User login

AI Algorithm Predicts Transfusion Need, Mortality Risk in Acute GI Bleeds

SAN DIEGO — , researchers reported at Digestive Disease Week® (DDW) 2025.

Acute GI bleeding is the most common cause of digestive disease–related hospitalization, with an estimated 500,000 hospital admissions annually. It’s known that predicting the need for red blood cell transfusion in the first 24 hours may improve resuscitation and decrease both morbidity and mortality.

However, an existing clinical score known as the Rockall Score does not perform well for predicting mortality, Xi (Nicole) Zhang, an MD-PhD student at McGill University, Montreal, Quebec, Canada, told attendees at DDW. With an area under the curve of 0.65-0.75, better prediction is needed, said Zhang, whose coresearchers included Dennis Shung, MD, MHS, PhD, director of Applied Artificial Intelligence at Yale University School of Medicine, New Haven, Connecticut.

“We’d like to predict multiple outcomes in addition to mortality,” said Zhang, who is also a student at the Mila-Quebec Artificial Intelligence Institute.

As a result, the researchers turned to the TFM approach, applying it to ICU patients with acute GI bleeding to predict both the need for transfusion and in-hospital mortality risk. The all-cause mortality rate is up to 11%, according to a 2020 study by James Y. W. Lau, MD, and colleagues. The rebleeding rate of nonvariceal upper GI bleeds is up to 10.4%. Zhang said the rebleeding rate for variceal upper gastrointestinal bleeding is up to 65%.

The AI method the researchers used outperformed a standard deep learning model at predicting the need for transfusion and estimating mortality risk.

Defining the AI Framework

“Probabilistic flow matching is a class of generative artificial intelligence that learns how a simple distribution becomes a more complex distribution with ordinary differential equations,” Zhang told GI & Hepatology News. “For example, if you had a few lines and shapes you could learn how it could become a detailed portrait of a face. In our case, we start with a few blood pressure and heart rate measurements and learn the pattern of blood pressures and heart rates over time, particularly if they reflect clinical deterioration with hemodynamic instability.”

Another way to think about the underlying algorithm, Zhang said, is to think about a river with boats where the river flow determines where the boats end up. “We are trying to direct the boat to the correct dock by adjusting the flow of water in the canal. In this case we are mapping the distribution with the first few data points to the distribution with the entire patient trajectory.”

The information gained, she said, could be helpful in timing endoscopic evaluation or allocating red blood cell products for emergent transfusion.

Study Details

The researchers evaluated a cohort of 2602 patients admitted to the ICU, identified from the publicly available MIMIC-III database. They divided the patients into a training set of 2342 patients and an internal validation set of 260 patients. Input variables were severe liver disease comorbidity, administration of vasopressor medications, mean arterial blood pressure, and heart rate over the first 24 hours.

Excluded was hemoglobin, since the point was to test the trajectory of hemodynamic parameters independent of hemoglobin thresholds used to guide red blood cell transfusion.

The outcome measures were administration of packed red blood cell transfusion within 24 hours and all-cause hospital mortality.

The TFM was more accurate than a standard deep learning model in predicting red blood cell transfusion, with an accuracy of 93.6% vs 43.2%; P ≤ .001. It was also more accurate at predicting all-cause in-hospital mortality, with an accuracy of 89.5% vs 42.5%, P = .01.

The researchers concluded that the TFM approach was able to predict the hemodynamic trajectories of patients with acute GI bleeding defined as deviation and outperformed the baseline from the measured mean arterial pressure and heart rate.

Expert Perspective

“This is an exciting proof-of-concept study that shows generative AI methods may be applied to complex datasets in order to improve on our current predictive models and improve patient care,” said Jeremy Glissen Brown, MD, MSc, an assistant professor of medicine and a practicing gastroenterologist at Duke University who has published research on the use of AI in clinical practice. He reviewed the study for GI & Hepatology News but was not involved in the research.

“Future work will likely look into the implementation of a version of this model on real-time data.” he said. “We are at an exciting inflection point in predictive models within GI and clinical medicine. Predictive models based on deep learning and generative AI hold the promise of improving how we predict and treat disease states, but the excitement being generated with studies such as this needs to be balanced with the trade-offs inherent to the current paradigm of deep learning and generative models compared to more traditional regression-based models. These include many of the same ‘black box’ explainability questions that have risen in the age of convolutional neural networks as well as some method-specific questions due to the continuous and implicit nature of TFM.”

Elaborating on that, Glissen Brown said: “TFM, like many deep learning techniques, raises concerns about explainability that we’ve long seen with convolutional neural networks — the ‘black box’ problem, where it’s difficult to interpret exactly how and why the model arrives at a particular decision. But TFM also introduces unique challenges due to its continuous and implicit formulation. Since it often learns flows without explicitly defining intermediate representations or steps, it can be harder to trace the logic or pathways it uses to connect inputs to outputs. This makes standard interpretability tools less effective and calls for new techniques tailored to these continuous architectures.”

“This approach could have a real clinical impact,” said Robert Hirten, MD, associate professor of medicine and artificial intelligence, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York City, who also reviewed the study. “Accurately predicting transfusion needs and mortality risk in real time could support earlier, more targeted interventions for high-risk patients. While these findings still need to be validated in prospective studies, it could enhance ICU decision-making and resource allocation.”

“For the practicing gastroenterologist, we envision this system could help them figure out when to perform endoscopy in a patient admitted with acute gastrointestinal bleeding in the ICU at very high risk of exsanguination,” Zhang told GI & Hepatology News.

The approach, the researchers said, will be useful in identifying unique patient characteristics, make possible the identification of high-risk patients and lead to more personalized medicine.

Hirten, Zhang, and Shung had no disclosures. Glissen Brown reported consulting relationships with Medtronic, OdinVision, Doximity, and Olympus. The National Institutes of Health funded this study.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

SAN DIEGO — , researchers reported at Digestive Disease Week® (DDW) 2025.

Acute GI bleeding is the most common cause of digestive disease–related hospitalization, with an estimated 500,000 hospital admissions annually. It’s known that predicting the need for red blood cell transfusion in the first 24 hours may improve resuscitation and decrease both morbidity and mortality.

However, an existing clinical score known as the Rockall Score does not perform well for predicting mortality, Xi (Nicole) Zhang, an MD-PhD student at McGill University, Montreal, Quebec, Canada, told attendees at DDW. With an area under the curve of 0.65-0.75, better prediction is needed, said Zhang, whose coresearchers included Dennis Shung, MD, MHS, PhD, director of Applied Artificial Intelligence at Yale University School of Medicine, New Haven, Connecticut.

“We’d like to predict multiple outcomes in addition to mortality,” said Zhang, who is also a student at the Mila-Quebec Artificial Intelligence Institute.

As a result, the researchers turned to the TFM approach, applying it to ICU patients with acute GI bleeding to predict both the need for transfusion and in-hospital mortality risk. The all-cause mortality rate is up to 11%, according to a 2020 study by James Y. W. Lau, MD, and colleagues. The rebleeding rate of nonvariceal upper GI bleeds is up to 10.4%. Zhang said the rebleeding rate for variceal upper gastrointestinal bleeding is up to 65%.

The AI method the researchers used outperformed a standard deep learning model at predicting the need for transfusion and estimating mortality risk.

Defining the AI Framework

“Probabilistic flow matching is a class of generative artificial intelligence that learns how a simple distribution becomes a more complex distribution with ordinary differential equations,” Zhang told GI & Hepatology News. “For example, if you had a few lines and shapes you could learn how it could become a detailed portrait of a face. In our case, we start with a few blood pressure and heart rate measurements and learn the pattern of blood pressures and heart rates over time, particularly if they reflect clinical deterioration with hemodynamic instability.”

Another way to think about the underlying algorithm, Zhang said, is to think about a river with boats where the river flow determines where the boats end up. “We are trying to direct the boat to the correct dock by adjusting the flow of water in the canal. In this case we are mapping the distribution with the first few data points to the distribution with the entire patient trajectory.”

