User login

Ulipristal reduces bleeding with contraceptive implant

Ulipristal acetate reduces breakthrough bleeding in women with etonogestrel implants, according to new findings.

After 30 days, patients treated with ulipristal were more satisfied with their bleeding profiles than were those given placebo, reported Rachel E. Zigler, MD, of the department of obstetrics and gynecology at Washington University in St. Louis and her colleagues.

About half of women experience unscheduled bleeding within the first 6 months of etonogestrel implantation, causing many to discontinue treatment. The etiology of this phenomenon is poorly understood.

“One leading theory is that sustained exposure to a progestin can lead to endometrial angiogenesis disruption, resulting in the development of a dense venous network that is fragile and prone to bleeding,” the researchers wrote in Obstetrics & Gynecology.

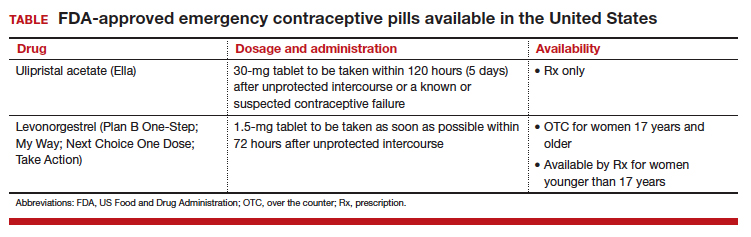

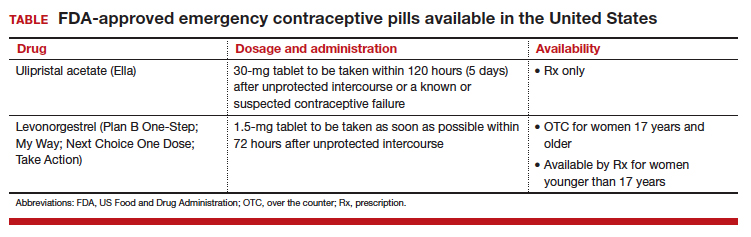

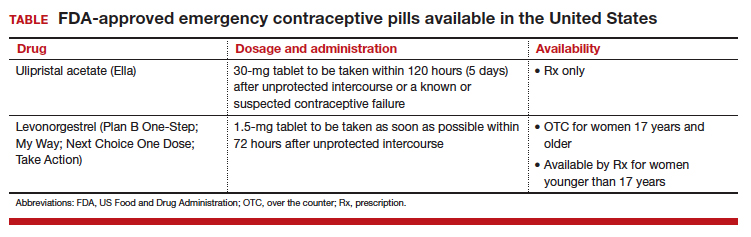

Ulipristal acetate is a selective progesterone receptor modulator approved for emergency contraception in the United States. Outside the United States, it is used to treat abnormal uterine bleeding in cases of uterine leiomyoma. Ulipristal acts directly upon myometrial and endometrial tissue and “may also displace local progestin within the uterus to counteract bleeding secondary to … a dense, fragile venous network.”

The double-blind, placebo-controlled study included 65 women aged 18-45 years with etonogestrel implants. Eligibility required that implants be in place for more than 90 days and less than 3 years and that participants experienced more than one bleeding episode over a 24-day time frame.

Patients received either 15 mg ulipristal (n = 32) or placebo (n = 33) daily for 7 days. From the first day of treatment until 30 days, patients self-reported bleeding events. Weekly phone questionnaires also were conducted to determine satisfaction with medication and side effects.

Ten days after starting treatment, bleeding resolved in 34% of patients treated with ulipristal versus 10% of patients given placebo (P = .03).

The ulipristal group reported a median of 5 fewer bleeding days, compared with the placebo group, over the month-long evaluation (7 vs. 12; P = .002). Treatment satisfaction rates were also better in the ulipristal group, with nearly three-quarters (72%) “very happy” with results versus about one-quarter (27%) of women who received placebo.

Consequently, more ulipristal patients desired to keep their implants, compared with placebo patients. All patients receiving ulipristal would consider ulipristal for breakthrough bleeding in the future, compared with two-thirds of patients in the placebo group.

Side effects were uncommon for both groups; the most common side effect was headache, reported in 9% in the ulipristal group and 19% in the placebo group.

“Increased satisfaction with the etonogestrel implant may lead to a decrease in discontinuation rates and potentially a decrease in unintended pregnancy rates in this population,” the researchers wrote.

Study funding was provided by the Society of Family Planning Research Fund, the Washington University Institute of Clinical and Translational Sciences, and the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences. The authors reported financial disclosures related to Bayer and Merck.

SOURCE: Zigler RE et al. Obstet Gynecol. 2018;132:888-94.

The recent trial by Zigler et al. showed that ulipristal acetate may reduce bleeding days in contraceptive implant users, but larger studies are needed, and concerns about logistics, dose, and toxicity must be addressed before clinical roll out, according to Eve Espey, MD.

The FDA halted the present trial after another ulipristal study overseas detected liver toxicity. The overseas study (for uterine leiomyoma) involved daily administration of ulipristal (5 mg) for 3 months, which is significantly longer than the present study for breakthrough bleeding. The European Medicines Agency has since determined that women with liver issues should not receive ulipristal and that others should have close liver monitoring before, during, and after ulipristal therapy.

Despite the above concerns, ulipristal still holds promise for a common clinical problem.

“This study contributes to the literature on management of bothersome bleeding with the contraceptive implant,” Dr. Espey said. “It is an important area because bothersome bleeding leads both to dissatisfaction and method discontinuation. As a recent Cochrane review pointed out, although several different medications have been used, studies are small and not yet conclusive. Despite these caveats, the findings were promising, similar to findings of prior work with a similar compound, mifepristone. Future directions would include clinical trials utilizing ulipristal acetate in a larger population powered for discontinuation.”

Dr. Espey is a professor in and chair of the department of obstetrics and gynecology and the family planning fellowship director at the University of New Mexico, Albuquerque. These comments are adapted from an interview. Dr. Espey said she had no relevant financial disclosures.

The recent trial by Zigler et al. showed that ulipristal acetate may reduce bleeding days in contraceptive implant users, but larger studies are needed, and concerns about logistics, dose, and toxicity must be addressed before clinical roll out, according to Eve Espey, MD.

The FDA halted the present trial after another ulipristal study overseas detected liver toxicity. The overseas study (for uterine leiomyoma) involved daily administration of ulipristal (5 mg) for 3 months, which is significantly longer than the present study for breakthrough bleeding. The European Medicines Agency has since determined that women with liver issues should not receive ulipristal and that others should have close liver monitoring before, during, and after ulipristal therapy.

Despite the above concerns, ulipristal still holds promise for a common clinical problem.

“This study contributes to the literature on management of bothersome bleeding with the contraceptive implant,” Dr. Espey said. “It is an important area because bothersome bleeding leads both to dissatisfaction and method discontinuation. As a recent Cochrane review pointed out, although several different medications have been used, studies are small and not yet conclusive. Despite these caveats, the findings were promising, similar to findings of prior work with a similar compound, mifepristone. Future directions would include clinical trials utilizing ulipristal acetate in a larger population powered for discontinuation.”

Dr. Espey is a professor in and chair of the department of obstetrics and gynecology and the family planning fellowship director at the University of New Mexico, Albuquerque. These comments are adapted from an interview. Dr. Espey said she had no relevant financial disclosures.

The recent trial by Zigler et al. showed that ulipristal acetate may reduce bleeding days in contraceptive implant users, but larger studies are needed, and concerns about logistics, dose, and toxicity must be addressed before clinical roll out, according to Eve Espey, MD.

The FDA halted the present trial after another ulipristal study overseas detected liver toxicity. The overseas study (for uterine leiomyoma) involved daily administration of ulipristal (5 mg) for 3 months, which is significantly longer than the present study for breakthrough bleeding. The European Medicines Agency has since determined that women with liver issues should not receive ulipristal and that others should have close liver monitoring before, during, and after ulipristal therapy.

Despite the above concerns, ulipristal still holds promise for a common clinical problem.

“This study contributes to the literature on management of bothersome bleeding with the contraceptive implant,” Dr. Espey said. “It is an important area because bothersome bleeding leads both to dissatisfaction and method discontinuation. As a recent Cochrane review pointed out, although several different medications have been used, studies are small and not yet conclusive. Despite these caveats, the findings were promising, similar to findings of prior work with a similar compound, mifepristone. Future directions would include clinical trials utilizing ulipristal acetate in a larger population powered for discontinuation.”

Dr. Espey is a professor in and chair of the department of obstetrics and gynecology and the family planning fellowship director at the University of New Mexico, Albuquerque. These comments are adapted from an interview. Dr. Espey said she had no relevant financial disclosures.

Ulipristal acetate reduces breakthrough bleeding in women with etonogestrel implants, according to new findings.

After 30 days, patients treated with ulipristal were more satisfied with their bleeding profiles than were those given placebo, reported Rachel E. Zigler, MD, of the department of obstetrics and gynecology at Washington University in St. Louis and her colleagues.

About half of women experience unscheduled bleeding within the first 6 months of etonogestrel implantation, causing many to discontinue treatment. The etiology of this phenomenon is poorly understood.

“One leading theory is that sustained exposure to a progestin can lead to endometrial angiogenesis disruption, resulting in the development of a dense venous network that is fragile and prone to bleeding,” the researchers wrote in Obstetrics & Gynecology.

Ulipristal acetate is a selective progesterone receptor modulator approved for emergency contraception in the United States. Outside the United States, it is used to treat abnormal uterine bleeding in cases of uterine leiomyoma. Ulipristal acts directly upon myometrial and endometrial tissue and “may also displace local progestin within the uterus to counteract bleeding secondary to … a dense, fragile venous network.”

The double-blind, placebo-controlled study included 65 women aged 18-45 years with etonogestrel implants. Eligibility required that implants be in place for more than 90 days and less than 3 years and that participants experienced more than one bleeding episode over a 24-day time frame.

Patients received either 15 mg ulipristal (n = 32) or placebo (n = 33) daily for 7 days. From the first day of treatment until 30 days, patients self-reported bleeding events. Weekly phone questionnaires also were conducted to determine satisfaction with medication and side effects.

Ten days after starting treatment, bleeding resolved in 34% of patients treated with ulipristal versus 10% of patients given placebo (P = .03).

The ulipristal group reported a median of 5 fewer bleeding days, compared with the placebo group, over the month-long evaluation (7 vs. 12; P = .002). Treatment satisfaction rates were also better in the ulipristal group, with nearly three-quarters (72%) “very happy” with results versus about one-quarter (27%) of women who received placebo.

Consequently, more ulipristal patients desired to keep their implants, compared with placebo patients. All patients receiving ulipristal would consider ulipristal for breakthrough bleeding in the future, compared with two-thirds of patients in the placebo group.

Side effects were uncommon for both groups; the most common side effect was headache, reported in 9% in the ulipristal group and 19% in the placebo group.

“Increased satisfaction with the etonogestrel implant may lead to a decrease in discontinuation rates and potentially a decrease in unintended pregnancy rates in this population,” the researchers wrote.

Study funding was provided by the Society of Family Planning Research Fund, the Washington University Institute of Clinical and Translational Sciences, and the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences. The authors reported financial disclosures related to Bayer and Merck.

SOURCE: Zigler RE et al. Obstet Gynecol. 2018;132:888-94.

Ulipristal acetate reduces breakthrough bleeding in women with etonogestrel implants, according to new findings.

After 30 days, patients treated with ulipristal were more satisfied with their bleeding profiles than were those given placebo, reported Rachel E. Zigler, MD, of the department of obstetrics and gynecology at Washington University in St. Louis and her colleagues.

About half of women experience unscheduled bleeding within the first 6 months of etonogestrel implantation, causing many to discontinue treatment. The etiology of this phenomenon is poorly understood.

“One leading theory is that sustained exposure to a progestin can lead to endometrial angiogenesis disruption, resulting in the development of a dense venous network that is fragile and prone to bleeding,” the researchers wrote in Obstetrics & Gynecology.

Ulipristal acetate is a selective progesterone receptor modulator approved for emergency contraception in the United States. Outside the United States, it is used to treat abnormal uterine bleeding in cases of uterine leiomyoma. Ulipristal acts directly upon myometrial and endometrial tissue and “may also displace local progestin within the uterus to counteract bleeding secondary to … a dense, fragile venous network.”

