User login

Concurrent Capecitabine and Radiation to Treat End Stage Renal Disease Patients on Dialysis With Locally Advanced Unresectable Gastro-Intestinal Malignancies: A Veteran Population Experience

Background: Capecitabine is an oral precursor of 5-FU (5' deoxy-5-fluoridine), a commonly prescribed chemotherapeutic agent to treat gastrointestinal and breast cancers. Capecitabine is currently contraindicated in patients with severe renal failure with Glomerular filtration rate <

30 ml/min. Literature review shows limited evidence in safety and effectiveness of using capecitabine in patients undergoing hemodialysis.

Case Report 1: A 75-year-old old male with a history of end stage renal disease on hemodialysis, was diagnosed with a 10 cm duodenal mass on CT scan when presented with three months history of abdominal pain and 45 lb weight loss. esophagogastroduodenoscopy and biopsy confirmed

adenocarcinoma of duodenum/ampulla. Patient was deemed to be a high-risk candidate for Whipple’s procedure. The case was discussed in multidisciplinary tumor board and the patient was offered concurrent chemotherapy and radiation with capecitabine 500 mg BID. Posttreatment

CT scans suggested 60% shrinkage in tumor size. Patient was continued on capecitabine 300 mg BID two weeks on and one week off with continued response noted on restaging CT scans.

Case Report 2: A 76-year-old male with end stage renal disease on hemodialysis complained of bleeding per rectum for over 2 years. A colonoscopy showed a circumferential mass at 15 cm from anal verge, and biopsy was consistent with rectal adeno carcinoma. PET/CT scan confirmed primary lesion in rectum as well as abnormal retroperitoneal and left iliac adenopathy with high FDG uptake. EUS staged disease at uT3N0Mx. Given significant pain and bleeding patient was offered palliative radiation along with low dose capecitabine 500 mg BID. Two months after concurrent chemotherapy and radiation, restaging scans showed 50% shrinkage in primary tumor. The patient opted to continue treatment with capecitabine and completed two more cycles of 300 mg BID two weeks on and one week off. A repeat CT scan showed near complete resolution of rectal mass and lymphadenopathy.

Conclusions: Capecitabine is converted to active form 5-FU in liver by thymidine phosphorylase. Over 95% of the drug is excreted in urine. In the original phase II trial utilizing capecitabine at 1250 mg/m2 BID, four patients with GFR < 30 ml/min noted to have grade 3-4 toxicities. Jhaveri et al. in their retrospective analysis showed 12 patients tolerated reduced doses.

Background: Capecitabine is an oral precursor of 5-FU (5' deoxy-5-fluoridine), a commonly prescribed chemotherapeutic agent to treat gastrointestinal and breast cancers. Capecitabine is currently contraindicated in patients with severe renal failure with Glomerular filtration rate <

30 ml/min. Literature review shows limited evidence in safety and effectiveness of using capecitabine in patients undergoing hemodialysis.

Case Report 1: A 75-year-old old male with a history of end stage renal disease on hemodialysis, was diagnosed with a 10 cm duodenal mass on CT scan when presented with three months history of abdominal pain and 45 lb weight loss. esophagogastroduodenoscopy and biopsy confirmed

adenocarcinoma of duodenum/ampulla. Patient was deemed to be a high-risk candidate for Whipple’s procedure. The case was discussed in multidisciplinary tumor board and the patient was offered concurrent chemotherapy and radiation with capecitabine 500 mg BID. Posttreatment

CT scans suggested 60% shrinkage in tumor size. Patient was continued on capecitabine 300 mg BID two weeks on and one week off with continued response noted on restaging CT scans.

Case Report 2: A 76-year-old male with end stage renal disease on hemodialysis complained of bleeding per rectum for over 2 years. A colonoscopy showed a circumferential mass at 15 cm from anal verge, and biopsy was consistent with rectal adeno carcinoma. PET/CT scan confirmed primary lesion in rectum as well as abnormal retroperitoneal and left iliac adenopathy with high FDG uptake. EUS staged disease at uT3N0Mx. Given significant pain and bleeding patient was offered palliative radiation along with low dose capecitabine 500 mg BID. Two months after concurrent chemotherapy and radiation, restaging scans showed 50% shrinkage in primary tumor. The patient opted to continue treatment with capecitabine and completed two more cycles of 300 mg BID two weeks on and one week off. A repeat CT scan showed near complete resolution of rectal mass and lymphadenopathy.

Conclusions: Capecitabine is converted to active form 5-FU in liver by thymidine phosphorylase. Over 95% of the drug is excreted in urine. In the original phase II trial utilizing capecitabine at 1250 mg/m2 BID, four patients with GFR < 30 ml/min noted to have grade 3-4 toxicities. Jhaveri et al. in their retrospective analysis showed 12 patients tolerated reduced doses.

Background: Capecitabine is an oral precursor of 5-FU (5' deoxy-5-fluoridine), a commonly prescribed chemotherapeutic agent to treat gastrointestinal and breast cancers. Capecitabine is currently contraindicated in patients with severe renal failure with Glomerular filtration rate <

30 ml/min. Literature review shows limited evidence in safety and effectiveness of using capecitabine in patients undergoing hemodialysis.

Case Report 1: A 75-year-old old male with a history of end stage renal disease on hemodialysis, was diagnosed with a 10 cm duodenal mass on CT scan when presented with three months history of abdominal pain and 45 lb weight loss. esophagogastroduodenoscopy and biopsy confirmed

adenocarcinoma of duodenum/ampulla. Patient was deemed to be a high-risk candidate for Whipple’s procedure. The case was discussed in multidisciplinary tumor board and the patient was offered concurrent chemotherapy and radiation with capecitabine 500 mg BID. Posttreatment

CT scans suggested 60% shrinkage in tumor size. Patient was continued on capecitabine 300 mg BID two weeks on and one week off with continued response noted on restaging CT scans.

Case Report 2: A 76-year-old male with end stage renal disease on hemodialysis complained of bleeding per rectum for over 2 years. A colonoscopy showed a circumferential mass at 15 cm from anal verge, and biopsy was consistent with rectal adeno carcinoma. PET/CT scan confirmed primary lesion in rectum as well as abnormal retroperitoneal and left iliac adenopathy with high FDG uptake. EUS staged disease at uT3N0Mx. Given significant pain and bleeding patient was offered palliative radiation along with low dose capecitabine 500 mg BID. Two months after concurrent chemotherapy and radiation, restaging scans showed 50% shrinkage in primary tumor. The patient opted to continue treatment with capecitabine and completed two more cycles of 300 mg BID two weeks on and one week off. A repeat CT scan showed near complete resolution of rectal mass and lymphadenopathy.

Conclusions: Capecitabine is converted to active form 5-FU in liver by thymidine phosphorylase. Over 95% of the drug is excreted in urine. In the original phase II trial utilizing capecitabine at 1250 mg/m2 BID, four patients with GFR < 30 ml/min noted to have grade 3-4 toxicities. Jhaveri et al. in their retrospective analysis showed 12 patients tolerated reduced doses.

Findings at Baseline Colonoscopy Are Associated With Future Advanced Neoplasia Despite an Intervening Negative Colonoscopy

Background: Colorectal cancer (CRC) surveillance guidelines suggest that timing of a 3rd colonoscopy should be based on results of two prior exams. However, data are limited on whether baseline screening colonoscopy can inform the risk of advanced neoplasia (AN) at 3rd exam.

Methods: This study describes the risk of AN at 3rd colonoscopy stratified by findings on two previous exams in a prospective screening cohort and compares this risk over time from a negative 2nd exam between those with differing 1st exam findings.

The CSP #380 cohort included 3,121 Veterans aged 50-75 years who underwent screening colonoscopy from 1994-1997 and were followed for at least 10 years. Exclusion criteria included not having three colonoscopies more than one year apart, or having CRC at 1st or 2nd exam. The primary outcome was the proportion of AN at 3rd exam. Findings at 1st and 2nd exam were classified as high-risk adenoma (HRA), low-risk adenoma (LRA), or no adenoma. Chi-square tests compared proportions of AN on the 3rd exam between those with different baseline screening results but similar 2nd exam findings.

Results: This analysis included 891 participants: 58 (6.5%) had AN at 3rd exam. The proportion of AN at 3rd exam ranged from 3.2% to 21.4% when stratified by results of two previous exams. In participants with HRA or LRA on the 2nd exam, baseline screening colonoscopy was not associated with risk of AN at 3rd exam. However, for participants with no adenomas on the 2nd exam, baseline screening colonoscopy was associated with risk of AN at 3rd exam (P =.04). Furthermore, all AN was identified within about 5 years of the negative 2nd exam in those with HRA on the 1st exam.

