User login

Folic acid and multivitamin supplements associated with reduced autism risk

Taking folic acid and/or multivitamin supplements preceding and during pregnancy is associated with a lower risk of offspring developing autism spectrum disorder (ASD), an observational epidemiologic study published Jan. 3 showed.

The findings could have important public health implications, reported Stephen Z. Levine, PhD, and his associates.

The investigators found that 572 children, or 1.3%, received an ASD diagnosis. Dr. Levine and his associates found that children whose mothers took folic acid and multivitamin supplements during pregnancy had a lower risk of developing ASD (relative risk, 0.27; 95% confidence interval, 0.22-0.33; P less than .001), compared with those whose mothers took no supplements. Similarly, there was reduced risk among those whose mothers took only folic acid during pregnancy (RR, 0.32; CI, 0.26-0.41; P less than .001) or only multivitamins (RR, 0.35; CI, 0.28-0.44; P less than .001). Likewise, lower risks were seen among offspring whose mothers took supplements before pregnancy: Compared with no supplements, the RR was 0.39 for folic acid and/or multivitamins (CI, 0.30-0.50; P less than .001), 0.56 for just folic acid (95%CI, 0.42-0.74; P = .001), and 0.36 for just multivitamins (95%CI, 0.24-0.52; P less than .001). Similar associations were found among male and female offspring.

“This finding may reflect noncompliance, higher rates of vitamin deficiency, or poor diet among persons with psychiatric conditions,” wrote Dr. Levine, of the department of community mental health at the University of Haifa, Israel, and his associates in JAMA Psychiatry.

Another important finding is that maternal exposure to folic acid and multivitamin supplements 2 years before pregnancy is tied to a lower ASD risk.

The investigators acknowledged that the study was limited by their inability to determine possible confounding factors, such as the vehicle of vitamin dispensations, use of over-the-counter supplements, false-positive classifications from noncompliance, and absence of information on gestational age. In addition, they said, “causality cannot be inferred from observational studies such as this one.” In light of those limitations, investigators said, additional studies replicating these findings are needed.

The study was funded by several entities, including the National Institutes of Health, the Fredrik and Ingrid Thuring Foundation, and the Swedish Society of Medicine. Dr. Levine reported receiving support from Shire Pharmaceuticals, and coauthor Arad Kodesh, MD, is an employee of Meuhedet Health Services. No other relevant financial disclosures were reported.

SOURCE: Levine SZ et al. JAMA Psychiatry. 2018 Jan 3. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2017.4050.

Taking folic acid and/or multivitamin supplements preceding and during pregnancy is associated with a lower risk of offspring developing autism spectrum disorder (ASD), an observational epidemiologic study published Jan. 3 showed.

The findings could have important public health implications, reported Stephen Z. Levine, PhD, and his associates.

The investigators found that 572 children, or 1.3%, received an ASD diagnosis. Dr. Levine and his associates found that children whose mothers took folic acid and multivitamin supplements during pregnancy had a lower risk of developing ASD (relative risk, 0.27; 95% confidence interval, 0.22-0.33; P less than .001), compared with those whose mothers took no supplements. Similarly, there was reduced risk among those whose mothers took only folic acid during pregnancy (RR, 0.32; CI, 0.26-0.41; P less than .001) or only multivitamins (RR, 0.35; CI, 0.28-0.44; P less than .001). Likewise, lower risks were seen among offspring whose mothers took supplements before pregnancy: Compared with no supplements, the RR was 0.39 for folic acid and/or multivitamins (CI, 0.30-0.50; P less than .001), 0.56 for just folic acid (95%CI, 0.42-0.74; P = .001), and 0.36 for just multivitamins (95%CI, 0.24-0.52; P less than .001). Similar associations were found among male and female offspring.

“This finding may reflect noncompliance, higher rates of vitamin deficiency, or poor diet among persons with psychiatric conditions,” wrote Dr. Levine, of the department of community mental health at the University of Haifa, Israel, and his associates in JAMA Psychiatry.

Another important finding is that maternal exposure to folic acid and multivitamin supplements 2 years before pregnancy is tied to a lower ASD risk.

The investigators acknowledged that the study was limited by their inability to determine possible confounding factors, such as the vehicle of vitamin dispensations, use of over-the-counter supplements, false-positive classifications from noncompliance, and absence of information on gestational age. In addition, they said, “causality cannot be inferred from observational studies such as this one.” In light of those limitations, investigators said, additional studies replicating these findings are needed.

The study was funded by several entities, including the National Institutes of Health, the Fredrik and Ingrid Thuring Foundation, and the Swedish Society of Medicine. Dr. Levine reported receiving support from Shire Pharmaceuticals, and coauthor Arad Kodesh, MD, is an employee of Meuhedet Health Services. No other relevant financial disclosures were reported.

SOURCE: Levine SZ et al. JAMA Psychiatry. 2018 Jan 3. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2017.4050.

Taking folic acid and/or multivitamin supplements preceding and during pregnancy is associated with a lower risk of offspring developing autism spectrum disorder (ASD), an observational epidemiologic study published Jan. 3 showed.

The findings could have important public health implications, reported Stephen Z. Levine, PhD, and his associates.

The investigators found that 572 children, or 1.3%, received an ASD diagnosis. Dr. Levine and his associates found that children whose mothers took folic acid and multivitamin supplements during pregnancy had a lower risk of developing ASD (relative risk, 0.27; 95% confidence interval, 0.22-0.33; P less than .001), compared with those whose mothers took no supplements. Similarly, there was reduced risk among those whose mothers took only folic acid during pregnancy (RR, 0.32; CI, 0.26-0.41; P less than .001) or only multivitamins (RR, 0.35; CI, 0.28-0.44; P less than .001). Likewise, lower risks were seen among offspring whose mothers took supplements before pregnancy: Compared with no supplements, the RR was 0.39 for folic acid and/or multivitamins (CI, 0.30-0.50; P less than .001), 0.56 for just folic acid (95%CI, 0.42-0.74; P = .001), and 0.36 for just multivitamins (95%CI, 0.24-0.52; P less than .001). Similar associations were found among male and female offspring.

“This finding may reflect noncompliance, higher rates of vitamin deficiency, or poor diet among persons with psychiatric conditions,” wrote Dr. Levine, of the department of community mental health at the University of Haifa, Israel, and his associates in JAMA Psychiatry.

Another important finding is that maternal exposure to folic acid and multivitamin supplements 2 years before pregnancy is tied to a lower ASD risk.

The investigators acknowledged that the study was limited by their inability to determine possible confounding factors, such as the vehicle of vitamin dispensations, use of over-the-counter supplements, false-positive classifications from noncompliance, and absence of information on gestational age. In addition, they said, “causality cannot be inferred from observational studies such as this one.” In light of those limitations, investigators said, additional studies replicating these findings are needed.

The study was funded by several entities, including the National Institutes of Health, the Fredrik and Ingrid Thuring Foundation, and the Swedish Society of Medicine. Dr. Levine reported receiving support from Shire Pharmaceuticals, and coauthor Arad Kodesh, MD, is an employee of Meuhedet Health Services. No other relevant financial disclosures were reported.

SOURCE: Levine SZ et al. JAMA Psychiatry. 2018 Jan 3. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2017.4050.

Key clinical point: Taking folic acid and multivitamin supplements before and during pregnancy can reduce risk of autism in children.

Major finding: Children whose mothers took folic acid and/or multivitamin supplements during pregnancy had a decreased risk of developing ASD, compared with those whose mothers did not (relative risk, 0.27; 95% confidence interval, 0.22-0.33; P less than .001).

Study details: Observational epidemiologic study of 45,300 Israeli children born between January 2003 and December 2007 and followed until January 2015.

Disclosures: The study was funded by several entities, including the National Institutes of Health, the Fredrik and Ingrid Thuring Foundation, and the Swedish Society of Medicine. Dr. Levine reported receiving support from Shire Pharmaceuticals, and coauthor Arad Kodesh, MD, is an employee of Meuhedet Health Services. No other relevant financial disclosures were reported.

Source: Levine SZ et al. JAMA Psychiatry. 2018 Jan 3. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2017.4050.

