User login

Is the doctor in?

Within hospital medicine, there has been a recent increase in programs that provide virtual or telehealth hospitalists, primarily to hospitals that are small, remote, and/or understaffed. According to a 2013 Cisco health care customer experience report, the number of telehealth consumers will likely markedly increase to at least 7 million by 2018.1

Since telehospitalist programs are still relatively new, there are many questions about why and how they exist and how they are (and can be) funded. Questions also remain about some limitations of telehospitalist programs for both the “givers” and the “receivers” of the services. I tackle some of these questions in this article.

What is a telehospitalist?

What are the drivers of telehospitalist programs?

One primary driver of telehealth (and specifically telehospitalist) programs is an ongoing shortage of hospitalists, especially in remote areas and critical access hospitals where coverage issues are especially prominent at night and/or on weekends. In many hospitals, there is also a growing unwillingness on the part of physicians to be routinely on call at night. Although working on call used to be on par with being a physician, many younger-generation physicians are less willing to blur “work and life.” This increases the need for dedicated night coverage in many hospitals.

Another driver for some programs (especially at tertiary care medical centers) is a desire to more thoroughly assess patients prior to transfer to their respective centers (the alternative being a phone conversation with the transferring center about the patient’s status). There is also a growing desire to keep patients local if possible, which is usually better for the patient and the family and can decrease the total cost of their care.

Another catalyst to telehospitalist program growth is the growing cultural comfort level with two-way video interactions, such as Skype and FaceTime. Since videoconferencing has permeated most of our professional and personal lives, telehealth seems familiar and comfortable for both providers and patients. In a recent consumer survey, three out of every four consumers responded that they are very comfortable communicating with providers via technology, as opposed to seeing them in person.1

Another driver for some programs is financial. Depending on the way the program is structured, it can be not only financially feasible but financially beneficial, especially if the program can consolidate coverage across multiple sites (more on this later).

One other driver for some health care systems is the need to cover areas with on-site nurse practitioners and physician assistants. Using a telehospitalist makes it easier to get appropriate and required oversight for this coverage model across time and space.

What are the advantages of being a telehospitalist?

Some of the career advantages of being a telehospitalist include the shift flexibility and convenience. This work allows a hospitalist to serve a shift from anywhere in the world and from the convenience of their home. Some telehospitalists can easily work local night shifts when they live many time zones away (and therefore, don’t actually have to work a night shift). Many programs are designed to have a single hospitalist cover many hospitals over a wide geography, which would be logistically impossible to do in person. This is especially appealing for multihospital systems that cannot afford to have a hospitalist on site at each location.

The earning potential can also be appealing, depending on the number of shifts a hospitalist is willing to work.

What are the limitations of being a telehospitalist?

There are limits to what a telehospitalist can perform, many of which depend on the manner in which the program and the technology are arranged. Telehealth can vary from a cart-based videoconferencing system that is transported into a patient’s room to an independent robot that travels throughout sites. The primary limitation is the need to rely on someone in the patient’s room to act as virtual hands. This usually falls to the bedside nurse and requires a good working relationship and patience on their part. The bedside nurses have to “buy into” the program in advance and may need to have scripting for how to explain the process to the patients.

Another major challenge is interacting with different electronic health record systems. Becoming agile with a single EHR is challenging enough, but maneuvering several of them in a single shift can be extremely trying. Telehospitalists can also be challenged by technology glitches or failures that need troubleshooting both on their end and on-site. Although these problems are rare, there will always be a concern that the patient will not get his or her needs met if the technology fails.

How does the financing work?

Although this is a rapidly changing landscape, telehospitalists are not currently able to generate much revenue from professional billing. Unlike in-person visits, Medicare will not reimburse professional fees for telehospitalist visits. Although each payer is unique, most other (nonMedicare) payers are also not willing to reimburse for televisits. This may change in the future, however, as Medicare does pay for virtual specialty services such as telestroke. In addition, many states have enacted telemedicine parity laws, which require private payers to pay for all health care services equally, regardless of modality (audio, video, or in person).

For now, the financial case for employing telehospitalists for most programs has to be made using benfits other than the generation of professional fees. For telehospitalist programs that can cover several sites, the cost is substantially less than employing individual on-site hospitalists to do low-volume work. Telehospitalist programs are also, likely, less costly than is locum tenens staffing. For programs that evaluate the need for transfers, a case can be made that keeping a patient in a smaller, low-cost venue, rather than transferring them to a larger, higher-cost venue, can also reduce overall cost for a health care system.

What about licensing and credentialing?

Telehospitalists can be hindered by the need to have a license in several states and to be credentialed in several systems. This can be cumbersome, time-consuming, and expensive. To ease the multistate licensing burden, the Interstate Medical Licensure Compact has been established.2 This is an accelerated licensure process for eligible physicians that improves license portability across states. There are currently 18 states that participate, and the number continues to increase.

For credentialing, most hospitals require initial credentialing and full recredentialing every 2 years. Maintaining credentials at several sites can be extremely time consuming. To ease this burden, some hospitals with telehealth programs have adopted “credentialing by proxy,” which means that one hospital will accept the credentialing process of another facility.

What next?

In summary, there has been and will likely continue to be explosive growth of telehospitalist programs and providers for all the reasons outlined above. Although some barriers to efficient and effective practice do exist, many of those barriers are being overcome quite rapidly. I expect this growth to continue for the betterment of hospitalists, our patients, and the systems in which we work. For a more in-depth look into telemedicine in hospital medicine, view a report created by a work group of SHM's Practice Management Committee.

Dr. Scheurer is a hospitalist and chief quality officer at the Medical University of South Carolina in Charleston. She is physician editor of The Hospitalist. Email her at [email protected].

References

1.Cisco. (2013 March 4). Cisco Study Reveals 74 Percent of Consumers Open to Virtual Doctor Visit. Cisco: The Network. Retrieved from https://newsroom.cisco.com/press-release-content?type=webcontent&articleId=1148539.

2. Interstate Medical Licensure Compact Commission. (2017). Interstate Medical Licensure Compact. Retrieved from http://www.licenseportability.org/index.html.

Within hospital medicine, there has been a recent increase in programs that provide virtual or telehealth hospitalists, primarily to hospitals that are small, remote, and/or understaffed. According to a 2013 Cisco health care customer experience report, the number of telehealth consumers will likely markedly increase to at least 7 million by 2018.1

Since telehospitalist programs are still relatively new, there are many questions about why and how they exist and how they are (and can be) funded. Questions also remain about some limitations of telehospitalist programs for both the “givers” and the “receivers” of the services. I tackle some of these questions in this article.

What is a telehospitalist?

What are the drivers of telehospitalist programs?

One primary driver of telehealth (and specifically telehospitalist) programs is an ongoing shortage of hospitalists, especially in remote areas and critical access hospitals where coverage issues are especially prominent at night and/or on weekends. In many hospitals, there is also a growing unwillingness on the part of physicians to be routinely on call at night. Although working on call used to be on par with being a physician, many younger-generation physicians are less willing to blur “work and life.” This increases the need for dedicated night coverage in many hospitals.

Another driver for some programs (especially at tertiary care medical centers) is a desire to more thoroughly assess patients prior to transfer to their respective centers (the alternative being a phone conversation with the transferring center about the patient’s status). There is also a growing desire to keep patients local if possible, which is usually better for the patient and the family and can decrease the total cost of their care.

Another catalyst to telehospitalist program growth is the growing cultural comfort level with two-way video interactions, such as Skype and FaceTime. Since videoconferencing has permeated most of our professional and personal lives, telehealth seems familiar and comfortable for both providers and patients. In a recent consumer survey, three out of every four consumers responded that they are very comfortable communicating with providers via technology, as opposed to seeing them in person.1

Another driver for some programs is financial. Depending on the way the program is structured, it can be not only financially feasible but financially beneficial, especially if the program can consolidate coverage across multiple sites (more on this later).

One other driver for some health care systems is the need to cover areas with on-site nurse practitioners and physician assistants. Using a telehospitalist makes it easier to get appropriate and required oversight for this coverage model across time and space.

What are the advantages of being a telehospitalist?

Some of the career advantages of being a telehospitalist include the shift flexibility and convenience. This work allows a hospitalist to serve a shift from anywhere in the world and from the convenience of their home. Some telehospitalists can easily work local night shifts when they live many time zones away (and therefore, don’t actually have to work a night shift). Many programs are designed to have a single hospitalist cover many hospitals over a wide geography, which would be logistically impossible to do in person. This is especially appealing for multihospital systems that cannot afford to have a hospitalist on site at each location.