Conclusions: Results of the 1st exam remain a risk factor for AN at 3rd exam in those with no adenomas at 2nd exam. This supports current guidelines which recommend a shortened surveillance interval in those with no adenomas at 2nd exam but HRA at 1st. Future work will combine CRC risk factors with genomic risk and colonoscopy outcomes over time to better identify individuals who might benefit from continued surveillance and to help inform appropriate surveillance intervals.

Background: Colorectal cancer (CRC) surveillance guidelines suggest that timing of a 3rd colonoscopy should be based on results of two prior exams. However, data are limited on whether baseline screening colonoscopy can inform the risk of advanced neoplasia (AN) at 3rd exam.

Methods: This study describes the risk of AN at 3rd colonoscopy stratified by findings on two previous exams in a prospective screening cohort and compares this risk over time from a negative 2nd exam between those with differing 1st exam findings.

The CSP #380 cohort included 3,121 Veterans aged 50-75 years who underwent screening colonoscopy from 1994-1997 and were followed for at least 10 years. Exclusion criteria included not having three colonoscopies more than one year apart, or having CRC at 1st or 2nd exam. The primary outcome was the proportion of AN at 3rd exam. Findings at 1st and 2nd exam were classified as high-risk adenoma (HRA), low-risk adenoma (LRA), or no adenoma. Chi-square tests compared proportions of AN on the 3rd exam between those with different baseline screening results but similar 2nd exam findings.

Results: This analysis included 891 participants: 58 (6.5%) had AN at 3rd exam. The proportion of AN at 3rd exam ranged from 3.2% to 21.4% when stratified by results of two previous exams. In participants with HRA or LRA on the 2nd exam, baseline screening colonoscopy was not associated with risk of AN at 3rd exam. However, for participants with no adenomas on the 2nd exam, baseline screening colonoscopy was associated with risk of AN at 3rd exam (P =.04). Furthermore, all AN was identified within about 5 years of the negative 2nd exam in those with HRA on the 1st exam.

Conclusions: Results of the 1st exam remain a risk factor for AN at 3rd exam in those with no adenomas at 2nd exam. This supports current guidelines which recommend a shortened surveillance interval in those with no adenomas at 2nd exam but HRA at 1st. Future work will combine CRC risk factors with genomic risk and colonoscopy outcomes over time to better identify individuals who might benefit from continued surveillance and to help inform appropriate surveillance intervals.

Background: Colorectal cancer (CRC) surveillance guidelines suggest that timing of a 3rd colonoscopy should be based on results of two prior exams. However, data are limited on whether baseline screening colonoscopy can inform the risk of advanced neoplasia (AN) at 3rd exam.

Methods: This study describes the risk of AN at 3rd colonoscopy stratified by findings on two previous exams in a prospective screening cohort and compares this risk over time from a negative 2nd exam between those with differing 1st exam findings.

The CSP #380 cohort included 3,121 Veterans aged 50-75 years who underwent screening colonoscopy from 1994-1997 and were followed for at least 10 years. Exclusion criteria included not having three colonoscopies more than one year apart, or having CRC at 1st or 2nd exam. The primary outcome was the proportion of AN at 3rd exam. Findings at 1st and 2nd exam were classified as high-risk adenoma (HRA), low-risk adenoma (LRA), or no adenoma. Chi-square tests compared proportions of AN on the 3rd exam between those with different baseline screening results but similar 2nd exam findings.

Results: This analysis included 891 participants: 58 (6.5%) had AN at 3rd exam. The proportion of AN at 3rd exam ranged from 3.2% to 21.4% when stratified by results of two previous exams. In participants with HRA or LRA on the 2nd exam, baseline screening colonoscopy was not associated with risk of AN at 3rd exam. However, for participants with no adenomas on the 2nd exam, baseline screening colonoscopy was associated with risk of AN at 3rd exam (P =.04). Furthermore, all AN was identified within about 5 years of the negative 2nd exam in those with HRA on the 1st exam.

Conclusions: Results of the 1st exam remain a risk factor for AN at 3rd exam in those with no adenomas at 2nd exam. This supports current guidelines which recommend a shortened surveillance interval in those with no adenomas at 2nd exam but HRA at 1st. Future work will combine CRC risk factors with genomic risk and colonoscopy outcomes over time to better identify individuals who might benefit from continued surveillance and to help inform appropriate surveillance intervals.

New Mexico Veteran Affairs Health Care System: Enhanced Recovery After Surgery: Concept to Practice for Colorectal Cancer Surgery

Purpose: The NMVAHCS is striving for innovation, with the implementation of an enhanced recovery after surgery (ERAS) protocol: best practice.

Background: Literature supports the reduction of intraoperative instability, post-operative ileus and complications, length of stay (LOS), readmission, and an increase in patient satisfaction. LOS is reduced by 2 days, complications decreased by 50%, readmissions reduced by 8%, with an average cost savings of $2,800-$5,900 per patient: depending on ERAS compliance.

Methods: Implementing an ERAS protocol requires engaging a multidisciplinary team comprised of the patient, surgeon, anesthesiologist, and support services. The surgeon/anesthesiologists attended ERAS educational conferences, ongoing seminars educated the teams. Updated patient instructions eased patient understanding. All colorectal cancer patients are enrolled. Ineligibility is due to severe renal dysfunction, or emergency procedure.

Protocols for each of the perioperative phases were created. Preoperative includes pre-habilitation, smoking cessation, pulmonary toilet, and low volume PEG-Gatorade bowel prep with modified Nichol’s prep. Patients drink a clear carbohydrate (CHO) drink 2 hours prior to induction of anesthesia. Intraoperative includes tight glucose and temperature control, goal-directed fluid therapy, pain management with regional and opioid sparing multimodal analgesia, as well as a minimally invasive approach. Postoperative includes avoidance of tubes and drains, early ambulation and pulmonary toilet, CHO drink, narcotics avoidance, and preemptive treatment for nausea and vomiting.

Outcomes are LOS, readmission, opioid use, complications, infection, return of bowel function, and patient satisfaction. Charts are reviewed for compliance and outcomes are recorded.

To sustain the practice, we have templated notes and orders sets to streamline each step of the process: alerting providers to educate patients and staff at each point of the process. Signage has been created to assist the patient and nursing staff in meeting milestones.

Results: From June 2017 to May 2018, 29 patients were enrolled ERAS protocol. PCAs were avoided, reducing ICU stay and overall cost. Patient satisfaction markedly improved with regional pain control, early CHO drink, early ambulation, and removal of Foley. LOS was not significantly affected due to long distance patients and ileostomy teaching, but did decrease by 1 day on average.

Conclusions: Successful ERAS implementation requires an engaged team.

Purpose: The NMVAHCS is striving for innovation, with the implementation of an enhanced recovery after surgery (ERAS) protocol: best practice.

Background: Literature supports the reduction of intraoperative instability, post-operative ileus and complications, length of stay (LOS), readmission, and an increase in patient satisfaction. LOS is reduced by 2 days, complications decreased by 50%, readmissions reduced by 8%, with an average cost savings of $2,800-$5,900 per patient: depending on ERAS compliance.

Methods: Implementing an ERAS protocol requires engaging a multidisciplinary team comprised of the patient, surgeon, anesthesiologist, and support services. The surgeon/anesthesiologists attended ERAS educational conferences, ongoing seminars educated the teams. Updated patient instructions eased patient understanding. All colorectal cancer patients are enrolled. Ineligibility is due to severe renal dysfunction, or emergency procedure.

Protocols for each of the perioperative phases were created. Preoperative includes pre-habilitation, smoking cessation, pulmonary toilet, and low volume PEG-Gatorade bowel prep with modified Nichol’s prep. Patients drink a clear carbohydrate (CHO) drink 2 hours prior to induction of anesthesia. Intraoperative includes tight glucose and temperature control, goal-directed fluid therapy, pain management with regional and opioid sparing multimodal analgesia, as well as a minimally invasive approach. Postoperative includes avoidance of tubes and drains, early ambulation and pulmonary toilet, CHO drink, narcotics avoidance, and preemptive treatment for nausea and vomiting.

Outcomes are LOS, readmission, opioid use, complications, infection, return of bowel function, and patient satisfaction. Charts are reviewed for compliance and outcomes are recorded.

To sustain the practice, we have templated notes and orders sets to streamline each step of the process: alerting providers to educate patients and staff at each point of the process. Signage has been created to assist the patient and nursing staff in meeting milestones.

Results: From June 2017 to May 2018, 29 patients were enrolled ERAS protocol. PCAs were avoided, reducing ICU stay and overall cost. Patient satisfaction markedly improved with regional pain control, early CHO drink, early ambulation, and removal of Foley. LOS was not significantly affected due to long distance patients and ileostomy teaching, but did decrease by 1 day on average.