The double-blind, placebo-controlled study included 65 women aged 18-45 years with etonogestrel implants. Eligibility required that implants be in place for more than 90 days and less than 3 years and that participants experienced more than one bleeding episode over a 24-day time frame.

Patients received either 15 mg ulipristal (n = 32) or placebo (n = 33) daily for 7 days. From the first day of treatment until 30 days, patients self-reported bleeding events. Weekly phone questionnaires also were conducted to determine satisfaction with medication and side effects.

Ten days after starting treatment, bleeding resolved in 34% of patients treated with ulipristal versus 10% of patients given placebo (P = .03).

The ulipristal group reported a median of 5 fewer bleeding days, compared with the placebo group, over the month-long evaluation (7 vs. 12; P = .002). Treatment satisfaction rates were also better in the ulipristal group, with nearly three-quarters (72%) “very happy” with results versus about one-quarter (27%) of women who received placebo.

Consequently, more ulipristal patients desired to keep their implants, compared with placebo patients. All patients receiving ulipristal would consider ulipristal for breakthrough bleeding in the future, compared with two-thirds of patients in the placebo group.

Side effects were uncommon for both groups; the most common side effect was headache, reported in 9% in the ulipristal group and 19% in the placebo group.

“Increased satisfaction with the etonogestrel implant may lead to a decrease in discontinuation rates and potentially a decrease in unintended pregnancy rates in this population,” the researchers wrote.

Study funding was provided by the Society of Family Planning Research Fund, the Washington University Institute of Clinical and Translational Sciences, and the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences. The authors reported financial disclosures related to Bayer and Merck.

SOURCE: Zigler RE et al. Obstet Gynecol. 2018;132:888-94.

FROM OBSTETRICS & GYNECOLOGY

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Treatment with ulipristal was associated with 5 fewer bleeding days per month, compared with placebo (P = .002).

Study details: The double-blind, placebo-controlled trial involved 65 women with etonogestrel implants who reported more than one bleeding episode in a 24-day time frame.

Disclosures: The study was funded by the Society of Family Planning Research Fund, the Washington University Institute of Clinical and Translational Sciences, and the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS). The authors reported financial disclosures related to Bayer and Merck.

Source: Zigler RE et al. Obstet Gynecol. 2018;132:888-94.

Hormonal contraceptive use linked to leukemia risk in offspring

A nationwide cohort study found an association between a woman’s use of hormonal contraceptives and a small increased risk of nonlymphoid leukemia in her offspring.

Maternal use of hormonal contraception either during pregnancy or in the 3 months beforehand was associated with a 46% higher risk of any leukemia in the children (P = .011), compared with no use, Marie Hargreave, PhD, of the Danish Cancer Society Research Center and her coauthors reported in Lancet Oncology.

The study of 1,185,157 children born between 1996 and 2014 included data from the Danish Cancer Registry and Danish National Prescription Registry and followed children for a median of 9.3 years.

Use during pregnancy was associated with a 78% higher risk of any leukemia in the offspring (P = .070), and contraception use that stopped more than 3 months before pregnancy was associated with a 25% higher risk of any leukemia (P = .039).

The researchers estimated that maternal use of hormonal contraceptives up to and including during pregnancy would have resulted in about one additional case of leukemia per 47,170 children; in other words, 25 additional cases of leukemia in Denmark from contraceptive use from 1996 to 2014.

The increased risk appeared to be limited to nonlymphoid leukemia only. The risk with recent use was more than twofold higher (HR, 2.17), compared with nonuse, and use during pregnancy was associated with a nearly fourfold increase in the risk of leukemia (HR, 3.87).

“Sex hormones are considered to be potent carcinogens, and the causal association between in-utero exposure to the oestrogen analogue diethylstilbestrol and subsequent risk for adenocarcinoma of the vagina is firmly established,” Dr. Hargreave and her colleagues wrote. “The mechanism by which maternal use of hormones increases cancer risk in children is, however, still not clear.”

Recent use of combined oral contraceptive products was associated with a more than twofold increased risk of nonlymphoid leukemia in offspring, compared with no use. However progestin-only oral contraceptives and emergency contraception did not appear to increase in the risk of lymphoid or nonlymphoid leukemia.

The association was strongest in children aged 6-10 years, which the authors suggested was likely because the incidence of nonlymphoid leukemia increases after the age of 6 years.

While acknowledging that the small increase in leukemia risk was not a major safety concern for hormonal contraceptives, the authors commented that the results suggested the intrauterine hormonal environment could be a direction for research into the causes of leukemia.

The study was supported by the Danish Cancer Research Foundation and other foundations. One author reported grants from the sponsoring foundations and another author reported speaking fees from Jazz Pharmaceuticals and Shire Pharmaceuticals.

SOURCE: Hargreave M et al. Lancet Oncol. 2018 Sep 6. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(18)30479-0.

Estrogenic compounds could have a number of effects on the genomic machinery, that could in turn lead to an increased risk of leukemia in offspring. It may be that oral contraceptives cause epigenetic changes to fetal hematopoietic stem cells that lead to gene rearrangements and oxidative damage, which could then influence the risk of developing childhood leukemia.

This study opens a new avenue of investigation for a risk factor that might increase a child’s susceptibility to leukemia and is important in shedding more light on dose-response associations of exposures.

Dr. Maria S. Pombo-de-Oliveira is from the pediatric hematology-oncology research program at the Instituto Nacional de Câncer in Rio de Janeiro. These comments are adapted from an accompanying editorial (Lancet Oncol. 2018 Sep 6. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045[18]30509-6). Dr. Pombo-de-Oliveira reported having no conflicts of interest.

Estrogenic compounds could have a number of effects on the genomic machinery, that could in turn lead to an increased risk of leukemia in offspring. It may be that oral contraceptives cause epigenetic changes to fetal hematopoietic stem cells that lead to gene rearrangements and oxidative damage, which could then influence the risk of developing childhood leukemia.

This study opens a new avenue of investigation for a risk factor that might increase a child’s susceptibility to leukemia and is important in shedding more light on dose-response associations of exposures.

Dr. Maria S. Pombo-de-Oliveira is from the pediatric hematology-oncology research program at the Instituto Nacional de Câncer in Rio de Janeiro. These comments are adapted from an accompanying editorial (Lancet Oncol. 2018 Sep 6. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045[18]30509-6). Dr. Pombo-de-Oliveira reported having no conflicts of interest.

Estrogenic compounds could have a number of effects on the genomic machinery, that could in turn lead to an increased risk of leukemia in offspring. It may be that oral contraceptives cause epigenetic changes to fetal hematopoietic stem cells that lead to gene rearrangements and oxidative damage, which could then influence the risk of developing childhood leukemia.

This study opens a new avenue of investigation for a risk factor that might increase a child’s susceptibility to leukemia and is important in shedding more light on dose-response associations of exposures.

Dr. Maria S. Pombo-de-Oliveira is from the pediatric hematology-oncology research program at the Instituto Nacional de Câncer in Rio de Janeiro. These comments are adapted from an accompanying editorial (Lancet Oncol. 2018 Sep 6. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045[18]30509-6). Dr. Pombo-de-Oliveira reported having no conflicts of interest.

A nationwide cohort study found an association between a woman’s use of hormonal contraceptives and a small increased risk of nonlymphoid leukemia in her offspring.

Maternal use of hormonal contraception either during pregnancy or in the 3 months beforehand was associated with a 46% higher risk of any leukemia in the children (P = .011), compared with no use, Marie Hargreave, PhD, of the Danish Cancer Society Research Center and her coauthors reported in Lancet Oncology.

The study of 1,185,157 children born between 1996 and 2014 included data from the Danish Cancer Registry and Danish National Prescription Registry and followed children for a median of 9.3 years.

Use during pregnancy was associated with a 78% higher risk of any leukemia in the offspring (P = .070), and contraception use that stopped more than 3 months before pregnancy was associated with a 25% higher risk of any leukemia (P = .039).

The researchers estimated that maternal use of hormonal contraceptives up to and including during pregnancy would have resulted in about one additional case of leukemia per 47,170 children; in other words, 25 additional cases of leukemia in Denmark from contraceptive use from 1996 to 2014.

The increased risk appeared to be limited to nonlymphoid leukemia only. The risk with recent use was more than twofold higher (HR, 2.17), compared with nonuse, and use during pregnancy was associated with a nearly fourfold increase in the risk of leukemia (HR, 3.87).

“Sex hormones are considered to be potent carcinogens, and the causal association between in-utero exposure to the oestrogen analogue diethylstilbestrol and subsequent risk for adenocarcinoma of the vagina is firmly established,” Dr. Hargreave and her colleagues wrote. “The mechanism by which maternal use of hormones increases cancer risk in children is, however, still not clear.”

Recent use of combined oral contraceptive products was associated with a more than twofold increased risk of nonlymphoid leukemia in offspring, compared with no use. However progestin-only oral contraceptives and emergency contraception did not appear to increase in the risk of lymphoid or nonlymphoid leukemia.

The association was strongest in children aged 6-10 years, which the authors suggested was likely because the incidence of nonlymphoid leukemia increases after the age of 6 years.

While acknowledging that the small increase in leukemia risk was not a major safety concern for hormonal contraceptives, the authors commented that the results suggested the intrauterine hormonal environment could be a direction for research into the causes of leukemia.

The study was supported by the Danish Cancer Research Foundation and other foundations. One author reported grants from the sponsoring foundations and another author reported speaking fees from Jazz Pharmaceuticals and Shire Pharmaceuticals.

SOURCE: Hargreave M et al. Lancet Oncol. 2018 Sep 6. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(18)30479-0.

A nationwide cohort study found an association between a woman’s use of hormonal contraceptives and a small increased risk of nonlymphoid leukemia in her offspring.

Maternal use of hormonal contraception either during pregnancy or in the 3 months beforehand was associated with a 46% higher risk of any leukemia in the children (P = .011), compared with no use, Marie Hargreave, PhD, of the Danish Cancer Society Research Center and her coauthors reported in Lancet Oncology.

The study of 1,185,157 children born between 1996 and 2014 included data from the Danish Cancer Registry and Danish National Prescription Registry and followed children for a median of 9.3 years.

Use during pregnancy was associated with a 78% higher risk of any leukemia in the offspring (P = .070), and contraception use that stopped more than 3 months before pregnancy was associated with a 25% higher risk of any leukemia (P = .039).

The researchers estimated that maternal use of hormonal contraceptives up to and including during pregnancy would have resulted in about one additional case of leukemia per 47,170 children; in other words, 25 additional cases of leukemia in Denmark from contraceptive use from 1996 to 2014.

The increased risk appeared to be limited to nonlymphoid leukemia only. The risk with recent use was more than twofold higher (HR, 2.17), compared with nonuse, and use during pregnancy was associated with a nearly fourfold increase in the risk of leukemia (HR, 3.87).

“Sex hormones are considered to be potent carcinogens, and the causal association between in-utero exposure to the oestrogen analogue diethylstilbestrol and subsequent risk for adenocarcinoma of the vagina is firmly established,” Dr. Hargreave and her colleagues wrote. “The mechanism by which maternal use of hormones increases cancer risk in children is, however, still not clear.”

Recent use of combined oral contraceptive products was associated with a more than twofold increased risk of nonlymphoid leukemia in offspring, compared with no use. However progestin-only oral contraceptives and emergency contraception did not appear to increase in the risk of lymphoid or nonlymphoid leukemia.

The association was strongest in children aged 6-10 years, which the authors suggested was likely because the incidence of nonlymphoid leukemia increases after the age of 6 years.

While acknowledging that the small increase in leukemia risk was not a major safety concern for hormonal contraceptives, the authors commented that the results suggested the intrauterine hormonal environment could be a direction for research into the causes of leukemia.

The study was supported by the Danish Cancer Research Foundation and other foundations. One author reported grants from the sponsoring foundations and another author reported speaking fees from Jazz Pharmaceuticals and Shire Pharmaceuticals.

SOURCE: Hargreave M et al. Lancet Oncol. 2018 Sep 6. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(18)30479-0.

FROM LANCET ONCOLOGY

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Recent maternal hormonal contraceptive use was linked to one additional case of leukemia per 47,170 children.

Study details: Danish nationwide cohort study in 1,185,157 children.