The earning potential can also be appealing, depending on the number of shifts a hospitalist is willing to work.

What are the limitations of being a telehospitalist?

There are limits to what a telehospitalist can perform, many of which depend on the manner in which the program and the technology are arranged. Telehealth can vary from a cart-based videoconferencing system that is transported into a patient’s room to an independent robot that travels throughout sites. The primary limitation is the need to rely on someone in the patient’s room to act as virtual hands. This usually falls to the bedside nurse and requires a good working relationship and patience on their part. The bedside nurses have to “buy into” the program in advance and may need to have scripting for how to explain the process to the patients.

Another major challenge is interacting with different electronic health record systems. Becoming agile with a single EHR is challenging enough, but maneuvering several of them in a single shift can be extremely trying. Telehospitalists can also be challenged by technology glitches or failures that need troubleshooting both on their end and on-site. Although these problems are rare, there will always be a concern that the patient will not get his or her needs met if the technology fails.

How does the financing work?

Although this is a rapidly changing landscape, telehospitalists are not currently able to generate much revenue from professional billing. Unlike in-person visits, Medicare will not reimburse professional fees for telehospitalist visits. Although each payer is unique, most other (nonMedicare) payers are also not willing to reimburse for televisits. This may change in the future, however, as Medicare does pay for virtual specialty services such as telestroke. In addition, many states have enacted telemedicine parity laws, which require private payers to pay for all health care services equally, regardless of modality (audio, video, or in person).

For now, the financial case for employing telehospitalists for most programs has to be made using benfits other than the generation of professional fees. For telehospitalist programs that can cover several sites, the cost is substantially less than employing individual on-site hospitalists to do low-volume work. Telehospitalist programs are also, likely, less costly than is locum tenens staffing. For programs that evaluate the need for transfers, a case can be made that keeping a patient in a smaller, low-cost venue, rather than transferring them to a larger, higher-cost venue, can also reduce overall cost for a health care system.

What about licensing and credentialing?

Telehospitalists can be hindered by the need to have a license in several states and to be credentialed in several systems. This can be cumbersome, time-consuming, and expensive. To ease the multistate licensing burden, the Interstate Medical Licensure Compact has been established.2 This is an accelerated licensure process for eligible physicians that improves license portability across states. There are currently 18 states that participate, and the number continues to increase.

For credentialing, most hospitals require initial credentialing and full recredentialing every 2 years. Maintaining credentials at several sites can be extremely time consuming. To ease this burden, some hospitals with telehealth programs have adopted “credentialing by proxy,” which means that one hospital will accept the credentialing process of another facility.

What next?

In summary, there has been and will likely continue to be explosive growth of telehospitalist programs and providers for all the reasons outlined above. Although some barriers to efficient and effective practice do exist, many of those barriers are being overcome quite rapidly. I expect this growth to continue for the betterment of hospitalists, our patients, and the systems in which we work. For a more in-depth look into telemedicine in hospital medicine, view a report created by a work group of SHM's Practice Management Committee.

Dr. Scheurer is a hospitalist and chief quality officer at the Medical University of South Carolina in Charleston. She is physician editor of The Hospitalist. Email her at [email protected].

References

1.Cisco. (2013 March 4). Cisco Study Reveals 74 Percent of Consumers Open to Virtual Doctor Visit. Cisco: The Network. Retrieved from https://newsroom.cisco.com/press-release-content?type=webcontent&articleId=1148539.

2. Interstate Medical Licensure Compact Commission. (2017). Interstate Medical Licensure Compact. Retrieved from http://www.licenseportability.org/index.html.

Within hospital medicine, there has been a recent increase in programs that provide virtual or telehealth hospitalists, primarily to hospitals that are small, remote, and/or understaffed. According to a 2013 Cisco health care customer experience report, the number of telehealth consumers will likely markedly increase to at least 7 million by 2018.1

Since telehospitalist programs are still relatively new, there are many questions about why and how they exist and how they are (and can be) funded. Questions also remain about some limitations of telehospitalist programs for both the “givers” and the “receivers” of the services. I tackle some of these questions in this article.

What is a telehospitalist?

What are the drivers of telehospitalist programs?

One primary driver of telehealth (and specifically telehospitalist) programs is an ongoing shortage of hospitalists, especially in remote areas and critical access hospitals where coverage issues are especially prominent at night and/or on weekends. In many hospitals, there is also a growing unwillingness on the part of physicians to be routinely on call at night. Although working on call used to be on par with being a physician, many younger-generation physicians are less willing to blur “work and life.” This increases the need for dedicated night coverage in many hospitals.

Another driver for some programs (especially at tertiary care medical centers) is a desire to more thoroughly assess patients prior to transfer to their respective centers (the alternative being a phone conversation with the transferring center about the patient’s status). There is also a growing desire to keep patients local if possible, which is usually better for the patient and the family and can decrease the total cost of their care.

Another catalyst to telehospitalist program growth is the growing cultural comfort level with two-way video interactions, such as Skype and FaceTime. Since videoconferencing has permeated most of our professional and personal lives, telehealth seems familiar and comfortable for both providers and patients. In a recent consumer survey, three out of every four consumers responded that they are very comfortable communicating with providers via technology, as opposed to seeing them in person.1

Another driver for some programs is financial. Depending on the way the program is structured, it can be not only financially feasible but financially beneficial, especially if the program can consolidate coverage across multiple sites (more on this later).

One other driver for some health care systems is the need to cover areas with on-site nurse practitioners and physician assistants. Using a telehospitalist makes it easier to get appropriate and required oversight for this coverage model across time and space.

What are the advantages of being a telehospitalist?

Some of the career advantages of being a telehospitalist include the shift flexibility and convenience. This work allows a hospitalist to serve a shift from anywhere in the world and from the convenience of their home. Some telehospitalists can easily work local night shifts when they live many time zones away (and therefore, don’t actually have to work a night shift). Many programs are designed to have a single hospitalist cover many hospitals over a wide geography, which would be logistically impossible to do in person. This is especially appealing for multihospital systems that cannot afford to have a hospitalist on site at each location.

The earning potential can also be appealing, depending on the number of shifts a hospitalist is willing to work.

What are the limitations of being a telehospitalist?

There are limits to what a telehospitalist can perform, many of which depend on the manner in which the program and the technology are arranged. Telehealth can vary from a cart-based videoconferencing system that is transported into a patient’s room to an independent robot that travels throughout sites. The primary limitation is the need to rely on someone in the patient’s room to act as virtual hands. This usually falls to the bedside nurse and requires a good working relationship and patience on their part. The bedside nurses have to “buy into” the program in advance and may need to have scripting for how to explain the process to the patients.

Another major challenge is interacting with different electronic health record systems. Becoming agile with a single EHR is challenging enough, but maneuvering several of them in a single shift can be extremely trying. Telehospitalists can also be challenged by technology glitches or failures that need troubleshooting both on their end and on-site. Although these problems are rare, there will always be a concern that the patient will not get his or her needs met if the technology fails.

How does the financing work?

Although this is a rapidly changing landscape, telehospitalists are not currently able to generate much revenue from professional billing. Unlike in-person visits, Medicare will not reimburse professional fees for telehospitalist visits. Although each payer is unique, most other (nonMedicare) payers are also not willing to reimburse for televisits. This may change in the future, however, as Medicare does pay for virtual specialty services such as telestroke. In addition, many states have enacted telemedicine parity laws, which require private payers to pay for all health care services equally, regardless of modality (audio, video, or in person).

For now, the financial case for employing telehospitalists for most programs has to be made using benfits other than the generation of professional fees. For telehospitalist programs that can cover several sites, the cost is substantially less than employing individual on-site hospitalists to do low-volume work. Telehospitalist programs are also, likely, less costly than is locum tenens staffing. For programs that evaluate the need for transfers, a case can be made that keeping a patient in a smaller, low-cost venue, rather than transferring them to a larger, higher-cost venue, can also reduce overall cost for a health care system.

What about licensing and credentialing?

Telehospitalists can be hindered by the need to have a license in several states and to be credentialed in several systems. This can be cumbersome, time-consuming, and expensive. To ease the multistate licensing burden, the Interstate Medical Licensure Compact has been established.2 This is an accelerated licensure process for eligible physicians that improves license portability across states. There are currently 18 states that participate, and the number continues to increase.

For credentialing, most hospitals require initial credentialing and full recredentialing every 2 years. Maintaining credentials at several sites can be extremely time consuming. To ease this burden, some hospitals with telehealth programs have adopted “credentialing by proxy,” which means that one hospital will accept the credentialing process of another facility.