2018 Update on obstetrics

The past year brought new information and guidance from the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) on many relevant obstetric topics, making it difficult to choose just a few for this Update. Opioid use in pregnancy was an obvious choice given the national media attention and the potential opportunity for intervention in pregnancy for both the mother and the fetus/newborn. Postpartum hemorrhage, an “oldie but goodie,” was chosen for several reasons: It got a new definition, a new focus on multidisciplinary care, and an exciting novel tool for the treatment toolbox. Finally, given the rapidly changing technology, new screening recommendations, and the complexity of counseling, carrier screening was chosen as a genetic hot topic for this year.

Opioids, obstetrics, and opportunities

Reddy UM, Davis JM, Ren Z, Greene MF; Opioid Use in Pregnancy, Neonatal Abstinence Syndrome, and Childhood Outcomes Workshop Invited Speakers. Opioid use in pregnancy, neonatal abstinence syndrome, and childhood outcomes: Executive summary of a joint workshop. Obstet Gynecol. 2017;130(1):10-28.

ACOG Committee on Obstetric Practice. ACOG committee opinion No. 711: Opioid use and opioid use disorder in pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2017;130(2):e81-e94.

The term "opioid epidemic" is omnipresent in both the lay media and the medical literature. In the past decade, the United States has had a huge increase in the number of opioid prescriptions, the rate of admissions and deaths due to prescription opioid misuse and abuse, and an increased rate of heroin use attributed to prior prescription opioid use.

Obstetrics is unique in that opioid use and abuse disorders affect 2 patients simultaneously (the mother and fetus), and the treatment options are somewhat at odds in that they need to balance a stable maternal status and intrauterine environment with the risk of neonatal abstinence syndrome (NAS). Additionally, pregnancy is an opportunity for a woman with opioid use disorder to have access to medical care (possibly for the first time) leading to the diagnosis and treatment of her disease. As the clinicians on the front line, obstetricians therefore require education and guidance on best practice for management of opioid use in pregnancy.

In 2017, Reddy and colleagues, as part of a joint workshop on opioid use in pregnancy, and a committee opinion from ACOG provided the following recommendations.

Screening

Universally screen for substance use, starting at the first prenatal visit; this is recommended over risk factor-based screening.

Use a validated screening tool. A tool such as a questionnaire is recommended as the first-line screening test (for example, the 4Ps screen, the National Institute on Drug Abuse Quick Screen, and the CRAFFT Screening Interview).

Do not universally screen urine and hair for drugs. This type of screening has many limitations, such as the limited number of substances tested, false-positive results, and inaccurate determination of the frequency or timing of drug use. Information regarding the consequences of the test must be provided, and patient consent must be obtained prior to performing the test.

Treatment

Use medication-assisted treatment with buprenorphine or methadone, which is preferred to medically supervised withdrawal. Medication-assisted treatment prevents withdrawal symptoms and cravings, decreases the risk of relapse, improves compliance with prenatal care and addiction treatment programs, and leads to better obstetric outcomes (higher birth weight, lower rate of preterm birth, lower perinatal mortality).

Know that buprenorphine has several advantages over methadone, including the convenience of an outpatient prescription, a lower risk of overdose, and improved neonatal outcomes (higher birth weight, lower doses of morphine to treat NAS, shorter treatment duration).

Prioritize methadone as the preferred option for pregnant women who are already receiving methadone treatment (changing to buprenorphine may precipitate withdrawal), those with a long-standing history of or multi-substance abuse, and those who have failed other treatment programs.

Prenatal care

Screen for comorbid conditions such as sexually transmitted infections, other medications or substance use, social conditions, and mental health disorders.

Perform ultrasonography serially to monitor fetal growth because of the increased risk of fetal growth restriction.

Consult with anesthesiology for pain control recommendations for labor and delivery and with neonatalogy/pediatrics for NAS counseling.

Intrapartum/postpartum care

Recognize heightened pain. Women with opioid use disorder have increased sensitivity to painful stimuli.

Continue the maintenance dose of methadone or buprenorphine throughout hospitalization, with short-acting opioids added for a brief period for postoperative pain.

Prioritize regional anesthesia for pain control in labor or for cesarean delivery.

Consider alternative therapies such as regional blocks, nonopioid medications (nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, acetaminophen), or relaxation/mindfulness training.

Avoid mixed antagonist and agonist narcotics (butorphanol, nalbuphine, pentazocine) as they may cause acute withdrawal.

Encourage breastfeeding to decrease the severity of NAS and maternal stress and increase maternal-child bonding and maternal confidence.

Offer contraceptive counseling and services immediately postpartum in the hospital, with strong consideration for long-acting reversible contraception.

Opioid prescribing practices

Opioids are prescribed in excess post–cesarean delivery. Several recent studies have demonstrated that most women are prescribed opioids post–cesarean delivery in excess of the amount they use (median 30–40 tablets prescribed, median 20 tablets used).1,2 The leftover opioid medication usually is not discarded and therefore is at risk for diversion or misuse. A small subset of patients will use all the opioids prescribed and feel as though they have not received enough medication.

Prescribe post–cesarean delivery opioids more appropriately by considering individual inpatient opioid requirements or a shared decision-making model.3

Prioritize acetaminophen and ibuprofen during breastfeeding. In a recent editorial in OBG Management, Robert L. Barbieri, MD, recommended that whenever possible, acetaminophen and ibuprofen should be the first-line treatment for breastfeeding women, and narcotics that are metabolized by CYP2D6 should be avoided to reduce the risk to the newborn.4

Universal screening for substance use should be performed in all pregnant women, and clinicians should offer medication-assisted treatment in conjunction with prenatal care and other supportive services as the standard therapy for opioid use disorder. More selective, patient-specific opioid prescribing practices should be applied in the obstetric population.

Read about new strategies for postpartum hemorrhage.

Postpartum hemorrhage: New definitions and new strategies for stemming the flow

ACOG Committee on Practice Bulletins—Obstetrics. ACOG practice bulletin No. 183: Postpartum hemorrhage. Obstet Gynecol. 2017;130(4):e168-e186.

From the very first sentence of the new ACOG practice bulletin, postpartum hemorrhage (PPH) is redefined as "cumulative blood loss greater than or equal to 1,000 mL or blood loss accompanied by signs or symptoms of hypovolemia within 24 hours after the birth process (includes intrapartum loss) regardless of route of delivery." Although this does not seem to be a huge change from the traditional teaching of a 500-mL blood loss at vaginal delivery and a 1,000-mL loss at cesarean delivery, it reflects a shift in focus from simply responding to a certain amount of bleeding to using a multidisciplinary action plan for treating this leading cause of maternal mortality worldwide.

Focus on developing a PPH action plan

As part of the shift toward a multidisciplinary action plan for PPH, all obstetric team members should be aware of the following:

- For most postpartum women, by the time they begin to show signs of hemodynamic compromise, the amount of blood loss approaches 25% of their total blood volume (1,500 mL). Lactic acidosis, systemic inflammation, and a consumptive coagulopathy result.

- Risk stratification prior to delivery, recognition and identification of the source of bleeding, and aggressive early resuscitation to prevent hypovolemia are paramount. Experience gleaned from trauma massive transfusion protocols suggests that judicious transfusion of packed red blood cells, fresh frozen plasma, and platelets in a 1:1:1 ratio is appropriate for obstetric patients. Additionally, patients with low fibrinogen levels should be treated with cryoprecipitate.

- The use of fixed transfusion ratios and standardized protocols for recognition and management of PPH has been demonstrated to increase earlier intervention and resolution of hemorrhage at an earlier stage, although the maternal outcomes results have been mixed.

- Multidisciplinary team drills and simulation exercises also should be considered to help solidify training of an institution's teams responsible for PPH response.