Disclosures: The study was supported by the Danish Cancer Research Foundation and other foundations. One author reported grants from the sponsoring foundations and another author reported speaking fees from Jazz Pharmaceuticals and Shire Pharmaceuticals.

Source: Hargreave M et al. Lancet Oncol. 2018 Sep 6. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(18)30479-0.

2018 Update on contraception

Female permanent contraception is among the most widely used contraceptive methods worldwide. In the United States, more than 640,000 procedures are performed each year and it is used by 25% of women who use contraception.1–4 Female permanent contraception is achieved via salpingectomy, tubal interruption, or hysteroscopic techniques.

Essure, the only currently available hysteroscopic permanent contraception device, approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in 2002,5,6 has been implanted in more than 750,000 women worldwide.7 Essure was developed by Conceptus Inc, a small medical device company that was acquired by Bayer in 2013. The greatest uptake has been in the United States, which accounts for approximately 80% of procedures worldwide.7,8

Essure placement involves insertion of a nickel-titanium alloy coil with a stainless-steel inner coil, polyethylene terephthalate fibers, platinum marker bands, and silver-tin solder.9 The insert is approximately 4 cm in length and expands to 2 mm in diameter once deployed.9

Potential advantages of a hysteroscopic approach are that intra-abdominal surgery can be avoided and the procedure can be performed in an office without the need for general anesthesia.7 Due to these potential benefits, hysteroscopic permanent contraception with Essure underwent expedited review and received FDA approval without any comparative trials.1,5,10 However, there also are disadvantages: the method is not always successfully placed on first attempt and it is not immediately effective. Successful placement rates range between 60% and 98%, most commonly around 90%.11–15 Additionally, if placement is successful, alternative contraception must be used until a confirmatory radiologic test is performed at least 3 months after the procedure.9,11 Initially, hysterosalpingography was required to demonstrate a satisfactory insert location and successful tubal occlusion.11,16 Compliance with this testing is variable, ranging in studies from 13% to 71%.11 As of 2015, transvaginal ultrasonography showing insert retention and location has been approved as an alternative confirmatory method.9,11,16,17 Evidence suggests that the less invasive ultrasound option increases follow-up rates; while limited, one study noted an increase in follow-up rates from 77.5% for hysterosalpingogram to 88% (P = .008) for transvaginal ultrasound.18

Recent concerns about potential medical and safety issues have impacted approval status and marketing of hysteroscopic permanent contraception worldwide. In response to safety concerns, the FDA added a boxed safety warning and patient decision checklist in 2016.19 Bayer withdrew the device from all markets outside of the United States as of May 2017.20–22 In April 2018, the FDA restricted Essure sales in the United States only to providers and facilities who utilized an FDA-approved checklist to ensure the device met standards for safety and effectiveness.19 Most recently, Bayer announced that Essure would no longer be sold or distributed in the United States after December 31, 2018 (See “FDA Press Release”).23

"The US Food and Drug Administration was notified by Bayer that the Essure permanent birth control device will no longer be sold or distributed after December 31, 2018... The decision today to halt Essure sales also follows a series of earlier actions that the FDA took to address the reports of serious adverse events associated with its use. For women who have received an Essure implant, the postmarket safety of Essure will continue to be a top priority for the FDA. We expect Bayer to meet its postmarket obligations concerning this device."

Reference

- Statement from FDA Commissioner Scott Gottlieb, M.D., on manufacturer announcement to halt Essure sales in the U.S.; agency's continued commitment to postmarket review of Essure and keeping women informed [press release]. Silver Spring, MD; U.S. Food and Drug Administration. July 20, 2018.

So how did we get here? How did the promise of a “less invasive” approach for female permanent contraception get off course?

A search of the Manufacturer and User Facility Device Experience (MAUDE) database from Essure’s approval date in 2002 to December 2017 revealed 26,773 medical device reports, with more than 90% of those received in 2017 related to device removal.19 As more complications and complaints have been reported, the lack of comparative data has presented a problem for understanding the relative risk of the procedure as compared with laparoscopic techniques. Additionally, the approval studies lacked information about what happened to women who had an unsuccessful attempted hysteroscopic procedure. Without robust data sets or large trials, early research used evidence-based Markov modeling; findings suggested that hysteroscopic permanent contraception resulted in fewer women achieving successful permanent contraception and that the hysteroscopic procedure was not as effective as laparoscopic occlusion procedures with “typical” use.24,25

Over the past year, more clinical data have been published comparing hysteroscopic with laparoscopic permanent contraception procedures. In this article, we evaluate this information to help us better understand the relative efficacy and safety of the different permanent contraception methods and review recent articles describing removal techniques to further assist clinicians and patients considering such procedures.

Hysteroscopic versus laparoscopic procedures for permanent contraception

Bouillon K, Bertrand M, Bader G, et al. Association of hysteroscopic vs laparoscopic sterilization with procedural, gynecological, and medical outcomes. JAMA. 2018:319(4):375-387.

Antoun L, Smith P, Gupta J, et al. The feasibility, safety, and effectiveness of hysteroscopic sterilization compared with laparoscopic sterilization. Am J of Obstet Gynecol. 2017;217(5):570.e1-570.e6. doi:10.1016/j.ajog.2017.07.011.

Jokinen E, Heino A, Karipohja T, et al. Safety and effectiveness of female tubal sterilisation by hysteroscopy, laparoscopy, or laparotomy: a register based study. BJOG. 2017;124(12):1851-1857.

In this section, we present 3 recent studies that evaluate pregnancy outcomes and complications including reoperation or second permanent contraception procedure rates.

Data from France measure up to 3-year differences in adverse outcomes

Bouillon and colleagues aimed to identify differences in adverse outcome rates between hysteroscopic and laparoscopic permanent contraceptive methods. Utilizing national hospital discharge data in France, the researchers conducted a large database study review of records from more than 105,000 women aged 30 to 54 years receiving hysteroscopic or laparoscopic permanent contraception between 2010 and 2014. The database contains details based on the ICD-10 codes for all public and private hospitals in France, representing approximately 75% of the total population. Procedures were performed at 831 hospitals in 26 regions.