What next?

In summary, there has been and will likely continue to be explosive growth of telehospitalist programs and providers for all the reasons outlined above. Although some barriers to efficient and effective practice do exist, many of those barriers are being overcome quite rapidly. I expect this growth to continue for the betterment of hospitalists, our patients, and the systems in which we work. For a more in-depth look into telemedicine in hospital medicine, view a report created by a work group of SHM's Practice Management Committee.

Dr. Scheurer is a hospitalist and chief quality officer at the Medical University of South Carolina in Charleston. She is physician editor of The Hospitalist. Email her at [email protected].

References

1.Cisco. (2013 March 4). Cisco Study Reveals 74 Percent of Consumers Open to Virtual Doctor Visit. Cisco: The Network. Retrieved from https://newsroom.cisco.com/press-release-content?type=webcontent&articleId=1148539.

2. Interstate Medical Licensure Compact Commission. (2017). Interstate Medical Licensure Compact. Retrieved from http://www.licenseportability.org/index.html.

End-of-rotation resident transition in care and mortality among hospitalized patients

CLINICAL QUESTION: Are hospitalized patients experiencing an increased mortality risk at the end-rotation resident transition in care and is this association related to the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) 2011 duty-hour regulations?

BACKGROUND: Prior studies of physicians’ transitions in care were associated with potential adverse patient events and outcomes. A higher mortality risk was suggested among patients with a complex hospital course or prolonged length of stay in association to house-staff transitions of care.

SETTING: 10 University-affiliated U.S. Veterans Health Administration hospitals.

SYNOPSIS: 230,701 patient discharges (mean age, 65.6 years; 95.8% male sex; median length of stay, 3 days) were included. The transition group included patients admitted at any time prior to an end-of-rotation who were either discharged or deceased within 7 days of transition. All other discharges were considered controls.

The primary outcome was in-hospital mortality rate; secondary outcomes included 30-day and 90-day mortality and readmission rates. An absolute increase of 1.5% to 1.9% in a unadjusted in-hospitality risk was found. The 30-day and 90-day mortality odds ratios were 1.10 and 1.21, respectively. A possible stronger association was found among interns’ transitions in care and the in-hospital and after-discharge mortality post-ACGME 2011 duty hour regulations. The latter raises questions about the interns’ inexperience and their amount of shift-to-shift handoffs. An adjusted analysis of the readmission rates at 30-day and 90-day was not significantly different between transition vs. control patients.

BOTTOM LINE: Elevated in-hospital mortality was seen among patients admitted to the inpatient medicine service at the end-of-rotation resident transitions in care. The association was stronger after the duty-hour ACGME (2011) regulations.

CITATIONS: Denson JL, Jensen A, Saag HS, et al. Association between end-of-rotation resident transition in care and mortality among hospitalized patients. JAMA. 2016 Dec 6;316(21):2204-13.

Dr. Orjuela is assistant professor of neurology at the University of Colorado School of Medicine, Aurora

CLINICAL QUESTION: Are hospitalized patients experiencing an increased mortality risk at the end-rotation resident transition in care and is this association related to the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) 2011 duty-hour regulations?

BACKGROUND: Prior studies of physicians’ transitions in care were associated with potential adverse patient events and outcomes. A higher mortality risk was suggested among patients with a complex hospital course or prolonged length of stay in association to house-staff transitions of care.

SETTING: 10 University-affiliated U.S. Veterans Health Administration hospitals.

SYNOPSIS: 230,701 patient discharges (mean age, 65.6 years; 95.8% male sex; median length of stay, 3 days) were included. The transition group included patients admitted at any time prior to an end-of-rotation who were either discharged or deceased within 7 days of transition. All other discharges were considered controls.

The primary outcome was in-hospital mortality rate; secondary outcomes included 30-day and 90-day mortality and readmission rates. An absolute increase of 1.5% to 1.9% in a unadjusted in-hospitality risk was found. The 30-day and 90-day mortality odds ratios were 1.10 and 1.21, respectively. A possible stronger association was found among interns’ transitions in care and the in-hospital and after-discharge mortality post-ACGME 2011 duty hour regulations. The latter raises questions about the interns’ inexperience and their amount of shift-to-shift handoffs. An adjusted analysis of the readmission rates at 30-day and 90-day was not significantly different between transition vs. control patients.

BOTTOM LINE: Elevated in-hospital mortality was seen among patients admitted to the inpatient medicine service at the end-of-rotation resident transitions in care. The association was stronger after the duty-hour ACGME (2011) regulations.

CITATIONS: Denson JL, Jensen A, Saag HS, et al. Association between end-of-rotation resident transition in care and mortality among hospitalized patients. JAMA. 2016 Dec 6;316(21):2204-13.

Dr. Orjuela is assistant professor of neurology at the University of Colorado School of Medicine, Aurora

CLINICAL QUESTION: Are hospitalized patients experiencing an increased mortality risk at the end-rotation resident transition in care and is this association related to the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) 2011 duty-hour regulations?

BACKGROUND: Prior studies of physicians’ transitions in care were associated with potential adverse patient events and outcomes. A higher mortality risk was suggested among patients with a complex hospital course or prolonged length of stay in association to house-staff transitions of care.

SETTING: 10 University-affiliated U.S. Veterans Health Administration hospitals.

SYNOPSIS: 230,701 patient discharges (mean age, 65.6 years; 95.8% male sex; median length of stay, 3 days) were included. The transition group included patients admitted at any time prior to an end-of-rotation who were either discharged or deceased within 7 days of transition. All other discharges were considered controls.

The primary outcome was in-hospital mortality rate; secondary outcomes included 30-day and 90-day mortality and readmission rates. An absolute increase of 1.5% to 1.9% in a unadjusted in-hospitality risk was found. The 30-day and 90-day mortality odds ratios were 1.10 and 1.21, respectively. A possible stronger association was found among interns’ transitions in care and the in-hospital and after-discharge mortality post-ACGME 2011 duty hour regulations. The latter raises questions about the interns’ inexperience and their amount of shift-to-shift handoffs. An adjusted analysis of the readmission rates at 30-day and 90-day was not significantly different between transition vs. control patients.

BOTTOM LINE: Elevated in-hospital mortality was seen among patients admitted to the inpatient medicine service at the end-of-rotation resident transitions in care. The association was stronger after the duty-hour ACGME (2011) regulations.

CITATIONS: Denson JL, Jensen A, Saag HS, et al. Association between end-of-rotation resident transition in care and mortality among hospitalized patients. JAMA. 2016 Dec 6;316(21):2204-13.

Dr. Orjuela is assistant professor of neurology at the University of Colorado School of Medicine, Aurora

Systems engineering in the hospital

Systems-engineering expert James Benneyan, PhD, doesn’t want hospitalists to look at poorly working processes in their institutions and think, “I should try to tweak this process to improve it.”

Instead, he wants them to walk out of his HM17 session at 8 a.m. Thursday – appropriately titled, “Systems Engineering in the Hospital: What Is in Your Toolkit?” – thinking like engineers, which means designing a solution, analyzing how well that process works, and then optimizing it for improvements. If that means not just tweaking a process, but redesigning it from scratch, so be it.

“Systems engineering studies the performance and how to improve the performance of complex systems, particularly sociotechnical systems,” said Dr. Benneyan, who runs the Healthcare Systems Engineering Institute at Northeastern University in Boston, which encompasses four research centers. “Health care is a perfect example … systems engineering can really help to understand and improve complex processes, whether it’s patient flow, safety, on-time discharge [or] better discharge.”

Dr. Benneyan says that systems engineering is, first and foremost, a mindset. It’s an approach to problem solving that’s different, if related, to quality improvement. Both have tremendous value, but they are based on different philosophies, tools, and work styles.

For example, many hospital operating rooms measure how many days the first procedure of the day begins on time. But instead of using that as a yardstick for quality, Dr. Benneyan said a better approach would be designing a system that can adapt to situations when the first case starts late. He compared the process to a delayed flight at an airport. An airline doesn’t back up every plane’s departure when one plane is running behind. Instead, it has systems that adapt to circumstances.

“There are methods and then there are philosophies,” Dr. Benneyan said. “I don’t think people in health care realize what my field did in the airline industry. We didn’t design things that worked and clicked properly. We designed things that … react to daily events and [everything] going on and perform pretty well.”

Dr. Benneyan says that, while health care is an incredibly complex system, other fields with similar levels of technical expertise have used systems engineering much more effectively. Manufacturing, logistics, and global distribution networks are all precise industries requiring hundreds of individual processes to ensure success.