The information gained, she said, could be helpful in timing endoscopic evaluation or allocating red blood cell products for emergent transfusion.

Study Details

The researchers evaluated a cohort of 2602 patients admitted to the ICU, identified from the publicly available MIMIC-III database. They divided the patients into a training set of 2342 patients and an internal validation set of 260 patients. Input variables were severe liver disease comorbidity, administration of vasopressor medications, mean arterial blood pressure, and heart rate over the first 24 hours.

Excluded was hemoglobin, since the point was to test the trajectory of hemodynamic parameters independent of hemoglobin thresholds used to guide red blood cell transfusion.

The outcome measures were administration of packed red blood cell transfusion within 24 hours and all-cause hospital mortality.

The TFM was more accurate than a standard deep learning model in predicting red blood cell transfusion, with an accuracy of 93.6% vs 43.2%; P ≤ .001. It was also more accurate at predicting all-cause in-hospital mortality, with an accuracy of 89.5% vs 42.5%, P = .01.

The researchers concluded that the TFM approach was able to predict the hemodynamic trajectories of patients with acute GI bleeding defined as deviation and outperformed the baseline from the measured mean arterial pressure and heart rate.

Expert Perspective

“This is an exciting proof-of-concept study that shows generative AI methods may be applied to complex datasets in order to improve on our current predictive models and improve patient care,” said Jeremy Glissen Brown, MD, MSc, an assistant professor of medicine and a practicing gastroenterologist at Duke University who has published research on the use of AI in clinical practice. He reviewed the study for GI & Hepatology News but was not involved in the research.

“Future work will likely look into the implementation of a version of this model on real-time data.” he said. “We are at an exciting inflection point in predictive models within GI and clinical medicine. Predictive models based on deep learning and generative AI hold the promise of improving how we predict and treat disease states, but the excitement being generated with studies such as this needs to be balanced with the trade-offs inherent to the current paradigm of deep learning and generative models compared to more traditional regression-based models. These include many of the same ‘black box’ explainability questions that have risen in the age of convolutional neural networks as well as some method-specific questions due to the continuous and implicit nature of TFM.”

Elaborating on that, Glissen Brown said: “TFM, like many deep learning techniques, raises concerns about explainability that we’ve long seen with convolutional neural networks — the ‘black box’ problem, where it’s difficult to interpret exactly how and why the model arrives at a particular decision. But TFM also introduces unique challenges due to its continuous and implicit formulation. Since it often learns flows without explicitly defining intermediate representations or steps, it can be harder to trace the logic or pathways it uses to connect inputs to outputs. This makes standard interpretability tools less effective and calls for new techniques tailored to these continuous architectures.”

“This approach could have a real clinical impact,” said Robert Hirten, MD, associate professor of medicine and artificial intelligence, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York City, who also reviewed the study. “Accurately predicting transfusion needs and mortality risk in real time could support earlier, more targeted interventions for high-risk patients. While these findings still need to be validated in prospective studies, it could enhance ICU decision-making and resource allocation.”

“For the practicing gastroenterologist, we envision this system could help them figure out when to perform endoscopy in a patient admitted with acute gastrointestinal bleeding in the ICU at very high risk of exsanguination,” Zhang told GI & Hepatology News.

The approach, the researchers said, will be useful in identifying unique patient characteristics, make possible the identification of high-risk patients and lead to more personalized medicine.

Hirten, Zhang, and Shung had no disclosures. Glissen Brown reported consulting relationships with Medtronic, OdinVision, Doximity, and Olympus. The National Institutes of Health funded this study.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

SAN DIEGO — , researchers reported at Digestive Disease Week® (DDW) 2025.

Acute GI bleeding is the most common cause of digestive disease–related hospitalization, with an estimated 500,000 hospital admissions annually. It’s known that predicting the need for red blood cell transfusion in the first 24 hours may improve resuscitation and decrease both morbidity and mortality.

However, an existing clinical score known as the Rockall Score does not perform well for predicting mortality, Xi (Nicole) Zhang, an MD-PhD student at McGill University, Montreal, Quebec, Canada, told attendees at DDW. With an area under the curve of 0.65-0.75, better prediction is needed, said Zhang, whose coresearchers included Dennis Shung, MD, MHS, PhD, director of Applied Artificial Intelligence at Yale University School of Medicine, New Haven, Connecticut.

“We’d like to predict multiple outcomes in addition to mortality,” said Zhang, who is also a student at the Mila-Quebec Artificial Intelligence Institute.

As a result, the researchers turned to the TFM approach, applying it to ICU patients with acute GI bleeding to predict both the need for transfusion and in-hospital mortality risk. The all-cause mortality rate is up to 11%, according to a 2020 study by James Y. W. Lau, MD, and colleagues. The rebleeding rate of nonvariceal upper GI bleeds is up to 10.4%. Zhang said the rebleeding rate for variceal upper gastrointestinal bleeding is up to 65%.

The AI method the researchers used outperformed a standard deep learning model at predicting the need for transfusion and estimating mortality risk.

Defining the AI Framework

“Probabilistic flow matching is a class of generative artificial intelligence that learns how a simple distribution becomes a more complex distribution with ordinary differential equations,” Zhang told GI & Hepatology News. “For example, if you had a few lines and shapes you could learn how it could become a detailed portrait of a face. In our case, we start with a few blood pressure and heart rate measurements and learn the pattern of blood pressures and heart rates over time, particularly if they reflect clinical deterioration with hemodynamic instability.”

Another way to think about the underlying algorithm, Zhang said, is to think about a river with boats where the river flow determines where the boats end up. “We are trying to direct the boat to the correct dock by adjusting the flow of water in the canal. In this case we are mapping the distribution with the first few data points to the distribution with the entire patient trajectory.”

The information gained, she said, could be helpful in timing endoscopic evaluation or allocating red blood cell products for emergent transfusion.

Study Details

The researchers evaluated a cohort of 2602 patients admitted to the ICU, identified from the publicly available MIMIC-III database. They divided the patients into a training set of 2342 patients and an internal validation set of 260 patients. Input variables were severe liver disease comorbidity, administration of vasopressor medications, mean arterial blood pressure, and heart rate over the first 24 hours.

Excluded was hemoglobin, since the point was to test the trajectory of hemodynamic parameters independent of hemoglobin thresholds used to guide red blood cell transfusion.

The outcome measures were administration of packed red blood cell transfusion within 24 hours and all-cause hospital mortality.

The TFM was more accurate than a standard deep learning model in predicting red blood cell transfusion, with an accuracy of 93.6% vs 43.2%; P ≤ .001. It was also more accurate at predicting all-cause in-hospital mortality, with an accuracy of 89.5% vs 42.5%, P = .01.

The researchers concluded that the TFM approach was able to predict the hemodynamic trajectories of patients with acute GI bleeding defined as deviation and outperformed the baseline from the measured mean arterial pressure and heart rate.

Expert Perspective

“This is an exciting proof-of-concept study that shows generative AI methods may be applied to complex datasets in order to improve on our current predictive models and improve patient care,” said Jeremy Glissen Brown, MD, MSc, an assistant professor of medicine and a practicing gastroenterologist at Duke University who has published research on the use of AI in clinical practice. He reviewed the study for GI & Hepatology News but was not involved in the research.

“Future work will likely look into the implementation of a version of this model on real-time data.” he said. “We are at an exciting inflection point in predictive models within GI and clinical medicine. Predictive models based on deep learning and generative AI hold the promise of improving how we predict and treat disease states, but the excitement being generated with studies such as this needs to be balanced with the trade-offs inherent to the current paradigm of deep learning and generative models compared to more traditional regression-based models. These include many of the same ‘black box’ explainability questions that have risen in the age of convolutional neural networks as well as some method-specific questions due to the continuous and implicit nature of TFM.”

