User login

Thoracic Oncology & Chest Imaging Network

Ultrasound & Chest Imaging Section

VExUS scan: The missing piece of hemodynamic puzzle?

Volume status and tailoring the correct level of fluid resuscitation is challenging for the intensivist. Determining “fluid overload,” especially in the setting of acute kidney injury, can be difficult. While a Swan-Ganz catheter, central venous pressure, or inferior vena cava (IVC) ultrasound measurement can suggest elevated right atrial pressure, the effect on organ level hemodynamics is unknown.

Abdominal venous Doppler is a method to view the effects of venous pressure on abdominal organ venous flow. An application of this is the Venous Excess Ultrasound Score (VExUS) (Rola, et al. Ultrasound J. 2021;13[1]:32). VExUS uses IVC diameter and pulse wave doppler waveforms from the hepatic, portal, and renal veins to grade venous congestion from none to severe. Studies demonstrate an association between venous congestion and renal dysfunction in cardiac surgery (Beaubien-Souligny, et al. Ultrasound J. 2020;12[1]:16) and general ICU patients (Spiegel, et al. Crit Care. 2020;24[1]:615).

This practice of identifying venous congestion and avoiding over-resuscitation could improve patient care. However, acquiring quality images and waveforms may prove to be difficult, and interpretation may be confounded by other disease states such as cirrhosis. Though it is postulated that removing fluid could be beneficial to patients with high VExUS scores, this has yet to be proven and may be difficult to prove. While the score estimates volume status well, the source of venous congestion is not identified such that it should be used as a clinical supplement to other data.

VExUS has a strong physiologic basis, and early clinical experience indicates a strong role in improving assessment of venous congestion, an important aspect of volume status. This is an area of ongoing research to ensure appropriate and effective use.

Kyle Swartz, DO

Steven Fox, MD

John Levasseur, DO

Ultrasound & Chest Imaging Section

VExUS scan: The missing piece of hemodynamic puzzle?

Volume status and tailoring the correct level of fluid resuscitation is challenging for the intensivist. Determining “fluid overload,” especially in the setting of acute kidney injury, can be difficult. While a Swan-Ganz catheter, central venous pressure, or inferior vena cava (IVC) ultrasound measurement can suggest elevated right atrial pressure, the effect on organ level hemodynamics is unknown.

Abdominal venous Doppler is a method to view the effects of venous pressure on abdominal organ venous flow. An application of this is the Venous Excess Ultrasound Score (VExUS) (Rola, et al. Ultrasound J. 2021;13[1]:32). VExUS uses IVC diameter and pulse wave doppler waveforms from the hepatic, portal, and renal veins to grade venous congestion from none to severe. Studies demonstrate an association between venous congestion and renal dysfunction in cardiac surgery (Beaubien-Souligny, et al. Ultrasound J. 2020;12[1]:16) and general ICU patients (Spiegel, et al. Crit Care. 2020;24[1]:615).

This practice of identifying venous congestion and avoiding over-resuscitation could improve patient care. However, acquiring quality images and waveforms may prove to be difficult, and interpretation may be confounded by other disease states such as cirrhosis. Though it is postulated that removing fluid could be beneficial to patients with high VExUS scores, this has yet to be proven and may be difficult to prove. While the score estimates volume status well, the source of venous congestion is not identified such that it should be used as a clinical supplement to other data.

VExUS has a strong physiologic basis, and early clinical experience indicates a strong role in improving assessment of venous congestion, an important aspect of volume status. This is an area of ongoing research to ensure appropriate and effective use.

Kyle Swartz, DO

Steven Fox, MD

John Levasseur, DO

Ultrasound & Chest Imaging Section

VExUS scan: The missing piece of hemodynamic puzzle?

Volume status and tailoring the correct level of fluid resuscitation is challenging for the intensivist. Determining “fluid overload,” especially in the setting of acute kidney injury, can be difficult. While a Swan-Ganz catheter, central venous pressure, or inferior vena cava (IVC) ultrasound measurement can suggest elevated right atrial pressure, the effect on organ level hemodynamics is unknown.

Abdominal venous Doppler is a method to view the effects of venous pressure on abdominal organ venous flow. An application of this is the Venous Excess Ultrasound Score (VExUS) (Rola, et al. Ultrasound J. 2021;13[1]:32). VExUS uses IVC diameter and pulse wave doppler waveforms from the hepatic, portal, and renal veins to grade venous congestion from none to severe. Studies demonstrate an association between venous congestion and renal dysfunction in cardiac surgery (Beaubien-Souligny, et al. Ultrasound J. 2020;12[1]:16) and general ICU patients (Spiegel, et al. Crit Care. 2020;24[1]:615).

This practice of identifying venous congestion and avoiding over-resuscitation could improve patient care. However, acquiring quality images and waveforms may prove to be difficult, and interpretation may be confounded by other disease states such as cirrhosis. Though it is postulated that removing fluid could be beneficial to patients with high VExUS scores, this has yet to be proven and may be difficult to prove. While the score estimates volume status well, the source of venous congestion is not identified such that it should be used as a clinical supplement to other data.

VExUS has a strong physiologic basis, and early clinical experience indicates a strong role in improving assessment of venous congestion, an important aspect of volume status. This is an area of ongoing research to ensure appropriate and effective use.

Kyle Swartz, DO

Steven Fox, MD

John Levasseur, DO

Critical Care Network

Sepsis/Shock Section

Fluid Resuscitation – Back to BaSICS

The age-old debate regarding the appropriate timing, volume, and type of fluid resuscitation for patients in septic shock rages on – or does it? In October 2021, the Surviving Sepsis Campaign published updated guidelines for the management of sepsis. One of the biggest changes from prior versions was downgrading the recommendation for an initial 30mL/kg bolus of IV crystalloid for the initial resuscitation of a patient in septic shock to a suggestion, based on dynamic measures to assess individual patients’ fluid balance (Evans, et al. Crit Care Med. 2021;49[11]:e1063-e1143).

Traditionally, 0.9% saline had been the resuscitative fluid of choice in sepsis. But it has a propensity to cause physiologic derangements such as hyperchloremic metabolic acidosis, renal afferent vasoconstriction, and reduced glomerular filtration rate – not to mention, can be a signal for possibly increased mortality, as seen in the SMART trial (Semler, et al. N Engl J Med. 2018;378[9]:829-839). Normal saline had subsequently fallen from grace in favor of balanced crystalloids such as Lactated Ringer’s and Plasma-Lyte. However, the recent PLUS and BaSICS trials showed no significant difference in 90-day mortality or secondary outcomes of acute kidney injury, need for renal replacement therapy, or ICU mortality (Finfer, et al. N Engl J Med. 2022;386[9]:815-826; Zampieri, et al. JAMA. 2021;326[9]:818-829). While these are large randomized controlled trials, a major weakness is the administration of uncontrolled resuscitative fluids prior to randomization and even postenrollment, which may have biased results.

Ultimately, does the choice between salt water or balanced crystalloids matter? Despite the limitations in the newest trials, probably less than the timely administration of antibiotics and pressors, unless your patient also has a traumatic TBI – then go with the saline. But, in the everlasting quest for medical excellence, choosing the balanced fluid that causes the least physiologic derangement seems to make the most sense.

LCDR Meredith Olsen, MD, USN

Ankita Agarwal, MD

The views expressed are those of the authors and do not reflect the official policy or position of the U.S. Navy, Department of Defense, or the U.S. Government.

Sepsis/Shock Section

Fluid Resuscitation – Back to BaSICS

The age-old debate regarding the appropriate timing, volume, and type of fluid resuscitation for patients in septic shock rages on – or does it? In October 2021, the Surviving Sepsis Campaign published updated guidelines for the management of sepsis. One of the biggest changes from prior versions was downgrading the recommendation for an initial 30mL/kg bolus of IV crystalloid for the initial resuscitation of a patient in septic shock to a suggestion, based on dynamic measures to assess individual patients’ fluid balance (Evans, et al. Crit Care Med. 2021;49[11]:e1063-e1143).

Traditionally, 0.9% saline had been the resuscitative fluid of choice in sepsis. But it has a propensity to cause physiologic derangements such as hyperchloremic metabolic acidosis, renal afferent vasoconstriction, and reduced glomerular filtration rate – not to mention, can be a signal for possibly increased mortality, as seen in the SMART trial (Semler, et al. N Engl J Med. 2018;378[9]:829-839). Normal saline had subsequently fallen from grace in favor of balanced crystalloids such as Lactated Ringer’s and Plasma-Lyte. However, the recent PLUS and BaSICS trials showed no significant difference in 90-day mortality or secondary outcomes of acute kidney injury, need for renal replacement therapy, or ICU mortality (Finfer, et al. N Engl J Med. 2022;386[9]:815-826; Zampieri, et al. JAMA. 2021;326[9]:818-829). While these are large randomized controlled trials, a major weakness is the administration of uncontrolled resuscitative fluids prior to randomization and even postenrollment, which may have biased results.

Ultimately, does the choice between salt water or balanced crystalloids matter? Despite the limitations in the newest trials, probably less than the timely administration of antibiotics and pressors, unless your patient also has a traumatic TBI – then go with the saline. But, in the everlasting quest for medical excellence, choosing the balanced fluid that causes the least physiologic derangement seems to make the most sense.

LCDR Meredith Olsen, MD, USN

Ankita Agarwal, MD

The views expressed are those of the authors and do not reflect the official policy or position of the U.S. Navy, Department of Defense, or the U.S. Government.