“These are really complicated processes,” he said. “The real barrier is a cultural barrier. Health care is not the most challenging environment to work in. … I think something that people in health care have to have an appreciation for is that the process of doing this work is different from doing their other work. Systems engineering is not the same as quality improvement and can achieve fundamental breakthroughs in cases where QI has not – but also tends to take more work.”

Still, Dr. Benneyan believes his field has lessons that complement quality initiatives. To wit, health care advocates – including the Institute of Medicine, the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, the National Institutes of Health, and the National Science Foundation – have all pushed for greater application of systems engineering in medicine with the goal of improving how well health care does its job.

While he hopes hospitalists and other HM17 attendees at his session walk away with a newfound respect for and understanding of what systems engineering can do, he doesn’t want them to think it’s too easy.

“There’s a lack of appreciation of the process of engineering and how it’s different,” he said. “It’s a big challenge, partnering clinician with engineers. … We think differently even though we’re both scientifically trained.

“I hope hospitalists take away an appreciation for how this toolkit can be useful in their world.”

Systems Engineering in the Hospital: What Is in Your Toolkit?

Thursday, 8:00–9:30 a.m.

Systems-engineering expert James Benneyan, PhD, doesn’t want hospitalists to look at poorly working processes in their institutions and think, “I should try to tweak this process to improve it.”

Instead, he wants them to walk out of his HM17 session at 8 a.m. Thursday – appropriately titled, “Systems Engineering in the Hospital: What Is in Your Toolkit?” – thinking like engineers, which means designing a solution, analyzing how well that process works, and then optimizing it for improvements. If that means not just tweaking a process, but redesigning it from scratch, so be it.

“Systems engineering studies the performance and how to improve the performance of complex systems, particularly sociotechnical systems,” said Dr. Benneyan, who runs the Healthcare Systems Engineering Institute at Northeastern University in Boston, which encompasses four research centers. “Health care is a perfect example … systems engineering can really help to understand and improve complex processes, whether it’s patient flow, safety, on-time discharge [or] better discharge.”

Dr. Benneyan says that systems engineering is, first and foremost, a mindset. It’s an approach to problem solving that’s different, if related, to quality improvement. Both have tremendous value, but they are based on different philosophies, tools, and work styles.

For example, many hospital operating rooms measure how many days the first procedure of the day begins on time. But instead of using that as a yardstick for quality, Dr. Benneyan said a better approach would be designing a system that can adapt to situations when the first case starts late. He compared the process to a delayed flight at an airport. An airline doesn’t back up every plane’s departure when one plane is running behind. Instead, it has systems that adapt to circumstances.

“There are methods and then there are philosophies,” Dr. Benneyan said. “I don’t think people in health care realize what my field did in the airline industry. We didn’t design things that worked and clicked properly. We designed things that … react to daily events and [everything] going on and perform pretty well.”

Dr. Benneyan says that, while health care is an incredibly complex system, other fields with similar levels of technical expertise have used systems engineering much more effectively. Manufacturing, logistics, and global distribution networks are all precise industries requiring hundreds of individual processes to ensure success.

“These are really complicated processes,” he said. “The real barrier is a cultural barrier. Health care is not the most challenging environment to work in. … I think something that people in health care have to have an appreciation for is that the process of doing this work is different from doing their other work. Systems engineering is not the same as quality improvement and can achieve fundamental breakthroughs in cases where QI has not – but also tends to take more work.”

Still, Dr. Benneyan believes his field has lessons that complement quality initiatives. To wit, health care advocates – including the Institute of Medicine, the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, the National Institutes of Health, and the National Science Foundation – have all pushed for greater application of systems engineering in medicine with the goal of improving how well health care does its job.

While he hopes hospitalists and other HM17 attendees at his session walk away with a newfound respect for and understanding of what systems engineering can do, he doesn’t want them to think it’s too easy.

“There’s a lack of appreciation of the process of engineering and how it’s different,” he said. “It’s a big challenge, partnering clinician with engineers. … We think differently even though we’re both scientifically trained.

“I hope hospitalists take away an appreciation for how this toolkit can be useful in their world.”

Systems Engineering in the Hospital: What Is in Your Toolkit?

Thursday, 8:00–9:30 a.m.

Systems-engineering expert James Benneyan, PhD, doesn’t want hospitalists to look at poorly working processes in their institutions and think, “I should try to tweak this process to improve it.”

Instead, he wants them to walk out of his HM17 session at 8 a.m. Thursday – appropriately titled, “Systems Engineering in the Hospital: What Is in Your Toolkit?” – thinking like engineers, which means designing a solution, analyzing how well that process works, and then optimizing it for improvements. If that means not just tweaking a process, but redesigning it from scratch, so be it.

“Systems engineering studies the performance and how to improve the performance of complex systems, particularly sociotechnical systems,” said Dr. Benneyan, who runs the Healthcare Systems Engineering Institute at Northeastern University in Boston, which encompasses four research centers. “Health care is a perfect example … systems engineering can really help to understand and improve complex processes, whether it’s patient flow, safety, on-time discharge [or] better discharge.”

Dr. Benneyan says that systems engineering is, first and foremost, a mindset. It’s an approach to problem solving that’s different, if related, to quality improvement. Both have tremendous value, but they are based on different philosophies, tools, and work styles.

For example, many hospital operating rooms measure how many days the first procedure of the day begins on time. But instead of using that as a yardstick for quality, Dr. Benneyan said a better approach would be designing a system that can adapt to situations when the first case starts late. He compared the process to a delayed flight at an airport. An airline doesn’t back up every plane’s departure when one plane is running behind. Instead, it has systems that adapt to circumstances.

“There are methods and then there are philosophies,” Dr. Benneyan said. “I don’t think people in health care realize what my field did in the airline industry. We didn’t design things that worked and clicked properly. We designed things that … react to daily events and [everything] going on and perform pretty well.”

Dr. Benneyan says that, while health care is an incredibly complex system, other fields with similar levels of technical expertise have used systems engineering much more effectively. Manufacturing, logistics, and global distribution networks are all precise industries requiring hundreds of individual processes to ensure success.

“These are really complicated processes,” he said. “The real barrier is a cultural barrier. Health care is not the most challenging environment to work in. … I think something that people in health care have to have an appreciation for is that the process of doing this work is different from doing their other work. Systems engineering is not the same as quality improvement and can achieve fundamental breakthroughs in cases where QI has not – but also tends to take more work.”

Still, Dr. Benneyan believes his field has lessons that complement quality initiatives. To wit, health care advocates – including the Institute of Medicine, the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, the National Institutes of Health, and the National Science Foundation – have all pushed for greater application of systems engineering in medicine with the goal of improving how well health care does its job.

While he hopes hospitalists and other HM17 attendees at his session walk away with a newfound respect for and understanding of what systems engineering can do, he doesn’t want them to think it’s too easy.

“There’s a lack of appreciation of the process of engineering and how it’s different,” he said. “It’s a big challenge, partnering clinician with engineers. … We think differently even though we’re both scientifically trained.

“I hope hospitalists take away an appreciation for how this toolkit can be useful in their world.”

Systems Engineering in the Hospital: What Is in Your Toolkit?

Thursday, 8:00–9:30 a.m.

SHM receives Eisenberg Award as part of I-PASS Study Group

The Society of Hospital Medicine is part of a patient safety research group that received the prestigious 2016 John M. Eisenberg Award for Innovation in Patient Safety and Quality presented annually by The Joint Commission and the National Quality Forum, two leading organizations that set standards in patient care as part of the I-PASS Study Group.

I-PASS comprises a suite of educational materials and interventions dedicated to improving patient safety by reducing miscommunication during patient handoffs that can lead to harmful medical errors. The team in SHM’s Center for Quality Improvement has been instrumental in supporting the I-PASS Study Group, which represents more than 50 hospitals from across North America.

“The Eisenberg Award for Innovation represents the highest patient safety and quality award in the country, and we are honored to be recognized for our role in this important program,” said Jenna Goldstein, director of SHM’s Center for Quality Improvement. “Our team’s participation in developing and sustaining the SHM I-PASS mentored implementation demonstrates our commitment to ensure safe and high-quality care for hospitalized patients.”

SHM previously won the 2011 Eisenberg Award at the national level for its mentored implementation program model. Through its mentored implementation framework and project management, SHM has supported the I-PASS program across the country at 32 hospitals of varying types, including pediatric and adult hospitals, academic medical centers, and community-based hospitals. SHM has offered both an I-PASS mentored implementation program, in which a physician mentor coaches hospital team members on evidence-based best practices in process improvement and culture change for safe patient handoffs, and an implementation guide, which contains strategies and tools needed to lead the quality improvement effort in the hospital.

