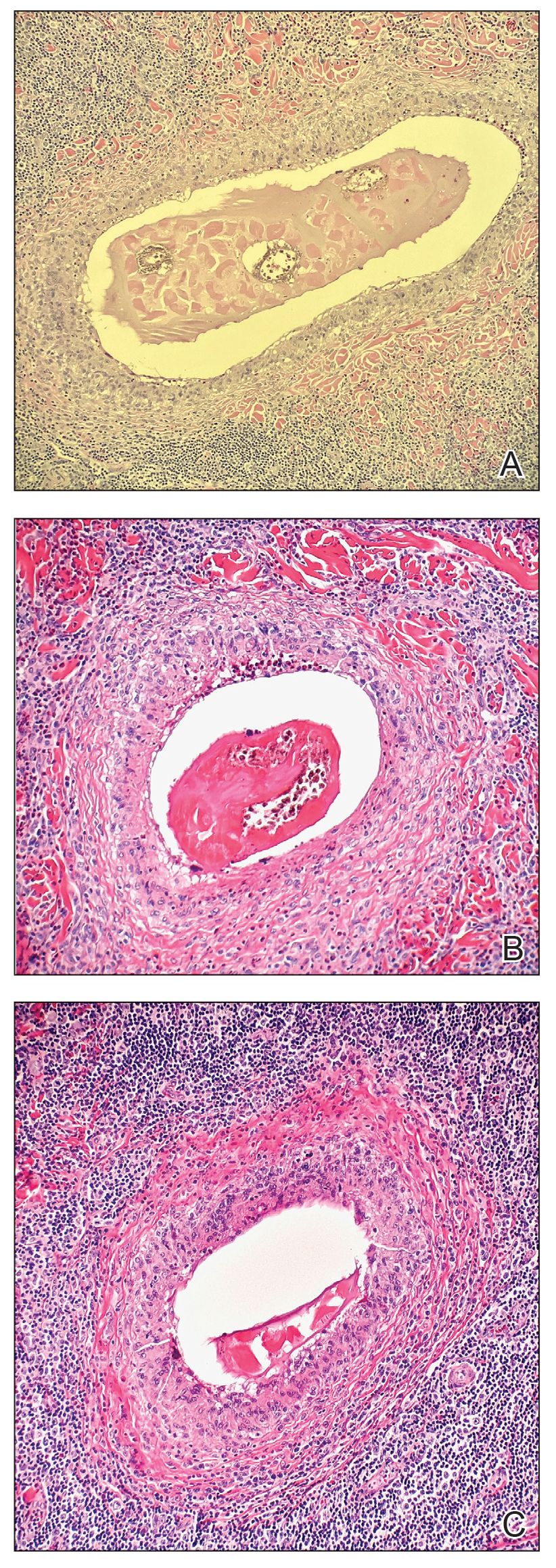

The biopsy demonstrated a dense, eosinophilic, granulomatous infiltrate surrounding sections of a parasite with skeletal muscle bundles and intestines containing a brush border and luminal debris (Figure), which was consistent with a diagnosis of gnathostomiasis. Upon further questioning, he revealed that while in Peru he frequently consumed ceviche, which is a dish typically made from fresh raw fish cured in lemon or lime juice. He subsequently was treated with oral ivermectin 0.2 mg/kg once daily for 2 days with no evidence of recurrence 12 months later.

Cutaneous gnathostomiasis is the most common manifestation of infection caused by the third-stage larvae of the genus Gnathostoma. The nematode is endemic to tropical and subtropical regions of Japan and Southeast Asia, particularly Thailand. The disease has been increasingly observed in Central and South America. Humans can become infected through ingestion of undercooked meats, particularly freshwater fish but also poultry, snakes, or frogs. Few cases have been reported in North America and Europe presumably due to more stringent regulations governing the sourcing and storage of fish for consumption.1-3 Restaurants in endemic regions also may use cheaper local freshwater or brackish fish compared to restaurants in the West, which use more expensive saltwater fish that do not harbor Gnathostoma species.1 There is a false belief among restauranteurs and consumers that the larvae can be reliably killed by marinating meat in citrus juice or with concurrent consumption of alcohol or hot spices.2 Adequately cooking or freezing meat to 20 °C for 3 to 5 days are the only effective ways to ensure that the larvae are killed.1-3

The parasite requires its natural definitive hosts—fish-eating mammals such as pigs, cats, and dogs—to complete its life cycle and reproduce. Humans are accidental hosts in whom the parasite fails to reach sexual maturity.1-3 Consequently, symptoms commonly are due to the migration of only 1 larva, but occasionally infection with 2 or more has been observed.1,4

Human infection initially may result in malaise, fever, anorexia, abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea as the parasite migrates through the stomach, intestines, and liver. After 2 to 4 weeks, larvae may reach the skin where they most commonly create ill-defined, erythematous, indurated, round or oval plaques or nodules described as nodular migratory panniculitis. These lesions tend to develop on the trunk or arms and correspond to the location of the migrating worm.1,3,5 The larvae have been observed to migrate at 1 cm/h.6 Symptoms often wax and wane, with individual nodules lasting approximately 1 to 2 weeks. Uniquely, larval migration can result in a trail of subcutaneous hemorrhage that is considered pathognomonic and helps to differentiate gnathostomiasis from other forms of parasitosis such as strongyloidiasis and sparganosis.1,3 Larvae are highly motile and invasive, and they are capable of producing a wide range of symptoms affecting virtually any part of the body.1,2 Depending on the anatomic location of the migrating worm, infection also may result in neurologic, gastrointestinal, pulmonary, or ocular symptoms.1-3,7 Eosinophilia is common but can subside in the chronic stage, as seen in our patient.1

The classic triad of intermittent migratory nodules, eosinophilia, and a history of travel to Southeast Asia or another endemic region should raise suspicion for gnathostomiasis.1-3,5,7 Unfortunately, confirmatory testing such as Gnathostoma serology is not readily available in the United States, and available serologic tests demonstrate frequent false positives and incomplete crossreactivity.1,2,8 Accordingly, the diagnosis most commonly is solidified by combining cardinal clinical features with histologic findings of a dense eosinophilic inflammatory infiltrate involving the dermis and hypodermis.2,5 In one study, the larva itself was only found in 12 of 66 (18%) skin biopsy specimens from patients with gnathostomiasis.5 If the larva is detected within the sections, it ranges from 2.5 to 12.5 mm in length and 0.4 to 1.2 mm in width and can exhibit cuticular spines, intestinal cells, and characteristic large lateral chords.1,5

The treatment of choice is surgical removal of the worm. Oral albendazole (400–800 mg/d for 21 days) also is considered a first-line treatment and results in clinical cure in approximately 90% of cases. Two doses of oral ivermectin (0.2 mg/kg) spaced 24 to 48 hours apart is an acceptable alternative with comparable efficacy.1-3 Care should be taken if involvement of the central nervous system is suspected, as antihelminthic treatment theoretically could be deleterious due to an inflammatory response to the dying larvae.1,2,9