Conclusions: Successful ERAS implementation requires an engaged team.

Purpose: The NMVAHCS is striving for innovation, with the implementation of an enhanced recovery after surgery (ERAS) protocol: best practice.

Background: Literature supports the reduction of intraoperative instability, post-operative ileus and complications, length of stay (LOS), readmission, and an increase in patient satisfaction. LOS is reduced by 2 days, complications decreased by 50%, readmissions reduced by 8%, with an average cost savings of $2,800-$5,900 per patient: depending on ERAS compliance.

Methods: Implementing an ERAS protocol requires engaging a multidisciplinary team comprised of the patient, surgeon, anesthesiologist, and support services. The surgeon/anesthesiologists attended ERAS educational conferences, ongoing seminars educated the teams. Updated patient instructions eased patient understanding. All colorectal cancer patients are enrolled. Ineligibility is due to severe renal dysfunction, or emergency procedure.

Protocols for each of the perioperative phases were created. Preoperative includes pre-habilitation, smoking cessation, pulmonary toilet, and low volume PEG-Gatorade bowel prep with modified Nichol’s prep. Patients drink a clear carbohydrate (CHO) drink 2 hours prior to induction of anesthesia. Intraoperative includes tight glucose and temperature control, goal-directed fluid therapy, pain management with regional and opioid sparing multimodal analgesia, as well as a minimally invasive approach. Postoperative includes avoidance of tubes and drains, early ambulation and pulmonary toilet, CHO drink, narcotics avoidance, and preemptive treatment for nausea and vomiting.

Outcomes are LOS, readmission, opioid use, complications, infection, return of bowel function, and patient satisfaction. Charts are reviewed for compliance and outcomes are recorded.

To sustain the practice, we have templated notes and orders sets to streamline each step of the process: alerting providers to educate patients and staff at each point of the process. Signage has been created to assist the patient and nursing staff in meeting milestones.

Results: From June 2017 to May 2018, 29 patients were enrolled ERAS protocol. PCAs were avoided, reducing ICU stay and overall cost. Patient satisfaction markedly improved with regional pain control, early CHO drink, early ambulation, and removal of Foley. LOS was not significantly affected due to long distance patients and ileostomy teaching, but did decrease by 1 day on average.

Conclusions: Successful ERAS implementation requires an engaged team.

Veterans With Colorectal Cancer Have a Higher Incidence of a Second Primary Malignancy Than the Colorectal Cancer Survivors in the General Population

Background: Compared to the general population, colorectal cancer (CRC) survivors are at higher risk for developing additional malignancies, with up to 11.5% of male CRC survivors diagnosed with a second distinct malignancy.

Methods: To determine if this trend is similar in CRC survivor veterans, a retrospective analysis of all veterans diagnosed with colorectal cancer (CRC) between 1995 and 2011 within a single Veterans Affairs Medical Center was performed.

Results: Of 1,496 veterans diagnosed with sporadic CRC, 22.6% had developed a second primary malignancy and 2.7% had a third primary malignancy. The most frequently diagnosed second primary malignancies within this cohort included cancer of the prostate (38.5%), lung and bronchus (15.3%), urinary bladder (11.5%), oral cavity and pharynx (6.3%), and kidney and renal pelvis (6.1%). Incidences of second primary malignancies were 24.8%, 27.3%, and 15.9% for veterans of World War II, the Korean War and Vietnam War, respectively.

Conclusions: Our findings indicated that cancer survivor veterans carried even a higher risk of developing a second primary malignancy regardless of their service eras as compared to the general population. Healthcare providers should remain vigilant regarding surveillance for the development of additional, distinct malignancy in this particular patient population.

Background: Compared to the general population, colorectal cancer (CRC) survivors are at higher risk for developing additional malignancies, with up to 11.5% of male CRC survivors diagnosed with a second distinct malignancy.

Methods: To determine if this trend is similar in CRC survivor veterans, a retrospective analysis of all veterans diagnosed with colorectal cancer (CRC) between 1995 and 2011 within a single Veterans Affairs Medical Center was performed.

Results: Of 1,496 veterans diagnosed with sporadic CRC, 22.6% had developed a second primary malignancy and 2.7% had a third primary malignancy. The most frequently diagnosed second primary malignancies within this cohort included cancer of the prostate (38.5%), lung and bronchus (15.3%), urinary bladder (11.5%), oral cavity and pharynx (6.3%), and kidney and renal pelvis (6.1%). Incidences of second primary malignancies were 24.8%, 27.3%, and 15.9% for veterans of World War II, the Korean War and Vietnam War, respectively.

Conclusions: Our findings indicated that cancer survivor veterans carried even a higher risk of developing a second primary malignancy regardless of their service eras as compared to the general population. Healthcare providers should remain vigilant regarding surveillance for the development of additional, distinct malignancy in this particular patient population.

Background: Compared to the general population, colorectal cancer (CRC) survivors are at higher risk for developing additional malignancies, with up to 11.5% of male CRC survivors diagnosed with a second distinct malignancy.

Methods: To determine if this trend is similar in CRC survivor veterans, a retrospective analysis of all veterans diagnosed with colorectal cancer (CRC) between 1995 and 2011 within a single Veterans Affairs Medical Center was performed.

Results: Of 1,496 veterans diagnosed with sporadic CRC, 22.6% had developed a second primary malignancy and 2.7% had a third primary malignancy. The most frequently diagnosed second primary malignancies within this cohort included cancer of the prostate (38.5%), lung and bronchus (15.3%), urinary bladder (11.5%), oral cavity and pharynx (6.3%), and kidney and renal pelvis (6.1%). Incidences of second primary malignancies were 24.8%, 27.3%, and 15.9% for veterans of World War II, the Korean War and Vietnam War, respectively.

Conclusions: Our findings indicated that cancer survivor veterans carried even a higher risk of developing a second primary malignancy regardless of their service eras as compared to the general population. Healthcare providers should remain vigilant regarding surveillance for the development of additional, distinct malignancy in this particular patient population.

Primary Tumor Sidedness in Colorectal Cancer at VA Hospitals: A Nation-Wide Study

Background: Right-sided colon cancer (RC) is derived from the mid-gut, while left-sided colon cancer (LC) originates from the hindgut. LC has been associated with better survival compared to RC. The effect of primary tumor sidedness on colorectal cancer (CRC) survival rates has not been studied in VA hospitals.

Methods: Data from the National VA Cancer Cube Registry was studied. 65,940 cases of CRC were diagnosed between 2001 and 2015. ICD codes C18 to C20 were used to delineate patients with RC vs. LC. RC was defined as cancer from the cecum to the hepatic flexure, LC from the splenic flexure to the rectum with transverse cancer in between flexures. Local IRB approval was obtained.

Results: Of the total number of CRC, 30.3% were RC and 58.8% were LC. RC constituted 36.3% of cases in women and 30.1% of cases in men. RC was diagnosed after the age of 70 years in 51.8% of cases, compared with 38.5% of LC. LC constituted 56.0% of CRC in blacks, and 59.4% in whites. RC was more likely to be diagnosed at more advanced stage, with 60.84% of cases diagnosed at stage II-IV, compared to 51.82% of LC. Stage IV RC has worse one year survival as compared with LC (50.5% vs 42.2% surviving less than one year, respectively)

Conclusions: RC is associated with female gender, older age, poorer functional status, and more advanced stage at diagnosis. LC was associated with white race. Stage IV RC had worse one-year survival than LC colon cancer.

Background: Right-sided colon cancer (RC) is derived from the mid-gut, while left-sided colon cancer (LC) originates from the hindgut. LC has been associated with better survival compared to RC. The effect of primary tumor sidedness on colorectal cancer (CRC) survival rates has not been studied in VA hospitals.

Methods: Data from the National VA Cancer Cube Registry was studied. 65,940 cases of CRC were diagnosed between 2001 and 2015. ICD codes C18 to C20 were used to delineate patients with RC vs. LC. RC was defined as cancer from the cecum to the hepatic flexure, LC from the splenic flexure to the rectum with transverse cancer in between flexures. Local IRB approval was obtained.

Results: Of the total number of CRC, 30.3% were RC and 58.8% were LC. RC constituted 36.3% of cases in women and 30.1% of cases in men. RC was diagnosed after the age of 70 years in 51.8% of cases, compared with 38.5% of LC. LC constituted 56.0% of CRC in blacks, and 59.4% in whites. RC was more likely to be diagnosed at more advanced stage, with 60.84% of cases diagnosed at stage II-IV, compared to 51.82% of LC. Stage IV RC has worse one year survival as compared with LC (50.5% vs 42.2% surviving less than one year, respectively)

Conclusions: RC is associated with female gender, older age, poorer functional status, and more advanced stage at diagnosis. LC was associated with white race. Stage IV RC had worse one-year survival than LC colon cancer.