Sepsis/Shock Section

Fluid Resuscitation – Back to BaSICS

The age-old debate regarding the appropriate timing, volume, and type of fluid resuscitation for patients in septic shock rages on – or does it? In October 2021, the Surviving Sepsis Campaign published updated guidelines for the management of sepsis. One of the biggest changes from prior versions was downgrading the recommendation for an initial 30mL/kg bolus of IV crystalloid for the initial resuscitation of a patient in septic shock to a suggestion, based on dynamic measures to assess individual patients’ fluid balance (Evans, et al. Crit Care Med. 2021;49[11]:e1063-e1143).

Traditionally, 0.9% saline had been the resuscitative fluid of choice in sepsis. But it has a propensity to cause physiologic derangements such as hyperchloremic metabolic acidosis, renal afferent vasoconstriction, and reduced glomerular filtration rate – not to mention, can be a signal for possibly increased mortality, as seen in the SMART trial (Semler, et al. N Engl J Med. 2018;378[9]:829-839). Normal saline had subsequently fallen from grace in favor of balanced crystalloids such as Lactated Ringer’s and Plasma-Lyte. However, the recent PLUS and BaSICS trials showed no significant difference in 90-day mortality or secondary outcomes of acute kidney injury, need for renal replacement therapy, or ICU mortality (Finfer, et al. N Engl J Med. 2022;386[9]:815-826; Zampieri, et al. JAMA. 2021;326[9]:818-829). While these are large randomized controlled trials, a major weakness is the administration of uncontrolled resuscitative fluids prior to randomization and even postenrollment, which may have biased results.

Ultimately, does the choice between salt water or balanced crystalloids matter? Despite the limitations in the newest trials, probably less than the timely administration of antibiotics and pressors, unless your patient also has a traumatic TBI – then go with the saline. But, in the everlasting quest for medical excellence, choosing the balanced fluid that causes the least physiologic derangement seems to make the most sense.

LCDR Meredith Olsen, MD, USN

Ankita Agarwal, MD

The views expressed are those of the authors and do not reflect the official policy or position of the U.S. Navy, Department of Defense, or the U.S. Government.

Pulmonary Vascular & Cardiovascular Network

Pulmonary Vascular Disease Section

Key messages from the 2022 ESC/ERS Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Pulmonary Hypertension

1. Per coverage by the American College of Cardiology, “Pulmonary hypertension (PH) is now defined by a mean pulmonary arterial pressure >20 mm Hg at rest. The definition of pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH) also implies a pulmonary vascular resistance (PVR) >2 Wood units and pulmonary arterial wedge pressure ≤15 mm Hg.”1 These cut-off values do not translate into new therapeutic recommendations.

2. , involving first suspicion by first-line physicians, then detection by echocardiography, and confirmation with right heart catheterization, preferably in a PH center.

3. Pulmonary vasoreactivity testing is only recommended in patients with idiopathic PAH, heritable PAH, or drug/toxin associated PAH to identify potential candidates for calcium channel blocker therapy. Inhaled nitric oxide or inhaled iloprost are the recommended agents.

4. The role of cardiac MRI in prognostication of patients with PAH has been confirmed such that measures of right ventricular volume, right ventricular ejection fraction, and stroke volume are included as risk assessment variables.

5. The primary limitation of the 2015 ESC/ERS three-strata risk-assessment tool is that 60% to 70% of the patients are classified as intermediate risk (IR). A four-strata risk stratification, dividing the IR group into IR “low” and IR “high” risk, is proposed at follow up.

6. No general recommendation is made for or against the use of anticoagulation in PAH given the absence of robust data and increased risk of bleeding.

7. In patients with PH-ILD, inhaled treprostinil may be considered based on findings from the INCREASE trial, but further long-term outcome data are needed.

8. Improved recognition of the signs of chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension (CTEPH) on CT and echocardiographic imagery at the time of an acute pulmonary embolism (PE) event, along with systematic follow-up of patients with acute PE, is recommended to help mitigate the underdiagnosis of CTEPH.

9. The treatment algorithm for PAH has been simplified, and now includes a focus on cardiopulmonary comorbidities, risk assessment, and treatment goals. Current standards include initial combination therapy and treatment escalation at follow-up, when appropriate.

10. Per coverage by the American College of Cardiology, “The recommendations on sex-related issues in patients with PAH, including pregnancy, have been updated, with information and shared decision making as key points.” Calcium channel blockers, inhaled/IV/subcutaneous prostacyclin analogues, and phosphodiesterase 5 inhibitors all and are considered safe during pregnancy, despite limited data on this use.

11. Per the guideline, “Patients with PAH should be treated with the best standard of pharmacological treatment and be in stable clinical condition before embarking on a supervised rehabilitation program.”2 Additional studies have shown that exercise training has a beneficial impact on 6-minute walk distance, quality of life, World Health Organization function classification, and peak VO2.

12. Immunization of PAH patients against SARS-CoV-2, influenza, and Streptococcus pneumoniae is recommended.

This edition of clinical practice guidelines focuses on early diagnosis of PAH and optimal treatments.

*Mary Jo S. Farmer, MD, PhD

Member-at-Large

Vijay Balasubramanian, MD, MRCP (UK)

Chair

* The authors for this article were listed in the incorrect order in the print edition of CHEST Physician. The order has been corrected here.

References

1. Mukherjee, D. 2022 ESC/ERS guidelines for pulmonary hypertension: key points. American College of Cardiology. August 30, 2022.

2. Humbert M, Kovacs G, Hoeper MM, et al. 2022 ESC/ERS guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of pulmonary hypertension. Eur Heart J. 2022;43(38):3618-3731.

Pulmonary Vascular Disease Section

Key messages from the 2022 ESC/ERS Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Pulmonary Hypertension

1. Per coverage by the American College of Cardiology, “Pulmonary hypertension (PH) is now defined by a mean pulmonary arterial pressure >20 mm Hg at rest. The definition of pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH) also implies a pulmonary vascular resistance (PVR) >2 Wood units and pulmonary arterial wedge pressure ≤15 mm Hg.”1 These cut-off values do not translate into new therapeutic recommendations.

2. , involving first suspicion by first-line physicians, then detection by echocardiography, and confirmation with right heart catheterization, preferably in a PH center.

3. Pulmonary vasoreactivity testing is only recommended in patients with idiopathic PAH, heritable PAH, or drug/toxin associated PAH to identify potential candidates for calcium channel blocker therapy. Inhaled nitric oxide or inhaled iloprost are the recommended agents.

4. The role of cardiac MRI in prognostication of patients with PAH has been confirmed such that measures of right ventricular volume, right ventricular ejection fraction, and stroke volume are included as risk assessment variables.

5. The primary limitation of the 2015 ESC/ERS three-strata risk-assessment tool is that 60% to 70% of the patients are classified as intermediate risk (IR). A four-strata risk stratification, dividing the IR group into IR “low” and IR “high” risk, is proposed at follow up.

6. No general recommendation is made for or against the use of anticoagulation in PAH given the absence of robust data and increased risk of bleeding.

7. In patients with PH-ILD, inhaled treprostinil may be considered based on findings from the INCREASE trial, but further long-term outcome data are needed.

8. Improved recognition of the signs of chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension (CTEPH) on CT and echocardiographic imagery at the time of an acute pulmonary embolism (PE) event, along with systematic follow-up of patients with acute PE, is recommended to help mitigate the underdiagnosis of CTEPH.

9. The treatment algorithm for PAH has been simplified, and now includes a focus on cardiopulmonary comorbidities, risk assessment, and treatment goals. Current standards include initial combination therapy and treatment escalation at follow-up, when appropriate.

10. Per coverage by the American College of Cardiology, “The recommendations on sex-related issues in patients with PAH, including pregnancy, have been updated, with information and shared decision making as key points.” Calcium channel blockers, inhaled/IV/subcutaneous prostacyclin analogues, and phosphodiesterase 5 inhibitors all and are considered safe during pregnancy, despite limited data on this use.

11. Per the guideline, “Patients with PAH should be treated with the best standard of pharmacological treatment and be in stable clinical condition before embarking on a supervised rehabilitation program.”2 Additional studies have shown that exercise training has a beneficial impact on 6-minute walk distance, quality of life, World Health Organization function classification, and peak VO2.

12. Immunization of PAH patients against SARS-CoV-2, influenza, and Streptococcus pneumoniae is recommended.

This edition of clinical practice guidelines focuses on early diagnosis of PAH and optimal treatments.

*Mary Jo S. Farmer, MD, PhD

Member-at-Large

Vijay Balasubramanian, MD, MRCP (UK)

Chair

* The authors for this article were listed in the incorrect order in the print edition of CHEST Physician. The order has been corrected here.

References

1. Mukherjee, D. 2022 ESC/ERS guidelines for pulmonary hypertension: key points. American College of Cardiology. August 30, 2022.

2. Humbert M, Kovacs G, Hoeper MM, et al. 2022 ESC/ERS guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of pulmonary hypertension. Eur Heart J. 2022;43(38):3618-3731.

Pulmonary Vascular Disease Section

Key messages from the 2022 ESC/ERS Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Pulmonary Hypertension

1. Per coverage by the American College of Cardiology, “Pulmonary hypertension (PH) is now defined by a mean pulmonary arterial pressure >20 mm Hg at rest. The definition of pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH) also implies a pulmonary vascular resistance (PVR) >2 Wood units and pulmonary arterial wedge pressure ≤15 mm Hg.”1 These cut-off values do not translate into new therapeutic recommendations.