In the differential diagnosis, loiasis can resemble gnathostomiasis, but the former is endemic to Africa.3 Cutaneous larva migrans most frequently is caused by hookworms from the genus Ancylostoma, which classically leads to superficial serpiginous linear plaques that migrate at a rate of several millimeters per day. However, the larvae are believed to lack the collagenase enzyme required to penetrate the epidermal basement membrane and thus are not capable of producing deep-seated nodules or visceral symptoms.3 Strongyloidiasis (larva currens) generally exhibits a more linear morphology, and infection would result in positive Strongyloides serology.7 Erythema nodosum is a septal panniculitis that can be triggered by infection, pregnancy, medications, connective tissue diseases, inflammatory conditions, and underlying malignancy.10

- Herman JS, Chiodini PL. Gnathostomiasis, another emerging imported disease. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2009;22:484-492.

- Liu GH, Sun MM, Elsheikha HM, et al. Human gnathostomiasis: a neglected food-borne zoonosis. Parasit Vectors. 2020;13:616.

- Tyring SK. Gnathostomiasis. In: Tyring SK, Lupi O, Hengge UR, eds. Tropical Dermatology. 2nd ed. Elsevier; 2017:77-78.

- Rusnak JM, Lucey DR. Clinical gnathostomiasis: case report and review of the English-language literature. Clin Infect Dis. 1993;16:33-50.

- Magaña M, Messina M, Bustamante F, et al. Gnathostomiasis: clinicopathologic study. Am J Dermatopathol. 2004;26:91-95.

- Chandenier J, Husson J, Canaple S, et al. Medullary gnathostomiasis in a white patient: use of immunodiagnosis and magnetic resonance imaging. Clin Infect Dis. 2001;32:E154-E157.

- Hamilton WL, Agranoff D. Imported gnathostomiasis manifesting as cutaneous larva migrans and Löffler’s syndrome. BMJ Case Rep. 2018;2018:bcr2017223132.

- Neumayr A, Ollague J, Bravo F, et al. Cross-reactivity pattern of Asian and American human gnathostomiasis in western blot assays using crude antigens prepared from Gnathostoma spinigerum and Gnathostoma binucleatum third-stage larvae. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2016;95:413-416.

- Kraivichian K, Nuchprayoon S, Sitichalernchai P, et al. Treatment of cutaneous gnathostomiasis with ivermectin. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2004;71:623-628.

- Pérez-Garza DM, Chavez-Alvarez S, Ocampo-Candiani J, et al. Erythema nodosum: a practical approach and diagnostic algorithm. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2021;22:367-378.

The Diagnosis: Gnathostomiasis

The biopsy demonstrated a dense, eosinophilic, granulomatous infiltrate surrounding sections of a parasite with skeletal muscle bundles and intestines containing a brush border and luminal debris (Figure), which was consistent with a diagnosis of gnathostomiasis. Upon further questioning, he revealed that while in Peru he frequently consumed ceviche, which is a dish typically made from fresh raw fish cured in lemon or lime juice. He subsequently was treated with oral ivermectin 0.2 mg/kg once daily for 2 days with no evidence of recurrence 12 months later.

Cutaneous gnathostomiasis is the most common manifestation of infection caused by the third-stage larvae of the genus Gnathostoma. The nematode is endemic to tropical and subtropical regions of Japan and Southeast Asia, particularly Thailand. The disease has been increasingly observed in Central and South America. Humans can become infected through ingestion of undercooked meats, particularly freshwater fish but also poultry, snakes, or frogs. Few cases have been reported in North America and Europe presumably due to more stringent regulations governing the sourcing and storage of fish for consumption.1-3 Restaurants in endemic regions also may use cheaper local freshwater or brackish fish compared to restaurants in the West, which use more expensive saltwater fish that do not harbor Gnathostoma species.1 There is a false belief among restauranteurs and consumers that the larvae can be reliably killed by marinating meat in citrus juice or with concurrent consumption of alcohol or hot spices.2 Adequately cooking or freezing meat to 20 °C for 3 to 5 days are the only effective ways to ensure that the larvae are killed.1-3

The parasite requires its natural definitive hosts—fish-eating mammals such as pigs, cats, and dogs—to complete its life cycle and reproduce. Humans are accidental hosts in whom the parasite fails to reach sexual maturity.1-3 Consequently, symptoms commonly are due to the migration of only 1 larva, but occasionally infection with 2 or more has been observed.1,4

Human infection initially may result in malaise, fever, anorexia, abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea as the parasite migrates through the stomach, intestines, and liver. After 2 to 4 weeks, larvae may reach the skin where they most commonly create ill-defined, erythematous, indurated, round or oval plaques or nodules described as nodular migratory panniculitis. These lesions tend to develop on the trunk or arms and correspond to the location of the migrating worm.1,3,5 The larvae have been observed to migrate at 1 cm/h.6 Symptoms often wax and wane, with individual nodules lasting approximately 1 to 2 weeks. Uniquely, larval migration can result in a trail of subcutaneous hemorrhage that is considered pathognomonic and helps to differentiate gnathostomiasis from other forms of parasitosis such as strongyloidiasis and sparganosis.1,3 Larvae are highly motile and invasive, and they are capable of producing a wide range of symptoms affecting virtually any part of the body.1,2 Depending on the anatomic location of the migrating worm, infection also may result in neurologic, gastrointestinal, pulmonary, or ocular symptoms.1-3,7 Eosinophilia is common but can subside in the chronic stage, as seen in our patient.1

The classic triad of intermittent migratory nodules, eosinophilia, and a history of travel to Southeast Asia or another endemic region should raise suspicion for gnathostomiasis.1-3,5,7 Unfortunately, confirmatory testing such as Gnathostoma serology is not readily available in the United States, and available serologic tests demonstrate frequent false positives and incomplete crossreactivity.1,2,8 Accordingly, the diagnosis most commonly is solidified by combining cardinal clinical features with histologic findings of a dense eosinophilic inflammatory infiltrate involving the dermis and hypodermis.2,5 In one study, the larva itself was only found in 12 of 66 (18%) skin biopsy specimens from patients with gnathostomiasis.5 If the larva is detected within the sections, it ranges from 2.5 to 12.5 mm in length and 0.4 to 1.2 mm in width and can exhibit cuticular spines, intestinal cells, and characteristic large lateral chords.1,5

The treatment of choice is surgical removal of the worm. Oral albendazole (400–800 mg/d for 21 days) also is considered a first-line treatment and results in clinical cure in approximately 90% of cases. Two doses of oral ivermectin (0.2 mg/kg) spaced 24 to 48 hours apart is an acceptable alternative with comparable efficacy.1-3 Care should be taken if involvement of the central nervous system is suspected, as antihelminthic treatment theoretically could be deleterious due to an inflammatory response to the dying larvae.1,2,9

