User login

Miss the MIPS Webinar? View it Online

The SVS Patient Safety Organization and M2S, in conjunction with the SVS, presented a webinar last month on getting started in the Medicare reimbursement program, including the Merit-based Incentive Payment System (MIPS).

For those who couldn't attend, it is posted, along with the presentation slides, on the Vascular Quality Initiative website's home page. View it today to get up to speed on MIPS and MACRA (Medicare Access and CHIP Reauthorization Act of 2015).

The SVS Patient Safety Organization and M2S, in conjunction with the SVS, presented a webinar last month on getting started in the Medicare reimbursement program, including the Merit-based Incentive Payment System (MIPS).

For those who couldn't attend, it is posted, along with the presentation slides, on the Vascular Quality Initiative website's home page. View it today to get up to speed on MIPS and MACRA (Medicare Access and CHIP Reauthorization Act of 2015).

The SVS Patient Safety Organization and M2S, in conjunction with the SVS, presented a webinar last month on getting started in the Medicare reimbursement program, including the Merit-based Incentive Payment System (MIPS).

For those who couldn't attend, it is posted, along with the presentation slides, on the Vascular Quality Initiative website's home page. View it today to get up to speed on MIPS and MACRA (Medicare Access and CHIP Reauthorization Act of 2015).

Purchase VAM Online Library Today

Did you leave San Diego and VAM before the joint aortic summit on Saturday afternoon? Because you were at the breakfast session on aging vascular surgeons, did you miss the one on managing arterial infections? The On-Demand Library can help.

See the sessions you missed and review those you'd like to cover again. The On-Demand Library includes access for one year of audio-synced slides and presentations of many sessions at the 2017 Vascular Annual Meeting. Materials can even be downloaded.

Buy this invaluable resource today. Cost is $199 for those who attended VAM and $499 for all others.

Did you leave San Diego and VAM before the joint aortic summit on Saturday afternoon? Because you were at the breakfast session on aging vascular surgeons, did you miss the one on managing arterial infections? The On-Demand Library can help.

See the sessions you missed and review those you'd like to cover again. The On-Demand Library includes access for one year of audio-synced slides and presentations of many sessions at the 2017 Vascular Annual Meeting. Materials can even be downloaded.

Buy this invaluable resource today. Cost is $199 for those who attended VAM and $499 for all others.

Did you leave San Diego and VAM before the joint aortic summit on Saturday afternoon? Because you were at the breakfast session on aging vascular surgeons, did you miss the one on managing arterial infections? The On-Demand Library can help.

See the sessions you missed and review those you'd like to cover again. The On-Demand Library includes access for one year of audio-synced slides and presentations of many sessions at the 2017 Vascular Annual Meeting. Materials can even be downloaded.

Buy this invaluable resource today. Cost is $199 for those who attended VAM and $499 for all others.

Catching Up With Our CHEST Past Presidents

Where are they now? What have they been up to? CHEST’s Past Presidents each forged the way for the many successes of the American College of Chest Physicians, leading to enhanced patient care around the globe. Their outstanding leadership and vision are evidenced today in many of CHEST’s strategic initiatives. Let’s check in with Dr. Goldberg.

I arrived in Toronto in 1998 to start my term as President of the American College of Chest Physicians. (I had always loved Toronto, where I had spent months training in pediatric critical care at “Sick Kids” [Toronto’s Children’s Hospital] and collaborating with Audrey King on disability issues and public policy in Ontario.) CHEST 1998 in Toronto was equally exciting. What I remember - with humility – was that being CHEST President is not about “you.” It is about “The President,” who is honored and revered by all members for what CHEST truly represents … excellence in health-care education, communication, and information. Everyone came up to me to respect and honor the role … including awesome Past Presidents who lovingly shared their insights and experience and others (including many who became future presidents) to volunteer their assistance. I was in awe of these leaders and how they demonstrated selfless service.

And so I began my year of presidential service leadership. What I remember best is the respect all around the world for CHEST and what it does to unite people into actions that improve health globally. The President serves CHEST members to facilitate working together, which makes a difference. My presidential year culminated in the 65th anniversary conference in Chicago in 1999. All year, I had worked with my mentor (C. Everett Koop, MD, FCCP(Hon), to plan an opening ceremony that would be inspirational and unforgettable. For years, we had shared personal/private conversations. This time, we planned to communicate in public to inspire others and help them understand key issues we considered critical for the future of health care and global health.

Soon after my Presidential term, I took 2 years off for sabbatical to work more closely with Dr. Koop (2000-2002). Then, I retired to continue to focus on our work together and as personal caregiver for my wife, Evi Faure, MD, FCCP. Dr. Koop and I met many times and also held more public presentations, including the 2003 Surgeons’ General National Meeting on Overcoming Health Disparities at Howard University arranged with CHEST Past President Dr. Alvin Thomas.

All our joint efforts focused on the importance of Communication in Health Care. We shared the belief that communication of health information would create the “informed patient and family” who would then work together in partnership with health-care professional team members. We thought that this would be the best way to improve and reform health-care delivery. We sought to provide information (the “what”) in ways that it would be trusted, understandable, and easily usable (the “how) for patients and famili

My greatest learning was the importance of mentorship – both for the mentor and mentee. This fosters communication that enables learning and growth in our abilities to serve others by the profession we love.

http://www.chestnet.org/News/Blogs/CHEST-Thought-Leaders/2013/06/Dr-Koops-Legacy-Reflections-on-Mentorship

http://www.chestnet.org/News/Blogs/CHEST-Thought-Leaders/2013/08/The-Legacy-of-Dr-Koop-Reflections-on-Our-Fireside-Chat

Where are they now? What have they been up to? CHEST’s Past Presidents each forged the way for the many successes of the American College of Chest Physicians, leading to enhanced patient care around the globe. Their outstanding leadership and vision are evidenced today in many of CHEST’s strategic initiatives. Let’s check in with Dr. Goldberg.

I arrived in Toronto in 1998 to start my term as President of the American College of Chest Physicians. (I had always loved Toronto, where I had spent months training in pediatric critical care at “Sick Kids” [Toronto’s Children’s Hospital] and collaborating with Audrey King on disability issues and public policy in Ontario.) CHEST 1998 in Toronto was equally exciting. What I remember - with humility – was that being CHEST President is not about “you.” It is about “The President,” who is honored and revered by all members for what CHEST truly represents … excellence in health-care education, communication, and information. Everyone came up to me to respect and honor the role … including awesome Past Presidents who lovingly shared their insights and experience and others (including many who became future presidents) to volunteer their assistance. I was in awe of these leaders and how they demonstrated selfless service.

And so I began my year of presidential service leadership. What I remember best is the respect all around the world for CHEST and what it does to unite people into actions that improve health globally. The President serves CHEST members to facilitate working together, which makes a difference. My presidential year culminated in the 65th anniversary conference in Chicago in 1999. All year, I had worked with my mentor (C. Everett Koop, MD, FCCP(Hon), to plan an opening ceremony that would be inspirational and unforgettable. For years, we had shared personal/private conversations. This time, we planned to communicate in public to inspire others and help them understand key issues we considered critical for the future of health care and global health.

Soon after my Presidential term, I took 2 years off for sabbatical to work more closely with Dr. Koop (2000-2002). Then, I retired to continue to focus on our work together and as personal caregiver for my wife, Evi Faure, MD, FCCP. Dr. Koop and I met many times and also held more public presentations, including the 2003 Surgeons’ General National Meeting on Overcoming Health Disparities at Howard University arranged with CHEST Past President Dr. Alvin Thomas.

All our joint efforts focused on the importance of Communication in Health Care. We shared the belief that communication of health information would create the “informed patient and family” who would then work together in partnership with health-care professional team members. We thought that this would be the best way to improve and reform health-care delivery. We sought to provide information (the “what”) in ways that it would be trusted, understandable, and easily usable (the “how) for patients and famili

My greatest learning was the importance of mentorship – both for the mentor and mentee. This fosters communication that enables learning and growth in our abilities to serve others by the profession we love.

http://www.chestnet.org/News/Blogs/CHEST-Thought-Leaders/2013/06/Dr-Koops-Legacy-Reflections-on-Mentorship

http://www.chestnet.org/News/Blogs/CHEST-Thought-Leaders/2013/08/The-Legacy-of-Dr-Koop-Reflections-on-Our-Fireside-Chat

Where are they now? What have they been up to? CHEST’s Past Presidents each forged the way for the many successes of the American College of Chest Physicians, leading to enhanced patient care around the globe. Their outstanding leadership and vision are evidenced today in many of CHEST’s strategic initiatives. Let’s check in with Dr. Goldberg.