Background: Right-sided colon cancer (RC) is derived from the mid-gut, while left-sided colon cancer (LC) originates from the hindgut. LC has been associated with better survival compared to RC. The effect of primary tumor sidedness on colorectal cancer (CRC) survival rates has not been studied in VA hospitals.

Methods: Data from the National VA Cancer Cube Registry was studied. 65,940 cases of CRC were diagnosed between 2001 and 2015. ICD codes C18 to C20 were used to delineate patients with RC vs. LC. RC was defined as cancer from the cecum to the hepatic flexure, LC from the splenic flexure to the rectum with transverse cancer in between flexures. Local IRB approval was obtained.

Results: Of the total number of CRC, 30.3% were RC and 58.8% were LC. RC constituted 36.3% of cases in women and 30.1% of cases in men. RC was diagnosed after the age of 70 years in 51.8% of cases, compared with 38.5% of LC. LC constituted 56.0% of CRC in blacks, and 59.4% in whites. RC was more likely to be diagnosed at more advanced stage, with 60.84% of cases diagnosed at stage II-IV, compared to 51.82% of LC. Stage IV RC has worse one year survival as compared with LC (50.5% vs 42.2% surviving less than one year, respectively)

Conclusions: RC is associated with female gender, older age, poorer functional status, and more advanced stage at diagnosis. LC was associated with white race. Stage IV RC had worse one-year survival than LC colon cancer.

Treatment and Survival Rates of Metastatic Pancreatic Cancer at VA Hospitals: A Nation-Wide Study

Backgroud: Metastatic pancreatic cancer (MPC) is associated with an extremely high mortality. Current NCCN guidelines recommend systemic therapy, as it is superior to best supportive care. Undertreatment of MPC continues to be an issue. Recent treatment and survival data of MPC in VA hospitals have not been published. The relationship between MPC treatment and survival and the American College of Surgeons’ (ACS) Committee on Cancer (CoC) accreditation in VA hospitals has not been studied.

Methods: Nationwide data from the National VA Cancer Cube Registry was analyzed. 6,775 patients were diagnosed with MPC between 2000 and 2014. CoC accreditation of each VA hospital was obtained using the ACS website.

Results: MPC constitutes 52.31% of all pancreatic cancer diagnosed (6,775/12,951 cases). The near totality were men (97.44%). The > 70-years age group and the 60-70-years age group were the most common ages at diagnosis with 39.39% and 38.02%, respectively. The proportion of early-onset pancreatic cancer was 2.84%. When compared to all stages of pancreatic cancer, stage IV pancreatic cancer had a lower proportion of cancer originating from the head of the pancreas (39.44% versus 50.63%) and more originating from the tail (17.99% versus 13.39%). Tumors originating from head of the pancreas are more likely to cause biliary symptoms and thus are more likely to be caught at an earlier stage. Overall, treatment rate in the VA at the national level with first-line chemotherapy was 37.61%. The rate of treatment over the years has increased in a linear fashion from 33.01% in 2000 to 41.95% in 2014. This has corresponded with an increase of 1-5 years survival of 9.29% in 2000 to 22.99% in 2014 and 5-10 years survival from 0.96% in 2000 to 6.00% in 2012. Treatment rates in CoC accredited and non-CoC accredited VA hospitals were similar (38.94% and 38.12%, respectively). Survival rates in CoC accredited and non-COC accredited VAs were similar with a 1-5 years survival rate of

8.89% and 8.57%, respectively.

Conclusions: Treatment and survival of MPC have risen significantly in the past decade at VA hospitals. CoC accreditation is not associated with a change in treatment or survival rates.

Backgroud: Metastatic pancreatic cancer (MPC) is associated with an extremely high mortality. Current NCCN guidelines recommend systemic therapy, as it is superior to best supportive care. Undertreatment of MPC continues to be an issue. Recent treatment and survival data of MPC in VA hospitals have not been published. The relationship between MPC treatment and survival and the American College of Surgeons’ (ACS) Committee on Cancer (CoC) accreditation in VA hospitals has not been studied.

Methods: Nationwide data from the National VA Cancer Cube Registry was analyzed. 6,775 patients were diagnosed with MPC between 2000 and 2014. CoC accreditation of each VA hospital was obtained using the ACS website.

Results: MPC constitutes 52.31% of all pancreatic cancer diagnosed (6,775/12,951 cases). The near totality were men (97.44%). The > 70-years age group and the 60-70-years age group were the most common ages at diagnosis with 39.39% and 38.02%, respectively. The proportion of early-onset pancreatic cancer was 2.84%. When compared to all stages of pancreatic cancer, stage IV pancreatic cancer had a lower proportion of cancer originating from the head of the pancreas (39.44% versus 50.63%) and more originating from the tail (17.99% versus 13.39%). Tumors originating from head of the pancreas are more likely to cause biliary symptoms and thus are more likely to be caught at an earlier stage. Overall, treatment rate in the VA at the national level with first-line chemotherapy was 37.61%. The rate of treatment over the years has increased in a linear fashion from 33.01% in 2000 to 41.95% in 2014. This has corresponded with an increase of 1-5 years survival of 9.29% in 2000 to 22.99% in 2014 and 5-10 years survival from 0.96% in 2000 to 6.00% in 2012. Treatment rates in CoC accredited and non-CoC accredited VA hospitals were similar (38.94% and 38.12%, respectively). Survival rates in CoC accredited and non-COC accredited VAs were similar with a 1-5 years survival rate of

8.89% and 8.57%, respectively.

Conclusions: Treatment and survival of MPC have risen significantly in the past decade at VA hospitals. CoC accreditation is not associated with a change in treatment or survival rates.

Backgroud: Metastatic pancreatic cancer (MPC) is associated with an extremely high mortality. Current NCCN guidelines recommend systemic therapy, as it is superior to best supportive care. Undertreatment of MPC continues to be an issue. Recent treatment and survival data of MPC in VA hospitals have not been published. The relationship between MPC treatment and survival and the American College of Surgeons’ (ACS) Committee on Cancer (CoC) accreditation in VA hospitals has not been studied.

Methods: Nationwide data from the National VA Cancer Cube Registry was analyzed. 6,775 patients were diagnosed with MPC between 2000 and 2014. CoC accreditation of each VA hospital was obtained using the ACS website.

Results: MPC constitutes 52.31% of all pancreatic cancer diagnosed (6,775/12,951 cases). The near totality were men (97.44%). The > 70-years age group and the 60-70-years age group were the most common ages at diagnosis with 39.39% and 38.02%, respectively. The proportion of early-onset pancreatic cancer was 2.84%. When compared to all stages of pancreatic cancer, stage IV pancreatic cancer had a lower proportion of cancer originating from the head of the pancreas (39.44% versus 50.63%) and more originating from the tail (17.99% versus 13.39%). Tumors originating from head of the pancreas are more likely to cause biliary symptoms and thus are more likely to be caught at an earlier stage. Overall, treatment rate in the VA at the national level with first-line chemotherapy was 37.61%. The rate of treatment over the years has increased in a linear fashion from 33.01% in 2000 to 41.95% in 2014. This has corresponded with an increase of 1-5 years survival of 9.29% in 2000 to 22.99% in 2014 and 5-10 years survival from 0.96% in 2000 to 6.00% in 2012. Treatment rates in CoC accredited and non-CoC accredited VA hospitals were similar (38.94% and 38.12%, respectively). Survival rates in CoC accredited and non-COC accredited VAs were similar with a 1-5 years survival rate of

8.89% and 8.57%, respectively.

Conclusions: Treatment and survival of MPC have risen significantly in the past decade at VA hospitals. CoC accreditation is not associated with a change in treatment or survival rates.

Colon Cancer Survival in the United States Veterans Affairs By Race and Stage (2001-2009)

Background: CONCORD is a global program for worldwide surveillance of cancer survival. A recent analysis of the CONCORD-2 study shows a 9-10% lower survival rates for blacks affected by colon cancer (CC) as compared to whites in the US between 2001 and 2009.

Methods: We aim to investigate the differences in the survival of blacks and whites affected by CC in the National VA Cancer Cube Database in the same time-period. Overall, 30,196 CC cases between 2001 and 2009 were examined.