2. , involving first suspicion by first-line physicians, then detection by echocardiography, and confirmation with right heart catheterization, preferably in a PH center.

3. Pulmonary vasoreactivity testing is only recommended in patients with idiopathic PAH, heritable PAH, or drug/toxin associated PAH to identify potential candidates for calcium channel blocker therapy. Inhaled nitric oxide or inhaled iloprost are the recommended agents.

4. The role of cardiac MRI in prognostication of patients with PAH has been confirmed such that measures of right ventricular volume, right ventricular ejection fraction, and stroke volume are included as risk assessment variables.

5. The primary limitation of the 2015 ESC/ERS three-strata risk-assessment tool is that 60% to 70% of the patients are classified as intermediate risk (IR). A four-strata risk stratification, dividing the IR group into IR “low” and IR “high” risk, is proposed at follow up.

6. No general recommendation is made for or against the use of anticoagulation in PAH given the absence of robust data and increased risk of bleeding.

7. In patients with PH-ILD, inhaled treprostinil may be considered based on findings from the INCREASE trial, but further long-term outcome data are needed.

8. Improved recognition of the signs of chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension (CTEPH) on CT and echocardiographic imagery at the time of an acute pulmonary embolism (PE) event, along with systematic follow-up of patients with acute PE, is recommended to help mitigate the underdiagnosis of CTEPH.

9. The treatment algorithm for PAH has been simplified, and now includes a focus on cardiopulmonary comorbidities, risk assessment, and treatment goals. Current standards include initial combination therapy and treatment escalation at follow-up, when appropriate.

10. Per coverage by the American College of Cardiology, “The recommendations on sex-related issues in patients with PAH, including pregnancy, have been updated, with information and shared decision making as key points.” Calcium channel blockers, inhaled/IV/subcutaneous prostacyclin analogues, and phosphodiesterase 5 inhibitors all and are considered safe during pregnancy, despite limited data on this use.

11. Per the guideline, “Patients with PAH should be treated with the best standard of pharmacological treatment and be in stable clinical condition before embarking on a supervised rehabilitation program.”2 Additional studies have shown that exercise training has a beneficial impact on 6-minute walk distance, quality of life, World Health Organization function classification, and peak VO2.

12. Immunization of PAH patients against SARS-CoV-2, influenza, and Streptococcus pneumoniae is recommended.

This edition of clinical practice guidelines focuses on early diagnosis of PAH and optimal treatments.

*Mary Jo S. Farmer, MD, PhD

Member-at-Large

Vijay Balasubramanian, MD, MRCP (UK)

Chair

* The authors for this article were listed in the incorrect order in the print edition of CHEST Physician. The order has been corrected here.

References

1. Mukherjee, D. 2022 ESC/ERS guidelines for pulmonary hypertension: key points. American College of Cardiology. August 30, 2022.

2. Humbert M, Kovacs G, Hoeper MM, et al. 2022 ESC/ERS guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of pulmonary hypertension. Eur Heart J. 2022;43(38):3618-3731.

Diffuse Lung Disease & Transplant Network

Pulmonary Physiology & Rehabilitation Section

Exercise tolerance in untreated sleep apnea

Numerous cardiovascular, respiratory, neuromuscular, and perceptual factors determine exercise tolerance. This makes designing a study to isolate the contribution of one factor difficult.

A recently published study (Elbehairy, et al. Chest. 2022; published online September 29, 2022) explores exercise tolerance in patients with untreated OSA compared with age- and weight-matched controls. The authors found that at an equivalent work rate, patients with OSA had greater minute ventilation, principally due to higher breathing frequency. Dead space volume, dead space ventilation, and dead space to tidal volume ratio (VD/VT) were higher in patients with OSA, likely due to a reduction in pulmonary vessel recruitment relative to ventilation. VD/VT decreased more from rest to peak in controls than in patients with OSA, an adaptation that is expected with exercise. Patients with OSA had greater arterial stiffness measured by pulse wave velocity and higher blood pressures, which may have affected cardiac output augmentation. Patients with OSA also had higher resting mean pulmonary artery pressures and exercise dyspnea scores. Regression models predicting peak oxygen uptake and peak work rate were statistically significant, with predictors being age, pulse wave velocity, and resting mean pulmonary artery pressure. The role of diastolic dysfunction remains to be determined.

Prior studies have shown that some effects of OSA on exercise may be reversed with CPAP treatment (Arias, et al. Eur Heart J. 2006;27[9]:1106-1113; Chalegre, et al. Sleep Breath. 2021;25[3]:1195-1202). Understanding the mechanisms of exercise limitation in OSA will help physicians address symptoms, reinforce CPAP adherence, and design tailored pulmonary rehabilitation programs.

Fatima Zeba, MD

Fellow-in-Training

Pulmonary Physiology & Rehabilitation Section

Exercise tolerance in untreated sleep apnea

Numerous cardiovascular, respiratory, neuromuscular, and perceptual factors determine exercise tolerance. This makes designing a study to isolate the contribution of one factor difficult.

A recently published study (Elbehairy, et al. Chest. 2022; published online September 29, 2022) explores exercise tolerance in patients with untreated OSA compared with age- and weight-matched controls. The authors found that at an equivalent work rate, patients with OSA had greater minute ventilation, principally due to higher breathing frequency. Dead space volume, dead space ventilation, and dead space to tidal volume ratio (VD/VT) were higher in patients with OSA, likely due to a reduction in pulmonary vessel recruitment relative to ventilation. VD/VT decreased more from rest to peak in controls than in patients with OSA, an adaptation that is expected with exercise. Patients with OSA had greater arterial stiffness measured by pulse wave velocity and higher blood pressures, which may have affected cardiac output augmentation. Patients with OSA also had higher resting mean pulmonary artery pressures and exercise dyspnea scores. Regression models predicting peak oxygen uptake and peak work rate were statistically significant, with predictors being age, pulse wave velocity, and resting mean pulmonary artery pressure. The role of diastolic dysfunction remains to be determined.

Prior studies have shown that some effects of OSA on exercise may be reversed with CPAP treatment (Arias, et al. Eur Heart J. 2006;27[9]:1106-1113; Chalegre, et al. Sleep Breath. 2021;25[3]:1195-1202). Understanding the mechanisms of exercise limitation in OSA will help physicians address symptoms, reinforce CPAP adherence, and design tailored pulmonary rehabilitation programs.

Fatima Zeba, MD

Fellow-in-Training

Pulmonary Physiology & Rehabilitation Section

Exercise tolerance in untreated sleep apnea

Numerous cardiovascular, respiratory, neuromuscular, and perceptual factors determine exercise tolerance. This makes designing a study to isolate the contribution of one factor difficult.

A recently published study (Elbehairy, et al. Chest. 2022; published online September 29, 2022) explores exercise tolerance in patients with untreated OSA compared with age- and weight-matched controls. The authors found that at an equivalent work rate, patients with OSA had greater minute ventilation, principally due to higher breathing frequency. Dead space volume, dead space ventilation, and dead space to tidal volume ratio (VD/VT) were higher in patients with OSA, likely due to a reduction in pulmonary vessel recruitment relative to ventilation. VD/VT decreased more from rest to peak in controls than in patients with OSA, an adaptation that is expected with exercise. Patients with OSA had greater arterial stiffness measured by pulse wave velocity and higher blood pressures, which may have affected cardiac output augmentation. Patients with OSA also had higher resting mean pulmonary artery pressures and exercise dyspnea scores. Regression models predicting peak oxygen uptake and peak work rate were statistically significant, with predictors being age, pulse wave velocity, and resting mean pulmonary artery pressure. The role of diastolic dysfunction remains to be determined.

Prior studies have shown that some effects of OSA on exercise may be reversed with CPAP treatment (Arias, et al. Eur Heart J. 2006;27[9]:1106-1113; Chalegre, et al. Sleep Breath. 2021;25[3]:1195-1202). Understanding the mechanisms of exercise limitation in OSA will help physicians address symptoms, reinforce CPAP adherence, and design tailored pulmonary rehabilitation programs.

Fatima Zeba, MD

Fellow-in-Training

Airways Disorders Network

Pediatric Chest Medicine Section

CPAP for pediatric OSA: “Off-label” use

Pediatric providers are well aware of the “off-label” uses of medications/devices. While it’s not a stretch to apply “adult” diagnostic and therapeutic criteria to older adolescents, more careful consideration is needed for our younger patients. Typically, adenotonsillectomy is first-line treatment for pediatric OSA, but CPAP can be essential for those for whom surgical intervention is not an option, not an option yet, or has been insufficient (residual OSA). Unfortunately, standard CPAP devices are not approved for use in children, and often have a minimum weight requirement of 30 kg. There are respiratory assist devices and home mechanical ventilators that are approved for use in pediatric patients (minimum weight 13 kg or 5 kg) and designed for more complex ventilatory support, and that also are capable of providing continuous pressure. Alternatively, pediatric providers may proceed with the “off-label” use of simpler CPAP-only medical devices and face obstacles in attaining insurance approval. The recent American Academy of Sleep Medicine position statement (Amos, et al. J Clin Sleep Med. 2022;18[8]:2041-3) acknowledges that CPAP therapy can be safe and effective when management is guided by a pediatric specialist and is typically initiated in a monitored setting (inpatient or polysomnogram). The authors bring up excellent points regarding unique considerations for pediatric CPAP therapy, including the need for desensitization and facial development monitoring, lack of technical/software designed for younger/smaller patients, and limited published data (small and diverse cohorts). Ultimately, evaluation of effectiveness and safety, while distinct, must both be seriously considered in this risk-benefit analysis of care.