I arrived in Toronto in 1998 to start my term as President of the American College of Chest Physicians. (I had always loved Toronto, where I had spent months training in pediatric critical care at “Sick Kids” [Toronto’s Children’s Hospital] and collaborating with Audrey King on disability issues and public policy in Ontario.) CHEST 1998 in Toronto was equally exciting. What I remember - with humility – was that being CHEST President is not about “you.” It is about “The President,” who is honored and revered by all members for what CHEST truly represents … excellence in health-care education, communication, and information. Everyone came up to me to respect and honor the role … including awesome Past Presidents who lovingly shared their insights and experience and others (including many who became future presidents) to volunteer their assistance. I was in awe of these leaders and how they demonstrated selfless service.

And so I began my year of presidential service leadership. What I remember best is the respect all around the world for CHEST and what it does to unite people into actions that improve health globally. The President serves CHEST members to facilitate working together, which makes a difference. My presidential year culminated in the 65th anniversary conference in Chicago in 1999. All year, I had worked with my mentor (C. Everett Koop, MD, FCCP(Hon), to plan an opening ceremony that would be inspirational and unforgettable. For years, we had shared personal/private conversations. This time, we planned to communicate in public to inspire others and help them understand key issues we considered critical for the future of health care and global health.

Soon after my Presidential term, I took 2 years off for sabbatical to work more closely with Dr. Koop (2000-2002). Then, I retired to continue to focus on our work together and as personal caregiver for my wife, Evi Faure, MD, FCCP. Dr. Koop and I met many times and also held more public presentations, including the 2003 Surgeons’ General National Meeting on Overcoming Health Disparities at Howard University arranged with CHEST Past President Dr. Alvin Thomas.

All our joint efforts focused on the importance of Communication in Health Care. We shared the belief that communication of health information would create the “informed patient and family” who would then work together in partnership with health-care professional team members. We thought that this would be the best way to improve and reform health-care delivery. We sought to provide information (the “what”) in ways that it would be trusted, understandable, and easily usable (the “how) for patients and famili

My greatest learning was the importance of mentorship – both for the mentor and mentee. This fosters communication that enables learning and growth in our abilities to serve others by the profession we love.

http://www.chestnet.org/News/Blogs/CHEST-Thought-Leaders/2013/06/Dr-Koops-Legacy-Reflections-on-Mentorship

http://www.chestnet.org/News/Blogs/CHEST-Thought-Leaders/2013/08/The-Legacy-of-Dr-Koop-Reflections-on-Our-Fireside-Chat

Pulmonary Perspectives ® Immigrants in Health Care

July 4th was bittersweet for me, this year. Independence days of my childhood were spent grilling, sitting by the campfire on the lakes and rivers of Northern Michigan, watching the fireworks turn the night sky red, white, and blue. These fond memories were a painful reminder that others like me may not have the privilege to experience such joy, secondary to their background.

I don’t remember the first time that I heard the tale of my parents coming to America. They were both medical students from India, who received brightly colored brochures from American hospitals inviting them to come further their medical training. Due to the deficit of physicians in the United States, the hospitals even loaned money to medical students, so they would do their residencies in America. My parents took advantage of this opportunity and embarked on a journey that would define their lives. Often, my mother would talk about my father leaving for the hospital on Friday morning only to return to his wife and two toddlers on Monday afternoon. As a child, I remember my uncles taking bottles of milk to the hospital to make chai to fuel through their grueling overnight calls. These immigrant tales were the backdrop of my childhood, the basis of my understanding of America. I was raised in an immigrant community of physicians who were grateful for the opportunities that America offered them. They worked hard, reaped significant rewards, and substantially contributed to their communities. Maybe, I am just nostalgic for my childhood, but this experience, I believe, is still an integral part of the American dream.

The recent choice to restrict immigration from specific nations is disturbing at best and reminiscent of an America that I have never known. More than 7,000 physicians from Libya, Iran, Somalia, Sudan, Syria, and Yemen are currently working in the United States, providing care for more than 14 million people. An estimated 94% of American communities have at least one doctor from one of the targeted countries. These physicians are more likely to work in rural and underserved communities and provide essential services.1 They are immigrants who have come to America to better their lives and, in turn, have bettered the lives of those around them. They are my parents. Not all physicians are good people or are worthy of the American dream, but America is a better place for welcoming those who are willing to work hard to make a better life for themselves. An important criticism of the effect of migration of medical professionals to the United States has been the loss of human capital to their respective nations, but never the ill-effect they have had on the nations they have emigrated to.

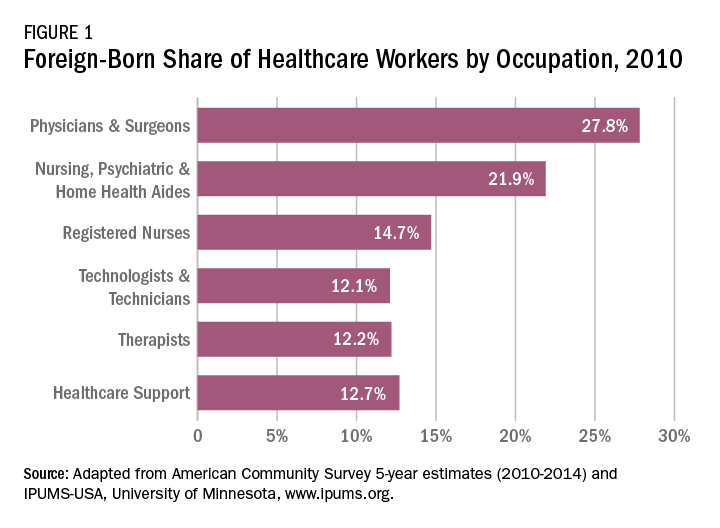

The 2015 Educational Commission for Foreign Medical Graduates (ECFMG) reported that a quarter of practicing physicians in the United States are international medical graduates (IMGs) and a fifth of all residency applicants were IMGs.2 Measuring the impact of the IMGs who have come to America is difficult to quantify but can be assessed by countless anecdotes and success stories. Forty-two percent of researchers at the seven top cancer research centers in the United States are immigrants. This is impressive considering that only about a tenth of the United States population is foreign born. Twenty-eight American Nobel prize winners in Medicine since 1960 are immigrants and taking a broader view as seen in Figure 1, almost 28% of physicians and 22% of RNs in the United States are foreign born.3,4 That does not take into account those like myself, first generation children who chose to enter this field of work out of respect for what their parents had accomplished.

The American College of Chest Physicians (CHEST), over the past 15 years, has had several Presidents who are American immigrants. One of them, Dr. Kalpalatha K. Guntupalli, President 2009-2010, I have met, and I was humbled by the experience. She is brilliant, kind, and modest and without her knowing, she has served as one of the role models for my career.

I applaud CHEST for standing with other member organizations to oppose the immigration hiatus (Letter to John F. Kelly, Secretary of Homeland Security. Feb 7, 2017). The medical organizations made four concrete proposals:

• Reinstate the Visa Interview Waiver Program, as the suspension of this program increases the risk for significant delays in new and renewal visa processing for trainees from any foreign country;

• Remove entry restrictions of physicians and medical students from the seven designated countries that have been approved for J-1, H-1B or F-1 visas;

• Allow affected physicians to obtain travel visas to visit the United States for medical conferences, as well as other medical and research related events; and

• Prioritize the admission of refugees with urgent medical needs who had already been checked and approved for entry prior to the executive order.

These recommendations were good but not broad enough. The decision to bar immigration for any period of time, from any country, is an affront to the American dream with long-lasting consequences, most importantly, the loss of health-care services to the American populace. My Congressman knows how I feel about this, does yours?

1. Fivethirtyeight.com/features/trumps-new-travel-ban-could-affect-doctors-especially-in-the-rust-belt-and-appalachia/.Accessed July 18, 2017.