Elaborating on that, Glissen Brown said: “TFM, like many deep learning techniques, raises concerns about explainability that we’ve long seen with convolutional neural networks — the ‘black box’ problem, where it’s difficult to interpret exactly how and why the model arrives at a particular decision. But TFM also introduces unique challenges due to its continuous and implicit formulation. Since it often learns flows without explicitly defining intermediate representations or steps, it can be harder to trace the logic or pathways it uses to connect inputs to outputs. This makes standard interpretability tools less effective and calls for new techniques tailored to these continuous architectures.”

“This approach could have a real clinical impact,” said Robert Hirten, MD, associate professor of medicine and artificial intelligence, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York City, who also reviewed the study. “Accurately predicting transfusion needs and mortality risk in real time could support earlier, more targeted interventions for high-risk patients. While these findings still need to be validated in prospective studies, it could enhance ICU decision-making and resource allocation.”

“For the practicing gastroenterologist, we envision this system could help them figure out when to perform endoscopy in a patient admitted with acute gastrointestinal bleeding in the ICU at very high risk of exsanguination,” Zhang told GI & Hepatology News.

The approach, the researchers said, will be useful in identifying unique patient characteristics, make possible the identification of high-risk patients and lead to more personalized medicine.

Hirten, Zhang, and Shung had no disclosures. Glissen Brown reported consulting relationships with Medtronic, OdinVision, Doximity, and Olympus. The National Institutes of Health funded this study.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM DDW 2025

Ostomy Innovation Grabs ‘Shark Tank’ Win

The “Shark Tank” winning innovation at the American Gastroenterological Association (AGA) Tech Summit in Chicago this April has “life-altering” potential for ostomy patients, according to one of the judges, and eliminates the need for constant pouch wear.

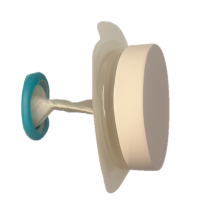

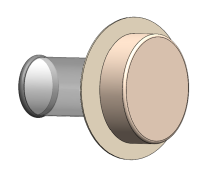

The innovation is called Twistomy and it is designed to replace current ostomy-pouch systems that can cause leaks, odor, skin irritation, embarrassment, and social and emotional distress. The AGA Committee for GI Innovation and Technology (CGIT) organizes the annual Tech Summit.

Twistomy’s winning design includes a flexible ring and sleeve, which are inserted into the stoma and secured on the outside with a set of rings that make up the housing unit attached to a standard wafer. The housing unit twists the sleeve closed, allowing the user to control fecal output. For evacuation, the user attaches a pouch, untwists the sleeve, evacuates cleanly and effectively, and then discards the pouch.

Twistomy cofounders Devon Horton, BS, senior bioengineer, and Lily Williams, BS, biomedical researcher and engineer, both work for the department of surgery at University of Colorado, Denver.

Horton said in an interview that when he was approached with the idea to create a better ostomy solution for a senior-year capstone project he was intrigued because the traditional ostomy system “has not changed in more than 70 years. It was crazy that no one had done anything to change that.”

The Twistomy team also won the Grand Prize this spring at the Emerging Medical Innovation Valuation Competition at the Design of Medical Devices Conference held at the University of Minnesota, Minneapolis.

Witnessing the Struggle as a CNA

Horton also works as a certified nursing assistant at an inpatient unit at University of Colorado Hospital and the ostomy patients he sees there every shift help drive his passion to find a better solution.

He hears the emotional stories of people who manage their ostomy daily.

“Many express feelings of depression and anxiety, feeling isolated with their severe inability to go out and do things because of the fear of the noise the stoma makes, or the crinkling of the plastic bag in a yoga class,” he said. “We want to help them regain that control of quality of life.”

They also hope to cut down on the ostomy management time. “Initial user testing [for Twistomy] was less than 75 seconds to insert and assemble,” he said. “I did an interview with a patient yesterday who said they probably spend an hour a day managing their ostomy,” including cleaning and replacing.

Horton and Williams have a patent on the device and currently use three-dimensional printing for the prototypes.

Williams said they are now conducting consumer discovery studies through the National Science Foundation and are interviewing 30 stakeholders — “anyone who has a relationship with an ostomy,” whether a colorectal surgeon, a gastrointestinal nurse, ostomy patients, or insurers.

Those interviews will help in refining the device so they can start consulting with manufacturers and work toward approval as a Class II medical device from the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA), Williams said.

Saving Healthcare Costs

Another potential benefit for Twistomy is its ability to cut healthcare costs, Horton said. Traditional ostomies are prone to leakage, which can lead to peristomal skin complications.

He pointed to a National Institutes of Health analysis that found that on average peristomal skin complications caused upwards of $80,000 more per ostomy patient in increased healthcare costs over a 3-month period than for those without the complications.

“With Twistomy, we are reducing leakage most likely to zero,” Horton said. “We set out to say if we could reduce [infections] by half or a little less than half, we can cut out those tens of thousands of dollars that insurance companies and payers are spending.”

Permanent and Temporary Ostomy Markets

He pointed out that not all ostomies are permanent ostomies, adding that the reversal rate “is about 65%.” Often those reversal surgeries cannot take place until peristomal skin complications have been healed.

“We’re not only hoping to market to the permanent stoma patients, but the patients with temporary stomas as well,” he said.

The team estimates it will need $4 million–$6 million in funding for manufacturing and consultation costs as well as costs involved in seeking FDA approval.

Horton and Williams project the housing unit cost will be $399 based on known out-of-pocket expenses for patients with ostomy care products and the unit would be replaced annually. Disposable elements would be an additional cost.

Assuming insurance acceptance of the product, he said, “With about an 80/20 insurance coverage, typical for many patients, it would be about $100 in out-of-pocket expenses per month to use our device, which is around the lower end of what a lot of patients are spending out of pocket.”

One of the Tech Summit judges, Somaya Albhaisi, MD, a gastroenterology/hepatology fellow at University of Southern California, Los Angeles, said in an interview that the Shark Tank results were unanimous among the five judges and Twistomy also took the fan favorite vote.

She said the teams were judged on quality of pitch, potential clinical impact, and feasibility of business plan. Teams got 5-7 minutes to pitch and answered questions afterward.

“Deep Understanding” of Patient Need

“They combined smart engineering with deep understanding of patient need, which is restoring control, dignity, and quality of life for ostomy users while also reducing healthcare costs. It is rare to see a solution this scalable and impactful. It was a deeply empathetic solution overall.” She noted that nearly 1 million people in the United States currently use an ostomy.

Ostomy users’ quality of life is compromised, and they often have mental health challenges, Albhaisi said. This innovation appears to offer easy use, more dignity and control.

The other four Shark Tank finalists were:

- AI Lumen, which developed a retroview camera system, which attaches to the colonoscope and enhances imaging to detect hidden polyps that may evade conventional endoscopes.

- Amplified Sciences, which developed an ultrasensitive diagnostic platform that detects biomarker activities in minute volumes of fluid from pancreatic cystic lesions, helping to stratify patients into low risk or potential malignancy, reducing unneeded surgeries, costs, and comorbidities.

- KITE Endoscopic Innovations, which designed the Dynaflex TruCut needle to offer a simpler endoscopic ultrasound (EUS)–guided biopsy procedure with fewer needle passes, deeper insights into tumor pathology, and more tissue for geonomic analysis.

- MicroSteer, which designed a device to facilitate semiautomated endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD) by decoupling the dissecting knife from the endoscope, enhancing safety and effectiveness during the procedure.

The Twistomy Team “Surprised Everyone”

The competitors’ scores were “very close,” one of the judges, Kevin Berliner, said in an interview. “The Twistomy team surprised everyone — the judges and the crowd — with their succinct, informative, and impactful pitch. That presentation disparity was the tiebreaker for me,” said Berliner, who works for Medtronic, a sponsor of the competition, in Chicago.

He said Horton and Williams were the youngest presenters and had the earliest stage pitch they judged, but they “outpresented other competitors in clarity, simplification, and storytelling.”

Also impressive was their description of their “commercially viable path to success” and their plan for the challenges ahead, he said.

Those challenges to get Twistomy to market center “on the ongoing changing climate we have with research funds lately,” Horton said. “We’re giving it an estimate of 3-5 years.”