In a large multicenter study published in the New England Journal of Medicine, implementation of I-PASS was associated with a 30% reduction in medical errors that harm patients. An estimated 80% of the most serious medical errors can be linked to communication failures, particularly during patient handoffs.

In addition to its work with I-PASS, SHM’s Center for Quality Improvement plays a prominent role in developing tools that empower clinicians to lead quality improvement efforts in their institutions.

Brett Radler is SHM’s communications specialist.

The Society of Hospital Medicine is part of a patient safety research group that received the prestigious 2016 John M. Eisenberg Award for Innovation in Patient Safety and Quality presented annually by The Joint Commission and the National Quality Forum, two leading organizations that set standards in patient care as part of the I-PASS Study Group.

I-PASS comprises a suite of educational materials and interventions dedicated to improving patient safety by reducing miscommunication during patient handoffs that can lead to harmful medical errors. The team in SHM’s Center for Quality Improvement has been instrumental in supporting the I-PASS Study Group, which represents more than 50 hospitals from across North America.

“The Eisenberg Award for Innovation represents the highest patient safety and quality award in the country, and we are honored to be recognized for our role in this important program,” said Jenna Goldstein, director of SHM’s Center for Quality Improvement. “Our team’s participation in developing and sustaining the SHM I-PASS mentored implementation demonstrates our commitment to ensure safe and high-quality care for hospitalized patients.”

SHM previously won the 2011 Eisenberg Award at the national level for its mentored implementation program model. Through its mentored implementation framework and project management, SHM has supported the I-PASS program across the country at 32 hospitals of varying types, including pediatric and adult hospitals, academic medical centers, and community-based hospitals. SHM has offered both an I-PASS mentored implementation program, in which a physician mentor coaches hospital team members on evidence-based best practices in process improvement and culture change for safe patient handoffs, and an implementation guide, which contains strategies and tools needed to lead the quality improvement effort in the hospital.

In a large multicenter study published in the New England Journal of Medicine, implementation of I-PASS was associated with a 30% reduction in medical errors that harm patients. An estimated 80% of the most serious medical errors can be linked to communication failures, particularly during patient handoffs.

In addition to its work with I-PASS, SHM’s Center for Quality Improvement plays a prominent role in developing tools that empower clinicians to lead quality improvement efforts in their institutions.

Brett Radler is SHM’s communications specialist.

The Society of Hospital Medicine is part of a patient safety research group that received the prestigious 2016 John M. Eisenberg Award for Innovation in Patient Safety and Quality presented annually by The Joint Commission and the National Quality Forum, two leading organizations that set standards in patient care as part of the I-PASS Study Group.

I-PASS comprises a suite of educational materials and interventions dedicated to improving patient safety by reducing miscommunication during patient handoffs that can lead to harmful medical errors. The team in SHM’s Center for Quality Improvement has been instrumental in supporting the I-PASS Study Group, which represents more than 50 hospitals from across North America.

“The Eisenberg Award for Innovation represents the highest patient safety and quality award in the country, and we are honored to be recognized for our role in this important program,” said Jenna Goldstein, director of SHM’s Center for Quality Improvement. “Our team’s participation in developing and sustaining the SHM I-PASS mentored implementation demonstrates our commitment to ensure safe and high-quality care for hospitalized patients.”

SHM previously won the 2011 Eisenberg Award at the national level for its mentored implementation program model. Through its mentored implementation framework and project management, SHM has supported the I-PASS program across the country at 32 hospitals of varying types, including pediatric and adult hospitals, academic medical centers, and community-based hospitals. SHM has offered both an I-PASS mentored implementation program, in which a physician mentor coaches hospital team members on evidence-based best practices in process improvement and culture change for safe patient handoffs, and an implementation guide, which contains strategies and tools needed to lead the quality improvement effort in the hospital.

In a large multicenter study published in the New England Journal of Medicine, implementation of I-PASS was associated with a 30% reduction in medical errors that harm patients. An estimated 80% of the most serious medical errors can be linked to communication failures, particularly during patient handoffs.

In addition to its work with I-PASS, SHM’s Center for Quality Improvement plays a prominent role in developing tools that empower clinicians to lead quality improvement efforts in their institutions.

Brett Radler is SHM’s communications specialist.

How’s your postacute network doing?

By now, nearly all hospitals are developing networks of postacute facilities for some or all of their patients, such as those in ACOs, bundled payments, or other value-based programs. Commonly referred to as preferred providers, performance networks, narrow networks, or similar, these networks of skilled nursing facilities (SNFs) and other entities that provide postacute care (like home health agencies) are usually chosen because they have demonstrated that they provide high quality, cost-effective care for patients after they leave the hospital.

While case managers are often the ones who counsel patients and caregivers on the details of the network, hospitalists should have at least a high-level grasp of which facilities are on the list and what the network selection criteria are. I would argue that hospitalists should lead the discussion with patients on postacute facility selection as it relates to which facilities are in the network and why going to a network facility is advantageous. Why? Because as hospitalist practices begin to share clinical and financial risk for patients, or at least become eligible to share in savings as MACRA encourages, they will have a vested interest in network facilities’ performance.

Postacute care network selection criteria

There is a range of criteria – usually incorporating measures of quality and efficiency – for including providers like SNFs in networks. In terms of quality, criteria can include physician/provider availability, star ratings on Nursing Home Compare, care transitions measures, Department of Public Health inspection survey scores, Joint Commission accreditation, etc.

A few caveats regarding specific selection criteria:

Star ratings on Nursing Home Compare

These are derived from nursing staffing ratios, health inspections, and 16 quality measures. More than half of the quality measures pertain to long-stay residents who typically are not in the ACO or bundled payment program for which the network was created (these are usually short-stay patients).

SNF length of stay

High readmission rates from a SNF can actually lower its length of stay, so including “balancing” measures such as readmissions should be considered.

What about patient choice?

Narrow postacute networks are not only becoming the norm, but there is also broad recognition from CMS, MedPAC, and industry leaders that value-based payment programs require such networks to succeed. That said, case managers and other discharge planners may still resist networks on the grounds that they might be perceived as restricting patient choice. One approach to balancing differing views on patient choice is to give patients the traditional longer list of available postacute providers, and also furnish the shorter network list accompanied by an explanation of why certain SNFs are in the network. Thankfully, as ACOs and bundles become widespread, resistance to narrow networks is dying down.

What role should hospitalists play in network referrals?

High functioning hospitalist practices should lead the discussion with patients and the health care team on referrals to network SNFs. Why? Patients are looking for their doctors to guide them on such decisions. Only if the physician opts not to have the discussion will patients look to the case manager for direction on which postacute facility to choose. A better option still would be for the hospitalists to partner with case managers to have the conversation with patients. In such a scenario, the hospitalist can begin the discussion and cover the major points, and the case manager can follow with more detailed information. For less mature hospitalist practices, the case manager can play a larger role in the discussion. In any case, as value-based models become ubiquitous, and shared savings become a driver of hospitalist revenue, hospitalists’ knowledge of and active participation in conversations around narrow networks and referrals will be necessary.

Dr. Whitcomb is chief medical officer at Remedy Partners in Darien, Conn. He is a cofounder and past president of SHM.

By now, nearly all hospitals are developing networks of postacute facilities for some or all of their patients, such as those in ACOs, bundled payments, or other value-based programs. Commonly referred to as preferred providers, performance networks, narrow networks, or similar, these networks of skilled nursing facilities (SNFs) and other entities that provide postacute care (like home health agencies) are usually chosen because they have demonstrated that they provide high quality, cost-effective care for patients after they leave the hospital.

While case managers are often the ones who counsel patients and caregivers on the details of the network, hospitalists should have at least a high-level grasp of which facilities are on the list and what the network selection criteria are. I would argue that hospitalists should lead the discussion with patients on postacute facility selection as it relates to which facilities are in the network and why going to a network facility is advantageous. Why? Because as hospitalist practices begin to share clinical and financial risk for patients, or at least become eligible to share in savings as MACRA encourages, they will have a vested interest in network facilities’ performance.

Postacute care network selection criteria

There is a range of criteria – usually incorporating measures of quality and efficiency – for including providers like SNFs in networks. In terms of quality, criteria can include physician/provider availability, star ratings on Nursing Home Compare, care transitions measures, Department of Public Health inspection survey scores, Joint Commission accreditation, etc.