2. Masri A, Senussi MH. Trump’s executive order on immigration—detrimental effects on medical training and health care. N Engl J Med. 2017; 376(19): e39.

3. http://www.immigrationresearch-info.org/report/immigrant-learning-center-inc/immigrants-health-care-keeping-americans-healthy-through-care-a.Accessed July 27, 2017.

4. http://www.nfap.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/05/International-Educator.May-June-2015.pdf.Accessed July 27, 2017 (not available on Safari).

July 4th was bittersweet for me, this year. Independence days of my childhood were spent grilling, sitting by the campfire on the lakes and rivers of Northern Michigan, watching the fireworks turn the night sky red, white, and blue. These fond memories were a painful reminder that others like me may not have the privilege to experience such joy, secondary to their background.

I don’t remember the first time that I heard the tale of my parents coming to America. They were both medical students from India, who received brightly colored brochures from American hospitals inviting them to come further their medical training. Due to the deficit of physicians in the United States, the hospitals even loaned money to medical students, so they would do their residencies in America. My parents took advantage of this opportunity and embarked on a journey that would define their lives. Often, my mother would talk about my father leaving for the hospital on Friday morning only to return to his wife and two toddlers on Monday afternoon. As a child, I remember my uncles taking bottles of milk to the hospital to make chai to fuel through their grueling overnight calls. These immigrant tales were the backdrop of my childhood, the basis of my understanding of America. I was raised in an immigrant community of physicians who were grateful for the opportunities that America offered them. They worked hard, reaped significant rewards, and substantially contributed to their communities. Maybe, I am just nostalgic for my childhood, but this experience, I believe, is still an integral part of the American dream.

The recent choice to restrict immigration from specific nations is disturbing at best and reminiscent of an America that I have never known. More than 7,000 physicians from Libya, Iran, Somalia, Sudan, Syria, and Yemen are currently working in the United States, providing care for more than 14 million people. An estimated 94% of American communities have at least one doctor from one of the targeted countries. These physicians are more likely to work in rural and underserved communities and provide essential services.1 They are immigrants who have come to America to better their lives and, in turn, have bettered the lives of those around them. They are my parents. Not all physicians are good people or are worthy of the American dream, but America is a better place for welcoming those who are willing to work hard to make a better life for themselves. An important criticism of the effect of migration of medical professionals to the United States has been the loss of human capital to their respective nations, but never the ill-effect they have had on the nations they have emigrated to.

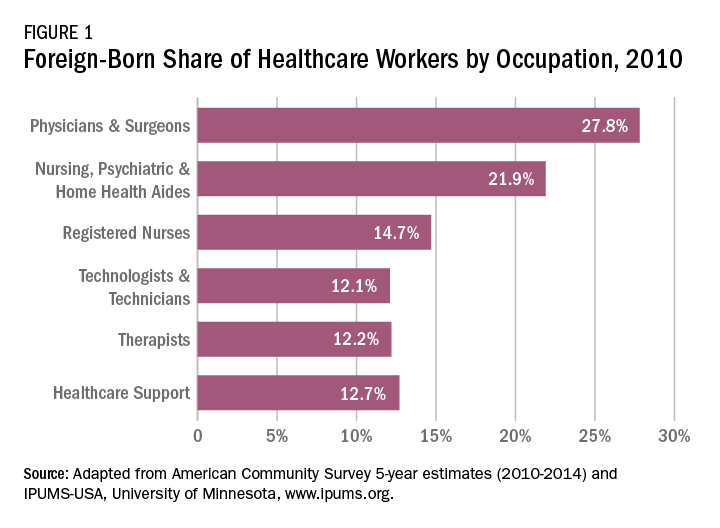

The 2015 Educational Commission for Foreign Medical Graduates (ECFMG) reported that a quarter of practicing physicians in the United States are international medical graduates (IMGs) and a fifth of all residency applicants were IMGs.2 Measuring the impact of the IMGs who have come to America is difficult to quantify but can be assessed by countless anecdotes and success stories. Forty-two percent of researchers at the seven top cancer research centers in the United States are immigrants. This is impressive considering that only about a tenth of the United States population is foreign born. Twenty-eight American Nobel prize winners in Medicine since 1960 are immigrants and taking a broader view as seen in Figure 1, almost 28% of physicians and 22% of RNs in the United States are foreign born.3,4 That does not take into account those like myself, first generation children who chose to enter this field of work out of respect for what their parents had accomplished.

The American College of Chest Physicians (CHEST), over the past 15 years, has had several Presidents who are American immigrants. One of them, Dr. Kalpalatha K. Guntupalli, President 2009-2010, I have met, and I was humbled by the experience. She is brilliant, kind, and modest and without her knowing, she has served as one of the role models for my career.

I applaud CHEST for standing with other member organizations to oppose the immigration hiatus (Letter to John F. Kelly, Secretary of Homeland Security. Feb 7, 2017). The medical organizations made four concrete proposals:

• Reinstate the Visa Interview Waiver Program, as the suspension of this program increases the risk for significant delays in new and renewal visa processing for trainees from any foreign country;

• Remove entry restrictions of physicians and medical students from the seven designated countries that have been approved for J-1, H-1B or F-1 visas;

• Allow affected physicians to obtain travel visas to visit the United States for medical conferences, as well as other medical and research related events; and

• Prioritize the admission of refugees with urgent medical needs who had already been checked and approved for entry prior to the executive order.

These recommendations were good but not broad enough. The decision to bar immigration for any period of time, from any country, is an affront to the American dream with long-lasting consequences, most importantly, the loss of health-care services to the American populace. My Congressman knows how I feel about this, does yours?

1. Fivethirtyeight.com/features/trumps-new-travel-ban-could-affect-doctors-especially-in-the-rust-belt-and-appalachia/.Accessed July 18, 2017.

2. Masri A, Senussi MH. Trump’s executive order on immigration—detrimental effects on medical training and health care. N Engl J Med. 2017; 376(19): e39.

3. http://www.immigrationresearch-info.org/report/immigrant-learning-center-inc/immigrants-health-care-keeping-americans-healthy-through-care-a.Accessed July 27, 2017.

4. http://www.nfap.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/05/International-Educator.May-June-2015.pdf.Accessed July 27, 2017 (not available on Safari).

July 4th was bittersweet for me, this year. Independence days of my childhood were spent grilling, sitting by the campfire on the lakes and rivers of Northern Michigan, watching the fireworks turn the night sky red, white, and blue. These fond memories were a painful reminder that others like me may not have the privilege to experience such joy, secondary to their background.

I don’t remember the first time that I heard the tale of my parents coming to America. They were both medical students from India, who received brightly colored brochures from American hospitals inviting them to come further their medical training. Due to the deficit of physicians in the United States, the hospitals even loaned money to medical students, so they would do their residencies in America. My parents took advantage of this opportunity and embarked on a journey that would define their lives. Often, my mother would talk about my father leaving for the hospital on Friday morning only to return to his wife and two toddlers on Monday afternoon. As a child, I remember my uncles taking bottles of milk to the hospital to make chai to fuel through their grueling overnight calls. These immigrant tales were the backdrop of my childhood, the basis of my understanding of America. I was raised in an immigrant community of physicians who were grateful for the opportunities that America offered them. They worked hard, reaped significant rewards, and substantially contributed to their communities. Maybe, I am just nostalgic for my childhood, but this experience, I believe, is still an integral part of the American dream.

The recent choice to restrict immigration from specific nations is disturbing at best and reminiscent of an America that I have never known. More than 7,000 physicians from Libya, Iran, Somalia, Sudan, Syria, and Yemen are currently working in the United States, providing care for more than 14 million people. An estimated 94% of American communities have at least one doctor from one of the targeted countries. These physicians are more likely to work in rural and underserved communities and provide essential services.1 They are immigrants who have come to America to better their lives and, in turn, have bettered the lives of those around them. They are my parents. Not all physicians are good people or are worthy of the American dream, but America is a better place for welcoming those who are willing to work hard to make a better life for themselves. An important criticism of the effect of migration of medical professionals to the United States has been the loss of human capital to their respective nations, but never the ill-effect they have had on the nations they have emigrated to.