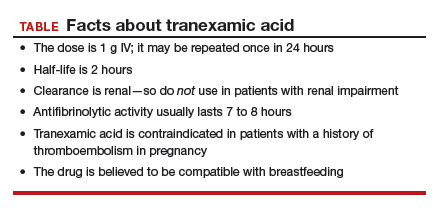

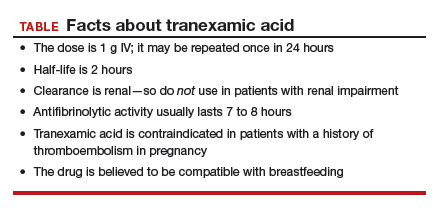

Novel management option: Tranexamic acid

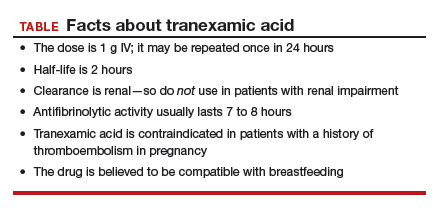

In addition to these strategies, there is a new recommendation for managing refractory PPH: tranexamic acid, which works by binding to lysine receptors on plasminogen and plasmin, inhibiting plasmin-mediated fibrin degradation.5 Previously, tranexamic acid was known to be effective in trauma, heart surgery, and in patients with thrombophilias. Pacheco and colleagues recently demonstrated reduced mortality from obstetric bleeding if tranexamic acid was given within 3 hours of delivery, without increased thrombotic complications.5 ACOG recommends its use if initial medical therapy fails, while the World Health Organization strongly recommends that tranexamic acid be part of a standard PPH package for all cases of PPH (TABLE).6

Postpartum hemorrhage requires early, aggressive, and multidisciplinary coordination to ensure that 1) patients at risk for hemorrhage are identified for preventive measures; 2) existing hemorrhage is recognized and quickly treated, first with noninvasive methods and then with more definitive surgical treatments; and 3) blood product replacement follows an evidence-based standardized protocol. Tranexamic acid is recommended as an adjunct treatment for PPH (of any cause) and should be used within 3 hours of delivery.

Read about new ACOG guidance on prepregnancy and prenatal screening.

Carrier screening—choose something

ACOG Committee on Genetics. Committee opinion No. 690: Carrier screening in the age of genomic medicine. Obstet Gynecol. 2017;129(3):e35-e40.

ACOG Committee on Genetics. Committee opinion No. 691: Carrier screening for genetic conditions. Obstet Gynecol. 2017;129(3):e41-e55.

Ideally, carrier screening should be offered prior to pregnancy to fully inform couples of their reproductive risks and options for pregnancy. If not performed in the preconception period, carrier screening should be offered to all pregnant women. If a patient chooses screening and screens positive for a particular disorder, her reproductive partner should then be offered screening so that the risk of having an affected child can be determined.

New ACOG guidance on prepregnancy and prenatal screening

Carrier screening recommendations have evolved as the technology available has expanded. All 3 of the following strategies now are considered "acceptable" according to 2 recently published ACOG committee opinions.

Traditional ethnic-specific carrier screening, previously ACOG's sole recommendation, involves offering specific genetic screening to patients from populations with a high prevalence for certain conditions. One such example is Tay-Sachs disease screening in Ashkenazi Jewish patients.

Panethnic screening, which takes into account mixed or uncertain backgrounds, involves screening for a certain panel of disorders and is available to all patients regardless of their background (for example, cystic fibrosis screening offered to all pregnant patients).

Expanded carrier screening is when a large number of disorders can be screened for simultaneously for a lower cost than previous testing strategies. Expanded carrier screening panels vary in number and which conditions are tested by the laboratory. An ideal expanded carrier screening panel has been debated in the literature but not agreed on.7

ObGyns and practices therefore are encouraged to develop a standard counseling and screening protocol to offer to all their patients while being flexible to make available any patient-requested screening that is outside their protocol. Pretest and posttest counseling, including a thorough family history, is essential (as with any genetic testing) and should include residual risk after testing, potential need for specific familial mutation testing instead of general carrier screening, and issues with consanguinity.

Three essential screens

Regardless of the screening strategy chosen from the above options, 3 screening tests should be offered to all pregnant women or couples considering pregnancy (either individually or in the context of an expanded screening panel):

- Cystic fibrosis. At the least, a panel of the 23 most common mutations should be used. More expanded panels, which include hundreds of mutations, increase detection in non-Caucasian populations and for milder forms of the disease or infertility-related mutations.

- Hemoglobinopathies (sickle cell, α- and β-thalassemia). Complete blood count and red blood indices are recommended for all, with hemoglobin electrophoresis recommended for patients of African, Middle Eastern, Mediterranean, or West Indian descent or if mean corpuscular volume is low.

- Spinal muscular atrophy (SMA). The most recent addition to ACOG's recommendations for general carrier screening due to the relatively high carrier frequency (1-in-40 to 1-in-60) and the severity of the disease, SMA causes degeneration of the spinal cord neurons, skeletal muscular atrophy, and overall weakness. Screening is via polymerase chain reaction for SMN1 copy number: 2 copies are normal, and 1 copy indicates a carrier of the SMN1 deletion. About 3% to 4% of patients will screen negative but still will be "carriers" due to having 2 copies of the SMN1 gene on 1 chromosome and no copies on the other chromosome.

All pregnant patients or patients considering pregnancy should be offered carrier screening as standard reproductive care, including screening for cystic fibrosis, hemoglobinopathies, and spinal muscular atrophy. Ethnic, panethnic, or expanded carrier screening (and patient-requested specific screening) all are acceptable options, and a standard screening and counseling protocol should be determined by the ObGyn or practice.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

- Bateman BT, Cole NM, Maeda A, et al. Patterns of opioid prescription and use after cesarean delivery. Obstet Gynecol. 2017;130(1):29–35.

- Osmundson SS, Schornack LA, Grasch JL, Zuckerwise LC, Young JL, Richardson MD. Postdischarge opioid use after cesarean delivery. Obstet Gynecol. 2017;130(1):36–41.

- Prabhu M, McQuaid-Hanson E, Hopp S, et al. A shared decision-making intervention to guide opioid prescribing after cesarean delivery. Obstet Gynecol. 2017;130(1):42–46.

- Barbieri RL. Stop using codeine, oxycodone, hydrocodone, tramadol, and aspirin in women who are breastfeeding. OBG Manag. 2017;29(10):8–12.

- Pacheco LD, Hankins GD, Saad AF, Costantine MM, Chiossi G, Saade GR. Tranexamic acid for the management of obstetric hemorrhage. Obstet Gynecol. 2017;130(4);765–769.

- WHO recommendation on tranexamic acid for the treatment of postpartum haemorrhage. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2017.

- Stevens B, Krstic N, Jones M, Murphy L, Hoskovec J. Finding middle ground in constructing a clinically useful expanded carrier screening panel. Obstet Gynecol. 2017;130(2):279–284.

The past year brought new information and guidance from the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) on many relevant obstetric topics, making it difficult to choose just a few for this Update. Opioid use in pregnancy was an obvious choice given the national media attention and the potential opportunity for intervention in pregnancy for both the mother and the fetus/newborn. Postpartum hemorrhage, an “oldie but goodie,” was chosen for several reasons: It got a new definition, a new focus on multidisciplinary care, and an exciting novel tool for the treatment toolbox. Finally, given the rapidly changing technology, new screening recommendations, and the complexity of counseling, carrier screening was chosen as a genetic hot topic for this year.

Opioids, obstetrics, and opportunities

Reddy UM, Davis JM, Ren Z, Greene MF; Opioid Use in Pregnancy, Neonatal Abstinence Syndrome, and Childhood Outcomes Workshop Invited Speakers. Opioid use in pregnancy, neonatal abstinence syndrome, and childhood outcomes: Executive summary of a joint workshop. Obstet Gynecol. 2017;130(1):10-28.

ACOG Committee on Obstetric Practice. ACOG committee opinion No. 711: Opioid use and opioid use disorder in pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2017;130(2):e81-e94.

The term "opioid epidemic" is omnipresent in both the lay media and the medical literature. In the past decade, the United States has had a huge increase in the number of opioid prescriptions, the rate of admissions and deaths due to prescription opioid misuse and abuse, and an increased rate of heroin use attributed to prior prescription opioid use.

Obstetrics is unique in that opioid use and abuse disorders affect 2 patients simultaneously (the mother and fetus), and the treatment options are somewhat at odds in that they need to balance a stable maternal status and intrauterine environment with the risk of neonatal abstinence syndrome (NAS). Additionally, pregnancy is an opportunity for a woman with opioid use disorder to have access to medical care (possibly for the first time) leading to the diagnosis and treatment of her disease. As the clinicians on the front line, obstetricians therefore require education and guidance on best practice for management of opioid use in pregnancy.

In 2017, Reddy and colleagues, as part of a joint workshop on opioid use in pregnancy, and a committee opinion from ACOG provided the following recommendations.

Screening

Universally screen for substance use, starting at the first prenatal visit; this is recommended over risk factor-based screening.