Results: 66.12% (19,967) of CC patients identified as white and 16.32% (4929) identified as black. The distribution of stages in blacks was the following: Stage 0: 10.49% (517), I: 25.10% (1237), II: 18.58% (916), III: 17.73% (874) and IV: 17.91% (883). By comparison, CC cases in whites presented as Stage 0: 8.92% (1781), I: 26.62% (5316), II: 22.29% (4450), III 18.75% (3744) and IV 13.71% (2738) (P value for X2 trend test = .021). Interestingly, in contrast to the results of the CONCORD study, the overall 5-year survival for all stages of CC in blacks and whites was similar [blacks: 2,854 (57.90%); whites 11,897 (59.58%); P = .2750]. The same holds true for the 5-year survival for Stage 0 [blacks: 423 (81.82%) whites: 1391 (78.10%); P = .5338], Stage I [blacks: 932 (75.34%) whites: 3973 (74.74%); P = .8667], Stage II [blacks: 605(66.05%) whites:2927 (65.78%); P = .9427], Stage III [blacks:509 (58.24%) whites:2138 (57.10%); P = .7513], Stage IV blacks:101 (11.44%) whites:364 (13.29%); P = .2058].

Conclusions: The racial disparity in survival highlighted in CONCORD-2 (9-10% lower 5-year survival for blacks) is not replicable in the VA system. This difference is likely due to the uniformity of the VA in providing screening and treatment services and in leveling the playing field in terms of access to care. We believe these results should be taken into consideration in the current discussion of the shape of the healthcare system the US should adopt.

Background: CONCORD is a global program for worldwide surveillance of cancer survival. A recent analysis of the CONCORD-2 study shows a 9-10% lower survival rates for blacks affected by colon cancer (CC) as compared to whites in the US between 2001 and 2009.

Methods: We aim to investigate the differences in the survival of blacks and whites affected by CC in the National VA Cancer Cube Database in the same time-period. Overall, 30,196 CC cases between 2001 and 2009 were examined.

Results: 66.12% (19,967) of CC patients identified as white and 16.32% (4929) identified as black. The distribution of stages in blacks was the following: Stage 0: 10.49% (517), I: 25.10% (1237), II: 18.58% (916), III: 17.73% (874) and IV: 17.91% (883). By comparison, CC cases in whites presented as Stage 0: 8.92% (1781), I: 26.62% (5316), II: 22.29% (4450), III 18.75% (3744) and IV 13.71% (2738) (P value for X2 trend test = .021). Interestingly, in contrast to the results of the CONCORD study, the overall 5-year survival for all stages of CC in blacks and whites was similar [blacks: 2,854 (57.90%); whites 11,897 (59.58%); P = .2750]. The same holds true for the 5-year survival for Stage 0 [blacks: 423 (81.82%) whites: 1391 (78.10%); P = .5338], Stage I [blacks: 932 (75.34%) whites: 3973 (74.74%); P = .8667], Stage II [blacks: 605(66.05%) whites:2927 (65.78%); P = .9427], Stage III [blacks:509 (58.24%) whites:2138 (57.10%); P = .7513], Stage IV blacks:101 (11.44%) whites:364 (13.29%); P = .2058].

Conclusions: The racial disparity in survival highlighted in CONCORD-2 (9-10% lower 5-year survival for blacks) is not replicable in the VA system. This difference is likely due to the uniformity of the VA in providing screening and treatment services and in leveling the playing field in terms of access to care. We believe these results should be taken into consideration in the current discussion of the shape of the healthcare system the US should adopt.

Background: CONCORD is a global program for worldwide surveillance of cancer survival. A recent analysis of the CONCORD-2 study shows a 9-10% lower survival rates for blacks affected by colon cancer (CC) as compared to whites in the US between 2001 and 2009.

Methods: We aim to investigate the differences in the survival of blacks and whites affected by CC in the National VA Cancer Cube Database in the same time-period. Overall, 30,196 CC cases between 2001 and 2009 were examined.

Results: 66.12% (19,967) of CC patients identified as white and 16.32% (4929) identified as black. The distribution of stages in blacks was the following: Stage 0: 10.49% (517), I: 25.10% (1237), II: 18.58% (916), III: 17.73% (874) and IV: 17.91% (883). By comparison, CC cases in whites presented as Stage 0: 8.92% (1781), I: 26.62% (5316), II: 22.29% (4450), III 18.75% (3744) and IV 13.71% (2738) (P value for X2 trend test = .021). Interestingly, in contrast to the results of the CONCORD study, the overall 5-year survival for all stages of CC in blacks and whites was similar [blacks: 2,854 (57.90%); whites 11,897 (59.58%); P = .2750]. The same holds true for the 5-year survival for Stage 0 [blacks: 423 (81.82%) whites: 1391 (78.10%); P = .5338], Stage I [blacks: 932 (75.34%) whites: 3973 (74.74%); P = .8667], Stage II [blacks: 605(66.05%) whites:2927 (65.78%); P = .9427], Stage III [blacks:509 (58.24%) whites:2138 (57.10%); P = .7513], Stage IV blacks:101 (11.44%) whites:364 (13.29%); P = .2058].

Conclusions: The racial disparity in survival highlighted in CONCORD-2 (9-10% lower 5-year survival for blacks) is not replicable in the VA system. This difference is likely due to the uniformity of the VA in providing screening and treatment services and in leveling the playing field in terms of access to care. We believe these results should be taken into consideration in the current discussion of the shape of the healthcare system the US should adopt.

First-Line Pembrolizumab Therapy in a Cisplatin-Ineligible Patient With Plasmacytoid Urothelial Carcinoma: A Case Report

Background: Plasmacytoid urothelial carcinoma (PUC) is a rare but aggressive variant of transitional cell carcinoma. In patients with unresectable disease, the most commonly used treatment is combination chemotherapy with methotrexate, vinblastine, doxorubicin and cisplatin (MVAC) or gemcitabine and cisplatin (GC). However, many patients with urothelial carcinoma are cisplatin-ineligible due to renal dysfunction, poor performance status or other comorbidities. We report a case of a cisplatin-ineligible veteran with metastatic PUC who was treated with pembrolizumab.

Case Report: A 71-year-old male veteran with 30 packyear smoking history, schizoaffective disorder and type 2 diabetes found to have multiple right-sided lung nodules and perihilar lymphadenopathy after presenting with atypical chest pain. Staging CT abdomen and pelvis showed bilateral adrenal masses and a large soft tissue mass in the right iliac fossa. Subsequent biopsy of the soft tissue mass had pathology consistent with PUC. As the patient was cisplatin-ineligible due to poor performance status and multiple medical comorbidities, the decision was made to treat with pembrolizumab 2 mg per kg IV every 3 weeks. Repeat CT chest, abdomen and pelvis showed partial response at 3 months and stable disease at 6 months.

Discussion: The KEYNOTE-052 study found that firstline pembrolizumab in cisplatin-ineligible patients with urothelial cancer resulted in complete or partial response in 24% of patients with few adverse effects. However, it is unclear if patients with plasmacytoid variant were included. To our knowledge, this is the first case report of a patient with metastatic PUC not only treated with pembrolizumab but shown to have clinical response.

Conclusions: Given our patient’s clinical response, pembrolizumab is a promising first-line agent for treating cisplatin-ineligible patients with metastatic PUC. Further evaluation is warranted to confirm the benefit of treatment with pembrolizumab in this patient population.

Background: Plasmacytoid urothelial carcinoma (PUC) is a rare but aggressive variant of transitional cell carcinoma. In patients with unresectable disease, the most commonly used treatment is combination chemotherapy with methotrexate, vinblastine, doxorubicin and cisplatin (MVAC) or gemcitabine and cisplatin (GC). However, many patients with urothelial carcinoma are cisplatin-ineligible due to renal dysfunction, poor performance status or other comorbidities. We report a case of a cisplatin-ineligible veteran with metastatic PUC who was treated with pembrolizumab.

Case Report: A 71-year-old male veteran with 30 packyear smoking history, schizoaffective disorder and type 2 diabetes found to have multiple right-sided lung nodules and perihilar lymphadenopathy after presenting with atypical chest pain. Staging CT abdomen and pelvis showed bilateral adrenal masses and a large soft tissue mass in the right iliac fossa. Subsequent biopsy of the soft tissue mass had pathology consistent with PUC. As the patient was cisplatin-ineligible due to poor performance status and multiple medical comorbidities, the decision was made to treat with pembrolizumab 2 mg per kg IV every 3 weeks. Repeat CT chest, abdomen and pelvis showed partial response at 3 months and stable disease at 6 months.

Discussion: The KEYNOTE-052 study found that firstline pembrolizumab in cisplatin-ineligible patients with urothelial cancer resulted in complete or partial response in 24% of patients with few adverse effects. However, it is unclear if patients with plasmacytoid variant were included. To our knowledge, this is the first case report of a patient with metastatic PUC not only treated with pembrolizumab but shown to have clinical response.