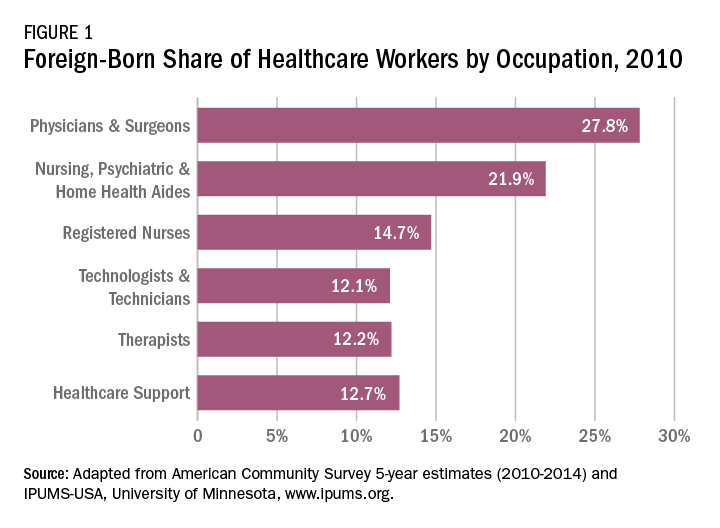

The 2015 Educational Commission for Foreign Medical Graduates (ECFMG) reported that a quarter of practicing physicians in the United States are international medical graduates (IMGs) and a fifth of all residency applicants were IMGs.2 Measuring the impact of the IMGs who have come to America is difficult to quantify but can be assessed by countless anecdotes and success stories. Forty-two percent of researchers at the seven top cancer research centers in the United States are immigrants. This is impressive considering that only about a tenth of the United States population is foreign born. Twenty-eight American Nobel prize winners in Medicine since 1960 are immigrants and taking a broader view as seen in Figure 1, almost 28% of physicians and 22% of RNs in the United States are foreign born.3,4 That does not take into account those like myself, first generation children who chose to enter this field of work out of respect for what their parents had accomplished.

The American College of Chest Physicians (CHEST), over the past 15 years, has had several Presidents who are American immigrants. One of them, Dr. Kalpalatha K. Guntupalli, President 2009-2010, I have met, and I was humbled by the experience. She is brilliant, kind, and modest and without her knowing, she has served as one of the role models for my career.

I applaud CHEST for standing with other member organizations to oppose the immigration hiatus (Letter to John F. Kelly, Secretary of Homeland Security. Feb 7, 2017). The medical organizations made four concrete proposals:

• Reinstate the Visa Interview Waiver Program, as the suspension of this program increases the risk for significant delays in new and renewal visa processing for trainees from any foreign country;

• Remove entry restrictions of physicians and medical students from the seven designated countries that have been approved for J-1, H-1B or F-1 visas;

• Allow affected physicians to obtain travel visas to visit the United States for medical conferences, as well as other medical and research related events; and

• Prioritize the admission of refugees with urgent medical needs who had already been checked and approved for entry prior to the executive order.

These recommendations were good but not broad enough. The decision to bar immigration for any period of time, from any country, is an affront to the American dream with long-lasting consequences, most importantly, the loss of health-care services to the American populace. My Congressman knows how I feel about this, does yours?

1. Fivethirtyeight.com/features/trumps-new-travel-ban-could-affect-doctors-especially-in-the-rust-belt-and-appalachia/.Accessed July 18, 2017.

2. Masri A, Senussi MH. Trump’s executive order on immigration—detrimental effects on medical training and health care. N Engl J Med. 2017; 376(19): e39.

3. http://www.immigrationresearch-info.org/report/immigrant-learning-center-inc/immigrants-health-care-keeping-americans-healthy-through-care-a.Accessed July 27, 2017.

4. http://www.nfap.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/05/International-Educator.May-June-2015.pdf.Accessed July 27, 2017 (not available on Safari).

Letter to CHEST Leaders, Members, and Friends

Dear CHEST Leaders, Members, and Friends:

The Forum of International Respiratory Societies (FIRS) is an organization comprised of the world’s leading international professional respiratory societies presenting a unifying voice to improve lung health globally. Its members are: the American College of Chest Physicians (CHEST), American Thoracic Society (ATS), Asian Pacific Society of Respirology (APSR), Asociación Latino Americana De Tórax (ALAT), European Respiratory Society (ERS), International Union Against Tuberculosis and Lung Diseases (The Union), the Pan African Thoracic Society (PATS), the Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD), and the Global Initiative for Asthma (GINA). FIRS has more than 70,000 professional members; the physicians and patients they serve magnify our efforts, allowing FIRS to speak for lung health on a global scale.

FIRS is working with the World Health Organization and the United Nations to make sure lung health is represented in national health agendas. FIRS’ position paper on electronic nicotine delivery systems was presented at a side-event at the United Nations High-Level Meeting (UNHL) in New York in 2014 and is now a world standard. At the recent World Health Assembly meeting (May 2017) in Geneva, FIRS launched its Global Impact of Lung Disease report that called for a global clean air standard, strong anti-tobacco laws, and better health care for patients with respiratory disease.

FIRS will be reviewing the new WHO Global Air Quality Guidelines and will help promote them globally through advocacy and messaging, as well as by providing air quality expertise. FIRS will be involved at the Coimbra meeting (Sept 26-29) on improving the urban environment, the Montevideo UN High-Level (UNHL) meeting on chronic disease (Oct 18-20), and the UN Ministerial Meeting in Moscow on tuberculosis, and it is preparing for the 2018 UNHL meetings on antibiotic drug resistance, tuberculosis, and chronic diseases.

At the World Health Assembly, FIRS proclaimed September 25 as World Lung Day and hopes to use this as a rallying point for advocacy related to respiratory health or air quality. Lung Disease is the only major chronic disease that does not have a World Day. FIRS produced a Charter for Lung Health (www.firsnet.org/publications/charter) and hopes to have 100,000 persons sign on to it. FIRS also seeks to have lung-health organizations sign on and develop activities that can be carried out to celebrate lung health. Uruguay was the first country to sign the charter. The logos of the organizations who have signed the charter are on the FIRS website at firsnet.org. Activities being planned include editorials, newsletters, and letters-to-the-editor articles, legislative proclamations, social media exposure, and free spirometry, smoking cessation guidance, and carbon monoxide testing, but FIRS is looking for many more ways to celebrate healthy lungs on September 25 and many more partners!

Sixty-five million people suffer from chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and 3 million die of it each year, making it the third leading cause of death worldwide; 10 million people develop tuberculosis and 1.4 million die of it each year, making it the most common deadly infectious disease; 1.6 million people die of lung cancer each year, making it the most deadly cancer; 334 million people suffer from asthma, making it the most common chronic disease of childhood; pneumonia kills millions of people each year, making it a leading cause of death in the very young and very old. At least 2 billion people are exposed to toxic indoor smoke; 1 billion inhale polluted outdoor air; and 1 billion are exposed to tobacco smoke, and the tragedy is that many conditions are getting worse. We cannot sit still and allow this to happen.

FIRS proposes a multipronged campaign to combat lung disease to bring together all people concerned with lung health. It starts with naming September 25 World Lung Day and calling on respiratory health organizations to pledge to improve lung health and help identify ways to celebrate this day.

Please sign up, and share this call for action with your professional, advocacy, and social networks, and those of your friends and families. Please do your part as global citizens to improve lung health. To do so, organizations should indicate they wish to sign on and send their logo to Betty Sax, FIRS Secretariat, [email protected]. Organizations should also encourage individuals to sign on and show that they are committed to increasing awareness and action to promote global lung health.

Thank you.

Gerard Silvestri, MD, MS, FCCP

CHEST President

Darcy Marciniuk, MD, FCCP

CHEST FIRS Liaison

Dear CHEST Leaders, Members, and Friends:

The Forum of International Respiratory Societies (FIRS) is an organization comprised of the world’s leading international professional respiratory societies presenting a unifying voice to improve lung health globally. Its members are: the American College of Chest Physicians (CHEST), American Thoracic Society (ATS), Asian Pacific Society of Respirology (APSR), Asociación Latino Americana De Tórax (ALAT), European Respiratory Society (ERS), International Union Against Tuberculosis and Lung Diseases (The Union), the Pan African Thoracic Society (PATS), the Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD), and the Global Initiative for Asthma (GINA). FIRS has more than 70,000 professional members; the physicians and patients they serve magnify our efforts, allowing FIRS to speak for lung health on a global scale.