Horton, Williams, Albhaisi, and Berliner reported no relevant financial relationships.

The “Shark Tank” winning innovation at the American Gastroenterological Association (AGA) Tech Summit in Chicago this April has “life-altering” potential for ostomy patients, according to one of the judges, and eliminates the need for constant pouch wear.

The innovation is called Twistomy and it is designed to replace current ostomy-pouch systems that can cause leaks, odor, skin irritation, embarrassment, and social and emotional distress. The AGA Committee for GI Innovation and Technology (CGIT) organizes the annual Tech Summit.

Twistomy’s winning design includes a flexible ring and sleeve, which are inserted into the stoma and secured on the outside with a set of rings that make up the housing unit attached to a standard wafer. The housing unit twists the sleeve closed, allowing the user to control fecal output. For evacuation, the user attaches a pouch, untwists the sleeve, evacuates cleanly and effectively, and then discards the pouch.

Twistomy cofounders Devon Horton, BS, senior bioengineer, and Lily Williams, BS, biomedical researcher and engineer, both work for the department of surgery at University of Colorado, Denver.

Horton said in an interview that when he was approached with the idea to create a better ostomy solution for a senior-year capstone project he was intrigued because the traditional ostomy system “has not changed in more than 70 years. It was crazy that no one had done anything to change that.”

The Twistomy team also won the Grand Prize this spring at the Emerging Medical Innovation Valuation Competition at the Design of Medical Devices Conference held at the University of Minnesota, Minneapolis.

Witnessing the Struggle as a CNA

Horton also works as a certified nursing assistant at an inpatient unit at University of Colorado Hospital and the ostomy patients he sees there every shift help drive his passion to find a better solution.

He hears the emotional stories of people who manage their ostomy daily.

“Many express feelings of depression and anxiety, feeling isolated with their severe inability to go out and do things because of the fear of the noise the stoma makes, or the crinkling of the plastic bag in a yoga class,” he said. “We want to help them regain that control of quality of life.”

They also hope to cut down on the ostomy management time. “Initial user testing [for Twistomy] was less than 75 seconds to insert and assemble,” he said. “I did an interview with a patient yesterday who said they probably spend an hour a day managing their ostomy,” including cleaning and replacing.

Horton and Williams have a patent on the device and currently use three-dimensional printing for the prototypes.

Williams said they are now conducting consumer discovery studies through the National Science Foundation and are interviewing 30 stakeholders — “anyone who has a relationship with an ostomy,” whether a colorectal surgeon, a gastrointestinal nurse, ostomy patients, or insurers.

Those interviews will help in refining the device so they can start consulting with manufacturers and work toward approval as a Class II medical device from the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA), Williams said.

Saving Healthcare Costs

Another potential benefit for Twistomy is its ability to cut healthcare costs, Horton said. Traditional ostomies are prone to leakage, which can lead to peristomal skin complications.

He pointed to a National Institutes of Health analysis that found that on average peristomal skin complications caused upwards of $80,000 more per ostomy patient in increased healthcare costs over a 3-month period than for those without the complications.

“With Twistomy, we are reducing leakage most likely to zero,” Horton said. “We set out to say if we could reduce [infections] by half or a little less than half, we can cut out those tens of thousands of dollars that insurance companies and payers are spending.”

Permanent and Temporary Ostomy Markets

He pointed out that not all ostomies are permanent ostomies, adding that the reversal rate “is about 65%.” Often those reversal surgeries cannot take place until peristomal skin complications have been healed.

“We’re not only hoping to market to the permanent stoma patients, but the patients with temporary stomas as well,” he said.

The team estimates it will need $4 million–$6 million in funding for manufacturing and consultation costs as well as costs involved in seeking FDA approval.

Horton and Williams project the housing unit cost will be $399 based on known out-of-pocket expenses for patients with ostomy care products and the unit would be replaced annually. Disposable elements would be an additional cost.

Assuming insurance acceptance of the product, he said, “With about an 80/20 insurance coverage, typical for many patients, it would be about $100 in out-of-pocket expenses per month to use our device, which is around the lower end of what a lot of patients are spending out of pocket.”

One of the Tech Summit judges, Somaya Albhaisi, MD, a gastroenterology/hepatology fellow at University of Southern California, Los Angeles, said in an interview that the Shark Tank results were unanimous among the five judges and Twistomy also took the fan favorite vote.

She said the teams were judged on quality of pitch, potential clinical impact, and feasibility of business plan. Teams got 5-7 minutes to pitch and answered questions afterward.

“Deep Understanding” of Patient Need

“They combined smart engineering with deep understanding of patient need, which is restoring control, dignity, and quality of life for ostomy users while also reducing healthcare costs. It is rare to see a solution this scalable and impactful. It was a deeply empathetic solution overall.” She noted that nearly 1 million people in the United States currently use an ostomy.

Ostomy users’ quality of life is compromised, and they often have mental health challenges, Albhaisi said. This innovation appears to offer easy use, more dignity and control.

The other four Shark Tank finalists were:

- AI Lumen, which developed a retroview camera system, which attaches to the colonoscope and enhances imaging to detect hidden polyps that may evade conventional endoscopes.

- Amplified Sciences, which developed an ultrasensitive diagnostic platform that detects biomarker activities in minute volumes of fluid from pancreatic cystic lesions, helping to stratify patients into low risk or potential malignancy, reducing unneeded surgeries, costs, and comorbidities.

- KITE Endoscopic Innovations, which designed the Dynaflex TruCut needle to offer a simpler endoscopic ultrasound (EUS)–guided biopsy procedure with fewer needle passes, deeper insights into tumor pathology, and more tissue for geonomic analysis.

- MicroSteer, which designed a device to facilitate semiautomated endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD) by decoupling the dissecting knife from the endoscope, enhancing safety and effectiveness during the procedure.

The Twistomy Team “Surprised Everyone”

The competitors’ scores were “very close,” one of the judges, Kevin Berliner, said in an interview. “The Twistomy team surprised everyone — the judges and the crowd — with their succinct, informative, and impactful pitch. That presentation disparity was the tiebreaker for me,” said Berliner, who works for Medtronic, a sponsor of the competition, in Chicago.

He said Horton and Williams were the youngest presenters and had the earliest stage pitch they judged, but they “outpresented other competitors in clarity, simplification, and storytelling.”

Also impressive was their description of their “commercially viable path to success” and their plan for the challenges ahead, he said.

Those challenges to get Twistomy to market center “on the ongoing changing climate we have with research funds lately,” Horton said. “We’re giving it an estimate of 3-5 years.”

Horton, Williams, Albhaisi, and Berliner reported no relevant financial relationships.

The “Shark Tank” winning innovation at the American Gastroenterological Association (AGA) Tech Summit in Chicago this April has “life-altering” potential for ostomy patients, according to one of the judges, and eliminates the need for constant pouch wear.

The innovation is called Twistomy and it is designed to replace current ostomy-pouch systems that can cause leaks, odor, skin irritation, embarrassment, and social and emotional distress. The AGA Committee for GI Innovation and Technology (CGIT) organizes the annual Tech Summit.

Twistomy’s winning design includes a flexible ring and sleeve, which are inserted into the stoma and secured on the outside with a set of rings that make up the housing unit attached to a standard wafer. The housing unit twists the sleeve closed, allowing the user to control fecal output. For evacuation, the user attaches a pouch, untwists the sleeve, evacuates cleanly and effectively, and then discards the pouch.

Twistomy cofounders Devon Horton, BS, senior bioengineer, and Lily Williams, BS, biomedical researcher and engineer, both work for the department of surgery at University of Colorado, Denver.

Horton said in an interview that when he was approached with the idea to create a better ostomy solution for a senior-year capstone project he was intrigued because the traditional ostomy system “has not changed in more than 70 years. It was crazy that no one had done anything to change that.”

The Twistomy team also won the Grand Prize this spring at the Emerging Medical Innovation Valuation Competition at the Design of Medical Devices Conference held at the University of Minnesota, Minneapolis.