Conclusions: Given our patient’s clinical response, pembrolizumab is a promising first-line agent for treating cisplatin-ineligible patients with metastatic PUC. Further evaluation is warranted to confirm the benefit of treatment with pembrolizumab in this patient population.

Background: Plasmacytoid urothelial carcinoma (PUC) is a rare but aggressive variant of transitional cell carcinoma. In patients with unresectable disease, the most commonly used treatment is combination chemotherapy with methotrexate, vinblastine, doxorubicin and cisplatin (MVAC) or gemcitabine and cisplatin (GC). However, many patients with urothelial carcinoma are cisplatin-ineligible due to renal dysfunction, poor performance status or other comorbidities. We report a case of a cisplatin-ineligible veteran with metastatic PUC who was treated with pembrolizumab.

Case Report: A 71-year-old male veteran with 30 packyear smoking history, schizoaffective disorder and type 2 diabetes found to have multiple right-sided lung nodules and perihilar lymphadenopathy after presenting with atypical chest pain. Staging CT abdomen and pelvis showed bilateral adrenal masses and a large soft tissue mass in the right iliac fossa. Subsequent biopsy of the soft tissue mass had pathology consistent with PUC. As the patient was cisplatin-ineligible due to poor performance status and multiple medical comorbidities, the decision was made to treat with pembrolizumab 2 mg per kg IV every 3 weeks. Repeat CT chest, abdomen and pelvis showed partial response at 3 months and stable disease at 6 months.

Discussion: The KEYNOTE-052 study found that firstline pembrolizumab in cisplatin-ineligible patients with urothelial cancer resulted in complete or partial response in 24% of patients with few adverse effects. However, it is unclear if patients with plasmacytoid variant were included. To our knowledge, this is the first case report of a patient with metastatic PUC not only treated with pembrolizumab but shown to have clinical response.

Conclusions: Given our patient’s clinical response, pembrolizumab is a promising first-line agent for treating cisplatin-ineligible patients with metastatic PUC. Further evaluation is warranted to confirm the benefit of treatment with pembrolizumab in this patient population.

How Is the Colorectal Cancer Control Program Doing?

The CDC developed the Colorectal Cancer Control Program (CRCCP) to provide direct colorectal cancer (CRC) screening services to low-income, uninsured, or underinsured populations known to have low CRC screening rates. However, early evaluators found the program was insufficient to detect impact at the state level. In response to those findings, the CDC redesigned CRCCP and funded a new 5-year grant period beginning in 2015. How did the program fare this time? CDC researchers say it “shows promise.”

The CRCCP funds 23 states, 6 universities, and 1 tribal organization to partner with health care systems, implementing evidence-based interventions (EBIs). In this study, the researchers analyzed data reported by 387 of 413 clinics of varying sizes, representing 3,438 providers, and serving a screening-eligible population of 722,925 patients.

The researchers say their evaluation suggests that the CRCCP is working as intended: Program reach was measurable and “substantial,” clinics enhanced EBIs in place or implemented new ones, and the overall average screening rate rose.

At baseline, the screening rate was low (43%), and lowest in rural clinics—although evidence indicates that death rates for CRC are highest among people living in rural areas. In the first year, the overall screening rate increased by 4.4 percentage points. Still, that 47.3% is “much lower” than the commonly cited 67.3% from the 2016 Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System, the researchers note. They add, though, that the results confirm that grantees are working with clinics serving the intended populations and indicate the significant gap in CRC screening rates between those reached by the CRCCP and the US population overall.

Many clinics had ≥ 1 EBI or supporting activity (SA) already in place. Grantees used CRCCP resources to implement new or to enhance EBIs in 95% of the clinics, most often patient reminder activities and provider assessment and feedback. Most of the clinics used CRCCP resources for SAs, such as small media and provider education. Only 12% of clinics used resources for supporting community health workers. However, nearly half the clinics conducted planning activities for future implementation of community health workers and patient navigators.

Nearly 80% of the clinics reported having a CRC screening champion, 73% had a CRC screening policy, and 50% had either 3 or 4 EBIs in place at the end of the first year—all factors that the researchers suggest may support greater screening rate increases.

The CDC developed the Colorectal Cancer Control Program (CRCCP) to provide direct colorectal cancer (CRC) screening services to low-income, uninsured, or underinsured populations known to have low CRC screening rates. However, early evaluators found the program was insufficient to detect impact at the state level. In response to those findings, the CDC redesigned CRCCP and funded a new 5-year grant period beginning in 2015. How did the program fare this time? CDC researchers say it “shows promise.”

The CRCCP funds 23 states, 6 universities, and 1 tribal organization to partner with health care systems, implementing evidence-based interventions (EBIs). In this study, the researchers analyzed data reported by 387 of 413 clinics of varying sizes, representing 3,438 providers, and serving a screening-eligible population of 722,925 patients.

The researchers say their evaluation suggests that the CRCCP is working as intended: Program reach was measurable and “substantial,” clinics enhanced EBIs in place or implemented new ones, and the overall average screening rate rose.

At baseline, the screening rate was low (43%), and lowest in rural clinics—although evidence indicates that death rates for CRC are highest among people living in rural areas. In the first year, the overall screening rate increased by 4.4 percentage points. Still, that 47.3% is “much lower” than the commonly cited 67.3% from the 2016 Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System, the researchers note. They add, though, that the results confirm that grantees are working with clinics serving the intended populations and indicate the significant gap in CRC screening rates between those reached by the CRCCP and the US population overall.

Many clinics had ≥ 1 EBI or supporting activity (SA) already in place. Grantees used CRCCP resources to implement new or to enhance EBIs in 95% of the clinics, most often patient reminder activities and provider assessment and feedback. Most of the clinics used CRCCP resources for SAs, such as small media and provider education. Only 12% of clinics used resources for supporting community health workers. However, nearly half the clinics conducted planning activities for future implementation of community health workers and patient navigators.

Nearly 80% of the clinics reported having a CRC screening champion, 73% had a CRC screening policy, and 50% had either 3 or 4 EBIs in place at the end of the first year—all factors that the researchers suggest may support greater screening rate increases.

The CDC developed the Colorectal Cancer Control Program (CRCCP) to provide direct colorectal cancer (CRC) screening services to low-income, uninsured, or underinsured populations known to have low CRC screening rates. However, early evaluators found the program was insufficient to detect impact at the state level. In response to those findings, the CDC redesigned CRCCP and funded a new 5-year grant period beginning in 2015. How did the program fare this time? CDC researchers say it “shows promise.”

The CRCCP funds 23 states, 6 universities, and 1 tribal organization to partner with health care systems, implementing evidence-based interventions (EBIs). In this study, the researchers analyzed data reported by 387 of 413 clinics of varying sizes, representing 3,438 providers, and serving a screening-eligible population of 722,925 patients.

The researchers say their evaluation suggests that the CRCCP is working as intended: Program reach was measurable and “substantial,” clinics enhanced EBIs in place or implemented new ones, and the overall average screening rate rose.

At baseline, the screening rate was low (43%), and lowest in rural clinics—although evidence indicates that death rates for CRC are highest among people living in rural areas. In the first year, the overall screening rate increased by 4.4 percentage points. Still, that 47.3% is “much lower” than the commonly cited 67.3% from the 2016 Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System, the researchers note. They add, though, that the results confirm that grantees are working with clinics serving the intended populations and indicate the significant gap in CRC screening rates between those reached by the CRCCP and the US population overall.

Many clinics had ≥ 1 EBI or supporting activity (SA) already in place. Grantees used CRCCP resources to implement new or to enhance EBIs in 95% of the clinics, most often patient reminder activities and provider assessment and feedback. Most of the clinics used CRCCP resources for SAs, such as small media and provider education. Only 12% of clinics used resources for supporting community health workers. However, nearly half the clinics conducted planning activities for future implementation of community health workers and patient navigators.

Nearly 80% of the clinics reported having a CRC screening champion, 73% had a CRC screening policy, and 50% had either 3 or 4 EBIs in place at the end of the first year—all factors that the researchers suggest may support greater screening rate increases.

Expanding the Scope of Telemedicine in Gastroenterology

Access to specialized services has been a consistently complex problem for many integrated health care systems, including the Veterans Health Administration (VHA). About two-thirds of veterans experience significant barriers when trying to obtain medical care.1 While these problems partly mirror difficulties that nonveterans face as well, there is a unique obligation toward those who put life and health at risk during their military service.2

To better meet demands, the VHA expanded personnel and clinic infrastructure with more providers and a network of community-based outpatient clinics (CBOC) that created more openings for clinic visits.3 Yet regional variability remains a significant problem for primary and even more so for specialty medical services.