FIRS is working with the World Health Organization and the United Nations to make sure lung health is represented in national health agendas. FIRS’ position paper on electronic nicotine delivery systems was presented at a side-event at the United Nations High-Level Meeting (UNHL) in New York in 2014 and is now a world standard. At the recent World Health Assembly meeting (May 2017) in Geneva, FIRS launched its Global Impact of Lung Disease report that called for a global clean air standard, strong anti-tobacco laws, and better health care for patients with respiratory disease.

FIRS will be reviewing the new WHO Global Air Quality Guidelines and will help promote them globally through advocacy and messaging, as well as by providing air quality expertise. FIRS will be involved at the Coimbra meeting (Sept 26-29) on improving the urban environment, the Montevideo UN High-Level (UNHL) meeting on chronic disease (Oct 18-20), and the UN Ministerial Meeting in Moscow on tuberculosis, and it is preparing for the 2018 UNHL meetings on antibiotic drug resistance, tuberculosis, and chronic diseases.

At the World Health Assembly, FIRS proclaimed September 25 as World Lung Day and hopes to use this as a rallying point for advocacy related to respiratory health or air quality. Lung Disease is the only major chronic disease that does not have a World Day. FIRS produced a Charter for Lung Health (www.firsnet.org/publications/charter) and hopes to have 100,000 persons sign on to it. FIRS also seeks to have lung-health organizations sign on and develop activities that can be carried out to celebrate lung health. Uruguay was the first country to sign the charter. The logos of the organizations who have signed the charter are on the FIRS website at firsnet.org. Activities being planned include editorials, newsletters, and letters-to-the-editor articles, legislative proclamations, social media exposure, and free spirometry, smoking cessation guidance, and carbon monoxide testing, but FIRS is looking for many more ways to celebrate healthy lungs on September 25 and many more partners!

Sixty-five million people suffer from chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and 3 million die of it each year, making it the third leading cause of death worldwide; 10 million people develop tuberculosis and 1.4 million die of it each year, making it the most common deadly infectious disease; 1.6 million people die of lung cancer each year, making it the most deadly cancer; 334 million people suffer from asthma, making it the most common chronic disease of childhood; pneumonia kills millions of people each year, making it a leading cause of death in the very young and very old. At least 2 billion people are exposed to toxic indoor smoke; 1 billion inhale polluted outdoor air; and 1 billion are exposed to tobacco smoke, and the tragedy is that many conditions are getting worse. We cannot sit still and allow this to happen.

FIRS proposes a multipronged campaign to combat lung disease to bring together all people concerned with lung health. It starts with naming September 25 World Lung Day and calling on respiratory health organizations to pledge to improve lung health and help identify ways to celebrate this day.

Please sign up, and share this call for action with your professional, advocacy, and social networks, and those of your friends and families. Please do your part as global citizens to improve lung health. To do so, organizations should indicate they wish to sign on and send their logo to Betty Sax, FIRS Secretariat, [email protected]. Organizations should also encourage individuals to sign on and show that they are committed to increasing awareness and action to promote global lung health.

Thank you.

Gerard Silvestri, MD, MS, FCCP

CHEST President

Darcy Marciniuk, MD, FCCP

CHEST FIRS Liaison

Dear CHEST Leaders, Members, and Friends:

The Forum of International Respiratory Societies (FIRS) is an organization comprised of the world’s leading international professional respiratory societies presenting a unifying voice to improve lung health globally. Its members are: the American College of Chest Physicians (CHEST), American Thoracic Society (ATS), Asian Pacific Society of Respirology (APSR), Asociación Latino Americana De Tórax (ALAT), European Respiratory Society (ERS), International Union Against Tuberculosis and Lung Diseases (The Union), the Pan African Thoracic Society (PATS), the Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD), and the Global Initiative for Asthma (GINA). FIRS has more than 70,000 professional members; the physicians and patients they serve magnify our efforts, allowing FIRS to speak for lung health on a global scale.

FIRS is working with the World Health Organization and the United Nations to make sure lung health is represented in national health agendas. FIRS’ position paper on electronic nicotine delivery systems was presented at a side-event at the United Nations High-Level Meeting (UNHL) in New York in 2014 and is now a world standard. At the recent World Health Assembly meeting (May 2017) in Geneva, FIRS launched its Global Impact of Lung Disease report that called for a global clean air standard, strong anti-tobacco laws, and better health care for patients with respiratory disease.

FIRS will be reviewing the new WHO Global Air Quality Guidelines and will help promote them globally through advocacy and messaging, as well as by providing air quality expertise. FIRS will be involved at the Coimbra meeting (Sept 26-29) on improving the urban environment, the Montevideo UN High-Level (UNHL) meeting on chronic disease (Oct 18-20), and the UN Ministerial Meeting in Moscow on tuberculosis, and it is preparing for the 2018 UNHL meetings on antibiotic drug resistance, tuberculosis, and chronic diseases.

At the World Health Assembly, FIRS proclaimed September 25 as World Lung Day and hopes to use this as a rallying point for advocacy related to respiratory health or air quality. Lung Disease is the only major chronic disease that does not have a World Day. FIRS produced a Charter for Lung Health (www.firsnet.org/publications/charter) and hopes to have 100,000 persons sign on to it. FIRS also seeks to have lung-health organizations sign on and develop activities that can be carried out to celebrate lung health. Uruguay was the first country to sign the charter. The logos of the organizations who have signed the charter are on the FIRS website at firsnet.org. Activities being planned include editorials, newsletters, and letters-to-the-editor articles, legislative proclamations, social media exposure, and free spirometry, smoking cessation guidance, and carbon monoxide testing, but FIRS is looking for many more ways to celebrate healthy lungs on September 25 and many more partners!

Sixty-five million people suffer from chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and 3 million die of it each year, making it the third leading cause of death worldwide; 10 million people develop tuberculosis and 1.4 million die of it each year, making it the most common deadly infectious disease; 1.6 million people die of lung cancer each year, making it the most deadly cancer; 334 million people suffer from asthma, making it the most common chronic disease of childhood; pneumonia kills millions of people each year, making it a leading cause of death in the very young and very old. At least 2 billion people are exposed to toxic indoor smoke; 1 billion inhale polluted outdoor air; and 1 billion are exposed to tobacco smoke, and the tragedy is that many conditions are getting worse. We cannot sit still and allow this to happen.

FIRS proposes a multipronged campaign to combat lung disease to bring together all people concerned with lung health. It starts with naming September 25 World Lung Day and calling on respiratory health organizations to pledge to improve lung health and help identify ways to celebrate this day.

Please sign up, and share this call for action with your professional, advocacy, and social networks, and those of your friends and families. Please do your part as global citizens to improve lung health. To do so, organizations should indicate they wish to sign on and send their logo to Betty Sax, FIRS Secretariat, [email protected]. Organizations should also encourage individuals to sign on and show that they are committed to increasing awareness and action to promote global lung health.

Thank you.

Gerard Silvestri, MD, MS, FCCP

CHEST President

Darcy Marciniuk, MD, FCCP

CHEST FIRS Liaison

Critical Care Commentary Conscience Rights, Medical Training, and Critical Care Editor’s Note:

When I invited Dr. Wes Ely – the coauthor of a recent article regarding physician-assisted suicide – to write a Critical Care Commentary on said topic, an interesting thing happened: he declined and suggested that I invite a group of students from medical schools across the country to write the piece instead. The idea was brilliant, and the resulting piece was so insightful that the CHEST® journal editorial leadership suggested submission to the journal, and the accepted article will appear in the September issue. Out of that effort, the idea for the present piece was born. The result is an opportunity to hear the students’ voices, not only to stimulate discussion on conscientious objection in medicine but also to remind the ICU community that our learners have their own opinions and that through dialogues such as this, we might all learn from one another.

Lee Morrow, MD, FCCP

“No provision in our Constitution ought to be dearer to man than that which protects the rights of conscience against the enterprises of the civil authority.” – Thomas Jefferson

(Washington HA. The Writings of Thomas Jefferson. New York: Biker, Thorne, & Co. 1854,; Vol 3:147.)