Pallavi P. Patwari, MD, FAAP, FAASM

Member-at-Large

Pediatric Chest Medicine Section

CPAP for pediatric OSA: “Off-label” use

Pediatric providers are well aware of the “off-label” uses of medications/devices. While it’s not a stretch to apply “adult” diagnostic and therapeutic criteria to older adolescents, more careful consideration is needed for our younger patients. Typically, adenotonsillectomy is first-line treatment for pediatric OSA, but CPAP can be essential for those for whom surgical intervention is not an option, not an option yet, or has been insufficient (residual OSA). Unfortunately, standard CPAP devices are not approved for use in children, and often have a minimum weight requirement of 30 kg. There are respiratory assist devices and home mechanical ventilators that are approved for use in pediatric patients (minimum weight 13 kg or 5 kg) and designed for more complex ventilatory support, and that also are capable of providing continuous pressure. Alternatively, pediatric providers may proceed with the “off-label” use of simpler CPAP-only medical devices and face obstacles in attaining insurance approval. The recent American Academy of Sleep Medicine position statement (Amos, et al. J Clin Sleep Med. 2022;18[8]:2041-3) acknowledges that CPAP therapy can be safe and effective when management is guided by a pediatric specialist and is typically initiated in a monitored setting (inpatient or polysomnogram). The authors bring up excellent points regarding unique considerations for pediatric CPAP therapy, including the need for desensitization and facial development monitoring, lack of technical/software designed for younger/smaller patients, and limited published data (small and diverse cohorts). Ultimately, evaluation of effectiveness and safety, while distinct, must both be seriously considered in this risk-benefit analysis of care.

Pallavi P. Patwari, MD, FAAP, FAASM

Member-at-Large

Pediatric Chest Medicine Section

CPAP for pediatric OSA: “Off-label” use

Pediatric providers are well aware of the “off-label” uses of medications/devices. While it’s not a stretch to apply “adult” diagnostic and therapeutic criteria to older adolescents, more careful consideration is needed for our younger patients. Typically, adenotonsillectomy is first-line treatment for pediatric OSA, but CPAP can be essential for those for whom surgical intervention is not an option, not an option yet, or has been insufficient (residual OSA). Unfortunately, standard CPAP devices are not approved for use in children, and often have a minimum weight requirement of 30 kg. There are respiratory assist devices and home mechanical ventilators that are approved for use in pediatric patients (minimum weight 13 kg or 5 kg) and designed for more complex ventilatory support, and that also are capable of providing continuous pressure. Alternatively, pediatric providers may proceed with the “off-label” use of simpler CPAP-only medical devices and face obstacles in attaining insurance approval. The recent American Academy of Sleep Medicine position statement (Amos, et al. J Clin Sleep Med. 2022;18[8]:2041-3) acknowledges that CPAP therapy can be safe and effective when management is guided by a pediatric specialist and is typically initiated in a monitored setting (inpatient or polysomnogram). The authors bring up excellent points regarding unique considerations for pediatric CPAP therapy, including the need for desensitization and facial development monitoring, lack of technical/software designed for younger/smaller patients, and limited published data (small and diverse cohorts). Ultimately, evaluation of effectiveness and safety, while distinct, must both be seriously considered in this risk-benefit analysis of care.

Pallavi P. Patwari, MD, FAAP, FAASM

Member-at-Large

End the year on a wine note at the final Viva La Vino event of 2022

Don’t miss your last chance to join the CHEST Foundation for a celebration of excellent initiatives – and equally excellent wines – at the last Viva La Vino event of 2022, happening on December 1 at 7 pm.

This event will focus on white and red varietals from Piedmont, a region of Northwest Italy. The Piedmont area is known for producing more wines classified as Denominazione di Origine Controllata e Garantita, the highest classification of quality for wines in Italy, than any other region.

Join CHEST CEO Bob Musacchio, PhD, as he guides attendees through a virtual and interactive exploration of the history, varietals, and techniques of Piedmont wines. Plus, hear from other CHEST leaders and friends of the Foundation about the important work currently being done and the evolution of the Foundation’s many initiatives since its inception.

With their ticket, attendees will receive one bottle of white wine and two bottles of red wine – including Paitin Starda Langhe Nebbiolo 2019, Michele Chiarlo Le Madri Roero Arneis 2020, and Massolino Barbera d’Alba 2019 – as well as an Italian-themed snack kit featuring cheese, salami, taralli, and other tasty treats, to complement their imbibes.

Funds raised from Viva La Vino benefit the Harold Amos Medical Faculty Development Program (AMFDP) and CHEST initiatives to improve patient care. The AMFDP offers 4-year postdoctoral research awards to physicians, dentists, and nurses from historically marginalized backgrounds. Learn more about the recipient of this year’s grant, George Alba, MD, in the September issue of CHEST Physician.

Don’t miss your last chance to join the CHEST Foundation for a celebration of excellent initiatives – and equally excellent wines – at the last Viva La Vino event of 2022, happening on December 1 at 7 pm.

This event will focus on white and red varietals from Piedmont, a region of Northwest Italy. The Piedmont area is known for producing more wines classified as Denominazione di Origine Controllata e Garantita, the highest classification of quality for wines in Italy, than any other region.

Join CHEST CEO Bob Musacchio, PhD, as he guides attendees through a virtual and interactive exploration of the history, varietals, and techniques of Piedmont wines. Plus, hear from other CHEST leaders and friends of the Foundation about the important work currently being done and the evolution of the Foundation’s many initiatives since its inception.

With their ticket, attendees will receive one bottle of white wine and two bottles of red wine – including Paitin Starda Langhe Nebbiolo 2019, Michele Chiarlo Le Madri Roero Arneis 2020, and Massolino Barbera d’Alba 2019 – as well as an Italian-themed snack kit featuring cheese, salami, taralli, and other tasty treats, to complement their imbibes.

Funds raised from Viva La Vino benefit the Harold Amos Medical Faculty Development Program (AMFDP) and CHEST initiatives to improve patient care. The AMFDP offers 4-year postdoctoral research awards to physicians, dentists, and nurses from historically marginalized backgrounds. Learn more about the recipient of this year’s grant, George Alba, MD, in the September issue of CHEST Physician.

Don’t miss your last chance to join the CHEST Foundation for a celebration of excellent initiatives – and equally excellent wines – at the last Viva La Vino event of 2022, happening on December 1 at 7 pm.

This event will focus on white and red varietals from Piedmont, a region of Northwest Italy. The Piedmont area is known for producing more wines classified as Denominazione di Origine Controllata e Garantita, the highest classification of quality for wines in Italy, than any other region.

Join CHEST CEO Bob Musacchio, PhD, as he guides attendees through a virtual and interactive exploration of the history, varietals, and techniques of Piedmont wines. Plus, hear from other CHEST leaders and friends of the Foundation about the important work currently being done and the evolution of the Foundation’s many initiatives since its inception.

With their ticket, attendees will receive one bottle of white wine and two bottles of red wine – including Paitin Starda Langhe Nebbiolo 2019, Michele Chiarlo Le Madri Roero Arneis 2020, and Massolino Barbera d’Alba 2019 – as well as an Italian-themed snack kit featuring cheese, salami, taralli, and other tasty treats, to complement their imbibes.

Funds raised from Viva La Vino benefit the Harold Amos Medical Faculty Development Program (AMFDP) and CHEST initiatives to improve patient care. The AMFDP offers 4-year postdoctoral research awards to physicians, dentists, and nurses from historically marginalized backgrounds. Learn more about the recipient of this year’s grant, George Alba, MD, in the September issue of CHEST Physician.

Chest Infections & Disaster Response Network

Disaster Response & Global Health Section

Responding to firearm violence in America

We think of disasters as sudden, calamitous events, but it does not take much imagination to recognize the loss of lives in America from firearm violence as a type of disaster. In 2020, 45,222 people died from gun-related injuries, an increase of 5,155 (14%) since 2019 (Kegler, et al. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2022;71[19]:656). This is the highest death rate since 1994, and includes increases in both homicides and suicides. Mass shootings constitute a fraction of this total, but there have already been 530 deaths from mass shooting incidents in 2022.

Opinions about the appropriate degree of firearm regulations remain divided, but the need to improve our response as clinicians is clear. The National Center for Disaster Medicine and Public Health recently published consensus recommendations for healthcare response in mass shootings (Goolsby, et al. J Am Coll Surg. 2022; published online July 18, 2022). These recommendations address readiness training, triage, communications, public education, patient tracking, family reunification, and mental health services.

Stop the Bleed is a program originally based on the military’s Tactical Combat Casualty Care standards. It offers training on hemorrhage control for both the public and clinicians, similar to basic life support programs. It encourages bystanders to become trained and empowered to help in a bleeding emergency before professional help arrives. Opportunities for training are a frequent offering at the CHEST Annual Meeting, and additional information can be found at https://www.stopthebleed.org.