A few caveats regarding specific selection criteria:

Star ratings on Nursing Home Compare

These are derived from nursing staffing ratios, health inspections, and 16 quality measures. More than half of the quality measures pertain to long-stay residents who typically are not in the ACO or bundled payment program for which the network was created (these are usually short-stay patients).

SNF length of stay

High readmission rates from a SNF can actually lower its length of stay, so including “balancing” measures such as readmissions should be considered.

What about patient choice?

Narrow postacute networks are not only becoming the norm, but there is also broad recognition from CMS, MedPAC, and industry leaders that value-based payment programs require such networks to succeed. That said, case managers and other discharge planners may still resist networks on the grounds that they might be perceived as restricting patient choice. One approach to balancing differing views on patient choice is to give patients the traditional longer list of available postacute providers, and also furnish the shorter network list accompanied by an explanation of why certain SNFs are in the network. Thankfully, as ACOs and bundles become widespread, resistance to narrow networks is dying down.

What role should hospitalists play in network referrals?

High functioning hospitalist practices should lead the discussion with patients and the health care team on referrals to network SNFs. Why? Patients are looking for their doctors to guide them on such decisions. Only if the physician opts not to have the discussion will patients look to the case manager for direction on which postacute facility to choose. A better option still would be for the hospitalists to partner with case managers to have the conversation with patients. In such a scenario, the hospitalist can begin the discussion and cover the major points, and the case manager can follow with more detailed information. For less mature hospitalist practices, the case manager can play a larger role in the discussion. In any case, as value-based models become ubiquitous, and shared savings become a driver of hospitalist revenue, hospitalists’ knowledge of and active participation in conversations around narrow networks and referrals will be necessary.

Dr. Whitcomb is chief medical officer at Remedy Partners in Darien, Conn. He is a cofounder and past president of SHM.

By now, nearly all hospitals are developing networks of postacute facilities for some or all of their patients, such as those in ACOs, bundled payments, or other value-based programs. Commonly referred to as preferred providers, performance networks, narrow networks, or similar, these networks of skilled nursing facilities (SNFs) and other entities that provide postacute care (like home health agencies) are usually chosen because they have demonstrated that they provide high quality, cost-effective care for patients after they leave the hospital.

While case managers are often the ones who counsel patients and caregivers on the details of the network, hospitalists should have at least a high-level grasp of which facilities are on the list and what the network selection criteria are. I would argue that hospitalists should lead the discussion with patients on postacute facility selection as it relates to which facilities are in the network and why going to a network facility is advantageous. Why? Because as hospitalist practices begin to share clinical and financial risk for patients, or at least become eligible to share in savings as MACRA encourages, they will have a vested interest in network facilities’ performance.

Postacute care network selection criteria

There is a range of criteria – usually incorporating measures of quality and efficiency – for including providers like SNFs in networks. In terms of quality, criteria can include physician/provider availability, star ratings on Nursing Home Compare, care transitions measures, Department of Public Health inspection survey scores, Joint Commission accreditation, etc.

A few caveats regarding specific selection criteria:

Star ratings on Nursing Home Compare

These are derived from nursing staffing ratios, health inspections, and 16 quality measures. More than half of the quality measures pertain to long-stay residents who typically are not in the ACO or bundled payment program for which the network was created (these are usually short-stay patients).

SNF length of stay

High readmission rates from a SNF can actually lower its length of stay, so including “balancing” measures such as readmissions should be considered.

What about patient choice?

Narrow postacute networks are not only becoming the norm, but there is also broad recognition from CMS, MedPAC, and industry leaders that value-based payment programs require such networks to succeed. That said, case managers and other discharge planners may still resist networks on the grounds that they might be perceived as restricting patient choice. One approach to balancing differing views on patient choice is to give patients the traditional longer list of available postacute providers, and also furnish the shorter network list accompanied by an explanation of why certain SNFs are in the network. Thankfully, as ACOs and bundles become widespread, resistance to narrow networks is dying down.

What role should hospitalists play in network referrals?

High functioning hospitalist practices should lead the discussion with patients and the health care team on referrals to network SNFs. Why? Patients are looking for their doctors to guide them on such decisions. Only if the physician opts not to have the discussion will patients look to the case manager for direction on which postacute facility to choose. A better option still would be for the hospitalists to partner with case managers to have the conversation with patients. In such a scenario, the hospitalist can begin the discussion and cover the major points, and the case manager can follow with more detailed information. For less mature hospitalist practices, the case manager can play a larger role in the discussion. In any case, as value-based models become ubiquitous, and shared savings become a driver of hospitalist revenue, hospitalists’ knowledge of and active participation in conversations around narrow networks and referrals will be necessary.

Dr. Whitcomb is chief medical officer at Remedy Partners in Darien, Conn. He is a cofounder and past president of SHM.

Sneak Peak: The Hospital Leader Blog

FEATURED POST: “A Renewed Call to Overhaul Hospital Observation Care”

In response to concerns about Medicare beneficiary out-of-pocket financial risk, Congress unanimously passed the NOTICE Act, which President Obama signed into law August 5, 2015. This law states that all Medicare beneficiaries hospitalized for 24 hours or more as outpatients under observation must to be notified in writing that they are outpatients “not later than 36 hours after the time such individual begins receiving such services” as well as the associated “implications for cost-sharing.” Last month, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) released the final Medicare Outpatient Observation Notice (MOON) that hospitals will start delivering to patients no later than March 8, 2017 to comply with the law. Patients or their representatives must sign the form to acknowledge receipt.

First, Medicare beneficiaries are notified after they have been hospitalized, certainly after they could make an informed decision about accepting observation care. Second, patients or their representative must sign the form, yet it is unclear if this signature holds the patient financially liable, particularly if signed by a representative with no legal authority over the patient’s financial affairs. Third, the form does nothing for a patient’s right to appeal their status. And because observation is a billing distinction, the field at the top of the form requiring hospitals to specify why the patient is not an inpatient is circular reasoning, as patients are outpatients only when they fail to meet Medicare inpatient billing criteria.

Perhaps most importantly, the primary purpose of the NOTICE Act – to inform beneficiaries of the “implications for cost-sharing” when hospitalized under observation – cannot truly be accomplished.

On December 19, 2016, the Department of Health and Human Services Office of Inspector General (OIG) issued the best cost-sharing data available to date describing observation hospital care under the 2-midnight rule. In their report, the OIG used FY 2014 data to compare cost of short outpatient and inpatient stays with similar diagnoses. But because hospitalized outpatients under observation pay a copayment for each individual hospital service, financial risk is not directly correlated with a diagnosis but instead the result of the number, cost, and complexity of services rendered in the hospital, with no limit on the additive amount of per-service deductibles. In contrast, the inpatient deductible is finite per benefit period.

As the OIG report does not provide an accounting of services rendered nor comparison based on equivalent services, it isn’t clear how these cost estimates will help inform discussions when my observation patients receive their MOON.

Dr. Sheehy is a physician and associate professor at the University of Wisconsin School of Medicine and Public Health.

Read the full text of this blog post at http://blogs.hospitalmedicine.org/Blog/a-renewed-call-to-overhaul-hospital-observation-care/

Also on The Hospital Leader…

• New ABIM MOC Two-Year Plan for Internal Medicine Threatens the Focused Practice in Hospital Medicine By Burke Kealey, MD, SFHM

• The Nursing Home Get Out of Jail Card (“We Don’t Want Our Patient Back”). It’s Now Adios. By Brad Flansbaum, DO, MPH, MHM

• The Inmates Are Running the Asylum By Tracy Cardin, ACNP-BC, SFHM

• Do Clinicians Understand Quality Metric Data? By Danielle Scheurer, MD, MSCR, SFHM

• Fake News! Get Your Fake News Here! By Jordan Messler, MD, SFHM

FEATURED POST: “A Renewed Call to Overhaul Hospital Observation Care”

In response to concerns about Medicare beneficiary out-of-pocket financial risk, Congress unanimously passed the NOTICE Act, which President Obama signed into law August 5, 2015. This law states that all Medicare beneficiaries hospitalized for 24 hours or more as outpatients under observation must to be notified in writing that they are outpatients “not later than 36 hours after the time such individual begins receiving such services” as well as the associated “implications for cost-sharing.” Last month, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) released the final Medicare Outpatient Observation Notice (MOON) that hospitals will start delivering to patients no later than March 8, 2017 to comply with the law. Patients or their representatives must sign the form to acknowledge receipt.