What is the proper role of conscience in medicine? A recent article in the New England Journal of Medicine (Stahl & Emmanuel. N Engl J Med. 2017; 376(14):1380) is the latest to address this question. It is often argued that physicians who cite conscience in refusing to perform requested procedures or treatments necessarily infringe upon patients’ rights. However, we feel that these concerns stem from a fundamental misunderstanding of what conscience is, why it ought to be respected as an indispensable part of medical judgment (Genuis & Lipp . Int J Family Med. 2013; Epub 2013 Dec 12), and how conscience is oriented toward the end goal of health, which we pursue in medicine.

By failing to define “conscience,” the crux of the argument against conscience rights is built on the basis of an implied diminution of conscience from an imperative moral judgment down to mere personal preference. If conscience represents only personal preference – if it is limited to a set of choices of the same moral equivalent as the selection of an ice cream flavor, with no need for technical expertise—then it would follow that a physician ought to simply comply with the patient’s decisions in any given medical situation. However, we know intuitively that this line of reasoning cannot hold, if followed to its conclusion. For example, if a patient presenting with symptoms of clear rhinorrhea and dry cough in December asks for an antibiotic, through this patient-sovereignty model, the physician surely ought to provide the prescription to honor the patient’s request. The patient would have every right to insist on the antibiotic, and the physician would be obliged to prescribe accordingly. We, as students, are trained, however, that it would be morally and professionally fitting, even obligatory, for the physician to refuse this request, precisely through exercise of his/her professional conscience.

If conscience, then, is not simply a subject of one’s personal preferences, how are we to properly understand it? Conscience is “a person’s moral sense of right and wrong, viewed as acting as a guide to one’s behavior” (Conscience. Oxford Dictionary. Oxford, Oxford University Press. 2017). It exhibits the commitment to engage in a “self-conscience activity, integrating reason, emotion, and will, in self-committed decisions about right and wrong, good and evil” (Sulmasy. Theor Med Bioeth. 2008; 29(3):135). Whether or not a person intentionally seeks to form his/her conscience, it continues to be molded through the regular actions of daily life. The actions we perform – and those we omit – constantly shape our individual consciences. One’s conscience can indeed err due to emotional imbalance or faulty reasoning, but, even in these instances, it is essential to invest in the proper shaping of conscience in accordance with truth and goodness, rather than to reject the place of conscience altogether.

By attributing appropriate value to an individual’s conscience, we thereby recognize the centrality of conscience to identity and personal integrity. Consequently, we see that forcing an individual to impinge on his/her conscience through coercive means incidentally violates that person’s autonomy and dignity as a human being capable of moral decision-making.

In the practice of medicine, the free exercise of conscience is especially relevant. When patients and physicians meet to act in the pursuit of the patient’s health, they begin the process of conscience-mediated shared decision-making, rife with the potential for disagreement. Throughout this process, a physician should not violate a patient’s conscience rights by forcing medical treatment where it is unwanted, but neither should a patient violate a physician’s conscience rights by demanding a procedure or treatment that the physician cannot perform in good conscience. Moreover, to insert an external arbiter (eg, a professional society) to resolve the situation by means of contradiction of conscience would have the same violating effect on one or both parties.

One common debate as to the application of conscience in the setting of critical care focuses on the issue of physician-assisted suicide and euthanasia (PAS/E) (Rhee J, et al. Chest. 2017;152[3]. Accepted for Sept 2017 publication). Those who would deny physicians the right to conscientiously object to PAS/E depict this as merely an issue of the physician’s personal preference. Given the distinction between preference and conscience, however, we recognize that much more is at play. For students and practitioners who hold that health signifies the “well-working of the organism as a whole,” (Kass L. Public Interest. 1975; 40(summer):11-42) and feel that the killing of a patient is an action that goes directly against the health of the patient, the obligation to participate in PAS/E represents not only a violation of our decision-making dignity, but also subverts the critical component of clinical judgment inherent to our profession. The conscientiously practicing doctor who follows what they believe to be their professional obligations, acting in accordance with the health of the patient, may reasonably conclude that PAS/E directly contradicts their obligations to pursue the best health interests of the patient. As such, their refusal to participate can hardly be deemed a simple personal preference, as the refusal is both reasoned and reasonable. Indeed, experts have concluded that regardless of the legality of PAS/E, physicians must be allowed to conscientiously object to participate (Goligher et al. Crit Care Med. 2017; 45(2):149).

As medical students who have recently gone through the arduous medical school application process, we are particularly concerned with the claim that if one sees fit to exercise conscientious objection as a practitioner, they should leave medicine, or choose a field in medicine with few ethical dilemmas. To crassly exclude students from the pursuit of medicine on the basis of the shape of their conscience would be to unjustly discriminate by assigning different values to genuinely held beliefs. A direct consequence of this exclusion would be to decrease the diversity of thought, which is central to medical innovation and medical progress. History has taught us that the frontiers of medical advancement are most ardently pursued by those who think deeply and then dare to act creatively, seeking to bring to fruition what others deemed impossible. Without conscience rights, physicians are not free to think for themselves. We find it hard to believe that many physicians would feel comfortable jettisoning conscience in all instances where it may go against the wishes of their patients or the consensus opinion of the profession.

Furthermore, as medical students, we are acutely aware of the importance of conscientious objection due to the extant hierarchical nature of medical training. Evaluations are often performed by residents and physicians in places of authority, so students will readily subjugate everything from bodily needs to conscience in order to appease their attending physicians. Evidence indicates that medical students will even fail to object when they recognize medical errors performed by their superiors (Madigosky WS, et al. Acad Med. 2006; 81(1):94).

It is, therefore, crucial to the proper formation of medical students that our exercise of conscience be safeguarded during our training. A student who is free to exercise conscience is a student who is learning to think independently, as well as to shoulder the responsibility that comes as a consequence of free choices.

Ultimately, we must ask ourselves: how is the role of the physician altered if we choose to minimize the role of conscience in medicine? And do patients truly want physicians who forfeit their consciences even in matters of life and death? If we take the demands of those who dismiss conscience to their end – that only those willing to put their conscience aside should enter medicine – we would be left with practitioners whose group think training would stifle discussion between physicians and patients, and whose role would be reduced to simply acquiescing to any and all demands of the patient, even to their own detriment. Such a group of people, in our view, would fail to be physicians.

Author Affiliations: Geisel School of Medicine at Dartmouth, Hanover, NH (Dr. Dumitru); University of North Carolina School of Medicine, Chapel Hill, NC (Mr. Frush); Ohio University Heritage College of Osteopathic Medicine, Athens, OH (Mr. Radlicz); Columbia University College of Physicians and Surgeons, New York, NY (Mr. Allen); Thomas Jefferson School of Medicine, Philadelphia, PA (Mr. Brown); Faculty of Medicine & Dentistry, University of Alberta School, Edmonton, AB, Canada (Mr. Bannon); Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, NY (Mr. Rhee).

When I invited Dr. Wes Ely – the coauthor of a recent article regarding physician-assisted suicide – to write a Critical Care Commentary on said topic, an interesting thing happened: he declined and suggested that I invite a group of students from medical schools across the country to write the piece instead. The idea was brilliant, and the resulting piece was so insightful that the CHEST® journal editorial leadership suggested submission to the journal, and the accepted article will appear in the September issue. Out of that effort, the idea for the present piece was born. The result is an opportunity to hear the students’ voices, not only to stimulate discussion on conscientious objection in medicine but also to remind the ICU community that our learners have their own opinions and that through dialogues such as this, we might all learn from one another.

Lee Morrow, MD, FCCP

“No provision in our Constitution ought to be dearer to man than that which protects the rights of conscience against the enterprises of the civil authority.” – Thomas Jefferson

(Washington HA. The Writings of Thomas Jefferson. New York: Biker, Thorne, & Co. 1854,; Vol 3:147.)

What is the proper role of conscience in medicine? A recent article in the New England Journal of Medicine (Stahl & Emmanuel. N Engl J Med. 2017; 376(14):1380) is the latest to address this question. It is often argued that physicians who cite conscience in refusing to perform requested procedures or treatments necessarily infringe upon patients’ rights. However, we feel that these concerns stem from a fundamental misunderstanding of what conscience is, why it ought to be respected as an indispensable part of medical judgment (Genuis & Lipp . Int J Family Med. 2013; Epub 2013 Dec 12), and how conscience is oriented toward the end goal of health, which we pursue in medicine.