Stella Ogake, MD

Disaster Response & Global Health Section

Responding to firearm violence in America

We think of disasters as sudden, calamitous events, but it does not take much imagination to recognize the loss of lives in America from firearm violence as a type of disaster. In 2020, 45,222 people died from gun-related injuries, an increase of 5,155 (14%) since 2019 (Kegler, et al. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2022;71[19]:656). This is the highest death rate since 1994, and includes increases in both homicides and suicides. Mass shootings constitute a fraction of this total, but there have already been 530 deaths from mass shooting incidents in 2022.

Opinions about the appropriate degree of firearm regulations remain divided, but the need to improve our response as clinicians is clear. The National Center for Disaster Medicine and Public Health recently published consensus recommendations for healthcare response in mass shootings (Goolsby, et al. J Am Coll Surg. 2022; published online July 18, 2022). These recommendations address readiness training, triage, communications, public education, patient tracking, family reunification, and mental health services.

Stop the Bleed is a program originally based on the military’s Tactical Combat Casualty Care standards. It offers training on hemorrhage control for both the public and clinicians, similar to basic life support programs. It encourages bystanders to become trained and empowered to help in a bleeding emergency before professional help arrives. Opportunities for training are a frequent offering at the CHEST Annual Meeting, and additional information can be found at https://www.stopthebleed.org.

Stella Ogake, MD

Disaster Response & Global Health Section

Responding to firearm violence in America

We think of disasters as sudden, calamitous events, but it does not take much imagination to recognize the loss of lives in America from firearm violence as a type of disaster. In 2020, 45,222 people died from gun-related injuries, an increase of 5,155 (14%) since 2019 (Kegler, et al. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2022;71[19]:656). This is the highest death rate since 1994, and includes increases in both homicides and suicides. Mass shootings constitute a fraction of this total, but there have already been 530 deaths from mass shooting incidents in 2022.

Opinions about the appropriate degree of firearm regulations remain divided, but the need to improve our response as clinicians is clear. The National Center for Disaster Medicine and Public Health recently published consensus recommendations for healthcare response in mass shootings (Goolsby, et al. J Am Coll Surg. 2022; published online July 18, 2022). These recommendations address readiness training, triage, communications, public education, patient tracking, family reunification, and mental health services.

Stop the Bleed is a program originally based on the military’s Tactical Combat Casualty Care standards. It offers training on hemorrhage control for both the public and clinicians, similar to basic life support programs. It encourages bystanders to become trained and empowered to help in a bleeding emergency before professional help arrives. Opportunities for training are a frequent offering at the CHEST Annual Meeting, and additional information can be found at https://www.stopthebleed.org.

Stella Ogake, MD

Time travel and thoughts on leadership

This is an odd column for me to write. First, because of the nature of print publication, this writing for the November issue is being crafted just before the annual meeting is to be held in Nashville. Therefore, while I have a pretty good sense of what is in store for CHEST 2022, I have yet to see the final product, or the audience’s reaction to it. However, I will make some bold predictions as to what occurred therein:

- Even in the context of 3 years of separation, thousands CHEST members gathered in droves to rekindle friendships and to experience the best education in pulmonary, critical care, and sleep medicine that the world has to offer, leading to our second-biggest meeting ever.

- Neil Pasricha’s presentation helped attendees rekindle the “Art of Happiness.”

- Hundreds of attendees participated in, and successfully solved, our newest escape room, “Starship Relics.”

- Our valued CHEST members were able to successfully thwart Dr. Didactic and save the future of educational innovation.

- “CHEST After Hours” trended on social media and will become a normal and highly-anticipated part of the CHEST meeting moving forward.

- The most uncomfortable moment of the meeting centered on mayonnaise; for those of you who know what I am referencing, I am a little sorry…but only a little.

- Despite my best efforts, we were not able to recruit Neil Patrick Harris to participate.

Predicting the future of medical meetings is something we’ve spent a lot of time trying to do over the last year as we developed plans for CHEST 2022. But given the talented individuals involved in that planning, foreseeing the meeting’s success did not require any time travel; it was hardly a difficult task at all. Program Chair Subani Chandra and Vice-Chair Aneesa Das were exactly the people we needed at the helm for this all-important return to in-person meetings, and I cannot thank them enough for their creativity, effort, and leadership in bringing CHEST 2022 to fruition. And while I expect to have been seven-for-seven in my predictions above, I do hope I got that NPH one wrong.

The other reason that this column was a challenge to craft is because it represents my final formal presidential missive in these esteemed pages. And as I planned this final walk of the path, I gave careful consideration to the message with which I wanted to conclude my year. And as I put together my predictions for the future, my mind also turned to the past, considering things I wish I had known (or spent more time considering) as I started this journey. Some of this information may prove useful to the next generation of CHEST leaders, and some may be already well engrained for those of you with leadership experience. Here, in no particular order, are some thoughts for those of you in the audience who are considering future leadership opportunities at CHEST (or elsewhere in life; I suspect some of this advice is applicable to other venues). That said, the recommendations also come from yours truly, so take them with an appropriately large grain of salt, as your mileage may vary, and reasonable people could take issue here or there.

- The most important conversations should happen in person. The past 3 years have shown us the amazing things that modern technology can accomplish, but when it comes to providing important information, asking for input on a crucial issue, or providing feedback on a sensitive matter, there is no adequate substitute for a discussion in which all parties are in the same room.

- You are going to get things wrong sometimes; sometimes, this is because there wasn’t a way to get a right answer, and sometimes it will be because you tried something that didn’t work. You will learn far more from one of these experiences than from a dozen things that went as well as (or better than) expected.

- It is profoundly difficult to change someone’s mind if you aren’t interacting with them. I believe there is no gap so large that warrants breakdown of communication. Going that extra mile to talk to people who have a drastically different opinion than your own is the only way that you might be able to change someone’s mind and is a great way to ensure that your own opinion withstands pushback. With the growth of social media over the last decade, we’ve gotten very good at blocking people on social media; while this can sometimes be good (or even necessary) for emotional well-being, there can be value to interacting with such folks in a real-world environment.

- You do not have to bring everything to the table. The best leaders surround themselves with other really smart folks who, in aggregate, will provide support in areas in which you are deficient. That said, you need to know where these gaps in your knowledge and experience are, and when it is the right time to listen to those trusted advisors.

- When it comes time to identify folks for your “cabinet,” make sure to choose people who think differently than you and who may disagree with you on some fundamental things. Surrounding yourself with friends and close colleagues can lead to groupthink and poor decision making. The best results often stem from challenging and difficult decision-making processes.

- As a corollary to the above, every leader will bring their own sensibility and personality to the role. Make sure to bring yours, even if it involves silly jokes about holding a medical meeting in a former President’s basement or getting another former President to eat a big spoonful of the aforementioned condiment.

- Fun is important. Fun builds relationships, and teams, and trust. Make sure you are having it, as much as you possibly can, throughout your leadership tenure.

On that note, I will sign off for good, at least in these pages. I’ll still be bumbling around, proposing new educational experiences, hosting Pardon the Interruption, and serving as a sounding board for anyone who wants to chat. But I cannot wait to see what the next 3 years bring for our organization, under the leadership of Drs. Addrizzo-Harris, Buckley, and Howington. And for those of you who are just taking your first steps in leadership, and who will be following in their footsteps years down the road, I hope that you get just as much enjoyment from and fulfilment in the role of President as I have. #SchulmanOut

This is an odd column for me to write. First, because of the nature of print publication, this writing for the November issue is being crafted just before the annual meeting is to be held in Nashville. Therefore, while I have a pretty good sense of what is in store for CHEST 2022, I have yet to see the final product, or the audience’s reaction to it. However, I will make some bold predictions as to what occurred therein:

- Even in the context of 3 years of separation, thousands CHEST members gathered in droves to rekindle friendships and to experience the best education in pulmonary, critical care, and sleep medicine that the world has to offer, leading to our second-biggest meeting ever.

- Neil Pasricha’s presentation helped attendees rekindle the “Art of Happiness.”

- Hundreds of attendees participated in, and successfully solved, our newest escape room, “Starship Relics.”

- Our valued CHEST members were able to successfully thwart Dr. Didactic and save the future of educational innovation.

- “CHEST After Hours” trended on social media and will become a normal and highly-anticipated part of the CHEST meeting moving forward.

- The most uncomfortable moment of the meeting centered on mayonnaise; for those of you who know what I am referencing, I am a little sorry…but only a little.

- Despite my best efforts, we were not able to recruit Neil Patrick Harris to participate.

Predicting the future of medical meetings is something we’ve spent a lot of time trying to do over the last year as we developed plans for CHEST 2022. But given the talented individuals involved in that planning, foreseeing the meeting’s success did not require any time travel; it was hardly a difficult task at all. Program Chair Subani Chandra and Vice-Chair Aneesa Das were exactly the people we needed at the helm for this all-important return to in-person meetings, and I cannot thank them enough for their creativity, effort, and leadership in bringing CHEST 2022 to fruition. And while I expect to have been seven-for-seven in my predictions above, I do hope I got that NPH one wrong.

The other reason that this column was a challenge to craft is because it represents my final formal presidential missive in these esteemed pages. And as I planned this final walk of the path, I gave careful consideration to the message with which I wanted to conclude my year. And as I put together my predictions for the future, my mind also turned to the past, considering things I wish I had known (or spent more time considering) as I started this journey. Some of this information may prove useful to the next generation of CHEST leaders, and some may be already well engrained for those of you with leadership experience. Here, in no particular order, are some thoughts for those of you in the audience who are considering future leadership opportunities at CHEST (or elsewhere in life; I suspect some of this advice is applicable to other venues). That said, the recommendations also come from yours truly, so take them with an appropriately large grain of salt, as your mileage may vary, and reasonable people could take issue here or there.