First, Medicare beneficiaries are notified after they have been hospitalized, certainly after they could make an informed decision about accepting observation care. Second, patients or their representative must sign the form, yet it is unclear if this signature holds the patient financially liable, particularly if signed by a representative with no legal authority over the patient’s financial affairs. Third, the form does nothing for a patient’s right to appeal their status. And because observation is a billing distinction, the field at the top of the form requiring hospitals to specify why the patient is not an inpatient is circular reasoning, as patients are outpatients only when they fail to meet Medicare inpatient billing criteria.

Perhaps most importantly, the primary purpose of the NOTICE Act – to inform beneficiaries of the “implications for cost-sharing” when hospitalized under observation – cannot truly be accomplished.

On December 19, 2016, the Department of Health and Human Services Office of Inspector General (OIG) issued the best cost-sharing data available to date describing observation hospital care under the 2-midnight rule. In their report, the OIG used FY 2014 data to compare cost of short outpatient and inpatient stays with similar diagnoses. But because hospitalized outpatients under observation pay a copayment for each individual hospital service, financial risk is not directly correlated with a diagnosis but instead the result of the number, cost, and complexity of services rendered in the hospital, with no limit on the additive amount of per-service deductibles. In contrast, the inpatient deductible is finite per benefit period.

As the OIG report does not provide an accounting of services rendered nor comparison based on equivalent services, it isn’t clear how these cost estimates will help inform discussions when my observation patients receive their MOON.

Dr. Sheehy is a physician and associate professor at the University of Wisconsin School of Medicine and Public Health.

Read the full text of this blog post at http://blogs.hospitalmedicine.org/Blog/a-renewed-call-to-overhaul-hospital-observation-care/

Also on The Hospital Leader…

• New ABIM MOC Two-Year Plan for Internal Medicine Threatens the Focused Practice in Hospital Medicine By Burke Kealey, MD, SFHM

• The Nursing Home Get Out of Jail Card (“We Don’t Want Our Patient Back”). It’s Now Adios. By Brad Flansbaum, DO, MPH, MHM

• The Inmates Are Running the Asylum By Tracy Cardin, ACNP-BC, SFHM

• Do Clinicians Understand Quality Metric Data? By Danielle Scheurer, MD, MSCR, SFHM

• Fake News! Get Your Fake News Here! By Jordan Messler, MD, SFHM

FEATURED POST: “A Renewed Call to Overhaul Hospital Observation Care”

In response to concerns about Medicare beneficiary out-of-pocket financial risk, Congress unanimously passed the NOTICE Act, which President Obama signed into law August 5, 2015. This law states that all Medicare beneficiaries hospitalized for 24 hours or more as outpatients under observation must to be notified in writing that they are outpatients “not later than 36 hours after the time such individual begins receiving such services” as well as the associated “implications for cost-sharing.” Last month, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) released the final Medicare Outpatient Observation Notice (MOON) that hospitals will start delivering to patients no later than March 8, 2017 to comply with the law. Patients or their representatives must sign the form to acknowledge receipt.

First, Medicare beneficiaries are notified after they have been hospitalized, certainly after they could make an informed decision about accepting observation care. Second, patients or their representative must sign the form, yet it is unclear if this signature holds the patient financially liable, particularly if signed by a representative with no legal authority over the patient’s financial affairs. Third, the form does nothing for a patient’s right to appeal their status. And because observation is a billing distinction, the field at the top of the form requiring hospitals to specify why the patient is not an inpatient is circular reasoning, as patients are outpatients only when they fail to meet Medicare inpatient billing criteria.

Perhaps most importantly, the primary purpose of the NOTICE Act – to inform beneficiaries of the “implications for cost-sharing” when hospitalized under observation – cannot truly be accomplished.

On December 19, 2016, the Department of Health and Human Services Office of Inspector General (OIG) issued the best cost-sharing data available to date describing observation hospital care under the 2-midnight rule. In their report, the OIG used FY 2014 data to compare cost of short outpatient and inpatient stays with similar diagnoses. But because hospitalized outpatients under observation pay a copayment for each individual hospital service, financial risk is not directly correlated with a diagnosis but instead the result of the number, cost, and complexity of services rendered in the hospital, with no limit on the additive amount of per-service deductibles. In contrast, the inpatient deductible is finite per benefit period.

As the OIG report does not provide an accounting of services rendered nor comparison based on equivalent services, it isn’t clear how these cost estimates will help inform discussions when my observation patients receive their MOON.

Dr. Sheehy is a physician and associate professor at the University of Wisconsin School of Medicine and Public Health.

Read the full text of this blog post at http://blogs.hospitalmedicine.org/Blog/a-renewed-call-to-overhaul-hospital-observation-care/

Also on The Hospital Leader…

• New ABIM MOC Two-Year Plan for Internal Medicine Threatens the Focused Practice in Hospital Medicine By Burke Kealey, MD, SFHM

• The Nursing Home Get Out of Jail Card (“We Don’t Want Our Patient Back”). It’s Now Adios. By Brad Flansbaum, DO, MPH, MHM

• The Inmates Are Running the Asylum By Tracy Cardin, ACNP-BC, SFHM

• Do Clinicians Understand Quality Metric Data? By Danielle Scheurer, MD, MSCR, SFHM