By failing to define “conscience,” the crux of the argument against conscience rights is built on the basis of an implied diminution of conscience from an imperative moral judgment down to mere personal preference. If conscience represents only personal preference – if it is limited to a set of choices of the same moral equivalent as the selection of an ice cream flavor, with no need for technical expertise—then it would follow that a physician ought to simply comply with the patient’s decisions in any given medical situation. However, we know intuitively that this line of reasoning cannot hold, if followed to its conclusion. For example, if a patient presenting with symptoms of clear rhinorrhea and dry cough in December asks for an antibiotic, through this patient-sovereignty model, the physician surely ought to provide the prescription to honor the patient’s request. The patient would have every right to insist on the antibiotic, and the physician would be obliged to prescribe accordingly. We, as students, are trained, however, that it would be morally and professionally fitting, even obligatory, for the physician to refuse this request, precisely through exercise of his/her professional conscience.

If conscience, then, is not simply a subject of one’s personal preferences, how are we to properly understand it? Conscience is “a person’s moral sense of right and wrong, viewed as acting as a guide to one’s behavior” (Conscience. Oxford Dictionary. Oxford, Oxford University Press. 2017). It exhibits the commitment to engage in a “self-conscience activity, integrating reason, emotion, and will, in self-committed decisions about right and wrong, good and evil” (Sulmasy. Theor Med Bioeth. 2008; 29(3):135). Whether or not a person intentionally seeks to form his/her conscience, it continues to be molded through the regular actions of daily life. The actions we perform – and those we omit – constantly shape our individual consciences. One’s conscience can indeed err due to emotional imbalance or faulty reasoning, but, even in these instances, it is essential to invest in the proper shaping of conscience in accordance with truth and goodness, rather than to reject the place of conscience altogether.

By attributing appropriate value to an individual’s conscience, we thereby recognize the centrality of conscience to identity and personal integrity. Consequently, we see that forcing an individual to impinge on his/her conscience through coercive means incidentally violates that person’s autonomy and dignity as a human being capable of moral decision-making.

In the practice of medicine, the free exercise of conscience is especially relevant. When patients and physicians meet to act in the pursuit of the patient’s health, they begin the process of conscience-mediated shared decision-making, rife with the potential for disagreement. Throughout this process, a physician should not violate a patient’s conscience rights by forcing medical treatment where it is unwanted, but neither should a patient violate a physician’s conscience rights by demanding a procedure or treatment that the physician cannot perform in good conscience. Moreover, to insert an external arbiter (eg, a professional society) to resolve the situation by means of contradiction of conscience would have the same violating effect on one or both parties.

One common debate as to the application of conscience in the setting of critical care focuses on the issue of physician-assisted suicide and euthanasia (PAS/E) (Rhee J, et al. Chest. 2017;152[3]. Accepted for Sept 2017 publication). Those who would deny physicians the right to conscientiously object to PAS/E depict this as merely an issue of the physician’s personal preference. Given the distinction between preference and conscience, however, we recognize that much more is at play. For students and practitioners who hold that health signifies the “well-working of the organism as a whole,” (Kass L. Public Interest. 1975; 40(summer):11-42) and feel that the killing of a patient is an action that goes directly against the health of the patient, the obligation to participate in PAS/E represents not only a violation of our decision-making dignity, but also subverts the critical component of clinical judgment inherent to our profession. The conscientiously practicing doctor who follows what they believe to be their professional obligations, acting in accordance with the health of the patient, may reasonably conclude that PAS/E directly contradicts their obligations to pursue the best health interests of the patient. As such, their refusal to participate can hardly be deemed a simple personal preference, as the refusal is both reasoned and reasonable. Indeed, experts have concluded that regardless of the legality of PAS/E, physicians must be allowed to conscientiously object to participate (Goligher et al. Crit Care Med. 2017; 45(2):149).

As medical students who have recently gone through the arduous medical school application process, we are particularly concerned with the claim that if one sees fit to exercise conscientious objection as a practitioner, they should leave medicine, or choose a field in medicine with few ethical dilemmas. To crassly exclude students from the pursuit of medicine on the basis of the shape of their conscience would be to unjustly discriminate by assigning different values to genuinely held beliefs. A direct consequence of this exclusion would be to decrease the diversity of thought, which is central to medical innovation and medical progress. History has taught us that the frontiers of medical advancement are most ardently pursued by those who think deeply and then dare to act creatively, seeking to bring to fruition what others deemed impossible. Without conscience rights, physicians are not free to think for themselves. We find it hard to believe that many physicians would feel comfortable jettisoning conscience in all instances where it may go against the wishes of their patients or the consensus opinion of the profession.

Furthermore, as medical students, we are acutely aware of the importance of conscientious objection due to the extant hierarchical nature of medical training. Evaluations are often performed by residents and physicians in places of authority, so students will readily subjugate everything from bodily needs to conscience in order to appease their attending physicians. Evidence indicates that medical students will even fail to object when they recognize medical errors performed by their superiors (Madigosky WS, et al. Acad Med. 2006; 81(1):94).

It is, therefore, crucial to the proper formation of medical students that our exercise of conscience be safeguarded during our training. A student who is free to exercise conscience is a student who is learning to think independently, as well as to shoulder the responsibility that comes as a consequence of free choices.

Ultimately, we must ask ourselves: how is the role of the physician altered if we choose to minimize the role of conscience in medicine? And do patients truly want physicians who forfeit their consciences even in matters of life and death? If we take the demands of those who dismiss conscience to their end – that only those willing to put their conscience aside should enter medicine – we would be left with practitioners whose group think training would stifle discussion between physicians and patients, and whose role would be reduced to simply acquiescing to any and all demands of the patient, even to their own detriment. Such a group of people, in our view, would fail to be physicians.

Author Affiliations: Geisel School of Medicine at Dartmouth, Hanover, NH (Dr. Dumitru); University of North Carolina School of Medicine, Chapel Hill, NC (Mr. Frush); Ohio University Heritage College of Osteopathic Medicine, Athens, OH (Mr. Radlicz); Columbia University College of Physicians and Surgeons, New York, NY (Mr. Allen); Thomas Jefferson School of Medicine, Philadelphia, PA (Mr. Brown); Faculty of Medicine & Dentistry, University of Alberta School, Edmonton, AB, Canada (Mr. Bannon); Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, NY (Mr. Rhee).

When I invited Dr. Wes Ely – the coauthor of a recent article regarding physician-assisted suicide – to write a Critical Care Commentary on said topic, an interesting thing happened: he declined and suggested that I invite a group of students from medical schools across the country to write the piece instead. The idea was brilliant, and the resulting piece was so insightful that the CHEST® journal editorial leadership suggested submission to the journal, and the accepted article will appear in the September issue. Out of that effort, the idea for the present piece was born. The result is an opportunity to hear the students’ voices, not only to stimulate discussion on conscientious objection in medicine but also to remind the ICU community that our learners have their own opinions and that through dialogues such as this, we might all learn from one another.

Lee Morrow, MD, FCCP

“No provision in our Constitution ought to be dearer to man than that which protects the rights of conscience against the enterprises of the civil authority.” – Thomas Jefferson

(Washington HA. The Writings of Thomas Jefferson. New York: Biker, Thorne, & Co. 1854,; Vol 3:147.)

What is the proper role of conscience in medicine? A recent article in the New England Journal of Medicine (Stahl & Emmanuel. N Engl J Med. 2017; 376(14):1380) is the latest to address this question. It is often argued that physicians who cite conscience in refusing to perform requested procedures or treatments necessarily infringe upon patients’ rights. However, we feel that these concerns stem from a fundamental misunderstanding of what conscience is, why it ought to be respected as an indispensable part of medical judgment (Genuis & Lipp . Int J Family Med. 2013; Epub 2013 Dec 12), and how conscience is oriented toward the end goal of health, which we pursue in medicine.