In the differential diagnosis, loiasis can resemble gnathostomiasis, but the former is endemic to Africa.3 Cutaneous larva migrans most frequently is caused by hookworms from the genus Ancylostoma, which classically leads to superficial serpiginous linear plaques that migrate at a rate of several millimeters per day. However, the larvae are believed to lack the collagenase enzyme required to penetrate the epidermal basement membrane and thus are not capable of producing deep-seated nodules or visceral symptoms.3 Strongyloidiasis (larva currens) generally exhibits a more linear morphology, and infection would result in positive Strongyloides serology.7 Erythema nodosum is a septal panniculitis that can be triggered by infection, pregnancy, medications, connective tissue diseases, inflammatory conditions, and underlying malignancy.10

The Diagnosis: Gnathostomiasis

The biopsy demonstrated a dense, eosinophilic, granulomatous infiltrate surrounding sections of a parasite with skeletal muscle bundles and intestines containing a brush border and luminal debris (Figure), which was consistent with a diagnosis of gnathostomiasis. Upon further questioning, he revealed that while in Peru he frequently consumed ceviche, which is a dish typically made from fresh raw fish cured in lemon or lime juice. He subsequently was treated with oral ivermectin 0.2 mg/kg once daily for 2 days with no evidence of recurrence 12 months later.

Cutaneous gnathostomiasis is the most common manifestation of infection caused by the third-stage larvae of the genus Gnathostoma. The nematode is endemic to tropical and subtropical regions of Japan and Southeast Asia, particularly Thailand. The disease has been increasingly observed in Central and South America. Humans can become infected through ingestion of undercooked meats, particularly freshwater fish but also poultry, snakes, or frogs. Few cases have been reported in North America and Europe presumably due to more stringent regulations governing the sourcing and storage of fish for consumption.1-3 Restaurants in endemic regions also may use cheaper local freshwater or brackish fish compared to restaurants in the West, which use more expensive saltwater fish that do not harbor Gnathostoma species.1 There is a false belief among restauranteurs and consumers that the larvae can be reliably killed by marinating meat in citrus juice or with concurrent consumption of alcohol or hot spices.2 Adequately cooking or freezing meat to 20 °C for 3 to 5 days are the only effective ways to ensure that the larvae are killed.1-3

The parasite requires its natural definitive hosts—fish-eating mammals such as pigs, cats, and dogs—to complete its life cycle and reproduce. Humans are accidental hosts in whom the parasite fails to reach sexual maturity.1-3 Consequently, symptoms commonly are due to the migration of only 1 larva, but occasionally infection with 2 or more has been observed.1,4

Human infection initially may result in malaise, fever, anorexia, abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea as the parasite migrates through the stomach, intestines, and liver. After 2 to 4 weeks, larvae may reach the skin where they most commonly create ill-defined, erythematous, indurated, round or oval plaques or nodules described as nodular migratory panniculitis. These lesions tend to develop on the trunk or arms and correspond to the location of the migrating worm.1,3,5 The larvae have been observed to migrate at 1 cm/h.6 Symptoms often wax and wane, with individual nodules lasting approximately 1 to 2 weeks. Uniquely, larval migration can result in a trail of subcutaneous hemorrhage that is considered pathognomonic and helps to differentiate gnathostomiasis from other forms of parasitosis such as strongyloidiasis and sparganosis.1,3 Larvae are highly motile and invasive, and they are capable of producing a wide range of symptoms affecting virtually any part of the body.1,2 Depending on the anatomic location of the migrating worm, infection also may result in neurologic, gastrointestinal, pulmonary, or ocular symptoms.1-3,7 Eosinophilia is common but can subside in the chronic stage, as seen in our patient.1

The classic triad of intermittent migratory nodules, eosinophilia, and a history of travel to Southeast Asia or another endemic region should raise suspicion for gnathostomiasis.1-3,5,7 Unfortunately, confirmatory testing such as Gnathostoma serology is not readily available in the United States, and available serologic tests demonstrate frequent false positives and incomplete crossreactivity.1,2,8 Accordingly, the diagnosis most commonly is solidified by combining cardinal clinical features with histologic findings of a dense eosinophilic inflammatory infiltrate involving the dermis and hypodermis.2,5 In one study, the larva itself was only found in 12 of 66 (18%) skin biopsy specimens from patients with gnathostomiasis.5 If the larva is detected within the sections, it ranges from 2.5 to 12.5 mm in length and 0.4 to 1.2 mm in width and can exhibit cuticular spines, intestinal cells, and characteristic large lateral chords.1,5

The treatment of choice is surgical removal of the worm. Oral albendazole (400–800 mg/d for 21 days) also is considered a first-line treatment and results in clinical cure in approximately 90% of cases. Two doses of oral ivermectin (0.2 mg/kg) spaced 24 to 48 hours apart is an acceptable alternative with comparable efficacy.1-3 Care should be taken if involvement of the central nervous system is suspected, as antihelminthic treatment theoretically could be deleterious due to an inflammatory response to the dying larvae.1,2,9

In the differential diagnosis, loiasis can resemble gnathostomiasis, but the former is endemic to Africa.3 Cutaneous larva migrans most frequently is caused by hookworms from the genus Ancylostoma, which classically leads to superficial serpiginous linear plaques that migrate at a rate of several millimeters per day. However, the larvae are believed to lack the collagenase enzyme required to penetrate the epidermal basement membrane and thus are not capable of producing deep-seated nodules or visceral symptoms.3 Strongyloidiasis (larva currens) generally exhibits a more linear morphology, and infection would result in positive Strongyloides serology.7 Erythema nodosum is a septal panniculitis that can be triggered by infection, pregnancy, medications, connective tissue diseases, inflammatory conditions, and underlying malignancy.10

- Herman JS, Chiodini PL. Gnathostomiasis, another emerging imported disease. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2009;22:484-492.

- Liu GH, Sun MM, Elsheikha HM, et al. Human gnathostomiasis: a neglected food-borne zoonosis. Parasit Vectors. 2020;13:616.

- Tyring SK. Gnathostomiasis. In: Tyring SK, Lupi O, Hengge UR, eds. Tropical Dermatology. 2nd ed. Elsevier; 2017:77-78.

- Rusnak JM, Lucey DR. Clinical gnathostomiasis: case report and review of the English-language literature. Clin Infect Dis. 1993;16:33-50.

- Magaña M, Messina M, Bustamante F, et al. Gnathostomiasis: clinicopathologic study. Am J Dermatopathol. 2004;26:91-95.