Recent data show that more than one-fifth of all veterans live in areas with low population density and shortages of health care providers.4 The data point at a special problem in this context because these veterans often face long travel times to centers offering specialty services. The introduction of electronic consults functions as an alternative venue to obtain expert input but amounts to only 2% of total consult volume.5 A more interactive approach with face-to-face teleconferencing, case discussions, and special training led by expert clinicians has further improved access in such underserved areas and played a key role in the success of the VHA hepatitis C treatment initiative.6

Despite its clearly proven role and success, these e-consults come with some conceptual shortcomings. A key caveat is the lack of direct patient involvement. Obtaining information from the source rather than relying on symptoms documented by a third person can be essential in approaching medical problems. Experts may be able to tease out the often essential details of a history when making a diagnosis. A direct contact adds an additional, perhaps less tangible, component to the interaction that relies on verbal and nonverbal components of personal interactions and plays an important role in treatment success. Prior studies strongly link credibility of and trust in a provider as well as the related treatment success to such aspects of communication.7,8

Gastroenterology Telemedicine Services

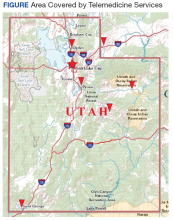

The George E. Wahlen VA Medical Center in Salt Lake City, Utah, draws from a large catchment area that extends from the southern border of Utah to the neighboring states of Idaho, Wyoming, Nevada, and Montana. Large stretches of this territory are remote with population densities well below 5 persons per square mile. The authors therefore devised a specialty outreach program relying on telemedicine for patients with gastrointestinal and liver diseases and present the initial experience with the implementation of this program.

Phase 1: Finding the Champions

Prior studies clearly emphasized that most successful telemedicine clinics relied on key persons (“champions”) promoting the idea and carrying the additional logistic and time issues required to start and maintain the new program.9,10 Thus we created a small team that defined and refined goals, identified target groups, and worked out the logistics. Based on prior experiences, we focused initially on veterans with more chronic and likely functional disorders, such as diarrhea, constipation, dyspepsia, or nausea. The team also planned to accept patients with chronic liver disorders or abnormal test results that required further clarification. By consensus, the group excluded acute problems and bleeding as well as disorders with pain as primary manifestations. The underlying assumption was that a direct physical examination was less critical in most of these cases.

Phase 2: Outreach

Clinic managers and medical directors of the affiliated CBOC were informed of the planned telemedicine clinic. Also, we identified local champions who could function as point persons and assist in the organization of visits. One member of the team personally visited key sites to discuss needs and opportunities with CBOC personnel during a routine staff meeting. The goal was to introduce the program, the key personnel, to explain criteria for appropriate candidates that may benefit from telemedicine consults, and to agree on a referral pathway. Finally, we emphasized that the consultant would always defer to the referring provider or patient and honor their requests.

Phase 3: Identifying Appropriate Patients

The team planned for and has since used 4 different pathways to identify possible candidates for telemedicine visits. The consult triaging process with telemedicine is an option that is brought up with patients if their travel to the facility exceeds 100 miles. Similarly, the team reviews procedural requests to optimize diagnostic yields and limit patient burden. For example, if endoscopic testing is requested to address chronic abdominal pain or other concerns that had already prompted a similar request with negative results, then the team will ask for feedback and recommend a telemedicine consultation prior to performing the procedure. Telemedicine also is offered for follow-up encounters to veterans seen in the facility for clinical or procedural evaluations if they live ≥ 40 miles away. The 2 other pathways are requests from referring providers or patients that specifically ask for telemedicine visits.

Phase 4: Implementation

Since rolling out the program in November 2016, video visits have been used for more than 150 clinic encounters. Within the first 12 months, 124 patients were seen at least once using telemedicine links. Of 144 visits, 54 (38%) were follow-up visits; the rest constituted initial consultations. Focusing on initial encounters only, veterans specifically asked for a telemedicine visit in 16 cases (17.8%). One-third of these referrals was specifically marked as a telemedicine visit by the primary care provider. In the remaining cases, the triaging personnel brought up the possibility of a telemedicine interaction and requested feedback from the referring provider.

Veterans resided in many different areas within and outside of the facility’s immediate referral area (Figure).

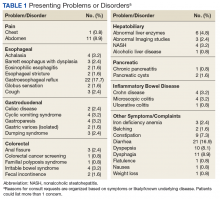

Abnormal bowel patterns, gastroesophageal reflux, and dyspepsia accounted for most concerns (Table 1).

Beyond obtaining contextual data and information about the specific clinical manifestations, the rationale for these encounters was a detailed discussion of the problem and treatment options available. Ablative therapy in Barrett esophagus best exemplifies the potential relevance of such an encounter: Although conceptually appealing to decrease cancer risk, the approach requires a significant commitment typically involving repeated sessions of radiofrequency ablation followed by intense endoscopic surveillance. With travel distances of several hundred miles in these cases, these encounters provide relevant information to patients and the opportunity to make informed decisions without the burden and cost of a long trip.

A shift in telemedicine encounters will likely occur that will increasingly rely on access from home computers or handheld devices. However, the initial phase of this program relied on connections through a CBOC. Coordination between 2 sites adds a level of complexity to ensure availability of space and videoconferencing equipment. To limit the logistic burden and improve cost-effectiveness, the authors did not expect or request the presence of the primary or another independent provider. Instead, the team communicated with a locally designated point person who coordinated the remote encounters and assisted in implementing some of the suggested next steps. Prior site visits and communications with referring providers had established channels of communication to define concerns or highlight findings. The same channels also allowed the team to direct its attention to specific aspects of the physical examination to support or rule out a presumptive diagnosis.

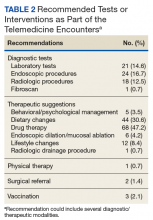

If additional testing was suggested, Telemedicine Services generally ordered the appropriate assessments unless veterans requested relying on local resources better known to personnel at the remote site. The most common diagnostic steps recommended were laboratory tests (n = 21; 14.6%), endoscopic procedures (n = 18; 12.5%), and radiologic studies (n = 17; 11.8%) (Table 2).

Most of the treatment changes focused on medication and dietary management, followed by lifestyle modifications and behavioral or psychological interventions. Some treatments, such as ablation of dysplastic epithelium in patients with Barrett esophagus or pneumatic dilation of achalasia required traveling to the George E. Wahlen VAMC. Nonetheless, the number of trips were limited as the team could assess appropriateness, explain approaches, and evaluate symptomatic outcomes with the initial or subsequent remote encounters. Most of the follow-up involved the primary care providers (n = 62; 43.1%), while repeat remote encounters were suggested in 31 visits (21.5%) and an in-person clinic follow-up in 7 cases (n = 4.9%). In the remaining cases, veterans were asked to contact the team directly or through their primary care provider if additional input was needed.

Discussion

The initial implementation of a specialty telemedicine clinic taught us several lessons that will not only guide this program expansion, but also may be relevant for others introducing telemedicine into their specialty clinics. At first glance, videoconferencing with patients resembles more conventional clinic encounters. However, it adds another angle as many steps from scheduling a visit to implementing recommendations rely on different members at the remote site. Thus, the success of such a program depends on establishing a true partnership with the teams at the various satellite sites. It also requires ongoing feedback from all team members and fine-tuning to effectively integrate it into the routine operations of both sites.

Feedback about the program has been very positive with comments often asking for an expansion beyond gastroenterology. Concerns largely were limited to scheduling problems that may become less relevant if the new telehealth initiative moves forward and enables health care providers to directly connect with computers or handheld devices at the patient’s home. Prior studies demonstrated that most individuals have access to such technology and accept it as a viable or even attractive option for medical encounters.11,12

For some, remaining in the comfort of their own home is not only more convenient, but also adds a sense of security, further adding to its appeal.13 As suggested by the economist Richard Thaler, simple nudges may be required to increase use and perhaps utility of telemedicine or e-consults.14 At this stage, it is the active choice of the referral or triaging provider to consider telemedicine as an option. To facilitate deviation from the established routine, we plan to revise the consult requests by using a drop-down menu option that brings up e-consult, telemedicine, or clinic visit as alternatives and requires an active choice rather than defaulting to conventional face-to-face visits.

Despite an overall successful launch of the specialty telemedicine clinic, several conceptual questions require additional in-depth assessments. While video visits indeed include the literal face time that characterizes normal clinic visits, does this translate into the “face value” that may contribute to treatment success? If detailed information about physical findings is needed, remote encounters require a third person at the distant site to complete this step, which may not only be a logistic burden, but also could influence the perceived utility and affect outcomes.