By failing to define “conscience,” the crux of the argument against conscience rights is built on the basis of an implied diminution of conscience from an imperative moral judgment down to mere personal preference. If conscience represents only personal preference – if it is limited to a set of choices of the same moral equivalent as the selection of an ice cream flavor, with no need for technical expertise—then it would follow that a physician ought to simply comply with the patient’s decisions in any given medical situation. However, we know intuitively that this line of reasoning cannot hold, if followed to its conclusion. For example, if a patient presenting with symptoms of clear rhinorrhea and dry cough in December asks for an antibiotic, through this patient-sovereignty model, the physician surely ought to provide the prescription to honor the patient’s request. The patient would have every right to insist on the antibiotic, and the physician would be obliged to prescribe accordingly. We, as students, are trained, however, that it would be morally and professionally fitting, even obligatory, for the physician to refuse this request, precisely through exercise of his/her professional conscience.

If conscience, then, is not simply a subject of one’s personal preferences, how are we to properly understand it? Conscience is “a person’s moral sense of right and wrong, viewed as acting as a guide to one’s behavior” (Conscience. Oxford Dictionary. Oxford, Oxford University Press. 2017). It exhibits the commitment to engage in a “self-conscience activity, integrating reason, emotion, and will, in self-committed decisions about right and wrong, good and evil” (Sulmasy. Theor Med Bioeth. 2008; 29(3):135). Whether or not a person intentionally seeks to form his/her conscience, it continues to be molded through the regular actions of daily life. The actions we perform – and those we omit – constantly shape our individual consciences. One’s conscience can indeed err due to emotional imbalance or faulty reasoning, but, even in these instances, it is essential to invest in the proper shaping of conscience in accordance with truth and goodness, rather than to reject the place of conscience altogether.

By attributing appropriate value to an individual’s conscience, we thereby recognize the centrality of conscience to identity and personal integrity. Consequently, we see that forcing an individual to impinge on his/her conscience through coercive means incidentally violates that person’s autonomy and dignity as a human being capable of moral decision-making.

In the practice of medicine, the free exercise of conscience is especially relevant. When patients and physicians meet to act in the pursuit of the patient’s health, they begin the process of conscience-mediated shared decision-making, rife with the potential for disagreement. Throughout this process, a physician should not violate a patient’s conscience rights by forcing medical treatment where it is unwanted, but neither should a patient violate a physician’s conscience rights by demanding a procedure or treatment that the physician cannot perform in good conscience. Moreover, to insert an external arbiter (eg, a professional society) to resolve the situation by means of contradiction of conscience would have the same violating effect on one or both parties.

One common debate as to the application of conscience in the setting of critical care focuses on the issue of physician-assisted suicide and euthanasia (PAS/E) (Rhee J, et al. Chest. 2017;152[3]. Accepted for Sept 2017 publication). Those who would deny physicians the right to conscientiously object to PAS/E depict this as merely an issue of the physician’s personal preference. Given the distinction between preference and conscience, however, we recognize that much more is at play. For students and practitioners who hold that health signifies the “well-working of the organism as a whole,” (Kass L. Public Interest. 1975; 40(summer):11-42) and feel that the killing of a patient is an action that goes directly against the health of the patient, the obligation to participate in PAS/E represents not only a violation of our decision-making dignity, but also subverts the critical component of clinical judgment inherent to our profession. The conscientiously practicing doctor who follows what they believe to be their professional obligations, acting in accordance with the health of the patient, may reasonably conclude that PAS/E directly contradicts their obligations to pursue the best health interests of the patient. As such, their refusal to participate can hardly be deemed a simple personal preference, as the refusal is both reasoned and reasonable. Indeed, experts have concluded that regardless of the legality of PAS/E, physicians must be allowed to conscientiously object to participate (Goligher et al. Crit Care Med. 2017; 45(2):149).

As medical students who have recently gone through the arduous medical school application process, we are particularly concerned with the claim that if one sees fit to exercise conscientious objection as a practitioner, they should leave medicine, or choose a field in medicine with few ethical dilemmas. To crassly exclude students from the pursuit of medicine on the basis of the shape of their conscience would be to unjustly discriminate by assigning different values to genuinely held beliefs. A direct consequence of this exclusion would be to decrease the diversity of thought, which is central to medical innovation and medical progress. History has taught us that the frontiers of medical advancement are most ardently pursued by those who think deeply and then dare to act creatively, seeking to bring to fruition what others deemed impossible. Without conscience rights, physicians are not free to think for themselves. We find it hard to believe that many physicians would feel comfortable jettisoning conscience in all instances where it may go against the wishes of their patients or the consensus opinion of the profession.

Furthermore, as medical students, we are acutely aware of the importance of conscientious objection due to the extant hierarchical nature of medical training. Evaluations are often performed by residents and physicians in places of authority, so students will readily subjugate everything from bodily needs to conscience in order to appease their attending physicians. Evidence indicates that medical students will even fail to object when they recognize medical errors performed by their superiors (Madigosky WS, et al. Acad Med. 2006; 81(1):94).

It is, therefore, crucial to the proper formation of medical students that our exercise of conscience be safeguarded during our training. A student who is free to exercise conscience is a student who is learning to think independently, as well as to shoulder the responsibility that comes as a consequence of free choices.

Ultimately, we must ask ourselves: how is the role of the physician altered if we choose to minimize the role of conscience in medicine? And do patients truly want physicians who forfeit their consciences even in matters of life and death? If we take the demands of those who dismiss conscience to their end – that only those willing to put their conscience aside should enter medicine – we would be left with practitioners whose group think training would stifle discussion between physicians and patients, and whose role would be reduced to simply acquiescing to any and all demands of the patient, even to their own detriment. Such a group of people, in our view, would fail to be physicians.

Author Affiliations: Geisel School of Medicine at Dartmouth, Hanover, NH (Dr. Dumitru); University of North Carolina School of Medicine, Chapel Hill, NC (Mr. Frush); Ohio University Heritage College of Osteopathic Medicine, Athens, OH (Mr. Radlicz); Columbia University College of Physicians and Surgeons, New York, NY (Mr. Allen); Thomas Jefferson School of Medicine, Philadelphia, PA (Mr. Brown); Faculty of Medicine & Dentistry, University of Alberta School, Edmonton, AB, Canada (Mr. Bannon); Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, NY (Mr. Rhee).

Vaccination: An Important Step in Protecting Health

Patients with chronic lung conditions, like COPD and asthma, need to take extra steps to manage their condition and ensure the healthiest possible future. One important step that may not always be top of mind is vaccination, which can protect against common preventable diseases that may be very serious for those with respiratory conditions. CDC recommends adults with COPD, asthma, and other lung diseases get an annual flu vaccine, as well as stay up to date with pneumococcal and other recommended vaccines. Additional vaccines may be indicated based on age, job, travel locations, and lifestyle.

COPD and asthma cause airways to swell and become blocked with mucus, making it hard to breathe. Certain vaccine-preventable diseases can make this even worse. Adults with COPD and asthma are at increased risk of complications from influenza, including pneumonia and hospitalization. They are also at higher risk for invasive pneumococcal disease and more likely to develop infections including bacteremia and meningitis. Each year, thousands of adults needlessly suffer, are hospitalized, and even die of diseases that could be prevented by vaccines. Despite increased risks, less than half of adults under 65 years with COPD and asthma have received influenza and pneumococcal vaccination (National Health Information Survey 2015).

Find the latest recommended adult immunization schedule at www.cdc.gov/vaccines/hcp/adults.

Patients with chronic lung conditions, like COPD and asthma, need to take extra steps to manage their condition and ensure the healthiest possible future. One important step that may not always be top of mind is vaccination, which can protect against common preventable diseases that may be very serious for those with respiratory conditions. CDC recommends adults with COPD, asthma, and other lung diseases get an annual flu vaccine, as well as stay up to date with pneumococcal and other recommended vaccines. Additional vaccines may be indicated based on age, job, travel locations, and lifestyle.

COPD and asthma cause airways to swell and become blocked with mucus, making it hard to breathe. Certain vaccine-preventable diseases can make this even worse. Adults with COPD and asthma are at increased risk of complications from influenza, including pneumonia and hospitalization. They are also at higher risk for invasive pneumococcal disease and more likely to develop infections including bacteremia and meningitis. Each year, thousands of adults needlessly suffer, are hospitalized, and even die of diseases that could be prevented by vaccines. Despite increased risks, less than half of adults under 65 years with COPD and asthma have received influenza and pneumococcal vaccination (National Health Information Survey 2015).

Find the latest recommended adult immunization schedule at www.cdc.gov/vaccines/hcp/adults.