- Chandenier J, Husson J, Canaple S, et al. Medullary gnathostomiasis in a white patient: use of immunodiagnosis and magnetic resonance imaging. Clin Infect Dis. 2001;32:E154-E157.

- Hamilton WL, Agranoff D. Imported gnathostomiasis manifesting as cutaneous larva migrans and Löffler’s syndrome. BMJ Case Rep. 2018;2018:bcr2017223132.

- Neumayr A, Ollague J, Bravo F, et al. Cross-reactivity pattern of Asian and American human gnathostomiasis in western blot assays using crude antigens prepared from Gnathostoma spinigerum and Gnathostoma binucleatum third-stage larvae. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2016;95:413-416.

- Kraivichian K, Nuchprayoon S, Sitichalernchai P, et al. Treatment of cutaneous gnathostomiasis with ivermectin. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2004;71:623-628.

- Pérez-Garza DM, Chavez-Alvarez S, Ocampo-Candiani J, et al. Erythema nodosum: a practical approach and diagnostic algorithm. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2021;22:367-378.

- Herman JS, Chiodini PL. Gnathostomiasis, another emerging imported disease. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2009;22:484-492.

- Liu GH, Sun MM, Elsheikha HM, et al. Human gnathostomiasis: a neglected food-borne zoonosis. Parasit Vectors. 2020;13:616.

- Tyring SK. Gnathostomiasis. In: Tyring SK, Lupi O, Hengge UR, eds. Tropical Dermatology. 2nd ed. Elsevier; 2017:77-78.

- Rusnak JM, Lucey DR. Clinical gnathostomiasis: case report and review of the English-language literature. Clin Infect Dis. 1993;16:33-50.

- Magaña M, Messina M, Bustamante F, et al. Gnathostomiasis: clinicopathologic study. Am J Dermatopathol. 2004;26:91-95.

- Chandenier J, Husson J, Canaple S, et al. Medullary gnathostomiasis in a white patient: use of immunodiagnosis and magnetic resonance imaging. Clin Infect Dis. 2001;32:E154-E157.

- Hamilton WL, Agranoff D. Imported gnathostomiasis manifesting as cutaneous larva migrans and Löffler’s syndrome. BMJ Case Rep. 2018;2018:bcr2017223132.

- Neumayr A, Ollague J, Bravo F, et al. Cross-reactivity pattern of Asian and American human gnathostomiasis in western blot assays using crude antigens prepared from Gnathostoma spinigerum and Gnathostoma binucleatum third-stage larvae. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2016;95:413-416.

- Kraivichian K, Nuchprayoon S, Sitichalernchai P, et al. Treatment of cutaneous gnathostomiasis with ivermectin. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2004;71:623-628.

- Pérez-Garza DM, Chavez-Alvarez S, Ocampo-Candiani J, et al. Erythema nodosum: a practical approach and diagnostic algorithm. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2021;22:367-378.

A 41-year-old man presented to a dermatology clinic in the United States with a migratory subcutaneous nodule overlying the left upper chest that initially developed 12 months prior and continued to migrate along the trunk and proximal aspect of the arms. The patient had spent the last 3 years residing in Peru. He never observed more than 1 nodule at a time and denied associated fever, headache, visual changes, chest pain, cough, abdominal pain, and diarrhea. Laboratory studies including a blood eosinophil count and serum Strongyloides immunoglobulins were within reference range. An excisional biopsy was performed.

Clinical Takeaways in Thrombocytopenia From ASH 2023

The clinical takeaways in immune thrombocytopenia (ITP) from the 2023 American Society of Hematology (ASH) Annual Meeting and Exposition include the relative merits of advanced therapies, efficacy of novel therapies, and infection risk for patients with chronic ITP.

Dr Howard Liebman, of the Keck School of Medicine in Los Angeles, California, opens with a database analysis of patients with primary ITP who were first-time users of advanced therapies, such as rituximab and thrombopoietin (TPO) receptor agonists. The analysis found that despite their relative merits, all the drugs carried a significant risk for adverse events.

Next, he reports on a study examining whether newly diagnosed patients or patients with chronic ITP had better results from the use of avatrombopag, a TPO receptor agonist. Reassuringly, there were no differences in outcomes.

Dr Liebman then discusses the updated results of an ongoing study of rilzabrutinib, a Bruton kinase inhibitor. This analysis showed that the drug achieved rapid, stable, and durable platelet responses.

He next turns to a Danish registry study on infection in patients with chronic ITP, which revealed an ongoing, cumulative risk for infection over 10 years.

Finally, Dr Liebman reports on a study that showed women who develop ITP during pregnancy require more interventions than do women with chronic ITP who become pregnant, and many develop chronic disease after delivery.

--

Howard A. Liebman, MD, Professor of Medicine and Pathology, University of Southern California, Keck School of Medicine; Attending Physician, Department of Medicine, Hematology, Norris Comprehensive Cancer Center, Keck Medicine at University of Southern California, Los Angeles, California

Howard A. Liebman, MD, has disclosed the following relevant financial relationships:

Serve(d) as a consultant for: Novartis; Sanofi; Sobi

Received research grant from: Janssen Pharmaceuticals; Sanofi

The clinical takeaways in immune thrombocytopenia (ITP) from the 2023 American Society of Hematology (ASH) Annual Meeting and Exposition include the relative merits of advanced therapies, efficacy of novel therapies, and infection risk for patients with chronic ITP.

Dr Howard Liebman, of the Keck School of Medicine in Los Angeles, California, opens with a database analysis of patients with primary ITP who were first-time users of advanced therapies, such as rituximab and thrombopoietin (TPO) receptor agonists. The analysis found that despite their relative merits, all the drugs carried a significant risk for adverse events.

Next, he reports on a study examining whether newly diagnosed patients or patients with chronic ITP had better results from the use of avatrombopag, a TPO receptor agonist. Reassuringly, there were no differences in outcomes.

Dr Liebman then discusses the updated results of an ongoing study of rilzabrutinib, a Bruton kinase inhibitor. This analysis showed that the drug achieved rapid, stable, and durable platelet responses.

He next turns to a Danish registry study on infection in patients with chronic ITP, which revealed an ongoing, cumulative risk for infection over 10 years.

Finally, Dr Liebman reports on a study that showed women who develop ITP during pregnancy require more interventions than do women with chronic ITP who become pregnant, and many develop chronic disease after delivery.

--

Howard A. Liebman, MD, Professor of Medicine and Pathology, University of Southern California, Keck School of Medicine; Attending Physician, Department of Medicine, Hematology, Norris Comprehensive Cancer Center, Keck Medicine at University of Southern California, Los Angeles, California

Howard A. Liebman, MD, has disclosed the following relevant financial relationships:

Serve(d) as a consultant for: Novartis; Sanofi; Sobi

Received research grant from: Janssen Pharmaceuticals; Sanofi

The clinical takeaways in immune thrombocytopenia (ITP) from the 2023 American Society of Hematology (ASH) Annual Meeting and Exposition include the relative merits of advanced therapies, efficacy of novel therapies, and infection risk for patients with chronic ITP.