• Fake News! Get Your Fake News Here! By Jordan Messler, MD, SFHM

Everything We Say and Do: Discussing advance care planning

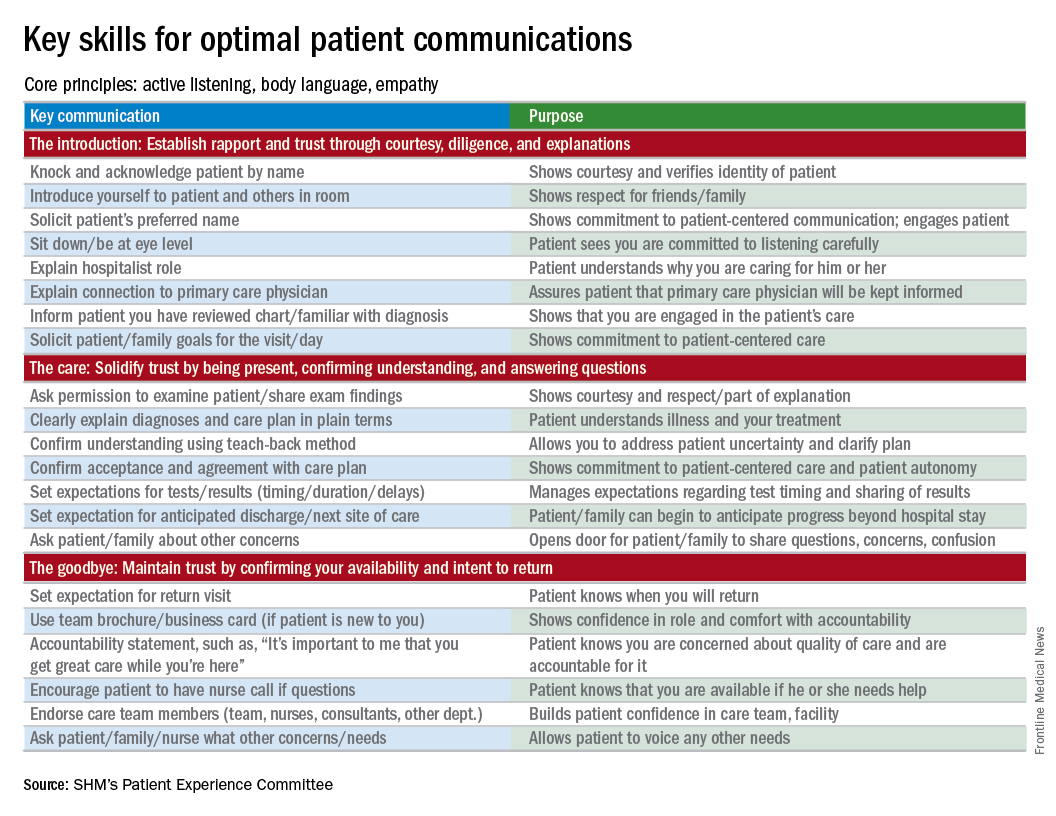

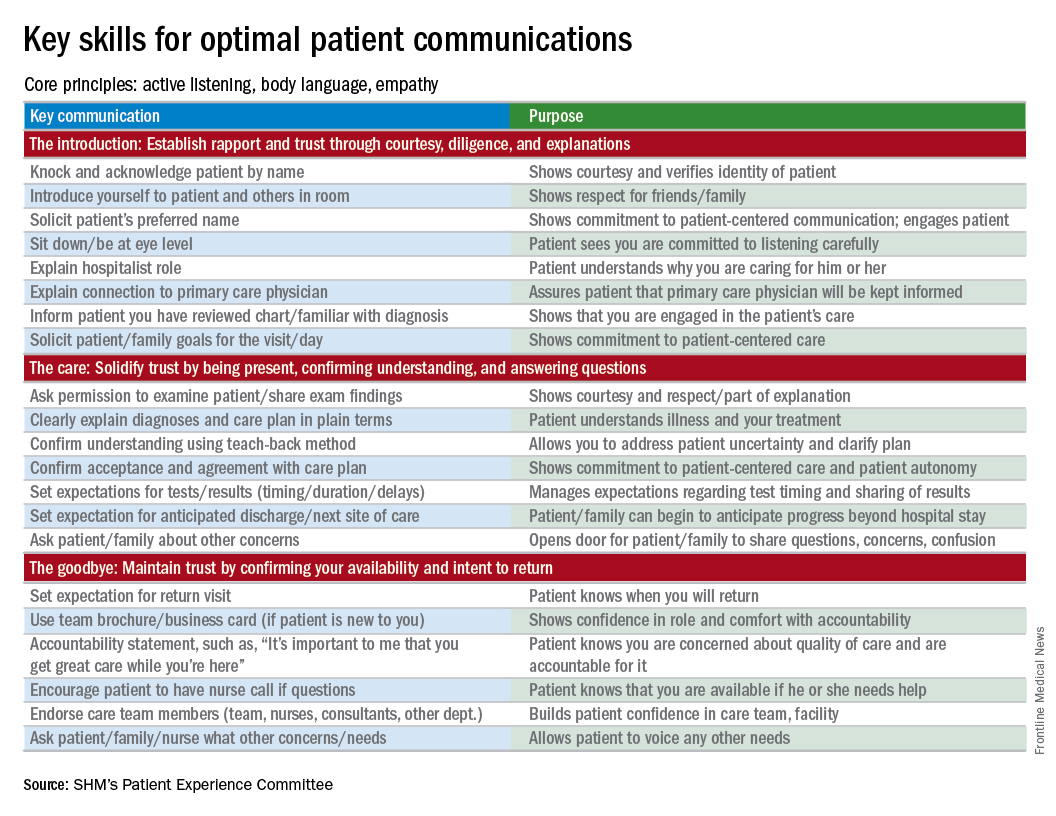

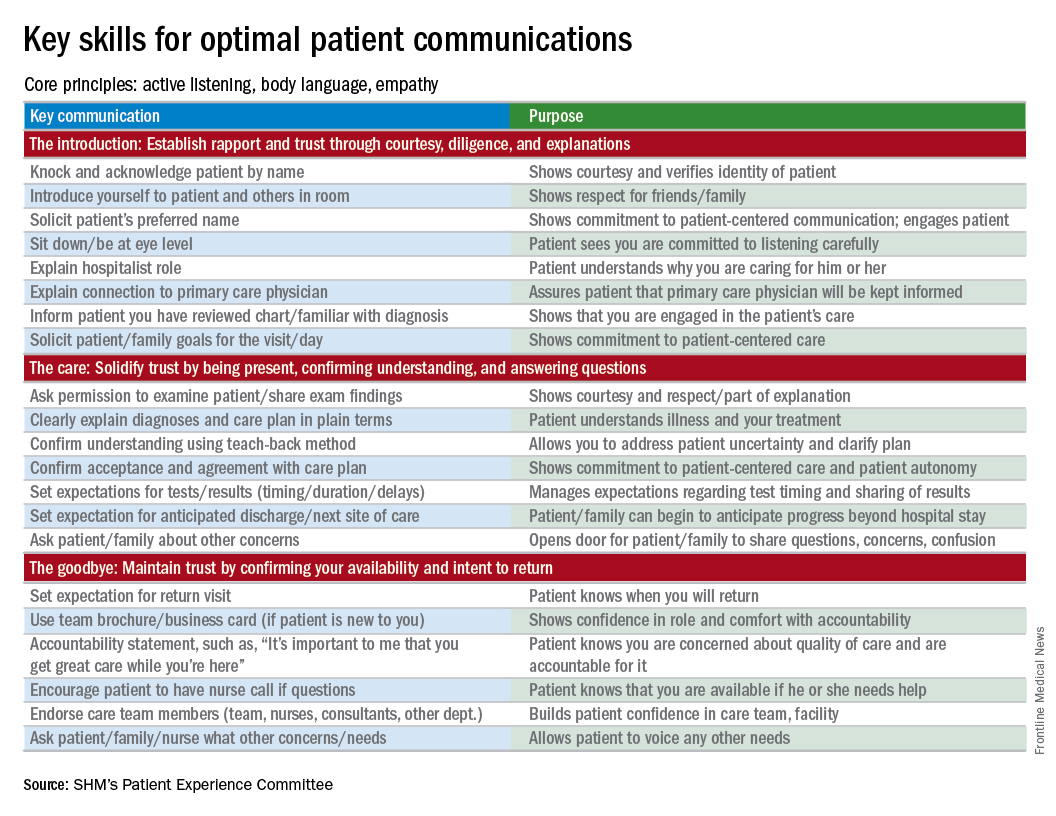

Editor’s note: “Everything We Say and Do” is an informational series developed by the Society of Hospital Medicine’s Patient Experience Committee to provide readers with thoughtful and actionable communication tactics that have great potential to positively impact patients’ experiences of care. Each article will focus on how the contributor applies one or more of the “key communication” tactics in practice to maintain provider accountability for “everything we say and do that affects our patients’ thoughts, feelings, and well-being.”

What I say and do

I empower all of my patients by giving them the opportunity to consider advance care planning.

Why I do it

Everyone deserves advance care planning, and every health care encounter, including a hospitalization, is an opportunity to better identify and document patients’ wishes for care should they become unable to express them. If we wait for patients to develop serious advanced illness before having advance care planning conversations, we risk depriving them of the care they would want in these situations. Additionally, we place a huge burden on family members who may struggle with excruciatingly difficult decisions in the absence of guidance about their loved one’s wishes.

How I do it

I start by identifying which components of advance care planning each patient needs, using a simple algorithm (see figure). All of my patients are queried about code status, and I give them the opportunity to better understand the value of having a healthcare proxy and advance directives, if they are not already in place.

For the remainder of this column, I’m going to focus on patients who have an acute and/or chronic treatable illness – those who require simpler advance-care-planning conversations.

To comfortably initiate the conversation about advance care planning, I always start by asking permission. I commonly say, “There are a couple of important items I discuss with all of my patients to make sure they get the care they want. Would it be okay for us to talk about those now?” This respectfully puts the patient in control. I then initiate a discussion of code status by saying, “It’s important that all of us on your care team know what you would like us to do if you got so sick that we couldn’t communicate with you. I’m not expecting this to happen, but I ask all my patients this question so that we have your instructions.” From there, the conversation evolves depending on whether the patient has any familiarity with this question and its implications.

To introduce the concept of a health care proxy and advance directives, I ask, “Have you ever thought about who you might choose to make medical decisions on your behalf if you became too sick to make those decisions yourself?” Then, finally, I share the following information, usually referring to the blank advance directives document they received in their admission packet: “There is a valuable way to put your wishes about specific care options in writing so others will know your wishes if you’re unable to communicate with them. Would you like to talk about that right now?” Again, this gives the patient control of the situation and an opportunity to decline the conversation if they are not interested or comfortable at that time.

It’s important to document the nature and outcome of these conversations. Keep in mind, advance care planning discussions need not occur at the time of admission. In fact, admission may be the worst time for some patients, further underscoring the importance of documentation so that subsequent providers can see whether advance care planning has been addressed during the hospital stay.

Note: For useful educational resources that address goals-of-care conversations in patients toward the end of life, the Center to Advance Palliative Care (www.capc.org) has a number of educational courses that address these important communication skills.

Dr. Rudolph is vice president of physician development and patient experience for Sound Physicians, Tacoma, Wash. and chair of the SHM Patient Experience Committee .

Reference

1. Moss, A.H., Ganjoo, J, Sharma S, et al. Utility of the “Surprise” Question to Identify Dialysis Patients with High Mortality. Clinical Journal of the American Society of Nephrology: CJASN. 2008;3(5):1379-84. doi:10.2215/CJN.00940208.

Editor’s note: “Everything We Say and Do” is an informational series developed by the Society of Hospital Medicine’s Patient Experience Committee to provide readers with thoughtful and actionable communication tactics that have great potential to positively impact patients’ experiences of care. Each article will focus on how the contributor applies one or more of the “key communication” tactics in practice to maintain provider accountability for “everything we say and do that affects our patients’ thoughts, feelings, and well-being.”