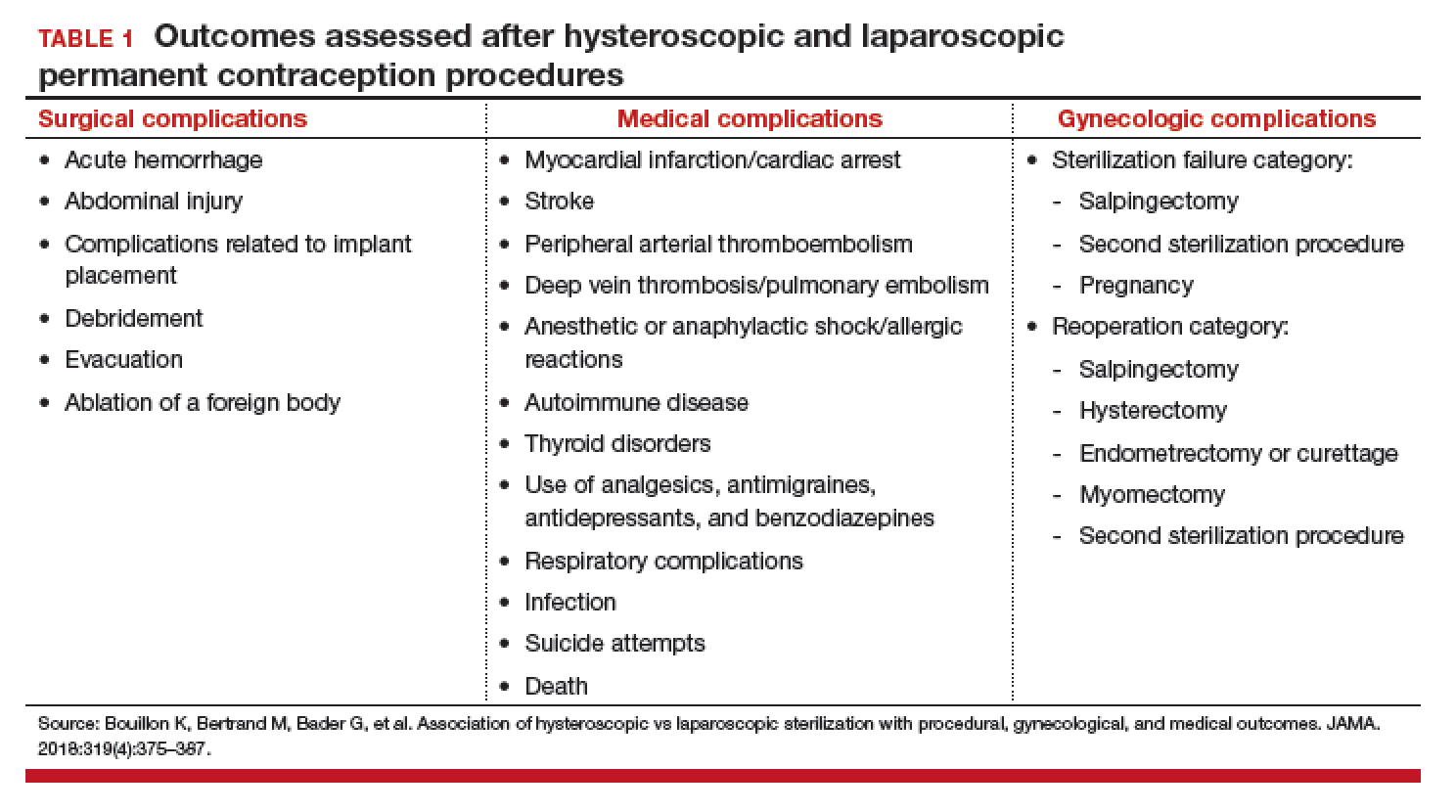

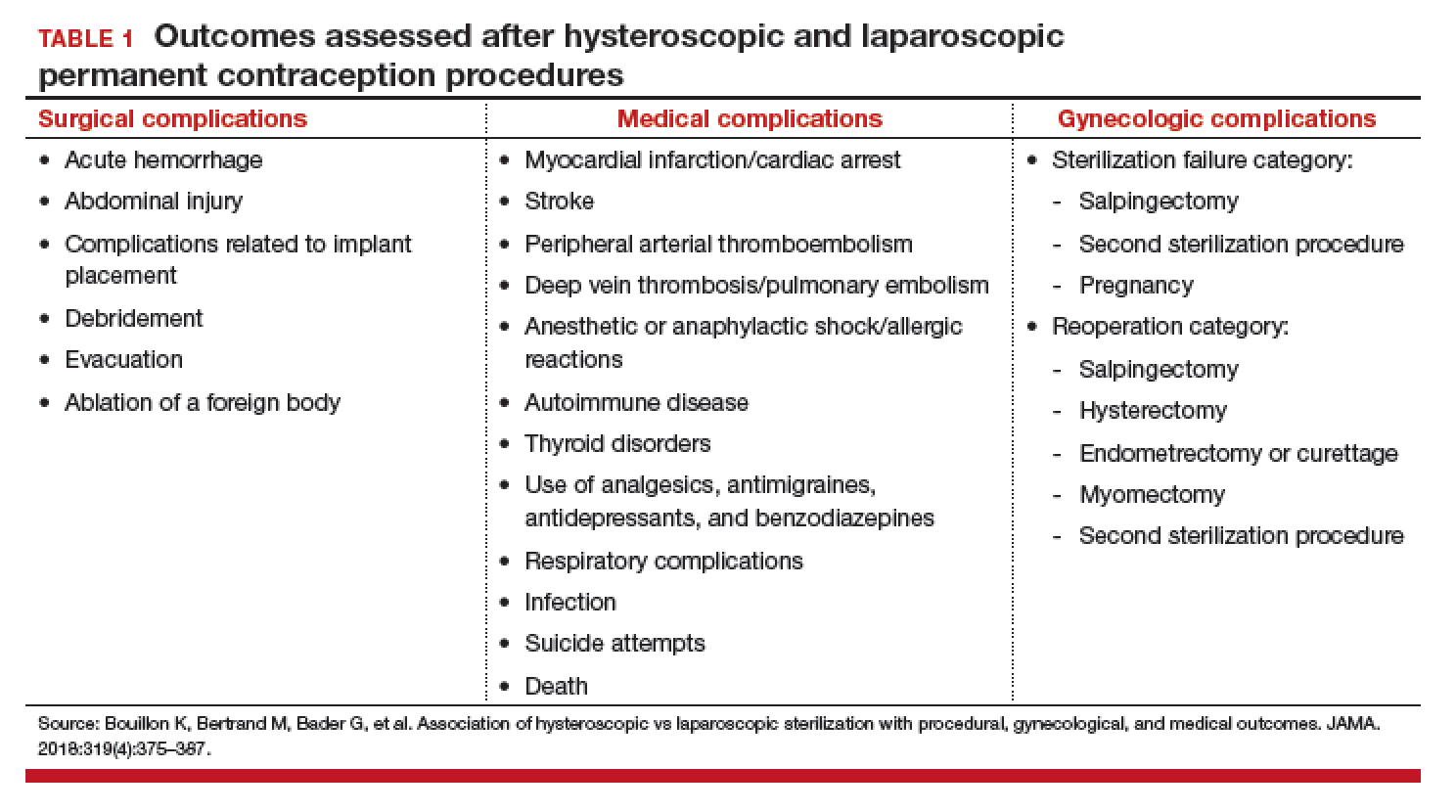

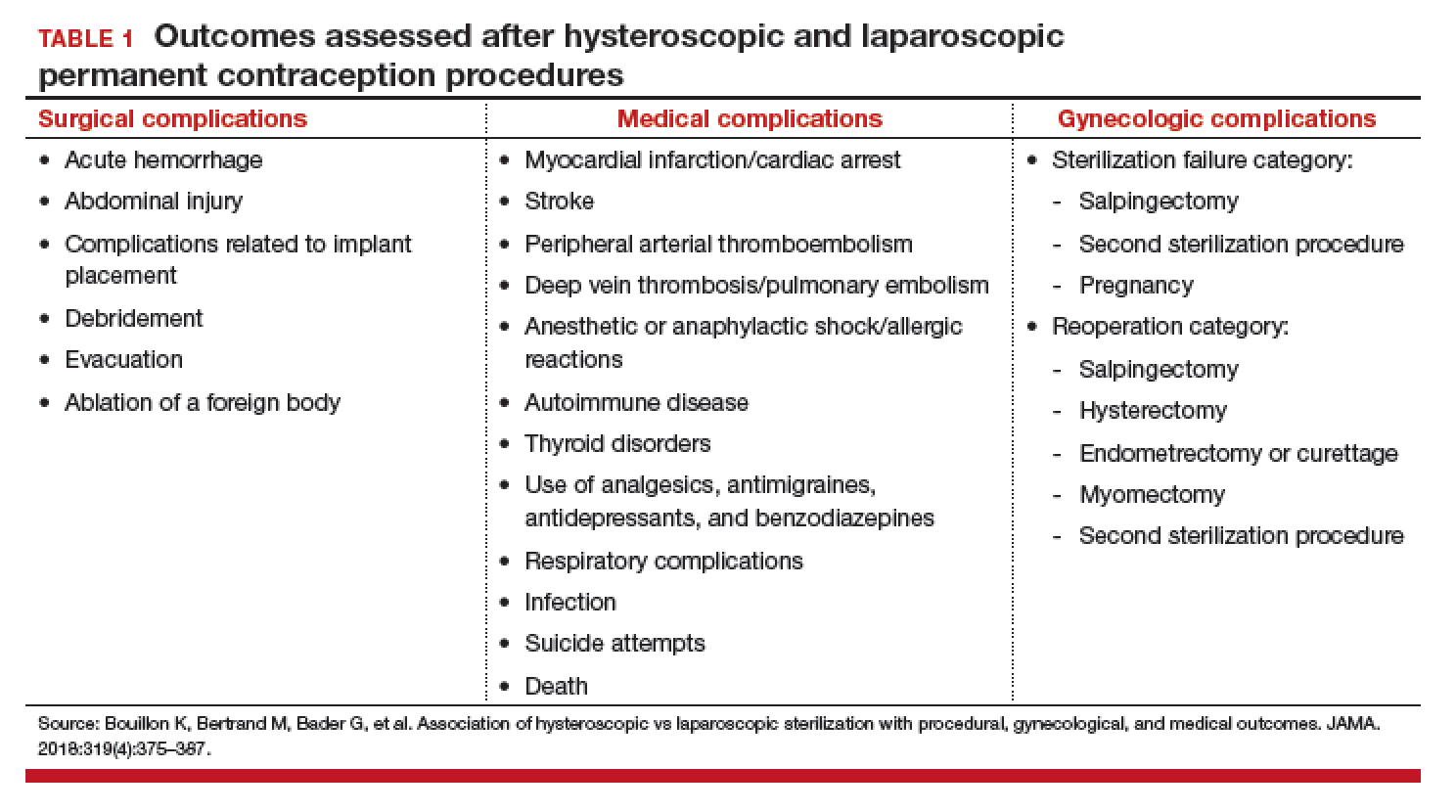

Adverse outcomes were divided into surgical, medical, and gynecologic complications (TABLE 1) and were assessed at 3 timepoints: at the time of procedure and at 1 and 3 years postprocedure.

Overall, 71,303 women (67.7%) underwent hysteroscopic permanent contraception procedures and 34,054 women (32.3%) underwent laparoscopic permanent contraception procedures. Immediate surgical and medical complications were significantly less common for women having hysteroscopic compared with laparoscopic procedures. Surgical complications at the time of the procedure occurred in 96 (0.13%) and 265 (0.78%) women, respectively (adjusted odds ratio [aOR], 0.18; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.14-0.23). Medical complications at the time of procedure occurred in 41 (0.06%) and 39 (0.11%) women, respectively (aOR, 0.51; 95% CI, 0.30-0.89).

However, gynecologic outcomes, including need for a second surgery to provide permanent contraception and overall failure rates (need for salpingectomy, a second permanent contraception procedure, or pregnancy) were significantly more common for women having hysteroscopic procedures. By 1 year after the procedure, 2,955 women (4.10%) who initially had a hysteroscopic procedure, and 56 women (0.16%) who had a laparoscopic procedure required a second permanent contraception surgery (adjusted hazard ratio [aHR], 25.99; 95% CI, 17.84-37.86). By the third year, additional procedures were performed in 3,230 (4.5%) and 97 (0.28%) women, respectively (aHR, 16.63; 95% CI, 12.50-22.20). Most (65%) of the repeat procedures were performed laparoscopically. Although pregnancy rates were significantly lower at 1 year among women who initially chose a hysteroscopic procedure (0.24% vs 0.41%; aHR, 0.70; 95% CI, 0.53-0.92), the rates did not differ at 3 years (0.48% vs 0.57%, respectively; aHR, 1.04; 95% CI, 0.83-1.30).

Most importantly, overall procedure failure rates were significantly higher at 1 year in women initially choosing a hysteroscopic approach compared with laparoscopic approach (3,446 [4.83%] vs 235 [0.69%] women; aHR, 7.11; 95% CI, 5.92-8.54). This difference persisted through 3 years (4,098 [5.75%] vs 438 [1.29%] women, respectively; aHR, 4.66; 95% CI, 4.06-5.34).

UK data indicate high reoperation rate for hysteroscopic procedures

Antoun and colleagues aimed to compare pregnancy rates, radiologic imaging follow-up rates, reoperations, and 30-day adverse outcomes, between hysteroscopic and laparoscopic permanent contraception methods. Conducted at a single teaching hospital in the United Kingdom, this study included 3,497 women who underwent procedures between 2005 and 2015. The data were collected prospectively for the 1,085 women who underwent hysteroscopic procedures and retrospectively for 2,412 women who had laparoscopic permanent contraception procedures with the Filshie clip.

Over the 10-year study period, hysteroscopic permanent contraception increased from 14.2% (40 of 280) of procedures in 2005 to 40.5% (150 of 350) of procedures in 2015 (P<.001). Overall, 2,400 women (99.5%) underwent successful laparoscopic permanent contraception, compared with 992 women (91.4%) in the hysteroscopic group (OR, 18.8; 95% CI, 10.2-34.4).

In the hysteroscopic group, 958 women (97%) returned for confirmatory testing, of whom 902 (91% of women with successful placement) underwent satisfactory confirmatory testing. There were 93 (8.6%) unsuccessful placements that were due to inability to visualize ostia or tubal stenosis (n = 72 [77.4%]), patient intolerance to procedure (n = 15 [16.1%]), or device failure (n = 6 [6.5%]).

The odds for reoperation were 6 times greater in the hysteroscopic group by 1 year after surgery (22 [2%] vs 8 [0.3%] women; OR, 6.2; 95% CI, 2.8-14.0). However, the 1-year pregnancy risk was similar between the 2 groups, with 3 reported pregnancies after hysteroscopic permanent contraception and 5 reported pregnancies after laparoscopic permanent contraception (OR, 1.3; 95% CI, 0.3-5.6).