- The most important conversations should happen in person. The past 3 years have shown us the amazing things that modern technology can accomplish, but when it comes to providing important information, asking for input on a crucial issue, or providing feedback on a sensitive matter, there is no adequate substitute for a discussion in which all parties are in the same room.

- You are going to get things wrong sometimes; sometimes, this is because there wasn’t a way to get a right answer, and sometimes it will be because you tried something that didn’t work. You will learn far more from one of these experiences than from a dozen things that went as well as (or better than) expected.

- It is profoundly difficult to change someone’s mind if you aren’t interacting with them. I believe there is no gap so large that warrants breakdown of communication. Going that extra mile to talk to people who have a drastically different opinion than your own is the only way that you might be able to change someone’s mind and is a great way to ensure that your own opinion withstands pushback. With the growth of social media over the last decade, we’ve gotten very good at blocking people on social media; while this can sometimes be good (or even necessary) for emotional well-being, there can be value to interacting with such folks in a real-world environment.

- You do not have to bring everything to the table. The best leaders surround themselves with other really smart folks who, in aggregate, will provide support in areas in which you are deficient. That said, you need to know where these gaps in your knowledge and experience are, and when it is the right time to listen to those trusted advisors.

- When it comes time to identify folks for your “cabinet,” make sure to choose people who think differently than you and who may disagree with you on some fundamental things. Surrounding yourself with friends and close colleagues can lead to groupthink and poor decision making. The best results often stem from challenging and difficult decision-making processes.

- As a corollary to the above, every leader will bring their own sensibility and personality to the role. Make sure to bring yours, even if it involves silly jokes about holding a medical meeting in a former President’s basement or getting another former President to eat a big spoonful of the aforementioned condiment.

- Fun is important. Fun builds relationships, and teams, and trust. Make sure you are having it, as much as you possibly can, throughout your leadership tenure.

On that note, I will sign off for good, at least in these pages. I’ll still be bumbling around, proposing new educational experiences, hosting Pardon the Interruption, and serving as a sounding board for anyone who wants to chat. But I cannot wait to see what the next 3 years bring for our organization, under the leadership of Drs. Addrizzo-Harris, Buckley, and Howington. And for those of you who are just taking your first steps in leadership, and who will be following in their footsteps years down the road, I hope that you get just as much enjoyment from and fulfilment in the role of President as I have. #SchulmanOut

This is an odd column for me to write. First, because of the nature of print publication, this writing for the November issue is being crafted just before the annual meeting is to be held in Nashville. Therefore, while I have a pretty good sense of what is in store for CHEST 2022, I have yet to see the final product, or the audience’s reaction to it. However, I will make some bold predictions as to what occurred therein:

- Even in the context of 3 years of separation, thousands CHEST members gathered in droves to rekindle friendships and to experience the best education in pulmonary, critical care, and sleep medicine that the world has to offer, leading to our second-biggest meeting ever.

- Neil Pasricha’s presentation helped attendees rekindle the “Art of Happiness.”

- Hundreds of attendees participated in, and successfully solved, our newest escape room, “Starship Relics.”

- Our valued CHEST members were able to successfully thwart Dr. Didactic and save the future of educational innovation.

- “CHEST After Hours” trended on social media and will become a normal and highly-anticipated part of the CHEST meeting moving forward.

- The most uncomfortable moment of the meeting centered on mayonnaise; for those of you who know what I am referencing, I am a little sorry…but only a little.

- Despite my best efforts, we were not able to recruit Neil Patrick Harris to participate.

Predicting the future of medical meetings is something we’ve spent a lot of time trying to do over the last year as we developed plans for CHEST 2022. But given the talented individuals involved in that planning, foreseeing the meeting’s success did not require any time travel; it was hardly a difficult task at all. Program Chair Subani Chandra and Vice-Chair Aneesa Das were exactly the people we needed at the helm for this all-important return to in-person meetings, and I cannot thank them enough for their creativity, effort, and leadership in bringing CHEST 2022 to fruition. And while I expect to have been seven-for-seven in my predictions above, I do hope I got that NPH one wrong.

The other reason that this column was a challenge to craft is because it represents my final formal presidential missive in these esteemed pages. And as I planned this final walk of the path, I gave careful consideration to the message with which I wanted to conclude my year. And as I put together my predictions for the future, my mind also turned to the past, considering things I wish I had known (or spent more time considering) as I started this journey. Some of this information may prove useful to the next generation of CHEST leaders, and some may be already well engrained for those of you with leadership experience. Here, in no particular order, are some thoughts for those of you in the audience who are considering future leadership opportunities at CHEST (or elsewhere in life; I suspect some of this advice is applicable to other venues). That said, the recommendations also come from yours truly, so take them with an appropriately large grain of salt, as your mileage may vary, and reasonable people could take issue here or there.

- The most important conversations should happen in person. The past 3 years have shown us the amazing things that modern technology can accomplish, but when it comes to providing important information, asking for input on a crucial issue, or providing feedback on a sensitive matter, there is no adequate substitute for a discussion in which all parties are in the same room.

- You are going to get things wrong sometimes; sometimes, this is because there wasn’t a way to get a right answer, and sometimes it will be because you tried something that didn’t work. You will learn far more from one of these experiences than from a dozen things that went as well as (or better than) expected.

- It is profoundly difficult to change someone’s mind if you aren’t interacting with them. I believe there is no gap so large that warrants breakdown of communication. Going that extra mile to talk to people who have a drastically different opinion than your own is the only way that you might be able to change someone’s mind and is a great way to ensure that your own opinion withstands pushback. With the growth of social media over the last decade, we’ve gotten very good at blocking people on social media; while this can sometimes be good (or even necessary) for emotional well-being, there can be value to interacting with such folks in a real-world environment.

- You do not have to bring everything to the table. The best leaders surround themselves with other really smart folks who, in aggregate, will provide support in areas in which you are deficient. That said, you need to know where these gaps in your knowledge and experience are, and when it is the right time to listen to those trusted advisors.

- When it comes time to identify folks for your “cabinet,” make sure to choose people who think differently than you and who may disagree with you on some fundamental things. Surrounding yourself with friends and close colleagues can lead to groupthink and poor decision making. The best results often stem from challenging and difficult decision-making processes.

- As a corollary to the above, every leader will bring their own sensibility and personality to the role. Make sure to bring yours, even if it involves silly jokes about holding a medical meeting in a former President’s basement or getting another former President to eat a big spoonful of the aforementioned condiment.

- Fun is important. Fun builds relationships, and teams, and trust. Make sure you are having it, as much as you possibly can, throughout your leadership tenure.

On that note, I will sign off for good, at least in these pages. I’ll still be bumbling around, proposing new educational experiences, hosting Pardon the Interruption, and serving as a sounding board for anyone who wants to chat. But I cannot wait to see what the next 3 years bring for our organization, under the leadership of Drs. Addrizzo-Harris, Buckley, and Howington. And for those of you who are just taking your first steps in leadership, and who will be following in their footsteps years down the road, I hope that you get just as much enjoyment from and fulfilment in the role of President as I have. #SchulmanOut

Inpatient sleep medicine: An invaluable service for hospital medicine

Estimates suggest that nearly 1 billion adults worldwide could have sleep apnea (Benjafield AV, et al. Lancet Respir Med. 2019;7[8]:687-698). Even with the current widespread use of portable sleep testing, cheap and innovative models of OSA care will need to be developed to address this growing epidemic. This fact is particularly true for communities with significant health disparities, as the evidence suggests diagnostic rates for OSA are extremely poor in these areas (Stansbury R, et al. J Clin Sleep Med. 2022;18[3]:817-824). Current models of care for OSA are predominantly outpatient based. Hospital sleep medicine offers a potential mechanism to capture patients with OSA who would otherwise go undiagnosed and potentially suffer adverse health outcomes from untreated disease.

What is hospital sleep medicine?

Hospital sleep medicine includes the evaluation and management of sleep disorders, including, but not limited to, insomnia, restless legs syndrome, and circadian rhythm disorders, in hospitalized patients. Our program centers around proactive screening and early recognition of sleep-disordered breathing (SDB). Patients at high risk for SDB are identified upon entry to the hospital. These individuals are educated about the disease process and how it impacts comorbid health conditions. Recommendations are provided to the primary team regarding the appropriate screening test for SDB; positive airway pressure trials; mask fitting and acclimation; and coordination with care management in the discharge process, including scheduling follow-up care and diagnostic sleep studies. This program has become an integral part of our comprehensive sleep program, which includes inpatient, outpatient, and sleep center care and utilizes a multidisciplinary team approach including sleep specialists, sleep technologists, respiratory therapists, nurses, information technology professionals, and discharge planners, as well as ambulatory sleep clinics and sleep laboratories.