Dr Howard Liebman, of the Keck School of Medicine in Los Angeles, California, opens with a database analysis of patients with primary ITP who were first-time users of advanced therapies, such as rituximab and thrombopoietin (TPO) receptor agonists. The analysis found that despite their relative merits, all the drugs carried a significant risk for adverse events.

Next, he reports on a study examining whether newly diagnosed patients or patients with chronic ITP had better results from the use of avatrombopag, a TPO receptor agonist. Reassuringly, there were no differences in outcomes.

Dr Liebman then discusses the updated results of an ongoing study of rilzabrutinib, a Bruton kinase inhibitor. This analysis showed that the drug achieved rapid, stable, and durable platelet responses.

He next turns to a Danish registry study on infection in patients with chronic ITP, which revealed an ongoing, cumulative risk for infection over 10 years.

Finally, Dr Liebman reports on a study that showed women who develop ITP during pregnancy require more interventions than do women with chronic ITP who become pregnant, and many develop chronic disease after delivery.

--

Howard A. Liebman, MD, Professor of Medicine and Pathology, University of Southern California, Keck School of Medicine; Attending Physician, Department of Medicine, Hematology, Norris Comprehensive Cancer Center, Keck Medicine at University of Southern California, Los Angeles, California

Howard A. Liebman, MD, has disclosed the following relevant financial relationships:

Serve(d) as a consultant for: Novartis; Sanofi; Sobi

Received research grant from: Janssen Pharmaceuticals; Sanofi

Commentary: Risks for Eosinophilic Esophagitis: IBD, Eczema, Diet, and Acid Suppressants, January 2024

Although there exists a recognized association between IBD and secondary EoE diagnoses, studies focusing on the primary diagnosis of EoE alongside IBD have yielded conflicting results. Dr Amiko Uchida, from the University of Utah Department of Medicine, working with colleagues from the Department of Medical Epidemiology and Biostatistics at Karolinska Institutet in Stockholm, Sweden, led by Dr Jonas F. Ludvigsson, conducted a comprehensive study spanning 1990-2019 to explore the relationship between these two diseases.

Dr Uchida and colleagues assessed the association among Swedish patients diagnosed with biopsy-verified EoE (n = 1587) between 1990 and 2017. These patients were age- and sex-matched with up to five reference individuals from the general population (n = 7808). The primary focus was to discern the relationship between the primary diagnosis of EoE and the subsequent diagnosis of IBD.

The study's findings underscore the importance of heightened awareness among healthcare professionals regarding the potential association between EoE and the development of subsequent IBD. Collaborative efforts between physicians, gastroenterologists, and specialists in allergic diseases are crucial to ensure comprehensive care and timely identification of gastrointestinal complications in patients with EoE.

These results indicate a potential interplay between EoE and the pathogenesis of IBD, particularly Crohn's disease. In patients with EoE, careful consideration of gastrointestinal symptoms suggestive of IBD, such as abdominal pain, diarrhea, and rectal bleeding, is pivotal, necessitating further evaluation and appropriate monitoring for early detection and management of IBD.

Upon diagnosis, clinicians must develop a management plan for this chronic and critical disease. This study aids in planning future screenings for these patients, because one third of those diagnosed with EoE are at risk of developing IBD within a year. Therefore, primary physicians must remain vigilant for the development of gastrointestinal symptoms leading to a diagnosis of Crohn's disease or ulcerative colitis. Additionally, family awareness is crucial owing to observed associations between siblings, suggesting a potential role of genetics or early environmental factors in EoE development and future IBD diagnoses.

Further research is necessary to elucidate the shared pathophysiologic mechanisms connecting EoE and IBD. It is important to consider certain details, however; for instance, 31% of all subsequent IBD cases were diagnosed within the first year after an EoE diagnosis, potentially indicating a role of detection bias in these findings. Using a validated nationwide cohort and comparing study individuals with their siblings helped control for potential intrafamilial confounders as well as some environmental confounders, minimizing such biases as selection bias due to socioeconomic status. This strengthens the observed association in this study.

These insights into the increased risk for IBD, notably Crohn's disease, among patients with EoE underscore the need for thorough clinical evaluation and vigilant monitoring for gastrointestinal complications in this population.

A retrospective study conducted in pediatric patients presenting with an aerodigestive manifestation aimed to assess the factors associated with EoE and the diagnostic role of triple endoscopy. The results suggested a potential association between a family history of eczema and a diet lacking allergenic foods with a future diagnosis of EoE.

This study by Sheila Moran and colleagues, led by Dr Christina J. Yang from the Department of Otorhinolaryngology, Head and Neck Surgery at the Albert Einstein College of Medicine, Bronx, New York, aimed to identify preoperative risk factors linked to an EoE diagnosis in children undergoing triple endoscopy. They evaluated 119 pediatric patients aged 0-21 years who underwent triple endoscopy (including flexible bronchoscopy, rigid direct laryngoscopy and bronchoscopy, and esophagoscopy with biopsy) at the Children's Hospital at Montefiore between January 1, 2015, and December 31, 2019.

The study underscored the significance of both genetic predisposition and dietary influences in EoE development. Understanding the interplay between familial atopic conditions and dietary choices among pediatric patients with aerodigestive dysfunction is crucial for early identification and implementing preventive strategies against EoE.

As clinicians, it's essential to consider rare diseases like EoE when patients present with mixed symptoms, including aerodigestive symptoms, a family history of eczema, and a history of environmental allergies, given the association between these conditions. The potential link between a family history of eczema and increased EoE risk suggests a shared genetic susceptibility among allergic conditions. Therefore, clinicians evaluating children with aerodigestive dysfunction, particularly those with a familial history of eczema, should maintain a high index of suspicion for EoE, prompting vigilant monitoring and appropriate diagnostic assessments.

When contemplating advanced procedures, such as triple endoscopy or biopsy sampling, considering the patient's previous medical history and the effect of dietary modifications, such as incorporating or excluding dairy from the diet, warrants further investigation in the context of EoE prevention. Clinicians should consider providing dietary counseling and personalized nutritional plans based on evidence-based approaches to potentially mitigate EoE risk in susceptible pediatric populations.

Additionally, it's crucial to consider EoE in minority racial groups and underserved communities and encourage the use of diagnostic tests, such as triple endoscopy, to facilitate early diagnosis. Healthcare providers should contemplate integrating family history assessments, particularly regarding eczema, into the evaluation of children with aerodigestive dysfunction. This information can assist in risk assessment and early identification of individuals at a higher risk of developing EoE, enabling prompt intervention and management.