Use a validated screening tool. A tool such as a questionnaire is recommended as the first-line screening test (for example, the 4Ps screen, the National Institute on Drug Abuse Quick Screen, and the CRAFFT Screening Interview).

Do not universally screen urine and hair for drugs. This type of screening has many limitations, such as the limited number of substances tested, false-positive results, and inaccurate determination of the frequency or timing of drug use. Information regarding the consequences of the test must be provided, and patient consent must be obtained prior to performing the test.

Treatment

Use medication-assisted treatment with buprenorphine or methadone, which is preferred to medically supervised withdrawal. Medication-assisted treatment prevents withdrawal symptoms and cravings, decreases the risk of relapse, improves compliance with prenatal care and addiction treatment programs, and leads to better obstetric outcomes (higher birth weight, lower rate of preterm birth, lower perinatal mortality).

Know that buprenorphine has several advantages over methadone, including the convenience of an outpatient prescription, a lower risk of overdose, and improved neonatal outcomes (higher birth weight, lower doses of morphine to treat NAS, shorter treatment duration).

Prioritize methadone as the preferred option for pregnant women who are already receiving methadone treatment (changing to buprenorphine may precipitate withdrawal), those with a long-standing history of or multi-substance abuse, and those who have failed other treatment programs.

Prenatal care

Screen for comorbid conditions such as sexually transmitted infections, other medications or substance use, social conditions, and mental health disorders.

Perform ultrasonography serially to monitor fetal growth because of the increased risk of fetal growth restriction.

Consult with anesthesiology for pain control recommendations for labor and delivery and with neonatalogy/pediatrics for NAS counseling.

Intrapartum/postpartum care

Recognize heightened pain. Women with opioid use disorder have increased sensitivity to painful stimuli.

Continue the maintenance dose of methadone or buprenorphine throughout hospitalization, with short-acting opioids added for a brief period for postoperative pain.

Prioritize regional anesthesia for pain control in labor or for cesarean delivery.

Consider alternative therapies such as regional blocks, nonopioid medications (nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, acetaminophen), or relaxation/mindfulness training.

Avoid mixed antagonist and agonist narcotics (butorphanol, nalbuphine, pentazocine) as they may cause acute withdrawal.

Encourage breastfeeding to decrease the severity of NAS and maternal stress and increase maternal-child bonding and maternal confidence.

Offer contraceptive counseling and services immediately postpartum in the hospital, with strong consideration for long-acting reversible contraception.

Opioid prescribing practices

Opioids are prescribed in excess post–cesarean delivery. Several recent studies have demonstrated that most women are prescribed opioids post–cesarean delivery in excess of the amount they use (median 30–40 tablets prescribed, median 20 tablets used).1,2 The leftover opioid medication usually is not discarded and therefore is at risk for diversion or misuse. A small subset of patients will use all the opioids prescribed and feel as though they have not received enough medication.

Prescribe post–cesarean delivery opioids more appropriately by considering individual inpatient opioid requirements or a shared decision-making model.3

Prioritize acetaminophen and ibuprofen during breastfeeding. In a recent editorial in OBG Management, Robert L. Barbieri, MD, recommended that whenever possible, acetaminophen and ibuprofen should be the first-line treatment for breastfeeding women, and narcotics that are metabolized by CYP2D6 should be avoided to reduce the risk to the newborn.4

Universal screening for substance use should be performed in all pregnant women, and clinicians should offer medication-assisted treatment in conjunction with prenatal care and other supportive services as the standard therapy for opioid use disorder. More selective, patient-specific opioid prescribing practices should be applied in the obstetric population.

Read about new strategies for postpartum hemorrhage.

Postpartum hemorrhage: New definitions and new strategies for stemming the flow

ACOG Committee on Practice Bulletins—Obstetrics. ACOG practice bulletin No. 183: Postpartum hemorrhage. Obstet Gynecol. 2017;130(4):e168-e186.

From the very first sentence of the new ACOG practice bulletin, postpartum hemorrhage (PPH) is redefined as "cumulative blood loss greater than or equal to 1,000 mL or blood loss accompanied by signs or symptoms of hypovolemia within 24 hours after the birth process (includes intrapartum loss) regardless of route of delivery." Although this does not seem to be a huge change from the traditional teaching of a 500-mL blood loss at vaginal delivery and a 1,000-mL loss at cesarean delivery, it reflects a shift in focus from simply responding to a certain amount of bleeding to using a multidisciplinary action plan for treating this leading cause of maternal mortality worldwide.

Focus on developing a PPH action plan

As part of the shift toward a multidisciplinary action plan for PPH, all obstetric team members should be aware of the following:

- For most postpartum women, by the time they begin to show signs of hemodynamic compromise, the amount of blood loss approaches 25% of their total blood volume (1,500 mL). Lactic acidosis, systemic inflammation, and a consumptive coagulopathy result.

- Risk stratification prior to delivery, recognition and identification of the source of bleeding, and aggressive early resuscitation to prevent hypovolemia are paramount. Experience gleaned from trauma massive transfusion protocols suggests that judicious transfusion of packed red blood cells, fresh frozen plasma, and platelets in a 1:1:1 ratio is appropriate for obstetric patients. Additionally, patients with low fibrinogen levels should be treated with cryoprecipitate.

- The use of fixed transfusion ratios and standardized protocols for recognition and management of PPH has been demonstrated to increase earlier intervention and resolution of hemorrhage at an earlier stage, although the maternal outcomes results have been mixed.

- Multidisciplinary team drills and simulation exercises also should be considered to help solidify training of an institution's teams responsible for PPH response.

Novel management option: Tranexamic acid

In addition to these strategies, there is a new recommendation for managing refractory PPH: tranexamic acid, which works by binding to lysine receptors on plasminogen and plasmin, inhibiting plasmin-mediated fibrin degradation.5 Previously, tranexamic acid was known to be effective in trauma, heart surgery, and in patients with thrombophilias. Pacheco and colleagues recently demonstrated reduced mortality from obstetric bleeding if tranexamic acid was given within 3 hours of delivery, without increased thrombotic complications.5 ACOG recommends its use if initial medical therapy fails, while the World Health Organization strongly recommends that tranexamic acid be part of a standard PPH package for all cases of PPH (TABLE).6

Postpartum hemorrhage requires early, aggressive, and multidisciplinary coordination to ensure that 1) patients at risk for hemorrhage are identified for preventive measures; 2) existing hemorrhage is recognized and quickly treated, first with noninvasive methods and then with more definitive surgical treatments; and 3) blood product replacement follows an evidence-based standardized protocol. Tranexamic acid is recommended as an adjunct treatment for PPH (of any cause) and should be used within 3 hours of delivery.

Read about new ACOG guidance on prepregnancy and prenatal screening.

Carrier screening—choose something

ACOG Committee on Genetics. Committee opinion No. 690: Carrier screening in the age of genomic medicine. Obstet Gynecol. 2017;129(3):e35-e40.

ACOG Committee on Genetics. Committee opinion No. 691: Carrier screening for genetic conditions. Obstet Gynecol. 2017;129(3):e41-e55.

Ideally, carrier screening should be offered prior to pregnancy to fully inform couples of their reproductive risks and options for pregnancy. If not performed in the preconception period, carrier screening should be offered to all pregnant women. If a patient chooses screening and screens positive for a particular disorder, her reproductive partner should then be offered screening so that the risk of having an affected child can be determined.

New ACOG guidance on prepregnancy and prenatal screening

Carrier screening recommendations have evolved as the technology available has expanded. All 3 of the following strategies now are considered "acceptable" according to 2 recently published ACOG committee opinions.

Traditional ethnic-specific carrier screening, previously ACOG's sole recommendation, involves offering specific genetic screening to patients from populations with a high prevalence for certain conditions. One such example is Tay-Sachs disease screening in Ashkenazi Jewish patients.

Panethnic screening, which takes into account mixed or uncertain backgrounds, involves screening for a certain panel of disorders and is available to all patients regardless of their background (for example, cystic fibrosis screening offered to all pregnant patients).

Expanded carrier screening is when a large number of disorders can be screened for simultaneously for a lower cost than previous testing strategies. Expanded carrier screening panels vary in number and which conditions are tested by the laboratory. An ideal expanded carrier screening panel has been debated in the literature but not agreed on.7

ObGyns and practices therefore are encouraged to develop a standard counseling and screening protocol to offer to all their patients while being flexible to make available any patient-requested screening that is outside their protocol. Pretest and posttest counseling, including a thorough family history, is essential (as with any genetic testing) and should include residual risk after testing, potential need for specific familial mutation testing instead of general carrier screening, and issues with consanguinity.