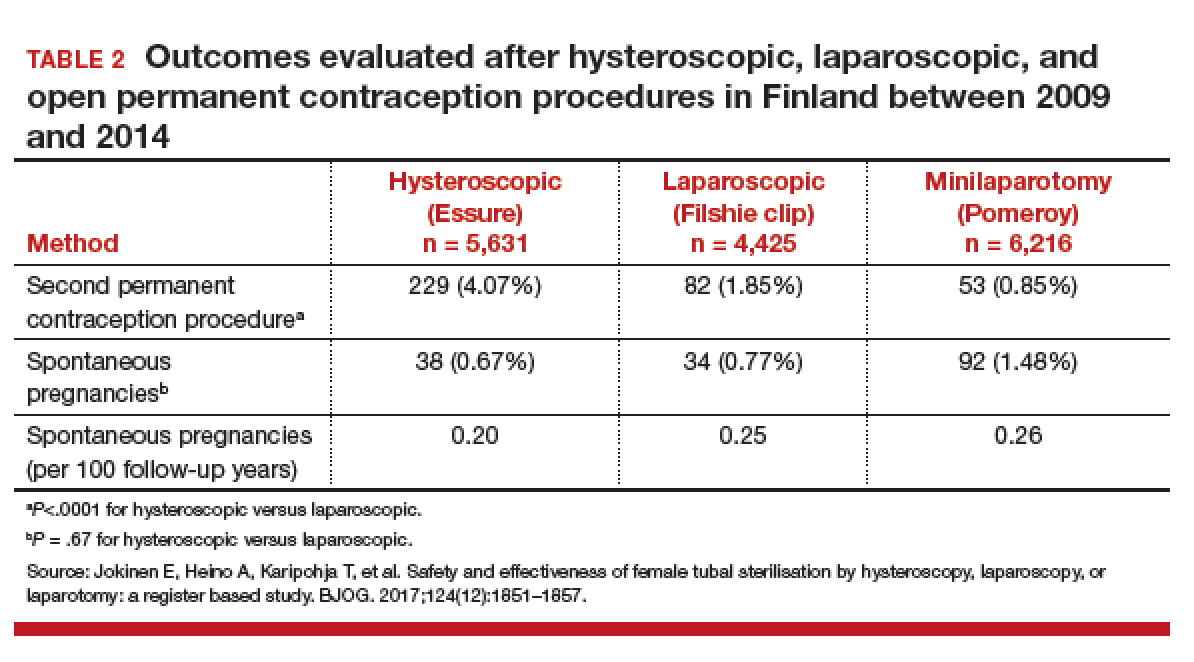

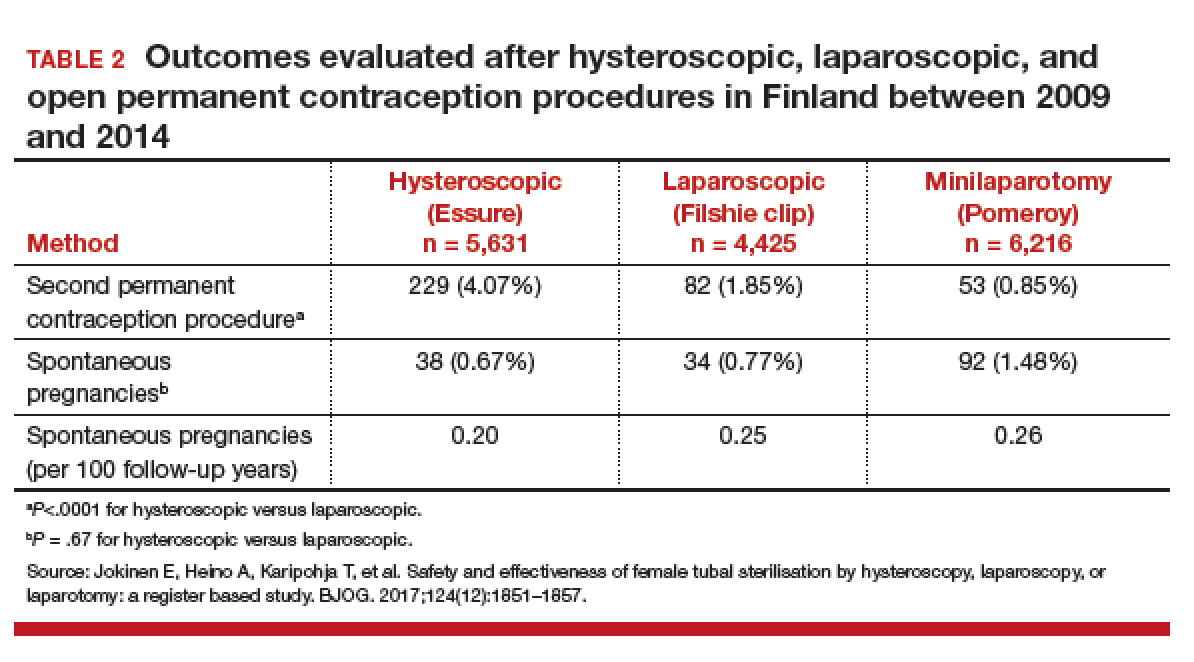

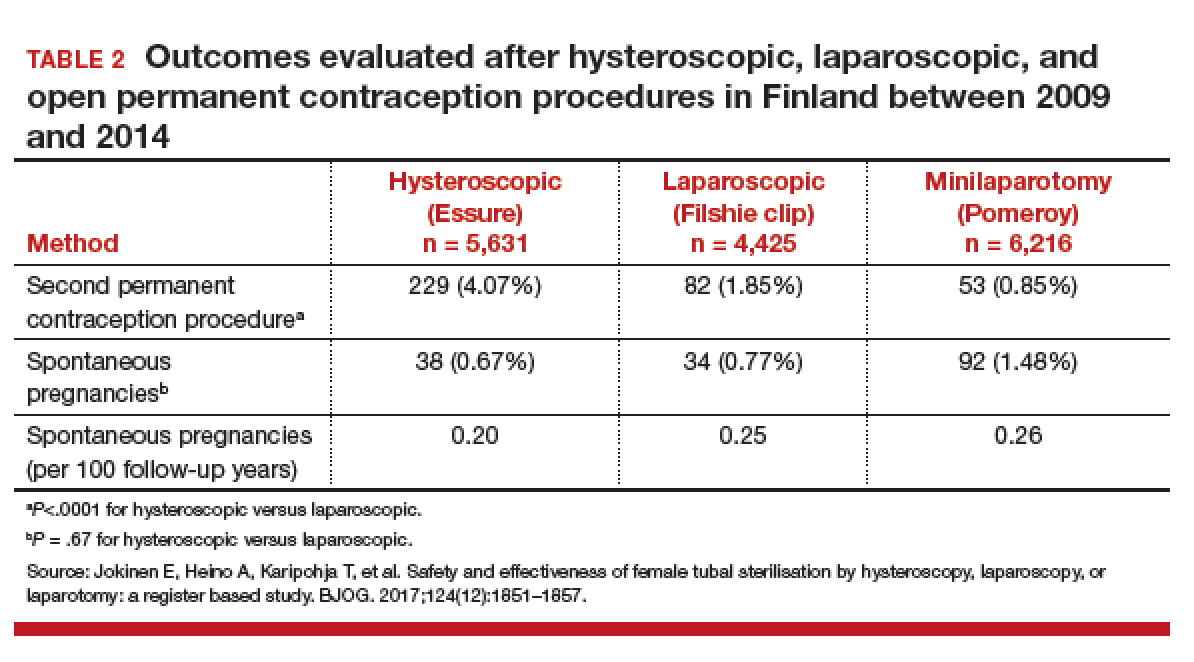

Finnish researchers also find high reoperation rate

Jokinen and colleagues used linked national database registries in Finland to capture data on pregnancy rate and reoperations among 16,272 women who underwent permanent contraception procedures between 2009 and 2014. The authors compared outcomes following hysteroscopic (Essure), laparoscopic (Filshie clip), and postpartum minilaparotomy (Pomeroy) permanent contraception techniques. According to the investigators, the latter method was almost exclusively performed at the time of cesarean delivery. While there was no difference in pregnancy rates, second permanent contraception procedures were significantly greater in the hysteroscopic group compared with the laparoscopic group (TABLE 2).

At a glance, these studies suggest that pregnancy rates are similar between hysteroscopic and laparoscopic permanent contraceptive approaches. But, these low failure rates were only achieved after including women who required reoperation or a second permanent contraceptive procedure. All 3 European studies showed a high follow-up rate; as method failure was identified, additional procedures were offered and performed when desired. These rates are higher than typically reported in US studies. None of the studies included discussion about the proportion of women with failed procedures who declined a second permanent contraceptive surgery. Bouillon et al26 reported a slight improvement in perioperative safety for a hysteroscopic procedure compared with a laparoscopic procedure. While severity of complications was not reported, the risk of reoperation for laparoscopic procedures remained <1%. By contrast, based on the evidence presented here, hysteroscopic permanent contraceptive methods required a second procedure for 4% to 8% of women, most of whom underwent a laparoscopic procedure. Thus, the slight potential improvement in safety of hysteroscopic procedures does not offset the significantly lower efficacy of the method.

Technique for hysteroscopic permanent contraception insert removal

Johal T, Kuruba N, Sule M, et al. Laparoscopic salpingectomy and removal of Essure hysteroscopic sterilisation device: a case series. Eur J Contracept Reprod Health Care. 2018;23(3):227-230.

Lazorwitz A, Tocce K. A case series of removal of nickel-titanium sterilization microinserts from the uterine cornua using laparoscopic electrocautery for salpingectomy. Contraception. 2017;96(2):96-98.

As reports of complications and concerns with hysteroscopic permanent contraception increase, there has been a rise in device removal procedures. We present 2 recent articles that review laparoscopic techniques for the removal of hysteroscopic permanent contraception devices and describe subsequent outcomes.