Witnessing the Struggle as a CNA

Horton also works as a certified nursing assistant at an inpatient unit at University of Colorado Hospital and the ostomy patients he sees there every shift help drive his passion to find a better solution.

He hears the emotional stories of people who manage their ostomy daily.

“Many express feelings of depression and anxiety, feeling isolated with their severe inability to go out and do things because of the fear of the noise the stoma makes, or the crinkling of the plastic bag in a yoga class,” he said. “We want to help them regain that control of quality of life.”

They also hope to cut down on the ostomy management time. “Initial user testing [for Twistomy] was less than 75 seconds to insert and assemble,” he said. “I did an interview with a patient yesterday who said they probably spend an hour a day managing their ostomy,” including cleaning and replacing.

Horton and Williams have a patent on the device and currently use three-dimensional printing for the prototypes.

Williams said they are now conducting consumer discovery studies through the National Science Foundation and are interviewing 30 stakeholders — “anyone who has a relationship with an ostomy,” whether a colorectal surgeon, a gastrointestinal nurse, ostomy patients, or insurers.

Those interviews will help in refining the device so they can start consulting with manufacturers and work toward approval as a Class II medical device from the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA), Williams said.

Saving Healthcare Costs

Another potential benefit for Twistomy is its ability to cut healthcare costs, Horton said. Traditional ostomies are prone to leakage, which can lead to peristomal skin complications.

He pointed to a National Institutes of Health analysis that found that on average peristomal skin complications caused upwards of $80,000 more per ostomy patient in increased healthcare costs over a 3-month period than for those without the complications.

“With Twistomy, we are reducing leakage most likely to zero,” Horton said. “We set out to say if we could reduce [infections] by half or a little less than half, we can cut out those tens of thousands of dollars that insurance companies and payers are spending.”

Permanent and Temporary Ostomy Markets

He pointed out that not all ostomies are permanent ostomies, adding that the reversal rate “is about 65%.” Often those reversal surgeries cannot take place until peristomal skin complications have been healed.

“We’re not only hoping to market to the permanent stoma patients, but the patients with temporary stomas as well,” he said.

The team estimates it will need $4 million–$6 million in funding for manufacturing and consultation costs as well as costs involved in seeking FDA approval.

Horton and Williams project the housing unit cost will be $399 based on known out-of-pocket expenses for patients with ostomy care products and the unit would be replaced annually. Disposable elements would be an additional cost.

Assuming insurance acceptance of the product, he said, “With about an 80/20 insurance coverage, typical for many patients, it would be about $100 in out-of-pocket expenses per month to use our device, which is around the lower end of what a lot of patients are spending out of pocket.”

One of the Tech Summit judges, Somaya Albhaisi, MD, a gastroenterology/hepatology fellow at University of Southern California, Los Angeles, said in an interview that the Shark Tank results were unanimous among the five judges and Twistomy also took the fan favorite vote.

She said the teams were judged on quality of pitch, potential clinical impact, and feasibility of business plan. Teams got 5-7 minutes to pitch and answered questions afterward.

“Deep Understanding” of Patient Need

“They combined smart engineering with deep understanding of patient need, which is restoring control, dignity, and quality of life for ostomy users while also reducing healthcare costs. It is rare to see a solution this scalable and impactful. It was a deeply empathetic solution overall.” She noted that nearly 1 million people in the United States currently use an ostomy.

Ostomy users’ quality of life is compromised, and they often have mental health challenges, Albhaisi said. This innovation appears to offer easy use, more dignity and control.

The other four Shark Tank finalists were:

- AI Lumen, which developed a retroview camera system, which attaches to the colonoscope and enhances imaging to detect hidden polyps that may evade conventional endoscopes.

- Amplified Sciences, which developed an ultrasensitive diagnostic platform that detects biomarker activities in minute volumes of fluid from pancreatic cystic lesions, helping to stratify patients into low risk or potential malignancy, reducing unneeded surgeries, costs, and comorbidities.

- KITE Endoscopic Innovations, which designed the Dynaflex TruCut needle to offer a simpler endoscopic ultrasound (EUS)–guided biopsy procedure with fewer needle passes, deeper insights into tumor pathology, and more tissue for geonomic analysis.

- MicroSteer, which designed a device to facilitate semiautomated endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD) by decoupling the dissecting knife from the endoscope, enhancing safety and effectiveness during the procedure.

The Twistomy Team “Surprised Everyone”

The competitors’ scores were “very close,” one of the judges, Kevin Berliner, said in an interview. “The Twistomy team surprised everyone — the judges and the crowd — with their succinct, informative, and impactful pitch. That presentation disparity was the tiebreaker for me,” said Berliner, who works for Medtronic, a sponsor of the competition, in Chicago.

He said Horton and Williams were the youngest presenters and had the earliest stage pitch they judged, but they “outpresented other competitors in clarity, simplification, and storytelling.”

Also impressive was their description of their “commercially viable path to success” and their plan for the challenges ahead, he said.

Those challenges to get Twistomy to market center “on the ongoing changing climate we have with research funds lately,” Horton said. “We’re giving it an estimate of 3-5 years.”

Horton, Williams, Albhaisi, and Berliner reported no relevant financial relationships.

Chatbot Helps Users Adopt a Low FODMAP Diet

SAN DIEGO — Low fermentable oligo-, di-, and monosaccharides and polyols (FODMAPs) dietary advice has been shown to be effective in easing bloating and abdominal pain, especially in patients with irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), but limited availability of dietitians makes delivering this advice challenging. Researchers from Thailand have successfully enlisted a chatbot to help.

In a randomized controlled trial, they found that chatbot-assisted dietary advice with brief guidance effectively reduced high FODMAP intake, bloating severity, and improved dietary knowledge, particularly in patients with bothersome bloating.

“Chatbot-assisted dietary advice for FODMAPs restriction was feasible and applicable in patients with bloating symptoms that had baseline symptoms of moderate severity,” study chief Pochara Somvanapanich, with the Division of Gastroenterology, Chulalongkorn University and King Chulalongkorn Memorial Hospital, Bangkok, Thailand, told GI & Hepatology News.

Somvanapanich, who developed the chatbot algorithm, presented the study results at Digestive Disease Week (DDW) 2025.

More Knowledge, Less Bloating

The trial enrolled 86 adults with disorders of gut-brain interaction experiencing bloating symptoms for more than 6 months and consuming more than seven high-FODMAPs items per week. Half of them had IBS.

At baseline, gastrointestinal (GI) symptoms and the ability to identify FODMAPs were assessed. All participants received a 5-minute consultation on FODMAPs avoidance from a GI fellow and were randomly allocated (stratified by IBS diagnosis and education) into two groups.

The chatbot-assisted group received real-time dietary advice via a chatbot which helped them identify high, low, and non-FODMAP foods from a list of more than 300 ingredients/dishes of Thai and western cuisines.

The control group received only brief advice on high FODMAPs restriction. Both groups used a diary app to log food intake and postprandial symptoms. Baseline bloating, abdominal pain and global symptoms severity were similar between the two groups. Data on 64 participants (32 in each group) were analyzed.

After 4 weeks, significantly more people in the chatbot group than the control group responded — achieving a 30% or greater reduction in daily worst bloating, abdominal pain or global symptoms (19 [59%] vs 10 [31%], P < .05). Responder rates were similar in the IBS and non-IBS subgroups.

Subgroup analysis revealed significant differences between groups only for participants with bothersome bloating, not those with mild bloating severity.

In those with bothersome bloating severity, the chatbot group had a higher response rate (69.5% vs 36.3%) and fewer bloating symptoms (P < .05). They also had a greater reduction in high FODMAPs intake (10 vs 23 items/week) and demonstrated improved knowledge in identifying FODMAPs (P < .05).

“Responders in a chatbot group consistently engaged more with the app, performing significantly more weekly item searches than nonresponders (P < .05),” the authors noted in their conference abstract.

“Our next step is to develop the chatbot-assisted approach for the reintroduction and personalization phase based on messenger applications (including Facebook Messenger and other messaging platforms),” Somvanapanich told GI & Hepatology News.