Evidence for hospital sleep medicine

While there has been interest in hospital-based sleep medicine since 2000, the most well-validated clinical pathway was first described by Sharma and colleagues in 2015 (Sharma, et al. J Clin Sleep Med. 2015;11[7]:717-723). This initial application of a formal sleep program demonstrated a high prevalence of SDB in hospitalized adult patients and led to a substantial increase in SDB diagnoses in the system. Subsequent studies have demonstrated improved outcomes, particularly in patients with cardiopulmonary disease. For example, there are data to suggest that hospitalized patients with congestive heart failure or COPD have increased rates of readmission, and early diagnosis and intervention are associated with decreased rates of subsequent readmission and ED visits (Konikkara J, et al. Hosp Pract. 2016;44[1]:41-47; Sharma S, et al. Am J Cardiol. 2016;117[6]:940-945). Long-term data also suggest survival benefit (Sharma S, et al. Am J Med. 2017;130[10]:1184-1191). Adherence to inpatient PAP trials has also been shown to predict outpatient follow-up and adherence to PAP therapy (Sharma S, et al. Sleep Breath. 2022; published online June 18, 2022).

Establishing a team

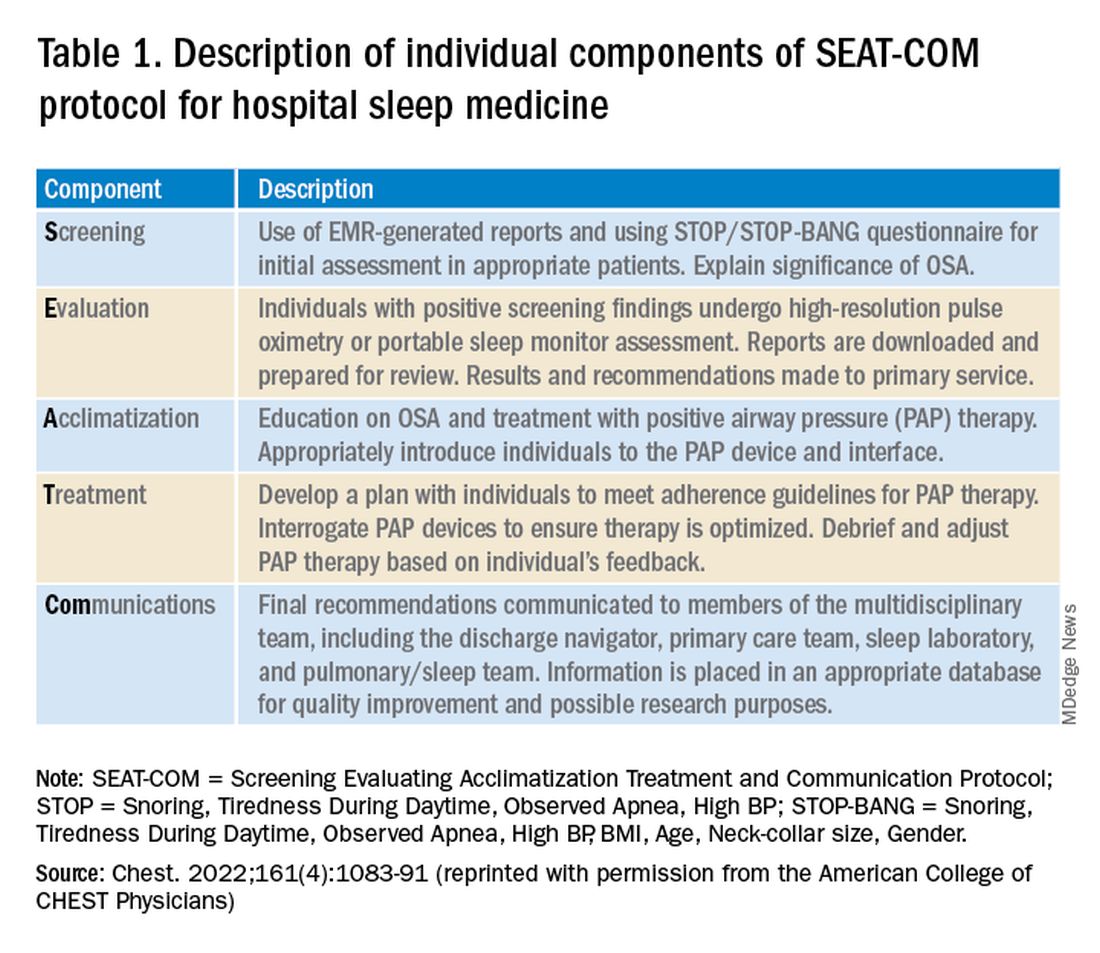

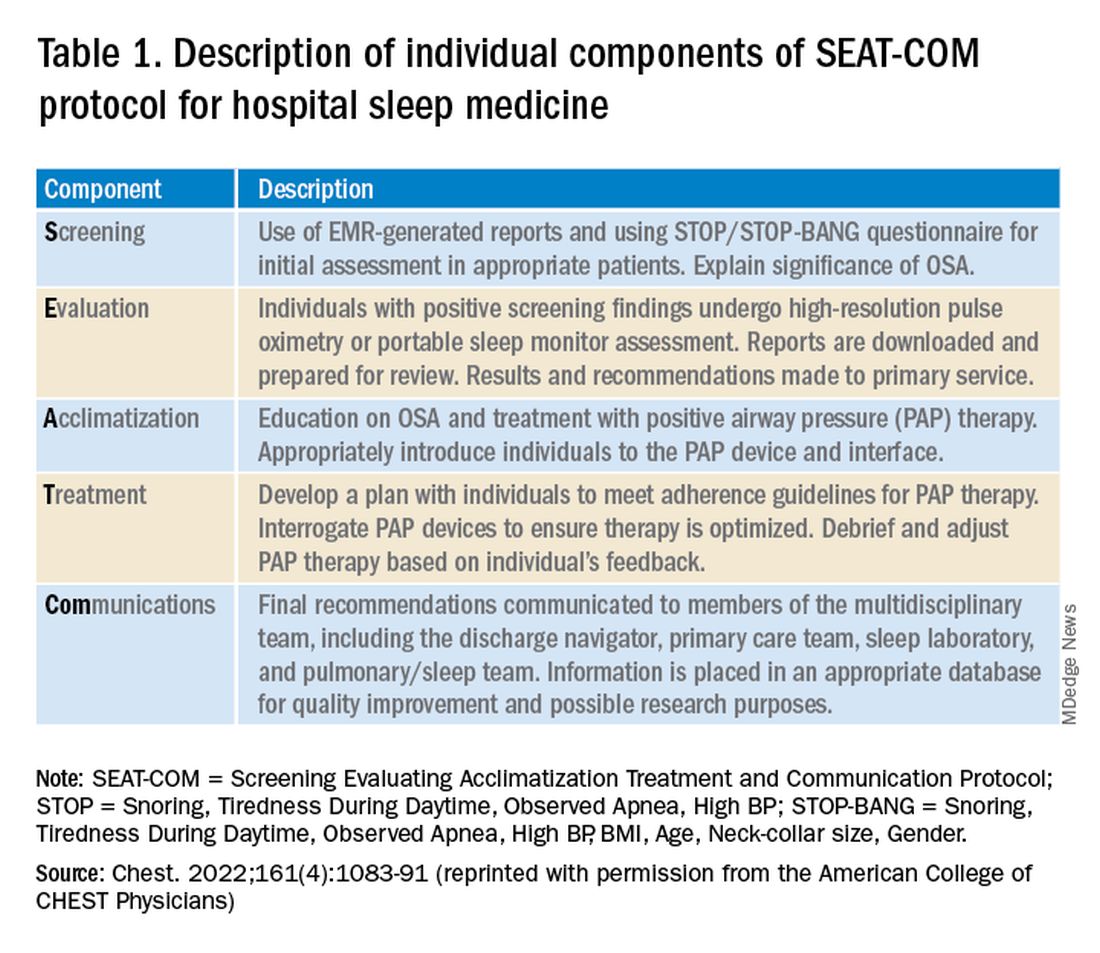

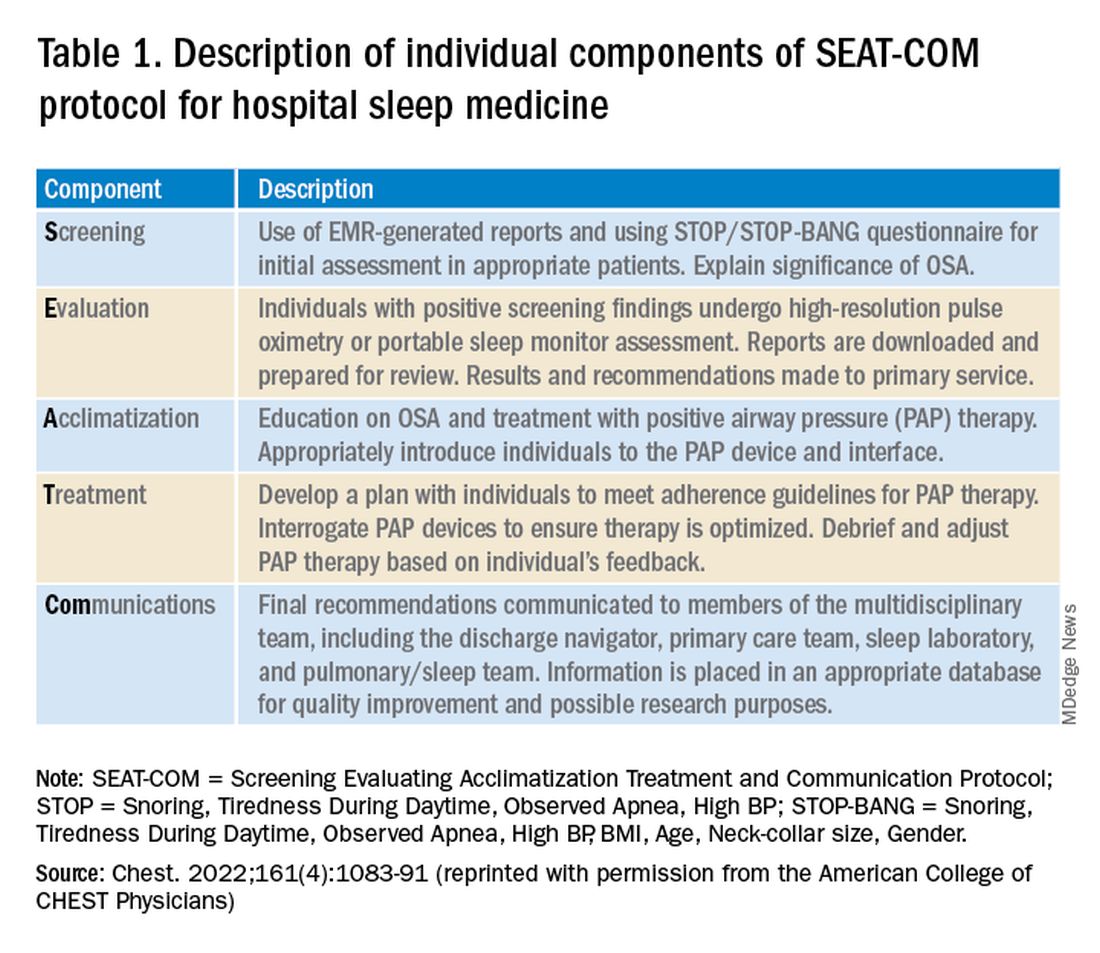

Establishing a hospital sleep medicine program requires upfront investment and training and begins with educating key stakeholders. Support from executive administration and various departments including respiratory, sleep medicine, information technology, nursing, physicians, mid-level providers, and discharge planning is essential. Data are available, as outlined here, showing significant improvement in patient outcomes with a hospital sleep medicine program. This information can garner significant enthusiasm from leadership to support the initiation of a program. A more detailed account of key program elements, inpatient protocols, and technologies utilized is available in our recent review (Sharma S, Stansbury R. Chest. 2022;161[4]:1083-1091). Table 1 from this article is highlighted here and outlines the essential components (SEAT-COM) of our hospital sleep medicine model. While each component of this model is important, we stress the importance of care coordination, timely diagnostic testing, and treatment, as significant delays can lead to inadequate time for acclimatization and optimization of therapy. It is important to note that the practice of hospital sleep medicine does not supplant clinic-based approaches, but rather serves to facilitate and enhance outpatient diagnosis and treatment.

Current questions

Data to date suggest a hospital sleep medicine program positively influences important clinical endpoints in hospitalized patients identified to be at risk for SDB. However, much of the published research is based on retrospective and prospective analysis of established clinical programs. Further, most studies have been completed at large, urban-based academic medical centers. Our group has recently completed a validation study in our local rural population, but larger multicenter trials involving more diverse communities and health systems are needed to better understand outcomes and further refine the optimal timing of screening and intervention for SDB in hospitalized patients (Stansbury, et al. Sleep Breath. 2022; published online January 20, 2022).

A common question that arises is the program’s impact regarding payment for rendered service in the context of Medicare’s prospective payment system. Given that the program focuses on screening for SDB and does not utilize formal testing for diagnosis, there is no additional cost for diagnostic tests or procedural codes. Thus, the diagnosis-related group is not impacted (Sharma S, Stansbury R. Chest. 2022;161[4]:1083-1091). Importantly, hospital sleep medicine has the potential for cost savings given the reduction in hospital readmissions and decreased adverse events during a patient’s hospital stay. The economics of the initial investment in a hospital sleep program versus potential savings from improved patient outcomes warrants evaluation.

Conclusion

SDB is a prevalent disorder with potential deleterious impacts on a patient’s health. Despite this, it is underrecognized and, thus, undertreated. Hospital sleep medicine is a growing model of care that may expand our capability for early diagnosis and intervention. Studies have demonstrated benefits to patients, particularly those with cardiopulmonary disease. However, additional studies are required to further validate hospital-based sleep medicine in more diverse populations and environments.

Dr. Del Prado Rico and Dr. Stansbury are with the Division of Pulmonary, Critical Care, and Sleep Medicine, Department of Medicine, Health Science Center North, West Virginia University. Dr. Stansbury is also with the Division of Pulmonary, Allergy, and Critical Care Medicine, Department of Medicine, University of Pittsburgh.

Estimates suggest that nearly 1 billion adults worldwide could have sleep apnea (Benjafield AV, et al. Lancet Respir Med. 2019;7[8]:687-698). Even with the current widespread use of portable sleep testing, cheap and innovative models of OSA care will need to be developed to address this growing epidemic. This fact is particularly true for communities with significant health disparities, as the evidence suggests diagnostic rates for OSA are extremely poor in these areas (Stansbury R, et al. J Clin Sleep Med. 2022;18[3]:817-824). Current models of care for OSA are predominantly outpatient based. Hospital sleep medicine offers a potential mechanism to capture patients with OSA who would otherwise go undiagnosed and potentially suffer adverse health outcomes from untreated disease.