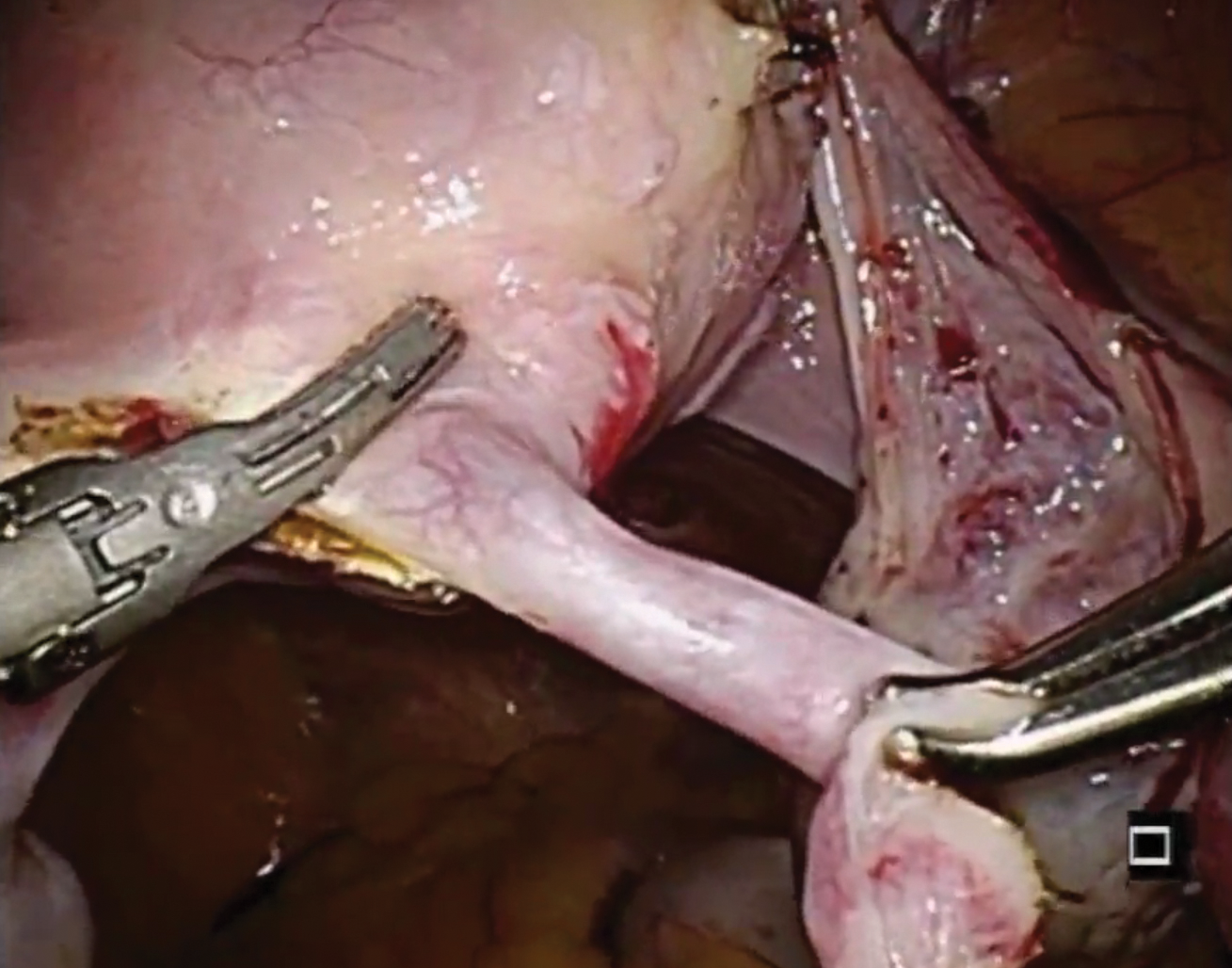

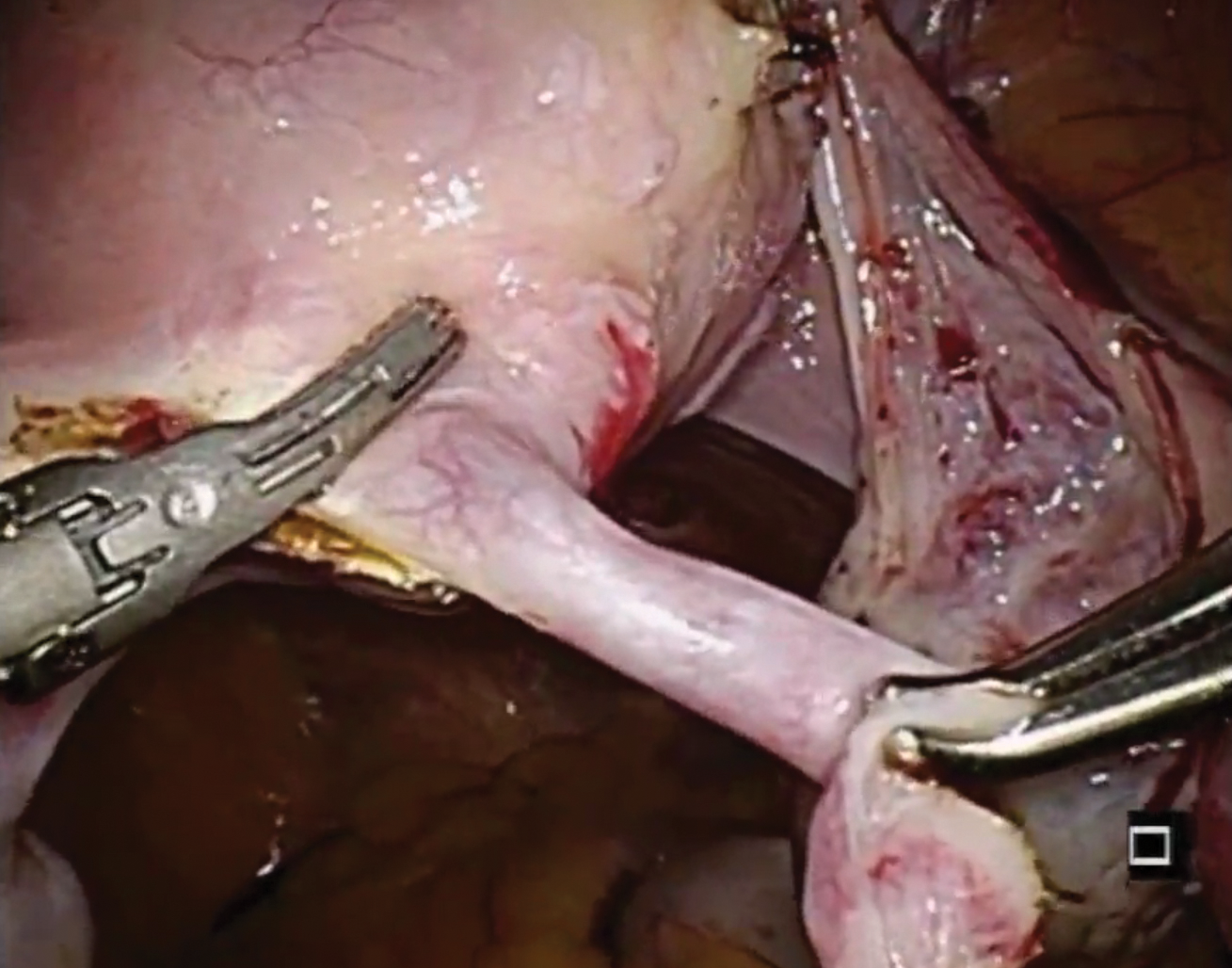

Laparoscopic salpingectomy without insert transection

In this descriptive retrospective study, Johal and colleagues reviewed hysteroscopic permanent contraception insert removal in 8 women between 2015 and 2017. The authors described their laparoscopic salpingectomy approach and perioperative complications. Overall safety and feasibility with laparoscopic salpingectomy were evaluated by identifying the number of procedures requiring intraoperative conversion to laparotomy, cornuectomy, or hysterectomy. The authors also measured operative time, estimated blood loss, length of stay, and incidence of implant fracture.

Indications for insert removal included pain (n = 4), dyspareunia (n = 2), abnormal uterine bleeding (n = 1), and unsuccessful placement or evidence of tubal occlusion failure during confirmatory imaging (n = 4). The surgeons divided the mesosalpinx and then transected the fallopian tube approximately 1 cm distal to the cornua exposing the permanent contraception insert while avoiding direct electrosurgical application to the insert. The inserts were then removed intact with gentle traction. All 8 women underwent laparoscopic removal with salpingectomy. One patient had a surgical complication of serosal bowel injury due to laparoscopic entry that was repaired in the usual fashion. Operative time averaged 65 minutes (range, 30 to 100 minutes), blood loss was minimal, and there were no implant fractures.

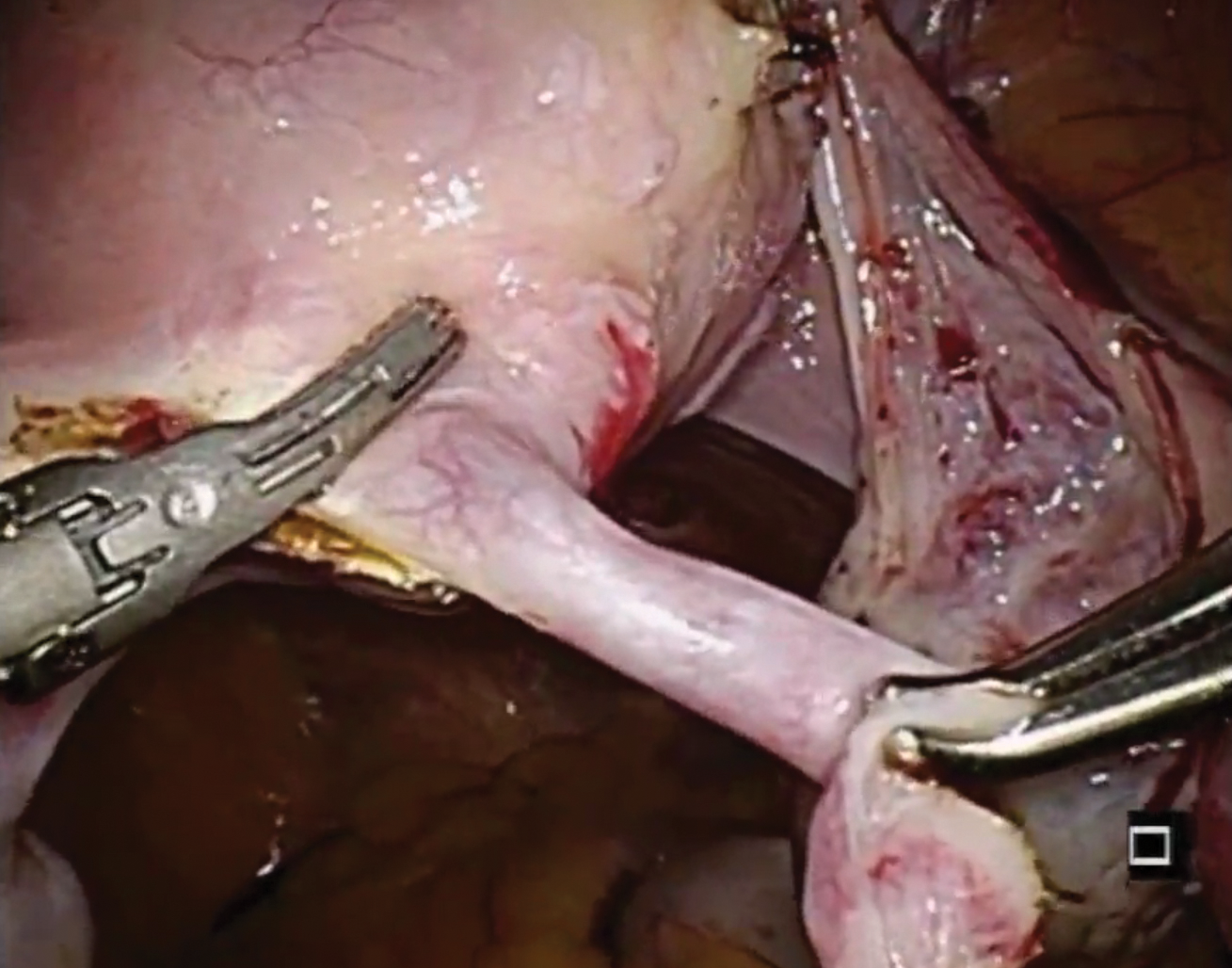

Laparoscopic salpingectomy with insert transection

In this case series, Lazorwitz and Tocce described the use of laparoscopic salpingectomy for hysteroscopic permanent contraception insert removal in 20 women between 2011 and 2017. The authors described their surgical technique, which included division of the mesosalpinx followed by transection of the fallopian tube about 0.5 to 1 cm distal to the cornua. This process often resulted in transection of the insert, and the remaining insert was grasped and removed with gentle traction. If removal of the insert was incomplete, hysteroscopy was performed to identify remaining parts.

Indications for removal included pelvic pain (n = 14), abnormal uterine bleeding (n = 2), rash (n = 1), and unsuccessful placement or evidence of tubal occlusion failure during confirmatory imaging (n = 6). Three women underwent additional diagnostic hysteroscopy for retained implant fragments after laparoscopic salpingectomy. Fragments in all 3 women were 1 to 3 mm in size and left in situ as they were unable to be removed or located hysteroscopically. There were no reported postoperative complications including injury, infection, or readmission within 30 days of salpingectomy.

Shift in method use

Hysteroscopic permanent contraception procedures have low immediate surgical and medical complication rates but result in a high rate of reoperation to achieve the desired outcome. Notably, the largest available comparative trials are from Europe, which may affect the generalizability to US providers, patients, and health care systems.

Importantly, since the introduction of hysteroscopic permanent contraception in 2002, the landscape of contraception has changed in the United States. Contraception use has shifted to fewer permanent procedures and more high-efficacy reversible options. Overall, reliance on female permanent contraception has been declining in the United States, accounting for 17.8% of contracepting women in 1995 and 15.5% in 2013.27,28 Permanent contraception has begun shifting from tubal interruption to salpingectomy as mounting evidence has demonstrated up to a 65% reduction in a woman's lifetime risk of ovarian cancer.29-32 A recent study from a large Northern California integrated health system reported an increase in salpingectomy for permanent contraception from 1% of interval procedures in 2011 to 78% in 2016.33

Long-acting reversible contraceptive (LARC) methods are also becoming more prevalent and are used by 7.2% of women using contraception in the United States.28,34 Typical use pregnancy rates with the levonorgestrel 52-mg intrauterine system, etonogestrel implant, and copper T380A intrauterine device are 0.2%, 0.2%, and 0.4% in the first year, respectively.35,37 These rates are about the same as those reported for Essure in the articles presented here.13,26 Because these methods are easily placed in the office and are immediately effective, their increased availability over the past decade changes demand for a permanent contraceptive procedure.

Essure underwent expedited FDA review because it had the potential to fill a contraceptive void--it was considered permanent, highly efficacious, low risk, and accessible to women regardless of health comorbidities or access to hospital operating rooms. The removal of Essure from the market is not only the result of a collection of problem reports (relatively small given the overall number of women who have used the device) but also the aggregate result of a changing marketplace and the differential needs of pharmaceutical companies and patients.

For a hysteroscopic permanent contraception insert to survive as a marketed product, the company needs high volume use. However, the increase in LARC provision and permanent contraceptive procedures using opportunistic salpingectomy have matured the market away from the presently available hysteroscopic method. This technology, in its current form, is ideal for women desiring permanent contraception but who have a contraindication to laparoscopic surgery, or for women who can access an office procedure in their community but lack access to a hospital-based procedure. For a pharmaceutical company, that smaller market may not be enough. However, the technology itself is still vital, and future development should focus on what we have learned; the ideal product should be immediately effective, not require a follow-up confirmation test, and not leave permanent foreign body within the uterus or tube.

Although both case series were small in sample size, they demonstrated the feasibility of laparoscopic removal of hysteroscopic permanent contraceptive implants. These papers described techniques that can likely be performed by individuals with appropriate laparoscopic skill and experience. The indication for most removals in these reports was pain, unsuccessful placement, or the inability to confirm tubal occlusion by imaging. Importantly, most women do not have these issues, and for those who have been using it successfully, removal is not indicated.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

- Lawrie TA, Kulier R, Nardin JM. Techniques for the interruption of tubal patency for female sterilisation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016(8):CD003034. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD003034.pub3.

- Daniels K, Daugherty J, Jones J, et al. Current contraceptive use and variation by selected characteristics among women aged 15-44: United States, 2011-2013. Natl Health Stat Report. 2015(86):1-14.

- Kavanaugh ML, Jerman J. Contraceptive method use in the United States: trends and characteristics between 2008, 2012 and 2014. Contraception. 2018;97(1):14-21.

- Chan LM, Westhoff CL. Tubal sterilization trends in the United States. Fertil Steril. 2010;94(1):1-6.

- Summary of safety and effectiveness data. FDA website. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/cdrh_docs/pdf2/P020014b.pdf. Accessed August 2, 2018.

- Shah V, Panay N, Williamson R, Hemingway A. Hysterosalpingogram: an essential examination following Essure hysteroscopic sterilisation. Br J Radiol. 2011;84(1005):805-812.

- What is Essure? Bayer website. http://www.essure.com/what-is-essure. Accessed July 6, 2018.

- Stuart GS, Ramesh SS. Interval female sterilization. Obstet Gynecol. 2018;131(1):117-124.

- Essure permanent birth control: instructions for use. Bayer website. http://labeling.bayerhealthcare.com/html/products/pi/essure_ifu.pdf. Accessed July 16, 2018.

- Espey E, Hofler LG. Evaluating the long-term safety of hysteroscopic sterilization. JAMA. 2018;319(4). doi:10.1001/jama.2017.21268.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. ACOG Practice bulletin no. 133: benefits and risks of sterilization. Obstet Gynecol. 2013;121(2 pt 1):392-404.