“Once we’ve gathered enough data to confirm these are working effectively, we definitely plan to create a one-stop service application for FODMAPs dietary advice,” Somvanapanich added.

Lack of Robust Data on Digital GI Health Apps

Commenting on this research for GI & Hepatology News, Sidhartha R. Sinha, MD, Director of Digital Health and Innovation, Division of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, Stanford University in Stanford, California, noted that there is a “notable lack of robust data supporting digital health tools in gastroenterology. Despite hundreds of apps available, very few are supported by well-designed trials.”

“The study demonstrated that chatbot-assisted dietary advice significantly improved bloating symptoms, reduced intake of high-FODMAP foods, and enhanced patients’ dietary knowledge compared to brief dietary counseling alone, especially in those with bothersome symptoms,” said Sinha, who wasn’t involved in the study.

“Patients actively used the chatbot to manage their symptoms, achieving a higher response rate than those in the control arm who received brief counseling on avoiding high-FODMAP food,” he noted.

Sinha said in his practice at Stanford, “in the heart of Silicon Valley,” patients do use digital resources to manage their GI symptoms, including diseases like IBS and inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) — and he believes this is “increasingly common nationally.”

“However, the need for evidence-based tools is critical and the lack here often prevents many practitioners from regularly recommending them to patients. This study aligns well with clinical practice, and supports the use of this particular app to improve IBS symptoms, particularly when access to dietitians is limited. These results support chatbot-assisted dietary management as a feasible, effective, and scalable approach to patient care,” Sinha told GI & Hepatology News.

The study received no commercial funding. Somvanapanich and Sinha had no relevant disclosures.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

SAN DIEGO — Low fermentable oligo-, di-, and monosaccharides and polyols (FODMAPs) dietary advice has been shown to be effective in easing bloating and abdominal pain, especially in patients with irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), but limited availability of dietitians makes delivering this advice challenging. Researchers from Thailand have successfully enlisted a chatbot to help.

In a randomized controlled trial, they found that chatbot-assisted dietary advice with brief guidance effectively reduced high FODMAP intake, bloating severity, and improved dietary knowledge, particularly in patients with bothersome bloating.

“Chatbot-assisted dietary advice for FODMAPs restriction was feasible and applicable in patients with bloating symptoms that had baseline symptoms of moderate severity,” study chief Pochara Somvanapanich, with the Division of Gastroenterology, Chulalongkorn University and King Chulalongkorn Memorial Hospital, Bangkok, Thailand, told GI & Hepatology News.

Somvanapanich, who developed the chatbot algorithm, presented the study results at Digestive Disease Week (DDW) 2025.

More Knowledge, Less Bloating

The trial enrolled 86 adults with disorders of gut-brain interaction experiencing bloating symptoms for more than 6 months and consuming more than seven high-FODMAPs items per week. Half of them had IBS.

At baseline, gastrointestinal (GI) symptoms and the ability to identify FODMAPs were assessed. All participants received a 5-minute consultation on FODMAPs avoidance from a GI fellow and were randomly allocated (stratified by IBS diagnosis and education) into two groups.

The chatbot-assisted group received real-time dietary advice via a chatbot which helped them identify high, low, and non-FODMAP foods from a list of more than 300 ingredients/dishes of Thai and western cuisines.

The control group received only brief advice on high FODMAPs restriction. Both groups used a diary app to log food intake and postprandial symptoms. Baseline bloating, abdominal pain and global symptoms severity were similar between the two groups. Data on 64 participants (32 in each group) were analyzed.

After 4 weeks, significantly more people in the chatbot group than the control group responded — achieving a 30% or greater reduction in daily worst bloating, abdominal pain or global symptoms (19 [59%] vs 10 [31%], P < .05). Responder rates were similar in the IBS and non-IBS subgroups.

Subgroup analysis revealed significant differences between groups only for participants with bothersome bloating, not those with mild bloating severity.

In those with bothersome bloating severity, the chatbot group had a higher response rate (69.5% vs 36.3%) and fewer bloating symptoms (P < .05). They also had a greater reduction in high FODMAPs intake (10 vs 23 items/week) and demonstrated improved knowledge in identifying FODMAPs (P < .05).

“Responders in a chatbot group consistently engaged more with the app, performing significantly more weekly item searches than nonresponders (P < .05),” the authors noted in their conference abstract.

“Our next step is to develop the chatbot-assisted approach for the reintroduction and personalization phase based on messenger applications (including Facebook Messenger and other messaging platforms),” Somvanapanich told GI & Hepatology News.

“Once we’ve gathered enough data to confirm these are working effectively, we definitely plan to create a one-stop service application for FODMAPs dietary advice,” Somvanapanich added.

Lack of Robust Data on Digital GI Health Apps

Commenting on this research for GI & Hepatology News, Sidhartha R. Sinha, MD, Director of Digital Health and Innovation, Division of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, Stanford University in Stanford, California, noted that there is a “notable lack of robust data supporting digital health tools in gastroenterology. Despite hundreds of apps available, very few are supported by well-designed trials.”

“The study demonstrated that chatbot-assisted dietary advice significantly improved bloating symptoms, reduced intake of high-FODMAP foods, and enhanced patients’ dietary knowledge compared to brief dietary counseling alone, especially in those with bothersome symptoms,” said Sinha, who wasn’t involved in the study.

“Patients actively used the chatbot to manage their symptoms, achieving a higher response rate than those in the control arm who received brief counseling on avoiding high-FODMAP food,” he noted.

Sinha said in his practice at Stanford, “in the heart of Silicon Valley,” patients do use digital resources to manage their GI symptoms, including diseases like IBS and inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) — and he believes this is “increasingly common nationally.”

“However, the need for evidence-based tools is critical and the lack here often prevents many practitioners from regularly recommending them to patients. This study aligns well with clinical practice, and supports the use of this particular app to improve IBS symptoms, particularly when access to dietitians is limited. These results support chatbot-assisted dietary management as a feasible, effective, and scalable approach to patient care,” Sinha told GI & Hepatology News.

The study received no commercial funding. Somvanapanich and Sinha had no relevant disclosures.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

SAN DIEGO — Low fermentable oligo-, di-, and monosaccharides and polyols (FODMAPs) dietary advice has been shown to be effective in easing bloating and abdominal pain, especially in patients with irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), but limited availability of dietitians makes delivering this advice challenging. Researchers from Thailand have successfully enlisted a chatbot to help.

In a randomized controlled trial, they found that chatbot-assisted dietary advice with brief guidance effectively reduced high FODMAP intake, bloating severity, and improved dietary knowledge, particularly in patients with bothersome bloating.

“Chatbot-assisted dietary advice for FODMAPs restriction was feasible and applicable in patients with bloating symptoms that had baseline symptoms of moderate severity,” study chief Pochara Somvanapanich, with the Division of Gastroenterology, Chulalongkorn University and King Chulalongkorn Memorial Hospital, Bangkok, Thailand, told GI & Hepatology News.

Somvanapanich, who developed the chatbot algorithm, presented the study results at Digestive Disease Week (DDW) 2025.

More Knowledge, Less Bloating

The trial enrolled 86 adults with disorders of gut-brain interaction experiencing bloating symptoms for more than 6 months and consuming more than seven high-FODMAPs items per week. Half of them had IBS.

At baseline, gastrointestinal (GI) symptoms and the ability to identify FODMAPs were assessed. All participants received a 5-minute consultation on FODMAPs avoidance from a GI fellow and were randomly allocated (stratified by IBS diagnosis and education) into two groups.

The chatbot-assisted group received real-time dietary advice via a chatbot which helped them identify high, low, and non-FODMAP foods from a list of more than 300 ingredients/dishes of Thai and western cuisines.

The control group received only brief advice on high FODMAPs restriction. Both groups used a diary app to log food intake and postprandial symptoms. Baseline bloating, abdominal pain and global symptoms severity were similar between the two groups. Data on 64 participants (32 in each group) were analyzed.