Three essential screens

Regardless of the screening strategy chosen from the above options, 3 screening tests should be offered to all pregnant women or couples considering pregnancy (either individually or in the context of an expanded screening panel):

- Cystic fibrosis. At the least, a panel of the 23 most common mutations should be used. More expanded panels, which include hundreds of mutations, increase detection in non-Caucasian populations and for milder forms of the disease or infertility-related mutations.

- Hemoglobinopathies (sickle cell, α- and β-thalassemia). Complete blood count and red blood indices are recommended for all, with hemoglobin electrophoresis recommended for patients of African, Middle Eastern, Mediterranean, or West Indian descent or if mean corpuscular volume is low.

- Spinal muscular atrophy (SMA). The most recent addition to ACOG's recommendations for general carrier screening due to the relatively high carrier frequency (1-in-40 to 1-in-60) and the severity of the disease, SMA causes degeneration of the spinal cord neurons, skeletal muscular atrophy, and overall weakness. Screening is via polymerase chain reaction for SMN1 copy number: 2 copies are normal, and 1 copy indicates a carrier of the SMN1 deletion. About 3% to 4% of patients will screen negative but still will be "carriers" due to having 2 copies of the SMN1 gene on 1 chromosome and no copies on the other chromosome.

All pregnant patients or patients considering pregnancy should be offered carrier screening as standard reproductive care, including screening for cystic fibrosis, hemoglobinopathies, and spinal muscular atrophy. Ethnic, panethnic, or expanded carrier screening (and patient-requested specific screening) all are acceptable options, and a standard screening and counseling protocol should be determined by the ObGyn or practice.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

The past year brought new information and guidance from the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) on many relevant obstetric topics, making it difficult to choose just a few for this Update. Opioid use in pregnancy was an obvious choice given the national media attention and the potential opportunity for intervention in pregnancy for both the mother and the fetus/newborn. Postpartum hemorrhage, an “oldie but goodie,” was chosen for several reasons: It got a new definition, a new focus on multidisciplinary care, and an exciting novel tool for the treatment toolbox. Finally, given the rapidly changing technology, new screening recommendations, and the complexity of counseling, carrier screening was chosen as a genetic hot topic for this year.

Opioids, obstetrics, and opportunities

Reddy UM, Davis JM, Ren Z, Greene MF; Opioid Use in Pregnancy, Neonatal Abstinence Syndrome, and Childhood Outcomes Workshop Invited Speakers. Opioid use in pregnancy, neonatal abstinence syndrome, and childhood outcomes: Executive summary of a joint workshop. Obstet Gynecol. 2017;130(1):10-28.

ACOG Committee on Obstetric Practice. ACOG committee opinion No. 711: Opioid use and opioid use disorder in pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2017;130(2):e81-e94.

The term "opioid epidemic" is omnipresent in both the lay media and the medical literature. In the past decade, the United States has had a huge increase in the number of opioid prescriptions, the rate of admissions and deaths due to prescription opioid misuse and abuse, and an increased rate of heroin use attributed to prior prescription opioid use.

Obstetrics is unique in that opioid use and abuse disorders affect 2 patients simultaneously (the mother and fetus), and the treatment options are somewhat at odds in that they need to balance a stable maternal status and intrauterine environment with the risk of neonatal abstinence syndrome (NAS). Additionally, pregnancy is an opportunity for a woman with opioid use disorder to have access to medical care (possibly for the first time) leading to the diagnosis and treatment of her disease. As the clinicians on the front line, obstetricians therefore require education and guidance on best practice for management of opioid use in pregnancy.

In 2017, Reddy and colleagues, as part of a joint workshop on opioid use in pregnancy, and a committee opinion from ACOG provided the following recommendations.

Screening

Universally screen for substance use, starting at the first prenatal visit; this is recommended over risk factor-based screening.

Use a validated screening tool. A tool such as a questionnaire is recommended as the first-line screening test (for example, the 4Ps screen, the National Institute on Drug Abuse Quick Screen, and the CRAFFT Screening Interview).

Do not universally screen urine and hair for drugs. This type of screening has many limitations, such as the limited number of substances tested, false-positive results, and inaccurate determination of the frequency or timing of drug use. Information regarding the consequences of the test must be provided, and patient consent must be obtained prior to performing the test.

Treatment

Use medication-assisted treatment with buprenorphine or methadone, which is preferred to medically supervised withdrawal. Medication-assisted treatment prevents withdrawal symptoms and cravings, decreases the risk of relapse, improves compliance with prenatal care and addiction treatment programs, and leads to better obstetric outcomes (higher birth weight, lower rate of preterm birth, lower perinatal mortality).

Know that buprenorphine has several advantages over methadone, including the convenience of an outpatient prescription, a lower risk of overdose, and improved neonatal outcomes (higher birth weight, lower doses of morphine to treat NAS, shorter treatment duration).

Prioritize methadone as the preferred option for pregnant women who are already receiving methadone treatment (changing to buprenorphine may precipitate withdrawal), those with a long-standing history of or multi-substance abuse, and those who have failed other treatment programs.

Prenatal care

Screen for comorbid conditions such as sexually transmitted infections, other medications or substance use, social conditions, and mental health disorders.

Perform ultrasonography serially to monitor fetal growth because of the increased risk of fetal growth restriction.

Consult with anesthesiology for pain control recommendations for labor and delivery and with neonatalogy/pediatrics for NAS counseling.

Intrapartum/postpartum care

Recognize heightened pain. Women with opioid use disorder have increased sensitivity to painful stimuli.

Continue the maintenance dose of methadone or buprenorphine throughout hospitalization, with short-acting opioids added for a brief period for postoperative pain.

Prioritize regional anesthesia for pain control in labor or for cesarean delivery.

Consider alternative therapies such as regional blocks, nonopioid medications (nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, acetaminophen), or relaxation/mindfulness training.

Avoid mixed antagonist and agonist narcotics (butorphanol, nalbuphine, pentazocine) as they may cause acute withdrawal.

Encourage breastfeeding to decrease the severity of NAS and maternal stress and increase maternal-child bonding and maternal confidence.

Offer contraceptive counseling and services immediately postpartum in the hospital, with strong consideration for long-acting reversible contraception.

Opioid prescribing practices

Opioids are prescribed in excess post–cesarean delivery. Several recent studies have demonstrated that most women are prescribed opioids post–cesarean delivery in excess of the amount they use (median 30–40 tablets prescribed, median 20 tablets used).1,2 The leftover opioid medication usually is not discarded and therefore is at risk for diversion or misuse. A small subset of patients will use all the opioids prescribed and feel as though they have not received enough medication.

Prescribe post–cesarean delivery opioids more appropriately by considering individual inpatient opioid requirements or a shared decision-making model.3

Prioritize acetaminophen and ibuprofen during breastfeeding. In a recent editorial in OBG Management, Robert L. Barbieri, MD, recommended that whenever possible, acetaminophen and ibuprofen should be the first-line treatment for breastfeeding women, and narcotics that are metabolized by CYP2D6 should be avoided to reduce the risk to the newborn.4

Universal screening for substance use should be performed in all pregnant women, and clinicians should offer medication-assisted treatment in conjunction with prenatal care and other supportive services as the standard therapy for opioid use disorder. More selective, patient-specific opioid prescribing practices should be applied in the obstetric population.

Read about new strategies for postpartum hemorrhage.

Postpartum hemorrhage: New definitions and new strategies for stemming the flow

ACOG Committee on Practice Bulletins—Obstetrics. ACOG practice bulletin No. 183: Postpartum hemorrhage. Obstet Gynecol. 2017;130(4):e168-e186.

From the very first sentence of the new ACOG practice bulletin, postpartum hemorrhage (PPH) is redefined as "cumulative blood loss greater than or equal to 1,000 mL or blood loss accompanied by signs or symptoms of hypovolemia within 24 hours after the birth process (includes intrapartum loss) regardless of route of delivery." Although this does not seem to be a huge change from the traditional teaching of a 500-mL blood loss at vaginal delivery and a 1,000-mL loss at cesarean delivery, it reflects a shift in focus from simply responding to a certain amount of bleeding to using a multidisciplinary action plan for treating this leading cause of maternal mortality worldwide.