- Cabezas-Palacios MN, Jiménez-Caraballo A, Tato-Varela S, et al. Safety and patients' satisfaction after hysteroscopic sterilisation. J Obstet Gynaecol. 2018;38(3):377-381.

- Antoun L, Smith P, Gupta JK, et al. The feasibility, safety, and effectiveness of hysteroscopic sterilization compared with laparoscopic sterilization. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2017;217(5):570.e571-570.e576.

- Franchini M, Zizolfi B, Coppola C, et al. Essure permanent birth control, effectiveness and safety: an Italian 11-year survey. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2017;24(4):640-645.

- Vleugels M, Cheng RF, Goldstein J, et al. Algorithm of transvaginal ultrasound and/or hysterosalpingogram for confirmation testing at 3 months after Essure placement. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2017;24(7):1128-1135.

- Essure confirmation test: Essure confirmation test overview. Bayer website. https://www.hcp.essure-us.com/essure-confirmation-test/. Accessed July 16, 2018.

- Casey J, Cedo-Cintron L, Pearce J, et al. Current techniques and outcomes in hysteroscopic sterilization: current evidence, considerations, and complications with hysteroscopic sterilization micro inserts. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol. 2017;29(4):218-224.

- Jeirath N, Basinski CM, Hammond MA. Hysteroscopic sterilization device follow-up rate: hysterosalpingogram versus transvaginal ultrasound. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2018;25(5):836-841.

- US Department of Health and Human Services, US Food & Drug Administration. FDA Activities: Essure. https://www.fda.gov/MedicalDevices/ProductsandMedicalProcedures/ImplantsandProsthetics/ucm452254.htm. Accessed July 6, 2018.

- Horwell DH. End of the road for Essure? J Fam Plann Reprod Health Care. 2017;43(3):240-241.

- Mackenzie J. Sterilisation implant withdrawn from non-US sale. BBC News Health. https://www.bbc.com/news/health-41331963. Accessed July 14, 2018.

- Federal Agency for Medicines and Health Products. ESSURE sterilisation device permanently withdrawn from the market in the European Union. Federal Agency for Medicines and Health Products. https://www.famhp.be/en/news/essure_sterilisation_device_permanently_withdrawn_from_the_market_in_the_european_union. Accessed July 9, 2018.

- Statement from FDA Commissioner Scott Gottlieb, MD, on manufacturer announcement to halt Essure sales in the US; agency's continued commitment to postmarket review of Essure and keeping women informed [press release]. Silver Spring, MD; US Food and Drug Administration. July 20, 2018.

- Gariepy AM, Creinin MD, Smith KJ, et al. Probability of pregnancy after sterilization: a comparison of hysteroscopic versus laparoscopic sterilization. Contraception. 2014;90(2):174-181.

- Gariepy AM, Creinin MD, Schwarz EB, et al. Reliability of laparoscopic compared with hysteroscopic sterilization at 1 year: a decision analysis. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;118(2 pt 1):273-279.

- Bouillon K, Bertrand M, Bader G, et al. Association of hysteroscopic vs laparoscopic sterilization with procedural, gynecological, and medical outcomes. JAMA. 2018;319(4):375-387.

- Mosher WD, Martinez GM, Chandra A, et al. Use of contraception and use of family planning services in the United States: 1982-2002. Adv Data. 2004(350):1-36.

- Mosher WD, Jones J. Use of contraception in the United States: 1982-2008. Vital Health Stat 23. 2010(29):1-44.

- Falconer H, Yin L, Grönberg H, et al. Ovarian cancer risk after salpingectomy: a nationwide population-based study. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2015;107(2). pii: dju410.doi:10.1093/jnci/dju410.

- Madsen C, Baandrup L, Dehlendorff C, et al. Tubal ligation and salpingectomy and the risk of epithelial ovarian cancer and borderline ovarian tumors: a nationwide case-control study. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2015;94(1):86-94.

- Committee on Gynecologic Practice. Committee opinion no. 620: salpingectomy for ovarian cancer prevention. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;125(1):279-281.

- Erickson BK, Conner MG, Landen CN. The role of the fallopian tube in the origin of ovarian cancer. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2013;209(5):409-414.

- Powell CB, Alabaster A, Simmons S, et al. Salpingectomy for sterilization: change in practice in a large integrated health care system, 2011-2016. Obstet Gynecol. 2017;130(5):961-967.

- Daniels K, Daugherty J, Jones J. Current contraceptive status among women aged 15-44: United States, 2011-2013. NCHS Data Brief. 2014(173):1-8.

- Stoddard A, McNicholas C, Peipert JF. Efficacy and safety of long-acting reversible contraception. Drugs. 2011;71(8):969-980.

- Darney P, Patel A, Rosen K, et al. Safety and efficacy of a single-rod etonogestrel implant (Implanon): results from 11 international clinical trials. Fertil Steril. 2009;91(5):1646-1653.

- Long-term reversible contraception. Twelve years of experience with the TCu380A and TCu220C. Contraception. 1997;56(6):341-352.

Female permanent contraception is among the most widely used contraceptive methods worldwide. In the United States, more than 640,000 procedures are performed each year and it is used by 25% of women who use contraception.1–4 Female permanent contraception is achieved via salpingectomy, tubal interruption, or hysteroscopic techniques.

Essure, the only currently available hysteroscopic permanent contraception device, approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in 2002,5,6 has been implanted in more than 750,000 women worldwide.7 Essure was developed by Conceptus Inc, a small medical device company that was acquired by Bayer in 2013. The greatest uptake has been in the United States, which accounts for approximately 80% of procedures worldwide.7,8

Essure placement involves insertion of a nickel-titanium alloy coil with a stainless-steel inner coil, polyethylene terephthalate fibers, platinum marker bands, and silver-tin solder.9 The insert is approximately 4 cm in length and expands to 2 mm in diameter once deployed.9

Potential advantages of a hysteroscopic approach are that intra-abdominal surgery can be avoided and the procedure can be performed in an office without the need for general anesthesia.7 Due to these potential benefits, hysteroscopic permanent contraception with Essure underwent expedited review and received FDA approval without any comparative trials.1,5,10 However, there also are disadvantages: the method is not always successfully placed on first attempt and it is not immediately effective. Successful placement rates range between 60% and 98%, most commonly around 90%.11–15 Additionally, if placement is successful, alternative contraception must be used until a confirmatory radiologic test is performed at least 3 months after the procedure.9,11 Initially, hysterosalpingography was required to demonstrate a satisfactory insert location and successful tubal occlusion.11,16 Compliance with this testing is variable, ranging in studies from 13% to 71%.11 As of 2015, transvaginal ultrasonography showing insert retention and location has been approved as an alternative confirmatory method.9,11,16,17 Evidence suggests that the less invasive ultrasound option increases follow-up rates; while limited, one study noted an increase in follow-up rates from 77.5% for hysterosalpingogram to 88% (P = .008) for transvaginal ultrasound.18

Recent concerns about potential medical and safety issues have impacted approval status and marketing of hysteroscopic permanent contraception worldwide. In response to safety concerns, the FDA added a boxed safety warning and patient decision checklist in 2016.19 Bayer withdrew the device from all markets outside of the United States as of May 2017.20–22 In April 2018, the FDA restricted Essure sales in the United States only to providers and facilities who utilized an FDA-approved checklist to ensure the device met standards for safety and effectiveness.19 Most recently, Bayer announced that Essure would no longer be sold or distributed in the United States after December 31, 2018 (See “FDA Press Release”).23

"The US Food and Drug Administration was notified by Bayer that the Essure permanent birth control device will no longer be sold or distributed after December 31, 2018... The decision today to halt Essure sales also follows a series of earlier actions that the FDA took to address the reports of serious adverse events associated with its use. For women who have received an Essure implant, the postmarket safety of Essure will continue to be a top priority for the FDA. We expect Bayer to meet its postmarket obligations concerning this device."

Reference

- Statement from FDA Commissioner Scott Gottlieb, M.D., on manufacturer announcement to halt Essure sales in the U.S.; agency's continued commitment to postmarket review of Essure and keeping women informed [press release]. Silver Spring, MD; U.S. Food and Drug Administration. July 20, 2018.

So how did we get here? How did the promise of a “less invasive” approach for female permanent contraception get off course?

A search of the Manufacturer and User Facility Device Experience (MAUDE) database from Essure’s approval date in 2002 to December 2017 revealed 26,773 medical device reports, with more than 90% of those received in 2017 related to device removal.19 As more complications and complaints have been reported, the lack of comparative data has presented a problem for understanding the relative risk of the procedure as compared with laparoscopic techniques. Additionally, the approval studies lacked information about what happened to women who had an unsuccessful attempted hysteroscopic procedure. Without robust data sets or large trials, early research used evidence-based Markov modeling; findings suggested that hysteroscopic permanent contraception resulted in fewer women achieving successful permanent contraception and that the hysteroscopic procedure was not as effective as laparoscopic occlusion procedures with “typical” use.24,25

Over the past year, more clinical data have been published comparing hysteroscopic with laparoscopic permanent contraception procedures. In this article, we evaluate this information to help us better understand the relative efficacy and safety of the different permanent contraception methods and review recent articles describing removal techniques to further assist clinicians and patients considering such procedures.

Hysteroscopic versus laparoscopic procedures for permanent contraception

Bouillon K, Bertrand M, Bader G, et al. Association of hysteroscopic vs laparoscopic sterilization with procedural, gynecological, and medical outcomes. JAMA. 2018:319(4):375-387.

Antoun L, Smith P, Gupta J, et al. The feasibility, safety, and effectiveness of hysteroscopic sterilization compared with laparoscopic sterilization. Am J of Obstet Gynecol. 2017;217(5):570.e1-570.e6. doi:10.1016/j.ajog.2017.07.011.

Jokinen E, Heino A, Karipohja T, et al. Safety and effectiveness of female tubal sterilisation by hysteroscopy, laparoscopy, or laparotomy: a register based study. BJOG. 2017;124(12):1851-1857.

In this section, we present 3 recent studies that evaluate pregnancy outcomes and complications including reoperation or second permanent contraception procedure rates.

Data from France measure up to 3-year differences in adverse outcomes

Bouillon and colleagues aimed to identify differences in adverse outcome rates between hysteroscopic and laparoscopic permanent contraceptive methods. Utilizing national hospital discharge data in France, the researchers conducted a large database study review of records from more than 105,000 women aged 30 to 54 years receiving hysteroscopic or laparoscopic permanent contraception between 2010 and 2014. The database contains details based on the ICD-10 codes for all public and private hospitals in France, representing approximately 75% of the total population. Procedures were performed at 831 hospitals in 26 regions.

Adverse outcomes were divided into surgical, medical, and gynecologic complications (TABLE 1) and were assessed at 3 timepoints: at the time of procedure and at 1 and 3 years postprocedure.

Overall, 71,303 women (67.7%) underwent hysteroscopic permanent contraception procedures and 34,054 women (32.3%) underwent laparoscopic permanent contraception procedures. Immediate surgical and medical complications were significantly less common for women having hysteroscopic compared with laparoscopic procedures. Surgical complications at the time of the procedure occurred in 96 (0.13%) and 265 (0.78%) women, respectively (adjusted odds ratio [aOR], 0.18; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.14-0.23). Medical complications at the time of procedure occurred in 41 (0.06%) and 39 (0.11%) women, respectively (aOR, 0.51; 95% CI, 0.30-0.89).

However, gynecologic outcomes, including need for a second surgery to provide permanent contraception and overall failure rates (need for salpingectomy, a second permanent contraception procedure, or pregnancy) were significantly more common for women having hysteroscopic procedures. By 1 year after the procedure, 2,955 women (4.10%) who initially had a hysteroscopic procedure, and 56 women (0.16%) who had a laparoscopic procedure required a second permanent contraception surgery (adjusted hazard ratio [aHR], 25.99; 95% CI, 17.84-37.86). By the third year, additional procedures were performed in 3,230 (4.5%) and 97 (0.28%) women, respectively (aHR, 16.63; 95% CI, 12.50-22.20). Most (65%) of the repeat procedures were performed laparoscopically. Although pregnancy rates were significantly lower at 1 year among women who initially chose a hysteroscopic procedure (0.24% vs 0.41%; aHR, 0.70; 95% CI, 0.53-0.92), the rates did not differ at 3 years (0.48% vs 0.57%, respectively; aHR, 1.04; 95% CI, 0.83-1.30).