After 4 weeks, significantly more people in the chatbot group than the control group responded — achieving a 30% or greater reduction in daily worst bloating, abdominal pain or global symptoms (19 [59%] vs 10 [31%], P < .05). Responder rates were similar in the IBS and non-IBS subgroups.

Subgroup analysis revealed significant differences between groups only for participants with bothersome bloating, not those with mild bloating severity.

In those with bothersome bloating severity, the chatbot group had a higher response rate (69.5% vs 36.3%) and fewer bloating symptoms (P < .05). They also had a greater reduction in high FODMAPs intake (10 vs 23 items/week) and demonstrated improved knowledge in identifying FODMAPs (P < .05).

“Responders in a chatbot group consistently engaged more with the app, performing significantly more weekly item searches than nonresponders (P < .05),” the authors noted in their conference abstract.

“Our next step is to develop the chatbot-assisted approach for the reintroduction and personalization phase based on messenger applications (including Facebook Messenger and other messaging platforms),” Somvanapanich told GI & Hepatology News.

“Once we’ve gathered enough data to confirm these are working effectively, we definitely plan to create a one-stop service application for FODMAPs dietary advice,” Somvanapanich added.

Lack of Robust Data on Digital GI Health Apps

Commenting on this research for GI & Hepatology News, Sidhartha R. Sinha, MD, Director of Digital Health and Innovation, Division of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, Stanford University in Stanford, California, noted that there is a “notable lack of robust data supporting digital health tools in gastroenterology. Despite hundreds of apps available, very few are supported by well-designed trials.”

“The study demonstrated that chatbot-assisted dietary advice significantly improved bloating symptoms, reduced intake of high-FODMAP foods, and enhanced patients’ dietary knowledge compared to brief dietary counseling alone, especially in those with bothersome symptoms,” said Sinha, who wasn’t involved in the study.

“Patients actively used the chatbot to manage their symptoms, achieving a higher response rate than those in the control arm who received brief counseling on avoiding high-FODMAP food,” he noted.

Sinha said in his practice at Stanford, “in the heart of Silicon Valley,” patients do use digital resources to manage their GI symptoms, including diseases like IBS and inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) — and he believes this is “increasingly common nationally.”

“However, the need for evidence-based tools is critical and the lack here often prevents many practitioners from regularly recommending them to patients. This study aligns well with clinical practice, and supports the use of this particular app to improve IBS symptoms, particularly when access to dietitians is limited. These results support chatbot-assisted dietary management as a feasible, effective, and scalable approach to patient care,” Sinha told GI & Hepatology News.

The study received no commercial funding. Somvanapanich and Sinha had no relevant disclosures.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM DDW 2025

Blood-Based Test May Predict Crohn’s Disease 2 Years Before Onset

SAN DIEGO — Crohn’s disease (CD) has become more common in the United States, and an estimated 1 million Americans have the condition. Still, much is unknown about how to evaluate the individual risk for the disease.

“It’s pretty much accepted that Crohn’s disease does not begin at diagnosis,” said Ryan Ungaro, MD, associate professor of medicine at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York City, speaking at Digestive Disease Week (DDW)® 2025.

Although individual blood markers have been associated with the future risk for CD, what’s needed, he said, is to understand which combination of biomarkers are most predictive.

Now, .

It’s an early version that will likely be further improved and needs additional validation, Ungaro told GI & Hepatology News.

“Once we can accurately identify individuals at risk for developing Crohn’s disease, we can then imagine a number of potential interventions,” Ungaro said.

Approaches would vary depending on how far away the onset is estimated to be. For people who likely wouldn’t develop disease for many years, one intervention might be close monitoring to enable diagnosis in the earliest stages, when treatment works best, he said. Someone at a high risk of developing CD in the next 2 or 3 years, on the other hand, might be offered a pharmaceutical intervention.

Developing and Testing the Risk Score

To develop the risk score, Ungaro and colleagues analyzed data of 200 patients with CD and 100 healthy control participants from PREDICTS, a nested case-controlled study of active US military service members. The study is within the larger Department of Defense Serum Repository, which began in 1985 and has more than 62.5 million samples, all stored at −30 °C.

The researchers collected serum samples at four timepoints up to 6 or more years before the diagnosis. They assayed antimicrobial antibodies using the Prometheus Laboratories platform, proteomic markers using the Olink inflammation panel, and anti–granulocyte macrophage colony-stimulating factor autoantibodies using enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay.

Participants (median age, 33 years for both groups) were randomly divided into equally sized training and testing sets. In both the group, 83% of patients were White and about 90% were men.

Time-varying trajectories of marker abundance were estimated for each biomarker. Then, logistic regression modeled disease status as a function of each marker for different timepoints and multivariate modeling was performed via logistic LASSO regression.

A risk score to predict CD onset within 2 years was developed. Prediction models were fit on the testing set and predictive performance evaluated using receiver operating characteristic curves and area under the curve (AUC).

Blood proteins and antibodies have differing associations with CD depending on the time before diagnosis, the researchers found.

The integrative model to predict CD onset within 2 years incorporated 10 biomarkers associated significantly with CD onset.

The AUC for the model was 0.87 (considered good, with 1 indicating perfect discrimination). It produced a specificity of 99% and a positive predictive value of 84%.

The researchers stratified the model scores into quartiles and found the CD incidence within 2 years increased from 2% in the first quartile to 57.7% in the fourth. The relative risk of developing CD in the top quartile individuals vs lower quartile individuals was 10.4.

The serologic and proteomic markers show dynamic changes years before the diagnosis, Ungaro said.

A Strong Start

The research represents “an ambitious and exciting frontier for the future of IBD [inflammatory bowel disease] care,” said Victor G. Chedid, MD, MS, consultant and assistant professor of medicine at Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minnesota, who reviewed the findings but was not involved in the study.

Currently, physicians treat IBD once it manifests, and it’s difficult to predict who will get CD, he said.

The integrative model’s AUC of 0.87 is impressive, and its specificity and positive predictive value levels show it is highly accurate in predicting the onset of CD within 2 years, Chedid added.

Further validation in larger and more diverse population is needed, Chedid said, but he sees the potential for the model to be practical in clinical practice.

“Additionally, the use of blood-based biomarkers makes the model relatively noninvasive and easy to implement in a clinical setting,” he said.

Now, the research goal is to understand the best biomarkers for characterizing the different preclinical phases of CD and to test different interventions in prevention trials, Ungaro told GI & Hepatology News.

A few trials are planned or ongoing, he noted. The trial PIONIR trial will look at the impact of a specific diet on the risk of developing CD, and the INTERCEPT trial aims to develop a blood-based risk score that can identify individuals with a high risk of developing CD within 5 years after initial evaluation.

Ungaro reported being on the advisory board of and/or receiving speaker or consulting fees from AbbVie, Bristol Myer Squibb, Celltrion, ECM Therapeutics, Genentech, Jansen, Eli Lilly, Pfizer, Roivant, Sanofi, and Takeda. Chedid reported having no relevant disclosures.

The PROMISE Consortium is funded by the Helmsley Charitable Trust.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

SAN DIEGO — Crohn’s disease (CD) has become more common in the United States, and an estimated 1 million Americans have the condition. Still, much is unknown about how to evaluate the individual risk for the disease.

“It’s pretty much accepted that Crohn’s disease does not begin at diagnosis,” said Ryan Ungaro, MD, associate professor of medicine at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York City, speaking at Digestive Disease Week (DDW)® 2025.

Although individual blood markers have been associated with the future risk for CD, what’s needed, he said, is to understand which combination of biomarkers are most predictive.

Now, .

It’s an early version that will likely be further improved and needs additional validation, Ungaro told GI & Hepatology News.

“Once we can accurately identify individuals at risk for developing Crohn’s disease, we can then imagine a number of potential interventions,” Ungaro said.

Approaches would vary depending on how far away the onset is estimated to be. For people who likely wouldn’t develop disease for many years, one intervention might be close monitoring to enable diagnosis in the earliest stages, when treatment works best, he said. Someone at a high risk of developing CD in the next 2 or 3 years, on the other hand, might be offered a pharmaceutical intervention.