The increasing incidence of EoE across different nations, including the United States, has underscored the need for a deeper understanding of its causes, early diagnosis, and treatment. A novel population-based study conducted in Denmark aimed to explore the relationship between maternal and infant use of antibiotics and acid suppressants in the development of EoE. The study yielded significant results based on a population of 392 cases. Dr Elizabeth T. Jensen, MPH, PhD, from the Department of Epidemiology & Prevention at Wake Forest University School of Medicine, Winston-Salem, North Carolina, conducted a comprehensive study spanning the last 20 years to decipher potential causes contributing to the rising incidence of EoE.

Dr Jensen and her colleagues evaluated the association between maternal and infant use of antibiotics and acid suppressants in Denmark. They used pathology, prescription, birth, inpatient, and outpatient health registry data, ensuring complete ascertainment of all EoE cases among Danish residents born between 1997 and 2018. The research obtained a census of cases from a registered sample of approximately 1.4 million children, matching EoE cases to controls using a 1:10 ratio through incidence density sampling. A total of 392 patients with EoE and 3637 control patients were enrolled. The primary outcome of the study focused on the development of EoE, revealing a dose-response association between maternal and infant antibiotic and acid suppressant use and increased EoE risk.

This study demonstrated a robust correlation between the dosage of antibiotics and acid suppressants and the development of EoE in offspring during childhood. These findings hold significance because these medications represent some of the most common prescriptions in clinical practice. Pregnancy triggers significant physiologic changes in women, including increased hormonal effects and abdominal pressure on the lower esophageal sphincter, making pregnant individuals more prone to esophageal reflux and necessitating the use of gastric acid suppressants. As clinicians, it's crucial to consider lifestyle modifications and dietary adjustments before resorting to acid suppressants, reserving their use for only when absolutely necessary.

Postpregnancy, emphasizing exclusive breastfeeding for the first 6 months and proper feeding techniques can aid in reducing the likelihood of reflux disease in newborns. Acid suppressants have been linked to alterations in infant microbiome colonization, potentially increasing the susceptibility to immunoreactive diseases, such as asthma, atopic dermatitis, and allergic rhinitis. Given that exclusive breastfeeding in the initial 6 months has demonstrated preventive benefits against such diseases, primary physicians play a crucial role in advocating its importance. Although gastric acid suppressants and antibiotics are essential for managing various health conditions, including infections and gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD), their potential impact on EoE development should not be overlooked.

Though this study had a relatively small sample size, the strong population registry of Denmark significantly reduced recall bias. However, cultural differences and over-the-counter access to drugs, such as acid suppressants, in other countries, including the United States, warrant further research to ascertain their effect on EoE development.

In light of these findings, clinicians should carefully weigh the risks and benefits of prescribing antibiotics and acid suppressants during pregnancy and infancy. Adherence to evidence-based guidelines and considering alternative treatment options, such as lifestyle modifications, should be prioritized. Prescribing antibiotics only when medically necessary and using nonpharmacologic strategies for managing GERD in infants should be considered to mitigate potential risks associated with these medications.

Although there exists a recognized association between IBD and secondary EoE diagnoses, studies focusing on the primary diagnosis of EoE alongside IBD have yielded conflicting results. Dr Amiko Uchida, from the University of Utah Department of Medicine, working with colleagues from the Department of Medical Epidemiology and Biostatistics at Karolinska Institutet in Stockholm, Sweden, led by Dr Jonas F. Ludvigsson, conducted a comprehensive study spanning 1990-2019 to explore the relationship between these two diseases.

Dr Uchida and colleagues assessed the association among Swedish patients diagnosed with biopsy-verified EoE (n = 1587) between 1990 and 2017. These patients were age- and sex-matched with up to five reference individuals from the general population (n = 7808). The primary focus was to discern the relationship between the primary diagnosis of EoE and the subsequent diagnosis of IBD.

The study's findings underscore the importance of heightened awareness among healthcare professionals regarding the potential association between EoE and the development of subsequent IBD. Collaborative efforts between physicians, gastroenterologists, and specialists in allergic diseases are crucial to ensure comprehensive care and timely identification of gastrointestinal complications in patients with EoE.

These results indicate a potential interplay between EoE and the pathogenesis of IBD, particularly Crohn's disease. In patients with EoE, careful consideration of gastrointestinal symptoms suggestive of IBD, such as abdominal pain, diarrhea, and rectal bleeding, is pivotal, necessitating further evaluation and appropriate monitoring for early detection and management of IBD.

Upon diagnosis, clinicians must develop a management plan for this chronic and critical disease. This study aids in planning future screenings for these patients, because one third of those diagnosed with EoE are at risk of developing IBD within a year. Therefore, primary physicians must remain vigilant for the development of gastrointestinal symptoms leading to a diagnosis of Crohn's disease or ulcerative colitis. Additionally, family awareness is crucial owing to observed associations between siblings, suggesting a potential role of genetics or early environmental factors in EoE development and future IBD diagnoses.

Further research is necessary to elucidate the shared pathophysiologic mechanisms connecting EoE and IBD. It is important to consider certain details, however; for instance, 31% of all subsequent IBD cases were diagnosed within the first year after an EoE diagnosis, potentially indicating a role of detection bias in these findings. Using a validated nationwide cohort and comparing study individuals with their siblings helped control for potential intrafamilial confounders as well as some environmental confounders, minimizing such biases as selection bias due to socioeconomic status. This strengthens the observed association in this study.

These insights into the increased risk for IBD, notably Crohn's disease, among patients with EoE underscore the need for thorough clinical evaluation and vigilant monitoring for gastrointestinal complications in this population.

A retrospective study conducted in pediatric patients presenting with an aerodigestive manifestation aimed to assess the factors associated with EoE and the diagnostic role of triple endoscopy. The results suggested a potential association between a family history of eczema and a diet lacking allergenic foods with a future diagnosis of EoE.

This study by Sheila Moran and colleagues, led by Dr Christina J. Yang from the Department of Otorhinolaryngology, Head and Neck Surgery at the Albert Einstein College of Medicine, Bronx, New York, aimed to identify preoperative risk factors linked to an EoE diagnosis in children undergoing triple endoscopy. They evaluated 119 pediatric patients aged 0-21 years who underwent triple endoscopy (including flexible bronchoscopy, rigid direct laryngoscopy and bronchoscopy, and esophagoscopy with biopsy) at the Children's Hospital at Montefiore between January 1, 2015, and December 31, 2019.

The study underscored the significance of both genetic predisposition and dietary influences in EoE development. Understanding the interplay between familial atopic conditions and dietary choices among pediatric patients with aerodigestive dysfunction is crucial for early identification and implementing preventive strategies against EoE.