Focus on developing a PPH action plan

As part of the shift toward a multidisciplinary action plan for PPH, all obstetric team members should be aware of the following:

- For most postpartum women, by the time they begin to show signs of hemodynamic compromise, the amount of blood loss approaches 25% of their total blood volume (1,500 mL). Lactic acidosis, systemic inflammation, and a consumptive coagulopathy result.

- Risk stratification prior to delivery, recognition and identification of the source of bleeding, and aggressive early resuscitation to prevent hypovolemia are paramount. Experience gleaned from trauma massive transfusion protocols suggests that judicious transfusion of packed red blood cells, fresh frozen plasma, and platelets in a 1:1:1 ratio is appropriate for obstetric patients. Additionally, patients with low fibrinogen levels should be treated with cryoprecipitate.

- The use of fixed transfusion ratios and standardized protocols for recognition and management of PPH has been demonstrated to increase earlier intervention and resolution of hemorrhage at an earlier stage, although the maternal outcomes results have been mixed.

- Multidisciplinary team drills and simulation exercises also should be considered to help solidify training of an institution's teams responsible for PPH response.

Novel management option: Tranexamic acid

In addition to these strategies, there is a new recommendation for managing refractory PPH: tranexamic acid, which works by binding to lysine receptors on plasminogen and plasmin, inhibiting plasmin-mediated fibrin degradation.5 Previously, tranexamic acid was known to be effective in trauma, heart surgery, and in patients with thrombophilias. Pacheco and colleagues recently demonstrated reduced mortality from obstetric bleeding if tranexamic acid was given within 3 hours of delivery, without increased thrombotic complications.5 ACOG recommends its use if initial medical therapy fails, while the World Health Organization strongly recommends that tranexamic acid be part of a standard PPH package for all cases of PPH (TABLE).6

Postpartum hemorrhage requires early, aggressive, and multidisciplinary coordination to ensure that 1) patients at risk for hemorrhage are identified for preventive measures; 2) existing hemorrhage is recognized and quickly treated, first with noninvasive methods and then with more definitive surgical treatments; and 3) blood product replacement follows an evidence-based standardized protocol. Tranexamic acid is recommended as an adjunct treatment for PPH (of any cause) and should be used within 3 hours of delivery.

Read about new ACOG guidance on prepregnancy and prenatal screening.

Carrier screening—choose something

ACOG Committee on Genetics. Committee opinion No. 690: Carrier screening in the age of genomic medicine. Obstet Gynecol. 2017;129(3):e35-e40.

ACOG Committee on Genetics. Committee opinion No. 691: Carrier screening for genetic conditions. Obstet Gynecol. 2017;129(3):e41-e55.

Ideally, carrier screening should be offered prior to pregnancy to fully inform couples of their reproductive risks and options for pregnancy. If not performed in the preconception period, carrier screening should be offered to all pregnant women. If a patient chooses screening and screens positive for a particular disorder, her reproductive partner should then be offered screening so that the risk of having an affected child can be determined.

New ACOG guidance on prepregnancy and prenatal screening

Carrier screening recommendations have evolved as the technology available has expanded. All 3 of the following strategies now are considered "acceptable" according to 2 recently published ACOG committee opinions.

Traditional ethnic-specific carrier screening, previously ACOG's sole recommendation, involves offering specific genetic screening to patients from populations with a high prevalence for certain conditions. One such example is Tay-Sachs disease screening in Ashkenazi Jewish patients.

Panethnic screening, which takes into account mixed or uncertain backgrounds, involves screening for a certain panel of disorders and is available to all patients regardless of their background (for example, cystic fibrosis screening offered to all pregnant patients).

Expanded carrier screening is when a large number of disorders can be screened for simultaneously for a lower cost than previous testing strategies. Expanded carrier screening panels vary in number and which conditions are tested by the laboratory. An ideal expanded carrier screening panel has been debated in the literature but not agreed on.7

ObGyns and practices therefore are encouraged to develop a standard counseling and screening protocol to offer to all their patients while being flexible to make available any patient-requested screening that is outside their protocol. Pretest and posttest counseling, including a thorough family history, is essential (as with any genetic testing) and should include residual risk after testing, potential need for specific familial mutation testing instead of general carrier screening, and issues with consanguinity.

Three essential screens

Regardless of the screening strategy chosen from the above options, 3 screening tests should be offered to all pregnant women or couples considering pregnancy (either individually or in the context of an expanded screening panel):

- Cystic fibrosis. At the least, a panel of the 23 most common mutations should be used. More expanded panels, which include hundreds of mutations, increase detection in non-Caucasian populations and for milder forms of the disease or infertility-related mutations.

- Hemoglobinopathies (sickle cell, α- and β-thalassemia). Complete blood count and red blood indices are recommended for all, with hemoglobin electrophoresis recommended for patients of African, Middle Eastern, Mediterranean, or West Indian descent or if mean corpuscular volume is low.

- Spinal muscular atrophy (SMA). The most recent addition to ACOG's recommendations for general carrier screening due to the relatively high carrier frequency (1-in-40 to 1-in-60) and the severity of the disease, SMA causes degeneration of the spinal cord neurons, skeletal muscular atrophy, and overall weakness. Screening is via polymerase chain reaction for SMN1 copy number: 2 copies are normal, and 1 copy indicates a carrier of the SMN1 deletion. About 3% to 4% of patients will screen negative but still will be "carriers" due to having 2 copies of the SMN1 gene on 1 chromosome and no copies on the other chromosome.

All pregnant patients or patients considering pregnancy should be offered carrier screening as standard reproductive care, including screening for cystic fibrosis, hemoglobinopathies, and spinal muscular atrophy. Ethnic, panethnic, or expanded carrier screening (and patient-requested specific screening) all are acceptable options, and a standard screening and counseling protocol should be determined by the ObGyn or practice.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

- Bateman BT, Cole NM, Maeda A, et al. Patterns of opioid prescription and use after cesarean delivery. Obstet Gynecol. 2017;130(1):29–35.

- Osmundson SS, Schornack LA, Grasch JL, Zuckerwise LC, Young JL, Richardson MD. Postdischarge opioid use after cesarean delivery. Obstet Gynecol. 2017;130(1):36–41.

- Prabhu M, McQuaid-Hanson E, Hopp S, et al. A shared decision-making intervention to guide opioid prescribing after cesarean delivery. Obstet Gynecol. 2017;130(1):42–46.

- Barbieri RL. Stop using codeine, oxycodone, hydrocodone, tramadol, and aspirin in women who are breastfeeding. OBG Manag. 2017;29(10):8–12.

- Pacheco LD, Hankins GD, Saad AF, Costantine MM, Chiossi G, Saade GR. Tranexamic acid for the management of obstetric hemorrhage. Obstet Gynecol. 2017;130(4);765–769.

- WHO recommendation on tranexamic acid for the treatment of postpartum haemorrhage. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2017.

- Stevens B, Krstic N, Jones M, Murphy L, Hoskovec J. Finding middle ground in constructing a clinically useful expanded carrier screening panel. Obstet Gynecol. 2017;130(2):279–284.

- Bateman BT, Cole NM, Maeda A, et al. Patterns of opioid prescription and use after cesarean delivery. Obstet Gynecol. 2017;130(1):29–35.

- Osmundson SS, Schornack LA, Grasch JL, Zuckerwise LC, Young JL, Richardson MD. Postdischarge opioid use after cesarean delivery. Obstet Gynecol. 2017;130(1):36–41.

- Prabhu M, McQuaid-Hanson E, Hopp S, et al. A shared decision-making intervention to guide opioid prescribing after cesarean delivery. Obstet Gynecol. 2017;130(1):42–46.

- Barbieri RL. Stop using codeine, oxycodone, hydrocodone, tramadol, and aspirin in women who are breastfeeding. OBG Manag. 2017;29(10):8–12.

- Pacheco LD, Hankins GD, Saad AF, Costantine MM, Chiossi G, Saade GR. Tranexamic acid for the management of obstetric hemorrhage. Obstet Gynecol. 2017;130(4);765–769.

- WHO recommendation on tranexamic acid for the treatment of postpartum haemorrhage. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2017.

- Stevens B, Krstic N, Jones M, Murphy L, Hoskovec J. Finding middle ground in constructing a clinically useful expanded carrier screening panel. Obstet Gynecol. 2017;130(2):279–284.