Developing and Testing the Risk Score

To develop the risk score, Ungaro and colleagues analyzed data of 200 patients with CD and 100 healthy control participants from PREDICTS, a nested case-controlled study of active US military service members. The study is within the larger Department of Defense Serum Repository, which began in 1985 and has more than 62.5 million samples, all stored at −30 °C.

The researchers collected serum samples at four timepoints up to 6 or more years before the diagnosis. They assayed antimicrobial antibodies using the Prometheus Laboratories platform, proteomic markers using the Olink inflammation panel, and anti–granulocyte macrophage colony-stimulating factor autoantibodies using enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay.

Participants (median age, 33 years for both groups) were randomly divided into equally sized training and testing sets. In both the group, 83% of patients were White and about 90% were men.

Time-varying trajectories of marker abundance were estimated for each biomarker. Then, logistic regression modeled disease status as a function of each marker for different timepoints and multivariate modeling was performed via logistic LASSO regression.

A risk score to predict CD onset within 2 years was developed. Prediction models were fit on the testing set and predictive performance evaluated using receiver operating characteristic curves and area under the curve (AUC).

Blood proteins and antibodies have differing associations with CD depending on the time before diagnosis, the researchers found.

The integrative model to predict CD onset within 2 years incorporated 10 biomarkers associated significantly with CD onset.

The AUC for the model was 0.87 (considered good, with 1 indicating perfect discrimination). It produced a specificity of 99% and a positive predictive value of 84%.

The researchers stratified the model scores into quartiles and found the CD incidence within 2 years increased from 2% in the first quartile to 57.7% in the fourth. The relative risk of developing CD in the top quartile individuals vs lower quartile individuals was 10.4.

The serologic and proteomic markers show dynamic changes years before the diagnosis, Ungaro said.

A Strong Start

The research represents “an ambitious and exciting frontier for the future of IBD [inflammatory bowel disease] care,” said Victor G. Chedid, MD, MS, consultant and assistant professor of medicine at Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minnesota, who reviewed the findings but was not involved in the study.

Currently, physicians treat IBD once it manifests, and it’s difficult to predict who will get CD, he said.

The integrative model’s AUC of 0.87 is impressive, and its specificity and positive predictive value levels show it is highly accurate in predicting the onset of CD within 2 years, Chedid added.

Further validation in larger and more diverse population is needed, Chedid said, but he sees the potential for the model to be practical in clinical practice.

“Additionally, the use of blood-based biomarkers makes the model relatively noninvasive and easy to implement in a clinical setting,” he said.

Now, the research goal is to understand the best biomarkers for characterizing the different preclinical phases of CD and to test different interventions in prevention trials, Ungaro told GI & Hepatology News.

A few trials are planned or ongoing, he noted. The trial PIONIR trial will look at the impact of a specific diet on the risk of developing CD, and the INTERCEPT trial aims to develop a blood-based risk score that can identify individuals with a high risk of developing CD within 5 years after initial evaluation.

Ungaro reported being on the advisory board of and/or receiving speaker or consulting fees from AbbVie, Bristol Myer Squibb, Celltrion, ECM Therapeutics, Genentech, Jansen, Eli Lilly, Pfizer, Roivant, Sanofi, and Takeda. Chedid reported having no relevant disclosures.

The PROMISE Consortium is funded by the Helmsley Charitable Trust.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

SAN DIEGO — Crohn’s disease (CD) has become more common in the United States, and an estimated 1 million Americans have the condition. Still, much is unknown about how to evaluate the individual risk for the disease.

“It’s pretty much accepted that Crohn’s disease does not begin at diagnosis,” said Ryan Ungaro, MD, associate professor of medicine at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York City, speaking at Digestive Disease Week (DDW)® 2025.

Although individual blood markers have been associated with the future risk for CD, what’s needed, he said, is to understand which combination of biomarkers are most predictive.

Now, .

It’s an early version that will likely be further improved and needs additional validation, Ungaro told GI & Hepatology News.

“Once we can accurately identify individuals at risk for developing Crohn’s disease, we can then imagine a number of potential interventions,” Ungaro said.

Approaches would vary depending on how far away the onset is estimated to be. For people who likely wouldn’t develop disease for many years, one intervention might be close monitoring to enable diagnosis in the earliest stages, when treatment works best, he said. Someone at a high risk of developing CD in the next 2 or 3 years, on the other hand, might be offered a pharmaceutical intervention.

Developing and Testing the Risk Score

To develop the risk score, Ungaro and colleagues analyzed data of 200 patients with CD and 100 healthy control participants from PREDICTS, a nested case-controlled study of active US military service members. The study is within the larger Department of Defense Serum Repository, which began in 1985 and has more than 62.5 million samples, all stored at −30 °C.

The researchers collected serum samples at four timepoints up to 6 or more years before the diagnosis. They assayed antimicrobial antibodies using the Prometheus Laboratories platform, proteomic markers using the Olink inflammation panel, and anti–granulocyte macrophage colony-stimulating factor autoantibodies using enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay.

Participants (median age, 33 years for both groups) were randomly divided into equally sized training and testing sets. In both the group, 83% of patients were White and about 90% were men.

Time-varying trajectories of marker abundance were estimated for each biomarker. Then, logistic regression modeled disease status as a function of each marker for different timepoints and multivariate modeling was performed via logistic LASSO regression.

A risk score to predict CD onset within 2 years was developed. Prediction models were fit on the testing set and predictive performance evaluated using receiver operating characteristic curves and area under the curve (AUC).

Blood proteins and antibodies have differing associations with CD depending on the time before diagnosis, the researchers found.

The integrative model to predict CD onset within 2 years incorporated 10 biomarkers associated significantly with CD onset.

The AUC for the model was 0.87 (considered good, with 1 indicating perfect discrimination). It produced a specificity of 99% and a positive predictive value of 84%.

The researchers stratified the model scores into quartiles and found the CD incidence within 2 years increased from 2% in the first quartile to 57.7% in the fourth. The relative risk of developing CD in the top quartile individuals vs lower quartile individuals was 10.4.

The serologic and proteomic markers show dynamic changes years before the diagnosis, Ungaro said.

A Strong Start

The research represents “an ambitious and exciting frontier for the future of IBD [inflammatory bowel disease] care,” said Victor G. Chedid, MD, MS, consultant and assistant professor of medicine at Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minnesota, who reviewed the findings but was not involved in the study.

Currently, physicians treat IBD once it manifests, and it’s difficult to predict who will get CD, he said.

The integrative model’s AUC of 0.87 is impressive, and its specificity and positive predictive value levels show it is highly accurate in predicting the onset of CD within 2 years, Chedid added.

Further validation in larger and more diverse population is needed, Chedid said, but he sees the potential for the model to be practical in clinical practice.

“Additionally, the use of blood-based biomarkers makes the model relatively noninvasive and easy to implement in a clinical setting,” he said.

Now, the research goal is to understand the best biomarkers for characterizing the different preclinical phases of CD and to test different interventions in prevention trials, Ungaro told GI & Hepatology News.

A few trials are planned or ongoing, he noted. The trial PIONIR trial will look at the impact of a specific diet on the risk of developing CD, and the INTERCEPT trial aims to develop a blood-based risk score that can identify individuals with a high risk of developing CD within 5 years after initial evaluation.

Ungaro reported being on the advisory board of and/or receiving speaker or consulting fees from AbbVie, Bristol Myer Squibb, Celltrion, ECM Therapeutics, Genentech, Jansen, Eli Lilly, Pfizer, Roivant, Sanofi, and Takeda. Chedid reported having no relevant disclosures.

The PROMISE Consortium is funded by the Helmsley Charitable Trust.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM DDW 2025

Precision-Medicine Approach Improves IBD Infliximab Outcomes

SAN DIEGO — In tough-to-treat chronic inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), a precision-medicine strategy based on patients’ molecular profiles showed efficacy in guiding anti–tumor necrosis factor (TNF) therapy treatment decisions to improve outcomes.