As clinicians, it's essential to consider rare diseases like EoE when patients present with mixed symptoms, including aerodigestive symptoms, a family history of eczema, and a history of environmental allergies, given the association between these conditions. The potential link between a family history of eczema and increased EoE risk suggests a shared genetic susceptibility among allergic conditions. Therefore, clinicians evaluating children with aerodigestive dysfunction, particularly those with a familial history of eczema, should maintain a high index of suspicion for EoE, prompting vigilant monitoring and appropriate diagnostic assessments.

When contemplating advanced procedures, such as triple endoscopy or biopsy sampling, considering the patient's previous medical history and the effect of dietary modifications, such as incorporating or excluding dairy from the diet, warrants further investigation in the context of EoE prevention. Clinicians should consider providing dietary counseling and personalized nutritional plans based on evidence-based approaches to potentially mitigate EoE risk in susceptible pediatric populations.

Additionally, it's crucial to consider EoE in minority racial groups and underserved communities and encourage the use of diagnostic tests, such as triple endoscopy, to facilitate early diagnosis. Healthcare providers should contemplate integrating family history assessments, particularly regarding eczema, into the evaluation of children with aerodigestive dysfunction. This information can assist in risk assessment and early identification of individuals at a higher risk of developing EoE, enabling prompt intervention and management.

The increasing incidence of EoE across different nations, including the United States, has underscored the need for a deeper understanding of its causes, early diagnosis, and treatment. A novel population-based study conducted in Denmark aimed to explore the relationship between maternal and infant use of antibiotics and acid suppressants in the development of EoE. The study yielded significant results based on a population of 392 cases. Dr Elizabeth T. Jensen, MPH, PhD, from the Department of Epidemiology & Prevention at Wake Forest University School of Medicine, Winston-Salem, North Carolina, conducted a comprehensive study spanning the last 20 years to decipher potential causes contributing to the rising incidence of EoE.

Dr Jensen and her colleagues evaluated the association between maternal and infant use of antibiotics and acid suppressants in Denmark. They used pathology, prescription, birth, inpatient, and outpatient health registry data, ensuring complete ascertainment of all EoE cases among Danish residents born between 1997 and 2018. The research obtained a census of cases from a registered sample of approximately 1.4 million children, matching EoE cases to controls using a 1:10 ratio through incidence density sampling. A total of 392 patients with EoE and 3637 control patients were enrolled. The primary outcome of the study focused on the development of EoE, revealing a dose-response association between maternal and infant antibiotic and acid suppressant use and increased EoE risk.

This study demonstrated a robust correlation between the dosage of antibiotics and acid suppressants and the development of EoE in offspring during childhood. These findings hold significance because these medications represent some of the most common prescriptions in clinical practice. Pregnancy triggers significant physiologic changes in women, including increased hormonal effects and abdominal pressure on the lower esophageal sphincter, making pregnant individuals more prone to esophageal reflux and necessitating the use of gastric acid suppressants. As clinicians, it's crucial to consider lifestyle modifications and dietary adjustments before resorting to acid suppressants, reserving their use for only when absolutely necessary.

Postpregnancy, emphasizing exclusive breastfeeding for the first 6 months and proper feeding techniques can aid in reducing the likelihood of reflux disease in newborns. Acid suppressants have been linked to alterations in infant microbiome colonization, potentially increasing the susceptibility to immunoreactive diseases, such as asthma, atopic dermatitis, and allergic rhinitis. Given that exclusive breastfeeding in the initial 6 months has demonstrated preventive benefits against such diseases, primary physicians play a crucial role in advocating its importance. Although gastric acid suppressants and antibiotics are essential for managing various health conditions, including infections and gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD), their potential impact on EoE development should not be overlooked.

Though this study had a relatively small sample size, the strong population registry of Denmark significantly reduced recall bias. However, cultural differences and over-the-counter access to drugs, such as acid suppressants, in other countries, including the United States, warrant further research to ascertain their effect on EoE development.

In light of these findings, clinicians should carefully weigh the risks and benefits of prescribing antibiotics and acid suppressants during pregnancy and infancy. Adherence to evidence-based guidelines and considering alternative treatment options, such as lifestyle modifications, should be prioritized. Prescribing antibiotics only when medically necessary and using nonpharmacologic strategies for managing GERD in infants should be considered to mitigate potential risks associated with these medications.

Although there exists a recognized association between IBD and secondary EoE diagnoses, studies focusing on the primary diagnosis of EoE alongside IBD have yielded conflicting results. Dr Amiko Uchida, from the University of Utah Department of Medicine, working with colleagues from the Department of Medical Epidemiology and Biostatistics at Karolinska Institutet in Stockholm, Sweden, led by Dr Jonas F. Ludvigsson, conducted a comprehensive study spanning 1990-2019 to explore the relationship between these two diseases.

Dr Uchida and colleagues assessed the association among Swedish patients diagnosed with biopsy-verified EoE (n = 1587) between 1990 and 2017. These patients were age- and sex-matched with up to five reference individuals from the general population (n = 7808). The primary focus was to discern the relationship between the primary diagnosis of EoE and the subsequent diagnosis of IBD.

The study's findings underscore the importance of heightened awareness among healthcare professionals regarding the potential association between EoE and the development of subsequent IBD. Collaborative efforts between physicians, gastroenterologists, and specialists in allergic diseases are crucial to ensure comprehensive care and timely identification of gastrointestinal complications in patients with EoE.

These results indicate a potential interplay between EoE and the pathogenesis of IBD, particularly Crohn's disease. In patients with EoE, careful consideration of gastrointestinal symptoms suggestive of IBD, such as abdominal pain, diarrhea, and rectal bleeding, is pivotal, necessitating further evaluation and appropriate monitoring for early detection and management of IBD.

Upon diagnosis, clinicians must develop a management plan for this chronic and critical disease. This study aids in planning future screenings for these patients, because one third of those diagnosed with EoE are at risk of developing IBD within a year. Therefore, primary physicians must remain vigilant for the development of gastrointestinal symptoms leading to a diagnosis of Crohn's disease or ulcerative colitis. Additionally, family awareness is crucial owing to observed associations between siblings, suggesting a potential role of genetics or early environmental factors in EoE development and future IBD diagnoses.

Further research is necessary to elucidate the shared pathophysiologic mechanisms connecting EoE and IBD. It is important to consider certain details, however; for instance, 31% of all subsequent IBD cases were diagnosed within the first year after an EoE diagnosis, potentially indicating a role of detection bias in these findings. Using a validated nationwide cohort and comparing study individuals with their siblings helped control for potential intrafamilial confounders as well as some environmental confounders, minimizing such biases as selection bias due to socioeconomic status. This strengthens the observed association in this study.

These insights into the increased risk for IBD, notably Crohn's disease, among patients with EoE underscore the need for thorough clinical evaluation and vigilant monitoring for gastrointestinal complications in this population.