8 common questions about newborn circumcision

In the United States, circumcision is the fourth most common surgical procedure—behind cataract removal, cesarean delivery, and joint replacement.1 This operation, which dates to ancient times, is chosen for medical, personal, or religious reasons. It is performed on 77% of males born in the United States and on 42% of those born elsewhere who are living in this country.2 Whether it is performed depends not only on the parents’ race, ethnic background, and religion but also on region: US circumcision rates range from 74% in the Midwest to 30% in the West, and in between are the Northeast (67%) and the South (61%).3

Circumcision is not without controversy. Some claim that it is unnecessary cosmetic surgery, that it is genital mutilation, that the patient cannot choose it or object to it, or that it decreases sexual satisfaction.

In this article, I review 8 common questions about circumcision and provide data-based answers to them.

1. Should a newborn be circumcised?

For many years, the medical benefits of circumcision were scientifically ambiguous. With no clear answers, some thought that parents should base their decision for or against circumcision not on any potential medical benefit but rather on their family or religious tradition, or on a social standard, that is, what the majority of families in their community do.

Over the past 20 years, a growing body of evidence has demonstrated real medical benefits of circumcision. In 2012, the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP), which previously had been neutral on the subject, issued a task force report concluding that the health benefits of circumcision outweigh its risks and justify access to the procedure.3,4 However, the report stopped short of recommending circumcision.

Opponents have expressed several concerns about circumcision. First, they say, it is painful and unnecessary, and performing it when life has just begun takes the decision away from the adult-to-be, who may want to be uncircumcised as an adult but will have no recourse. Second, they say circumcision will diminish the adult’s sexual pleasure. However, there is no proof this occurs, and it is unclear how the claim could be adequately verified.5

Health benefits of circumcision3

- Prevention of phimosis and balanoposthitis (inflammation of glans and foreskin), penile retraction disorders, and penile cancer

- Fewer infant urinary tract infections

- Decreased spread of human papillomavirus–related disease, including cervical cancer and its precursors, to sexual partners

- Lower risk of acquiring, harboring, and spreading human immunodeficiency virus infection, herpes virus infection, and other sexually transmitted diseases

- Easier genital hygiene

- No need for circumcision later in life, when the procedure is more involved

2. What is the best analgesia for circumcision?

Although in decades past circumcision was often performed without any analgesia, in the United States analgesia is now standard of care. The AAP Task Force on Circumcision formalized this standard in a 2012 policy statement.4 For newborn circumcision, analgesia can be given in the form of analgesic cream, penile ring block, or dorsal nerve block.

Analgesic EMLA cream (a mixture of local anesthetics such as lidocaine 2.5%/prilocaine 2.5%) is easy to use but is minimally effective in relieving circumcision pain,6 although some investigators have reported it is efficacious compared with placebo.7 When used, the analgesic cream is applied 30 to 60 minutes before circumcision.

Both penile ring block and dorsal nerve block with 1% lidocaine are easy to administer and are very effective.8,9 They are best used with buffered lidocaine, which partially relieves the burning that occurs with injection. With both methods, the smaller the needle used (preferably 30 gauge), the better.

These 2 block methods have different injection sites. For the ring block, small amounts of lidocaine (1 to 1.5 mL) are given in a series of injections around the entire circumference of the base of the penis. The dorsal block targets the 2 dorsal nerves located at 10 o’clock and 2 o’clock at the base of the penis. Epinephrine, given its vasoconstrictive properties and the potential for necrosis, should never be used with local analgesia for penile infiltration.

Analgesia can be supplemented with comfort measures, such as a pacifier, sugar water, gentle rubbing on the forehead, and soothing speech.10

Related article:

Circumcision impedes viral disease. Will opposition fade?

3. What conditions are required for safe circumcision?

As circumcision is not medically required and need not occur in the days immediately after birth, it should be performed only when conditions are optimal:

- A pediatrician or other practitioner must first examine the newborn.

- The newborn must be full-term, healthy, and stable.

- The best time to circumcise a baby born prematurely is right before discharge from the intensive care nursery.

- The penis must be of normal size and without anatomical defect—no micropenis, hypospadias, or penoscrotal webbing.

- The lower abdominal fat pad must not be so large that it will cause the shaft’s skin to cover the exposed penile head.

- If there is a family history of a bleeding disorder, the newborn must be evaluated for the disorder before the circumcision.

- The newborn must have received his vitamin K shot.

4. What is the best circumcision method?

Circumcision can be performed with the Gomco circumcision clamp, the Mogen circumcision clamp, or the PlastiBell circumcision device. Each device works well, provides excellent results, and has its pluses and minuses. Practitioners should use the device with which they are most familiar and comfortable, which likely will be the device they used in training.

In the United States, the Gomco clamp is perhaps the most commonly used device. It provides good cosmetic results, and its metal “bell” protects the entire head of the penis. Of the 3 methods, however, it is the most difficult—the partially cut foreskin must be threaded between the bell and the clamp frame before the clamp is tightened. In many cases, too, there is bleeding at the penile frenulum.

The Mogen clamp, another commonly used device, also is used in traditional Jewish circumcisions. Of the 3 methods, it is the quickest, produces the best hemostasis, and is associated with the least discomfort.10 To those unfamiliar with the method, there may seem to be a potential for amputation of the head of the penis, but actually there virtually is no risk, as an indentation on the penile side of the clamp protects the penile head.

The PlastiBell device is very easy to use but must stay on until the foreskin becomes necrotic and the bell and foreskin fall off on their own—a process that takes 7 to 10 days. Many parents dislike this method because its final result is not immediate and they have to contend with a medical implement during their newborn’s first week home.

Electrocautery is not recommended. Some clinicians, especially urologists, use electrocautery as the cutting mechanism for circumcision. A review of the literature, however, reveals that electrocautery has not been studied head-to-head against traditional techniques, and that various significant complications—transected penile head, severe burns, meatal stenosis—have been reported.11,12 It is certainly not a mainstream procedure for neonatal circumcision.

Evaluate penile anatomy for abnormalities

Before performing any circumcision, the head of the penis should be examined to rule out hypospadias or other penile abnormalities. This is because the foreskin is utilized in certain penile repair procedures. The pediatrician should perform an initial examination of the penis at the formal newborn physical within 24 hours of delivery. The clinician performing the circumcision should re-examine the penis just before the procedure is begun—by pushing back the foreskin as much as possible—as well as during the procedure, once the foreskin is lifted off the penile head but before the foreskin is excised.

Read about how to ensure the best outcome of circumcision.

5. When is the best time to perform a circumcision?

The medical literature provides no firm answer to this question. The younger the baby, the easier it is to perform a circumcision as a simple procedure with local anesthesia. The older the baby, the larger the penis and the more aware the baby will be of his surroundings. Both these factors will make the procedure more difficult.

Most clinicians would be reluctant to perform a circumcision in the office or clinic after the baby is 6 to 8 weeks old. If a family desires their son to be circumcised after that time—or a medical condition precludes earlier circumcision—the procedure is best performed by a pediatric urologist in the operating room.

Related article:

Circumcision accident: $1.3M verdict

6. What are the potential complications of circumcision?

The rate of circumcision complications is very low: 0.2%.13 That being said, the 3 most common types of complications are postoperative bleeding, infection, and damage to the penis.

Far and away the most common complication is postoperative bleeding , usually at the frenulum of the head of the penis (the 6 o’clock position). In most cases, the bleeding is light to moderate. It is controlled with direct pressure applied for several minutes, the use of processed gelatin (Gelfoam) or cellulose (Surgicel), sparing use of silver nitrate, or placement of a polyglycolic acid (Vicryl) 5-0 suture.

Infection, an unusual occurrence, is seen within 24 to 72 hours after circumcision. It is marked by swelling, redness, and a foul-smelling mucus discharge. This discharge must be differentiated from dried fibrin, which is commonly seen on the head of the penis in the days after circumcision but has no odor or association with erythema, fever, or infant fussiness. True infection should be treated, in collaboration with the child’s pediatrician, with a staphylococcal-sensitive penicillin (such as dicloxacillin).

More serious is damage to the penis, which ranges from accidental dilation of the meatus to partial amputation of the penile glans. Any such injury should immediately prompt a consultation with a pediatric urologist.