Most importantly, overall procedure failure rates were significantly higher at 1 year in women initially choosing a hysteroscopic approach compared with laparoscopic approach (3,446 [4.83%] vs 235 [0.69%] women; aHR, 7.11; 95% CI, 5.92-8.54). This difference persisted through 3 years (4,098 [5.75%] vs 438 [1.29%] women, respectively; aHR, 4.66; 95% CI, 4.06-5.34).

UK data indicate high reoperation rate for hysteroscopic procedures

Antoun and colleagues aimed to compare pregnancy rates, radiologic imaging follow-up rates, reoperations, and 30-day adverse outcomes, between hysteroscopic and laparoscopic permanent contraception methods. Conducted at a single teaching hospital in the United Kingdom, this study included 3,497 women who underwent procedures between 2005 and 2015. The data were collected prospectively for the 1,085 women who underwent hysteroscopic procedures and retrospectively for 2,412 women who had laparoscopic permanent contraception procedures with the Filshie clip.

Over the 10-year study period, hysteroscopic permanent contraception increased from 14.2% (40 of 280) of procedures in 2005 to 40.5% (150 of 350) of procedures in 2015 (P<.001). Overall, 2,400 women (99.5%) underwent successful laparoscopic permanent contraception, compared with 992 women (91.4%) in the hysteroscopic group (OR, 18.8; 95% CI, 10.2-34.4).

In the hysteroscopic group, 958 women (97%) returned for confirmatory testing, of whom 902 (91% of women with successful placement) underwent satisfactory confirmatory testing. There were 93 (8.6%) unsuccessful placements that were due to inability to visualize ostia or tubal stenosis (n = 72 [77.4%]), patient intolerance to procedure (n = 15 [16.1%]), or device failure (n = 6 [6.5%]).

The odds for reoperation were 6 times greater in the hysteroscopic group by 1 year after surgery (22 [2%] vs 8 [0.3%] women; OR, 6.2; 95% CI, 2.8-14.0). However, the 1-year pregnancy risk was similar between the 2 groups, with 3 reported pregnancies after hysteroscopic permanent contraception and 5 reported pregnancies after laparoscopic permanent contraception (OR, 1.3; 95% CI, 0.3-5.6).

Finnish researchers also find high reoperation rate

Jokinen and colleagues used linked national database registries in Finland to capture data on pregnancy rate and reoperations among 16,272 women who underwent permanent contraception procedures between 2009 and 2014. The authors compared outcomes following hysteroscopic (Essure), laparoscopic (Filshie clip), and postpartum minilaparotomy (Pomeroy) permanent contraception techniques. According to the investigators, the latter method was almost exclusively performed at the time of cesarean delivery. While there was no difference in pregnancy rates, second permanent contraception procedures were significantly greater in the hysteroscopic group compared with the laparoscopic group (TABLE 2).

At a glance, these studies suggest that pregnancy rates are similar between hysteroscopic and laparoscopic permanent contraceptive approaches. But, these low failure rates were only achieved after including women who required reoperation or a second permanent contraceptive procedure. All 3 European studies showed a high follow-up rate; as method failure was identified, additional procedures were offered and performed when desired. These rates are higher than typically reported in US studies. None of the studies included discussion about the proportion of women with failed procedures who declined a second permanent contraceptive surgery. Bouillon et al26 reported a slight improvement in perioperative safety for a hysteroscopic procedure compared with a laparoscopic procedure. While severity of complications was not reported, the risk of reoperation for laparoscopic procedures remained <1%. By contrast, based on the evidence presented here, hysteroscopic permanent contraceptive methods required a second procedure for 4% to 8% of women, most of whom underwent a laparoscopic procedure. Thus, the slight potential improvement in safety of hysteroscopic procedures does not offset the significantly lower efficacy of the method.

Technique for hysteroscopic permanent contraception insert removal

Johal T, Kuruba N, Sule M, et al. Laparoscopic salpingectomy and removal of Essure hysteroscopic sterilisation device: a case series. Eur J Contracept Reprod Health Care. 2018;23(3):227-230.

Lazorwitz A, Tocce K. A case series of removal of nickel-titanium sterilization microinserts from the uterine cornua using laparoscopic electrocautery for salpingectomy. Contraception. 2017;96(2):96-98.

As reports of complications and concerns with hysteroscopic permanent contraception increase, there has been a rise in device removal procedures. We present 2 recent articles that review laparoscopic techniques for the removal of hysteroscopic permanent contraception devices and describe subsequent outcomes.

Laparoscopic salpingectomy without insert transection

In this descriptive retrospective study, Johal and colleagues reviewed hysteroscopic permanent contraception insert removal in 8 women between 2015 and 2017. The authors described their laparoscopic salpingectomy approach and perioperative complications. Overall safety and feasibility with laparoscopic salpingectomy were evaluated by identifying the number of procedures requiring intraoperative conversion to laparotomy, cornuectomy, or hysterectomy. The authors also measured operative time, estimated blood loss, length of stay, and incidence of implant fracture.

Indications for insert removal included pain (n = 4), dyspareunia (n = 2), abnormal uterine bleeding (n = 1), and unsuccessful placement or evidence of tubal occlusion failure during confirmatory imaging (n = 4). The surgeons divided the mesosalpinx and then transected the fallopian tube approximately 1 cm distal to the cornua exposing the permanent contraception insert while avoiding direct electrosurgical application to the insert. The inserts were then removed intact with gentle traction. All 8 women underwent laparoscopic removal with salpingectomy. One patient had a surgical complication of serosal bowel injury due to laparoscopic entry that was repaired in the usual fashion. Operative time averaged 65 minutes (range, 30 to 100 minutes), blood loss was minimal, and there were no implant fractures.

Laparoscopic salpingectomy with insert transection

In this case series, Lazorwitz and Tocce described the use of laparoscopic salpingectomy for hysteroscopic permanent contraception insert removal in 20 women between 2011 and 2017. The authors described their surgical technique, which included division of the mesosalpinx followed by transection of the fallopian tube about 0.5 to 1 cm distal to the cornua. This process often resulted in transection of the insert, and the remaining insert was grasped and removed with gentle traction. If removal of the insert was incomplete, hysteroscopy was performed to identify remaining parts.

Indications for removal included pelvic pain (n = 14), abnormal uterine bleeding (n = 2), rash (n = 1), and unsuccessful placement or evidence of tubal occlusion failure during confirmatory imaging (n = 6). Three women underwent additional diagnostic hysteroscopy for retained implant fragments after laparoscopic salpingectomy. Fragments in all 3 women were 1 to 3 mm in size and left in situ as they were unable to be removed or located hysteroscopically. There were no reported postoperative complications including injury, infection, or readmission within 30 days of salpingectomy.

Shift in method use

Hysteroscopic permanent contraception procedures have low immediate surgical and medical complication rates but result in a high rate of reoperation to achieve the desired outcome. Notably, the largest available comparative trials are from Europe, which may affect the generalizability to US providers, patients, and health care systems.

Importantly, since the introduction of hysteroscopic permanent contraception in 2002, the landscape of contraception has changed in the United States. Contraception use has shifted to fewer permanent procedures and more high-efficacy reversible options. Overall, reliance on female permanent contraception has been declining in the United States, accounting for 17.8% of contracepting women in 1995 and 15.5% in 2013.27,28 Permanent contraception has begun shifting from tubal interruption to salpingectomy as mounting evidence has demonstrated up to a 65% reduction in a woman's lifetime risk of ovarian cancer.29-32 A recent study from a large Northern California integrated health system reported an increase in salpingectomy for permanent contraception from 1% of interval procedures in 2011 to 78% in 2016.33

Long-acting reversible contraceptive (LARC) methods are also becoming more prevalent and are used by 7.2% of women using contraception in the United States.28,34 Typical use pregnancy rates with the levonorgestrel 52-mg intrauterine system, etonogestrel implant, and copper T380A intrauterine device are 0.2%, 0.2%, and 0.4% in the first year, respectively.35,37 These rates are about the same as those reported for Essure in the articles presented here.13,26 Because these methods are easily placed in the office and are immediately effective, their increased availability over the past decade changes demand for a permanent contraceptive procedure.

Essure underwent expedited FDA review because it had the potential to fill a contraceptive void--it was considered permanent, highly efficacious, low risk, and accessible to women regardless of health comorbidities or access to hospital operating rooms. The removal of Essure from the market is not only the result of a collection of problem reports (relatively small given the overall number of women who have used the device) but also the aggregate result of a changing marketplace and the differential needs of pharmaceutical companies and patients.

For a hysteroscopic permanent contraception insert to survive as a marketed product, the company needs high volume use. However, the increase in LARC provision and permanent contraceptive procedures using opportunistic salpingectomy have matured the market away from the presently available hysteroscopic method. This technology, in its current form, is ideal for women desiring permanent contraception but who have a contraindication to laparoscopic surgery, or for women who can access an office procedure in their community but lack access to a hospital-based procedure. For a pharmaceutical company, that smaller market may not be enough. However, the technology itself is still vital, and future development should focus on what we have learned; the ideal product should be immediately effective, not require a follow-up confirmation test, and not leave permanent foreign body within the uterus or tube.

Although both case series were small in sample size, they demonstrated the feasibility of laparoscopic removal of hysteroscopic permanent contraceptive implants. These papers described techniques that can likely be performed by individuals with appropriate laparoscopic skill and experience. The indication for most removals in these reports was pain, unsuccessful placement, or the inability to confirm tubal occlusion by imaging. Importantly, most women do not have these issues, and for those who have been using it successfully, removal is not indicated.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

Female permanent contraception is among the most widely used contraceptive methods worldwide. In the United States, more than 640,000 procedures are performed each year and it is used by 25% of women who use contraception.1–4 Female permanent contraception is achieved via salpingectomy, tubal interruption, or hysteroscopic techniques.

Essure, the only currently available hysteroscopic permanent contraception device, approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in 2002,5,6 has been implanted in more than 750,000 women worldwide.7 Essure was developed by Conceptus Inc, a small medical device company that was acquired by Bayer in 2013. The greatest uptake has been in the United States, which accounts for approximately 80% of procedures worldwide.7,8

Essure placement involves insertion of a nickel-titanium alloy coil with a stainless-steel inner coil, polyethylene terephthalate fibers, platinum marker bands, and silver-tin solder.9 The insert is approximately 4 cm in length and expands to 2 mm in diameter once deployed.9

Potential advantages of a hysteroscopic approach are that intra-abdominal surgery can be avoided and the procedure can be performed in an office without the need for general anesthesia.7 Due to these potential benefits, hysteroscopic permanent contraception with Essure underwent expedited review and received FDA approval without any comparative trials.1,5,10 However, there also are disadvantages: the method is not always successfully placed on first attempt and it is not immediately effective. Successful placement rates range between 60% and 98%, most commonly around 90%.11–15 Additionally, if placement is successful, alternative contraception must be used until a confirmatory radiologic test is performed at least 3 months after the procedure.9,11 Initially, hysterosalpingography was required to demonstrate a satisfactory insert location and successful tubal occlusion.11,16 Compliance with this testing is variable, ranging in studies from 13% to 71%.11 As of 2015, transvaginal ultrasonography showing insert retention and location has been approved as an alternative confirmatory method.9,11,16,17 Evidence suggests that the less invasive ultrasound option increases follow-up rates; while limited, one study noted an increase in follow-up rates from 77.5% for hysterosalpingogram to 88% (P = .008) for transvaginal ultrasound.18

Recent concerns about potential medical and safety issues have impacted approval status and marketing of hysteroscopic permanent contraception worldwide. In response to safety concerns, the FDA added a boxed safety warning and patient decision checklist in 2016.19 Bayer withdrew the device from all markets outside of the United States as of May 2017.20–22 In April 2018, the FDA restricted Essure sales in the United States only to providers and facilities who utilized an FDA-approved checklist to ensure the device met standards for safety and effectiveness.19 Most recently, Bayer announced that Essure would no longer be sold or distributed in the United States after December 31, 2018 (See “FDA Press Release”).23