A retrospective study conducted in pediatric patients presenting with an aerodigestive manifestation aimed to assess the factors associated with EoE and the diagnostic role of triple endoscopy. The results suggested a potential association between a family history of eczema and a diet lacking allergenic foods with a future diagnosis of EoE.

This study by Sheila Moran and colleagues, led by Dr Christina J. Yang from the Department of Otorhinolaryngology, Head and Neck Surgery at the Albert Einstein College of Medicine, Bronx, New York, aimed to identify preoperative risk factors linked to an EoE diagnosis in children undergoing triple endoscopy. They evaluated 119 pediatric patients aged 0-21 years who underwent triple endoscopy (including flexible bronchoscopy, rigid direct laryngoscopy and bronchoscopy, and esophagoscopy with biopsy) at the Children's Hospital at Montefiore between January 1, 2015, and December 31, 2019.

The study underscored the significance of both genetic predisposition and dietary influences in EoE development. Understanding the interplay between familial atopic conditions and dietary choices among pediatric patients with aerodigestive dysfunction is crucial for early identification and implementing preventive strategies against EoE.

As clinicians, it's essential to consider rare diseases like EoE when patients present with mixed symptoms, including aerodigestive symptoms, a family history of eczema, and a history of environmental allergies, given the association between these conditions. The potential link between a family history of eczema and increased EoE risk suggests a shared genetic susceptibility among allergic conditions. Therefore, clinicians evaluating children with aerodigestive dysfunction, particularly those with a familial history of eczema, should maintain a high index of suspicion for EoE, prompting vigilant monitoring and appropriate diagnostic assessments.

When contemplating advanced procedures, such as triple endoscopy or biopsy sampling, considering the patient's previous medical history and the effect of dietary modifications, such as incorporating or excluding dairy from the diet, warrants further investigation in the context of EoE prevention. Clinicians should consider providing dietary counseling and personalized nutritional plans based on evidence-based approaches to potentially mitigate EoE risk in susceptible pediatric populations.

Additionally, it's crucial to consider EoE in minority racial groups and underserved communities and encourage the use of diagnostic tests, such as triple endoscopy, to facilitate early diagnosis. Healthcare providers should contemplate integrating family history assessments, particularly regarding eczema, into the evaluation of children with aerodigestive dysfunction. This information can assist in risk assessment and early identification of individuals at a higher risk of developing EoE, enabling prompt intervention and management.

The increasing incidence of EoE across different nations, including the United States, has underscored the need for a deeper understanding of its causes, early diagnosis, and treatment. A novel population-based study conducted in Denmark aimed to explore the relationship between maternal and infant use of antibiotics and acid suppressants in the development of EoE. The study yielded significant results based on a population of 392 cases. Dr Elizabeth T. Jensen, MPH, PhD, from the Department of Epidemiology & Prevention at Wake Forest University School of Medicine, Winston-Salem, North Carolina, conducted a comprehensive study spanning the last 20 years to decipher potential causes contributing to the rising incidence of EoE.

Dr Jensen and her colleagues evaluated the association between maternal and infant use of antibiotics and acid suppressants in Denmark. They used pathology, prescription, birth, inpatient, and outpatient health registry data, ensuring complete ascertainment of all EoE cases among Danish residents born between 1997 and 2018. The research obtained a census of cases from a registered sample of approximately 1.4 million children, matching EoE cases to controls using a 1:10 ratio through incidence density sampling. A total of 392 patients with EoE and 3637 control patients were enrolled. The primary outcome of the study focused on the development of EoE, revealing a dose-response association between maternal and infant antibiotic and acid suppressant use and increased EoE risk.

This study demonstrated a robust correlation between the dosage of antibiotics and acid suppressants and the development of EoE in offspring during childhood. These findings hold significance because these medications represent some of the most common prescriptions in clinical practice. Pregnancy triggers significant physiologic changes in women, including increased hormonal effects and abdominal pressure on the lower esophageal sphincter, making pregnant individuals more prone to esophageal reflux and necessitating the use of gastric acid suppressants. As clinicians, it's crucial to consider lifestyle modifications and dietary adjustments before resorting to acid suppressants, reserving their use for only when absolutely necessary.

Postpregnancy, emphasizing exclusive breastfeeding for the first 6 months and proper feeding techniques can aid in reducing the likelihood of reflux disease in newborns. Acid suppressants have been linked to alterations in infant microbiome colonization, potentially increasing the susceptibility to immunoreactive diseases, such as asthma, atopic dermatitis, and allergic rhinitis. Given that exclusive breastfeeding in the initial 6 months has demonstrated preventive benefits against such diseases, primary physicians play a crucial role in advocating its importance. Although gastric acid suppressants and antibiotics are essential for managing various health conditions, including infections and gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD), their potential impact on EoE development should not be overlooked.

Though this study had a relatively small sample size, the strong population registry of Denmark significantly reduced recall bias. However, cultural differences and over-the-counter access to drugs, such as acid suppressants, in other countries, including the United States, warrant further research to ascertain their effect on EoE development.

In light of these findings, clinicians should carefully weigh the risks and benefits of prescribing antibiotics and acid suppressants during pregnancy and infancy. Adherence to evidence-based guidelines and considering alternative treatment options, such as lifestyle modifications, should be prioritized. Prescribing antibiotics only when medically necessary and using nonpharmacologic strategies for managing GERD in infants should be considered to mitigate potential risks associated with these medications.

Commentary: Fertility Concerns and Treatment-Related QOL After Breast Cancer, January 2024

Young women diagnosed with breast cancer have been shown to experience higher rates of symptoms that may adversely affect quality of life (QOL), including depression, weight gain, vasomotor symptoms, and sexual dysfunction; they may also have a harder time managing these issues.3 Chemotherapy-related amenorrhea (CRA) is one of the side effects of breast cancer treatment that can affect premenopausal women, and is associated with both patient- (age, body mass index) and treatment-related (regimen, duration) factors.4 A study analyzing data derived from the prospective, longitudinal Cancer Toxicities Study included 1636 premenopausal women ≤ 50 years of age with stage I-III breast cancer treated with chemotherapy but not receiving ovarian suppression (Kabirian et al). A total of 83.0% of women reported CRA at year 1, 72.5% at year 2, and 66.1% at year 4. A higher likelihood of CRA was observed for women of older age vs those age 18-34 years (adjusted odds ratio [aOR] for 35-39 years 1.84; 40-44 years 5.90; and ≥ 45 years 21.29; P < .001 for all), those who received adjuvant tamoxifen (aOR 1.97; P < .001), and those who had hot flashes at baseline (aOR 1.83; P = .01). In the QOL analysis, 57.1% reported no recovery of menses. Persistent CRA was associated with worse insomnia, more systemic therapy–related adverse effects, and worse sexual functioning. These findings highlight the importance of identifying and discussing CRA with our patients, as this can have both physical and psychological effects in the survivorship setting.