More of a nuisance than a complication is the sliding of the penile shaft’s skin up and over the glans. This is a relatively frequent occurrence after normal, successful circumcisions. Parents of an affected newborn should be instructed to gently slide the skin back until the head of the penis is completely exposed again. After several days, the skin will adhere to its proper position on the shaft.

- Just before the procedure, have a face-to-face discussion with the parents. Confirm that they want the circumcision done, explain exactly what it entails, and let them know they will receive complete aftercare instructions.

- Make sure one of the parents signs the consent form.

- Circumcise the right baby! Check the identification bracelet and confirm that the newborn’s hospital and chart numbers match.

- Prevent excessive hip movement by securing the baby's legs. The usual solution is a specially designed plastic restraint board with Velcro straps for the legs.

- Examine the infant’s penile anatomy prior to the procedure to make certain it is normal.

- For pain relief, administer enough analgesia, as either dorsal nerve block or penile ring block (the best methods). Before injection, draw the plunger of the syringe back to make certain that the needle is not in a blood vessel.

- During the procedure, make sure the entire membranous layer of foreskin covering the head of the penis is separated from the glans.

- Watch the penis for several minutes after the circumcision to make sure there is no bleeding.

7. What is a Jewish ritual circumcision?

For their newborn’s circumcision, Jewish parents may choose a bris ceremony, formally called a brit milah, in fulfillment of religious tradition. The ceremony involves a brief religious service, circumcision with the traditional Mogen clamp, a special blessing, and an official religious naming rite. The bris traditionally is performed by a mohel, a rabbi or other religious official trained in circumcision. Many parents have the bris done by a mohel who is a medical doctor. In the United States, the availability of both types of mohels varies.

8. Who should perform circumcisions—obstetricians or pediatricians?

The answer to this question depends on where you practice. In some communities or hospitals, the obstetrician performs newborn circumcision, while in other places the pediatrician does. In addition, depending on local circumstances or the specific population involved, circumcisions may be performed by a pediatric urologist, nurse practitioner, or even out of hospital by a trained religiously affiliated practitioner.

Obstetricians began doing circumcisions for 2 reasons. First, obstetricians are surgically trained whereas pediatricians are not. It was therefore thought to be more appropriate for obstetricians to do this minor surgical procedure. Second, circumcisions used to be done right in the delivery room shortly after delivery. It was thought that the crying induced by performing the circumcision helped clear the baby’s lungs and invigorated sluggish babies. Now, however, in-hospital circumcisions are usually done in the days following delivery, after the baby has had the opportunity to undergo his first physical examination to make sure that all is well and that the penile anatomy is normal.

Clinician experience, proper protocol contribute to a safe procedure

In the United States, a large percentage of male infants are circumcised. Although circumcision has known medical benefits, the procedure generally is performed for family, religious, or cultural reasons. Circumcision is a safe and straightforward procedure but has its risks and potential complications. As with most surgeries, the best outcomes are achieved by practitioners who are well trained, who perform the procedure under supervision until their experience is sufficient, and who follow correct protocol during the entire operation.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

- Dallas ME. The 10 most common surgeries in the US. Healthgrades website. https://www.healthgrades.com/explore/the-10-most-common-surgeries-in-the-us. Reviewed August 15, 2017. Accessed October 2, 2017.

- Laumann EO, Masi CM, Zuckerman EW. Circumcision in the United States: prevalence, prophylactic effects, and sexual practice. JAMA. 1997;277(13):1052–1057.

- American Academy of Pediatrics Task Force on Circumcision. Male circumcision. Pediatrics. 2012;130(3):e756–e785.

- American Academy of Pediatrics Task Force on Circumcision. Circumcision policy statement. Pediatrics. 2012;130(3):585–586.

- Morris BJ, Krieger JN. Does male circumcision affect sexual function, sensitivity, or satisfaction? A systematic review. J Sex Med. 2013;10(11):2644–2657.

- Howard FM, Howard CR, Fortune K, Generelli P, Zolnoun D, tenHoopen C. A randomized, placebo-controlled comparison of EMLA and dorsal penile nerve block for pain relief during neonatal circumcision. Prim Care Update Ob Gyns. 1998;5(4):196.

- Taddio A, Stevens B, Craig K, et al. Efficacy and safety of lidocaine-prilocaine cream for pain during circumcision. N Engl J Med. 1997;336(17):1197–1201.

- Lander J, Brady-Fryer B, Metcalfe JB, Nazarali S, Muttitt S. Comparison of ring block, dorsal penile nerve block, and topical anesthesia for neonatal circumcision: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 1997;278(24):2157–2162.

- Hardwick-Smith S, Mastrobattista JM, Wallace PA, Ritchey ML. Ring block for neonatal circumcision. Obstet Gynecol. 1998;91(6):930–934.

- Kaufman GE, Cimo S, Miller LW, Blass EM. An evaluation of the effects of sucrose on neonatal pain with 2 commonly used circumcision methods. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2002;186(3):564–568.

- Tucker SC, Cerqueiro J, Sterne GD, Bracka A. Circumcision: a refined technique and 5 year review. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2001;83(2):121–125.

- Fraser ID, Tjoe J. Circumcision using bipolar scissors can be a safe and simple operation. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2000;82(3):190–191.

- Wiswell TE, Geschke DW. Risks from circumcision during the first month of life compared with those for uncircumcised boys. Pediatrics. 1989;83(6):1011–1015.

In the United States, circumcision is the fourth most common surgical procedure—behind cataract removal, cesarean delivery, and joint replacement.1 This operation, which dates to ancient times, is chosen for medical, personal, or religious reasons. It is performed on 77% of males born in the United States and on 42% of those born elsewhere who are living in this country.2 Whether it is performed depends not only on the parents’ race, ethnic background, and religion but also on region: US circumcision rates range from 74% in the Midwest to 30% in the West, and in between are the Northeast (67%) and the South (61%).3

Circumcision is not without controversy. Some claim that it is unnecessary cosmetic surgery, that it is genital mutilation, that the patient cannot choose it or object to it, or that it decreases sexual satisfaction.

In this article, I review 8 common questions about circumcision and provide data-based answers to them.

1. Should a newborn be circumcised?

For many years, the medical benefits of circumcision were scientifically ambiguous. With no clear answers, some thought that parents should base their decision for or against circumcision not on any potential medical benefit but rather on their family or religious tradition, or on a social standard, that is, what the majority of families in their community do.

Over the past 20 years, a growing body of evidence has demonstrated real medical benefits of circumcision. In 2012, the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP), which previously had been neutral on the subject, issued a task force report concluding that the health benefits of circumcision outweigh its risks and justify access to the procedure.3,4 However, the report stopped short of recommending circumcision.

Opponents have expressed several concerns about circumcision. First, they say, it is painful and unnecessary, and performing it when life has just begun takes the decision away from the adult-to-be, who may want to be uncircumcised as an adult but will have no recourse. Second, they say circumcision will diminish the adult’s sexual pleasure. However, there is no proof this occurs, and it is unclear how the claim could be adequately verified.5

Health benefits of circumcision3

- Prevention of phimosis and balanoposthitis (inflammation of glans and foreskin), penile retraction disorders, and penile cancer

- Fewer infant urinary tract infections

- Decreased spread of human papillomavirus–related disease, including cervical cancer and its precursors, to sexual partners

- Lower risk of acquiring, harboring, and spreading human immunodeficiency virus infection, herpes virus infection, and other sexually transmitted diseases

- Easier genital hygiene

- No need for circumcision later in life, when the procedure is more involved

2. What is the best analgesia for circumcision?

Although in decades past circumcision was often performed without any analgesia, in the United States analgesia is now standard of care. The AAP Task Force on Circumcision formalized this standard in a 2012 policy statement.4 For newborn circumcision, analgesia can be given in the form of analgesic cream, penile ring block, or dorsal nerve block.

Analgesic EMLA cream (a mixture of local anesthetics such as lidocaine 2.5%/prilocaine 2.5%) is easy to use but is minimally effective in relieving circumcision pain,6 although some investigators have reported it is efficacious compared with placebo.7 When used, the analgesic cream is applied 30 to 60 minutes before circumcision.

Both penile ring block and dorsal nerve block with 1% lidocaine are easy to administer and are very effective.8,9 They are best used with buffered lidocaine, which partially relieves the burning that occurs with injection. With both methods, the smaller the needle used (preferably 30 gauge), the better.