What is hospital sleep medicine?

Hospital sleep medicine includes the evaluation and management of sleep disorders, including, but not limited to, insomnia, restless legs syndrome, and circadian rhythm disorders, in hospitalized patients. Our program centers around proactive screening and early recognition of sleep-disordered breathing (SDB). Patients at high risk for SDB are identified upon entry to the hospital. These individuals are educated about the disease process and how it impacts comorbid health conditions. Recommendations are provided to the primary team regarding the appropriate screening test for SDB; positive airway pressure trials; mask fitting and acclimation; and coordination with care management in the discharge process, including scheduling follow-up care and diagnostic sleep studies. This program has become an integral part of our comprehensive sleep program, which includes inpatient, outpatient, and sleep center care and utilizes a multidisciplinary team approach including sleep specialists, sleep technologists, respiratory therapists, nurses, information technology professionals, and discharge planners, as well as ambulatory sleep clinics and sleep laboratories.

Evidence for hospital sleep medicine

While there has been interest in hospital-based sleep medicine since 2000, the most well-validated clinical pathway was first described by Sharma and colleagues in 2015 (Sharma, et al. J Clin Sleep Med. 2015;11[7]:717-723). This initial application of a formal sleep program demonstrated a high prevalence of SDB in hospitalized adult patients and led to a substantial increase in SDB diagnoses in the system. Subsequent studies have demonstrated improved outcomes, particularly in patients with cardiopulmonary disease. For example, there are data to suggest that hospitalized patients with congestive heart failure or COPD have increased rates of readmission, and early diagnosis and intervention are associated with decreased rates of subsequent readmission and ED visits (Konikkara J, et al. Hosp Pract. 2016;44[1]:41-47; Sharma S, et al. Am J Cardiol. 2016;117[6]:940-945). Long-term data also suggest survival benefit (Sharma S, et al. Am J Med. 2017;130[10]:1184-1191). Adherence to inpatient PAP trials has also been shown to predict outpatient follow-up and adherence to PAP therapy (Sharma S, et al. Sleep Breath. 2022; published online June 18, 2022).

Establishing a team

Establishing a hospital sleep medicine program requires upfront investment and training and begins with educating key stakeholders. Support from executive administration and various departments including respiratory, sleep medicine, information technology, nursing, physicians, mid-level providers, and discharge planning is essential. Data are available, as outlined here, showing significant improvement in patient outcomes with a hospital sleep medicine program. This information can garner significant enthusiasm from leadership to support the initiation of a program. A more detailed account of key program elements, inpatient protocols, and technologies utilized is available in our recent review (Sharma S, Stansbury R. Chest. 2022;161[4]:1083-1091). Table 1 from this article is highlighted here and outlines the essential components (SEAT-COM) of our hospital sleep medicine model. While each component of this model is important, we stress the importance of care coordination, timely diagnostic testing, and treatment, as significant delays can lead to inadequate time for acclimatization and optimization of therapy. It is important to note that the practice of hospital sleep medicine does not supplant clinic-based approaches, but rather serves to facilitate and enhance outpatient diagnosis and treatment.

Current questions

Data to date suggest a hospital sleep medicine program positively influences important clinical endpoints in hospitalized patients identified to be at risk for SDB. However, much of the published research is based on retrospective and prospective analysis of established clinical programs. Further, most studies have been completed at large, urban-based academic medical centers. Our group has recently completed a validation study in our local rural population, but larger multicenter trials involving more diverse communities and health systems are needed to better understand outcomes and further refine the optimal timing of screening and intervention for SDB in hospitalized patients (Stansbury, et al. Sleep Breath. 2022; published online January 20, 2022).

A common question that arises is the program’s impact regarding payment for rendered service in the context of Medicare’s prospective payment system. Given that the program focuses on screening for SDB and does not utilize formal testing for diagnosis, there is no additional cost for diagnostic tests or procedural codes. Thus, the diagnosis-related group is not impacted (Sharma S, Stansbury R. Chest. 2022;161[4]:1083-1091). Importantly, hospital sleep medicine has the potential for cost savings given the reduction in hospital readmissions and decreased adverse events during a patient’s hospital stay. The economics of the initial investment in a hospital sleep program versus potential savings from improved patient outcomes warrants evaluation.

Conclusion