Previously published studies have demonstrated the effectiveness of video-based interactions and allow providers to address these points to some degree. Remote encounters have established roles in mental healthcare that is less dependent on physical findings.15 Distance monitoring of devices or biomarkers, such as blood sugar levels or blood pressure, are becoming routine and often are combined with corrective interventions.16-18

Recently completed trials showed satisfaction did not differ from conventional clinic encounters when telemedicine encounters were used to manage chronic headaches or provide postoperative follow-up after urologic surgery.19,20 For gastroenterology, telemedicine outreach after hospitalizations not only improved care, but also lowered rates of testing after discharge.21 In patients with inflammatory bowel disease, a group that was not targeted during this initial phase, proactive and close follow-up with remote technology can decrease the need for hospitalization.22

These data are consistent with encouraging feedback received. Nonetheless, it is important to assess whether this approach is superior to established and cheaper alternatives, most notably simple telephone interactions. Video-linkage obviously allows nonverbal elements of communication, which play an important role in patient preference and satisfaction, treatment implementation, and impact.7,8,23-25 Providers described patients as more focused and engaged compared with telephone interactions and valued the ability to incorporate body language in their assessment.26

Telemedicine clinics offered by specialty providers may not improve access as defined by wait times only, which would require adding more clinical time and personnel. However, it can lower barriers to care imposed by long distances between rural areas and facilities with specialized expertise. Even if a remote encounter concludes with the recommendation to visit the clinic for more detailed testing or treatment, explaining the need for such steps and involving the patient in the decision-making process may affect adherence.

Conclusion

Although the experiences of the team at George E. Wahlen VA Medical Center support the use of telemedicine in specialty clinics, the next phase of the project needs to address the utility of this approach and define the perceived value and potential problems of telemedicine. Obtaining this insight will require complex data sets with feedback from patients and referring and consulting providers. As trade-offs will likely vary between different diseases or symptoms, such studies will provide a better definition of clinical scenarios best suited for remote encounters. In addition, they may provide approximate values for distance or efforts that may make the cost of a direct clinic visit worth it, thereby defining boundary-condition.

1. Elnitsky CA, Andresen EM, Clark ME, McGarity S, Hall CG, Kerns RD. Access to the US Department of Veterans Affairs health system: self-reported barriers to care among returnees of Operations Enduring Freedom and Iraqi Freedom. BMC Health Serv Res. 2013;13:498.

2. Woolhandler S, Himmelstein DU, Distajo R, et al. America’s neglected veterans: 1.7 million who served have no health coverage. Int J Health Serv. 2005;35(2):313-323.

3. Rosenheck R. Primary care satellite clinics and improved access to general and mental health services. Health Serv Res. 2000;35:777-790.

4. Doyle JM, Streeter RA. Veterans’ location in health professional shortage areas: implications for access to care and workforce supply. Health Serv Res. 2017;52(suppl 1):459-480.

5. Kirsh S, Carey E, Aron DC, et al. Impact of a national specialty e-consultation implementation project on access. Am J Manag Care. 2015;21(12):e648-e654.

6. Belperio PS, Chartier M, Ross DB, Alaigh P, Shulkin D. Curing hepatitis C virus infection: best practices from the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs. Ann Intern Med. 2017;167(7):499-504.

7. Kaptchuk TJ, Kelley JM, Conboy LA, et al. Components of placebo effect: randomised controlled trial in patients with irritable bowel syndrome. BMJ. 2008;333(7651):999-1003.

8. Weinland SR, Morris CB, Dalton C, et al. Cognitive factors affect treatment response to medical and psychological treatments in functional bowel disorders. Am J Gastroenterol. 2010;105(6):1397-1406.

9. Wade V, Eliott J. The role of the champion in telehealth service development: a qualitative analysis. J Telemed Telecare. 2012;18(8):490-492.

10. Postema TR, Peeters JM, Friele RD. Key factors influencing the implementation success of a home telecare application. Int J Med Inform. 2012;81(6):415-423.

11. Tahir D. Trump and VA unveil telehealth initiative. https://www.politico.com/tipsheets/morning-ehealth/2017/08/04/trump-and-va-unveil-telehealth-initiative-221706. Published August 4, 2017. Accessed July 11, 2018.

12. Gardner MR, Jenkins SM, O’Neil DA, Gardner MR, Jenkins SM, O’Neil DA. Perceptions of video-based appointments from the patient’s home: a patient survey. Telemed J E Health. 2015;21(4):281-285.

13. Powell RE, Henstenburg JM, Cooper G, Hollander JE, Rising KL. Patient perceptions of telehealth primary care video visits. Ann Fam Med. 2017;15(3):225-229.

14. Benartzi S, Beshears J, Milkman KL, et al. Should governments invest more in nudging? Psychol Sci. 2017;28(8):1041-1055.

15. Turgoose D, Ashwick R, Murphy D. Systematic review of lessons learned from delivering tele-therapy to veterans with post-traumatic stress disorder. J Telemed Telecare. 2017:1357633x17730443.

16. Dalouk K, Gandhi N, Jessel P, et al. Outcomes of telemedicine video-conferencing clinic versus in-person clinic follow-up for implantable cardioverter-defibrillator recipients. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2017;10(9) pii: e005217.

17. Warren R, Carlisle K, Mihala G, Scuffham PA. Effects of telemonitoring on glycaemic control and healthcare costs in type 2 diabetes: a randomised controlled trial. J Telemed Telecare. 2017:1357633x17723943.

18. Tucker KL, Sheppard JP, Stevens R, et al. Self-monitoring of blood pressure in hypertension: a systematic review and individual patient data meta-analysis. PLoS Med. 2017;14(9):e1002389.

19. Müller KI, Alstadhaug KB, Bekkelund SI. Headache patients’ satisfaction with telemedicine: a 12-month follow-up randomized non-inferiority trial. Eur J Neurol. 2017;24(6):807-815.

20. Viers BR, Lightner DJ, Rivera ME, et al. Efficiency, satisfaction, and costs for remote video visits following radical prostatectomy: a randomized controlled trial. Eur Urol. 2015;68:729-735.

21. Wallace P, Barber J, Clayton W, et al. Virtual outreach: a randomised controlled trial and economic evaluation of joint teleconferenced medical consultations. Health Technol Assess. 2004;8(50):1-106, iii-iv.

22. de Jong MJ, van der Meulen-de Jong AE, Romberg-Camps MJ, et al. Telemedicine for management of inflammatory bowel disease (myIBDcoach): a pragmatic, multicentre, randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2017;390(10098):959-968.

23. Czerniak E, Biegon A, Ziv A, et al. Manipulating the placebo response in experimental pain by altering doctor’s performance style. Front Psychol. 2016;7:874.

24. Moffet HH, Parker MM, Sarkar U, et al. Adherence to laboratory test requests by patients with diabetes: the Diabetes Study of Northern California (DISTANCE). Am J Manag Care. 2011;17(5):339-344.

25. Richter KP, Shireman TI, Ellerbeck EF, et al. Comparative and cost effectiveness of telemedicine versus telephone counseling for smoking cessation. J Med Internet Res. 2015;17(5):e113.

26. Voils CI, Venne VL, Weidenbacher H, Sperber N, Datta S. Comparison of telephone and televideo modes for delivery of genetic counseling: a randomized trial. J Genet Couns. 2018;27(2):339-348.

Access to specialized services has been a consistently complex problem for many integrated health care systems, including the Veterans Health Administration (VHA). About two-thirds of veterans experience significant barriers when trying to obtain medical care.1 While these problems partly mirror difficulties that nonveterans face as well, there is a unique obligation toward those who put life and health at risk during their military service.2

To better meet demands, the VHA expanded personnel and clinic infrastructure with more providers and a network of community-based outpatient clinics (CBOC) that created more openings for clinic visits.3 Yet regional variability remains a significant problem for primary and even more so for specialty medical services.

Recent data show that more than one-fifth of all veterans live in areas with low population density and shortages of health care providers.4 The data point at a special problem in this context because these veterans often face long travel times to centers offering specialty services. The introduction of electronic consults functions as an alternative venue to obtain expert input but amounts to only 2% of total consult volume.5 A more interactive approach with face-to-face teleconferencing, case discussions, and special training led by expert clinicians has further improved access in such underserved areas and played a key role in the success of the VHA hepatitis C treatment initiative.6

Despite its clearly proven role and success, these e-consults come with some conceptual shortcomings. A key caveat is the lack of direct patient involvement. Obtaining information from the source rather than relying on symptoms documented by a third person can be essential in approaching medical problems. Experts may be able to tease out the often essential details of a history when making a diagnosis. A direct contact adds an additional, perhaps less tangible, component to the interaction that relies on verbal and nonverbal components of personal interactions and plays an important role in treatment success. Prior studies strongly link credibility of and trust in a provider as well as the related treatment success to such aspects of communication.7,8

Gastroenterology Telemedicine Services